Implication of the Androgen Receptor in Muscle–Liver Crosstalk: An Overlooked Mechanistic Link in Lean-MASLD

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Laboratory and Radiological Assessment

2.2. Differential Diagnosis

2.3. Hypothesis and Confirmation of Diagnosis

2.4. Therapeutic and Lifestyle Management

3. An Overview of the Current Literature

3.1. A Brief Overview of Impaired Liver Lipid Metabolism in Hepatic Steatosis

3.2. Sex Disparities in Hepatic Steatosis and Metabolic Dysfunction

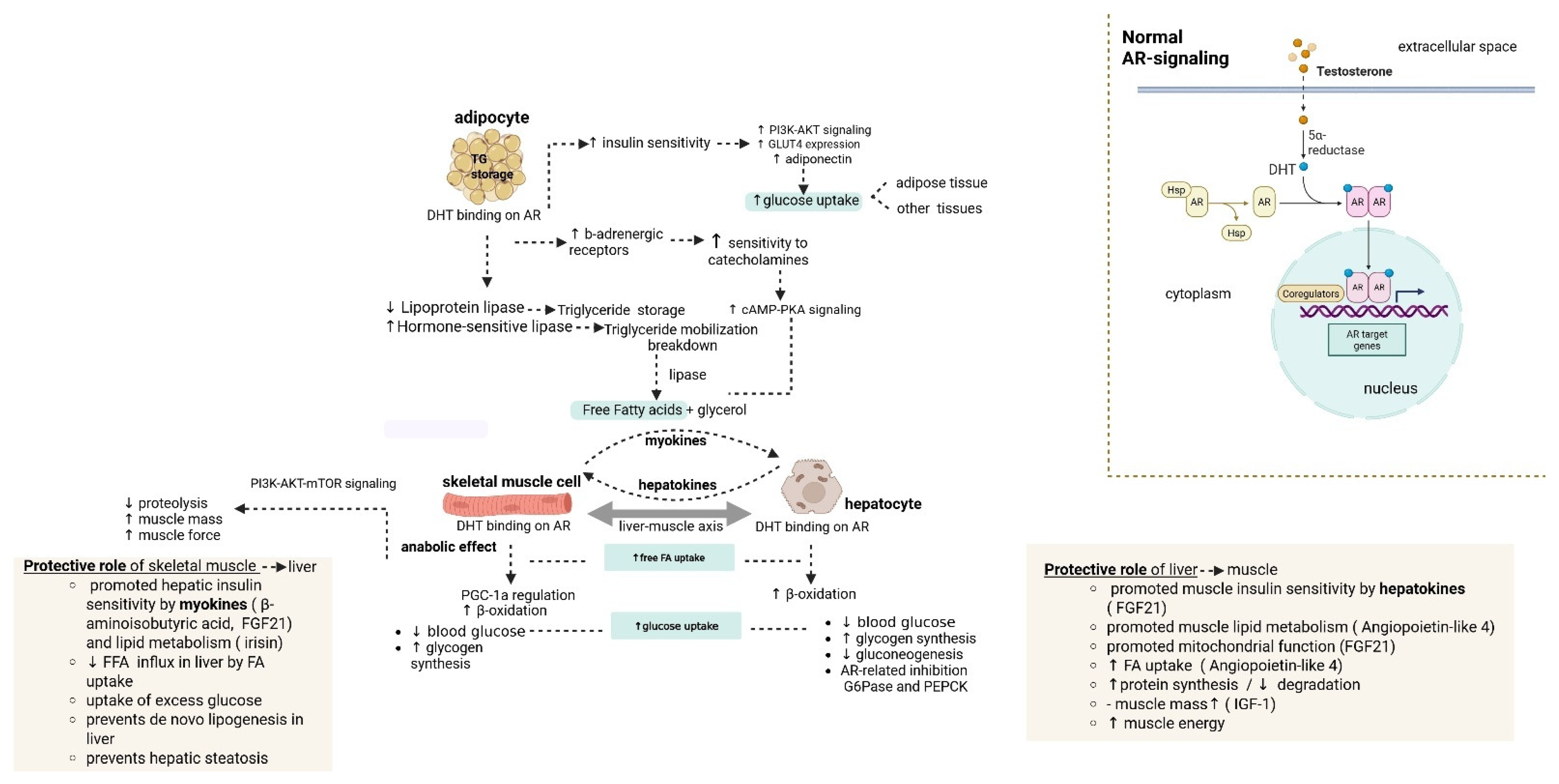

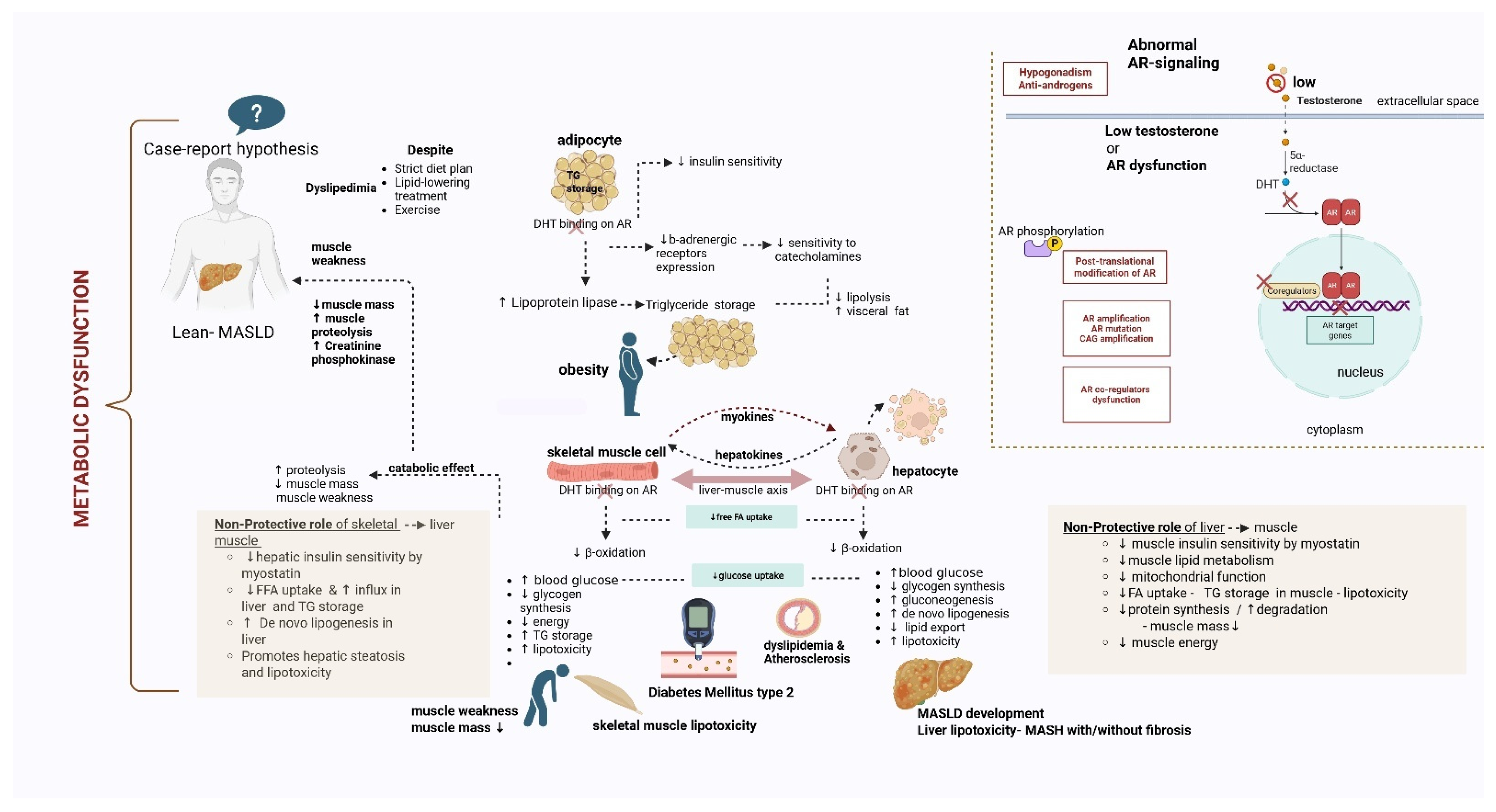

3.3. Implication of AR Dysfunction in the Liver-Muscle Axis

3.4. Types of AR Signaling Dysfunction and Steatosis Development

- AR signaling disruption—low testosterone levels

- AR disruption- AR knockout/loss of function

- AR disruption due to genetic mutation/polymorphism

- AR phosphorylation

3.5. Lean-MASLD Clinical Data

3.6. Genetic Causes of Lean-MASLD

3.7. Non-Genetic Causes of Lean MASLD

3.8. Therapeutic Approaches for AR Dysfunction-Related Hepatic Steatosis

- Androgen replacement therapy (ART) and targeted molecular therapies

3.9. Preclinical Studies

- mTORC1-AR axis blockade: Salinomycin constitutes an antibiotic that serves as a dual-acting inhibitor of AR and mTORC1 in preclinical studies for prostate cancer. This agent effectively suppresses mTORC1 and AR expression (decreased phosphorylation at serine 81), which leads to autophagy stimulation and decreased AR transcriptional activity, respectively. Rapamycin also suppresses mTORC1 and activates autophagy, while suppressing AR via folding impairment (interaction with FKBP51). However, there are no adequate studies for the targeting of the AR-mTOTC1 axis in AR-dysfunction SLD [72,87].

- Liver-specific AR modulators: Liver-specific modulators constitute another potential therapeutic modality that can increase the activity of AR, which can improve the leptin and hepatic insulin sensitivity, leading to lipid and glucose metabolism regulation, respectively [16,35,83]. EP-001, which is a derivative of Bisphenol A diglicycyl ether, acts as an AR receptor suppressor that can potentially reduce hepatic steatosis in mouse models via CYP2E1 inhibition. EP-001 can covalently bind to the activation function-1 region of AR, thereby inducing the interaction between AR protein and its co-regulatory protein, p300/CBP, which is essential for the transcriptional activation of AR. This agent can also be potentially beneficial for MASLD management, due to its modulatory role for peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor (PPAR), which is implicated in lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function in MASLD progression towards HCC development. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that EPI-001 not only blocks fat accumulation in human hepatocytes but also protects mouse hepatocytes from high-fat/high-sucrose diet-induced hepatic steatosis [88].

- Liver-muscle axis modulators: It has been demonstrated that the administration of a β2-adrenoceptor agonist in diet-induced obese animal models (mice) induces an increase in glucose uptake by skeletal muscles, leading to glucose metabolism modification and homeostasis, including the rise in insulin sensitivity, which notably alleviates hepatic steatosis. Clenbuterol has been reported as a promising agent for the improvement of neuromuscular and metabolic functions. However, this agent does not have a direct effect on AR signaling, but it can potentially counteract the effects of AR dysfunction [89]. Likewise, myostatin inhibitors like bimagrumab ameliorate insulin resistance and increase muscle mass, with a potential beneficial effect on hepatic steatosis [90].

- Cilofexor, an FXR agonist, has been tested alone or in combination with other agents in MASH mice models, with a reduction in steatosis and fibrosis [91].

3.10. Clinical Studies

- LPCN 1144: Identification of AR dysfunction could significantly alter disease management, as seen in non-cirrhotic hypogonadal males with MASH, for whom replacement therapy with oral LPCN 1144 (an endogenous testosterone prodrug) could be beneficial for metabolic dysfunction and hepatic steatosis management (clinical trial NCT04134091 [92]).

- Thyroid hormones (THR-βs): THR-βs such as resmetirom can counteract the dysfunction of mitochondrial FA oxidation that is induced by AR signaling dysregulation. THR-βs stimulate liver FA β oxidation and cholesterol/phospholipids excretion into the bile, and have shown significantly beneficial effects for patients, with reduction in MASH and fibrosis [93,94].

- Agents with concomitant favorable effects on the liver-muscle axis:

