Abstract

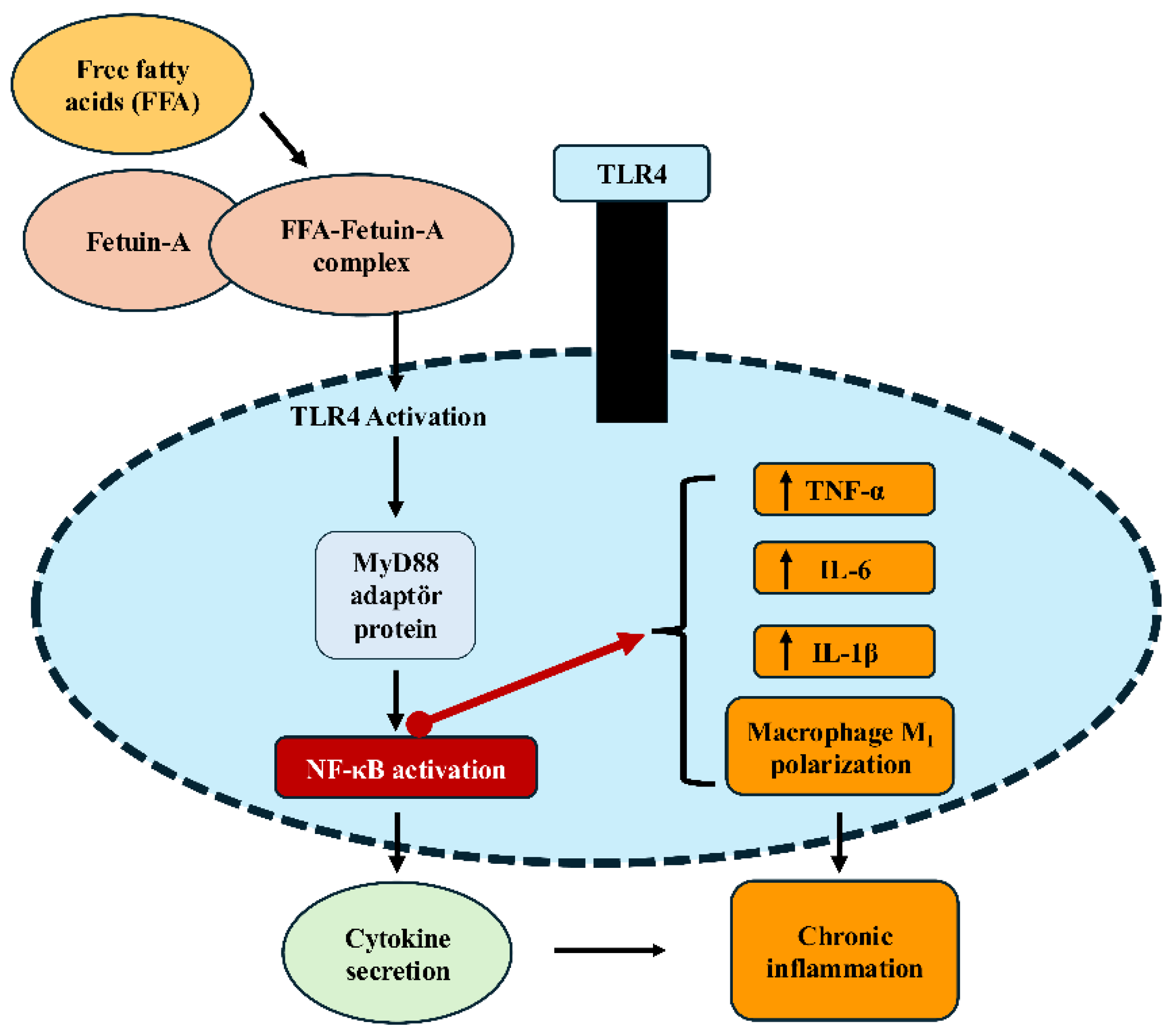

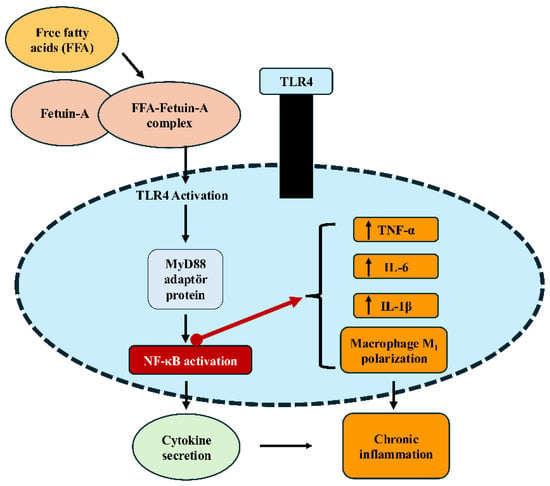

Metabolic inflammation, a state of chronic low-grade inflammation linked to insulin resistance, plays a central role in the development of obesity-related conditions such as type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiovascular disorders. In recent years, two molecules have gained significant prominence in this field, owing to their mechanistic involvement in metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance: fetuin-A (FetA), aliver-derived hepatokine, and chymase, a serine protease released from mast cells. Although they arise from distinct biological sources, they converge on overlapping inflammatory and metabolic pathways. FetA acts as an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), activating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling, driving proinflammatory cytokine release, and impairing insulin signaling. Chymase, on the other hand, generates angiotensin II and activates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), thereby promoting oxidative stress, fibrosis, and secondary metabolic dysfunction. This review proposes a conceptual dual-target framework in which FetA and chymase are considered complementary, rather than independent, mediators of metabolic inflammation. Importantly, this framework is not intended to supersede other established pathways implicated in metabolic inflammation, but rather to provide an integrative perspective that complements existing hepatokine and immune-centered models. Their convergence on NF-κB and TGF-β signaling pathways highlights shared mechanistic nodes within metabolic inflammation. Accordingly, the emphasis of this review is on mechanistic integration within metabolic inflammation, rather than on immediate therapeutic innovation or clinical translation.

