Abstract

Women have historically been underrepresented in politics. However, in the last few decades, more and more women have been elected to both upper and lower houses, particularly in Spain. Social media has become one >of the main channels for women to gain visibility, but the issue of unequal distribution of power and influence between men and women remains. This paper sheds light on gender differences among politicians on Twitter by analyzing the social media activity and influence of 277 of the 350 Members of the Spanish Congress of Deputies from March to June 2020. Our research shows there are still major gender differences regarding audience figures and amplification and that both male and female politicians still largely retweet more men than women. In addition, we found significant differences between parties and across the political spectrum, although these are less prominent (albeit not neutralized) in parties with a female leader. This is in keeping with studies that have found broad similarities between male and female politicians’ communicative practices, but a persistently large gap to be bridged in terms of their online influence. Female leaders are proposed as a means to bridge this gap.

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender Differences in Political Power and Influence, and Underrepresentation and Empowerment in Politics

Politics, like many other areas of human activity, has traditionally been male-dominated territory. Female representation in democratic parties, congresses, senates and powerful political offices has only increased in the last few decades (Elder 2020; Bridgewater and Nagel 2020). However, research has shown that the situation is still far from balanced. Although women have populated parties, local governments and parliaments, various studies have revealed that sexism in the culture of political parties tends to favor male candidates on the ballot, to systematically disempower women (Verge and Troupel 2011; Verge and de la Fuente 2014) and to hamper women’s access to powerful political offices (Lovenduski 2005; Verge 2010). According to Verge and Wiesehomeier (2019), such discrimination runs across all parties, and parity is still a long way off, even in the most representative democracies.

Spain is a particular case of a country in which women have been historically underrepresented in politics (Fernández and Eugenia 2008). In 1977, two years after dictator Francisco Franco’s death, the constituent legislature had 21 female Members (5.8% of the total). This number barely increased in the first legislature in 1979, in which a mere 24 out of 350 Members were women, none of whom held any significant office in government. By the terms of 1989 and 1993, the proportion of female Members in the Spanish Congress had reached a meagre 10%. However, in 1996, almost a hundred women (23.9%) were elected in the first People’s Party government. In 2007 a new Equality Law came into force, requiring political parties to ensure minimum gender representation of 40% in candidates running for office (Verge 2010). This helped to balance the male-dominated political culture (see Table 1) visible in Spanish politics since the transition to democracy (Valiente 2008; Verge 2012). Nevertheless, Verge and Wiesehomeier (2019) argue that discrimination did not suddenly disappear with the 2007 quota. Although quotas tend to balance gender representation, other barriers to women in the political sphere, such as having to conform to male norms (Verge and de la Fuente 2014, p. 71), cause many women to relinquish certain offices (Verge 2015). Notwithstanding the ongoing inequality in Spanish politics, the number of elected women has increased in the last decade, and Spain now ranks sixteenth in the world in terms of women’s representation in parliament (Verge and Wiesehomeier 2019).

Table 1.

Percentage of women in Spanish Congress in 2019 per party *.

The aim of this research is to analyze gender differences in Twitter use among Spanish members of parliament. To do so, we gathered all tweets from 277 of the 350 Members of the Spanish Congress from March to June 2020. We measured four variables related to their overall Twitter use: number of tweets, mean number of followers (audience), number of retweets (amplification), and efficacy. In addition, we measured the number of times that Members were retweeted by fellow party members (internal amplification), which can be linked to the internal communication strategies of the parties analyzed.

1.2. Communicating for Influence and Visibility

One way that women can increase their visibility in society is to garner media coverage. Representation in the media allows women to normalize their role in politics while also allowing for an impact on the political agenda (Kreiss 2016) as well as to articulate policy positions (Sobieraj et al. 2020). However, the media have traditionally under- or misrepresented women (Wasburn and Wasburn 2011; Sánchez Calero et al. 2013; Lünenborg and Maier 2015; Larson 2001; Fernández García 2013; Guerrero-Solé 2018; Dunaway et al. 2013). Currently, social networks are at the heart of all political communications strategies (Usher et al. 2018). Politicians the world over utilize social media, not only during electoral campaigns, but also for everyday communications (Graham et al. 2016). Politicians’ use of social media is a strategic form of publicity (Kreiss 2016; Cervi and Roca 2017; Casero-Ripollés et al. 2020; Guerrero-Solé and Lluís 2017; Guerrero-Solé and López-González 2019). As a consequence, politicians’ influence is no longer estimated exclusively on the basis of their coverage in traditional media, but also on their popularity on social networks, where follower numbers, shares, retweets and likes are the measure of their success. Politicians’ activity on social networks is also considered to be a driver for media attention (Rauchfleisch and Metag 2020; Graham et al. 2016). Social media activity is therefore a priority for female politicians, particularly given that research has shown they receive less media attention (Miller and Peake 2013; Baitinger 2015; Tromble and Koole 2020) and more negative coverage (Armstrong and Gao 2011; Ross et al. 2013; Larson 2001) than their male counterparts. McGregor and Mourão (2016) hold that women are more central to the conversation about them and about their opponents than men; this indicates that their connections in social networks are stronger. Various studies suggest that women having more visibility on social networks and communicating directly with citizens (Loiseau and Nowacka 2015; Vergeer 2015) can help to redress this.

1.3. The Role of Gender and Party on Twitter

Twitter has become one of the main tools that politicians use to complement their traditional communication strategies (Jungherr and Schoen 2013; Vergeer et al. 2013; Jungherr 2014). But what role does gender play in female politicians’ activity and influence on Twitter? Gender research into social media focuses mainly on two areas: harassment of women on social networks and the differing topics that men and women talk about. With regard to the former, the results to date are inconclusive and culture-specific. Some researchers have concluded that female politicians face more negativity on social media than traditional media (Conroy et al. 2015) and are more likely to be the target of hate speech (Wilhelm and Joeckel 2018) or uncivil tweets questioning their positions as politicians (Southern and Harmer 2019). On the other hand, Tromble and Koole (2020) found that in the UK, US and the Netherlands, gendered insults are infrequent. In relation to the second area, past research has found that female politicians tend to talk more about issues that predominantly affect women (Pearson and Dancey 2011). Moreover, although there are only minor gender differences in communication styles in some cases (Hrbková and Macková 2020), in general gender and party have an effect on what women tweet about (Hemphill et al. 2020; Johnstonbaugh 2020; Evans and Clark 2016).