- ○

- β2-adrenoceptor agonists such as clenbuterol improve glucose uptake in skeletal muscles and alleviate hepatic steatosis. However, they do not directly affect AR signaling [89].

- ○

- Myostatin inhibitors like bimagrumab improve insulin resistance and muscle mass, with potential benefits for hepatic steatosis [90].

Several pharmacological agents can manage the metabolic dysregulation and subsequently lead to the limitation of hepatic steatosis [95], including:- ○

- Glucose-lowering agents and insulin sensitizers: Metformin [96], thiazolidinediones (e.g., pioglitazone) [97], GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide) [98], which have been proved beneficial for insulin sensitivity enhancement, as well as for hepatic steatosis reduction, with the latter being noticeably advantageous for liver fat and inflammation reduction, as well as liver enzyme improvement, without worsening fibrosis [99].

- ○

- Lipid-lowering agents: Statins, ezetimibe, fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids, and PCSK9 inhibitors (e.g., Inclisiran) [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]:Lipid-lowering agents could be beneficial in AR dysfunction; however, they are less effective in comparison to cases without modifications in AR function, due to significantly altered metabolic signaling pathways. Some of the categories of the lipid-lowering pharmacotherapies that could be utilized includes (i) statins (HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors) that reduce LDL cholesterol and have been proved beneficial for liver function, with monitoring of liver enzymes being recommended (ii) ezetimibe, which can be combined with statins, as they significantly suppress intestinal cholesterol absorption and lead to additional LDL lowering, (iii) fibrates and (iv) omega-3 fatty acids for triglycerides reduction, and (v) Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, especially for the cases of statin intolerance. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor (e.g., Inclisiran) is a challenging alternative treatment in those patients [100]. More particularly, Statin-Associated Muscle Symptoms (SAMS) is a persistent issue among patients receiving various statins for lowering LDL-c [101,102]. In this particular case, the patient was previously receiving a statin combined with ezetimibe. PCSK9 is an enzyme secreted by the liver that binds to the receptor of the Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL-R) on hepatocytes. After binding, the PCSK9 leads the LDL-R to its hydrolysis in the cell’s lysosome. This process results in decreased expression of LDL-R on the hepatocytes and consequently in increased levels of LDL-C in the bloodstream [58,59]. Inclisiran is a silencing mRNA/small interfering RNA (siRNA), which blocks the translation of PCSK9 mRNA. Therefore, less PCSK9 means more LDL-R expression on the hepatocyte, hence less LDL-C in the bloodstream [103,104,105,106,107,108,109].

- Other metabolic modulators: Indirect metabolic regulation for hepatic steatosis management has also been in the spotlight of the current research, such as in the case of GLP-1 agonists (e.g., Semaglutide) [110], SCD1 inhibitor (e.g., aramchol) [111], FXR agonists (e.g., Cilofexor or GS-9674) [112], and PPAR pan-agonists α, γ,δ (e.g., lanifibranor) [113] or dual PPARα,δ agonist (e.g., elafibranor) [114], or dual PPARα,γ agonist (e.g., Saroglitazar) [115]. Semaglutide is a widely used agent of the former class that significantly improves hepatic steatohepatitis without worsening fibrosis [110]. In contrast, the second agent has shown a noticeable decrease in hepatic fat by suppressing hepatic lipogenesis and increasing the export of cholesterol from the liver [111]. Cilofexor, a FXR agonist, has been tested alone or in combinations with other agents in MASH mice models, with reduction in steatosis and fibrosis, as well as in non-cirrhotic MASH patients (phase 2 clinical trial NCT02854605), in which a 24-week utilization of Cilofexor led to noticeable reduction in hepatic steatosis, liver enzyme improvements and reduction in serum bile acids in MASH patients [112,116]. Focusing on the latter class, lanifibranor has been studied in MASH patients (phase 3 clinical trial), which improved insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism [113], whereas elafibranor (phase 3 clinical trial) did not meet the primary efficacy endpoints [114]. Meanwhile, Saroglitazar met the primary efficacy end points, including reduction in hepatic steatosis on MRI assessment, improvement of insulin sensitivity, dyslipidemia, and liver enzyme ALT levels in MASH patients [115].

- Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs), such as enobosarm, RAD-140 (testolone), LGD-4033, and S-23, have no role in hepatic steatosis amelioration or hepatic lipid metabolism. At the same time, they can cause drug-induced liver injury and aggravation of metabolic dysfunction [67,68]. More particularly, there is a case report of a 29-year-old male who developed drug-induced liver injury (DILI) after taking RAD-140, with the symptomatology being resolved after drug discontinuation. Likewise, there is another report of a 52-year-old man who also experienced DILI after using RAD-140 and LGD-4033 [116,117].

3.11. Lifestyle Modifications:

4. Methods for Evaluation of AR Signaling Function/Hormonal Profile

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AR | Androgen Receptor |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAP | Controlled Attenuation Parameter |

| CAG | Cytosine-Adenine-Guanine (trinucleotide) |

| CPK | Creatine Phosphokinase |

| ELF | Enhanced Liver Fibrosis |

| FFAs | Free Fatty Acids |

| Glu | Glucose |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 |

| IR | Insulin Resistance |

| KD | Kennedy Disease |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MASH | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 |

| SBMA | Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy |

| SREBP-1c | Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 1c |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| TChoL | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| Th17 | T Helper 17 Cells |

| Treg | T Regulatory Cells |

| TM6SF2 | Transmembrane 6 Superfamily Member 2 |

| PNPLA3 | Patatin-Like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3 |

| UAP | Ultrasound Attenuation Parameter |

| VLDL | Very Low-Density Lipoprotein |

References

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A Multisociety Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, P.; Tatar, M.; Dasarathy, S.; Alkhouri, N.; Herman, W.H.; Taksler, G.B.; Deshpande, A.; Ye, W.; Adekunle, O.A.; McCullough, A.; et al. Estimated Burden of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in US Adults, 2020 to 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2454707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Qi, S.; Zhu, Z. Advances in Mitochondria-Centered Mechanism Behind the Roles of Androgens and Androgen Receptor in the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1267170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A.L.; Tavaglione, F.; Romeo, S.; Charlton, M. Endocrine Aspects of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): Beyond Insulin Resistance. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahmer, N.; Walther, T.C.; Farese, R.V., Jr. The Pathogenesis of Hepatic Steatosis in MASLD: A Lipid Droplet Perspective. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e198334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Goh, G.B. Genetic Risk Factors for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Gut Liver 2025, 19, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, G.C.; Plaga, A.R.; Shankar, E.; Gupta, S. Androgen Receptor-Related Diseases: What Do We Know? Andrology 2016, 4, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujana-Vaquerizo, M.; Bozal-Basterra, L.; Carracedo, A. Metabolic Adaptations in Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Ntansah, A.; Oliver, T.; Lofton, T.; Falzarano, C.; Carr, K.; Huang, R.; Wilson, A.; Damaser, E.; Harvey, G.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Liver Androgen Receptor Knockout Improved High-Fat Diet–Induced Glucose Dysregulation in Female Mice but Not Male Mice. J. Endocr. Soc. 2024, 8, bvae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, X.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, F.; Yu, N.; Li, D.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; et al. Unique Genetic Variants of Lean Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Endocr. Disorders 2023, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Horn, P.; Wong, V.W.; Ratziu, V.; Bugianesi, E.; Francque, S.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Valenti, L.; Roden, M.; Schick, F.; et al. EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattacheril, J.J.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Lim, J.K.; Sanyal, A.J. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, B. Muscle Diseases of Metabolic and Endocrine Derivation. Rheumato 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini-Pesenti, F.; Vitturi, N.; Tresso, S.; Sorarù, G. Metabolic Alterations in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy’s Disease Association. What Is Kennedy’s Disease. Kennedy’s Disease Association (KDA) Website. Available online: https://kennedysdisease.org/living-with-kd/what-is-kennedys-disease/what-is-kd.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Pradat, P.F.; Bernard, E.; Corcia, P.; Couratier, P.; Jublanc, C.; Querin, G.; Morélot Panzini, C.; Salachas, F.; Vial, C.; Wahbi, K.; et al. The French National Protocol for Kennedy’s Disease (SBMA): Consensus Diagnostic and Management Recommendations. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, E.; Patil, V.K. Neuromuscular Complications of Statin Therapy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, F.; Eidam, A.; Michael, L.; Bauer, J.M.; Haefeli, W.E. Drug Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia in Older Adults: Focus on Newer Agents. Drugs Aging 2022, 39, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugs.com. Drug Interaction Checker. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/interactions-check.php?drug_list=1062-0,4328-0,1749-15695&professional=1 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Sun, L.; Wolska, A.; Amar, M.; Zubirán, R.; Remaley, A.T. Approach to the Patient with a Suboptimal Statin Response: Causes and Algorithm for Clinical Management. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2424–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, F.; Moscucci, F.; Lospinuso, I.; Cocomello, N.; Colantoni, A.; Di Costanzo, A.; Tramontano, D.; D’Erasmo, L.; Pastori, D.; Ettorre, E.; et al. Lipid-Lowering Therapy and Cardiovascular Prevention in Elderly. Drugs 2025, 85, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, D.; Sabadini, R.; Ferlini, A.; Torrente, I. Epidemiological Survey of X-Linked Bulbar and Spinal Muscular Atrophy, or Kennedy Disease, in the Province of Reggio Emilia, Italy. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 17, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Kennedy Disease. Available online: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6818/kennedy-disease (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Carli, F.; Della Pepa, G.; Sabatini, S.; Vidal Puig, A.; Gastaldelli, A. Lipid Metabolism in MASLD and MASH: From Mechanism to the Clinic. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, S.K.; Kim, W. Sex Differences in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Ewha Med. J. 2024, 47, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherubini, A.; Della Torre, S.; Pelusi, S.; Valenti, L. Sexual Dimorphism of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duric, L.F.; Belčić, V.; Oberiter Korbar, A.; Ćurković, S.; Vujicic, B.; Gulin, T.; Muslim, J.; Gulin, M.; Grgurević, M.; Catic Cuti, E. The Role of SHBG as a Marker in Male Patients with Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: Insights into Metabolic and Hormonal Status. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.-Y.; Lyu, J.-Q.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Chen, G.-C. Sex-specific associations of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease with cardiovascular outcomes. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, e35–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, L. Association of metabolic-dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease with polycystic ovary syndrome. iScience 2024, 27, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Armstrong, M.J.; Stine, J.G. Skeletal Muscle and MASLD: Mechanistic and Clinical Insights. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y.; Gao, X.; et al. Metabolic Crosstalk between Skeletal Muscle Cells and Liver through IRF4-FSTL1 in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Imai, Y. Cell-Specific Functions of Androgen Receptor in Skeletal Muscles. Endocr. J. 2024, 71, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaibour, K.; Duteil, D.; Metzger, D. Androgen Receptor Coordinates Muscle Metabolic and Contractile Functions. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1707–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooge, S.; Shrestha, N. Editorial: Lipid Metabolism in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1584932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Yu, I.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; Altuwaijri, S.; Hsu, C.; Ma, W.; Jokinen, J.; Sparks, J.D.; et al. Increased Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Mice Lacking Hepatic Androgen Receptor. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1924–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pergola, G. The Adipose Tissue Metabolism: Role of Testosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24 (Suppl. 2), S59–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colantoni, A.; Bucci, T.; Cocomello, N.; Angelico, F.; Ettorre, E.; Pastori, D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Del Ben, M.; Baratta, F. Lipid-Based Insulin-Resistance Markers Predict Cardiovascular Events in Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe-Grau, A.; Rodríguez-González, F.G.; Dorado, C.; Olmedillas, H.; Fuentes, T.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Delgado-Guerra, S.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; Calbet, J.A.L. Androgen Receptor Gene Polymorphisms, Lean Mass, and Performance in Young Men. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, M.V.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Forsgren, M.F.; Sanyal, A.J. Harnessing Muscle-Liver Crosstalk to Treat Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 592373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumond Bourie, A.; Potier, J.-B.; Pinget, M.; Bouzakri, K. Myokines: Crosstalk and Consequences on Liver Physiopathology. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Li, M.; Yao, T.; Hu, G.; Wan, G.; Chang, B. Signaling Metabolite β-Aminoisobutyric Acid as a Metabolic Regulator, Biomarker, and Potential Exercise Pill. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1192458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Cui, A.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H.; Gao, J.; Chen, X.; Han, Y.; Liang, Q.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Improves Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity by Inhibiting Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 in Mice. Hepatology 2016, 64, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciałowicz, M.; Woźniewski, M.; Murawska-Ciałowicz, E.; Dzięgiel, P. The Influence of Irisin on Selected Organs—The Liver, Kidneys, and Lungs: The Role of Physical Exercise. Cells 2025, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolini, G.; Atorrasagasti, C.; Onorato, A.; Peixoto, E.; Schlattjan, M.; Sowa, J.-P.; Sydor, S.; Gerken, G.; Canbay, A. SPARC Expression Is Associated with Hepatic Injury in Rodents and Humans with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, E.; Atorrasagasti, C.; Malvicini, M.; Fiore, E.; Rodriguez, M.; Garcia, M.; Finocchieto, P.; Poderoso, J.J.; Corrales, F.; Mazzolini, G. SPARC gene deletion protects against toxic liver injury and is associated to an enhanced proliferative capacity and reduced oxidative stress response. Oncotarget 2016, 10, 4169–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Genzer, Y.; Chapnik, N.; Froy, O. Effect of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) on Hepatocyte Metabolism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 88, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertholdt, L.; Gudiksen, A.; Jessen, H.; Pilegaard, H. Impact of Skeletal Muscle IL-6 on Regulation of Liver and Adipose Tissue Metabolism during Fasting. Pflugers Arch. 2018, 470, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeau, L.; Patten, D.A.; Caron, A.; Garneau, L.; Pinault-Masson, E.; Foretz, M.; Haddad, P.; Anderson, B.G.; Quinn, L.S.; Jardine, K.; et al. IL-15 Improves Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Metabolism and Glucose Uptake in Association with Increased Respiratory Chain Supercomplex Formation and AMPK Pathway Activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheptulina, A.F.; Mamutova, E.M.; Elkina, A.Y.; Timofeev, Y.S.; Metelskaya, V.A.; Kiselev, A.R.; Drapkina, O.M. Serum Irisin, Myostatin, and Myonectin Correlate with Metabolic Health Markers, Liver Disease Progression, and Blood Pressure in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Hypertension. Metabolites 2024, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.A.; Nolte, L.A.; Chen, M.M.; Holloszy, J.O. Increased GLUT-4 Translocation Mediates Enhanced Insulin Sensitivity of Muscle Glucose Transport after Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Zhao, H.; Liao, J. Androgen Interacts with Exercise through the mTOR Pathway to Induce Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy. Biol. Sport 2017, 34, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S. Role and Mechanism of the Action of Angiopoietin-Like Protein ANGPTL4 in Plasma Lipid Metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanthier, N.; Lebrun, V.; Molendi-Coste, O.; van Rooijen, N.; Leclercq, I.A. Liver Fetuin-A at Initiation of Insulin Resistance. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misu, H.; Takamura, T.; Takayama, H.; Hayashi, H.; Matsuzawa-Nagata, N.; Kurita, S.; Ishikura, K.; Ando, H.; Takeshita, Y.; Ota, T.; et al. A Liver-Derived Secretory Protein, Selenoprotein P, Causes Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Kawtharany, H.; Awali, M.; Mahmoud, N.; Mohamed, I.; Syn, W.-K. The Effects of Testosterone Replacement Therapy in Adult Men With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2025, 16, e00787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.M.; Akhtar, S.; Sellers, D.J.; Muraleedharan, V.; Channer, K.S.; Jones, T.H. Testosterone differentially regulates targets of lipid and glucose metabolism in liver, muscle, and adipose tissues of the testicular feminised mouse. Endocrine 2016, 54, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.J.; Choi, J.Y. Androgen Dysfunction in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Role of Sex Hormone Binding Globulin. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1053709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, G.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; An, K.; He, H.; Fu, X.; Li, S.; An, Z. Unmasking the Enigma of Lipid Metabolism in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: From Mechanism to the Clinic. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1294267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaou, N.; Nasiri, M.; Gathercole, L.; Parajes Castro, S.; Krone, N.; Valsamakis, G.; Mastorakos, G.; Tomlinson, J.W. Androgen Receptor Overexpression Drives Lipid Accumulation in Human Hepatocytes. Endocr. Abstr. 2014, 34, P363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lin, X.; Wang, G. Targeting SREBP-1-Mediated Lipogenesis as Potential Strategies for Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 952371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, B.; Trifiro, M.A. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, 1999; Updated 11 May 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1429/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Ciarloni, A.; delli Muti, N.; Ambo, N.; Perrone, M.; Rossi, S.; Sacco, S.; Salvio, G.; Balercia, G. Contribution of Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Polymorphism to Human Reproduction. DNA 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Bae, Y.D.; Ahn, S.T.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.J.; Moon, D.G. Positive Correlation between Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Length and Metabolic Syndrome in a Korean Male Population. World J. Mens Health 2018, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagman, J.B.; Wilhelmson, A.S.; Motta, B.M.; Pirazzi, C.; Alexanderson, C.; De Gendt, K.; Verhoeven, G.; Holmäng, A.; Anesten, F.; Jansson, J.O.; et al. The Androgen Receptor Confers Protection against Diet-Induced Atherosclerosis, Obesity, and Dyslipidemia in Female Mice. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gang, X.; Yang, S.; Cui, M.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, G. The Alterations in and the Role of the Th17/Treg Balance in Metabolic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 678355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbohm, A.; Hirsch, S.; Volk, A.E.; Grehl, T.; Grosskreutz, J.; Hanisch, F.; Herrmann, A.; Kollewe, K.; Kress, W.; Meyer, T.; et al. The Metabolic and Endocrine Characteristics in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. Mitochondrial Metabolic Dysfunction and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: New Insights from Pathogenic Mechanisms to Clinically Targeted Therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves-Bezerra, M.; Cohen, D.E. Triglyceride Metabolism in the Liver. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini-Pesenti, F.; Cacciavillani, M.; Sorarù, G.; Zanette, G.; Angelini, C. Metabolic Alterations in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (Kennedy Disease). Muscle Nerve 2020, 62, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Newell-Fugate, A.E. Role of Androgens and Androgen Receptor in Control of Mitochondrial Function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 323, C835–C846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Cai, Z.; Yu, C. Androgen Excess Induced Mitochondrial Abnormality in Ovarian Granulosa Cells in a Rat Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 789008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.N.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C.Y.; Zhou, Y.F.; Yang, X.F.; Long, J.W.; Li, X.X.; Mai, S.J.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zhang, H.Z.; et al. Phosphorylation of Androgen Receptor by mTORC1 Promotes Liver Steatosis and Tumorigenesis. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Fan, J.; Abu-Zaid, A.; Burley, S.K.; Zheng, X.F.S. Nuclear mTOR Signaling Orchestrates Transcriptional Programs Underlying Cellular Growth and Metabolism. Cells 2024, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P.; Koc, E.; Sonpavde, G.; Singh, R.; Singh, K.K. Mitochondrial Localization, Import, and Mitochondrial Function of the Androgen Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6621–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifylli, E.M.; Fortis, S.P.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Papadopoulos, N.; Koustas, E.; Sarantis, P.; Manolakopoulos, S.; Deutsch, M. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Chronic Hepatobiliary Diseases: An Overview of Their Interplay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Suparan, K.; Kim, D.; Wijarnpreecha, K. What Is New in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Lean Individuals: From Bench to Bedside. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Han, E.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, M.K.; Wong, V.W.; Sinn, D.H. Cardiovascular Risk Is Elevated in Lean Subjects with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.H.; Peddu, D.; Amin, S.; Elsaid, M.I.; Minacapelli, C.D.; Chandler, T.M.; Catalano, C.; Rustgi, V.K. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Lean/Nonobese and Obese Individuals: A Comprehensive Review on Prevalence, Pathogenesis, Clinical Outcomes, and Treatment. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Tariq, R.; Provenza, J.; Satapathy, S.K.; Faisal, K.; Choudhry, A.; Friedman, S.L.; Singal, A.K. Prevalence and Profile of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Lean Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-W.; Lin, M.-R.; Chou, W.-H.; Wan, Y.-J.Y.; Kao, W.-Y.; Chang, W.-C. Cross-ancestry Discovery of Genetic Risk Variants for Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shima, T.; Iwaki, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kawanaka, M.; Tanaka, S.; Mitsumoto, Y.; Yoneda, M.; Nakajima, A.; et al. Differential Effects of Genetic Polymorphism on Comorbid Disease in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1436–1443.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaru, A.; Stafie, R.; Stratina, E.; Zenovia, S.; Nastasa, R.; Minea, H.; Huiban, L.; Cuciureanu, T.; Muzica, C.; Chiriac, S.; et al. Lean MASLD and IBD: Exploring the Intersection of Metabolic Dysfunction and the Gut–Liver Axis. Life 2025, 15, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolov, R.; Gianatti, E.; Wong, D.; Kutaiba, N.; Gow, P.; Grossmann, M.; Sinclair, M. Testosterone therapy reduces hepatic steatosis in men with type 2 diabetes and low serum testosterone concentrations. World J. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudimat, A.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; Yassin, A.A.; Alwani, M.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; AlRumaihi, K.; Talib, R.; Al Ansari, A. Testosterone Treatment Improves Liver Function and Reduces Cardiovascular Risk: A Long-Term Prospective Study. Arab J. Urol. 2021, 19, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourshafie, N.; Lee, P.R.; Chen, J.; Rao, A.; Sah, M.; Wang, J.; Rosenberg, M.I.; Cortes, C.J.; La Spada, A.R. MiR-298 Regulates the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer and Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy Models. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östling, P.; Leivonen, S.K.; Aakula, A.; Kohonen, P.; Mäkelä, R.; Hagman, Z.; Edsjö, A.; Kangaspeska, S.; Edgren, H.; Nicorici, D.; et al. Systematic Analysis of MicroRNAs Targeting the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Doe, A. Rapamycin Ameliorates Intrahepatic Inflammation in MASLD by Modulating AR Pathway. J. Hepat. Biol. 2025, 12, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xu, W.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Li, G.; Pan, Q.; Chen, K. Amelioration of Hepatic Steatosis by the Androgen Receptor Inhibitor EPI-001 in Mice and Human Hepatic Cells Is Associated with the Inhibition of CYP2E1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinovich, A.; Dehvari, N.; Åslund, A.; van Beek, S.; Halleskog, C.; Olsen, J.; Forsberg, E.; Zacharewicz, E.; Schaart, G.; Rinde, M.; et al. Treatment with a β-2-Adrenoceptor Agonist Stimulates Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle and Improves Glucose Homeostasis, Insulin Resistance, and Hepatic Steatosis in Mice with Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1603–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Coleman, L.A.; Miller, R.; Rooks, D.S.; Laurent, D.; Petricoul, O.; Praestgaard, J.; Swan, T.; Wade, T.; Perry, R.G.; et al. Effect of Bimagrumab vs Placebo on Body Fat Mass among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2033457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Hambruch, E.; Budas, G.R.; Supper, P.; Burnet, M.; Liles, J.T.; Birkel, M.; Brusilovskaya, K.; Königshofer, P.; Peck-Radosavljevic, M.; et al. The Non-Steroidal FXR Agonist Cilofexor Improves Portal Hypertension and Reduces Hepatic Fibrosis in a Rat NASH Model. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lbhaisi, S.; Kim, K.; Baker, J.; Chidambaram, N.; Patel, M.V.; Charlton, M.; Sanyal, A.J. LPCN 1144 Resolves NAFLD in Hypogonadal Males. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, R.; Shetty, S.; Pappachan, J.M. Efficacy and Safety of Resmetirom, a Selective Thyroid Hormone Receptor-β Agonist, in the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lau, H.C.-H.; Yu, J. Pharmacological Treatment for Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Related Disorders: Current and Emerging Therapeutic Options. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.E. A New Treatment and Updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for MASLD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X. Metformin’s Effect on Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Insights from Animal Models and Human Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1477212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, D.; Shimizu, S.; Haisa, A.; Yanagisawa, S.; Inoue, K.; Saito, D.; Sumita, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Uchida, Y.; Inukai, K.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Ipragliflozin and Pioglitazone on Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: 5-Year Observational Follow-Up of a Randomized, 24-Week, Active-Controlled Trial. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Newsome, P.N.; Kliers, I.; Østergaard, L.H.; Long, M.T.; Kjær, M.S.; Cali, A.M.G.; Bugianesi, E.; Rinella, M.E.; Roden, M.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2089–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakal, T.C.; Xiao, F.; Bhusal, C.K.; Sabapathy, P.C.; Segal, R.; Chen, J.; Bai, X. Lipids Dysregulation in Diseases: Core Concepts, Targets and Treatment Strategies. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Baker, S.K.; Jacobson, T.A.; Kopecky, S.L.; Parker, B.A.; The National Lipid Association’s Muscle Safety Expert Panel. An Assessment by the Statin Muscle Safety Task Force: 2014 Update. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2014, 8 (Suppl. 3), S58–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Baker, S.; Banach, M.; Borow, K.M.; Braun, L.T.; Bruckert, E.; Brunham, L.R.; Catapano, A.L.; Elam, M.B.; Mancini, G.B.J.; et al. Optimizing Cholesterol Treatment in Patients with Muscle Complaints. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaíz, Á.R.; Gudino, L.C.; de la Isla, L.P.; Pardo, H.G.; Calle, D.G.; Miramontes-González, J.P. Inclisiran: Efficacy in Real World—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Troquay, R.P.T.; Visseren, F.L.J.; Leiter, L.A.; Scott Wright, R.; Vikarunnessa, S.; Talloczy, Z.; Zang, X.; Maheux, P.; Lesogor, A.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Inclisiran in Patients with High Cardiovascular Risk and Elevated LDL Cholesterol (ORION-3): Results from the 4-Year Open-Label Extension of the ORION-1 Trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Wright, R.S.; Kallend, D.; Koenig, W.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; Bisch, J.A.; Richardson, T.; Jaros, M.; Wijngaard, P.L.J.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Inclisiran in Patients with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Kallend, D.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; Koenig, W.; Jaros, M.J.; Schwartz, G.G.; Landmesser, U.; Garcia Conde, L.; Wright, R.S.; et al. Effect of Inclisiran on Lipids in Primary Prevention: The ORION-11 Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 5047–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.W.; Lagace, T.A.; Garuti, R.; Zhao, Z.; McDonald, M.; Horton, J.D.; Cohen, J.C.; Hobbs, H.H. Binding of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 to Epidermal Growth Factor-Like Repeat A of Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Decreases Receptor Recycling and Increases Degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 18602–18612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Surdo, P.; Bottomley, M.J.; Calzetta, A.; Settembre, E.C.; Cirillo, A.; Pandit, S.; Ni, Y.G.; Hubbard, B.; Sitlani, A.; Carfí, A. Mechanistic Implications for LDL Receptor Degradation from the PCSK9/LDLR Structure at Neutral pH. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, J.; Wu, J.; Dong, Y.; Lv, J. Inclisiran in Cardiovascular Health: A Review of Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Future Prospects. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e946439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, J.C.; Anderson, S.L. Inclisiran for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolaemia. Drugs Context 2024, 13, 2023-12-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Armstrong, M.J.; Jara, M.; Kjær, M.S.; Krarup, N.; Lawitz, E.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg Once Weekly in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis-Related Cirrhosis: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safadi, R.; Konikoff, F.M.; Mahamid, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Halpern, M.; Gilat, T.; Oren, R.; FLORA Group. The Fatty Acid–Bile Acid Conjugate Aramchol Reduces Liver Fat Content in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 2085–2091.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddin, M.; Djedjos, C.S.; Harrison, S.A.; Billin, A.N.; Subramanian, G.M.; Myers, R.P.; Rojter, S.E.; Trotter, J.F.; Gane, E.J.; Wong, V.W.; et al. Cilofexor, a Nonsteroidal FXR Agonist, in Patients with Noncirrhotic NASH: A Phase 2 Randomized Controlled Trial. Hepatology 2020, 72, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francque, S.M.; Bedossa, P.; Ratziu, V.; Anstee, Q.M.; Bugianesi, E.; Sanyal, A.J.; Loomba, R.; Harrison, S.A.; Balabanska, R.; Mateva, L.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Pan-PPAR Agonist Lanifibranor in NASH. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Harrison, S.A.; Francque, S.; Bedossa, P.; Lehert, P.; Serfaty, L.