Abstract

Many individual wastewater streams exhibit imbalanced or poor nutrient profiles, limiting their suitability for efficient biological treatment. In regions where several agro-industrial activities coexist, these streams are often produced in small volumes and vary considerably in composition, making their combined use an effective way to obtain a more balanced influent. This study aimed to identify the optimal mixing ratio of two agro-industrial wastewaters, second cheese whey (SCW) and poultry wastewater (PW), for the cultivation of a Leptolyngbya-dominated consortium. Four mixing ratios of SCW:PW (50:50%, 60:40%, 70:30%, and 85:15%) were examined based on an initial dissolved chemical oxygen demand (d-COD) concentration of 3000 mg L−1. The 70:30% ratio was led to significant biomass production (268.3 mg L−1 d−1), while simultaneously exhibiting the highest lipid content (14.0% d.w.), and the highest removal of d-COD (89.2%), total nitrogen (64%) and PO43−-P (60%). Overall, the experiments showed that using nutritionally balanced wastewater streams is a promising strategy to enhance biological treatment efficiency and lipid production.

1. Introduction

Wastewater streams are commonly used as low-cost nutrient sources for cultivating microalgae and cyanobacteria. However, individual streams may be nutritionally inadequate to support optimal growth [1]. To enhance the nutrient profile, strategies such as nutrient external supplementation (i.e., glucose, starch) or blending different wastewaters are applied [2]. Mixing wastewaters with complementary physicochemical properties can not only balance nutrients but also eliminate the need for external supplementation, thereby reducing the overall cultivation costs in large-scale units. Furthermore, optimizing the mixing ratio is essential to achieve favorable carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratios, enhance biomass and biocompound production, and improve operational culture conditions, such as turbidity and pH [3,4,5].

At present, the prevailing approach in microalgae wastewater treatment involves blending industrial or agro-industrial effluents with municipal wastewaters [6,7,8,9]. Livestock wastewaters containing high concentrations of ammonia may also be diluted with carbon-rich effluents emerging from different stages of food processing, consequently improving the nutrient balance of the resulting mixtures [4,10,11]. An alternative approach involves the co-treatment of wastewater streams emerging within the production chain of the same food product [4,12,13,14]. Regarding the treatment of different agro-industrial wastewater mixtures, the literature review indicates that the research in this area is still limited. Table S1 presents a synoptic review of the available research employing mixed agro-industrial wastewater streams as cultivation medium for microalgae. According to Table S1 the mixtures being combined originate from the food industry and the livestock sector. Moreover, the wastewaters may have been subjected to anaerobic digestion [15,16,17] or extensive pretreatment (i.e., sterilization, filtration, centrifugation) [4,11,12,16,17,18,19], while the species most frequently employed in such studies is Chlorella. Therefore, the research should investigate a broader range of microalgae/cyanobacteria species or even mixed microalgae/cyanobacteria–bacteria consortia. Mixed microbial communities of this type are of great interest, as they constitute dynamic systems with diverse pollutant-assimilation capabilities, ultimately exhibiting high removal efficiencies and biomass production.

The dairy industry, and cheese factories in particular, is a rapidly expanding sector, resulting in high volumes of wastewater that must be treated to prevent the pollution of surface and groundwater resources [15]. The main by-products of the cheese-making process are cheese whey and second cheese whey (SCW). SCW is obtained when cheese whey undergoes additional thermal treatment for the production of soft cheeses, like Ricotta and Mizithra. SCW contains high levels of organic load, vitamins, trace elements, lipids, and inorganic salts, representing a promising medium to support and enhance microalgae growth [20,21]. It should be noted that although SCW remains highly polluted, retaining approximately 60% of the original milk composition, its biological treatment using microalgae/cyanobacteria or mixed microbial consortia is still limited [22,23].

Poultry farming constitutes the third largest sector of the livestock industry. Poultry wastewaters (PWs) are rich in organic and especially inorganic pollutants. Their over-application on soils or uncontrolled run-off can cause a range of environmental hazards and raise serious public health concerns due to the presence of pathogens [24]. Moreover, PW may provide suboptimal growth conditions for microalgae/cyanobacteria due to high ammonia concentrations and antibiotic toxicants. Therefore, severe dilution or anaerobic digestion is frequently required prior to cultivation [24].