In addition to harassment and styles of communication, research has also been carried out on the following: the gendered distribution of relational power in network discussions (McGregor and Mourão 2016); different patterns of liking practices; support of issues and civic engagement (Brandtzaeg 2017); self-presentation on social networks (Cook 2016); gender stereotypes of politicians online (Beltran et al. 2020; Wagner et al. 2017).

However, few studies have focused on gender and party differences in politicians’ number of tweets, size of audience, amplification and efficacy. We believe that this analysis can offer significant insight into the extent to which Twitter evens out any such hypothetical differences between men and women. Consequently, our first research question is as follows:

- RQ1: Are there gender differences among Spanish Members with regard to number of tweets, audience, amplification and efficacy on Twitter?

As we have already mentioned, gender is not the only variable that might explain differences between politicians. Party membership can also be a predictor of politicians’ activity and influence in online environments (Johnstonbaugh 2020).

Therefore, the second research question is

- RQ2: Are there party differences among Spanish Members with regard to number of tweets, audience, amplification and efficacy on Twitter? Are there differences between left- and right-wing parties?

In Spain, left-wing parties have strived to achieve gender equality (Uribe Otalora 2013). Therefore, male–female internal amplification can be a measure of how much attention fellow Members pay their female and male colleagues and whether they are equally likely to retweet them. Thus, the third research question is

- RQ3: Is the amplification rate among female and male Spanish Members balanced?

2. Sample and Method

To answer the aforementioned research questions, we gathered all tweets, replies and retweets that Spanish Members posted on Twitter from 14 March to 19 June 2020. This period coincides with the COVID-19 state of alarm in Spain. The sample included 277 out of the 350 Members of the fourteenth legislature, of whom 44% were women and 56% men, from the parties shown in Table 2. They collectively posted 249,874 tweets and retweets in the three months, with an individual minimum of 2 and maximum of 7767 posts.

Table 2.

Breakdown of Spanish Members by party.

2.1. Independent Variables

We coded for the following independent variables:

- Gender: gender of the Member (male = 151, female = 126).

- Political party: political party of the Member (see Table 1).

- Political leaning: political leaning (left or right) of the Member’s party (left = 135, right = 121, independent = 21).

2.2. Dependent Variables

The dependent variables were defined as follows:

- Amount: number of tweets and replies that each Member posted in the period analyzed (min = 0; max = 3045; mean = 259; SD = 341).

- Amplification: number of times each Member was retweeted during the period (min = 0; max = 1,427,478; mean = 38,412; SD = 128,870).

- Audience: mean number of each Member’s followers during the period (min = 137; max = 1,351,574; mean = 38,270; SD = 136,211).

- Efficacy: defined as amplification divided by amount and audience (min = 0; max = 209.55; mean = 6.86; SD = 14.06).

- Internal amplification: proportion of retweets by fellow Members from the same party.

3. Results

To answer research question one, we first calculated the mean values of the dependent variables: amount, amplification, audience and efficacy. Table 3 shows the mean values by gender of these variables. We performed ANOVA tests to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between genders.

Table 3.

Mean values of amount of tweets, number of followers and efficacy of Spanish Members on Twitter by gender.

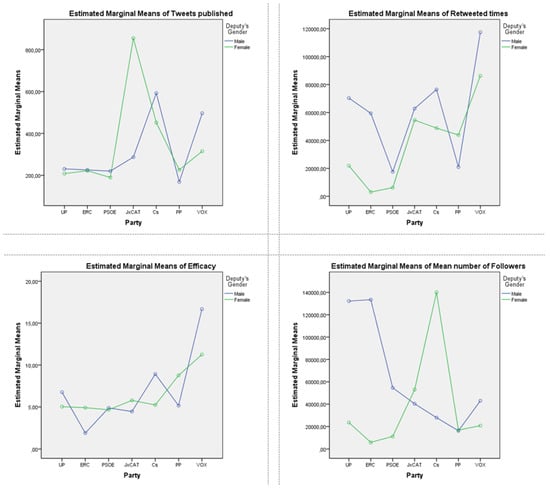

To answer research question two, we calculated the mean values of the dependent variables for each of the seven main parties in the Spanish Congress of Deputies. First, we analyzed the differences in tweet amount, amplification, efficacy and audience (Table 4). As above, we performed ANOVA tests for statistical differences. The results are also shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Mean amount, amplification, efficacy and audience of Spanish Members by gender and party.

Figure 1.

Mean amount, amplification, efficacy and audience of Spanish Members by gender and party.

The second part of RQ2 aimed to ascertain differences between left- and right-wing parties in Spain. For this purpose, we labelled UP and PSOE Members as ‘left-wing’ and Cs, PP and Vox Members as ‘right-wing’. We calculated the mean scores of the dependent variables: amount, amplification, audience and efficacy (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean amount, amplification, audience and efficacy by political spectrum (left/right).

Whereas the first two questions were related to the general Twitter activity of the Spanish Members, and amplification was defined as how many times they were retweeted overall, RQ3 explored how often Members retweeted posts published by fellow party Members (internal amplification). Table 6 below shows the gender breakdown of intra-party retweets.

Table 6.

Mean internal amplification of women and men, standard deviation, and significance by gender of the retweeter.

As Table 7 shows, male politicians retweet other male politicians twice as much as they retweet female politicians. Furthermore, female politicians also retweet male politicians more frequently, although the difference is slightly smaller.

Table 7.

Internal amplification (IA) among Spanish Members by party.

We performed a detailed analysis of the internal amplification strategies of men and women by party and gender (Table 8) and found that, in all cases, both men and women retweeted more tweets from men than from women. We performed a t-Test for paired samples and found that in the ruling party PSOE, the right-wing PP, and the far-right party Vox, the gender differences were highly significant.

Table 8.

Internal amplification (IA) of women and men by party and gender.

