Abstract

What are the working conditions of freelancers in national media organizations? To answer this question, this study investigates the working conditions of freelance journalists in the Emirati media ecosystem. It focuses on the labor situation of freelancers in the national media organizations while exploring issues such as motivations for freelancing, their routines, contractual elements and income, professional challenges, and future opportunities. Self-determination theory (SDT) is used to analyze four dimensions of global freelance journalism. Additionally, SDT interprets the motivations of freelancers for adopting this profession, which are closely linked to their work conditions, the challenges they face, and their choices regarding self-determination in relation to future desires, opportunities, or the realities they must confront. The study uses semi-structured interviews with 15 journalists working in the U.A.E. and applies a thematic analysis to this data. The paper finds that comparatively, freelancers’ working conditions in the U.A.E. are as precarious as those of their Western peers, especially in contracts held with the national media organizations. The overall results also highlight other challenges encountered by freelancers in this profession. Finally, the paper offers a set of recommendations to enhance freelancing work conditions within the U.A.E.

1. Background and Aim

Journalism freelancing is now common in the news media industry (Rasciute, 2017), given the changing media landscape and deteriorating status of the journalistic labor markets (Zion et al., 2024). Increasingly, news organizations rely on freelancers to produce the news (Brems et al., 2017) as a way to reduce costs and maximize profit margins in the face of growing competition and news audience fragmentation (Tahir et al., 2024; Purovaara, 2022; Hanitzsch et al., 2020). Meanwhile, demand for current affairs news coverage continues over time (Dodd et al., 2019).

As market conditions decline, freelancing has become the livelihood for many journalists across the globe (Fahmy et al., 2022), while the number of freelancers continues to grow over the years (Cohen, 2019). Langit and Aloria (2022) estimate that there are 1.2 billion freelancers worldwide. Although exact numbers are not available for the U.A.E., an InternsME survey reveals a growing trend toward a more contingent workforce. In this sense, contract workers and freelancers are becoming more popular for businesses, with 27% aiming to expand their usage in the future and 42.2% of non-GCC nations in the Middle East wanting to expand their usage.

Freelancing in news reporting has received attention from scholars (Purovaara, 2022). These researchers have looked at the circumstances that force individuals to start freelancing under precarious conditions (Patrick & Elks, 2015), which have translated into working contracts that, in some cases, are truly draconian. In this sense, most studies indicate that, far from the Hollywood-romanticized image or the managerial aspiration of ‘freedom under the portfolio workforce’ (now often referred to as ‘nomads’), the condition of freelancing is instead characterized by professional insecurity and precarious working conditions (Worth & Karaagac, 2022). Today, many freelancers lack the basic legal and social protection that permanent, stable jobs offer (Oleshko & Mukhina, 2022), while the prospects and future careers are volatile and vulnerable to any external and internal changes.

Exploring freelance journalism and its precarious working conditions in the U.A.E. is still a relatively new area of research. Therefore, it calls for a national investigation across the nation. Nevertheless, it reflects what we are—aware of precarious work environments worldwide (Mellor, 2025). Freelancers encounter similar precarious working conditions across the world, including employment uncertainty, low-paying jobs, and labor precariousness, according to the literature (Bonini & Gandini, 2016; Himma-Kadakas & Mõttus, 2021; Patrick & Elks, 2015; Rita et al., 2021; Tahir et al., 2024; Clark, 2016). The growing number of freelance employees annually makes freelance work a global phenomenon, and the U.A.E. is no exception to this trend. The Emirati government is continually creating opportunities for independents, since the networks of these entities are increasing both domestically and globally (Dzamtoska Zdravkovska et al., 2024). It seems that freelance journalism in the U.A.E. reflects the global trend of job uncertainty. This demonstrates autonomy constraints where autonomy and competence are undermined by financial instability and low payment. Nevertheless, government reforms and networks for freelancers are promising movements offering emerging opportunities that may partially enhance autonomy and relatedness, despite continuous precarity.

Our initial thesis is that, broadly speaking, journalists working under freelancing conditions in the U.A.E. operate under similar conditions and challenges to those working in other parts of the world. Perhaps even more so, as visas and residence for non-nationals in these nations are contingent on obtaining a consistent source of income and job contracts or creating an individual firm in one of the free zones that generates enough income to legally remain in that country (Mellor, 2025).

To assess this initial thesis, this study investigated freelance journalism in the Emirati media ecosystem, focusing on freelancing working conditions. The study was conducted between 2023 and 2024. Our piece is based on 15 semi-structured interviews, which were carried out in Arabic, the native language of the participants, except for one that was carried out in English. The interviews were transcribed and translated into English. To this body of data, we applied a thematic analysis. The two main aspects that have been explored with this data set are the participants’ working conditions and the professional challenges they encounter.

2. About Freelancing

Most of the literature around freelance journalism covers, broadly speaking, four dimensions. These include aspects relating to the economic conditions of freelance journalism, news cultures and practices, and the laws and regulations of freelance journalism. In the case of this study, we shall interpret each dimension through the lens of self-determination theory (SDT), which is a theoretical framework that has been used in various fields and is applicable in different social situations, including interactive media and workplaces (Martela, 2020).

2.1. Theoretical Background

Self-determination theory (SDT) by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan is a psychological framework. It focuses on behavior as a consequence of the conscious or unconscious motivations that organize it, which often take the shape of wants, anxieties, reflective values, and goals that lead to human motivation, development, and well-being (Martela, 2020). It includes both extrinsic and intrinsic drives. But it emphasizes the role of intrinsic motivation due to its necessity for cognitive and social growth (Deci & Ryan, 2000). As a result, it examines how the social–contextual circumstances and environmental factors influence intrinsic motivation, self-regulation, and well-being (Martela, 2020).

Additionally, SDT can be applied to freelance journalism. Self-determination means the ability to determine behavior and mindset based on intrinsic or extrinsic motivations, leading to making one’s own choices and controlling one’s own life. Freelancers are individuals making decisions based on motivational influences. The three intrinsic needs that shape them are autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are generally universal (i.e., apply across individuals and situations). First, autonomy refers to an individual’s ability to choose their own behaviors and actions. Therefore, freelance journalists usually have autonomy in choosing their projects and schedules. When individuals have feelings of controlling their choices, they are more likely to feel motivated, persist in pursuing their goals, and feel satisfied with their efforts. Second, competence is the process of learning new skills and becoming an expert at them. When freelancers work on a variety of projects, they feel capable, which makes them more intrinsically motivated. Third, relatedness refers to belonging to a broader community and connection with others, such as colleagues or peers. These three needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness), if satisfied, allow optimal function and growth, because they are essential for individual psychological health and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Additionally, fulfilling these three needs increases intrinsic motivation and leads to freelancers showing job satisfaction and sustained engagement despite uncertain working conditions. However, people willingly participate in activities and behaviors that they do not find interesting or enjoyable because they are influenced by external motivators (Morris et al., 2022).

Freelance interviewees have self-determination to change their destiny based on their developed experiences and encountering the precariousness of working conditions.

Thus, we believe this particular theory provides a grounded model for exploring the issues surrounding freelance journalism and analyzing freelancing as a professional activity in the media ecosystem of the U.A.E. via the suggested four key dimensions in this study. Furthermore, SDT is applicable to interpreting the freelancers’ motivations for adopting this profession and explaining their work conditions, which are intertwined with the professional challenges that confront them, since SDT clarifies human needs that affect their satisfaction.

