Abstract

This study aims to explore how digital transformation (DT) accelerates the achievement of net zero (NZ) goals within Taiwan’s green energy industry. By employing quality function deployment as the analytical framework and multiple-attribute decision making for systematic evaluation, a practical and integrative model is developed to identify key DT technologies. The results reveal that establishing a comprehensive carbon footprint management system is the most essential NZ strategy, while Radio-Frequency Identification emerges as the most influential DT enabler supporting sustainability, emission reduction, and industrial transformation toward a smart and low-carbon economy.

1. Introduction

In the process of industrialization, energy consumption is an inevitable material input and holds a critical position in economic development [1,2]. However, the global dependence on fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas has led to significant environmental damage and air pollution [3]. Effectively reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is a pressing challenge in addressing current global climate change [4]. Thus, global climate policies are now focused on a new goal: achieving net zero (NZ) emissions. Over 100 countries, including the European Union, China, and Japan, have established or are in the process of developing carbon neutrality or NZ goals [4]. Taiwan, in March 2022, announced its 2050 NZ pathway, committing to achieving NZ climate goals by 2050.

The international community is actively working to ensure that the global temperature does not exceed 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels [5]. Governments worldwide are striving to formulate various solutions to achieve this goal, aiming for more sustainable future development. Digitization is recognized as a crucial strategy to accelerate progress toward Sustainable Development (SD) [6]. Industries are exploring digital transformation (DT) technologies as solutions for SD [7].

The global pursuit of NZ has become a significant guide for corporate SD [8]. Exploring how to effectively use DT to reduce carbon footprint [9], enhance energy efficiency [10], and promote the use of green energy in the wave of NZ is a crucial research topic. Understanding how DT and NZ can be practically integrated, constructing an evaluative integration model, is urgently needed. This study aims to delve into the relationship between DT and NZ, identifying key tools to achieve NZ goals. The green energy industry is chosen as the research subject due to its forefront position in NZ, with its effectiveness impacting overall NZ efficiency.

To achieve this goal, this study initially conducted a comprehensive review of the relevant literature and sought opinions from multiple experts in the Section 2. From the literature on DT and NZ, various strategies and technologies were identified. The Section 3 elucidates the utilization of the quality function deployment (QFD) method, specifically the house of quality (HoQ), to analyze the relationship between DT and NZ. Fuzzy logic within the multiple-attribute decision making (MADM) framework, along with the technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS), was employed to clarify which tools could enhance key DT technologies for achieving NZ. The Section 4 focuses on empirical research within the Taiwanese green energy industry, and the Section 5 presents conclusions and recommendations.

2. Literature Review

DT is defined as the comprehensive overhaul of processes, products, and services through the utilization of digital technologies to meet customer needs and create value [11]. This involves the integration of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies, triggering significant changes to physical entities [12].

NZ emissions, as defined, aim to offset greenhouse gas emissions generated during industrial production and the energy conversion process of fossil fuels by human removal to achieve a net result of zero [13]. In other words, NZ does not imply complete elimination of emissions but rather a substantial reduction in human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. Unavoidable emissions are addressed through negative carbon technologies such as carbon capture and storage [14]. This study categorizes NZ strategies into system and technology aspects, emphasizing comprehensive management on the system side and innovative solutions on the technology side. This classification aids in the holistic understanding of NZ emission strategies, highlighting the synergistic interaction between systemic and technological tools.

The achievement of NZ requires a comprehensive transformation from energy usage and production processes to supply chains, driving organizations to expedite digitization [7]. The literature review indicates that the integration of DT and NZ generates synergistic effects.

The use of digital technologies helps businesses achieve energy efficiency, optimize production processes, and reduce carbon emissions. The combined application of these technologies not only helps organizations achieve NZ goals but also ensures their sustainable competitiveness in a fiercely competitive market. Therefore, through a comprehensive literature review and discussions with industry experts, this study gathered various DT technologies and NZ strategies, culminating in a compilation of 14 DT technologies and 10 NZ strategies.

