Abstract

A series of three chalcones with a nitro moiety in ring B (compounds 3a–c) was obtained by following a classic Claisen–Schmidt condensation procedure, which involved hydro-alcoholic conditions at room temperature. The reaction yields are consistently high (>90%), and the spectroscopic data are in close agreement with the anticipated structures. The anti-inflammatory protective effect of 3a–c was evaluated using the carrageenan-induced rat hind paw edema model. Moreover, a Tukey test was conducted to compare the data obtained herein with those for chalcones containing the nitro moiety in Ring A.

1. Introduction

Chalcones (trans-1,3-diaryl-2-propen-1-ones) are biosynthetic products of the shikimate pathway, belonging to the flavonoid family [1]. These compounds are considered precursors to closed-chain flavonoids and isoflavonoids, which have been identified in a variety of plant species, including fruits, vegetables, spices, tea, and soy-based foodstuffs [2]. Furthermore, chalcones are pivotal in the synthesis of numerous biologically essential heterocycles, including indoles, pyrroles, and imidazoles [3]. Chalcones are α,β-unsaturated ketones consisting of two aromatic rings (ring A, which is closer to the carbonyl group, and ring B, which is closer to the unsaturated moiety) [4]. The α,β-unsaturated carbonyl system, which is of high electrophilic character, adopts a nearly planar structure. Chalcones are characterized by the presence of conjugated double bonds and a fully delocalized π–electron system on both benzene rings. This structural feature can give rise to a variety of substituent patterns [5].

A plethora of strategies for synthesizing these systems has been documented, predominantly centered on the formation of carbon–carbon bonds [6]. However, the most common method for synthesizing chalcones is the Claisen–Schmidt condensation, which occurs between aldehydes and acetophenone derivatives under basic conditions. Additionally, reports of acid-catalyzed aldol condensations have appeared [7].

Structural modifications of chalcones have led to a substantial increase in structural diversity. This diversity has been advantageous in the development of novel medicinal agents that exhibit enhanced pharmacological activity and reduced toxicity [8]. These compounds have been reported to show a broad spectrum of biological activities, including antimicrobial, antiviral, antihypertensive, antioxidant, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory properties [9].

In an earlier study, Gomez et al. synthesized three chalcones bearing a nitro moiety in ring A and evaluated their anti-inflammatory activity in a rat model of carrageenan-induced edema. The three structures were evaluated for biological activity at a dose of 200 mg kg−1, revealing a time-dependent anti-inflammatory protective effect following both oral and intraperitoneal administration [10].

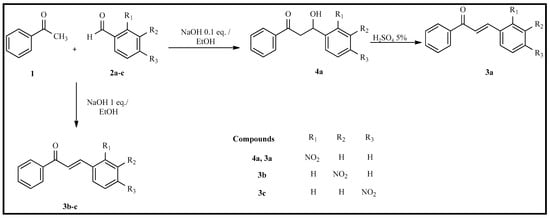

In this report, we outline the synthetic methodologies used to obtain three chalcones bearing a nitro moiety in ring B (Scheme 1). Concurrently, we assess their anti-inflammatory activity in the carrageenan-induced rat hind paw edema model.

Scheme 1.

Claisen–Schmidt condensation reaction with acetophenone and 2-nitrobenzaldehyde, 3-nitrobenzaldehyde, and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

The starting materials for the synthesis of compounds 3a–c were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich in reagent-grade quality. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on pre-coated silica gel F254 plates (Merck, Burlington, MA, USA). The detection process involved quenching fluorescence under UV light (UV lamp, model UV-IIB) and iodine vapor. The melting points were measured using a Fisher–Jones apparatus and left uncorrected. Infrared spectra (IR) were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum One FTMS spectrometer (Shelton, CT, USA). NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury VX-400 NMR spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA, USA) with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard, and chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm).

The synthesis of chalcones 3a–c was accomplished via the Claisen–Schmidt reaction of acetophenone (1) and 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (2a), 3-nitrobenzaldehyde (2b), or 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (2c). The reactions were carried out at room temperature, in ethanol with aqueous NaOH, in accordance with previously reported procedures [11].

