Abstract

Bloch-like surface waves (BLSWs) are electromagnetic waves generated at the interface between a dielectric medium and a photonic crystal. BLSWs have significant potential for sensing applications, since their electromagnetic fields are tightly confined near the interface, reaching comparable sensitivities to those of surface plasmon polariton (SPP)-based devices, but with higher figures of merit (FOM). This work explores a sensor based on BLSW at the interface formed by a TiO2 thin film deposited on the flat surface of a laterally polished photonic crystal fiber (PCF). The performance of the sensor is studied when the TiO2 film is partially removed, transforming the nanolayer into a nanostrip. The results of this study contribute to the optimization of the sensing performance of the proposed structure.

1. Introduction

Electromagnetic surface waves (ESWs) have been widely studied in the development of label-free optical sensors due to their high sensitivity to variations in the refractive index (RI) of a medium adjacent to the propagation interface [1,2]. Among them, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is the most widespread technology, thanks to its strong coupling with the surrounding medium and its ability to detect RI changes in the range of 10−7 RIU [3,4,5,6]. However, intrinsic losses in metals lead to undesirable resonance broadening, which limits the achievable figure of merit (FOM) and restricts sensor performance optimization [7].

A promising alternative is represented by Bloch surface waves (BSWs), generated at the interface between a dielectric medium and a photonic crystal [8,9]. In particular, Bloch-like surface waves (BLSWs) share many characteristics with BSWs, but their electromagnetic field confinement is not necessarily tied to the periodicity of the photonic crystal. This property offers greater flexibility in sensor design and has been demonstrated in side-polished PCF configurations, where a single dielectric layer enables BLSW excitation without strict dependence on the PCF’s periodic structure [10,11,12]. This property results in most of the electromagnetic energy being tightly confined near the interface and, consequently, to any surrounding material, enabling sensitivities comparable to or higher than SPR-based devices, but with narrower resonance peaks and higher FOM values. Recent studies have shown that BLSW-based sensors can achieve ultra-high FOMs while maintaining excellent sensitivity, making their design optimization especially valuable. For instance, Gonzalez-Valencia et al. (2024) reported ultra-high FOMs in side-polished PCF configurations with low-loss dielectric layers [10], Gryga et al. (2023) demonstrated cavity-mode resonance enhancements in BSW systems achieving ultra-high sensitivity and FOM [13], Dias et al. (2023) experimentally achieved sensitivities of ~840 nm/RIU in TE and TM BSW modes [14], and Wei et al. (2023) designed a guided-mode Bloch detection scheme with maximum sensitivity reaching 4380°/RIU [15].

In fiber optics, photonic crystal fibers (PCFs) provide an ideal platform for BLSW excitation, owing to their periodic air-hole microstructure, which behaves as a two-dimensional photonic crystal. Through lateral polishing (D-shaping), a flat surface close to the core is obtained, onto which a high-refractive-index, low-extinction-coefficient dielectric layer can be deposited, thus tuning the coupling between the guided mode and the surface mode. This approach combines the mechanical robustness and versatility of PCFs with the ability to optimize key parameters such as resonance wavelength and sensitivity by selecting the material and thickness of the coating layer [16,17,18].

In this work, we investigate the performance of refractometric sensors based on BLSWs at the interface between a TiO2 thin film and the flat surface of a laterally polished photonic crystal fiber (PCF). The periodic air-hole microstructure of the PCF cladding acts as a two-dimensional photonic crystal, while the dielectric nanolayer modifies the local effective refractive index, enabling direct manipulation of BLSWs. The study evaluates sensor performance when the TiO2 film is partially removed, forming a nanostrip, and analyzes its influence on key sensing parameters such as sensitivity, full width at half maximum (FWHM), and FOM. The results contribute to optimizing the sensing performance of the proposed structure, with a view toward the development of compact, high-performance biosensors.