2.2. Economic Conditions of Freelance Journalism

Overall, the political economy in which freelance journalism exists has deteriorated over the past decades. According to research, the global economic crisis has resulted in an increase in job fragmentation, precariousness, and low-paying jobs (Bonini & Gandini, 2016). This has had a significant impact on media organizations and journalists’ jobs (Hanitzsch et al., 2020), leading to transitioning from permanent positions to temporary or freelance arrangements (Biernacka-Ligieza, 2013).

Some voices have suggested that freelancers are more prevalent in highly developed media markets. (Himma-Kadakas & Mõttus, 2021). However, these assumptions could be difficult to substantiate. In reality, an important challenge for scholars looking at this issue is determining the size of this labor force under freelance contracts both in the West and the Global South (Worth & Karaagac, 2022). This is aggravated by the lack of government statistics on freelancing around the world (Langit & Aloria, 2022).

We do know, for example, that by 2015, the United Arab Emirates was the fifth-largest customer of freelance services on the US-based Upwork (formerly Elance-oDesk), one of the largest freelancing platforms in the world (Cooper & Davies, 1982).

The literature on this subject also points out that freelance journalism may undermine the mental and physical well-being of journalists (Tahir et al., 2024). This is due to the anxiety created by the uncertainty and contractual disparities of those living from one pay cheque to the next, which is often unguaranteed (Langit & Aloria, 2022). In fact, both in the United States and the U.A.E., many freelancers lack health insurance, which also puts them at risk since they may perform dangerous tasks and may not be able to pay the high expense of treatment (Clark, 2016). When COVID-19 hit, these conditions were only aggravated (Svetlana, 2022), although evidence suggests that the pandemic boosted the growth of freelancing (General, 2022). In this sense, SDT suggests that finances and income distribution within a society have a significant influence on the quality of individuals’ lives and overall well-being (Martela, 2020).

2.3. News Cultures in Freelancing

Some voices have argued that when people refer to ‘freelancers’ in journalism, they actually mean ‘unemployed’ (Rasciute, 2017). Whether this commentary reflects facts or is cynicism, the fact remains that the collapse of large segments of the traditional media industry has meant that working as a freelancer is not really an option for many who are out of work (Cohen et al., 2019). However, this does not diminish the fact that freelancing presents a chance to create news stories firmly grounded in journalistic principles (Tahir et al., 2024). This study defined freelancers as follows:

Journalists who are freelancers can be conceptualized as professional practitioners who utilize their expertise and reputation in the news media and related fields of professional communication to work independently on their chosen projects, concurrently with multiple firms, according to their lifestyle convenience. The normative aspiration for these professionals is that their work should be free of any forms of editorial dependency beyond the basic requirements on newsworthiness, free of economic control from corporate advertisers, or under the supervision of the newsroom besides complying with the basic standards set in the stylebook. The normative expectation is, therefore, that freelancers should be able to display a greater degree of professional autonomy as they offer their pitches and final work to the commissioning editors and producers.

The literature also indicates that there are various types of freelancers, including part-time, contract, temporary, casual, and occasionally underpaid positions (Deuze & Witschge, 2018), as well as entrepreneurial employment (Rasciute, 2017). Scholars have also indicated that freelancers typically work on various short-term tasks for various firms at a given time (Purovaara, 2022).

Many individuals combine a full-time job with freelancing to supplement their income (Tahir et al., 2024). Nevertheless, all are examples of precarious employment. In relation to this, it is important to bring into the analysis that SDT suggests that regardless of the work type, it is a source of income and its ability to help individuals meet basic living standards that provides a feeling of fulfillment, self-realization, and happiness for the individuals (Martela, 2020).

2.4. Practices of Freelance Journalism

To be sure, several studies have emphasized that freelance journalism includes, in most cases, precarious working conditions and weak contractual conditions (Rita et al., 2021; Patrick & Elks, 2015; Norbäck, 2022). This, according to some authors, often translates into abuse and exploitation of the freelancers by those who hire them (Massey & Elmore, 2018). Regarding this, some authors have argued for conducting further studies on how freelancers might be safeguarded against abuse (Purovaara, 2022).

Not surprisingly, freelancers commonly report lower levels of satisfaction with their lives and dissatisfaction with their working arrangements (Cohen et al., 2019). This precarity reflects the lack of a robust legislative framework that identifies freelancers, protects them, improves their abilities, underpins their labor rights, and enhances the tools to enforce these rights (Langit & Aloria, 2022). The literature characterizes freelance journalism as being constrained autonomy, which is marked by weak contracts and exploitation. Competence needs are undermined by lack of self-development and rare recognition. Relatedness needs are also undermined by a shortage of organizational backup, which weakens belonging. Overall, unfulfillmened needs explain freelancers’ lower job satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

For many freelancers undertaking activities such as investigative reporting or coverage of conflict, matters are becoming more risky (Tahir et al., 2024). In some countries, freelancers might even encounter violence (Arnoldo González & Hugo Reyna, 2019) and risks associated with the topics they cover, all without the necessary organizational support or backup. In fact, a significant number of media outlets worldwide fail to provide adequate or any kind of protection for those working in geographical areas where they are exposed to risk and greater dangers. Therefore, many freelance journalists tend to work without any organizational protection or safety net (Rita et al., 2021). The opposite is true for those who work for larger media organizations (Clark, 2016). In this context, working without organizational protection mirrors autonomy constraints and structural insecurity and explicitly indicates that autonomy and relatedness needs are unfulfilled, as freelancers lack backup, support, and a sense of organizational belonging, which undermines motivation and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

2.5. The Laws and Regulations

Scholars have indicated that freelancing contractual and working conditions vary among nations due to factors such as lack of legislative protection, weak regulation, absence or prohibition of trade unions, unequal sets of benefits, and a broader lack of professional recognition and status (Burke & Cowling, 2015; Khan et al., 2022; Langit & Aloria, 2022; Mayo-Cubero, 2022; Worth & Karaagac, 2022).

In contrast, many efforts have been made to improve freelancers’ working conditions (General, 2022; Langit & Aloria, 2022). The Russian government has recently acknowledged the presence of freelancers by including the word ‘self-employed’ in the legal system (Oleshko & Mukhina, 2022). Freelancing has no negative personal, professional, or financial effects on employees in Montenegro. In September 2020, the state took the first steps toward freelancing regulation by passing legislation on research and innovation, which recognized freelancers working in innovation for both domestic and international enterprises. Additionally, income from self-employment is not taxed (Svetlana, 2022). In Europe, freelancers have effective unions that advocate for their rights and working conditions (Oleshko & Mukhina, 2022). Denmark’s Union of Journalists stands out in Europe for its enormous membership, which exceeds 18,000 members. The union has successfully brokered a collective agreement for freelancers, ensuring parity in rights and protecting them from financial instability. This alliance guarantees equitable labor conditions within the media industry (Tarlach, 2020). Noura Al Kaabi, the former Minister of Culture and Knowledge Development in the United Arab Emirates, has suggested that government assistance for freelancers could be beneficial (Grinstead, 2021). This interprets the relatedness element in accordance with self-determination theory (SDT). It is concerned with feeling socially linked and refers to belonging to organizations larger than oneself, which increases intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Only when professionals are independent and legally protected can they function effectively (Waisbord, 2013). The U.A.E. issued cabinet resolution No. 1 of 2022 on the implementation of federal decree-law No. 33 of 2021 regarding the regulation of labor relations. According to Article 8, freelancing is a type of work arrangement that is independent and flexible. A natural person makes money by doing a job or providing a specialized service to people or businesses for a set amount of time (United Arab Emirates, 2022).

