Abstract

Background/Objectives: In populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), it is unknown whether the survival benefits of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) differ by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). To address this question and in the absence of definitive randomized controlled trials, we performed a retrospective observational study of US Veterans with T2DM to evaluate mortality hazard ratios associated with GLP-1 RA use at different eGFR levels. Methods: This administrative claims-based cohort included 1,188,052 U.S. Veterans with T2DM as of 1 January 2020. Initiation of GLP-1 RA was treated as a time-dependent variable and vital status of Veterans was followed until 31 December 2023. Results: A total of 31,676 Veterans met inclusion criteria. Over the study timeframe, 6.1% initiated treatment with GLP-1 RA and 57.7% died. Older age and eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 were associated with a decreased likelihood of GLP-1 RA initiation. In contrast, younger age and lower comorbidity burden were associated with decreased mortality, a finding that persisted even after adjustment for several baseline covariates. Conclusions: Among those with T2DM and eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2, initiation of GLP-1 RA was associated with improved survival. This association remained significant with decreasing levels of kidney function, as well as among those receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT). In conclusion, longer survival was observed both in participants on KRT and in those with eGFR 15–24 mL/min/1.73 m2 not on KRT, but these findings were not observed among those with eGFR ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), obesity, and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) frequently coexist and collectively contribute to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and death [1,2,3,4,5]. Beyond their known role of glycemic control in the setting of T2DM, emerging evidence demonstrates significant cardiovascular and kidney benefits associated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) therapy through reductions in the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death [6,7]. These benefits extend to patients with established cardiovascular disease, highlighting the therapeutic relevance of GLP-1 RA in this high-risk population. In addition, GLP-1 RA have emerged as a potential therapeutic class for the management of CKD in patients with T2DM. Studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 RA can slow the progression of CKD, reduce the risk of kidney failure, and, in some cases, improve kidney function [7]. These protective effects are likely mediated through various mechanisms, including improved blood pressure control, reductions in albuminuria, and potential direct effects on kidney hemodynamics [8,9].

Current clinical guidelines recommend GLP-1 RA for glycemic control in patients with CKD and coexisting T2DM but have not endorsed their use for primary kidney protection [10,11]. However, semaglutide has since been shown to be kidney protective in patients with albuminuric CKD, expanding the therapeutic rationale for GLP-1 RA use in CKD [7]. While GLP-1 RA appear to confer benefit in the population with T2DM and CKD where estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) are between 25 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2, evidence remains limited for patients with T2DM and severe kidney dysfunction with eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2, a group at high risk of cardiovascular disease, ESKD, and death. To address this gap and evaluate its safety and possible benefits in this population, we conducted a national observational study to examine mortality risk across eGFR levels associated with GLP-1 RA use in U.S. Veterans with T2DM.

2. Methods

2.1. Objectives

The primary objective was to estimate mortality hazard ratios, adjusted for baseline covariates, associated with initiation of GLP-1 RA among Veterans with T2DM and an eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2 as of 1 January 2020, within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Additional objectives included the evaluation of GLP-1 RA associated hazard ratios for higher eGFR levels.

2.2. Data Sources and Study Population

We used VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) files for this retrospective observational study. VINCI files compiled demographic, laboratory, inpatient, and administrative claims data to study subjects with eGFR levels < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2 across the VHA [12]. To calculate eGFR, the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation without the race coefficient was utilized [13,14].