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Boursier, J.; Abdelmalek, M.; Caldwell, S.; et al. Elafibranor, an Agonist of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-α and -δ, Induces Resolution of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Without Fibrosis Worsening. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1147–1159.e5, Erratum: Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, O.; Nohria, S.; Goyal, P.; Kaur, J.; Sharma, S.; Sood, A.; Chhina, R.S. Saroglitazar in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Diabetic Dyslipidemia: A Prospective, Observational, Real World Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiani, G.; Patel, K.; Ratziu, V.; Feld, J.J.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Pinzani, M.; Petta, S.; Berzigotti, A.; Metrakos, P.; Shoukry, N.; et al. Current considerations for clinical management and care of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Insights from the 1st International Workshop of the Canadian NASH Network (CanNASH). Can. Liver J. 2022, 5, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demangone, M.R.; Abi Karam, K.R.; Li, J. Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators Leading to Liver Injury: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e67958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malave, B. Metabolic and Hormonal Dysfunction in an Asymptomatic Patient Using Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators: A Case Report. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2023, 47, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuppia, L.; Gatta, V.; Antonucci, I. Use of the MLPA Assay in the Molecular Diagnosis of Gene Copy Number Alterations in Human Genetic Diseases. J. Mol. Diagn. 2012, 14, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Spada, A.R.; Wilson, E.M.; Lubahn, D.B.; Harding, A.E.; Fischbeck, K.H. Androgen Receptor Gene Mutations in X-Linked Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Nature 1991, 352, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, T.; Sommer, U.; Beier, A.K.; Stope, M.B.; Borkowetz, A.; Thomas, C.; Erb, H.H.H. The Androgen Hormone-Induced Increase in Androgen Receptor Protein Expression Is Caused by the Autoinduction of the Androgen Receptor Translational Activity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmuth, E.V.; Olsen, L.R.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Johnson, D.S. Mechanisms of Androgen Receptor DNA Binding and Regulation Revealed by ChIP-Seq and Functional Genomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020, 117, 9050–9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshan, N.G.R.D.; Rettig, M.B.; Jung, M.E. Molecules Targeting the Androgen Receptor (AR) Signaling Axis Beyond the AR-Ligand Binding Domain. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 910–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużewski, T.; Pinkier, I.; Wysocka, U.; Sałamunia, J.; Kępczyński, Ł.; Piotrowicz, M.; Kałużewski, B.; Gach, A. Expanding the Molecular Landscape of Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Through Next-Generation Sequencing. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2024, 17, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltunen, J.; Helminen, L.; Aaltonen, N.; Launonen, K.M.; Laakso, H.; Malinen, M.; Niskanen, E.A.; Palvimo, J.J.; Paakinaho, V. Androgen Receptor-Mediated Assisted Loading of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulates Transcriptional Responses in Prostate Cancer Cells. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempiäinen, J.K.; Niskanen, E.A.; Vuoti, K.M.; Lampinen, R.E.; Göös, H.; Varjosalo, M.; Palvimo, J.J. Agonist-Specific Protein Interactomes of Glucocorticoid and Androgen Receptor as Revealed by Proximity Mapping. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2017, 16, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, T. N-Terminal Domain of Androgen Receptor Is a Major Therapeutic Barrier and Potential Pharmacological Target for Treating Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1451957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandireddy, R.; Sakthivel, S.; Gupta, P.; Behari, J.; Tripathi, M.; Singh, B.K. Systemic Impacts of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) on Heart, Muscle, and Kidney-Related Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1433857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBartolo, D.; Arnold, F.J.; Liu, Y.; Molotsky, E.; Tang, H.Y.; Merry, D.E. Differentially Disrupted Spinal Cord and Muscle Energy Metabolism in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e178048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsuta, N.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, M.; Banno, H.; Suzuki, K.; Katsuno, M.; Tanaka, F.; Tamakoshi, A.; Sobue, G. Natural History of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (SBMA): A Study of 223 Japanese Patients. Brain 2006, 129, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, W.R.; Alter, M.; Sung, J.H. Progressive Proximal Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy of Late Onset. Neurology 1968, 18, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effah, W.; Khalil, M.; Hwang, D.J.; Miller, D.D.; Narayanan, R. Advances in the Understanding of Androgen Receptor Structure and Function and in the Development of Next-Generation AR-Targeted Therapeutics. Steroids 2024, 210, 109486, Erratum: Steroids 2025, 221, 109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, J.N.; Joel, M.M.; Martens, K.; King, A.; King, M.; Korngut, L.W.; de Koning, A.P.J.; Pfeffer, G.; Schellenberg, K.L. Highly Elevated Prevalence of Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy in Indigenous Communities in Canada Due to a Founder Effect. Neurol. Genet. 2021, 7, e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breza, M.; Koutsis, G.; Kladi, A.; Karadima, G.; Panas, M.; Neurogenetics Unit, 1st Department of Neurology, “Aiginiteio” Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy (Kennedy’s Disease) in the Greek Population. Arch. Hellenic Med. 2017, 34, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Querin, G.; Bertolin, C.; Da Re, E.; Volpe, M.; Zara, G.; Pegoraro, E. Non-Neural Phenotype of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy: Results from a Large Cohort of Italian Patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guber, R.D.; Takyar, V.; Kokkinis, A.; Fox, D.A.; Alao, H.; Kats, I.; Bakar, D.; Remaley, A.T.; Hewitt, S.M.; Kleiner, D.E.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Neurology 2017, 89, 2481–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbohm, A.; Peter, R.S.; Erhardt, S.; Lulé, D.; Rothenbacher, D.; Ludolph, A.C.; Nagel, G.; ALS Registry Study Group. Epidemiology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Southern Germany. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, H.; Araki, A.; Hashizume, A.; Hijikata, Y.; Yamada, S.; Inagaki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Banno, H.; Suga, N.; Okada, Y.; et al. Correlation of Insulin Resistance and Motor Function in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francini-Pesenti, F.; Querin, G.; Martini, C.; Mareso, S.; Sacerdoti, D. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Cohort of Italian Patients with Spinal Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Acta Myol. 2018, 37, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Suparan, K.; Prasitsumrit, V.; Ahmed, A.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Kim, D. Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Modifiers of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Between Lean and Non-Lean Populations. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Xie, J.; Xiao, S.; Li, W.; Liu, N. Efficacy and Safety of PCSK9 Inhibitors in Patients with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simancas-Racines, D.; Annunziata, G.; Verde, L.; Fascì-Spurio, F.; Reytor-González, C.; Muscogiuri, G.; Frias-Toral, E.; Barrea, L. Nutritional Strategies for Battling Obesity-Linked Liver Disease: The Role of Medical Nutritional Therapy in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) Management. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Ide, T.; Shimano, H.; Yahagi, N.; Amemiya-Kudo, M.; Matsuzaka, T.; Yatoh, S.; Kitamine, T.; Okazaki, H.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Cross-Talk Between Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) α and Liver X Receptor (LXR) in Nutritional Regulation of Fatty Acid Metabolism. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdul Razzak, I.; Fares, A.; Stine, J.G.; Trivedi, H.D. The Role of Exercise in Steatotic Liver Diseases: An Updated Perspective. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e16220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Lazarus, J.V.; Wong, V.W.; Yilmaz, Y.; Duseja, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Castera, L.; Pessoa, M.G.; Oliveira, C.P.; et al. Global Consensus Recommendations for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 1017–1032.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, W.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.H.; Jin, Y.J.; Kim, G.A.; Sung, P.S.; Yoo, J.J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, E.J.; et al. KASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease 2025. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, S1–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Category | Test/Investigation | Time of Diagnosis Result | Post-Treatment Modification | Reference Range/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Function Tests | Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 122 IU/L | 56 IU/L | 7–56 IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 80 IU/L | 39 IU/L | 5–40 IU/L | |

