Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are a major contributor to climate change, requiring sustainable carbon capture and utilization (CCU) strategies. This study employed density functional theory (DFT) to assess a choline chloride–lactic acid deep eutectic solvent (CHL–LAC DES) as a dual system for CO2 capture and gingerol extraction. Using the wB97X-D functional theory for energy calculation with PM3-optimized geometries, the DES exhibited stronger CO2 binding (–0.86 eV) than monoethanolamine (–0.234 eV) and a higher affinity for 6-gingerol (–1.87 eV). These results suggest that CHL–LAC DES can simultaneously capture CO2 and extract bioactive compounds, advancing green pharmaceutical and integrated CCU applications.

1. Introduction

The rising concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is a major contributor to global warming and climate change, primarily driven by industrial emissions and fossil fuel combustion [1]. To address this challenge, global research efforts have shifted toward carbon capture and utilization (CCU), which not only aims to capture CO2 but also to repurpose it into valuable products rather than merely storing it underground [2]. Through CCU, captured CO2 can be converted or utilized as a feedstock or solvent for the production of fuels, fine chemicals, and materials, thereby promoting a circular carbon economy [3].

In parallel, there has been increasing interest in green extraction technologies, particularly within the pharmaceutical and food industries. These processes seek to minimize the environmental impact of solvent use while enhancing the recovery of valuable bioactive compounds. Zingiber officinale (ginger) is well recognized for its pharmacological properties, primarily due to 6-gingerol, which is the most abundant bioactive compound known for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities [4]. It is important to note that solvent extraction is one of the conventional methods for producing gingerol, a promising therapeutic agent for various gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, including obesity, inflammation, diabetes, cancer, and functional GI disorders.

However, conventional extraction methods typically employ organic solvents such as ethanol, methanol, and acetone, which are often toxic, volatile, and energy-intensive [5]. Consequently, the development of safer, renewable, and efficient extraction media has become a critical goal in sustainable chemical processing [6,7].

Although significant progress has been made in both carbon capture and green solvent design, there remains a lack of integration between the two fields. Most studies address CO2 capture and bioactive compound extraction as independent research areas. Very few have explored the direct utilization of captured CO2 as a functional solvent or co-solvent to enhance extraction performance [8,9,10,11]. Moreover, while deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have demonstrated strong potential for natural compound extraction, their application in CO2-based extraction systems remains underexplored [12,13]. This knowledge gap limits the potential to merge CO2 utilization and natural product extraction into a unified, sustainable process.

This study seeks to bridge that gap by investigating the use of a choline chloride–lactic acid (CHL–LAC) deep eutectic solvent (DES) for CO2 capture and by evaluating the feasibility of utilizing the captured CO2 for the extraction of 6-gingerol (GIN) from ginger. The choice of CHL–LAC was based on reported edibility and toxicity data in the PubChem literature, which confirm its safety for applications involving consumable compounds such as gingerol. Density functional theory (DFT) is applied to model, optimize, and examine the formation mechanism and stability of DES–CO2 and DES–6-gingerol interactions. Additionally, molecular property analyses (that is, highest occupied molecular orbital—lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO–LUMO)) and interaction energy calculations are employed to evaluate the reactivity and affinity of the system components. By comparing the extraction capability of captured CO2 with that of ethanol, this research introduces a novel concept in which captured carbon serves as a green solvent medium. This approach not only advances CO2 utilization but also promotes the sustainable extraction of high-value bioactive compounds. Ultimately, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on carbon-based green solvent systems and provides a theoretical foundation for the future experimental validation and scale-up toward sustainable pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

2. Computational Resources and Methodology

2.1. Computational Resources

All computational simulations were performed using Spartan (v24 and v9) software, a well-established tool for molecular modeling and quantum chemical calculations. The program was installed on a Windows 10 operating system and executed on a laptop (HP 620 model, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an Intel Pentium® Dual-Core T4500 processor (2.30 GHz) and 6 GB of RAM. These specifications define the computational environment for all simulations. Spartan provided essential functionalities for the molecular modeling, geometry optimization, and quantum mechanical property evaluation, which formed the basis for analyzing molecular interactions in this study.