The study population included subjects with T2DM on 1 January 2020 who had at least one VHA provider encounter prior to 2019 and an eGFR measured in 2019. This requirement excluded 8.3% of the original subjects. T2DM was defined as one inpatient diagnosis with a discharge date in 2019, one outpatient diagnosis in 2019 with another such claim in the prior 365 days, or two prescriptions for a diabetes medication (drug class HS501 or medications with names containing the terms ‘insulin’, ‘metformin’, ‘glimepiride’, ‘glipizide’, ‘glyburide’, ‘nateglinide’, ‘repaglinide’, ‘rosiglitazone’, ‘pioglitazone’, ‘acarbose’, ‘miglitol’, ‘long-acting analogs’, ‘rapid-acting analogs’, ‘short-acting’, ‘intermediate-acting’, ‘pre-mixed’, ‘exenatide’, ‘dulaglutide’, ‘albiglutide’, ‘liraglutide’, ‘alogliptin/pioglitazone’, ‘canagliflozin/metformin’, ‘dapagliflozin/metformin’, ‘glyburide/metformin’, or ‘linagliptin/metformin’) in 2019, or one prescription for a diabetes medication with a supply greater than 30 days in 2019.

The primary exposure variable was conditional, time-dependent GLP-1 RA initiation, defined as the first date GLP-1 RA therapy was dispensed between 2000 and 2023 for albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide, or tirzepatide. The coprimary subgroups of interest were defined by kidney function: eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and eGFR ≥ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 but <25 mL/min/1.73 m2, based on the most recent serum creatinine level from 2019. This time-dependent approach was specifically chosen to control for possible immortal time bias, which can arise if exposure is misclassified from baseline rather than point of treatment initiation. Baseline clinical conditions were defined as one inpatient diagnosis in 2019, one procedure code in 2019, or one outpatient diagnosis in 2019 with a corresponding claim within the preceding 365 days. Weight and blood pressure levels were the latest taken in 2019; height was the most recent measurement before 2020 at age ≥ 18 years. Additional variables included the latest low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), hemoglobin A1c, and urinary albumin/creatinine ratios obtained in 2019. Unmeasured, missing, or unavailable baseline clinical conditions or labs were handled as a separate category (“not measured”). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (#1594650) prior to initiation of the study. Vital measurements were collected from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) Vital Signs domain [15].

2.3. Analysis

The main outcome variable was time to death between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2023. The Chi2 and Poisson tests, respectively, were used to compare categorical characteristics and GLP-1 RA initiation rates. To assess mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazards model with GLP-1 RA initiation treated as a conditional, time-dependent variable [16]. In this model, subjects contributed person-time to the unexposed group from study initiation until GLP-1 RA initiation. After initiation, person-time was then contributed by the exposed group for the remainder of the follow up period or until the primary outcome was reached. Proportional hazards regression was applied to calculate the following: hazard ratios for GLP-1 RA initiation and mortality hazard ratios associated with GLP-1 RA use. Assessment of mortality hazards employed three modeling strategies: unadjusted; adjustments made for age, sex, and race (Model 1); and adjustments for all baseline covariates (Model 2). All visualizations were performed using Highcharts [17]. R version 4.4.1 (Puppy Cup, 24 April 2024) was used for data analysis [18].

3. Results

Among GLP-1 RA prescriptions, semaglutide accounted for the majority (65.7%), followed by dulaglutide (18.4%), liraglutide (15.8%) and exenatide (0.1%). Baseline descriptive characteristics of the overall population, stratified by level of eGFR, are shown in Table 1. A total of 31,676 Veterans met study inclusion criteria. Most were > 50 years of age and of male sex (97.9% and 97.2%, respectively). Overall, 35.8% were Black and 7.9% reported Hispanic ethnicity. One-third lived in urban settings and nearly half were located in the Southern region of the United States. Nearly two-thirds (59.9%) had blood pressures < 140/90 mmHg, approximately half had a hemoglobin A1c < 7%, and 16.2% of the overall cohort had a urinary albumin/creatinine ratio < 300 mg/g (Supplementary Table S1). The most prescribed medications were statins (52.1%), insulin (34.4%), and ACE inhibitor/ARBs (27.7%). The most common comorbidities observed included heart failure (31.1%), ischemic cardiovascular disease (31.6%), peripheral vascular disease (19.2%), and malignancy (20.7%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, overall and compared by kidney function (n = 31,676).

