Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. The Role of Fact-Checking in Modern Journalism

2.2. Academic Approaches to Disinformation Research

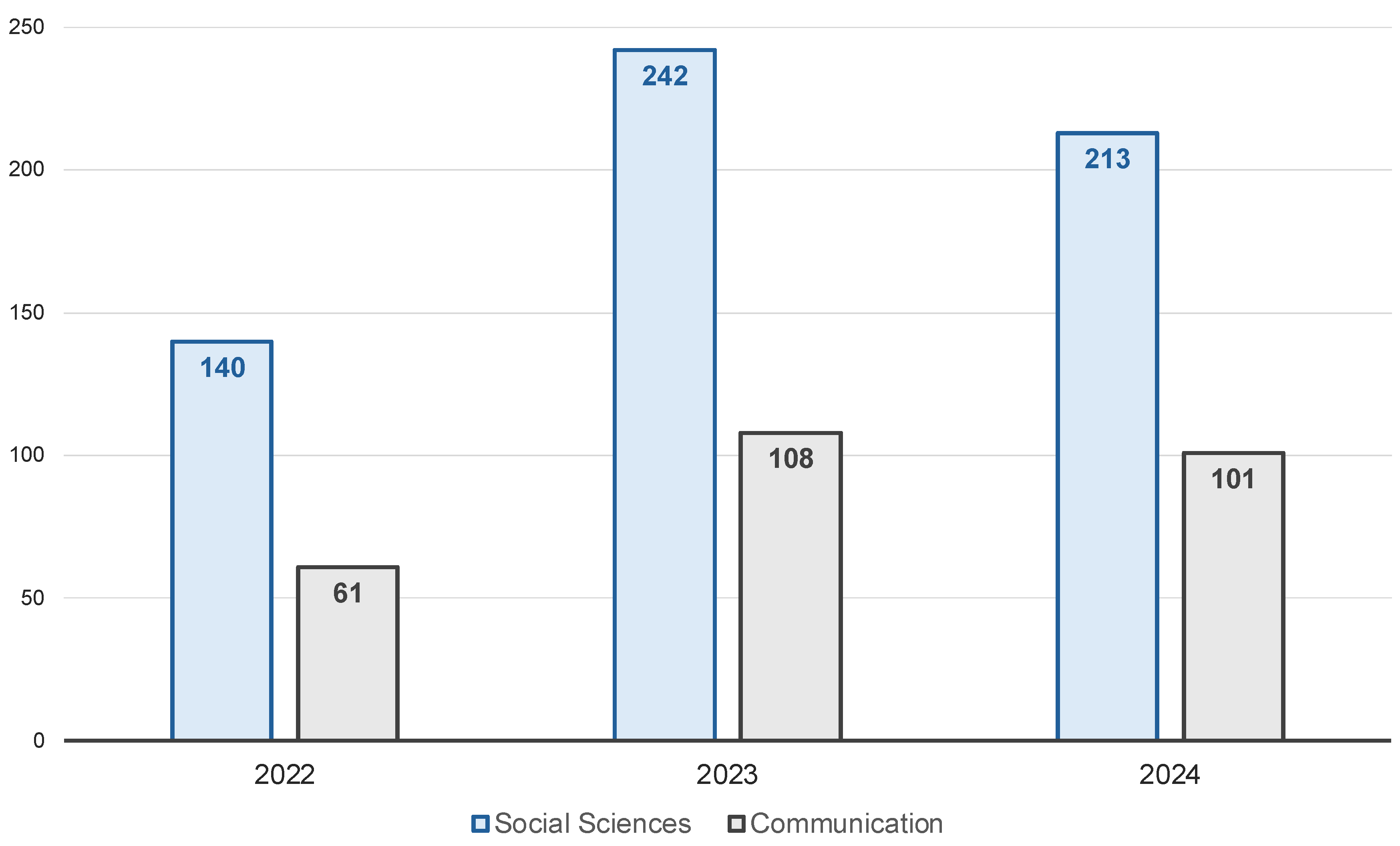

- RQ1: How has scientific production on fact-checking evolved during the analyzed period?