2.2. Computational Details

For each component, conformer calculations were performed to determine the lowest energy equilibrium conformer at the ground state using a parameterized method 3 (PM3) semi-empirical approach. The maximum number of conformers was set to 200 and a tolerance of 10−9. To account for dispersion effects and improve accuracy, a high-level density functional theory (DFT) method, wB97X-D/6-31G(D)*[3-21G*] with an SCF tolerance of 10−5, was employed in a vacuum. Calculations were initiated from PM3-optimized geometries using a dual-basis set to minimize dispersion errors [14] and ensure reliable energy evaluations in line with the reported procedure employed in the literature [15,16].

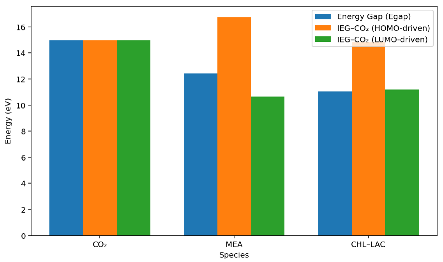

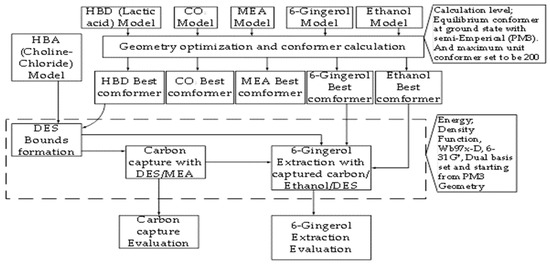

2.3. Study Strategy

A computational simulation approach was employed to model the deep eutectic solvent (DES) and examine its molecular interactions with CO2 and 6-gingerol. This study evaluated the carbon capture and extraction capacities of the solvents through quantum chemical calculations. The overall workflow for the simulation and analysis process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Complete strategic block flow diagram (Note the dash line indicated section where DFT energy calculations were carried out in the analysis).

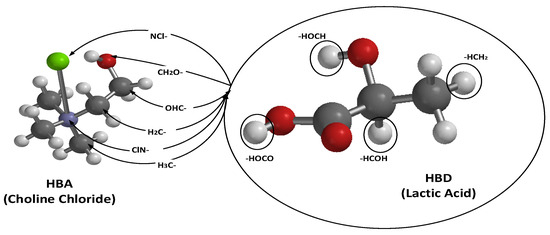

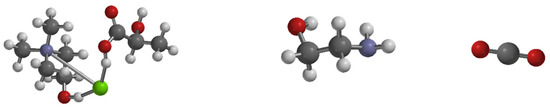

The molecular structures of the hydrogen bond donor (HBD), lactic acid (LAC), and the hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), choline chloride (CHL), were modeled and optimized. A conformer search was performed for the HBD to obtain the most stable conformer, and its molecular properties were evaluated. Subsequently, various possible interaction pathways between the two components were constructed, as illustrated in Figure 2. For example, the arrow labeled NCl– represents the chloride atom of the HBA interacting with all four active sites of the HBD (lactic acid). This approach was applied to all six active sites of the HBA, down to the interaction represented by the arrow labeled H3C–, where the carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms engages with the four active sites of the HBD. In total, 24 possible interaction pathways were explored.

Figure 2.

Demonstration of bonded interactions for HBA and HBD. Note: Green is chlorine atom, Gray is carbon atom, Purple is nitrogen atom, Red is oxygen atom, and White is hydrogen atom. The (-) was only indicating the interaction points through which the HBA and HBD interacts, while the circled white atoms indicated that potential hydrogen(H) in HBD that could be donated to HBA.

The formation energy (FE) of each pathway was calculated to identify the most stable DES structure for the subsequent extraction capacity evaluation. The FE was computed as FE = Eint − EHBA − EHBD, where Eint is the electronic energy of the CHL–LAC complex, EHBA is the electronic energy of choline chloride, and EHBD is the electronic energy of lactic acid. All electronic energies were reported in electron volts (eV). The pathway with the most negative FE value was identified as the most feasible formation mechanism, and the resulting stable DES structure was used to assess extraction performance in this study.

