Abstract

This paper presents the design and evaluation of a fluorescent probe based on fluorescein hydrazide for the selective detection of hypochlorite (ClO−), bromide (Br−), and iodide (I−) ions in solution. The starting chemosensor, fluorescein hydrazide, is suitable for detecting hypochlorite anions in solution, as observed for the first time. The Br− and I− ions could be discovered after activating the probe with hypochlorite. Upon interaction with ClO− ions, the proposed probe exhibits a significant increase in fluorescence emission, a sharp rise in absorbance, and a distinct color change, which is attributed to the conversion from the spirolactam closed form to the open form of the fluorescein ring. ClO− and Br− ions added together were found to brominate the probe in an acetonitrile–water mixture, resulting in a pronounced bathochromic shift in both absorption and emission spectra. Notably, the combination of ClO− and I− was more effective in cleaving the spirolactam ring than hypochlorite alone. Quantum chemical calculations were used to understand the detection mechanism of Br and I ions in a probe–hypochlorite mixture. The probe demonstrated exceptional selectivity and rapid response towards the target analytes, with detection limits determined to be 2.61 μM for ClO−, 66 nM for Br−, and 13 nM for I−. Furthermore, it successfully monitored fluctuations in ClO−, Br−, and I− concentrations within complex systems, highlighting its potential application in environmental and biological monitoring.

1. Introduction

The detection and identification of anions in various samples is a critical area of research due to their profound implications in biological, industrial, and environmental contexts. Anions play pivotal roles in numerous processes, making their accurate analysis essential for ensuring safety and compliance across multiple sectors. A variety of analytical techniques have been developed for this purpose, including atomic emission spectroscopy [1], atomic absorption spectroscopy [2], electrochemistry [3], chromatography [4], UV–Vis spectroscopy [5], and spectrofluorimetry [6]. Among these methods, spectrofluorimetry shines due to its high sensitivity, straightforward sample preparation, rapid response time, and applicability in field settings [7,8]. Developing new fluorescent probes capable of detecting multiple ions is a top priority in the field of analytical chemistry [9,10,11,12].

Hypochlorites are widely used in both industrial and household applications, serving such functions as whitening fabrics, lightening hair, and stain removal [13,14,15]. Moreover, their efficacy as disinfectants, deodorizers and oxidizers is well-documented [16,17,18]. However, exposure to high concentrations of sodium hypochlorite can pose significant health risks, including skin irritation and gastrointestinal distress upon ingestion [19]. Similarly, bromides find utility in diverse fields such as petroleum processing, photography, and infrared spectroscopy [20,21], with compounds like KBr and NaBr being recognized for their sedative and anticonvulsant properties in veterinary medicine [22]. Iodides also play crucial roles in various applications, including analytical chemistry (iodometry) [23], medicinal uses [24], and the production of dyes and pharmaceuticals [25,26]. Given the widespread application of hypochlorites, bromides, and iodides, developing a single probe capable of monitoring these anions is of significant interest.

The development of selective fluorescent probes for inorganic anions represents a dynamic frontier in chemical biology and environmental science. Among the most versatile platforms are probes constructed from small organic molecules, where the fluorescence output is modulated by specific anion recognition. Common dye scaffolds such as rhodamine [27], fluorescein [28], coumarin [29], BODIPY [30], triphenylamine [31] hydroxybenzoquinoline [32] and naphthalene [33] are particularly valued as signaling fragments due to their excellent photophysical properties and synthetic versatility, which facilitate the rational design of “turn-on” or ratiometric sensors for targets like hypochlorite, bromide, and iodide.

Fluorescein, a xanthene dye known for its excellent photostability, solubility, and high quantum yield, has emerged as a promising candidate for fluorescent probes. Its applications in analytical chemistry include serving as an absorption indicator in silver nitrate titrations and determining pH and bromide concentrations [34,35]. Additionally, spirocyclic derivatives of fluorescein dyes have been recognized as valuable sensing platforms due to the fluorescence changes associated with their ring-opening processes. Fluorescein hydrazide is a probe for detecting copper(II) [36,37] and mercury(II) [38] ions in solution. However, to the best of our knowledge, it has not been used as a probe for anion detection. In addition, fluorescein hydrazide is frequently employed as a precursor for synthesizing hydrazones, which are utilized for detecting various analytes in solution [39,40]. Notably, fluorescein hydrazones have demonstrated effectiveness as fluorescent probes for detecting a range of ions, including Zn2+ and ClO− [41], Cd2+ [42], Hg2+ [43,44,45,46,47], Cu2+ [48], and Ni2+ and Al3+ [49] ions.

In this study, we aim to expand the set of highly sensitive and selective probes utilizing fluorescein molecules. We synthesized a fluorescein hydrazide that functions as a fluorescence probe for the selective detection of hypochlorite ions in an acetonitrile/Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 7.4) at a 9:1 v/v ratio. The combination of this probe with ClO− demonstrates high sensitivity and selectivity for recognizing bromide and iodide ions in solution. Furthermore, we employed this compound to accurately quantify ClO−, Br−, and I− levels in river water samples. To support our findings, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to elucidate the structural characteristics of the synthesized probe.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

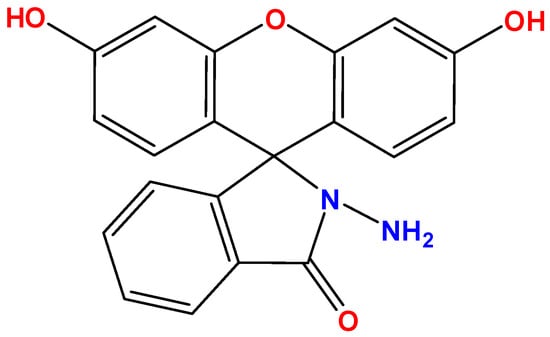

Fluorescein hydrazide was obtained following the procedure described in our previous paper [37]. The molecular structure of probe 1 is shown in Figure 1. The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum along with the 1H and 13C NMR spectra for probe 1 are shown in Figures S1–S3. Other chemicals were purchased from various commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Acros Organics (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), BLD Pharm (Shanghai, China), and Reakhim (Moscow, Russia)). F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, CN−, NCS−, ClO−, ClO3−, ClO4−, NO3−, H2PO4−, HSO4−, SO32−, HCO3− and OH− were taken as sodium and potassium salts and used without purification. Salt solutions were prepared using bidistilled water (κ = 3.6 μS/cm, pH = 6.6). Acetonitrile (EKOS-1, Moscow, Russia, wt. > 99.9%) was also used as purchased.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of probe 1.

2.2. Instruments

UV–Vis spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) over the wavelength range of 240 to 800 nm. CH3CN/Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (9:1 v/v), was used as the blank solution. Fluorescence spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu RF6000 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at the excitation wavelength λex = 444 nm. The widths of the excitation and emission slits were adjusted to 10 nm. An external thermostat (LO&P, St. Petersburg, Russia) was employed to ensure that the temperature remained at 298.2 ± 0.1 K during the UV–Vis and fluorescence experiments. Mass spectrometry data were collected using a Shimadzu Biotech Axima Confidence system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.3. DFT Study

Quantum chemical calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 09 program [50] in the framework of density functional theory (DFT/B3LYP [51,52], 6-311G(d,p) basis set [53]). To simulate electronic absorption spectra, time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations were performed using the B3LYP method. The solvent effect of acetonitrile was considered by employing the polarizable continuum model (PCM) in all calculations [54]. Molecular models were visualized using the Chemcraft program [55].

3. Results

3.1. Selectivity of Probe 1 to ClO− and Other Anions in Solution

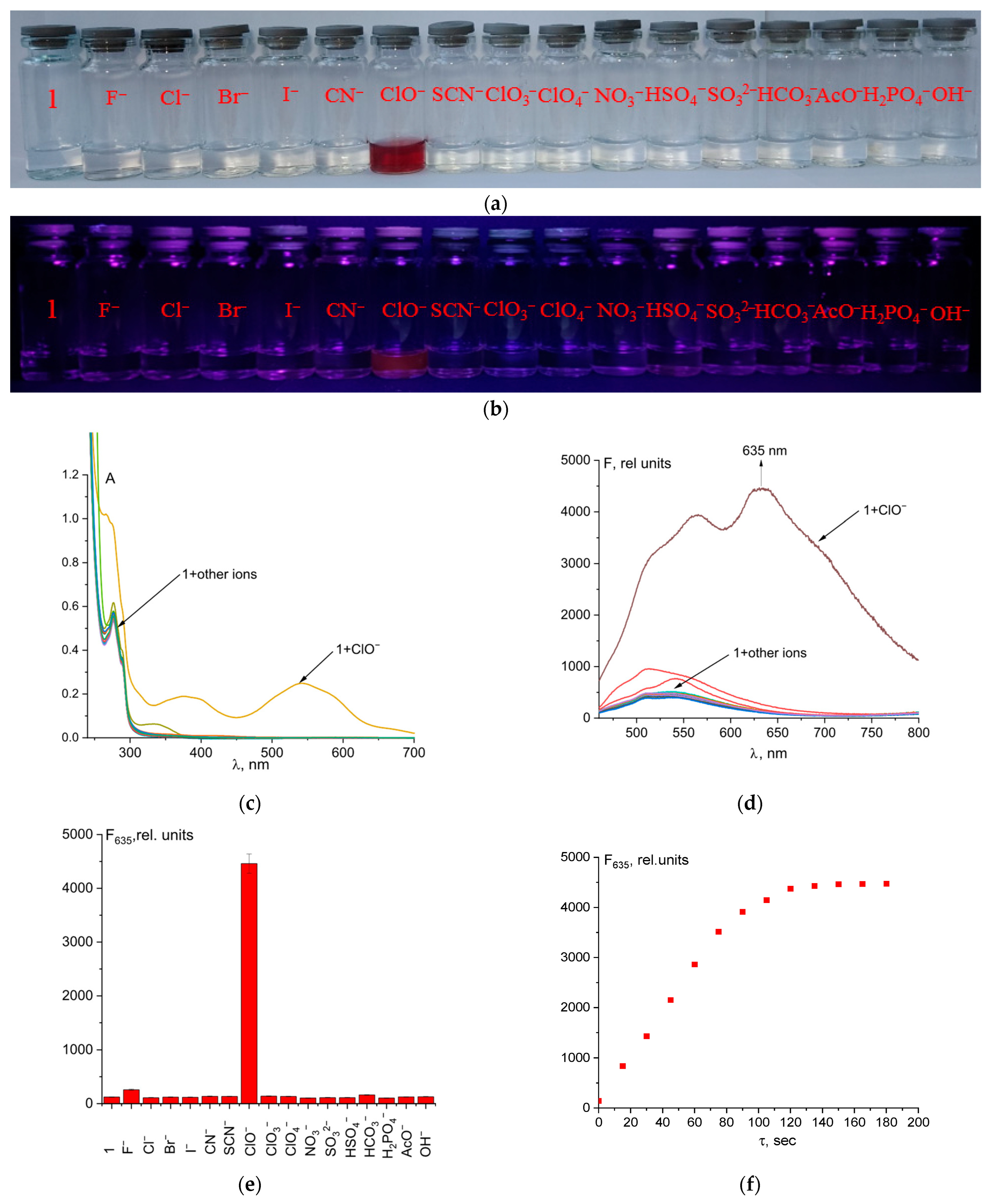

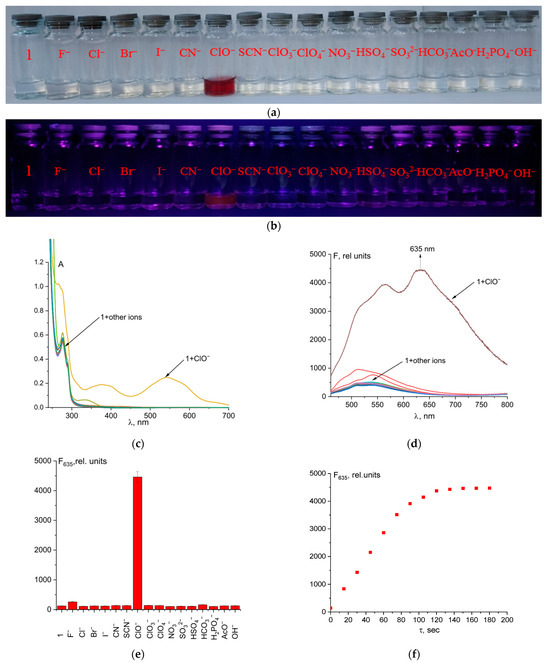

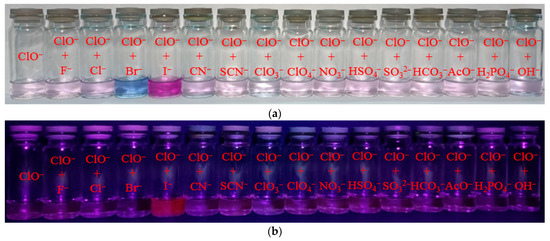

UV–Vis and fluorescence experiments were conducted with a 50 µM solution of probe 1 in a mixture of CH3CN and 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (9:1 v/v), along with an 5 equivalent amount of different anions (Figure 2c,d). The absence of color of probe 1 solution is explained by the closed spirolactam cycle. The studied chemosensor showed an absorption maximum at 279 nm with a small shoulder at 290 nm. Hypochlorite is the only anion among the tested ones that caused a change in the color and fluorescence of the solution when added to probe 1 (Figure 2a,b). ClO− caused opening of the spirolactam ring of fluorescein hydrazide, which resulted in a broad absorption band with a maximum at 540 nm. Orange-red fluorescence with a maximum at 635 nm also turned on. This allows for selective fluorimetric determining of hypochlorite in a solution (Figure 2). In addition, we tested the selectivity of probe 1 for cysteine, glutathione, HS−, H2O2, N3−, and PO43−. The addition of these analytes did not cause an increase in fluorescence intensity, which suggests a high selectivity of the probe for hypochlorite ions (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

Solution colors (a) and naked-eye visible fluorescence at λex = 365 nm (b), UV–Vis spectra (c), and fluorescence spectra (d,e), of probe 1 and its mixtures with different anions. Time dependence of fluorescence intensity at 635 nm of probe 1 + ClO− (5 eq.) (f).