In general, the corresponding nitrobenzaldehyde (1 mmol) was initially dissolved in ethanol (3 mL) in a 25 mL round-bottom flask. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C using an ice bath. Subsequently, a solution of 0.1 equivalent of sodium hydroxide (0.05 M, aqueous) and acetophenone (1 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture, which was then left at room temperature for 3 h. After the reaction was complete, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C for 24 h. The solid product obtained was separated by filtration and washed with cold water. A two-solvent recrystallization with dichloromethane and hexane subsequently purified the product.

The procedure above was applied to synthesize 3a, yielding 4a, a β-hydroxyketone. A dehydration process was subsequently employed, in which 1 mmol of 4a was placed in a 5% aqueous sulfuric acid solution under reflux for 30 min. After the reaction was complete, the product was separated by filtration, washed with cold water, and purified by recrystallization using a solvent pair of dichloromethane and hexane.

(E)-3-(2-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylprop-2-en-1-one (3a)

Yield: 90%; m.p. = 115–116 °C; Yellow solid; 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.34 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.72 (m, 2H), 8.01 (m, 2H), 8.04 (dd, J = 5.64, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR spectrum (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 124.8, 127.0, 128.6, 128.6, 129.1, 130.2, 131.1, 133.0, 133.5, 137.2, 140.0, 148.3, 190.2 [12]. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1663,1511,1337.

(E)-3-(3-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylprop-2-en-1-one (3b)

Yield: 94%; m.p. 132–134 °C; White solid; 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.56 (m, 4H), 7.67 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (m, 2H), 8.25 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 2.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR spectrum (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm):122.2, 124.4, 124.5, 128.5, 128.7, 129.9, 133. 2, 134.2, 136.5, 137.4, 141.5, 148.5, 189.5 [12]. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1661, 1529, 1354.

(E)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylprop-2-en-1-one (3c)

Yield: 90%; m.p. 156–158 °C; Yellow solid; 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.53 (dt, J = 7.6, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 15.54 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 15.54 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 2H,), 8.26 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR spectrum (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 124.1, 125.5, 128.5, 128.7, 128.8, 133.3, 137.4, 140.9, 141.4, 148.4, 189.5 [12]. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1659,1515, 1342.

3-hydroxy-3-(2-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylpropan-1-one (4a)

Yield: 90%; m.p. 87–89 °C; White solid; 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 3.22 (dd, J = 17.6, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (dd, J = 17.6, 2 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (OH, 1H), 5.85 (dd, J = 9.6, 2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (m, 3H), 7.58 (m, 1H), 7.68 (m, 1H), 7.95 (m, 4H); 13C NMR spectrum (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 46.4, 65.8, 124.3, 128.1, 128.2, 128.3, 128.6, 133.7, 133.7, 136.1, 138.5, 140.1, 199.7. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1599, 1525, 1346.

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The anti-inflammatory effects of chalcones 3a–c were evaluated using the carrageenan-induced rat hind paw edema model at doses of 25, 50, 100, and 200 mg kg−1, with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as the vehicle.

The experiments were conducted on male Wistar rats weighing 180 to 220 g, housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility maintained at 26 °C and 55% relative humidity, with a 12 h light/dark cycle. All experiments involving rodents and their care were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines on Ethical Standards for Investigation of Experimental Pain in Animals [13] and the Mexican Official Standard for Production, Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999).

The experiment was conducted with 15 groups, each consisting of 6 male Wistar rats. Firstly, the temporal progression of the inflammatory response to carrageenan was examined. Two experimental groups were utilized in this study. The initial measurement of the volume of the right hind paw was taken at a designated time (t = 0). Thereafter, one group administered a single dose of 50 μL of 0.3% carrageenan in isotonic saline solution via intraplanar (i.pl) injection into the right hind paw. The second group was designated the control and received a single dose (50 μL) of isotonic saline solution in the right hind paw. The volume of the right hind paw of each rat was assessed in triplicate every hour for a period of six hours using a plethysmometer (Ugo Basile 7140).