2.3.1. Interaction Analysis for Carbon Capture

Monoethanolamine (MEA) and CO2 were modeled, and conformer calculations were performed to identify interaction sites. CO2 was bonded with MEA and then with the DES, followed by energy calculations corrected for basis set superposition error (BSSE). The absorption capacity (AC) was evaluated as AC(CO2) = E(sol/CO2) − E(sol) − E(CO2), where E(sol/CO2), E(sol), and E(CO2) are electronic energies in eV. More negative AC values indicate higher CO2 affinity.

2.3.2. Interaction Analysis Between 6-Gingerol and Solvents (CO2 and DES)

The 6-gingerol molecule was modeled and optimized before interacting with CO2 and the DES. Binding energies, corrected for BSSE, were computed as EC(g) = E(sol/g) − E(sol) − E(g), where all energies are in eV. The most negative EC values correspond to stronger solvent–gingerol interactions and higher extraction capacity.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Evaluation of DES Component and Formation Mechanism

The higher occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy indicates the molecular power of the molecule to donate electrons in line with the literature reports [17,18]. Lactic acid (LAC) shows a HOMO energy of −10.18 eV, while choline chloride (CHL) exhibits −7.83 eV, as shown in Table 1. The lower HOMO energy of LAC indicates a stronger tendency to donate electrons, which agrees with Refs. [19,20]. The lower unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy determines the ability to accept electrons in the context of molecular orbital theory. LAC has a LUMO energy of 0.99 eV, while CHL presents 3.04 eV. This indicates that LAC can also act as an electron acceptor at the LUMO level, which is consistent with recent density functional theory (DFT) studies showing that LAC contributes both donor and acceptor roles in DES formations [19].

Table 1.

DES formation mechanism and DES component molecular formula (note: abs is absolute value).

The HOMO–LUMO energy gap (EGap) provides an indicator of molecular reactivity and stability, and it shows that CHL will be more reactive than LAC due to its shorter energy gap (10.87 eV), in agreement with the existing literature. Figure 3 shows the optimized structure for the CHL and LAC molecules.

Figure 3.

Optimized structure of DES components: Choline chloride—CHL (left) and lactic acid—LAC (right). Note: Green is chlorine atom, Gray is carbon atom, Purple is nitrogen atom, Red is oxygen atom, and White is hydrogen atom.

To evaluate the mode of interaction between CHL and LAC, the interaction energy gap (IEG) was determined. Findings from the results predict that CHL will feasibly donate electrons while interacting with LAC to form the DES (CHL-LAC) due to its shorter IEG (8.82 eV) compared to the wider IEG (13.22 eV) obtained for acting as an electron acceptor. After evaluating several possible interaction points, the most stable DES geometry in Figure 2 was obtained with FE (−1.92 eV) via NCl-HO(CO) formation pathways (more details are provided in the Supplementary Material—Table S1 and Figure S1), similarly to Ref. [15] that also obtained stable DESs across the -Cl in HBA and -H of OH groups in HBDs.

3.2. Molecular Property for Carbon Capture Using DES and MEA (Monoethanolamine)

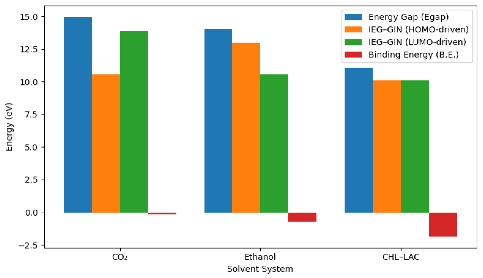

In evaluating the CO2 capture potential of the modeled DES, the interaction energy gap (IEG) was computed using the HOMO and LUMO energies to provide insight into the electron transfer behavior of the DES relative to the conventional solvent (MEA). The calculated molecular descriptors are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Molecular properties for carbon capture.

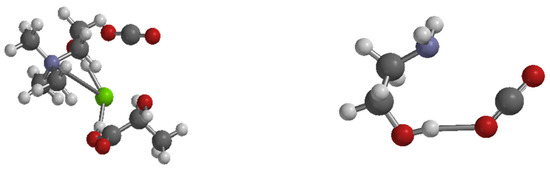

Figure 4.

