Strain Elastography in Urogynecology: Functional Imaging in Stress Urinary Incontinence

Abstract

1. Introduction

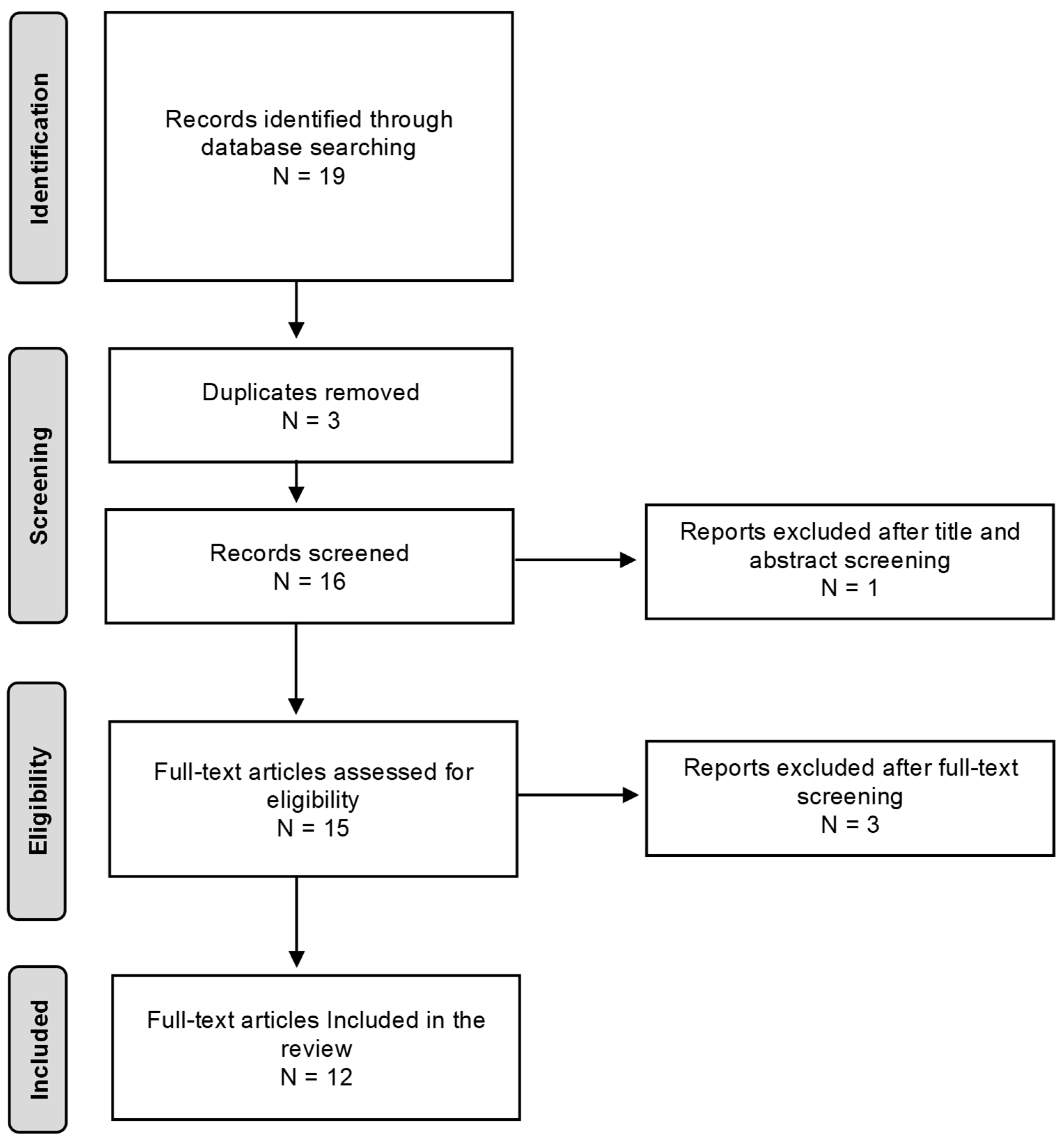

2. Materials and Methods

3. Pathophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence

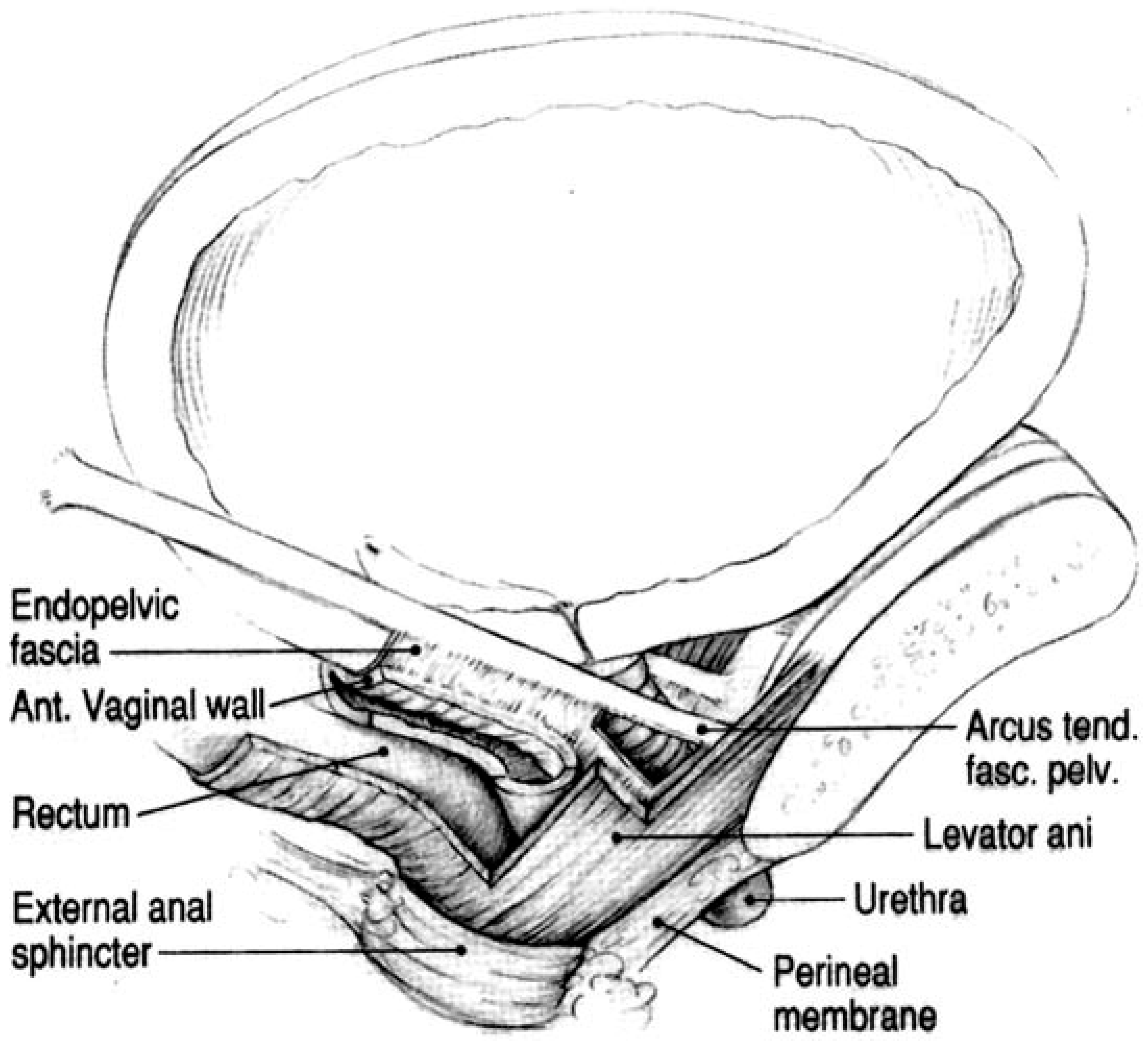

4. Anatomical and Biomechanical Context of Paraurethral Tissues

