Abstract

Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain (CPP) impose substantial economic burden in New Zealand, yet no national cost-of-illness (COI) model currently exists. This study provides the first nationwide estimate using a modified World-Endometriosis-Research-Foundation (WERF) EndoCost protocol incorporating direct healthcare, productivity, and carer costs. An attribution correction model was applied to account for diagnostic overlap, assigning 43.4% of CPP cases to endometriosis. Attribution-adjusted annual per capita costs were INT 97,497 (NZD 174,130) for endometriosis and INT 33,262 (NZD 59,406) for CPP. Macroeconomic costs ranged from INT 12.7B to 17.7B (NZD 22.6B–31.7B) per annum, depending on prevalence. Productivity losses were the primary cost driver, accounting for 65% of endometriosis and 75% of CPP cost. The unattributed lifetime burden was INT 1.96M (NZD 3.50M) per person for endometriosis and INT 1.54M (NZD 2.74M) per person with CPP. This reflects total economic burden over a 34.5-year working lifespan, adjusted for labor-force participation. Diagnostic delays and health system inefficiencies such as poor healthcare access and suboptimal symptom management are likely to be the most significant modifiable contributor to this burden. Addressing this will require investment in healthcare provision and symptom management alongside equitable access to fertility care.

1. Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is pelvic pain which occurs on most or all days, lasts more than six months, and is not associated with pregnancy [1]. CPP can be debilitating, often requiring clinical intervention and significantly impairing daily functioning and quality of life [2,3]. Globally, CPP’s prevalence is ~24–26% of women, girls, and trans and gender-diverse individuals presumed female at birth [4,5]. A 2004 study reported that up to a quarter of reproductive-aged women in New Zealand experience pelvic pain [6], yet contemporary data on prevalence for New Zealand remain limited. Endometriosis, a chronic full-body condition, characterized by endometrial-like tissue found outside the uterus [7], is estimated to affect around 10–14% of all reproductive-aged women, with some studies indicating up to 18% in undiagnosed populations [8,9,10]. Current estimates suggest that endometriosis is the underlying cause of between 15.4% to 71.4% among women with CPP symptoms, suggesting that the true prevalence is significantly greater [11].

Recent Australian data suggest that nearly half of all women report symptoms consistent with CPP within a five-year period [12]. Diagnostic delays in New Zealand have historically been over eight years, contributing to fragmented care pathways and prolonged symptomatic burden [2,13]. The economic burden of endometriosis is substantial across a range of countries, including the USA, UK, and Europe [14]. The social and occupational impacts of endometriosis and CPP span multiple domains (e.g., education, employment, relationships, and fertility), yet no cost-of-illness (COI) model has quantified New Zealand’s burden [2].

The most comparable study in terms of recency, methodology, and similarity of healthcare systems is the 2019 Australian study that estimated an annual burden of $6.5B (international dollars, hereafter abbreviated to INT), equivalent to INT$8.5B in 2025 values [15]. (To caveat, the Australian study was top-down and this analysis was bottom-up [15]). That estimate included both direct healthcare expenditures and indirect productivity losses and rivals the cost burden of diseases such as diabetes, Crohn’s, and rheumatoid arthritis [14,16]. However, no equivalent modeling exists for New Zealand.

This study addresses that gap by providing the first COI estimate for endometriosis and CPP in New Zealand. A modified World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF) EndoCost protocol was used to quantify direct medical costs, productivity losses, and carer burden [17]. This analysis provides the economic evidence base needed to inform targeted reform, equitable resourcing, and systemic accountability in women’s health.

2. Results

Demographic data are reported in Table 1. A total of 800 participants participated in the survey, with 620 of these self-reporting a laparoscopic diagnosis of endometriosis and 180 reporting a diagnosis of CPP either from another confirmed diagnosis (e.g., painful bladder syndrome, vulvodynia) or without any formal diagnosis. Most participants were New Zealand European (Pākeha), followed by Māori, Pacific, Asian, and MELAA (Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African) thereafter. Most respondents were nulliparous, and most reported a high level of education. Most participants reported an income of between NZD 500 and NZD 1500 per week.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

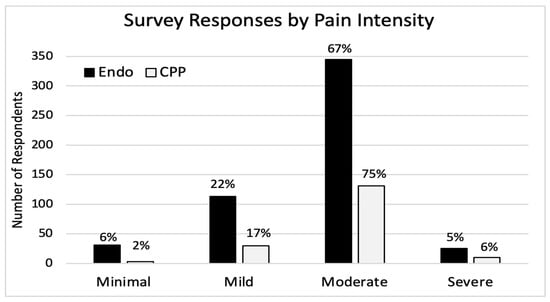

2.1. Pain Stratification and Survey Response

Results were stratified by self-reported pain severity across four categories: minimal, mild, moderate, and severe (Figure 1). For endometriosis, pain severity was distributed as follows: minimal (6%), mild (22%), moderate (67.1%), and severe (4.9%). For CPP, distribution was minimal (1.7%), mild (17.2%), moderate (75.3%), and severe (5.7%). Stratification by pain severity was used in place of disease stage, given its stronger correlation with economic burden and greater relevance to clinical management.