Unlike many Western contexts, where residency is typically unrelated to economic activity, the U.A.E. regulates freelance work differently. To work legally in the U.A.E., freelancers need to obtain a freelance license and a residency visa from a free zone or government authority. Freelancers work through free zones, such as twofour54, Dubai Media City, etc., each with specific approved activities, license fees, and annual renewals that uphold administrative oversight over who may work and on what terms (Mellor, 2025).

A 2000 study indicated that Dubai’s free zones have drawn in investors and freelancers from all over the world (Kargwell, 2012). Dubai’s Media City, Dubai Studio City, and twofour54 all provide legal licenses for freelancers to operate in free zones and supply services to registered enterprises. For an initial expenditure of AED 20,000, the Dubai Freelancer’s Permit permits media workers to operate freely under their name (Rowland-Jones, 2013). SDT asserts that individuals accept laws and regulations that align with their psychological needs, leading to increased voluntary compliance. Furthermore, increased rights and liberties bring with them a variety of personal and community advantages (Martela, 2020).

2.6. Gaps and Knowledge

Although the literature highlights different aspects of freelance journalism globally, it emphasizes certain gaps. The literature points out that most academic studies have concentrated on their Western counterparts (Rasciute, 2017). Furthermore, these works ignore the role of freelancers working in other parts of the world and under different political conditions and media systems, and they are excluded from research samples (Massey & Elmore, 2018; Tahir et al., 2024; Ladendorf, 2013; Rasciute, 2017). Additionally, a new study emphasizes the necessity of an investigation into the challenges faced by freelancers to advance their profession (Norbäck, 2022) and how to protect them against abuse (Purovaara, 2022). One important gap is in relation to our understanding of journalism freelancing conditions and practices in the Middle East and North Africa. This gap calls for research in this field and additional efforts in understanding how particular contexts in the Global South play a role in shaping conditions and defining working practices.

According to the above facts, there is a lack of academic research regarding freelance journalism and the freelancing profession in the national media of the U.A.E. Therefore, the gaps that must be addressed are to conduct a study on freelance journalism in non-Western countries, such as the U.A.E., by including freelancers in research samples, to reveal the challenges they face and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of freelance journalism in national media organizations. Thus, these gaps in the literature provide the motivation and significance for this research investigation to fill the knowledge gaps of the literature on this topic.

Therefore, this study fills certain gaps in the literature by interviewing 15 subjects, including 3 accountable interviewees and 12 freelancers who practice freelancing nationally. This study investigated the working conditions and challenges faced by freelance interviewees in the U.A.E., an important part of the MENA region, which is considered unique within a rapidly changing media system. In addition, this study contributes significant suggestions to enhance freelancers’ working conditions in the Emirati media environment.

Within this context, the main research question is as follows: What are the working conditions of freelancers with national media organizations, and how does context influence their contractual arrangements? A related issue arising from this is how the freelancers’ working conditions can be improved.

3. Methodology

This study used in-depth, semi-structured interviews and applied a thematic analysis to the data generated by them. This form of qualitative research is critical for understanding the texture and meaning of experiences. The combination of interviews and thematic analysis provides both analytical and interpretive perspectives, enabling a holistic exploration of the phenomenon under investigation (Linström & Marais, 2012).

The study uses qualitative research approaches to describe complicated social realities from the viewpoint of a participant (Langit & Aloria, 2022), aiming to examine the participants’ working conditions and challenges. We drew from previous studies that used similar approaches, conducting semi-structured interviews with nine Australian freelance journalists and three editors to chronicle the real-life experiences of Australian freelance journalists (Tahir et al., 2024). Another study, similarly to research undertaken via semi-structured interviews, took place with seven editors from lifestyle magazines, newspapers, radio news programs, and commercial television news to present an overview of the freelance journalism sector in Estonia (Himma-Kadakas & Mõttus, 2021).

SDT, with its components of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, shaped the study design and the interview guide. The research instruments—semi-structured interview questions—were intentionally designed to investigate experiences of choice (autonomy), skill development or efficacy (competence), and social connection (relatedness). An example question related to autonomy is as follows: What are the reasons and motivations for working as a freelancer? Autonomy refers to an individual’s ability to choose their behaviors and actions. Therefore, freelance journalists usually have autonomy in choosing their projects and schedules. When individuals have feelings of controlling their choices, they are more likely to feel motivated, persist in pursuing their goals, and feel satisfied with their efforts. An example question related to competence is as follows: Do you feel that the skills you use in your profession have changed/evolved? Competence is the process of learning new skills and becoming an expert at them. When freelancers work on various projects, they feel capable, which makes them more intrinsically motivated. Some example questions related to relatedness are as follows: How would you describe the relationship between you as a freelancer or freelance journalist and the editor or other accountable individuals? Do you communicate with other freelancers? What are the topics that bring you together? Relatedness refers to belonging and connection with others, such as colleagues or peers.

This study focuses on freelance journalism within national media organizations. To provide exploratory qualitative data on the working conditions of freelancers in the national media industry, we contacted the Abu Dhabi Media Network and the U.A.E. Journalists Association to provide us with a list of freelancers who practice the profession with them, since they both engage with freelancers and maintain professional networks within or outside the U.A.E. media sector. Therefore, we selected the sample from a list provided by either the Abu Dhabi Media Network or the U.A.E. Journalists Association. This list contains freelancers who practice freelancing with both media organizations. We only included freelancers who work with national media organizations. And we discovered through the interviews that some of them also practice freelancing simultaneously in the private sector through PR firms. Therefore, this study used in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 15 subjects as a purposeful sample.

The research sample was selected based on the participants’ work or freelance work with the national media organizations (TV and newspapers) that represent the research population, which includes four parties, such as the Al-Ittihad newspaper and Abu Dhabi TV newsroom, both of which fall under the Abu Dhabi Media Network. Additionally, the Al Bayan newspaper and Dubai TV newsroom are both part of Dubai Media. It is important to mention that the Abu Dhabi Media Network and Dubai Media are two key national media organizations in the U.A.E. Additionally, the 15 subjects were chosen based on two categories, including 3 accountable interviewees in the national media organizations who work with freelancers and 12 freelance interviewees who freelance with the national media organizations in 2023/2024.

The sample selection was stratified based on age, occupation, gender, length of the freelancing profession, and areas of professional specialization to broaden perspectives, experiences, and opinions. After 10 interviews, we found a level of saturation since no new themes were emerging due to similar answers. In fact, the 15 interviews resulted in substantial data that answered the research questions and enriched the study without the need for more interviews.

However, we do not claim universality or representativeness in our conclusions, as is the case with any qualitative data generated by a qualitative interview study using reflexive thematic analysis. Instead, we aim to provide a systematic and insightful critical understanding of the freelancers’ working conditions and the challenges they encounter in the national media organizations.

We contacted 24 participants via cell phone. It is important to mention the significant limitation that the number of respondent female freelance journalists in this study is less than the number of male freelancers. This mirrors a fact mentioned in the literature that freelance journalism is a profession dominated by men (Guo & Fang, 2023). This study conducted interviews with only two female participants, while three female freelance journalists declined to be interviewed because they feared losing opportunities in the freelancing profession, as they expressed. Additionally, two male freelance photojournalists declined to participate in interviews because they were on outboard missions, and three male freelance journalists refused to participate without mentioning the reason. Furthermore, a freelance journalist promised to continue the interview after he had completed half of it, but he did not answer the author’s follow-up calls. As a result, the number of female freelancers is lower than that of male freelancers, which requires further study in the future.