| Lipid Profile | Triglycerides | 443 mg/dL | 116 mg/dL | <150 mg/dL |

| Total Cholesterol | 209 mg/dL | 171 mg/dL | <200 mg/dL | |

| LDL-C | 97 mg/dL | 104 mg/dL | <100 mg/dL | |

| HDL-C | 43 mg/dL | 45 mg/dL | >40 mg/dL | |

| Glucose Metabolism | Fasting Glucose | 90 mg/dL | 98 mg/dL | 70–100 mg/dL |

| Muscle Enzymes | Creatine Phosphokinase (CPK) | 1163 IU/L | 560 IU/L | 30–200 IU/L |

| Genetic Testing (qPCR/NGS) | AR gene CAG repeat expansion | >38 repeats in exon 1 | Consistent with Kennedy’s Disease | |

| Viral Hepatitis Screening | Hepatitis B, C, HIV, CMV, EBV, HSV | Negative | ||

| Autoimmune/Metabolic Exclusion Tests | Wilson’s disease, Hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Autoimmune hepatitis | Negative | ||

| Ceruloplasmin/a1-antitrypsin | Within normal range | |||

| TM6SF2, PNPLA3 polymorphisms | Negative | |||

| Complementary hormonal testing | Testosterone, LH, FSH, TSH | Within normal range | Within normal range | |

| Total Blood Count | White/Red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, Platelets | Within normal range | Within normal range | |

| C-reactive protein/ESR | CRP: Normal (<5 mg/L) in most labs. ESR: Normal (<20 mm/h in men) | |||

| Imaging | Abdominal Ultrasound | Mild hepatic steatosis | ||

| Transient Elastography | Liver stiffness: 5.27 kPa (F1) | F0–F4 staging | ||

| Neurological examination | Exclusion of common myopathies |

| Signaling Molecule | Source | Role in Muscle/Liver | Protective/Non-Protective |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGF21 | Liver | Increased glucose uptake Increased fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial function Increased muscle insulin sensitivity | Protective |

| IGF-1/activin E | Liver | Increased muscle protein synthesis and muscle mass Decreased protein degradation | Protective |

| Angptl4 | Liver | Regulation of lipid metabolism Increased fatty acid uptake and oxidation | Protective |

| Selenoprotein P | |||

| Fetuin-A | Liver | Decreased insulin sensitivity in the muscle | Non-Protective |

| β-aminoisobutyric acid FGF21 | Muscle | Increased hepatic insulin sensitivity/lipid metabolism | Protective |

| SPARC | Muscle | Increased liver metabolism Prevents fibrotic injury Reduction in liver fibrosis | Protective |

| Irisin | Muscle | Improved lipid metabolism in the liver Prevention of hepatic steatosis development Increased hepatic insulin sensitivity | Protective |

| BDNF | Muscle | Increased hepatic glucose metabolism Prevention against liver injury | Protective |

| IL-6 | Muscle | Secreted during exercise and promotes hepatic glucose production versus chronic elevation (non-protective) | Protective (acute elevation) Non-protective (chronic elevation) |

| IL-15 | Muscle | Increased hepatic lipid metabolism | Protective |

| Myostatin | Muscle | Decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity Promotes hepatic steatosis | Non-Protective |

| TNF-a | Muscle | Promotes hepatic steatosis and lipotoxicity Decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity | Non-Protective |

| Effects of AR dysfunction | Consequence |

|---|---|

| ↑ de novo lipogenesis—↑ activity of lipogenic genes (ACC1, SREBP-1c, and FASN) [16,58,59,61] | ↑ Triglyceride storage in liver parenchyma |

| ↓ Fatty acid oxidation [67,68,69,70,71,74] | ↑ Lipid accumulation in liver parenchyma ↑ triglycerides storage in hepatocytes |

| ↑Hepatic Insulin resistance [16,58,59,60,61] | ↑ Lipid accumulation and ↑ inflammation ↑ de novo lipogenesis and ↓ fat export ↑ Inflammatory cytokines promote MASH |

| AR phosphorylation by mTORC1 [72,73] | ↑ de novo lipogenesis, hepatocarcinogenesis (HCC development) |

| ↓ mitochondrial activity [70,74] | ↑ Lipid accumulation via suppression of fatty acid breakdown |

| ↑ androgens in females (PCOS, obesity/T2DM independent) [71] | ↑ de novo lipogenesis |

| Category | Types | Mechanism/Effects/Epidemiology |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Factors | PNPLA3 (I148M variant) | TG accumulation and inflammation Most common among other genetic factors for lean MASLD Epidemiology: Latin America (50–63%) > East Asia (35–45%) > South Asia (24–30%) < Europe (23–38%) > Sub-Saharan Africa (12%) |

| MBOAT7 polymorphisms | Subjects are prone to steatosis and fibrosis development, modified phospholipid remodeling mechanism Higher frequency in Europe and lowest in East Asia Altered phospholipid remodeling → increased susceptibility to steatosis and fibrosis. | |

| TM6SF2 (E167K variant) | Altered VLDL secretion; steatosis despite the lean phenotype Uncommon genetic variant. | |

| GCKR (P446L variant) | Increased hepatic glucose uptake and DNL Patients with this variant usually have lower fasting plasma glucose, higher TG, Decreased risk of T2DM | |

| Other loci: APOC3, LYPLAL1 | Modified lipid metabolism and intrahepatic fat accumulation Moderate effects | |

