Abstract

Accurate and continuous tracking of athletes is essential to meet the infotainment demands and health and safety requirements of major marathon events. However, the current ability to track individual athletes or groups at mass sporting events is severely limited by the weight, size and cost of the equipment required. In marathons, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology is typically used for timing but can only provide accurate tracking at widely spaced intervals, relying on heuristic and interpolation algorithms to estimate runners’ positions between measurement points. Alternative IOT solutions, such as Low Power Wide Area Network (LWPAN), have limitations in terms of range and require dedicated infrastructure and regulation. Therefore, we analyzed the potential use of smartwatches as accurate and continuous tracking devices for athletes, assessing battery consumption during tracking and standby drain, achievable GPS tracking accuracy and the update rate of data transfer from the device in urban environments. The 4G LTE battery drain is different from non-urban areas. Analysis of standby usage is necessary as devices need to conserve power for tracking. We programmed an application that allowed us to control the modalities of acquisition and transmission intervals, integrating advanced logging and statistics at runtime, and evaluated the achievable results in major marathon events. Our empirical evaluation at the Frankfurt, Athens and Vienna marathons with three different types of smartwatch tracking platforms showed the validity of this approach, while respecting some necessary limitations of the tracking settings. Median battery drain was 5.3%/h in standby before race start (σ 1.5) and 16.5%/h in tracking mode (σ 3.29), with an actual update rate varying between 19 and 57 s on Wear OS devices. The average GPS offset to the track was 4.5 m (σ 8.7). Future work will focus on integrating these consumer devices with existing time and tracking infrastructure.

1. Introduction

The accurate and continuous tracking of athletes is a critical requirement for ensuring the health, safety, and overall experience of participants in major marathon events. Beyond safety, real-time tracking also meets the growing infotainment demands of spectators, who increasingly expect live updates and interactive features to enhance their engagement with the event. However, existing tracking solutions face significant limitations. Traditional RFID-based timing systems, while widely used, provide only intermittent updates at checkpoints, relying on heuristic and interpolation algorithms to estimate runner positions between measurement points. This lack of resolution in continuous tracking hinders both operational efficiency and the spectator experience.

Alternative IoT-based solutions, such as Low-Power Wide-Area Networks (LPWAN), have been explored for athlete tracking [1]. However, these systems are constrained by range limitations, the need for dedicated infrastructure, and regulatory challenges, making them less practical for large-scale urban marathon events. In contrast, smartwatches offer a promising solution due to their lightweight design, widespread availability, and integrated GPS and connectivity features. These consumer devices have the potential to provide accurate, real-time tracking without the need for extensive additional infrastructure.

This study investigates the feasibility of using smartwatches as continuous tracking devices for marathon runners. By analyzing key performance metrics such as battery consumption during tracking and standby modes, GPS accuracy, and data transfer update rates in urban environments, we aim to evaluate the practicality of this approach. The focus is on three questions. What achievable duration can be expected given the impact of battery drain? What level of continuous tracking quality can be achieved despite connection and uplink issues? And finally, what level of tracking accuracy is provided? Our empirical evaluation, conducted at the Frankfurt, Athens, and Vienna marathons using three different smartwatch platforms, demonstrates the potential of this solution while highlighting necessary trade-offs in tracking settings. This work lays the foundation for integrating consumer-grade smartwatches with existing timing and tracking infrastructures, offering a scalable and efficient alternative for mass sporting events.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents some related work. Our evaluated solution and the hardware used are explained in Section 3. Section 4 describes the experiments and the results obtained. Finally, Section 5 presents the discussion, the conclusions, and future work.

2. Related Work

The accurate and continuous tracking of athletes during marathon events has long been a challenge due to the limitations of existing technologies. Traditional solutions, such as RFID-based timing systems, are widely used but provide only intermittent updates. Passive RFID trackers [2] are small, lightweight, and integrated into race bibs. These trackers rely on electromagnetic energy transmitted by RFID readers placed at the start and finish lines, as well as at a few scattered checkpoints along the course. While effective for timing purposes, this approach lacks the resolution needed for continuous tracking, as it depends on heuristic and interpolation algorithms to estimate runner positions between measurement points.

Recent studies have used Long-Range (LoRa) Wide-Area Network GPS tracker technology to monitor the positions of runners in cross-country races and marathons [1,3]. In these studies, the evaluation setup uses stationary or mobile LoRa gateways. However, this technology is limited by the circumstances of a mass event in a city, due to issues of scalability and radio coverage. For instance, deterministic monitoring and real-time operation cannot be guaranteed, and maximum duty cycle regulations impose additional constraints [4].