The following introduces each DT technology and NZ strategy, with codes assigned: Software systems (including Enterprise Resource Planning, Customer Relationship Management, etc.) (DT01); Big Data Analytics (DT02); Internet of Things (DT03); Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Mixed Reality (MR) (DT04); Smart Grid (DT05); Machine-to-Machine (M2M) and Human-to-Machine (H2M) Communication (DT06); Data Simulation (DT07); Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) (DT08); Cloud Computing (DT09); Human–Machine Collaboration (HMC) (DT10); Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (DT11); Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (DT12); Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) (DT13); Product Cloud Services (DT14); carbon footprint management system (NZ01); Energy Management System (NZ02); Supply Chain Management System (NZ03); Information Security Management System (NZ04); Electric Vehicle Fleet Management System (NZ05); Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence (NZ06); Digital Production Technologies (NZ07); Blockchain (NZ08); Lean Production (LP) (NZ09); and Karakuri (NZ10). Table 1 provides a literature review of DT technologies, and Table 2 presents a literature review of NZ strategies.

Table 1.

DT technologies in the literature.

Table 2.

Literature review of NZ emission strategies.

3. Method

In this study, fuzzy logic, QFD, and TOPSIS are integrated to propose a quantitative evaluation model. Firstly, the NZ strategies and DT technologies will be analyzed using QFD’s HoQ. The calculation of NZ strategy weights will employ fuzzy logic for semantic assessment. Subsequently, combined with TOPSIS, it will provide a prioritized ranking of key DT technologies.

3.1. Fuzzy Logic

Reference [39] proposed fuzzy set theory for handling fuzzy events. Members of a fuzzy set can have different degrees of membership ranging from 0 to 1. The set can also have an infinite number of membership functions; thus, fuzzy sets are more suitable than ordinary sets for the analysis of real-world nonlinear systems. The fuzziness of expert semantic assessments and the interrelationships between criteria are considered. By incorporating fuzzy logic with QFD, the decision making process is aligned more closely with real-world conditions.

Fuzzy logic often involves the uses of semantic variables. Common semantic variables include triangular, trapezoidal, and Gaussian fuzzy numbers. In fuzzy logic, specific semantic evaluations are used to define corresponding membership functions. Semantic variables, which can be used as a basis for thinking and making judgments, are based on words or texts in natural languages rather than data. The semantic variables of fuzzy weight values and their corresponding positive triangular fuzzy numbers are presented in Table 3. Triangular fuzzy numbers, as shown in Figure 1, are denoted by , where , and for to be a positive triangular fuzzy number.

Table 3.

Fuzzy weights and semantic variables.

Figure 1.

Triangular fuzzy number.

If two triangular fuzzy numbers = (, , ) and = (, , ) exist and the fuzzy values of and are greater than 0, then the following expressions are true.

The relative distance formula [40] is used for defuzzification. The equation is as follows.

where and . represent the best fuzzy value, and represents the worst fuzzy value. According to the above equation, if R = 1, it implies that = 0, indicating that the distance between the fuzzy number and is zero, meaning that the fuzzy number is the best value. If R = 0, then = 0, indicating that the distance between the fuzzy number and is zero, meaning that the fuzzy number is the worst value. Using this transformation formula, the fuzzy assessment value can be defuzzified (denoted as ) as follows.

where , represents the best fuzzy value , and represents the worst fuzzy value .

3.2. QFD

QFD was formulated by Japanese scholars Yoji Akao and Shigeru Mizuno in the 1960s. The primary function of QFD is to transform customer demands into appropriate technological requirements during the product development and manufacturing phases [41]. Originally employed to translate customer requirements into product designs with the aim of enhancing customer satisfaction, QFD’s application extends to converting customer demands into engineering characteristics of the product [42]. In recent years, QFD has become a tool frequently used to address MADM problems.