1. Introduction

The increase in adipose tissue associated with obesity has been linked to insulin resistance (IR) and low-grade chronic inflammation (metaflammation), which contribute to the development of numerous metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases [1]. In addition to IR and metaflammation, disturbances in the oxidant–antioxidant balance, along with various alterations in intracellular signaling pathways, play significant roles in the development of metabolic diseases [2,3]. Recently several hepatoproteins have been shown to play active roles in these pathophysiological processes [4,5]. Accordingly, this review provides a focused mechanistic synthesis of fetuin-A (FetA) and chymase within the broader context of lipid and glucose metabolism in diabetes, with particular emphasis on their roles in metabolic inflammation.

Fetuin-A is a hepatoprotein synthesized primarily in the liver but also in diverse tissues. Since it has also been shown to be secreted from adipose tissue, it is referred to as a hepatoadipokine [6]. By stimulating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation and inhibiting insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity, it exerts a regulatory effect on both inflammatory and metabolic processes. This dual effect plays an important role particularly in the development of metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance [7,8]. This framework is not intended to imply a direct molecular interaction between FetA and chymase, but rather to highlight their functional convergence at shared inflammatory and fibrotic signaling pathways across distinct metabolic compartments.

Chymase (EC 3.4.21.39) is a serine protease released from mast cells [9,10]. It has been reported to catalyze the synthesis of molecules such as angiotensin II and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which are implicated in inflammation, oxidative stress, tissue fibrosis, and insulin resistance [10,11].

Although FetA and chymase are synthesized in different tissues and differ in their biochemical properties, both can elicit similar pathophysiological processes via inflammatory and metabolic pathways. The aim of this review is to evaluate the shared and distinct roles of FetA and chymase in inflammation and insulin resistance, their clinical associations with metabolic diseases, and their potential therapeutic implications. Accordingly, this article is presented as a focused mechanistic review that aims to propose a conceptual framework for understanding metabolic inflammation, rather than to advance near-term therapeutic innovation.

2. The Role of Chymase in Inflammation and Insulin Resistance

Chymase is a chymotrypsin-like serine protease synthesized in the secretory granules of mast cells [10]. The zymogen form, prochymase, is activated within mast cell granules by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase I (DPPI). Because the intragranular pH of mast cells is low (~5.5), the enzyme remains inactive; however, once the granule contents are released into the interstitial fluid and the pH rises to physiological levels (~7.4), it becomes rapidly activated [9,12]. The optimal pH range for chymase activity is 7 to 9 [13].

Clinical studies investigating chymase activity have predominantly focused on cardiovascular and fibrotic diseases; however, only a limited number have evaluated its association with metabolic disorders. Chymase plays a particularly important role within the local renin–angiotensin system. Urata et al. [14] demonstrated that approximately 80% of angiotensin II synthesis in human cardiac tissue is catalyzed by chymase rather than angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). This finding suggests that chymase functions not merely as a local enzyme but may also play a significant role in systemic metabolic regulation [14]. Chymase generates angiotensin II from angiotensin I through an ACE-independent mechanism. In this process, it also activates key mediators such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and TGF-β, which are implicated in inflammation and fibrosis [10]. Angiotensin II can enhance oxidative stress by stimulating NADPH oxidase; TGF-β can accelerate fibrosis by promoting fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis; and MMP-9 can induce tissue damage by degrading the extracellular matrix. Chymase has been reported to become activated after entering the extracellular matrix, where it exerts its effects within specific tissue microenvironments [15]. In addition, chymase has been shown to activate several proinflammatory molecules, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, endothelins, and neutrophil-activating peptide-2 (NAP-2). Through these actions, it facilitates endothelial dysfunction and immune cell migration, while also accelerating the inflammatory process via mast cell degranulation and kallikrein activation [16]. Through angiotensin II generation and TGF-β activation, chymase may indirectly sensitize tissues to parallel inflammatory pathways, facilitating convergence with TLR4– nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-mediated responses without requiring direct molecular interaction.

Previous animal studies have demonstrated that inhibition of chymase activity with specific inhibitors significantly attenuates hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis, particularly in inflammatory liver diseases such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [17,18,19]. This effect has been specifically associated with reductions in MMP-9 and TGF-β activities [10]. Imai et al. (2014) demonstrated in an acute liver failure model induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/D-galactosamine that hepatic MMP-9 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels, together with chymase activity, were elevated. Following administration of the specific chymase inhibitor TY-51469, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), MMP-9, and TNF-α levels were significantly decreased [20]. These findings suggest that chymase inhibition may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for suppressing hepatic inflammation [11]. Chymase enzymatic activity has also been suggested to be associated with complications of metabolic syndrome (MetS), including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and insulin resistance [21,22,23,24]. In a model developed by feeding SHRSP5/Dmcr rats a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet, hepatic chymase expression and activity were assessed, and treatment with a chymase inhibitor significantly reduced TGF-β and MMP-9 expression, as well as the degree of inflammation and fibrosis [19]. In a recent study, serum chymase levels in obese individuals were found to be positively correlated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Although no significant association was observed with TGF-β1 or MMP-9, a positive relationship between chymase levels and angiotensin II was identified. Individuals with elevated chymase concentrations exhibited higher systolic blood pressure and hs-CRP levels. Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that CRP was independently associated with chymase, suggesting that this protease may serve as a biochemical marker of low-grade inflammation in obesity [25]. Hepatic mast cell-derived chymase may influence hepatocyte injury and hepatic stellate cell activation through paracrine signaling, thereby linking local inflammatory responses to fibrotic remodeling under metabolic stress [11]. Nevertheless, it should be noted that not all experimental studies have reported consistent metabolic effects of chymase modulation, and the magnitude of its impact appears to vary according to disease stage, tissue context, and experimental model, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation.

