1. Introduction

The Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (hereunder “HRADF” or “Fund”) was established in 2011 (founding Law No. 3986/2011 [

1]) and promotes and implements the Hellenic Republic’s asset development programme, with the vision to achieve the following:

Deliver long term, sustainable and investor-friendly asset developments that are socially acceptable;

Create new job opportunities;

Help restructure markets to the benefit of end consumers, always ensuring value accretion to all stakeholders.

The duration of HRADF is until 1 July 2026. Its sole shareholder is the Hellenic Corporation of Assets and Participations (HCAP). HRADF manages part of the state’s private property to maximise its value and contributes largely to public debt reduction by attracting direct investments through the implementation of the Asset Development Plan (ADP) [

2], which is updated on a six-month basis. The portfolio of assets entrusted to HRADF to facilitate its development plan is diverse. It includes companies’ shares, infrastructure assets, and real estate in the most competitive market categories (energy, transport, tourism, etc.). In addition, HRADF holds 100% of shares in 10 port authorities [

3], which have the right to operate the respective ports until 2042.

In addition, Law 4799/2021 [

4] provided for the possibility of assigning to HRADF the maturation of contracts that are part of the Development Programme for Contracts of Strategic Importance, and with the recent law 4804/2021 [

5], the purpose of HRADF was expanded, to include the provision of maturation services through a discrete operational unit at HRADF (Project Preparation Facility/PPF), maximizing amongst others the impact of EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, from 2021 onwards. According to this law, in pursuing the purpose of the Fund, particular care shall be taken to contribute to achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations.

Greece itself is committed to sustainable development and supports the long-term strategic vision by 2050 of a European economy that does not burden the climate. In this context, HRADF can be a driving force of Greece towards achieving Sustainable Development by integrating sustainability principles throughout HRADF’s value creation process while supporting HRADF strategic objectives. One recent development towards that direction is that the latest updated ADP of the Fund, which was approved by the Government Council for Economic Policy (KYSOIP) on 13/5/2021, includes for the first time guidelines for the incorporation of the principles of sustainability and the adoption of ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) criteria during the implementation of the Fund’s programme, thereby reinforcing the attraction of responsible investments to the benefit of the Greek economy and society, contributing at the same time towards achieving the national energy and climate goals.

The development of the private property of the Hellenic Republic has been a critical pillar of the effort to correct the structural problems and macroeconomic imbalances that had led Greece to the profound social and economic crisis of the last decade. The economic impact of the Fund’s programme is expected to be multi-dimensional, going far beyond the revenues from the sale transaction. According to IOBE, 2020 [

6], HRADF’s programme is shown to have had a strong positive impact on the Greek economy, with clear social benefits during a challenging period for the country. For the overall programme, it is estimated to have boosted the country’s GDP by around EUR 1 bn a year on average over the period 2011–2019, with the benefits for the economy estimated to have exceeded EUR 20 billion. Over the same period, the average impact on employment was close to 20,000 full-time jobs. In addition, the HRADF’s programme brings significant improvements and interventions in the regulatory framework and investment commitments, which have stimulated economic activity and increased the efficiency of the production factors during a challenging period for Greece. Finally, the international investor community has seen HRADF’s programme progress as evidence of the state’s commitment to reform the Greek economy.

As a country thirsting for investment and seeking to shift its development model to a more sustainable path, Greece should take advantage of the opportunities offered by the global market trend for green projects and use innovative financing tools that will facilitate the flow of capital into sustainable investments. Sustainability at HRADF aims at leveraging HRADF’s position at the intersection of investment, sustainability, and regulation to streamline sustainable investment in Greece.

To that end, HRADF first developed the digital ESG Rating tool [

7] in cooperation with European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Global Sustain. Subsequently, the Fund’s sustainability team modified it to include KPIs that will support the assessment of the readiness of its portfolio companies to adopt climate technologies. HRADF began deploying the modified tool with the fund’s portfolio of ports. The methodology was intended to deliver a service that would improve information transparency and communication between investors and entrepreneurs, accelerate technology readiness of ports and ultimately enhance their climate resilience that, according to UNCTAD, 2020 [

8], “is a matter of strategic economic importance and key in achieving progress on many of the Goals and targets under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”.