In this context, the present study aimed to optimize the biological treatment of a blend of two agro-industrial effluents, SCW and PW. Beyond SCW being carbon-rich and PW being nitrogen-rich, their complementary physicochemical characteristics make mixing an effective way to obtain a more balanced and cultivation-friendly medium. Therefore, different mixing ratios were examined to improve nutrient stoichiometry, turbidity, and pH, creating more favorable conditions for microbial growth and metabolite production. A mixed microbial consortium was used for the biotreatment of the wastewaters. The microbial consortium was dominated by the cyanobacterium Leptolynbgya sp. This strain, until recently, had not been extensively studied. However, due to its rapid biological cycle, robustness, and ability to produce high biomass concentrations, thus enabling large-scale production, it has now attracted significant research interest. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to investigate this specific wastewater mixture employing a Leptolyngbya-based microbial consortium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Characteristics

SCW originated from a local dairy facility in Agrinio, Western Greece. The SCW was collected before being mixed with the unit’s wash waters. The samples were collected at different time points and from the same discharge outlet of the unit’s secondary whey stream, aiming to represent the most realistic wastewater composition, as variations in raw milk may lead to differences. The wastewater exhibited an acidic pH (5.0–6.2), elevated electrical conductivity (5.8–6.4 mS cm−1), and high total suspended solids (TSS; 7.3–10.4 g L−1). Organic load was substantial, with dissolved chemical oxygen demand (d-COD) ranging from 45,960 to 49,700 mg L−1 and biological oxygen demand (BOD) from 28,500 to 30,169 mg L−1. Concerning nitrogen and phosphorus concentration, nitrate (N) and phosphate (P) concentrations ranged from 193.0 to 229.0 mg L−1 and 69.0 to 197.0 mg L−1, respectively.

Poultry wastes originated from small, local egg-laying farms in Western Greece. The wastes were obtained in different seasons and at different times of the day, aiming to examine a variety of the unit’s operating conditions. The PW extracts were obtained after sun-drying (48 h), wet-milling (15% w/v) and tulle-netting the manure, as described by Patrinou et al. [24]. The raw PW presented d-COD, NO3−-N, and PO43−-P concentrations within the ranges of 10.0–18.9 g L−1, 0.374–0.393 g L−1, and 0.312–0.329 g L−1, respectively, while a comprehensive composition of the PW is provided in the study of Patrinou et al. [24]. The pH of PW exhibited a slight alkalinity, with values ranging from 7.7 to 8.2 [24].

2.2. Culture Conditions and Experimental Set-Up

A microbial consortium dominated by the filamentous cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. (95% abundance) was isolated and identified, as described by Patrinou et al. [24]. The rest of the biomass contained a Choricystis-like coccoid microalga. The Leptolyngbya sp. culture was used as inoculum for the treatment of the mixed agro-industrial effluents. The inoculum was cultivated using a chemical medium [24] under stable phototrophic conditions of 24: 0 h L:D illumination of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (fluorescent lamps, 25–29 W m−2), at a temperature of 26 ± 2 °C and pH 7. Both SCW and PW were used raw, and thereby retained their native microbial communities. After their inoculation into the unsterilized wastewaters, a mixed microalgal/cyanobacterial-bacterial consortium was established. Microscopic observations at the end of the bioprocesses revealed that Leptolyngbya sp. dominated in the overall microbial biomass. This indicated synergistic interactions between the autotrophic and heterotrophic microorganisms of the consortium which promoted Leptolyngbya growth. Under such synergistic and mixotrophic conditions, microorganisms can efficiently exploit organic and inorganic nutrients, promoting both treatment efficiency and biomass production [25,26].

The experiments were conducted in Erlenmeyer flasks of 150 mL working volume. The operating conditions of temperature and illumination were the same as those used to prepare the inoculum, although homogeneity was achieved via magnetic stirring (150 rpm). Moreover, pH ranged between 6.5 and 8. For each experiment, a series of ten flasks were prepared in total, arranged as two sets of five (duplicate experiments). All flasks were inoculated with 20% v/v of their total volume, using an inoculum taken from the exponential growth phase (biomass concentration of 75.1 ± 17.5 mg L−1).

