Molecular Perspective on Proteases: Regulation of Programmed Cell Death Signaling, Inflammation and Pathological Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Proteases in Regulating Homeostasis and Programmed Cell Death

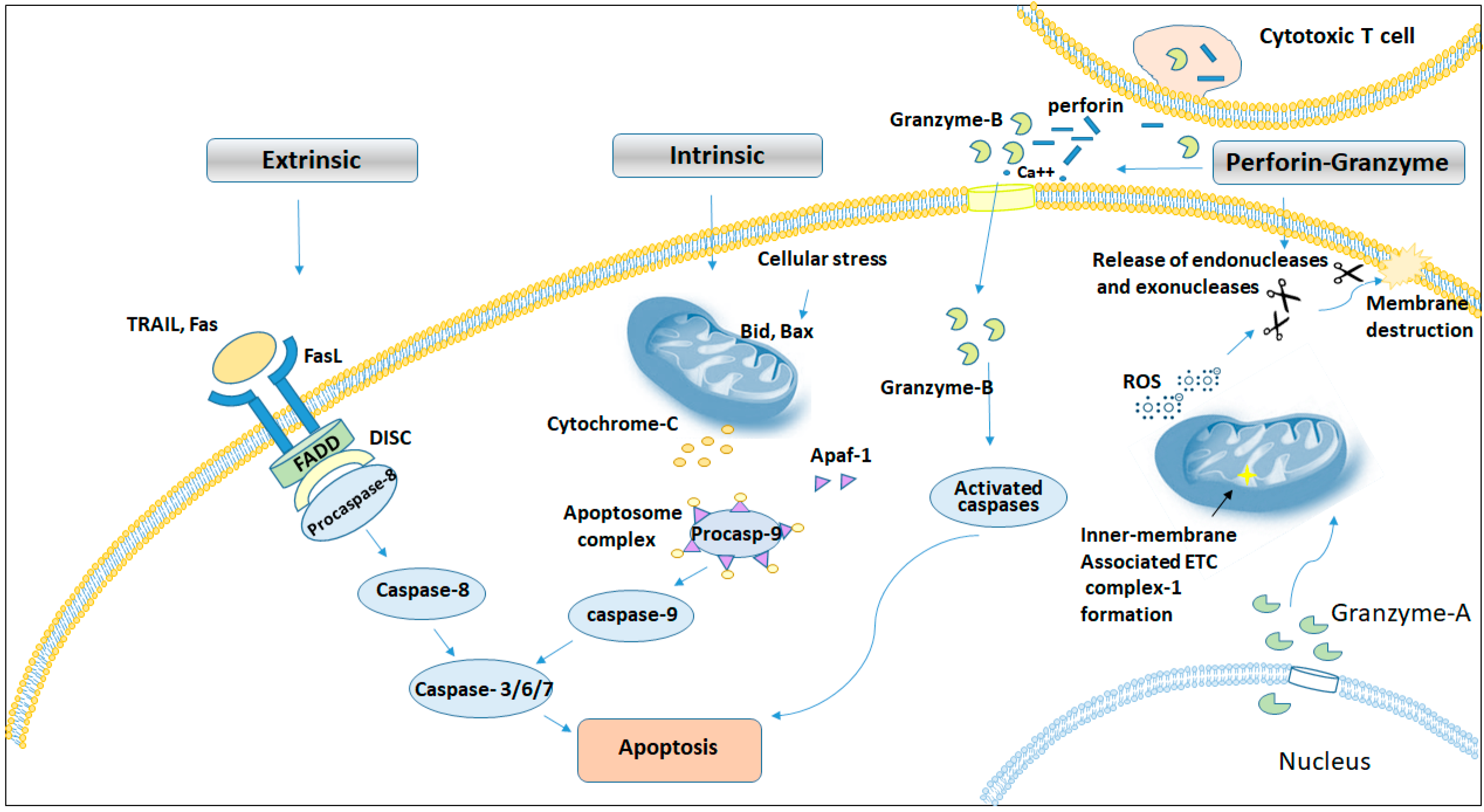

2.1. Proteases in Apoptosis

2.1.1. Calpains in Cell Death

2.1.2. Cathepsins and Their Role in Cell Death

2.1.3. Perforin-Granzyme Pathway in Cell Death

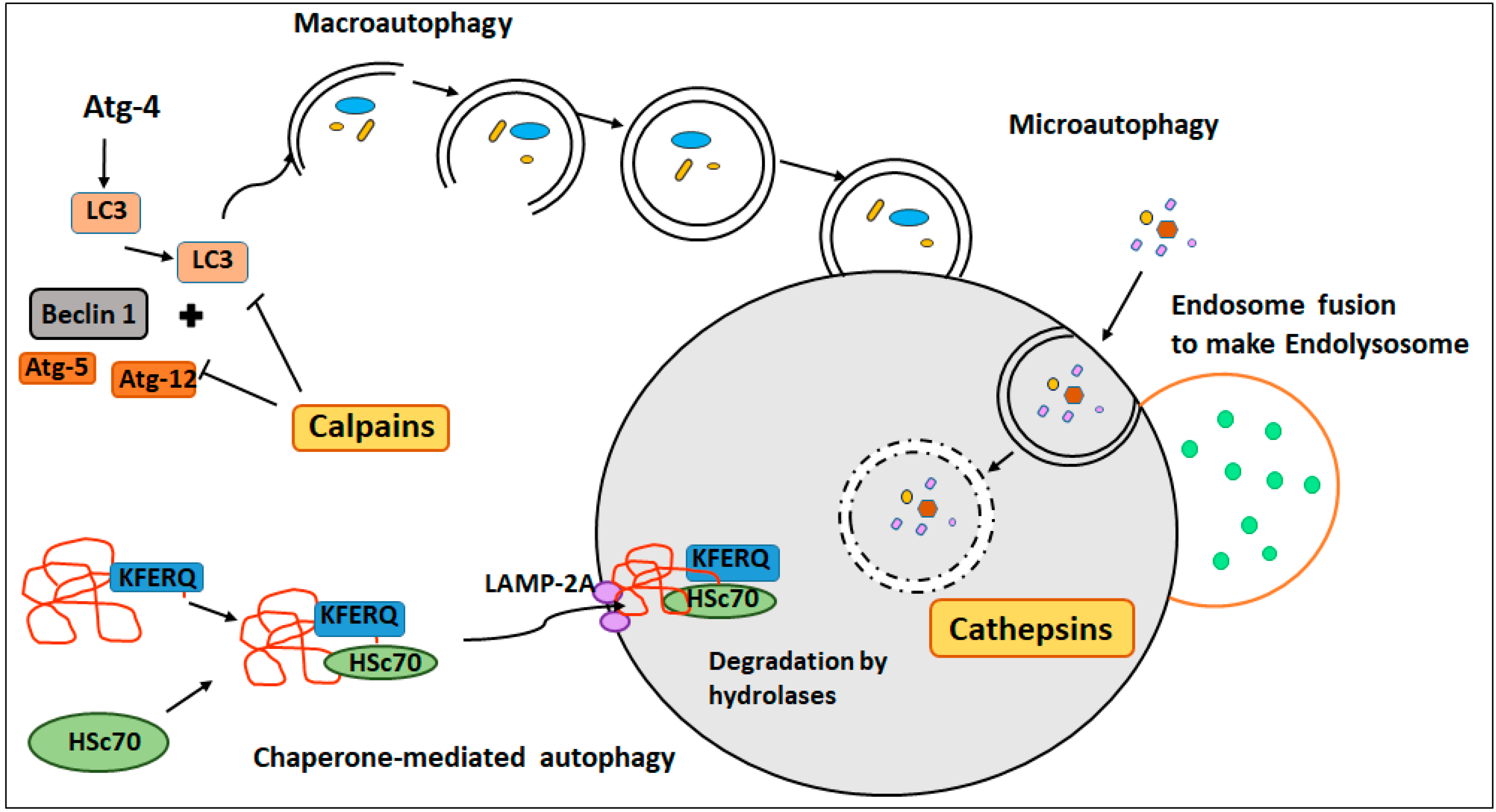

2.2. Proteases in Autophagy

2.2.1. Macroautophagy

2.2.2. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA)