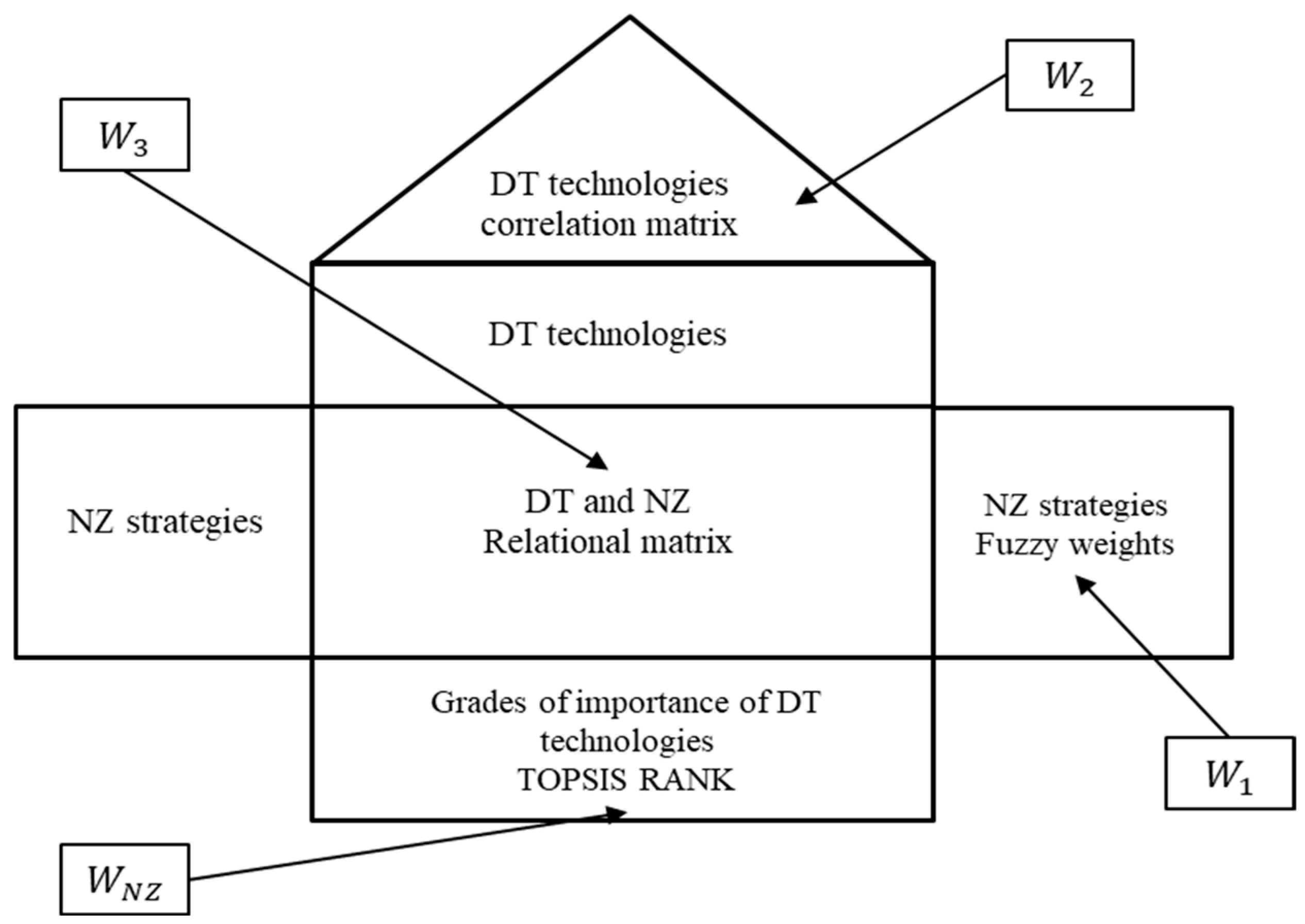

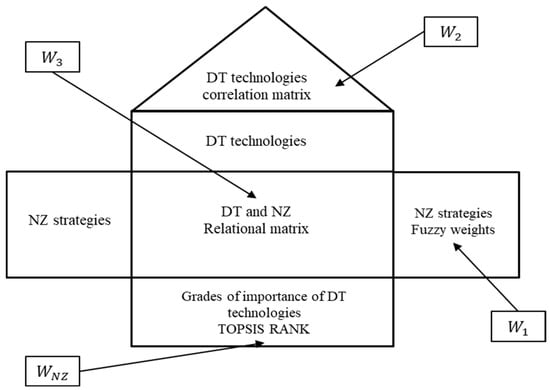

HoQ of QFD is applied to construct the correlation between NZ strategies and DT technologies. The detailed structure of the HoQ is shown in Figure 2, and the steps of the HoQ are as follows:

Figure 2.

Organizational chart of the house of quality in this study.

- Step 1: Obtain the weight of NZ strategies (W1). In this study, a questionnaire survey is conducted using the fuzzy semantic measurement method. Fuzzy logic is employed to derive the importance matrix (W1) for NZ strategies. The matrix contains the weights of NZ strategies, where i = 1, 2, … n.

- Step 2: Establish the correlation matrix (W2) for DT technologies and the relational matrix (W3) between DT technologies and NZ strategies, assessed by domain experts. Respondents evaluate the degree of correlation between DT technologies using a fuzzy evaluation scale (where represents low correlation, moderate correlation, high correlation).

- Step 3: Obtain the Integrated Relationship Matrix (WNZ) by synthesizing the correlation matrix (W2) and the relationship matrix (W3).

3.3. Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution

The method’s advantages lie in its ease of understanding, consideration of both positive and negative factors, accounting for the relative importance of criteria, and its ability to handle complex decision problems [43]. The TOPSIS method requires the establishment of the positive ideal solution (PIS) and negative ideal solution (NIS). PIS consists of the maximum value of benefit criteria or the minimum value of cost criteria. Conversely, NIS is composed of the minimum value of benefit criteria or the maximum value of cost criteria. The alternative that is closest to the positive ideal solution and farthest from the negative ideal solution is selected as the best alternative. The steps of the TOPSIS analysis are detailed as follows.

- Step 1: Establish the normalized evaluation matrix (R). The equation is as follows.where i is the alternative, j is the evaluation criteria, and represents alternate i in the evaluation value under j criterion.

- Step 2: Establish the normalized weight vector V, which multiplies by the normalized evaluation matrix (R) by W = (). That is,

- Step 3: Decide the PIS and NIS : Under the m evaluation alternaives and n evaluation criteria, the equations are as follows.

- Step 4: Calculate the distance of the evaluation alternatives from the positive ideal solution and negative ideal solution. According to the Euclidean distance formula, calculate the separation measure from the alternatives to PIS and NIS. Respectively calculate and as follows.

- Step 5: Calculate the relative performance indicator values.

4. Empirical Research

This empirical study focuses on the practical application of the green energy industry. To achieve this, experts from green energy-related industries were invited to participate in a questionnaire survey. The respondents have 8 to 20 years of work experience, and their job titles are at least at the manager level. The survey was designed in three ways: (1) evaluating the importance of NZ strategies; (2) assessing the correlation among DT technologies; and (3) exploring the relationship between DT technologies and NZ strategies. A total of 10 questionnaires were distributed, and all 10 were collected.