2. Materials and Methods

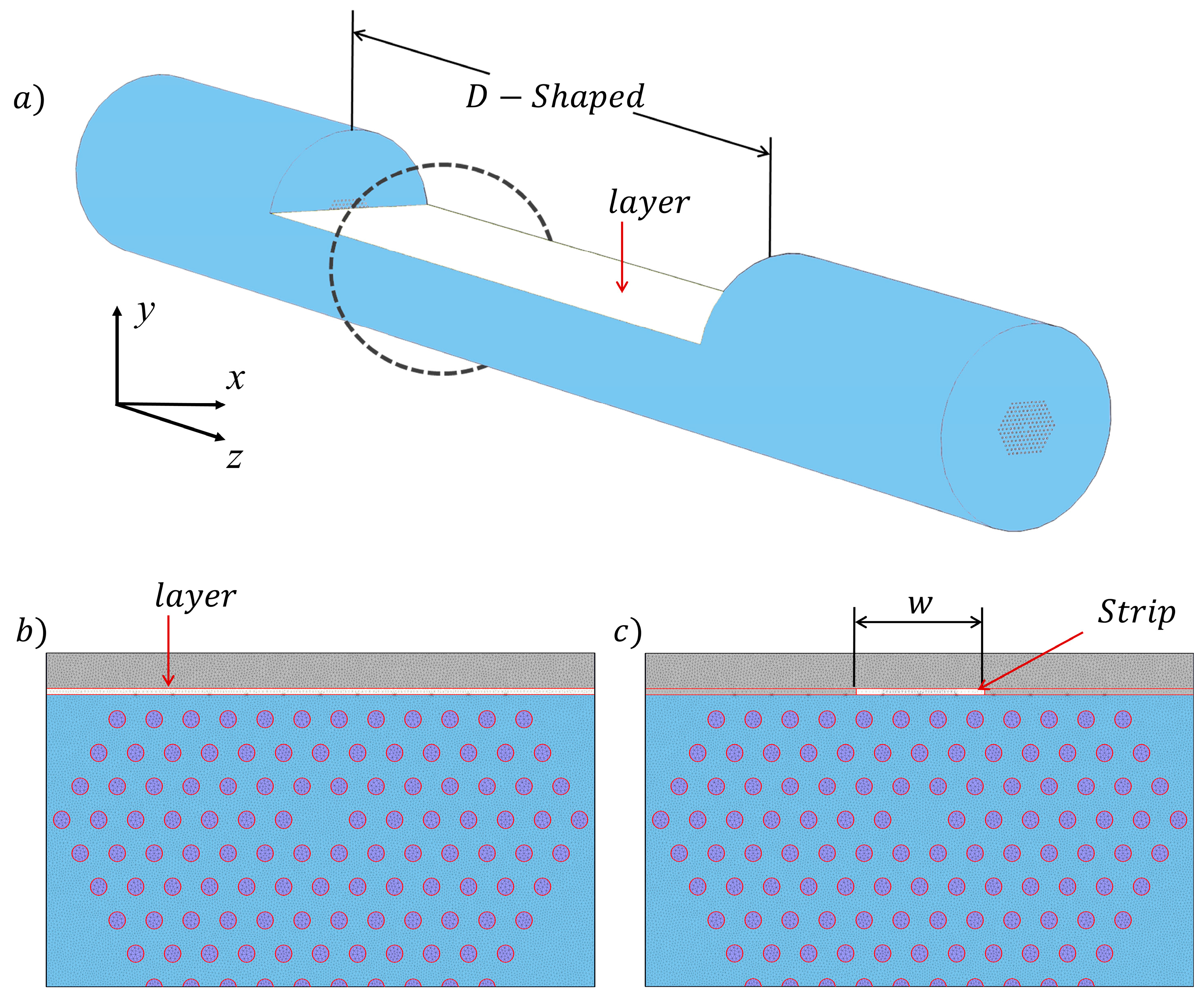

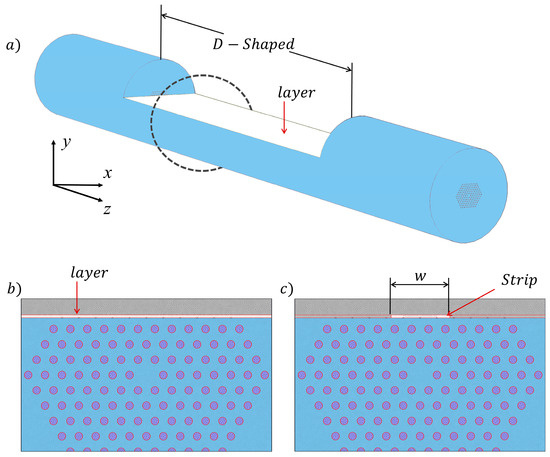

The proposed sensor is based on the commercial optical fiber from NKT Photonics (Birkerød, Denmark), PCF LMA-05. The cross-section of the PCF consists of a hexagonal array of holes, with a fiber pitch of Λ = 2.9 µm and a filling ratio d/Λ = 0.44 [17]. The fiber must be laterally polished until it acquires the D-shaped form [18,19,20] with three rows of holes remaining between the fiber core and the polished section, as shown in Figure 1a. The interface between the external medium and the polished fiber acts as an interface between a dielectric medium and a two-dimensional photonic crystal, respectively, creating the necessary conditions to excite a BLSW. Finally, a dielectric layer of 31 nm thick of TiO2, a material of high refractive index and low extinction coefficient, is deposited on the polished surface of the D-shaped fiber, as shown in Figure 1b. The function of this coating layer is to enable the tuning of the TE-BLSW, until it can be excited by the evanescent field of light traveling through the core of the fiber [10]. The design of the structure was chosen following the design standards established in reference [10], so that the conditions for the light traveling through the core to excite the TE-BLSW mode at a wavelength of 1500 nm are met, and only the TE-polarization was considered, since it presents higher sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the proposed sensor: (a) D-shaped structure; (b) D-shaped sensor cross-section with the coating layer; (c) D-shaped sensor cross-section with the nanostrip.

The air holes help reach the necessary conditions for its excitation. At the same time, the air-hole configurations spatially confine the mode to the central region of the coating layer. This work explores the effects of partially removing the TiO2 layer from the whole fiber diameter of the PCF (which in this case will be equivalent to 45 µm due to the lateral confinement of the BLSW modes) to give a TiO2 width of 10 µm, as shown in Figure 1c.

The computational methodology was implemented in FIMMWAVE, and the propagation was analyzed with the module FIMMPROP. The simulated structure consists of the standard PCF section, followed by the D-shaped section with the coating layer, and finally, another standard PCF section. The modes supported for each section are calculated by FIMMWAVE using the finite element method (FEM), while the propagation is calculated by FIMMPROP using the eigenmode expansion method (EME).

