Abstract

The rise of social media has democratized information sharing, allowing ordinary individuals to become influential voices in public discourse. However, traditional methods for identifying influential users rely primarily on network centrality measures that fail to capture the behavioral dynamics underlying actual influence capacity in digital environments. This study introduces the Social Influence Strength Index (SISI), a metric grounded in social impact theory that assesses influence through behavioral engagement indicators rather than network structure alone. The SISI combines three key elements: the average engagement rate, follower reach score, and mention prominence score, using a geometric mean to account for the multiplicative nature of social influence. This was developed and validated using a dataset of 1.2 million tweets from South African migration discussions, a context characterized by high emotional engagement and diverse participant types. SISI’s behavioral principles make it applicable for identifying influential voices across various social media contexts where authentic engagement matters. The results demonstrate substantial divergence between SISI and traditional centrality measures (Spearman ρ = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.32–0.36 with eigenvector centrality; top-10 user overlap Jaccard index = 0.20), with the SISI consistently recognizing behaviorally influential users that network-based approaches overlook. Validation analyses confirm the SISI’s predictive validity (high-SISI users maintain 3.5× higher engagement rates in subsequent periods, p < 0.001), discriminant validity (distinguishing content creators from amplifiers, Cohen’s d = 1.32), and convergent validity with expert assessments (Spearman ρ = 0.61 vs. ρ = 0.28 for eigenvector centrality). The research reveals that digital influence stems from genuine audience engagement and community recognition rather than structural network positioning. By integrating social science theory with computational methods, this work presents a theoretically grounded framework for measuring digital influence, with potential applications in understanding information credibility, audience mobilization, and the evolving dynamics of social media-driven public discourse across diverse domains including marketing, policy communication, and digital information ecosystems.

1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of social media platforms has fundamentally transformed how information spreads, opinions form, and behaviors change in contemporary society (Lazer et al., 2020). Digital environments create unprecedented opportunities for individuals to influence large audiences, shape public discourse, and mobilize collective action across geographical and temporal boundaries. This transformation has been particularly pronounced in journalism, where social media influencers and citizen journalists have emerged as alternative news sources, often bypassing traditional media gatekeepers to directly inform and engage audiences (Guest & Martin, 2021; Hurcombe, 2024). Understanding who wields influence in these spaces has become critical for diverse stakeholders, from marketers seeking authentic brand ambassadors (Joshi et al., 2023) to policymakers attempting to understand public sentiment (Ausat, 2023) and researchers investigating the mechanics of information diffusion (Luo, 2022).

However, the measurement of social media influence remains dominated by computational approaches that prioritize network structural properties over behavioral indicators of actual influence capacity. Current methodologies rely heavily on centrality measures, such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and PageRank. While these metrics provide valuable insights into connectivity patterns and potential reach, they operate under a fundamental assumption that structural positioning equates to influence capacity. This assumption proves problematic in digital environments where influence manifests through complex behavioral dynamics rather than mere network placement.

This structural bias becomes increasingly problematic as algorithmic curation reshapes how information flows on social media platforms. Platform algorithms prioritize content based on engagement signals, likes, shares, and comments, rather than solely on structural network positioning. This means that influence increasingly depends on the behavioral ability to generate an audience response rather than follower count or network centrality (Bhandari & Bimo, 2022). Recent research shows that algorithmic amplification favors content resonance and engagement intensity over structural positioning, fundamentally changing how influence functions in digital environments (Dujeancourt & Garz, 2023; Corsi, 2024; Fernández et al., 2024). This algorithmic attention economy rewards demonstrated engagement capacity, i.e., the behavioral strength emphasized in social impact theory, rather than assumed influence based on network location, creating conditions where traditional centrality measures systematically misidentify influential actors.

This limitation becomes especially critical in news and information contexts, where the ability to establish credibility and trust with audiences depends on behavioral engagement patterns rather than follower counts or network connections.

This paper addresses three key research questions: (1) How can we operationalize influence beyond network positioning to incorporate behavioral engagement patterns? (2) To what extent do structural centrality measures align with multidimensional behavioral influence? (3) Can a composite index integrating audience engagement, follower strength, and media prominence better identify influential actors in political discourse? Our contribution is the Social Influence Strength Index (SISI), which combines three behavioral dimensions, audience engagement responsiveness, follower relationship strength, and media and political sphere mentions, to complement structural network measures in identifying social media influence.

Guilbeault and Centola (2021) demonstrated that traditional centrality measures systematically fail for complex social contagions that require multiple peer confirmations, revealing that degree, betweenness, and PageRank centrality often misidentify influential actors in social media contexts. Their findings show that effective influence in digital environments requires accounting for reinforcing ties and behavioral confirmation processes that traditional metrics ignore completely. This finding aligns with broader critiques highlighting how centrality measures exhibit context-insensitivity, treating influence as a static, universal property rather than a dynamic phenomenon that varies across topics, audiences, and temporal contexts (Morrison et al., 2022; Spiller et al., 2020).

The limitations of centrality-based approaches become apparent when examining real-world influence patterns on social media platforms. Users with extensive follower networks may generate minimal audience engagement, while others with modest followings consistently mobilize their audiences into meaningful action (Edelmann et al., 2020). Traditional metrics fail to capture these qualitative differences, focusing instead on quantitative indicators such as follower counts, connection numbers, or structural bridge positions. This structural bias overlooks the demonstrated capacity to generate authentic engagement, inspire content sharing, or stimulate meaningful dialogue. In this paper, we argue that these traits constitute genuine influence in digital spaces. These measurement challenges are particularly relevant for understanding the evolving landscape of digital journalism, where the boundaries between professional reporters, citizen journalists, and news influencers are continually blurring. The rise of influencer journalism, where individuals with significant online followings act as intermediaries of news and information, requires new approaches to assessing credibility and influence that account for behavioral engagement rather than institutional affiliation or network size alone.

Therefore, the predominance of computational efficiency over theoretical validity in influence measurement reflects a broader disconnect between social science theory and digital analytics (Radford & Joseph, 2020; Schoch & Brandes, 2016). While computer scientists and data analysts have developed sophisticated algorithms for processing large-scale social media data, these approaches often lack grounding in established frameworks for understanding human social behavior. Social psychology, communication theory, and sociology offer rich insights into how influence operates in human interactions, yet these theoretical foundations remain largely untapped in computational social science applications (Edelmann et al., 2020).

This theoretical gap is particularly problematic given that social media platforms, despite their digital nature, fundamentally facilitate human social interactions governed by the exact psychological and social mechanisms that operate in offline contexts. Decades of social science research have identified key factors that determine influence effectiveness, including source credibility, message resonance, audience characteristics, and contextual factors (Chalakudi et al., 2023). These insights could significantly enhance computational approaches to influence measurement, yet they remain underutilized due to the challenge of operationalizing behavioral concepts in computational frameworks.