Following ethical standards drawn from the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 (Schmidt et al., 2020) and given the sensitivity of the topics approached, we made the participants’ protection paramount in our study. The study also complied with the ethical norms and standards set by the Ethical Research Committee of the University of Sharjah, which include informed consent to participate, protection of participants’ privacy through data confidentiality and anonymity, and allowing the subjects to withdraw at any time. The university’s ethical committee granted permission to conduct this research according to reference number REC-24-01-27-02-PG on the date 18 February 2024. Thus, interviews were performed with the explicit permission of the participants.

Faulkner and Atkinson (2023) mentioned that considering ethical concerns in research procedures leads to a more rigorous study. Consequentialist ethics, as criteria for the assessment of moral decisions in research, reflect the significance of a research project’s outcomes. They emphasize that actions are to be ethical if they contribute to social good Therefore, all the transcriptions of the interviews were anonymized. As a result, each interviewee has a code number (PM1-PM15), where (P) denotes the participant, (M or F) denotes the gender, and the serial number is for each interviewee. Furthermore, to protect participants’ confidentiality, identifying details were generalized, and we used shortened quotes and removed contextual clues inside quotes. Additionally, the recordings in their original language were securely stored and controlled, with access by the author only.

According to the approved Informed Consent Form by the Ethical Research Committee of the University of Sharjah, the interview record may only be shared with the supervisor, and only selected interview content and excerpts may be included in the paper. The research paper will use anonymized interview data, which may also be used for PhD dissertation presentations and/or publication. Therefore, transcripts from the semi-structured interviews cannot be shared due to confidentiality and potential risk to participants.

We conducted all the interviews in the U.A.E. through phone calls. Each interview lasted approximately one hour. The interviews were conducted in Arabic, the native language of the participants, except for one that was carried out in English. Participants’ responses were recorded, transcribed, and then translated into English to facilitate analysis. To guarantee the translation quality for semi-structured interviews, the main author conducted the initial translation. And to confirm the translation’s reliability and quality, the thesis supervisor, as an independent translator, checked it for accuracy and consistency. Furthermore, we conducted collaborative revision to ensure that the translation retains the original meaning, tone, and cultural context of the data collected in the interviews. We endeavored to maintain authenticity in translating data in general as well as relevant quotations. The study documented the participants’ actual experiences, investigated their motivations, exposed the challenges they face, and identified their future opportunities.

The study used thematic analysis to examine the collected data, which resulted in a number of themed clusters. Themes are essential to qualitative data interpretation. Gaining familiarity with the data, constructing subcategories, producing, evaluating, and labeling themes, and finding exemplars are the six processes of thematic analysis (Scharp & Sanders, 2019). Tahir et al.’s (2024) study employed thematic analysis to examine twelve interviews (Tahir et al., 2024). The main author (as the single coder) used the single-coder reflexive approach of thematic analysis and analyzed the qualitative data by identifying themes or patterns under the supervision of the thesis supervisor. One positive note regarding utilizing a reflexive approach is that it is a useful and flexible method for qualitative research since it is characterized by maintaining control over the interpretation and data analyzed (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Themes were generated based on analytic memos to support analytical clarity. Analytic memos and reflexive notes were systematically documented throughout the coding and theme development processes to capture analytical judgments and emerging trends. The material was structured into tabular charts to enable the comparison of interviewees’ examples and to discern any discrepancies or similarities. Quotation marks were employed to maintain the contextual integrity of the expressed concept. The transcripts underwent data coding analysis, whereby codes were categorized. This focuses on the freelancers’ working conditions, including five clusters themed around motivations for the freelancing profession, the routine of freelance work, payment and income, freelancing challenges, and the interviewees’ solutions and future opportunities. Supervision functioned as a credibility assessment through regular follow-up to discuss the developing codes and themes, during which analytic interpretations were critically examined and refined. These regular discussions supported reflexivity and analytic rigor.

We consider our position in relation to the collected data. This helps us to be neutral toward the interpretation process and ensures that findings are reliant on the data, not on personal assumptions, to avoid any biases. Additionally, we used member checking and note-taking to ensure accuracy and reach a shared understanding of the results, which were appreciated by interviewees. Therefore, the results accurately reflect their experiences and perspectives.

Qualitative Rigor and Trustworthiness

The combination of two varied approaches and data sources demonstrates the credibility of this study. The study used in-depth semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis as two qualitative methods to gain insight into freelance journalism in the national media system. Confirmability is vital for determining the trustworthiness of qualitative research (Lim, 2025). The precarious working conditions of 12 freelance interviewees, validated by 3 accountable interviewees, serve as multiple data sources and reflect similar uncertain working conditions faced by freelancers globally, as indicated by a review of the literature (Patrick & Elks, 2015; Rita et al., 2021; Tahir et al., 2024; Clark, 2016). The experiences and perspectives of the interviewees, supported by their quotations, form the basis of this study’s findings, interpretations, and conclusions. Thus, this evidence strengthens the study’s conclusions and maintains a critical and impartial perspective to ensure that the study’s findings are sound.

4. Findings and Discussion

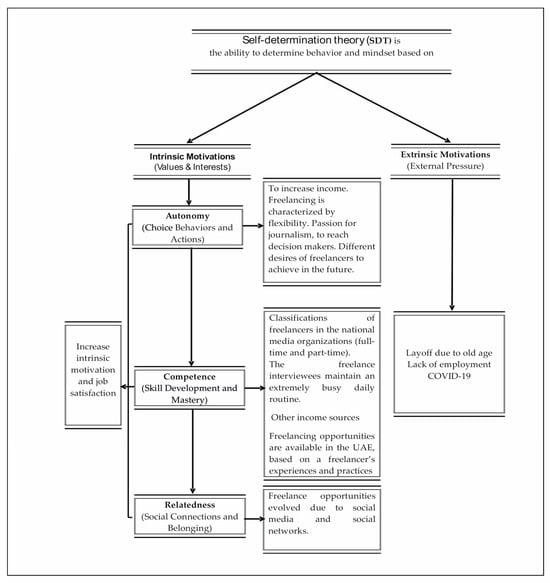

We developed five thematic clusters using an SDT-inspired model. This is because we consider them indicative of the freelancers’ working conditions with the national media organizations. Figure 1 demonstrates a theoretical model showing how SDT maps onto the study’s empirical findings.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model showing how SDT maps onto the study’s empirical findings. Source: authors.

The study analyzes 15 interviewees’ experiences and points of view, and their featured quotations contributed significantly to the study. The interviewees’ statements reflect their lived experience related to the freelancing profession. It is significant to note that the perspectives of the accountable individuals were used to compare with those of freelancers, allowing for comparison of the main themes. We applied self-determination theory (SDT) in our analysis during the interpretation process. SDT shaped the data collection and analysis. The empirical patterns nuanced the SDT. Additionally, we explain how data were coded as autonomy, competence, or relatedness in Table 1. Table 1 presents themed clusters, each accompanied by a concise definition, summarizes the study findings from the thematic analysis, and outlines the connection to the SDT needs for each theme, including representative quotes. Additionally, a brief interpretive warrant (one per SDT need) indicates need thwarting or need satisfaction.

Table 1.

Study findings from the thematic analysis. Source: authors.

