Abstract

To address the critical problem of 3D object detection in autonomous driving scenarios, we developed a novel digital twin architecture. This architecture combines AI models with geometric optics algorithms of camera systems for autonomous vehicles, characterized by low computational cost and high generalization capability. The architecture leverages monocular images to estimate the real-world heights and 3D positions of objects using vanishing lines and the pinhole camera model. The You Only Look Once (YOLOv11) object detection model is employed for accurate object category identification. These components are seamlessly integrated to construct a digital twin system capable of real-time reconstruction of the surrounding 3D environment. This enables the autonomous driving system to perform real-time monitoring and optimized decision-making. Compared with conventional deep-learning-based 3D object detection models, the architecture offers several notable advantages. Firstly, it mitigates the significant reliance on large-scale labeled datasets typically required by deep learning approaches. Secondly, its decision-making process inherently provides interpretability. Thirdly, it demonstrates robust generalization capabilities across diverse scenes and object types. Finally, its low computational complexity makes it particularly well-suited for resource-constrained in-vehicle edge devices. Preliminary experimental results validate the reliability of the proposed approach, showing a depth prediction error of less than 5% in driving scenarios. Furthermore, the proposed method achieves significantly faster runtime, corresponding to only 42, 27, and 22% of MonoAMNet, MonoSAID, and MonoDFNet, respectively.

1. Introduction

Autonomous driving has attracted increasing attention for its potential to reduce driver workload and improve driving safety [1]. In modern autonomous driving systems, the perception system is an indispensable component, tasked with accurately assessing the surrounding environment and further enabling prediction and planning processes.

3D object detection plays a crucial role in this context by predicting the positions, dimensions, and classes of key objects (such as vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists) within the 3D space, serving as one of the critical information sources for the perception system. Common 3D detection technologies primarily rely on light detection and ranging (LiDAR), stereo cameras, or integrated multi-source sensors at the sensor hardware level, but these methods each have their limitations. For example, LiDAR is expensive, and its accuracy decreases at long distances. Radar lacks fine shape and category recognition capabilities. Stereo cameras require complex stereo matching computations. While monocular cameras have the advantages of low cost and easy deployment, it is difficult to analyze depth information from a single image. A single monocular image yields lower detection accuracy than other sensors, whereas integrating multiple sensors improves accuracy but increases computational cost [2].

At the software-model level, as deep-learning technology advances, deep-learning-based 3D object detection has gradually become a highly anticipated research focus. Although many studies [3,4,5] have proposed various methods to improve the detection accuracy of convolutional neural networks, the black-box nature of deep-learning models renders their decision-making process poorly interpretable [6]. The model’s generalization ability also heavily relies on the diversity and quality of the training data. To ensure reliable operation across common scenarios, the model requires large, diverse, and accurately labeled datasets [6].

However, real autonomous driving scenarios include a wide range of camera specifications, drivers, road sections, and weather conditions. Even with the continuous expansion of the training dataset, it remains difficult to cover all possible driving situations. Camera-based monocular 3D detection still struggles to estimate 3D positions because single images lack dependable depth cues. Recent studies have addressed this issue through loss-level optimization and adaptive depth modeling. For example, MonoAMNet [3] introduces a three-stage pipeline with adaptive modules to dynamically adjust receptive fields, sample selection, and loss weights. MonoSAID [4] converts continuous depth into adaptive, scene-level variable-width bins, integrating global and local features through a pyramid attention mechanism. MonoDFNet [5] adds a weight-sharing multi-branch depth head for near, medium, and distant objects, fuses these depth cues with RGB features via adaptive-focus attention, and adopts a penalty-reduced focal loss for more stable optimization. Nevertheless, these methods still depend on depth distributions or hyperparameters derived from specific training datasets, highlighting their limitations in generalization to unseen scenarios.

A traffic digital twin (TDT) has recently been recognized as a core enabling technology of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) [7]. The concept of digital twins [8] comprises three key components: (1) physical objects in the real world, (2) their virtual counterparts in cyberspace, and (3) bidirectional data connections between them. A canonical TDT pipeline comprises four consecutive stages: (1) data collection by multi-sensor suites embedded in vehicles and roadside units, (2) real-time data synchronization through Vehicle-to-Everything links, (3) continuous monitoring, analysis, and simulation in cyberspace, and (4) optimization of transport operations.

In this study, we focused on Stage 1. By providing real-time updates of dynamic objects and generating accurate 3D visualizations of driving scenes, we deliver a high-fidelity digital replica that supplies trustworthy input for the subsequent synchronization, simulation, and optimization stages. Consequently, the proposed monocular pipeline not only advances 3D object detection itself but also serves as a crucial data-ingestion module for TDT-driven ITS.

