Abstract

Background/Objectives: The donor liver shortage has created an urgent need to utilize higher-risk grafts for transplantation. Normothermic machine perfusion enables ex vivo graft assessment prior to transplantation, offering a route to expand access safely. However, proposed performance metrics often fail to differentiate dysfunctional grafts from functional grafts. Organs showing borderline results require careful deliberation as clinicians seek to balance recipient safety with waiting list access. The crucial question remains: are we discarding organs appropriately? Methods: To address this question, we describe a novel “secondary perfusion” model. We suggest that organs declined for transplantation after normothermic perfusion be subjected to an additional trial of cold ischemia and warm reanimation, mimicking reperfusion. Results: We present a protocol description and proof-of-concept case study using a marginal donor liver, showing how secondary perfusion enabled confirmation of predicted dysfunction. Conclusions: We share a protocol for modeling the performance of discarded organs in a recipient. We aim for this proof of concept to enable further investigation of existing viability criteria and better inform clinical decision-making.

1. Introduction

To meet a growing waiting list, the field of liver transplantation has increasingly shifted toward enhanced organ preservation strategies and the consideration of a broader range of grafts for transplantation. Expanded criteria donors (ECD) include those with greater body mass index (BMI), older age, steatosis, hepatitis B and/or C, and/or organs donated after circulatory death (DCD) [1]. Utilizing organs from these donors is a route to expand treatment for patients on the waiting list; currently, there are over 103,000 in the U.S. [2]. Data from previous years show that approximately 9% of patients on the liver waiting list die before receiving a donor organ, and another 15.6% become too sick for transplant [3]. Although new techniques such as normothermic regional perfusion have reduced the risks associated with DCD organs, recipients of ECD grafts are still at a greater risk of life-threatening complications post-transplant than recipients of non-ECD grafts [4,5]. On the other hand, up to 10% of potentially suitable donor livers are declined for transplantation, often due to insufficient information about graft quality [6]. A balance has to be achieved between proper non-use of unsafe organs and unnecessary waste of organs that may have functioned in a recipient. Normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) is a rapidly growing technique that offers an opportunity for assessment of graft function prior to transplantation, creating a route to expanded graft utilization. Many centers across the United States have now implemented NMP programs either using a back-to-base or device-to-donor model, and reported outcomes appear universally promising [7,8].

NMP involves ex vivo perfusion of the donor liver with a blood-based perfusate under physiological conditions, restoring metabolic function to enable functional testing. However, it remains unclear which NMP parameters, if any, best predict an organ’s performance post-transplant. Proposed viability criteria include lactate clearance, pH homeostasis, glucose utilization, liver enzymes, flow rates, macroscopic appearance, and bile production and/or composition, but validation studies are lacking [9]. For example, lactate clearance, often thought of as the gold standard in viability testing, has been previously shown by our group to lack a correlation with early allograft dysfunction [10]. Bile proteomic analysis has been increasingly studied as a metric for cholangiocyte viability but has yet to become integrated into standard practice [11]. Meanwhile, the use of potential metabolic biomarkers like flavin mononucleotide remains confined to single centers [12]. A lack of clarity in the field, combined with the overall worsening quality of organs in the donor pool due to health trends in the general population, makes optimizing NMP viability assessment crucial [13].

The goal is to minimize risk to potential recipients while maximizing graft utilization, improving care and access for patients on the waiting list. Three groups have performed viability testing of discarded grafts with NMP, demonstrating outcomes comparable to those in recipients of non-discarded grafts [9,14,15]. However, this strategy was performed on grafts that were discarded prior to ever being perfused, i.e., only ever subjected to static cold storage (SCS) and not yet to NMP. Other studies have transplanted discarded donor livers that were subjected to hypothermic machine perfusion, controlled oxygenated rewarming, and then NMP, but these perfusions were consecutive, i.e., without a cold ischemic period, and again, the grafts had not previously undergone NMP [16]. There remains a gap in the literature on information gleaned from organs declined for transplantation after undergoing NMP. In a practical scenario, organs from our institution that are not used for transplant after failing to meet viability criteria are offered back to the organ procurement organization (OPO). The OPO will typically instruct that the organ be disposed of locally, and less commonly allocate the organ to research. The question is as follows: are these organs genuinely not suitable for transplant, and can we create a method to validate if not using the graft was the right decision?

We propose to approach this concept by testing each liver that does not meet viability criteria during NMP using a stress test evaluation called “secondary perfusion.” By subjecting the organ to a second round of cold ischemia and NMP, our model will enable evaluation of any potential capability for recovery or validation of the organ’s non-viability. Reverse-engineering viability criteria by inflicting a stress test upon the most marginal organs could create a new route for the investigation of borderline grafts in the NMP setting. Organs that fail secondary perfusion would confirm their unsuitability for transplant, and those that recover functionality would guide studies to refine NMP criteria and reduce unnecessary graft discard. Our model could allow for large-scale, collaborative studies to define donor liver risk profiles better, particularly offering data from marginal organs often lacking in current research. By expanding available datasets, our model could also contribute to the growing applications of artificial intelligence (AI) to liver transplantation [17]. In this paper, we describe a protocol for the secondary perfusion technique.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Overview