Our analysis starts with the motivations for the freelancing profession, which differ according to each individual case and are intertwined with participants’ real-life circumstances. According to SDT, individual behavior is based on intrinsic or extrinsic motivations, leading to making one’s own choices and controlling one’s own life. The three psychological needs that are related to intrinsic motivation are effective functioning, high-quality engagement, and psychological well-being. It is important to distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Intrinsic motivation is internal and driven by values and interests. Therefore, an individual starts an activity because it is enjoyable and satisfying to do so. In contrast, extrinsic motivation is controlled by external pressures. The individual engages in an activity to achieve an external goal (Morris et al., 2022).

Five of the freelance interviewees mentioned that they started freelancing due to forced circumstances, such as a layoff from work due to old age, as pointed out by PM2, who said, “I began freelancing due to old age. All of the entities refuse to hire anyone above the age of sixty, even if they have extensive expertise.” The irony is that their experience, which should make them more desirable, is actually a disadvantage in the workplace, according to them. The difficulty of securing formal employment is another reason to practice freelancing; there is intense competition for jobs, and as both PM12 and PM2 noted, there is significant rivalry for a few jobs. Therefore, the available solution is to practice as a freelancer, as PM11 noted. Additionally, deteriorating working conditions and job losses drove others into freelancing. This was the case for PM4, who noted that “due to COVID-19, I operate as a freelance entrepreneur. I have no job opportunities; the period following the coronavirus pandemic has led to extreme stagnation across all industries. The effects of the coronavirus problem persisted with me, possibly until now.” We can interpret that these five freelance interviewees were driven to freelancing because of extrinsic motivations that reflect autonomy constraints and external control. These external pressures suggest that the need for autonomy is being thwarted rather than satisfied. Therefore, they engage in freelancing because they are influenced by external motivators. Simultaneously, they strive to achieve an external goal, namely, to meet their financial obligations. On the other hand, despite constraints or their uncertain circumstances, they show the ability to work and interact effectively with the environment, which refers to competence, the second psychological need (Morris et al., 2022).

In contrast, some freelance interviewees seek to increase their income, as pointed out by PM3, who said, “I intend to increase my income by freelancing. I accept any freelance opportunities.” PF13 said, “In 2021, I began freelancing in multiple locations for practically all of the U.A.E.’s newspapers. I can make myself available for other jobs that pay higher.” The freedom and flexibility of freelancing motivate individuals, with freelance interviewees citing minimal employer restrictions and interference. In this sense, PM1 said, “I want to be my own boss.” PM2 underlined that “I practice freelancing from home.” And PM7 mentioned that “Freelancing helped me achieve a balance between my personal life, my family, and my hobbies.” PM6, the accountable interviewee, assured the flexibility of the work system for freelance photographers, as he pointed out that “all freelance photographers work according to a shift system that lasts 4 to 5 h a day, and they rarely work 7 h, which may occur once a year because the work system is very flexible.”

In this sense, freelance interviewees who are seeking to increase their income, which reflects extrinsic motivation, may internalize this motivation. The freedom, flexibility, minimal supervision, and work–life balance provide a strong foundation for autonomy. And the potential to handle multiple projects and schedules mirrors competence satisfaction. Balancing freelancing profession activities with family care and personal hobbies enhances relatedness and overall well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

In addition, the passion for journalism and aspirations to satisfy the creative aspect also seem to drive the other half of our research sample to practice freelancing, as PM10 said: “My passion for journalism. I used to read and correct the news articles in the newspaper. That developed into a desire to have a column.” PF9 began her freelancing career to express her opinions during the Arab Spring. Additionally, PM12 expressed his desire to participate in artistic projects, stating, “I need to participate in a beneficial good thing, such as a short movie that may win an award.” Practicing journalism and engaging in creative projects demonstrate autonomy support, which aligns with personal interests and choices. This is rooted in a genuine interest in an activity and based on the belief that the action aligns with one’s own values and objectives. Applying skills and developing expertise leads to the achievement of competency satisfaction. Contributing to meaningful projects and connecting with target audiences achieves relevant satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This increases intrinsic motivation (Maggino, 2023).

Indeed, searching for freelance opportunities has evolved over time due to social media, experience, and social networks. PF13 said, “There are recruitment agencies that scan my LinkedIn profile and book me for short-term projects.” Meanwhile, PM11 noted, “The freelancing industry is built largely on relationships, since people who know the freelancer’s abilities contact him and offer a part-time employment.” Therefore, they communicate with each other to delegate freelance opportunities in busy cases. PM3 said, “We help each other find freelance opportunities.” Finding freelancing opportunities through social media, personal experience, and professional networks demonstrates autonomy support by allowing individuals to control their career paths) (Deci & Ryan, 2000), assert that relatedness satisfaction arises from collaborating and receiving recognition within professional networks. Furthermore, relatedness is essential for belonging to and connecting with others. This enhances motivation and well-being. It satisfies autonomy and competence as well (Ryan & Deci, 2017). As a result, freelance interviewees communicate with each other, which increases their motivation and overall job satisfaction. This reflects what the literature mentioned: there is always support among unstable coworkers. This peer solidarity is primarily due to similar working circumstances. Collaboration is in their best interests since the majority of future work opportunities stem from personal connections that they have formed (Bonini & Gandini, 2016). This contradicts another fact mentioned in the literature about social and professional isolation encountered by freelancers (Patrick & Elks, 2015).

We can argue that freelancing can be a personal choice or a forced reality. In the personal choice case, it increases intrinsic motivation and leads to strong engagement with autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. Freelancing allows individuals to exercise choice and control, thereby promoting autonomy; it facilitates the use and mastery of skills, thereby enhancing competence; and it fosters connections and a sense of belonging, thereby fostering relatedness. In contrast, when freelancing becomes a forced reality, it may result in the neglect of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, which can lead to feelings of need thwarting, reduced motivation, and lower well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

4.1. The Routine of Freelance Work

The freelance interviewees practice freelancing for national TV newsrooms, national newspapers, and PR companies in the U.A.E. The study data reveals that freelancers in national media organizations can be classified into several categories, including freelance journalists, freelance photojournalists, freelance TV news producers, freelance social media reporters, and freelance entrepreneurs. This classification is not meant to be generalized but rather reflects what the study’s data analysis revealed. Therefore, their journalistic contributions differ according to their freelancing classifications and the place where they freelance.

The data derived from the interviews also indicates that there are two types of contract in the freelancing professions. This classification includes both full-time and part-time freelance contracts. A full-time freelancer’s daily routine is similar to that of an employee, with regular shifts in the office and a commitment to attend meetings where a discussion takes place regarding the required tasks. The shifts last for an average of 6 to 8 h a day, depending on work schedules, as PM11 and PM12 mentioned, respectively. “Despite working as a freelancer in the daily newscast, my daily routine is closer to a full-time job than a freelance profession.” “My daily routine as a freelance TV news producer begins in the morning with the editor-in-chief for an average of 8 h a day or more, depending on the nature of the work schedules or the events that take place in the news market.” While a part-time freelance contract is characterized by flexibility because it is not a full day’s work, freelancers practice freelancing part-time from home or attend for a few hours until they accomplish the required task, as PM2 reported. This is consistent with what the literature mentioned: journalism and news organizations collaborate with freelancers (Maillot, 2019) and part-time and non-fixed contract journalists (Guo & Fang, 2023). A full-time freelance contract represents an autonomy constraint since it limits choice and control over work. In addition, it contains a competence constraint because it may restrict opportunities to develop or use skills elsewhere and can reduce interaction with multiple networks, which leads to a relatedness constraint. In contrast, a part-time freelance contract enhances autonomy support, since it allows freelancers to choose multiple projects and negotiate income and terms. Furthermore, part-time freelance contracts help freelancers develop their skills in various settings, leading to competence satisfaction and the maintenance of broad professional relationships, which in turn fosters relatedness support (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

