Abstract

Microvascular complications of diabetes include retinopathy (DR), diabetic kidney disease (DKD), and neuropathy (DN), which play a crucial role in diabetes management, as they significantly impair the functionality of the patient and remain major causes of morbidity despite advances in glycaemic control. The aim of this review was to summarize multi-omics findings in DR, DKD, and DN. Multi-omics studies consist of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic research. These studies provided comprehensive insights into the complex mechanisms underlying microvascular complications of diabetes, such as inflammation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis in the retina, kidneys, and nervous system. They also enabled the search for emerging diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers. Moreover, changes in microRNA levels were found to differentiate patients with non-proliferative and proliferative DR. In addition, different proteins and metabolites concentrations were noticed in diabetes macular oedema and tractional retinal detachment—serious complications of DR. Specific molecular signatures, such as miR-146a and miR-27 dysregulation, changes in levels of HLA-DRA, AGER, and HSPA1A proteins, and alterations in tyrosine, alanine, 2,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid, ribonic acid, myoinositol, ribitol, 3,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid, valine, glycine, and 2-hydroxyisovaleric acid, were found to be characteristic for all microvascular complications of diabetes. In the future, more studies in multi-omics are expected to help improve precision medicine approaches to treating diabetes, allowing for personalized prediction, prevention, and treatment of microvascular complications.

1. Introduction

Multi-omics research gives us an unprecedented opportunity to discover physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms in a way that was previously unavailable. Omics studies consist of genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [1,2]. Genomics examines genes, their specific variants, and roles in biological processes using techniques derived from next-generation sequencing (NGS). Transcriptomics describes changes in the expressions of different types of RNA, reflecting the modulation of translation leading to different protein synthesis in various cellular processes. In the analysis of transcriptomics, microarrays are used [1,3]. Proteomics measures protein profiles, providing insight into cellular functions. Meanwhile, metabolomics expands the knowledge of metabolites within cells and biofluids as signalling molecules in various pathways. In both proteomics and metabolomics studies, mass spectrometry is applied as a major technology [1,4]. Epigenomics is focused on processes affecting gene expression, e.g., DNA methylation and histone modification, which could be accessed using microarrays and chromatin immunoprecipitation, followed by sequencing [1]. Merging the above-mentioned techniques created the term “multi-omics studies”, which have been conducted extensively in recent years and have provided even more detailed analysis [1]. Multi-omics studies play an important role in various branches of medicine, such as oncology, cardiology, and metabolic diseases. They allow for a better understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms, finding predictive and prognostic markers, risk assessment and stratification, and evaluating treatment efficacy [2,4,5,6,7]. Therefore, many researchers have turned their attention toward diabetes and its complications. The prevalence of diabetes was estimated to reach 463 million people worldwide in 2019. About 90% of patients are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [8]. Complications of diabetes are commonly observed in both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and T2D, as well as in monogenic diabetes, which is responsible for up to 6.5% of diabetes in the paediatric population. The most common types of monogenic diabetes are maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) with pathogenic variants in the GCK gene (GCK-MODY) and the HNF1A gene (HNF1A-MODY) [9,10,11]. Multi-omics studies have enabled the identification of diabetes susceptibility, the prediction of the onset of diabetes, and the assessment of disease progression and partial remission in T1D, have created potential biomarkers of acute complications and therapeutic responses, and have set a cornerstone for novel drug discoveries [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

2. Microvascular Complications of Diabetes

Long-term hyperglycaemia leads to microvascular complications, such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), nephropathy, especially diabetic kidney disease (DKD), and diabetic neuropathy (DN) [9,20,21]. Monitoring for these complications plays an integral role in diabetes management, as their development significantly impairs the functionality of the patient.

DR is caused by neurodegeneration and microvascular damages in the retina, causing neovascularization and retinal haemorrhages, which lead to subsequent loss of vision [9,21,22]. Damages in the retinal nerves could be present even before vascular changes. Apoptosis of photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells prompts thickening of the retinal nerve fibre layer, which could be diagnosed using the Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) method [23,24]. The occurrence of DR is correlated with the duration of diabetes and its management. One of the known risk factors of DR is obesity [21,22,25]. The prevalence of DR in T1D adolescents with diabetes duration over 5 years was estimated to be 20%, and in T1D children, 6% [9]. The vast majority of adults with T1D and diabetes duration over 20 years will develop DR, while more than 60% of adults with T2D and diabetes duration over 20 years will have DR [21].

DN affects both peripheral and autonomic nerves, causing pain, walking difficulties, and cardiovascular risk increment [20]. DN is asymptomatic; however, once symptoms are present, the deficits cannot be reversed. Diagnosis at early stages is crucial to prevent the development and progression of DN [26]. Incidence of DN differs in the literature due to inconsistent diagnostic parameters. The prevalence of DN in the paediatric population with T1D was estimated to be around 3%, while in T1D patients 15–29 years old, it was reported to be 19% [9]. The prevalence of DN in T2D patients with diabetes duration of around 4 years is 7.7%, and about 30% of all T2D patients will develop diabetic peripheral neuropathy [22]. Moreover, some patients with T2D might have DN when the diagnosis of T2D is made. In contrast, in patients with T1D, DN typically appears 10 years after the diagnosis. Interestingly, some sensory impairments or neuropathic pain may be present in patients in a pre-diabetic state [27].

DKD is the deterioration of renal function due to hyperglycaemia. Diagnosis of DKD is based on microalbuminuria (in early stages) and renal biopsy to assess its severity. About 20–40% of all adult patients with diabetes will develop DKD, which may progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [28,29,30]. Patients with T1D and a diabetes duration of about 4–8 years will have microalbuminuria in 4–9% cases [28]. The prevalence of DKD in T2D patients with a diabetes duration of around 4 years was estimated to be 5% [22], while albuminuria was present in 22% paediatric patients with T2D. Risk factors of DKD development include diabetes duration, hypertension, and obesity. DKD is known to increase cardiovascular risk [22].

Despite the development of new technologies improving proper glycaemia management, patients with diabetes are still at risk of developing microvascular complications. Multi-omics studies provide us with an unprecedented opportunity to investigate the pathological processes behind each mentioned complication and look for prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers of those conditions.

3. Multi-Omics in Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

Hyperglycaemia induces oxidative stress, inflammation, increased concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and vascular dysfunction (which leads to progressive damages in the eye, including apoptosis of endothelial cells, leakages from retinal capillaries with subsequent retinal haemorrhages). These are accompanied by fibrosis, especially in microglia, which leads to loss of retinal ganglion cells, astrocytes, and photoreceptors, culminating in retinal detachments and loss of vision [21,22,24,25].

3.1. Genomics in DR

The genetic locus of ARHGAP22 encodes a protein associated with angiogenesis, GRB2 is associated with VEGF activation, and NOX4 is associated with VEGF regulation, angiogenesis, and oxidative stress [31,32].