The reaction between the probe and hypochlorite was fast, which is a significant advantage of this method (Figure 2f). Quantum yield increased from 0.2% to 4.3% after probe 1 reaction with ClO− ions.

The effect of pH in the range of 3 to 9 on the detection of hypochlorite ions was investigated (Figure S5). The optimal spectral response for determining ClO− was achieved under acidic conditions (pH 3–5.5). It is important to note that a strong and analytically useful reaction persisted at a physiological pH value of 7.4. However, the analytical response decreased significantly at pH 9. We propose that the mechanism of oxidation–hydrolysis of the hydrazo group in probe 1, which leads to the opening of the spirolactam ring, is most effective under acidic conditions. This explains the observed pH dependence. It should also be kept in mind that acid–base equilibria involving the chemosensor can also affect the photophysical properties of the reaction products.

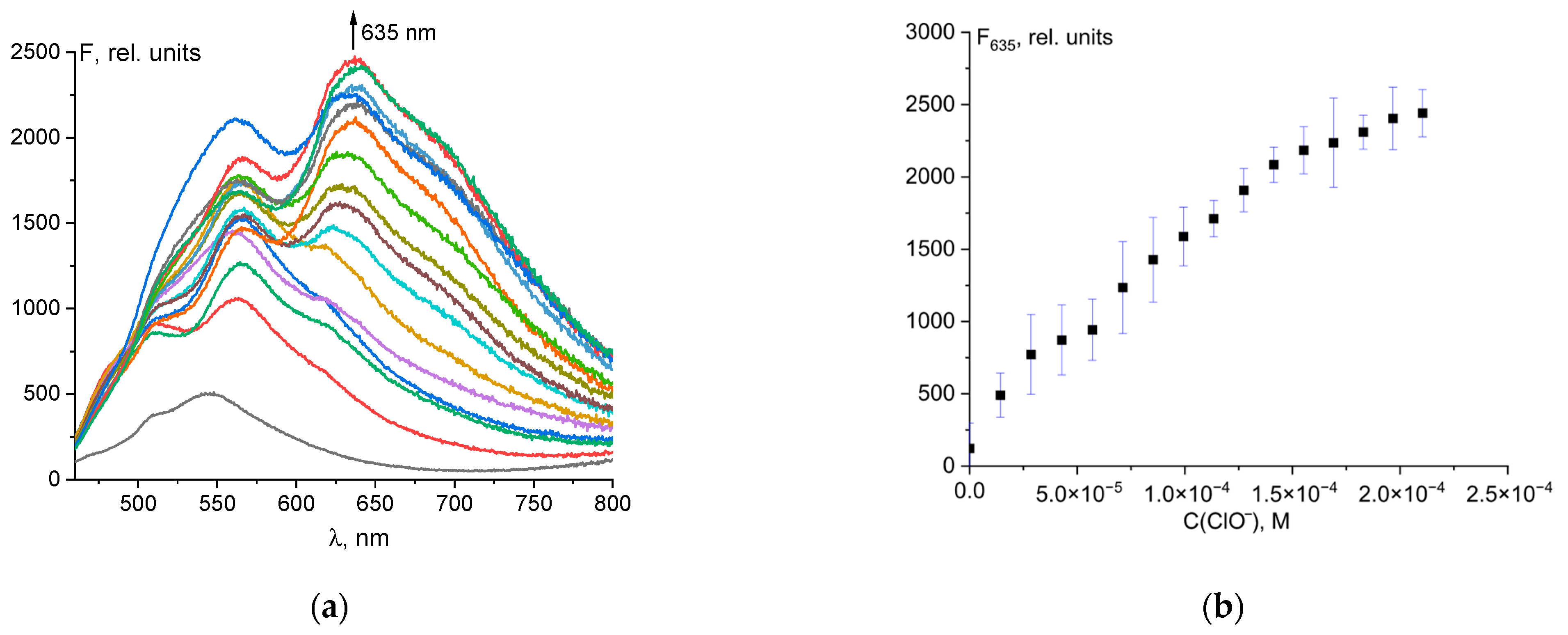

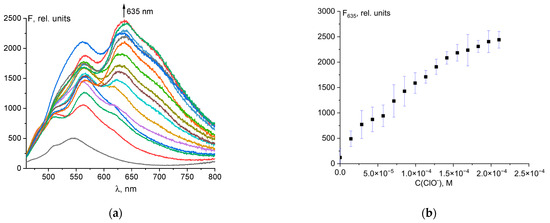

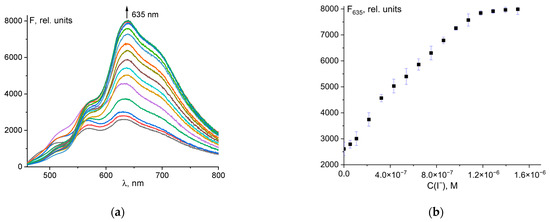

Probe 1 had weak fluorescence with a maximum at 546 nm. When hypochlorite was added to the solution, a bathochromic shift of fluorescence from 546 to 635 nm was observed, with significant fluorescence enhancement (Figure 3a). The dependence of fluorescence intensity at 635 nm on total ClO− concentration was linear up to 120 µM (Figure 3b). The linear regression was F635 = 1.301·107·C0(ClO−) + 273, R2 = 0.984 (Figure S7).

Figure 3.

Changes in the fluorescence spectrum of probe 1 (50 μM) upon addition of ClO− ions (a). Dependence of probe fluorescence intensity at 635 nm on total hypochlorite concentration (b).

This allows the quantitative determination of hypochlorite ions. The detection limit (LOD) was determined by the rule of 3σ using the formula LOD = 3σ/k, where σ is the standard deviation of the solution blank (10 measurements), and k is the slope of the calibration curve. The detection limit was 2.61 µM (Figure S6). The obtained LOD value was compared with values from the literature for similar probes (Table S1). The table shows that probe 1 is one of the most sensitive. In addition, probe 1 has a simple formula, can be easily synthesized, and is of low cost as the starting compounds (fluorescein and hydrazine) are the products of a multi-tonnage industry.

Based on established literature for similar hydrazide-based probes, the mechanism involves hypochlorite-mediated oxidation–hydrolysis of the hydrazide functional group [56,57,58,59]. In this process, hypochlorite oxidizes the exocyclic hydrazide group of probe 1, which triggers the opening of the spirolactam ring and culminates in the release of the highly fluorescent fluorescein molecule. This transformation accounts for the significant fluorescence enhancement observed. To confirm the mechanism of interaction between probe 1 and hypochlorite ions, we conducted a 1H NMR experiment in DMSO-d6 (Figure S6). The spectral changes clearly demonstrate that the addition of hypochlorite ions led to the opening of the spirolactam ring of the fluorescein hydrazide moiety, consistent with an oxidation–hydrolysis reaction pathway. Upon addition of hypochlorite to probe 1, the signals corresponding to the xanthene fragment protons shifted significantly from 6.5 ppm to 5.9 ppm. This shift indicates the opening of the spirolactam ring in probe 1. Notably, the signals from the benzene ring also underwent a slight upfield shift, suggesting a redistribution of electron density upon conversion of probe 1 to the reaction product. The absence of a signal at 4.38 ppm following hypochlorite addition confirms that the hydrazo group is not present in the reaction product. This mechanism of analyte recognition is typical of xanthene dyes [6,39].

