On the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu Car †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Wind Tunnel Facilities

2.2. Aerodynamic Drag Measurements

2.3. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) Measurements

2.4. Discussion of Experimental Results

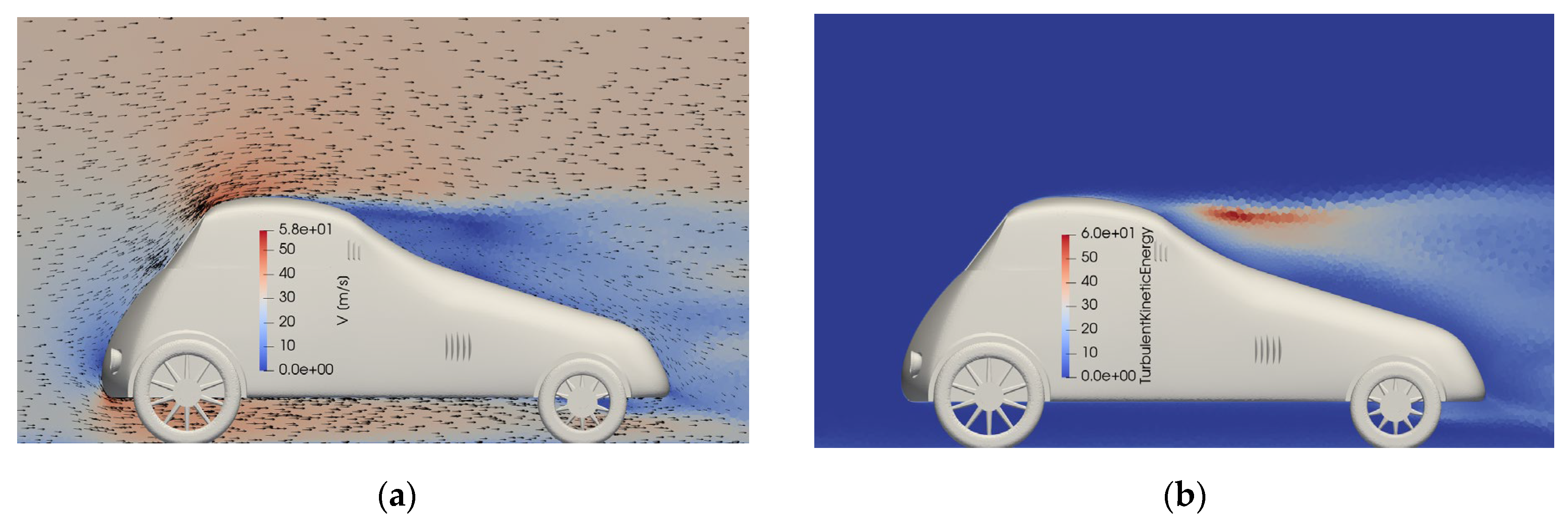

3. Numerical Simulations

- An upstream region with undisturbed flow containing approximately 2.3 million cells;

- A region surrounding the vehicle body with around 3.5 million cells;

- A wake region downstream of the vehicle with approximately 2.6 million cells.

4. Conclusions

- The measured drag coefficient of CD = 0.364 is significantly higher than the commonly cited value of 0.28, demonstrating the importance of experimental validation.

- Flow separation occurs shortly after the windshield, creating a substantial recirculation zone behind the cabin that extends over 25% of the vehicle length.

- CFD simulations (CD = 0.353) show good agreement with experimental results, with the small discrepancy attributed to delayed separation prediction by the RANS model.