The need for continuous tracking is further emphasized by the health and safety requirements of marathon events [5]. Marathon runners often push themselves to their physical limits, which can lead to dehydration, heat exhaustion, or cardiac events. Real-time location monitoring with wearable technology [6] allows race organizers to quickly identify and assist runners in distress, potentially preventing serious injuries or fatalities.

From an infotainment perspective, continuous tracking also enhances the spectator experience. Real-time updates and interactive features allow fans to follow their favorite runners throughout the race, boosting engagement [7]. This demand for live tracking has grown in recent years, as spectators increasingly expect immersive experiences during large-scale sporting events.

In long-distance events such as cross-country or marathon championships, achieving continuous tracking of runners’ pace profiles and tactical behaviors requires high-resolution observation. This level of detail allows athletes to evaluate their decisions and refine their strategies, ultimately leading to better performance [8]. Experimental solutions, such as drone systems equipped with depth cameras, have been explored [9], but they are impractical for large-scale events and recreational runners.

Pandey et al. [10] highlighted the challenges faced by recreational athletes, who are often unable to monitor sport-specific techniques due to the limitations of existing tracking technologies. They expressed a need for improved tracking solutions. Similarly, Venek et al. [11] noted in their review that, although sensor technologies have been used to assess movement quality, their application in recreational and professional sports outside of controlled laboratory settings remains in its early stages.

While traditional RFID systems have been the standard for marathon tracking, the emergence of consumer-grade wearable devices, such as smartwatches, offers a promising alternative [12]. Smartwatches are lightweight, widely available, and equipped with integrated GPS and connectivity features, making them suitable for real-time tracking without the need for extensive additional infrastructure. Studies of the accuracy of GPS sports watches in measuring distance covered show a median error of less than 2% [13,14].

3. Materials and Methods

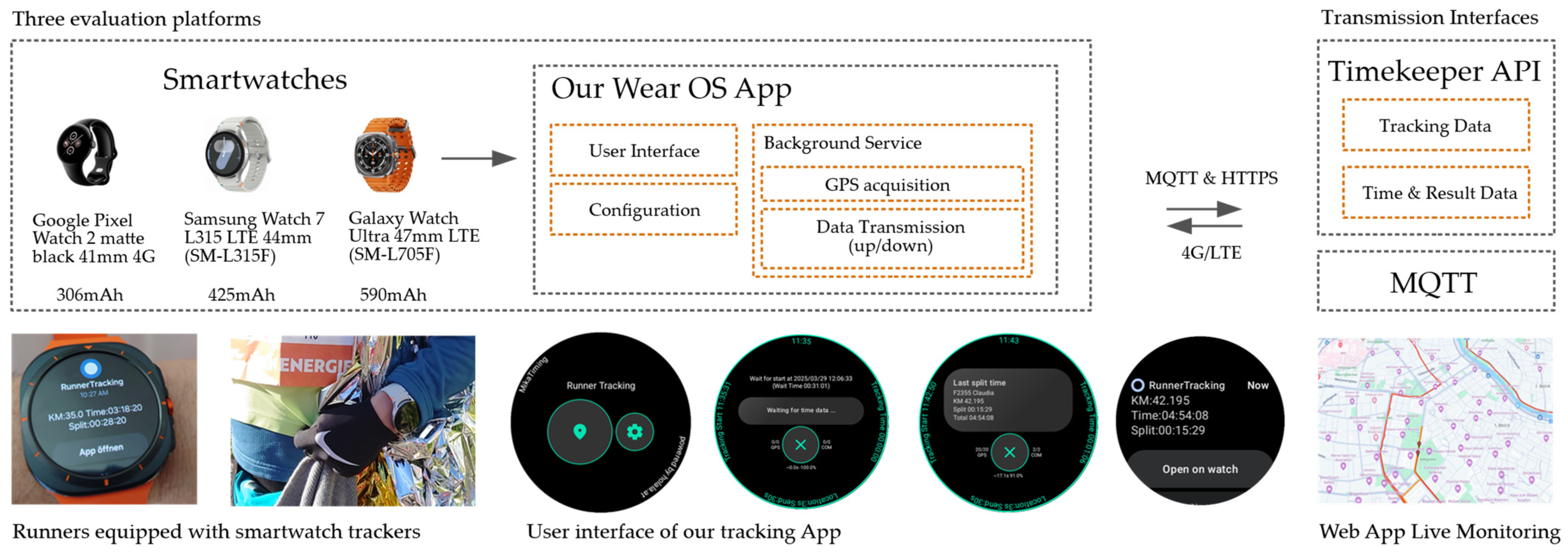

The proposed method for runner tracking at marathon events uses smartwatch platforms and a programmed tracking application, which offers a set of configuration options, to assess different modalities for continuous runner monitoring. The smartwatch trackers were worn by the runners and transmitted their positions continuously. This information was stored in a database and visualized in near real-time on web interfaces. Our architecture is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture and selected hardware components for our mobile smartwatch-based system for tracking runners in city races and marathons. Symbolized data acquisition and communication overview.