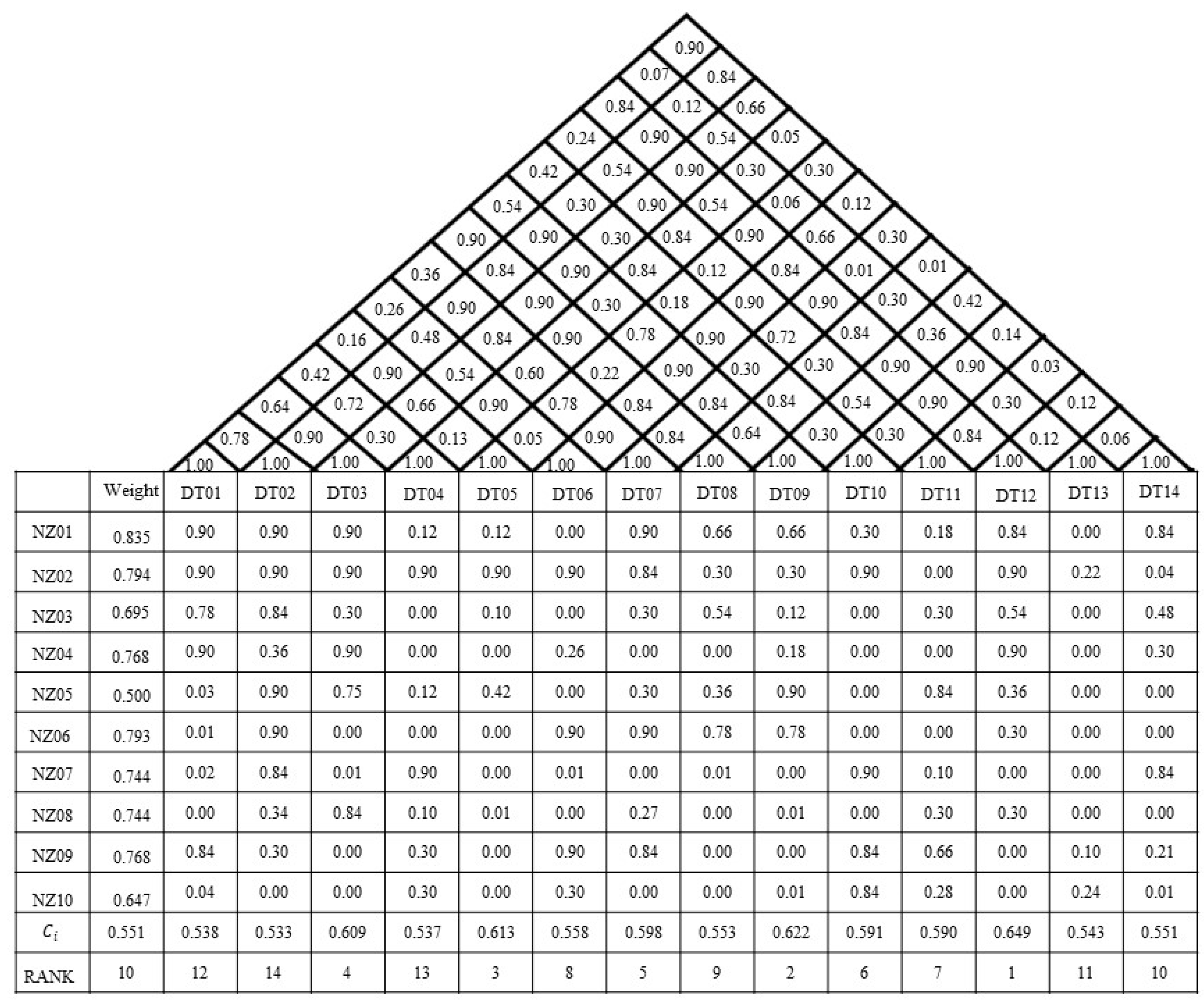

- Step 1: Obtain the NZ strategies (W1) using the method provided by fuzzy logic. Utilize Equations (1)–(5) to derive the results, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Fuzzy logic analysis results for NZ emission strategies.

Table 4. Fuzzy logic analysis results for NZ emission strategies.

