Abstract

West Java is known as an area with high fertility rates in Indonesia; this high fertility is due to various factors, including the area’s geological nature, which causes the soil to be rich in nutrients for various types of plants. Because of these conditions, West Java has historically been an agricultural area and has become a food granary. Some regions in West Java are critical buffer zones for big cities such as Jakarta. As a farming area, the people of West Java have an agricultural tradition with a pattern such as a permaculture, which is known by the local community as “talun-kebun”. The “talun-kebun” is a form of shifting between cultivation and wet rice production regarding location, management, and production. Along with the massive conversion of agricultural land, the rural tradition of “talun-kebun” was later replaced by an intensive agricultural pattern using pesticides. Land conversion also caused abandoned land and abandoned agricultural areas, which have become critical land. Regarding critical land, several studies reveal that around 30% of greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change come from land conversion and deforestation. Therefore, critical land rehabilitation is one form of effort that can be achieved in overcoming climate change. Departing from the problematic situation, this paper discusses the policies that the Government of Indonesia and the Government of West Java Province can undertake in reviving and utilizing the tradition of “talun-kebun” as a model of local permaculture to help increase food production in a sustainable manner, thus rehabilitating critical land. Using a qualitative approach through literature studies, this paper makes some policy recommendations to revive the tradition of “talun-kebun” in the West Java region.

1. Introduction

West Java Province is known as a fertile area and is one of Indonesia’s primary sources of food production. In 2019, according to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, West Java Province ranked third as a rice producer in Indonesia [1]. Meanwhile, the results of Prayitno et al.’s study show that all regencies and cities in West Java Province are included in the food security category [2]. However, several indicators can cause food vulnerability, namely the high percentage of households that do not have access to clean water, low food availability in the several regencies and cities, and low life expectancy [2].

In addition, in terms of the fertility of agricultural land in West Java, according to the Head of the Agency of Food Crops and Horticulture of West Java Province, the urgent issue that requires attention is related to the restoration of soil fertility, which has decreased a lot because of too intensive agricultural business in West Java, which is saturated with using raw materials chemically [3]. Soil fertility problems certainly have an impact on rice production. Therefore, in addition to efforts to restore land fertility, other measures such as reducing rice consumption and replacing it with other local food resources are necessary to ensure sustainable food security.

Regarding efforts to replace rice with other local food resources, a study by Hartrisari et al. shows that reducing rice consumption and replacing consumption with other carbohydrate sources will significantly impact rice sufficiency in West Java Province [4]. In addition to food resources, several studies also mention local fruit that many indigenous peoples commonly cultivate as food security alternatives. For example, in their study, Pratama et al. discussed the role of fruits in providing nutritional security and contributing to local ecosystems [5].

Use of carbohydrate food resources such as cassava and fruits as alternative food sources, as well as efforts to improve the local agricultural ecosystem, are activities related to “talun-kebun”, a traditional farming practice, which although faded, is still performed in West Java. “Talun-kebun” is an upland land-use system in which annual food crops or commercial crops (kebun) alternate successively with tree crops (talun) [6]. “Talun-kebun” is one of the traditional agroforestry or permaculture systems in Java, which has been practiced for centuries [7].

Regarding “talun-kebun”, the study by Christanty et al. showed how the “talun-kebun” system of bamboo growth in West Java survives on minimal external fertilizers, and how this is closely related to the growth habits and biogeochemical characteristics of the bamboo, namely rapid biomass accumulation, litter accumulation, and very high fine root biomass [6]. Referring to the study by Christanty et al., the “talun-kebun” system also has an essential role in the conservation and rehabilitation of critical land to improve the quality of local ecosystems.

The problem then is how indigenous knowledge such as “talun-kebun” can be utilized through government policies in both the Central Government and the West Java Provincial Government, so that the knowledge can be developed to improve local ecosystems, especially those related to rehabilitation of critical lands, thus meeting the need for sustainable food security. Many scholars have studied the use of indigenous knowledge to solve environmental problems, including Ajani et al. The latter studied how to use indigenous knowledge as a strategy for climate change adaptation among farmers in sub-Saharan Africa [8]. However, there are many cases of failed indigenous policies, as stated by Huencho [9]. Therefore, several things need to be considered so that the policy to encourage the utilization of “talun-kebun” can be successful.