| Non-Genetic Factors | Ethnicity | Asians have a higher prevalence |

| High intake of carbohydrates | Increased glucose uptake by the liver and DNL, irrespective of lean phenotype | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | Reduced insulin sensitivity and steatosis development | |

| Iatrogenic (drug-related steatosis) | Methotrexate, corticosteroids, tamoxifen | |

| Endocrine abnormalities | Polycystic ovarian syndrome, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism | |

| Visceral obesity | Reduces insulin sensitivity and steatosis development despite a lean phenotype and normal BMI | |

| Dysbiosis | Aberrations in the bile acid signaling pathway, dysbiosis lead to altered intestinal permeability, bacterial translocation | |

| Low % of muscle mass | Insulin resistance | |

| Sarcopenia | Insulin resistance |

| Category | Drug/Class | Mechanism | Trial Status | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Currently Used/Approved | Metformin | ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↓ hepatic gluconeogenesis, mild effect on ↓ hepatic fat | Clinical | GI adverse effects are generally well-tolerated |

| Thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone) | ↑ insulin sensitivity, Activates PPARγ, ↓ hepatic steatosis, and steatohepatitis (histological improvement) | Clinical | Increase in body weight, fluid retention, and cardiac complications | |

| Statins (simva-, atorva-, rosuvastatin) | ↓ LDL-c (HMG-CoA reductase inhibition, ↑ LDL receptor), liver enzyme improvement | Clinical | Risk of SAMS, rhabdomyolysis, and monitoring liver enzymes | |

| Ezetimibe | ↓ intestinal cholesterol absorption, additional ↓ LDL-c (in combination with statins) | Clinical | May increase SAMS risk with statins | |

| Fibrates (fenofibrate) | ↓ Triglycerides, ↑ HDL, activate PPARα, ↑ fatty acid oxidation | Clinical | Cautious use in liver impairment | |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | ↓ Triglycerides (↓ synthesis), ↓ inflammation | Clinical | Well tolerated, usually in combination | |

| PCSK9 inhibitors (Inclisiran, Alirocumab, Evolocumab) | Inclisiran: siRNA suppressing PCSK9, ↑ LDL receptor, ↓ LDL-c; Alirocumab/Evolocumab: monoclonal antibodies | Clinical | Effective in statin-intolerance (SAMS), costly, injectable | |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (Semaglutide) | ↑ insulin secretion, ↓ appetite, ↓ body weight, delayed gastric emptying, ↓ hepatic fat, MASH improvement, no worsening of fibrosis, liver enzyme improvement/normalization | Phase 3 ESSENCE trial (NCT04822181) | GI adverse effects, injectable form | |

| Androgen Replacement Therapy for low testosterone | Restore disrupted signaling pathways, improve metabolic imbalances, ↓ and reduce steatosis. | Clinical | Potential adverse effects: hypertension, cardiovascular events, prostate hyperplasia, high-risk prostate cancer | |

| Clinical/Investigational | Survodutide | — | Phase 2/3 NCT06309992 | — |

| Tirzepatide | ↓ hepatic fat accumulation, MASH improvement, improved fibrosis, and improvement of steatohepatitis in F2/F3 | Phase 2 SYNERGY-NASH NCT04166773 | — | |

| SCD1 Inhibitor (Aramchol) | ↓ hepatic lipogenesis, ↓ triglyceride accumulation | Phase 3 ARMOR trial (NCT04104321) | Ongoing status | |

| FXR Agonists (Cilofexor) | Activates FXR, ↓ hepatic fat & inflammation, ↓ bile acid synthesis | Phase 2 clinical trials | Safety concerns for OCA, EDP-305, and Tropifexor favorable effects | |

| PPAR Agonists (Lanifibranor, Elafibranor, Saroglitazar) | Lanifibranor: activates PPAR α/γ/δ, ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↓ hepatic fat, inflammation, fibrosis; Elafibranor: activates PPAR α/δ; Saroglitazar: dual PPAR α/γ agonist | Phase 3 NATiV3, RE-SOLVE-IT, Phase 4 NCT05872269 | Elafibranor: no primary endpoints met; Lanifibranor/Saroglitazar: ongoing status | |

| Thyroid Hormone Receptor β Agonists (Resmetirom) | ↑ mitochondrial β-oxidation, ↑ FA oxidation, cholesterol/phospholipids exported into bile | Phase 3 MAESTRO trials (NCT03900429, NCT05500222) | — | |

| HU6 | Mitochondrial uncoupler, ↓ hepatic fat (>30%) | Phase 2 | — | |

| FGF21 Analogs (Efruxifermin, Pegozafermin) | ↓ hepatic fat, inflammation, fibrosis | Phase 2/2b; Phase 3 ongoing | — | |

| Namodenoson | A3 adenosine receptor agonist | Phase 3 NCT04697810 | — | |

| Cenicriviroc | CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor | Phase 2b CENTAUR; ongoing Phase 3 AURORA | — | |

| Belapectin | Galectin-3 inhibition | Phase 2b/3 NAVI-GATE NCT04365868 | — | |

| LPCN 1144 | Endogenous testosterone prodrug, beneficial in non-cirrhotic hypogonadal males with MASH | Clinical | — | |

| SARMs (Enobosarm, RAD-140, LGD-4033, S-23) | No role in hepatic steatosis or lipid metabolism; can cause DILI, aggravate metabolic dysfunction. | Clinical | Case reports: 29- and 52-year-old males developed DILI, which resolved after discontinuation. | |

| Preclinical | AR-lowering miRNAs (miR196a, miR-298) | Potential AR suppression | Preclinical | — |

| mTORC1-AR axis blockade (Salinomycin, Rapamycin) | Suppresses mTORC1/AR, stimulates autophagy, and decreases AR transcriptional activity. | Preclinical | No adequate studies for AR-mTORC1 in AR-dysfunction SLD | |

| Liver-specific AR modulators (EP-001) | AR receptor suppressor reduces hepatic steatosis via CYP2E1 inhibition, modulates PPAR, and blocks fat in hepatocytes. | Preclinical | Preclinical evidence only | |

| Liver-muscle axis modulators (Clenbuterol) | ↑ glucose uptake in skeletal muscles, alleviate hepatic steatosis, improve neuromuscular/metabolic function | Preclinical | No direct effect on AR signaling | |

| Myostatin inhibitors (Bimagrumab) | Improving insulin resistance and muscle mass is a potential benefit for hepatic steatosis. | Preclinical | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trifylli, E.M.; Charalambous, C.; Spiliotopoulos, N.; Papadopoulos, N.; Oikonomou, A.; Manolakopoulos, S.; Deutsch, M. Implication of the Androgen Receptor in Muscle–Liver Crosstalk: An Overlooked Mechanistic Link in Lean-MASLD. Livers 2025, 5, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040065

Trifylli EM, Charalambous C, Spiliotopoulos N, Papadopoulos N, Oikonomou A, Manolakopoulos S, Deutsch M. Implication of the Androgen Receptor in Muscle–Liver Crosstalk: An Overlooked Mechanistic Link in Lean-MASLD. Livers. 2025; 5(4):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040065

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrifylli, Eleni Myrto, Christiana Charalambous, Nikolaos Spiliotopoulos, Nikolaos Papadopoulos, Anastasia Oikonomou, Spilios Manolakopoulos, and Melanie Deutsch. 2025. "Implication of the Androgen Receptor in Muscle–Liver Crosstalk: An Overlooked Mechanistic Link in Lean-MASLD" Livers 5, no. 4: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040065

APA StyleTrifylli, E. M., Charalambous, C., Spiliotopoulos, N., Papadopoulos, N., Oikonomou, A., Manolakopoulos, S., & Deutsch, M. (2025). Implication of the Androgen Receptor in Muscle–Liver Crosstalk: An Overlooked Mechanistic Link in Lean-MASLD. Livers, 5(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040065