Abstract

We surveyed bee communities across an organic conifer tree farm landscape in northern Idaho to assess how managed forest–agriculture mosaics support pollinator diversity. Bees were collected from farm fields, adjacent conservation forests, and a pollinator garden between May and August 2024 using aerial nets and identified to species or morphospecies. In total, 94 bee species were recorded, representing a mix of ground-nesting (46%), cavity-nesting (37%), and social (17%) taxa. Bee richness was highest in farm fields (66 species), intermediate in forests (48 species), and lowest in the pollinator garden (35 species). Community turnover among habitats was substantial (Jaccard dissimilarity = 0.67–0.76; Bray-Curtis dissimilarity = 0.53–0.55), indicating distinct assemblages associated with each habitat type. Comparisons with regional datasets from Montana and Washington revealed moderate overlap (Jaccard = 0.22–0.24), suggesting that the Highland Flats farm supports a partly unique bee fauna within the Northern Rockies. Seven non-native bee species and nine species of conservation concern (five Osmia, four Bombus) were detected, with those of conservation concern taxa often visiting native Lupinus flowers. Most bee visits occurred on non-native plants, though native blooms contributed key seasonal resources. These findings demonstrate that organic tree farms with structurally diverse forests and managed floral resources can function as refugia for both common and at-risk bees in temperate forested landscapes.

1. Introduction

Awareness of bee diversity has dramatically increased in recent years, and countless studies have been published documenting bee communities in natural and agricultural landscapes [1,2,3,4]. However, most of the pollinator research in North America has focused on open habitats like grasslands, meadows and arid lands or on agricultural landscapes [5,6,7,8]; relatively less is known about bee communities in temperate coniferous forests [9,10,11,12]. Managed forest landscapes can offer floral and nesting resources in varying successional stages, with early postharvest or open-canopy conditions supporting higher bee richness and abundance [13,14]. More broadly, forests with greater compositional diversity, especially of insect-pollinated broadleaf trees and understory shrubs embedded within conifers, tend to support more bee species [15]. Some studies also show that forest thinning and restoration treatments can enhance pollinator richness by increasing understory floral diversity and microhabitat heterogeneity [14]. However, gaps remain in how forest pollinators respond in forestry systems, particularly in regions of the western U.S. [12,16].

Although some research has been conducted investigating pollinators in managed forests [9,10,11,12], even less is known about bee communities on tree farms, such as Christmas tree plantations or agroforestry systems, which sit at the interface between forestry and agriculture. These systems may provide unique pollinator habitats when managed with structural and floral complexity [17]. The literature on bees in tree farms is sparse [18,19], but preliminary unpublished work indicates that maintaining groundcover plantings, flowering borders, and non-crop floral resources can increase pollinator diversity and abundance on Christmas tree farms [20]. More broadly, temperate agroforestry systems (i.e., the intentional integration of trees and/or shrubs with crops) can benefit insect pollinators by providing foraging habitat, enhancing connectivity, and reducing pesticide exposure [21,22]. Organic and low-input farming practices often reduce pesticide pressure, promote floral diversity and support soil and habitat features favorable for wild bees [23,24]. Such systems are increasingly recognized as important components of pollinator-friendly landscapes [25]. While no studies that we are aware of have investigated the effect of organic farming practices on tree farms on pollinators, conventionally grown Christmas tree plantations were found to have significantly less plant species richness than organic Christmas tree plantations [26]. Pollinator diversity in coniferous forests is higher in open canopy areas [14]. Therefore, landscapes where tree farms are bordered by natural or semi-natural habitat, well-managed farms may serve as pollinator corridors or refugia. Herein, we present a survey of bee communities on an organic tree farm in northern Idaho, sampling in farm fields, forest patches, and a pollinator garden. Our objectives are to quantify bee species richness on these farms and to compare species richness among habitats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