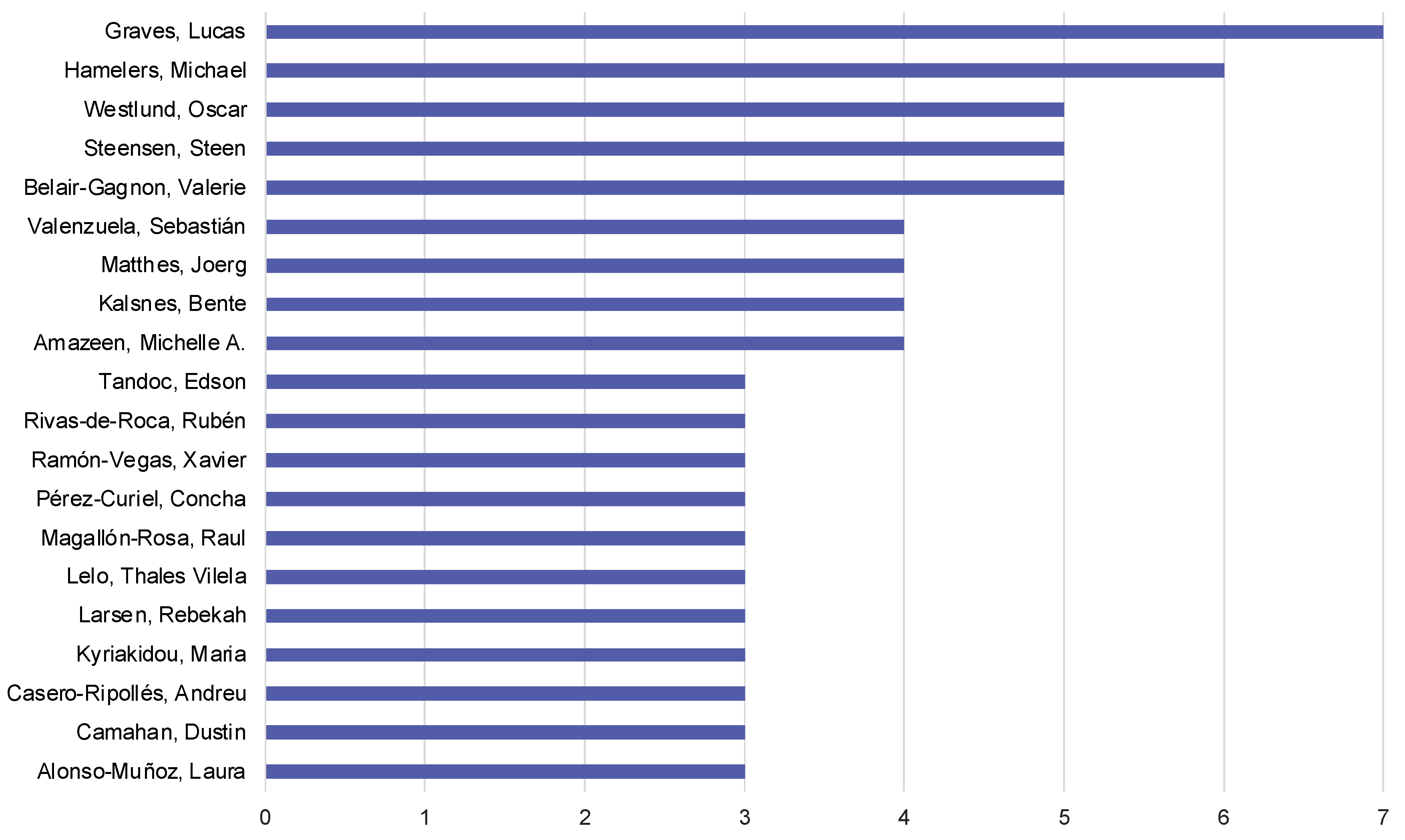

- RQ2: Who are the authors with the highest number of papers published on fact-checking during the analyzed period?

- RQ3: Which universities had a higher scientific production on fact-checking during the analyzed period?

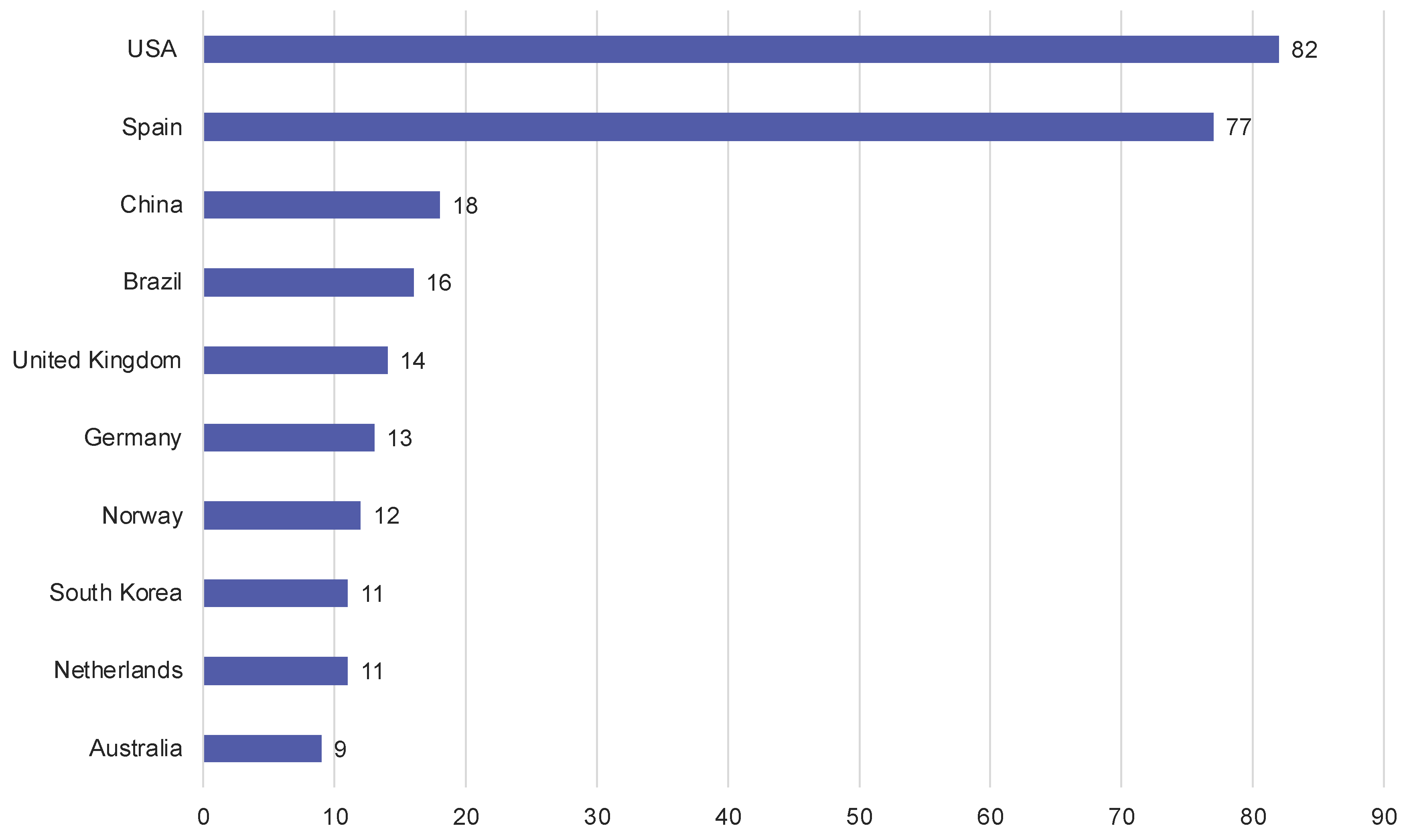

- RQ4: Which countries had a higher scientific production on fact-checking during the analyzed period?

