Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common cancer in childhood; 30–50% of its cases are caused by the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene as a driver oncogene. In this research work, a study of the cytotoxic properties of phthalimido-1,3-thiazole derivatives against the BCR-ABL protein PDB ID: 4WA9 was carried out using a combination of different computational chemistry methods, including a molecular docking/dynamics study and ADM-T evaluation. Six top hits were identified based on their free energy scores, namely 4WA9-L21, 4WA9-L20, 4WA9-L22, 4WA9-L19, 4WA9-L18 and 4WA9-L18, which demonstrated better binding affinity (from −8.36 to −9.29 kcal/mol). Furthermore, MD studies support the molecular docking results and validate the stability of the studied complexes under physiological conditions. These results confirm that the hits selected are verifiable inhibitors of the BCR-ABL protein, implying a good correlation between in silico and in vitro studies. Moreover, in silico ADME-TOX studies were used to predict the pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamics, and toxicological properties of the studied hits. These findings support the future role of phthalimido-1,3-thiazole derivatives against the ALL disease and may help to find a new therapeutic combination of drugs to treat relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia and improve overall survival.

1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common cancer in childhood [1]; 30–50% of its cases are caused by the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene as a driver oncogene [2]. The translocation between the BCR gene region on chromosome 9 and the ABL proto-oncogene 1 (ABL1) gene on chromosome 22 promotes the development of Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia [3]. The ABL1 kinase domain has recently garnered significant attention as a promising molecular target for the development of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) treatment. Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia suffer from drug resistance. Although there are ABL1 kinase inhibitors with remarkable efficacy, this did not prevent the relapse and resistance of treatments for this cancer; this itself even remains an ongoing challenge [4]. To this end, a recently synthesized series of phthalimido-1,3-thiazole derivatives [5] were collected to predict their cytotoxic properties against the ABL1 kinase domain using different computational chemistry methods such as molecular docking, MD simulation, and in silico ADME-TOX evaluation in order to contribute to the development of new (Ph+ ALL) inhibitors.

The proteins’ ability to interact with small molecules plays a crucial role in shaping the dynamics of proteins and therefore impacting their biological functions [6]. Molecular docking was employed for the purpose of predicting the interactions between the ABL1 kinase domain and the studied small molecules. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) were conducted for the most optimal complexes chosen based on their stability. Additionally, the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME-T) properties of novel pharmaceutical compounds have garnered increased interest in drug discovery [7]. In addition, the ADME-T and drug-likeness outcomes demonstrated the favorable pharmacokinetic proprieties and oral bioavailability of these substances. Consequently, the identified compounds are viable candidates for additional scrutiny and enhancement to craft novel lead compounds with enhanced efficacy against Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL.

2. Materials and Methods

The 22 inhibitors used in our work are derivatives of phthalimido-1.3-thiazole. The optimization of the structures was carried out by molecular mechanics with the force field (MM+) implemented in the Hyperchem software [8]. Molecular docking and dynamic simulations of ligands and the crystal structure of human ABL1 kinase domain (PDB ID: 4WA9) were carried out using MOE 2014 (Molecular Operating Environment MOE) [9].

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Docking

A molecular docking study was conducted for the twenty-two phthalimido-1,3-thiazole derivatives with the human ABL1 kinase domain in the 4WA9 protein PDB structure.

The total score energy results of the docked complexes with their distances, types of interactions, key residues, and atoms involved in the compounds and the receptor for the 4WA9 target, are summarized in Table 1, in this study the doxorubicin was taken as a reference.

Table 1.

Docking score and interactions between compounds and active site amino acid residues of target 4WA9.

Doxorubicin has score energy of −7.75 kcal/mol with the formation of two H-acceptor and Pi-H type interactions.

The six best compounds are ordered according to their affinity for the formation of stable complexes with the 4WA9 enzyme as follows: L21 > L20 > L22 > L19 > L17 > L18 with energy scores −9.29, −9.15, −9.02, −8.54, −8.41 and −8.36 (kcal/mol), respectively.