3. Results and Discussion

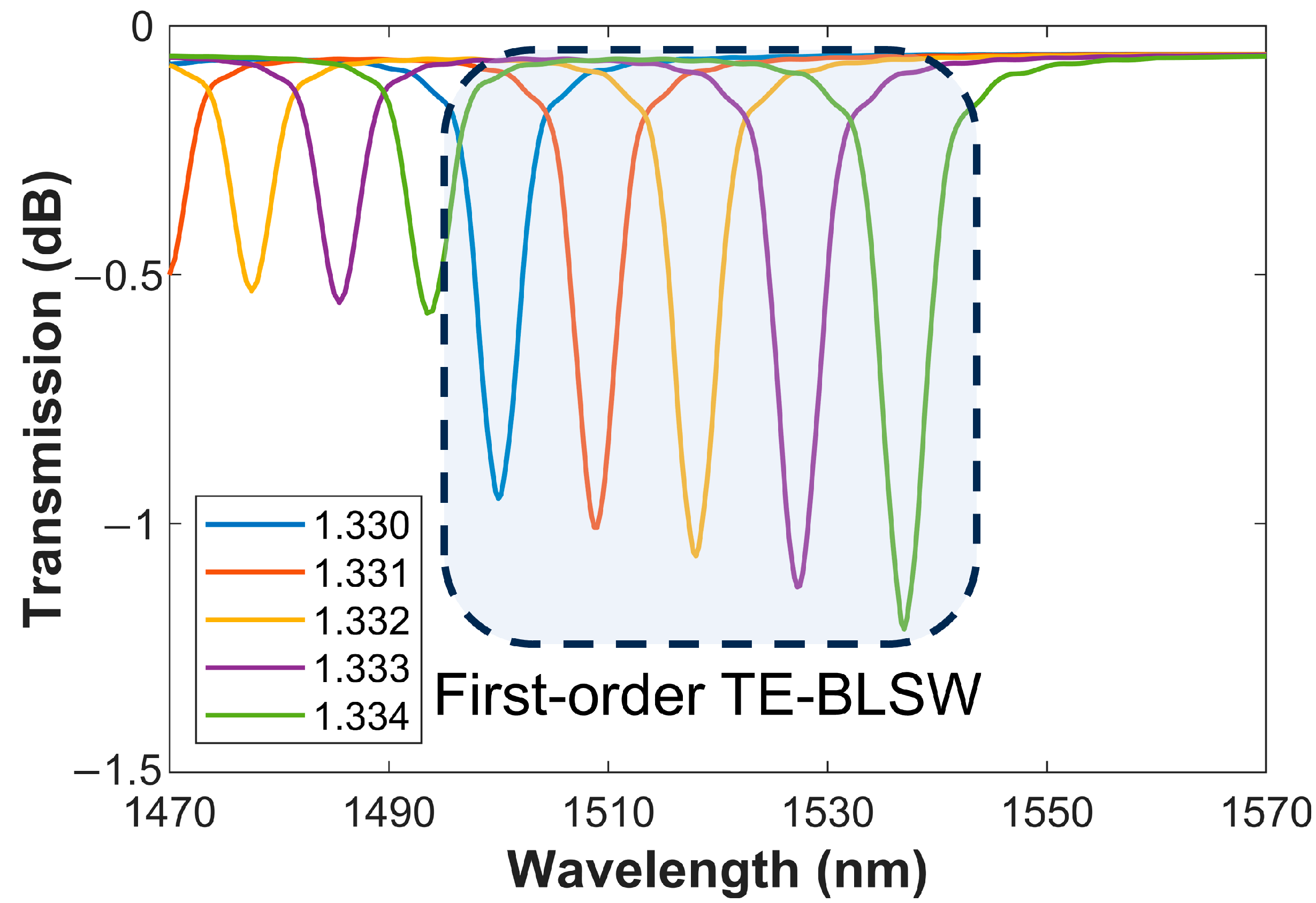

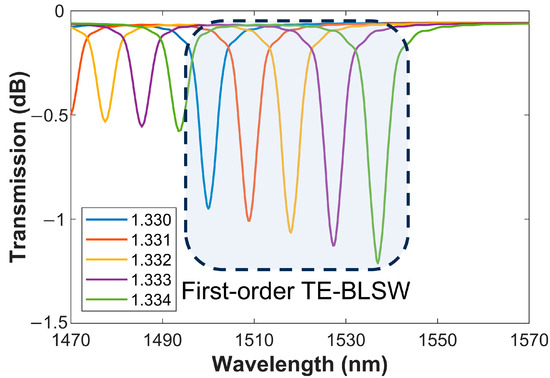

The refractometric response of this sensing configuration was tested considering external media with refractive index from 1.330 to 1.334, a range of special interest for biological and chemical substances. Figure 2 shows the transmission spectra for each analyzed configuration, where it can be identified that each transmission spectra has two resonances peaks. In this study, we will focus on the deeper peak, which corresponds to the first-order TE-BLSW, since it will be easier to detect in a potential experimental verification. It can be observed that the resonance peaks shift to longer wavelengths when the refractive index of the external media increases; then, following the spectral position of this resonance peaks, refractive index measures can be performed.

Figure 2.

Refractometric response of the proposed sensing configuration with a 20 mm long D-shaped section for TE-BLSW.