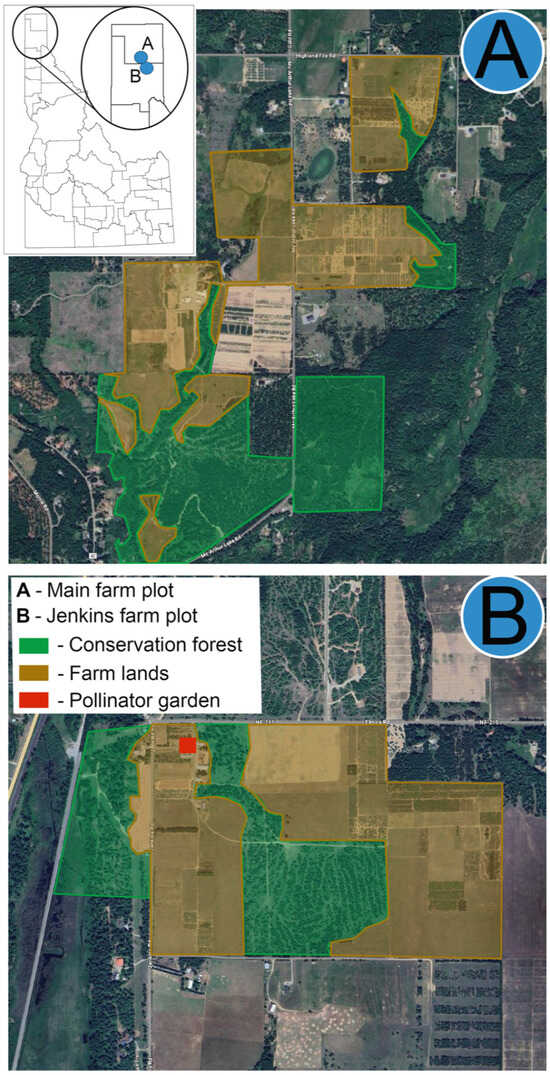

The Highland Flats Tree Farm and Distillery, in Naples, Idaho, is a large (over 300 hectare) organic evergreen farm that grows a variety of coniferous trees for essential oil production. Crops include blue spruce (Picea pungens), grand fir (Abies grandis) and white fir (Abies concolor). The Highland Flats farm practices organic, regenerative agriculture with an extended focus on regenerative forestry management. In addition to the organic practices, the farm employs minimum tillage and uses cover crops to protect and provide habitat for pollinators. The farm also created a 1500 square meter pollinator garden and monarch waystation to further support native pollinators. Over 30% of the farm is made up of native conservation forest corridors that are managed to support only native trees and shrubs. The Highland Flats farm consists of two different plots of land (Figure 1). One outside of Naples, Idaho (Main farm: 48.577636°, −116.446133°) and another about 12 km to the south near Elmira, Idaho (Jenkins: 48.472241°, −116.459447°). Both farm plots contain agricultural lands with fields of conifer seedlings and mature tree rows, as well as patches of conservation forest lands. The previously mentioned pollinator garden was established with primarily native plants at the Jenkins farm plot.

Figure 1.

Map of the two study sites in northern Idaho showing the locations of (A) the main farm plot and (B) the Jenkins farm plot. Green areas represent conservation forest habitats, and yellow areas indicate agricultural farmlands. The inset map shows the relative positions of the two sites within Idaho.

The conservation forest areas on the farm consist of a mixture of native trees averaging twenty to fifty years old, including species such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), grand fir (Abies grandis), western larch (Larix occidentalis), western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and western white pine (Pinus monticola). The understory is a diverse mix of shrubs, ferns and flowers, including creeping Oregon grape (Mahonia repens), snow berry (Symphoricarpos albus), lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina), trillium (Trillium ovatum), and wild strawberries (Fragaria virginiana). This forestland is specifically managed as a conservation area, encouraging native plant species and removing non-native species.

The cultivated portions of Highland Flats farm include row crops of grand fir (Abies grandis), blue spruce (Picea pungens), white fir (Abies concolor), douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) with varying ages of two to twenty years old and stands averaging between six inches and fifty feet. There is a diverse mix of perennial cover crops dispersed between the planted rows containing nitrogen fixers such as clover and various grasses for encouraging soil diversity and health. Several annual flowers also bloom among the crops, including oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) and large-leaved lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). The crop rotation among tree stands is on a longer cycle of twenty to thirty years.