Figure 1.

Survey response by pain intensity.

2.2. Per Capita Costs and Attribution Adjustment

The unattributed direct per capita cost of endometriosis was INT 71,992, with indirect costs totaling INT 47,809. For CPP, unattributed direct and indirect costs were INT 20,931 and INT 44,970 per capita, respectively. All DAC estimates will be reported at the median value (43.4%). At the median DAC, per capita costs were INT 97,497 (NZD 174,130) for endometriosis and INT 33,262 (NZD 59,406) for CPP. These estimates quantify the adjusted economic burden accounting for diagnostic overlap. Upper and lower bound estimates for attribution have been included below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lower, median and upper bound estimates for diagnostic attribution correction estimates (Micro).

2.3. Macroeconomic Burden and Cost Distribution

At 10% prevalence, attributed macroeconomic costs with the DAC were INT 9.5B (NZD 16.9B) for endometriosis and INT 3.2B (NZD 5.7B) for CPP, totaling INT 12.7B (NZD 22.6B). At a 14% prevalence, the median DAC costs rose to INT 13.3B (NZD 23.7B) and INT 4.5B (NZD 8B), respectively, for a combined burden of INT 17.7B (NZD 31.7B). The midpoint between the 10% and 14% national burden (combined total of INT 15.2B (NZD 27.1B) with a 12% prevalence) likely represents the best estimate of total macroeconomic burden. Productivity hours lost across all indirect domains exceeded 8 million annually at 10% prevalence, and 11.2 million at 14%. Upper and lower bound estimates for attribution have been included below (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Lower, median, and upper bound estimates for diagnostic attribution correction estimates (Macro INT).

Table 4.

Lower, median, and upper bound estimates for diagnostic attribution correction estimates (Macro NZD).

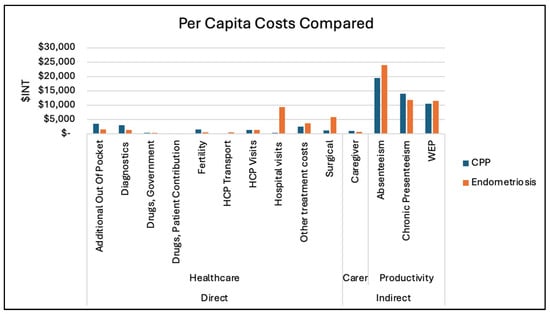

2.4. Burden by Domain

For endometriosis, 34% of the total burden was accounted for by direct healthcare costs and 65% by productivity losses. For CPP, productivity was responsible for 75% of the burden and for 23% of direct medical costs. Carer burden was minimal overall (0.97% for endometriosis, 1.64% for CPP), but highly variable, with per capita costs reaching up to INT 9000 (CPP) and INT 1680 (endometriosis). A further per capita cost domain breakdown by category is shown in Figure 2. A further cost breakdown for macroeconomic costs by domain category for both endometriosis and CPP can be seen in Figure S2.

Figure 2.

Per capita costs (both CPP and Endometriosis).

2.5. Cost Variation by Diagnosis and Severity

Fertility-related costs were consistently higher for CPP across all age brackets. Surgical costs were higher for endometriosis across all age groups, likely reflecting access to diagnostic laparoscopy and therapeutic interventions.

Stratified analysis showed a positive correlation between symptom severity and total burden, particularly in diagnostic and fertility costs. Hospital-related costs, other treatment, and surgeries were broadly comparable among those reporting at least mild pain. Full macroeconomic and per capita breakdowns by age are presented in Figure S3.

2.6. Indirect Economic Burden

2.6.1. Absenteeism

Endometriosis respondents reported an average wage-adjusted productivity loss of INT 12,125. Applying Stromberg’s absenteeism multiplier (0.97) added INT 11,762 in employer costs, for a total burden of INT 23,887 per person. For CPP, the wage loss was INT 9898; the adjusted employer cost was INT 9601, totaling INT 19,498 per person.

Productivity hours lost to absenteeism were 2.17M for endometriosis and 838K for CPP at 10% prevalence, and 3.04M and 1.17M at 14% prevalence.

2.6.2. Chronic Presenteeism

For endometriosis, the base wage loss was INT 7651. Stromberg’s 0.54 multiplier added INT 4132 in employer costs, totaling INT 11,783 per person. For CPP, base loss was INT 9123; the adjusted per capita burden was INT 14,049.