Chymase is also important in the development of diabetic complications. Chymase-associated increases in angiotensin II have been reported to contribute to podocyte injury. In mouse podocyte cultures, high glucose levels stimulated angiotensin II synthesis, which was suppressed by chymase inhibitors but unaffected by ACE inhibition [26,27]. In a type 1 diabetes model, the chymase inhibitor Suc-Val-Pro-Phe-P(OPh)2 prevented urinary albumin excretion and the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in the kidney [28]. In a hamster type 1 diabetes model, chymase inhibitors such as TEI-F00806 and TEI-E00548 suppressed myocardial fibrosis by reducing cardiac angiotensin II levels and oxidative stress [29]. In type 2 diabetes models, administration of chymase inhibitors also reduced albuminuria and renal angiotensin II levels [30]. In a streptozotocin-induced hamster diabetic model, increased chymase activity in pancreatic islets was shown to cause hyperglycemia, which was suppressed by chymase inhibitors [24]. Moreover, in human chymase transgenic mice, streptozotocin administration significantly increased blood glucose levels, underscoring the role of this enzyme in diabetes development [31]. In studies involving obese and type 2 diabetic patients, increased mast cell infiltration in visceral adipose tissue has been reported to induce chymase protein expression [32,33]. Furthermore, Glajcar et al. (2017) demonstrated that the number of chymase-positive mast cells in the visceral adipose tissue of breast cancer patients was significantly correlated with both metabolic parameters and disease prognosis [34]. Nevertheless, much of evidence linking chymase to insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction is derived from experimental and animal studies, whereas human data remain limited and largely indirect. Importantly, angiotensin II synthesis involves both ACE-dependent and ACE-independent pathways, and the relative contribution of chymase-mediated angiotensin II production appears to vary according to tissue context and disease state rather than acting as a sole determinant of insulin resistance.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that chymase promotes oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis through angiotensin II, and contributes to tissue injury and metabolic dysfunction via interactions with mediators such as MMP-9 and TGF-β. Accordingly, chymase may be considered an important contributor to the progression of metabolic diseases, although this interpretation requires caution given the predominantly preclinical nature of the supporting evidence. Rather than functioning as a systemic metabolic regulator, available data support a role for chymase primarily as a local effector acting within tissue microenvironments, with secondary metabolic consequences.

Randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating chymase inhibition in metabolic disease remain limited. This translational gap may reflect the largely local and paracrine activity of chymase, species-specific differences in mast cell biology, and the absence of metabolic endpoints in existing human studies. While animal models have demonstrated efficacy in NASH, fibrosis, and diabetes, phase II–III clinical studies are required to establish the relevance of these findings in humans.

3. The Relationship of Fetuin-A with Inflammation and Insulin Resistance

FetA, also known as α2-Heremans–Schmid glycoprotein (AHSG), is a hepatokine of 52–60 kDa primarily synthesized by hepatocytes and secreted into circulation [35]. Once known primarily for inhibiting vascular calcification, it is now increasingly studied for its association with obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. It has subsequently been shown to also be secreted from adipocytes [45].