3.1. Hardware

We installed our tracking application on three different smartwatch hardware platforms. All three devices were equipped with a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receiver and supported either 4G LTE or 3G UMTS. The Google Pixel Watch 2 has a 306 mAh battery and is powered by a Qualcomm Snapdragon W5 Gen 1 chipset [15] that only provides a single-frequency L1 GPS signal. The Samsung Galaxy Watch 7 L315 LTE (SM-L315F) and the Galaxy Watch Ultra LTE (SM-L705F) both have a Samsung Exynos W1000 processor [16] and dual-frequency GPS that supports L1 and L5 signals. The Watch 7 L315 LTE has a 425 mAh battery, while the Galaxy Watch Ultra LTE has a 590 mAh battery.

Wear OS, an Android [17] distribution designed for smartwatches, was the operating system deployed on all platforms. During our data collection, version 5 of Wear OS was active. In order to provide mobile internet connectivity, we setup all of the devices with an eSIM for 3G or 4G uplink access. We monitored the current active connection.

3.2. Tracking Application

To evaluate different tracking settings, we developed a Wear OS application that included a user interface (UI) for runtime interaction, a configuration module for pre-settings and runners’ data, and a background service that handled GPS acquisition, battery monitoring, and network communication with the transmission interfaces (see Figure 1).

We added a configuration component for our various study settings. This component stores participants’ event-related information, tracking settings, and other options. The configuration is stored in an XML file and can be transferred remotely via the included WebDAV feature. Each app installed on a smartwatch generates a unique ID that must be associated with a Participation ID and an Event ID in the time-keeping interface. Tracking settings include the GPS position update rate, minimum movement filter, start time trigger, remote start by SMS, send rate, and send queue enablement. The send queue handles send errors and provides collections of GPS positions in case of slower send rates. Various app settings can also be controlled, such as wake locks, which keep the CPU running constantly, and the ability to enable the high-accuracy GPS setting from the Android API. Both were enabled by default.

The core component of our tracking application is an Android background service. It requires various execution permissions on the smartwatch, including foreground service rights. These permissions enable continuous access to location data. The service can be started directly from the app’s user interface (UI) or scheduled to start tracking at a specific time from the configuration file. While running, the service collects GPS positioning data and uploads it to the transmission interfaces according to the selected configuration. The service also downloads time split information for the app’s integrated UI time notification service for runners. The uploaded data includes the following: position (longitude, latitude, and altitude), estimated accuracy, timestamp, current mobile carrier, connection type, battery level, and information about the associated runner. The connection interface is HTTPS or MQTT, and the message format used is JSON.

On the receiving end, the collected data is stored in a relational database. The timekeeping company provides real-time information via a web API interface. This data is used by web-based live visualization to show runners’ progress on different types of maps and in list components.

The background tracking service monitors battery consumption as a percentage and records the current value every minute. An integrated descriptive statistics component collects data about the data transmission process, GPS collection, and battery usage. This statistical data is stored in a JSON file and uploaded via the integrated WebDAV component for post-event analysis. This data is used in the results section. For debugging, detailed logging is available, and, if necessary, remote SMS-based control is integrated into the service component.

The UI component displays continuous tracking statistics and includes a subcomponent for adjusting settings on-site, if necessary. It provides time-split notifications from the timing service for the runner and uses vibrotactile and audio notifications for this purpose. The app was developed using Kotlin and is compatible with the Android SDK and Wear OS [18]. The target build platform requirement is Wear OS 4.0 or higher.