4. Discussion

Research has shown that women have historically been discriminated against in politics. Unequal distribution of political positions and responsibilities coupled with women’s underrepresentation in parliaments have driven the need for gender quotas (Verge 2010; Verge and de la Fuente 2014). This has resulted in significantly more women in parties and governments than in the past. However, parity is still a long way off, particularly due to the underlying androcentric political culture in some countries. Spain has been no exception when it comes to a gender imbalance in politics, and women have achieved increased visibility and power only in the last decade. The media have often spearheaded this shift, and today social media is one way that enables women to increase their presence, power and visibility. However, the issue of equality remains.

Our research analyzed the extent to which male and female Members of the Spanish Congress are equally influential in terms of content amount, amplification, audience and efficacy on Twitter, one of the most widely used social networks for political communications in Spain. The results show that there are few overall gender differences when it comes to number of tweets. We found that male and female Members are equally active on Twitter, which is in tune with the reported increase in women’s visibility on social networks (Loiseau and Nowacka 2015; Vergeer 2015). Our results also echo previous studies that have found minor differences in candidate online campaigning coverage (Tromble and Koole 2020) and reveal Spanish female politicians’ effort to be as active and influential on social networks as men. However, we found major disparities in the amplification of tweets (men are retweeted twice as many times as women) and audience (men have more than double the audiences of women). Nevertheless, most of these differences were not statistically significant due to the skewed distribution of variables (see Table A1 in Appendix A for the scores of variables for each Member).

When we broke down the analysis by party, the only considerable gender difference in amount of tweets was in the female-led Catalan party JxCat (women tweeted three times more than men) and the populist far-right party Vox (men tweeted twice as much as women). With regard to the other variables analyzed, we found that gender differences in amplification were notable, in particular in UP and ERC. In all parties except the right-wing PP, women were less amplified on the network than men. These results are in tune with previous research on the interaction of party and gender stereotypes on politicians’ effectiveness when they use Twitter (Holman et al. 2011). There were also stark differences in audience in the female-led party Cs. Finally, we found statistically significant differences between men and women in efficacy in ERC and UP. While the UP male Members’ efficacy was significantly greater than the women’s, in ERC, women had almost three times the efficacy of their male counterparts. The case of UP is significant because it defines itself as a feminist party and has clearly feminist policies. However, as the overall results show, women remain a minority in the male-dominated political sphere.

Statistically significant differences emerged when we grouped parties by ideological leaning. The right-wing parties Cs, PP and Vox were far more active than left-wing parties UP and PSOE. The same was true of amplification and efficacy, although the differences were lesser (p < 0.05). Amplification in right-wing parties was three times greater than in left-wing parties; efficacy was twice as high, and mean audience was almost half. In short, the right-wing parties, currently in the opposition, were far more active, had a greater impact on the network, and were much more efficient than the ruling left-wing parties. These results suggest that party and ideological leaning are better predictors of differences than gender in content amount, amplification and efficacy.

However, the most relevant and interesting results of this research are for internal amplification according to political party. We found that in all seven parties analyzed, internal amplification of men was substantially larger (broadly double) than of their female counterparts. Moreover, in five parties this difference was statistically significant. Earlier research found a sexist and discriminatory culture in most parties that favors male candidates on ballots, systematically disempowers women (Verge and Troupel 2011; Verge and de la Fuente 2014) and hampers women’s access to relevant political positions (Lovenduski 2005; Verge 2010). It is interesting to note that the two parties in which gender differences in internal amplification were not statistically significant (JxCat and Cs) were both led by a woman. It is therefore possible to conclude that having a female leader, i.e., allowing women to access relevant political positions, may balance out differences in internal amplification.

The results are similar when we look at internal amplification by gender. Women internally amplify more men than women, although the differences are only statistically significant in the ruling party PSOE and the far-right party Vox. Men also retweet more male than female fellow party members. Again, all of the differences observed are significant except for JxCat and Cs, the two parties in the Spanish Congress of Deputies with female leaders. We can therefore conclude that women are broadly discriminated against in the internal communications strategies of political parties in Spain on Twitter, especially in the case of women who are discriminated against by male party colleagues. This discrimination is not related to the party’s position on the political spectrum and is only neutralized in female-led parties. These results confirm previous findings that show that Twitter is far from being a public sphere in which gender inequalities are eliminated (Hu and Kearney 2020).

Finally, it is worth mentioning that this research was performed with a sample of tweets collected during the first COVID-19 state of alarm in Spain. There is evidence that contexts with heightened states of national security threat—and the COVID-19 outbreak may be considered such a case—can activate preferences for male politicians (Holman et al. 2011). Consequently, new research is needed in the future to support and generalize the conclusions of our work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.G.-S. and C.P.-G.; Data curation: F.G.-S.; Investigation: F.G.-S.; Methodology: F.G.-S. and C.P.-G.; Supervision: C.P.-G.; Validation: F.G.-S. and C.P.-G.; Writing—original draft: F.G.-S.; Writing—review & editing: F.G.-S. and C.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE under Grant PGC2018-097352-A-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Twitter data of the 277 Spanish Members in the sample.

Table A1.

Twitter data of the 277 Spanish Members in the sample.

| Gender | Party | Twitter Handle | Followers | Activity | Retweets | RT Times |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Cs | inesarrimadas | 638,783 | 476 | 249 | 168,040 |