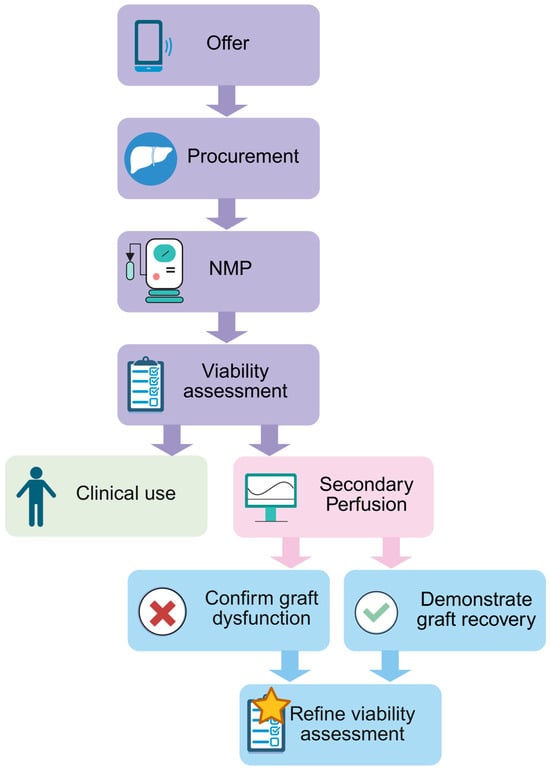

We assessed a donor liver that was ultimately declined for transplantation. Our aim was to investigate viability criteria by modeling post-reperfusion data from a marginal organ, designated Liver X, with a low-risk donor but high-risk histologic features. Liver X demonstrated limited function during NMP evaluation and was declined for clinical use. By subjecting the liver to a second round of cold ischemia and NMP, we induced a secondary insult akin to transplantation and aimed to evaluate if the decision to decline the organ was indeed justified (Figure 1). In this paper, we fully characterize the secondary perfusion method so that it can be reproduced by other groups. We describe the conclusion of primary perfusion, the implementation of cold ischemia, and the process of performing and interpreting data from secondary perfusion.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing an overview of the secondary perfusion workflow. Created using BioRender.com.

2.2. Conclusion of Primary Perfusion

- Identify when a liver undergoing NMP does not meet viability criteria and is declined for transplantation. Confirm the research consent of the donor and that the declined organ will not be accepted for transplant by another center.

- Stop perfusion. Remove the liver from the perfusion device and transfer the organ to a basin containing surgical-grade ice.

- Connect a flush line to the portal vein (PV) and hepatic artery (HA) cannulae. It is important that the inferior vena cava is open to allow for drainage. Administer cold flush solution as per center standard (options include University of Wisconsin solution (UW-Madison Department of Surgery, Madison, WI, USA) and Custodial histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) solution (Essential Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Raleigh, NC, USA)). Use 2–4 L of flush solution as necessary for the effluent to become clear and the liver to show a homogenous appearance.

- Weigh the liver to obtain a post-perfusion weight. Capture post-perfusion photographs, tissue biopsies, and/or perfusate and bile samples as per center protocol.

- Enclose the liver within a sterile organ bag and store the liver using SCS. At our center, 0.5–1 h is the typical timeframe from the removal of the organ from the perfusion platform until implantation commences, so our secondary perfusion protocol allows the liver to incur 1–1.5 h of cold ischemic time (CIT). Subjecting the organ to cold ischemia in the secondary perfusion model is crucial to mimic properly the insult that would have occurred during transplantation. By prolonging the CIT somewhat, we aim to inflict the upper limit of injury reasonably expected for a liver undergoing transplantation post-NMP. This timeframe will also enable researchers to complete necessary preparations for secondary NMP. However, each center will likely vary in typical CIT during the liver offboarding process. We recommend adapting the experimental protocol to fit individual circumstances.

2.3. Cold Storage Phase

- Assemble the designated perfusion device as per the manufacturer’s instructions. For the secondary perfusion model to properly mimic reperfusion, it is vital that the perfusion be normothermic (36–37 °C). Beyond this physiologic requirement, any NMP device is acceptable for the secondary perfusion model, including the Liver Assist (XVIVO, Gothenburg, Sweden), the metra (OrganOx, Oxford, UK), the Organ Care System (TransMedics, Andover, MA, USA), and homemade platforms. Our center utilizes the metra for clinical perfusions. Centers that utilize other devices will likely have different institutional viability criteria. Secondary perfusion may be performed regardless, with the understanding that any graft declined for transplantation after NMP has failed to meet viability criteria specific to the perfusion device used. For secondary perfusions, our center utilizes the Liver Assist for logistical reasons. Switching devices may affect the interpretation of results, as different devices have different target thresholds for values such as temperatures, flow rates, and pressures, and therefore represent a limitation to this work. If possible, we recommend that centers utilize the same device type for secondary perfusion as was used for primary perfusion to control variability and better enable comparison of perfusion data. If there are logistical constraints and a different device type must be used, we strongly recommend utilizing a consistent device type for all secondary perfusions to better enable a comparative study.