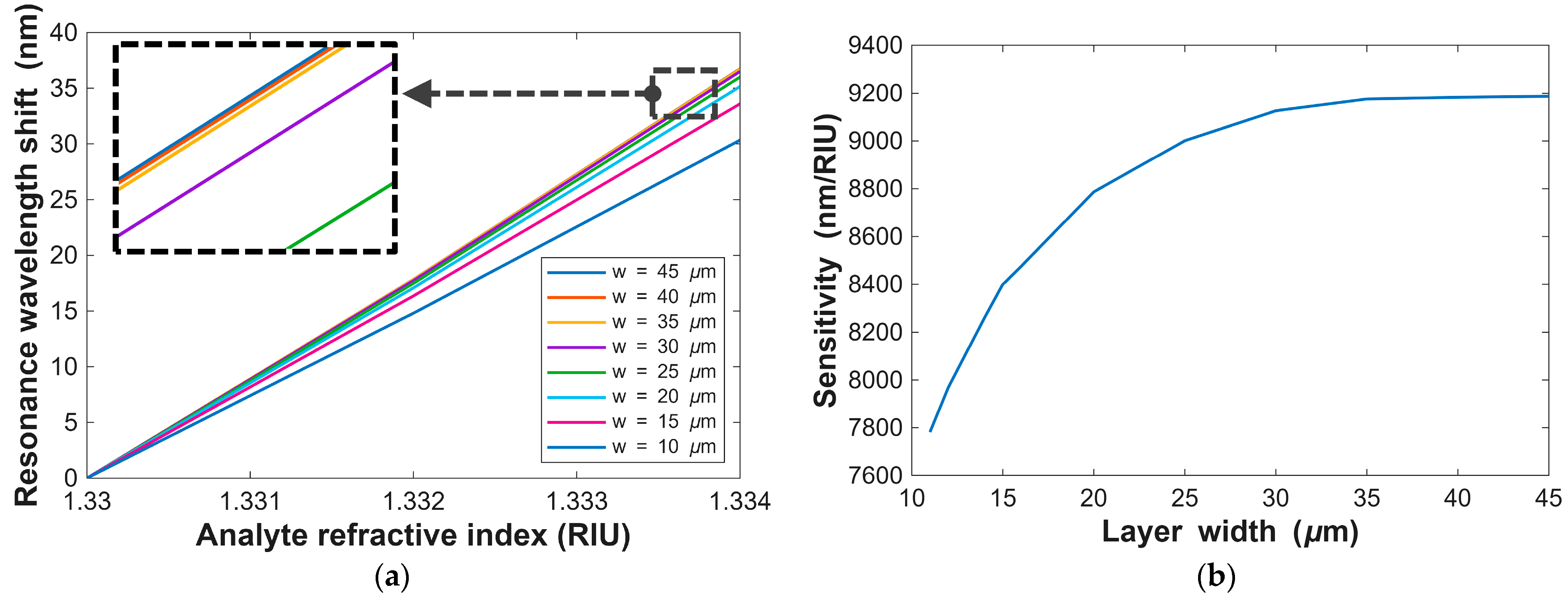

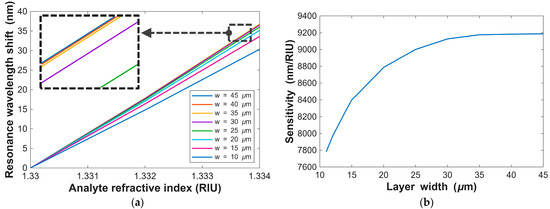

The resonance wavelength shift as a function of the analyte refractive index is presented in Figure 3a, where it can be established that, in the considered range (of special interest for biological applications), this relationship is approximately linear. To establish the impact of turning the coating layer into a nanostrip, the width of the TiO2 layer was reduced from 45 µm to 10 µm. It can be seen that as the layer width is reduced, smaller resonance wavelength shifts are obtained, which is reflected in the sensitivity of the structure, defined as . The sensitivity analysis as a function of the layer width is presented in Figure 3b, where it is clear that reducing the layer to a nanostrip negatively affects sensitivity, one of the main characteristics of a refractometer.

Figure 3.

Refractometric response analysis: (a) resonance wavelength shift as function of analyte refractive index; (b) sensitivity as function of the coating layer width.