At 10% prevalence, unattributed costs were INT 996.6M for endometriosis and INT 1.19B for CPP. Presenteeism hours lost were 2.16M (endometriosis) and 1.05M (CPP) at 10%; and 3.02M and 1.47M at 14%, respectively.

2.6.3. Work Environment-Related Productivity Loss (WEP)

The per capita WEP burden was INT 11,443 for endometriosis and INT 10,459 for CPP. Impaired hours from WEP were 2.24 million for endometriosis and 1.02 million for CPP, totaling 3.27 million hours of organizational coordination loss at the national level.

2.6.4. Total Indirect Burden

Endometriosis’ per capita indirect burden was INT 47,113, composed of INT 23,887 from absenteeism, INT 12,585 from presenteeism, and INT 11,443 from WEP. For CPP, the total was INT 44,006, made up of INT 19,498, INT 14,934, and INT 10,459, respectively.

2.7. Total Lifetime Cost and Productivity Loss

Lifetime economic burden, adjusted for labor force participation [18], was estimated at INT 1.96M for endometriosis and INT 1.54M for CPP, per affected individual over a 34.5-year working lifespan. At the national level, total productivity hours lost across all indirect domains exceeded 8 million annually at 10% prevalence and 11.2 million at 14%, reflecting sustained impairment from absenteeism, presenteeism, and WEP. Over a lifetime, productivity impairment for affected individuals is estimated to exceed 3.27 million hours nationally, even using conservative assumptions. Table A1 demonstrates the productivity cost calculations per capita.

3. Discussion

This represents the first COI analysis for endometriosis and CPP in New Zealand, revealing a substantial economic burden. To maintain cross-study comparability and avoid inflation of estimates, conservative prevalence assumptions (10–14)% were applied based on the best available data [19]. These estimates were used to extrapolate to the New Zealand population because they represent the closest available proxy. It should be noted that this is a significant limitation of the study and should emphasize a focus for research in the future.

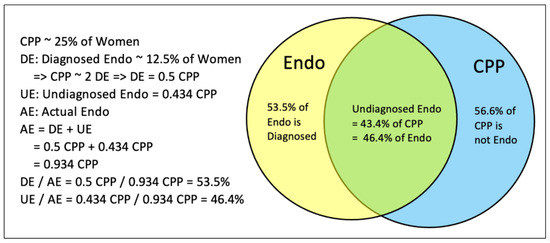

A key methodological challenge was the risk of double-counting symptomatic burden due to population overlap. Literature attributes a significant proportion of CPP to underlying endometriosis, suggesting many CPP cases represent undiagnosed or misclassified endometriosis [3,20,21,22]. To correct for this, the previously described DAC model was applied: it retained 100% of the economic burden for diagnosed endometriosis and included 43.4% of the CPP burden, based on the assumption that only the remaining 56.6% of CPP is not endometriosis [11]. This aimed not to overstate the true national burden. To our knowledge, no prior COI study for CPP and endometriosis has used attribution logic similar to this model. These findings significantly exceed previous Australian estimates [15]. The 2019 Australian COI study reported a per capita burden of AUD 20,898 (equivalent to NZD 26,047 in 2025 terms) [15], compared to attributed per capita estimates of INT 97,497 for endometriosis and INT 33,262 for CPP. Under the median DAC, the total macroeconomic burden of endometriosis rose to approximately 288% higher than that of CPP. This reflects a compounding effect of growing endometriosis burden, i.e., each 1% of attribution shifted from CPP to endometriosis not only reduces CPP’s burden but simultaneously increases endometriosis’s share, resulting in a mirrored reallocation. This movement causes divergence over time (producing wide variance in lower bound estimates of 163% and upper bounds exceeding 678%), depending on the attribution level.

This highlights the impact of the DAC, productivity multiplier inclusion, and workforce-calibrated wage scaling on national burden estimates. This adjustment not only preserved total burden but substantially altered how endometriosis and CPP are economically distributed, a shift that impacts cross-national and all other macroeconomic comparisons.

Productivity loss emerged as a major driver of economic burden in both cohorts. Its predominance reflects the chronic and often invisible nature of endometriosis and CPP, accentuating the need for policy responses that go beyond acute sick leave models [23]. The previously unaccounted for WEP, reflecting employer coordination inefficiencies, contributed 16–18% the total burden across both cohorts.