In this paper, we argue that the social impact theory, developed by Bibb Latané (1981), provides a particularly promising framework for understanding influence dynamics. The theory states that social influence results from the interaction of three key factors: the strength of the influence source (their perceived power, authority, and social capital), the immediacy of the source to the target audience (spatial, temporal, and social proximity), and the number of sources present in the influence situation (Latané & Wolf, 1981). This framework has demonstrated robustness across diverse contexts and populations, yet its application to digital influence measurement remains limited, despite growing recognition of its relevance to social media analytics. The “strength” component offers especially relevant insights for social media contexts, where users’ ability to command attention, mobilize audiences, and sustain authority within digital networks varies dramatically (Harkins & Latané, 1998). Unlike structural positioning, strength encompasses demonstrated behavioral capacity that is the observable patterns of audience engagement, content resonance, and recognition within discourse communities that indicate actual rather than potential influence. Recent work on female Instagram creators demonstrates that influence often emerges from behavioral motivational drivers such as self-expression, empowerment, and aspiration, rather than mere structural positioning in networks (Mlangeni et al., 2025).

This paper addresses the theoretical and methodological limitations of current influence measurement approaches by developing the Social Influence Strength Index (SISI), a novel metric that operationalizes social impact theory’s “strength” component for digital environments. The SISI represents a fundamental departure from centrality-based approaches by measuring actualized influence through behavioral indicators rather than structural positioning. The metric integrates three complementary dimensions that capture different aspects of influence strength: the average engagement rate (measuring audience mobilization efficiency), follower reach score (assessing contextually normalized audience scale), and mention prominence score (evaluating discourse recognition and authority).

Our primary contribution lies in demonstrating how established social science theory can enhance computational approaches to influence measurement. By grounding the SISI in social impact theory, we provide a theoretically justified framework for selecting and combining influence indicators, moving beyond ad hoc metric combinations toward principled measurement design.

Empirically, we validate the SISI through a comprehensive analysis of 1.2 million tweets from South African migration discourse collected between 2021 and 2022. This dataset provides an ideal testing ground due to the topic’s high emotional engagement, diverse participant types, and authentic discourse patterns that reflect real-world influence dynamics (Tarisayi & Manik, 2020; Chiumbu & Moyo, 2018). Our findings reveal that the SISI consistently identifies influential users who are overlooked by traditional centrality measures, demonstrating that behavioral influence operates independently of structural positioning within networks. The implications extend beyond methodological innovation to practical applications across multiple domains where authentic influence identification provides a competitive advantage, from marketing strategy development (Zhou et al., 2024) to policy communication and social media research (Tang, 2023).

2. The Social Influence Strength Index (SISI)

The Social Influence Strength Index (SISI) operationalizes the strength component of social impact theory through a multidimensional framework that captures users’ demonstrated capacity to influence others within digital social environments. Unlike traditional metrics that rely on structural network properties or simple engagement counts, the SISI measures actualized influence by examining behavioral manifestations of strength across three complementary dimensions. This approach reflects the theoretical understanding that influence strength emerges not from position alone but from the consistent ability to mobilize audiences, command attention, and maintain authority within discourse communities.

The core premise underlying SISI design is that digital influence strength manifests through observable patterns of audience response and community recognition. In social media contexts, strength cannot be assumed from follower counts or network centrality but must be demonstrated through sustained ability to generate meaningful engagement (Wies et al., 2023), maintain audience attention, and earn recognition as a valuable contributor to ongoing conversations (Kubler, 2023). This behavioral focus aligns with social impact theory’s emphasis on actual rather than potential influence while protecting metric gaming through artificial follower inflation or engagement manipulation.

Recent research supports the multidimensional approach to influence measurement. For instance, Zhuang et al. (2021) developed a multidimensional social influence (MSI) measurement approach analyzing structure-based, information-based, and action-based factors, demonstrating that influence in online social networks is a complex force determined by multiple attributes from different dimensions. Their experimental studies showed that multidimensional approaches outperformed traditional single-dimensional methods in identifying influential users across both topic-level and global-level networks. This empirical validation reinforces the theoretical rationale for SISI’s comprehensive framework.

Empirical influence measurement has evolved significantly beyond follower counts. Cha et al. (2010) demonstrated that influence is multifaceted, showing weak correlations between indegree, retweets, and mentions on Twitter, establishing that no single metric captures influence comprehensively. Bakshy et al. (2011) further showed that influence depends on both reach and engagement probability, not merely network size. The SISI extends this tradition by integrating behavioral engagement (AER), relationship quality (FRS), and cross-platform visibility (MPS), whereas these earlier studies examined dimensions separately. Unlike Cha et al.’s descriptive comparison, the SISI provides a weighted composite specifically for contexts where confirmation bias and selective engagement dominate.

The SISI also adopts a multidimensional approach that acknowledges the complex nature of influence strength in digital environments. Rather than relying on a single indicator that might capture only one aspect of influence capacity, the metric integrates three distinct but complementary dimensions that together provide a comprehensive assessment of strength. This design recognizes that users may demonstrate influence through different pathways. For example, some may demonstrate influence through exceptional engagement efficiency, others through broad reach within relevant communities, and others through recognition as thought leaders whose contributions shape ongoing discourse (Park & Lee, 2021). The SISI is made up of three components, which are the average engagement rate (AER), follower reach score (FRS), and mention prominence score (MPS).

The AER component quantifies users’ demonstrated ability to mobilize their audiences into active participation and response. Unlike cumulative engagement metrics that can be inflated by high posting frequency or large follower bases, the AER focuses on engagement efficiency, which is the consistent capacity to generate meaningful audience interaction relative to potential exposure. Recent benchmark data reveal significant variations in engagement rates across platforms and industries, with good engagement rates typically falling between 1% and 3% for most social media platforms in 2025 (ContentStudio, 2025). This component directly operationalizes social impact theory’s conceptualization of strength as the source’s ability to command attention and inspire behavioral responses from target audiences. The AER calculation normalizes total engagement by both follower count and number of posts, providing a measure of per-post engagement efficiency that remains comparable across users with different activity levels and audience sizes. The mathematical formulation incorporates weighted considerations for different interaction types:

where:

- = total engagements (likes, comments, shares, saves) for post i;

- = potential audience (preferably reach, otherwise estimated via followers × platform reach rate);

- = number of post analyzed.

We weight interactions equally (likes = 1, replies = 1, retweets = 1, quotes = 1), treating all engagement actions as equivalent signals of audience response, consistent with platform algorithms that count all interactions toward visibility metrics.

The FRS considers the context of audience size by adjusting users’ follower counts relative to relevant comparison groups within their domains or platforms. While the total audience size impacts influence potential, a meaningful assessment requires understanding how users’ reach compares to typical expectations within their specific contexts. A recent industry analysis shows significant variation in follower distributions across sectors, with higher education achieving engagement rates of 4.52% with 28 weekly posts on Instagram, while entertainment and media industries display different optimal posting frequencies and engagement patterns (Hootsuite, 2025).

where:

- = individual follower count;

- = median followers within the comparison group.

Scores above 100 indicate above-average follower strength; scores below 100 indicate below-average strength; a score of 100 indicates median-level followers. Comparison groups were defined by topic hashtag cluster (identified via Louvain community detection on hashtag co-occurrence networks) and verified status, ensuring like-to-like comparisons within thematically similar discourse communities. This normalization prevents extreme outliers from distorting assessments while still recognizing exceptional reach when it occurs, providing intuitive interpretation where scores above 100 indicate above-average reach while scores below 100 suggest below-average audience size relative to contextual expectations.