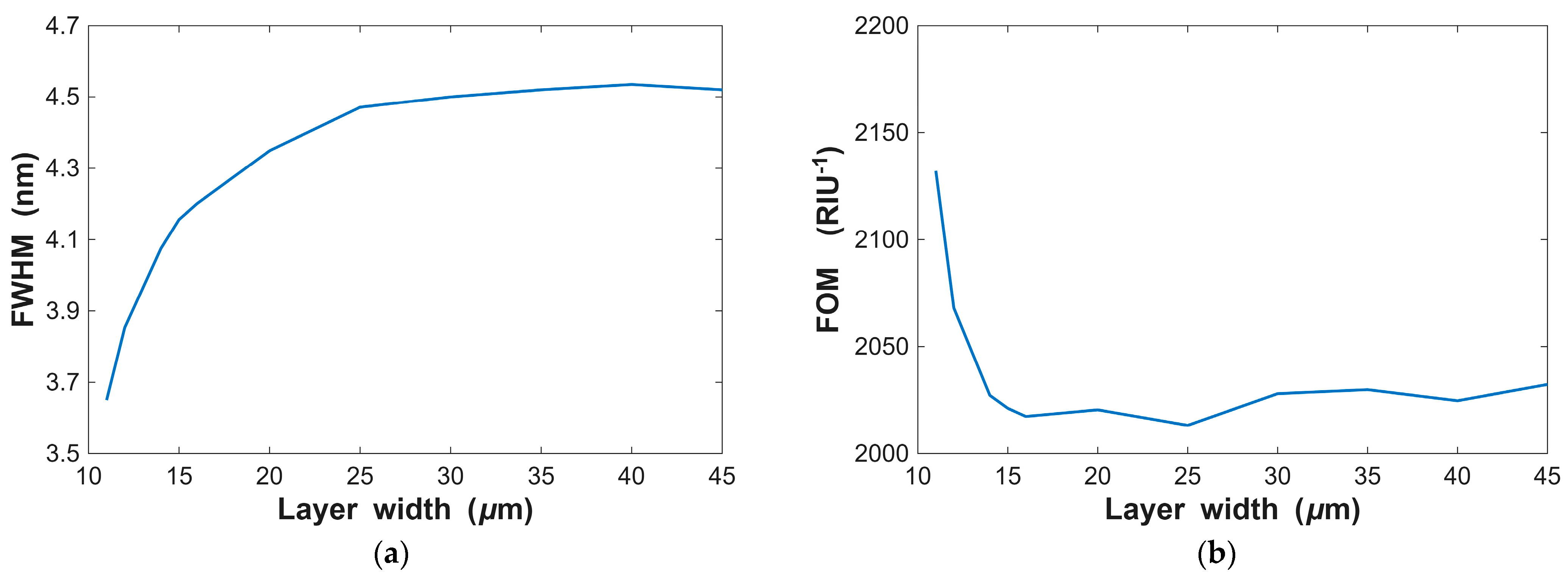

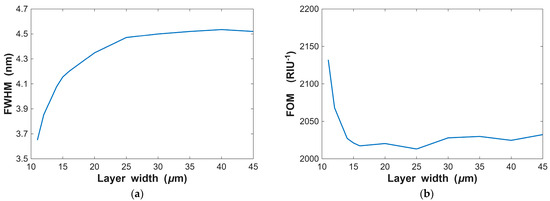

Besides the sensitivity, refractometric sensors have more parameters that impact their performance, as the FOM depends on the FWHM of the resonance peak, and it can be defined as . FOM is often used as a way to assess the performance of an optical device, and it is an important characteristic to evaluate the performance of a resonant sensor [1,21]. The average value of the FWHM of the resonance peaks is presented in Figure 4a, which decreases with layer width, making the peak increasingly distinguishable. On the other hand, Figure 4b presents the FOM of the sensing configuration, which is approximately constant, except for strip widths lower than 15 µm (for the smaller values of FWHM), a condition where the FOM dramatically increases.

Figure 4.

Refractometric analysis of the D-shaped sensor: (a) FWHM; (b) FOM.