Twelve of the groups were treated with compound 3a, 3b, or 3c by intraperitoneal injection (ip) at doses of 25, 50, 100, and 200 mg Kg−1. The final group received a single oral dose (10 mg kg−1) of meloxicam, which served as a reference drug. After the administrations described above, a single dose i.pl. A Dose of 0.3% carrageenan in isotonic saline solution was injected into the right hind paw of each rat, as previously outlined [14].

The volume of the right hind paw was measured every hour for 6 h using the plethysmometer technique. The maximum anti-inflammatory protective effect (MAPE) was calculated for each animal at each hour throughout the experiment. The MAPE was calculated as a percentage using Equation (1).

MAPE(%) = [(Vcarr − Vtreat)/(Vcarr − Vo)] × [100]

Vcarr denotes the volume of the hind paw of the rat to which carrageenan was administered i.pl. The volume of the rear paw of the rat that received either meloxicam or compounds 3a, 3b, or 3c before carrageenan administration is denoted by Vtreat. Vo is defined as the volume of the rear paw of the rat at t = 0. The MAPE values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. A comparison of the experimental groups was conducted using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a Tukey test. The statistical significance of the results was determined by a p-value cut-off of 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

The three nitrochalcone isomers (3a–c) were obtained in excellent yields, and the β-hydroxyketone compound (4a) was also obtained. The three chalcone compounds (3a–c) were solids and exhibited limited solubility in water but pronounced solubility in DMSO. The infrared (IR) spectra bands were consistent with the functional groups anticipated for the structures. The 1H-NMR coupling constants for the alkene protons were approximately 15 Hz, which indicated that the configuration of the double bond is E in all three compounds, as shown in Table 1. The subsequent assignment of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra corroborated the structures.

Table 1.

Results and reaction conditions for chalcones 3a–c.

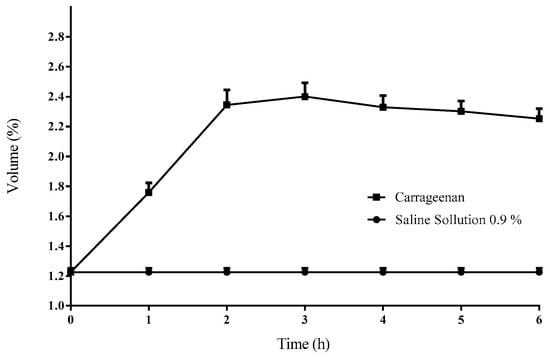

The application of carrageenan (i.pl.) in rats resulted in edema development, increasing from a basal value of 1.2 ± 0.02 mL to a maximum of 2.4 ± 0.09 mL, observed 3 h after carrageenan administration. The control group demonstrated a baseline volume of 1.2 ± 0.02 mL, with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in volume observed during the experiment (Figure 1). A subsequent comparison of the volumes in the carrageenan and control groups revealed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

The temporal progression of the volume of the right rear paw of the rat. A marked increase in volume is evident following the i.pl. application of 0.3% carrageenan. Each data point represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6).

