Abstract

Background: Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) has the highest incidence in Northeastern Thailand, where patients generally present with late diagnosis and poor prognosis. Opisthorchis viverrini (OV) infection is the major cause of CCA, with oxidative stress driving DNA mutations and genetic instability. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is a predictive biomarker in several cancers. This study aimed to investigate MSI status and its association with clinicopathological features and survival of CCA patients. Methods: Tissue and serum samples were collected from 25 surgical CCA patients. MSI status and mismatch repair (MMR) proteins were evaluated using an MSI scanner and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Serum OV IgG was assessed by ELISA, while tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were evaluated by two pathologists. Associations of MSI with clinicopathological features, OV status, MMR, and survival were analyzed. Results: Among CCA patients, 66.7% were MSI-high and 33.3% were MSI-low. MSI-high significantly correlated with age < 57 years, intraductal growth pattern, OV positivity, and early-stage disease. Patients with MSI-high and high TILs showed markedly improved median survival compared to MSI-low with low TILs (94.0 vs. 16.8 and 3.0 months; HR = 6.82 and 14.10; p = 0.004 and 0.001). Incorporation of MSI and TILs remained an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (p < 0.05). Conclusions: MSI-high is highly prevalent in OV-associated CCA and is associated with intraductal growth, OV infection, and early-stage disease. Combined MSI and TIL status may serve as an independent prognostic factor, warranting validation in larger cohorts.

1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignant tumor arising from the bile duct epithelium. Its incidence is exceptionally high in Asian countries such as China, Korea, Japan, and especially Thailand. The northeastern region of Thailand has the highest incidence worldwide at approximately 85 per 100,000 population per year [1]. CCA has a high mortality rate due to difficulties in early diagnosis, resulting in metastatic disease leading to poor survival. Surgical resection is the most curative treatment and is considered a first choice for treatment in potentially resectable patients in every type of CCA [2]. In 2014, Khuntikeo et al. revealed that in a retrospective study from 2005 to 2012 in CCA patients after curative resection, the 5-year survival was approximately 21.1% [2]. Concordantly, in 2015, Titapun et al. showed that 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival of CCA patients after curative resection was 68%, 33.7%, and 20.6%, respectively [3]. This information indicates that CCA parents have poor outcomes, even after curative treatment.

Opisthorchis viverrini (OV), a food-borne trematode (liver fluke) that infects humans through the consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater fish containing infective metacercariae, is endemic in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. OV infection is a major risk factor for the initiation and progression of carcinogenesis, leading to CCA in this region [4]. The detection of serum IgG antibody against OV in CCA patients using the ELISA assay confirmed that most CCA patients in Thailand were associated with OV infections [5]. OV infection can induce several carcinogenic mechanisms that induce oxidative stress, which alters the DNA sequence [6]. This pathway has been validated as the major cause of genomic alteration and mutation via direct DNA damage. The lipid peroxidation chain and dysfunctional DNA repair regulation proteins imitated the normal bile duct and transformed it into a tumor [7].

Microsatellites, also known as short tandem repeats (STRs), consist of simple repeated sequences of 1–6 nucleotides [8]. STRs show easy-to-mismatch nucleotides during DNA replication and generate a mismatch sequence in genomic DNA, also known as microsatellite instability (MSI), which is the initial cause of genomic alteration and mutation in normal cells, leading to transformation to tumor cells. MSI is characterized by the abnormality of insertions/deletions in short tandem repeats during DNA replication [9]. The major cause of MSI generation is due to the deficiency of mismatch repair (MMR) proteins, by which the DNA repair system corrects DNA mismatch during replication, therefore ensuring genomic conservation and stability. The most common MMR genes are MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and MLH1. Deficiency or dysfunction of MMR (dMMR) genes results in the generation of MSI [9,10]. Generally, MSI is divided into three types, namely, high (MSI-high), low (MSI-low), and stable (MSS) types based on the investigation of the microsatellite status. Technically, detecting MSI can be achieved by immunohistochemistry (IHC), which investigates the loss of the protein products of MSI-related genes [11], or/and by DNA extraction, amplification, and gel electrophoresis analysis [12]. Several reports show that MSI accumulation leads to accumulated mutations that cause carcinogenesis in several cancers. MSI-high is associated with a good survival outcome of several cancers [13]. In addition, previous retrospective studies have shown that MSI-high impacts the prognosis and benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in cancer patients, improving survival outcome [14]. Moreover, MSI knowledge can be applied in alternative therapies, such as immunotherapy. Several reports have consistently revealed that cancer patients who had MSI-high showed an improved response to treatment by immunotherapy when compared with tumors with MSI-low or/and stable microsatellite DNA [13,15,16]. MSI-high is produced from the dMMR function. Thus, cells from dMMR tumors can establish programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their membranes. Furthermore, these tumors show microscopic evidence of high numbers of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), a well-known mechanism that is usually recognized by immune cells, especially T cells, B cells, and NK cells, inducing an immune response to kill tumor cells [17]. With TILs, it is common for immune cells (T and B cells) to display upregulated checkpoint proteins, including programmed death 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4, and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 [18]. TILs may be a result of the high number of mutations found in MSI-H/dMMR tumors, specifically frameshift mutations, resulting in mutant protein neoantigens. MSI-high and TILs have been applied with clinical benefits to prognosis and treatment [18,19,20].