However, most of the interviewees instead claimed to have an extremely busy daily routine, as pointed out by PM3, who said, “My freelance work regimen depends on the deadline for submitting the required task.” They always pre-plan and follow the required topics and delivery times, as PF13 said: “My daily schedule depends on where the project or event is, and I always need to pre-plan.” Most of the interviewees underlined that they needed to keep up with local and international news on a daily basis, which requires a daily commitment to work. As PM10 said, “I have an hour to write an article every day after following the world news, whether it is published or not.” They read, attend seminars, and take training to always be ready, as PM4 said: “I attend the Emirates Journalists Association’s seminars and training courses.” Their selection is based on their exceptional abilities, as PF13 emphasized: “One of my strongest personal skills is my ability to create and perform tasks quickly.” Cell phones and e-mails are important to receive freelancing requests. Some monitor social media trends to determine their contributions; as PF9 says, “As a freelance journalist, I must keep up with the latest trends by checking social media every day.” Freelance journalists may experience autonomy support through discretion in selecting projects and scheduling work, reflecting SDT’s principle about individuals who can choose their behaviors and actions. They have feelings of controlling their choices; they are more likely to feel motivated, persist in pursuing their goals, and feel satisfied with their efforts (Ryan & Deci, 2017). However, at the same time, they may be facing autonomy constraints in the form of deadlines, workloads, and contractual requirements.

4.2. Payment and Income

Income can be discussed as an external condition that may support or undermine need satisfaction, since individuals expect to be rewarded for the service they provide in a way that represents a recognition of the value of their work. Despite this, freelancers’ payment and revenue are often regarded as personal and confidential information. However, the study sample disclosed it to improve freelancers’ working conditions and income, particularly in the future. Table 2 presents the income of freelance interviewees, in AED currency, alongside their compensation based on word count per article. However, it is important to note that the income figures and word-count-based compensation are not comparable.

Table 2.

Freelance interviewees’ income and word-count-based compensation figures. Source: authors.

Each freelance interviewee receives a different freelancing payment based on the media organization they freelance for and the nature of their assigned tasks. In general, the interviewees’ monthly income ranges from a minimum of AED 4000 to a maximum of AED 25,000 per month based on their annual contract. As pointed out by PM3 and PM11, respectively, “The maximum monthly limit was between AED 4000 and AED 5000.” “My revenue from freelancing is 25 thousand AED every month.”

This paper discovered that the freelancing payment differs from one freelancer to another in the same media organization. While both PM11 and PM12 work for the same news organization, one receives AED 25,000 per month while the other receives just 20,000 AED. Meanwhile, both PF9 and PM10 freelance at the same national newspaper. But they did not receive equal payment for an article. PM10 says, “I receive 367 to 551 AED for every article per week.” PF9 attributes this disparity to the social network that influences the payment; as she says, “Building both professional and social relationships that define the breadth of writing freedom and the space of published articles, both of which have an impact on payment.” Unequal payments within the same organization reflect constraints on autonomy due to limited control over income, as well as the influence of social networks on opportunities; in contrast, freelancers who leverage their skills and networks to achieve goals demonstrate competence and potential need satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Having said that, some of the freelance interviewees receive much lower incomes, which is why only the interviewees with no family responsibilities consider their income acceptable. As PM1 mentioned, “I make more than AED 5000 a month. It is acceptable.” In contrast, interviewees with families and dependents are looking forward to increasing their income. PM11 mentioned that “Given the rise in family and educational costs, my freelance income would not be sufficient in the following phase.”

Most freelance interviewees expressed concerns about diminishing returns in their freelance activities and attribute this to several reasons. First, they highlighted that a growing number of young, inexperienced freelancers are willing to accept lower pay, a point emphasized by PM3, who asserted that these young freelancers “lack expertise, in contrast to our professionalism.” Another reason given is that some institutions are more concerned about costs than quality. As PM3 said, “Since cost reduction is the main objective, not all parties are concerned with the outputs’ accuracy and quality.” COVID-19 and its aftermath also played a role in diminishing returns; PM4 explained, “I had no income for the past two years due to the COVID-19 circumstance.” This, consistent with the literature, highlights that freelancers have been among those most impacted by COVID-19 because employment has vanished (Svetlana, 2022). PM5 also mentioned that “Income varies according to seasons.” And large government institutions apply their tender system, which privileges companies rather than individual freelancers’ names, according to PM5. Also, many government agencies prefer to work with public relations firms in order to use freelancers, as pointed out by PM7, “The income is lower because PR firms share revenues with me.” Increased low-paid competition, cost-driven institutions, COVID-19-related income loss, seasonal work, tender systems, and sharing of freelancing income via PR firms reduce freelancers’ choice and control. This represents constraints on autonomy and competence, indicating that the needs for autonomy and competence are being thwarted rather than satisfied (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

The conditions, according to the freelance interviewees, vary depending on the nature and size of the organization that contracts the individuals. Hence, the freelancing experience differs from one entity to another. Simply put, large media organizations and private sector ones, as mentioned by PM5 and PM1, respectively, pay better. “Large organizations or governments pay more to freelancers” (PM5), and “private enterprises pay more for freelancers” (PM1).

There are two payment methods. First, the payment is based on a contract that is renewed annually. PM12 said, “The payment methods are monthly based on an annual contract.” The contract specifies the amount paid monthly for the freelancer’s total number of contributions, as PF9 mentioned: “I contributed a weekly article from 2019 to 2021. Then, between 2021 and today, I contributed an article every two weeks. I charge 735 AED for one article.” This mirrors how newsrooms pay for completed journalistic material under preset agreements (Himma-Kadakas & Mõttus, 2021).

PM11 mentioned that the contracts and terms also vary per institution and even among individuals working for the same organization. Regarding this, PM11 said, “The contract explicitly indicates that I am not a permanent employee of the company, and both parties can end it at any moment.” This mirrors what the literature mentions: freelancers face uncertain hiring conditions (Massey & Elmore, 2018) and work under precarious, sometimes draconian contracts (Patrick & Elks, 2015), which affect their income. We can say that this is true for many in our sample, and it is likely true for many others. Variable terminable contracts reflect autonomy constraints through externally imposed insecurity and explicitly indicate autonomy and relatedness need thwarting rather than need satisfaction, as freelancers lack stability, belonging, and control over continued employment (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

A few freelance interviewees with part-time freelance contracts mentioned that the party they freelance for allows them to accept external freelancing tasks as long as there is no conflict of interest with their current freelance contract and they negotiate the payment price, such as PM1, PM15, PM10, and PF9, who underlined that “I practice freelancing in multiple places, and I do not confront any objections because of that.” Allowing freelancers to accept external tasks and negotiate their pay reflects autonomy support, particularly in terms of choice and control. This indicates that people feel more motivated when they can make their own choices. This flexibility enables freelancers to diversify their income streams. However, time management and commitments are essential to ensure that they meet the expectations of all parties involved. Additionally, this indicates competence need satisfaction, as freelance interviewees demonstrate skills and effectiveness, which allow them to negotiate the payment price. This reflects their competence to work and interact effectively with the environment (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

In contrast, PM11 and PM12, who both freelance for the same media organization, cannot offer their services to a third party because their freelance contracts are full-time. PM12 stated, “The contract prohibits freelancing for another organization; otherwise, the contract is terminated.” Full-time freelance contracts that prohibit accepting external freelance tasks represent autonomy constraints, since they are externally imposed limits and explicitly indicate autonomy need thwarting rather than need satisfaction, as PM11 and PM12 lack choice and control over their labor decisions (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

A second type of payment happens with no written contract. It is often based on a verbal agreement for each contribution that the freelancer delivers. The freelance interviewees warned that nonwritten contracts may delay or prevent freelancers from being paid. PF13, who has personally experienced this, noted that “The lack of written contracts makes it harder to pursue payment claims. I had provided a lot of freelance work without financial payment. I tried to claim my payment, but no one responded.” Unpaid freelance work reflects an autonomy constraint and external control and explicitly indicates competence and fairness need thwarting under SDT, as the freelance interviewee’s efforts are neither rewarded nor acknowledged, undermining motivation and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

In addition, PM3 clarified that, in the absence of a signed contract, payment is determined by the number of words published, as words are only counted once the content is published.