2. Background

Infrastructure and transport are among the sectors most exposed to climate change. Moreover, they are critical to national economic performance, growth and development. Ports in particular play a vital role in the world economy. More than 80% of goods traded worldwide are transported by sea and through ports. Climate risks analyses and subsequent climate-proofing need to be incorporated as key features, given that the potential impact of climate change on ports will have a broad socio-economic impact. A port’s reputation for reliability is key to its success, so ports that are more resilient to disruption from climate events should fare better (IFC, 2011) [

9]. Therefore, ports need to strengthen resilience and adapt their infrastructure and relevant operations to the changing climate (WPSR, 2020) [

10].

Greece has the most extensive coastline throughout the EU. In addition, there is a well-developed port network within the country due to its morphology and the existence of many islands. Therefore, Greek ports, as clusters of transport, energy, industry and “Blue Economy” [

11], add significant value and contribute materially to the economy and society. Under the right conditions, they can be powerful accelerators for the circular economy and key strategic partners in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the objectives of the European Green Deal.

In particular, the adaptation of climate technologies in ports will enhance their “license to operate” and increase their economic and environmental competitiveness, which is expected to be critical to the “Blue Economy” of Greece [

12]. Therefore, ports that want to achieve sustainable development must assess their ability to adopt such technologies and identify their strengths and weaknesses.

Ports’ adoption of climate technologies will require financing from banks or investment companies. However, global investors rely on their ability to manage and avoid risk, and increasingly that risk is being framed in terms of investment exposure to environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. Therefore, they are increasingly asking companies to evidence how they will comply with ESG requirements, particularly with regard to climate change. In addition to investor pressure, regulators around the world are increasingly pushing for climate disclosures.

Especially in the maritime industry that is entering an era where technological transition, climate change and shifts in government policy change their operating models, climate change adaptation is no longer a choice but an obligation. The European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO) [

13] proposes that EU legislation makes climate change adaptation a core principle in legislation and funding.

Recognising the needs for approaches to climate risk assessment and adaptation specific to ports that international institutions have underlined, the ESG-based methodology that was developed from the fund could provide a tool to port authorities to better understand their level of readiness to adopt climate technologies, help them identify gaps and needs for climate-related investments and enhance transparency towards their stakeholders.

3. The HRADF ESG-Based Methodology for Better Resource Allocation in Ports

Climate change has and will continue to shape the preference of investors and institutions shaping the market where HRADF operates. An example of this is the European Green deal, devised as a set of policy initiatives to make Europe climate neutral by 2050. This set of policies shape the investment priorities for the upcoming years and are designed to enable European communities to have access to funding mechanisms that support their climate transition strategies. The sustainability team at HRADF sought to support the mission of HRADF by proactively understanding whether the 10 ports under its management were prepared to adopt climate technologies from an organisational perspective. The sustainability team selected Climate Technologies as a theme as it is pertinent to climate adaptation and mitigation strategies, which are key components to be considered within the funding mechanisms of the European Green Deal.

3.1. Methodology Description

To assess the organisational readiness of the ports under HRADF management, the sustainability team had to address two challenges. First, identify an assessment mechanism, and second, define the KPIs to assess the readiness of ports.

Identifying an assessment mechanism was paramount as ports operate at capacity and currently do not have the incentives to take on additional tasks. Previously, HRADF had already communicated to ports about its plans to perform an internal initial ESG performance assessment. It would do so through the deployment of the HRADF ESG digital tool. With port management authorities having planned to complete the ESG assessment, the sustainability team saw this as an opportunity to gather information to understand the organisational readiness of ports to adopt climate technologies.