In CCA, although it has been suggested that MSI is found in both OV- [21] and non-OV [22]-associated disease, the outcomes of OV-associated CCA patients who received curative surgery have yet to be investigated. Therefore, this study evaluates the prevalence of MSI status in CCA and its correlation with survival, TILs, OV, MMR status, and clinicopathological features.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Samples

This retrospective study included a total of 25 patients who underwent surgical resection for CCA at Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, between January 2005 and December 2017, and were pathologically confirmed. Tissue and serum specimens, together with clinicopathological data—including age, sex, tumor location, surgical margin status (R0: no microscopic residual tumor at the margin; R1: microscopic tumor cells present at the margin), histologic type, TNM stage according to the 8th edition of the AJCC system [23] (T: primary tumor; N: regional lymph nodes; M: distant metastasis), and patient survival (time from surgery until death or last follow-up)—were obtained from the Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute (CARI), Khon Kaen University, Thailand. These archived specimens and associated data had been previously collected under prior research projects conducted at CARI. Therefore, no new patient recruitment or additional informed consent procedures were required for this study, as the use of existing, de-identified samples and data was approved for retrospective analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University (HE641363; approved on 29 July 2021).

2.2. DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted following the protocol described by Loilome et al. [21]. Paraffin-embedded CCA tissue sections were first deparaffinized by two washes in xylene for 5 min each. The slides were then rehydrated through a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations (100%, 90%, 80%, and 70% for 3 min each) and rinsed with tap water. After rehydration, the slides were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, rinsed under running tap water for 2 min, differentiated in 1% hydrochloric acid in 70% ethanol, washed again in running tap water, and dehydrated sequentially in 70% ethanol (2 min) and absolute ethanol (2 min, twice). Successful nuclear staining was indicated by a blue coloration. Tumorous and non-tumorous regions were then identified under an Axio Scope A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) and separated manually. DNA extraction was carried out using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Matched white blood cells were processed for DNA isolation by incubation in 1 mL lysis buffer with 0.2 µL of 10 mg/mL RNase and 10 µL of 17 mg/mL proteinase K at 50 °C for 30 min. Proteins were precipitated by adding 300 µL of NaI solution, and DNA was precipitated from the supernatant by adding isopropanol. The resulting DNA pellet was resuspended in TE buffer (pH 8.0).

2.3. MSI Analysis

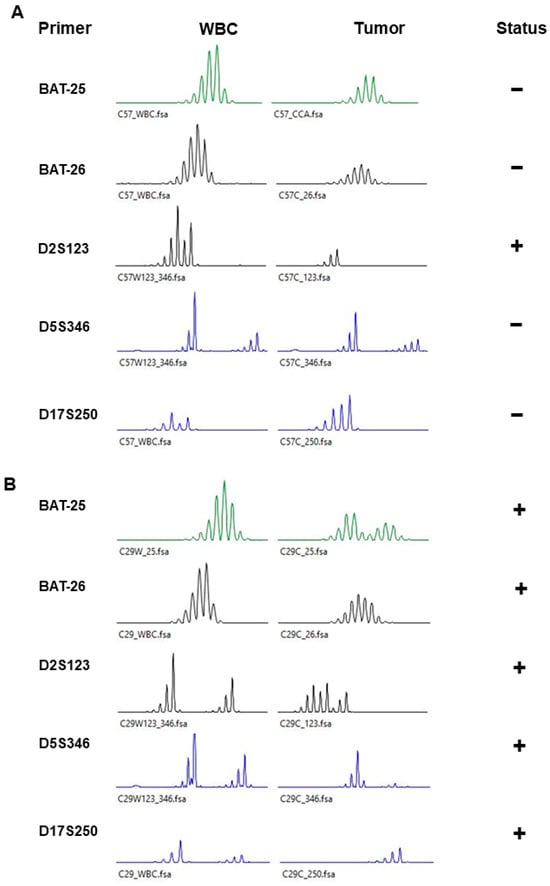

DNA was extracted from tumor tissues, adjacent non-tumor tissues, and matched white blood cells (WBCs) from the same patients to assess MSI using five markers: BAT25, BAT26, D5S346, D2S123, and D17S250 (Table 1) [12]. Forward primers were labeled with a 5′ fluorescent tag. PCR reactions (20 µL) contained 10–100 ng of genomic DNA, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1× high-fidelity PCR buffer, 0.2 µM of each primer, and 1 U of high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Primer sequences are shown in Table 1. For BAT25, BAT26, and D17S250, amplification began with an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. For D2S123 and D5S346, the cycling program included 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. MSI status was determined using an ABI Prism 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and GeneScan Analysis v3.2.1 software, following Bethesda guidelines [12]. Instability was defined as band pattern alterations in tumor or adjacent non-tumor tissues that were absent in matched WBCs. Tumors showing instability at two or more markers were classified as MSI-high, those with one unstable marker as MSI-low, and tumors without instability as microsatellite stable (MSS). MSI-low and MSS tumors were combined into a single group due to their similar phenotypes.

Table 1.

Specific primers for microsatellite polymerase chain reaction analysis. The primer sequences used in this study were identical to those previously described in our publication [21].

2.4. Antibodies

The following antibodies were employed in this study: rabbit monoclonal anti-MLH1 (#ab92312, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a 1:100 dilution and mouse monoclonal anti-MSH2 (#33-7900, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a 1:50 dilution.