Similar demographic trends were demonstrated across a number of subgroups of interest. Compared to Veterans with an eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, those with an eGFR 15–24 mL/min/1.73 m2 were more likely to be ≥80 years of age (32.5% versus 16.7%) and identify as White (63.9% versus 49.2%). They also more frequently reported comorbidities including heart failure (21.9% versus 11.6%), ischemic heart disease (21.9% versus 12.0%), and stroke (7.4% versus 3.8%). In contrast, they were less likely to identify as Black (27.5% versus 40.7%) or Hispanic (6.0% versus 7.9%). Nearly half of the cohort were receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT [48.0%]) and most were male (96.9%). Among those on KRT, 39.5% were reported as Black and 9.1% identified as Hispanic. The most common comorbid condition among those receiving KRT included heart failure (45.2%), ischemic heart disease (46.2%), stroke (17.5%), peripheral vascular disease (30.1%), and malignancy (29.8%). Significant differences were observed in all comparisons (p < 0.001), with the exception of sex (p = 0.018). Additional characteristics and comorbid conditions at baseline are shown in Table 1 and in Supplementary Table S1.

Unadjusted analyses demonstrated higher observed hazard ratios (HR [95% CI]) for GLP-1 RA initiation among those Veterans with increased body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 (7.27 [5.93, 8.91]), hemoglobin A1c ≥ 7% (2.94 [2.67, 3.23]) and those on additional diabetes drugs, including biguanides (2.44 [2.01, 2.95]), and SGLT2 inhibitors (4.75 [3.30, 6.86]). Decreased hazards for initiation of GLP-1 RA therapy were older age (0.68 [0.53, 0.88] for ages 65–79 years; 0.29 [0.22, 0.38] for ≥80 years), history of dementia (0.71 [0.52, 0.97]), and eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (0.56 [0.50, 0.63]). Similar associations by subgroup remained across adjusted models and are reported in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2.

Table 2.

Predictors of initiation of GLP-1 RA.

Table 3 demonstrates the unadjusted mortality hazard ratios (HR [95% CI]) with initiation of GLP-1 RA in a time-dependent fashion. In total, 6.1% of the cohort initiated GLP-1 RA, and 57.7% of the cohort died over follow up. Groups most likely to receive GLP-1 RA were <65 years of age (9.7%), had higher BMI (9.1%, BMI 30–39; 14.0%, BMI ≥ 40), had hemoglobin A1c ≥ 7% (10.3%), and reported use of additional diabetes medications (biguanides, 19.3%; sulfonylureas, 9.3%; insulin, 10.4%). Initiation of GLP-1 RA was broadly associated with lower unadjusted mortality hazards across many prespecified subgroups. The lowest unadjusted mortality hazards (HR [95% CI]) were observed among females (0.25 [0.10, 0.68]), those <65 years (0.43 [0.34, 0.55]), and individuals reporting one comorbid condition (0.36 [0.23, 0.55]). Similar findings were observed among those with an eGFR 15–24 mL/min/1.73 m2, with the lowest unadjusted hazards observed in those < 65 years (0.58 [0.35, 0.97]) as well as those with a BMI < 25 (0.37 [0.17, 0.79]). The lowest unadjusted mortality hazards among those with a eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 included White (0.67 [0.48, 0.93]) and Black (0.54 [0.34, 0.85]) participants, BMI of 30–39 (0.55 [0.38, 0.80]), and use of insulin (0.6 [0.45, 0.84]). Among those receiving KRT, use of GLP-1 RA was similarly associated with lower mortality hazards across a number of subgroups. The lowest unadjusted mortality hazards were observed in those who reported <65 years of age (0.34 [0.23, 0.48]), Black race (0.34 [0.24, 0.48]), BMI of 30–39 (0.43 [0.34, 0.54]), and use of biguanide therapy (0.34 [0.18, 0.64]), and those who reported a single comorbidity (0.28 [0.14, 0.53]). Additional unadjusted mortality hazards for the prespecified subgroups are demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Unadjusted mortality hazards ratios with initiation of GLP-1 RA as a time-dependent variable in the overall population and in selected subgroups.