The indirect costs emphasize the structural labor force impact of endometriosis and CPP. Absenteeism was the largest single contributor to productivity loss, accounting for 45% of the per capita indirect burden in endometriosis and 39% of CPP. Presenteeism and WEP accounted for the remaining percentages, reflecting the chronic nature of these conditions and the cumulative effect of degraded work performance and coordination inefficiencies. This productivity burden is consistent with prior studies [14,15,24]. At a 14% prevalence, more than ten million hours of productivity are lost or impaired annually on a countrywide level, equivalent to several thousand full-time workers effectively removed from the labor market. These losses represent a sustained drag on national productivity.

The greater share of direct costs (such as healthcare encounters, fertility costs, and surgery) relative to prior literature may reflect differences in system access, out-of-pocket structures, or diagnostic delays. It also highlights that productivity losses, while dominant, do not fully capture the costs and that health system inefficiencies remain a major contributor, reinforcing the necessity for targeted interventions, improved workplace accommodations, and medical strategies to alleviate financial strain on individuals, businesses, and the economy.

Direct healthcare costs revealed significant disparities in hospital-related expenditures and surgical interventions. Endometriosis incurred substantially higher per capita hospital visit costs compared to CPP (INT 9299 vs. INT 331), and over five times the surgical costs (INT 5838 vs. INT 1096). These differences are likely attributable to surgical interventions such as diagnostic laparoscopy and excision, which may be offered more commonly for endometriosis than for CPP without a confirmed diagnosis [25].

Notably, endometriosis cases incurred higher surgical costs, potentially reflecting increased care access. Patients diagnosed with CPP alone may encounter fragmented or deferred care, potentially leading to cumulative lower-yield healthcare resource utilization [26,27].

Individuals with CPP had higher per capita fertility expenditures. In New Zealand, public funding for assisted reproductive technologies often requires a diagnosis of subfertility or defined medical criteria [28]. As a result, CPP patients may disproportionately rely on out-of-pocket fertility consultations and privately funded cycles, particularly in the absence of surgical confirmation of endometriosis. Fertility costs were higher in those over 39, consistent with reduced access to publicly funded services [28].

Cost distribution by age showed the highest combined total burden in the 25–30 group (INT 3.61B), followed by the 18–24 group (INT 3.51B), the 31–38 group (INT 3.26B), and the 39+ group (INT 2.29B). This trend may reflect earlier engagement with diagnostic pathways and a greater impact on workforce participation.

Subgroup analyses showed that pain severity, rather than disease stage, was the most consistent predictor of increased economic burden, reinforcing calls to prioritize symptom-based triage and management. This aligns with both local and international guidelines, which emphasize pain impact over staging in referral and treatment decisions [29,30,31,32].

Although this study quantified average burden, it is likely that the highest costs are concentrated among already underserved groups. Māori and Pacific women may experience longer delays, reduced access to diagnostic pathways, and structural dismissal of pain, all of which compound economic harm. These inequities are perpetuated by the systems in which we provide care. Future work will examine this burden directly, but any national response must center on equity, not only in access to care, but in the fiscal frameworks used to justify reform.

While this study did not directly model health utility loss, previous research using EQ-5D has estimated utility scores of 0.72 to 0.81 among women with endometriosis, corresponding to an annual decrement of approximately 0.19 quality-adjusted-life-years (QALYs) [14]. This equates to a cumulative loss of up to 6.9 QALYs over the working lifespan (15.5% of the total), reinforcing the profound non-financial burden associated with CPP and endometriosis.

These values underscore the cumulative fiscal damage imposed by untreated pelvic pain across the prime working years and the importance of timely diagnosis and symptom management. These estimates reflect persistent productivity losses over three decades and reinforce the argument that under-diagnosis, delayed intervention, and inadequate symptom management impose not only annual strain, but rather lifelong economic strain [23,33].

Limitations

As with all self-reported survey studies, this analysis is subject to sampling bias. Participants were recruited through endometriosis-focused clinical networks, public calls, private providers, and digital platforms. This enabled broad reach, but likely overrepresented individuals with higher symptom burden, greater health-seeking behaviors, or stronger advocacy engagement, traits that may skew toward higher cost estimates.

In turn, this may limit generalizability of the data to the wider population. Given the advocacy-based recruitment strategy and known bias toward individuals with greater symptom severity and diagnostic engagement, we acknowledge that our sample is more likely to reflect the higher end of the burden distribution [34]. While this does not allow us to assert definitively that these are maximum values, they should be interpreted as representative of higher-burden cases rather than population averages. Contrarily, this same cohort also represents those most impacted by diagnostic delay and under-treatment, meaning the costs captured here may reflect the true economic burden among the most affected populations, the very groups where system reform would yield the greatest return.

While our model aligns CPP and endometriosis prevalence bases to preserve attribution clarity and lifetime modeling consistency, we acknowledge that prior studies have reported higher symptom-based point prevalence of CPP, including up to 24% in cross-sectional surveys [6]. If CPP were modeled at 24% prevalence with the same per-patient burden assumptions, the national economic burden would rise to INT 7.66 billion (or NZD 13.68 billion) under a 42.4% DAC modifier.