3.2. Epigenomics in DR

Methylation of SUOX and CHEK1 genes was found to have a protective effect in DR development through the modulation of oxidative stress [33]. Hypermethylation of the MTHFR gene promoter was related to the occurrence of DR. Greater risk of DR development was linked with hypermethylation of the promoter of gene miR-9-3. Downregulation of PLTP, through DNMT3B overexpression, was found to disturb the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells in retinal vessels [34,35,36,37].

3.3. Transcriptomics in DR

MicroRNA (miRNA)-150 was found to suppress inflammation, pathological angiogenesis, and apoptosis. Downregulation of miRNA-150 was linked with DR development [38]. Studies on miRNA in the vitreous humour found downregulation of miR-204-5p and upregulation of miR-486-5p as promising diagnostic markers of DR. The miR-486-5p was suggested to play a role in angiogenesis, and miR-204-5p might have a protective function in endoplasmic reticulum stress [39]. Furthermore, other researchers have identified an increase in miRNA-152 and a decrease in miRNA-93 in serum as predictive biomarkers of DR [40]. In addition, a panel of three miRNAs (hsa-let-7a-5p, hsa-miR-novel-chr5_15976, and hsa-miR-28-3p) was proposed to predict the development of DR in T2D patients [34].

3.4. Proteomics in DR

About 87 proteins in various biofluids (blood, aqueous, and vitreous humour) were linked with retinal inflammation. However, only three proteins (i.e., α-1-acid glycoprotein, apolipoprotein A-I, and apolipoprotein A-IV) were altered in these three fluids [41].

3.5. Metabolomics in DR

Metabolomic studies provided insight into amino acid and energy metabolism changes in patient with DR, identifying potential biomarkers: l-glutamine, l-lactic acid, pyruvic acid, acetic acid, l-glutamic acid, d-glucose, l-alanine, l-threonine, citrulline, l-lysine, and succinic acid. Importantly, upregulation or downregulation of two metabolites (l-glutamine and citrulline) was present in three biofluids (plasma, aqueous, and vitreous humour) [42]. In another study, dysregulation of methylglutaryl carnitine, tryptophan, glucose-6-phosphate, and N-methyl-glutamate levels in plasma was observed in T2D patients with DR [43]. Meanwhile, changes in cis-aconitic acid and ophthalmic acid levels in the aqueous humour were described as biomarkers of DR [44].

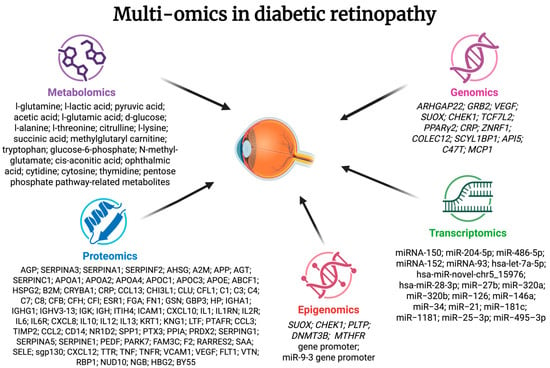

Additionally, Chen et al. summarized the information on multi-omics biomarkers, mentioning 5 more proteins, 3 more amino acids and pentose phosphate pathway-related metabolites, 11 miRNAs, and 12 genetic variants [25]. Alterations found in multi-omics studies in DR were connected with various processes, including modulation of VEGF, inflammation, neovascularisation, apoptosis, energy metabolism, and oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Changes found in multi-omics studies in DR are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summarized information on changes in multi-omics studies in diabetic retinopathy. AGP—α-1-acid glycoprotein; SERPINA3—α-1-antichymotrypsin; SERPINA1—α-1-antitrypsin; SERPINF2—α-2-antiplasmin; AHSG—α-2-HS-glycoprotein; A2M—α-2-macroglobulin; APP—amyloid β A4 protein; AGT—angiotensinogen; SERPINC1—antithrombin III; APOA1—apolipoprotein A-I; APOA2—apolipoprotein A-II; APOA4—apolipoprotein A-IV; APOC1—apolipoprotein C-I; APOC3—apolipoprotein C-III; APOE—apolipoprotein E; ABCF1—ATP-binding cassette subfamily F member 1; HSPG2—basement membrane-specific heparan sulphate proteoglycan core protein; B2M—β-2-microglobulin; CRYBA1—β-crystallin A3; CRP—C-reactive protein; CCL13—C-C motif chemokine 5; CHI3L1—chitinase-3-like protein 1; CLU—clusterin; CFL1—cofilin-1; C1—complement C1; C3—complement C3; C4—complement C4; C7—complement C7; C8—complement C8; CFB—complement factor B; CFH—complement factor H; CFI—complement factor I; ESR1—oestrogen receptor; FGA—fibrinogen; FN1—fibronectin; GSN—gelsolin; GBP3—guanylate-binding protein3; HP—haptoglobin; IGHA1—immunoglobulin α chain; IGHG1—immunoglobulin γ chain; IGHV3-13—immunoglobulin heavy chain V-III region BRO; IGK—immunoglobulin κ chain; IGH—immunoglobulin λ chain; ITIH4—inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain family, member 4; ICAM1—intercellular adhesion molecule 1; CXCL10—interferon γ-induced protein 10; IL1—interleukin-1; IL1RN—interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; IL2R—interleukin-2 receptor; IL6—interleukin-6; IL6R—interleukin-6 receptor; CXCL8—interleukin-8; IL10—interleukin-10; IL12—interleukin-12; IL13—interleukin-13; KRT1—keratin, type II cytoskeletal I; KNG1—kininogen 1; LTF—lactotransferrin; PTAFR—leukocyte platelet-activating factor receptor; CCL3—macrophage inflammatory protein 1; TIMP2—metalloproteinase inhibitor 2; CCL2—monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; CD14—monocyte differentiation antigen CD14; NR1D2—leukocyte platelet-activating factor receptor; SPP1—osteopontin; PTX3—pentraxin-related protein 3; PPIA—peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase a; PRDX2—peroxiredoxin 2; SERPING1—plasma protease C1 inhibitor; SERPINA5—plasma serine protease inhibitor; SERPINE1—plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; PEDF—pigment epithelium-derived factor; PARK7—protein Dj-1; FAM3C—protein FAM3C; F2—prothrombin; RARRES2—retinoic acid receptor responder 2; SAA—serum amyloid A protein; SELE—E-selectin; sgp130—soluble glycoprotein 130; CXCL12—stromal cell-derived factor 1α; TTR—transthyretin; TNF—tumour necrosis factor α; TNFR—tumour necrosis factor receptor; VCAM1—vascular cell adhesion protein 1; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor; FLT1—vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1; VTN—vitronectin; RBP1—retinol-binding protein 1; NUD10—diphosphoinositol polyphosphohydrolase 3 α; NGB—neuroglobin; HBG2—haemoglobin; BY55—CD 160 antigen.