Table 4 presents mortality hazard ratios adjusted for age, sex, and race [Model 1: (AHR [95% CI])] with initiation of GLP-1 RA in a time-dependent fashion. Initiation of GLP-1 RA was broadly associated with lower mortality hazards across many subgroups. Groups with the lowest adjusted mortality hazards for Model 1 included those who reported age < 65 years (0.42 [0.33, 0.54]); non-White and non-Black race (0.42 [0.29, 0.61]); use of biguanide medication (0.48 [0.28, 0.79]); and one comorbid condition (0.37 [0.24, 0.57]). Similar findings were observed among those with an eGFR 15–24 mL/min/1.73 m2 not on KRT. The lowest adjusted hazards were observed in those <65 years (0.57 [0.34, 0.95]) with non-White and non-Black race (0.41 [0.20, 0.85]) and BMI < 25 (0.40 [0.20, 0.83]). The lowest adjusted hazards among those with a reported eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 not on KRT included male sex (0.74 [0.58, 0.95]), BMI of 30–39 (0.59 [0.41, 0.85]), and use of insulin therapy (0.72 [0.53, 0.97]).

Table 4.

Mortality hazards ratios adjusted for ages, sex, and race (Model 1) with initiation of GLP-1 RA as a time-dependent variable in the overall population and in selected subgroups.

Among participants receiving KRT, use of GLP-1 RA was broadly associated with lower mortality hazards. The lowest adjusted mortality hazards were observed in those reporting <65 years (0.33 [0.23, 0.47]), male sex (0.46 [0.39, 0.54]), Black race (0.38 [0.27, 0.53]), and non-White and non-Black race (0.32 [0.18, 0.58]). Additional adjusted associations are demonstrated in Table 4.

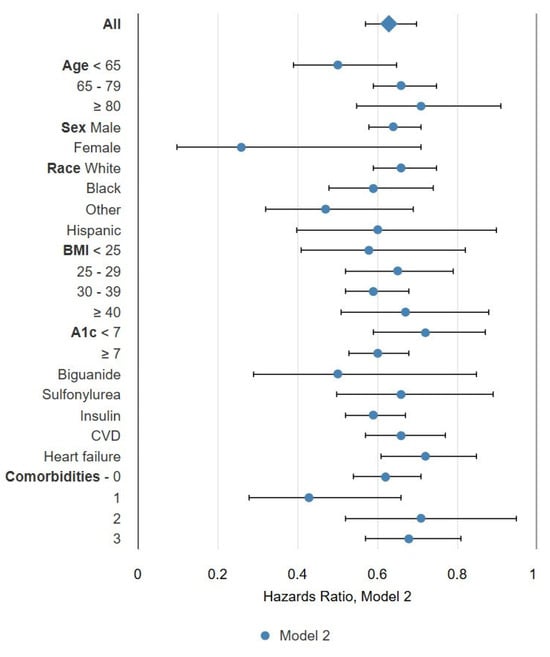

Table 5 demonstrates the mortality hazard ratios adjusted for all baseline variables [Model 2: (AHR [95% CI])] with initiation of GLP-1 RA in a time-dependent fashion. Initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonist was similarly associated with lower mortality hazards across many subgroups. Overall, groups with the lowest adjusted mortality hazards for Model 2 included female sex (0.26 [0.10, 0.71]), age < 65 years (0.50 [0.39, 0.65]), BMI < 25 (0.58 [0.41, 0.82]), and use of biguanide therapy (0.50 [0.29, 0.85]). Among those with an eGFR 15–24 mL/min/1.73 m2, the lowest adjusted hazards were observed in those reporting Black race (0.65 [0.46, 0.93]), non-White, non-Black race (0.41 [0.20, 0.87]), and BMI < 25 (0.36 [0.18, 0.74]). Among those with an eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, lower mortality hazards were observed only in those with a BMI of 30–39 (0.57 [0.39,0.83]). Among those receiving KRT and using a GLP-1 receptor agonist, the lowest mortality hazards were observed in those <65 years (0.41 [0.28, 0.59]) or ≥ 80 years (0.48 [0.23, 0.97]) and those using biguanide therapy (0.37 [0.19, 0.71]). Additional associations in the fully adjusted model are demonstrated in Table 5 and Figure 1.

