Abstract

In recent years, sandwich composite panels have gained significant attention due to their high strength-to-weight ratio, excellent energy absorption capability, and structural efficiency under impact and crash conditions. These panels, which consist of lightweight cores enclosed between stiff face sheets, are widely used in aerospace, automotive, and marine applications. Previous research on energy absorption mechanisms, failure modes, and the influence of core materials on crash performance has highlighted the advantages of various core configurations in improving Specific Energy Absorption (SEA). Among these, 3D-printed cores stand out for their design flexibility, efficient manufacturing process, and ability to customise mechanical properties through geometric optimisation. The present study investigates the crash behaviour of sandwich composite panels with 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA) cores by examining different core geometries and configurations through an experimental campaign.

1. Introduction

Crashworthiness refers to the ability of a structure to absorb and dissipate energy during an impact, thereby reducing the risk of damage to passengers and cargo. This attribute is critical in both the aerospace [1,2] and automotive industries [3], where safety, structural performance, and weight efficiency are non-negotiable requirements. Modern design strategies in these sectors aim not only to ensure structural integrity under operational conditions but also to mitigate the consequences of severe impact events [4]. To achieve this, engineers increasingly rely on advanced materials, innovative structural concepts, and sophisticated simulation tools [5].

Among the various structural solutions, sandwich structures have gained prominence due to their exceptional stiffness-to-weight ratio and energy absorption capabilities [6]. Typically composed of two thin, rigid face sheets bonded to a lightweight, thick core, these structures deliver an optimal balance between mechanical performance and weight reduction [7]. Their effectiveness in crash scenarios, however, depends on several factors, including the material selection, the geometry of the face sheets, and, most critically, the topology of the core [8].

The rapid development of additive manufacturing (AM) technologies has significantly expanded design possibilities for these structures [9]. Unlike conventional manufacturing methods, AM allows the fabrication of complex geometries that were previously unattainable, enabling the optimisation of core architecture for enhanced crashworthiness [10]. Among these techniques, Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) stands out as one of the most widely used due to its affordability, operational simplicity, and high processing efficiency [11]. Common materials for FFF include polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), nylon, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [8]. Leveraging these materials, researchers have been able to design sandwich structures with 3D-printed cores, offering new opportunities for lightweight, crash-resistant designs [12,13].

Recent studies highlight that hexagonal core configurations produced via 3D printing can significantly improve energy absorption while providing controlled and predictable failure modes [12]. Furthermore, complex structures like auxetic structures, characterised by a negative Poisson’s ratio, have attracted growing interest due to their unique mechanical behaviour, including superior indentation resistance, enhanced shear performance, and increased energy absorption [8,14].

In this study, PLA was selected as the core material, primarily for its processability in additive manufacturing and its favourable sustainability profile. Compared to traditional core materials such as Nomex and aluminium, PLA offers a markedly lower carbon footprint, positioning it as an environmentally responsible alternative for applications that demand both high performance and reduced environmental impact.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents a comprehensive description of the materials, manufacturing processes, and experimental methodologies employed in this study.

2.1. Constituent Materials

This study employed two primary material systems for the fabrication of the sandwich structures: a high-performance polymeric composite for the face sheets and a thermoplastic material for the core. The selection of these materials was based on their mechanical performance, processability, sustainability, and relevance to lightweight structural applications.

2.1.1. Face Sheet: Material and Manufacturing

The face sheets of the sandwich structures were manufactured using a unidirectional (UD) carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) prepreg supplied by Delta Preg S.p.A (Sant’Egidio alla Vibrata TE, Italy). The prepreg consisted of Toray (Tokyo, Japan) T700S UD high-strength carbon fibres impregnated with DT120 (Delta Preg S.p.A, Sant’Egidio alla Vibrata TE, Italy), a high-toughness epoxy resin system, with a resin content of approximately 40% by weight and an areal weight of 300 g/m2.

The plates were fabricated through hand layup of prepreg layers, followed by autoclave curing to ensure proper consolidation and void minimisation. A symmetric quasi-isotropic stacking sequence of [0/90]2s was adopted to provide balanced in-plane mechanical properties. The curing cycle was conducted in an autoclave according to the supplier’s recommendation: 90 min at a temperature of 135 °C and a pressure of 6 bar, with both the heating and cooling rates set to 2 °C/min.

The obtained mechanical properties of the laminates were calculated in the authors’ previous works [15] and summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Elastic properties of the T700-DT120 (UD).