3.6. Muli-Omics Prognostic Biomarkers in DR

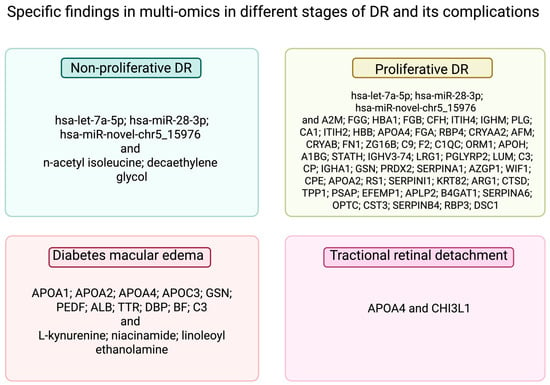

DR is categorised according to the clinical severity of the disease. The early stages are called non-proliferative DR (NPDR), and later, the disease progresses towards proliferative DR (PDR) with retinal neovascularisation [21,22]. The mentioned panel of three miRNAs (hsa-let-7a-5p, hsa-miR-novel-chr5_15976, and hsa-miR-28-3p) was also reported to differentiate between patients with NPDR and PDR [34]. Proteomic analysis indicated upregulation of 37 proteins and downregulation of 19 proteins in the vitreous humour in patients with PDR compared to individuals with other macular tissue defects [45]. Metabolite biomarkers of NPDR in the aqueous humour of T2D patients were described to be n-acetyl isoleucine and decaethylene glycol. Metabolites indicating diabetes macular oedema (DME) were also proposed (L-kynurenine, niacinamide, and linoleoyl ethanolamine) [44]. DME is a complication of DR and is caused by fluid gathering in the macula [22]. Scientists also evaluated pathological pathways of DME, showing increments in 11 proteins (apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein A-II, apolipoprotein A-IV, apolipoprotein C-III, gelsolin, pigment epithelium-derived factor, serum albumin, transthyretin, vitamin D-binding protein, factor B, and C3) in the vitreous humour [46]. Another complication of DR is tractional retinal detachment (TRD). The elevation of apolipoprotein A-IV4 and chitinase-3-like protein 1 was statistically significant in the vitreous humour in TRD patients. Both proteins are linked with sphingolipid metabolism [47]. Specific findings in different stages of DR and its complications are summarised in Figure 2. In addition, an increase in the global level of DNA methylation was found in NDPR, and even higher in PDR [48].

Figure 2.

Specific findings in multi-omics in different stages of DR and its complications. A2M—α-2-macroglobulin; FGG—fibrinogen γ chain; HBA1—haemoglobin subunit α; FGB—fibrinogen β chain; CFH—complement factor H; ITIH4—inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4; IGHM—immunoglobulin heavy constant mu; PLG—plasminogen; CA1—carbonic anhydrase 1; ITIH2—inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2; HBB—haemoglobin subunit β; FGA—fibrinogen α chain; RBP4—retinol-binding protein 4; CRYAA2—α-crystallin A2 chain; AFM—a famin; CRYAB—α-crystallin B chain; FN1—fibronectin; ZG16B—zymogen granule protein 16 homolog B; C9 complement C9; F2—prothrombin; C1QC—complement C1q subcomponent subunit C; ORM1—α-1-acid glycoprotein 1; APOH—β-2-glycoprotein 1; A1BG—α-1B-glycoprotein; STATH—statherin; IGHV3-74—immunoglobulin heavy variable 3-74; LRG1—leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein; PGLYRP2—N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase; LUM—lumican; C3—complement C3; CP—ceruloplasmin; IGHA1—immunoglobulin heavy constant α 1;PRDX2—peroxiredoxin-2; SERPINA1—α-1-antitrypsin; AZGP1—zinc-α-2-glycoprotein; WIF1—Wnt inhibitory factor 1; CPE—carboxypeptidase E; RS1—retinoschisin; SERPINI1—neuroserpin; KRT82—keratin, type II cuticular Hb2; ARG1—arginase-1; CTSD—cathepsin D; TPP1—tripeptidyl-peptidase 1; PSAP—isoform Sap-mu-6 of prosaposin; EFEMP1—EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1; APLP2—amyloid-like protein 2; B4GAT1—β-1,4-glucuronyltransferase 1; SERPINA6—corticosteroid-binding globulin; OPTC—opticin; CST3—cystatin C; SERPINB4—Serpin B4; RBP3—retinol-binding protein 3; DSC1—desmocollin 1; APOA1—apolipoprotein A-I; APOA2—apolipoprotein A-II; APOA4—apolipoprotein A-IV; APOC3—apolipoprotein C-III; GSN—gelsolin; PEDF pigment epithelium-derived factor; ALB—albumin; TTR—transthyretin; DBP—vitamin D-binding protein; BF—factor B; CHI3L1—chitinase-3-like protein 1.

4. Multi-Omics in Other Microvascular Complications

4.1. Multi-Omics in Diabetic Nephropathy

DKD is thought to be responsible for 50% of all ESKD cases [20,49]. Long-lasting hyperglycaemia initiates various pathological mechanisms, changing the levels of inflammatory proteins, the concentration of reactive oxygen species, and resulting in haemodynamic changes. All these alterations lead to leakages in the glomerular membrane and manifest as albuminuria and hypertension [50,51]. Microalbuminuria is a known risk factor leading to progression towards DKD and was investigated in detail in patients with T1D [28,52]. Some bacteria species were thought to influence albuminuria and insulin resistance through G protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) upregulation. Severity of albuminuria in T1D patients was correlated with the abundance of some specific phages.

4.1.1. Genomics in DKD

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) enabled the identification of over 30 genetic loci associated with DKD. Some were linked with the presence of microalbuminuria, whereas others play a role in susceptibility to renal failure, and ENPP7 encodes an enzyme from sphingolipid metabolism [31].

4.1.2. Epigenomics in DKD

In addition, patients with methylation of TP53INP1 were reported to have a lower risk of DKD development [33].

4.1.3. Transcriptomics in DKD

Microalbuminuria was also linked with the dysregulation of 16 miRNAs (miR-320c, miR-6068, miR-1234-5p, miR-6133, miR-4270, miR-4739, miR-371b-5p, miR-638, miR-572, miR-1227-5p, miR-6126, miR-1915-5p, miR-4778-5p, miR-2861, miR-30d-5p, and miR-30e-5p) in the urine of T2D patients with diabetic nephropathy [3]. Evaluation of miR-192+miR-29c in urine was described to detect microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes. Authors also compared the diagnostic value of miRNAs in blood and urine, suggesting higher sensitivity of miRNAs in the latter biofluid [29].

4.1.4. Proteomics in DKD

Presence of specific inflammatory proteins (FGF-23, HGF, IL-10RB, IL-15Rα, PD-L1, SLAMF1, TNFRSG9, and VEGFA) were observed in patients with DKD in T1D and T2D [53]. Furthermore, a systematic review by Ding et al. gathered 28 proteins (AMBP, OPG, C-Megalin, MMP, MMP2, CP, WT1, Elf3, DPP4, RGN, MLL3, VDAC1, CD59, MASP2, CTSA, CTSC, CTSD, CTSE, CTSL1, CTSZ, KLK10, KLIK13, MME, PRTN3, ADAM9, PODXL, IL1B, and CDH1) that might serve as biomarkers of DKD in urine samples in T1D and T2D patients. Some of the proteins were involved in angiogenesis, the renin–angiotensin system, and immune processes [54].