2.3. Preparation of Wastewater Mixtures

Four different SCW:PW ratios (50:50%, 60:40%, 70:30% and 85:15%) were examined based on the initial d-COD concentration of 3000 mg L−1. SCW was used in higher proportions because it is generated in larger volumes in the agro-industry and can significantly reduce the turbidity of the final mixtures, a key factor for the growth of the autotrophic microorganisms in the consortium. Moreover, this approach reduces the amount of water required for dilution, ensuring that light penetration in the reactors does not become a limiting factor for growth or for the treatment of higher pollutant concentrations, as previously observed by Patrinou et al. [24] when a single stream of PW was used. It should also be noted that, in most mixtures, the presence of PW helped adjust the initial pH toward neutrality, as SCW is more acidic.

SCW had higher organic and lower inorganic nutrient content than PW, resulting in more balanced nutrient profiles in the final mixtures. Table 1 presents the initial pollutant concentrations achieved for the different mixing ratios. According to Table 1, increasing SCW proportion raised the C:N ratio and induced N and P limitations, conditions known to promote lipid accumulation [22,27].

Table 1.

Initial pollutant and biomass concentrations under the different mixing ratios.

2.4. Analytical Procedures

Aiming to determine growth, lipid production, and pollutant removal rates, sampling was carried out every two days using two flasks for each mixing ratio. The substrate was separated from the microbial biomass by centrifugation at 4200 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant liquid was then filtered through 0.45 μm Whatman filters (Marlborough, MA, USA) and used for chemical analyses. pH measurements were performed using a previously calibrated Hanna (Woonsocket, RI, USA) Benchtop pH meter (HI 2211). Dissolved Chemical Oxygen Demand (d-COD) was measured using the Closed Reflux (5220 D) method [28]. The organic and ammoniacal nitrogen forms were determined according to Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) method [28]. The inorganic nitrogen forms of NO3−-N and NO2−-N, as well as PO43−-P, were measured following the methods of 4500-NO3-B, 4500-NO2-B, and Ascorbic Acid (4500-PE), respectively [28]. Total nitrogen (TN) was calculated as the sum of TKN, NO3−-N and NO2−-N.

Microbial biomass was left to dry at 80 °C for less than 24 h. Biomass concentration, expressed in mg L−1, was determined gravimetrically as total suspended solids [29], while biomass productivity (mg L−1 d−1) and specific growth rate (d−1) were calculated according to Patrinou et al. [30]. Lipids, expressed as % of dry biomass weight (d.w.), were obtained using the protocol of Folch et al. [31], as described in Patrinou et al., [30].

Statistical analyses of variances between nutrient removal rates, biomass, and lipid yields were conducted using one-way ANOVA. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biomass and Lipid Production