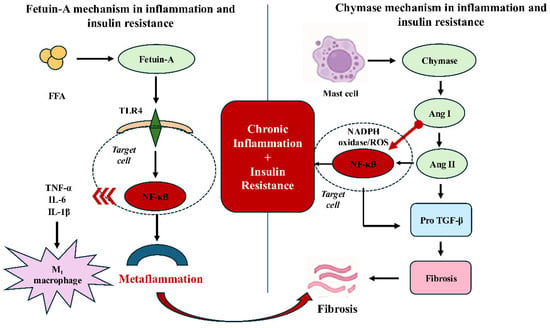

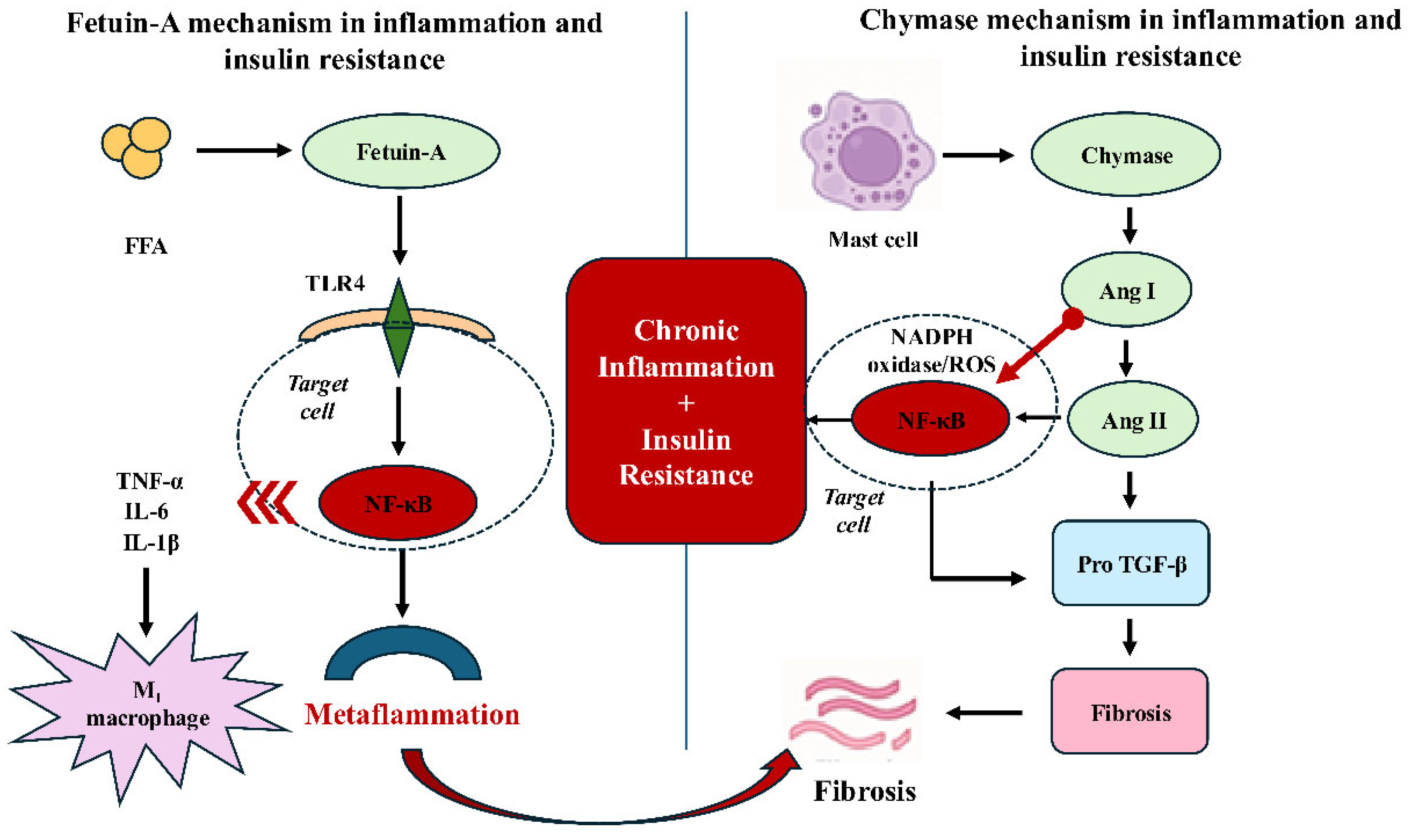

FetA interacts with the insulin receptor, inhibiting tyrosine kinase autophosphorylation and thereby suppressing insulin signaling [46]. Through this mechanism, it reduces peripheral insulin sensitivity and contributes to systemic insulin resistance. At the cellular level, FetA also plays roles beyond metabolism, including immune responses, bone mineralization, acute phase responses, neutrophil degranulation, and thyroid hormone regulation [47]. Due to these diverse functions, it has emerged as an important biomarker of both metabolic dysfunction and metaflammation. FetA forms complexes with FFA, functioning as an endogenous ligand for TLR4, thereby initiating NF-κB activation and enhancing the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [48]. In addition, FetA directly binds to specific regions of TLR4 to further stimulate inflammatory responses and suppresses adiponectin expression, thereby weakening anti-inflammatory mechanisms (Figure 1) [49]. At the tissue level, this proinflammatory signaling may be further upregulated by local factors that enhance oxidative stress and cytokine release, thereby establishing a permissive environment for sustained inflammatory activation. Importantly, the effects of fetuin-A on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and NF-κB–related signaling pathways are highly context-dependent, with conflicting findings across tissues and disease states, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation that accounts for metabolic and inflammatory status and tissue-specific signaling pathways.

Figure 1.

Fetuin-A–TLR4–NF-κB signaling pathway leading to inflammation. Free fatty acids (FFA) form a complex with Fetuin-A, which binds to TLR4 on macrophage/monocyte membranes and triggers downstream signaling. This activation recruits the adaptor protein MyD88, leading to NF-κB activation and subsequent cytokine gene expression. The result is increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), promotion of macrophage M1 polarization, and the development of chronic inflammation. FFA (free fatty acids); TLR4 (Toll-like receptor 4); MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88); NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells); TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha); IL (interleukin). This figure illustrates tissue-specific molecular mechanisms through which fetuin-A contributes to metabolic inflammation. The signaling interactions illustrated are based on current experimental evidence and are presented as proposed mechanisms rather than definitive causal relationships.

In animal models, FetA expression increased by high-fat diet has been shown to be associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress and to play a role in the early stages of hepatic insulin resistance [50]. Seyithanoğlu et al. informed that curcumin and capsaicin administration reduced hepatic FetA expression and lipid accumulation [51]. These findings suggest that natural bioactive compounds may exert protective effects in metabolic dysfunction processes by modulating FetA levels.

In healthy people, serum FetA concentrations are reported to range between 300–600 µg/mL and are not affected by sex, nutritional status, or liver function [8]. Variability in FetA levels has established it as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in numerous clinical conditions, including metabolic syndrome, NAFLD, type 2 diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, and chronic kidney disease [52,53]. However, the establishment of standardized reference ranges is still required for clinical application. Elevated serum FetA levels are positively correlated with type 2 diabetes, visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and NAFLD [54,55,56]. Although reference ranges for circulating fetuin-A have been proposed in population-based studies, these values are subject to considerable variability depending on metabolic status, inflammatory status, and underlying disease context. Large cohort studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that high FetA levels represent an independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes [8,57]. The EPIC-Potsdam study and other prospective analyses have reported that an increase in FetA raises diabetes risk by approximately 23–24% [58,59]. FetA has also been associated with cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction, stroke). Mendelian randomization analyses have shown that genetically determined elevated FetA levels, through variants in the AHSG gene, increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease [60]. These effects, however, appear to be modulated by factors including sex, glycemic status, and inflammatory state. Some studies have found that low FetA levels are associated with cardiovascular mortality, suggesting that this molecule may possess dual biological effects [61]. Collectively, these findings indicate that FetA should be interpreted as a context-sensitive molecule rather than a unidirectional pathogenic factor, with its cardiovascular impact varying according to metabolic and inflammatory status. In individuals with NAFLD, FetA levels are associated with the degree of steatosis and liver enzyme levels [62]. In a previous study, FetA levels in obese individuals were reported to correlate positively with body weight and to decrease following weight loss [49]. This finding further strengthens the association between adipose tissue and inflammation. Tanrikulu-Küçük et al. demonstrated that high FetA and arginase-1 levels in obese subjects correlated with hs-CRP, a marker of inflammation [63]. In adipose tissue, FetA has been shown to promote macrophage infiltration and induce the transition from the M2 to the proinflammatory M1 phenotype, thereby driving metaflammation [64]. FetA related TLR4 activation within adipose tissue may further amplify cytokine secretion and local inflammatory signaling, reinforcing insulin resistance at the tissue level. At the vascular level, both FetA-associated inflammatory signaling and chymase-related angiotensin II generation may contribute to endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling, providing a molecular link between metabolic inflammation and cardiovascular complications.