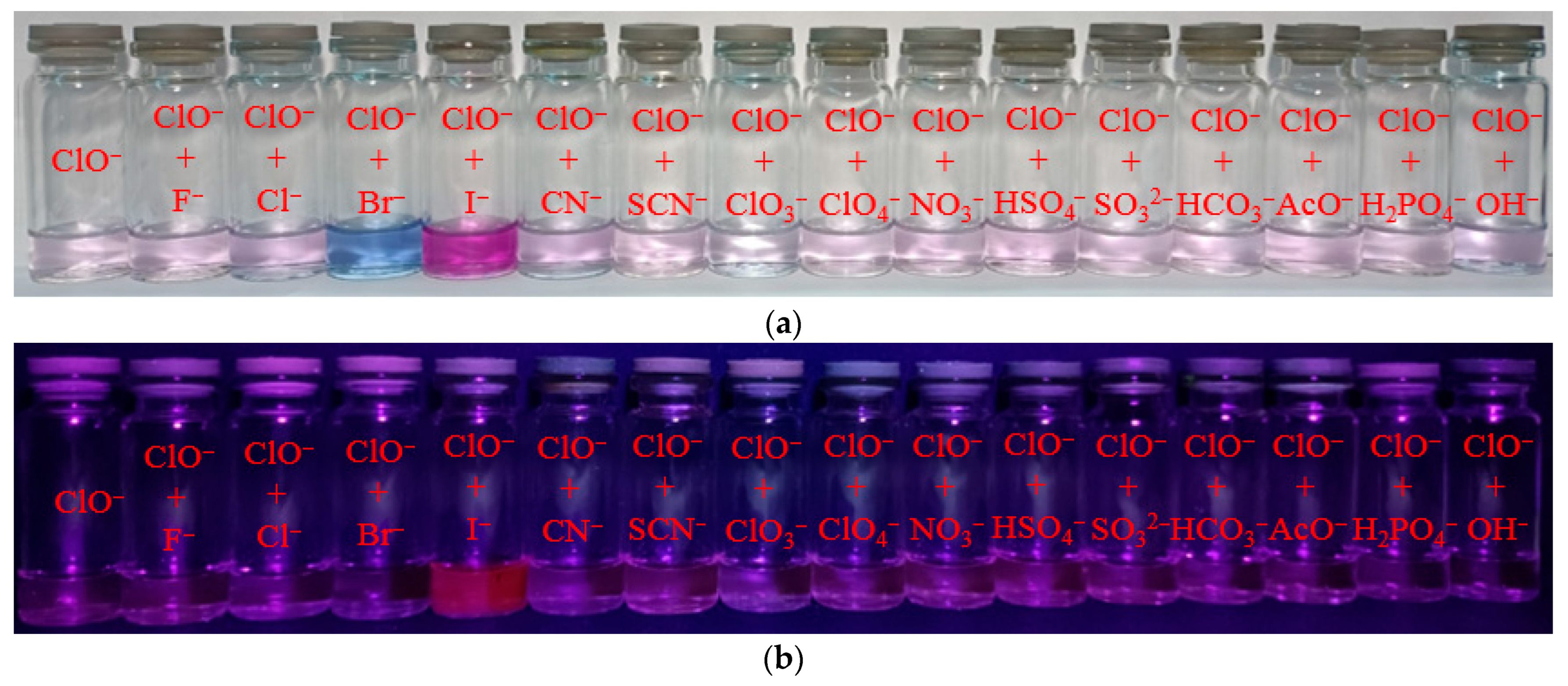

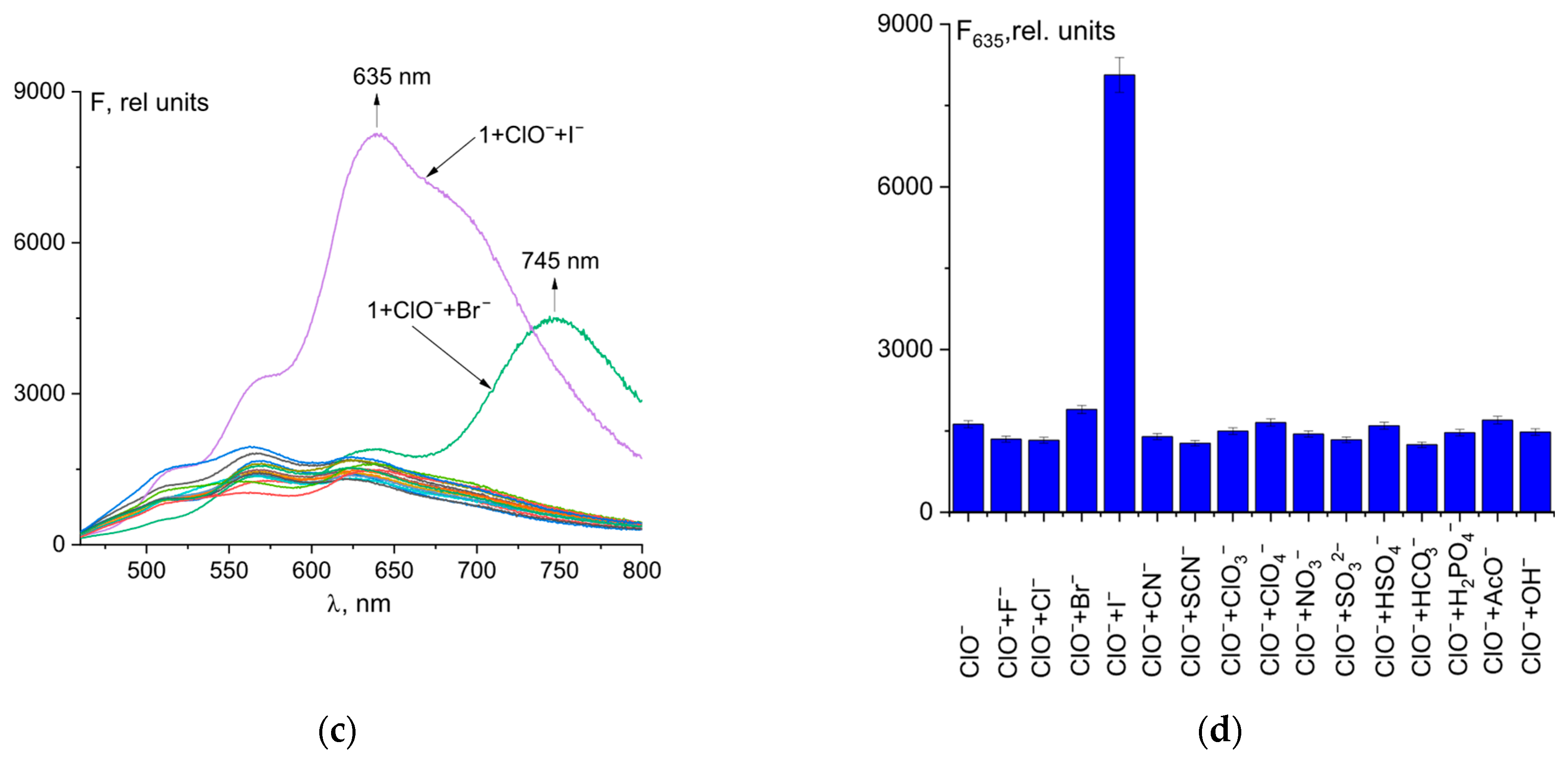

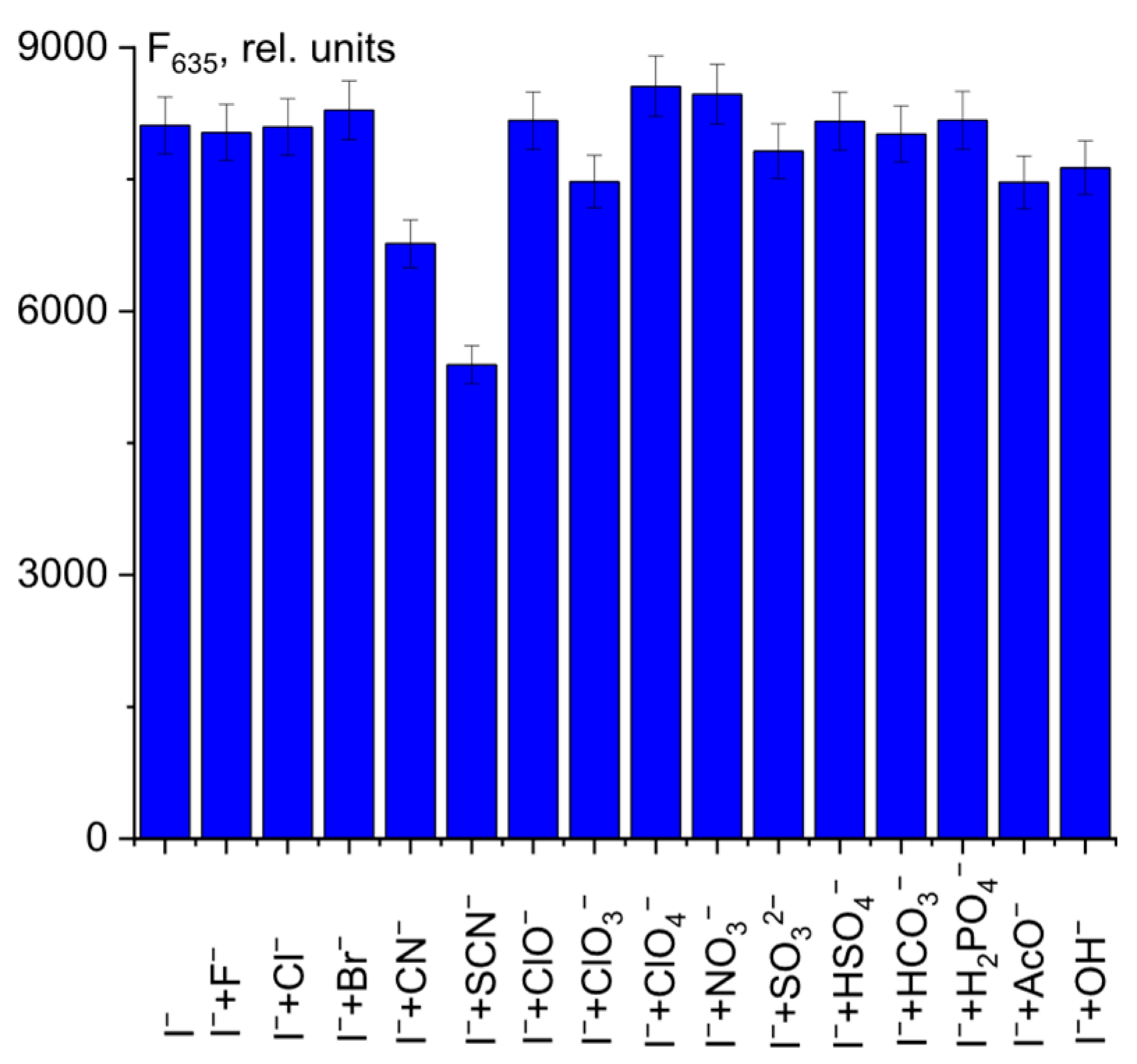

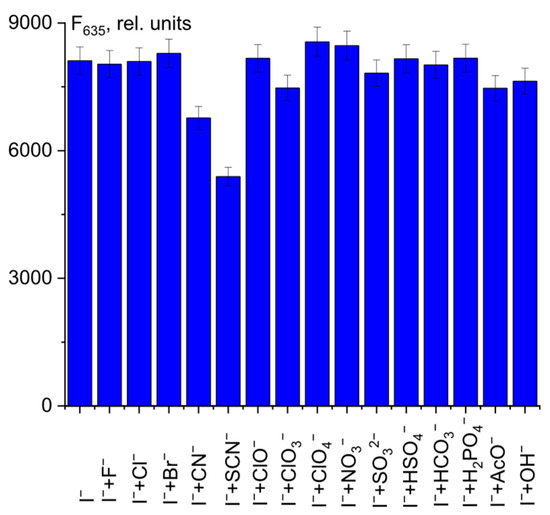

Probes designed for anion detection should have high specificity towards the target anion compared to other ions. As a result, the fluorescence reactions of probe 1 at a concentration of 50 µM towards ClO− (1 eq.) ions and various other anions (5 eq.) were tested in buffered acetonitrile. Solution colors and naked-eye visible fluorescence at λex = 365 nm are shown in Figure 4a,b. Most anions, except I−, did not affect the qualitative and quantitative determination of hypochlorite in the solution (Figure 4c,d). Upon addition of Br− ions, a change in the color of the solution from pale violet to blue, along with a shift in fluorescence to the near-infrared region (with a maximum at 745 nm), was observed. On the other hand, when iodide ions were added, the color changed to bright violet and a significant fluorescence turn-on at 635 nm was observed. Therefore, it can be used to determine bromide and iodide ions in a solution.

Figure 4.

Solution colors (a) and naked-eye visible fluorescence at λex = 365 nm (b); fluorescence spectral changes for mixture of probe 1 (50 µM) and ClO− with different anions (c). Fluorescence intensity at λem = 635 nm of 1 + ClO− + anion mixtures (d).

In addition, we conducted comprehensive competition experiments by incubating probe 1 with hypochlorite in the presence of various competing analytes, including Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Cr3+, cysteine, glutathione, HS−, H2O2, N3−, and PO43− (Figure S8). The results confirm that probe 1 exhibits good selectivity against Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, cysteine, glutathione, HS−, H2O2, N3−, and PO43−, as their presence induced no significant change in the fluorescence signal for hypochlorite. However, we did observe an enhancement of fluorescence in the presence of Cu2+, Fe3+, and Cr3+. We hypothesize that this amplification could be due to the oxidative properties of these metal ions and their well-known ability to generate reactive oxygen species, which might promote further oxidation of the probe or catalyze the reaction with hypochlorite. To accurately measure the concentration of ClO− in mixtures containing Cu2+, Fe3+, and Cr3+, the interfering cations must be masked. For example, Cu2+ can be masked with an ammonia solution, which converts it into a stable ammine complex. Similarly, Fe3+ and Cr3+ can be masked with 5-sulfosalicylic acid, which forms strong complexes with trivalent cations [60].

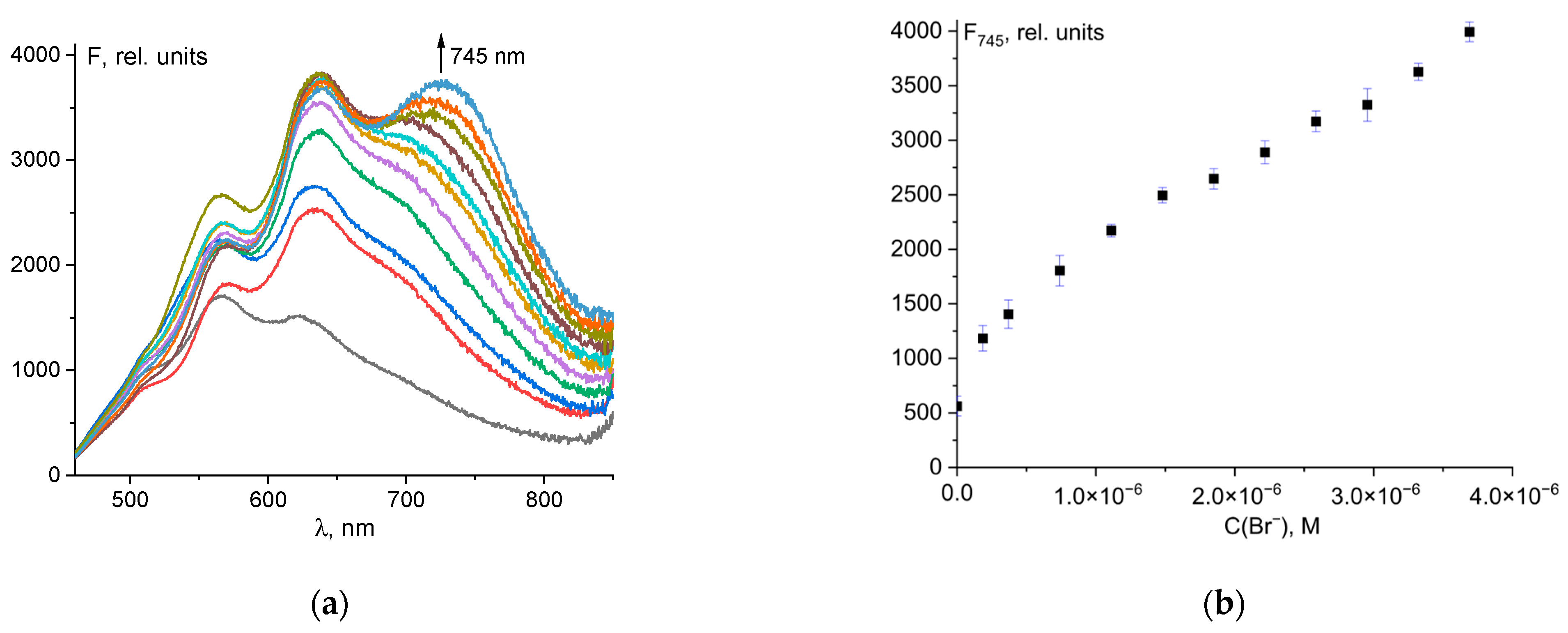

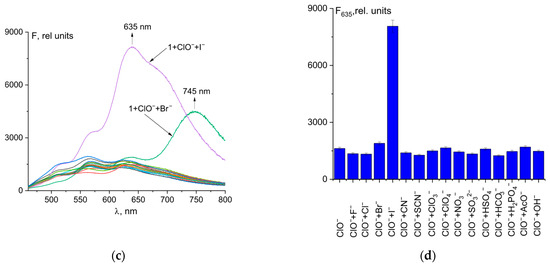

3.2. Determination of Bromide Ions Using Probe 1

As discussed in Section 3.1, the addition of bromide ions to the probe 1–hypochlorite ion mixture results in enhanced fluorescence at 745 nm. Even a small amount of bromide ions (0.05 µM) in solution gave a strong spectral response (Figure 5a). The detection limit was determined by fluorescence titration of a mixture of probe 1 and hypochlorite ions with Br− (0 to 4 μM). The fluorescence emission of 1 at 745 nm increased gradually with increasing Br− concentration. The linear equation F745 = 7.516·108·C0(Br-) + 1210 shows a good linear relationship (R2 = 0.986 in the range of 0.5 to 4 μM (Figure 5b). The limit of detection (LOD) of probe 1 was calculated to be 66 nM (Figure S9). Thus, probe 1 has excellent sensitivity and can be used for the quantification of bromide ions. Compared to previously reported probes for Br− (Table S2), 1 has a low LOD and emission in the near-infrared region (important for biological cellular studies), making 1 a promising probe for the detection of bromide ions. The LOD value of 66 nM is lower than the acceptable limit for drinking water as recommended by the WHO [61].