- Step 2: Establish the correlation matrix of DT technologies (W2) using fuzzy logic. Integrate evaluations from 10 experts on the interrelationships among DT technologies, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Correlation matrix between digital transformation technologies.

Table 5. Correlation matrix between digital transformation technologies.

- Step 3: Construct the matrix (W3) representing the interrelationships between DT technologies and NZ strategies, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Relational matrix between NZ and digital transformation.

Table 6. Relational matrix between NZ and digital transformation. - Step 4: Calculate the integrated correlation matrix (WNZ) for DT technologies and NZ strategies; refer to Equation (6). Multiply the matrices W2 and W3 obtained in the previous steps to derive WNZ, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Integrated correlation matrix between NZ and digital transformation.

Table 7. Integrated correlation matrix between NZ and digital transformation.

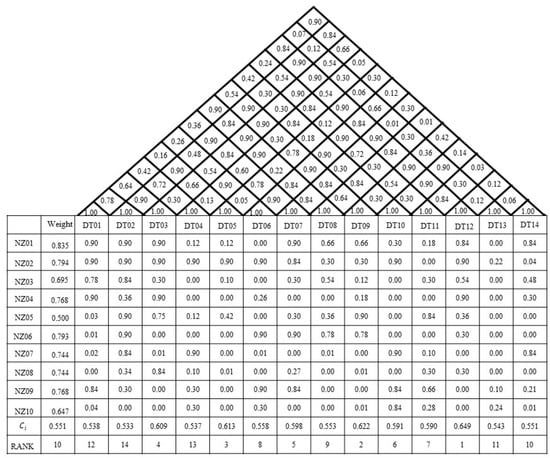

- Step 5: Prioritize the DT technologies using the TOPSIS method. Obtain the normalized matrix; refer to Equation (7) and the results presented in Table 8. Calculate the weighted normalized matrix, referring to Equation (8), with weights obtained from fuzzy logic, as shown in Table 9. Proceed to calculate the PIS and NIS; refer to Equations (9) and (10), respectively (Table 10). Then, compute the distance between each DT technology’s PIS and NIS; refer to Equations (11) and (12). Finally, calculate Ci; refer to Equation (13) and rank the technologies based on Ci values. All results are summarized in HoQ, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 8. Normalized integrated relational matrices after being weighted.

Table 8. Normalized integrated relational matrices after being weighted. Table 9. Positive ideal solutions and negative ideal solution in the association of digital transformation technologies.

Table 9. Positive ideal solutions and negative ideal solution in the association of digital transformation technologies. Table 10. Ranking of digital transformation technologies.

Table 10. Ranking of digital transformation technologies. Figure 3. Organizational chart of the house of quality.

Figure 3. Organizational chart of the house of quality.

5. Discussion of the Results

Two key findings are obtained in this study. Firstly, utilizing fuzzy logic, the importance assessment of NZ strategies is computed. The top five ranked strategies are led by the carbon footprint management system, identified as the most crucial. The following are the Energy Management System, Digitalized Production Technology, Information Security Management System, and LP. The application of these strategies substantively supports the realization of NZ in Taiwan’s green energy industry. Based on the values, critical DT technologies are identified. The research results indicate that the top five technologies are led by RFID, identified as the most crucial. Following this are HMC, then M2M and H2M, and subsequently AR, VR, and MR, and finally ML and DL.

6. Conclusions

When enterprises pursue net zero emissions, they encounter significant challenges, requiring the identification of practical measures from numerous strategies and technologies. This study explores the interaction between NZ and DT in Taiwan’s green energy sector. Using QFD, the research confirms a strong correlation between NZ and DT. Additionally, employing the MADM method, pivotal NZ strategies are identified, with the carbon footprint management system deemed the most crucial. Similarly, key DT technologies are analyzed, with RFID identified as the most vital.

The association between the carbon footprint management system and RFID in the context of NZ is elucidated as follows.