2.5. CCA Tissue Microarray (TMA)

Tissue microarrays were constructed using 25 CCA tissue samples, each matched with the corresponding serum. Adjacent non-tumorous liver tissue from the same patients (n = 25) served as normal controls. A tissue microarrayer with a 2.0 mm diameter needle was used to generate the TMA blocks, with each block containing 70 cores. Sections 4 µm in thickness were cut from the blocks and mounted onto coated glass slides.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was carried out on the TMAs to assess protein expression. Sections were first deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through descending ethanol concentrations (100%, 90%, 80%, 70%). Antigen retrieval was performed using 1× Tris-EDTA buffer, with MLH1 sections processed in a pressure cooker and MSH2 sections in an autoclave. Endogenous peroxidase activity and non-specific binding were minimized by incubating the sections with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and 10% skim milk for 10 min each. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% Tween 20, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h. Color development was achieved using a DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Newark, CA, USA), followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Finally, the sections were dehydrated through increasing ethanol concentrations, cleared in xylene, mounted, and examined under a light microscope.

2.7. IHC Scoring System

The level of mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression, MLH1 and MSH2, was examined based on multiplying the frequency and intensity scores (proteins that stained mostly positively), while in proteins that were mostly negative, the level of protein expression was classified as negative or positive staining. The intensity score ranged between zero and three: 0 (negative staining), +1 (weak staining), +2 (moderate staining), and +3 (strong staining). For frequency, the score was classified based on the proportion of positively staining cells. The score was classified as 0 if there was no positive staining, +1 (positive staining less than 25%), +2 (positive staining between 25% and 50%), and +3 (positive staining greater than 50%). The final score (calculated from two independent punctures) ranged between zero and nine. The median score was used as a cut-off for low and high expression (Supplemental Figure S1). The MMR status was evaluated using MLH1 and MSH2 immunohistochemical staining. Cases with retained nuclear expression of both proteins were classified as proficient MMR (pMMR), whereas cases with complete loss of nuclear expression of at least one protein were classified as deficient MMR (dMMR).

2.8. Opisthorchis viverrini (OV) Detection with Immunoglobulin G (IgG) Antibodies Using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

This assay aimed to quantify IgG antibodies against OV infection, a key risk factor for CCA in Northeast Thailand. Indirect ELISA was employed to measure antibody levels. Ninety-six-well plates were coated with OV antigen (1500 µg/mL in 1× PBS, pH 7.4) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, wells were blocked with 3% skim milk in PBS (250 μL/well) at 37 °C for 1 h. Patient sera, diluted 1:6000 in 3% skim milk, were added in duplicate (100 μL/well) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following washes, HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (1:3000 in 3% skim milk) was applied and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The enzymatic reaction was developed using orthophenylene diamine hydrochloride (OPD; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, USA) for 30 min and terminated with 4N sulfuric acid. Optical density (OD) was read at 492 nm on a microplate reader (Tecan Austria GmbH, Grödig, Austria). Samples with OV IgG levels above the 75th percentile were categorized as high.

2.9. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Evaluation

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were evaluated on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections following the International TIL Working Group (ITWG) guidelines [24], as applied to CCA in a previous study by Intarawichian et al. [25]. For each case, the average percentage of TILs was determined to quantify TIL levels (Supplemental Figure S2). Assessment focused on mononuclear cells within the stromal regions surrounding the tumor border and within the tumor itself, excluding polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Both stromal and intratumoral TILs were scored, and the average TIL percentage was calculated for each case. The percentage of stromal TILs was calculated as the area occupied by mononuclear inflammatory cells divided by the total stromal area, while intratumoral TILs were calculated as the area of mononuclear cells divided by the total tumor cell area (Supplemental Figure S2). In this study, a median TIL value of 40% was used as the cut-off to categorize cases into low (<40%) and high (≥40%) TIL groups for subsequent analyses.

2.10. Growth Pattern Estimation

Tumor growth patterns were assessed following the criteria described by Sa-Ngiamwibool et al. [26]. Resection specimens were first trimmed and photographed, and the growth patterns were recorded during gross examination, followed by confirmation through histological analysis. The patterns evaluated included intraductal (ID), periductal infiltrating (PI), and mass-forming (MF). Each pattern was quantified in 10% increments to determine the proportion of individual patterns (ID, PI, or MF) as well as combinations of patterns (ID + PI, ID + MF, PI + MF, or ID + PI + MF).

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to examine associations between clinicopathological features, TILs, OV IgG levels, and MMR protein status with MSI: low vs. high in human CCA tissues. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, with group differences assessed by the log-rank test. Variables with p-value < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of MSI Status in OV-Associated CCA

The microsatellite marker status of 25 CCA patients was determined for BAT-25, BAT-26, D2S123, D5S346, and D17S250, also known as the Bethesda panel. The decision criteria follow the methods section. This study showed that 19/25 (76%) cases of CCA patients showed MSI-high, while only 6/25 (24%) cases presented MSI-low (Table 2 and Figure 1). D2S123 was the marker with the highest frequency of instability at approximately 96%, second was D5S346 at 56%, BAT26 and D17S250 at 52%, and BAT25 at 32%.

Table 2.

Microsatellite marker analysis and MSI status.

Figure 1.

Representative figure of microsatellite markers of WBCs (white blood cells) and tumors. (A) MSI-low and (B) MSI-high. − or + represent negative or positive MSI in each marker, respectively.