| F | Cs | mariadelamiel | 45,465 | 1071 | 163 | 49,758 |

| F | Cs | martamartirio | 10,242 | 2672 | 1947 | 16,115 |

| F | Cs | mcmartinez_cs | 1094 | 521 | 288 | 3259 |

| F | Cs | saragimnez | 4733 | 284 | 118 | 6958 |

| M | Cs | baledmundo | 28,279 | 802 | 623 | 74,017 |

| M | Cs | guillermodiazcs | 15,015 | 2790 | 1391 | 65,040 |

| M | Cs | marcosdequinto | 62,087 | 515 | 71 | 138,377 |

| M | Cs | paucambronerocs | 6333 | 2281 | 1933 | 28,526 |

| F | ERC | bassamontse | 11,445 | 168 | 85 | 8286 |

| F | ERC | caroltelechea | 2606 | 59 | 32 | 531 |

| F | ERC | inesgranollers | 987 | 1498 | 1202 | 2065 |

| F | ERC | martarosiq | 16,775 | 311 | 184 | 4390 |

| F | ERC | normapujol | 2373 | 433 | 365 | 400 |

| F | ERC | pilarvallugera | 1044 | 369 | 322 | 265 |

| F | ERC | _maria_dantas_ | 5346 | 4710 | 3806 | 5344 |

| M | ERC | capdevilajoan | 8306 | 1528 | 1398 | 1668 |

| M | ERC | gabrielrufian | 754,249 | 1334 | 1145 | 343,089 |

| M | ERC | joanmargall | 4346 | 1420 | 1151 | 3225 |

| M | ERC | jsalvadorduch | 7109 | 432 | 304 | 1538 |

| M | ERC | nuet | 23,466 | 2612 | 2124 | 5654 |

| M | ERC | xavieritja | 3555 | 914 | 763 | 1302 |

| F | JxCAT | conceptermens | 939 | 370 | 314 | 694 |

| F | JxCAT | lauraborras | 114,448 | 7033 | 3988 | 154,404 |

| F | JxCAT | marionaid | 1105 | 742 | 648 | 684 |

| F | JxCAT | miriamnoguerasm | 95,328 | 1587 | 1363 | 62,417 |

| M | JxCAT | ferran_bel | 7698 | 875 | 515 | 6943 |

| M | JxCAT | genisboadella | 2498 | 416 | 326 | 1859 |

| M | JxCAT | jacs_jaumeacs | 144,823 | 823 | 293 | 238,307 |

| M | JxCAT | sergimiquel | 6365 | 293 | 125 | 4221 |

| F | PP | abeltran_ana | 8121 | 374 | 204 | 29,416 |

| F | PP | aliciagarcia_av | 4603 | 1141 | 716 | 10,699 |

| F | PP | anadebande | 12,228 | 4131 | 3196 | 59,218 |

| F | PP | anapastorjulian | 106,286 | 730 | 417 | 133,732 |

| F | PP | anazurita7 | 3449 | 645 | 519 | 3584 |

| F | PP | auxipd | 1462 | 180 | 180 | 0 |

| F | PP | bealinuesa | 1553 | 336 | 160 | 454 |

| F | PP | bea_fanjul | 59,436 | 735 | 306 | 580,147 |

| F | PP | belenhoyo | 11,017 | 593 | 419 | 4462 |

| F | PP | borrego_corte | 1679 | 923 | 914 | 143 |

| F | PP | carmenriolobos | 6262 | 3721 | 3029 | 3534 |

| F | PP | carolinaespanar | 3192 | 449 | 440 | 96 |

| F | PP | cayetanaat | 212,899 | 319 | 163 | 389,637 |

| F | PP | cnlacoba | 1901 | 223 | 140 | 547 |

| F | PP | cucagamarra | 10,328 | 595 | 362 | 14,384 |

| F | PP | edurneuriarte | 21,967 | 213 | 24 | 62,997 |

| F | PP | llanosdeluna | 673 | 202 | 182 | 494 |

| F | PP | margaprohens | 5743 | 3211 | 2643 | 10,416 |

| F | PP | mariaramallov | 433 | 51 | 30 | 17 |

| F | PP | martaglezvzqz | 7841 | 32 | 21 | 374 |

| F | PP | mdelaoredondo | 284 | 160 | 154 | 15 |

| F | PP | milamarcos | 2033 | 1304 | 1051 | 951 |

| F | PP | moromjesus | 3796 | 2463 | 2249 | 2118 |

| F | PP | palomagazquez | 2098 | 4816 | 4768 | 3307 |

| F | PP | pilarmarcosd | 4660 | 2505 | 2076 | 8433 |

| F | PP | rosaromerocr | 9571 | 988 | 278 | 13,764 |

| F | PP | solcruzguzman | 2145 | 683 | 475 | 1310 |

| F | PP | tejerinapp | 2180 | 32 | 32 | 0 |

| F | PP | teresajbecerril | 6645 | 324 | 119 | 20,190 |

| F | PP | tristanamg | 2593 | 414 | 407 | 109 |

| F | PP | valentinam | 3227 | 317 | 125 | 6975 |

| M | PP | aalmodobar | 4093 | 1393 | 642 | 4131 |

| M | PP | aglezterol | 19,432 | 431 | 160 | 35,821 |

| M | PP | albertocasero | 2147 | 1294 | 1173 | 715 |

| M | PP | andreslorite | 3822 | 832 | 495 | 10,697 |

| M | PP | carlosrojas_ppa | 5440 | 1321 | 1233 | 3064 |

| M | PP | celsodelgadoou | 1240 | 141 | 126 | 28 |

| M | PP | diegogagob | 7556 | 434 | 341 | 3219 |

| M | PP | diegomovellan | 1621 | 696 | 639 | 1481 |

| M | PP | educarazo | 2967 | 628 | 353 | 2445 |

| M | PP | eloysuarezl | 4786 | 451 | 149 | 2669 |

| M | PP | gmariscalanaya | 6065 | 439 | 412 | 1075 |

| M | PP | herrerobono | 4830 | 171 | 36 | 826 |

| M | PP | hispanpablo | 855 | 27 | 14 | 164 |

| M | PP | jacallejascano | 629 | 307 | 136 | 558 |

| M | PP | jaimedeolano | 13,456 | 2682 | 2317 | 30,005 |

| M | PP | jangelvillalon | 2032 | 283 | 207 | 569 |

| M | PP | javierbasco | 332 | 236 | 231 | 0 |