4.1.5. Metabolomics in DKD

In T1D patients, the level of severity of albuminuria was linked with a decrease in four plasma metabolites (ribitol, benzeneacetic acid, decanoic acid, and 3-phenylpropanoic acid), as well as an increment in 2,3-dihydroxybutanoic acid in plasma [52]. A metabolomics study indicated significant changes in blood metabolites from sphingolipid fraction, steroidogenesis, and glucose metabolism in T1D patients with albuminuria [52]. Changes in various amino acid levels and their metabolites (symmetric dimethylarginine, tryptophan and its metabolites, tyrosine, phenylalanine, uracil, 3-hydroxyisobutyrate, glycine, glycolic acid, and 2-methylacetoacetate) were observed in different biofluids in DKD patients. Tryptophan metabolites were associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune processes in the kidneys. Alterations in metabolite levels (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, sphingolipids, ceramide metabolites, and acylcarnitines) were also spotted [55]. Moreover, by combining two omics techniques, scientists proposed a biomarker panel to differentiate early stages of DKD in T2D. They used urine samples to evaluate metabolites (3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, histidine, malonic acid, proline, proline betaine, and uracil) and peptides (pep_1103.99_OAF, pep_1912.08_UMOD, pep_2176.33_VDAC1, pep_2386.21_AMBP, and pep_2520.43_SERPINA1) [56].

4.1.6. Multi-Omics Prognostic Biomarkers in DKD

Not only were diagnostic biomarkers investigated, but their prognostic biomarkers were also explored. Long noncoding RNAs (e.g., lncMALAT1, lncNEAT1, lncMIAT, and lncTUG1) were described to correlate with the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), miRNAs, and protein levels, influencing harmful or protective effects on renal cells [57]. Kammer et al. tried to find prognostic biomarkers of eGFR changes in T2D patients with either incident or early chronic DKD using metabolomic and proteomics. However, only two proteins (KIM-1 and NTproBNP) combined with clinical parameters were relevant in prognosis [58]. On the contrary, Zhao et al. observed that C5, decay-accelerating factor (DAF), and CD59 correlated with the decrease in eGFR [59]. Meanwhile, an increase in complement factor H (CFAH) and a decrease in DAF in urine were suspected to indicate a higher risk of progression to ESKD [59]. The progression to ESKD in both T1D and T2D was linked with five circulating proteins (LAYN, ESAM, DLL1, MAPK11, and endostatin), which were connected with processes of fibrosis in the kidneys [60]. Moreover, seven peptides (fragments of vitronectin precursor, isoform 1 of fibrinogen α chain precursor, prothrombin precursor, and inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4) in urine were associated with different stages of renal injury in T2D [61]. Additionally, 15 genes were found to have significantly different methylation patterns in DKD and/or ESKD in T1D patients [62]. Chen et al. described 12 methylated loci correlated with kidney failure development in T1D patients [63]. Biomarkers for monitoring DKD progression were also identified in combined proteomic (α2-macroglobulin, cathepsin D, and CDH1) and metabolomic (glycerol-3-galactoside) analysis of T2D participants’ serum [64]. Interestingly, changes in several miRNAs (miR-26a-5p, miR-802, and miR-155) also correlate with obesity-associated nephropathy in T2D patients [65].

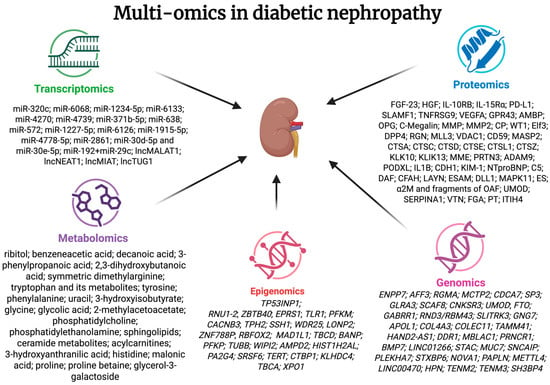

Multi-omics studies in DKD uncovered changes in various mechanisms, including inflammation, immunological response, neovascularization, steroidogenesis, oxidative stress, renin–angiotensin response, sphingolipid, and glucose metabolism. Many alterations were correlated with the presence of microalbuminuria. Changes found in multi-omics studies in DKD are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summarized information on changes in multi-omics studies in diabetic nephropathy. FGF-23—fibroblast growth factor 23; HGF—hepatocyte growth factor; IL-10RB—interleukin 10 receptor, β subunit; IL-15Rα—interleukin 15 receptor, α subunit; PD-L1—programmed death-ligand 1; SLAMF1—signalling lymphocytic activation molecule 1; TNFRSG9—tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9; VEGFA—vascular endothelial growth factor A; GPR43—G protein-coupled receptor 43; AMBP—α-1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor; OPG—osteoprotegerin; C-megalin; MMP—gelatinase; MMP2—matrix metallopeptidase 2; CP—ceruloplasmin; WT1—Wilm’s tumour-1; Elf3—eukaryotic initiation factor 3; DPP4—dipeptidyl peptidase-IV; RGN—regucalcin; MLL3—myeloid-lineage leukaemia protein 3 homolog; VDAC1—voltage-dependent anion channel 1; CD59—inhibitor of the complement membrane attack complex; MASP2—mannan-binding lectin serine protease 2; CTSA—cathepsin A; CTSC—cathepsin C; CTSD—cathepsin D; CTSE—cathepsin E; CTSL1—cathepsin L; CTSZ—cathepsin X/Z/P; KLK10—kallikrein related peptidase 10; KLIK13 kallikrein related peptidase 13; MME—neprilysin; PRTN3—proteinase 3; ADAM9—a disintegrin and a metalloprotease 9; PODXL—podocalyxin; IL1B—interleukin-1 β; CDH1—E-cadherin; KIM-1—kidney injury molecule 1; NTproBNP—N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; C5 complement C5; DAF—decay-accelerating factor; CFAH—complement factor H; LAYN—layilin; ESAM—endothelial cell-selective adhesion molecule; DLL1—delta-like protein 1; MAPK11—mitogen-activated protein kinase 11; ES—endostatin; α2M—α2-macroglobulin and fragments of OAF—out at first protein; UMOD—uromodulin; SERPINA1—α-1-antitrypsin; VTN—vitronectin precursor; FGA—fibrinogen α chain precursor; PT—prothrombin precursor; ITIH4—inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4.

4.2. Multi-Omics in Diabetic Neuropathy (DN)

DN is caused by damages in peripheral and autonomic nerves due to loss of myelination and reduced perfusion. The damages are thought to be influenced by inflammation, oxidative stress, changes in energy metabolism and activation of PI3K-Akt signalling [22,27].