Referring to the problematic situation, this article seeks to discuss the policies that the Government of Indonesia and the Government of West Java Province can undertake in reviving and utilizing the tradition of “talun-kebun” as a model of local permaculture to help increase food production in a sustainable and rehabilitate critical land.

2. Methods

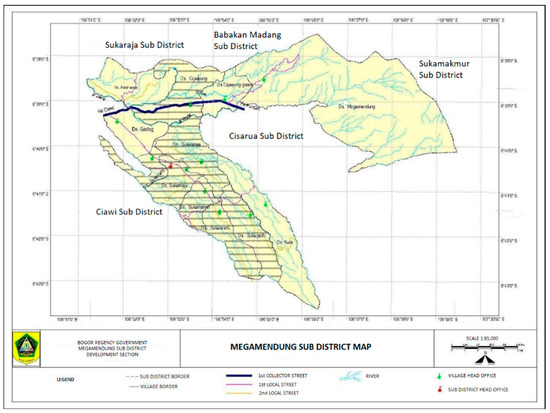

To answer the main issues raised, this article uses a qualitative approach by searching various literature that discusses “talun-kebun” in West Java. The literature used is in the form of books, articles, reports, news, and various other documents. In addition, observations were also made on the condition of several “talun-kebun” practices that exist in several locations close to the writers’ activities, namely in Megamendung Village, Megamendung Sub District, Bogor Regency (see Figure 1). This location is where the writers have been working for the last four years, and there are several agroforestry or permaculture practices.

Figure 1.

Megamendung Subdistrict Map.

Various data and information from several examples of the literature discussing “talun-kebun”, as well as the writer’s observations, were analyzed descriptively by describing and summarizing various conditions and situations that occurred in the practice of “talun-kebun”. This descriptive analysis is expected to provide an overview of the potential of “talun-kebun” to be raised through several policy proposals that both the Central Government and the West Java Provincial Government can undertake. Before the analysis is outlined, the author has described the perspective of policy theory in utilizing indigenous knowledge such as “talun-kebun” and the understanding of the “talun-kebun” system itself.

3. Policy on Utilizing Indigenous Knowledge

According to Puffer, there are several reasons for the importance of indigenous knowledge. It can help to discover the best development solutions and it highlights successful people dealing with their environment [10]. Indigenous knowledge can be used to find the best solution in solving community problems; these solutions are likely to be well received because they have been practiced for a long time.

In addition, according to Subramanian and Pisupati, this traditional knowledge system continues to evolve, adapting to changing circumstances and realities, and at the same time contributing to ecological resilience [11]. Therefore, to help the community to use indigenous knowledge adequately, it is necessary to study it and place it in an appropriate position to solve various societal problems. Policies for the use of indigenous knowledge must be made and implemented adequately. For this reason, it is necessary to ensure the availability of an institutional and policy framework that supports the making of adequate indigenous knowledge utilization policies.

To ensure adequate policies in the utilization of indigenous knowledge, several challenges need to be considered and prioritized in promoting this knowledge, as stated by Gorjestani; these challenges are: encouraging the government to formulate and implement strategies for integration; increasing network capacity nationally and regionally; promoting local exchange and adaptation; and identifying innovative mechanisms for protection by encouraging further development, promotion, validation, and exchange [12]. The policies that will be made must be able to accommodate these priorities.

Meanwhile, to ensure that policies related to indigenous knowledge are successful, we also need to study why policies related to this matter fail. Huencho [9], in her study in Chile, revealed several similarities in how various indigenous public policies in Latin America were problematic, including lack of institutional adaptation; little integration of cultural, value, historical, and social elements in policy; ignorance on the part of political actors; and lack of participation, relevance, and resources.