3.3. Marathon Tracking Study Setup

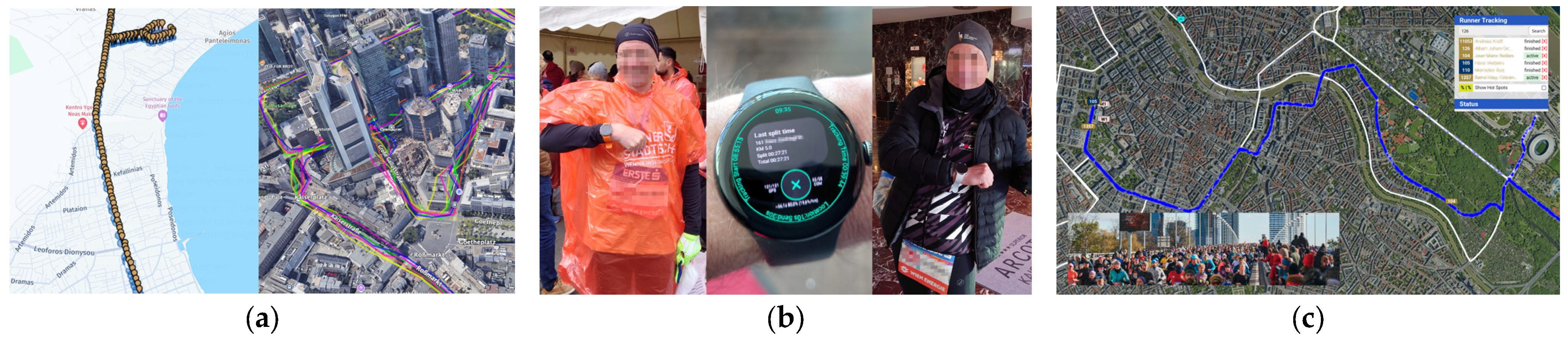

We employed this runner-tracking approach at three big city marathon events: Frankfurt (2024), Athens (2024), and Vienna (2025), in that chronological order. At each event, we provided runners with our smartwatch trackers. The Frankfurt marathon was our first setup and part of our preliminary studies to determine the proper settings. Five watches were used, and the update rate was 10 s without message queuing. In Athens, we handed out sixteen watches for the 10 K and full marathon distances. We used the collected geo-position data of nine marathon runners wearing the watches for our post-event GPS accuracy analysis. In Vienna, we deployed seven watches to observe tracking quality. Two study participants did not appear, so we gave the watches to two people to move along the track and mimic runners. Figure 2a shows the recorded tracks of the runners in Frankfurt and Athens.

Figure 2.

Evaluation and data collection at marathon events: (a) On the left are the GPS points collected by a selected runner’s device (A1) in Athens; on the right are traces from the Frankfurt marathon event, which were used for preliminary studies. (b) Participating runners at the Vienna Marathon. The watch screen shows the details displayed during tracking, such as the collected transmissions or positions. (c) The live tracking web interface shows two runners who are still on track. The blue-highlighted section of the racetrack shows the current distribution of runners at the event, estimated from RFID data.

The volunteer runners were recreational and hobby athletes of varying ability levels. Each athlete wore the tracker on their wrist, as depicted in Figure 2b, which shows two athletes in Vienna. Figure 2c shows our live visualization with two runners still on track, represented by golden labels.

In our post-analysis of the GPS tracking data, we compared the GPS points recorded by our runners’ smartwatches with the nearest points on the track, disregarding time. We used the Python (3.14) module Shapely [19] for geospatial calculations and coordinate transformations. The track was available in KML format for the events.

The observed battery drain is measured as a percentage per hour and varies by model and battery capacity. The current battery percentage is the value provided by the Android Wear OS API. Using this percentage and the known capacity of different devices’ internal lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries, one can calculate ongoing power usage and drain in milliwatts (mW) or milliamps (mA), as well as possible runtime.

4. Results

This section describes the results obtained in terms of performance measures and data distribution. For all marathon tracking studies, we ensured that LTE connectivity was the only active connection and that Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and NFC were deactivated. The background tracking service was pre-configured to activate five minutes before the official start of each event.