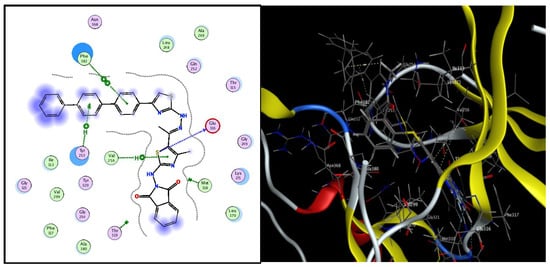

L21 gives the best energy score compared to the other compounds (−9.29 kcal/mol), Figure 1 indicates the 2D and 3D interaction diagrams between the active site of 4WA9 and L21.

Figure 1.

Two dimensional and three-dimensional interactions illustration of 4WA9-active site and L21.

3.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

3.2.1. Ligand-Active Site Interactions

The complexes obtained from molecular docking are used as input in the simulation process for time intervals of 600 Ps each, and the potential energy value was collected every 0.5 ps. The results obtained are represented by curves of the potential energy U (kcal/mol) as a function of the simulation time (Ps) for the 4WA9-ligands complexes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Different interactions result from the MD simulation.

In the 4WA9−L17 complex, the L17 ligand forms a weak bond with the 4WA9 receptor Pi-H type with the GLY 321 residue (3.49 Å).

The 4WA9-L18 complex presents three H-donor bonds: two strong bonds with THR 315 and GLY 250 of lengths 2.76 Å and 2.51 Å; a weak bond with residue GLU 316 of length 3.60 Å. We noted a formation of two other weak H-acceptor bonds with GLY 321 and ASN 322 of length 3.44 Å. 3.23 Å. We also noted the formation of a strong H-acceptor bond with ASN 322 distance (2.68 Å).

The 4WA9−L19 complex has two H-donor bonds with ASP 381 and MET 318 (2.66 Å, 3.38 Å) and two H-acceptor bonds with THR 315 and TYR 253 (2,75 Å and 3,00Å).

The 4WA9−L20 complex represents several interactions: two H-donor bonds with THR 315 (2.82 Å, 3.55 Å) and two strong H-acceptor type bonds with NME 272, TYR 253 (2.73 Å, 2.64Å).

In the 4WA9−L21 complex, we notice the formation of three weak Pi-H type interactions with LEU 301, ASN 322 (4.31 Å 4.00 Å 3.97 Å), and a weak H-donor bond with THR 315 (4.05 Å).

The 4WA9−L22 complex presents two weak Pi-H type interactions with LYS 271 and GLY 321, (3.90 Å, 3.97 Å).