For the case in Chile itself, the results of Huencho’s study [9] show several matters that must be considered for the policy to be successful, namely: the interdependence between policy design and policy processes and programs, and the relevance of the cultural and political dimensions of indigenous people to prevent policy failure. In terms of policy design and policy processes and programs, the implementation process has not become a space for reformulating policy, even when the policy’s limitations have been stated. In addition, “power asymmetry” and “cultural asymmetry” are variables that affect the outcome; the policy will be limited if the paradigm does not change.

Regarding the relevance of the political and cultural dimensions of indigenous peoples, there are several matters that, according to Huencho [9], need to be assessed, including the need to consider the introduction of channels that allow for the active role of indigenous people, both in the policy process and as recipients; another factor to consider is reducing policymaker bias that affects indigenous people’s expectations and increases distrust and delegitimacy, which in turn leads to low participation of indigenous people in decision-making, and to other impacts on misunderstanding and persistence of failure. In addition, the link between the formulation process and policy implementation also needs to be considered to reduce the occurrence of discoordination.

By referring to various opinions from experts described in the previous paragraphs, it is clear that the successful use of “talun-kebun” requires the consideration of many different matters. In particular, the consideration of how to integrate and adapt “talun-kebun” with various programs, policies, and the existing situation in the community, and how to build networks to gain broad support from multiple groups. In addition, policies must be made participatory and adaptive for various developments to be accepted and run well.

4. “Talun-Kebun” as Traditional Practices Relevant to Sustainable Development Goals

The earliest literature describing the existence of “talun-kebun” can be found in the article by Terra [13]. When discussing the Sundanese agricultural system, Terra mentions the “talun system” as a form of original agricultural system in Sunda (West Java). The talun system performs its agricultural activities by planting annual crops, generally around the village by dibble method. The talun system is usually combined with the tipar system (semi-permanent dry rice cultivation), the field system (dry rice shifting cultivation), the secondary cropping system (shifting cultivation by planting all types of annual crops and tubers after rice), and storage systems (buffalo, poultry, and goat farming). As a result of the influence of Java, the talun system was later changed to a mixed garden.

“Talun-kebun” is a form of cultivation that lies between huma and rice fields where huma is believed to represent the evolutionary basis for both “talun-kebun” and for rice, which was introduced from Central Java towards the middle of the eighteenth century [14]. On lands where rice production is impossible, communities begin to select forest plants and introduce species from other areas to obtain greater benefits, so some natural forests are gradually converted into “artificial” forests [14].

4.1. Characteristics of “Talun-Kebun”

According to Soemarwoto, “talun-kebun” is a new type of shifting cultivation whose development is based on the traditional knowledge and experience of the community, which has many positive environmental effects and offers traditional ecological wisdom [15]. “Talun-kebun” is a typical agroforestry system consisting of a mixture of perennials and annuals, giving it a structure familiar to the forest [16]. “Talun-kebun” are generally found outside the village, are rarely found inside the village, and originate from the forest through forest species selection and introduction of new species [16]. Although it consists of many species, one or more species may be dominant in a “talun-kebun” [16].

Structurally, “talun-kebun” usually has a canopy that is layered so that it looks like a forest with annual plant species at the bottom, and with species composition differing from place to place, influenced by factors such as climate, soil, and markets [15]. “Talun-kebun”, which is essentially an artificial forest, is analogous to the forest stage in shifting cultivation but provides more economic benefits to the community, where the crops are harvested and mostly sold [15]. “Talun-kebun,” like forests, protect the soil from the erosive forces of rain [15].

“Talun-kebun” are private properties located on lower hillsides and are sometimes very steep. Still, erosion is minimal due to the terraced canopy structure and litter layer on the talun floor [15]. Planting is achieved by making holes in the ground with a wooden stick, into which seeds or seedlings are planted [15].