5. Elastography in Pelvic Floor Imaging: Principles and Techniques

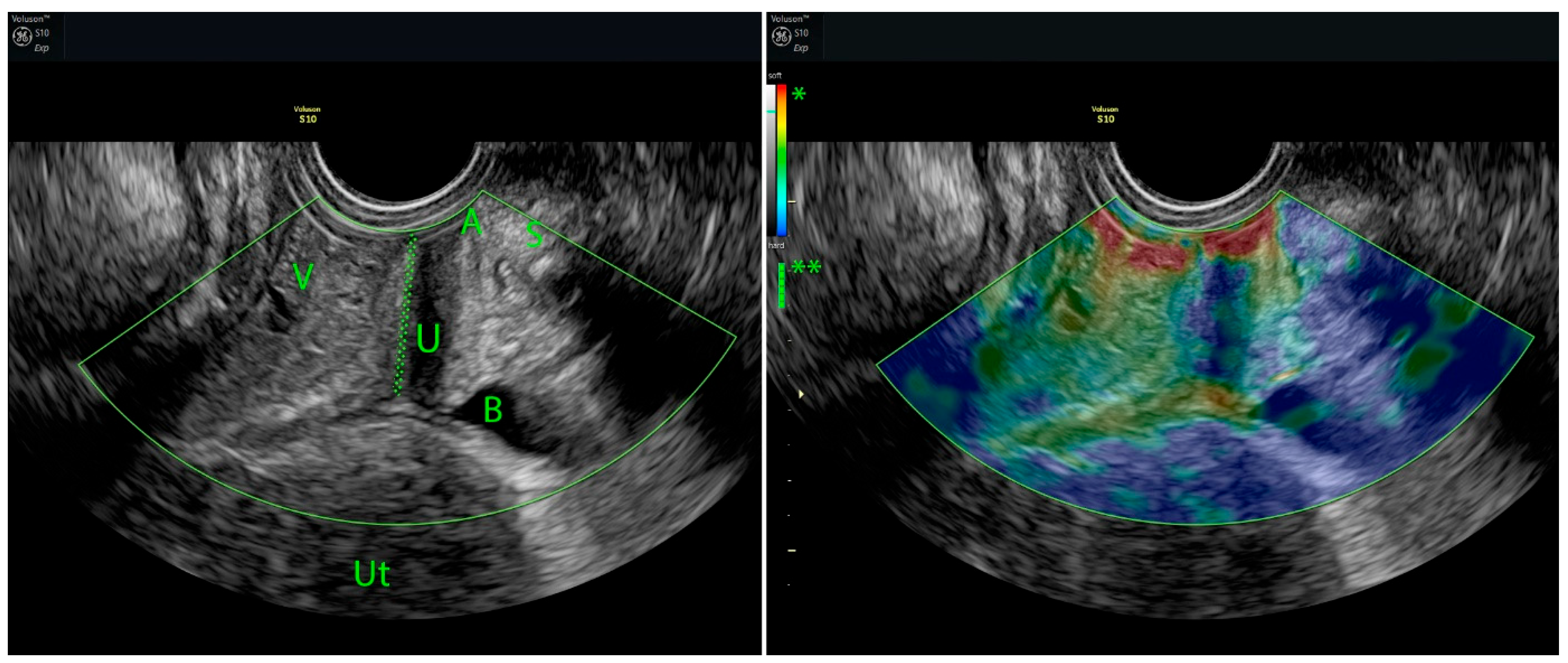

5.1. Strain Elastography (SE)

5.2. Shear Wave Elastography (SWE)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| 4D | four-dimensional |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| ATFP | arcus tendineus fascia pelvis |

| BMI | body mass index |

| B-mode | brightness-mode ultrasonography |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| ICS | International Continence Society |

| ISD | intrinsic sphincter deficiency |

| kPa | kilopascal |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| POP | pelvic organ prolapse |