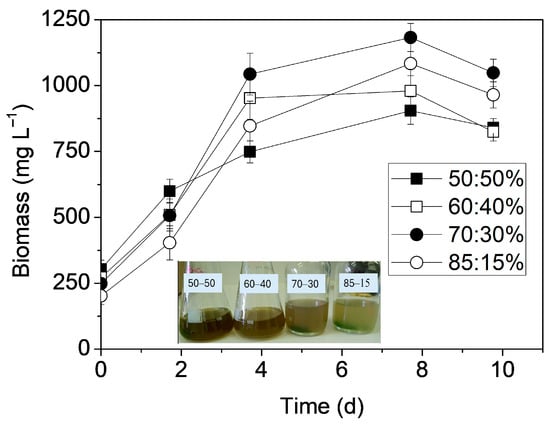

Initially, the effect of different mixing ratios on microbial biomass production was examined (Figure 1). None of the tested ratios had an inhibitory effect on growth, and biomass concentrations ranged from 905.0 to 1185.5 mg L−1. Overall, the maximum biomass productivities ranged between 174.6 and 276.6 mg L−1 d−1, while the corresponding specific growth rates varied from 0.341 d−1 to 0.385 d−1 (Table 2). It was found that the turbidity, which gradually decreased with increasing proportions of SCW, had a decisive role in Leptolyngbya growth. Specifically, at the 50:50% mixing ratio, which exhibited the highest turbidity, the lowest biomass productivity was recorded (174.6 mg L−1 d−1, μ = 0.341 d−1). It is well-known that turbidity influences light availability and therefore the amount of light absorbed by the cells. Moreover, light is a fundamental growth factor directly related to carbon flux, which regulates the rates of photosynthesis and the metabolic pathways [32]. The 60:40% and 70:30% ratios achieved the highest biomass yields (productivity: 276.6 and 268.3 mg L−1 d−1; μ = 0.385 and 0.360 d−1, respectively) (Table 2). Despite having the lowest turbidity, at 85:15%, biomass accumulation was not further improved, possibly due to its slightly acidic pH (~6.5) during the first days of the bioprocess, conditions that are suboptimal for the alkaliphilic Leptolyngbya sp. [33]. Statistical analysis showed that significant differences on growth were not found among all mixing ratios (p = 0.74875); however, differences were observed between the 50:50% and 60:40% (p = 0.025487) and the 50:50% and 70:30% ratios (p = 0.019116).

Figure 1.

Effect of mixing ratios on biomass production.

Table 2.

Effect of mixing ratios on pollutant removal, biomass, and lipid production.

The biomass yields achieved in the present study are consistent with those reported in the literature for Leptolyngbya-based microbial consortia treating wastewater blends. Specifically, Tsolcha et al. [34,35] treated mixed raisin and winery wastewater using both suspended and attached growth cultivation systems. Notably lower biomass productivities were recorded in both the suspended (79.8–87.8 mg L−1 d−1) and the attached systems (113.0–230.7 mg L−1 d−1) compared to the present study. In contrast, during the bioremediation of mixed expired fruit juices, Patrinou et al. [30] reported higher biomass productivities, ranging from 316.3 to 340.0 mg L−1 d−1, employing the same microbial culture as in the present study. When PW and SCW were examined as single streams, biomass productivities of 111.0–198.9 mg L−1 d−1 and 273.2–302.8 mg L−1 d−1 were noted, respectively [22,24]. This confirms that the addition of SCW to PW enhances growth, which can be attributed both to the higher C:N ratios achieved through mixing, and to the highly nutritional composition of milk, which is rich in vitamins, proteins, and trace elements. Similarly, Kashyap et al. [18] investigated a mixture of municipal and dairy wastewaters combined with poultry-litter extracts using a monoculture of Chlorella sp., reporting comparable biomass yields (220–315 mg L−1 d−1) and lipid contents ranging from 25.8 to 32.7%. Lipid contents obtained across all mixing ratios varied between 10.3% and 14.0% d.w. (p = 0.00485).

It was found that both turbidity and C:N ratios influenced intracellular accumulation. The 50:50% mixing ratio exhibited the lowest lipid content (10.3% d.w.), whereas the 70:30% ratio showed the highest value (14.0% d.w.), followed by the 85:15% ratio (11.9% d.w.) This was attributed to the improved light penetration, favoring the proliferation of lipid-producing autotrophic microorganisms of the consortium. Additionally, the 70:30% and 85:15% mixtures exhibited higher C:N ratios, approaching the range reported in the literature (C:N ≈ 45–50) as favorable for enhanced lipid accumulation in Leptolyngbya [30]. The restricted lipid accumulation observed at the 85:15% ratio was attributed to unfavorable pH conditions. This is consistent with Sigh and Kumar [36], who showed that Leptolyngbya foveolarum maximizes lipid production around pH 8, concluding that a higher initial pH promotes metabolic shifts toward lipid biosynthesis. In general, the lipid contents achieved in this study are typical of those reported for Leptolyngbya sp. consortia cultivated in wastewater mixtures (7.0–19.1% d.w.) [30,34,35] or single streams (3.0–15.5% d.w.) [22,24,37].