4.2.1. Genomics in DN

In GWASs, three genetic loci were associated with DN. MAPK14 encodes a protein involved in responses to proinflammatory cytokines, NRP2 is involved in neovascularization and neuronal regeneration, and SCN2A is thought to have a protective effect [31].

4.2.2. Epigenomics in DN

Epigenetic changes in genes involved in immune response, regulation of extracellular matrix, and PI3K-Akt signalling were found in sural nerves from donors with T2D and peripheral DN [66].

4.2.3. Transcriptomics in DN

Chang et al. described miRNAs involved in the regulation of neuropathic pain through modifying inflammation of neurons, potential of responses to stimuli, and synaptic plasticity. MiRNAs were reported to regulate pain signalling by modulation of protein kinase genes expression [67].

4.2.4. Proteomics in DN

Changes in three proteins (SPP1, eEF2, and TNR), one amino acid (glutamate), one amino acid derivative (N-acetylaspartic acid), and two phospholipid metabolites (S-adenoylmethionine and choline) were suggested to alter energy metabolism and myelin synthesis [68]. Moreover, four peptides in serum were found to differentiate patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy from those with diabetes mellitus. One was a fragment of the apolipoprotein C-I [69]. The increment of apolipoprotein C-I was spotted in patients with T2D. Additionally, post-translational changes of apolipoprotein C-I might prompt changes in glucose metabolism [70].

4.2.5. Metabolomics in DN

The elevation in 12 metabolite concentrations (dimethylarginine, N6-acetyllysine, N-acetylhistidine, N,N,N-trimethyl-alanylproline betaine, cysteine, 7-methylguanine, N6-carbamoylthreonyladenosine, pseudouridine, 5-methylthioadenosine, N2,N2-dimethylguanosine, aconitate, and C-glycosyl tryptophan) was presented as specific to T2D patients with distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSPN). These metabolites were associated with a decrease in endothelial nitric oxide synthase and an elevation of reactive oxygen species. In addition, N,N,N-trimethyl-alanylproline betaine was linked with muscle atrophy [71]. In another article, the increment of phenylacetylglutamine was significant in patients with DSPN [72]. In multi-omics analysis, a decrease in amino acid and phospholipid metabolite levels was spotted in the dorsal root ganglia of donors with DN. Interestingly, changes in gamma-glutamyl, branched-chain amino acid metabolism, and triacylglycerol levels were found to distinguish obese patients with peripheral neuropathy independent of glycaemic impairment [73].

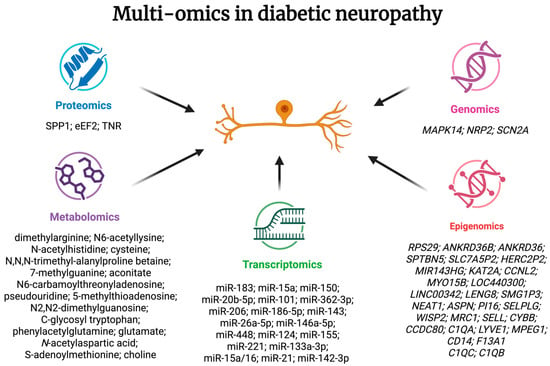

Multi-omics studies in DN revealed a complex mechanism behind this complication: modification of inflammation, immunological response, angiogenesis, stimuli responses, and pain transduction. Other disruptions include changes in energy metabolism, increases in reactive oxygen species, and a reduction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Summarized information on multi-omics in DN is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Summarized information on changes in multi-omics studies in diabetic neuropathy. SPP1—osteopontin; eEF2—eukaryotic elongation factor 2; TNR—tenascin-R.

4.3. Changes in Multi-Omics Studies Common to All Microvascular Complications of Diabetes

Long-lasting hyperglycaemia leads to pathological processes in the kidneys, retina, and neurons simultaneously. Therefore, scientists investigated biomarkers that might be expressed in more than one microvascular complication, as they share some pathophysiological background, e.g., inflammation, neovascularization, apoptosis, and fibrosis [74]. Alterations in miR-126, miR-29, and miR-17 were observed in DKD and DR, while changes in miR-146a and miR-27 were found in all three complications [74,75,76]. In previously conducted proteomic studies, four proteins (HLA-DRA, AGER, HSPA1A, and HSPA1B) were associated with all complications [77]. Meanwhile, lower levels of tyrosine and alanine were correlated with a higher risk of microvascular complication development [78]. Mono-sialylated apolipoprotein-CIII was reported to have a protective effect on DR, whereas disialylated apolipoprotein-CIII was associated with an increased risk of DR [79]. In metabolomic studies focusing on patients with T1D, changes in the levels of eight metabolites (2,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid, ribonic acid, myoinositol, ribitol, 3,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid, valine, glycine, 2-hydroxyisovaleric acid) were found in DKD, DR, and DN [80].

5. Potential Therapeutic Use of Multi-Omics in Microvascular Complications of Diabetes

Multi-omics analysis might be useful in the search for new therapeutic targets in microvascular complications of diabetes, as well as in the evaluation of response to already existing treatments for those complications. Firstly, in DR patients, the anti-VEGF treatment was investigated. Predictive biomarkers in the aqueous humour (trigonelline and 4-methylcatechol-2-sulfate) for good response to anti-VEGF therapy were found [44]. Two miRNAs were proposed as novel therapeutic targets in DR [21]. Intravitreal miR-126 was observed to alleviate proliferation and migration of endothelial cells in rats [81]. MiR-192 was proposed to mitigate inflammation and angiogenesis in rats [82]. Some peptides, like somatostatin, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide, and glucagon-like peptide 1, play a neuroprotective role in the retina. Their usage in the early stages of DR remains a topic in experimental studies, accompanied by the search for a non-invasive method of administration [24,83]. Secondly, molecular response to sartan therapy was assessed in patients with albuminuria based on proteomics. A total of peptides in urine after candesartan treatment returned to values similar to those in patients without albuminuria [84]. Peptide profiles in the urine revealed significant changes after 2 years of irbesartan therapy [85]. Proteomic test (CKD273) was also used to differentiate patients with a high risk of DKD development in a study evaluating primary prevention of this complication [86]. The molecular mechanism behind a decrease in albuminuria risk and a reduction of later DKD development by sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors was investigated using metabolomics and transcriptomics approaches, revealing changes in mitochondria through glycine degradation and energy metabolism through tricarboxylic acid cycle and L-carnitine biosynthesis [55,87]. Next, four candidate genes (ACY1, OPLAH, SDS, and TYR) and four proteins (TGFB1, HP, ITIH3, and ASIP) were identified as potential therapeutic targets in personalized medicine of DKD in T2D patients [56,88]. Then, in the study focused on DN, new potential therapeutic targets were found in proteomic analysis (ITM2B, CREG1, CD14, and PLXNA4). These proteins were described to have a protective role in diabetic polyneuropathy [89]. As miR-126 is involved in endothelial function and neovascularization, it was suggested as a potential therapeutic target in diabetes complications. Additionally, miRNA-22 was proposed as a potential novel therapeutic target in obesity and T2D [19].