| M | PP | javier_merino | 2463 | 397 | 259 | 638 |

| M | PP | jiechaniz | 3146 | 574 | 118 | 27,000 |

| M | PP | josemiguel_glez | 379 | 68 | 64 | 4 |

| M | PP | jspostigo | 656 | 430 | 403 | 31 |

| M | PP | juan_pedreno | 175 | 42 | 22 | 5 |

| M | PP | luisstamaria | 4174 | 339 | 273 | 509 |

| M | PP | mapaniagua | 4532 | 189 | 83 | 1300 |

| M | PP | mariogarcessan | 4339 | 172 | 50 | 7477 |

| M | PP | mcastellonpp | 1523 | 346 | 232 | 243 |

| M | PP | miqueljerez | 1617 | 656 | 607 | 651 |

| M | PP | montesinospablo | 40,420 | 537 | 357 | 21,305 |

| M | PP | oscarclavell | 2905 | 48 | 32 | 211 |

| M | PP | oscargamazo | 1702 | 1528 | 1174 | 679 |

| M | PP | otazu35 | 696 | 1097 | 937 | 1533 |

| M | PP | pablocasado_ | 423,738 | 760 | 292 | 562,173 |

| M | PP | pedronavarrol | 2299 | 1686 | 1306 | 1492 |

| M | PP | quin1954 | 2382 | 82 | 66 | 212 |

| M | PP | sanchezcesar | 8575 | 155 | 83 | 748 |

| M | PP | sebastianlede15 | 691 | 1146 | 1055 | 119 |

| M | PP | tcabcas | 1080 | 635 | 561 | 689 |

| M | PP | teogarciaegea | 61,518 | 434 | 214 | 123,982 |

| M | PP | vicentebetoret | 5399 | 627 | 478 | 2953 |

| M | PP | vicentetiradopp | 1548 | 6470 | 6360 | 1083 |

| M | PP | vicpiriz1975 | 5527 | 876 | 443 | 7693 |

| F | PSOE | adrilastra | 81,460 | 566 | 465 | 107,381 |

| F | PSOE | afernb | 12,972 | 924 | 344 | 25,213 |

| F | PSOE | anaprietonieto | 8163 | 3753 | 2895 | 8084 |

| F | PSOE | angelesmarra | 959 | 536 | 301 | 251 |

| F | PSOE | ariagonagp | 522 | 22 | 14 | 4 |

| F | PSOE | beamcarrillo | 2611 | 413 | 299 | 821 |

| F | PSOE | beatrizcorredor | 13,269 | 967 | 820 | 1172 |

| F | PSOE | begonasarre | 2332 | 882 | 574 | 755 |

| F | PSOE | belenfcasero | 1775 | 701 | 631 | 1278 |

| F | PSOE | belitagl | 760 | 854 | 796 | 289 |

| F | PSOE | caballerohelena | 577 | 1537 | 1144 | 363 |

| F | PSOE | carmenandres_ | 3912 | 323 | 267 | 346 |

| F | PSOE | carmencalvo_ | 66,863 | 325 | 272 | 17,196 |

| F | PSOE | celaaisabel | 35,923 | 144 | 33 | 16,063 |

| F | PSOE | elviraramon | 3471 | 2365 | 2109 | 1612 |

| F | PSOE | estherpadillar | 3271 | 571 | 454 | 796 |

| F | PSOE | estherpcamarero | 4015 | 303 | 170 | 866 |

| F | PSOE | evabravobarco | 731 | 85 | 33 | 406 |

| F | PSOE | evapatriciab | 649 | 92 | 51 | 220 |

| F | PSOE | fuensantalima | 2667 | 1588 | 1093 | 957 |

| F | PSOE | graciacanales3 | 563 | 182 | 114 | 62 |

| F | PSOE | hernanzsofia | 4698 | 397 | 360 | 452 |

| F | PSOE | lauraberja86 | 3240 | 1238 | 1030 | 4283 |

| F | PSOE | lidiaguinart | 4626 | 1037 | 634 | 4492 |

| F | PSOE | luisacarcedo | 10,310 | 87 | 53 | 5028 |

| F | PSOE | luzseijo | 7184 | 357 | 178 | 7110 |

| F | PSOE | maraluisavilch1 | 180 | 294 | 277 | 16 |

| F | PSOE | marina_ortega_ | 1140 | 585 | 366 | 4564 |

| F | PSOE | maritxu30 | 1810 | 121 | 14 | 513 |

| F | PSOE | marotoreyes | 13,933 | 556 | 388 | 7636 |

| F | PSOE | marrodanmaria | 816 | 5 | 4 | 34 |

| F | PSOE | merceperea | 5605 | 2028 | 1498 | 4281 |

| F | PSOE | meritxell_batet | 49,523 | 583 | 243 | 11,290 |

| F | PSOE | mjmonteroc | 41,120 | 11 | 3 | 1311 |

| F | PSOE | montseminguez | 4019 | 609 | 475 | 1025 |

| F | PSOE | msolsj | 2866 | 2007 | 1677 | 2099 |

| F | PSOE | mvalerio_gu | 21,199 | 791 | 764 | 2414 |

| F | PSOE | nvillagrasa | 1284 | 304 | 188 | 346 |

| F | PSOE | olgaalonso62 | 155 | 551 | 398 | 74 |

| F | PSOE | patri_blanquer | 1644 | 333 | 254 | 1161 |

| F | PSOE | pilicancela | 6243 | 1346 | 673 | 8824 |

| F | PSOE | rafi_crespin | 2827 | 141 | 76 | 207 |

| F | PSOE | sandrage76 | 1028 | 2397 | 2183 | 827 |

| F | PSOE | soniafetesoro | 2786 | 53 | 20 | 41 |

| F | PSOE | ssumelzo | 21,687 | 441 | 398 | 1222 |

| F | PSOE | susana_ros | 6386 | 528 | 435 | 1685 |

| F | PSOE | tamarayar | 1846 | 309 | 293 | 91 |

| F | PSOE | teresaribera | 44,329 | 432 | 229 | 11,675 |

| F | PSOE | zaidacantera | 35,318 | 1923 | 1303 | 36,460 |

| M | PSOE | abalosmeco | 70,836 | 403 | 185 | 61,864 |

| M | PSOE | alejandrosolerm | 3412 | 798 | 208 | 1939 |

| M | PSOE | alfonsocendon | 2726 | 1470 | 812 | 7486 |

| M | PSOE | antidiofagundez | 254 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| M | PSOE | apabellas | 163 | 11 | 8 | 0 |