2.2. Bee Sampling

All pollinator sampling took place from May through August of 2024, coinciding with blooms at the farm. At each collection event, two trained collectors opportunistically collected bees across the farm area, making efforts to collect bees from all the different blooming plants in the area. Collection events occurred in late May, Late June, and Early August. Approximately equal collection effort was devoted to the farmlands, the adjacent conservation forest lands, and the pollinator garden. During each collection event, five sites were visited by both collectors for four hours each. The sites were at the main farm site (farmland and forest land), the Jenkins site (farmland and forest land) and the pollinator garden. As the farm and forest locations are expansive, collectors meandered randomly through the collection areas for the allotted time (four hours) and collected bees as they encountered them. All collections occurred between 09:00 and 15:00 to coincide with the flight times for most bees. Bees were collected using aerial nets, euthanized, and preserved so specimens could be identified to species (or morphospecies) using regional keys and reference collections. Floral hosts were identified using images and online resources like iNaturalist.org, so pollinator/plant relationships could be made.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Spatial turnover (β-diversity) of bee communities among the farm, forest, and pollinator garden habitats was quantified using pairwise Jaccard dissimilarity (presence–absence data) and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (presence-absence and abundance). We then used PERMANOVA (adonis) with 999 permutations to test whether community composition differed significantly among habitats. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.5.1) using the vegan package. We also compared the bee community from the Highland Flats farm to two other regional bee communities. Spatial turnover was quantified using pairwise Jaccard dissimilarity to compare our species list to a study of bees from a western Montana ranch [27] and a list of bees known from the Northern Rockies ecoregion extracted from the study of bees in Washington state [28].

3. Results

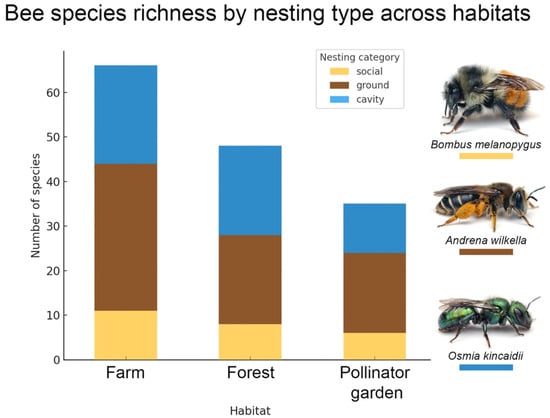

We recorded a total of 94 bee species (including morphospecies) representing 24 genera across the Highland Flats Farm. A total of 71 bee species were recorded at the main farm site, and 61 were recorded at the Jenkins farm plot, with 35 species recorded from the pollinator garden (Appendix A, Table A1). Overall, more bee species were found on the agricultural portions of the Highland Flats farm than in the conservation forests, with 66 species collected from the farm fields and 48 species collected from the conservation forests (Figure 2). Of the bee species collected from the farm fields, 50% (n = 33) of them are known to be ground nesting species, 33% (n = 22) are cavity nesting species, and nearly 17% (n = 11) are eusocial species (e.g., Bombus and Apis) (Figure 2). In the forest areas, there was an equal number of ground and cavity nesting species in the bee community found there, with nearly 42% (n = 20) of species nesting in the ground, 42% (n = 20) nesting in pre-existing cavities, and nearly 17% (n = 8) being social (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bee species richness by nesting type across habitats at the Highland Flats Farm, Idaho. Bars show the number of bee species that are social (yellow), ground-nesting (brown), or cavity-nesting (blue) within each habitat. Representative species are shown at right: Bombus melanopygus (social), Andrena wilkella (ground-nesting), and Osmia kincaidii (cavity-nesting).