Table 5.

Mortality hazard ratios adjusted for all baseline covariates (Model 2) with initiation of GLP-1 RA as a time-dependent variable in the overall population and in selected subgroups.

Figure 1.

Forest plot for mortality hazards adjusted for all baseline characteristics (Model 2).

4. Discussion

We found that initiation of GLP-1 RA was associated with longer survival in a population with T2DM and eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2. This association was present broadly among those on KRT and those with eGFR between 15 and 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 (not on KRT) but not among those with eGFR ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 who were not on KRT, as many subgroups lacked sufficient power to inform us of benefits or lack thereof.

Initial cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) of GLP-1RA, conducted to meet regulatory safety requirements for new T2DM medications, demonstrated not only safety but also cardiovascular protection [19,20]. Several CVOTs of GLP-1 RA in populations with T2DM have been reported [6,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. GLP-1 RA show promise in patients with CKD or on dialysis, and it is likely that these benefits extend beyond glycemic control, including slowing CKD progression, reducing the risk of kidney failure, and in some cases even improving kidney function [7]. Several mechanisms for the kidney benefits of GLP-1 RA have been suggested, including glucose-dependent mechanisms like lower glucose and blood pressure levels, weight loss, and lower intake of salt, protein, and phosphate, as well as glucose-independent mechanisms such as downregulation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in the kidney [8,28,29]. Beyond glycemic control and weight loss mechanisms, some evidence suggests that GLP-1 RA influence distal tubular sodium handling, resulting in a correlating blood pressure reduction and decrease in eGFR, owed to a vasodilatory effect and decrease in pro-inflammatory mediators, which may explain their reduction of proteinuria, although the magnitude of the decrease in GFR is less than that observed with other therapies [10].

A recent trial of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide demonstrated reduced risk of major kidney disease events, the primary study outcome, in a population with eGFR levels between 25 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2, as well as secondary benefits for eGFR decline, major cardiovascular events, and death from any cause [7]. If GLP-1 RA reduce the risk of kidney function loss, cardiovascular events, and death among individuals with T2DM and CKD, it seems evident that those at highest risk of these events, those with very low eGFR levels might benefit from these medications. Several small observational trials have evaluated GLP-1 RA in the KRT population and have shown general tolerance, improvement in metabolic parameters, lower risk for hypoglycemic events, and improvement in left ventricular mass index [30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

This retrospective, health-record-based study has the inherent limitations of non-experimental designs, including non-random treatment assignment, inability to exclude residual confounding, and a lack of uniform methods to characterize baseline characteristics and major study outcomes. In addition, our approach does not adequately control for confounding by indication or selection for treatment by baseline health status. The generalizability of findings between Veteran and non-Veteran populations cannot be assumed. Consistent with large, randomized trials, an intention-to-treat-like philosophy was employed; once initiated, no attempt was made to incorporate subsequent discontinuation. As such, our use of the first date on which GLP-1 RA was dispensed as a surrogate for treatment does not completely capture adherence to treatment and we did not formally assess treatment refills nor subsequent dispensed dates. Survival was the primary outcome in this study, and the mechanisms underlying survival differences in this study are unclear. Finally, financial and quality-of-life implications were not assessed in this study.