- After assembling the device, prepare the perfusate and prime the circuit. The only perfusate requirement for the secondary perfusion model is that the perfusate has a sufficient oxygen-carrying capacity; specific composition will vary with each center’s preferred device and available resources. Our center utilizes a base perfusate composition of 3 units of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) and 500 mL of 5% human albumin (Grifols, Raleigh, NC, USA). Although a high hematocrit is ideal to maximize circulating oxygen levels, a lower level is tolerated for secondary perfusion because of the scarcity of blood supplies for research [18,19]. Our center aims to maintain a hematocrit of >18%. We utilize expired human pRBCs for research perfusions. To conserve valuable resources, centers may also choose to collect blood used during the primary perfusion, wash the blood during the secondary cold storage phase, and re-use this blood for the secondary perfusion.

- Administer baseline boluses as per center protocol. We utilize the following:

- A total of 10 mL of 10% calcium gluconate (Fresenius Kabi, IL, USA);

- In total, 10,000 units of heparin (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) to prevent clotting;

- A total of 750 mg of cefuroxime (SAGENT Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL, USA), reconstituted with 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA), to prevent infection.

- Prepare infusions as per the center’s protocol. We utilize the following infusions at a rate of 1 mL per hour:

- In total, 5.6 g of sodium taurocholate (OrganOx Ltd., Oxford, UK), reconstituted in 30 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA);

- A total of 2 mL of 100 units/mL short-acting insulin (Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA), diluted in 28 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA);

- In total, 0.5 mg of epoprostenol (Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA), reconstituted in 10 mL of sterile water (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA), diluted in 25 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA);

- A total of 5 mL of 5000 units/mL heparin (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA), diluted in 25 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA).

- Once the device is primed and perfusate is circulating, allow 10–15 min for the device to reach a normothermic temperature before conducting a baseline arterial blood gas (ABG). Confirm that the perfusate pH is in the desired range. If the pH is acidotic, add sodium bicarbonate to achieve the target pH (our center’s target range is 7.25–7.35) and allow 5–15 min to circulate.

- With the surgical team, open the sterile organ bag on the back table. Maintain the organ on surgical ice. Cannulate the organ’s vasculature as necessary for the selected perfusion device.

- Connect cannulae to a flush line. Fill the organ with room temperature 5% human albumin (500–1000 mL as needed, given organ size). This step is necessary to remove the preservation solution, which is hyperkalemic.

- Confirm that the target CIT has been achieved. In an ideal scenario, the target CIT should be long enough to stress the liver to traditional preservation stress (i.e., the second round of cooling after NMP).

2.4. Initiation of Secondary Perfusion

- Onboard the organ to the perfusion device as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Start perfusion. Closely monitor flow rates and pressures to ensure proper onboarding. Ligate any major bleeds to maintain hemostasis and ensure accurate interpretation of flow rate and pressure readings.

- Cannulate the bile duct and assemble the bile collection chamber as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Aim to maintain perfusion for a minimum of 4–6 h. A longer duration may allow for a more nuanced understanding of the organ’s trajectory post-reperfusion.

- Throughout the duration of perfusion, perform routine ABGs as per the center’s protocol. Administer medications as necessary to maintain target values of designated parameters. Our center commonly responds to the following parameters.

- pH: If persistently acidotic, bolus bicarbonate.

- Glucose: Titrate total parenteral nutrition (TPN) based on the center’s protocol and TPN composition. Our center starts with a baseline infusion of 20% dextrose TPN (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, IL, USA) at 15 mL/h. If glucose drops below 100 mg/dL, we administer a bolus of 50% dextrose (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) for a quicker response.

- pO2: Adjust the oxygen flow rate and/or the sweep gas flow as necessary.

- Calcium: Administer calcium gluconate to achieve a target calcium level of 1.05–1.30 mmol/L.

- If bile is present, record the volume. Perform a point-of-care bile gas analysis to assess the same parameters as measured by the perfusate ABG. Bile gas results will not typically inform medication administration but will be useful for viability analysis once the experiment is concluded.

- If resources and ethical guidelines allow, we recommend performing tissue biopsies of the liver parenchyma every 2–4 h. Rotate the location of the biopsies to ensure relatively well-perfused tissue is sampled at each timepoint. Properly stored tissue samples will enable histological and metabolomics analysis following the conclusion of the experiment. In addition, capture a photograph of the graft. Gross imaging will be helpful in assessing the macroscopic appearance of the graft.

- Perform laboratory testing as per each center’s protocol. Our center performs the following tests: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, and D-dimer levels. AST and ALT can be used to interpret the level of hepatic injury. D-dimer level can provide context for microthrombi burden and risk of biliary injury [20].

- At every timepoint any diagnostic testing is performed, record the hemodynamic parameters measured by the perfusion device. Our center records the following parameters: HA flow, HA pressure, HA temperature, PV flow, PV pressure, and PV temperature. Because the liver will be of poor quality and has been subjected to a secondary insult, the graft resistance may be high. If flow rates are below target levels despite administering the infusion of diluted epoprostenol as described previously, we recommend administering a bolus of any available, non-diluted vasodilator, such as epoprostenol or verapamil.