To address these limitations and capitalize on the hardware advantages of cameras, we combined AI models with lens-optics-based algorithms and developed a 3D object detection method and digital twin architecture that achieves low computational cost and high generalization ability. Compared with deep-learning-based 3D object detection methods [3,4,5], the architecture presents advantages described Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the proposed AI-enhanced mono-view geometry method with traditional deep-learning-based work.

2. AI-Enhanced Mono View Geometry Method

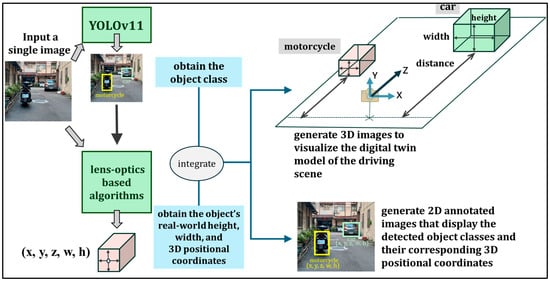

Figure 1 presents a digital twin diagram of the proposed system. Given a single image and a small set of known geometric parameters, geometric optics algorithms estimate each object’s true physical height and 3D position, and the YOLOv11 object detection model [9] identifies object categories. Finally, we construct a digital twin model that allows the system to reconstruct its 3D surroundings in real time across diverse environments.

Figure 1.

The digital twin diagram of this study.

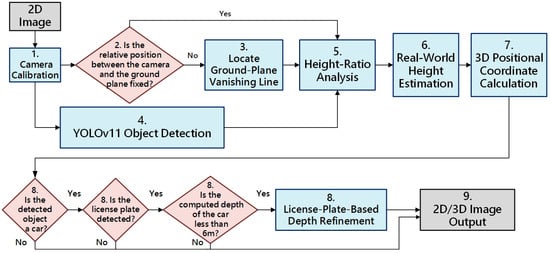

Figure 2 shows the algorithm flowchart, with each step detailed below.

Figure 2.

The algorithm flowchart of this study.

- Camera calibration: Using the OpenCV camera calibration code and workflow [10], we obtain the camera’s distortion coefficients and intrinsic calibration matrix, which are saved to a .pkl file. All subsequent steps can load this file to rectify images from the same lens and then apply the series of operations defined by the 3 × 3 calibration matrix K, where is the focal length of the camera, and is the principal point, i.e., the intersection of the optical axis with the image plane (near the image center).

- 2.

- Reuse the vanishing line under a fixed pose: If the relative pose between the camera and the ground plane remains fixed (i.e., the camera only translates along its Z-axis or rotates about its Y-axis), the vanishing line computed from the ground-plane normal need not be recomputed. In that case, skip step 3 and proceed directly to step 4.

- 3.

- Locate Ground-plane Vanishing Line: Let the ground-plane normal be . The corresponding vanishing line in the image coordinate system is then

If we take the camera center as the origin of the world coordinate system, no additional extrinsic rotation or translation needs to be considered.

- 4.

- YOLOv11 object detection: Feed the rectified 2D image into YOLOv11 to detect object classes and their 2D bounding boxes, and from each box, compute the object’s image height.

- 5.

- Height ratio analysis: For each detected object on the ground plane, obtain its image height and use the vanishing line from Step 3 to compute the object’s real-world height ratio [11].

- 6.

- Real-world height estimation: Using a reference object with a known real-world height that stands perpendicular to the ground plane, together with the height ratios from the previous step, compute each target object’s true height .

- 7.

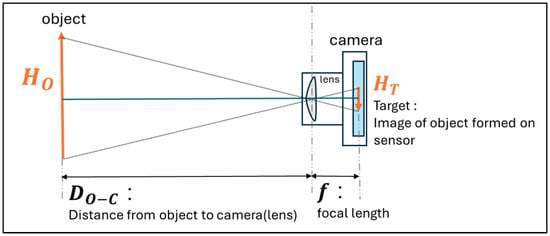

- 3D positional coordinate calculation: As shown in Figure 3, given the camera focal length f, the object’s image height , and its real height , the object-to-camera distance follows by similar triangles:

Figure 3. Similar triangles are formed by the pinhole camera projection model.

Figure 3. Similar triangles are formed by the pinhole camera projection model.

To recover the 3D coordinates of any image point , we use Equation (4) in which is substituted to obtain each object’s in the camera coordinate system.

- 8.