6. Conclusions

The assessment of genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics enabled insight into pathological mechanisms in DR, DN, and DKD. Multi-omics studies distinguished potential diagnostic biomarkers, which might allow for the detection of microvascular complications of diabetes at earlier stages, evaluation of responses to already available treatments, e.g., anti-VEGF therapy and SGLT2 inhibitors, which could be applied in the search for novel therapeutic targets. In the future, it would be beneficial to compare alterations found in the aqueous and vitreous humour with biomarkers available in patients’ serum and to expand the findings by using a less invasive technique. This would enable the development of biomarkers more easily applied in practical usages. Future research should also prioritize longitudinal, large-scale multi-omics studies with cross-validation across different populations to advance biomarker translation and develop personalized strategies for early detection, risk stratification, and treatment of microvascular complications of diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and J.G.-A.; data curation, J.G.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.-A.; writing—review and editing, A.Z.; visualization, J.G.-A.; supervision, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

All figures were created with the use of BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DAF | decay-accelerating factor |

| DKD | diabetic kidney disease |

| DN | diabetic neuropathy |

| DME | diabetes macular oedema |

| DR | diabetic retinopathy |

| DSPN | distal symmetric polyneuropathy |

| ESKD | end-stage kidney disease |

| GWASs | genome-wide association studies |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| NPDR | non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| MiRNA | microRNA |

| MODY | maturity-onset diabetes of the young |

| OCT | optical coherence tomography |

| PDR | proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| SGLT2 | sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 |