- Terminate the experiment once the desired duration is reached or the maintenance of the perfusion has become futile. Signs that the perfusion has reached its limit include: perfusate lactate > 10 mmol/L for >2 h; pH persistently acidotic with >20 mL 8.4% sodium bicarbonate added every 30–45 min; persistently unstable hemodynamics despite the use of vasodilators; discolored and/or darkened parenchyma; or foul odor. At this time, stop perfusion, remove all cannulae from the organ, and obtain a post-perfusion weight, ABG, bile gas, biopsy, gross imaging, and laboratory results as desired. Properly return the organ to the center’s pathology department.

3. Results

3.1. Procurement

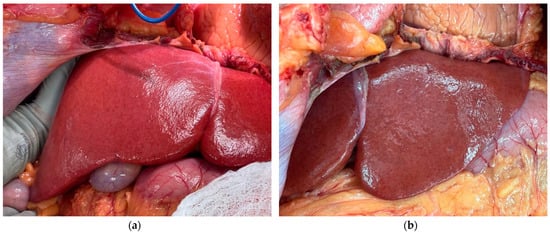

We hypothesize that most secondary perfusions may produce borderline results of the kind we observed with our pilot study of Liver X. Liver X was accepted for procurement from a 40-year-old, male, brain-dead donor with a BMI of 32.2 kg/m2. The donor was negative for Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV, and cytomegalovirus. In situ, the liver appeared healthy with a normal macroscopic appearance and uniform, homogenous color (Figure 2a,b).

Figure 2.

Gross imaging of the liver in situ at the donor hospital: (a) right lobe and (b) left lobe.

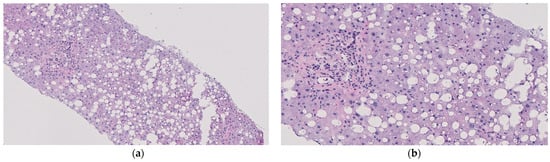

Still, the liver was biopsied in situ due to procurement surgeon concerns about potential underlying steatosis given the donor’s history of heavy alcohol use, administration of multiple vasopressors, and concomitant high liver enzymes. The liver was then procured in the standard fashion and transported to our hospital using SCS. The initial CIT was 362 min. This liver was originally intended to be utilized for transplantation without undergoing NMP due to particularly low-risk features (at our institution, the majority of donor livers accepted for procurement—approximately 90%—undergo perfusion prior to a final decision regarding utilization for transplantation). However, an intraoperative biopsy of Liver X revealed 50% macrosteatosis with evidence of active lipolysis (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Histological imaging of the liver from biopsies taken throughout the procedure and stained with hematoxylin and eosin: (a) in situ at the donor hospital; observed with 10× magnification; (b) in situ at the donor hospital and observed with 20× magnification; (c) post-primary NMP during SCS and observed with 10× magnification; (d) post-primary NMP during SCS and observed with 20× magnification; (e) at the conclusion of secondary NMP and observed with 10× magnification; (f) at the conclusion of secondary NMP and observed with 20× magnification.

It is of note that surgical visual inspection did not detect severe macrosteatosis; reliable visual analysis methods warrant more study, with multiple platforms utilizing AI presently in development [21,22]. Regardless, at our institution, a macrosteatosis level > 30% is an indication for NMP of a graft to assess function and minimize recipient risk. Liver X was therefore prepared for perfusion at our facility in a back-to-base manner.

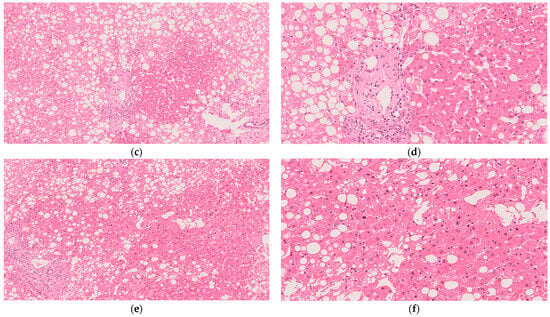

3.2. Primary Perfusion

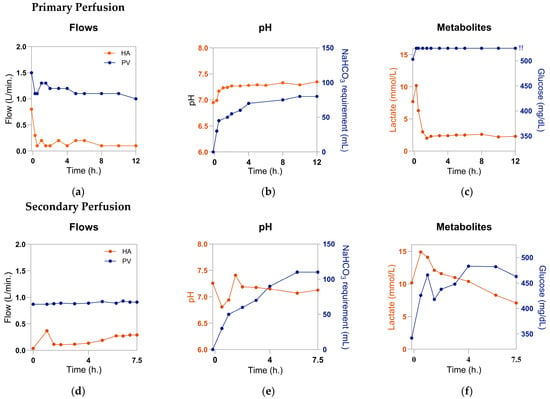

Once surgical preparations were completed, Liver X was onboarded to the OrganOx metra device according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pre-NMP weight was 2000 g. NMP was performed for 12 h. Perfusion parameters, blood gas analysis, and liver enzymes were monitored. Liver X showed low HA flows (0.1 to 0.2 L/min) (Figure 4a), absent bile production, and a mean pH of 7.23 (Figure 4b) that required ongoing bicarbonate resuscitation (Figure 4b). Despite clearing lactate from 10.2 to 2.3 mmol/L, Liver X did not reach our target of <2.2 mmol/L (Figure 4c), nor did it demonstrate glucose utilization (Figure 4c). Finally, AST and ALT were elevated at levels of 4503 and 5571 U/L, respectively. Following careful consideration, the liver was ultimately not used for transplantation. Our center’s viability criteria can be reviewed in Table 1. They were developed based on work from previous trials and serve as general guidelines, with ultimate decisions up to the surgeon’s discretion [15,18]. For reference, at our center, approximately 5% of grafts fail NMP viability testing.