3.2. Pollutant Removals

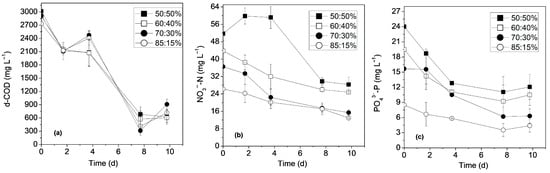

A progressive enhancement in all pollutant removal efficiencies was also observed with increasing SCW proportions. Figure 2 illustrates the effect of the different mixing ratios on pollutant removals. d-COD concentrations were greatly reduced within 8 days of cultivation, exhibiting removal rates that ranged between 77.3 and 89.2% (Figure 2a, Table 2). The highest d-COD removal was recorded at the 70:30% ratio, which also exhibited one of the highest biomass productivities. The slight increase in d-COD concentrations observed on the 10th day of biotreatment was attributed to biomass decline. The achieved d-COD removals are among the highest reported for wastewater blends containing dairy or livestock effluents. Anagnostopoulou et al. [19] optimized the biotreatment of brewery, expired fruit juices, and cheese whey wastewaters for different microalgae strains, achieving d-COD removal efficiencies ranging from 55.0% to 82.0%. Lu et al. [20] reported d-COD removals of 71.1–82.7% during the cultivation of C. vulgaris on dairy processing and slaughterhouse wastewaters. Koutra et al. [17] studied a mixture of different dairy, livestock, and slaughterhouse digestates, employing two microalgae monocultures, and reported d-COD removals of 5.9–53.7%. Similar organic load removals (43.9%) were also observed in the study by López-Sánchez et al. [16] using a mixture of livestock digestates.

Figure 2.

Profile of (a) d-COD; (b) NO3−-N; (c) PO43−-P removal of time under the different mixing ratios.

Total nitrogen (TN) was measured at the first and the last day of cultivation, exhibiting removal rates that ranged between 54.5 and 64.0%. The most favorable conditions for TN assimilation occurred under the 70:30% ratio. In general, NO3−-N noted lower removal efficiencies (41.2–59.5%) than TN, as TN is consumed by both the autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms of the microbial consortium. It should be noted that the same pattern of gradually increasing TN and NO3−-N removals was observed as the clarity of the substrates improved (Figure 2b). This is due to the fact that nitrate assimilation is light-dependent, as it is closely linked to photosynthesis, which provides the necessary energy for the active uptake of inorganic nitrogen sources and their conversion into organic forms [35]. Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences in NO3−-N removal rates among all mixing ratios (p = 0.54782) or among the 50:50% and 60:40% ratios (p = 0.30359). However, differences were observed between the 50:50% and 70:30% ratios (p = 0.02) and between the 50:50% and 85:15% ratios (p = 0.01898). PO43−-P removals ranged between 52.4% and 60.0% (p = 0.40976), while the 70:30% ratio also recorded the highest assimilation rate (Figure 2c). Therefore, taking into consideration that the 70:30% ratio achieved significant biomass production as well as the highest pollutant removal efficiencies and lipid content, it was considered as optimal. The achieved nitrogen and phosphorus bioremediation rates are consistent with those reported in dairy or livestock wastewater blends (TN: 57.8–97.9%, PO43−: 12.0–93.8%) (Table S1). It is worth noting that the study of Kashyap et al. [18], which was the only one to examine a comparable wastewater mixture, reported higher removal efficiencies (TN: 88.1–92.6%, NO3−: 73.1–92.1%). However, given that their blend contained a higher proportion of mixed municipal wastewaters (75%), it is likely that the initial pollutant concentrations were lower.

Considering the substantial biomass, improved lipid yields, and significant pollutant removals achieved, the SCW: PW mixture appears highly promising. The proposed mixed microalgae/cyanobacteria–bacteria consortium can function as a self-sustaining system that offers several advantages. Among these are the elimination of mechanical aeration through photosynthetically produced oxygen, which leads to reduced operational costs [37]. In addition, the presence of bacteria enables the degradation of complex organic compounds into simpler forms, thereby enhancing carbon assimilation by microalgae and its conversion into biomass and metabolic products. It should be noted that the high biomass concentrations achieved were also attributed to these synergistic interactions, enabling its exploitation for energy or biofertilizer production. Finally, the next step in this research will involve scale-up experiments to further investigate the effect of turbidity on the bioprocess, as pilot-scale reactors provide larger surface-to-volume ratios that may influence microbial growth and metabolite production.