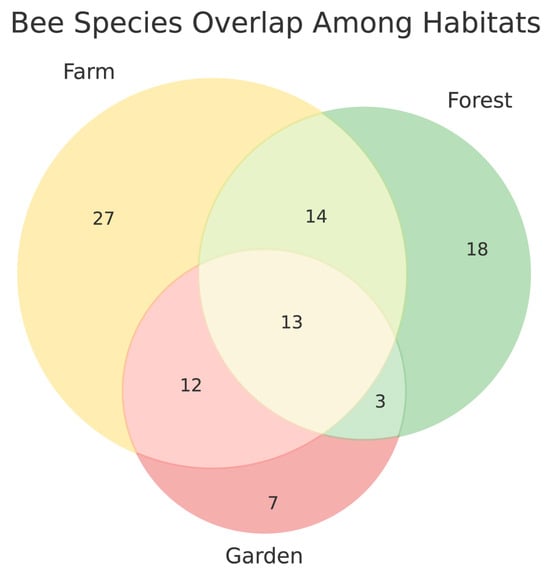

Bee community composition differed substantially among habitats. Pairwise Jaccard dissimilarity values ranged from 0.67 to 0.76 among the farm, forest, and pollinator garden habitats, indicating that only about one-quarter to one-third of the bee species were shared between any two habitats. The farm and forest habitats were somewhat more similar (Jaccard = 0.69) than either was to the pollinator garden (0.67–0.76). Bray–Curtis dissimilarities, which incorporate species abundances, showed a comparable pattern (0.53–0.55), suggesting that differences among habitats were driven both by species turnover and by shifts in relative abundances. Together, these results indicate relatively high compositional turnover among habitats, with distinct bee assemblages associated with each habitat type (Figure 3). Of the species that appeared to be unique to each habitat, the majority were represented by only a single collected specimen. Specifically, 22 of the 27 farm-unique species, 12 of the 18 forest-unique species, and 6 of the 7 garden-unique species were singletons. This pattern suggests that much of the apparent habitat exclusivity reflects low detection rather than true habitat specialization, although these rare occurrences still highlight the value of sampling across multiple habitat types.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram illustrating overlap in bee species among the three primary habitat types sampled at the Highland Flats farm. Farm sites supported the highest number of unique species (27), followed by forest sites (18) and the pollinator garden (7). Fourteen species were shared between farm and forest habitats, 12 species were shared between farm and the pollinator garden, and only 3 species were shared between forest and garden habitats. Thirteen species occurred across all three habitats. These patterns highlight both the distinctiveness of each habitat type and the complementary role they play in supporting overall bee diversity on the farms.

However, PERMANOVA (adonis) tests based on Jaccard distances (F = 1.16, R2 = 0.54, p = 0.34) and Bray–Curtis distances (F = 0.73, R2 = 0.49, p = 0.94) indicated no statistically significant difference in bee community composition among the farm, forest, and pollinator garden habitats. This lack of significance likely reflects the limited number of replicate sampling units (n = 5) rather than true similarity in community structure. Combined with the pairwise dissimilarity results, these findings suggest that bee assemblages differ moderately among habitats, but the differences were not statistically distinguishable given the small sample size.

No published comprehensive bee checklists exist for Idaho. However, comparison of the bee assemblage at the Highland Flats Farm with nearby studies revealed moderate similarity in species composition, suggesting that the farm supports a partly distinct community within the Northern Rockies region. Based on species richness, the Highland Flats Farm shared 58 species with the Montana ranch dataset (Jaccard similarity = 0.26) and 45 species with the Washington Northern Rockies list (Jaccard similarity = 0.24). Although some overlap was observed, each comparison indicated that roughly three-quarters of the combined species pool was unique to one location. These results suggest that while the Idaho farm supports many regionally widespread taxa, it also contains a notable number of species not reported from the nearby datasets (28 species), indicating that the farm’s bee community represents a somewhat unique assemblage within the Northern Rockies.

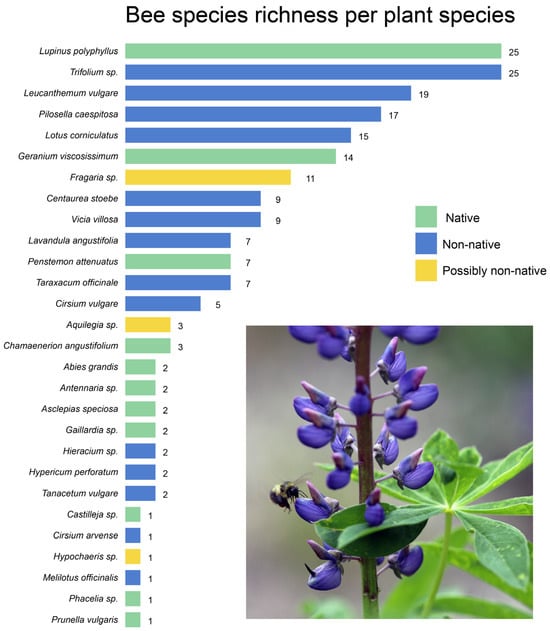

At the Highland Flats farm, bees were collected from a total of 28 different plant species (Figure 4). Of the 28 plant species that bees were collected on, 17 of them are not native or likely not native to the area (Figure 4). In fact, four of the five plant species that supported the highest bee richness were not native, with Lupinus polyphllus being the only native plant to support over 15 bee species. Non-native flowers represented the majority of the floral richness in both the farm areas and the conservation forests. In the farm areas, over 77% of the flowers that bees were collected on were not native, and 60% of the flowers bees were collected on in the forest areas were not native.