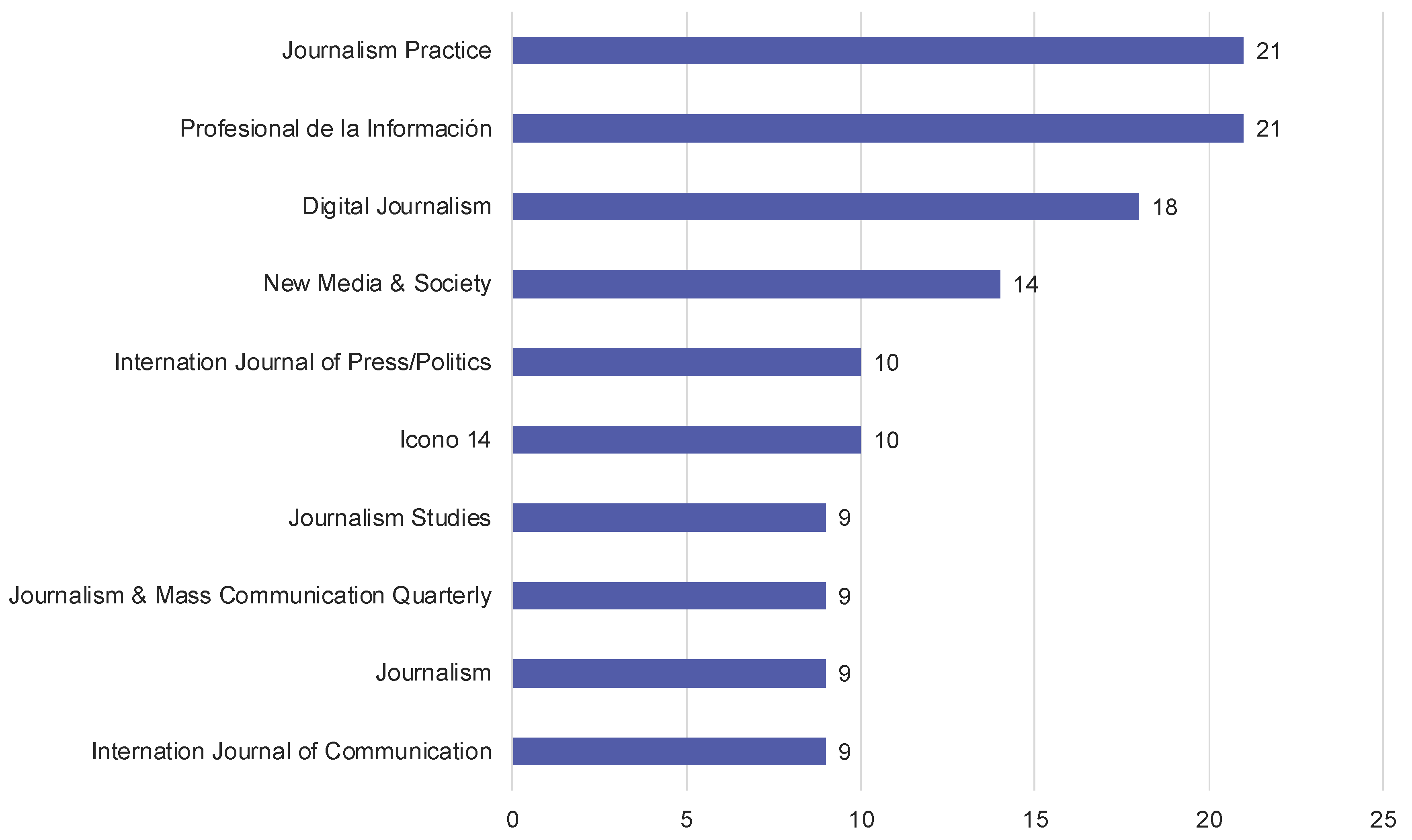

- RQ5: Which are the journals publishing most scientific articles on fact-checking during the analyzed period?

- RQ6: What are the most cited articles on fact-checking published during the analyzed period?

- RQ7: What are the most used keywords in the articles on fact-checking published during the analyzed period?

- RQ8: What are the main topics and methods used in the academic articles on fact-checking related to the Russia–Ukraine War published during the analyzed period?

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. General Approach to Social Sciences Production

4.2. Performance Analysis of Communication Papers

4.3. In-Depth Review of Fact-Checking Articles About the Russia-Ukraine War

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| References | Principle Goals | Methods and Materials | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charlton et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

| García-Marín et al. (2023) |

|

|

|

| Magallón-Rosa et al. (2023) |

|

|

|

| Morejón-Llamas et al. (2022) |

|

|

|

| Sacaluga-Rodríguez et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

| Springer et al. (2023) |

|

|

|

| Tulin et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

| Zecchinon and Standaert (2025) |

|

|

|

| 1 | Information retrieved from WOS. https://tinyurl.com/249c5s92, accessed on 28 November 2024. |

| 2 | Information retrieved from WOS. https://tinyurl.com/3d3uuxtx, accessed on 28 November 2024 |