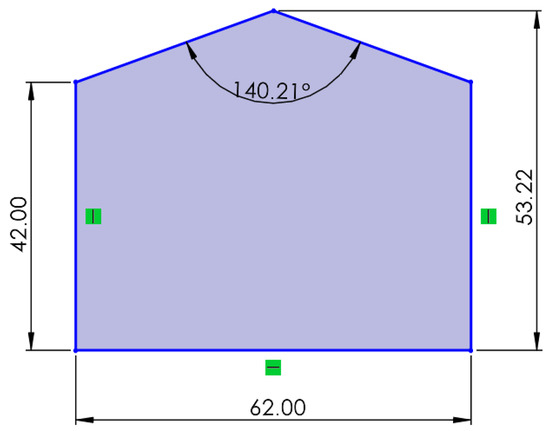

Following curing, the composite plates were cut to the required dimensions, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Face sheet geometry.

2.1.2. Core: Material and Manufacturing

The core elements of the sandwich structures were fabricated using polylactic acid (PLA) produced by Sunlu (Zhuhai, China), a biodegradable thermoplastic derived from renewable resources, in particular from fermented plant starch such as corn, sugarcane, and cassava. PLA was selected for its processing simplicity, relatively low cost, and favourable stiffness-to-weight ratio, making it a suitable candidate for low-to-moderate load-bearing structural components. The material was processed in filament form with a nominal diameter of 1.75 mm.

The cores were produced using additive manufacturing techniques, specifically fused filament fabrication, commonly referred to as fused deposition modelling (FDM). The printing velocity was set to 60 mm/s, while the layer height was maintained at 0.2 mm to balance surface finish quality and build time. The hot-end extruder temperature was set to 200 °C, according to the PLA datasheet. The print bed was maintained at a temperature of 55 °C to minimise warping and improve layer bonding during the printing process.

These parameters were selected based on previous expertise and the manufacturer’s recommendations to achieve consistent mechanical properties and geometric stability in the printed core components. The mechanical properties of the base material are supplied by the material’s manufacturer and collected in Table 2 [16].

Table 2.

Elastic properties of the PLA.

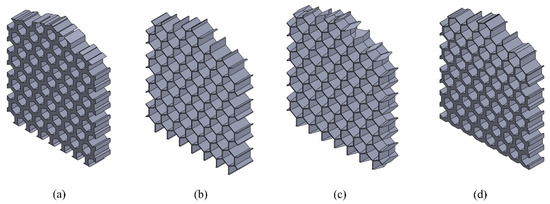

As shown in Figure 2, four core geometries were produced. The first two configurations, Figure 2a (coupons with this core will be referred to as C1) and Figure 2b (C2), consist of hexagonal honeycomb structures with an edge length of 3.36 mm and wall thicknesses of 2.16 mm and 0.41 mm, respectively. The remaining two cores maintain the same hexagonal pattern but introduce gradient variations. The core in Figure 2c (C3) incorporates a through-thickness gradient with an inclination angle of a positive 10° until the mid-plane, then negative after the mid-plane. The core in Figure 2d (C4) features a through-height gradient, where the wall thickness decreases progressively from a value of 2.16 mm at the base to 0.41 mm at the top. All the cores were printed with a thickness of 10 mm.

Figure 2.

The four different hexagonal honeycomb geometries manufactured through fused deposition modelling: (a) wall thickness of 2.16 mm, (b) wall thickness of 0.41 mm, (c) through-thickness gradient, and (d) through-height gradient.

2.1.3. Coupon Manufacturing

The face sheets were adhesively bonded to the cores using the bi-component epoxy resin SX10 EVO (Mates Italiana, Segrate, Milan, Italy), followed by a curing cycle in an oven at 50 °C for 12 h. The curing procedure was determined in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications for the resin, while ensuring the process temperature remained below the glass transition temperature of PLA (63 °C), thereby preventing thermal degradation or dimensional instability.

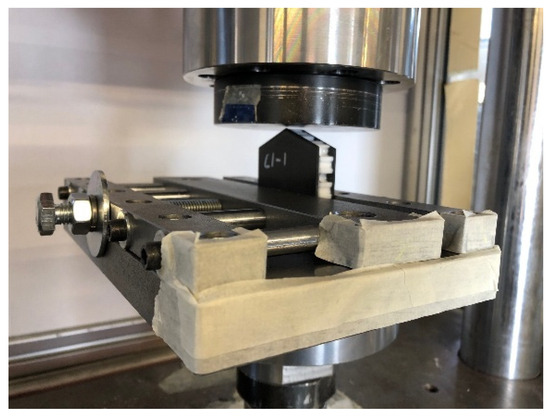

2.2. Crash Test

To evaluate the crashworthiness characteristics of the components, specific crushing tests were conducted on a Universal Testing Machine (Italsigma, Forlì, Italy) equipped with a 100 kN loading cell. At least five specimens for each core geometry were tested using a dedicated anti-slippage fixture (Figure 3) at a controlled crosshead displacement rate of 2 mm/min. To record the coupons crushing and evaluate their failure modes, a Basler ace acA3088-57gm (GigE, mono) camera (Advanced Technologies, Trezzano ul Naviglio, Milano, Italy) was used.