In conclusion, FetA is a multifunctional protein that occupies a central role in metabolic inflammation through its inhibitory effect on the insulin receptor and its ability to activate inflammatory pathways. While both preclinical and clinical studies highlight the potential of this hepatokine for diagnosing and treating metabolic diseases, significant challenges remain, particularly inter-population variability and the lack of standardized cut-off values. Accordingly, the biological and clinical effects of FetA should be observed carefully, as its effects are highly heterogeneous and strongly influenced by metabolic and inflammatory status.

5. Translational Implications of Chymase and Fetuin-A in Metabolic Inflammation

For clarity, the translational implications discussed below are structured to address biomarker relevance, therapeutic considerations, and exploratory computational approaches, including artificial intelligence-based tools, as distinct but complementary components.

Fetuin-A: FetA is a promising biomarker for the early diagnosis of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Evidence from large-scale cohort studies, including EPIC-Potsdam and Rancho Bernardo, suggests that elevated serum FetA levels are an independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke [8,61]. Moreover, Mendelian randomization-based genetic analyses support these observations, indicating that genetically elevated FetA levels increase the risk of type 2 diabetes by approximately 20–21% and raise the incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) among individuals with diabetes [60]. Conversely, some prospective observational studies have reported that in non-diabetic individuals, higher FetA levels may be associated with lower cardiovascular risk, suggesting that its prognostic value may depend on individual factors [60].

Chymase: In animal models, chymase inhibitors (e.g., TY-51469, Fulacimstat) have been shown to attenuate disease progression in the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH by suppressing inflammation and fibrosis. For instance, in SHRSP5/Dmcr rats fed a high-fat cholesterol (HFC) diet, administration of TY-51469 significantly reduced hepatic levels of angiotensin II, MMP-9, and TGF-β, leading to marked suppression of inflammation and fibrosis [19,67]. In human clinical studies, favorable outcomes have been reported in phase I trials with the next generation chymase inhibitor BAY 1142524 (Fulacimstat), which appear promising for clinical applications [68]. Moreover, given the critical role of chymase in vascular inflammation and fibrosis, the potential utility of these inhibitors in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases is also under investigation [69].

FetA and chymase, though acting through distinct mechanisms, function in complementary ways in pathophysiological processes such as inflammation, metabolism, and fibrosis. In this context, their combined evaluation may support the development of highly sensitive multi-biomarker algorithms for the early diagnosis and prognosis of conditions such as NAFLD, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Looking ahead, the integration of FetA and chymase into artificial intelligence- and machine learning-based clinical decision support systems, together with traditional biomarkers (CRP, ALT/AST), imaging modalities (e.g., elastography), and genetic data, could enable individualized risk profiling. Such integration may pave the way for novel clinical applications, particularly in early diagnosis, personalized therapy, and prognostic evaluation. Accordingly, the combined investigation of FetA and chymase should be regarded as a hypothesis-generating concept that requires comprehensive prospective clinical validation before informing therapeutic decision-making. While these observations emphasize potential translational importance, substantial limitations remain, including limited validation in human metabolic disease, tissue-specific activity, and the absence of large-scale randomized clinical trials.

6. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, direct molecular interactions between FetA and chymase have not been demonstrated, and the proposed framework is based on functional intersection rather than direct coupling. Second, evidence supporting the role of chymase in metabolic disease remains largely preclinical, highlighting the need for well-designed human studies with metabolic outcomes. Notably, the lack of large-scale, well-designed human clinical studies specifically evaluating chymase inhibition in metabolic diseases represents a major limitation that currently limits translational and therapeutic interpretation. Finally, heterogeneity in FetA levels across populations and clinical conditions complicates its universal interpretation as a biomarker. Future research should determine tissue-specific investigations, prospective human studies, and integrative approaches combining mechanistic insights with clinical phenotyping. Importantly, human studies simultaneously targeting both FetA and chymase are currently lacking, representing a key gap for integrated clinical translation.

7. Conclusions

FetA and chymase emerge as two fundamental biomolecules at the intersection of inflammation, insulin resistance, and fibrosis. While FetA is supported by substantial human data as a clinically relevant, context-dependent biomarker, chymase remains a promising but largely experimental factor to metabolic inflammation, with limited validation in human metabolic disease. FetA-driven metaflammation and chymase-mediated fibrogenesis appear to converge on shared signaling pathways such as NF-κB and TGF-β, indicating that their simultaneous modulation may provide synergistic benefits beyond single-molecule interventions. Both molecules modulate inflammation and insulin resistance through distinct mechanisms, yet function in complementary ways within the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases. Consequently, the combined evaluation of chymase and FetA may enhance our understanding of the molecular basis of metabolic inflammation and guide the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

FetA has been established as a clinically applicable biomarker, supported by its ease of measurement, strong epidemiological evidence, and validation through Mendelian randomization. Its well shown associations with type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disease emphasize its diagnostic and prognostic utility, particularly in the setting of personalized healthcare. However, the cardiovascular effects of FetA appear to vary according to factors such as diabetes status, sex, and inflammatory status, highlighting the need for personalized approaches in clinical application.