Figure 5.

Fluorescence spectral changes for mixture of probe 1 and ClO− upon addition of Br− ions (a). Fluorescence intensity at λem = 745 nm of the total concentration of Br− ions (b).

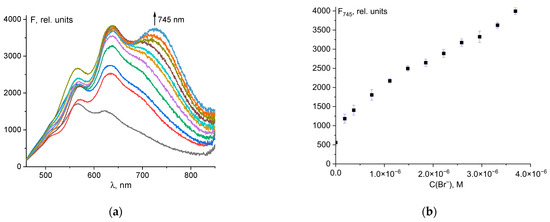

Probes designed for analyte detection should be highly specific to the desired anion compared to other ions. As can be seen in Figure 6, other anions, except iodide (Figure 6a), had no effect on the determination of Br− ions using the probe 1–hypochlorite mixture. In the case of I− ions, despite good fluorescence intensity at 745 nm (Figure 6b), there was significant fluorescence turn-on at 635 nm, which is characteristic when iodide is added to a 1–ClO− mixture (Figure 6a and Figure 4c). The color of the solution was violet, not blue. Thus, I− ions interfere while detecting Br− ions using probe 1.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence spectral changes for mixture of probe 1 (50 µM) and ClO− (50 µM) and Br− (4 µM) with different anions (20 µM) (a). Fluorescence intensity at λem = 745 nm of 1 + ClO− + Br− + anion mixtures (b).

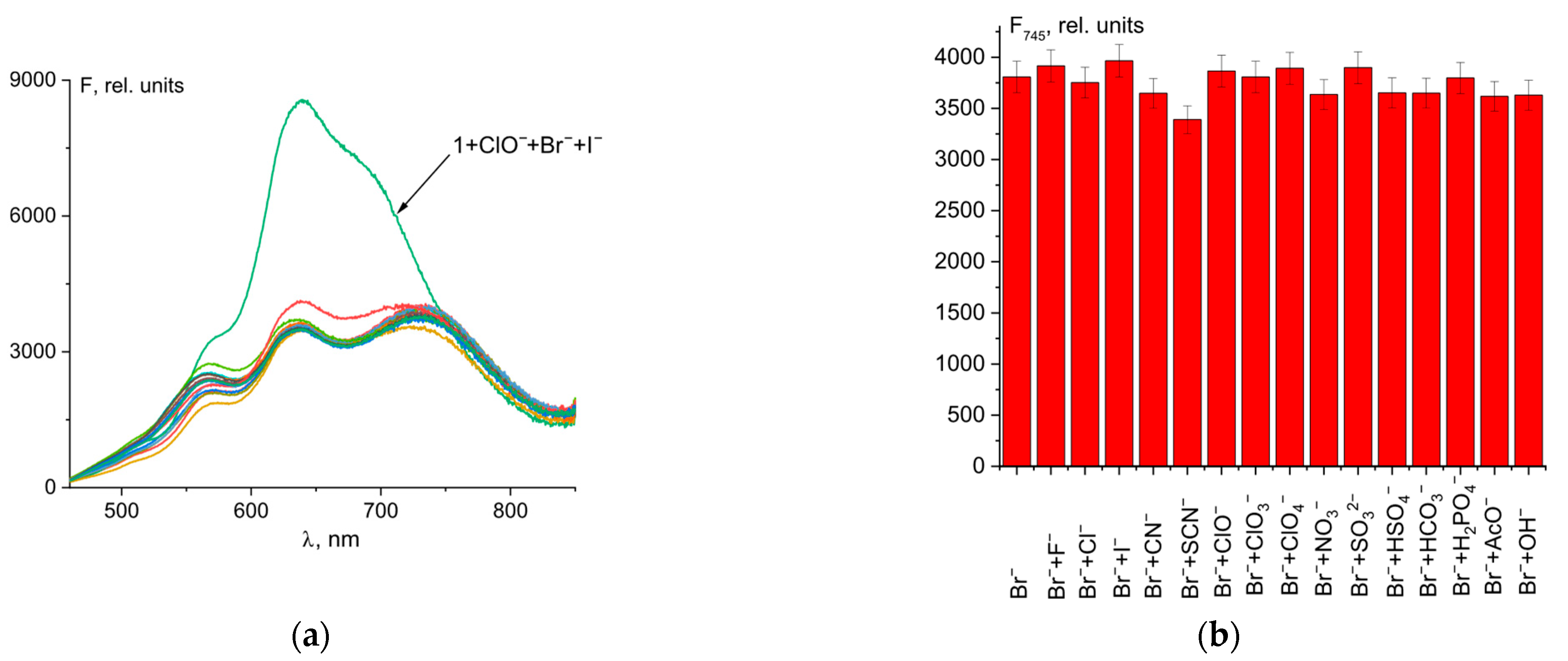

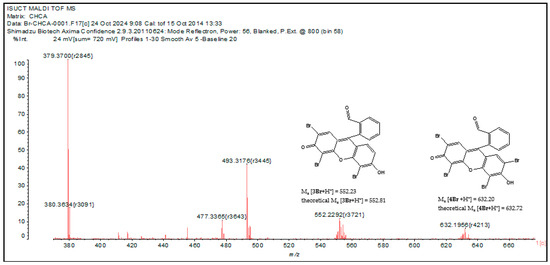

Fluorescein contains two hydroxy groups that facilitate electrophilic substitution reactions in the aromatic nucleus. The bromination reaction with liquid bromine results in the formation of eosin at room temperature [62]. In solution, when hypochlorite and bromide are present simultaneously, the reaction ClO− + Br− ↔ BrO− +Cl− is observed [63]. The reaction of hypobromite with fluorescein results in the formation of mono-, di-, and tribromofluorescein derivatives, as well as a tetrabromine compound called eosin. In addition, bromine derivatives of fluorescein have been found to have similar extinction coefficients [64]. The products formed depend on the molar ratio of the initial reagents. The mass spectrum of the mixture 1 + ClO− + Br− contains peaks of different bromination products of fluorescein hydrazide (Figure 7). The isotopic splitting characteristic of bromine (as Br consists of two isotopes, 79Br (50.6%) and 81Br (49.4%)) is observed. We found peaks of tetra- and tribromine derivatives, the difference between their masses equal to the atomic mass of bromine. The possible structures of the bromination products of probe 1 are shown in Figure 7. This fact confirms that the mechanism of bromide ion recognition is based on the bromination of probe 1 in the hypochlorite medium, which significantly affects the electron absorption and emission spectra of the indicator.

Figure 7.

MALDI TOF mass spectrum of mixture 1 + ClO− + Br− in MeCN.