Figure 3.

Anti-slippage fixture.

During each test, load–displacement curves were recorded, and Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) parameters were computed to compare performance. In this study, the is defined as:

where and denote the specimen mass and height, respectively, while and denote the initial and final displacement points considered in the integration.

Assuming = 0 and equal to the total crushing length, this formulation provides the Total (). However, this value is significantly affected by the initial load peak, which is strongly dependent on the trigger geometry and its performance in experimental analyses. To address this, the present work focuses on the Steady-State (), where is selected to exclude the transition region prior to the onset of the steady crushing phase.

3. Results and Discussion

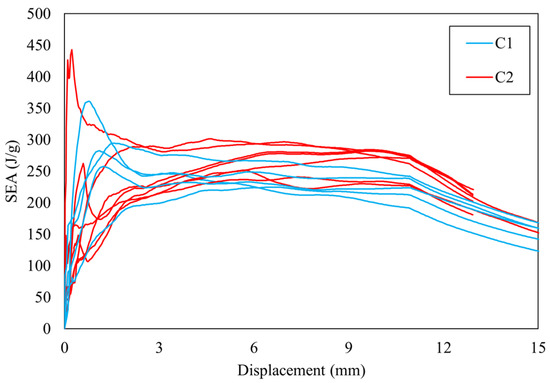

Figure 4.

C1 and C2 cores: SEA against displacement curves.

Table 3.

Specific energy absorption of C1 and C2 coupons.

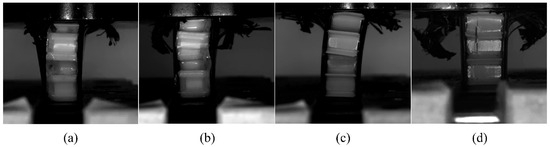

As both the CoV values and the SEA curves indicate, the variability of the results among the different coupons with the same core is not negligible. This discrepancy is linked to the lack of a stable and consistent failure mode (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a) Core–face sheet debonding in C1; (b) interface failure with buckling in C1; (c) bending failure in C2; (d) interlayer cracking within the core of C2.

As shown in Figure 5, C1 coupons exhibit interface weakness, leading to core–face sheet debonding and subsequent buckling, whereas in C2 coupons, the core itself is the weakest region, resulting in bending failure or interlayer cracking.

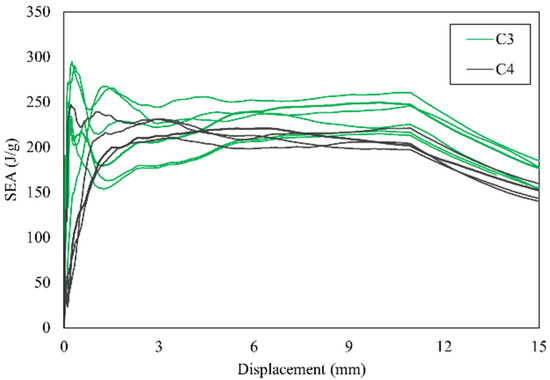

C3 and C4 coupons show a more stable and repeatable SEA trend, which results in a lower CoV (Figure 6 and Table 4).

Figure 6.

C3 and C4 cores: SEA against displacement curves.

Table 4.

Specific energy absorption of C3 and C4 coupons.

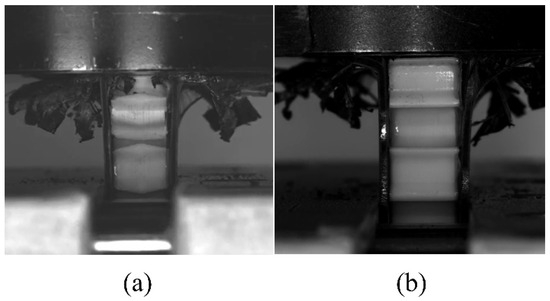

These outcomes reflect a more stable and controlled failure of the coupons for both C3 and C4 geometries. As observed in Figure 7, the failure progresses gradually throughout the test, leading to reduced result variability (i.e., a lower coefficient of variation).

Figure 7.

Controlled and progressive failures for both C3 (a) and C4 (b) coupons.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the crashworthiness and energy absorption characteristics of CFRP–PLA sandwich structures featuring additively manufactured honeycomb cores. These cores were designed with different geometries, specifically uniform and gradient wall thickness configurations. The results demonstrated that the core geometry significantly influences the mechanical response and energy absorption performance under quasi-static crushing conditions.