The “talun kebun” system usually consists of three stages that are functionally related and form a cycle and have different functions: (1) garden (kebun), (2) mixed garden (kebun campuran), and (3) talun, where each stage has a different function [7]. The garden (kebun) is the first stage, usually planted with a mixture of seasonal crops, and has a high economic value because most crops are sold in cash [7]. After two years, tree seedlings begin to grow in the fields. The land for annual crops is reduced so that the gardens gradually develop into mixed gardens (kebun campuran), where annual crops are mixed with half of the growing perennials, and the economic value is not as high as before, but it does have high biophysical value because it promotes soil and water conservation [7]. After the annual harvest, the fields are usually left for two to three years to dominate perennials. This stage is known as talun and has economic and biophysical value [7].

4.2. Type of “Talun-Kebun”

According to Christanty et al., based on the dominant type, talun in West Java can be divided into three types: wood lot (dominated by a mixture of firewood and wood species); permanent mixed talun (dominated by a mix of fruit trees and annual commercial crops); and talun bamboo (the best example of a “talun-kebun” rotation cycle, dominated by bamboo species with trees scattered among bamboo clumps) [6]. In terms of types of plants, the results of Suharjito’s research suggest several main reasons for “talun-kebun” farmers when choosing plant types, namely: plants that produce a great or maximum yield; crops that produce different results; easy-to-maintain plants; marketable plants; and crops whose prices are stable or rising [17].

4.3. Function of “Talun-Kebun”

There are several functions of the “talun-kebun”, which are as follows:

- Economic and social function, because the crops can be sold and have a high selling value, and they also meet the farmer’s own needs. Moreover, landless and poor farmers are allowed to take fallen branches and twigs or cut down dead wood for firewood and are employed at harvest time [16];

- Soil conservation and sustainability, because soil erosion in the “talun-kebun” is minimal because it has well-developed hydrological and erosion control functions [16];

- “Talun-kebun” is also a genetic resource due to its high multispecies composition with several wild or semi-wild species [15].

4.4. The Relevance of “Talun-Kebun” to the Sustainable Development Goals

If the “talun-kebun” is associated with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals [18], then, in the author’s view, it is related to the following five goals, namely:

- Goal 1: No poverty. “Talun-kebun” can contribute to the achievement of the no poverty goal. Referring to Soemarwoto and Soemarwoto [16], the results of the “talun-kebun” system have a high enough income potential, resulting in the potential to contribute to poverty eradication efforts;

- Goal 2: Zero hunger. “Talun kebun” can contribute to the achievement of zero hunger’s goals. In the “talun-kebun” system, various food crops, both those containing carbohydrates and multiple types of fruit and other food crops, are grown. The harvest from “talun-kebun” is also used to fulfill family needs other than for sale so that it can also contribute to fulfilling food security;

- Goal 5: Gender equality. Referring to the findings of Mizuno et al. [19], the principle of gender equality is still alive and well. From the perspective of land tenure and labor allocation, the contribution of women is clear. In many cases, the land owned by the wife is more significant than that owned by the husband and the labor allocated by the women. Therefore the “talun kebun” system can contribute to achieving the goals of gender equality;

- Goal 13: Climate action. Various plants grown in the “talun-kebun” system will, of course, have a significant contribution to absorbing CO2 so that they can contribute to efforts to overcome climate change;

- Goal 15: Life on land. The “talun-kebun” system has several functions, including those related to genetic resources by looking at the biodiversity of the various plants grown and the different types of animals and insects that live in their ecosystems, apart from their ability to conserve soil and rehabilitate critical lands. Therefore, the “talun-kebun” system can contribute to achieving the goal of life on land.

5. Discussion: The Current Condition of “Talun-Kebun” and Possible Policy Directions

By using various literature sources and limited observations in the Megamendung Village area where the authors live, this section attempts to describe the condition of “talun-kebun” and the policy directions that can be taken to utilize this practice. This section consists of two parts, namely the current conditions of the practice of “talun-kebun” in West Java and policy directions that can be undertaken.