Figure 4.

Bee species richness hosted by each plant species surveyed at the Highland Flats study sites. Bars are ordered by richness, and colors represent plant native-status categories (green = native, blue = non-native, yellow = possibly non-native). Several non-native and naturalized species supported notably high bee richness, including Trifolium sp., Lupinus polyphyllus, Leucanthemum vulgare, and Pilosella caespitosa.

Of the 94 bee species recorded from the Highland Flats Farm, seven species are not native to North America (Apis mellifera, Andrena wilkella, Anthidium manicatum, Anthidium oblongatum, Megachile apicalis, Lasioglossum zonulum and Lasioglossum leucozonium). These seven non-native bees were found across all collection sites (farm, forest, and pollinator garden); however, the vast majority of non-native bee species (over 50% of specimens) were collected at the Highland Flats farm plot. Overall, most of the non-native bee specimens were encountered on the farm plots (63.5%), with much fewer found at the pollinator garden (18.8%) or the forest plots (17.7%). Most of the introduced bee species were collected on non-native flowers, with only three (Apis mellifera, Andrena wilkella, and Lasioglossum zonulum) being found also visiting native flowers.

Several of the bee species we detected at the Highland Flats Farm are considered to be at risk by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game [29]. These include four Bumble bee species (Bombus appositus, B. melanopygus, B. occidentalis, and B. vagans) and five Osmia species (O. albolateralis, O. atrocyanea, O. coloradensis, O. pusilla, and O. simillima). These at-risk species were relatively equally distributed across different habitats, with eight species found in the agricultural portions of the farm, six species found in the conservation forest areas, and six species found in the pollinator garden. Most of the at-risk species were found visiting both native and non-native plants. However, Osmia atrocyanea and Bombus occidentalis (which is considered a species of greatest concern) were only found visiting native Lupinus flowers.

4. Discussion

This study documented a diverse bee assemblage (94 species) within an organic conifer tree farm landscape in northern Idaho. Bee richness was highest in farm fields, intermediate in conservation forests, and lowest in the pollinator garden (Figure 2). Distinct assemblages were associated with each habitat, with roughly only one-quarter to one-third of species shared between any two habitats. These findings highlight that even within a single managed property, habitat heterogeneity positively structures bee communities, which has been found in several other studies (e.g., [30,31,32]).

Higher bee richness in the farm areas likely reflects greater floral abundance and open-canopy conditions that favor ground-nesting and social bees. In contrast, forest habitats supported a different suite of species, including a higher proportion of cavity-nesting taxa, suggesting that shaded and woody environments remain important components of the broader landscape mosaic, especially for providing nesting habitat for cavity-nesting bees [9,33]. Together, the farm and forest habitats appear to provide complementary resources that collectively support greater overall diversity, which is consistent with studies showing that heterogeneous forest landscapes sustain richer pollinator communities [13,14].

Regional comparisons further indicate that the Highland Flats farm harbors a partly distinct bee fauna within the Northern Rockies. Only about 22–24% of species were shared with the Montana dataset (194 total bee species: approximately 250 km southeast of our study site) and the Washington dataset (137 total bee species: roughly 100 km west of our study site), implying a high proportion of site-specific taxa. This likely reflects Idaho’s under-sampled bee fauna, combined with local habitat and management differences. The presence of numerous species not reported from neighboring studies underscores the conservation value of documenting bees in underrepresented forest–agriculture systems.

In this study, bees were collected from 28 flowering plant species, most of which were non-native ornamentals or cover crops. Although non-native flowers dominated bee visitation, they provided valuable foraging resources that likely extended bloom availability across the season. Nevertheless, native species such as Lupinus polyphyllus supported high bee richness and should be prioritized in restoration plantings. Maintaining a mixture of native and non-native blooms may maximize diversity while supporting native specialists [34].

Seven non-native bee species were recorded, primarily in farm habitats and largely associated with non-native flowers. Many of these introduced taxa are widespread and have been documented across North America. However, while Andrena wilkella has been widely documented across eastern North America, until now it was not known west of the Rocky Mountains. These introduced bee species may compete with native bees for nesting or floral resources [35,36]. Continued monitoring will be important to track whether non-native abundance increases or displaces natives over time.