3.2.2. Potential Energy During Simulation Time

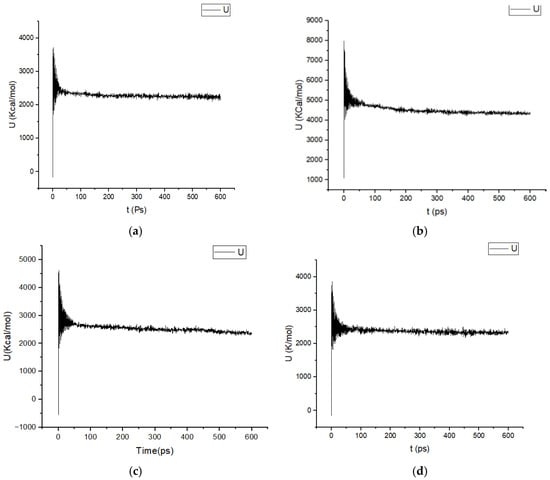

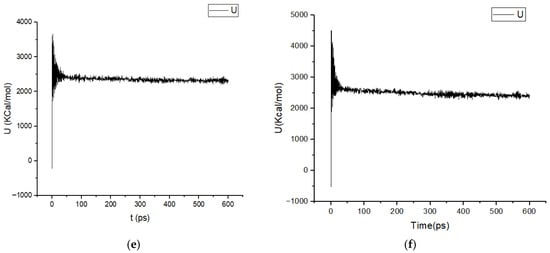

The variation in the potential energy during time of complexes, 4WA9−L17, 4WA9−L18.4WA9−L19, 4WA9−L20, 4WA9−L21, and 4WA9−L22, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Potential energy U (kcal/mol) variations as a function of time of the studied complexes (a) U of 4WA9−L17, (b) U of 4WA9−L18, (c) U of 4WA9−L19, (d) U of 4WA9−L20, (e) U of 4WA9−L121, (f) U of 4WA9−L22.

In all cases, the trajectories exhibit a characteristic two-phase behavior. During the initial stage of the simulations (first 50 to 100 ps), a pronounced fluctuation and rapid decrease in potential energy is observed, reflecting the relaxation of unfavorable steric contacts and the progressive adjustment of atomic interactions following system initialization and energy minimization. This equilibration phase corresponds to solvent reorganization, relaxation of protein–ligand contacts, and redistribution of electrostatic interactions.

After this initial relaxation period, the potential energy profiles converge toward stable plateaus, with only small-amplitude fluctuations around their respective mean values for the remainder of the simulation (600 ps). The absence of long-term drifts or systematic energy trends indicates that all systems reached thermodynamic equilibrium and remained stable throughout the production phase. Such behavior confirms that the applied simulation protocols and force-field parameters were appropriate and that no artificial instabilities or structural disruptions occurred during the simulations.

Notably, although the absolute potential energy values differ among the systems, the overall energy convergence patterns are highly consistent. Systems displaying slightly lower average potential energies (4WA9−L18, 4WA9−L19, 4WA9−L20, 4WA9−L21, and 4WA9−L22) suggest more favorable interactions, which may reflect enhanced stabilization of the corresponding complexes.

Author Contributions

Data collection, software, formal analysis, and the first draft of the manuscript were prepared by I.B. and A.F. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. N.M. contributed to conceptualization, project administration, and supervision. I.D. guaranteed the validation and data curation of this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Axitinib Effectively Inhibits BCR-ABL1 (T315I) with a Distinct Binding Conformation. Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14119 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Peppas, I.; Ford, A.M.; Furness, C.L.; Greaves, M.F. Gut microbiome immaturity and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Leukemia in the Lymphoid Lineage—Similarities and Differences with the Myeloid Lineage and Specific Vulnerabilities—PMC. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7460962/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Cario, G.; Leoni, V.; Conter, V.; Baruchel, A.; Schrappe, M.; Biondi, A. BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood and targeted therapy. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2200–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Dos Santos, F.A.; Ferreira, L.P.d.L.; Pitta, M.G.d.R.; Silva, M.V.d.O.; Cardoso, M.V.d.O.; Pinto, A.F.; Marchand, P.; de Melo Rêgo, M.J.B.; Leite, A.C.L. Synthesis, anticancer activity and mechanism of action of new phthalimido-1,3-thiazole derivatives. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 347, 109597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghiri, K.; Daoud, I.; Melkemi, N.; Mesli, F. Molecular docking/dynamics simulations, MEP analysis, and pharmacokinetics prediction of some withangulatin A derivatives as allosteric glutaminase C inhibitors in breast cancer. Chem. Data Collect. 2023, 46, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettai, M.; Daoud, I.; Mesli, F.; Kenouche, S.; Melkemi, N.; Kherachi, R.; Belkadi, A. Molecular docking/dynamics simulations, MEP analysis, bioisosteric replacement and ADME/T prediction for identification of dual targets inhibitors of Parkinson’s disease with novel scaffold. In Silico Pharmacol. 2023, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HyperChem(TM) Professional, Version 7.51; Hypercube, Inc.: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2019.

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2014. Chemical Computing Group Inc.: Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2014. Available online: https://www.chemcomp.com/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).