5.1. The Current Condition of the “Talun-Kebun” Practice

Referring to several pieces of the literature, the “talun-kebun” system is still practiced today. Iskandar, for example, revealed that the “talun-kebun” system is still widely practiced by the Sundanese people [20].

The practice of “talun-kebun” can be found, for example, in several indigenous communities. Suganda, in his writings, for example, describes the practice of “talun-kebun” performed by the indigenous community of Kasepuhan Ciptagelar [21]. The “talun-kebun” practiced by the indigenous people of Kasepuhan Ciptagelar usually consists of gardens of wood, vegetables, fruits, and other horticulture [21]. “Talun-kebun” is a source of timber needs from the Kasepuhan Ciptagelar indigenous people so that they do not need to take from the forest for their timber needs. Therefore, the forest around the community’s location can be maintained [21].

Regarding the “talun-kebun” in the Kasepuhan Ciptagelar indigenous community, Kodir, in his research, stated the high diversity and richness of plant species [22]. In addition, by referring to the potential data of Kasepuhan Ciptagelar in 2008 cited in Kodir’s research, it is known that the area of “talun-kebun” in this indigenous community is 35 hectares or 17.33% of the total land-use area of 202 hectares [22]. This condition is in line with the research by Christanty et al. in 1986, which stated that the use of “talun-kebun” land in West Java was 16% [7].

Soemarwoto [15] stated that the “talun kebun” system is usually private or communal property. Related to this, according to Winarti in her research, citing various sources, the average land area owned for “talun-kebun” is around 400 square meters to 1.2 hectares [23]. Based on the observations made by the authors regarding ownership and control of land by farmers around the location of the author’s activity, most of the farmers are cultivators on state land or work on other people’s land with a profit-sharing system. Regarding farmers who work on other people’s land, the research of Inoue et al. revealed that private land owned by others could be a safety net for a small number of people or farmers who have access to the land [24]. Or, in other words, who cooperate or are given access by the landowner.

Seeing a situation like this and based on observations made, in several locations where there is a lot of abandoned land in the sense that it is owned by someone (usually not living in the area) but is not being used, it is possible to seek a pattern of cooperation or provide access to farmers who do not have land with a “talun-kebun” system. Therefore, the abandoned land can provide benefits both economically and to the environment.

In addition to the aspect of land ownership, gender equality is also a matter that requires attention. Although, as Mizuno et al. highlighted, the principle of gender equality is still alive and well in the “talun-kebun” system [19], there are still disparities. The wife’s wider land ownership compared to her husband still creates a gender bias in the perspective of food allocation. In terms of food intake (energy and protein) and protein adequacy, the level obtained by women always remains lower than men [19]. In line with this condition, Wiyanti’s research found that although women have a significant role and contribution in “talun-kebun,” the decision-making in the “talun-kebun” system is still dominated by men, where women can give advice. Still, the final decision remains on the male side [25].

Another problem that needs to be considered is the change of “talun-kebun” into a commercial garden with a monoculture system to eliminate the multi-functions that have been the peculiarity of “talun-kebun,” which are not only economic but also social and conservational. The problem of converting “talun-kebun” into a commercial garden has also been identified by Chrisanty et al. [7] and stated by Kimmins et al. [26] and Iskandar [20]. This situation, of course, needs to be assessed by considering the multifunctionality of “talun-kebun,” which has many benefits, especially in terms of conservation.

The conversion of “talun-kebun” into a commercial garden, in the author’s view, can also be caused by the pattern of its development where, in the third phase, mixed gardens turn into talun, and their utilization is limited only to the utilization of their wood products. Related to this, it is necessary to consider that during the mixed garden phase (after the garden phase), the plants that must be planted are plants such as fruits, so that when the gardens enter the talun phase, they can still produce fruits that can be consumed or sold. In other words, in the authors’ view, the consideration should be of how to direct the talun into a food forest. Therefore, in this effort to develop “talun-kebun”, farmers also need support to run the plants in their “talun-kebun” so that it becomes a food forest.