Figure 4.

Functional parameters of the liver: (a) hepatic artery (HA) and portal vein (PV) flow rates during primary perfusion; (b) perfusate pH and total sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) administration; (c) perfusate lactate and glucose levels; (d) HA and PV flow rates during secondary perfusion; (e) perfusate pH and total NaHCO3 administration during secondary perfusion; (f) perfusate lactate and glucose levels during secondary perfusion. !!: perfusate glucose levels exceed measurable range (>525 mg/dL). Created with GraphPad Prism 10.3.1.

Table 1.

Our center’s viability criteria for a liver undergoing NMP *.

3.3. Secondary Perfusion

After obtaining permission to use the organ for research from the OPO, we sought to investigate how this liver may have performed in vivo. The liver was removed from the metra, flushed with 4 L of cold Custodiol HTK solution (Essential Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Raleigh, NC, USA), and stored with SCS for 1.5 h before undergoing NMP using the Liver Assist device. NMP was performed for 7.5 h at 37 °C with an oxygenated, blood-based perfusate. Evaluative parameters for Liver X were kept consistent from the initial perfusion to assess any changes from the baseline.

HA flow rates were increased relative to those observed during primary NMP but still remained low (0.37 L/min at 1 h NMP, then <0.3 L/min at every timepoint afterwards) (Figure 4d). Acidosis persisted with a mean pH of 7.13, despite the addition of 110 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (Figure 4e). The liver showed minimal—though present—glucose utilization, with a drop in glucose level from 466 mg/dL at 1 h NMP to 418 mg/dL at 1.5 h NMP (Figure 4f). This finding was somewhat surprising given that the liver failed to utilize any glucose within the measurable range during its initial perfusion (Figure 4c). It is possible that the liver’s glycogen and free glucose were depleted during its secondary SCS period, accounting for the drop from the final glucose level of >525 mg/dL at the end of primary perfusion to the initial glucose level of 342 mg/dL at the start of secondary perfusion. The ensuing rise in glucose from 1.5 h to 6 h may indicate impaired metabolic function or may be a result of the conversion of lactate into glucose through the Cori cycle; the liver showed elevated lactate levels during secondary perfusion that exceeded the level reached during primary NMP (14.9 mmol/L vs. 10.2 mmol/L, respectively). After reaching this peak lactate at 30 min. of secondary perfusion, lactate trended downward at every timepoint until 7.5 h, reaching a nadir of 7.1 mmol/L by the completion of the study (Figure 4f). The evidence of some intact lactate clearance functionality was of interest because the clinical lactate progression showed a spike from 90 min to 8 h and again from 10 h to 12 h. This finding may speak to “zone 1” liver function, which has been shown to be the baseline for donor liver viability during perfusion, i.e., a criterion that is necessary but insufficient for a graft to meet to demonstrate viability [23]. However, a larger sample size would be required to fully evaluate this hypothesis, and results should be interpreted with caution in the context of this n = 1 proof-of-concept.

Biopsy taken just prior to commencing secondary NMP (i.e., during SCS) showed >30% steatosis (Figure 3c,d). The same result was shown at the conclusion of secondary NMP (Figure 3e,f). Subjectively, there appears to be a mild decrease in steatosis from before to after secondary NMP; however, the described phenomenon of de novo de-fatting during NMP typically is observed over much longer perfusions (e.g., 24+ h) and does not present on histology [24]. In addition, this finding cannot be confirmed objectively because our institution’s maximum cut-off for research pathologist scoring is 30%. It is, therefore, not possible to compare pre- and post-secondary perfusion histology with histology obtained at procurement (>50% steatosis).

It is also important to note that the primary perfusion was performed using the metra device, whereas the secondary perfusion was performed using the Liver Assist device. The metra device provides arterial perfusion using a centrifugal pump operating continuously. The Liver Assist device also provides arterial perfusion using a centrifugal pump, but the pump operates in a pulsatile manner. Although each machine has different hemodynamic thresholds, both should provide the liver with enough oxygenated perfusate to allow for full metabolic activity. Still, this distinction may impact the ability to compare results from primary to secondary NMP. Further studies would be needed to confirm the comparability of outcomes when utilizing this platform.

Though HA flow rates showed an upward trend, glucose utilization was newly observed, and lactate clearance resumed, all criteria remained below our institutional thresholds for viability. The organ’s capacity to maintain pH was particularly impaired. These mixed data show the imperfection of current viability standards. Though no conclusions may be drawn from a sample size of one, our findings suggest the need for further inquiry into the capacity of grafts for recovery post-reperfusion and what results may be seen over more extended perfusions. If transplanted, we do believe Liver X would have been at risk for primary nonfunction, but limited conclusions can be drawn from this pilot study. Establishing markers that reliably predict such outcomes is a critical need.