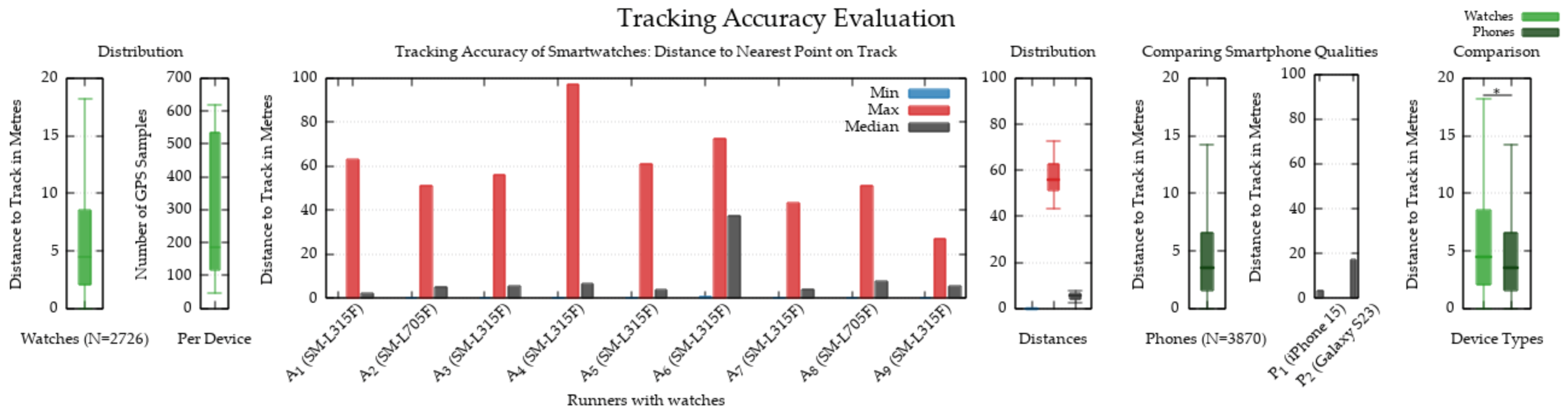

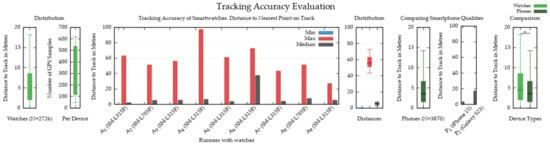

We used our nearest-point implementation to determine the offset in GPS accuracy during the Athens event. Figure 3 shows the results for nine marathon runners (A1…A9). The runners’ devices were configured with a start-time trigger and a GPS update rate of 12 s. The devices also had a minimum movement filter of three meters. For comparison purposes only, we applied a minimum move-distance filter of 0 m to devices A2 and A3. We handed out the devices to the runners the day before to analyze battery drains in standby mode. However, the drain was too severe for some devices, so not all of them were operational by the time the runners reached the finish line. We collected 2726 samples. To demonstrate the difference in accuracy, we compared our results with those of two athletes who used a smartphone for tracking.

Figure 3.

The tracking accuracy of smartwatches at the Athens Marathon is based on 2726 samples. The smartphone comparison revealed slight yet significant differences (* p < 0.05). Figure 2a illustrates A1’s runner’s trace.

Our results demonstrate the quality that can be achieved in dense urban areas, where the median GPS offset distribution across all devices is below 10 m (details in Figure 3). Overall, the median offset of the collected samples was 4.47 (σ 8.67) meters. Comparing these results with those from smartphones (3870 samples), which had an offset of 3.53 (σ 10.99) meters, revealed slightly worse but comparable quality (right Figure 3).