2.2.3. Microautophagy

2.3. Proteases in Necrosis/Necroptosis

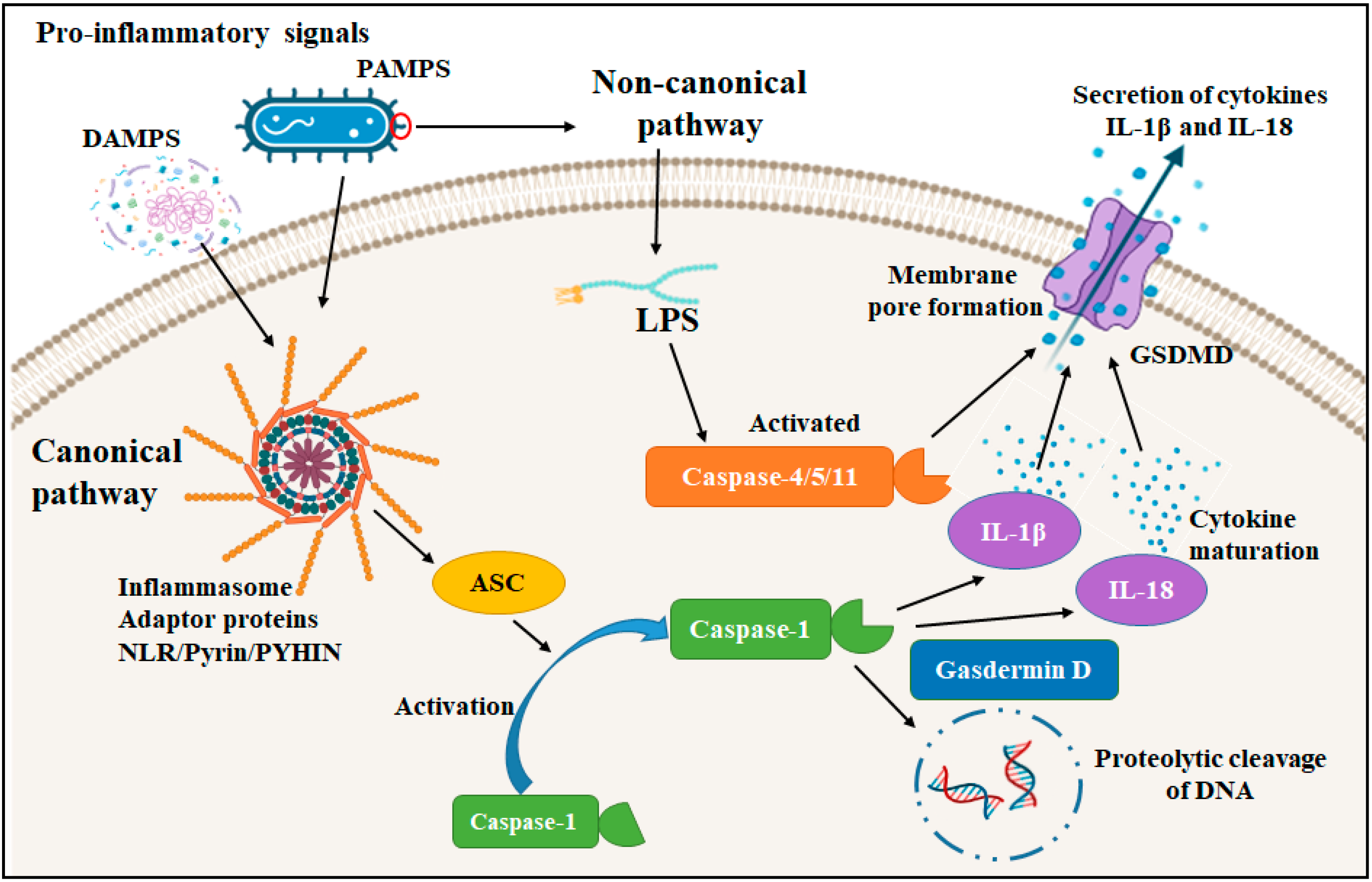

3. Proteases in Pyroptosis and Inflammation

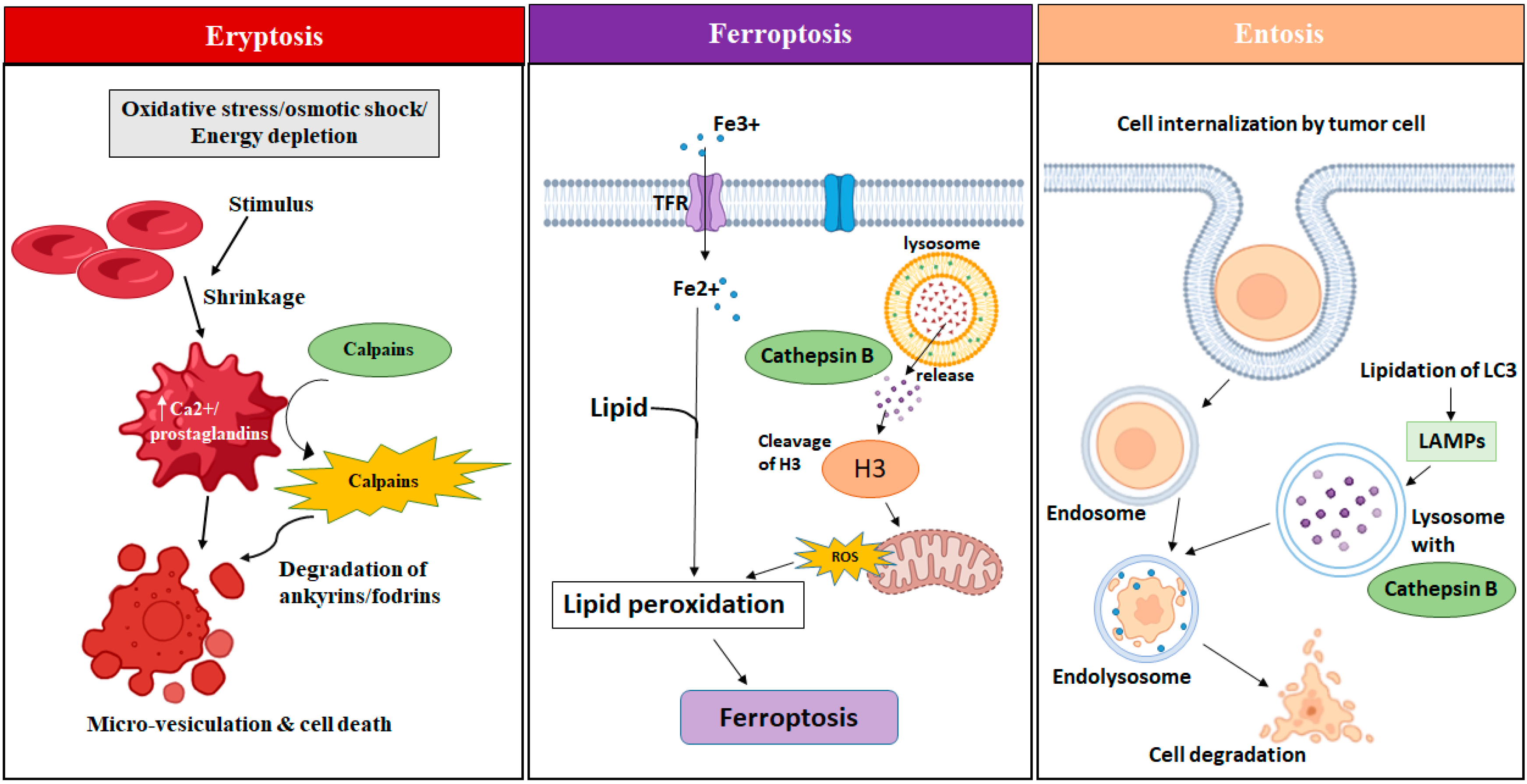

3.1. Eryptosis

3.2. Ferroptosis

3.3. Entosis

3.4. Oncosis

4. Proteases in ER Stress-Mediated Cell Death

5. Pathological Consequences of Protease Dysregulation

5.1. Proteases in Cancer and Tumor Progression

5.1.1. Serine Proteases

5.1.2. Cysteine Proteases

5.1.3. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Cancer

5.1.4. Aspartyl Proteases

5.2. Proteases in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders

5.3. Proteases in Metabolic Disorders (Diabetes, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis)

5.4. Proteases in Lung Disease: COPD and Pulmonary Emphysema

6. Therapeutic Implications of Proteases

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bond, J.S. Proteases: History, discovery, and roles in health and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Bond, J.S. Proteases: Multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 30433–30437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.; Gores, G.J.; Kaufmann, S.H. The role of proteases during apoptosis. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Silva, J.G.; Español, Y.; Velasco, G.; Quesada, V. The Degradome database: Expanding roles of mammalian proteases in life and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D351–D355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, V.; Ordonez, G.R.; Sanchez, L.M.; Puente, X.S.; Lopez-Otin, C. The Degradome database: Mammalian proteases and diseases of proteolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D239–D243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, H.; Walsh, K.A.; Winter, W.P. Evolution of structure and function of proteases. Science 1967, 158, 1638–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumallesh, P.; Alagu, K.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Muthusamy, S. A systematic reconsideration on proteases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, H.; Walsh, K.A. Role of proteolytic enzymes in biological regulation (a review). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3825–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicencio, J.M.; Galluzzi, L.; Tajeddine, N.; Ortiz, C.; Criollo, A.; Tasdemir, E.; Morselli, E.; Ben Younes, A.; Maiuri, M.C.; Lavandero, S.; et al. Senescence, apoptosis or autophagy? When a damaged cell must decide its path—A mini-review. Gerontology 2008, 54, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousalova, I.; Krepela, E. Granzyme B-induced apoptosis in cancer cells and its regulation (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 37, 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagirasa, R.; Yoo, E. Role of Serine Proteases at the Tumor-Stroma Interface. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 832418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapani, J.A.; Smyth, M.J. Functional significance of the perforin/granzyme cell death pathway. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, J. Proteases: Role and Function in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willbold, R.; Wirth, K.; Martini, T.; Sultmann, H.; Bolenz, C.; Wittig, R. Excess hepsin proteolytic activity limits oncogenic signaling and induces ER stress and autophagy in prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, Z. Proteases and Cancer Development. In Role of Proteases in Cellular Dysfunction; Dhalla, N.S., Chakraborti, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y.; Imai, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Takahashi, K.; Takio, K.; Takahashi, R. A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummari, R.; Dutta, S.; Chaganti, L.K.; Bose, K. Discerning the mechanism of action of HtrA4: A serine protease implicated in the cell death pathway. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 1445–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droga-Mazovec, G.; Bojic, L.; Petelin, A.; Ivanova, S.; Romih, R.; Repnik, U.; Salvesen, G.S.; Stoka, V.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins trigger caspase-dependent cell death through cleavage of Bid and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologues. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19140–19150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizovisek, M.; Fonovic, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins in extracellular matrix remodeling: Extracellular matrix degradation and beyond. Matrix Biol. 2019, 75–76, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.X.; Li, X.P.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.F.; Mehta, S.; Feng, Q.P.; Chen, R.Z.; Peng, T.Q. Calpain-1 induces apoptosis in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells under septic conditions. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavardhana, S.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, J.; Luo, R.H.; Metz, S.A.; Li, G. Activation of caspase-2 mediates the apoptosis induced by GTP-depletion in insulin-secreting (HIT-T15) cells. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amptoulach, S.; Lazaris, A.C.; Giannopoulou, I.; Kavantzas, N.; Patsouris, E.; Tsavaris, N. Expression of caspase-3 predicts prognosis in advanced noncardia gastric cancer. Med. Oncol. 2015, 32, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.H.; Fang, W.L.; Li, A.F.Y.; Liang, P.H.; Wu, C.W.; Shy, Y.M.; Yang, M.H. Caspase-3, a key apoptotic protein, as a prognostic marker in gastric cancer after curative surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 52, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajiwara, Y.; Schiff, T.; Voloudakis, G.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; Elder, G.; Bozdagi, O.; Buxbaum, J.D. A critical role for human caspase-4 in endotoxin sensitivity. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, S.; Dorstyn, L.; Dawar, S.; Kumar, S. Old, new and emerging functions of caspases. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, A.; Nulty, C.; Creagh, E.M. Regulation, Activation and Function of Caspase-11 during Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Opdenbosch, N.; Lamkanfi, M. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchem, G.; Glondu, M.; Gleizes, M.; Brouillet, J.P.; Vignon, F.; Garcia, M.; Liaudet-Coopman, E. Cathepsin-D affects multiple tumor progression steps in vivo: Proliferation, angiogenesis and apoptosis. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5951–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudet-Coopman, E.; Beaujouin, M.; Derocq, D.; Garcia, M.; Glondu-Lassis, M.; Laurent-Matha, V.; Prébois, C.; Rochefort, H.; Vignon, F. Cathepsin D: Newly discovered functions of a long-standing aspartic protease in cancer and apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2006, 237, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolosowicz, M.; Prokopiuk, S.; Kaminski, T.W. The Complex Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Barchuk, M.; Miksztowicz, V. Behavior of Metalloproteinases in Adipose Tissue, Liver and Arterial Wall: An Update of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. Cells 2019, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Cellular Dynamics of Fas-Associated Death Domain in the Regulation of Cancer and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Surolia, A.; Pathak, C. Apoptotic potential of Fas-associated death domain on regulation of cell death regulatory protein cFLIP and death receptor mediated apoptosis in HEK 293T cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2012, 6, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukharev, S.A.; Pleshakova, O.V.; Sadovnikov, V.B. Role of proteases in activation of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1997, 4, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, V.J.; Lathi, J.M.; Teitz, T. Proteolytic regulation of apoptosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000, 11, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanumula, A.; Cusick, J.K. Biochemistry, Extrinsic Pathway of Apoptosis. 