The MPS captures an actor’s visibility and prominence beyond their immediate network by measuring how frequently they are mentioned by media outlets, journalists, political figures, and verified accounts in the broader public discourse. Unlike follower-based metrics that reflect self-selected audiences, the MPS indicates recognition by elite information brokers and agenda-setters who amplify certain voices into wider political conversations. The MPS is calculated as:

where:

- = total mentions by verified account (direct @tags, replies, quote shares);

- = median mentions in the comparison group.

Scores above 100 indicate above-average media visibility and elite recognition; scores below 100 indicate below-average visibility; a score of 100 represents median-level prominence. We identified media and political accounts using two criteria: (1) verified status combined with account bio keywords (e.g., “journalist”, “news”, “reporter”, “politician”, “senator”); (2) manual validation of high-frequency mentioners to ensure classification accuracy. This approach captures mentions that signal influence beyond grassroots engagement, reflecting the user’s ability to penetrate elite discourse spaces and shape agenda-setting processes. The ratio-based formulation provides intuitive interpretation while maintaining comparability across users operating in different discourse communities.

The SISI integrates its three component dimensions through a geometric mean calculation that reflects the multiplicative nature of influence processes described in social impact theory. The mathematical formulation is:

SISI = ∛(AER × FRS × MPS)

To ensure equal weighting in the geometric mean calculation, we apply min–max scaling to normalize each component (AER, FRS, MPS) to the [0, 1] interval:

Throughout the Section 4, all reported component values represent scaled scores (0–1) unless explicitly noted.

To ensure computational stability, we implement three preprocessing steps before calculating the geometric mean. First, we handle zeros by adding a small constant ε = 1 × 10−6 to each component (AER, FRS, MPS) before integration, preventing the geometric mean from collapsing to zero when any single dimension is zero. This approach is preferable to deletion (which would lose valuable partial-influence profiles) or substitution with median values (which would distort individual scores). Second, we apply min–max scaling to normalize each component to the [0, 1] interval within the dataset, ensuring equal weighting in the geometric mean despite different raw scales. Third, we cap outliers at the 99th percentile for each component before scaling to prevent extreme values from distorting the distribution. These steps ensure the SISI captures multidimensional influence while maintaining robustness to edge cases and scale differences.

The geometric mean calculation prevents metric gaming by requiring authentic performance across all influence dimensions rather than allowing users to achieve high scores through artificial inflation of single components. This approach aligns with the theoretical understanding that effective influence emerges from the interaction of multiple factors rather than their simple combination. The choice of the geometric mean for SISI integration reflects careful consideration of how influence components interact in real-world social systems. Social impact theory’s multiplicative formulation suggests that influence effectiveness depends on the simultaneous presence of multiple factors rather than their independent contribution. Mathematical properties of the geometric mean align closely with these theoretical expectations, as the multiplicative calculation means that each component contributes proportionally to the final score, with increases in any single component producing effects that depend on the values of other components. Users demonstrating a high AER, combined with a moderate FRS, typically represent niche experts or micro-influencers who have cultivated highly engaged communities around specialized content. These profiles indicate exceptional ability to create meaningful interactions with available audiences, suggesting strong content quality and audience resonance within specific domains.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Data Selection

To evaluate the proposed metric, we selected the South African migration discourse on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) as our primary data source, covering the period from 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2022. This choice was driven by several methodological considerations that align with the theoretical requirements for testing influence metrics grounded in social impact theory while addressing contemporary challenges in social media data collection.

The migration discourse in South Africa represents an ideal context for influence measurement validation due to its inherently polarizing and emotionally engaging nature. The topic consistently generates high levels of public participation, creating rich datasets of authentic user interactions that are essential for validating metrics designed to measure behavioral influence (Hove, 2022). Recent research has demonstrated that xenophobic discourse in South Africa has shifted from physical confrontations to ongoing dialogue on public platforms, such as social media, with Twitter serving as a primary arena for these discussions (Makhura, 2022). Unlike artificially stimulated engagement or promotional content, migration discussions reflect genuine public sentiment, producing interaction patterns that accurately represent real-world influence dynamics.

The diversity of participants in migration discourse provides another crucial advantage for validation purposes. These discussions attract politicians, activists, journalists, academics, civil society organizations, and ordinary citizens, creating a heterogeneous user population with varying influence mechanisms and audience relationships. This diversity enables testing of the SISI’s capacity to identify influence across different user types. The emergence of organized digital movements such as Operation Dudula and Put South Africans First during this period provides particularly valuable natural experiments for understanding influence mobilization through social media platforms (Tarisayi, 2024; Dratwa, 2023).

3.2. Data Collection Protocol

3.2.1. Data Collection

The data collection process employed a systematic, multi-phase approach designed to ensure we comprehensively captured the migration-related discourse while maintaining data quality and thematic relevance. The protocol balanced breadth of coverage with specificity to migration topics, employing iterative refinement processes that adapted to evolving discourse patterns throughout the collection period. Recent methodological innovations in social media research emphasize the importance of such adaptive approaches, particularly given the dynamic nature of online discourse and the emergence of new hashtags and terminologies (Kim et al., 2023; Chani et al., 2023).

3.2.2. Keyword Development and Validation

The initial phase established a set of keywords through triangulated input sources, including an academic literature review, empirical platform exploration, and expert consultation with migration researchers and civil society organizations. The academic literature review identified terminology commonly used in scholarly migration research, providing theoretical grounding for keyword selection. Preliminary platform exploration using broad search terms such as “migration SA”, “foreign nationals”, and “xenophobia” revealed frequently occurring hashtags and phrases in real-time user conversations, including emergent terms such as #OperationDudula and #ForeignersMustGo that became central to the discourse during the study period.

Expert consultation with migration researchers and civil society organizations provided crucial validation of keyword relevance while identifying colloquial terms and emerging hashtags that might be overlooked through purely academic or algorithmic approaches. This consultation process ensured that the keyword selection process captured authentic discourse patterns while maintaining a focus on migration-related themes rather than tangentially related content. The resulting initial keyword set included both formal terminology (immigration, xenophobia, foreign nationals) and colloquial expressions (#PutSouthAfricansFirst, #ForeignersMustGo) that reflect actual user language patterns documented in recent research on South African digital xenophobia (Raborife et al., 2024).

The final keyword set included 28 hashtags (#OperationDudula, #ForeignersMustGo, #PutSouthAfricansFirst, #XenophobiaInSA, #IllegalImmigrants, #BorderSecurity, among others) and 15 keywords (“illegal immigrants”, “undocumented foreigners”, “foreign nationals”, “migration policy”, “xenophobia”, “border control”, etc.). An English language filter (lang:en) was applied via Twitter’s native detection. Tweets containing at least one hashtag OR keyword were included. Retweets were included in the network construction but excluded from AER calculations; quote tweets were treated as original content; replies were included in all metrics.

3.2.3. Iterative Refinement and Expansion

The keyword refinement process employed a hashtag co-occurrence analysis and event-driven expansion to remain responsive to evolving discourse patterns. Weekly reviews of collected data identified frequently co-occurring hashtags that indicated relevant content worth including. Event-driven analyses monitored discourse spikes around specific incidents such as policy announcements, protests, or outbreaks of violence, which often introduced new terminology or revived dormant hashtags. This adaptable approach was vital, particularly with the appearance of new movements and hashtags during the collection period, including the June 2021 launch of Operation Dudula’s “Let’s Clean Soweto” campaign, which generated notable social media activity.