Optimized structure of absorption solvents [CHL-LAC (left) and MEA (middle)] and CO2 (right). Note: Green is chlorine atom, Gray is carbon atom, Purple is nitrogen atom, Red is oxygen atom, and White is hydrogen atom.

An analysis of the results in Table 2 indicates that CO2 can feasibly interact with both the MEA and the DES as an electron acceptor, based on the relatively low IEG-CO2 values computed using their LUMO energies, in agreement with the literature [21]. This suggests that both solvents provide an energetically favorable pathway for CO2 capture.

However, a comparison of the interaction strengths shows that MEA (10.64 eV) would interact slightly more strongly with CO2 than the DES, while the CO2 interacts with its LUMO. This conclusion is supported by the small difference (0.55 eV) in their IEG-CO2 values derived from the individual molecular properties, implying that CO2 may more readily accept electrons from MEA compared to CHL–LAC under similar conditions.

Nevertheless, a more definitive understanding of the interaction strength and overall capture performance is provided later in this report, where direct CO2–solvent complexation energies and structural interaction analyses are presented.

3.3. Evaluation of Capturing Capacity of CO2

Following the earlier IEG analysis, which indicated that both MEA and the DES can feasibly interact with CO2, the binding energy evaluation provides a more conclusive measure of their actual capture performance. Binding energy reflects the stability of the CO2–solvent complex, with more negative values indicating stronger capturing capacity [11,16].

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, the DES exhibits a substantially more negative binding energy (−0.86 eV) than MEA (−0.23 eV). This higher magnitude of negative energy confirms that the DES binds CO2 more strongly than MEA. Thus, although MEA showed a slightly stronger electron acceptor tendency in the earlier molecular property analysis, the DES ultimately demonstrates a superior CO2 capture performance due to its stronger and more stable interaction with CO2. The optimized structures of these interactions are presented in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Carbon capture potential of different solvents.

Figure 5.

Optimized interaction structures of absorption solvent with CO2: DES-CO2 (left) and MEA-CO2 (right). Note: Green is chlorine atom, Gray is carbon atom, Purple is nitrogen atom, Red is oxygen atom, and White is hydrogen atom.

Findings from this study were consistent with previous DFT and experimental studies reporting enhanced CO2 capture performance for choline chloride-based DESs relative to other DESs and conventional solvents [15,17,18,19].

3.4. Evaluation Capacity of Gingerol Extraction

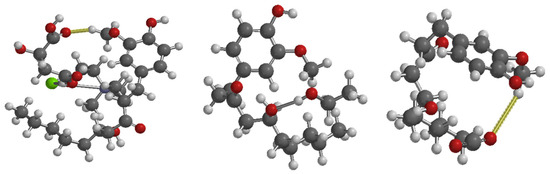

Building on the earlier analyses of molecular properties and interaction tendencies for CO2 capture, a similar approach was applied to assess the extraction potential of gingerol using CO2, ethanol, and the DES. The results obtained are collated and reported in Table 4 and Figure 6 (Geometrical structures) for the gingerol (GIN) extraction potential analysis for different selected solvents.

Table 4.

Binding energies and molecular properties for gingerol (GIN) extraction.

Figure 6.

Optimized interaction structures of gingerol with DES (left), ethanol (middle), and CO2 (right) (Note: Green is chlorine atom, Gray is carbon atom, Purple is nitrogen atom, Red is oxygen atom, and White is hydrogen atom).

The EGap values further demonstrate the relative reactivity of the systems. The DES exhibits a lower EGap (11.05 eV) than CO2 (14.98 eV) and ethanol (14.05 eV), suggesting that the DES is more chemically reactive and less electronically stable when interacting with gingerol, in line with the literature [17]. This mirrors the earlier CO2 findings, where the DES also demonstrated stronger reactive behavior leading to more stable complex formation.