4. Conclusions

Mixing different wastewater effluents is a promising strategy for small and decentralized agro-industries, farms, or dairy processing sites to biologically co-treat their wastes. This approach can reduce freshwater demand, improve nutrient profiles without external supplementation, and overcome inhibitory operational constraints, addressing the high costs of microalgae cultivation. Based on this, the present research work aimed to optimize the treatment of a less-studied wastewater blend using a Leptolyngbya-based microbial consortium. Turbidity was found to play a decisive role in biomass production and pollutant removal. At the 70:30% mixing ratio, reduced turbidity enhanced the growth of the lipid-producing autotrophic microorganisms, resulting in increased biomass (268.3 mg L−1 d−1) and lipid accumulation (14.0% d.w.). The higher addition of SCW further promoted lipid content by increasing the C:N ratio while limiting N and P availability. In contrast, the acidic conditions at the 85:15% ratio hindered biomass and lipid production despite lower turbidity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/engproc2025117017/s1, Table S1: Summary of available research employing mixed agro-industrial wastewater streams as cultivation medium for microalgae, presenting growth conditions and yields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.T. and D.V.V.; methodology, V.P. and A.G.T.; validation, V.P. and A.G.T.; formal analysis, V.P.; investigation, V.P.; data curation, V.P., A.G.T. and D.V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P. and A.G.T.; writing—review and editing V.P., D.V.V. and A.G.T.; visualization, V.P. and A.G.T.; supervision, A.G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the dairy industry Papathanasiou A.B.E.E and the poultry farm owners for providing their wastes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mnasser, F.; Martínez-Cartas, M.L.; Sánchez, S. Production of Bioproducts from Wastewater Treatment Using the Microalga Neochloris oleoabundans. Eng. Life Sci. 2025, 25, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, Q.; Fang, F.; Luo, R.; Lu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Huo, S.; Cheng, P.; Liu, J.; Addy, M.; et al. Microalgae-Based Wastewater Treatment for Nutrients Recovery: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.S.A.d.P.; Magalhães, I.B.; Silva, T.A.; Reis, A.J.D.d.; Couto, E.A.d.A.; Calijuri, M.L. Municipal and Industrial Wastewater Blending: Effect of the Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio on Microalgae Productivity and Biocompound Accumulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, M.; Lu, Q.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Addy, M.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R. Enhancement of Lipid Production in Microalgae by Co-utilization of Wastewater and CO2: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganeshkumar, V.; Subashchandrabose, S.R.; Dharmarajan, R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. Use of Mixed Wastewaters from Piggery and Winery for Nutrient Removal and Lipid Production by Chlorella sp. MM3. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ma, H.; Chen, S.; Yu, J.; Xu, W.; Zhu, X.; Gujar, A.; Ji, C.; Xue, J.; Zhang, C.; et al. Mitigating excessive ammonia nitrogen in chicken farm flushing wastewater by mixing strategy for nutrient removal and lipid accumulation in the green alga Chlorella sorokiniana. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.d.S.; Hoffmann, M.T.; Daniel, L.A. Microalgae Cultivation for Municipal and Piggery Wastewater Treatment in Brazil. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100821. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.Y.; Cho, H.U.; Utomo, J.C.; Choi, Y.-N.; Xu, X.; Park, J.M. Biodiesel Production from Scenedesmus bijuga Grown in Anaerobically Digested Food Wastewater Effluent. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bestawy, E. Treatment of Mixed Domestic–Industrial Wastewater Using Cyanobacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 35, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, S.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, S.; Zhu, L. Starch Waste Addition as a Novel Strategy Enhances Pollutant Removal and Biomass Production by Microalgae–Fungi Consortia for Swine Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160127. [Google Scholar]

- You, K.; Ge, F.; Wu, X.; Song, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R.; Zheng, H. Nutrients Recovery from Piggery Wastewater and Starch Wastewater via Microalgae–Bacteria Consortia. Algal Res. 2021, 60, 102551. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, H.; Azimi, Y.; Li, Y.; Mousavi, M.; Cara, F.; Mulcahy, S.; McDonnell, H.; Blanco, A.; Halim, R. Nitrogen and Phosphate Removal from Dairy Processing Side-Streams by Monocultures or Consortium of Microalgae. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 361, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spennati, E.; Casazza, A.A.; Converti, A. Winery Wastewater Treatment by Microalgae to Produce Low-Cost Biomass for Energy Production Purposes. Energies 2020, 13, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foy, J.S. Impact of Algae on Sugar Mill Effluents: Water Treatment and Added Value Assessment. Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Marchetti, J.M.; Wasewar, K.L. Enhancing Nutrient Removal, Biomass Production, and Biochemical Production by Optimizing Microalgae Cultivation in a Mixture of Untreated and Anaerobically Digested Dairy Wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, A.; Silva-Gálvez, A.L.; Zárate-Aranda, J.E.; Yebra-Montes, C.; Orozco-Nunnelly, D.A.; Carrillo-Nieves, D.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Microalgae-Mediated Bioremediation of Cattle, Swine and Poultry Digestates Using Mono- and Mixed-Cultures Coupled with an Optimal Mixture Design. Algal Res. 2022, 64, 102717. [Google Scholar]