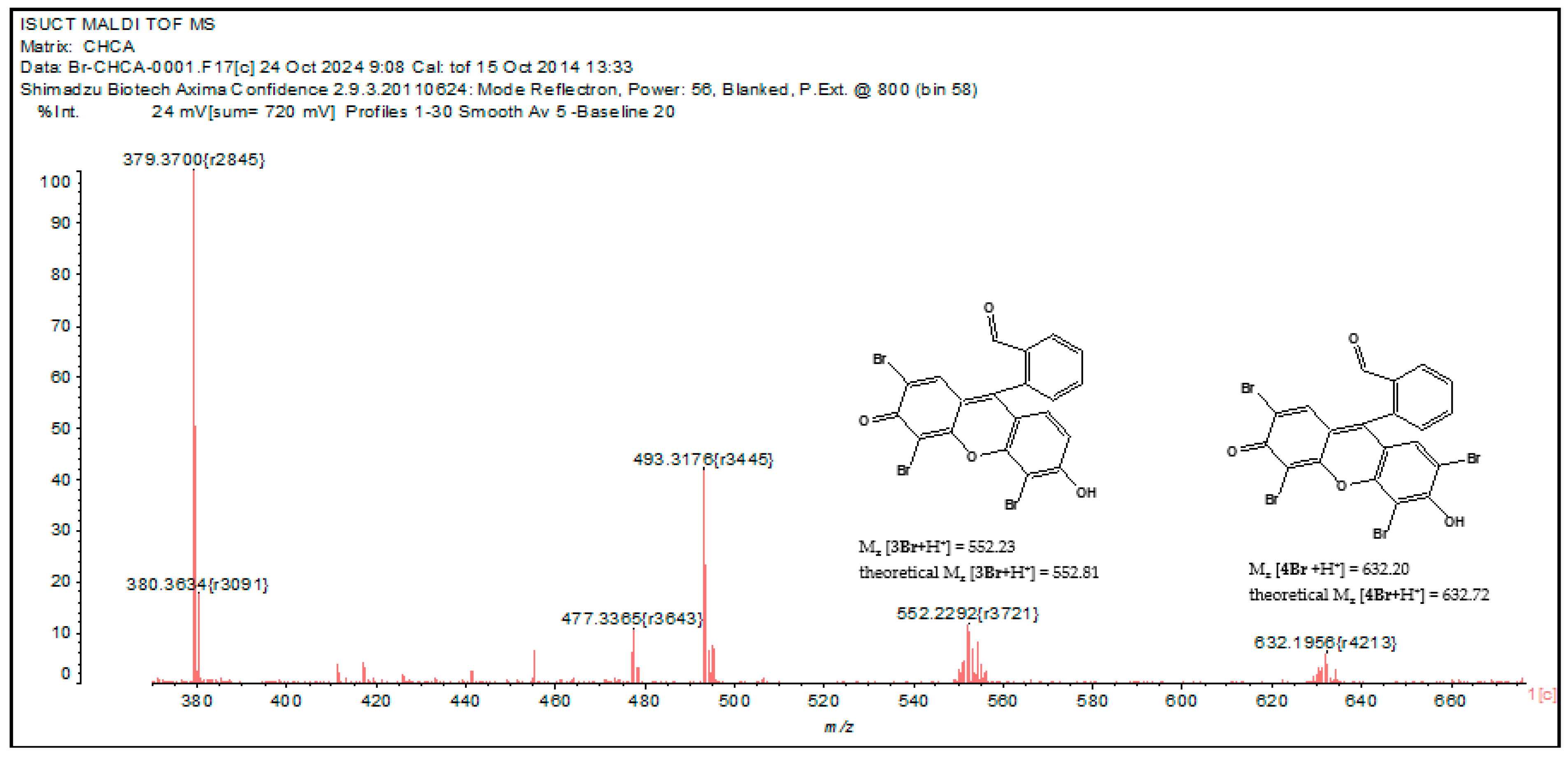

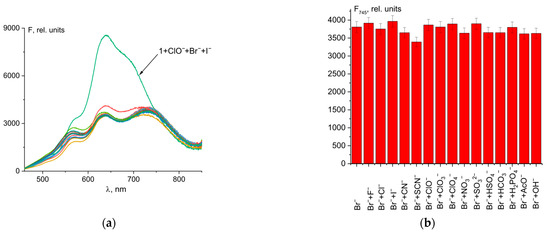

3.3. Determination of Iodide Ions Using Probe 1

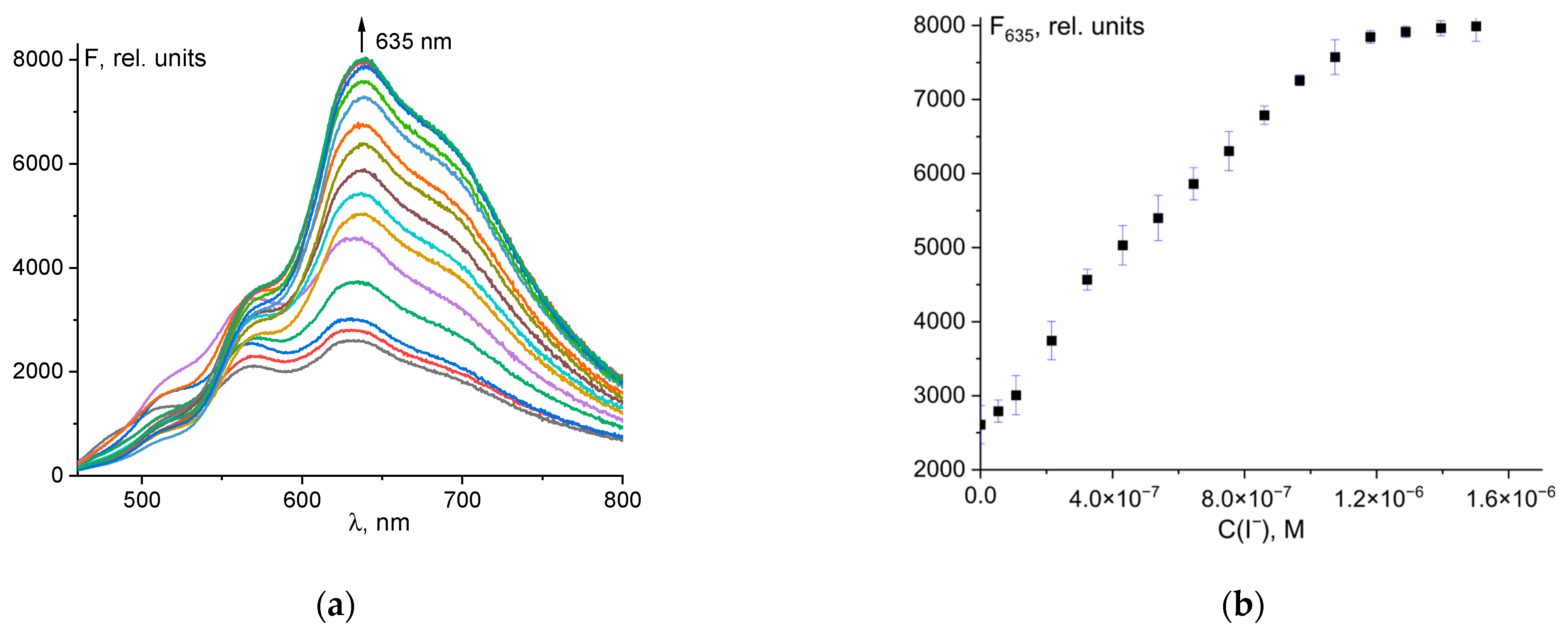

As shown in Figure 4c, the mixture of probe 1 and ClO− ions was also able to detect iodide ions selectively. The experimental result showed that only in the presence of I− was a significant increase in fluorescence at 635 nm observed. The dependence of fluorescence intensity on total iodide ion concentration is shown in Figure 8a. The fluorescence emission of 1 at 635 nm increased linearly with increasing I− concentration from 0 to 1 µM (Figure 8b). The mixture of probe 1 and ClO− is very sensitive to iodide ions. An excellent spectral response was observed even with the addition of a 50 nM solution of I−. The detection limit of 13 nM was calculated using the 3σ rule (Figure S10). The equation is F635 = 4.884·109·C0(I−) + 2678, R2 = 0.989. This is one of the most sensitive methods used to detect iodide ions (see Table S3).

Figure 8.

Fluorescence spectral changes for mixture of probe 1 and ClO− upon addition of I− ions (a). Fluorescence intensity at λem = 635 nm of the total concentration of I− ions (b).

Finally, to further investigate the probe response to I− in a complex medium, we conducted a competition experiment. As shown in Figure 9, the presence of interfering anions had little effect on the recognition of I− by probe 1.

Figure 9.

Fluorescence intensity at λem = 635 nm of 1 + ClO− + I− + anion mixtures.

Only CN− and SCN− ions showed a slight decrease in fluorescence intensity at 635 nm. This fact should be taken into account in the quantitative determination of I− ions in complex systems.

When iodide ions were added, no bathochromic shift was observed in the fluorescence spectrum of the 1 + ClO− probe mixture as with bromide ions (Figure 8). There was only a sharp increase in fluorescence intensity at 635 nm. We hypothesize that the addition of iodide ions would not iodize probe 1 as in the case of bromide ions. The reactivity of molecular iodine in electrophilic substitution reactions in the aromatic nucleus is insignificant. The reaction requires elevated temperature and the presence of an oxidizing agent (usually nitric acid) to produce the electrophilic agent. The exchange reaction ClO− + I− → IO− + Cl− can form hypoiodite when hypochlorite reacts with iodide ions in acetonitrile. Hypoiodite is an unstable ion and a strong oxidizing agent, stronger than hypochlorite [65,66]. It is also likely that molecular iodine, a oxidizing agent, would be released during this reaction [67]. Thus, in the presence of iodide ions, as in the case of hypochlorite, the opening of the spirolactam ring of fluorescein hydrazide is observed. However, since the IO− or elemental iodine generated during the reaction of probe 1 with the ClO− + I− mixture are stronger oxidizing agents than ClO−, the equilibrium between closed and open spirolactam forms is shifted towards the latter. Thus, the detection limit for iodide ions was much lower (0.013 µM vs. 2.61 µM).