3.2. The Correlation Between MSI Status with Clinicopathological Features and OV Status in CCA Patients

The median patient age was 57 years (range, 43–73 years). A total of 20/25 (80%) patients had intrahepatic CCA. The tumor sample showed only a growth pattern of mass and was separated into two groups based on the patient’s outcome [26], including 15/24 cases (63%) with ID components (ID, ID + PI, or/and MF) and 9/24 cases (37%) without ID components (PI, MF, and IP + MF). Surgical margin, determined microscopically, showed 10/25 cases (40%) that were tumor positive or R1. TNM stage followed the 8th AJCC/UICC staging system. The T stage was separated into the early T stage (T0–T2), 17/25 (68%), and the late T stage (T3–T4), 8/25 (32%). TNM staging was divided into two groups: the early TNM stage (0–II) with 10/25 cases (40%) and the late TNM stage (III–IV) with 15/25 cases (60%). The median TIL was 40%, and this was used to separate patients into low (TILs < 40%, n = 12) and high (TILs ≥ 40%, n = 12) levels. OV infection was determined by the detection of the IgG antibody against OV antigen, and the result showed that 17/25 cases (68%) were OV positive. MMR protein status showed that 14/23 (60.9%) cases of CCA presented a deficient MMR status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics’ correlation with MSI status.

The association between MSI status and these features was examined to determine the proportion difference. The result showed that MSI-high was associated with good outcome features, including age < 57 years, with ID components (p = 0.027), early stage of cancer (p = 0.022), and OV-positive (p = 0.037) (Table 3). In other words, MSI-low was associated with a poor outcome of clinicopathological features, such as age ≥ 57 years, without ID components, and late stage of cancer.

3.3. Survival Analysis, Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of CCA Patients

The overall survival (OS) of the 25 CCA patients was 19.7 months (mo.) (95% CI: 10.9–28.4). All patients died during the observation period. There were no statistically significant differences in the survival times by age, gender, tumor location, OV antibody, and MMR status.

CCA with MSI-high had a significantly longer survival time compared to MSI-low, with median survival times of 30.7 and 5.1 months (HR = 0.23, p = 0.003), respectively.

TIL status revealed that a high level of TILs had a significantly longer survival than low levels of TILs (OS = 58.3 vs. 8.9 mo., HR = 0.21, p = 0.005).

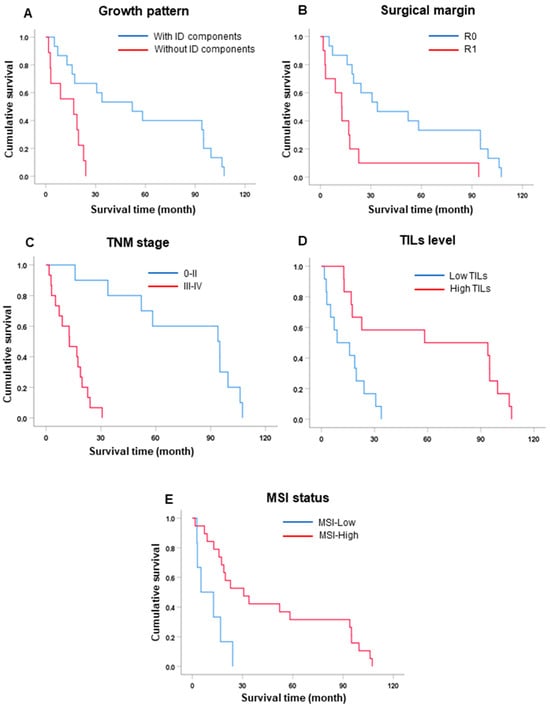

Tumor growth with intraductal (ID) components had a significantly better survival time than without ID components (OS = 52.1 vs. 16.8 mo., HR = 5.01, p = 0.002).

Patients with positive surgical margins (R1) had an overall survival significantly lower than those with free surgical margins (R0) (OS = 12.6 vs. 33.8 mo., HR = 3.67, p = 0.003).

According to the 8th AJCC staging system, for lymph node metastasis (N), the results showed that patients who had a negative N status had a better survival time trend than patients who had a positive N status (OS = 30.7 vs. 17.4 mo., HR = 2.68, p = 0.052). Finally, TNM staging showed that patients with early-stage (0–II) tumors had significantly better survival times than those with late-stage (III–IV) tumors (OS = 94.0 vs. 12.8 mo., HR = 28.23, p < 0.001) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard regression for clinical characteristics in the survival of CCA patients.

Figure 2.

Survival (Kaplan–Meier) analysis. (A) Growth pattern. (B) Surgical margin. (C) TNM stage. (D) TIL status. (E) MSI status.

Subsequently, the significant factors, such as growth pattern, surgical margin, TNM staging, TILs, and MSI status, identified in the univariate analyses of survival, were selected for further investigation by multivariate analysis to investigate independent factors for prognostic markers in CCA.

To determine prognostic markers, multivariate analysis was performed to consider possible features that significantly affected the survival times of CCA patients in univariate analysis. There were five factors: surgical margin and TILs had hazard ratios showing significant differences with their reference groups (HR = 16.29 and 0.06 and p = 0.001 and 0.002, respectively) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in growth pattern, TNM staging, and MSI status after testing with multivariate analysis by Cox regression. Therefore, surgical margin and TILs were independent factors for the prognosis of CCA patient outcomes. To validate the robustness of these findings, we additionally performed sub-model analyses, including two to three variables in each model, to avoid collinearity among variables (stage and margin status). The results from these sub-models were consistent with those obtained from the full model (Supplementary Table S1).