| M | PSOE | arandapaco | 3521 | 1552 | 1218 | 3413 |

| M | PSOE | arnauramirez | 7134 | 514 | 324 | 6093 |

| M | PSOE | asanchog | 137 | 146 | 144 | 2 |

| M | PSOE | astro_duque | 522,984 | 159 | 41 | 29,125 |

| M | PSOE | cesarjramos | 9120 | 598 | 187 | 4246 |

| M | PSOE | conjosemfranco | 7058 | 1731 | 1662 | 5525 |

| M | PSOE | dioufluc | 1708 | 432 | 425 | 90 |

| M | PSOE | felipe_sicilia | 10,472 | 372 | 306 | 18,655 |

| M | PSOE | franciscopolo | 24,769 | 709 | 642 | 657 |

| M | PSOE | germanrenau | 1200 | 189 | 88 | 354 |

| M | PSOE | gomezdcelis | 9463 | 230 | 122 | 8309 |

| M | PSOE | guillermomeijon | 2795 | 765 | 597 | 1415 |

| M | PSOE | hectorgomezh | 5370 | 332 | 250 | 3720 |

| M | PSOE | javieranton | 1438 | 330 | 311 | 116 |

| M | PSOE | javiercerqueir4 | 252 | 317 | 125 | 578 |

| M | PSOE | javizqui | 5140 | 779 | 594 | 5678 |

| M | PSOE | jccampm | 6106 | 267 | 141 | 2381 |

| M | PSOE | jcduran_ | 5957 | 362 | 353 | 192 |

| M | PSOE | jfrserrano | 3536 | 902 | 541 | 1508 |

| M | PSOE | jlaceves | 2443 | 2889 | 2696 | 907 |

| M | PSOE | joseantoniojun | 405,094 | 573 | 417 | 45,650 |

| M | PSOE | josluisramosro2 | 235 | 131 | 130 | 0 |

| M | PSOE | jruizcarbonell | 10,373 | 262 | 235 | 187 |

| M | PSOE | juanb0462 | 386 | 146 | 137 | 9 |

| M | PSOE | juanluissotoadd | 2409 | 651 | 437 | 552 |

| M | PSOE | j_zaragoza_ | 48,567 | 418 | 11 | 158,209 |

| M | PSOE | lcsahuquillo | 1262 | 55 | 55 | 0 |

| M | PSOE | luisplanas | 13,176 | 328 | 159 | 6938 |

| M | PSOE | marclamua | 3097 | 280 | 228 | 591 |

| M | PSOE | migonzalezcaba | 1542 | 458 | 337 | 645 |

| M | PSOE | montimar66 | 1481 | 52 | 28 | 450 |

| M | PSOE | morissiero | 1273 | 1158 | 954 | 1513 |

| M | PSOE | nasholop | 5462 | 780 | 499 | 11,024 |

| M | PSOE | odonelorza2011 | 56,853 | 1118 | 192 | 28,813 |

| M | PSOE | pabloaranguena | 2428 | 519 | 51 | 15,358 |

| M | PSOE | patxilopez | 195,809 | 234 | 162 | 13,409 |

| M | PSOE | pedrosaurag | 5536 | 118 | 100 | 109 |

| M | PSOE | pedro_casares | 7061 | 996 | 538 | 17,958 |

| M | PSOE | perejoanpons | 4123 | 1181 | 634 | 1097 |

| M | PSOE | pmklose | 15,558 | 1837 | 913 | 13,581 |

| M | PSOE | salazarropaco | 5543 | 518 | 375 | 11,369 |

| M | PSOE | sanchezcastejon | 1,351,574 | 628 | 332 | 284,959 |

| M | PSOE | santicl | 4070 | 159 | 137 | 888 |

| M | PSOE | sarrimorell | 1853 | 231 | 222 | 3 |

| M | PSOE | sergio_gp | 7978 | 785 | 627 | 2055 |

| M | PSOE | simancasrafael | 25,695 | 654 | 500 | 44,649 |

| M | PSOE | valentingarciag | 4665 | 802 | 590 | 447 |

| M | PSOE | viondi | 6535 | 1890 | 571 | 103,622 |

| F | UP | ainavs | 14,655 | 516 | 322 | 7825 |

| F | UP | antonia_jover_ | 1260 | 156 | 49 | 216 |

| F | UP | gagupilar | 3569 | 254 | 102 | 3803 |

| F | UP | gloriaelizo | 20,056 | 742 | 498 | 21,838 |

| F | UP | ionebelarra | 69,252 | 204 | 141 | 20,034 |

| F | UP | isabel_franco_ | 13,447 | 407 | 204 | 14,110 |

| F | UP | lauralopezd | 2343 | 163 | 105 | 659 |

| F | UP | luciadalda | 2208 | 423 | 366 | 2616 |

| F | UP | margpuig | 5328 | 227 | 87 | 1458 |

| F | UP | maria_podemos | 1891 | 715 | 270 | 7168 |

| F | UP | marisasaavedram | 1623 | 501 | 279 | 2104 |

| F | UP | martinavelardeg | 4528 | 681 | 264 | 2563 |

| F | UP | roser_maestro | 3008 | 131 | 87 | 515 |

| F | UP | sofcastanon | 27,590 | 677 | 256 | 23,745 |

| F | UP | veranoelia | 48,083 | 142 | 93 | 8404 |

| F | UP | vickyrosell | 83,699 | 607 | 279 | 59,418 |

| F | UP | yolanda_diaz_ | 97,692 | 726 | 330 | 195,440 |

| M | UP | agarzon | 1,124,488 | 504 | 305 | 140,042 |

| M | UP | alber_canarias | 48,644 | 133 | 97 | 9804 |

| M | UP | antongomezreino | 14,567 | 1388 | 1067 | 21,902 |

| M | UP | ensanro | 29,365 | 474 | 219 | 51,465 |

| M | UP | eselkaos | 3459 | 1026 | 771 | 2969 |

| M | UP | g_pisarello | 41,505 | 816 | 542 | 27,690 |

| M | UP | hector_illueca_ | 7533 | 74 | 61 | 2398 |

| M | UP | ismael_cortesg | 1935 | 315 | 296 | 627 |

| M | UP | jaumeasens | 77,359 | 733 | 386 | 43,254 |

| M | UP | joanmena | 28,971 | 489 | 293 | 12,949 |

| M | UP | juralde | 83,061 | 1780 | 895 | 106,468 |

| M | UP | j_sanchez_serna | 11,223 | 363 | 253 | 27,173 |

| M | UP | mayoralrafa | 97,475 | 180 | 134 | 21,231 |

| M | UP | pnique | 536,961 | 1147 | 589 | 653,245 |

| M | UP | roberuriarte | 5169 | 142 | 20 | 2406 |

| M | UP | txemaguijarro | 4577 | 237 | 179 | 1335 |

| F | VOX | crisestebanvox | 5943 | 1767 | 759 | 13,653 |

| F | VOX | eledhmel | 62,742 | 419 | 66 | 137,998 |

| F | VOX | georgina_vox | 3057 | 534 | 429 | 6000 |

| F | VOX | lourdesmndezm1 | 12,489 | 564 | 520 | 10,974 |

| F | VOX | macarena_olona | 121,559 | 3176 | 2275 | 820,263 |

| F | VOX | malenanevado | 3473 | 563 | 250 | 6132 |

| F | VOX | meerrocio | 9977 | 1768 | 1267 | 71,004 |

| F | VOX | mestremanuel | 14,029 | 1865 | 1668 | 16,530 |

| F | VOX | patriciadlheras | 4050 | 448 | 195 | 9055 |

| F | VOX | rromerovilches | 15,720 | 980 | 708 | 17,268 |

| F | VOX | ruizsolas | 5416 | 39 | 13 | 1572 |

| F | VOX | teresagdvinuesa | 2839 | 953 | 890 | 5884 |

| F | VOX | _patricia_rueda | 8854 | 509 | 447 | 4883 |

| M | VOX | agustinrosety | 44,040 | 1612 | 659 | 234,249 |

| M | VOX | a_lopezmaraver | 1263 | 123 | 120 | 794 |

| M | VOX | cfdezrocysua | 5088 | 2016 | 1663 | 36,585 |

| M | VOX | czambranogr | 257 | 135 | 99 | 412 |

| M | VOX | edelvallerod | 4011 | 7767 | 6976 | 26,839 |

| M | VOX | fjconpe | 10,417 | 1064 | 545 | 19,733 |

| M | VOX | fjosealcaraz | 38,100 | 4383 | 2631 | 203,771 |

| M | VOX | igarrigavaz | 63,900 | 1462 | 962 | 120,222 |

| M | VOX | ivanedlm | 225,450 | 1422 | 962 | 544,576 |

| M | VOX | jlsteeg_doc | 417 | 11 | 9 | 0 |

| M | VOX | joaquinrobles55 | 1877 | 1763 | 1427 | 5934 |

| M | VOX | joseramirezdel2 | 8695 | 5260 | 4100 | 34,231 |

| M | VOX | juanjoaizcorbe | 4134 | 347 | 239 | 11,043 |

| M | VOX | luisgestoso | 4094 | 3386 | 2018 | 53,436 |

| M | VOX | mariscalzabala | 23,501 | 617 | 529 | 25,344 |

| M | VOX | mazureque | 235 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| M | VOX | ortega_smith | 141,367 | 1021 | 923 | 100,778 |

| M | VOX | pablosaezam | 15,741 | 413 | 165 | 15,274 |

| M | VOX | pcalvoliste | 2101 | 1506 | 1306 | 5002 |

| M | VOX | pedro_fhz | 26,928 | 976 | 939 | 11,591 |

| M | VOX | rafalomana | 15,384 | 64 | 28 | 1564 |

| M | VOX | rchamode | 6781 | 3713 | 3017 | 11,707 |

| M | VOX | rodrijr111 | 2032 | 715 | 400 | 3917 |

| M | VOX | rubenmansolivar | 5357 | 683 | 68 | 9484 |