31 July 2023. In StatPearls; Ineligible Companies: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, K.; Waghela, B.N.; Vaidya, F.U.; Pathak, C. Cell-Penetrable Peptide-Conjugated FADD Induces Apoptosis and Regulates Inflammatory Signaling in Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Expression of FADD and cFLIP(L) balances mitochondrial integrity and redox signaling to substantiate apoptotic cell death. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 422, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. FADD regulates NF-kappaB activation and promotes ubiquitination of cFLIPL to induce apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, J.F.; Saggau, C.; Adam, D. Proteolytic control of regulated necrosis. BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 2147–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, K.; Sharma, A.; Surolia, A.; Pathak, C. Regulation of HA14-1 mediated oxidative stress, toxic response, and autophagy by curcumin to enhance apoptotic activity in human embryonic kidney cells. Biofactors 2014, 40, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.A.; Schnellmann, R.G. Calpains, mitochondria, and apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 96, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingrave, J.M.; Schaecher, K.E.; Sribnick, E.A.; Wilford, G.G.; Ray, S.K.; Hazen-Martin, D.J.; Hogan, E.L.; Banik, N.L. Early induction of secondary injury factors causing activation of calpain and mitochondria-mediated neuronal apoptosis following spinal cord injury in rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 73, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, A.; Agarwal, R.; Botez, G.; Winckler, J. μ-Calpain activation, DNA fragmentation, and synergistic effects of caspase and calpain inhibitors in protecting hippocampal neurons from ischemic damage. Brain Res. 2000, 866, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, H.R. Role of Calpain in Apoptosis. Cell J. 2011, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chwieralski, C.E.; Welte, T.; Bühling, F. Cathepsin-regulated apoptosis. Apoptosis 2006, 11, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J. Granzyme A activates another way to die. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 235, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, J.G.; Lopus, M. Cell death mechanisms in eukaryotes. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2020, 36, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaminskyy, V.; Zhivotovsky, B. Proteases in autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1824, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Expression of cFLIPL Determines the Basal Interaction of Bcl-2 With Beclin-1 and Regulates p53 Dependent Ubiquitination of Beclin-1 During Autophagic Stress. J. Cell Biochem. 2016, 117, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Shibutani, S.T.; Saitoh, T.; Nowag, H.; Munz, C.; Yoshimori, T. Autophagy and autophagy-related proteins in the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, T.L.A.; Serrao, T.; Goncalves, A.; Pinto, E.F.; Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Pirmez, C.; Pereira, L.O.R.; Menna-Barreto, R.F.S. Leishmania (V.) braziliensis infection promotes macrophage autophagy by a LC3B-dependent and BECLIN1-independent mechanism. Acta Trop. 2021, 218, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Yan, J.; Ranjan, K.; Zhang, X.; Turner, J.R.; Abraham, C. Myeloid Cell Expression of LACC1 Is Required for Bacterial Clearance and Control of Intestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Sridhar, S.; Kiffin, R.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Kon, M.; Orenstein, S.J.; Wong, E.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, U.; Kaushik, S.; Varticovski, L.; Cuervo, A.M. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 5747–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, G.E.; Lardeux, B.R.; Adams, C.E. Regulation of Microautophagy and Basal Protein-Turnover in Rat-Liver—Effects of Short-Term Starvation. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, C.; Vaidya, F.U.; Waghela, B.N.; Jaiswara, P.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Rajendran, B.K.; Ranjan, K. Insights of Endocytosis Signaling in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numrich, J.; Péli-Gulli, M.P.; Arlt, H.; Sardu, A.; Griffith, J.; Levine, T.; Engelbrecht-Vandré, S.; Reggiori, F.; De Virgilio, C.; Ungermann, C. The I-BAR protein Ivy1 is an effector of the Rab7 GTPase Ypt7 involved in vacuole membrane homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2278–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekirdag, K.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy and endosomal microautophagy: Jointed by a chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 5414–5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendler, M.; Mayerle, J.; Lerch, M.M. Necrosis, Apoptosis, Necroptosis, Pyroptosis: It Matters How Acinar Cells Die During Pancreatitis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Choksi, S.; Li, W.H.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, Z.G. Activation of cell-surface proteases promotes necroptosis, inflammation and cell migration. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 886–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.O.; Behl, B.; Rathinam, V.A. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 69, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Karch, J. Regulation of cell death in the cardiovascular system. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 353, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pathak, C.; Vaidya, F.U.; Waghela, B.N.; Chhipa, A.S.; Tiwari, B.S.; Ranjan, K. Advanced Glycation End Products Mediated Oxidative Stress and Regulated Cell Death Signaling in Cancer. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ray, B.K., Roychowdhury, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Waghela, B.N.; Vaidya, F.U.; Ranjan, K.; Chhipa, A.S.; Tiwari, B.S.; Pathak, C. AGE-RAGE synergy influences programmed cell death signaling to promote cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, S.A.; Palaniyandi, T.; Parthasarathy, U.; Surendran, H.; Viswanathan, S.; Wahab, M.R.A.; Baskar, G.; Natarajan, S.; Ranjan, K. Implications of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and their signaling mechanisms in human cancers. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 248, 154673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Chen, H.