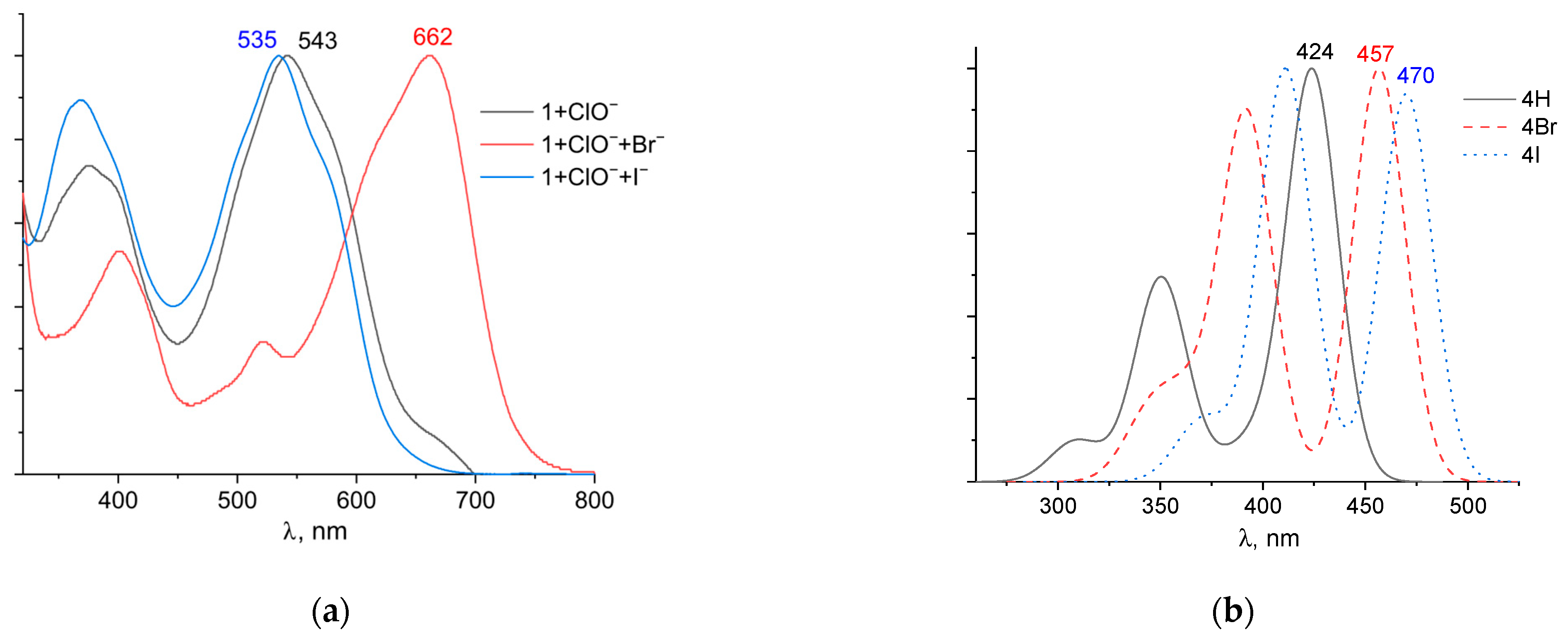

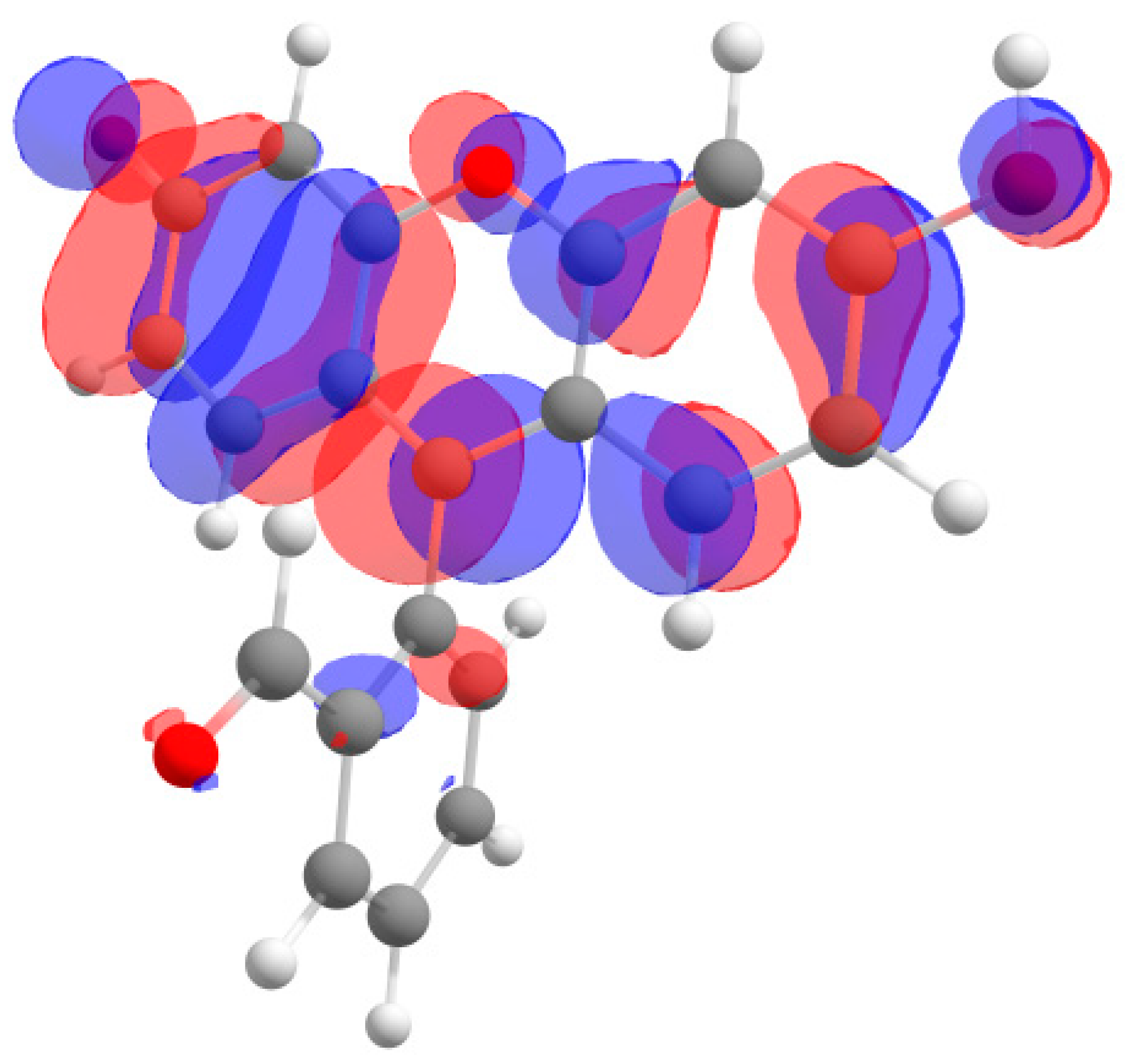

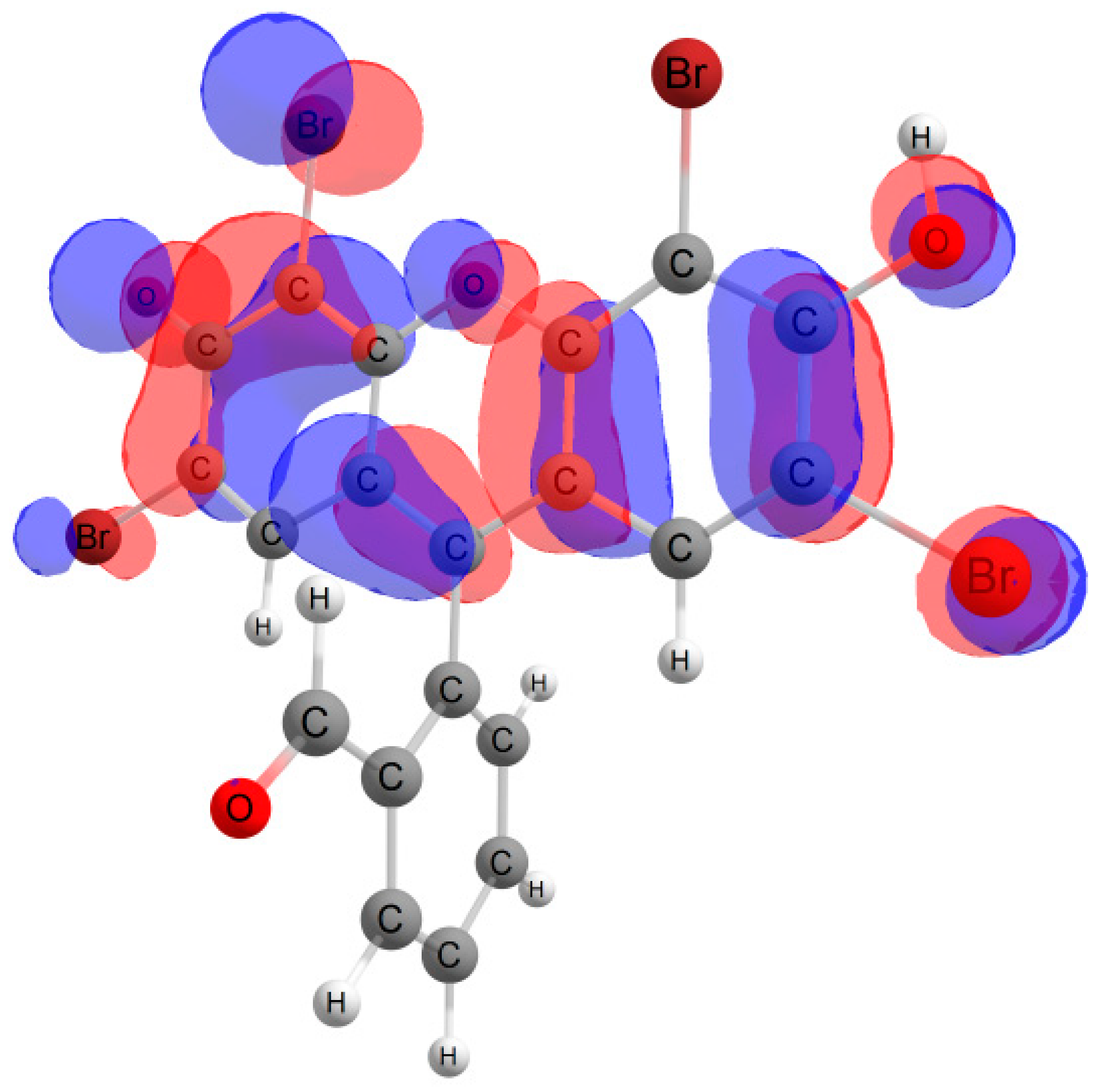

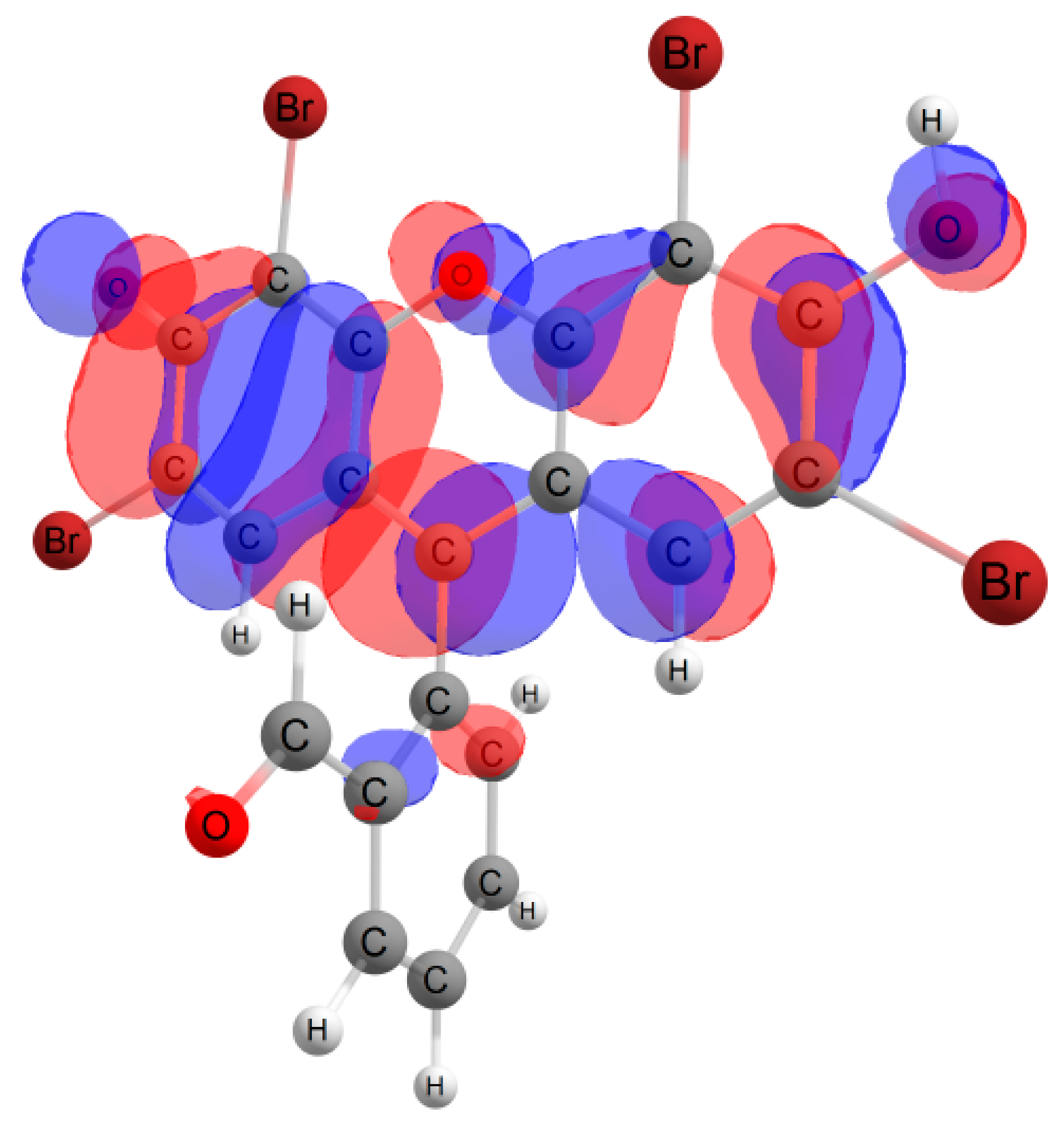

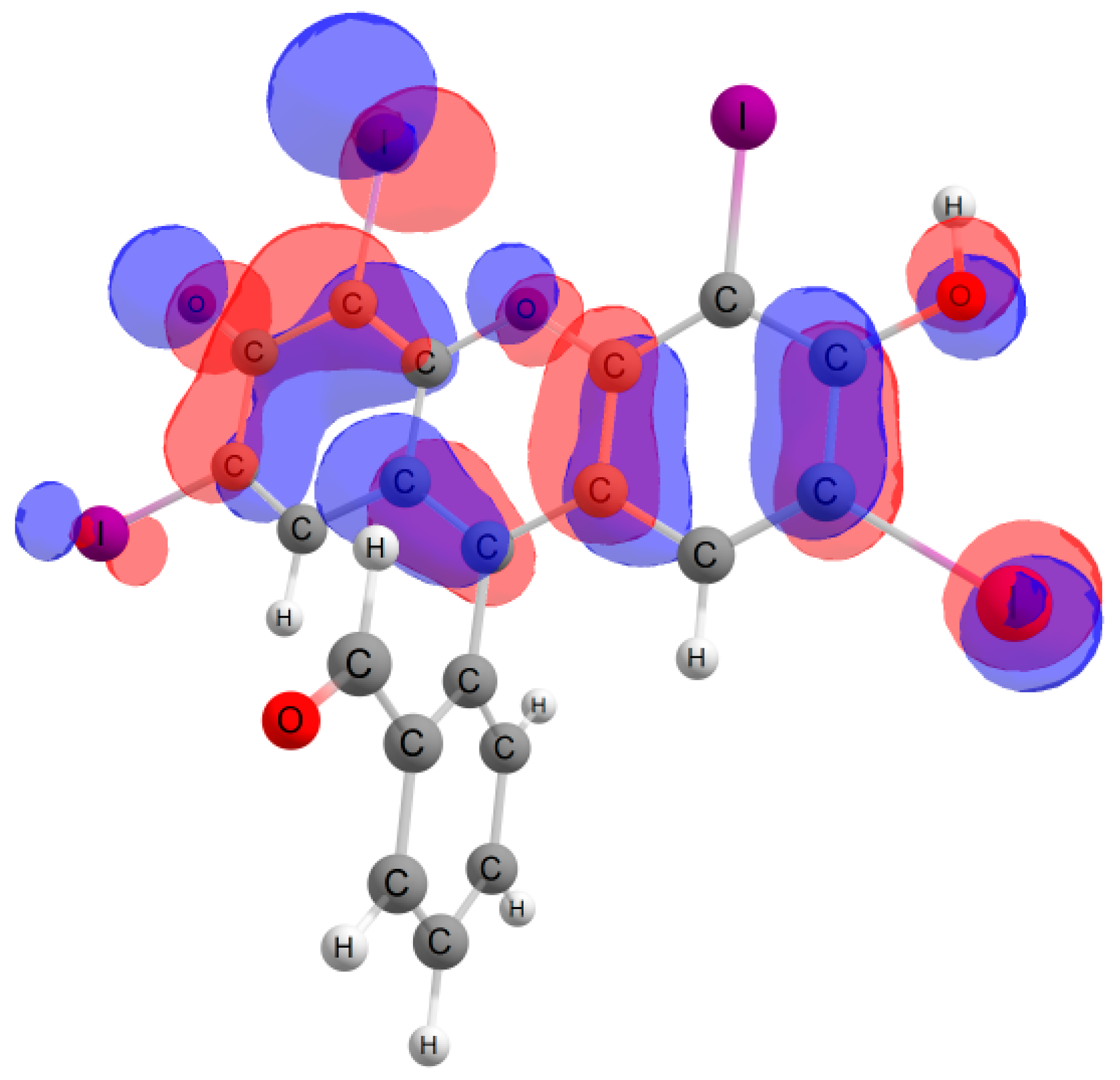

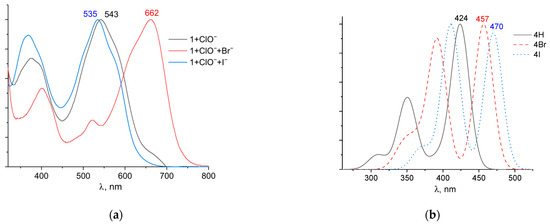

To confirm this mechanism, we performed quantum chemical modeling of the alleged bromination and iodination products of probe 1. The structure was based on the mass spectrum of the mixture 1 + ClO− + Br− with four bromine atoms. The structures were also obtained by replacing the bromine atoms with hydrogen and iodine atoms. The optimized structures are shown in Figure S11. Experimental normalized UV–Vis spectra and theoretical TDDFT spectra are shown in Figure 10. The addition of bromine atoms resulted in a significant shift of the absorption band to longer wavelengths, from 543 to 662 nm (Figure 10a). The small peak at ~540 nm may be due to unreacted probe 1. By contrast, the addition of iodide ions caused a slight hypochromic shift from 543 to 535 nm. The shapes of the UV–Vis spectra were similar, indicating that the chromophore structure is preserved after the addition of the ClO− mixture with Br− and I− ions. The TD DFT spectra provide a good description of the structure of the experimental UV–Vis spectra, although they are shifted significantly to the blue region. In our case, quantum-chemical calculations overestimate the energy of transitions between ground and excited states. It is worth noting that when bromine and iodine atoms were introduced into the xanthene group, there was a stronger bathochromic shift in the long-wavelength absorption band.

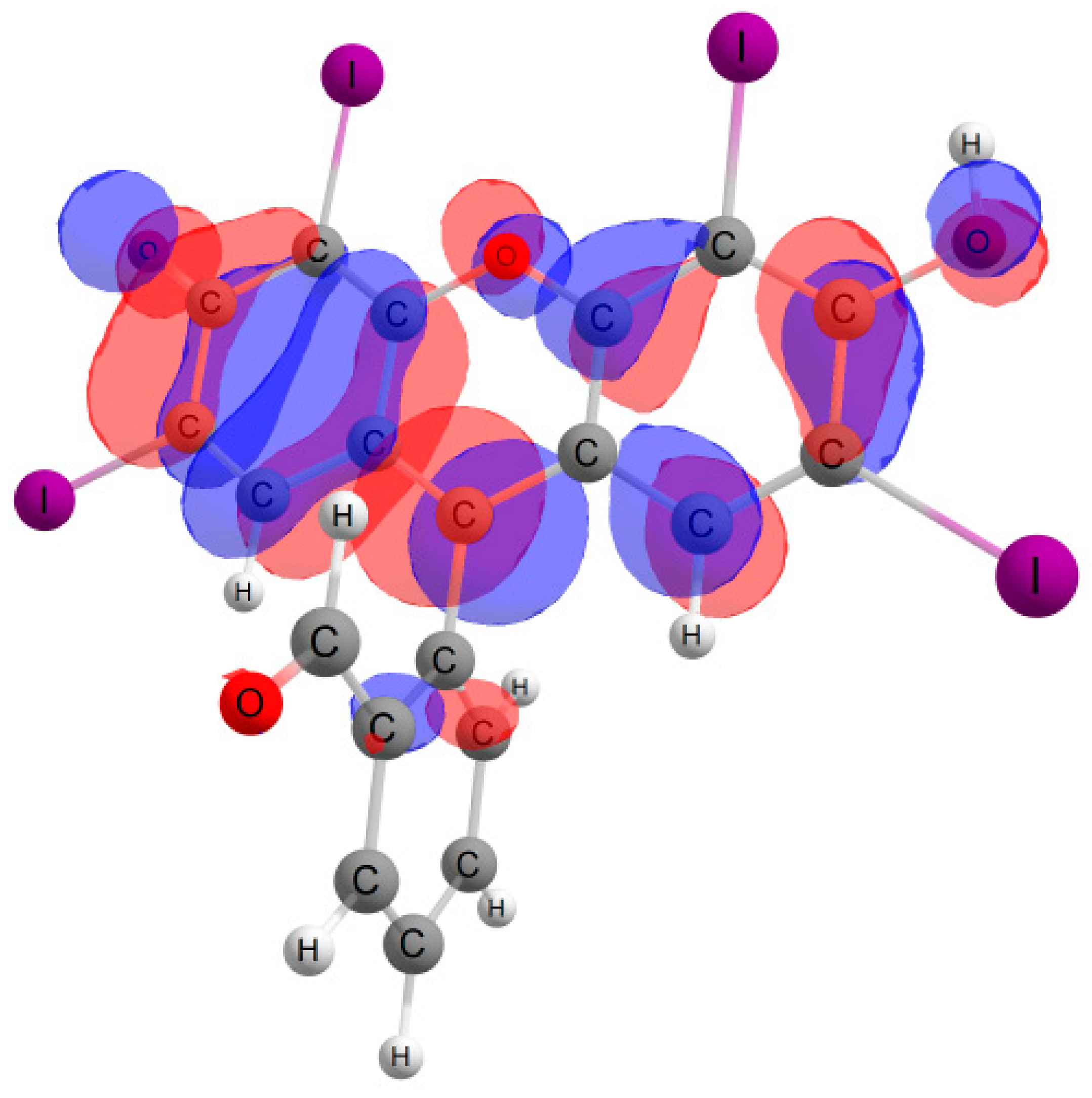

Figure 10.