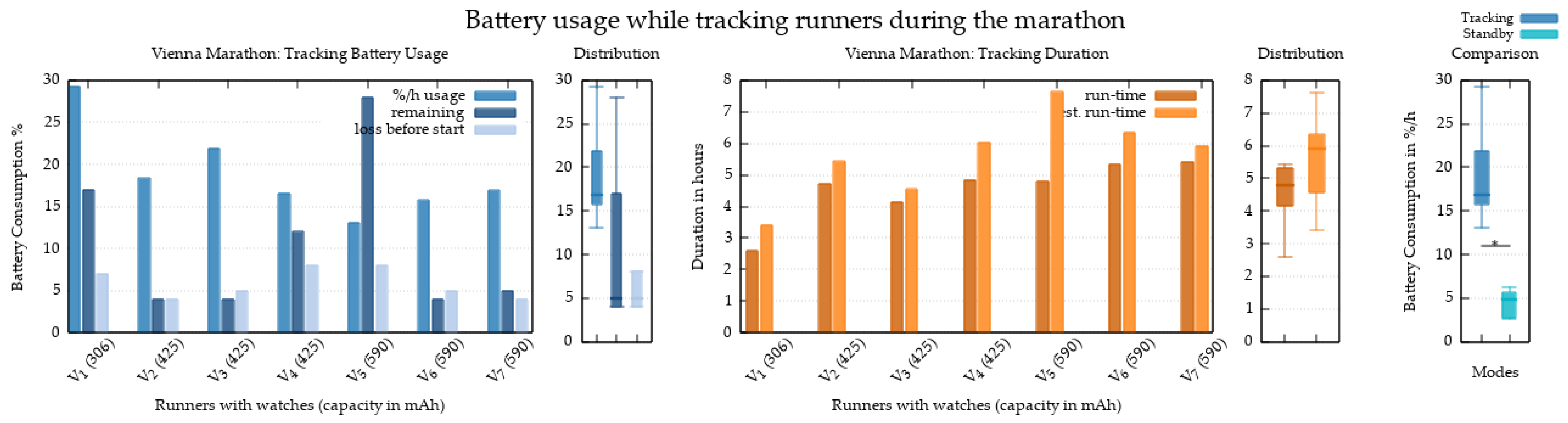

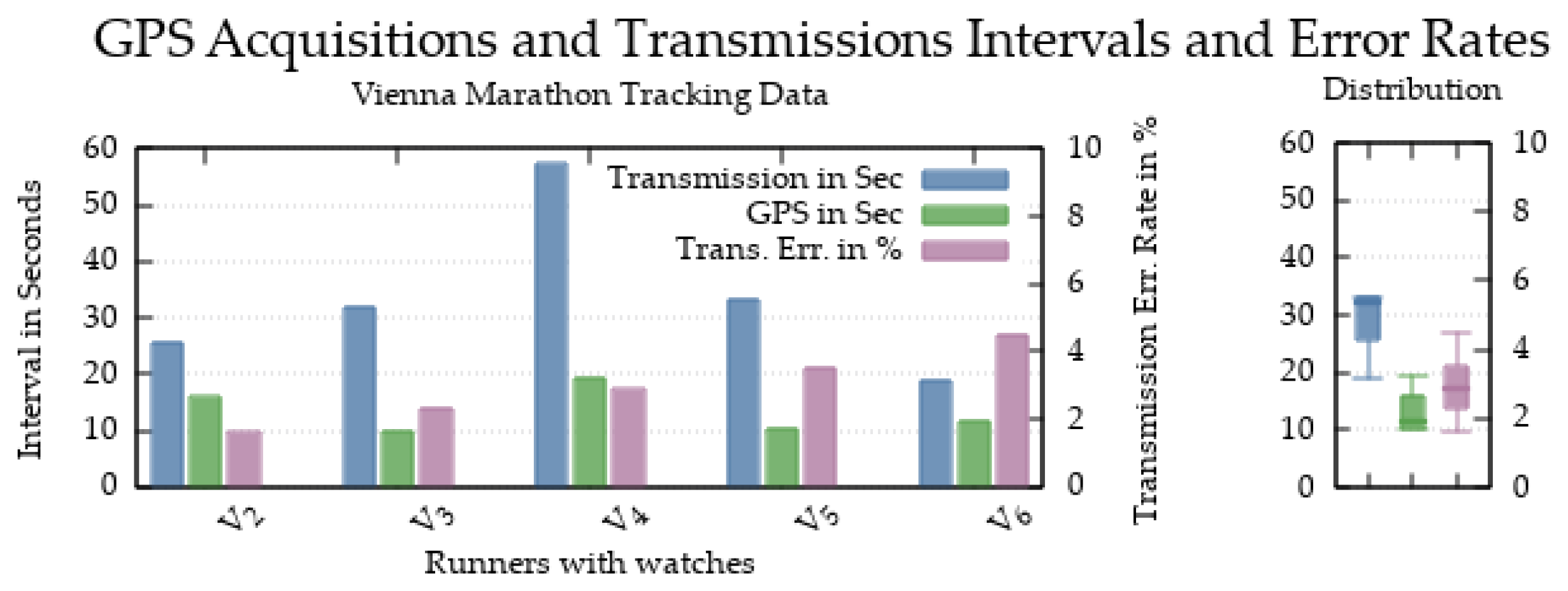

At the Vienna event, we used an improved version of the app that included time service notifications for the runner and a send queue. Seven watches were on track (VN). The watches V2, V6, and V7 used a send interval of 15 s; the remaining watches used a send interval of 30 s. All watches used a 10 s GPS acquisition interval and had the minimum movement filter set to three meters. Time service updates for the runner’s notification occurred every minute. The mimicking participants used V1 and V7 watches.