References

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santos, C., Peixinho, A. T., Lopes, F., & Araújo, R. (2023). Fact-checks: La liquidez de un género. Un estudio de caso portugués en un contexto pandémico. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 29(2), 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazeen, M. A. (2020). Journalistic interventions: The structural factors affecting the global emergence of fact-checking. Journalism, 21(1), 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazeen, M. A., Krishna, A., & Eschmann, R. (2022). Cutting the Bunk: Comparing the Solo and Aggregate Effects of Prebunking and Debunking COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation. Science Communication, 44(4), 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce-García, S., Said-Hung, E., & Mottareale-Calvanese, D. (2022). Astroturfing as a strategy for manipulating public opinion on Twitter during the pandemic in Spain. Profesional de la Información, 31(3), e310310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, I., & Valenzuela, S. (2023). Studying the downstream effects of fact-checking on social media: Experiments on correction formats, belief accuracy and media trust. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinathan, S., & Chauchard, S. (2024). “I Don’t Think That’s True, Bro!” Social Corrections of Misinformation in India. International Journal of Press-Politics, 29(2), 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2022). Online disinformation on facebook: The spread of fake news during the portuguese 2019 election. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 30(2), 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. P., Gradim, A., Loureiro, M., & Ribeiro, F. (2023a). Fact-checking: Uma prática recente em Portugal? Análise da perceção da audiência. Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social “Disertaciones”, 16(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. P., Rivas-de-Roca, R., Gradim, A., & Loureiro, M. (2023b). The disinformation reaction to the russia–ukraine war: An analysis through the lens of iberian fact-checking. KOME—An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry, 11(2), 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G. (2018). Foreword. In C. Ireton, & J. Posetti (Eds.), Journalism, ‘fake news’ & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training (pp. 7–13). UNESCO Series on Journalism Education. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bigot, L. (2017). Le fact-checking ou la réinvention d’une pratique de vérification. Communication & Langages, 192(2), 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Herrero, D., Arcila-Calderón, C., & Tovar-Torrealba, M. (2024). Pandemia, politización y odio: Características de la desinformación en España. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 30(3), 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bran, R., Tiru, L., Grosseck, G., Holotescu, C., & Malita, L. (2021). Learning from each other: A bibliometric review of research on information disorders. Sustainability, 13(18), 10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, S., & Waller, L. (2023). Communities of practice in the production and resourcing of fact-checking. Journalism, 24(9), 1938–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A., Harrington, S., & Hurcombe, E. (2020). ‘Corona? 5G? or both?’: The dynamics of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theories on Facebook. Media International Australia, 177, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burel, G., & Alani, H. (2023). The fact-checking observatory: Reporting the co-spread of misinformation and fact-checks on social media. In 34th ACM conference on hypertext and social media (HT ’23) (pp. 1–3). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G., Paisana, M., & Pinto-Martinho, A. (2023). Digital news report portugal 2023. Obercom—Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2jtaa3hn (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Chan, J. (2024). Online astroturfing: A problem beyond disinformation. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 50(3), 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, T., Mayer, A.-T., & Ohme, J. (2024). A Common Effort: New Divisions of Labor Between Journalism and OSINT Communities on Digital Platforms. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 0(0), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culloty, E., & Suiter, J. (2021). Disinformation and manipulation in digital media: Information pathologies. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafonte-Gómez, A., Míguez-González, M., & Ramahí-García, D. (2022). Fact-checkers on social networks: Analysis of their presence and content distribution channels. Communication & Society, 35(3), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dame Adjin-Tettey, T. (2022). Combating fake news, disinformation, and misinformation: Experimental evidence for media literacy education. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 9(1), 2037229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N., & Sippitt, A. (2020). Researching fact checking: Present limitations and future opportunities. The Political Quarterly, 91, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Ruiz, C. (2023). Disinformation on digital media platforms: A market-shaping approach. New Media & Society, 14614448231207644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di-Domenico, G., Sit, J., Ishizaka, A., & Nunan, D. (2021). Fake news, social media and marketing: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research, 124, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierickx, L., & Lindén, C. (2024). Fact-checking the war in Ukraine, or when the screens have become battlefields. EDMO. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yjjd8svx (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Dierickx, L., Lindén, C. G., & Opdahl, A. L. (2023). Automated Fact-Checking to Support Professional Practices: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Communication, 17, 5170–5190. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/21071/4287 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durr-Missau, L. (2024). The role of social sciences in the study of misinformation: A bibliometric analysis of web of science and scopus publications (2017–2022). Tripodos, 56, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDMO. (n.d.). War in Ukraine. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4mv2zvhj (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- EDMO Task Force on Disinformation on the War in Ukraine. (n.d.). Available online: https://tinyurl.com/44yfzmek (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Commission. (2023). European Commission: Directorate-general for communication. Public opinion in the European Union—First results—Winter 2022–2023. European Commission. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2775/460956 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN). (2024). European fact-checking standards network (EFCSN). Available online: https://efcsn.com/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- European Fact-Checking Standards Network Transparency Centre. (2023). Transparency centre. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/34rjkrnt (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Feng, M., Tsang, N. L., & Lee, F. L. (2021). Fact-checking as mobilization and counter-mobilization: The case of the anti-extradition bill movement in Hong Kong. Journalism Studies, 22(10), 1358–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C., & Amaral, I. (2022). Media literacy and critical thinking: Evaluating the impact on combating misinformation. International Journal of Communication, 16, 4567–4585. [Google Scholar]