Normalized UV–Vis (a) and TDDFT spectra (b) of possible reaction products of probe 1 in the determination of ClO−, Br−, and I− ions.

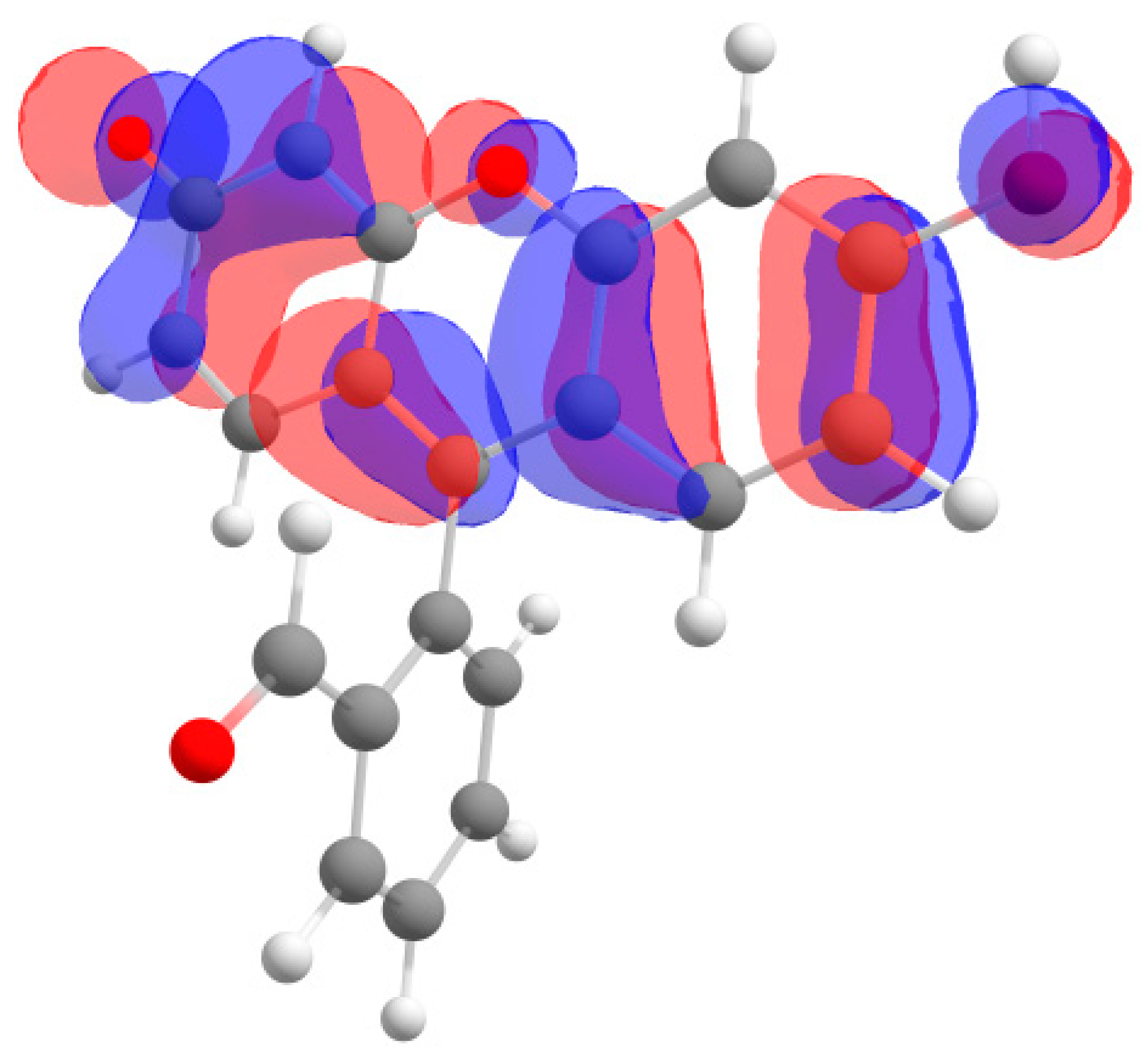

Furthermore, in the case of the iodine derivative, the red shift was greater than in the bromine derivative. The long-wavelength absorption band was mainly caused by transitions between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), with a contribution of ~90%. The HOMO and LUMO orbitals for all structures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frontier orbitals for the potential product structures of probe 1.

These orbitals are mainly localized on the xanthene fragment. In halogenated derivatives, the orbitals of the bromine and iodine atoms contribute to the formation of the HOMO orbital. The bathochromic shift that occurs when these halogens are introduced is due to the positive mesomeric and negative inductive effects of the bromine and iodine atoms on the fluorescein hydrazide chromophore. These calculations confirm the oxidation mechanism by the ClO− + I− mixture, rather than iodination, of probe 1.

3.4. Practical Application

To evaluate the practicality of the developed probe 1, we tested natural water samples collected from local rivers to detect ClO−, Br− and I− ions. The water samples were collected from the Talka River in Ivanovo, Russia. The sampling location was determined by the coordinates 56°86′56.5″ N, 40°77′39.5″ E. The sample was filtered through paper filters to remove any suspended solids and then treated with a standard solution containing various concentrations of analytes.

The results of detecting ClO−, Br− and I− ions in river water are presented in Table 2. These results indicate that probe 1 is effective in ClO−, Br− and I− ions in real-world samples. All experiments were conducted three times. The recovery rate of ClO−, Br− and I− ions from the solutions ranged from 94 to 113%.

Table 2.

Determination of ClO−, Br− and I− ions in river water sample.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, a fluorescein hydrazide-based fluorescent probe was designed for the detection of ClO−, Br− and I− ions in solution. Upon interaction with ClO− ions, there was a notable increase in fluorescence emission, a sharp rise in absorbance, and a color change resulting from the conversion of the spirolactam closed form to the open form of the fluorescein ring. It was found that a mixture of ClO− and Br− brominates probe 1 in an acetonitrile–water mixture, causing a significant bathochromic shift in absorption and emission bands in the spectra. A mixture of ClO− and I− is much more effective in breaking the spirolactam ring of fluorescein hydrazide than hypochlorite, strongly shifting the equilibrium between closed and open species towards the latter. The mechanism of analyte detection was confirmed by mass spectrometry and quantum chemical calculations. Probe 1 exhibited excellent selectivity and a quick response to analytes. The detection limit for ClO− was 2.61 μM, for Br− 66 nM and for I− 13 nM. Additionally, it was possible to observe the variations in ClO−, Br− and I− concentrations within complex systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/analytica6040058/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR spectra of probe 1; Figure S2: 13C NMR spectra of probe 1; Figure S3: MALDI TOF mass spectrum of probe 1; Figure S4: Fluorescence spectra of probe 1 with different analytes; Figure S5: The fluorescence intensity of probe 1 at 635 nm in the presence of ClO− (1 eq.) at different pH; Figure S6: Limit of detection of ClO−; Figure S8: Limit of detection of Br−; Figure S9: Limit of detection of I−; Figure S10: The optimized structures for the potential product structures of probe 1; Figure S11: The optimized structures for the potential product structures of probe 1; Table S1: Structures of selected fluorescence probes for ClO− ions in the literature; Figure S7: Fluorescence spectral changes for mixture of probe 1 (50 µM) and ClO− with different analytes; Table S2: Structures of selected fluorescence probes for Br− ions in the literature; Table S3: Structures of selected fluorescence probes for I− ions in the literature; Table S4: Calculated composition of the lowest main excited states and corresponding oscillator strengths for the potential product structures of probe 1; Table S5: Cartesian coordinates of all optimized structures with IR spectra. The following papers are cited in the supplementary file [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.Z.; methodology, M.N.Z. and G.A.G.; validation, M.N.Z., G.A.N., V.S.O. and G.A.G.; investigation, M.N.Z., G.A.N., V.S.O. and G.A.G.; data curation, M.N.Z. and G.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.N.Z. and G.A.G.; visualization, G.A.N. and V.S.O.; funding acquisition, M.N.Z. and G.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was carried out within the framework of State Assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education and the Russian Federation (project FZZW-2023-0008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Equipment from the Centers of Joint Use of Ivanovo State University of Chemistry and Technology (ISUCT) was used to perform spectrofluorimetric studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MALDI TOF | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy |

References

- Harwood, J.J.; Wen, S. Analysis of Organic and Inorganic Selenium Anions by Ion Chromatography-Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy. J. Chromatogr. A 1997, 788, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienzo, M.; Capasso, R. Analysis of Metal Cations and Inorganic Anions in Olive Oil Mill Waste Waters by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy and Ion Chromatography. Detection of Metals Bound Mainly to the Organic Polymeric Fraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboubakr, H.; Brisset, H.; Siri, O.; Raimundo, J.-M. Highly Specific and Reversible Fluoride Sensor Based on an Organic Semiconductor. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 9968–9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz, B. Advances in the Determination of Inorganic Anions by Ion Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 881, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeian, K.; Khanmohammadi, H. Naked-Eye Detection of Biologically Important Anions by a New Chromogenic Azo-Azomethine Sensor. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 133, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Fan, K.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zu, F.; Xu, J.; Li, X. Fluorescein Applications as Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of Analytes. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 97, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, X.; Tong, W.; Leng, Y.; Xiong, Y. Recent Advances in Colorimetry/Fluorimetry-Based Dual-Modal Sensing Technologies. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 190, 113386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, C.; Ji, M. Development and Application of Several Fluorescent Probes in near Infrared Region. Dyes Pigments 2021, 190, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Mageswari, N.; Sankar, D.; Vinoth Kumar, G.G. Fluorescence Chemosensor for Fluoride Ion Using Quinoline-Derived Probe: Molecular Logic Gate Application. Mater. Lett. 2022, 327, 133040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanasundaram, D.; Vinoth Kumar, G.G.; Kumar, S.K.; Maddiboyina, B.; Raja, R.P.; Rajesh, J.; Sivaraman, G. Turn-on Fluorescence Sensor for Selective Detection of Fluoride Ion and Its Molecular Logic Gates Behavior. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 317, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.G.V.; Kesavan, M.P.; Sivaraman, G.; Rajesh, J. Colorimetric and NIR Fluorescence Receptors for F− Ion Detection in Aqueous Condition and Its Live Cell Imaging. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 3194–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.G.V.; Sharma, P.; Thiruppathi, G.; Sundararaj, P.; Draksharapu, A. A Highly Selective Indole-Based Sensor for Zn2+, Cu2+, and Al3+ Ions with Multifunctional Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 7335–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attin, T.; Paqué, F.; Ajam, F.; Lennon, Á.M. Review of the Current Status of Tooth Whitening with the Walking Bleach Technique. Int. Endodontic. J. 2003, 36, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesan, S.; Kaliyadan, F.; Ashique, K.T.; Karunakaran, A. Bleaching and Skin-lightening Practice among Female Students in South India: A Cross-sectional Survey. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R. Comparison of Efficacy of Sodium Hypochlorite with Sodium Perborate in the Removal of Stains from Heat Cured Clear Acrylic Resin. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2009, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineback, C.B.; Nkemngong, C.A.; Wu, S.T.; Li, X.; Teska, P.J.; Oliver, H.F. Hydrogen Peroxide and Sodium Hypochlorite Disinfectants Are More Effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms than Quaternary Ammonium Compounds. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Collins, D.B.; Abbatt, J.P.D. Indoor Illumination of Terpenes and Bleach Emissions Leads to Particle Formation and Growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11792–11800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erina, A.A.; Borodulin, V.B.; Dereven’kov, I.A.; Makarov, S.V.; Ischenko, A.A. Destruction of Vitamin B12 During Interaction with Active Oxygen Species. ChemChemTech 2024, 67, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becking, A.G. Complications in the Use of Sodium Hypochlorite during Endodontic Treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1991, 71, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agneta, M.; Zhaomin, L.; Chao, Z.; Gerald, G. Investigating Synergism and Antagonism of Binary Mixed Surfactants for Foam Efficiency Optimization in High Salinity. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 175, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, J. Photography: Enhancing Sensitivity by Silver-Halide Crystal Doping. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2003, 67, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royaux, E.; Van Ham, L.; Broeckx, B.J.G.; Van Soens, I.; Gielen, I.; Deforce, D.; Bhatti, S.F.M. Phenobarbital or Potassium Bromide as an Add-on Antiepileptic Drug for the Management of Canine Idiopathic Epilepsy Refractory to Imepitoin. Vet. J. 2017, 220, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Kenseth, C.M.; Huang, Y.; Dalleska, N.F.; Seinfeld, J.H. Iodometry-Assisted Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Analysis of Organic Peroxides: An Application to Atmospheric Secondary Organic Aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, S.; Reyna-Neyra, A.; Ferrandino, G.; Amzel, L.M.; Carrasco, N. The Sodium/Iodide Symporter (NIS): Molecular Physiology and Preclinical and Clinical Applications. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Sayama, K.; Arakawa, H. Dye-Sensitized Photocatalysts for Efficient Hydrogen Production from Aqueous I− Solution under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2004, 166, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dios Azorín Abraham, J.; Durán, G.T.; Pabón, N.S.T.; Peña-Fernández, A.; Fernández, M.Á.P. Development of a Formulation of Potassium Iodide Tablets as an Antidote against Nuclear Incidents. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Liu, T.; Li, S.; Zhu, D.; Fan, Y.; Fan, R.; Ding, C.; Jin, W.; Hu, J. Construction of a Near-Infrared Excited RhB@UCNPs Fluorescent Probe for Hypochlorite Detection. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Guetzloff, M.B.; Kakumanu, R.; Ostlund, T.R.; Halaweish, F.T.; Logue, B.A. Development of a Rapid Fluorescence Probe for the Determination of Aqueous Hypochlorite. Anal. Lett. 2025, 58, 2249–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, H.; Batsaikhan, O.; Park, S.; Kim, K.-T.; Kim, C. Easy and Portable Fluorescent Probe for ClO− Detection in Pure Water: A Versatile Platform for Environmental Samples, Bioimaging, and Smartphone-Assisted Technologies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gan, Y.; Lai, B.; Ran, X.; Cao, D.; Wang, L. A Portable Sensing Platform Using a Novel Dipyrrolopyrazinedione-Based Aza-BODIPY Dimer for Highly Efficient Detection of Hypochlorite and Hydrazine. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 341, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Redshaw, C.; Zhang, Q. A Schiff Base Dual Mode”Turn-On” Fluorescent Probe for Selective Detection of HClO/ClO− in Buffer. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1343, 142876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, S.; Jian, Y. An ESIPT-Type Fluorescent Probe Based on Benzoquinoline for the Detection of Hypochlorite in Living Cells. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Cheng, P.; Xu, K. Naphthalene-Dicyanoisophorone Hybrid Fluorescent Probe for Detection of Hypochlorite Based on Cyclization Mechanism. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 438, 137808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Schweitzer, D.; Richter, S.; Königsdörffer, E. Sodium Fluorescein as a Retinal pH Indicator? Physiol. Meas. 2005, 26, N9–N12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, J.L.; Manzano, E.; Avidad, R.; Orbe, I.; Capitán-Vallvey, L.F. Spectrofluorimetric Determination of Traces of Bromide. Mikrochim. Acta 1994, 113, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, H. A Selective Fluorescence-on Reaction of Spiro Form Fluorescein Hydrazide with Cu(II). Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 575, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Gamov, G.A.; Kiselev, A.N.; Nikitin, G.A. A Fluorescein Conjugate as Colorimetric and Red-Emissive Fluorescence Chemosensor for Selective Recognition Cu2+ Ions. Opt. Mater. 2024, 153, 115580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Huo, F.; Su, J.; Yang, Y.; Yin, C.; Yan, X.; Jin, S. Sensitive Colorimetric and Fluorescent Detection of Mercury Using Fluorescein Derivations. OJAB 2012, 01, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pradhan, T.; Wang, F.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. Fluorescent Chemosensors Based on Spiroring-Opening of Xanthenes and Related Derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1910–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Memon, N.; Mallah, M.A.; Channa, A.S.; Gaur, R.; Jiahai, Y. Recent Development in Fluorescent Probes for Copper Ion Detection. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, S.; Maity, A.C.; Das, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, N. Dual-Mode Chemosensor for the Fluorescence Detection of Zinc and Hypochlorite on a Fluorescein Backbone and Its Cell-Imaging Applications. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 2739–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachapermpon, Y.; Chaneam, S.; Charoenpanich, A.; Sirirak, J.; Wanichacheva, N. Highly Cu2+-Sensitive and Selective Colorimetric and Fluorescent Probes: Utilizations in Batch, Flow Analysis and Living Cell Imaging. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Islam, A.S.M.; Prodhan, C.; Ali, M. A Fluorescein-Based Chemosensor for “Turn-on” Detection of Hg2+ and the Resultant Complex as a Fluorescent Sensor for S2− in Semi-Aqueous Medium with Cell-Imaging Application: Experimental and Computational Studies. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 5297–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, S.; Aydin, D.; Kocyigit, O. Nanomolar “Turn-On” Hg2+ Detection by a Fluorescein Based Fluorescent Probe: DFT Calculations, Bioimaging and on-Site Assay Kit Studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 310, 128376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Saleh Musha Islam, A.; Sasmal, M.; Prodhan, C.; Ali, M. A Fluorescein-2-(Pyridin-2-Ylmethoxy) Benzaldehyde Conjugate for Fluorogenic Turn-ON Recognition of Hg2+ in Water and Living Cells with Logic Gate and Memory Device Applications. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2022, 543, 121165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Kiselev, A.N.; Isagulieva, A.K.; Shibaeva, A.V.; Kuzmin, V.A.; Morozov, V.N.; Zevakin, E.A.; Petrova, U.A.; Knyazeva, A.A.; Eroshin, A.V.; et al. Shedding Light on Heavy Metal Contamination: Fluorescein-Based Chemosensor for Selective Detection of Hg2+ in Water. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Pogonin, A.E.; Gamov, G.A. Hg2+-Induced Hydrolysis of Fluorescein Hydrazone: A New Fluorescence Probe for Selective Recognition Hg2+ in an Aqueous Solution. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1334, 141930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Wang, D.; Mi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, F. Novel Fluorescence Probe toward Cu2+ Based on Fluorescein Derivatives and Its Bioimaging in Cells. Biosensors 2022, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Meng, X.; Fang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Duan, H.; Hao, A. Two Novel Pyrazole-Based Chemosensors: “Naked-Eye” Colorimetric Recognition of Ni2+ and Al3+ in Alcohol and Aqueous DMF Media. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 14630–14641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016.

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XX. A Basis Set for Correlated Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcraft—Graphical Program for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com/index.html (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Shi, W.; Wang, K.; Ma, H. A Highly Selective and Sensitive Fluorescence Probe for the Hypochlorite Anion. Chemistry 2008, 14, 4719–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, D.; Kambam, S.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yin, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, X. A Highly Specific Fluorescent Probe for Hypochlorite Based on Fluorescein Derivative and Its Endogenous Imaging in Living Cells. Dyes Pigments 2015, 120, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-C.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, A.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tan, W. An Efficient Ratiometric Fluorescent Excimer Probe for Hypochlorite Based on a Cofacial Xanthene-Bridged Bispyrene. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, L. A Fluorescence Ratiometric Sensor for Hypochlorite Based on a Novel Dual-Fluorophore Response Approach. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 775, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, D.D.; Belcher, R.R. The Selection of Masking Agents for Use in Analytical Chemistry. C R C Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1975, 5, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis, L.D. Teaching Old Dyes New Tricks: Biological Probes Built from Fluoresceins and Rhodamines. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, L.; Lewin, M.; Bloch, R. The Reaction between Hypochlorite and Bromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 1988–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.M.; Robertson, K.J. Determination of HCIO Plus CIO− by Bromination of Fluorescein. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1980, 52, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, C.M.; Gazda, M.; Margerum, D.W. Non-Metal Redox Kinetics: Hypobromite and Hypoiodite Reactions with Cyanide and the Hydrolysis of Cyanogen Halides. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 5739–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, J.C.; Paquette, J.; Sunder, S.; Ford, B.L. Iodine Chemistry in the +1 Oxidation State. II. A Raman and Uv–Visible Spectroscopic Study of the Disproportionation of Hypoiodite in Basic Solutions. Can. J. Chem. 1986, 64, 2284–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, T.; Kita, Y. Oxidizing Agents. In Iodine Chemistry and Applications; Kaiho, T., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 277–301. ISBN 978-1-118-46629-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yu, T.; Ji, J.; Zhu, W.; Fang, M.; Li, C. A Novel Fluorescent Probe Based on Carbazole-Thiophene for the Recognition of Hypochlorite and Its Applications. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 310, 123912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Huang, B.; Tian, M.; Feng, F. A Novel Diaminomaleonitrile-Based Fluorescent Probe for the Fast Detection of Hypochlorite in Water Samples and Foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 128, 106053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, B.; Jiang, C.; Sun, R.; Hu, P.; Chen, S.; Wu, W. A BODIPY Based Fluorescent Probe for the Rapid Detection of Hypochlorite. J. Fluoresc. 2018, 28, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, D.; Subramanian, K. A Phenothiazine-Functionalized Pyridine-Based AIEE-Active Molecule: A Versatile Molecular Probe for Highly Sensitive Detection of Hypochlorite and Picric Acid. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 5149–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.-H.; Hu, H.-R.; Liu, R.-B.; Sheng, G.-Z.; Niu, J.-J.; Fang, Y.; Wang, K.-P.; Hu, Z.-Q. A Triphenylamine-Based Fluorescence Probe for Detection of Hypochlorite in Mitochondria. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 299, 122830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z.; Chen, M.; Qian, X. Fluorescence Sensing of Iodide and Bromide in Aqueous Solution: Anion Ligand Exchanging and Metal Ion Removing. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, N.; Jang, D.O. Selective Detection of Hg(II) with Benzothiazole-Based Fluorescent Organic Cation and the Resultant Complex as a Ratiometric Sensor for Bromide in Water. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 3535–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.G.; Na, W.S.; Mayank; Singh, N.; Jang, D.O. Triazole-Coupled Benzimidazole-Based Fluorescent Sensor for Silver, Bromide, and Chloride Ions in Aqueous Media. J. Fluoresc. 2019, 29, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Han, M.S. pH-Guided Fluorescent Sensing Probe for the Discriminative Detection of Cl− and Br− in Human Serum. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1210, 339879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumawat, L.K.; Abogunrin, A.A.; Kickham, M.; Pardeshi, J.; Fenelon, O.; Schroeder, M.; Elmes, R.B.P. Squaramide—Naphthalimide Conjugates as “Turn-On” Fluorescent Sensors for Bromide Through an Aggregation-Disaggregation Approach. Front. Chem. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Qiao, Y.-H.; Lin, H.; Lin, H.-K. A Novel Switch-on Fluorescent Receptor for Bromide Based on an Amide Group. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2008, 62, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreja, P.; Kaur, N. A New Multifunctional 1, 10-Phenanthroline Based Fluorophore for Anion and Cation Sensing. J. Lumin. 2015, 168, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Xiong, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; Hu, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, W.; et al. A Novel Fluorescence Sensor for Iodide Detection Based on the 1,3-Diaryl Pyrazole Unit with AIE and Mechanochromic Fluorescence Behavior. Molecules 2023, 28, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.H.; Liu, S.G.; Ling, Y.; Li, N.B.; Luo, H.Q. Facile Method for Iodide Ion Detection via the Fluorescence Decrease of Dihydrolipoic Acid/Beta-Cyclodextrin Protected Ag Nanoclusters. Spectrochim. Acta Part Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 212, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, D.K.; Majee, P.; Mondal, S.K.; Mahata, P. A Luminescent Cadmium Based MOF as Selective and Sensitive Iodide Sensor in Aqueous Medium. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 356, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-J.; Yan, H.; Sun, Y.-L.; Lu, C.-Y.; Huang, T.-Y.; Chen, S.-J.; Hu, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Wu, A.-T. A Simple and Highly Selective Receptor for Iodide in Aqueous Solution. Analyst 2012, 137, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Singh, N.; Kim, M.J.; Jang, D.O. Chromogenic and Fluorescent Recognition of Iodide with a Benzimidazole-Based Tripodal Receptor. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3024–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, M.; Ding, H.; Fan, C.; Liu, G.; Pu, S. A Water-Soluble Colorimetric and Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe Based on Phenothiazine for the Detection of Hypochlorite Ion. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 215, 111194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).