5.2. Policy Directions to Utilize “Talun-Kebun”

By considering several problems encountered in the implementation of the “talun-kebun” system, there are several policy directions that can be considered by the Central and West Java Provincial Governments to be able to utilize them so that they can contribute both to conservation and food security, as described below:

- Ensure that the existing practice of “talun-kebun” can be maintained because it is proven to have an essential function for food security, economy, social, and environmental conservation. To minimize the shift in the function of “talun-kebun,” farmers also need to gain support from both central and regional governments in running “talun-kebun” to be directed to plant types of plants that can become food forests. In addition, farmers also need to be assisted by both central and regional governments in terms of marketing their harvests so that they can provide better economic potential;

- For “talun-kebun” to develop and to conserve the environment of abandoned land, the government can seek to provide access to farmers who do not own land so that they can take advantage of abandoned land; this can be achieved by providing incentives and disincentives for the owners or rulers of abandoned land so that they are willing to give access to the use of abandoned land for “talun-kebun” activities. In addition, the social forestry program that is currently being promoted is more focused on management with the “talun-kebun” system compared to monoculture;

- To strengthen gender equality, efforts are needed to improve women’s skills, especially in providing added value to post-harvest products so that they can enhance their household economy;

- Promoting the “talun-kebun” system to gain the community’s attention and expand its support network in various circles of society.

6. Concluding Remarks

In summary, it can be concluded that “talun-kebun” is a traditional practice that needs to be maintained and developed because it has various functions that can support food security, economy, social matters, and conservation. For this reason, the government needs to consider several matters in this effort, including encouraging “talun-kebun” towards a food forest so that the harvest after becoming talun can still be economically promising. In addition, it is important to consider how to ensure better access to the use of abandoned land and how to increase women’s skills in post-harvest management and promotion of the vital function of “talun-kebun”. A more in-depth study is needed to provide an adequate basis for the government to make optimal policies in the effort to utilize “talun-kebun”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K. and E.K.; methodology, T.K. and E.K.; formal analysis, T.K. and E.K.; investigation, T.K. and E.K.; resources, T.K. and E.K.; data curation, T.K. and E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K. and E.K.; visualization, T.K. and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Inilah 10 Besar Provinsi Penghasil Beras. Available online: https://www.pertanian.go.id/home/?show=news&act=view&id=4425 (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Prayitno, G.; Dito, M.; Hidayat, A.R.T. Ketahanan Pangan Kabupaten/Kota Provinsi Jawa Barat. J. Agribus. 2020, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesuburan Tanah Pertanian di Jawa Barat Mendesak Dipulihkan. Available online: https://deskjabar.pikiran-rakyat.com/ekbis/pr-1131339520/kesuburan-tanah-pertanian-di-jawa-barat-mendesak-dipulihkan (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Hartrisari; Rahardja, S.; Udin, F.; Imantho, H.; Suyamto, D. Model Ketahanan Pangan Berbasis Sumberdaya Lokal (Studi Kasus Provinsi Jawa Barat). In Proceedings of the Seminar Hasil-Hasil PPM IPB, Bogor, Indonesia, 28 November 2013; Volume II, pp. 698–709. [Google Scholar]

- Pratama, M.F.; Ddwiartama, A.; Rosleine, D.; Abdulharis, R.; Irsyam, A.S.D. Documentation of Underutilized Fruit Trees (UTF) across indigenous communities in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2019, 20, 2603–2611. [Google Scholar]