- Frau-Meigs, D. (2022). How disinformation reshaped the relationship between journalism and media and information literacy (mil): Old and new perspectives revisited. Digital Journalism, 10(5), 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, D., Bossetta, M., Wells, C., Lukito, J., Xia, Y., & Adams, K. (2020). Black trolls matter: Racial and ideological asymmetries in social media disinformation. Social Science Computer Review, 40, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A. M., Storey, V. C., & Wallace, L. (2023). A typology of disinformation intentionality and impact. Information Systems Journal, 34, 1324–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marín, D., Pérez-Serrano, M. J., & Santos-Díez, M. T. (2023). Youth, social networks, and political participation: A study on the influence of Instagram. Comunicar, 31(74), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2021). Investigación sobre desinformación en España. Análisis de tendencias temáticas a partir de una revisión sistematizada de la literatura. Fonseca Journal of Communication, 23, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2022). Viralizar la verdad. Factores predictivos del engagement en el contenido verificado en TikTok. Profesional de la Información, 31(2), e310210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2023). Disinformation and war. Verification of false images about the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Revista ICONO 14. Revista científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías emergentes, 21(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L., & Amazeen, M. (2019). Fact-checking as idea and practice in journalism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2twmrxz5 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Graves, L., Bélair-Gagnon, V., & Larsen, R. (2023). From public reason to public health: Professional implications of the “Debunking Turn” in the global fact-checking field. Digital Journalism, 12(10), 1417–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M. (2020). Separating truth from lies: Comparing the effects of news media literacy interventions and fact-checkers in response to political misinformation in the US and Netherlands. Information, Communication & Society, 25, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M. (2023). The (Un)Intended consequences of emphasizing the threats of mis- and disinformation. Media and Communication, 11(2), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Diz, P., Pérez-Escolar, M., & Aramburu, D. V. (2022). Fact-checking skills: A proposal for Communication studies. Revista de Comunicación, 21(1), 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberifier. (2024). Iberian digital media observatory. Available online: https://iberifier.eu/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- IFCN. (2024). About. IFCN code of principles. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2j69jksf (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Igartua, J. J., Ortega, F., & Arcila-Calderón, C. (2020). Communication use in the times of the coronavirus. A cross-cultural study. Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireton, C., & Posetti, J. (2018). Introduction. In C. Ireton, & J. Posetti (Eds.), Journalism, ’fake news’ & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training (pp. 14–31). UNESCO Series on Journalism Education. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. (2022). The roles of worry, social media information overload, and social media fatigue in hindering health Fact-checking. Social Media + Society, 8(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T. M., & Liu, J. (2019). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KaabOmeir, F., Khademizadeh, S., Seifadini, R., Balani, S. O., & Khazaneha, M. (2024). Overview of misinformation and disinformation research from 1971 to 2022. Journal of Scientometric Research, 13(2), 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, L., & Graves, L. (2024). How to grow a transnational field: A network analysis of the global fact-checking movement. New Media & Society, 15, 14614448241227856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelo, T. (2022). The rise of the Brazilian fact-checking movement: Between economic sustainability and editorial independence. Journalism Studies, 23(9), 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Ali, M. N. S., Rizal, A. R. B. A., & Xu, J. (2025). A bibliometric analysis of media convergence in the twenty-first century: Current status, hotspots, and trends. Studies in Media and Communication, 13(1), 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Lyu, W., & Salleh, S. M. (2023). Misinformation in communication studies: A review and bibliometric analysis. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 39(4), 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pan, F., & Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. (2020). El fact checking en España. Plataformas, prácticas y rasgos distintivos. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 26(3), 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., & Shen, C. (2023). Unpacking multimodal fact-checking: Features and engagement of fact-checking videos on Chinese TikTok (Douyin). Social Media + Society, 9(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Rosa, R., Fernández-Castrillo, C., & Garriga, M. (2023). Fact-checking in war: Types of hoaxes and trends from a year of disinformation in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Profesional de la Información, 32(5), e320520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzarlis, A. (2018). Fact-checking 101. In C. Ireton, & J. Posetti (Eds.), Journalism, ’fake news’ & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training (pp. 81–95). UNESCO Series on Journalism Education. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Mare, A., & Munoriyarwa, A. (2022). Guardians of truth? Fact-checking the ‘disinfodemic’ in Southern Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of African Media Studies, 14(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Costa, M., López-Pan, F., Buslón, N., & Salaverría, R. (2023). Nobody-fools-me perception: Influence of age and education on the overconfidence of spotting disinformation. Journalism Practice, 17(10), 2084–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W. K., Chung, M., & Jones-Jang, S. M. (2023). How can we fight partisan biases in the COVID-19 pandemic? AI source labels on fact-checking messages reduce motivated reasoning. Mass Communication and Society, 26(4), 646–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morejón-Llamas, N., Martín-Ramallal, P., & Micaletto-Belda, J. P. (2022). Twitter content curation as an antidote to hybrid warfare during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Profesional de la Información, 31(3), e310308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon-Vegas, X., & Mauri-Ríos, M. (2022). Bringing journalism back to its roots: Examining fact-checking practices, methods, and challenges in the Mediterranean context. Profesional de la Información, 31(2), e310215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon, X., & Rodríguez-Martínez, R. (2021). Fact-checking interventions as counteroffensives to disinformation growth: Standards, values, and practices in Latin America and Spain. Media and Communication, 9(1), 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sierra, N., Magro-Vela, S., & Vinader-Segura, R. (2024). Research on disinformation in academic studies: Perspectives through a bibliometric analysis. Publications, 12(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapenko, L., Vorontsova, A., Voronenko, I., Makarenko, I., & Kozmenko, S. (2023). Coverage of the Russian armed aggression against Ukraine in scientific works: Bibliometric analysis. Journal of International Studies, 16(3), 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S., & Ghosh, M. (2023). Bibliometric review of research on misinformation: Reflective analysis on the future of communication. Journal of Creative Communications, 18(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. (2024). Bibliometric analysis: The main steps. Encyclopedia, 4(2), 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Escolar, M., Lilleker, D., & Tapia-Frade, A. (2023). A systematic literature review of the phenomenon of disinformation and misinformation. Media and Communication, 11(2), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A. (2019). Accountability and media literacy mechanisms as a counteraction to disinformation in Europe. Journal of Digital Media & Policy, 10(3), 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, A. G., Barbosa, R. L., Segovia-García, N., & Franco, D. R. (2022). Disinformation in social networks and bots: Simulated scenarios of its spread from system dynamics. Systems, 10(2), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-de-Roca, R., & Pérez-Curiel, C. (2023). Global political leaders during the COVID-19 vaccination: Between propaganda and fact-checking. Politics and the Life Sciences, 42(1), 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ferrándiz, R. (2023). An overview of the fake news phenomenon: From untruth-driven to post-truth-driven approaches. Media and Communication, 11(2), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C. V., Paniagua-Rojano, F. J., & Magallón-Rosa, R. (2021). Debunking political disinformation through journalists’ perceptions: An analysis of colombia’s fact-checking news practices. Media and Communication, 9, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacaluga-Rodríguez, I., Vargas, J. J., & Sánchez, J. P. (2024). Exploring neurocommunicative confluence: Analysis of the interdependence between personality traits and information consumption patterns in the detection of fake news. A study with university students of journalism and communication using enneagrams. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (82), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, R., Buslón, N., López-Pan, F., León, B., López-Goñi, I., & Erviti, M. (2020). Disinformation in times of pandemic: Typology of hoaxes on COVID-19/Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: Tipología de los bulos sobre la COVID-19. Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e29031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, R., & Cardoso, G. (2023). Future of disinformation studies: Emerging research fields. Profesional de la Información, 32(5), e320525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Mata, B., Cortiñas-Rovira, S., & Herrero-Solana, V. (2023). La investigación en periodismo y COVID-19 en España: Mayor impacto académico en citas, aproximaciones metodológicas clásicas e importancia temática de la desinformación. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, A., Ioanăș, I., Delcea, C., Geantă, L.-M., & Cotfas, L.-A. (2024). Mapping the landscape of misinformation detection: A bibliometric approach. Information, 15(1), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sádaba, C., & Salaverría, R. (2023). Combatir la desinformación con alfabetización mediática: Análisis de las tendencias en la Unión Europea. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (81), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Â., Silva, J., & Ferreira, C. (2022). Digital journalism and the challenge of fake news: A study on verification practices. Journal of Media Studies, 34(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, N., Nygren, G., Orlova, D., Taradai, D., & Widholm, A. (2023). Sourcing dis/information: How Swedish and Ukrainian journalists source, verify, and mediate journalistic truth during the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Journalism Studies, 24(9), 1111–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, S., Belair-Gagnon, V., Graves, L., Kalsnes, B., & Westlund, O. (2022). Journalism and Source Criticism. Revised Approaches to Assessing Truth-Claims. Journalism Studies, 23(16), 2119–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, S., Kalsnes, B., & Westlund, O. (2024). The limits of live fact-checking: Epistemological consequences of introducing a breaking news logic to political fact-checking. New Media & Society, 26(11), 6347–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stencel, M., Ryan, E., & Luther, J. (2024). With half the planet going to the polls in 2024, fact-checking sputters. Available online: https://reporterslab.org/2024/05/30/with-half-the-planet-going-to-the-polls-in-2024-fact-checking-sputters/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Sun, Y. Q. (2022). Verification upon exposure to COVID-19 misinformation: Predictors, outcomes, and the mediating role of verification. Science Communication, 44(3), 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E. C., Jr., Lim, Z., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining ‘fake news’. A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tătaru, G.-C., Domenteanu, A., Delcea, C., Florescu, M. S., Orzan, M., & Cotfas, L. A. (2024). Navigating the disinformation maze: A bibliometric analysis of scholarly efforts. Information, 15(12), 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, S., Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., & Gracia-Villar, M. (2024). Unveiling the truth: A systematic review of fact-checking and fake news research in social sciences. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 14(2), e202427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traquina, N. (2002). O que é jornalismo. Quimera Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Tulin, M., Hameleers, M., de Vreese, C., Aalberg, T., Corbu, N., Van Erkel, P., Esser, F., Gehle, L., Halagiera, D., Hopmann, D. N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Mihelj, S., Schemer, C., Stetka, V., Strömbäck, J., Terren, L., & Theocharis, Y. (2024). Why do citizens choose to read fact-checks in the context of the russian war in ukraine? The role of directional and accuracy motivations in nineteen democracies. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 29, 19401612241233533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- #UkraineFacts. (2024). Available online: https://ukrainefacts.org/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Ukraine War Resource Hub, EU DisinfoLab. (2024). EU disinfoLab. Available online: https://www.disinfo.eu/ukraine-hub/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Valverde-Berrocoso, J., González-Fernández, A., & Acevedo-Borrega, J. (2022). Disinformation and multiliteracy: A systematic review of the literature. Comunicar, 70, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara, A., Amoedo, A., Moreno, E., Negredo, S., & Kaufmann, J. (2022). Digital news report españa 2022. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, C. J., Guo, L., & Amazeen, M. A. (2018). The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media & Society, 20(5), 2028–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinhas, O., & Bastos, M. (2022, November 2–5). When fact-checking is not WEIRD: Challenges in fact-checking beyond the western world. AoIR 2022: The 23rd Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers, Dublin, Ireland. Available online: http://spir.aoir.org (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H. T., Baines, A., & Nguyen, N. (2023). Fact-checking climate change: An analysis of claims and verification practices by fact-checkers in four countries. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 100(2), 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M., McNaughton, N., & Elliott, D. (2020). Journalistic integrity in the age of social media: A case study of the UK press. Digital Journalism, 8(5), 678–695. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, N., Cohen, J., Holbert, R. L., & Morag, Y. (2020). Fact-checking: A meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Political Communication, 37, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N., & Salovich, N. A. (2021). Unchecked vs. Uncheckable: How opinion-based claims can impede corrections of misinformation. Mass Communication and Society, 24, 500–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2018). Thinking about ‘information disorder’: Formats of misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information. In C. Ireton, & J. Posetti (Eds.), Journalism, ‘fake news’ & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training (pp. 43–54). UNESCO Series on Journalism Education. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wasike, B. (2023). You’ve been fact-checked! examining the effectiveness of social media fact-checking against the spread of misinformation. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 11, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X. Z. (2024). Let’s verify and rectify! Examining the nuanced influence of risk appraisal and norms in combatting misinformation. New Media & Society, 26(7), 3786–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. T., Payton, B., Sun, M. R., Jia, W. F., & Huang, G. X. (2023). Toward an integrated framework for misinformation and correction sharing: A systematic review across domains. New Media & Society, 25(8), 2241–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecchinon, E., & Standaert, O. (2024). Algorithmic transparency in news feeds: Implications for media pluralism. Journalism Studies, 25(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zecchinon, P., & Standaert, O. (2025). The war in ukraine through the prism of visual disinformation and the limits of specialized fact-checking. A case-study at le monde. Digital Journalism, 13(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y., Ding, X., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Zhang, J., Yao, C., Liu, T., & Qin, B. (2024). RU22Fact: Optimizing evidence for multilingual explainable fact-checking on russia-ukraine conflict. arXiv, arXiv:2403.16662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Citations | Complete References | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiang (2022) | Jiang, S. H. (2022). The Roles of Worry, Social Media Information Overload, and Social Media Fatigue in Hindering Health Fact-Checking. Social Media + Society, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221113070 | 34 |