| M | VOX | sanchezdelreal | 50,262 | 4117 | 1848 | 255,674 |

| M | VOX | santi_abascal | 450,989 | 1048 | 752 | 1,427,478 |

| M | VOX | vicpiedra | 8739 | 561 | 393 | 11,788 |

References

- Armstrong, Cory L., and Fangfang Gao. 2011. Gender, Twitter and News Content. Journalism Studies 12: 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baitinger, Gail. 2015. Meet the Press or Meet the Men? Examining Women’s Presence in American News Media. Political Research Quarterly 68: 579–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, Javier, Gallego Aina, Huidobro Alba, Romero Enrique, and Padró Lluís. 2020. Male and female politicians on Twitter: A machine learning approach. European Journal of Political Research 60: 239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgewater, Jack, and Robert Ulrich Nagel. 2020. Is there cross-national evidence that voters prefer men as party leaders? No. Electoral Studies 67: 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtzaeg, Petter Bae. 2017. Facebook is no “Great equalizer”: A big data approach to gender differences in civic engagement across countries. Social Science Computer Review 35: 103–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu, Josep-Lluís Micó-Sanz, and Míriam Díez-Bosch. 2020. Digital Publich Sphere and Geography: The Influence of Physical Location on Twitter’s Political Conversation. Media and Communication 8: 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Nuria Roca. 2017. La modernización de la campaña electoral para las elecciones generales de España en 2015. ¿Hacia la americanización? Comunicación y Hombre Num 13: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, Meredith, Sarah Oliver, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, and Caroline Heldman. 2015. From Ferraro to Palin: Sexism in coverage of vice-presidential candidates in old and new media. Politics, Groups, and Identities 3: 573–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, James M. 2016. Gender, Party, and Presentation of Family in the Social Media Profiles of 10 State Legislatures. Social Media and Society 2: 2056305116646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaway, Johanna, Regina G. Lawrence, Rose Melody, and Christopher R. Weber. 2013. How Female Candidates Shape Coverage of Senate and Gubernatorial Races. Political Research Quarterly 66: 715–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, Laurel. 2020. The Growing Partisan Gap among Women in Congress. Society 57: 520–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Heather K., and Jennifer Hayes Clark. 2016. ‘You Tweet Like a Girl!’: How Female Candidates Campaign on Twitter. American Politics Research 44: 326–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Fraile, and María Eugenia. 2008. Historia de las mujeres en España: Historia de una conquista. La Aljaba 12: 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández García, N. 2013. Mujeres políticas y medios de comunicación: Representación en prensa escrita del gobierno catalán (2010). Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico 19: 365–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Todd, Dan Jackson, and Marcel Broersma. 2016. New platform, old habits? Candidates’ use of Twitter during the 2010 British and Dutch general election campaigns. New Media and Society 18: 765–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Solé, Frederic, and Hibai López-González. 2019. Government Formation and Political Discussions in Twitter. An Extended Model for Quantifying Political Distances in Multiparty Democracies. Social Science Computer Review 37: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Solé, Frederic. 2018. Interactive Behavior in Political Discussions on Twitter: Politicians, Media, and Citizens’ Patterns of Interaction in the 2015 and 2016 Electoral Campaigns in Spain. Social Media + Society 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Solé, Frederic, and Mas-Manchón Lluís. 2017. Estructura de los tweets publicados durante las campañas electorales de 2015 y 2016 en España. El Profesional de la Información 26: 805–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hemphill, Libby, Annelise Russell, and Angela M. Schöpke-Gonzalez. 2020. What Drives U.S. Congressional Members’ Policy Attention on Twitter? Policy and Internet 82: 446–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, Mirya R., Jennifer L. Merolla, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2011. Sex, Stereotypes, and Security: A Study of the Effects of Terrorist Threat on Assessments of Female Leadership. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 32: 173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrbková, Lenka, and Alena Macková. 2020. Campaign like a girl? Gender and communication on social networking sites in the Czech Parliamentary election. Information, Communication & Society, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Lingshu, and Michael Wayne Kearney. 2020. Gendered Tweets: Computational Text Analysis of Gender Differences in Political Discussion on Twitter. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 0261927X20969752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstonbaugh, Morgan. 2020. Standing Up for Women? How Party and Gender Influence Politicians’ Online Discussion of Planned Parenthood. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy 41: 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungherr, Andreas. 2014. Twitter in politics: A comprehensive literature review. Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2402443 (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Jungherr, Andreas, and Harald Schoen. 2013. Das Internet in Wahlkämpfen: Konzepte, Wirkungen und Kampagnenfunktionen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiss, Daniel. 2016. Seizing the moment: The presidential campaigns’ use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle. New Media & Society 18: 1473–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Stephanie Greco. 2001. American Women and Politics in the Media: A Review Essay. Political Science and Politics 34: 227–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiseau, Estelle, and Keiko Nowacka. 2015. Can Social Media Effectively Include Women’s Voices in Decision-Making Processes?” OECD Development Centre. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/DEV_socialmedia-issuespaper-March2015.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2017).