Several at-risk species were also found, including four Bombus and five Osmia species recognized by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game [29]. Perhaps most notably, Bombus occidentalis, a species of greatest conservation concern, was observed only on native Lupinus flowers. Interestingly, one B. occidentalis individual was found in the agricultural portions of the Highland Flats farm, and the other was found visiting Lupine in the pollinator garden at the Jenkins farm. The detection of multiple species of conservation concern across habitats emphasizes the importance of organic and regenerative forestry systems as refugia for declining bees.

The findings of this study suggest that organic tree farms can contribute meaningfully to pollinator conservation when managed to maintain habitat heterogeneity, native floral resources, and nesting substrates. Practices such as minimizing soil disturbance, retaining coarse woody debris, and establishing native flowering strips can enhance pollinator value within tree-based agroecosystems.

While the sampling represented only one season and a limited number of plots, this study provides a baseline for future monitoring in Idaho’s managed forest landscapes. Expanding temporal coverage would likely uncover additional bee species. Also, future studies should investigate how bee communities differ between organic and conventional tree farms.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the Highland Flats Tree Farm supports a rich (94 species) and regionally distinctive bee fauna, including both widespread species and species of conservation concern. The farm’s organic and regenerative practices, including the conservation forest intertwined with agriculture, support a diverse bee community, with forest and farm habitats supporting complementary bee communities. With intentional management emphasizing native vegetation and reduced chemical inputs, such farms can play an important role in sustaining pollinators across the Northern Rockies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.W., L.T.W., T.M.W. and Z.R.; methodology, J.S.W. and L.T.W.; formal analysis, J.S.W.; investigation, J.S.W., L.T.W., T.M.W., Z.R. and M.C.; resources, Z.R. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.W.; writing—review and editing, J.S.W., L.T.W., T.M.W., Z.R. and M.C.; visualization, J.S.W.; funding acquisition, J.S.W., L.T.W. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Young Living Essential Oils.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is provided within the current manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Highland Flats Farm for supporting this research. We also thank Isaac Wilson for his help with collections and other field work and Skylar Burrows for help with bee identification.

Conflicts of Interest

Tyler M. Wilson, Michael Carter, and Zabrina Ruggles are employed by the funding entity, Young Living Essential Oils. However, the remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funding entity had no role in the design of the study, nor in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Bee species collected across the Highland Flats farm study. Columns show family, bee species, total abundance, areas where each species was recorded (MF = Main farm site; CF = Main farm conservation forest; PG = Pollinator Garden; JF = Jenkins farm site; JCF = Jenkins conservation forest), nesting strategy (ground, cavity, or social), and floral host(s).

Table A1.

Bee species collected across the Highland Flats farm study. Columns show family, bee species, total abundance, areas where each species was recorded (MF = Main farm site; CF = Main farm conservation forest; PG = Pollinator Garden; JF = Jenkins farm site; JCF = Jenkins conservation forest), nesting strategy (ground, cavity, or social), and floral host(s).

| Family | Species | Abundance | Areas | Nesting Strategy | Floral Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrenidae | Andrena angustitarsata | 1 | MF | Ground | Fragaria sp. |

| Andrenidae | Andrena candida | 3 | MF, JF, PG | Ground | Pilosella caespitosa, Trifolium sp. |

| Andrenidae | Andrena evoluta | 1 | MF | Ground | Air/Ground |

| Andrenidae | Andrena melanochroa | 6 | MF | Ground | Air/Ground, Fragaria sp. |

| Andrenidae | Andrena miranda | 4 | CF, JCF | Ground | Antennaria sp., Leucanthemum vulgare |

| Andrenidae | Andrena nigrocaerulea | 1 | PG | Ground | Geranium viscosissimum |

| Andrenidae | Andrena nivalis | 1 | MF | Ground | Fragaria sp. |

| Andrenidae | Andrena prunorum | 9 | MF, JF | Ground | Abies grandis, Centaurea stoebe, Leucanthemum vulgare |