| 2 | Amazeen et al. (2022) | Amazeen, M. A., Krishna, A., & Eschmann, R. (2022). Cutting the Bunk: Comparing the Solo and Aggregate Effects of Prebunking and Debunking COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation. Science Communication, 44(4), 387–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221111558 | 24 |

| 3 | García-Marín and Salvat-Martinrey (2022) | García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2022). Viralizing the truth: predictive factors of fact-checkers’ engagement on TikTok. Profesional de la Información, 31(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.mar.10 | 21 |

| 4 | Moon et al. (2023) | Moon, W. K., Chung, M., & Jones-Jang, S. M. (2023). How Can We Fight Partisan Biases in the COVID-19 Pandemic? AI Source Labels on Fact-checking Messages Reduce Motivated Reasoning. Mass Communication and Society, 26(4), 646–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2097926 | 17 |

| Morejón-Llamas et al. (2022) | Morejón-Llamas, N., Martín-Ramallal, P., & Micaletto-Belda, J. P. (2022). Twitter content curation as an antidote to hybrid warfare during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Profesional de la Información, 31(3). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.may.08 | ||

| Xiao (2024) | Xiao, X. Z. (2024). Let’s verify and rectify! Examining the nuanced influence of risk appraisal and norms in combatting misinformation. New Media & Society, 26(7), 3786–3809. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221104948 | ||

| 5 | Badrinathan and Chauchard (2024) | Badrinathan, S., & Chauchard, S. (2024). “I Don’t Think That’s True, Bro!” Social Corrections of Misinformation in India. International Journal of Press-Politics, 29(2), 394–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612231158770 | 16 |

| 6 | Brookes and Waller (2023) | Brookes, S., & Waller, L. (2023). Communities of practice in the production and resourcing of fact-checking. Journalism, 24(9), 1938–1958. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221078465 | 15 |

| Graves et al. (2023) | Graves, L., Bélair-Gagnon, V., & Larsen, R. (2023). From Public Reason to Public Health: Professional Implications of the “Debunking Turn” in the Global Fact-Checking Field. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2218454 | ||

| 7 | Lu and Shen (2023) | Lu, Y. D., & Shen, C. H. (2023). Unpacking Multimodal Fact-Checking: Features and Engagement of Fact-Checking Videos on Chinese TikTok (Douyin). Social Media + Society, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221150406 | 14 |

| Sun (2022) | Sun, Y. Q. (2022). Verification Upon Exposure to COVID-19 Misinformation: Predictors, Outcomes, and the Mediating Role of Verification. Science Communication, 44(3), 261–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221088927 | ||

| 8 | Bachmann and Valenzuela (2023) | Bachmann, I., & Valenzuela, S. (2023). Studying the Downstream Effects of Fact-Checking on Social Media: Experiments on Correction Formats, Belief Accuracy, and Media Trust. Social Media + Society, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231179694 | 13 |

| Hameleers (2023) | Hameleers, M. (2023). The (Un)Intended Consequences of Emphasizing the Threats of Mis- and Disinformation. Media and Communication, 11(2), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6301 | ||

| Mare and Munoriyarwa (2022) | Mare, A., & Munoriyarwa, A. (2022). Guardians of truth? Fact-checking the ‘disinfodemic’ in Southern Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of African Media Studies, 14(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams_00065_1 | ||

| Steensen et al. (2022) | Steensen, S., Belair-Gagnon, V., Graves, L., Kalsnes, B., & Westlund, O. (2022). Journalism and Source Criticism. Revised Approaches to Assessing Truth-Claims. Journalism Studies, 23(16), 2119–2137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2022.2140446 | ||

| Steensen et al. (2024) | Steensen, S., Kalsnes, B., & Westlund, O. (2024). The limits of live fact-checking: Epistemological consequences of introducing a breaking news logic to political fact-checking. New Media & Society, 26(11), 6347–6365. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231151436 | ||