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, K.L.; Zhuge, Y.Z.; Niu, C.; Qiu, J.X.; Rong, X.; Shi, Z.W.; Xiao, J.; et al. Role of pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 67, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.T.; Xiong, S.Q.; Ye, Z.M.; Hong, Z.G.; Di, A.K.; Tsang, K.M.; Gao, X.P.; An, S.J.; Mittal, M.; Vogel, S.M.; et al. Caspase-11-mediated endothelial pyroptosis underlies endotoxemia-induced lung injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 4124–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, R.; Ouyang, Y.; Gu, W.; Xiao, T.; Yang, H.; Tang, L.; Wang, H.; Xiang, B.; Chen, P. Pyroptosis in health and disease: Mechanisms, regulation and clinical perspective. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra, S.S.; Colomo, S.; Sin, L.; Perez-Lopez, M.; Lazaro, S.; Molina-Crespo, A.; Choi, K.H.; Ros-Pardo, D.; Martinez, L.; Morales, S.; et al. Distinct GSDMB protein isoforms and protease cleavage processes differentially control pyroptotic cell death and mitochondrial damage in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Chen, R. The Versatile Gasdermin Family: Their Function and Roles in Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 751533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, Q.; Zhong, X.; Zeng, M.; Zeng, H.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Shao, F.; et al. Structural Mechanism for GSDMD Targeting by Autoprocessed Caspases in Pyroptosis. Cell 2020, 180, 941–955.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.M.; Sullivan, G.P.; Moran, H.B.T.; Henry, C.M.; Reeves, E.P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Lavelle, E.C.; Martin, S.J. Extracellular Neutrophil Proteases Are Efficient Regulators of IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 Cytokine Activity but Poor Effectors of Microbial Killing. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2937–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Gao, W.; Shao, F. Pyroptosis: Gasdermin-Mediated Programmed Necrotic Cell Death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xu, S.; Jiang, R.; Yu, Y.; Bian, J.; Zou, Z. The gasdermin family: Emerging therapeutic targets in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Xie, F.; Zhou, X.X.; Wu, Y.C.; Yan, H.Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Wang, F.W.; Zhou, F.F.; Zhang, L. Role of pyroptosis in inflammation and cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadri, S.M.; Bissinger, R.; Solh, Z.; Oldenborg, P.A. Eryptosis in health and disease: A paradigm shift towards understanding the (patho)physiological implications of programmed cell death of erythrocytes. Blood Rev. 2017, 31, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föller, M.; Huber, S.M.; Lang, F. Erythrocyte programmed cell death. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Gulbins, E.; Lerche, H.; Huber, S.M.; Kempe, D.S.; Föller, M. Eryptosis, a Window to Systemic Disease. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 22, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreischer, P.; Duszenko, M.; Stein, J.; Wieder, T. Eryptosis: Programmed Death of Nucleus-Free, Iron-Filled Blood Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarrese, P.; Straface, E.; Pietraforte, D.; Gambardella, L.; Vona, R.; Maccaglia, A.; Minetti, M.; Malorni, W. Peroxynitrite induces senescence and apoptosis of red blood cells through the activation of aspartyl and cysteinyl proteases. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, F.C.; Maté, S.; Bakás, L.; Herlax, V. Induction of eryptosis by low concentrations of E. coli alpha-hemolysin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2015, 1848, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.P.; Engels, I.H.; Rothbart, A.; Lauber, K.; Renz, A.; Schlosser, S.F.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Wesselborg, S. Human mature red blood cells express caspase-3 and caspase-8, but are devoid of mitochondrial regulators of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagakannan, P.; Islam, M.I.; Conrad, M.; Eftekharpour, E. Cathepsin B is an executioner of ferroptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.H.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G.; Tang, D.L. Cellular degradation systems in ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overholtzer, M.; Mailleux, A.A.; Mouneimne, G.; Normand, G.; Schnitt, S.J.; King, R.W.; Cibas, E.S.; Brugge, J.S. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell 2007, 131, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Overholtzer, M. Mechanisms and consequences of entosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2379–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgan, J.; Florey, O. Cancer cell cannibalism: Multiple triggers emerge for entosis. BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, W.T.; Mai, F.Y.; Liang, J.R.; Luo, J.; Zhou, M.C.; Yu, D.D.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, C.G. Unravelling oncosis: Morphological and molecular insights into a unique cell death pathway. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1450998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Van Vleet, T.; Schnellmann, R.G. The role of calpain in oncotic cell death. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. 2004, 44, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetz, C.; Papa, F.R. The Unfolded Protein Response and Cell Fate Control. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Hedl, M.; Abraham, C. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF186 and RNF186 risk variants regulate innate receptor-induced outcomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2013500118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, K.; Hedl, M.; Sinha, S.; Zhang, X.; Abraham, C. Ubiquitination of ATF6 by disease-associated RNF186 promotes the innate receptor-induced unfolded protein response. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e145472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Xu, W.J.; Reed, J.C. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: Disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hedl, M.; Ranjan, K.; Abraham, C. LACC1 Required for NOD2-Induced, ER Stress-Mediated Innate Immune Outcomes in Human Macrophages and LACC1 Risk Variants Modulate These Outcomes. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 4525–4539.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, K. Intestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Perspective on Intracellular Response Mechanisms. Gastrointest. Disord. 2020, 2, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, K.F.; Kroemer, G. Organelle-specific initiation of cell death pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, E255–E263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, T. Caspases involved in ER stress-mediated cell death. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2004, 28, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Yuan, J.Y. Cross-talk between two cysteine protease families: Activation of caspase-12 by calpain in apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 150, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Vaillancourt, J.P.; Graham, R.K.; Huyck, M.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Steinberg, M.H.; Nolan, V.; Baldwin, C.T.