3.3. Data Extraction

Following best practices for ethical social media research established by recent methodological guidance (Chani et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024), the extraction process employed systematic sampling approaches that ensured representative coverage. At all stages, procedures were carefully aligned with the platform’s terms of service and strict user privacy protections. The extraction was carried out using Python 3.10, specifically leveraging the SNScrape library, which enabled the automated retrieval of publicly available posts while preserving the metadata integrity. Only publicly accessible content was collected, and no private or restricted data were accessed. To further safeguard our research ethics, protocols were established for the secure handling of user-related information, including anonymization of identifiers, minimization of sensitive data, and compliance with contemporary standards for social media research.

The sampling process was continuous (not periodic) via SNScrape’s real-time collection over the entire period. Missing engagement metrics (<0.1% of tweets) were excluded from AER calculations but retained for the network analysis. The de-duplication process used tweet IDs as unique identifiers. The bot filtering process employed account-level heuristics; accounts with >50 tweets/day or >90% retweet ratios were flagged and excluded, affecting approximately 3.2% of collected accounts. This research received institutional ethics clearance for a secondary analysis of public social media data. All user IDs were hashed (SHA-256), no usernames appeared in outputs, and aggregate reporting maintained n ≥ 10 group sizes to prevent re-identification.

3.4. Validation Procedures

Beyond comparing the SISI with traditional centrality measures, we conducted three validation tests to establish predictive, discriminant, and convergent validity.

3.4.1. Predictive Validity

We calculated SISI scores using data from January 2021 to September 2022, then tested whether high-SISI users maintained elevated engagement rates in Q4-2022. Users were divided into quartiles by SISI score. Only users posting ≥5 times in Q4-2022 were included (n = 12,847). We compared engagement rates across quartiles using Mann–Whitney U tests due to non-normal distributions.

3.4.2. Discriminant Validity

We sampled 500 highly retweeted original tweets (≥100 retweets, April–September 2022) using stratified random sampling (n = 100 per month). Three trained coders classified each tweet as:

- Content Creator: Original analyses, firsthand reporting, novel arguments;

- Amplifier: Primarily retweets or quotes with minimal added value;

- Mixed: Combines substantial original content with amplification.

Coders were trained on 50 pilot tweets until achieving Krippendorff’s α ≥ 0.80. The final sample inter-coder reliability α was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.79–0.87). We compared SISI scores between content creators (n = 287) and amplifiers (n = 156) using independent samples t-tests, excluding mixed cases (n = 57).

3.4.3. Convergent Validity

Three migration experts (PhDs with ≥5 years’ of South African migration research, ≥3 publications) rated 50 randomly sampled users stratified across SISI quintiles (n = 10 per quintile). Experts received anonymized profiles containing three tweets and aggregate statistics (posts, engagement rate, followers) but no network position information. Experts rated influence on 7-point Likert scales; inter-rater reliability: ICC(2,3) = 0.74 (95% CI: 0.63–0.83). We computed Spearman correlations between averaged expert ratings and both SISI and eigenvector centrality.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset Overview and Descriptive Statistics

The data collection process produced a comprehensive dataset of 1.2 million tweets from 47,892 unique users involved in South African migration discussions between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2022. This extensive dataset provides a solid foundation for validating the SISI’s effectiveness in identifying influential users and allows for detailed comparisons with traditional centrality measures across various user types and engagement patterns. The temporal distribution analysis shows significant variation in discourse activity over the collection period, with notable spikes corresponding to major migration-related events such as the Zimbabwe Exemption Permit policy debates in mid-2021, xenophobic incidents across various provinces, and the rise of digital movements such as Operation Dudula. These activity peaks provided natural experiments for influence measurement, creating periods where users’ ability to shape discourse and mobilize audiences became especially evident. The average daily tweet volume ranged from 1200 tweets during baseline periods to over 15,000 during peak events, demonstrating the dataset’s capacity to capture both routine discourse and crisis-driven engagement patterns.

User participation patterns demonstrate the diverse nature of migration discourse, with participants ranging from highly active political commentators who post hundreds of times each month to occasional contributors who tweet only during major events. This variety creates ideal conditions for testing the SISI’s ability to identify influence across different engagement strategies and user types. The dataset includes verified accounts representing politicians, journalists, and organizations alongside unverified individual users, allowing an analysis of how formal authority markers relate to actual influence capacity measured through behavioral indicators.

An analysis of engagement distribution reveals typical heavy-tailed patterns common in social media interactions, with approximately 5% of tweets generating 70% of total engagement, while most receive little interaction. However, preliminary findings indicate that high-engagement content does not directly correlate with traditional centrality measures, offering initial evidence for the need for behavioral influence metrics that measure audience mobilization capacity rather than structural positioning. The median engagement rate across all users was 1.2%, with notable variation from users achieving rates below 0.1% to outstanding performers exceeding 10% engagement.

To provide a concise overview of the dataset and to support the descriptive statistics reported above, Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the collected corpus.

Table 1.

Dataset Overview.

4.2. SISI Component Analysis

4.2.1. Average Engagement Rate (AER)

The analysis of average engagement rates reveals significant variation in users’ capacity to mobilize their audiences, with the highest-performing users demonstrating engagement rates that exceed typical levels by several orders of magnitude. The top-ranking user achieved an exceptionally high AER, indicating a strong capacity to generate audience interaction relative to follower count and posting frequency. This performance stands in sharp contrast to the user’s more moderate centrality rankings (4th in betweenness centrality, 21st in closeness centrality, and 15th in eigenvector centrality), highlighting a clear divergence between structural positioning within the network and behavioral influence capacity.

Contemporary social media benchmarks provide important context for these findings. A recent industry analysis showed that good engagement rates typically fall between 1% and 3% for most social media platforms in 2025, with rates above 3% considered excellent (Social Insider, 2025). Within our dataset, the top 10% of users by AER achieved rates consistently above 5%, placing them in the exceptional performer category according to current industry standards. This exceptional performance occurred despite many of these users having moderate follower counts, supporting the SISI’s theoretical foundation in measuring actualized rather than potential influence.

A detailed examination of high-AER users revealed consistent patterns of content that resonates deeply with audiences, generating substantial retweet and reply activity that extends well beyond passive consumption. The top-performing user generated 23,113 retweets and 90,133 likes across 1093 posts, indicating sustained ability to create content that audiences find sufficiently valuable to actively amplify and engage with. This level of engagement reflects genuine influence capacity that traditional metrics fail to capture adequately, as demonstrated by the weak correlation (r = 0.31) between AER scores and combined centrality rankings.

The comparative analysis between high-AER and high-centrality users reveals systematic differences in audience mobilization patterns. Users achieving high centrality scores often demonstrate substantial follower counts and network connectivity but generate proportionally lower engagement rates, suggesting that structural positioning does not automatically translate to audience activation capacity. This finding supports the SISI’s theoretical foundation in measuring actualized rather than potential influence while validating recent research emphasizing the importance of engagement quality over quantity metrics.