- The vehicle’s aerodynamic performance is limited by suboptimal front geometry and roofline design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hucho, W.-H. Aerodynamic of Road Vehicle, 4th ed.; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Herkenrath, D. Vision EQXX–Innovative Chassis System for a Highly Efficient Electric Vehicle; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, P.; De Filippis, G.; Gruber, P.; Sorniotti, A. On the Benefits of Active Aerodynamics on Energy Recuperation in Hybrid and Fully Electric Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persu, A. Streamlined Power Vehicle. U.S. Patent No. 1,648,505, 8 November 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Iorga-Siman, V.; Clenci, A.-C.; Niculescu, R.; Badea, A. CFD Study on Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu’s Car. In Proceedings of the 17th European Automotive Congress/32nd SIAR International Congress on Automotive and Transport Engineering/3rd Motor Vehicle and Transportation Conference (EAEC-MVT), Timisoara, Romania, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev, I.; Massouh, F. Investigation of Relationship between Drag and Lift Coefficients for a Generic Car Model. In Proceedings of the BULTRANS-2014, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 17–19 September 2014; pp. 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, J.; Ewald, B. Turbulence Manipulation to Increase Effective Reynolds Numbers in Vehicle Aerodynamics. AIAA J. 1989, 27, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, B.; D’Auteuil, A. A System for Simulating Road-Representative Atmospheric Turbulence for Ground Vehicles in a Large Wind Tunnel. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars Mech. Syst. 2016, 9, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttasirisuk, N.; Munikanon, P.; Ajavakom, N.; De Silva, P.; Phanomchoeng, G. Simulation-Guided Aerodynamic Design and Scaled Verification for High-Performance Sports Cars. Modelling 2025, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolowicz, C.H.; Bowman, J.S.; Gilbert, W.P. Similitude Requirements and Scaling Relationships as Applied to Model Testing; NASA Technical Paper 1435; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1979.

- Cano, S.; Sierra, J.; Múnera, J.; Hincapie, D. Determination of velocity fields using the PIV technique. In Proceedings of the 2019 XXII Symposium on Image, Signal Processing and Artificial Vision (STSIVA), Bucaramanga, Colombia, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Charonko, J.J.; Vlachos, P.P. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) uncertainty quantification using moment of correlation (MC) plane. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.; Amandolese, X.; Aider, J.L. Drag reduction on the 25° slant angle Ahmed reference body using pulsed jets. Exp. Fluids 2012, 52, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; LV, B.J.; Su, Y.S.; Song, Q.; Lian, H.B. Numerical Study of flow around two teardrop cylinders in tandem arrangement at low Reynolds number. Therm. Sci. 2025, 29, 2743–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Ricci, A.; Blocken, B. CFD simulation of aerodynamic forces on the DrivAer car model: Impact of computational parameters. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 248, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.M.; Cheah, S.C. Wall y+ strategy for dealing with wall-bounded turbulent flows. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applications of Porous Media, Istanbul, Turkey, 25–29 August 2008; pp. 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, L. CFD Streamlined Bodies Simulation and Optimization for Natural Laminar Flow Provided by STAR-CCM+ and HEEDS Software. Ph.D. Thesis, Polytechnic University of Turin, Turin, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- El Gharbi, N.; Absi, R.; Benzaoui, A.; Amara, E.H. Effect of near-wall treatments on airflow simulations. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computational Methods for Energy Engineering and Environment, Sousse, Tunisia, 20–22 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev, I.; Massouh, F.; Danlos, A.; Todorov, M.; Punov, P. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Flow Field around a Small Car. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 133, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igali, D.; Mukhmetov, O.; Zhao, Y.; Fok, S.C.; Teh, S.L. Comparative Analysis of Turbulence Models for Automotive Aerodynamic Simulation and Design. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2019, 20, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.E.; Dias, R.R.; Almeida, O.; Proenca, A.R. Experimental and numerical investigation of scale effects on flow over a sedan vehicle. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2025, 114, 1149–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Clenci, A.; Danlos, A.; Dobrev, I.; Iorga-Simăn, V. On the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu Car. Eng. Proc. 2026, 121, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121029

Clenci A, Danlos A, Dobrev I, Iorga-Simăn V. On the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu Car. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 121(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121029

Chicago/Turabian StyleClenci, Adrian, Amélie Danlos, Ivan Dobrev, and Victor Iorga-Simăn. 2026. "On the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu Car" Engineering Proceedings 121, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121029

APA StyleClenci, A., Danlos, A., Dobrev, I., & Iorga-Simăn, V. (2026). On the Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Aurel Persu Car. Engineering Proceedings, 121(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025121029