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; et al. Differential modulation of endotoxin responsiveness by human caspase-12 polymorphisms. Nature 2004, 429, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblinski, J.E.; Ahram, M.; Sloane, B.F. Unraveling the role of proteases in cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 291, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.E.; List, K. Cell surface-anchored serine proteases in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metast. Rev. 2019, 38, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzki, L.; Schmitt, M.; Mann, K.; Calvete, J.; Chucholowski, N.; Kramer, M.; Gunzler, W.A.; Janicke, F.; Graeff, H. Effective Activation of the Proenzyme Form of the Urokinase-Type Plasminogen-Activator (Pro-Upa) by the Cysteine Protease Cathepsin-L. FEBS Lett. 1992, 297, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, T.; Robitaille, M.; Roberts-Thomson, S.J.; Monteith, G.R. The intersection between cysteine proteases, Ca2+signalling and cancer cell apoptosis*. BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2023, 1870, 119532. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, X.J.; Li, Z.H.; Huang, Q.; Li, F.; Li, C.Y. Caspase-3 regulates the migration, invasion and metastasis of colon cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 921–930. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, Y.I.; Kuranaga, E. Caspase-dependent non-apoptotic processes in development. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Koga, H.; Araki, N.; Mugita, N.; Fujita, N.; Takeshima, H.; Nishi, T.; Yamashima, T.; Saido, T.C.; Yamasaki, T.; et al. The involvement of calpain-dependent proteolysis of the tumor suppressor NF2 (merlin) in schwannomas and meningiomas. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikuttyamma, A.; Selvakumar, P.; Kanthan, R.; Kanthan, S.C.; Sharma, R.K. Overexpression of -calpain in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.K.; Gu, J.; Lu, C.L.; Mao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Q.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Chu, Y.W.; Liu, R.H.; Ge, D. Calpain-2 Enhances Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression and Chemoresistance to Paclitaxel via EGFR-pAKT Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, S.J.; Carragher, N.O.; Frame, M.C.; Parr, T.; Martin, S.G. The calpain system and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljeva, O.; Turk, B. Dual contrasting roles of cysteine cathepsins in cancer progression: Apoptosis versus tumour invasion. Biochimie 2008, 90, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soond, S.M.; Kozhevnikova, M.V.; Townsend, P.A.; Zamyatnin, A.A. Cysteine Cathepsin Protease Inhibition: An update on its Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonovic, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foghsgaard, L.; Wissing, D.; Mauch, D.; Lademann, U.; Bastholm, L.; Boes, M.; Elling, F.; Leist, M.; Jäättelä, M. Cathepsin B acts as a dominant execution protease in tumor cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, N.S.; Vigneswaran, N.; Zacharias, W. Cathepsin B mediates TRAIL-induced apoptosis in oral cancer cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. 2006, 132, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeblad, M.; Werb, Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, W.C.; Wilson, C.L.; López-Boado, Y.S. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-McCaw, A.; Ewald, A.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, A.; Jost, M.; Maquoi, E. Matrix metalloproteinases at cancer tumor-host interface. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 19, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cal, S.; López-Otín, C. ADAMTS proteases and cancer. Matrix Biol. 2015, 44–46, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocks, N.; Paulissen, G.; El Hour, M.; Quesada, F.; Crahay, C.; Gueders, M.; Foidart, J.M.; Noel, A.; Cataldo, D. Emerging roles of ADAM and ADAMTS metalloproteinases in cancer. Biochimie 2008, 90, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decock, J.; Hendrickx, W.; Thirkettle, S.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, A.; Robinson, S.D.; Edwards, D.R. Pleiotropic functions of the tumor- and metastasis-suppressing matrix metalloproteinase-8 in mammary cancer in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2015, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Quigley, J.P. Pleiotropic roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor angiogenesis: Contrasting, overlapping and compensatory functions. BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2010, 1803, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, G.; Lynch, C.C.; Fingleton, B. Moving targets: Emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis. Matrix Biol. 2015, 44–46, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gialeli, C.; Theocharis, A.D.; Karamanos, N.K. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Vázquez, J.; Corte, M.D.; Lamelas, M.; Bongera, M.; Corte, M.G.; Alvarez, A.; Allende, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Clinical significance of cathepsin D concentration in tumor cytosol of primary breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Marker 2005, 20, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetvicka, V.; Fusek, M. Procathepsin D as a tumor marker, anti-cancer drug or screening agent. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apoorva, O.S.; Shukla, K.; Khurana, A.; Chaudhary, N. Proteases: Role in Various Human Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2025, 26, 2257–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagami, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Koma, H. Pathophysiological Roles of Intracellular Proteases in Neuronal Development and Neurological Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 3090–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, V.Y. Neuroproteases in peptide neurotransmission and neurodegenerative diseases: Applications to drug discovery research. BioDrugs 2006, 20, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almajan, E.R.; Richter, R.; Paeger, L.; Martinelli, P.; Barth, E.; Decker, T.; Larsson, N.G.; Kloppenburg, P.; Langer, T.; Rugarli, E.I. AFG3L2 supports mitochondrial protein synthesis and Purkinje cell survival. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4048–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros, P.M.; Langer, T.; Lopez-Otin, C. New roles for mitochondrial proteases in health, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftig, P.; Bovolenta, P. Proteases at work: Cues for understanding neural development and degeneration. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, R.M. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujalled, D.; Strasser, A.; Liddell, J.R. Molecular mechanisms of cell death in neurological diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2029–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.H.; Kumar, S. Caspases in metabolic disease and their therapeutic potential. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H. Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs) and Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwilichowska, N.; Swiderska, K.W.; Dobrzyn, A.; Drag, M.; Poreba, M. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of protease inhibition. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 88, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waasdorp, M.; Duitman, J.; Florquin, S.; Spek, C.A.; Spek, A.C. Protease activated receptor 2 in diabetic nephropathy: A double edged sword. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 4512–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.E.; Jeong, S.K.; Lee, S.H. Protease and protease-activated receptor-2 signaling in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Yonsei Med. J. 2010, 51, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, F.; Ruf, W. Inflammation, obesity, and thrombosis. Blood 2013, 122, 3415–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, G.B.; Juliano, M.A.; Simoes, M.J.; Michelacci, Y.M. Lysosomal enzymes are decreased in the kidney of diabetic rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirea, A.M.; Toonen, E.J.M.; van den Munckhof, I.; Munsterman, I.D.; Tjwa, E.; Jaeger, M.; Oosting, M.; Schraa, K.; Rutten, J.H.W.; van der Graaf, M.; et al. Increased proteinase 3 and neutrophil elastase plasma concentrations are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes. Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Bridging inflammation and obesity-associated adipose tissue. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1381227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.V.; Michelotti, G.A.; Jewell, M.L.; Pereira, T.A.; Xie, G.; Premont, R.T.; Diehl, A.M. Caspase-2 promotes obesity, the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.V.; Cortez-Pinto, H. Cell death and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Where is ballooning relevant? Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 5, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Liao, S.; Hu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Sustained ER stress promotes hyperglycemia by increasing glucagon action through the deubiquitinating enzyme USP14. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21732–21738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvio, M.; Mononen, I. Aspartylglycosaminuria: A review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuinat, S.; Rollier, P.; Grand, K.; Sanchez-Lara, P.A.; Allen-Sharpley, M.; Levade, T.; Vanier, M.T.; Lion Francois, L.; Chemaly, N.; de Lattre, C.; et al. Acid Ceramidase Deficiency: New Insights on SMA-PME Natural History, Biomarkers, and In Cell Enzyme Activity Assay. Neurol. Genet. 2025, 11, e200243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matalon, R.; Surendran, S.; Rady, P.L.; Quast, M.J.; Campbell, G.A.; Matalon, K.M.; Tyring, S.K.; Wei, J.; Peden, C.S.; Ezell, E.L.; et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated aspartoacylase gene transfer to the brain of knockout mouse for canavan disease. Mol. Ther. 2003, 7, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Liang, Y.; Chang, H.; Cai, T.; Feng, B.; Gordon, K.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; He, Y.; Xie, L. Targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): From bench to bedside. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, I.; d’Azzo, A. Galactosialidosis: Historic aspects and overview of investigated and emerging treatment options. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 2017, 5, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Fan, C.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Zhu, L.; Jin, Y. Novel Compound Heterozygous TMPRSS15 Gene Variants Cause Enterokinase Deficiency. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 538778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Kavosi, A.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Mahjoub, G.; Faghihi, M.A.; Habibzadeh, P.; Yavarian, M. A novel stop-gain mutation in DPYS gene causing Dihidropyrimidinase deficiency, a case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2020, 21, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darin, N.; Leckstrom, K.; Sikora, P.; Lindgren, J.; Almen, G.; Asin-Cayuela, J. gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase deficiency caused by a large homozygous intragenic deletion in GGT1. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eni-Aganga, I.; Lanaghan, Z.M.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Dash, C.; Pandhare, J. PROLIDASE: A Review from Discovery to its Role in Health and Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 723003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, Y.; Zhang, S.; Kuninaka, Y.; Ishigami, A.; Nosaka, M.; Harie, I.; Kimura, A.; Mukaida, N.; Kondo, T. Essential Involvement of Neutrophil Elastase in Acute Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity Using BALB/c Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, T. Angio-oedema due to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency in children. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2013, 41, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, S.L.; Mathew, P. Alpha2-antiplasmin and its deficiency: Fibrinolysis out of balance. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.M. Proteases in the evaluation of pancreatic function and pancreatic disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 291, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanase, D.M.; Valasciuc, E.; Anton, I.B.; Gosav, E.M.; Dima, N.; Cucu, A.I.; Costea, C.F.; Floria, D.E.; Hurjui, L.L.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; et al. Matrix Metalloproteinases: Pathophysiologic Implications and Potential Therapeutic Targets in Cardiovascular Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T. Calpain and Cardiometabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.C.; De, S.; Mishra, P.K. Role of Proteases in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; Hunt, D.; Herron, M.; McDonnell, J.; Alshuhoumi, R.; McGarvey, L.P.; Fabre, A.; O’Brien, H.; McCarthy, C.; Martin, S.L.; et al. Neutrophil-Derived Peptidyl Arginine Deiminase Activity Contributes to Pulmonary Emphysema by Enhancing Elastin Degradation. J. Immunol. 2024, 213, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKelvey, M.C.; Brown, R.; Ryan, S.; Mall, M.A.; Weldon, S.; Taggart, C.C. Proteases, Mucus, and Mucosal Immunity in Chronic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, D.R.; Berger, T.; Mak, T.W. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.M.; Kanneganti, T.D. Converging roles of caspases in inflammasome activation, cell death and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demedts, I.K.; Demoor, T.; Bracke, K.R.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G. Role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of COPD and pulmonary emphysema. Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoari, A. From Bench to Bedside: Transforming Cancer Therapy with Protease Inhibitors. Targets 2025, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzinska, M.; Daglioglu, C.; Savvateeva, L.V.; Kaci, F.N.; Antoine, R.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. Current Status and Perspectives of Protease Inhibitors and Their Combination with Nanosized Drug Delivery Systems for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Kiso, Y. New directions for protease inhibitors directed drug discovery. Biopolymers 2016, 106, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Kalita, J.; Weldon, S.; Taggart, C.C. Proteases and Their Inhibitors in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, Y.; Ye, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Peng, C.; Huang, W.; He, G. Deubiquitinases as novel therapeutic targets for diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.E.; de la Torre Juarez, M.; Pla-Garcia, J.; Wilson, R.J.; Lewis, S.R.; Neary, L.; Kahre, M.A.; Forget, F.; Spiga, A.; Richardson, M.I.; et al. Multi-model Meteorological and Aeolian Predictions for Mars 2020 and the Jezero Crater Region. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protease | Role in Cell Death | References |