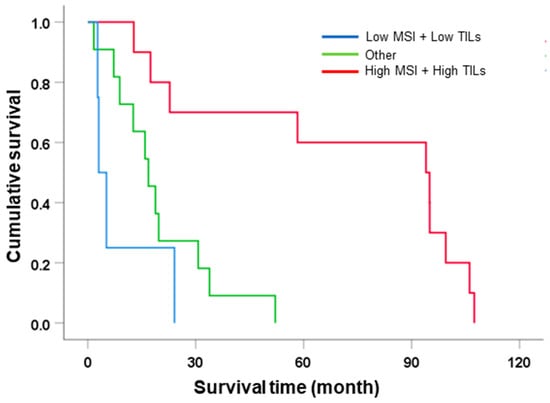

3.4. Incorporation of MSI and TILs Improves Predicting the Outcome of CCA Patients

According to survival analysis, MSI and TIL status affected the survival of CCA patients; especially, TIL was an independent factor in the survival outcome. Several cancers showed that incorporating MSI and TILs as prognostic factors provided a clinical benefit. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the combined role of MSI and TILs in the survival of CCA patients. In this investigation, patients were divided into three groups, including low MSI + low TILs (n = 4), other (high MSI + low TILs or low MSI + high TILs, n = 10), and high MSI + high TILs (n = 10). Univariate analysis of survival showed that patients with high MSI + high TILs had significantly better survival than those with low MSI + low TILs (MST = 94 mo. vs. 16.8 and 3 mo., HR = 6.82 and 14.1, p = 0.004 and 0.001, respectively) (Table 5 and Figure 3).

Table 5.

The survival analysis of incorporating MSI and TIL status in CCA patients.

Figure 3.

The survival analysis of incorporating MSI and TIL status subclassification.

Another aim was to determine the prognostic ability of MSI + TIL status. Multivariate analysis was performed using the significant factors influencing survival in the univariate analysis in Table 4: growth pattern, surgical margin, and TNM stage. Obviously, MSI and TIL status was independent factors in multivariate analysis. High MSI + high TILs acted as the reference group, which had better survival when compared with low MSI + low TILs (HR = 12.77 and 31.86, p = 0.003 and 0.004, respectively) (Table 6). Therefore, a combination of MSI and TILs was prognostic for the survival outcome of CCA patients.

Table 6.

Cox proportional hazard regression for clinical characteristics and incorporation of MSI with TIL status in the survival of CCA patients.

4. Discussion

Cholangiocarcinoma in Northeastern Thailand has been consistently reported to be caused by liver fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini) infection [4]. It can be detected in several types of specimens, such as feces [27], urine [28], and serum [3,28]. The IgG antibody against OV antigen using the ELISA assay was reported by Tesana et al. to have a high sensitivity and specificity of 99.2% and 93%, respectively [28]. This technique has been applied in CCA patients in Northeastern Thailand, and the screening by ELISA showed that 73% of CCA patients were positive for IgG for OV antigen [5]. This information is also confirmed in our study, in that 68% CCA of patients who were screened had positive IgG for OV antigen. Therefore, OV-initiated CCA is a major cause of CCA carcinogenesis. Since OV infection has been revealed to initiate carcinogenesis, several molecular pathways, including oxidative stress-induced genomic alteration, have been proposed as the main pathways leading to tumor formation [6,7]. This mechanism was validated by Loilome et al., who found that impairment of the antioxidant system, such as by superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and catalase (CAT), in CCA patients led to an accumulation of free radicals resulting in biomolecular damage in cells. The disruption of the antioxidant system and induction of an oxidant-generating system are well-recognized causes of oxidative stress that can increase oxidative damage to a wide range of biomolecules, including DNA, lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins [6,7,29]. In addition, increasing oxidative stress causes an imbalance in the DNA repair system, leading to an accumulation of specific mutation points during DNA replication, also called microsatellite instability (MSI). The current study found MSI-low (31%) and MSI-high (69%) in human CCA tissues [21]. Taken together, OV infection causes genomic alterations, especially MSI, in CCA through impairment of the antioxidant system, resulting in the dysfunction of the DNA repair system.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is characterized by an abnormality in insertions/deletions in short tandem repeats during DNA replication. This is the initial cause of genomic alteration and mutation in normal cells. A deficiency of mismatch repair (MMR) proteins, which corrects mismatches in DNA during replication, has been reported to be a major cause of MSI generation. MSI is a well-recognized cause of cancer genesis and progression. We also found MSI-low (24%) and MSI-high (76%) in human CCA tissues. MSI-high patients showed a favorable response to treatment with surgery and better overall survival than MSI-low patients. Although this finding was contrary to that of Loilome et al. [21] and Limpaiboon et al. [30], who showed that MSI-high was associated with a poor outcome in CCA patients, numerous reports from colorectal [15,31,32], non-colorectal cancers (prostate [13], endometrial carcinoma [33] ovarian, pancreatic, and small intestine cancers [34,35,36]), and non-OV associated CCA [22] cancer consistently suggest that MSI-high responds to treatments such as surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, and immunotherapy better when compared with tumours with MSI-low or/and stable microsatellite DNA in colorectal cancer and non-colorectal cancers.