“In cases when the work required is a translation, it is counted by words rather than the journalistic article or its theme. Some places pay dirham per word. Other places paid 75 fils. The current best deal is fifty fils, or half a dirham. Other topics that remain in Arabic include editing, rephrasing, or re-editing, which costs 350-250 AED. If there are several articles, the price will be reduced. In addition, if the topic requires editing, drafting, or linguistic evaluation, the price will rise slightly.”(PM3)

PM7 noted that the market pricing now is different; the business environment changed as a result of the epidemic. He said, “The word might range between one dirham and seventy-five fils.” There is convergence in prices based on the number of words.

On a positive note, the interviewees pointed out that when working for national media organizations, payment delays rarely happen. PM10 articulated that “my freelancing income is transferred without delay.” Also, PM15, who practices freelancing in another national TV newsroom, mentioned that he is paid regularly in the first week of the month. Regular payment reflects autonomy support through financial control and security and competence need satisfaction, since work is valued and reliably rewarded. Additionally, it indicates relatedness need satisfaction via trust and stable exchange with the work environment (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In contrast, freelancers who enter into verbal agreements often experience payment delays. This phenomenon is particularly true for those who freelance in the private sector, as reported by PM7. Verbal agreements and payment delays represent autonomy constraints and explicitly indicate competence and autonomy need thwarting, as freelancers lack control and recognition of their work (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

The interviewees explained that in many news organizations, paying freelancers is a priority due to life obligations. Therefore, the interviewees, who do not have contracts, negotiate the payment price. PF13 said, “I generally negotiate for the payment.”

The majority of freelance interviewees have no other income source. Therefore, having no alternative income reflects an autonomy constraint, including limited choice/control, and constitutes autonomy and security need thwarting rather than need satisfaction within SDT, reinforcing freelancers’ economic precarity (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In contrast, PF9 and PM10 have stable jobs in addition to their freelancing profession. PF9 said, “I have a main source of income because I work as an assistant professor.” In this sense, the freelancing profession serves as a supplement to their stable job, providing additional financial returns. Having a stable job represents autonomy support through greater choice and control, while freelancing as a supplement reflects competence need satisfaction, since the freelancers’ secure income base allows them to exercise skills voluntarily rather than under economic pressure. Furthermore, this refers to their competence; when PF9 and PM10 possess the necessary skills for success, they are more likely to take actions that help them achieve their goals (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

4.3. Freelancing Challenges

The majority of freelance interviewees mentioned that financial uncertainty is their most significant challenge, since it affects other life aspects. They cannot afford health insurance or a commercial license, and they do not have end-of-service benefits. PM7 stated, “For budgetary reasons, I have been without health insurance for three years. It’s expensive.” In return, PF13 noted that “My residency is through the twofour54 Free Zone, and I have a golden visa. My health insurance is on me.”

PM11 reiterated that “residency, commercial license, health insurance, and end-of-service are not available for the freelancer who cannot afford them, and these are considered key obstacles for me as a freelancer.” As PM4 mentioned, “These obstacles make me nervous and have an effect on my health.” In the same context, the accountable interviewees from the national media organizations noted the lack of health insurance for freelancers. PM8 said, “The freelancer’s health insurance and their residence are on them.” PM6 went further: “Freelancers have no rights or insurance. Their residence in the country depends on them or their families. Their contract is of a monthly nature, with the possibility of termination.” The financial uncertainty, lack of health insurance, and unstable residency mirror externally imposed limits, indicating autonomy and security need thwarting rather than satisfaction, according to SDT. This reflects freelancers’ precarious working conditions rather than supporting motivation or well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Overall, there is little doubt that these challenges affect the psychological and healthy state of the freelancers, which makes them a permanent issue of concern. This finding, which aligns with the literature, indicates that freelancers earn low wages (Clark, 2016). Therefore, they face continuous financial anxiety (Rita et al., 2021) due to underpayment (Rasciute, 2017), a lack of retirement benefits (Rita et al., 2021), and a lack of health insurance (Patrick & Elks, 2015). Low wages, lack of retirement benefits, and lack of health insurance exemplify how needs are being thwarted rather than satisfied (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Therefore, these obstacles impact the psychological state of freelancers, leading to their constant preoccupation with financial concerns. Therefore, they are in dire need of health insurance due to their precarious circumstances.

The freelance interviewees expressed their perceptions related to the regulatory side from their end; as PM7 said, “Government institutions did not update their internal regulations governing directly contracting with freelancers.” Additionally, the freelancers’ annual leave varies from one media organization to another, as PM12 and PM15 mentioned, respectively. “The annual leave is just two weeks, including both sick leave and annual leave.” “I don’t have a leave clause in the contract. For example, I coordinate a leave with the head of the center and the coordinator, who has the router.” Furthermore, freelance interviewees expressed concerns about the complicated electronic procedures and the associated high costs, which they consider challenging. As PM4 stated, “The challenges include the lengthy procedures, expensive license fees, financial charges for any procedure or transaction, and the time required to complete electronic transactions, such as the To Whom It May Concern certificate.” Rare sick leave, limited annual leave, and complicated electronic procedures involving high costs and lengthy processes exemplify how autonomy needs are being thwarted rather than satisfied (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

In addition, the freelance interviewees expressed other challenges that impact their incomes and their ability to produce high-quality work. These include the imposition of limits to the word count. In relation to this, PM10 pointed out that “I’m still not persuaded that 400–500 words in an article will cover all issue dimensions.” PF9 stated, “The word count of 400 is quite low for significant issues, making it difficult to cover such large topics.” PM3 clarified, “Sometimes there is a lack of consensus on viewpoints; in such situations, I withdraw.” The above scenario indicates that autonomy needs are thwarted rather than satisfied, as the individuals involved have no control over the article’s scope and lack the competence to align with others’ viewpoints due to existing obstacles. As a result, it will likely negatively impact intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

In addition, PM7 stated that “to cut costs, media firm owners have started using freelancers from abroad.” More recently, there has been growing concern, with a few freelance interviewees voicing anxieties about how many news organizations are replacing freelancers with artificial intelligence-driven content generation software, a move that PM7 believes will further exacerbate the precarious position of freelance journalists. Replacing freelancers with AI is a topic that needs future study. Freelance interviewees’ fears of AI and foreign freelancers replacing them due to cost-cutting are indicative of need thwarting rather than need satisfaction.

Freelance interviewees are driven to practice freelancing by autonomy constraints, which are external pressures, which are challenges they encounter in their working conditions or controlled extrinsic motivation and autonomy need thwarting. Therefore, when freelance interviewees internalize these external demands, they gain choice/control. Their behavior reflects autonomy support and partial need satisfaction, which helps explain their persistence, motivation, and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

4.4. Interviewees Solutions and Future Opportunities

In view of uncertainty and precarity, interviewees suggested proposals to improve their contractual and working conditions. On the regulation side, PM11 suggested “creating a framework to regulate freelancers.” PM7 added the recommendation of “issuing a law requiring media organizations to use freelancers in the same way they interact with any licensed company.”