The study may have useful features that increase its relevance, including a large sample size, a real-world setting, and broad eligibility criteria. The use of time-dependent modeling attempts to control for varying baseline comorbidity and helps control for possible immortal time bias. Collectively, these findings suggest the hypothesis that GLP-1 RA may confer meaningful benefits to populations with both T2DM and advanced kidney disease, which could be tested in future randomized trials.

5. Conclusions

Initiation of GLP-1 RA was associated with improved survival in those with T2DM and eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2, a finding that remained significant with decreasing levels of kidney function, as well as among those on KRT. This association with longer survival was present among those on KRT and those not on KRT with eGFR between 15 and 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 but not among those with eGFR ≤ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 who were not on KRT.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diabetology6120161/s1: Table S1: Baseline characteristics, overall and compared by kidney function; Table S2: Hazards for initiation of GLP-1 RA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., S.P., A.I., and R.F.; data curation, S.R. and R.F.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, S.R. and A.I.; methodology, S.R., A.I., and R.F.; project administration, S.R. and A.I.; resources, S.R.; supervision, S.R., A.I., and R.F.; visualization, R.F.; writing—original draft, S.W., S.P., and R.F.; writing—review and editing, S.W., S.P., A.I., and R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Minneapolis VA Health Care System (IRB #1594650, approval date: 27 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

This retrospective study leveraged existing data stored securely. No consent was required for the study and hence there is no consent form.

Data Availability Statement

Given its federal nature coupled with both privacy and security concerns, the datasets presented in this article are not readily available. Any requests for access can be directed to OITOpenData@va.gov.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the content of this work.