Why surgery leads to a good outcome in CCA patients with MSI-high is still unclear. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are proposed to reduce cancer progression and provide a good prognosis in several cancers [37,38,39]. MSI-high frequency produces neoantigens, which are tumor-specific antigens generated by mutations in tumor cells [40,41]. They are recognized by lymphocyte cells, especially T cells, in the immune system. Previous reports suggested that cancer patients who have MSI-high-related neoantigen expression respond to treatments better [37,39,42]. In colorectal cancer, MSI is related to enhanced lymphocyte infiltration accompanied by a Crohn-like reaction (CLR) in MSI-high cancer. This finding suggests that highly immunogenic neoantigens are expressed in MSI-H tumor cells, and the result also showed that patients with MSI-high had better survival than MSI-low and MSS tumors [43]. Concordantly, our findings showed that CCA patients who had a high level of both MSI and TILs were associated with a good outcome when compared with individuals with another status. Moreover, high levels of MSI and TILs are an independent factor for the good survival of CCA patients. Although our study only involved curative surgery and there were no neoadjuvant treatments (chemotherapy or immunotherapy), the outcome of CCA patients with high MSI and TILs was better than the survival of low MSI, other MSI, and TILs. Because patients with an immune response against foreign cells, especially cancer cells, usually show symptoms of illness, early diagnosis is probably performed earlier to detect the disease. This is related to our finding that 52% of CCA patients with MSI-high presented with early-stage disease. CCA with MSI-low or low mutation tumors may produce a smaller amount of neoantigen, resulting in avoidance of immune detection. Our results showed that almost all CCA patients with MSI-low presented with late-stage disease. The association of MSI-high with TILs and the early stage of cancer has been found in colon cancer [44,45]. In addition, endometrial carcinomas have revealed the relationship between MSI-high and early stages of cancer [33]. Although our findings proposed MSI-high was associated with good clinical outcomes, as found in the previous reports, there are some studies that have conflicting results [46,47]. Therefore, this result should be validated using a larger number of cases.

The limitations of this study are (i) the small number of patients in the low level of MSI or the combination of the low level of the MSI and TIL groups, which do not adequately represent the rest of the patient population. Further analysis with a larger number of MSI-low or a combination of low levels of MSI and TILs should be performed. (ii) Our findings come from a single institution in Northeast Thailand. Internal and external validation should be performed to confirm this finding. (iii) There is no information relating to chemotherapy or immunotherapy in this study because the major treatment of our cohort was partial hepatectomy. Therefore, it is difficult to explain the good outcome in high MSI and TILs after surgery. This information may be of clinical benefit in chemotherapy or immunotherapy. (iv) Because of the small number of patients investigated with MSI and MMR protein status, no association between these factors could be found.