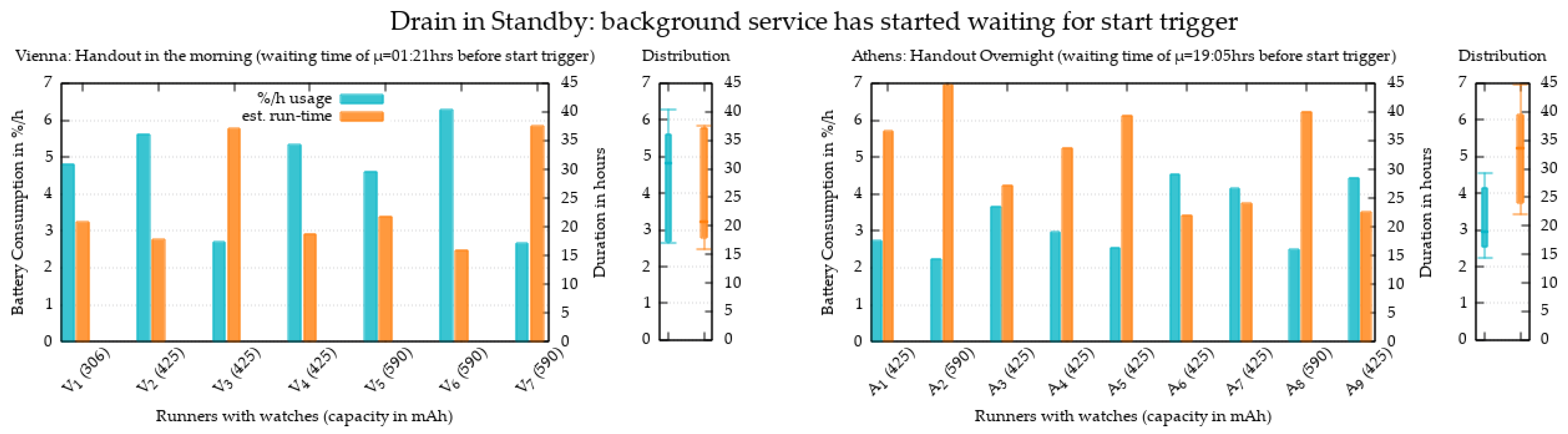

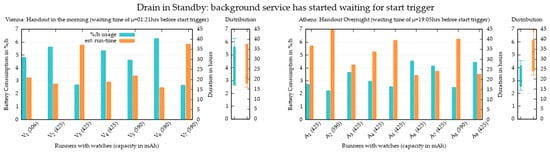

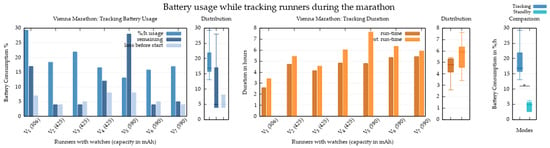

Figure 4 compares the standby power consumption of devices waiting for the start trigger in background services. The median power consumption across all devices was 4.8% (σ 1.4%) per hour in Vienna, where the standby period was shorter, and 3% (σ 0.9%) per hour overnight in Athens. Without V1 and V7, the median drain was 5.3% (σ 1.5%) per hour. The median standby runtime ranges from 22 to 33 h, depending on the setting. Figure 5 shows consumption during the race, including the estimated runtime. The median drain is 16.9% (σ 5.3%) per hour. Assuming an internal nominal voltage of 3.8 V and a battery capacity of 425 mAh for the SM-L315F device, consumption equates to 64 mW during the race and 20 mW in standby mode.

Figure 4.

The graph illustrates battery drain in standby mode and provides an estimated runtime based on data collected during the Athens and Vienna events. The study includes three different device platforms with varying battery capacities.

Figure 5.

Provide a detailed overview of all devices’ consumption at the Vienna event. The median drain is 16.9% per hour. There is a significant difference in battery drain between tracking mode and standby mode (* p < 0.05).

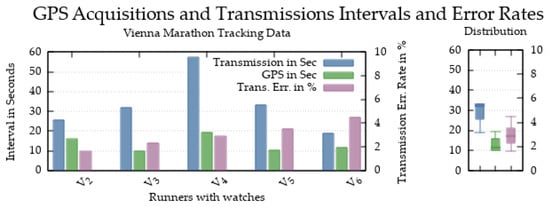

To answer our initial question about the quality of continuous tracking, we evaluated the GPS acquisition and data transmission intervals, as illustrated in Figure 6. Table 1 shows all the collected data. The transmission interval differs from the configured setting, resulting in a median error ratio of 2.9%. The detailed values are shown in Table 1, and the distribution is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Effective GPS acquisitions and data transmissions from the Vienna marathon tracking devices. The failed transmission rate indicates the percentage of unsuccessful attempts to transfer position information.

Table 1.

Detailed smartwatch tracking data and settings for five marathon runners in Vienna.

We analyzed the differences in tracking accuracy between smartwatches and smartphones, as shown in Figure 3, and compared battery usage in standby mode when the background service is waiting for the start trigger and the tracking mode, as shown in Figure 4. To determine whether there was a significant difference between the observations collected, we performed a two-tailed independent t-test with an alpha significance level of 0.05 on our marathon tracking data. We performed the statistical analysis using the implementations from the Python SciPy module. For the GPS accuracy comparison (Figure 3) of the nearest point to the racetrack between smartwatches and smartphones, we can reject the null hypothesis (there is a significant difference, with a p-value of 0.0004). As expected, we found a significant difference in battery consumption (Figure 5) between the standby and tracking modes (p-value of 0.0003).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Our evaluation shows that recent smartwatch platforms provide a feasible approach for continuous runner tracking with certain constraints. Regarding our three initial questions, we can draw the following conclusions: First, in terms of energy, we found that certain groups of runners require a minimum battery capacity for tracking. For elite runners, a capacity of around 300 mAh is sufficient. Hobby runners require a larger battery, at around 400–600 mAh. Recreational runners may need an even larger battery for runs up to six hours long. Considering standby consumption, participating hardware platforms may be insufficient for the latter group.