The analysis of IEG-GIN values reinforces these observations. At both HOMO and LUMO evaluation levels, the DES shows lower IEG-GIN values than CO2 and ethanol, implying a more favorable interaction pathway between gingerol and the DES. Although, the interaction of DES-GIN was found to be more favorable when GIN was the electron donor (10.10 eV) compared to when it acts as an electron acceptor (10.12 eV). Though, there was no significant difference in the IEG-GIN. These results align with earlier findings that bioactive molecules often show enhanced donor–acceptor engagement in DES environments due to improved hydrogen bonding and charge delocalization [22,23].

To conclusively determine the solvent extraction capacity, similar to the approach used for CO2 capture where binding energy (BE) was employed in accordance with the existing literature [24,25,26] method, we explored it and obtained results reported in Table 4. The results show that the DES–gingerol complex exhibits the most negative binding energy (−1.87 eV), markedly stronger than ethanol–gingerol (−0.73 eV) and CO2–gingerol (−0.17 eV). This confirms that the DES forms the most stable complex with gingerol and therefore provides the highest extraction potential. This result agrees with previous studies showing an enhanced extraction performance of ginger bioactive components using choline–chloride-based DES systems [23].

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study employed computational modeling to assess the formation stability and functional performance of a choline chloride–lactic acid (CHL–LAC) deep eutectic solvent (DES) for CO2 capture and gingerol extraction. The formation energy analysis confirmed that the most stable DES structure resulted from favorable hydrogen bond interactions between the components. Molecular property evaluations (HOMO, LUMO, EGap, and IEG) showed that both MEA and the DES can interact feasibly with CO2; however, binding energy results provided a clearer distinction, revealing that the DES forms a significantly more stable CO2 complex than MEA. The more negative binding energy (−0.86 eV) demonstrates the superior CO2 absorption potential of the CHL–LAC DES, consistent with trends reported for choline–chloride-based solvents.