- Christanty, L.; Mailly, D.; Kimmins, J.P. “Without bamboo, the land dies”: Biomass, litterfall, and soil organic matter dynamics of a Javanese bamboo talun-kebun system. For. Ecol. Manag. 1996, 87, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christanty, L.; Abdoellah, O.S.; Marten, G.G.; Iskandar, J. Traditional Agroforestry in West Java: The Pekarangan (Homegarden) and Kebun-Talun (Annual-Perennial Rotation) Cropping Systems. In Traditional Agriculture in Southeast Asia: A Human Ecology Perspective; Marten, G.G., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1986; pp. 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Anjani, E.N.; Mgbenka, R.N.; Okeke, M.N. Use of Indigenous Knowledge as a Strategy for Climate Change Adaptation among Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for Policy. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2013, 2, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Huencho, V.F. Why do Indigenous public policies fail? Policy Stud. 2021, 43, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, P. The Value of Indigenous Knowledge in Development Programs Concerning Somali Pastoralists and Their Camels; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 1995; 9p. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.M.; Pisupati, B. Traditional Knowledge in Policy and Practice: Approaches to Development and Human Well-Being; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjestani, N. Indigenous Knowledge for Development: Opportunities and Challenges. Indigenous Knowledge for Development Program the World Bank. Available online: https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website00297C/WEB/IMAGES/IKPAPER_.PDF (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Terra, G.J.A. Farm Systems in South-east Asia. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1958, 6, 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Soemarwoto, O.; Christanty, L.; Henky; Herri, Y.H.; Iskandar, J.; Hadyana; Priyono. The Talun-Kebun: A man-made forest fitted to family needs. Food Nutr. Bull. 1985, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemarwoto, O. The Talun-Kebun System, a modified shifting cultivation, in West Java. Environmentalist 1984, 4, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Soemarwoto, O.; Soemarwoto, I. The Javanese Rural Ecosystem. In Introduction to Human Ecology Research on Agricultural Systems in Southeast Asia; Rambo, A.T., Sajise, P.E., Eds.; The University of the Philippines at Los Banos: College, Laguna, Philippines, 1984; pp. 254–287. [Google Scholar]

- Suharjito, D. Pemilihan Jenis Tanaman Kebun-Talun: Suatu Kajian Pengambilan Keputusan oleh Petani. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2002, VIII, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Mizuno, K.; Mugniesyah, S.S. (Eds.) Sustainability and Crisis at the Village: Agroforestry in West Java, Indonesia (The Talun-Huma System and Rural Social Economy); Gadjah Mada University Press: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2016; pp. 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, J. Upaya Pelestarian Ekologi Tatar Sunda. In Proceedings of the Konferensi Internasional Budaya Sunda II, Revitalisasi Budaya Sunda: Peluang dan Tantangan dalam Dunia Global, Bandung, Indonesia, 19–22 December 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Suganda, K.U. The Ciptagelar Kasepuhan Indigenous Community, West Java: Developing a bargaining position over customary forest. In Forest for the Future: Indigenous Forest Management in a Changing World; Kleden, E.O., Chidley, L., Indradi, Y., Eds.; Indigenous Peoples Alliance of The Archipelago & Down to Earth: Jakarta, Indonesia; Cumbria, UK, 2009; pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kodir, A. Keanekaragaman dan Bioprospek Jenis Tanaman dalam Sistem Kebun Talun di Kasepuhan Ciptagelar, Desa Sirnaresmi, Kecamatan Cisolok, Sukabumi, Jawa Barat. Master’s Thesis, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor Regency, Indonesia, 23 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Winarti, I. Habitat, Populasi, dan Sebaran Kukang Jawa (Nycticebus Javanicus Geoffroy 1812) di Talun Tasikmalaya dan Ciamis, Jawa Barat. Master’s Thesis, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor Regency, Indonesia, 9 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M.; Tsurudome, Y.; Mugniesyah, S.S.M. Hillside Forest land as a safety net for local people in a mountain village in West Java: An examination of differences in the significance of national and private lands. J. For. Res. 2003, 8, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiyanti, D.T. Peran Perempuan dalam Sistem Kebun Talun di Desa Karamatmulya, Kecamatan Soreang, Kabupaten Bandung, Jawa Barat. Sosiohumaniora 2015, 18, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kimmins, J.P.; Welham, C.; Cao, F.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Christanty, L. The Role of Ecosystem-level Models in the Design of Agroforestry Systems for Future Environmental Conditions and Social Needs. In Towards Agroforestry Design: An Ecological Approach; Advances in Agroforestry; Jose, S., Gordon, A.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).