In contrast, chymase has shown clear pathogenic relevance in experimental models, where its inhibition attenuates both inflammation and fibrosis. However, the limited availability of human data constrains its translation into clinical practice, underscoring the urgent need for advanced-phase clinical trials. While recent progress is encouraging, substantial limitations continue to exist. For chymase, the lack of robust human data on circulating levels and their association with metabolic disorders such as NAFLD, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome continues to limit our understanding, which remains largely dependent on in vitro and animal studies.

At the molecular level, unresolved questions persist: the indirect influence of chymase on TLR4 signaling, its role in macrophage polarization, and its effects on intercellular inflammatory communication remain unclear. Likewise, post-translational modifications of FetA, including glycosylation and phosphorylation, have been only superficially investigated, despite their potential to shape its biological activity and structural diversity.

Looking ahead, future priorities include multicenter prospective studies evaluating both serum and tissue levels of these molecules, together with systematic mechanistic investigations to clarify their roles in macrophage biology, TGF-β signaling, and insulin pathways. Early-phase clinical trials of chymase inhibitors such as TY-51469 and Fulacimstat are warranted.

Beyond conventional approaches, the integration of FetA and chymase into AI- and machine learning–based biomarker algorithms, together with classical biochemical markers (CRP, ALT/AST), imaging modalities such as elastography, and genetic data, may facilitate individualized risk stratification and precision therapeutic strategies. An important contribution of this review is the proposal of a dual-target approach that redefines FetA and chymase as complementary drivers, rather than independent actors, in metabolic inflammation. This systems-oriented approach integrates disease mechanisms and supports translational innovations such as multi-biomarker algorithms, AI-based decision tools, and combination therapies, with the potential to improve early diagnosis, prognosis, and management of metabolic disorders. At present, however, artificial intelligence– and machine learning based applications in this setting should be regarded as exploratory and hypothesis generating approaches for integrating complex biomarker datasets, rather than as validated clinical decision-making strategies. Importantly, while the role of FetA in metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance is supported by substantial human evidence, the role of chymase remains a developing concept primarily informed by experimental and preclinical studies, underscoring the need for further clinical validation.