A similar analytical approach was applied to gingerol extraction, with results showing that gingerol acts as the electron acceptor during solvent interaction. Among the solvents assessed, the DES exhibited the highest reactivity and the most favorable interaction pathway, corroborated by the most negative binding energy (−1.87 eV). These findings indicate that CHL–LAC is a highly promising green solvent with dual functionality—showing a strong affinity for both CO2 capture and bioactive compound extraction. Overall, this study reinforces the potential of DESs as sustainable alternatives to conventional solvents in environmental and natural product processing applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/engproc2025117030/s1, Figure S1: A geometrical structure of the DES formed via the most feasible pathway (with the strongest formation energy); Table S1: Results for the formation energies obtained across the six DES formation pathways evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O.; methodology, T.O. and A.O.; software, T.O. and A.O.; validation, A.O.; formal analysis, A.O.; investigation, T.O. and A.O.; resources, T.O. and A.O.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O. and A.O.; writing—review and editing, T.O. and A.O.; visualization, T.O. and A.O.; supervision, T.O.; project administration, T.O.; funding acquisition, T.O. and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge to the support of Wavefunction Inc USA for the provision of a discounted license and the support of other members (Umar Mogaji Muhammed and Sharon Olorunfemi) of the Pencil Team and CEPRIs group.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine Scrubbing for CO2 Capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Ma, Y.; Ci, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Yang, W. Anhydrous deep eutectic solvents-based biphasic absorbents for efficient CO2 capture: Unravelling the critical role of hydrogen bond-mediated electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 161988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, E.G.; Aruxandei, D.C.; Doncea, S.M.; Oancea, F. Deep Eutectic Solvents for CO2 Capture in Post-Combustion Processes. Stud. UBB Chem. 2021, 2, 233–246. Available online: https://chem.ubbcluj.ro/~studiachemia/issues/chemia2021_2/20Mihaila_etal_233_246.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Semwal, R.B.; Semwal, D.K.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A.M. Gingerols and shogaols: Important nutraceutical principles from ginger. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belwal, T.; Ezzat, S.M.; Rastrelli, L.; Bhatt, I.D.; Daglia, M.; Baldi, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Orhan, I.E.; Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; et al. A critical analysis of extraction techniques used for botanicals: Trends, priorities, industrial uses and optimization strategies. Trends Anal. Chem. J. 2018, 100, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents—Solvents for the 21st Century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Branco, L.C.; Marrucho, I.M. Development of hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for extraction of pesticides from aqueous environments. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2017, 448, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Xu, S. Diluent Tailored quaternary deep eutectic solvents for energy efficient carbon capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Liang, Z.; Li, D.; Yang, F.; Tan, H.; Wang, X. Absorption characteristics of amine-based deep eutectic solvents for CO2 capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegoke, T.; Ademola, O.; Olusanya, J.J. Preliminary Investigation on the Screening of Selected Metallic Oxides, M2O3 (M = Fe, La, and Gd) for the Capture of Carbon Monoxide Using a Computational Approach. J. Eng. Sci. Comput. 2021, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ademola, O.; Oyegoke, T.; John Olusanya, J. Computational Study of CO Adsorption Potential of MgO, SiO2, Al2O3, and Y2O3 Using a Semiempirical Quantum Calculation Method. Niger. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 11, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanisz, M.; Stanisz, B.J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. A Comprehensive Review on Deep Eutectic Solvents: Their Current Status and Potential for Extracting Active Compounds from Adaptogenic Plants. Molecules 2024, 29, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Hühnert, J.; Schwabe, T. Evaluation of DFT-D3 dispersion corrections for various structural benchmark sets. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 044115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzochukwu, M.I.; Oyegoke, T.; Momoh, R.O.; Isa, M.T.; Shuwa, S.M.; Jibril, B.Y. Computational insights into deep eutectic solvent design: Modeling interactions and thermodynamic feasibility using choline chloride & glycerol. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 16, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegoke, T.; Aliyu, A.; Uzochuwu, M.I.; Hassan, Y. Enhancing hydrogen sulphide removal efficiency: A DFT study on selected functionalized graphene-based materials. Carbon Trends 2024, 15, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegoke, T.; Dabai, F.; Adamu, U.; Baba, Y.J. Quantum mechanics calculation of molybdenum and tungsten influence on the CrM-oxide catalyst acidity. Hittite J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendjeddou, A.; Abbaz, T.; Gouasmia, A.; Villemin, D. Molecular Structure, HOMO-LUMO, MEP and Fukui Function Analysis of Some TTF-donor Substituted Molecules Using DFT (B3LYP) Calculations. Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2016, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, M.; Kunzru, D.; Rabari, D. Understanding the interactions between CO2 and selected choline-based deep eutectic solvents using density functional theory. Fluid Phase Equilib. J. 2024, 580, 114038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.; Amjad, M.; Ahmad, F.; Muhammad, Z.; Arshad, I.; Roil, M.; Bilad, M.R.; Ayub, K.; Khan, A.L. Theoretical and experimental investigation of CO2 capture through choline chloride based supported deep eutectic liquid membranes. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 335, 116234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusola Ibraheem, A.; Toyese, O. DFT Fukui Descriptor-Based Prediction of Arsenic Adsorption on Graphene. Eur. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, M.; Islamčević Razboršek, M.; Kolar, M. Innovative Extraction Techniques Using Deep Eutectic Solvents and Analytical Methods for the Isolation and Characterization of Natural Bioactive Compounds from Plant Material. Plants 2000, 9, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzani, A.; Kalafateli, S.; Tatsis, G.; Rozaria, A.; Pontillo, N.; Detsi, A. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDESs) as Alternative Green Extraction Media for Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Sustain. Chem. 2021, 2, 576–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, P.; Asl, S.A.; Javadi, M.H.; Rezaee, S.; Morad, R.; Akbari, M.; Arab, S.S.; Maaza, M. DFT study on CO2 capture using boron, nitrogen, and phosphorus-doped C20 in the presence of an electric field. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, J.O.L.; del Castillo Vázquez, R.M.; Ramirez-de-Arellano, J.M. CO2 Absorption on Cu-Doped Graphene, a DFT Study. Crystals 2025, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, D.; Dengg, T.; Popov, M.N.; Holec, D. Interactions between a H2 Molecule and Carbon Nanostructures: A DFT Study. C 2020, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).