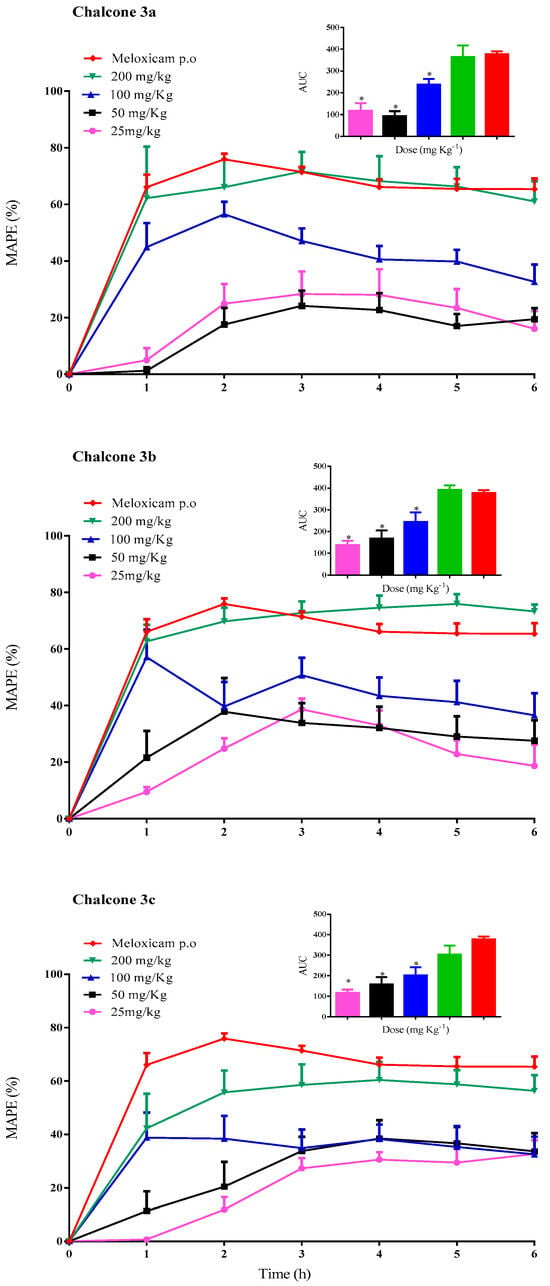

Figure 2 illustrates the time course of the maximum anti-inflammatory protective effect (MAPE) and the area under the curve (AUC) for chalcones 3a, 3b, 3c at doses of 25, 50, 100, and 200 mg kg−1, as well as the reference drug meloxicam (10 mg kg−1, p.o.). The Tukey test applied to the AUC values in each chalcone group revealed that the differences in AUC, and thus in the anti-inflammatory protective effects of each tested chalcone, are statistically significant at p < 0.05. This finding indicates the presence of a dose-response relationship.

Figure 2.

The time course of the MAPE of chalcones 3a, 3b, 3c (25, 50, 100, and 200 mg kg−1, i.p.) and the reference drug meloxicam (10 mg kg−1, p.o.) on the carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats. Each data point represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). Areas under the curve (AUC) for the temporal evolution of the anti-inflammatory protective effect of each chalcone and the reference drug. Each bar represents the average ± standard deviation (n = 6); * statistically significant difference for the reference drug (p < 0.05).

The maximum protective effect (~70%) was observed at a dose of 200 mg kg−1, with the effect being achieved between 1–2 h post-treatment. The highest AUC for compounds 3a–c was also observed at a dose of 200 mg kg−1: 364.8 ± 52.0; 392.3 ± 20.0 and 303.9 ± 43.4, respectively. For the reference group (meloxicam p.o.), the maximum effect (75.9 ± 1.9%) was attained 2 h after administration and remained steady (over 60%) throughout the experiment. The AUC for meloxicam was 377.7 ± 13.1.

A subsequent comparison of the AUC values of chalcone 3a–c at a dose of 200 mg kg−1 with the reference drug (10 mg kg−1) revealed no statistically significant differences at p > 0.05. This finding suggests that, while the anti-inflammatory protective effect remains equivalent in magnitude, the potency may vary. To achieve an anti-inflammatory effect comparable to that of the reference drug, it was necessary to administer a 20-fold dose of the tested compounds.