4. Discussion

We propose secondary perfusion as a platform to evaluate the capacity for delayed recovery of a declined graft or to affirm the criteria used to decline the graft for transplant. The literature remains uncertain regarding how a graft displaying mixed results during NMP may manifest itself in a recipient. We believe borderline liversultimately not used for transplant would be perfect candidates for secondary perfusion. For example, if a graft is discarded due to poor pH homeostasis, while other parameters are borderline, secondary perfusion would allow us to observe how it may have regulated pH upon reperfusion. If the graft is unable to recover this functional ability, it may reinforce the use of pH as an NMP viability criterion. Results could also help define which parameters should be considered major or minor viability criteria. Secondary perfusion could offer unique insight into data that would otherwise be impossible to obtain—all present clinical studies inherently focus on recipient outcomes from those receiving accepted grafts progressing to transplant. We propose that the study of marginal livers may provide insight into viability criteria most predictive of dangerous outcomes such as primary non-function.

A given donor liver assessed using NMP may be declined for transplantation if viability criteria are not met. Underpinning issues that lead to poor graft function during NMP may include steatosis or vascular defects, but such factors in and of themselves are not a reason for a liver to be declined after NMP. In regard to livers with steatosis, it is well-characterized that fatty livers are particularly susceptible to ischemia–reperfusion injury [25]. We anticipate that steatotic livers declined after the initial NMP may present particularly informative results during secondary perfusion, as they may perform abnormally [26]. More work is needed to fully understand how this pathology unfolds during NMP, and secondary perfusion could offer a route to investigation. Next, we foresee organs for transplant declining because of vascular issues (e.g., intractably low HA and/or PV flow rate) to present a further category of interest in the secondary perfusion model. It is unknown how hemodynamic issues observed during primary perfusion may manifest upon implantation. The secondary perfusion model could allow us to confirm true negatives of organs discarded on the basis of poor hemodynamics by supporting predictions of severe graft dysfunction after reperfusion and enabling in-depth analysis that would not otherwise be possible. Finally, organs procured from young donors that perform poorly during NMP often prompt rightfully intense clinical deliberation. The balance between using young, healthy organs and taking into account the results of NMP is life-altering and remains unclear. Secondary perfusion of any young organs discarded based on NMP could offer insightful guidance as the field seeks to understand how much weight to place on perfusion criteria.

It is also of note that this model’s implementation of repeated cycles of ischemia and reperfusion may enact similar biological processes as ischemic preconditioning. Given reports that ischemic preconditioning can improve liver viability, exploration into the idea of secondary perfusion as an instance of this sequential process may be warranted [27]. The phenomenon could be a factor to consider in explaining any observed graft performance improvements.

At this stage, we would not advocate that a liver “passing” secondary perfusion (i.e., showing drastically improved flow rates, lactate clearance, pH homeostasis, glucose utilization, etc.) be considered for transplantation. Much more extensive research would be required to ensure safety to the recipient, and even then, such a decision should only be pursued after thoughtful deliberation between the transplant center, OPO, and recipient. We would hypothesize that the most likely recipient might be one with a low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score who would be both unlikely to receive another organ offer and able to tolerate a risky graft; conversely, if a recipient were status 1A with no other offers on the horizon, that would need to be considered by the transplant center as well. Still, the protocol as a platform for graft repair and/or “second chance” acceptance for transplantation is not yet a relevant consideration, and the platform is not intended for re-offering grafts for transplantation at this stage. We intend this protocol as an experimental guide to interrogate existing performance metrics, enable cross-center comparisons, and particularly validate instances of grafts with suspected likelihood of dysfunction [28].

We also believe this model represents an opportunity for multicenter validation. Because each transplant center utilizes similar but distinct viability criteria for donor livers, grafts are often discarded on the basis of different viability criteria. A collaborative registry of secondary perfusion outcomes may enable cross-center comparison by studying how grafts discarded on the basis of different viability criteria perform in a reperfusion model. In addition, centers use a variety of perfusion devices, which may present differences in readouts, technical approaches, and timing. We believe that these variances present an opportunity to use the secondary perfusion model to better understand viability criteria within the current reality of non-standardized NMP techniques. We have previously described our experience establishing the PUMP registry, which contains up-to-date clinical donor liver perfusion data from across several centers [29]. Our goal would be to leverage this growing registry as a ready-built, efficient platform, which could be expanded to enable data sharing from secondary perfusions, in addition to its current use for primary perfusions. By consolidating data on a variety of discarded organs, we hope to enable studies that otherwise would have limited comparison groups.