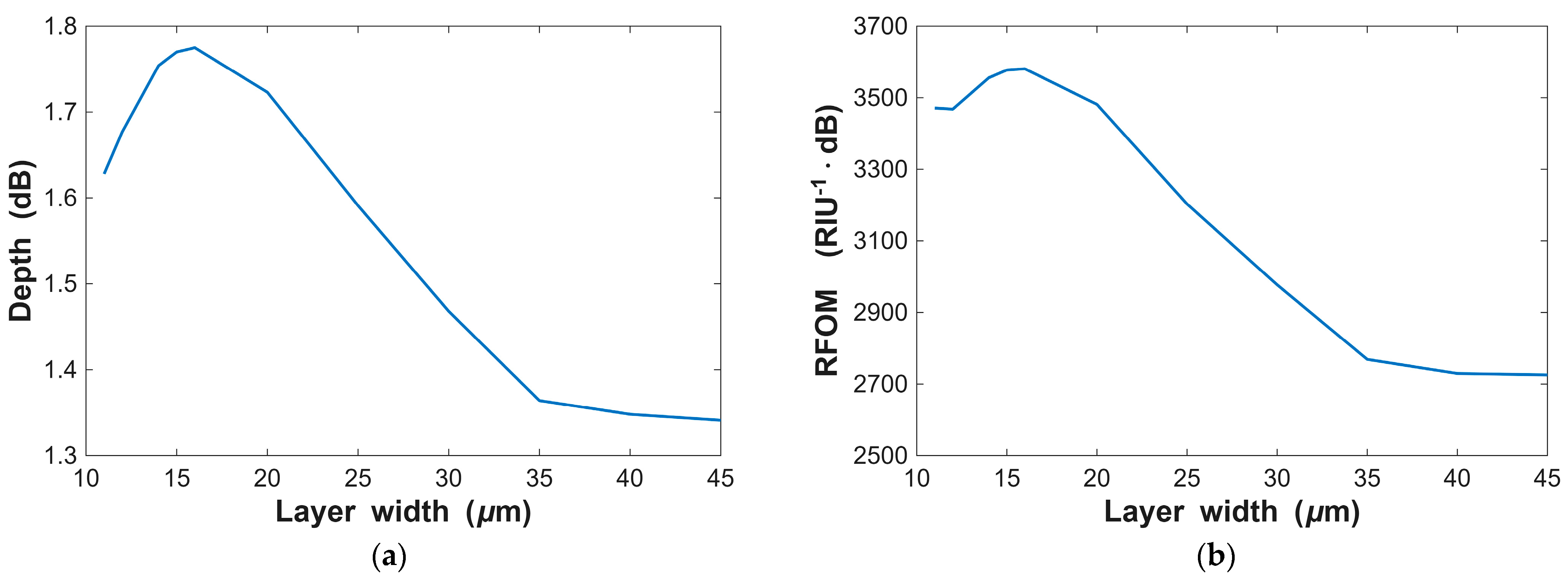

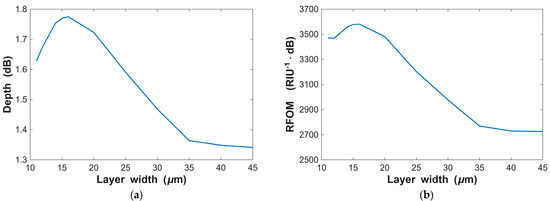

However, some authors claim that the FOM of a sensor is not the best parameter to assess the performance of a sensor under realistic conditions, and that instead the parameter RFOM is more accurate. RFOM is calculated as the product of the FOM and the depth of the resonance peak in dB. Figure 5 shows that depth of the resonance peaks tends to increase when the strip width is reduced, and then, increases the RFOM. However, for strip widths under 15, the tendency changes, leading to stagnation in the RFOM parameter.

Figure 5.

Refractometric analysis of the D-shaped sensor: (a) resonance depth; (b) RFOM.

The decrease in the FWHM of the resonance peaks is explained as follows: by laterally confining the resonance modes, the excitation conditions for the BLSW modes become increasingly more demanding, and therefore, the resonance peaks become narrower. Furthermore, this lateral confinement of the modes causes these resonant modes to increase their evanescent field in a perpendicular direction (“y” axis shown in Figure 1a), thus making the peaks deeper. In turn, as the evanescent field increases, the BLSW modes increasingly interact with optical fiber material, and therefore their effective index increases, which causes the resonance wavelength to shift towards the visible. This wavelength shift implies a natural decrease in the evanescent field (because of the shorter wavelengths), leading to a decrease in the depth of the resonances obtained, and therefore, a stagnation in the RFOM.

4. Conclusions

This work consolidates surface electromagnetic waves as a technology with enormous potential for the development of novel sensors. Their integration with highly mature technologies, such as PCFs, has expanded the possibilities, with BLSW-based sensors demonstrating this potential. These sensors stand out for their high sensitivity and ultra-high FOM, which can be improved through optimization, and can be considered as high-potential alternatives to sensors based on traditional technologies. This work has explored how small variations in the geometry of the proposed device can influence—both positively and negatively—the response as a refractometer. It was found that it is not always possible to optimize all of the device parameters to improve its sensing performance, but with a thorough analysis, it is possible to identify the configuration with the best balance between Sn, FOM, and RFOM.