It is important to note that the anti-inflammatory protective effect was not affected by the position of the nitro group. The Tukey test revealed no significant differences among chalcones with the nitro group in ring A at a dose of 200 mg kg−1 [10]. Furthermore, the position of the nitro moiety in ring B exhibited comparable values to those observed for chalcones with a nitro group moiety in ring A [10]. Conversely, these findings imply that nitrochalcones with the nitro group moiety in ring B exhibit faster absorption (1–2 h) compared to those chalcones with the nitro group moiety in ring A (3–5 h). Consequently, the anti-inflammatory response is achieved more rapidly. This finding suggests that the absorption of nitrochalcones when administered via the intraperitoneal route is influenced by the substitution of the nitro groups on ring A or ring B. These observations warrant further investigations into nitrochalcones.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the synthesis of chalcones 3a–c was accomplished with high efficiency, and the spectroscopic characterizations of these compounds are in excellent agreement with the anticipated structures. The intraperitoneal administration of these chalcones exhibited a dose-dependent anti-inflammatory protective effect. The magnitude of this effect remained unaffected by the position of the nitro group moiety, neither on ring A nor on ring B. However, this anti-inflammatory effect was less potent than that of the reference drug.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.-M.; methodology, E.A.-M., N.R.C., M.Á.V.-R., A.G.-R. and H.A.-M.; validation, A.Y.H.; formal analysis, A.Y.H.; investigation, A.Y.H.; resources, N.R.C. and M.Á.V.-R.; data curation, C.E.L.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.-M., C.E.L.-G. and L.F.R.d.l.F.; writing—review and editing, C.A.-S.; visualization, C.A.-S.; supervision, N.R.C. and M.Á.V.-R.; project administration, L.F.R.d.l.F.; funding acquisition, L.F.R.d.l.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful for financial support from PFI-UJAT (Project 2013-IB-13). E.A.-M. thanks CONACyT for a doctoral Scholarship No. 447166.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Commission on Research Ethics of the División Académica de Ciencias de la Salud (UJAT) approved the present project with registration CIEI-UJAT-0927.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the Unit of Production, Care, and Animal Experimentation (DACS-UJAT) and the Chemistry Center (BUAP). A.Y.H. is grateful for a postdoctoral fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, K.; Yang, S.; Li, S.-M. Naturally Occurring Prenylated Chalcones from Plants: Structural Diversity, Distribution, Activities and Biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 2236–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Ahuja, A.; Sharma, H.; Maheshwari, P. An Overview of Dietary Flavonoids as a Nutraceutical Nanoformulation Approach to Life-Threatening Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 1740–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MT Albuquerque, H.; MM Santos, C.; AS Cavaleiro, J.; MS Silva, A. Chalcones as Versatile Synthons for the Synthesis of 5-and 6-Membered Nitrogen Heterocycles. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 2750–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rifai, N.M.; Mubarak, M.S. A-Substituted Chalcones: A Key Review. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 13224–13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. A Review on Recent Advances and Potential Pharmacological Activities of Versatile Chalchone Molecule. Chem. Int. 2016, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, M.A.; Rizk, S.A.; Fahim, A.M. Synthesis, Reactions and Application of Chalcones: A Systematic Review. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5317–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.B.; Santos, T.A.C.; Silva, A.P.S.; Barreiros, A.L.B.S.; Nardelli, V.B.; Siqueira, I.B.; Dolabella, S.S.; Costa, E.V.; Alves, P.B.; Scher, R. Synthesis of Chalcone Derivatives by Claisen-Schmidt Condensation and in Vitro Analyses of Their Antiprotozoal Activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 38, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, C.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, C.; Zhang, W.; Xing, C.; Miao, Z. Chalcone: A Privileged Structure in Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7762–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, K.; Kaur, R.; Goyal, A.; Awasthi, R. Chalcones: A Review on Synthesis and Pharmacological Activities. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rivera, A.; Aguilar-Mariscal, H.; Romero-Ceronio, N.; Roa-de la Fuente, L.F.; Lobato-García, C.E. Synthesis and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Three Nitro Chalcones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5519–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocconcelli, G.; Diodato, E.; Caricasole, A.; Gaviraghi, G.; Genesio, E.; Ghiron, C.; Magnoni, L.; Pecchioli, E.; Plazzi, P.V.; Terstappen, G.C. Aryl Azoles with Neuroprotective Activity—Parallel Synthesis and Attempts at Target Identification. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 2043–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.Y.; Romero-Ceronio, N.; Lobato-García, C.E.; Herrera-Ruiz, M.; Vázquez-Cancino, R.; Peña-Morán, O.A.; Vilchis-Reyes, M.Á.; Gallegos-García, A.J.; Medrano-Sánchez, E.J.; Hernández-Abreu, O. Position Matters: Effect of Nitro Group in Chalcones on Biological Activities and Correlation via Molecular Docking. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M. Ethical Guidelines for Investigations of Experimental Pain in Conscious Animals. Pain 1983, 16, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Mariscal, H.; Rodriguez-Silverio, J.; Torres-Lopez, J.E.; Flores-Murrieta, F.J. Comparison of the Anti-Hyperalgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Meloxicam in the Rat. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 2006, 49, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).