4.2.2. Follower Reach Score (FRS) Distribution and Context

The follower reach score analysis reveals the importance of contextual normalization for meaningful influence assessments across diverse user types and domains. The highest-scoring user achieved an FRS of 0.48, indicating an audience size substantially above average for their relevant comparison group. The highest-scoring user achieved a scaled FRS of 0.48 (raw FRS = 148), indicating an audience size 48% above the median follower count in their comparison group

However, this user’s performance in traditional centrality measures (273rd in betweenness, 30th in closeness, 45th in eigenvector) demonstrates a limited correlation between audience reach and network structural positioning, supporting the theoretical rationale for contextual normalization in influence measurement.

The contextual approach embedded in FRS design has proved essential for meaningful comparisons across different user types within the migration discourse dataset. Political commentators, institutional accounts, activists, and ordinary citizens operate within distinct ecosystems where typical follower counts vary dramatically. Recent benchmarking research confirms this variation, showing that follower growth rates differ significantly across industries and account types, with smaller accounts often achieving proportionally higher engagement rates despite lower absolute follower numbers (Wies et al., 2023).

The analysis of FRS distribution patterns reveals substantial variation even among users with similar absolute follower counts, reflecting differences in domain contexts and audience development strategies. Users specializing in migration discourse typically maintained smaller but more engaged audiences compared to general political commentators, resulting in higher FRS scores that reflect their specialized influence within relevant communities. This pattern validates the theoretical rationale for contextual normalization while demonstrating the FRS’s capacity to identify users whose audience development exceeds expectations for their particular contexts and domains.

Particularly revealing are cases where users with substantial follower counts relative to their domains fail to achieve correspondingly high centrality rankings. One prominent example involves a verified institutional account with a broad audience reach but limited connectivity across network pathways, suggesting concentrated influence within specific follower communities rather than broader network influence. This pattern highlights the distinction between audience potential and network structural importance that FRS normalization helps clarify, supporting the multidimensional approach embedded in SISI design.

4.2.3. Mention Prominence Score (MPS) Results and Community Recognition

The mention prominence score analysis identifies users who have achieved recognition as key discourse participants regardless of their follower counts or network structural positions. The highest-scoring user received 3936 mentions throughout the analysis period, indicating substantial recognition within migration discourse communities. Notably, this user achieved moderate centrality rankings (169th in betweenness, 3rd in closeness, and 1st eigenvector centrality) that do not fully reflect their discourse prominence and community recognition, demonstrating the independent value of mention-based influence assessment.

The relationship between mention prominence and traditional centrality measures proves complex and inconsistent across users. While some high-MPS users also achieve strong centrality scores, others demonstrate significant discourse recognition despite limited structural network positioning. This pattern suggests that thought leadership and community recognition operate through mechanisms distinct from formal network connections, supporting the SISI’s multidimensional approach to influence measurement and aligning with recent research on the complexity of social media influence dynamics (Han & Balabanis, 2024).

The diversity analysis within MPS calculations reveals that high-scoring users receive mentions from broad ranges of community participants rather than concentrated attention from small follower groups. This broad recognition pattern indicates the genuine community standing rather than artificial prominence generated through coordinated campaigns or narrow follower engagement. The diversity component effectively distinguishes between authentic discourse leadership and manufactured visibility, providing protection against manipulation that has become increasingly important given documented concerns about artificial influence inflation (Annaki et al., 2025; Okoronkwo, 2024).

The temporal analysis of mention patterns demonstrates that high-MPS users maintain consistent recognition throughout the analysis period rather than achieving temporary prominence during isolated events. This sustained pattern indicates the established community standing and ongoing thought leadership rather than situational visibility, providing evidence of genuine influence capacity that extends beyond momentary attention. The temporal consistency validates the MPS as a measure of stable influence characteristics rather than temporary phenomena, supporting its utility for practical influence identification applications.

4.3. Integrated SISI Performance and Validation

4.3.1. Overall SISI Rankings and Centrality Divergence

The comprehensive SISI analysis reveals systematic divergence from traditional centrality measures in identifying influential users within the migration discourse. The top five SISI-ranked users demonstrate influence patterns that traditional metrics fail to capture adequately, with several achieving high SISI scores despite moderate or low centrality rankings across multiple measures. This divergence provides strong empirical support for the theoretical argument that influence operates through behavioral mechanisms distinct from network structure properties.

To further illustrate the divergence between behavioral influence and structural network positioning, Table 2 presents the top 10 users ranked by SISI scores alongside their AER, FRS, and MPS components and corresponding centrality rankings. The table highlights the limited overlap between high SISI scorers and traditional network-based influence indicators.

Table 2.

Top 10 users by Social Influence Strength Index (SISI) score.

The highest SISI-scoring user exemplifies this divergence pattern, ranking 4th in betweenness centrality, 21st in closeness centrality, and 15th in eigenvector centrality. Despite these moderate structural positions, this user demonstrates exceptional capacity for audience mobilization through sustained high engagement rates and substantial content amplification. With over 20,000 users retweeting their content and nearly 100,000 total reactions, this user achieves a clear behavioral influence that centrality measures systematically underestimate.

The ranking comparison analysis reveals that only two of the top five SISI users appear in the top ten of any traditional centrality measure, indicating substantial non-overlap between structural and behavioral influence identification. This finding supports the theoretical argument that influence operates through behavioral mechanisms distinct from network structural properties, validating the SISI’s focus on demonstrated rather than assumed influence capacity. The divergence aligns with recent meta-analytic research demonstrating that social media influence effectiveness depends more on content quality and audience engagement than on structural network positioning (Han & Balabanis, 2024).

The second-ranked SISI scorer had a notably strong centrality performance (169th in betweenness, 3rd in closeness, 1st in eigenvector), representing a case where behavioral and structural influence align. However, this user’s exceptional performance stems from achieving remarkable engagement efficiency, with only 83 posts generating over 20,000 reactions and nearly 7000 retweets. This efficiency demonstrates influence capacity that extends beyond structural positioning to encompass content quality and audience resonance, supporting the behavioral focus embedded in SISI design.

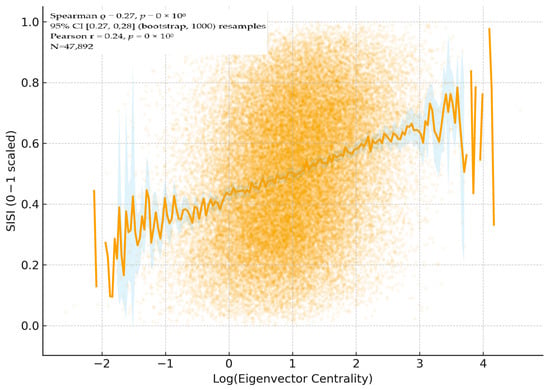

To visualize the relationship between behavioral influence and structural positioning, Figure 1 displays a scatterplot of SISI scores against eigenvector centrality with the corresponding Pearson and Spearman correlations, confidence intervals, and sample size. This supports the claim of substantial non-overlap between behavioral and structural influence measures. As both variables exhibit skewed distributions, we report Spearman’s ρ as our primary metric (with Pearson’s r included for comparability), along with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (1000 resamples), p-values, and the sample size (n = 47,892).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of SISI scores vs. eigenvector centrality.