| ROI | region of interest |

| SE | strain elastography |

| SUI | stress urinary incontinence |

| SWE | shear wave elastography |

| UI | urinary incontinence |

| USD | United States dollar |

References

- Lugo, T.; Leslie, S.W.; Mikes, B.A.; Riggs, J. Stress Urinary Incontinence. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey, J.O. Structural Support of the Urethra as It Relates to Stress Urinary Incontinence: The Hammock Hypothesis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 170, 1713–1720; discussion 1720–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylen, B.T.; De Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, L.; Liu, M.; Shen, H.; Luo, D. Diagnostic Value of Transperineal Ultrasound in Patients with Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csákány, L.; Kozinszky, Z.; Kovács, F.; Krajczár, S.K.; Várbíró, S.; Keresztúri, A.; Németh, G.; Surányi, A.; Pásztor, N. Evaluation of Suburethral Tissue Elasticity Using Strain Elastography in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.S.; Pierre, E.F. Urinary Incontinence in Women: Evaluation and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, U.J.; Godecker, A.L.; Giles, D.L.; Brown, H.W. Updated Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence in Women: 2015–2018 National Population-Based Survey Data. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 28, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamard, E.; Blouet, M.; Thubert, T.; Rejano-Campo, M.; Fauvet, R.; Pizzoferrato, A.-C. Utility of 2D-Ultrasound in Pelvic Floor Muscle Contraction and Bladder Neck Mobility Assessment in Women with Urinary Incontinence. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconer, C.; Ekman-Ordeberg, G.; Blomgren, B.; Johansson, O.; Ulmsten, U.; Westergren-Thorsson, G.; Malmström, A. Paraurethral Connective Tissue in Stress-Incontinent Women after Menopause. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1998, 77, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, H.P.; Lanzarone, V. Levator Trauma After Vaginal Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, H.P. Pelvic Floor Ultrasound: A Review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzkamp, J.M.; Schäfer, S.D.; Amler, S.; Strube, F.; Kiesel, L.; Schmitz, R. Strain Elastography as a New Method for Assessing Pelvic Floor Biomechanics. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, T.; Mitranovici, M.-I.; Moraru, L.; Costachescu, D.; Caravia, L.G.; Bernad, E.; Ivan, V.; Apostol, A.; Munteanu, M.; Puscasiu, L. Innovations in Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLancey, J.O.L.; Masteling, M.; Pipitone, F.; LaCross, J.; Mastrovito, S.; Ashton-Miller, J.A. Pelvic Floor Injury during Vaginal Birth Is Life-Altering and Preventable: What Can We Do about It? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, 279–294.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Hu, P.; Ran, S.; Tang, J.; Xiao, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Rong, Y.; Liu, M. Association Between Urinary Stress Incontinence and Levator Avulsion Detected by 3D Transperineal Ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2023, 44, e39–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.; Barr, R.; Farrokh, A.; Dighe, M.; Hocke, M.; Jenssen, C.; Dong, Y.; Saftoiu, A.; Havre, R. Strain Elastography—How To Do It? Ultrasound Int. Open 2017, 3, E137–E149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, J.; Cosgrove, D.; Dietrich, C.; Fromageau, J.; Bojunga, J.; Calliada, F.; Cantisani, V.; Correas, J.-M.; D’Onofrio, M.; Drakonaki, E.; et al. EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Ultrasound Elastography. Part 1: Basic Principles and Technology. Ultraschall Med. 2013, 34, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennisson, J.-L.; Deffieux, T.; Fink, M.; Tanter, M. Ultrasound Elastography: Principles and Techniques. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2013, 94, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, M. Association between Elastography Findings of the Levator Ani and Stress Urinary Incontinence. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petros, P. Changes in Bladder Neck Geometry and Closure Pressure after Midurethral Anchoring Suggest a Musculoelastic Mechanism Activates Closure. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2003, 22, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wen, L.; Chen, W.; Qing, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, M. A Preliminary Study on Quantitative Quality Measurements of the Urethral Rhabdosphincter Muscle by Supersonic Shear Wave Imaging in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okcu, N.T.; Vuruskan, E.; Gorgulu, F.F. Use of Shear Wave Elastography to Evaluate Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 31, 1196–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptaszkowski, K.; Małkiewicz, B.; Zdrojowy, R.; Paprocka-Borowicz, M.; Ptaszkowska, L. Assessment of the Elastographic and Electromyographic of Pelvic Floor Muscles in Postmenopausal Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence Symptoms. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.M.; Zhang, L.M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q.Y.; Zhao, C.; Fang, S.B.; Yang, Z.L. Usefulness of Transperineal Shear Wave Elastography of Levator Ani Muscle in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Abdom. Radiol. 2022, 47, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, G.; Huang, J.; Xiao, X.; Xie, Y. Association between Urethral Funneling in Stress Urinary Incontinence and the Biological Properties of the Urethral Rhabdosphincter Muscle Based on Shear Wave Elastography. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2023, 42, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Fang, S.; Yang, Z.; Sun, L. Assessment of Perineal Body Properties in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence Using Transperineal Shear Wave Elastography. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vicari, D.; Barba, M.; Costa, C.; Cola, A.; Frigerio, M. Assessment of Urethral Elasticity by Shear Wave Elastography: A Novel Parameter Bridging a Gap Between Hypermobility and ISD in Female Stress Urinary Incontinence. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton-Miller, J.A.; DeLANCEY, J.O.L. Functional Anatomy of the Female Pelvic Floor. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1101, 266–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, F.; Swenson, C.W.; DeLancey, J.O.L.; Chen, L. Novel 3D MRI Technique to Measure Perineal Membrane Structural Changes with Pregnancy and Childbirth: Technique Development and Measurement Feasibility. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, K.; Dietz, H. Intrapartum Risk Factors for Levator Trauma. BJOG 2010, 117, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rortveit, G.; Daltveit, A.K.; Hannestad, Y.S.; Hunskaar, S. Norwegian EPINCONT Study Urinary Incontinence after Vaginal Delivery or Cesarean Section. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; DeSautel, M.; Anderson, A.; Badlani, G.; Kushner, L. Collagen Synthesis Is Not Altered in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, B.; Pákozdy, K.; Lampé, R.; Berényi, E.; Takács, P. Ultrahang-elasztográfia alkalmazásának lehetőségei a szülészet-nőgyógyászatban. Orvosi Hetilap 2021, 162, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, C.; Ekman-Ordeberg, G.; Ulmsten, U.; Westergren-Thorsson, G.; Barchan, K.; Malmström, A. Changes in Paraurethral Connective Tissue at Menopause Are Counteracted by Estrogen. Maturitas 1996, 24, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, G. Associations of Blood and Urinary Heavy Metals with Stress Urinary Incontinence Risk Among Adults in NHANES, 2003–2018. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zheng, B.; Su, L.; Xiang, Y. Association of Plasma High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Level with Risk of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Retrospective Study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Reeves, J.; Shiri, R.; Hickling, D.; McLean, L. The Pathophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 501–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Guo, D. Advancements in Artificial Intelligence for Pelvic Floor Ultrasound Analysis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, X.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X. Artificial Intelligence Models Derived from 2D Transperineal Ultrasound Images in the Clinical Diagnosis of Stress Urinary Incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Author, Year | Modality |

|---|---|---|

| [12] | Kreutzkamp et al., 2017 | SE |

| [19] | Yu et al., 2021 | SE |

| [5] | Csákány et al., 2025 | SE |

| [20] | Petros, 2003 | Biomechanical concepts |

| [8] | Jamard et al., 2020 | Review |

| [21] | Zhao et al., 2020 | SWE |

| [22] | Okcu et al., 2021 | SWE |

| [23] | Ptaszkowski et al., 2021 | SWE |

| [24] | Li et al., 2022 | SWE |

| [25] | Wang et al., 2023 | SWE |

| [26] | Li et al., 2024 | SWE |

| [27] | De Vicari et al., 2025 | SWE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Csákány, L.; Surányi, A.; Kovács, F.; Várbíró, S.; Németh, G.; Keresztúri, A.; Pásztor, N. Strain Elastography in Urogynecology: Functional Imaging in Stress Urinary Incontinence. Women 2025, 5, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040048

Csákány L, Surányi A, Kovács F, Várbíró S, Németh G, Keresztúri A, Pásztor N. Strain Elastography in Urogynecology: Functional Imaging in Stress Urinary Incontinence. Women. 2025; 5(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleCsákány, Lóránt, Andrea Surányi, Flórián Kovács, Szabolcs Várbíró, Gábor Németh, Attila Keresztúri, and Norbert Pásztor. 2025. "Strain Elastography in Urogynecology: Functional Imaging in Stress Urinary Incontinence" Women 5, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040048

APA StyleCsákány, L., Surányi, A., Kovács, F., Várbíró, S., Németh, G., Keresztúri, A., & Pásztor, N. (2025). Strain Elastography in Urogynecology: Functional Imaging in Stress Urinary Incontinence. Women, 5(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040048