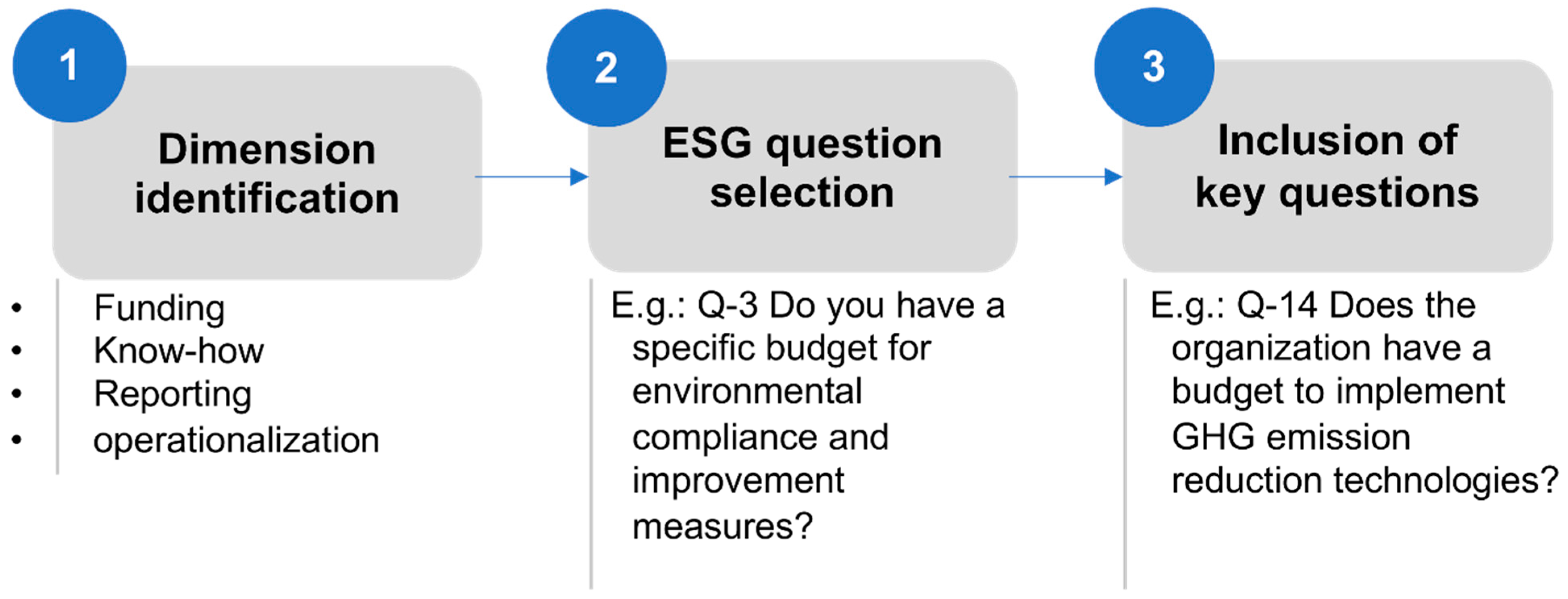

Defining KPIs required a three-stage process: first, identify dimensions relevant to organisational climate technology adoption; second, review the underlying ESG questionnaire and select relevant questions; third, define key complementing questions currently not included in the ESG questionnaire (

Figure 1).