- Koutra, E.; Grammatikopoulos, G.; Kornaros, M. Microalgal Post-Treatment of Anaerobically Digested Agro-Industrial Wastes for Nutrient Removal and Lipids Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, S.; Das, N.; Kumar, M.; Mishra, S.; Kumar, S.; Nayak, M. Poultry Litter Extract as Solid Waste Supplement for Enhanced Microalgal Biomass Production and Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 39786509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, C.; Papachristou, I.; Kontogiannopoulos, K.N.; Mourtzinos, I.; Kougias, P.G. Optimization of Microalgae Cultivation in Food Industry Wastewater Using Microplates. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Min, M.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; Zheng, H.; Doan, Y.T.T.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; et al. Mitigating ammonia nitrogen deficiency in dairy wastewaters for algae cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 201, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolcha, O.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Bellou, S.; Aggelis, G.; Katsiapi, M.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Vayenas, D.V. Treatment of second cheese whey effluents using a Choricystis-based system with simultaneous lipid production. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolcha, O.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Antonopoulou, G.; Aggelis, G.; Genitsaris, S.; Moustaka Gouni, M.; Vayenas, D.V. A Leptolyngbya based microbial consortium for agro industrial wastewaters treatment and biodiesel production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 17957–17966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsialou, S.; Tsakona, I.A.; Vayenas, D.V.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G. Biological Treatment of Second Cheese Whey Using Marine Microalgae/Cyanobacteria-Based Systems. Eng. Proc. 2024, 81, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinou, V.; Tsolcha, O.N.; Tatoulis, T.I.; Stefanidou, N.; Dourou, M.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Aggelis, G.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G. Biotreatment of Poultry Waste Coupled with Biodiesel Production Using Suspended and Attached Growth Microalgal-Based Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Oh, H.M.; Jo, B.H.; Lee, S.A.; Shin, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, C.Y. Higher biomass productivity of microalgae in an attached growth system, using wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Hong, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Zhang, H. Attached cultivation of microalgae on rational carriers for swine wastewater treatment and biomass harvesting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Lee, S.M. Effect of the N/P ratio on biomass productivity and nutrient removal from municipal wastewater. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA); American Water Works Association (AWWA); Water Environment Federation (WEF). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association (APHA); American Water Works Association (AWWA); Water Environment Federation (WEF). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 20th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinou, V.; Antonopoulou, G.; Ntaikou, I.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G. Biotreatment of discarded fruit juices and simultaneous lipid production using Leptolyngbya sp. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane-Stanley, G.A. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdury, K.H.; Nahar, N.; Deb, U.K. The Growth Factors Involved in Microalgae Cultivation for Biofuel Production: A Review. Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng. 2020, 9, 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-K.; Ryu, Y.-K.; Kim, T.; Park, A.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Oh, C.; Kang, D.-H.; Choi, W.-Y. Optimization of Industrial-Scale Cultivation Conditions to Enhance the Nutritional Composition of Nontoxic Cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. KIOST-1. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Tsolcha, O.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Aggelis, G.; Genitsaris, S.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Vayenas, D.V. Biotreatment of Raisin and Winery Wastewaters and Simultaneous Biodiesel Production Using a Leptolyngbya-Based Microbial Consortium. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolcha, O.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Aggelis, G.; Genitsaris, S.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Vayenas, D.V. Agroindustrial Wastewater Treatment with Simultaneous Biodiesel Production in Attached Growth Systems Using a Mixed Microbial Culture. Water 2018, 10, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, D. Biomass and Lipid Productivities of Cyanobacteria Leptolyngbya foveolarum HNBGU001. BioEnergy Res. 2021, 14, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.P.; Economou, C.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Vayenas, D.V. Cyanobacteria-Based Biofilm System for Advanced Brewery Wastewater Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.