Ultimately, we hope that the secondary perfusion model will fill the present information gap, which leaves individual centers to use subjective evaluation methods that may perpetuate unnecessary graft discard. We believe our model will enable in-depth NMP viability assessment to expand the current limits of clinical decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.v.L. and M.Z.A.; methodology, L.L.v.L. and M.Z.A.; formal analysis, A.K.F.; investigation, A.K.F., K.M.F., L.L.v.L. and M.Z.A.; resources, A.K.F., L.L.v.L. and M.Z.A.; data curation, A.K.F., K.M.F. and L.L.v.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.F.; writing—review and editing, A.K.F., K.M.F., L.L.v.L., M.L.H., J.D., R.S., S.S.F. and M.Z.A.; visualization, A.K.F.; supervision, L.K.-S. and S.S.F.; project administration, L.L.v.L. and M.Z.A.; funding acquisition, L.K.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Blavatnik Family Foundation (grant number: 02855340).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Within our institution, all appropriate legal pathways were followed to obtain the donor organ described in this protocol. The donor organ was obtained based on the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, where part D states that a deceased donor organ may be used for research if not used for clinical purposes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470922/box/box_3-2/?report=objectonly) (accessed on 18 September 2025). The legal phrasing (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470922/) (accessed on 18 September 2025) states the following: “Even with this revised language, deceased donors are still not considered human subjects within the meaning of the Common Rule, although authorization for donation is still required for compliance with the UAGA.” As long as the proper donation and research consent were obtained by the OPO, the need for IRB consent for deceased donor organ research is waived.

Informed Consent Statement

The donor of this organ is dead, so consent is waived. OPOs communicate the consent (or lack thereof) to us.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alexander Fagenson, M.D., Ahmed Hassan, M.D., Jamie Frost, B.S., Brittany Sacks, B.S., and Meron Teklu, B.S., for their role in the primary liver perfusion and Maria Isabel Fiel, M.D., for her assistance in the histological analysis. We would also like to sincerely thank the organ donor and their family for their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This article is a revised and expanded version of an abstract entitled “Secondary Perfusion: Modeling Viability of Organs Declined for Transplant,” which was presented at the World Transplant Congress, San Francisco, CA, USA, August 2025.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECD | Expanded criteria donors |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DCD | Donation after circulatory death |

| NMP | Normothermic machine perfusion |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ABG | Arterial blood gas |

| SCS | Static cold storage |

| HTK | Histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate |

| CIT | Cold ischemic time |

| pRBCs | Packed red blood cells |

| HA | Hepatic artery |

| PV | Portal vein |

| TPN | Total parenteral nutrition |

| OPO | Organ procurement organization |

| MELD | Model for end-stage liver disease |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