- Lovenduski, Joni. 2005. Feminizing Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lünenborg, Margreth, and Tanja Maier. 2015. ‘Power Politician’ or ‘Fighting Bureaucrat’: Gender and power in German political coverage”. Media, Culture & Society 37: 180–96. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Shannon C., and Rachel R. Mourão. 2016. Talking Politics on Twitter: Gender, Elections, and Social Networks. Social Media and Society 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Melissa K., and Jeffrey S. Peake. 2013. Press effects, public opinion, and gender: Coverage of Sarah Palin’s vice-presidential campaign. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18: 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Kathryn, and Logan Dancey. 2011. Elevating Women’s Voices in Congress: Speech Participation in the House of Representatives. Political Research Quarterly 64: 910–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauchfleisch, Adrian, and Julia Metag. 2020. Beyond normalization and equalization on twitter: Politicians’ twitter use during non-election times and influences of media attention. Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies 9: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Karen, Elisabeth Evans, Lisa Harrison, Mary Shears, and Khursheed Wadia. 2013. The gender of news and news of gender. International Journal of Press/Politics 18: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Calero, María Luisa, María Lourdes, Vinuesa Tejero, and Paloma Abejón Mendoza. 2013. Las mujeres políticas en España y su proyección en los medios de comunicación. Razón y Palabra 82: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sobieraj, Sarah, Gina M. Masullo, Philip N. Cohen, Tarleton Gillespie, and Sarah J. Jackson. 2020. Politicians, Social Media, and Digital Publics: Old Rights, New Terrain. American Behavioral Scientist 64: 1646–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern, Rosalynd, and Emily Harmer. 2019. Twitter, Incivility and “Everyday” Gendered Othering: An Analysis of Tweets Sent to UK Members of Parliament. Social Science Computer Review 39: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromble, Rebekah K., and Karin Koole. 2020. She belongs in the kitchen, not in congress? Political engagement and sexism on twitter. Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies 9: 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe Otalora, Ainhoa. 2013. Las cuotas de género y su aplicación en España: Los efectos de la Ley de Igualdad (LO 3/2007) en las Cortes Generales y los Parlamentos Autonómicos. Revista de Estudios Políticos 160: 159–97. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, Nikki, Jesse Holcomb, and Justin Littman. 2018. Twitter Makes It Worse: Political Journalists, Gendered Echo Chambers, and the Amplification of Gender Bias. International Journal of Press/Politics 23: 324–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, Celia. 2008. Spain—Women in Parliament: The Effectiveness of Quotas. In Women and Legislative Representation: Electoral Systems, Political Parties, and Sex Quotas. Edited by Manon Tremblay. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 123–33. [Google Scholar]

- Verge, Tània. 2010. Gendering Representation in Spain: Opportunities and Limits of Gender Quotas. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 31: 166–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verge, Tània. 2012. Institutionalising Gender Equality in Spain: From Party Quotas to Electoral Gender Quotas. West European Politics 35: 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verge, Tània. 2015. The Gender Regime of Political Parties: Feedback Effects between “Supply” and “Demand”. Politics & Gender 11: 754–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verge, Tània, and Maria de la Fuente. 2014. Playing with different cards: Party politics, gender quotas and women’s empowerment. International Political Science Review 35: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verge, Tània, and Aurélia Troupel. 2011. Unequals among Equals: Party strategic Discrimination and Quota Laws. French Politics 9: 260–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verge, Tània, and Nina Wiesehomeier. 2019. Parties, Candidates, and Gendered Political Recruitment in Closed-List Proportional Representation Systems: The Case of Spain. Political Research Quarterly 72: 805–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, Maurice, Liesbeth Hermans, and Steven Sams. 2013. Online social networks and microblogging in political campaigning. Party Politics 19: 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, Maurice. 2015. Twitter and Political Campaigning. Sociology Compass 9: 745–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Kevin M., Jason Gainous, and Mirya R. Holman. 2017. I Am Woman, Hear Me Tweet! Gender Differences in Twitter Use among Congressional Candidates. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 38: 430–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasburn, Philo C., and Mara H. Wasburn. 2011. Media coverage of women in politics: The curious case of Sarah Palin. Media, Culture & Society 33: 1027–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Claudia, and Sven Joeckel. 2018. Gendered morality and backlash effects in online discussions: An experimental study on how users respond to hate speech comments against women and sexual minorities. Sex Roles 80: 381–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).