To address these limitations, future studies will include larger and more diverse cohorts to validate the findings, perform multicenter internal and external validation to improve generalizability, integrate treatment information, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy, to clarify prognostic and therapeutic relevance, and apply multi-omics approaches with expanded sample sizes to further elucidate the biological mechanisms linking MSI, MMR, and immune responses in CCA.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the present study indicates that most of the population of OV-associated CCA is MSI-high in the study cohort, which is positively correlated with a good prognosis and response to treatment following surgery. In addition, MSI-high is associated with good outcomes of clinicopathological features such as growth pattern with ID components, papillary types, and early stage of CCA. We also demonstrated that the MSI-high phenotype is significantly associated with OV infection, which is a major cause of mutation in CCA patients in Northeastern Thailand. In addition, the incorporation of MSI and TILs, which is correlated with the survival of patients by MSI-high and high levels of TILs, favors good survival, while other subclassifications, especially MSI-low and low levels of TILs, have poor survival outcomes. Furthermore, MSI and TILs also act as independent factors for the prognosis of the survival outcome of CCA patients in this study. Therefore, further studies are needed to validate this result. We expect that the subtype of CCA with MSI-high and high levels of TILs may be more susceptible to a treatment plan with surgery, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy after validation on a larger scale and in other cohorts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmp6040030/s1, Figure S1: Representative immunohistochemical staining of MMR status in a vertical layout. Panel 1 shows negative expression of MLH1 and MSH2 in the same case, whereas Panel 2 shows positive expression of MLH1 and MSH2 in the same case. Immunohistochemical staining; original magnification, ×200; scale bar = 50 µm.; Figure S2: Representative figure of proportions of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the stroma of cholangiocarcinoma cases.; Table S1: Sub-models of multivariate Cox regression analysis for overall survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., S.P., W.L., P.K. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); funding acquisition, A.T. (Attapol Titapun); sample collection and diagnosis, N.K., A.J., V.T., T.S., V.L., J.C., P.S.-N., C.A. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); analysis and interpretation of data, N.K., S.P., W.L., P.K., A.T. (Anchalee Techasen), P.P. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); investigation, N.K., S.P., P.K. and P.P.; resources W.L., P.K. and A.T. (Anchalee Techasen); data curation, A.J., V.T., T.S., V.L., J.C., P.S.-N., C.A. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); project administration, A.T. (Attapol Titapun); supervision, W.L. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); validation, N.K., S.P., W.L., P.K., A.T. (Anchalee Techasen), A.J., V.T., T.S., V.L., J.C., P.S.-N., C.A., P.P. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun); writing—original draft, N.K., S.P. and P.P.; writing—review and editing, W.L., P.K., A.T. (Anchalee Techasen), P.P. and A.T. (Attapol Titapun). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Fund of Khon Kaen University, supported by the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), allocated to Dr. Attapol Titapun.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University (protocol code HE641363; approved 29 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and applicable national regulations for clinical research. The study used archived, de-identified tissue and serum samples and associated clinical data from the Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute (CARI), Khon Kaen University. No new patient recruitment or additional informed consent was required. All clinical data and medical records were anonymized, with participants identified solely by hospital numbers (HNs) to ensure confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets created and analyzed in this study are not publicly accessible because of ethical agreements concerning participant privacy. However, data sharing options can be discussed by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the late Narong Khuntikeo (Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, and Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute, Khon Kaen University, Thailand) and the Cholangiocarcinoma Screening and Care Program (CASCAP) team for their valuable discussions. We also appreciate Bandit Thinkhamrop (Data Management and Statistical Analysis Center, Faculty of Public Health, Khon Kaen University) for his guidance on statistical analyses. Our gratitude extends to all CASCAP members, particularly cohort participants and CARI researchers, for their assistance in data collection and verification. We also thank Trevor N. Petney for his editorial support through the Publication Clinic, KKU, Thailand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuntikeo, N.; Pugkhem, A.; Titapun, A.; Bhudhisawasdi, V. Surgical management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A Khon Kaen experience. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2014, 21, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titapun, A.; Pugkhem, A.; Luvira, V.; Srisuk, T.; Somintara, O.; Saeseow, O.T.; Sripanuskul, A.; Nimboriboonporn, A.; Thinkhamrop, B.; Khuntikeo, N. Outcome of curative resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in Northeast Thailand. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 7, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripa, B.; Kaewkes, S.; Sithithaworn, P.; Mairiang, E.; Laha, T.; Smout, M.; Pairojkul, C.; Bhudhisawasdi, V.; Tesana, S.; Thinkamrop, B.; et al. Liver fluke induces cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titapun, A.; Techasen, A.; Sa-Ngiamwibool, P.; Sithithaworn, P.; Luvira, V.; Srisuk, T.; Jareanrat, A.; Dokduang, H.; Loilome, W.; Thinkhamrop, B.; et al. Serum IgG as a Marker for Opisthorchis viverrini-Associated Cholangiocarcinoma Correlated with HER2 Overexpression. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongvanit, P.; Pinlaor, S.; Bartsch, H. Oxidative and nitrative DNA damage: Key events in opisthorchiasis-induced carcinogenesis. Parasitol. Int. 2012, 61, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanan, R.; Murata, M.; Pinlaor, S.; Sithithaworn, P.; Khuntikeo, N.; Tangkanakul, W.; Hiraku, Y.; Oikawa, S.; Yongvanit, P.; Kawanishi, S. Urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine in patients with parasite infection and effect of antiparasitic drug in relation to cholangiocarcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Ramos, M.A. Satellite DNA: An Evolving Topic. Genes 2017, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nojadeh, J.N.; Behrouz Sharif, S.; Sakhinia, E. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Imai, K. Microsatellite instability: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 899–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, V.A.; Madlensky, L.; Gryfe, R.; Kim, H.; So, K.; Millar, A.; Temple, L.K.; Hsieh, E.; Hiruki, T.; Narod, S.; et al. Immunohistochemistry for hMLH1 and hMSH2: A practical test for DNA mismatch repair-deficient tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999, 23, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, C.R.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Hamilton, S.R.; Sidransky, D.; Eshleman, J.R.; Burt, R.W.; Meltzer, S.J.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Fodde, R.; Ranzani, G.N. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: Development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5248–5257. [Google Scholar]