Indirect costs were estimated using a derived presenteeism proxy built from pain severity and functional limitation rather than direct reporting of impaired work hours. While this approach introduces modeling assumptions, the proxy method was conservative and consistently applied across both CPP and endometriosis cohorts. Direct costs were scaled to all women meeting diagnostic prevalence, while indirect costs were scaled only to employed women aged 18–54, based on a 67.6% national labor force participation rate. Lifetime indirect burden was modeled from age 19.5 onward, reflecting average labor force entry for New Zealand women and preventing overstatement of working life impairment.

Directional sensitivity testing, reported in Supplementary File S2, confirmed burden estimate stability within a ±10–13% range under plausible variations in wage, participation, and multiplier inputs.

Carer costs were calculated using minimum wage valuation, which likely understates the full economic value of unpaid care. QALY loss was not directly modeled, but prior EQ-5D-based studies have estimated annual utility decrements of ~0.19 among women with endometriosis [14]. While this study did not stratify by ethnicity, a separate equity-focused analysis is in development to assess diagnostic disparities and differential economic burden for Māori and other underrepresented groups in New Zealand.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics and Consent

The Health and Disability Ethics Committee of New Zealand confirmed that this survey was out of scope for full ethical review. Informed consent was obtained remotely from participants before the commencement of the online survey. All responses were anonymized. Even though this study was out of scope for full ethical review by the committee, all researchers have experience in maintaining ethical standards such as the Declaration of Helsinki, and this study adheres to those standards.

4.2. Survey

Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture v10.6.4) hosted at the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand (MRINZ) [35]. All methods described were in accordance with MRINZ best-practice protocols, and oversight was administered by named researchers. The WERF EndoCost tool and protocol (validated and used internationally) were adapted to form a 99-item retrospective questionnaire delivered online [17,35]. Questions were adapted to fit a New Zealand context regarding drug names and demographic information. This study reports the data related to economic burden, data relating to symptom impact, and diagnostic delay have been presented previously [2]. This survey asked questions about information on direct healthcare costs, carer costs, and indirect costs relating to productivity. Participants did not have to answer all questions in the survey, except for date of birth and cause of pain (i.e., CPP or endometriosis confirmed on laparoscopy). The full survey can be found within the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary File S1).

4.3. Recruitment

Recruitment was via Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter within the networks of named researchers and dissemination using information sheets through public hospitals (Christchurch and Auckland Hospital) and private hospital clinics. The clinics were Auckland Gynaecology Group, Endometriosis Ascot, Shore Women, Oxford Women’s Health, and Gynecologists at St Georges Hospital. The advertisement was spread by collaborators who have relationships with named researchers, including Endometriosis New Zealand (who had >10K followers at the time of recruitment). To encourage participation, the survey was not restricted and was made ‘public’ to anyone who had the survey website link. Participant Information Sheets and consent forms were presented online prior to the survey’s commencement. It was conducted over 10 weeks between March and May 2021 and was estimated to take 60 min to complete. Simple inclusion criteria included participants aged over 18 years, currently living in New Zealand, and whether participants were affected by either CPP or endometriosis. All data was self-reported, and participants were able to save, return, and complete responses at a later stage.

4.4. Data Analyses

Statistical analysis was undertaken by a biostatistician (AE) and a health economist (MG). Results were reviewed by a second economist and data analyst (RF) with doctoral training in economics. In line with standard COI methodology, no sample size calculations were required, as the study quantified economic burden rather than tested a hypothesis.

A societal perspective was adopted, incorporating direct costs (health sector), indirect costs (productivity loss) using a human capital approach with multiplier effects, and carer costs [36]. The previously referred multiplier effects were added to the total productivity cost to reflect the impacts of presenteeism and absenteeism as per health economic theory shown by Stromberg et al. [36].

Direct cost scaling was based on a total population of approximately 1.2 million women aged 18–54 as of January 2025 [37]. CPP prevalence was kept consistent with endometriosis to allow comparison between groups. Both 10% and 14% prevalence models were assessed to rectify diagnostic uncertainty [8,9]. Indirect costs were scaled using the national labor force participation rate for women (67.6%), corresponding to employed individuals aged 18–54 [18,37,38]. A graph representing this, broken down into proportions by age, is shown in Figure S1.