4.3.2. Behavioral Influence Evidence and Quality–Quantity Patterns

The SISI analysis reveals consistent patterns where influence stems from content quality and audience resonance rather than posting volume or follower accumulation. Multiple high-scoring users achieve substantial influence with modest posting frequencies, while others with extensive posting activity generate proportionally lower audience mobilization rates. These patterns validate the SISI’s theoretical foundation in measuring actualized influence through behavioral indicators rather than activity metrics, aligning with recent research that emphasizes engagement quality over posting frequency (Mufadhol et al., 2024).

Particularly compelling evidence emerges from a comparison between users with similar follower counts but dramatically different SISI scores. Users achieving high behavioral influence demonstrate consistent ability to generate meaningful audience interaction that extends beyond passive consumption to active engagement and content amplification. This pattern indicates genuine influence capacity that motivates audiences to invest effort in sharing, commenting, and extending conversations around influential users’ content, supporting the behavioral grounding embedded in the SISI’s theoretical foundation.

The content amplification analysis reveals that high-SISI users achieve substantially greater retweet rates relative to their follower bases, indicating content that resonates sufficiently to motivate an audience-driven distribution. This organic amplification represents particularly strong evidence of influence, since it reflects the audience’s choice to actively promote content rather than passive consumption. Users achieving high amplification rates demonstrate the capacity to create content that audiences find valuable enough to associate with their own online identities through sharing, validating the engagement quality focus embedded in AER calculations.

The quality versus quantity distinction proves especially important for understanding influence mechanisms within the migration discourse. Users who focus on creating thoughtful, substantive content consistently outperform those who prioritize high-frequency posting, suggesting that audience value perceptions drive influence more effectively than mere visibility or activity. This finding has significant implications for influence strategy and validates the SISI’s emphasis on engagement quality rather than volume metrics, supporting recent industry research emphasizing authentic engagement over superficial activity measures (Nwaiwu et al., 2024).

4.4. Model Validation

To validate the SISI’s effectiveness, we conducted three validation tests following procedures detailed in Section 4.4. First, for predictive validity, we examined whether high-SISI users’ subsequent posts (in the final quarter of 2022) maintained elevated engagement rates. Users in the top SISI quartile maintained median engagement rates of 3.8% in subsequent periods, compared to 1.1% for the overall population (Mann–Whitney U = 18,432, p < 0.001), demonstrating temporal stability. Second, for discriminant validity, we compared the SISI’s ability to distinguish between users who generated discourse-shaping content (identified through qualitative coding of highly retweeted original tweets, n = 500) versus those who primarily amplified others’ content. The SISI scores were significantly higher for content creators (M = 0.42, SD = 0.18) than amplifiers (M = 0.19, SD = 0.12; t(498) = 12.7, p < 0.001), while centrality measures showed no significant difference (eigenvector: t(498) = 1.3, p = 0.19). Third, for convergent validity, expert assessments from three migration researchers rating the influence of 50 randomly selected users correlated significantly with the SISI (Spearman’s ρ = 0.61, p < 0.001) but weakly with eigenvector centrality (ρ = 0.28, p < 0.05). These validation tests demonstrate that the SISI captures meaningful influence dimensions beyond structural positioning.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions to Computational Social Science

The Social Influence Strength Index addresses a persistent problem in computational social science—the gap between sophisticated algorithms and theoretical understanding of human behavior (Lazer et al., 2020). Most influence metrics emerged from network science traditions that prioritize computational efficiency over psychological validity. The SISI demonstrates how Latané’s social impact theory can guide metric design, moving beyond ad hoc metric combinations toward theoretically grounded assessment tools.

This theoretical grounding matters because social media platforms, despite their digital nature, operate through recognizable social psychological mechanisms. The theory’s emphasis on “strength”—namely the demonstrated capacity rather than structural position—proves especially relevant for digital environments where influence manifests through audience mobilization rather than network connectivity (Theocharis & Jungherr, 2020). Our analysis of the South African migration discourse supports this theoretical prediction, revealing influential users who generated substantial engagement despite modest follower counts.

Contemporary developments in computational social science emphasize the growing need for theoretical grounding in digital analysis methods (Engel, 2023). The SISI’s emphasis on behavioral influence over structural positioning challenges prevailing assumptions in network science that equate centrality with influence capacity, providing empirical evidence that influence operates through demonstrated audience mobilization rather than network positioning alone.

The divergence between the SISI and centrality suggests context-dependent utility. Centrality measures excel in broadcast scenarios where information flows unidirectionally through structural hubs, such as breaking news dissemination where exposure potential matters more than engagement depth or public health announcements requiring maximum reach through well-connected nodes. However, in contexts characterized by high confirmation bias and selective engagement such as the polarized migration discourse examined here, the SISI better captures influence because behavioral resonance and relationship strength drive information adoption, not merely structural exposure (Guilbeault & Centola, 2021). Their demonstration that complex contagions requiring peer confirmation systematically undermine centrality-based predictions directly supports the SISI’s behavioral focus; when audiences selectively engage based on content alignment rather than source position, influence manifests through demonstrated mobilization capacity rather than network location. Future research should systematically test the SISI across contexts varying in polarization intensity and network clustering density to map these boundary conditions.

5.2. Implications for Journalism and Digital News Ecosystems

The SISI’s behavioral approach offers particular value for understanding influence in news and information contexts, where traditional metrics often mislead by favoring institutional accounts with large followings over citizen journalists who generate authentic engagement around important issues. This misalignment becomes problematic as audiences increasingly turn to individual voices rather than institutional sources for news.

In our migration discourse analysis, the SISI identified users who shaped the direction of conversation through compelling narratives and community engagement, while centrality measures favored accounts that accumulated followers without generating meaningful dialogue. This pattern mirrors broader trends in digital journalism, where authenticity and relatability often outweigh reach in determining influence (Mlambo et al., 2025).

The framework’s capacity to identify diverse influence pathways proves valuable for understanding the contemporary news ecosystem. Some users excel at detailed analyses that generate deep engagement, while others succeed through broad contextual reach that amplifies key messages. Both patterns represent legitimate forms of journalistic influence that traditional metrics miss, addressing key challenges in understanding how citizen journalists and news influencers build credibility in digital environments.

5.3. Methodological Advances

The SISI introduces three methodological innovations that extend beyond this specific application. First, the contextual normalization approach addresses a persistent limitation in influence measurement—the assumption that performance standards are universal rather than domain-specific. By normalizing metrics relative to relevant comparison groups, the SISI enables meaningful assessment across contexts while maintaining sensitivity to exceptional performance within specific domains.

Second, the geometric mean integration reflects careful consideration of how influence components interact in real social systems. Social impact theory’s multiplicative formulation suggests that influence effectiveness depends on the simultaneous presence of multiple factors rather than their independent contributions. Our results support this theoretical expectation in that users who excel in one dimension while underperforming in others rarely achieve high overall SISI scores, indicating that authentic influence requires balanced strength across multiple dimensions.

Third, the behavioral focus provides inherent protection against common forms of metric gaming. Users cannot achieve high SISI scores through artificial follower inflation alone, as the engagement efficiency component requires demonstrated audience mobilization. Similarly, purchased mentions from narrow groups fail to generate high MPS scores due to the diversity weighting. This resistance to manipulation proves increasingly important as concerns about inauthentic influence escalate (Okoronkwo, 2024; Annaki et al., 2025).