References

- Abasheva, D.; Ortiz, A.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B. GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with chronic kidney disease and either overweight or obesity. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17 (Suppl. S2), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators; Afshin, A.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Reitsma, M.B.; Sur, P.; Estep, K.; Lee, A.; Marczak, L.; Mokdad, A.H.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrington, W.G.; Smith, M.; Bankhead, C.; Matsushita, K.; Stevens, S.; Holt, T.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Coresh, J.; Woodward, M. Body-mass index and risk of advanced chronic kidney disease: Prospective analyses from a primary care cohort of 1.4 million adults in England. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prospective Studies Collaboration; Whitlock, G.; Lewington, S.; Sherliker, P.; Clarke, R.; Emberson, J.; Halsey, J.; Qizilbash, N.; Collins, R.; Peto, R. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: Collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009, 373, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Chow, S.L.; Mathew, R.O.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.-P.; et al. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1636–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Tuttle, K.R.; Rossing, P.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.; Bakris, G.; Baeres, F.M.; Idorn, T.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Lausvig, N.L.; et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskiet, M.H.A.; Tonneijck, L.; Smits, M.M.; Van Baar, M.J.B.; Kramer, M.H.H.; Hoorn, E.J.; Joles, J.A.; Van Raalte, D.H. GLP-1 and the kidney: From physiology to pharmacology and outcomes in diabetes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Rodbard, H.W.; Tuttle, K.R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetic kidney disease: A review of their kidney and heart protection. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 14, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, I.H.; Khunti, K.; Sadusky, T.; Tuttle, K.R.; Neumiller, J.J.; Rhee, C.M.; Rosas, S.E.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G. Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 3075–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI). Available online: www.research.va.gov/programs/vinci/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Greene, T.; Stevens, L.A.; Zhang, Y.L.; Hendriksen, S.; Kusek, J.W.; Van Lente, F.; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Wang, D.; Sang, Y.; Crews, D.C.; Doria, A.; Estrella, M.M.; Froissart, M.; et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C-Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, C. Ascertaining Veterans’ Vital Status: Data Sources for Mortality Ascertainment and Cause of Death. Database & Methods Cyberseminar Series. 2017. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fhsrd.research.va.gov%2Ffor_researchers%2Fcyber_seminars%2Fcatalog%2Ftranscripts%2F3783.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Reinikainen, J.; Adeleke, K.A.; Pieterse, M.E.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.M. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highcharts. Highcharts Documentation. Available online: https://www.highcharts.com/docs/index (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- 2020 FDA Guidance for Diabetes Drug Development: Cardiorenal Populations and Outcomes: Lessons Learned and Future Directions—American College of Cardiology. Available online: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2021/09/10/13/46/2020-fda-guidance-for-diabetes-drug-development (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Federal Register: Guidance for Industry on Diabetes Mellitus-Evaluating Cardiovascular Risk in New Antidiabetic Therapies to Treat Type 2 Diabetes; Availability. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2008/12/19/E8-30086/guidance-for-industry-on-diabetes-mellitus-evaluating-cardiovascular-risk-in-new-antidiabetic (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Claggett, B.; Diaz, R.; Dickstein, K.; Gerstein, H.C.; Køber, L.V.; Lawson, F.C.; Ping, L.; Wei, X.; Lewis, E.F.; et al. Lixisenatide in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Acute Coronary Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, R.R.; Bethel, M.A.; Mentz, R.J.; Thompson, V.P.; Lokhnygina, Y.; Buse, J.B.; Chan, J.C.; Choi, J.; Gustavson, S.M.; Iqbal, N.; et al. Effects of Once-Weekly Exenatide on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.F.; Green, J.B.; Janmohamed, S.; D‘Agostino, R.B.; Granger, C.B.; Jones, N.P.; Leiter, L.A.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Sigmon, K.N.; Somerville, M.C.; et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Donsmark, M.; Dungan, K.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Franco, D.R.; Jeppesen, O.K.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Pedersen, S.D.; et al. Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Sattar, N.; Rosenstock, J.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Pratley, R.; Lopes, R.D.; Lam, C.S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Heenan, L.; Del Prato, S.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Efpeglenatide in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, S.L.; Rørth, R.; Jhund, P.S.; Docherty, K.F.; Sattar, N.; Preiss, D.; Køber, L.; Petrie, M.C.; McMurray, J.J.V. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIsaac, R.J.; Jerums, G.; Ekinci, E.I. Glycemic Control as Primary Prevention for Diabetic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.K.; Ernst, J.; Khan, T.; Reichert, S.; Khan, Q.; LaPier, H.; Chiu, M.; Stranges, S.; Sahi, G.; Castrillon-Ramirez, F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in end-staged kidney disease and kidney transplantation: A narrative review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idorn, T.; Knop, F.K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Jensen, T.; Resuli, M.; Hansen, P.M.; Christensen, K.B.; Holst, J.J.; Hornum, M.; Feldt-Rasmussen, B. Safety and Efficacy of Liraglutide in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and End-Stage Renal Disease: An Investigator-Initiated, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Randomized Trial. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomholt, T.; Idorn, T.; Knop, F.K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Ranjan, A.G.; Resuli, M.; Hansen, P.M.; Borg, R.; Persson, F.; Feldt-Rasmussen, B.; et al. The Glycemic Effect of Liraglutide Evaluated by Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Persons with Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Dialysis. Nephron 2021, 145, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terawaki, Y.; Nomiyama, T.; Akehi, Y.; Takenoshita, H.; Nagaishi, R.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Murase, K.; Nagasako, H.; Hamanoue, N.; Sugimoto, K.; et al. The efficacy of incretin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing hemodialysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2013, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, T.; Ozeki, A.; Asai, K.; Saka, M.; Hobo, A.; Furuta, S. Liraglutide Improves Glycemic and Blood Pressure Control and Ameliorates Progression of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Peritoneal Dialysis. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2015, 19, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonston, D.; Mulder, H.; Lydon, E.; Chiswell, K.; Lampron, Z.; Shay, C.; Marsolo, K.; Shah, R.C.; Jones, W.S.; Gordon, H.; et al. Kidney and Cardiovascular Effectiveness of SGLT2 Inhibitors vs GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.W.; See, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Wu, V.C. Mortality and cardiovascular events in diabetes mellitus patients at dialysis initiation treated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).