References

- Feng, S.; Lai, J.C. Expanded Criteria Donors. Clin. Liver Dis. 2014, 18, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ Donation Statistics. Available online: https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Kwong, A.J.; Kim, W.R.; Lake, J.R.; Schladt, D.P.; Schnellinger, E.M.; Gauntt, K.; McDermott, M.; Weiss, S.; Handarova, D.K.; Snyder, J.J.; et al. OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report: Liver. Am. J. Transplant. 2024, 24, S176–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrovangelis, C.; Frost, C.; Hort, A.; Laurence, J.; Pang, T.; Pleass, H. Normothermic Regional Perfusion in Controlled Donation after Circulatory Death Liver Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodkin, I.; Kuo, A. Extended Criteria Donors in Liver Transplantation. Clin. Liver Dis. 2017, 21, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, J.; Todd, R.; van Leeuwen, L.L.; Bekki, Y.; Holzner, M.; Moon, J.; Schiano, T.; Florman, S.S.; Akhtar, M.Z. A Decade of Liver Transplantation in the United States: Drivers of Discard and Underutilization. Transplant. Direct 2024, 10, e1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Hong, H.; Gross, A.; Liu, Q.; Ali, K.; Cazzaniga, B.; Miyazaki, Y.; Tuul, M.; Modaresi Esfeh, J.; Khalil, M.; et al. The impact of normothermic machine perfusion and acuity circles on waitlist time, mortality, and cost in liver transplantation: A multicenter experience. Liver Transplant. 2025, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.C.; Zhang, C.; Chang, Y.H.; Li, X.; Ohara, S.Y.; Kumm, K.R.; Cosentino, C.P.; Aqel, B.A.; Lizaola-Mayo, B.C.; Frasco, P.E.; et al. Improved Outcomes and Resource Use with Normothermic Machine Perfusion in Liver Transplantation. JAMA Surg. 2025, 160, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergental, H.; Laing, R.W.; Kirkham, A.J.; Clarke, G.; Boteon, Y.L.; Barton, D.; Neil, D.A.H.; Isaac, J.R.; Roberts, K.J.; Abradelo, M.; et al. Discarded livers tested by normothermic machine perfusion in the VITTAL trial: Secondary end points and 5-year outcomes. Liver Transplant. 2024, 30, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Leeuwen, L.L.; Irizar, H.; Kim-Schluger, L.; Florman, S.; Akhtar, M.Z. The potential of machine learning to predict early allograft dysfunction after normothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, e298–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, A.M.; Wolters, J.C.; Lascaris, B.; Bodewes, S.B.; Lantinga, V.A.; Van Leeuwen, O.B.; De Jong, I.E.M.; Ustyantsev, K.; Berezikov, E.; Lisman, T.; et al. Bile proteome reveals biliary regeneration during normothermic preservation of human donor livers. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, P.C.; Van Leeuwen, O.B.; De Jonge, J.; Porte, R.J. Viability assessment of the liver during ex-situ machine perfusion prior to transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2024, 29, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orman, E.S.; Barritt, S.A.; Wheeler, S.B.; Hayashi, P.H. Declining liver utilization for transplantation in the United States and the impact of donation after cardiac death. Liver Transplant. 2013, 19, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raigani, S.; De Vries, R.J.; Carroll, C.; Chen, Y.; Chang, D.C.; Shroff, S.G.; Uygun, K.; Yeh, H. Viability testing of discarded livers with normothermic machine perfusion: Alleviating the organ shortage outweighs the cost. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olumba, F.C.; Zhou, F.; Park, Y.; Chapman, W.C.; the RESTORE Investigators Group. Normothermic Machine Perfusion for Declined Livers: A Strategy to Rescue Marginal Livers for Transplantation. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2023, 236, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, O.B.; de Vries, Y.; Fujiyoshi, M.; Nijsten, M.W.N.; Ubbink, R.; Pelgrim, G.J.; Werner, M.J.M.; Reyntjens, K.M.E.M.; van den Berg, A.P.; de Boer, M.T.; et al. Transplantation of High-risk Donor Livers after Ex Situ Resuscitation and Assessment Using Combined Hypo- and Normothermic Machine Perfusion: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidou, E.; Todorov, D.; Katsanos, G.; Antoniadis, N.; Kofinas, A.; Vasileiadou, S.; Karakasi, K.-E.; Tsoulfas, G. AI Innovations in Liver Transplantation: From Big Data to Better Outcomes. Livers 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Starkey, G.; Spano, S.; Chaba, A.; Eastwood, G.; Yoshino, O.; Perini, M.V.; Fink, M.; Bellomo, R.; Jones, R. Perfusate hemoglobin during normothermic liver machine perfusion as biomarker of early allograft dysfunction: A pilot study. Artif. Organs 2025, 49, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergental, H.; Stephenson, B.T.F.; Laing, R.W.; Kirkham, A.J.; Neil, D.A.H.; Wallace, L.L.; Boteon, Y.L.; Widmer, J.; Bhogal, R.H.; Perera, M.T.P.R.; et al. Development of Clinical Criteria for Functional Assessment to Predict Primary Nonfunction of High-Risk Livers Using Normothermic Machine Perfusion. Liver Transplant. 2018, 24, 1453–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.E.; MacDonald, S.; Bridgeman, C.; Brais, R.; Upponi, S.S.; Foukaneli, T.; Swift, L.; Fear, C.; Selves, L.; Kosmoliaptsis, V.; et al. D-dimer Release from Livers During Ex Situ Normothermic Perfusion and after In Situ Normothermic Regional Perfusion: Evidence for Occult Fibrin Burden Associated with Adverse Transplant Outcomes and Cholangiopathy. Transplantation 2023, 107, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piella, G.; Farré, N.; Esono, D.; Cordobés, M.Á.; Vázquez-Corral, J.; Bilbao, I.; Gómez-Gavara, C. LiverColor: An Artificial Intelligence Platform for Liver Graft Assessment. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourounis, G.; Elmahmudi, A.; Thomson, B.; Nandi, R.; Tingle, S.; Glover, E.; Thompson, E.; Mahendran, B.; Connelly, C.; Gibson, B.; et al. Deep learning for automated boundary detection and segmentation in organ donation photography. Innov. Surg. Sci. 2024, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, A.; Nutu, A.; Clarke, G.; Patel, I.; Sneiders, D.; Oo, Y.H.; Hartog, H.; Perera, M.T.P.R. Normothermic Machine Perfusion-Improving the Supply of Transplantable Livers for High-Risk Recipients. Transplant. Int. 2022, 35, 10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.H.; Ceresa, C.D.L.; Hodson, L.; Nasralla, D.; Watson, C.J.E.; Mergental, H.; Coussios, C.; Kaloyirou, F.; Brusby, K.; Mora, A.; et al. Defatting of donor transplant livers during normothermic perfusion—A randomised clinical trial: Study protocol for the DeFat study. Trials 2024, 25, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengu, F.; Abbas, S.H.; Ebeling, G.; Nasralla, D. Normothermic Machine Perfusion (NMP) of the Liver as a Platform for Therapeutic Interventions during Ex-Vivo Liver Preservation: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Nassar, A.; Buccini, L.; Iuppa, G.; Soliman, B.; Pezzati, D.; Hassan, A.; Blum, M.; Baldwin, W.; Bennett, A.; et al. Lipid metabolism and functional assessment of discarded human livers with steatosis undergoing 24 hours of normothermic machine perfusion. Liver Transplant. 2018, 24, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, F.P.; Fuller, B.J.; Davidson, B.R. An Evaluation of Ischaemic Preconditioning as a Method of Reducing Ischaemia Reperfusion Injury in Liver Surgery and Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, A.K.; Feeney, K.; van Leeuwen, L.; Holzner, M.; DiNorcia, J.; Florman, S.; Akhtar, M. Secondary Perfusion: Modeling Viability of Organs Declined for Transplant. Am. J. Transplant. 2025, 25, S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z.; Irizar, A.; Feeney, K.; Van Leeuwen, L.; Weissenbacher, A.; Chang, H.; Holzner, M.; Bagiella, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Schneeberger, S.; et al. Visualizing Graft Performance: Developing an Interactive Registry for Machine Perfusion. In Proceedings of the European Society for Organ Transplantation, London, UK, 29 June–2 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).