Economic analyses reported per capita (microeconomic) and population (macroeconomic) costs for each group. Per capita costs refer to annual per-person costs. To address diagnostic overlap, given current evidence reports that a range from 15.4% to 71.4% of all CPP can be attributed to endometriosis [11], the midpoint of this range (43.4%) of CPP cases was used to attribute these CPP cases to undiagnosed endometriosis. This attribution correction model, herein referred to as the diagnostic attribution correction (DAC), is demonstrated in Figure 3. This model preserves the full burden of diagnosed endometriosis while allocating only 56.6% of the CPP burden to a standalone group, avoiding double-counting due to diagnostic uncertainty.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram demonstrating the attribution correction model.

All reported costs are represented in international dollars (INT), unless otherwise specified. The conversion rate used was INT 1 = NZD 1.786, as of January 2025 [24]. Results reporting cost estimates amounting to billions are abbreviated to B, and millions are abbreviated to M. Supplementary methods are available to view as Supplementary File S2 for further explanation on methodology regarding indirect burden and WEP calculations.

Furthermore, a list of causes for CPP is found below in Table A2.

4.5. AI-Assisted Writing Statement

Generative AI (ChatGPT (version GPT-4-turbo), OpenAI) was used in a limited editorial capacity to clarify economic terminology and help restructure technical text for generalist readability. The tool was not used to perform any modeling, analysis, or data transformation. All analytical processes and final language were reviewed and finalized by the authors.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first comprehensive COI analysis for endometriosis and CPP in New Zealand, revealing a substantial economic burden on individuals, families, employers, and the health system. Using a national survey and modified WERF EndoCost protocol, the median DAC per capita costs are INT 97,497 for endometriosis and INT 33,262 for CPP. With population overlap considered, the macroeconomic burden ranges from INT 12.7B to INT 17.7B, with a midpoint estimate of INT 15.2B, exceeding the inflation-adjusted Australian benchmark and rivaling that of other major chronic diseases. Productivity losses emerged as the primary cost driver, but direct healthcare costs were also substantial, particularly for individuals experiencing severe pain or delayed diagnosis. This analysis offers compelling economic justification for prioritizing endometriosis and CPP as national health policy concerns in New Zealand. Even under conservative modeling assumptions, endometriosis and CPP represent a significant unmet clinical and economic challenge facing New Zealand. This analysis provides an unambiguous fiscal case for investment in early access to medical assessment and prioritizing diagnosis (e.g., improvement in skilled practitioners in women’s health, improved access to validated imaging modalities such as dynamic ultrasound imaging or MRI, and improved access to specialists who are experienced in diagnosing endometriosis and CPP which includes but is not limited to laparoscopic surgery. Further considerations for equitable fertility care access and culturally responsive, symptom-centered care should be a priority.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/women5040047/s1. Figure S1: New Zealand Female Working Population aged 18–54; Figure S2: Total Economic Burden of Endometriosis and CPP (All prevalence rates); Figure S3: Total economic Cost by Age (CPP and Endometriosis); Supplementary File S1: Participant Questionnaire; Supplementary File S2: Extended Methods.

Author Contributions

J.T.-S., M.G. and M.A. were responsible for study conception and design, and were the lead research team, coordinating the majority of the research work (work was contributed to equally). A.A., A.E. and J.T.-S. managed data access, cleaning, and internal validation. M.G. and R.F. developed the economic model and methodology. M.G., J.T.-S. and M.A. interpreted the data. J.T.-S., M.G. and M.A. developed and drafted the manuscript. D.B., N.J., M.E., J.M., J.E.G., A.S. and R.F. contributed to the clinical framing and manuscript revisions. M.A. supervised the project as the senior author. M.G., A.A. and A.E. accessed and verified the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand (the corresponding author’s institutional affiliation). No additional funding was obtained for the undertaking of the research or publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Health and Disability Ethics Committee of New Zealand confirmed that this survey was out of scope for full ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained remotely from participants before the commencement of the online survey.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Summary graphs are available alongside this manuscript presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The study group would like to thank all participants for their valued time completing the survey and their contributions to research in endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to assist with language refinement and clarification of technical phrasing. All modeling, data interpretation, and final writing decisions were conducted and approved by the authors, who accept full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUD | Australian dollars |

| CPP | Chronic pelvic pain |

| DAC | Diagnostic attribution correction |

| INT | International dollars |

| MELAA | Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African |

| MRINZ | Medical Research Institute of New Zealand |

| NZD | New Zealand dollars |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life years |

| WEP | Workplace Environment Productivity Loss |

| WERF | World Endometriosis Research Foundation |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Direct per capita cost for productivity.

Table A1.