|---|---|---|

| Serine Proteases | ||

| Granzyme B | Catalyse the cleavage and activation of various downstream caspases, leading to apoptotic changes in target cell. | [10] |

| Granzyme H | Found to induce the release of pro-apoptotic proteins from the cell mitochondria. It can also catalyse DFF45/ICAD directly by proteolytic process. | [11] |

| Granzyme A | GrA does not triggers caspase-cascade, but appears to take part in cell death by targeting nuclear envelope protein and chromatin structural proteins. | [11] |

| Granzyme K | Accelerates rapid ROS generation and collapse inner membrane potential of mitochondria. It targets mitochondria by activating Bid into t-Bid which disrupts the outer membrane of mitochondria leading to cytochrome c release. | [12] |

| Granzyme M | Involved in both a caspase-dependent and a caspase-independent forms of apoptotic cell death in humans. Gzm M executes its cytotoxic function through cleavage of Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD). Cleaved FADD self-oligomerizes and associates with caspase-8, which is then processed into its active state to initiate the caspase cascade. | [12] |

| Hepsin | Using cyclin B, cyclin A, and a p53-dependent mechanism, hepsin causes cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. Hepsin also shows inhibitory effect on tumor cell growth. | [13,14] |

| HtrA2 | Increases apoptosis through a protease activity–dependent, caspase-mediated mechanism, which involves degradation of a critical anti-apoptotic molecule, XIAP (X-chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein). Promotes cell death by two distinct pathways. One involves direct interaction with IAPs (Inhibitor of Apoptotic Proteins) and inhibition of those molecules, which is accompanied by a marked increase in caspase activity. The other is via a serine protease activity-dependent, caspase-independent, and IAP inhibition-independent pathway. | [15,16] |