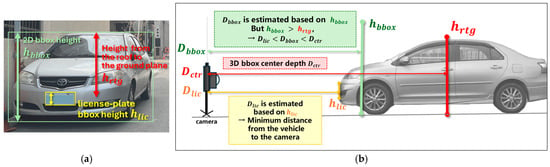

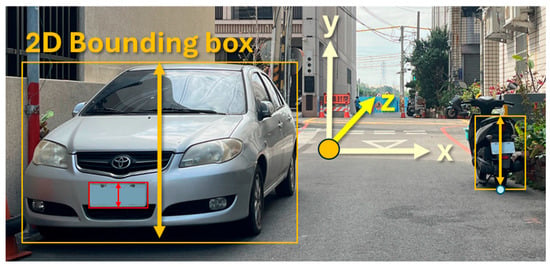

- License-plate-based depth refinement: As illustrated in Figure 4a,b, in close-range scenes, perspective distortion causes the car bounding box (green box) to include both the roof and the hood, resulting in an observed height (green arrow) that is greater than the ideal height (red arrow), which represents the true vertical span from the roof to the ground in the image. Using this overestimated height to compute depth yields an inaccurate result, often placing somewhere between the front bumper and the actual center of the vehicle . To resolve this, we detect the license plate (yellow box) within the car’s 2D bounding box; if successful, we take the license plate box height as the new image-space reference height , and use the standard physical height of a license plate ( = 16 cm in Taiwan) to recompute depth using a similarity triangle formulation. This yields a refined depth estimate , which reflects the minimum distance from the vehicle to the camera, and replaces the original depth value to improve 3D localization accuracy in close-range scenes.

Figure 4. (a) Perspective distortion inflates , causing inaccurate depth estimation. (b) Using the license plate height yields a refined, closer depth .

Figure 4. (a) Perspective distortion inflates , causing inaccurate depth estimation. (b) Using the license plate height yields a refined, closer depth . - 9.

- 2D/3D image output: Finally, we output 2D annotated images that display each detected object’s class and its 3D positional coordinates, and 3D renderings visualizing the driving-scene digital twin model.

3. Results

In the experiment, a real road was used as the scene, and the main camera of an Apple iPhone 13 served as the imaging device. The phone was mounted on a tripod so that the lens was 108 cm above the ground plane. During capture, the camera was held with zero rotation about the X-axis (pitch = 0°) and Z-axis (roll = 0°), and was only translated along its Z- or X-axis. Under these conditions, the ground plane can be treated as the XZ-plane of the camera coordinate system, with a unit normal vector of . As shown in Figure 5, the car and motorcycle were selected as the measurement objects. The camera was translated along the Z- and X-axes while both vehicles remained stationary, and a total of four photographs were taken.

Figure 5.

Real-road experimental scenario using a monocular camera.

At the time of each shot, we recorded the real-world heights of the car and motorcycle in Table 2 and the depth distances between the camera and each object in Table 3, which served as the ground truth for evaluating depth estimation. Using the motorcycle as the reference object of known real-world height, the height ratio analysis method was applied to estimate the car’s actual height and to compute the 3D coordinates of both objects in the camera coordinate system.

Table 2.

Ground-truth physical heights of the reference motorcycle and the target car.

Table 3.

Ground-truth depth distances from the camera to the motorcycle and car.

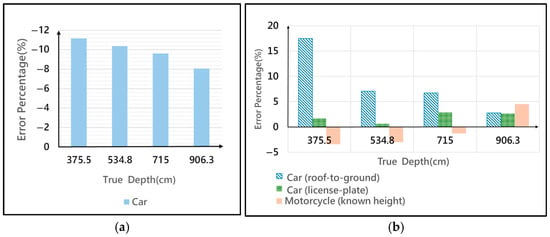

Figure 6a illustrates the estimation of the car’s height using the height ratio analysis method with the motorcycle’s real height. The height error percentage is computed using Equation (5).

Figure 6.

(a) Error Percentage for Real-World Object Height Estimation; (b) Error Percentage for Depth Estimation.

As shown in Figure 6a, when the object’s distance to the camera decreases, the relative error percentage in estimating the car’s true height increases. This effect is because we use only the 2D bounding box height as the image height , but the bounding box height does not precisely correspond to the actual roof-to-ground height. Moreover, at closer ranges, stronger perspective distortion exacerbates the discrepancy between the estimated and true heights. Figure 6b presents the relative error percentage in depth prediction for both the motorcycle and the car, calculated using Equation (6).

For the motorcycle, the predicted depth is obtained by substituting its real height into the pinhole-camera similarity-triangle formula at step 7. For the car, two methods are compared:

- Roof-to-ground: Use the 2D bounding box height as the image height , and then apply the height ratio analysis to estimate the car’s actual height, which is the value of for depth computation.

- License plate: Use the license plate height as and the known plate height (16 cm) as to compute depth accordingly.

In Figure 6b, at depths of 375.5 cm, 534.8 cm, and 715 cm, the license plate method yields depth estimates that more accurately match the car’s front-most point, exhibiting lower error percentages than the roof-to-ground method. However, at a greater depth of 906.3 cm, the license plate approach provides almost the same error percentage as the roof-to-ground method.