Direct per capita cost for productivity.

| Metric | CPP ($ INT) | Endometriosis ($ INT) |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated adjusted working population affected | 33,834–47,367 individuals | 135,335–189,470 individuals |

| Absenteeism | hours | |

| Hours lost per person per year | 334 h | 354 h |

| $ lost per person (employee share) | $9898 | $12,125 |

| $ lost per person (employer share) | $9601 | $11,762 |

| Total per person | $19,498 | $23,887 |

| Presenteeism | ||

| Hours lost per person per year | 645 h | 471 h |

| $ lost per person (employee share) | $9123 | $7651 |

| $ lost per person (employer share) | $4926 | $4132 |

| Total per person | $14,049 | $11,783 |

| Metric | CPP ($INT) | Endometriosis ($INT) |

| Workplace Environment Problems (WEP) | ||

| $ lost per person (employer-only) | $10,459 | $11,443 |

| Total Indirect Burden | ||

| Individual | $44,006 | $47,113 |

| National | $1.49B–$2.08B | $6.21B–$8.72B |

Table A2.

Causes of chronic pelvic pain c.

Table A2.

Causes of chronic pelvic pain c.

| Body System | Examples of Conditions Causing CPP |

|---|---|

| Gynecological | Endometriosis, adenomyosis, adhesions (secondary to infection or surgery), chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic organ prolapse, pelvic congestion syndrome, benign tumors (e.g., uterine, ovarian), vulval or vaginal pain syndromes, ovarian remnant syndrome, trapped ovary syndrome. |

| Gastrointestinal | Constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, diverticulosis, chronic appendicitis, meckles diverticulum, adhesions. |

| Urological | Bladder pain syndrome (interstitial cystitis), urethral pain syndrome. |

| Neuromuscular | Trauma (e.g., secondary to vaginal delivery), surgery (e.g., any abdominal wall incision including cesarean section), pelvic floor muscle pain syndrome, vaginal muscle spasm, neuralgia from nerve entrapment or irritation, pain arising from the lower part of the spine (e.g., from sprains, strains, fractures, degenerative disease, disk lesions), sacroiliac joint dysfunction, symphysis pubis dysfunction, coccygeal pain, piriformis syndrome, myofascial pain syndrome, abdominal migraine. |

| Psychological | Depression, anxiety, history of sexual abuse. |

c This table was adapted directly from BPAC causes of Chronic pelvic pain [39].