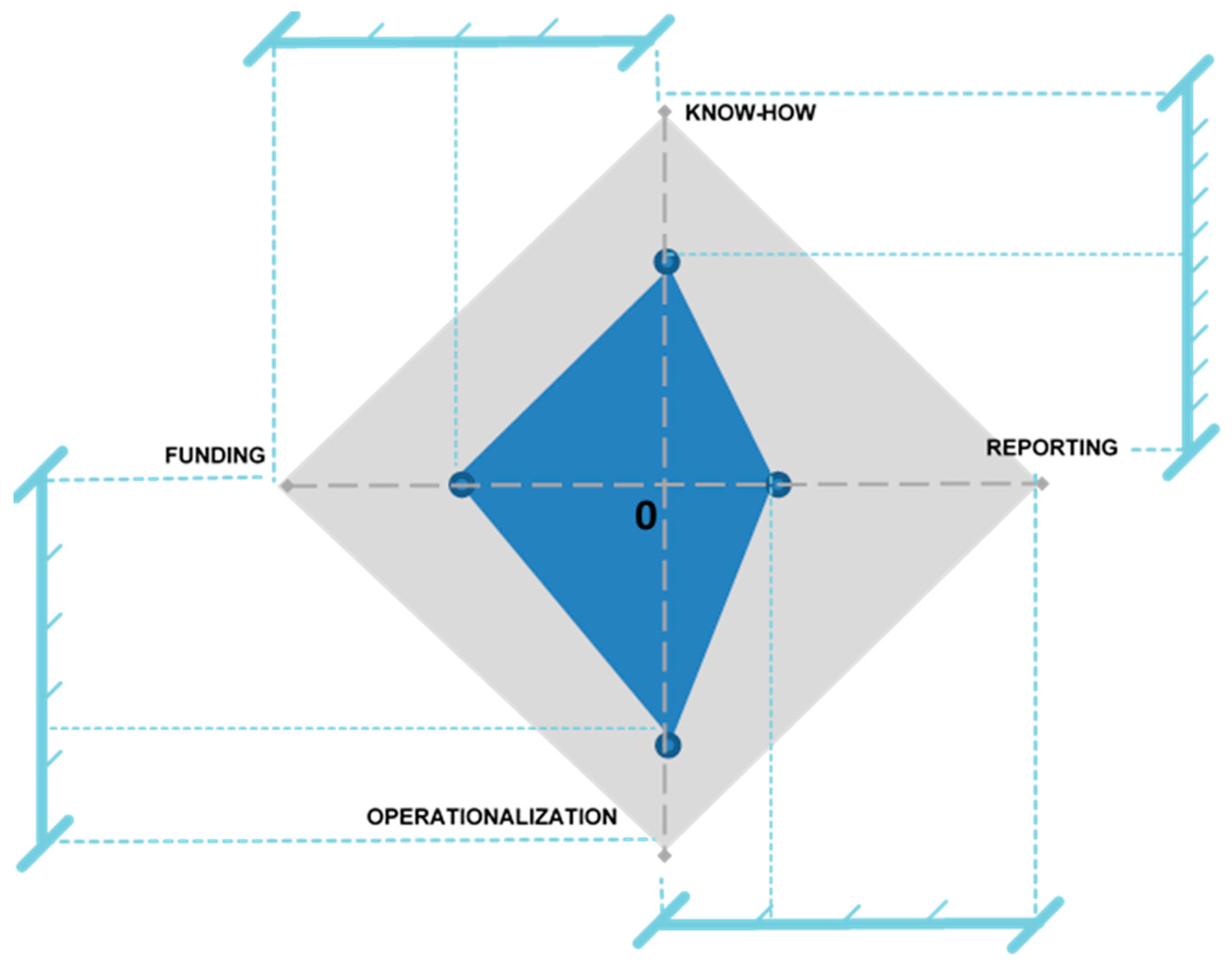

The sustainability team conceptualised the KPIs’ visualisation and its dimensions as a tool to provide executive decision makers with intuitive visual insights. In the context of this paper and HRADF’s portfolio, the tool provides an overview of the state of ports to adopt climate technologies. The tool is built after the following framework [

14]. The four dimensions are represented on an

XY axis, and the performance of each axis is relative to its own dimension. The purpose is to create a visual standard that can serve as a comparative baseline between port’s performance based on the thematic analysis (

Figure 2).

The funding dimension focused on determining whether a port had access to funding. It considered two questions, the first already part of the digital HRADF ESG Rating tool and the second being an addition to the ESG Rating tool questionnaire:

The know-how dimension assessed research efforts and practicality of the actions in the short and long terms. Only the first question from the following was part of the digital ESG Rating tool:

On a scale of 0 to 10, to what extent are you investigating innovation and technology opportunities to minimise GHG emissions?

Rate from 0 to 10 your research efforts to adopt technologies to reduce your GHG emissions in the short term (1–3 years);

Rate from 0 to 10 your research efforts to adopt technologies to reduce your GHG emissions in the mid-term (3–5 years);

Rate from 0 to 10 your research efforts to adopt technologies to reduce your GHG emissions in the long term (more than 5 years).

The reporting dimension was concerned with organisational reporting initiatives, and the extent to which the port authority had set a corporate structure for their reporting efforts. No questions were added to this dimension. It includes the following:

Do you have committees responsible for decision-making on ESG topics?

Have you appointed an executive-level position or positions with responsibility for ESG topics?

Do you have staff or an officer for the day-to-day management of ESG topics?

Do you (or your parent organisation) endorse and/or implement reporting or international standards?

The operationalisation dimension explored decarbonisation efforts and the involvement of finance departments. No questions were added. This dimension includes the following KPIs:

Do you have a decarbonisation programme in place?

Do you measure GHG emissions (scope 1) and set reduction targets?

Do you measure GHG emissions (scope 2) and set reduction targets?

Do you measure GHG emissions (scope 3) and set reduction targets?

Does the organisation have an appointed person/team/function to incorporate GHG reduction technologies with current operations?

Does the finance department provide input in evaluating GHG reduction initiatives?

3.2. Presentation of the KPIs

Once the mechanism and the KPIs to assess the readiness to adopt climate technologies were identified, the digital ESG Rating tool was deployed throughout the ten ports under HRADF’s management. In

Figure 3, we present a simulation of the results for six ports. The simulation does not reflect the actual ports’ performance. It is presented here as a practical visual aid. The grey area represents an ideal port scoring the maximum score possible in all dimensions. At the same time, it is visually intuitive to identify Port 3 as best in class among the group of the ports assessed, but that still needs improvement in the operationalisation, reporting and funding dimensions. On the other hand, port 5 and port 6 emphasise 2 of the dimensions, which signals that the other two dimensions need improvement.

Within the asset development and resource allocation frameworks, the thematic methodology and visual analysis previously described present a practical decision-making tool. This approach can help executive leaders at an organization with multiple assets identify the assets needing improvement at a granular level. For example, when comparing the performance of the operationalisation dimension of port 1 to port 6, the lack of involvement of the finance department in sustainability activities combined with the lack of GHG emissions measurements are likely to be the reason for the underperformance of port 6 on the operationalisation dimension. Depending on the organisational strategy, this insight could lead to developing an intervention targeting the organisational structure and operational activities of port 6 (change management). Additionally, this type of intervention can help optimise and prioritize the allocation of resources. For example, ports 5 and 6 are underperforming in different dimensions. While port 5 scores with the know-how and operationalisation dimensions and port 6 scores high with reporting, it is sensible to look at port 5 as a target for allocation of resources if the directive is to accelerate the adoption of climate technologies given that they already possess the know-how and have resources behind the operationalisation dimension. On the other hand, while port 6 might benefit from additional resources, the thematic and visual analysis provides a path to allocating these. For example, before allocating resources to the operationalisation dimension, improving the know-how dimension might make more sense.

4. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

This paper describes a methodology to assess the readiness of organisations to adopt climate technologies within the context of their transfer to private ownership from the perspective of a country asset development fund. It is worth mentioning that the work described in this paper is the first step and that further analysis is required to fine-tune the dimensions and the KPIs considered. Climate technologies (also known as cleantech, green technologies) as a thematic analysis was selected due to the potential benefits for the Greek blue economy. Future thematic analysis should target the assessment of critical resources efficiency and other topics such as governance transparency and inclusiveness.

While the team that developed the methodology and deployed it throughout all ports has experience with sustainability strategy and climate technologies, further development of the methodology requires the inclusion, or at least the input, of domain experts with an emphasis on organisational strategy.

The methodology described in this paper can serve as a starting point to initiate dialogue with ports’ stakeholders. Moreover, it can be incredibly insightful for stakeholders interested in positioning Greece as a global leader at the intersection of climate technologies and maritime affairs.

Climate change directly impacts port operations and infrastructure. Given the critical role of ports in the global trading system and their potential exposure to climate-related damage, disruptions, and delays, enhancing their climate resilience is a matter of strategic socio-economic importance for the global economy and society (UNCTAD, 2020) [

15].

Additionally, the recent pandemic has highlighted the need for ports to be prepared for drastic changes in demand and supply. The needed agility implies the modernisation of infrastructure systems. This modernisation is and will continue to be enabled by global economic packages, the European green deal, and the renewed visibility of ports as a critical element of global supply chains. This context provides the opportunity to utilise methodologies such as the one we propose as mechanisms to enable ports to allocate resources more efficiently to become more resilient and to take an active role in global decarbonisation efforts aligned with IPCC climate targets.

The crucial role of ports for a country’s economic growth and development, the need for action on climate change adaptation, and resilience-building for ports are increasingly being recognised, including as part of the Global Climate Action Pathways for Transport and Resilience [

16]; however, much more remains to be done. Until now, there has been very little analysis on how ports are affected by climate change, and even less evidence of how ready they are to adopt climate technologies. Therefore, the methodology presented in this paper provides a resource to understand the needs of ports leveraging the broad embracement of ESG assessment.