Data transmission and the activation of LTE connectivity are the main energy consumers. In a preliminary study, we compared energy consumption with and without LTE connectivity. With LTE disabled in standby mode, the Google Pixel Watch 2 consumed only 3.3 mW (0.9%/h). The different GPS acquisition rate settings and minimum movement distance filter had a less noticeable effect on battery drain.

As for our second question, we noticed some transmission errors, though there were no significant gaps in the data. Continuous tracking is possible, and unsuccessful attempts can be retransmitted via a send queue.

Regarding the final question of tracking accuracy in urban areas, there were significant differences among the smartphones we selected. However, for continuous runner monitoring with a median offset of less than five meters, this accuracy is sufficient for potential applications, such as live TV broadcasting.

In the future, smartwatch devices may allow system-level permissions that control mobile connectivity, such as LTE, within the app. This could improve standby mode durability. A next-generation device with 5G capabilities, extended discontinuous reception, and power-saving modes could further ease constraints. Future work must focus on integrating these consumer devices with existing time and tracking infrastructure.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the “mika:timing GmbH” and the “Enterprise Sport Promotion GmbH”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hochreiter, D. Athlete Tracking at a Marathon Event with LoRa: A Performance Evaluation with Mobile Gateways. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhade, R.H. RFID Based Marathon Tracking System. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, S.; Romero-Díaz, P.; García-Navas, J.L.; Lloret, J. Lora-Based System for Tracking Runners in Cross-Country Races. Proceedings 2019, 42, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado, F.; Vilajosana, X.; Tuset-Peiro, P.; Martinez, B.; Melià-Seguí, J.; Watteyne, T. Understanding the Limits of LoRaWAN. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 1600613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Moran, J.; Ahmed, H.; Bermon, S.; Bigard, X.; Doerr, D.; Lacoste, A.; Miller, S.; Weber, A.; Foster, J.; et al. Athlete Health and Safety at Large Sporting Events: The Development of Consensus-Driven Guidelines. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçkin, A.Ç.; Ateş, B.; Seçkin, M. Review on Wearable Technology in Sports: Concepts, Challenges and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chung, L.; Tan, K.H.; Peng, B. I Want to View It My Way! How Viewer Engagement Shapes the Value Co-Creation on Sports Live Streaming Platform. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, A.; Hanley, B.; Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Renfree, A. Pacing Profiles and Tactical Behaviors of Elite Runners. J. Sport. Health Sci. 2021, 10, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsson, M.; Willén, J.; Swarén, M. A Drone-Mounted Depth Camera-Based Motion Capture System for Sports Performance Analysis. In Artificial Intelligence in HCI.; Degen, H., Ntoa, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, M.; Nebeling, M.; Park, S.Y.; Oney, S. Exploring Tracking Needs and Practices of Recreational Athletes. In Proceedings of the 13th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare—Demos and Posters, Trento, Italy, 20–23 May 2019; EAI: Trento, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Venek, V.; Kranzinger, S.; Schwameder, H.; Stöggl, T. Human Movement Quality Assessment Using Sensor Technologies in Recreational and Professional Sports: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacko, T.; Bartsch, J.; von Diecken, C.; Ueberschär, O. Validity of Current Smartwatches for Triathlon Training: How Accurate Are Heart Rate, Distance, and Swimming Readings? Sensors 2024, 24, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, R.E.; Adolph, S.T.; Swart, J.; Lambert, M.I. Accuracy of GPS Sport Watches in Measuring Distance in an Ultramarathon Running Race. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2020, 15, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J. Accuracy of Garmin GPS Running Watches over Repetitive Trials on the Same Route. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.00491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossil Gen 5 LTE Wearable with a Snapdragon Wear 3100 Processor|Qualcomm. Available online: https://www.qualcomm.com/products/mobile/snapdragon/wearables/wearables-device-finder/pixel-watch-2 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Exynos W1000|Wearable Processor. Available online: https://semiconductor.samsung.com/processor/wearable-processor/exynos-w1000 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Wear OS by Google|The Smartwatch Operating System That Connects You to What Matters Most. Available online: https://wearos.google.com/intl/en_us/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Get Started with Wear OS|Android Developers. Available online: https://developer.android.com/training/wearables (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Shapely—Shapely 2.1.1 Documentation. Available online: https://shapely.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).