References

- Howard, F.M.; Perry, P.; James, C.; El-Minawi, A.M. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tewhaiti-Smith, J.; Semprini, A.; Bush, D.; Anderson, A.; Eathorne, A.; Johnson, N.; Girling, J.; East, M.; Marriott, J.; Armour, M. An Aotearoa New Zealand Survey of the Impact and Diagnostic Delay for Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Diagnosis and Management of Endometriosis in New Zealand; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Latthe, P.; Latthe, M.; Say, L.; Gülmezoglu, M.; Khan, K.S. WHO Systematic Review of Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Neglected Reproductive Health Morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangari, A. Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain among Women: An Updated Review. Pain Physician 2014, 17, E141–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, V.M.; Zondervan, K.T. Chronic Pelvic Pain in New Zealand: Prevalence, Pain Severity, Diagnoses and Use of the Health Services. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2004, 28, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N.P.; Hummelshoj, L.; Adamson, G.D.; Keckstein, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Abrao, M.S.; Bush, D.; Kiesel, L.; Tamimi, R.; Sharpe-Timms, K.L.; et al. World Endometriosis Society Consensus on the Classification of Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, I.; Abbott, J.; Montgomery, G.; Hockey, R.; Rogers, P.; Mishra, G. Prevalence and Incidence of Endometriosis in Australian Women: A Data Linkage Cohort Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Endometriosis; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-disease/endometriosis-in-australia/contents/summary# (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Moradi, Y.; Shams-Beyranvand, M.; Khateri, S.; Gharahjeh, S.; Tehrani, S.; Varse, F.; Tiyuri, A.; Najmi, Z. A Systematic Review on the Prevalence of Endometriosis in Women. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M.; Kulkarni, M.T.; Missmer, S.A. Is Endometriosis More Common and More Severe Than It Was 30 Years Ago? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean Hailes for Women’s Health. National Women’s Health Survey: Pelvic Pain in Australian Women. 2023. Available online: https://www.jeanhailes.org.au/uploads/15_Research/2023-National-Womens-Health-Survey-Pelvic-Pain-in-Australia-FINAL_TGD.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Ellis, K.; Munro, D.; Wood, R. The Experiences of Endometriosis Patients with Diagnosis and Treatment in New Zealand. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 991045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The Burden of Endometriosis: Costs and Quality of Life of Women with Endometriosis and Treated in Referral Centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, M.; Lawson, K.; Wood, A.; Smith, C.A.; Abbott, J. The Cost of Illness and Economic Burden of Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Australia: A National Online Survey. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baburek, S.; Gannott, M.; Castle, R.; Contreras, D.; Armour, M.; Schott, A.; Ricci-De Lucca, E. Comorbidities and Mortality. 2024. Available online: https://docsend.com/view/ypjdi3n7ya24fidg (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Simoens, S.; Hummelshoj, L.; Dunselman, G.; Brandes, I.; Dirksen, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; EndoCost Consortium. Endometriosis Cost Assessment (the EndoCost Study): A Cost-of-Illness Study Protocol. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2011, 71, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatsNZ. Labour Market Statistics: December 2023 Quarter. Labour Force Participation. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/labour-market-statistics-december-2023-quarter/ (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Mishra, G.D.; Gete, D.G.; Baneshi, M.R.; Montgomery, G.; Taylor, J.; Doust, J.; Abbott, J. Patterns of Health Service Use before and after Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Data Linkage Prospective Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, L.H.R.; Reid, J.; Choa, A.; McFee, S.; Seretny, M.; Wilson, J.; Elton, R.A.; Vincent, K.; Horne, A.W. An Exploratory Study into Objective and Reported Characteristics of Neuropathic Pain in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowers, E.L.; Lim, C.S.; Skinner, B.; Mahnert, N.; Kamdar, N.; Morgan, D.M.; As-Sanie, S. Prevalence of Endometriosis During Abdominal or Laparoscopic Hysterectomy for Chronic Pelvic Pain. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Terada, Y.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K.; Kuriyama, S.; Tsuji, I. Management of the Pain Associated with Endometriosis: An Update of the Painful Problems. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2006, 210, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, M.; Rasanathan, J.J.K.; Remme, M.; Kennedy, C.; Barré-Quick, M.; Allotey, P.; Odey, G.; Torres-Rueda, S. Menstrual Health and Endometriosis: Costs Incurred by Women, Health Systems and Society. Npj Womens Health 2025, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Exchange Rates and Trade Weighted Index (B1), 2025. Available online: https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/statistics/series/exchange-and-interest-rates/exchange-rates-and-the-trade-weighted-index (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Conroy, I.; Mooney, S.S.; Kavanagh, S.; Duff, M.; Jakab, I.; Robertson, K.; Fitzgerald, A.L.; Mccutchan, A.; Madden, S.; Maxwell, S.; et al. Pelvic Pain: What Are the Symptoms and Predictors for Surgery, Endometriosis and Endometriosis Severity? Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet Gynaecol 2021, 5, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Barker, K. A Meta-ethnography of Patients’ Experiences of Chronic Pelvic Pain: Struggling to Construct Chronic Pelvic Pain as ‘Real’. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2713–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, J.; Farmer, G.; Harris, J.; Hope, T.; Kennedy, S.; Mayou, R. Attitudes of Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain to the Gynaecological Consultation: A Qualitative Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 113, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Region Fertility Service. Detail on Eligibility for Publicly Funded Fertility Services. 2018. Available online: https://www.fertilityassociates.co.nz/fertilityassociates-prod/downloads/Fertility-2018-Updated-FINAL-20181029-1.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Fedele, L.; Bianchi, S.; Bocciolone, L.; Di Nola, G.; Parazzini, F. Pain Symptoms Associated with Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 79, 767–769. [Google Scholar]

- Vercellini, P.; Trespidi, L.; De Giorgi, O.; Cortesi, I.; Parazzini, F.; Crosignani, P.G. Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain: Relation to Disease Stage and Localization. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 65, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Australian Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Endometriosis. 2021. Available online: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/Endometriosis-Clinical-Practice-Guideline.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, D.F.; Soliman, A.M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Taylor, H.S. Elagolix in the Treatment of Endometriosis: Impact beyond Pain Symptoms. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2020, 14, 2633494120964517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, A.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; Simoens, S.; De Bie, B.; Hummelshoj, L.; D’Hooghe, T.M.; Dunselman, G.A.J. Quality of Life Outcomes in Women with Endometriosis Are Highly Influenced by Recruitment Strategies. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strömberg, C.; Aboagye, E.; Hagberg, J.; Bergström, G.; Lohela-Karlsson, M. Estimating the Effect and Economic Impact of Absenteeism, Presenteeism, and Work Environment–Related Problems on Reductions in Productivity from a Managerial Perspective. Value Health 2017, 20, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Group. New Zealand Economies, Gender Data Portal. 2025. Available online: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/new-zealand (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Figure NZ Trust. Average Weekly Paid Hours for Employees in New Zealand. By Sex, Ordinary Time Plus Overtime, 1994 Q4–2024 Q4, Hours per Week. Available online: https://figure.nz/chart/5kwujxp84PCE3k40 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- BPAC New Zealand. Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women. Best Practice Journal. Available online: https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2015/september/pelvic.aspx (accessed on 9 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).