Among the tested designs, the gradient configurations (C3 and C4) demonstrated the most stable and repeatable crushing behaviour. This was evidenced by their significantly lower coefficients of variation (3.35% and 2.60%, respectively) compared to the uniform cores (7.33% and 9.33%). Although C2 achieved the highest average SEA (267.14 J/g), its high variability and premature failure modes, such as core cracking and interface debonding, limit its reliability. Conversely, the gradient cores provided more controlled progressive failure, ensuring improved structural integrity and predictability during energy absorption.

These findings highlight the effectiveness of integrating graded honeycomb architectures with thermoplastic cores in hybrid composite sandwich structures for enhancing crashworthiness while maintaining lightweight characteristics. Future work will focus on optimising gradient parameters, exploring dynamic loading conditions, assessing the long-term durability of such configurations, and implementing and validating numerical models to study different geometries, thereby broadening their applicability in automotive and aerospace crashworthy components.

Author Contributions

M.P.F.: Methodology, visualisation, writing—review and editing; F.S.: Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; G.P.: writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, methodology, formal analysis, investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by MOST—Sustainable Mobility National Research Centre, the European Union NextGenerationEU (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR)—Missione 4 Componente 2, Investimento 1.4—D.D. 1033 17/06/2022, CN00000023, CUP: J33C22001120001) and SMALSAT “Solar Panel Design for the SMAL-SAT nanosatellite” project ( PR FESR EMILIA ROMAGNA 2021-2027 CUP: J47G22000720003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABS | Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| CFRP | Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer |

| CoV | Coefficient Of Variation |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modelling |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| SEA | Specific Energy Absorption |

| UD | Unidirectional |

References

- Falaschetti, M.P.; Semprucci, F.; Birnie Hernández, J.; Troiani, E. Experimental and Numerical Assessment of Crashworthiness Properties of Composite Materials: A Review. Aerospace 2025, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresto, V. Crashworthiness design and evaluation of civil aircraft. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 148, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Bai, J.; Zuo, W. Simplified crashworthiness method of automotive frame for conceptual design. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, H.; Xie, J.; Si, X. Review on the crashworthiness design and evaluation of fuselage structure for occupant survivability. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaschetti, M.P.; Semprucci, F.; Raimondi, L.; Serradimigni, D. Experimental and Numerical Assessment of Sheet Molding Compound Composite Crushing Behavior. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 15281–15292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlochan, F. Sandwich Structures for Energy Absorption Applications: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Yao, L.; Lyu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, H. Mechanical Properties and Damage Failure of 3D-Printed Continuous Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composite Honeycomb Sandwich Structures with Fiber-Interleaved Core. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 1980–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, L. Bending Behavior of Sandwich Composite Structures with Tunable 3D-Printed Core Materials. Compos. Struct. 2017, 175, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Çava, K.; Uşun, A.; Güler, O. Impact of Cell Design Parameters on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Cores for Carbon Epoxy Sandwich Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tao, C.; Liang, X. Crashworthiness and optimization design of additive manufacturing double gradient lattice enhanced thin-walled tubes under dynamic impact loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenken, B.; Barocio, E.; Favaloro, A.; Kunc, V.; Pipes, R.B. Fused Filament Fabrication of Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: A Review. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qi, W.; Luo, K.; Yin, C.; Li, J.; Lu, C.; Lu, L. Bending Performance and Failure Mechanisms of Composite Sandwich Structures with 3D Printed Hybrid Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Cores. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2024, 26, 990–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainin, F.N.; Azaman, M.D.; Majid, M.S.A.; Ridzuan, M.J.M. Effect of Varying Core Density and Material on the Quasi-Static Behaviors of Sandwich Structure with 3D-Printed Hexagonal Honeycomb Core. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 9948–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Li, T.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L. Mechanical Properties of Sandwich Composites with 3d-Printed Auxetic and Non-Auxetic Lattice Cores under Low Velocity Impact. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaschetti, M.P.; Rondina, F.; Zavatta, N.; Troiani, E.; Donati, L. Effective Implementation of Numerical Models for the Crashworthiness of Composite Laminates. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 160, 108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLA+ Product Features: High Toughness PLA Multiple Colors Main Applications. Available online: https://store.sunlu.com/it-it/products/moq-6kg-pla-2-0-upgraded-pla-pla-plus-3d-printer-filament-1kg?srsltid=AfmBOooEsFsxrb6INgQLaeNEzNZS2rml-M5Qrsj_1GFereGOyc-AHOXj (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.