| T1D | type 1 diabetes |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

| TRD | tractional retinal detachment |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Dar, M.A.; Arafah, A.; Bhat, K.A.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.S.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, S.M.; Rashid, S.M.; Rehman, M.U. Multiomics Technologies: Role in Disease Biomarker Discoveries and Therapeutics. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2023, 22, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, M.; Asmis, R.; Hawkins, G.A.; Howard, T.D.; Cox, L.A. The Need for Multi-Omics Biomarker Signatures in Precision Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delić, D.; Eisele, C.; Schmid, R.; Baum, P.; Wiech, F.; Gerl, M.; Zimdahl, H.; Pullen, S.S.; Urquhart, R. Urinary Exosomal miRNA Signature in Type II Diabetic Nephropathy Patients. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Metabolomics for Investigating Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1819–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, G.S.; Kaur, G.; Carbone, G.M.; Shinde, D. Metabolomics in Oncology. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6, e1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassareo, P.P.; McMahon, C.J. Metabolomics: A New Tool in Our Understanding of Congenital Heart Disease. Children 2022, 9, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.S.; Saraiva, F.; Ferreira, R.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Barros, A.S.; Diaz, S.O. Metabolomics and Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornstad, P.; Dart, A.; Donaghue, K.C.; Dost, A.; Feldman, E.L.; Tan, G.S.; Wadwa, R.P.; Zabeen, B.; Marcovecchio, M.L. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications in Children and Adolescents with Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1432–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.J.; Ellard, S. Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young: Identification and Diagnosis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Lab. Med. 2013, 50, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeley, S.A.W.; Polak, M.; Njølstad, P.R.; Barbetti, F.; Williams, R.; Castano, L.; Raile, K.; Chi, D.V.; Habeb, A.; Hattersley, A.T.; et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: The diagnosis and management of monogenic diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, E.R. Personalized Medicine in Diabetes: The Role of ‘Omics’ and Biomarkers. Diabetes Med. 2016, 33, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V.; Zhong, J.; Massier, L.; Tanriverdi, K.; Hwang, S.-J.; Haessler, J.; Nayor, M.; Zhao, S.; Perry, A.S.; Wilkins, J.T.; et al. Targeted Proteomics Reveals Functional Targets for Early Diabetes Susceptibility in Young Adults. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2024, 17, e004192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allesøe, R.L.; Lundgaard, A.T.; Hernández Medina, R.; Aguayo-Orozco, A.; Johansen, J.; Nissen, J.N.; Brorsson, C.; Mazzoni, G.; Niu, L.; Biel, J.H.; et al. Discovery of Drug–Omics Associations in Type 2 Diabetes with Generative Deep-Learning Models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar, O.; Hernandez, L.F.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Nicora, C.D.; Ansong, C.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Bain, J.R.; Myer, C.J.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Buchwald, P.; et al. Parallel Multi-Omics in High-Risk Subjects for the Identification of Integrated Biomarker Signatures of Type 1 Diabetes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenu, E.W.; Harris, M.; Hamilton-Williams, E.E. Circulating biomarkers during progression to type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1117076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollé, O.G.; Ruys, S.P.D.; Lemmer, J.; Hubinon, C.; Martin, M.; Herinckx, G.; Gatto, L.; Vertommen, D.; Lysy, P.A. Plasma proteomics in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes identifies new potential biomarkers of partial remission. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Dragan, I.; Tran, V.D.T.; Fung, C.H.; Kuznetsov, D.; Hansen, M.K.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Hart, L.M.; Slieker, R.C.; Donnelly, L.A.; et al. Multi-omics subgroups associated with glycaemic deterioration in type 2 diabetes: An IMI-RHAPSODY Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1350796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, S.; Vigo, P.; Margiotta, F.; Scheele, U.S.; Panella, R.; Kauppinen, S. The Role of microRNA-22 in Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023 Diabetes Care American Diabetes Association. Available online: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/46/Supplement_1/S19/148056/2-Classification-and-Diagnosis-of-Diabetes (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ciorba, A.L.; Saber, S.; Abdelhamid, A.M.; Keshk, N.; Elnaghy, F.; Elmorsy, E.A.; Abu-Khudir, R.; Hamad, R.S.; Abdel-Reheim, M.A.; Farrag, A.A.; et al. Diabetic Retinopathy in Focus: Update on Treatment Advances, Pharmaceutical Approaches, and New Technologies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 214, 107307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasto, W.; Patel, V.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K. Prevention of Microvascular Complications of Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2021, 50, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziej, M.; Waszczykowska, A.; Korzeniewska-Dyl, I.; Pyziak-Skupien, A.; Walczak, K.; Moczulski, D.; Jurowski, P.; Młynarski, W.; Szadkowska, A.; Zmysłowska, A. The HD-OCT Study May Be Useful in Searching for Markers of Preclinical Stage of Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó, R.; Simó-Servat, O.; Bogdanov, P.; Hernández, C. Diabetic Retinopathy: Role of Neurodegeneration and Therapeutic Perspectives. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 11, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Radke, N.V.; Amarasekera, S.; Park, D.H.; Chen, N.; Chhablani, J.; Wang, N.-K.; Wu, W.-C.; Ng, D.S.C.; Bhende, P.; et al. Updates on Medical and Surgical Managements of Diabetic Retinopathy and Maculopathy. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 14, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J.; Fadavi, H.; Ishibashi, F.; Shore, A.C.; Tavakoli, M. Advances in Screening, Early Diagnosis and Accurate Staging of Diabetic Neuropathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 671257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Vetrano, E.; Beccia, D.; Brin, C.; Alfano, M.; Di Salvo, J.; Epifani, R.; Piacevole, A.; Tagliaferri, G.; et al. Peripheral Neuropathy in Diabetes Mellitus: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Diagnostic Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, N.; Bandinelli, S.; Mangili, R.; Penno, G.; Rottiers, R.E.; Fuller, J.H. Microalbuminuria in Type 1 Diabetes: Rates, Risk Factors and Glycemic Threshold. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, Y. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of microRNAs in the Diagnosis of Early Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1432652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; McCoy, R.G.; Aleppo, G.; Balapattabi, K.; Beverly, E.A.; Briggs Early, K.; Bruemmer, D.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Ekhlaspour, L.; et al. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S239–S251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojima, N.; Yamauchi, T. Progress in Genetics of Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023, 14, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Shah, K.P.; Pollack, S.; Toppila, I.; Hebert, H.L.; McCarthy, M.I.; Groop, L.; Ahlqvist, E.; Lyssenko, V.; Agardh, E.; et al. A Genome-wide Association Study Suggests New Evidence for an Association of the NADPH Oxidase 4 (NOX 4) Gene with Severe Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetes. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, E811–E819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, T.; Xing, C.; Han, F.; Mao, H. Causal Effects of Oxidative Stress on Diabetes Mellitus and Microvascular Complications: Insights Integrating Genome-Wide Mendelian Randomization, DNA Methylation, and Proteome. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milluzzo, A.; Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Sciacca, L.; Agodi, A. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Type 2 Diabetes Retinopathy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Nunes, M.K.; Silva, A.S.; de Queiroga Evangelista, I.W.; Filho, J.M.; Gomes, C.N.A.P.; do Nascimento, R.A.F.; Luna, R.C.P.; de Carvalho Costa, M.J.; de Oliveira, N.F.P.; Persuhn, D.C. Hypermethylation in the promoter of the MTHFR gene is associated with diabetic complications and biochemical indicators. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2017, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.K.d.S.; Silva, A.S.; Evangelista, I.W.d.Q.; Filho, J.M.; Gomes, C.N.A.P.; Nascimento, R.A.F.D.; Luna, R.C.P.; Costa, M.J.d.C.; de Oliveira, N.F.P.; Persuhn, D.C. Analysis of the DNA methylation profiles of miR-9-3, miR-34a, and miR-137 promoters in patients with diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2018, 32, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Gu, C.; Meng, C.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; He, S.; Lai, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Qiu, Q. DNA hypermethylation of PLTP mediated by DNMT3B aggravates vascular dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy via the AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Clin. Epigenetics 2025, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, G.Y.-P.; Yu, F.; Bayless, K.J.; Ko, M.L. MicroRNA-150 (miR-150) and Diabetic Retinopathy: Is miR-150 Only a Biomarker or Does It Contribute to Disease Progression? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Qiu, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Meng, Z.; Li, H.; Guo, X.; Zeng, J.; et al. Exosomal miRNA Profiling in Liquid Biopsy of Vitreous in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.A.; El-Hefnawy, S.M.; Kasemy, Z.A.; Alhagaa, A.A.; Nooh, M.Z.; Arafat, E.S. Mi-RNA-93 and Mi-RNA-152 in the Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 79, 10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, H.; Robinson, R.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, S. Proteomic Biomarkers of Retinal Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-W.; Wang, Y.; Pan, C.-W. Metabolomics in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancel, P.; Martin, J.C.; Doukbi, E.; Houssays, M.; Gascon, P.; Righini, M.; Matonti, F.; Svilar, L.; Valmori, M.; Tardivel, C.; et al. Untargeted Multiomics Approach Coupling Lipidomics and Metabolomics Profiling Reveals New Insights in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liao, N.; Ji, Y.; Mi, L.; Gan, Y.; Su, Y.; Wen, F.; et al. Multi-Omics Integration With Machine Learning Identified Early Diabetic Retinopathy, Diabetic Macula Edema and Anti-VEGF Treatment Response. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Udaya, P.; Jeya Maheshwari, J.; Kohli, P.; Parida, H.; Kannan, N.B.; Ramasamy, K.; Dharmalingam, K. Comparative Proteomics of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy in People with Type 2 Diabetes Highlights the Role of Inflammation, Visual Transduction, and Extracellular Matrix Pathways. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.S.; Rasmussen, M.; Grauslund, J.; Subhi, Y.; Cehofski, L.J. Proteomic Analysis of Vitreous Humour of Eyes with Diabetic Macular Oedema: A Systematic Review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, E1043–E1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, R.; Tang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, Z.; Han, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chu, Y. Identification of Unique Biomarkers for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy with Tractional Retinal Detachment by Proteomics Profiling of Vitreous Humor. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghbooli, Z.; Hossein-nezhad, A.; Larijani, B.; Amini, M.; Keshtkar, A. Global DNA methylation as a possible biomarker for diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2015, 31, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogeveen, E.K. The Epidemiology of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Kidney Dial. 2022, 2, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordheim, E.; Geir Jenssen, T. Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Connect. 2021, 10, R151–R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umanath, K.; Lewis, J.B. Update on Diabetic Nephropathy: Core Curriculum 2018. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clos-Garcia, M.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Winther, S.A.; Henriksen, P.; Ali, M.; Fan, Y.; Stankevic, E.; Lyu, L.; Vogt, J.K.; Hansen, T.; et al. Multiomics Signatures of Type 1 Diabetes with and without Albuminuria. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1015557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heck, J.I.P.; Ajie, M.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Tack, C.J.; Stienstra, R. Circulating Inflammatory Proteins Are Elevated in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes and Associated to Complications. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Du, J.; Han, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Proteome in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 866252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Ma, R.C.W. Metabolomics in Diabetes and Diabetic Complications: Insights from Epidemiological Studies. Cells 2021, 10, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Qu, X.; Zhu, P.; Wo, F.; Xu, X.; Jin, J.; He, Q.; Wu, J. Integration of Metabolomics and Peptidomics Reveals Distinct Molecular Landscape of Human Diabetic Kidney Disease. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3188–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrica, L.; Hogea, E.; Gadalean, F.; Vlad, A.; Vlad, M.; Dumitrascu, V.; Velciov, S.; Gluhovschi, C.; Bob, F.; Ursoniu, S.; et al. Long Noncoding RNAs May Impact Podocytes and Proximal Tubule Function through Modulating miRNAs Expression in Early Diabetic Kidney Disease of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammer, M.; Heinzel, A.; Willency, J.A.; Duffin, K.L.; Mayer, G.; Simons, K.; Gerl, M.J.; Klose, C.; Heinze, G.; Reindl-Schwaighofer, R.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Prognostic Biomarkers Derived from Multiomics Panels Helps Discrimination of Chronic Kidney Disease Trajectories in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Su, Q.; Tang, L.; Bai, L.; et al. Urinary Complement Proteins and Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease: Quantitative Urinary Proteomics in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Biopsy-Proven Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2021, 44, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Looker, H.C.; Satake, E.; Saulnier, P.J.; Md Dom, Z.I.; O’Neil, K.; Ihara, K.; Krolewski, B.; Galecki, A.T.; Niewczas, M.A.; et al. Results of Untargeted Analysis Using the SOMAscan Proteomics Platform Indicates Novel Associations of Circulating Proteins with Risk of Progression to Kidney Failure in Diabetes. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Du, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhang, M. Discovery and Verification of Urinary Peptides in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with Kidney Injury. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Duffy, S.; Kettyle, L.M.; McGlynn, L.; Sandholm, N.; Salem, R.M.; Thompson, A.; Swan, E.J.; Kilner, J.; Rossing, P.; et al. Differential Methylation of Telomere-Related Genes Is Associated with Kidney Disease in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes. Genes 2023, 14, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Satake, E.; Pezzolesi, M.G.; Md Dom, Z.I.; Stucki, D.; Kobayashi, H.; Syreeni, A.; Johnson, A.T.; Wu, X.; Dahlström, E.H.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Blood DNA Methylation, Genetic Variants, Circulating Proteins, microRNAs, and Kidney Failure in Type 1 Diabetes. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadj3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gui, Y.; Wang, M.S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, T.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Serum Integrative Omics Reveals the Landscape of Human Diabetic Kidney Disease. Mol. Metab. 2021, 54, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caus, M.; Eritja, À.; Bozic, M. Role of microRNAs in Obesity-Related Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Eid, S.A.; Elzinga, S.E.; Pacut, C.; Feldman, E.L.; Hur, J. Correction to: Genome-Wide Profiling of DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Identifies Candidate Genes for Human Diabetic Neuropathy. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Čok, Z.; Yu, L. Protein Kinases as Mediators for miRNA Modulation of Neuropathic Pain. Cells 2025, 14, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, M.; Yun, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Cassidy, M.; Hall, B.; Kulkarni, A.B. Integrative Multiomic Analyses of Dorsal Root Ganglia in Diabetic Neuropathic Pain Using Proteomics, Phospho-Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z. Serum Biomarker of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy Indentified by Differential Proteomics. Front. Biosci. 2011, 16, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koska, J.; Hu, Y.; Furtado, J.; Billheimer, D.; Nedelkov, D.; Schwenke, D.; Budoff, M.J.; Bertoni, A.G.; McClelland, R.L.; Reaven, P.D. Relationship of Plasma Apolipoprotein C-I Truncation With Risk of Diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and the Actos Now for the Prevention of Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Cai, M.; Han, X.; Lu, H. Ultra-high Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry-based Metabolomics Study of Diabetic Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023, 14, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cai, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Tian, J.; Jin, S.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Lu, B.; et al. Phenylacetylglutamine as a Novel Biomarker of Type 2 Diabetes with Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy by Metabolomics. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2022, 46, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Savelieff, M.G.; Rumora, A.E.; Alakwaa, F.M.; Callaghan, B.C.; Hur, J.; Feldman, E.L. Plasma Metabolomics and Lipidomics Differentiate Obese Individuals by Peripheral Neuropathy Status. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; El-Mahdy, H.A.; Eldeib, M.G.; Doghish, A.S. miRNAs as Cornerstones in Diabetic Microvascular Complications. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 138, 106978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, Y.; Farahani, M.; Asl, E.R.; Barati, S.; Naseri, N.; Ghoshal, K. Exploring the Role of miR-126 in Diabetes and Its Complications: A Comprehensive Review. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, R.; Yao, Y.; Guan, H.; Tian, J. Discovering Diabetes Complications-Related microRNAs: Meta-Analyses and Pathway Modeling Approach. BMC Med. Genom. 2025, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Xu, F.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Zheng, J.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Larsson, S.C. Plasma Proteins and Onset of Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications: Proteome-Wide Mendelian Randomization and Colocalization Analyses. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, P.; Rankin, N.; Li, Q.; Mark, P.B.; Würtz, P.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Marre, M.; Poulter, N.; Hamet, P.; Chalmers, J.; et al. Circulating Amino Acids and the Risk of Macrovascular, Microvascular and Mortality Outcomes in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: Results from the ADVANCE Trial. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, A.; Demus, D.; Slieker, R.C.; Nicolardi, S.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Elders, P.J.M.; Lieverse, A.G.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; ‘t Hart, L.M.; Wuhrer, M.; et al. Apolipoprotein-CIII O-Glycosylation Is Associated with Micro- and Macrovascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotbain Curovic, V.; Sørland, B.A.; Hansen, T.W.; Jain, S.Y.; Sulek, K.; Mattila, I.M.; Frimodt-Moller, M.; Trost, K.; Legido-Quigley, C.; Theilade, S.; et al. Circulating Metabolomic Markers in Association with Overall Burden of Microvascular Complications in Type 1 Diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2024, 12, e003973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Lu, Z.; Xuan, Y.; Meng, W.; Ye, L.; Fang, D.; Zhou, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-126 Suppresses the Proliferation and Migration of Endothelial Cells in Experimental Diabetic Retinopathy by Targeting Polo-like Kinase 4. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 47, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells-secreted Extracellular Vesicles Containing microRNA-192 Delays Diabetic Retinopathy by Targeting ITGA1. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 5036–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó, R.; Simó-Servat, O.; Bogdanov, P.; Hernández, C. Neurovascular Unit: A New Target for Treating Early Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, K.; Mischak, H.; Parving, H.H.; Christensen, P.K.; Walden, M.; Hillmann, M.; Kaiser, T. Impact of diabetic nephropathy and angiotensin II receptor blockade on urinary polypeptide patterns. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Mischak, H.; Zürbig, P.; Parving, H.-H.; Rossing, P. Urinary Proteome Analysis Enables Assessment of Renoprotective Treatment in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Microalbuminuria. BMC Nephrol. 2010, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindhardt, M.; Persson, F.; Currie, G.; Pontillo, C.; Beige, J.; Delles, C.; Von Der Leyen, H.; Mischak, H.; Navis, G.; Noutsou, M.; et al. Proteomic Prediction and Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System Inhibition Prevention Of Early Diabetic nephRopathy in TYpe 2 Diabetic Patients with Normoalbuminuria (PRIORITY): Essential Study Design and Rationale of a Randomised Clinical Multicentre Trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, S.; Hammarstedt, A.; Nagaraj, S.B.; Nair, V.; Ju, W.; Hedberg, J.; Greasley, P.J.; Eriksson, J.W.; Oscarsson, J.; Heerspink, H.J.L. A Metabolomics-based Molecular Pathway Analysis of How the Sodium-glucose Co-transporter-2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin May Slow Kidney Function Decline in Patients with Diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therapeutic Targets for Diabetic Kidney Disease: Proteome-Wide Mendelian Randomization and Colocalization Analyses—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38211557/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Chen, X.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, T.; Sun, N.; Liu, S.; Guo, H.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Y. Identification of Potential Drug Targets for Diabetic Polyneuropathy through Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.