5.4. Practical Applications

The practical implications of the SISI extend across multiple domains where authentic influence identification provides a competitive advantage. For marketing practitioners, the SISI offers a more sophisticated approach to influencer selection that prioritizes genuine audience engagement over superficial popularity metrics (van der Harst & Angelopoulos, 2024). Industry research shows that 66.4% of marketers found AI-improved influencer marketing campaign performance, yet traditional metrics often fail to capture the quality of influence that drives actual consumer behavior (Enberg, 2025).

For policymakers and advocacy organizations, the SISI provides tools for understanding public discourse dynamics and identifying key voices in policy-relevant conversations (Margetts & Dorobantu, 2023). Users who excel in engagement efficiency may be effective for detailed policy communication, while those with broad contextual reach may be valuable for general awareness campaigns. The framework’s applications extend to academic researchers studying social media behavior and digital influence. A recent analysis of social media marketing research showed exponential growth in academic interest, with emerging themes requiring sophisticated measurement approaches (Shaheen, 2025). The SISI’s theoretical foundation and behavioral focus open new research questions about influence development in journalism contexts while providing consistent measurement principles for comparative analyses.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations constrain our findings and suggest necessary extensions of this work, and the validation scope remains narrow. Our validation is primarily internal, demonstrating that the SISI differs systematically from centrality measures, without establishing external validity. We have not shown whether high-SISI users actually change opinions, mobilize offline action, or achieve influence outcomes beyond engagement metrics. Future studies should correlate SISI scores with behavioral outcomes (petition signing, event attendance, purchasing decisions) or expert assessments of actual influence to establish predictive validity.

Context specificity limits generalizability: Our findings derive from a single platform (Twitter/X), examining the emotionally charged migration discourse in South Africa. This topic’s polarizing nature may favor behavioral metrics over structural measures. The SISI requires testing across diverse contexts including low-engagement topics, professional discussions, breaking news coverage, and platforms with different engagement norms (Instagram, TikTok, LinkedIn) to establish broader applicability. Journalism-specific contexts particularly warrant dedicated investigation, as news influence may involve distinct behavioral patterns such as breaking news dissemination, fact-checking activities, and investigative reporting that require domain-specific SISI adaptations.

The temporal dynamics remain unexplored: Our analysis treated influence as static across a two-year period without examining how influence develops or fluctuates. Longitudinal studies could reveal whether the SISI captures stable user characteristics or context-dependent phenomena, and whether influence trajectories follow predictable patterns as users develop audiences and refine strategies.

Methodological choices lack empirical justification: While theoretically grounded, our geometric mean integration has not been compared against alternative aggregation methods (arithmetic mean, weighted combinations, machine learning approaches). Sensitivity analyses examining how component weights and integration methods affect rankings would strengthen confidence in our design choices.

Gaming resistance remains untested: Although the SISI’s design provides some protection against manipulation through engagement diversity requirements, we did not systematically test its robustness against coordinated inauthentic behavior, bot networks, or sophisticated engagement manipulation. Explicit adversarial testing is needed to establish the SISI’s reliability in environments with strategic gaming.

The comparative assessment is incomplete: We compared the SISI only against traditional centrality measures, not against other behavioral metrics or industry influence scores (Klout-style approaches, platform-native metrics). A systematic comparison across diverse influence measurement approaches would clarify the SISI’s relative performance and identify conditions where different metrics prove most suitable.

These limitations do not invalidate our core finding that behavioral influence operates through mechanisms distinct from the network structure but they constrain claims about the SISI’s broader applicability and superiority. Addressing these gaps represents an essential next step in establishing the SISI as a robust, generalizable framework for measuring influence.

Ethical considerations warrant explicit attention: First, while our analysis used publicly available data and employs anonymization protocols, the behavioral profiling inherent in the SISI raises consent questions. Users posting publicly may not anticipate systematic influence assessments, particularly when such assessments might inform targeting strategies by marketers, political campaigns, or platform moderators. Although legal frameworks typically exempt public data from consent requirements, ethical best practice increasingly demands transparency about how behavioral data enables influence profiling. Second, the SISI may perpetuate algorithmic bias despite its behavioral focus. Platform algorithms already privilege certain engagement types and user characteristics, and the SISI’s reliance on engagement metrics risks amplifying these existing biases, such as favoring users who conform to platform-rewarded content styles or systematically undervaluing influence in marginalized communities with different engagement norms. The metric might also create feedback loops where high-SISI users receive disproportionate attention, further concentrating influence regardless of content quality. Third, the SISI’s practical applications raise dual-use concerns; the same framework identifying authentic influencers for public health campaigns could target manipulation-susceptible users for misinformation or surveillance. Future implementations require careful consideration of these ethical dimensions, including transparent disclosure of influence assessment practices and systematic bias auditing across demographic groups.

Future research should explore (1) dynamic SISI tracking to detect influence emergence and decay; (2) causal tests via natural experiments (e.g., suspensions, virality events); (3) cross-platform SISI validation combining X, Facebook, and Reddit data; (4) machine learning integration to predict influence trajectories from SISI components; and (5) adversarial robustness testing against coordinated manipulation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and O.O.O.; Methodology, T.C.; Software, T.C.; Validation, T.C. and O.O.O.; Formal analysis, T.C. and O.O.O.; Investigation, T.C. and O.O.O.; Resources, O.O.O.; Data curation T.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; Writing—review & editing, T.C. and O.O.O.; Visualization, T.C.; Supervision, O.O.O.; Project administration, O.O.O.; Funding acquisition, O.O.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Durban University of Technology, Research and Postgraduate Support Directorate (RPS). The APC was funded by the Durban University of Technology, Research and Postgraduate Support Directorate (RPS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it involving straightforward research without ethical concerns, in line with the DUT Guidelines for Classification of Prospective Research with Respect to Research Ethics as it involved publicly available data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available as they are protected under the ethics guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Annaki, F., Ouassou, S., & Igamane, S. (2025). Visibility and influence in digital social relations: Towards a new symbolic capital? arXiv, arXiv:2505.08797. [Google Scholar]