- Abida, W.; Cheng, M.L.; Armenia, J.; Middha, S.; Autio, K.A.; Vargas, H.A.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.J.; Danila, D.C.; Slovin, S.F.; et al. Analysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, D.J.; Marsoni, S.; Monges, G.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Labianca, R.; Hamilton, S.R.; French, A.J.; Kabat, B.; Foster, N.R.; Torri, V.; et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3219–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.T.; Das, S. Pembrolizumab in unresectable or metastatic MSI-high colorectal cancer: Safety and efficacy. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2021, 21, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howitt, B.E.; Shukla, S.A.; Sholl, L.M.; Ritterhouse, L.L.; Watkins, J.C.; Rodig, S.; Stover, E.; Strickland, K.C.; D’Andrea, A.D.; Wu, C.J.; et al. Association of Polymerase e-Mutated and Microsatellite-Instable Endometrial Cancers with Neoantigen Load, Number of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes, and Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Murphy, A.; Le, D.T.; Diaz, L.A., Jr. Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Oncologist 2016, 21, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J.C.; Lin, M.T.; Le, D.T.; Eshleman, J.R. Microsatellite Instability as a Biomarker for PD-1 Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Chen, H.; Bai, X. Relationship between microsatellite status and immune microenvironment of colorectal cancer and its application to diagnosis and treatment. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e23810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loilome, W.; Kadsanit, S.; Muisook, K.; Yongvanit, P.; Namwat, N.; Techasen, A.; Puapairoj, A.; Khuntikeo, N.; Phonjit, P. Imbalanced adaptive responses associated with microsatellite instability in cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goeppert, B.; Roessler, S.; Renner, M.; Singer, S.; Mehrabi, A.; Vogel, M.N.; Pathil, A.; Czink, E.; Kohler, B.; Springfeld, C.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency is a rare but putative therapeutically relevant finding in non-liver fluke associated cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, S.; Salgado, R.; Gevaert, T.; Russell, P.A.; John, T.; Thapa, B.; Christie, M.; van de Vijver, K.; Estrada, M.V.; Gonzalez-Ericsson, P.I.; et al. Assessing Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Solid Tumors: A Practical Review for Pathologists and Proposal for a Standardized Method from the International Immunooncology Biomarkers Working Group: Part 1: Assessing the Host Immune Response, TILs in Invasive Breast Carcinoma and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Metastatic Tumor Deposits and Areas for Further Research. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2017, 24, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intarawichian, P.; Sangpaibool, S.; Prajumwongs, P.; Sa-Ngiamwibool, P.; Sangkhamanon, S.; Kunprom, W.; Thanee, M.; Loilome, W.; Khuntikeo, N.; Titapun, A.; et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in predicting outcome of distal cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1004220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa-Ngiamwibool, P.; Aphivatanasiri, C.; Sangkhamanon, S.; Intarawichian, P.; Kunprom, W.; Thanee, M.; Prajumwongs, P.; Loilome, W.; Khuntikeo, N.; Titapun, A.; et al. Modification of the AJCC/UICC 8th edition staging system for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Proposal for an alternative staging system from cholangiocarcinoma-prevalent Northeast Thailand. HPB 2022, 24, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsuksantigul, P. Study on prevalence and intensity of intestinal helminthiasis and opisthorchiasis in Thailand. J. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1992, 15, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tesana, S.; Srisawangwong, T.; Sithithaworn, P.; Itoh, M.; Phumchaiyothin, R. The ELISA-based detection of anti-Opisthorchis viverrini IgG and IgG4 in samples of human urine and serum from an endemic area of north-eastern Thailand. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2007, 101, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: Potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpaiboon, T.; Krissadarak, K.; Sripa, B.; Jearanaikoon, P.; Bhuhisawasdi, V.; Chau-in, S.; Romphruk, A.; Pairojkul, C. Microsatellite alterations in liver fluke related cholangiocarcinoma are associated with poor prognosis. Cancer Lett. 2002, 181, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, A.R.; Hamilton, S.R.; Allegra, C.J.; Grody, W.; Cushman-Vokoun, A.M.; Funkhouser, W.K.; Kopetz, S.E.; Lieu, C.; Lindor, N.M.; Minsky, B.D.; et al. Molecular Biomarkers for the Evaluation of Colorectal Cancer: Guideline from the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Association for Molecular Pathology, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1453–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre, T.; Shiu, K.K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basil, J.B.; Goodfellow, P.J.; Rader, J.S.; Mutch, D.G.; Herzog, T.J. Clinical significance of microsatellite instability in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 89, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, M.; Ascierto, P.A.; Manzyuk, L.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Penel, N.; Cassier, P.A.; Bariani, G.M.; De Jesus Acosta, A.; Doi, T.; Longo, F.; et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient cancers: Updated analysis from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Luo, H.; Huang, L.; Luo, H.; Zhu, X. Microsatellite instability: A review of what the oncologist should know. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, L.; Lemery, S.J.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Microsatellite Instability-High Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3753–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesca, I.; Tunger, A.; Muller, L.; Wehner, R.; Lai, X.; Grimm, M.O.; Rutella, S.; Bachmann, M.; Schmitz, M. Characteristics of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Prior to and During Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Heij, L.R.; Czigany, Z.; Dahl, E.; Lang, S.A.; Ulmer, T.F.; Luedde, T.; Neumann, U.P.; Bednarsch, J. The role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cholangiocarcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xiong, J.; Lan, H.; Wang, F. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Colorectal Cancer: The Fundamental Indication and Application on Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 808964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnebacher, M.; Gebert, J.; Rudy, W.; Woerner, S.; Yuan, Y.P.; Bork, P.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M. Frameshift peptide-derived T-cell epitopes: A source of novel tumor-specific antigens. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 93, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.K.; Park, M.; Park, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Shin, N.; Kim, H.K.; You, K.T.; Kim, H. Identification and selective degradation of neopeptide-containing truncated mutant proteins in the tumors with high microsatellite instability. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3369–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Shen, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, Z.; Huang, C.; Fu, L. Neoantigens: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckowitz, A.; Knaebel, H.P.; Benner, A.; Blaker, H.; Gebert, J.; Kienle, P.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Kloor, M. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer is associated with local lymphocyte infiltration and low frequency of distant metastases. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenson, J.K.; Bonner, J.D.; Ben-Yzhak, O.; Cohen, H.I.; Miselevich, I.; Resnick, M.B.; Trougouboff, P.; Tomsho, L.D.; Kim, E.; Low, M.; et al. Phenotype of microsatellite unstable colorectal carcinomas: Well-differentiated and focally mucinous tumors and the absence of dirty necrosis correlate with microsatellite instability. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2003, 27, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhede, D.; Yuan, T.; Kloor, M.; Halama, N.; Brenner, H.; Hoffmeister, M. Clinical significance of combined tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and microsatellite instability status in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caduff, R.F.; Johnston, C.M.; Svoboda-Newman, S.M.; Poy, E.L.; Merajver, S.D.; Frank, T.S. Clinical and pathological significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic endometrial carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1996, 148, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, N.D.; Salvesen, H.B.; Ryan, A.; Iversen, O.E.; Akslen, L.A.; Jacobs, I.J. Frequency and prognostic impact of microsatellite instability in a large population-based study of endometrial carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 1750–1752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).