| HtrA4 | HtrA4 cleaves XIAP and induces apoptosis. XIAP is an anti-apoptotic protein, which interacts with downstream caspase-3 to stop the activation of the caspase cascade. | [17] |

| Cysteine Proteases | ||

| Cathepsins (B, C, F, H, K, L, O, S, V, X, W) | Known to cleave Bid protein involved in apoptosis. Also, cysteine cathepsins acts on anti-apoptotic family members of Bcl-2. Cathepsins were found to degrade E-cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule in cancer cells. | [18,19] |

| Caspase-1 | An inflammatory caspase that triggers pyroptosis Cleave pro-IL-1β during initiation of pyroptosis. | [20,21] |

| Caspase-2 | Involved in initiation of GTP-depletion induced apoptosis, in pancreatic β cells, also has a role in cancer cell death. Plays as an effector enzyme in activation of caspase-3 in DNA damage induced apoptosis. | [22] |

| Caspase-3 | Plays a major role in both extrinsic and intrinsic pathway, it can cleave more than 500 cellular substrates. Also helps in apoptotic chromatin condensation and cell dismantling. | [23,24] |

| Caspase-4 | Belong to family of Inflammatory caspases, play a critical role in interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) secretion, also associated with cell death. | [25] |

| Caspase-5 | A class of cytosolic cysteine protease, may play a role in innate immune response and inflammation. | [26,27,28] |

| Caspase-6 | An executioner caspase that mediates innate immunity and inflammasome activation. It is known to play role in activation of pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis. | |

| Caspase-7 | In intrinsic cell death pathway caspase-7 may be responsible for ROS production, accumulation and cell detachment. | |

| Caspase-8 | Play a role in execution of extrinsic apoptosis, inflammasome formation and inhibition of necroptosis. | |

| Caspase-9 | Increase ROS production and mitochondrial uncoupling in intrinsic pathway. | |

| Caspase-11 | Caspase-11 is homologous to Caspase-1. It activate Inflammasome, cleaves Gasdermin D during pyroptosis | |

| Caspase-12 | Also an inflammatory caspase that seems to mediate ER-stress-induced apoptosis. Exact function of Caspase-12 is poorly understood. | |

| Aspartic Proteases | ||

| Cathepsin D | Cathepsin D has been shown to mediate apoptosis in p53-dependent tumor suppression. Overexpression of Cathepsin D activates growth factors and promote angiogenesis. | [29,30] |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) | ||

| MMP-1 (Collagenase 1) | Can kill cells of CNS when activated through mechanism of S-nitrosylation. | [31,32] |

| MMP-2 (Gelatinase A) | Known to increase invasion and metastasis by degrading ECM components, promotes angiogenesis and tissue remodeling. May have a role in triggering neuronal apoptosis. | |

| MMP-3 (Stromelysin-1) | Involved in neuronal apoptosis. Increased expression of MMP-3 may have anti-apoptotic effect. | |

| MMP-7 (Matrilysin) | MMP-7 (Matrilysin) is able to release membrane-bound Fas Ligand (FasL), released FasL induces apoptosis of neighboring cells. | |

| MMP-9 (Gelatinase B) | Involved in degradation of ECM proteins (Laminins, fibronectin, vitronectin) to induce apoptosis in developing cerebellum and retinal ganglion cells. | |

| MMP-11 (Stromelysin 3) | Increases apoptosis during tissue remodelling and development or may inhibit apoptosis of cancer cells in animal models, promote tumor generation and metastasis. | |

| (A) | |||||

| Protease | Gene | Locus | Disease | Function | Ref. |

| Glycosylasparaginase | AGA | 4q34 | Aspartylglucosaminuria | Loss | [150] |

| Acid ceramidase | ASAH1 | 8p22 | Farber lipogranulomatosis | Loss | [151] |

| Aspartoacylase (np) | ASPA | 17p13 | Canavan disease | Loss | [152] |

| Proprotein convertase 9 | PCSK9 | 1p32 | Hyperlipoproteinemia type III | (Gain) | [153] |

| Lysosomal carboxypeptidase A | PPGB | 20q13 | Galactosialidosis | Loss | [154] |

| Enteropeptidase | PRSS7 | 21q21 | Enteropeptidase deficiency | Loss | [155] |

| Dihydropyrimidinase (np) | DPYS | 8q22 | Dihydropyrimidinase deficiency | Loss | [156] |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 | GGT1 | 22q11 | Gamma-glutamyltransferase deficiency | Loss | [157] |

| Prolidase (peptidase D) | PEPD | 19q13 | Prolidase deficiency | Loss | [158] |

| (B) | |||||

| Protease | Disorder | Acquired Mechanism | Key Feature | Ref. | |

| Neutrophil elastase (regulated by AAT) | α1-Antitrypsin functional deficit | Reduced inhibitor activity → protease overactivity | Emphysema, liver dysfunction | [159] | |

| C1 esterase inhibitor | Acquired C1-INH deficiency | Autoimmune or malignant consumption/inhibition | Recurrent angioedema (non-hereditary) | [160] | |

| Plasmin inhibitor (serine protease inhibitor) | α2-Antiplasmin deficiency | Deficiency from systemic disease or amyloid | Bleeding due to excess fibrinolysis | [161] | |

| Trypsin, chymotrypsin, elastase | Pancreatic protease deficiency | Pancreas damage or atrophy | Protein malabsorption, diarrhea, weight loss | [162] | |

| Various proteases: MMPs, cathepsins, calpain, caspase | Overactivity in the body | Upregulated in metabolic syndrome and inflammation | Tissue remodeling, insulin resistance, CV disease | [163,164] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ansari, A.; Ranjan, K.; Kumar, A.; Pathak, C. Molecular Perspective on Proteases: Regulation of Programmed Cell Death Signaling, Inflammation and Pathological Outcomes. J. Mol. Pathol. 2025, 6, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040032

Ansari A, Ranjan K, Kumar A, Pathak C. Molecular Perspective on Proteases: Regulation of Programmed Cell Death Signaling, Inflammation and Pathological Outcomes. Journal of Molecular Pathology. 2025; 6(4):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040032

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnsari, Aafreen, Kishu Ranjan, Ashish Kumar, and Chandramani Pathak. 2025. "Molecular Perspective on Proteases: Regulation of Programmed Cell Death Signaling, Inflammation and Pathological Outcomes" Journal of Molecular Pathology 6, no. 4: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040032

APA StyleAnsari, A., Ranjan, K., Kumar, A., & Pathak, C. (2025). Molecular Perspective on Proteases: Regulation of Programmed Cell Death Signaling, Inflammation and Pathological Outcomes. Journal of Molecular Pathology, 6(4), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040032