Author Contributions

Y.Ö.-İ. and H.K. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Caputo, T.; Gilardi, F.; Desvergne, B. From chronic overnutrition to metaflammation and insulin resistance: Adipose tissue and liver contributions. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3061–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.J.; Bao, W.Q.; Zhang, C.F.; Jiang, M.L.; Liang, T.L.; Ma, G.Y.; Liu, L.; Pan, H.D.; Li, R.Z. Immunometabolism and oxidative stress: Roles and therapeutic strategies in cancer and aging. npj Aging 2025, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Schick, F.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Häring, H.U.; White, M.F. The role of hepatokines in NAFLD. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen-Cody, S.O.; Potthoff, M.J. Hepatokines and metabolism: Deciphering communication from the liver. Mol. Metab. 2021, 44, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Emoto, M.; Inaba, M. Fetuin-A: A multifunctional protein. Recent Pat. Endocr. Metab. Immune Drug Discov. 2011, 5, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Hennige, A.M.; Staiger, H.; Machann, J.; Schick, F.; Krober, S.M.; Kröber, F.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U. Alpha2 Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is associated with insulin resistance and fat accumulation in the liver in humans. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Fritsche, A.; Weikert, C.; Boeing, H.; Joost, H.G.; Häring, H.U.; Schulze, M.B. Plasma fetuin-A levels and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2762–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, M.B.; Nemeth, E.F.; Scarpa, A. Measurement of the internal pH of mast cell granules using microvolumetric fluorescence and isotopic techniques. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987, 254, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Miyazaki, M. Multiple mechanisms for the action of chymase inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 118, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D. Chymase as a possible therapeutic target for amelioration of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEuen, A.R.; Sharma, B.; Walls, A.F. Regulation of the activity of human chymase during storage and release from mast cells: The contributions of inorganic cations, pH, heparin and histamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1267, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunishi, H.; Miyazaki, M.; Toda, N. Evidence for a putatively new angiotensin II-generating enzyme in the vascular wall. J. Hypertens. 1984, 2, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urata, H.; Healy, B.; Stewart, R.W.; Bumpus, F.M.; Husain, A. Angiotensin II-forming pathways in normal and failing human hearts. Circ. Res. 1990, 66, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiakshin, D.; Buchwalow, I.; Tiemann, M. Mast cell chymase: Morphofunctional characteristics. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 152, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Italia, L.J.; Collawn, J.F.; Ferrario, C.M. Multifunctional role of chymase in acute and chronic cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, K.; Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Yamamoto, H.; Komeda, K.; Hayashi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Tanigawa, N.; Miyazaki, M. Chymase inhibitor prevents the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in hamsters fed a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Hepatol. Res. 2010, 40, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masubuchi, S.; Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Tashiro, K.; Komeda, K.; Li, Z.L.; Otsuki, Y.; Okamura, H.; Hayashi, M.; Uchiyama, K. Chymase inhibitor ameliorates hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in established non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in hamsters fed a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Hepatol. Res. 2013, 43, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaoka, Y.; Jin, D.; Tashiro, K.; Komeda, K.; Masubuchi, S.; Hirokawa, F.; Hayashi, M.; Takai, S.; Uchiyama, K. Chymase inhibitor prevents the development and progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats fed a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 134, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Komeda, K.; Tashiro, K.; Li, Z.L.; Otsuki, Y.; Okamura, H.; Hayashi, M.; Uchiyama, K. Chymase inhibition attenuates lipopolysaccha-ride/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver failure in hamsters. Pharmacology 2014, 93, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Yamamoto, H.; Yamanishi, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Higashino, H.; Yamanishi, H.; Okamura, H. Chymase inhibition improves vascular dysfunction and survival in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D. Improvement of cardiovascular remodelling by chymase inhibitor. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2016, 43, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, M.; Penttila, A.; Kovanen, P.T. Accumulation of activated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Circulation 1994, 90, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D.; Ohzu, M.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, M. Chymase inhibition provides pancreatic islet protection in hamsters with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 110, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Topparmak, E.; Tanrikulu-Kucuk, S.; Kocak, H.; Oner-Iyidogan, Y. Serum chymase levels in obese individuals: The relationship with inflammation and hypertension. Turk. J. Biochem. 2020, 45, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.R.; Chen, W.Y.; Truong, L.D.; Lan, H.Y. Chymase is upregulated in diabetic nephropathy: Implications for an alternative pathway of angiotensin II-mediated diabetic renal and vascular disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durvasula, R.V.; Shankland, S.J. Activation of a local renin-angiotensin system in podocytes by glucose. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2008, 294, F830–F839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, W.; Bai, J.; Nie, X.; Wang, W. Chymase inhibition protects diabetic rats from renal lesions. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maeda, Y.; Inoguchi, T.; Takei, R.; Hendarto, H.; Ide, M.; Inoue, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Urata, H.; Nishiyama, A.; Takayanagi, R. Chymase inhibition prevents myocardial fibrosis through the attenuation of NOX4-associated oxidative stress in diabetic hamsters. J. Diabetes Investig. 2012, 3, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bivona, B.J.; Takai, S.; Seth, D.M.; Satou, R.; Harrison-Bernard, L.M. Chymase inhibition retards albuminuria in type 2 diabetes. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, K.; Sherajee, S.J.; Fan, Y.Y.; Fujisawa, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsuura, J.; Hase, N.; Urata, H.; Nakano, D.; Hitomi, H.; et al. Blood glucose level and survival in streptozoto-cin-treated human chymase transgenic mice. Chin. J. Physiol. 2011, 54, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divoux, A.; Moutel, S.; Poitou, C.; Lacasa, D.; Veyrie, N.; Aissat, A.; Arock, M.; Guerre-Millo, M.; Clément, K. Mast cells in human adipose tissue: Link with morbid obesity, inflammatory status, and diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E1677–E1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, N.; Kezerle, Y.; Gepner, Y.; Haim, Y.; Pecht, T.; Gazit, R.; Polischuk, V.; Liberty, I.F.; Kirshtein, B.; Shaco-Levy, R.; et al. Higher mast cell accumulation in human adipose tissues defines clinically favorable obesity sub-phenotypes. Cells 2020, 9, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glajcar, A.; Szpor, J.; Pacek, A.; Tyrak, K.E.; Chan, F.; Streb, J.; Hodorowicz-Zaniewska, D.; Okoń, K. The relationship between breast cancer molecular subtypes and mast cell populations in the tumor microenvironment. Virchows Arch. 2017, 470, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, C.; Heiss, A.; Schwarz, A.; Westenfeld, R.; Ketteler, M.; Floege, J.; Muller-Esterl, W.; Schinke, T.; Jahnen-Dechent, W. The serum protein alpha 2-Heremans-Schmid glyco-protein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennige, A.M.; Staiger, H.; Wicke, C.; Machicao, F.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U.; Stefan, N. Fetuin-A induces cytokine expression and sup-presses adiponectin production. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundranda, M.N.; Henderson, M.; Carter, K.J.; Gorden, L.; Binhazim, A.; Ray, S.; Baptiste, T.; Shokrani, M.; Leite-Browning, M.L.; Jahnen-Dechent, W.; et al. The serum glycoprotein fetuin-A promotes Lewis lung carcinoma tumorigenesis via adhesive-dependent and adhesive-independent mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Chatterjee, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Das, S.; Majumdar, S.S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhattarcharya, S.l. Impairment of energy sensors, SIRT1 and AMPK, in lipid-induced inflamed adipocytes is regulated by fetuin-A. Cell Signal. 2018, 42, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Babler, A.; Moshkova, I.; Gremse, F.; Kiessling, F.; Kusebauch, U.; Nelea, V.; Kramann, R.; Moritz, R.L.; McKee, M.D.; et al. Lumenal calcification and microvasculopathy in fetuin-A-deficient mice lead to multiple organ morbidity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.X.; Li, C.Y.; Deng, Y.L. Patients with nephrolithiasis had lower fetuin-A protein level in urine and renal tissue. Urolithiasis 2014, 42, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancio, J.; Barros, A.S.; Conceicao, G.; Pessoa-Amorim, G.; Santa, C.; Bartosch, C.; Ferreira, W.; Carvalho, M.; Ferreira, N.; Vouga, L.; et al. Epicardial adipose tissue volume and annexin A2/fetuin-A signalling are linked to coronary calcification in advanced coronary artery disease: Computed tomography and proteomic biomarkers from the EPICHEART study. Atherosclerosis 2020, 292, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Xu, M.; Bi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Serum fetuin-A associates with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance in Chinese adults. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.T.; Rakhade, S.; Zhou, X.; Parker, G.C.; Coscina, D.V.; Grunberger, G. Fetuin-null mice are protected against obesity and insulin resistance associated with aging. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 350, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.; Koumangoye, R.; Thompson, P.; Sakwe, A.M.; Patel, T.; Pratap, S.; Ochieng, J. Fetuin-A triggers the secretion of a novel set of exosomes in detached tumor cells that mediate their adhesion and spreading. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 3458–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jialal, I.; Pahwa, R. Fetuin-A is also an adipokine. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.T.; Singh, G.P.; Ranalletta, M.; Cintron, V.J.; Qiang, X.; Goustin, A.S.; Jen, K.L.C.; Charron, M.J.; Jahnen-Dechent, W.; Grunberger, G. Improved insulin sensitivity and resistance to weight gain in mice null for the Ahsg gene. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2450–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icer, M.A.; Yıldıran, H. Effects of fetuin-A with diverse functions and multiple mechanisms on human health. Clin. Biochem. 2021, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Dasgupta, S.; Kundu, R.; Maitra, S.; Das, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Ray, S.; Majumdar, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S. Fetuin-A acts as an endogenous ligand of TLR4 to promote lipid-induced insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourebaba, L.; Marycz, K. Pathophysiological implication of fetuin-A glycoprotein in the development of metabolic disorders: A concise review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meex, R.C.R.; Hoy, A.J.; Morris, A.; Brown, R.D.; Lo, J.C.Y.; Burke, M.; Goode, R.J.A.; Kingwell, B.A.; Kraakman, M.J.; Febbraio, M.A.; et al. Fetuin B is a secreted hepatocyte factor linking steatosis to impaired glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyithanoglu, M.; Oner-Iyidogan, Y.; Dogru-Abbasoglu, S.; Tanrikulu-Kucuk, S.; Kocak, H.; Beyhan-Ozdas, S.; Kocak-Toker, N. The effect of dietary curcumin and capsaicin on hepatic fetuin-A expression and fat accumulation in rats fed on a high-fat diet. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 122, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Roth, C.L. Fetuin-A and its relation to metabolic syndrome and fatty liver disease in obese children before and after weight loss. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 4479–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.B.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, W.K.; Suh, J.S.; Cho, K.S.; Suh, B.K.; Jung, M.H. Clinical significance of the fetuin-A-to-adiponectin ratio in obese children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus. Children 2021, 8, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, H.T.; Wu, J.S.; Lu, F.H.; Chang, C.J. Serum fetuin-A concentrations are elevated in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Clin. Endocrinol. 2011, 75, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ix, J.H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Brandenburg, V.M.; Ali, S.; Ketteler, M.; Whooley, M.A. Association between human fetuin-A and the metabolic syndrome. Circulation 2006, 113, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroner, S.A.; St-Jules, D.E.; Mukamal, K.J.; Katz, R.; Shlipak, M.G.; Criqui, M.H.; Kestenbaum, B.; Siscovick, D.S.; de Boer, J.H.; Jenny, N.S.; et al. Fetuin-A, glycemic status, and risk of cardiovas-cular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2016, 248, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, V.Y.; Cao, B.; Cai, C.; Cheng, K.K.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Fetuin-A levels and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, J.M.; Stingl, H.; Höllerl, F.; Schernthaner, G.H.; Kopp, H.P.; Schernthaner, G. Elevated fetuin-A concentrations in morbid obesity decrease after dramatic weight loss. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 4877–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroner, S.A.; Mukamal, K.J.; St-Jules, D.E.; Budoff, M.J.; Katz, R.; Criqui, M.H.; Allison, M.A.; de Boer, I.H.; Siscovick, D.S.; Ix, J.H.; et al. Fetuin-A and risk of diabetes independent of liver fat content: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ali, L.; van de Vegte, Y.J.; Abdullah Said, M.; Groot, H.E.; Hendriks, T.; Yeung, M.W.; Lipsic, E.; van der Harst, P. Fetuin-A and its genetic association with cardiometabolic disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikert, C.; Stefan, N.; Schulze, M.B.; Pischon, T.; Berger, K.; Joost, H.G.; Häring, H.U.; Boeing, H.; Fritsche, A. Plasma fetuin-A levels and the risk of myocardial in-farction and ischemic stroke. Circulation 2008, 118, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Yonal, O.; Kurt, R.; Ari, F.; Oral, A.Y.; Celikel, C.A.; Korkmaz, S.; Ulukaya, E.; Ozdogan, O.; Imeryuz, N.; et al. Serum fetuin-A/alpha2-HS-glycoprotein levels in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Relation with liver fibrosis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 47, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanrikulu-Kucuk, S.; Kocak, H.; Oner-Iyidogan, Y.; Seyithanoglu, M.; Topparmak, E.; Kayan-Tapan, T. Serum fetuin-A and arginase-1 in human obesity model: Is there any interaction between inflammatory status and arginine metabolism? Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2015, 75, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, P.; Seal, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kundu, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Ray, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Majumdar, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S. Adipocyte fetuin-A contributes to macrophage migration into adipose tissue and polarization of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 28324–28330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oner-Iyidogan, Y.; Seyithanoglu, M.; Tanrikulu-Kucuk, S.; Kocak, H.; Beyhan-Ozdas, S.; Kocak-Toker, N. The effect of dietary curcumin on hepatic chymase activity and serum fetuin-A levels in rats fed a high-fat diet. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Jin, D. Chymase inhibitor as a novel therapeutic agent for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düngen, H.D.; Kober, L.; Nodari, S.; Schou, M.; Otto, C.; Becka, M.; Kanefendt, F.; Winkelmann, B.R.; Gislason, G.; Richard, F.; et al. Safety and tolerability of the chymase inhibitor fulacimstat in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: Results of the CHIARA MIA 1 trial. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2019, 8, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyamada, S.; Bianchi, C.; Takai, S.; Chu, L.M.; Sellke, F.W. Chymase inhibition reduces infarction, matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation, and attenuates inflammation and fibrosis after acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 339, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.