Author Contributions

N.C.L.-D.: methodology, visualization, software, data curation, and writing—review and editing. J.A.M.-C. and E.G.-V.: conceptualization, investigation, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing, formal analysis, and project administration. N.G.-C. and P.T. conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing, formal analysis, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano, project P23210, the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias de la sede Medellín (Hermes code 56330).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Del Villar, I.; Gonzalez-Valencia, E.; Kwietniewski, N.; Burnat, D.; Armas, D.; Pituła, E.; Janik, M.; Matías, I.R.; Giannetti, A.; Torres, P.; et al. Nano-Photonic Crystal D-Shaped Fiber Devices for Label-Free Biosensing at the Attomolar Limit of Detection. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2310118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzert, P.; Danz, N.; Sinibaldi, A.; Michelotti, F. Multilayer Coatings for Bloch Surface Wave Optical Biosensors. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 314, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homola, J.; Piliarik, M. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensors. In Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Sensors; Homola, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 45–67. ISBN 978-3-540-33919-9. [Google Scholar]

- Huraiya, M.A.; Razzak, S.M.A.; Tabata, H.; Ramaraj, S.G. New Approach for a Highly Sensitive V-Shaped SPR Biosensor for a Wide Range of Analyte RI Detection. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 15117–15123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Huraiya, M.A.; Raj, R.V.; Tabata, H.; Ramaraj, S.G. Ultra-Sensitive Refractive Index Detection with Gold-Coated PCF-Based SPR Sensor. Talanta Open 2024, 10, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, A.M.T.; Al-Tabatabaie, K.F.; Ali, M.E.; Butt, A.M.; Mitu, S.S.I.; Qureshi, K.K. U-Grooved Selectively Coated and Highly Sensitive PCF-SPR Sensor for Broad Range Analyte RI Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 74486–74499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliarik, M.; Homola, J. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensors: Approaching Their Limits? Opt. Express 2009, 17, 16505–16517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.-J.; Zhu, X.-S. Optical Fiber Sensor Based on Bloch Surface Wave in Photonic Crystals. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 16016–16026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinibaldi, A.; Danz, N.; Descrovi, E.; Munzert, P.; Schulz, U.; Sonntag, F.; Dominici, L.; Michelotti, F. Direct Comparison of the Performance of Bloch Surface Wave and Surface Plasmon Polariton Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 174, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Valencia, E.; Reyes-Vera, E.; Del Villar, I.; Torres, P. Side-Polished Photonic Crystal Fiber Sensor with Ultra-High Figure of Merit Based on Bloch-like Surface Wave Resonance. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 169, 110129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Valencia, E.; Villar, I.D.; Torres, P. Novel Bloch Wave Excitation Platform Based on Few-Layer Photonic Crystal Deposited on D-Shaped Optical Fiber. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryga, M.; Ciprian, D.; Hlubina, P. Bloch Surface Wave Resonance Based Sensors as an Alternative to Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryga, M.; Ciprian, D.; Hlubina, P. From Bloch Surface Waves to Cavity-Mode Resonances Reaching an Ultrahigh Sensitivity and a Figure of Merit. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 6068–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, B.S.; de Almeida, J.M.M.M.; Coelho, L.C.C. Refractometric Sensitivity of Bloch Surface Waves: Perturbation Theory Calculation and Experimental Validation. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, H.; Ge, D.; Zhang, L. Ultra-High Sensitivity Bloch Surface Wave Biosensor Design and Optimization. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2023, 40, 1890–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, A.; Del Villar, I.; Zubiate, P.; Zamarreño, C.R. A Comprehensive Review of Optical Fiber Refractometers: Toward a Standard Comparative Criterion. Laser Photonics Rev. 2019, 13, 1900094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbal, M.; Bouregaa, M.; Chikh-Bled, H.; Chikh-Bled, M.E.K.; Ouadah, M.C.E. Influence of Temperature on the Chromatic Dispersion of Photonic Crystal Fiber by Infiltrating the Air Holes with Water. J. Opt. Commun. 2019, 44, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Yin, Z.; Wang, L.; Geng, Y.; Hong, X. Characteristics of D-Shaped Photonic Crystal Fiber Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors with Different Side-Polished Lengths. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 1550–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Yao, J. Simultaneous Measurement of Refractive Index and Temperature Based on SPR in D-Shaped MOF. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 4369–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, J.; Rajan, D. Highly Sensitive D Shaped PCF Sensor Based on SPR for near IR. Opt Quantum Electron 2016, 48, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Valencia, E.; Herrera, R.A.; Torres, P. Bloch Surface Wave Resonance in Photonic Crystal Fibers: Towards Ultra-Wide Range Refractive Index Sensors. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).