Financially, the majority of freelance interviewees argued for a financial return that is far more predictable while “enhancing the working conditions for freelancers by increasing income” (PM2). A logical financial return, particularly in cases of continuity, is crucial for freelancers because it affects their stability and influences their extrinsic motivation. Adequate wage or fair income supports autonomy through financial security or freedom of choice and control. Fair pay or recognition of skill and effort enhances competence, and it can also support relatedness by fostering feelings of being valued and respected. As a result, income motivates human behavior. Financial instability undermines these needs, whereas financial stability fosters internalized extrinsic motivation, thereby enhancing stability and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Additionally, the interviewees recommend ways of securing residency rights, access to health insurance, and requiring compensation in case of undue termination of service, which are three significant requirements to improve the work environment from the freelance interviewees’ perspective. PM2 argued that access to residence rights and health insurance could translate into much better conditions for freelancers and a significant reduction in their precarity.

Professionally, a few freelance interviewees emphasized that media organizations must prioritize expertise and quality over cost. This, according to them, will certainly open many opportunities for freelancers and enhance the overall labor situation. Some of them went further to argue for an increased writing scope; as PM10 mentioned, “I suggest increasing the scope of freedom, which confers more credibility.” Additional freedom and professional autonomy to cover the story or event from all dimensions can enhance the work and outputs. Greater writing scope supports autonomy, which positively enhances freelancers’ intrinsic motivation and competence, leading to job satisfaction, especially when they practice choice and skill mastery (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

According to our study sample, freelancing opportunities continue to be available in the U.A.E. through freelance law (United Arab Emirates, 2022). However, the ability to access those opportunities is subject to external factors as well as the freelancer’s own potential to provide quality content. PM15 mentioned that “many media institutions and offices require freelance work.” PM2 added that “Freelancers currently have the option of working for a private enterprise or starting their own business.” However, each freelance interviewee has a different desire that reflects his or her experience in the field which he or she seeks to achieve in the future. This includes establishing a filming production company, creating a media company, or becoming a freelance entrepreneur in the future, as pointed out by PM1, who said, “I want to have a filming production company in the future.” PM2 said, “I wish to create a media company in the future.” Nevertheless, fulfilling these targets depends on creating working conditions that privilege experience, capabilities, and, to no lesser extent, access to investment capital to reach their future goals. Freelance interviewees’ future desires reflect autonomous, self-endorsed goals through autonomy; the need for skill development and mastery via competence; and relying on social and professional networks via relatedness. However, if these conditions vanish, goal achievement and need satisfaction are constrained (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

The freelance interviewees have varied experiences, which shape their future desires, as they decide their destiny based on personal experiences and preferences in the field. Their differences in personality result in making choices that reflect autonomy through self-directed decisions based on their values and interests. However, internal motivations and external pressures direct their behavior and impact how autonomy and overall need satisfaction are realized (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Freelance interviewees have self-determination to change their destiny based on their developed experiences and encountering the precariousness of working conditions. Based on self-determination theory, freelancing activity can be comprehended as a work context that both enables and constrains the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. The empirical findings indicate that freelancers’ motivations, routines, income, challenges, and adaptive strategies reflect ongoing efforts to satisfy these psychological needs, which in turn shapes motivation quality, persistence, and perceptions of future career opportunities. As a result, autonomy, competence, and relatedness direct the experience and satisfaction of freelance journalists in different media environments.

5. Conclusions

This study examined freelance journalism in national media organizations, focusing on the different aspects of freelancers’ working conditions. In fact, this study adds knowledge to the existing gaps in the literature. Academic studies often overlook the role of freelancers working in various parts of the world, under different political conditions and media systems, leading to their exclusion from research samples (Massey & Elmore, 2018; Tahir et al., 2024; Ladendorf, 2013; Rasciute, 2017). This study interviewed 15 subjects, including 3 accountable individuals who interact with freelancers in the national media organizations and 12 freelancers who practice freelancing nationally. Additionally, this study investigated the working conditions and challenges faced by freelance interviewees in a vital area of the Middle East and North Africa. Furthermore, this study provides significant insights by providing recommendations for improving the work conditions of freelancers in the Emirati media ecosystem.

To address the research question concerning the working conditions of freelancers within national media organizations, the majority of interviewees tend to be forced into the freelancing profession for various reasons, such as layoffs due to old age, lack of employment opportunities, and COVID-19 repercussions, which disproportionately affect freelancers (Svetlana, 2022). This indicates that externally imposed limits drove some members of our research sample to pursue freelancing to fulfill life’s obligations. Financial incentives are important extrinsic motivators for freelance journalists, according to SDT (Morris et al., 2022).

Some freelance interviewees chose freelancing as a personal decision, motivated by their passion for journalism, a desire for greater flexibility, and the goal of increasing their income. This is consistent with other studies, which found that freelancers are motivated to work in the media sector by the freedom to move from one project to another (Purovaara, 2022). Their sense of autonomy allows them to select and engage in work they really prefer, which in turn boosts intrinsic motivation, which is rooted in a genuine interest in an activity and based on the belief that the action aligns with one’s own values and objectives. As a result, most purposeful behaviors are driven by many motivations, whether intrinsic or extrinsic. It leads to self-assurance, enhanced performance, creativity, perseverance, and overall well-being. Nevertheless, the freelancers’ desire to increase income represents an extrinsic motivator influenced by external pressures. Accomplishing this target boosts their overall well-being, happiness, and satisfaction. On the other hand, failing to meet this goal could result in need thwarting, dissatisfaction, and decreased well-being instead of satisfaction. However, regardless of diverse individual interests and preferences, competence, autonomy, and relatedness are essential requirements for general well-being according to SDT (Maggino, 2023), and fulfilling these needs leads to an increase in self-motivation as well as improved mental health (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

There are two interpretations for our study; first, we can conclude that the uncertainty and precarity faced by freelance journalists undermines self-fulfillment. This study found that the expertise of freelance journalists is often dismissed due to cost-cutting measures in increasingly saturated markets, where new, younger entrants are willing to work for less and are influenced by disruptive technologies. Limitations on autonomy undermine control over work conditions and prevent well-being. On the other hand, freelancers operate within their area of expertise, which supports competence and sustains intrinsic motivation. Although there are obstacles that freelancers encounter in such a profession, their connections in the journalism and media field enhance relatedness support, since their interactions, collaborations, and belonging to a work community in a media environment increase their intrinsic motivation, well-being, and overall job satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

In both forced and personal choice, freelancing is still a traditional path to job security, as pointed out by the literature (Oleshko & Mukhina, 2022). Therefore, the majority of freelance interviewees are aware of the significance of social networking for freelance opportunities, and they have a positive relationship with their freelancer colleagues as well as with the organizations that make use of their services. Therefore, the need for relatedness plays an important role in motivation and well-being. As freelance journalists practice freelancing, they interact and collaborate with others, including accountable individuals such as editors and their colleagues. As a result, they feel and experience connection and belonging within the media organization. This increases their intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction. Relatedness also satisfies autonomy and competence because these relationships can provide autonomy support (e.g., feedback and mutual trust), even as freelancers continue to face autonomy constraints, such as limited article words and contractual limits (Deci & Ryan, 2000).