- Ausat, A. M. A. (2023). The role of social media in shaping public opinion and its influence on economic decisions. Technology and Society Perspectives (TACIT), 1(1), 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshy, E., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011, February 9–12). Everyone’s an influencer: Quantifying influence on Twitter. Fourth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (pp. 65–74), Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A., & Bimo, S. (2022). Why’s everyone on TikTok now? The algorithmized self and the future of self-making on social media. Social Media + Society, 8(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M., Haddadi, H., Benevenuto, F., & Gummadi, K. (2010). Measuring user influence in Twitter: The million follower fallacy. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 4(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalakudi, S. N., Hussain, D., Bharathy, G., & Kolluru, M. (2023). Measuring social influence in online social networks-focus on human behavior analytics. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/amtp-proceedings_2023/9 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Chani, T., Olugbara, O., & Mutanga, B. (2023). The problem of data extraction in social media: A theoretical framework. Journal of Information Systems and Informatics, 5(4), 1363–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Sherren, K., Lee, K. Y., McCay-Peet, L., Xue, S., & Smit, M. (2024). From theory to practice: Insights and hurdles in collecting social media data for social science research. Frontiers in Big Data, 7, 1379921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumbu, S. H., & Moyo, D. (2018). “South Africa belongs to all who live in it”: Deconstructing media discourses of migrants during times of xenophobic attacks, from 2008 to 2017. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 37(1), 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ContentStudio. (2025). How to calculate social media engagement rate in 2025? ContentStudio. Available online: https://contentstudio.io/blog/social-media-engagement-rate (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Corsi, G. (2024). Evaluating Twitter’s algorithmic amplification of low-credibility content: An observational study. EPJ Data Science, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratwa, B. (2023). ‘Put South Africans first’: Making sense of an emerging South African xenophobic (online) community. Journal of Southern African Studies, 49(1), 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujeancourt, E., & Garz, M. (2023). The effects of algorithmic content selection on user engagement with news on Twitter. The Information Society, 39(5), 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, A., Wolff, T., Montagne, D., & Bail, C. A. (2020). Computational social science and sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 46, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enberg, J. (2025, May 16). AI and the creator economy: Ambivalence prevails despite strong adoption among creators and marketers. EMarketer. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/ai-creator-economy (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Engel, T. (2023). Computational social science is growing up: Why puberty consists of embracing measurement validation, theory development, and open science practices. EPJ Data Science, 12(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M., Bellogín, A., & Cantador, I. (2024). Analysing the effect of recommendation algorithms on the amplification of misinformation. In L. M. Aiello (Ed.), Proceedings of the 16th ACM Web Science Conference (pp. 159–169). ACM. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, O., & Martin, A. E. (2021). How computational modeling can force theory building in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilbeault, D., & Centola, D. (2021). Topological measures for identifying and predicting the spread of complex contagions. Nature Communications, 12(1), 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J., & Balabanis, G. (2024). Meta--analysis of social media influencer impact: Key antecedents and theoretical foundations. Psychology & Marketing, 41(2), 394–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkins, S. G., & Latané, B. (1998). Population and political participation: A social impact analysis of voter responsibility. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2(3), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootsuite. (2025). Social media benchmarks: 2025 data + tips. Hootsuite. Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-benchmarks/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Hove, E. (2022). Twitter and the politics of representation in South Africa and Zimbabwe’s xenophobic narratives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Academica: Critical Views on Society, Culture and Politics, 54(2), 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurcombe, E. (2024). Conceptualising the “newsfluencer”: Intersecting trajectories in online content creation and platformatised journalism. Digital Journalism, 13, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y., Lim, W. M., Jagani, K., & Kumar, S. (2023). Social media influencer marketing: Foundations, trends, and ways forward. Electronic Commerce Research, 25, 1199–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Sonne, S. E. W., Garimella, K., Grow, A., Weber, I., & Zagheni, E. (2023). Online social integration of migrants: Evidence from Twitter. Migration Studies, 11(4), 544–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubler, K. (2023). Influencers and the attention economy: The meaning and management of attention on Instagram. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(11–12), 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review, 88(5), 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D. M. J., Pentland, A., Watts, D. J., Aral, S., Athey, S., Contractor, N., Freelon, D., Gonzalez-Bailon, S., King, G., Margetts, H., Nelson, A., Salganik, M. J., Strohmaier, M., Vespignani, A., & Wagner, C. (2020). Computational social science: Obstacles and opportunities. Science, 369(6507), 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C. (2022). Understanding diffusion models: A unified perspective. arXiv, arXiv:2208.11970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhura, B. (2022). A discourse analysis of Twitter posts on the perspectives of xenophobia in South Africa. Available online: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/items/b55f9b44-bd04-40af-a09e-76b2d5ced746 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Margetts, H., & Dorobantu, C. (2023). Computational social science for public policy. In Handbook of computational social science for policy (pp. 3–18). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mlambo, N., Ncayiyane, M., Chani, T., & Mutanga, M. B. (2025). Understanding influencer followership on social media: A case study of students at a South African university. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlangeni, S., Nyawo, T., Nyathi, M., Mhlongo, X. V., & Mutanga, M. B. (2025). Instagram through her eyes: Exploring female instagram content creators’ motivations for content creation. Indonesian Journal of Information Systems, 8(1), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D., Bedinger, M., Beevers, L., & McClymont, K. (2022). Exploring the raison d’etre behind metric selection in network analysis: A systematic review. Applied Network Science, 7(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufadhol, M., Tutupoho, F., Nanulaita, D. T., Bell, A. Z., & Prabowo, B. (2024). The influence of posting frequency, content quality, and interaction with customers on social media on customer loyalty in a start-up business. West Science Business and Management, 2(02), 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaiwu, F., Newnes, L., Lattanzio, S., Kingdom, U., Kingdom, U., & Kingdom, U. (2024). Exploring social media metrics: A comprehensive literature review on assessing post-digitalisation outcomes in companies from a people-centric perspective. European Conference on Social Media, 11(1), 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoronkwo, C. E. (2024). Algorithmic bias in media content distribution and its influence on media consumption: Implications for diversity, equity, and Inclusion (Dei). International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Review, 7(05), 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. S., & Lee, B. Y. (2021). Social media influencer’s reputation: Developing and validating a multidimensional scale. Sustainability, 13(2), 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raborife, M., Ogbuokiri, B., & Aruleba, K. (2024). The role of social media in xenophobic attack in South Africa. Journal of the Digital Humanities Association of Southern Africa, 5(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, J., & Joseph, K. (2020). Theory in, theory out: The uses of social theory in machine learning for social science. Frontiers in Big Data, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, D., & Brandes, U. (2016). Re-conceptualizing centrality in social networks. European Journal of Applied Mathematics, 27(6), 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, H. (2025). Social media marketing research: A bibliometric analysis from Scopus. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Insider. (2025). Social media benchmarks for 2025. Social Insider. Available online: https://www.socialinsider.io/social-media-benchmarks (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Spiller, T. R., Levi, O., Neria, Y., Suarez-Jimenez, B., Bar-Haim, Y., & Lazarov, A. (2020). On the validity of the centrality hypothesis in cross-sectional between-subject networks of psychopathology. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J. L. (2023). Issue communication network dynamics in connective action: The role of non-political influencers and regular users. Social Media+ Society, 9(2), 20563051231177920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarisayi, K. S. (2024). Framing operation dudula and anti-immigrant sentiment in South African media discourse. Indonesian Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 3(1), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarisayi, K. S., & Manik, S. (2020). An unabating challenge: Media portrayal of xenophobia in South Africa. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1), 1859074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, Y., & Jungherr, A. (2020). Computational social science and the study of political communication. Political Communication, 38(1–2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Harst, J. P., & Angelopoulos, S. (2024). Less is more: Engagement with the content of social media influencers. Journal of Business Research, 181, 114746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wies, S., Bleier, A., & Edeling, A. (2023). Finding Goldilocks influencers: How follower count drives social media engagement. Journal of Marketing, 87(3), 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., Lü, L., Liu, J., & Mariani, M. S. (2024). Beyond network centrality: Individual-level behavioral traits for predicting information superspreaders in social media. National Science Review, 11(7), nwae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.-B., Li, Z.-H., & Zhuang, Y.-J. (2021). Identification of influencers in online social networks: Measuring influence considering multidimensional factors exploration. Heliyon, 7(4), e06472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |