Abstract

The emerging development of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) software receivers has opened new opportunities in diverse operations. However, non-line-of-sight (NLOS) concatenated signal reception is one prevalent deterioration factor causing positioning errors in urban scenarios. To enhance integrity and reliability through receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) techniques in urban environments, distinguishing between line-of-sight (LOS) and NLOS signals facilitates the exclusion of NLOS channels: this is challenging due to uncertain signal reflections/refractions from diverse obstruction conditions in the built environment. Moreover, NLOS features show similarity to multipath effects like scattering and diffraction which causes difficulty in identifying the NLOS type. Recent work exploited NLOS detections with multi-correlator outputs using neural networks that outperform using signal strength techniques for NLOS detection. This paper proposes a neural network approach designed to recognise and learn spatial features among early, late, and prompt correlator outputs, differentiating between correlations, and also by memorising temporal features to acquire propagation information. Specifically, the spatial features of correlator IQ streams are derived from convolutional layers incorporated with concatenations, to formulate associate models like early-minus-late discrimination. A Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), i.e., long short-term memory (LSTM), is integrated to obtain comprehensive temporal features; hereby, a softmax classifier is appended in the last layer to distinguish between NLOS and LOS signals. By simulating synthetic datasets generated by a Spirent simulator and captured by a software-defined radio (SDR), the correlator outputs are acquired during the scalar tracking stage. The product of the proposed network demonstrates high performance in terms of accuracy, time consumption and sensitivity, affirming the efficiency of utilising early-stage correlations for NLOS detection. Moreover, an impact analysis of varying the sliding window length on NLOS discrimination underscores the need to fine-tune the parameter, as well as balancing accuracy, operation complexity and sensitivity.

1. Introduction

The GNSS service is one of the prominent positioning solutions facilitating various applications such as the navigation of autonomous vehicles [1]. For operations under radio frequency (RF)-harsh environments like urban canyons, large positioning errors are often discovered due to reflective surfaces from obstructions like surrounding buildings and skyscrapers that yield position errors. Specifically, the GNSS signals are reflected, diffracted or blocked, which are key factors in causing multipath and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) phenomena that further deteriorate the positioning accuracy of GNSS. Due to showing similarities between the multipath and NLOS signals on correlator outputs, detecting and excluding NLOS channels that do not include LOS components during the position, velocity, and timing (PVT) calculation is always challenging. Specifically, the acquisition of NLOS information in the receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) technique facilitates fault detection and exclusion (FDE) to achieve satisfactory positioning performance [2].

GNSS constellation signals are generated using deterministic pseudo-random noise (PRN) code that is applied in acquisition and tracking stages to detect the presence of satellites using correlation functions. NLOS detection via correlations at the early stage is promising due to the fact that NLOS conditions exhibit unique patterns in the code domain evident from the correlator output. For instance, Ref. [3] presented a correlator-based first path detection augmented with a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to capture global correlation features with high resolution.

One category of NLOS detection methods from GNSS observations relies on hardware components like mounting cameras toward the zenith, e.g., a visible camera, a fish-eye camera, or an omnidirectional far-infrared camera [4]. Through real-time extraction of satellite elevations and locating satellites in the camera images after coordination transformation, the NLOS is determined when the satellites are blocked by the building in the video stream. NLOS detection using the dual-polarisation antenna is also popular, where NLOS is estimated by separately correlating the right-hand circularly polarized (RHCP) and left-hand circularly polarized (LHCP) signals and calculating differences in the carrier-to-noise density (C/N0) measurements [5]. Another promising approach has been widely exploited that uses aiding information extracted from 3D building models to design NLOS exclusion filters [6]. Specifically, the shadow matching method that predicts the satellite visibility from 3D building models and cross-checks with the actual measurements is evidenced to facilitate the position accuracy [7].

A prevalent NLOS discrimination method is through signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) characteristics, which assumes that NLOS signals exhibit lower signal strength due to the lack of direct line-of-sight (LOS) components [8]. Nevertheless, the signal strength may be affected by automatic gain control (AGC) mapping functions in the front-end, bringing changeable noise floors and errors in estimating the signal strength, especially when interference exists [9]. Moreover, the multipath and NLOS methods may reveal high similarities in SNR representations and are dependent on the tracking loop performance, necessitating the consideration of richer features for effective discrimination design. For instance, Ref. [4] detects NLOS signals from correlator outputs using feature representations of signal strength, number of local maxima, and distribution of the delay of the maximum correlation. The multiple types of NLOS features are therefore fed for NLOS detectors, applying a support vector machine (SVM) to achieve more accurate NLOS discrimination. A thorough review of machine learning-based multipath/NLOS detection and mitigation methods is summarized in [10], where fully connected neural networks (FCNNs) and SVM are particularly highlighted.

This study proposes a deep learning method for NLOS discrimination by processing correlator outputs in the code domain. In this study, NLOS representations are extracted from early–late prompt (ELP) correlators in IQ format, which capture raw correlation patterns affected by NLOS at an early stage. To enhance perception capabilities, a convolutional neural network (CNN) layer is applied to each individual correlation as the initial layer, activating dominant spatial features. This is followed by a recurrent long short-term memory (LSTM) network [11] to capture complex and long-term temporal dynamics for sequence training and predictions. The key contribution of this work is the proposal of a deep learning-based NLOS detector using correlation outputs. Instead of manually extracting NLOS features, the discrimination of NLOS is achieved through end-to-end tuning from the training dataset, incorporating historical samples to enhance performance.

2. Methodology

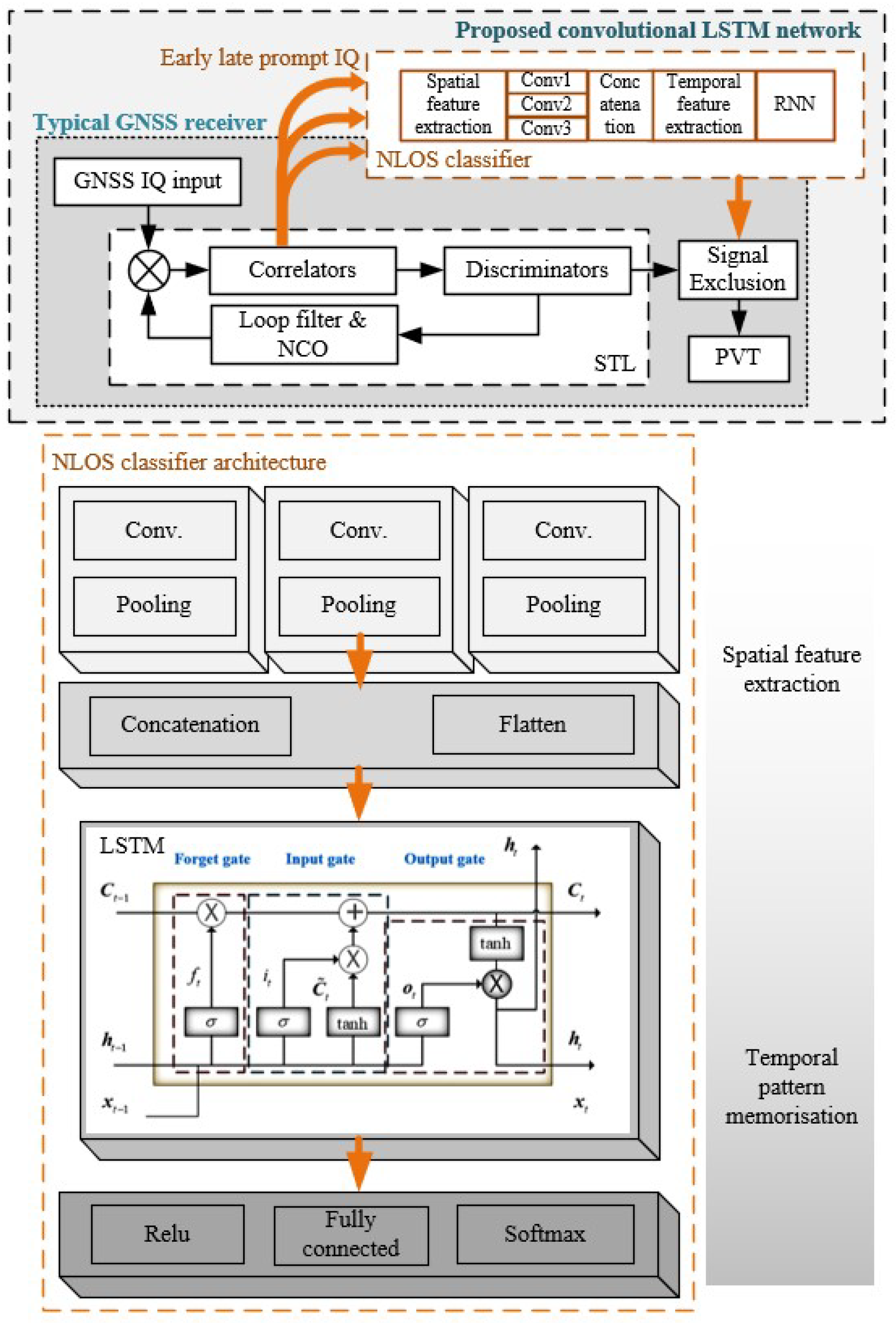

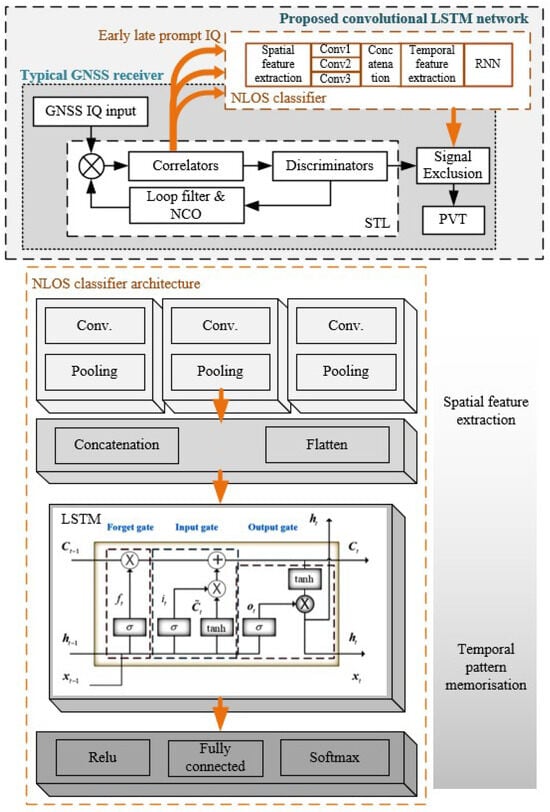

The outline of the NLOS mitigation scheme with the developed convolutional LSTM mechanism placed after correlators is illustrated in Figure 1. After the GNSS receiver retrieves baseband IQ samples after downsampling, the scalar tracking loop (STL) generates a local replica code per individual channel for each satellite. The ELP correlators are performed between the incoming IQ and replica code with a fixed code offset. Typical discriminators are developed from correlator outputs to extract phase, code delay, and frequency offset tracks for phase-locked loop (PLL), delay-locked loop (DLL), and frequency-locked loop (FLL), hereby fulfilling feedback loops to compensate errors like receiver numerically controlled oscillator (NCO) instability, over-the-air propagation, and Doppler shift. Incorporating the proposed CNN-LSTM architecture, the NLOS detector functions as a channel filter applied after correlators to identify and discard NLOS channels for signal selection. The NLOS detector takes IQ channel inputs from three correlators, utilizing a sliding window approach to balance detection rate and minimize false alarms.

Figure 1.

Overview of GNSS receiver architecture assisted with the proposed convolutional LSTM network—demonstrated with the STL tracking loop.

2.1. NLOS Correlation Representation

The received direct GNSS signal is denoted as follows:

where A, w, and stand for amplitude, carrier frequency, and phase at the time of antenna transmission, respectively.

Since the multipath affects the signal amplitude and phase essentially, the multipath channel model whose time-domain CIR representative is denoted by

where is the multipath channel; is the complex channel coefficient of the channel that can be calculated by , where and are the amplitude and phase of multipath signals; is the delay of the channel; is the Dirac delta function; and is the correlation interval that is wide enough to capture the NLOS representations.

The received signal with the multipath model is denoted by

Given a local replica correlation generated for the individual channel, the correlator output in the continuous form is denoted by

After sampling with , the discrete correlator output with prompt correlator is derived as

For the ELP correlators, the correlation output gives three IQ values at each epoch for each correlator, where the extra two correlation formulations, i.e., early correlation and late correlation , show an identical formulation except for fixed code delay. The LOS signal is believed to be the strongest path, and therefore the NLOS multipath signals are the formation where n starts from 1 excluding the 0 component.

2.2. Convolutional LSTM Structure

As the primary data-driven approaches, CNN and LSTM network structures have been extensively explored in signal processing applications [12]. It is well-recognized that CNN processes strong capability in spatial perceptions via deep-layer structures. LSTM reveals outstanding performance in mitigating the vanishing and exploding gradients problem, i.e., gradients diminish during backward propagation across layers [13], as well as incorporating temporal information in the prediction process. The integration of CNN and LSTM to leverage the advantages of both network structures has been studied in various applications, such as pedestrian trajectory prediction [14,15]. This paper introduces a convolutional LSTM structure designed to capture underlying spatial patterns in each correlator output. The extracted spatial features are processed to determine the relations between the correlators , , and over a time period before dealing with the temporal correlations.

Letting the CNN output for each correlator , , and be defined as , , and at time t, the correlator features after the feature transformation are hereby concatenated to form a 1D input sequence . Given the definitions of the hidden unit , input gate , forget gate , output gate , input modulation gate , and memory cell , the LSTM updates from previous inputs , , and are derived:

where the recurrent weights W and bias b are the parameters to be learned; stands for the hyperbolic tangent non-linearity function to squash inputs to a range; and denotes the activation function using the sigmoid function .

The detection task concludes with a softmax layer, which is used to predict the distribution and probability of the target of interest among different categories.

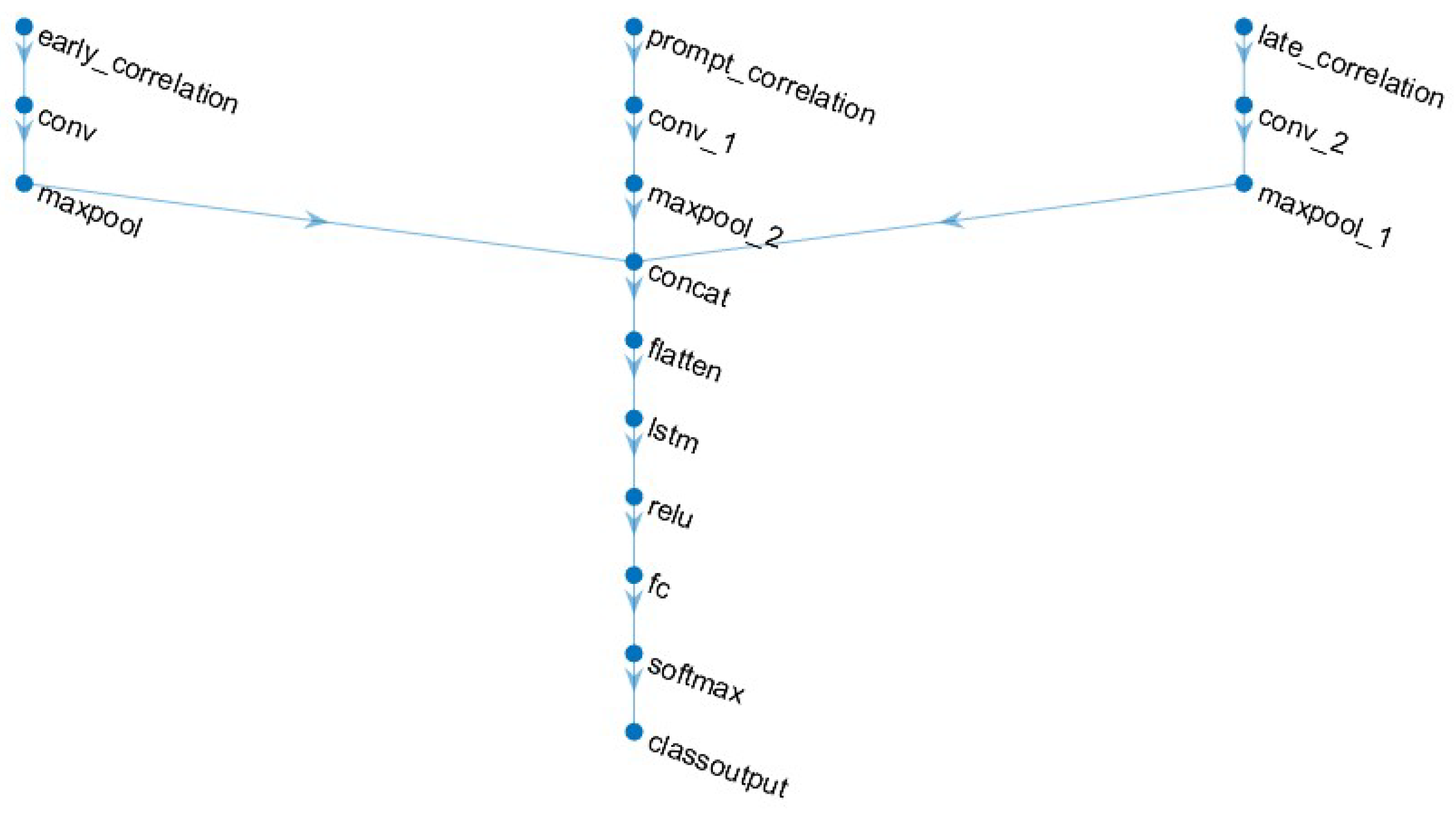

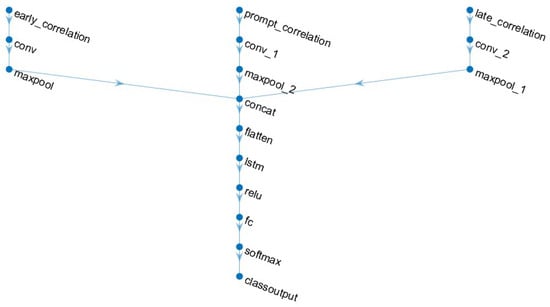

To address amplitude fluctuations in correlation patterns caused by low GNSS signal strength, NLOS detection is conducted by applying a sliding window approach over a period of samples, such as 500 samples equivalent to 500 milliseconds, for example. This method helps to capture and analyze temporal variations in signal characteristics for accurate NLOS discrimination. The directed acyclic graph (DAG) convolutional LSTM network structure is presented in Figure 2, and its detailed network configurations are discussed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Convolutional LSTM network structure with ELP correlation input.

Table 1.

DL network structure details with an input vector length of 500.

3. Results and Analysis

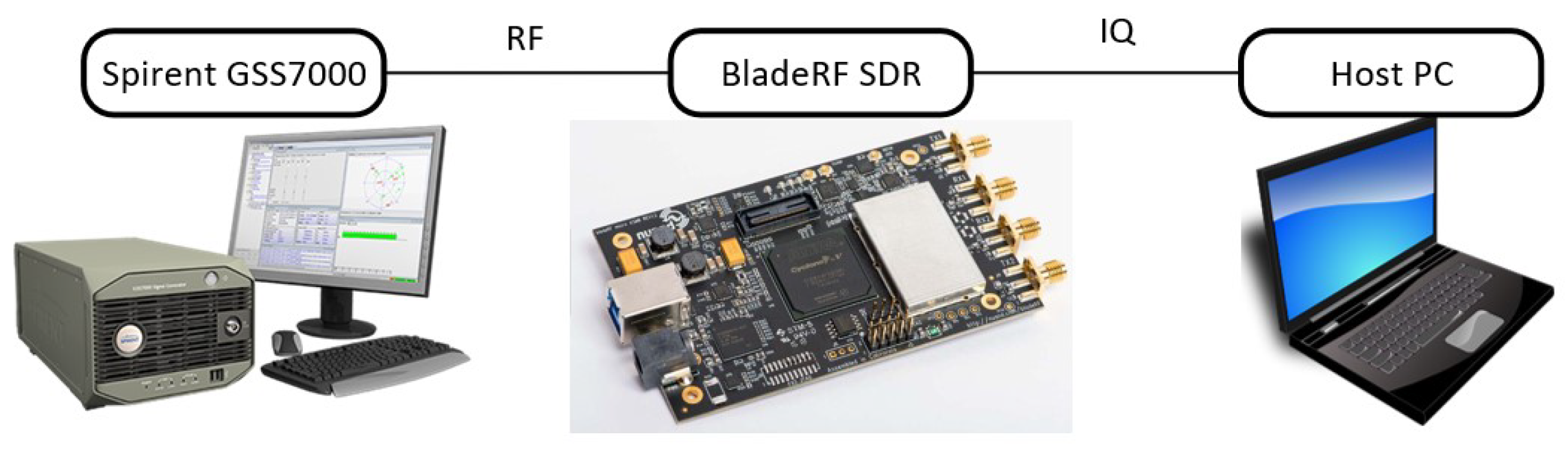

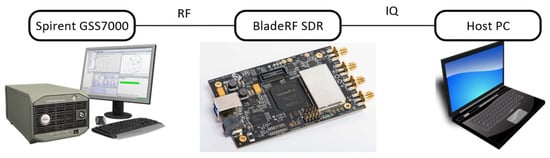

This paper’s simulation of NLOS effects adopts a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) test setup illustrated in Figure 3, utilizing a Spirent GSS7000 simulator (manufactured by Spirent UK, Sussex, UK) to produce high-fidelity synthetic datasets containing NLOS effects. The RF signals are downconverted to the baseband, and digitized using the BladeRF software-defined radio (SDR) before being saved into binary files on the host PC. The STL implementation with ELP correlators uses FGI-GSRx GNSS receiver software v1.0.0 [16], which is developed on Matlab to offer capabilities from multiple constellations including Galileo, GLONASS, BeiDou, and NavIC. The DLL ELP spacing is set up to 0.5 chip length. The DLL noise bandwidth is 1 Hz. The PLL noise bandwidth is 15 Hz of wide bandwidth, 15 Hz of narrow bandwidth, and 10 Hz of very narrow bandwidth.

Figure 3.

Hardware -in-the-loop test setup for NLOS and LOS GNSS RF simulations.

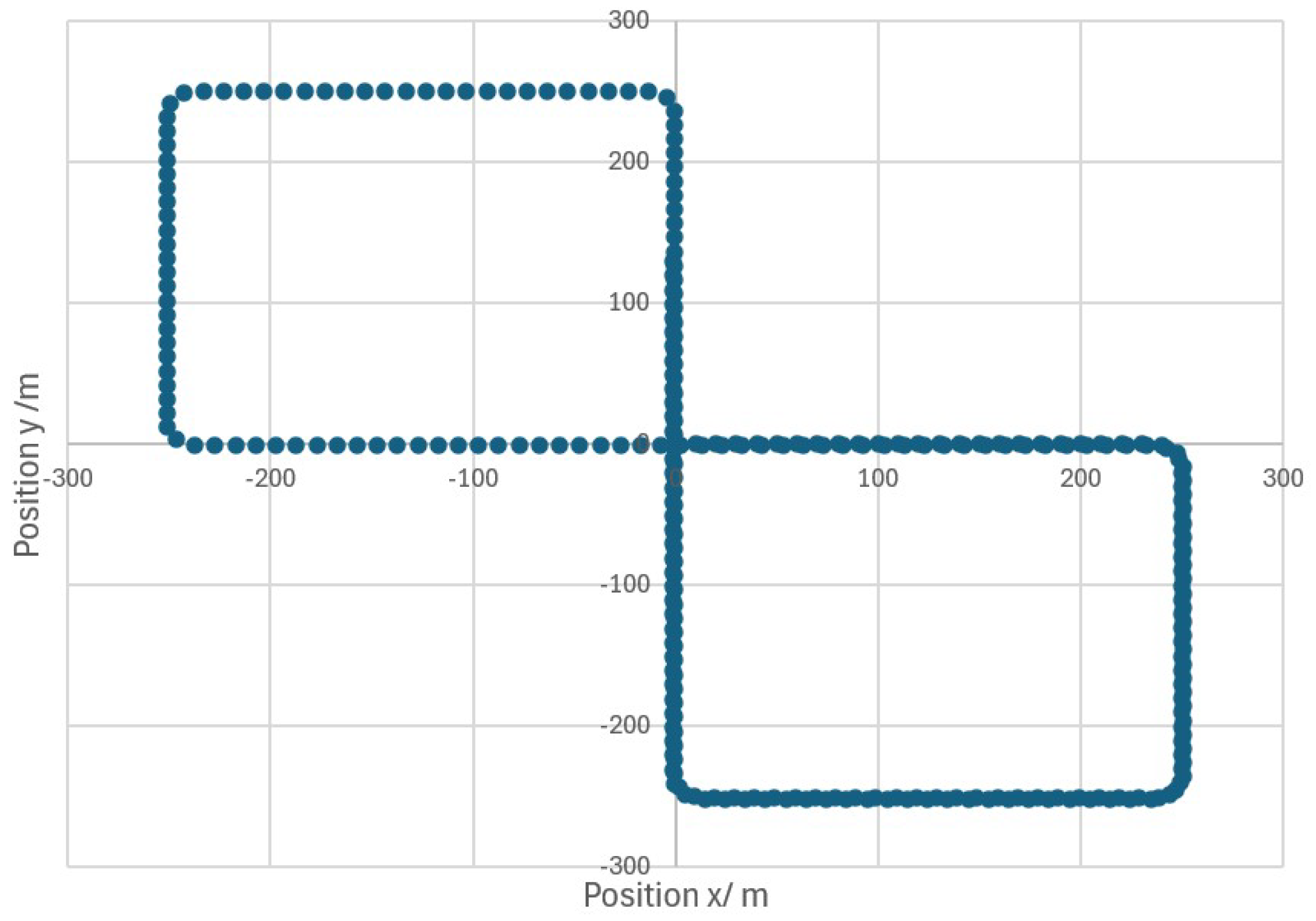

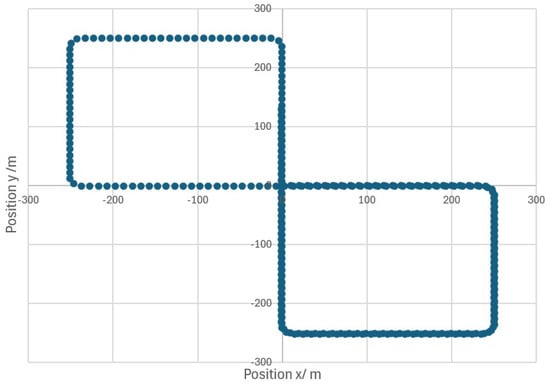

An analytical multipath model utilizing an urban scenario framework has been developed to synthesize a GPS L1 constellation dataset. This dataset comprises 2 NLOS, 5 multipath channels, and 2 LOS channels. These channels are dynamically adjustable throughout the simulation period. Typically, the SNR of LOS components ranges between 10 and 13 dB, while the SNR for NLOS components is below 0 dB. The model includes three multipath rays, one of which is the LOS ray. To illustrate the effect of the Doppler shift, a dynamic movement model is employed, specifically a vehicle model that adheres to the trajectory depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Simulated trajectory to collect NLOS RF dataset.

From the collected dataset, the IQ data obtained from ELP correlation are annotated with NLOS and LOS labels to construct the training and testing datasets. Channel labelling is performed by analysing the logged constellation files: channels lacking LOS components are designated as NLOS whilst the remaining channels are labelled as MP/LOS channels.

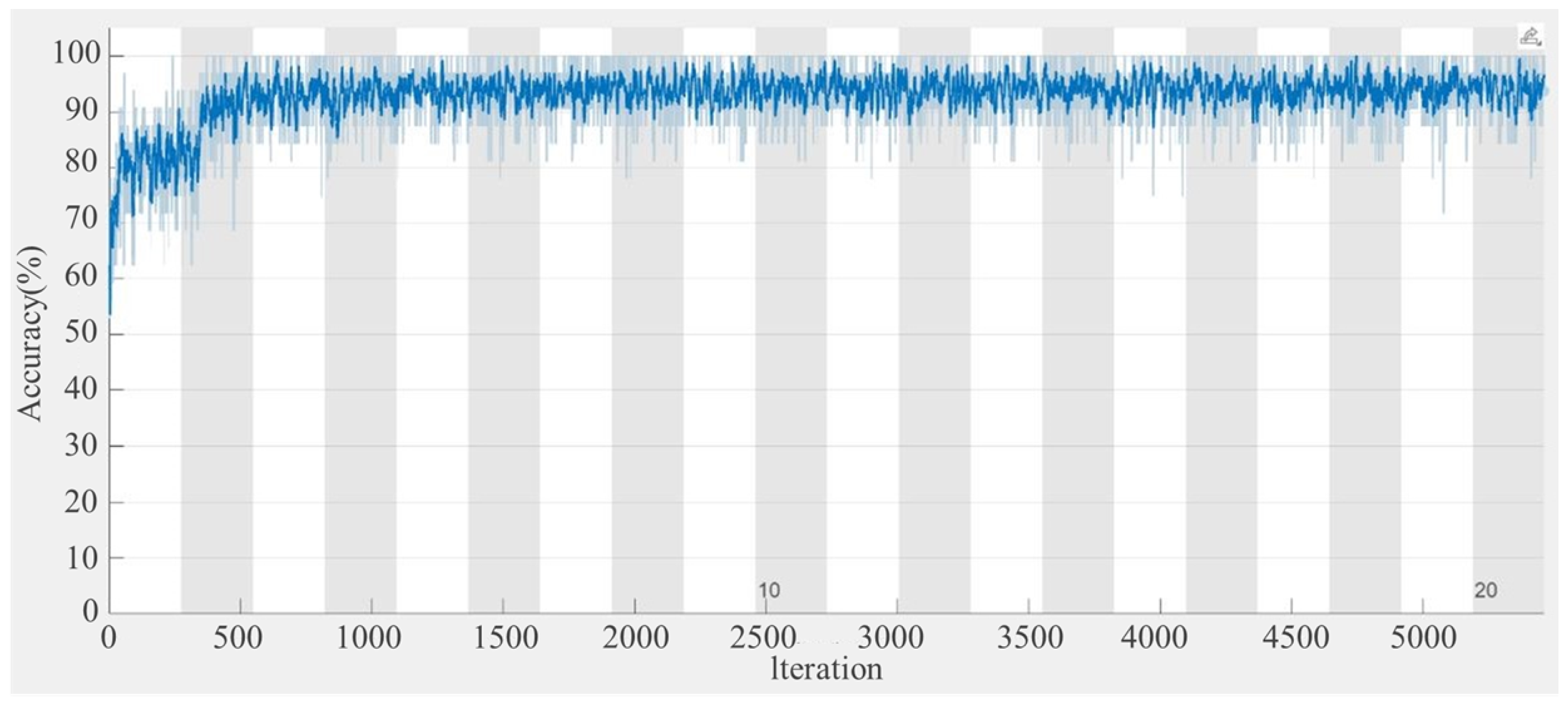

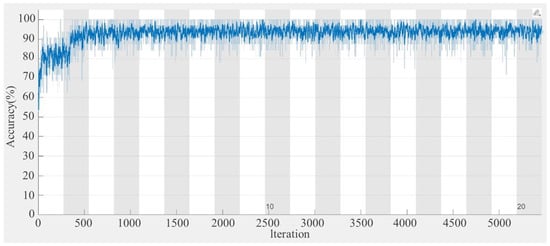

The training performance of the proposed convolutional LSTM network with ELP correlation IQ inputs is illustrated in Figure 5. The accuracy has a rapid increase within the first 500 iterations, reaching approximately 90%, and subsequently converges to around 95%. This trend suggests that the developed network structure learns NLOS features and converges to a stable performance level to be further tested.

Figure 5.

Training performance of the proposed convolutional LSTM network using a window length of 500.

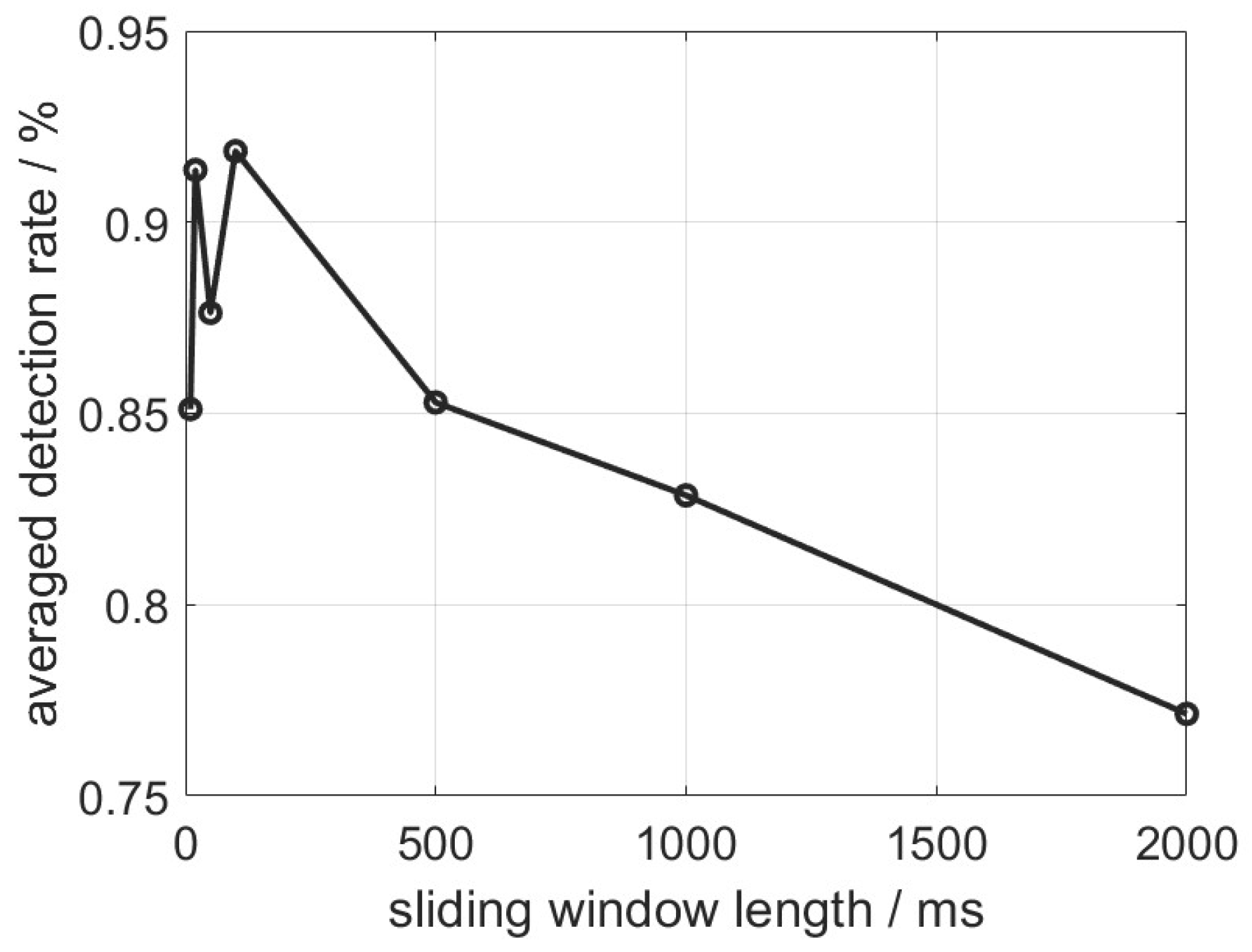

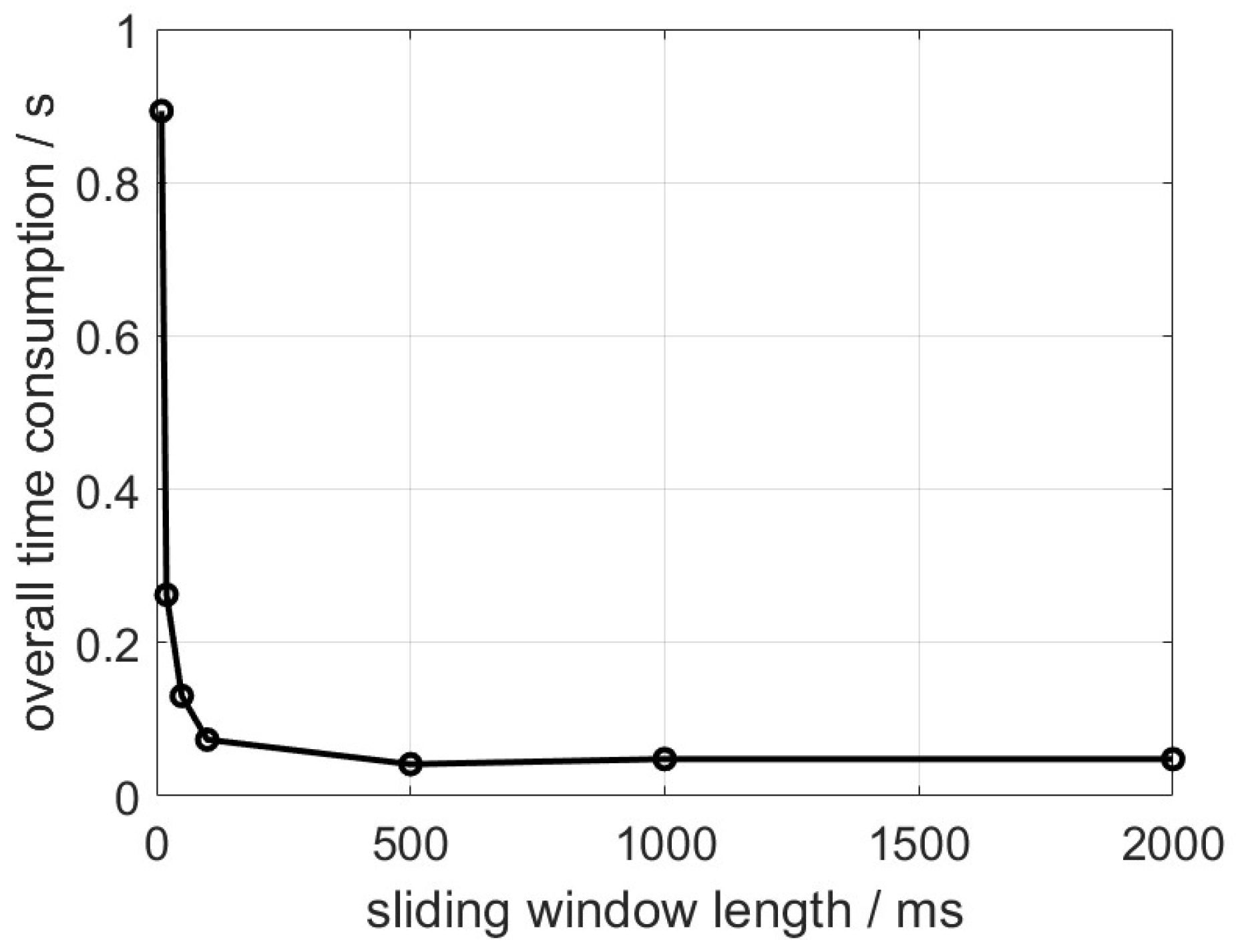

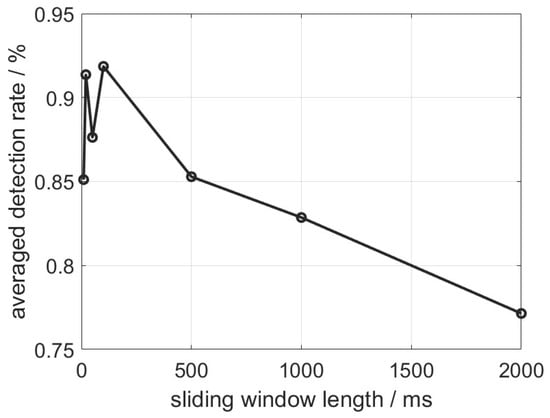

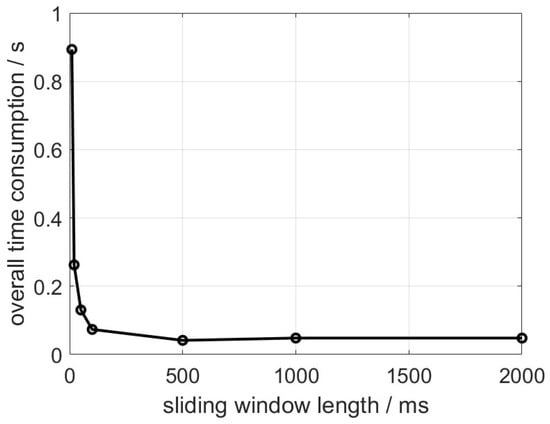

We repeat the training and testing process 10 times with the same datasets to average the performance indicator values. It is found that the length of the window size, which determines how much data is included in each training or testing instance, can significantly impact detection performance. A larger window size implies a broader perception with longer time sequence data, but it does not necessarily enhance detection performance under fixed resolution. This observation highlights the importance of optimizing the window size based on specific application requirements to achieve optimal performance in NLOS detection. Figure 6 depicts the NLOS detection accuracy in terms of correct detection probability versus the sliding window length. Figure 7 depicts the time consumption of executing a fixed-length testing dataset when the sliding window length varies.

Figure 6.

NLOS detector accuracy versus sliding window length.

Figure 7.

NLOS detector time consumption versus sliding window length.

From Figure 6 and Figure 7, it is found that the detection rate presents two peaks (over 90% detection rate) when the sliding window length is 20 and 100 samples. The detection rate starts degrading since the sliding window length increases from 100 samples, meaning that the NLOS discrimination degrades with redundant perception regions. The time consumption curve drops by more than 80% when the sliding window increases from 20 to 100 samples. The tuning of the sliding window length is therefore a tradeoff problem for balancing the detection accuracy and computation complexity.

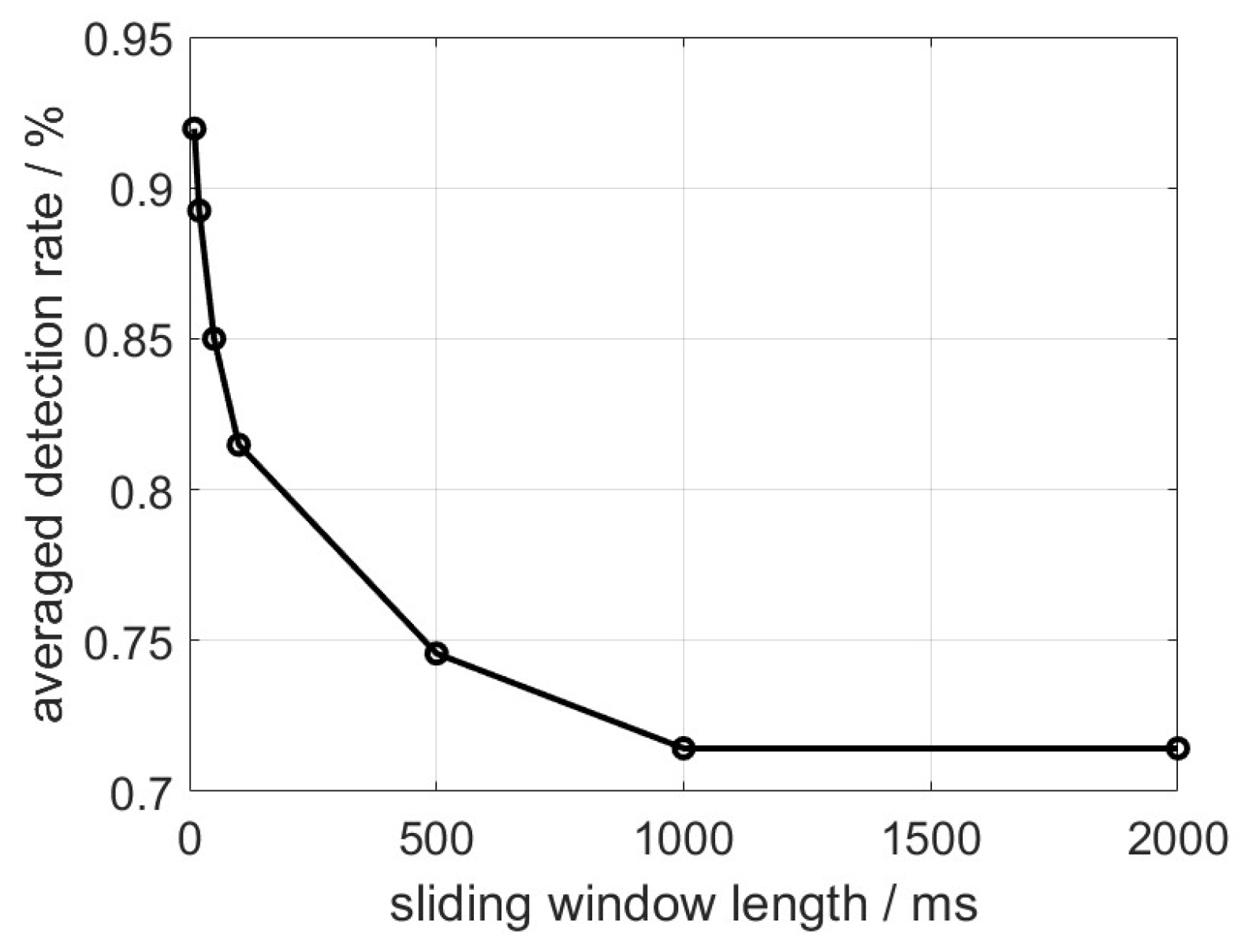

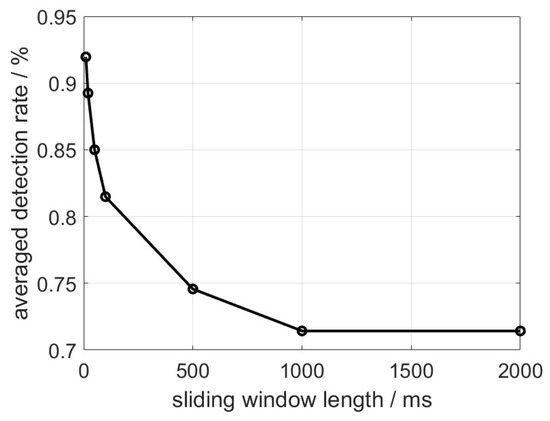

It is well-recognized that deep learning approaches are vulnerable to adversarial examples or perturbations if overfitted, and therefore the sensitivity evaluation of the proposed method against samples excluded from the training dataset becomes important. In this test, one NLOS channel is not included in the training process but is instead included in the testing dataset to assess the generalization capability of the model. This approach helps evaluate how well the model can perform on unseen data and provides insights into its robustness and generalization beyond the training dataset. The detection rate result is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

NLOS detector accuracy with inclusion of untrained testing dataset.

From Figure 8, it can be seen that the detection rate starts degrading more rapidly with the increment of the sliding window length than in Figure 6. These findings suggest that short-term NLOS features reveal greater robustness against unknown testing scenarios. Specifically, the peak value of the detection rate remains consistently above 90% when using a sliding window length of 10 samples. This demonstrates the model’s strong generalization capability, particularly when faced with other NLOS channels that were not included in the training dataset.

4. Conclusions

To detect NLOS phenomena in the GNSS receiver for selecting high-quality satellite channels, this paper proposes a deep learning-based NLOS detector scheme using ELP correlation outputs. The deep learning architecture adopts three CNNs running in parallel for the spatial perception of correlation discrimination, followed by a recurrent network of LSTM for temporal extraction of sequence samples, and end-to-end tuning of parameters. The performance valuation is performed using HIL tests aligned with a Spirent GNSS simulator to provide true labels of NLOS channels. The simulation results suggest the high performance of the proposed NLOS detection using early-stage correlations in terms of accuracy and sensitivity. By varying the sliding window length, the optimal sample length for individual training or testing instances is determined to balance accuracy and operational complexity. Sensitivity analysis confirms the model’s strong generalization capability, maintaining a detection rate of over 90% even when including untrained NLOS channels in the testing dataset. This highlights the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed deep learning approach for NLOS detection in GNSS receivers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and I.P.; methodology, Z.X. and I.P.; software, Z.X.; validation, Z.X.; formal analysis, Z.X.; data curation, Z.X.; writing, Z.X., I.P., A.T., P.P., S.T., M.B. and N.G.; supervision, I.P., A.T., M.B. and N.G.; project administration, I.P., A.T., M.B. and N.G.; funding acquisition, I.P., A.T., M.B. and N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was performed under the ESA-funded project VTL4AV (NAVISP-EL1-066 bis).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Author Pekka Peltola, Author Smita Tiwari, and Author Martin Bransby were employed by the company Telespazio UK. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tabassum, T.E.; Xu, Z.; Petrunin, I.; Rana, Z.A. Integrating GRU with a Kalman Filter to Enhance Visual Inertial Odometry Performance in Complex Environments. Aerospace 2023, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.T.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. NLOS correction/exclusion for GNSS measurement using RAIM and city building models. Sensors 2015, 15, 17329–17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, E. GPS first path detection network based on mlp-mixers. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 7764–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Amano, Y. NLOS multipath classification of GNSS signal correlation output using machine learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Groves, P.D. NLOS GPS signal detection using a dual-polarisation antenna. GPS Solut. 2014, 18, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.T.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. 3D building model-based pedestrian positioning method using GPS/GLONASS/QZSS and its reliability calculation. GPS Solut. 2016, 20, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, L.; Ziebart, M.K. Intelligent urban positioning using multi-constellation GNSS with 3D mapping and NLOS signal detection. In Proceedings of the 25th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2012), Nashville, TN, USA, 17–21 September 2012; pp. 458–472. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P.D.; Jiang, Z. Height aiding, C/N0 weighting and consistency checking for GNSS NLOS and multipath mitigation in urban areas. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastide, F.; Akos, D.; Macabiau, C.; Roturier, B. Automatic gain control (AGC) as an interference assessment tool. In Proceedings of the 16th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GPS/GNSS 2003), Portland, OR, USA, 9–12 September 2003; pp. 2042–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, G.; Yang, B.; Hsu, L.T. Machine Learning in GNSS Multipath/NLOS Mitigation: Review and Benchmark. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2024, 39, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Predict Oil Production with LSTM Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Networks, Changsha, China, 18–20 October 2019; pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Petrunin, I.; Tsourdos, A. Identification of Communication Signals Using Learning Approaches for Cognitive Radio Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 128930–128941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A. Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 385, pp. 1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Chen, K.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Hou, B.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, G.; Wang, Z. Pedestrian trajectory prediction based on deep convolutional LSTM network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 3285–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borré, A.; Seman, L.O.; Camponogara, E.; Stefenon, S.F.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.d.S. Machine fault detection using a hybrid CNN-LSTM attention-based model. Sensors 2023, 23, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borre, K.; Fernández-Hernández, I.; López-Salcedo, J.A.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.H. GNSS Software Receivers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).