- Information collection and monitoring: The carbon footprint management system efficiently collects and monitors an organization’s carbon emissions using RFID technology for real-time product tracking. The integration of these technologies enables comprehensive data collection, aiding in the assessment and management of carbon emission sources.

- Supply chain transparency: RFID can be applied to supply chain management, enhancing the transparency of product transportation and the supply chain process. This can assist in considering broader supply chain impacts in carbon footprint management and evaluating carbon emissions.

- Production efficiency: RFID application in production enhances efficiency, while carbon footprint management systems assess the carbon benefits, aligning with green production goals.

The combination of carbon footprint management systems and RFID contributes to improving information visibility and transparency, as well as optimizing supply chain and production processes, facilitating organizations in achieving NZ goals. The results of this study provide an in-depth analysis of the significance of NZ and DT in the practice of Taiwan’s green energy industry. This demonstrates that DT serves as a framework for achieving and sustaining SD within the context of NZ. This study further offers specific strategies and technical guidance. These findings not only provide valuable references for industry decision-makers but also contribute to the industry’s practical and feasible approaches toward a more sustainable future.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan, R.O.C., under Project No. NSTC 113-2222-E-164-001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the project of the National Science Council, Taiwan (Project no. NSTC 113-2222-E-164-001). We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muradov, N. Low to Near-Zero CO2 Production of Hydrogen from Fossil Fuels: Status and Perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 14058–14088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, N.; Arif, A.; Jain, V.; Chupradit, S.; Shabbir, M.S.; Ramos-Meza, C.S.; Zhanbayev, R. The Role of Technological Innovation in Environmental Pollution, Energy Consumption and Sustainable Economic Growth: Evidence from South Asian Economies. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 39, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Smith, S.M.; Allen, M.; Axelsson, K.; Hale, T.; Hepburn, C.; Wetzer, T. The Meaning of Net Zero and How to Get It Right. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, H.L.; den Elzen, M.G.; van Vuuren, D.P. Net-Zero Emission Targets for Major Emitting Countries Consistent with the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; Connors, S.; et al. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Schillebeeckx, S.J. Digital Transformation, Sustainability, and Purpose in the Multinational Enterprise. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, O.; Russell, J.; Cherrington, R.; Fisher, O.; Charnley, F. Digital Transformation and the Circular Economy: Creating a Competitive Advantage from the Transition towards Net Zero Manufacturing. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 189, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Luthra, S. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Net Zero Emissions: Innovation-Driven Strategies for Transitioning from Incremental to Radical Lean, Green and Digital Technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmy, A.J.; Ismail, H.; Aljneibi, N. A Novel Approach to Sustainable Behavior Enhancement through AI-Driven Carbon Footprint Assessment and Real-Time Analytics. Discover Sustain. 2024, 5, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husaini, D.H.; Lean, H.H. Digitalization and Energy Sustainability in ASEAN. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, S.; Giuffrida, M.; Mariani, M.M.; Bresciani, S. Resources and Digital Export: An RBV Perspective on the Role of Digital Technologies and Capabilities in Cross-Border E-Commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinings, B.; Gegenhuber, T.; Greenwood, R. Digital Innovation and Transformation: An Institutional Perspective. Inf. Organ. 2018, 28, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.J.; Carton, W.; Lund, J.F.; Markusson, N. Why Residual Emissions Matter Right Now. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, J.; Luderer, G.; Pietzcker, R.C.; Kriegler, E.; Schaeffer, M.; Krey, V.; Riahi, K. Energy System Transformations for Limiting End-of-Century Warming to below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavin, C.; Power, D.J. Challenges for Digital Transformation–Towards a Conceptual Decision Support Guide for Managers. J. Decis. Syst. 2018, 27, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagire, A.A.; Joshi, R.; Rathore, A.P.S.; Jain, R. Development of Maturity Model for Assessing the Implementation of Industry 4.0: Learning from Theory and Practice. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardolino, M.; Rapaccini, M.; Saccani, N.; Gaiardelli, P.; Crespi, G.; Ruggeri, C. The Role of Digital Technologies for the Service Transformation of Industrial Companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2116–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanias, S. Mastering Digital Transformation: The Path of a Financial Services Provider Towards a Digital Transformation Strategy. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems, Guimarães, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017; pp. 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Legner, C.; Eymann, T.; Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Böhmann, T.; Drews, P.; Ahlemann, F. Digitalization: Opportunity and Challenge for the Business and Information Systems Engineering Community. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Park, K.B.; Roh, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Mohammed, M.; Ghasemi, Y.; Jeong, H. An Integrated Mixed Reality System for Safety-Aware Human-Robot Collaboration Using Deep Learning and Digital Twin Generation. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. Digital Applications in Implementation of Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Accessibility to Digital World (ICADW), Guwahati, India, 16–18 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L. Remote Human–Robot Collaboration: A Cyber–Physical System Application for Hazard Manufacturing Environment. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 54, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J. A Survey of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping with an Envision in 6G Wireless Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1909.05214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, N.; Alamin, K.; Fraccaroli, E.; Poncino, M.; Quaglia, D.; Vinco, S. Digital Transformation of a Production Line: Network Design, Online Data Collection and Energy Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2021, 10, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Qian, S.; Li, T. Modeling Product Carbon Footprint for Manufacturing Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Lu, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, L.; Hong, J.; Broyd, T. Digital Tools for Revealing and Reducing Carbon Footprint in Infrastructure, Building, and City Scopes. Buildings 2022, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, O.; Al-Makhadmeh, Z.; Tolba, A.M.R. EMS: An Energy Management Scheme for Green IoT Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 44983–44998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Li, W.; Chang, X.; Zomaya, A.Y. Online Energy Management under Uncertainty for Net-Zero Energy Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation, Virtual, 18–21 May 2021; pp. 271–272. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.; Govindan, K. Net-Zero Economy Research in the Field of Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 1352–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilela, L.; Nel, D. The Role of Data and Information Security Governance in Protecting Public Sector Data and Information Assets in National Government in South Africa. Africa’s Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 2021, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Morais, H.; Sousa, T.; Lind, M. Electric Vehicle Fleet Management in Smart Grids: A Review of Services, Optimization and Control Aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1207–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, H.O.; Kannegiesser, M.; Autenrieb, N. The Role of Electric Vehicles for Supply Chain Sustainability in the Automotive Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, M.; Schöggl, J.P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Application of Digital Technologies for Sustainable Product Management in a Circular Economy: A Review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Chaikittisilp, S.; Tan, K.H. The Effect of Lean Methods and Tools on the Environmental Performance of Manufacturing Organisations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 200, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viles, E.; Santos, J.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Grau, P.; Fernández-Arévalo, T. Lean–Green Improvement Opportunities for Sustainable Manufacturing Using Water Telemetry in Agri-Food Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.Y.; Lai, P.Y. Promoting the Application of Lean Automation—Take the Automobile Oil Seal Manufacturing Industry as an Example. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th Eurasia Conference on IoT, Communication and Engineering (ECICE), Yunlin, Taiwan, 28–30 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.Y.; Lai, P.Y. Promoting the Application of Refined Lean Automation—Take the Automobile Oil Seal Manufacturing Industry as an Example. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th Eurasia Conference on IoT, Communication and Engineering (ECICE), Yunlin, Taiwan, 27–29 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 948–951. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T. Extensions of the TOPSIS for Group Decision-Making under Fuzzy Environment. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 114, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.P. Quality Function Deployment. Qual. Prog. (ASQC) 1986, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Akao, Y. An Introduction to Quality Function Deployment. In Quality Function Deployment (QFD): Integrating Customer Requirements into Product Design; Productivity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Methods for Multiple Attribute Decision Making. In Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 58–191. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.