For runtime evaluation, the proposed runtime pipeline comprises three stages: (1) object detection with YOLOv11, (2) license plate detection applied only to the car proposals, and (3) lightweight geometric computation. Public benchmarks report that YOLOv11-n running under NVIDIA TensorRT/FP16/RTX 3080 achieves an average inference time of 0.62 ms per 640 × 640 image [12]. A YOLOv5-based license plate detector, evaluated on an RTX 3080, processes an image in approximately 3.7 ms [13]. The subsequent geometric calculations execute less than 0.1 ms on the graphics processing unit, which can be neglected in practice. Consequently, the overall runtime ranges from 1 ms to 8 ms per frame. The 8 ms upper bound reflects the worst-case scenario with two close-range vehicles requiring license plate detection (0.62 + 3.7 × 2 = 8.02 ms). By comparison, deep-learning-based monocular 3D detector methods require substantially longer runtimes: MonoAMNet (19 ms), MonoSAID (30 ms), and MonoDFNet (36 ms). Thus, our method achieves more than twice the execution speed of MonoAMNet, nearly four times the speed of MonoSAID, and over 4.5 times the speed of MonoDFNet, which corresponds to only 42%, 27%, and 22% of their respective runtimes, without compromising depth estimation accuracy. This makes it particularly well-suited for real-time deployment on cost-sensitive in-vehicle edge devices.

In summary, the developed AI-enhanced monocular geometry architecture achieves a depth error of less than 5% across all evaluated poses and object types, demonstrating high accuracy with low computational complexity. To balance precision and real-time performance, we recommend applying the license-plate-based depth refinement in close-range scenarios, where perspective distortion is significant, while omitting it at longer distances to reduce processing overhead.

4. Conclusions

We developed a 3D object detection architecture that fuses AI with camera optical techniques to deliver a low-cost, highly interpretable digital twin visualization system from monocular images. A key innovation is a height ratio analysis method based on the ground-plane vanishing line, which estimates an object’s real-world height and 3D position directly—without deep-learning models—thus overcoming the inherent lack of depth information in single images. In close-range scenarios, we further refine vehicle depth estimation by detecting license plates and using their standard dimensions as a reference, significantly improving accuracy.

Experiment results on real-road scenes show that the architecture achieves less than 5% of the depth estimation error and less than 42% of the runtimes of three traditional methods, confirming both the feasibility of our method and the value of fusing vanishing-line and license plate cues in real-time deployment. The architecture demands low computational resources and generalizes well, making it ideal for resource-constrained vehicle and smart-surveillance systems. Future work will integrate multi-temporal imagery and real-time vehicle-to-everything communication to further boost scene understanding and dynamic-prediction accuracy, unlocking applications in intelligent transportation and autonomous driving.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-C.C. and C.K.; methodology, I.-C.C., Y.-C.C. and C.K.; software, Y.-C.C.; validation, I.-C.C., C.K. and C.-E.Y.; formal analysis, I.-C.C. and C.K.; resources, C.-E.Y.; data curation, Y.-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-C.C., I.-C.C. and C.-E.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.-C.C., I.-C.C. and C.-E.Y.; supervision, I.-C.C. and C.-E.Y.; project administration, I.-C.C. and C.-E.Y.; funding acquisition, I.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, grant number NSTC 114-2221-E-018-020. The APC was funded by NSTC 114-2221-E-018-020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yan, L.; Wu, X.; Wei, C.; Zhao, S. Human-Vehicle Shared Steering Control for Obstacle Avoidance: A Reference-Free Approach with Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 17888–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. 3D Object Detection for Autonomous Driving: A Comprehensive Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2023, 131, 1909–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Jia, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, W. MonoAMNet: Three-Stage Real-Time Monocular 3D Object Detection with Adaptive Methods. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 3574–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhao, W.; Han, H.; Tao, Z.; Ge, B.; Gao, X.; Li, K.-C.; Zhang, Y. MonoSAID: Monocular 3D Object Detection Based on Scene-Level Adaptive Instance Depth Estimation. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Sun, M.; Di, R.; Li, L.; Hong, W. MonoDFNet: Monocular 3D Object Detection with Depth Fusion and Adaptive Optimization. Sensors 2025, 25, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and CNN-Based Object Recognition Techniques in Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chongqing, China, 20–22 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ge, S.; Luo, G.; Tian, Y.; Ye, P.; Li, Y. Internet of Vehicular Intelligence: Enhancing Connectivity and Autonomy in Smart Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Fogli, D. A Survey on Digital Twin: Definitions, Characteristics, Applications, and Design Implications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167653–167671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV: Camera Calibration. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.x/dc/dbb/tutorial_py_calibration.html (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Hartley, R.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. Integrations—TensorRT: NVIDIA A100. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/integrations/tensorrt/#nvidia-a100 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Agrawal, S. Global License Plate Dataset. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).