| Yu et al. (2023) | Yu, W. T., Payton, B., Sun, M. R., Jia, W. F., & Huang, G. X. (2023). Toward an integrated framework for misinformation and correction sharing: A systematic review across domains. New Media & Society, 25(8), 2241–2267. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221116569 | ||

| 9 | Herrero-Diz et al. (2022) | Herrero-Diz, P., Pérez-Escolar, M., & Aramburu, D. V. (2022). Fact-checking skills: a proposal for Communication studies. Revista de Comunicación, 21(1), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC21.1-2022-A12 | 12 |

| Lelo (2022) | Lelo, T. (2022). The Rise of the Brazilian Fact-checking Movement: Between Economic Sustainability and Editorial Independence. Journalism Studies, 23(9), 1077–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2022.2069588 | ||

| Moreno-Gil et al. (2022) | Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon-Vegas, X., & Mauri-Ríos, M. (2022). Bringing journalism back to its roots: examining fact-checking practices, methods, and challenges in the Mediterranean context. Profesional de la Información, 31(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.mar.15 | ||

| Rodríguez-Ferrándiz (2023) | Rodríguez-Ferrándiz, R. (2023). An Overview of the Fake News Phenomenon: From Untruth-Driven to Post-Truth-Driven Approaches. Media and Communication, 11(2), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6315 | ||

| 10 | Dierickx et al. (2023) | Dierickx, L., Lindén, C. G., & Opdahl, A. L. (2023). Automated Fact-Checking to Support Professional Practices: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Communication, 17, 5170–5190. | 11 |

| Frau-Meigs (2022) | Frau-Meigs, D. (2022). How Disinformation Reshaped the Relationship between Journalism and Media and Information Literacy (MIL): Old and New Perspectives Revisited. Digital Journalism, 10(5), 912–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2081863 | ||

| Vu et al. (2023) | Vu, H. T., Baines, A., & Nguyen, N. (2023). Fact-checking Climate Change: An Analysis of Claims and Verification Practices by Fact-checkers in Four Countries. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 100(2), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990221138058 |

| Rank | Keywords | n | Rank | Keywords | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fact-Checking | 173 | 17 | Motivated Reasoning | 8 |

| 2 | Disinformation | 91 | Platforms | ||

| 3 | Misinformation | 90 | Post-Truth | ||

| 4 | Fake News | 66 | |||

| 5 | Social Media | 50 | 18 | Content Analysis | 7 |

| 6 | Journalism | 46 | Elections | ||

| 7 | COVID-19 | 41 | Engagement | ||

| 8 | Verification | 31 | Experiment | ||

| 9 | Artificial Intelligence | 25 | Media | ||

| 10 | Digital | 22 | 19 | Computational Methods | 6 |

| 11 | Media Literacy | 18 | Credibility | ||

| 12 | Correction | 13 | Ibero-America | ||

| Transparency | Journalism Practice | ||||

| 13 | Trust | 12 | 20 | Automated Fact-Checking | 5 |

| 14 | Health Communication | 11 | Climate Change | ||

| 15 | Europe | 10 | Comparative Research | ||

| Hoaxes | Interviews | ||||

| Spain | Partisanship | ||||

| 16 | Audiences | 9 | Perceived Credibility | ||

| Communication | Propaganda | ||||

| Infodemic | Survey | ||||

| 17 | Debunk | 8 |

| Citations | References |

|---|---|

| Charlton et al. (2024) | Charlton, T., Mayer, A.-T., & Ohme, J. (2024). A Common Effort: New Divisions of Labor Between Journalism and OSINT Communities on Digital Platforms. The International Journal of Press/Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612241271230 |

| García-Marín and Salvat-Martinrey (2023) | García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2023). Disinformation and war. Verification of false images about the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Icono 14. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v21i1.1943 |

| Magallón-Rosa et al. (2023) | Magallón-Rosa, R., Fernández-Castrillo, C., & Garriga, M. (2023). Fact-checking in war: Types of hoaxes and trends from a year of disinformation in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Profesional de la Información. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.sep.20 |

| Morejón-Llamas et al. (2022) | Morejón-Llamas, N., Martín-Ramallal, P., & Micaletto-Belda, J. P. (2022). Twitter content curation as an antidote to hybrid warfare during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Profesional de la Información. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.may.08 |

| Sacaluga-Rodríguez et al. (2024) | Sacaluga-Rodríguez, I., Vargas, J. J., & Sánchez, J. P. (2024). Exploring Neurocommunicative Confluence: Analysis of the Interdependence Between Personality Traits and Information Consumption Patterns in the Detection of Fake News. A Study with University Students of Journalism and Communication Using Enneagrams. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2281 |

| Springer et al. (2023) | Springer, N., Nygren, G., Orlova, D., Taradai, D., & Widholm, A. (2023). Sourcing Dis/Information: How Swedish and Ukrainian Journalists Source, Verify, and Mediate Journalistic Truth During the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict. Journalism Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2196586 |

| Tulin et al. (2024) | Tulin, M., Hameleers, M., de Vreese, C. et al. (2024). Why do Citizens Choose to Read Fact-Checks in the Context of the Russian War in Ukraine? The Role of Directional and Accuracy Motivations in Nineteen Democracies. The International Journal of Press/Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612241233533 |

| Zecchinon and Standaert (2025) | Zecchinon, P., & Standaert, O. (2025). The War in Ukraine Through the Prism of Visual Disinformation and the Limits of Specialized Fact-Checking. A Case-Study at Le Monde. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2024.2332609 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morais, R.; Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Blanco-Herrero, D. Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020048

Morais R, Piñeiro-Naval V, Blanco-Herrero D. Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020048

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorais, Ricardo, Valeriano Piñeiro-Naval, and David Blanco-Herrero. 2025. "Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020048

APA StyleMorais, R., Piñeiro-Naval, V., & Blanco-Herrero, D. (2025). Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020048