| Andrenidae | Andrena salicifloris | 1 | MF | Ground | Fragaria sp. |

| Andrenidae | Andrena sp. | 1 | CF | Ground | Pilosella caespitosa |

| Andrenidae | Andrena vicinoides | 9 | MF, PG | Ground | Geranium viscosissimum, Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Andrenidae | Andrena wilkella | 50 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Ground | Air/Ground, Antennaria sp., Geranium viscosissimum, Lotus corniculatus, Lupinus polyphyllus, Pilosella caespitosa, Taraxacum officinale, Trifolium sp., Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Anthophora ursina | 1 | PG | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Apidae | Apis mellifera | 8 | MF, JF, PG | Social | Centaurea stoebe, Lavandula angustifolia, Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Bombus appositus | 8 | CF, MF, JCF, JF | Social | Asclepias speciosa, Lavandula angustifolia, Trifolium sp., Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Bombus bifarius | 105 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Social | Air/Ground, Aquilegia sp., Centaurea stoebe, Chamaenerion angustifolium, Cirsium arvense, Fragaria sp., Geranium viscosissimum, Hypericum perforatum, Lavandula angustifolia, Leucanthemum vulgare, Lotus corniculatus, Lupinus polyphyllus, Melilotus officinalis, Penstemon attenuatus, Tanacetum vulgare, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Bombus centralis | 1 | MF | Social | Cirsium vulgare |

| Apidae | Bombus flavifrons | 5 | MF, JCF | Social | Lavandula angustifolia, Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Bombus melanopygus | 8 | MF, JCF, JF, PG | Social | Lavandula angustifolia, Lotus corniculatus, Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Bombus mixtus | 12 | CF, MF, PG | Social | Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Bombus nevadensis | 3 | MF, JCF | Social | Asclepias speciosa, Lupinus polyphyllus, Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Bombus occidentalis | 2 | MF, PG | Social | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Apidae | Bombus rufocinctus | 4 | CF, MF, JCF, PG | Social | Centaurea stoebe, Lotus corniculatus, Lupinus polyphyllus, Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Bombus vagans | 16 | CF, MF, JCF, JF | Social | Cirsium vulgare, Hypericum perforatum, Lavandula angustifolia, Lotus corniculatus, Prunella vulgaris, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Ceratina acantha | 15 | CF, MF, PG | Cavity | Air/Ground, Fragaria sp., Gaillardia sp., Leucanthemum vulgare, Penstemon attenuatus, Pilosella caespitosa |

| Apidae | Ceratina nanula | 2 | MF, PG | Cavity | Penstemon attenuatus, Pilosella caespitosa |

| Apidae | Eucera frater | 21 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Ground | Air/Ground, Geranium viscosissimum, Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp., Vicia villosa |

| Apidae | Melecta pacifica | 1 | MF | Ground | Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Melissodes microsticta | 4 | JCF, PG | Ground | Centaurea stoebe, Geranium viscosissimum, Hypochaeris sp., Leucanthemum vulgare |

| Apidae | Melissodes rivalis | 2 | MF | Ground | Cirsium vulgare |

| Apidae | Neopasites nr. fulviventris | 2 | JCF | Ground | Air/Ground |

| Apidae | Nomada spp. | 18 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Ground | Abies grandis, Air/Ground, Geranium viscosissimum, Leucanthemum vulgare, Lupinus polyphyllus, Taraxacum officinale, Trifolium sp. |

| Apidae | Triepeolus subalpinus | 1 | JCF | Ground | Air/Ground |

| Colletidae | Hylaeus affinis | 1 | CF | Cavity | Pilosella caespitosa |

| Colletidae | Hylaeus nevadensis | 3 | CF | Cavity | Leucanthemum vulgare, Pilosella caespitosa |

| Halictidae | Agapostemon virescens | 3 | MF, JF, PG | Ground | Air/Ground, Gaillardia sp., Pilosella caespitosa |

| Halictidae | Dufourea holocyanea | 9 | JCF | Ground | Air/Ground, Vicia villosa |

| Halictidae | Dufourea trochantera | 5 | JCF | Ground | Air/Ground, Phacelia sp. |

| Halictidae | Halictus confusus | 2 | CF, MF | Ground | Air/Ground, Leucanthemum vulgare |

| Halictidae | Halictus farinosus | 5 | CF, MF, JCF, JF | Ground | Air/Ground, Leucanthemum vulgare, Pilosella caespitosa, Trifolium sp. |

| Halictidae | Halictus ligatus | 5 | CF, MF | Ground | Air/Ground, Leucanthemum vulgare, Pilosella caespitosa |

| Halictidae | Halictus rubicundus | 1 | MF | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Halictus tripartitus | 1 | MF | Ground | Fragaria sp. |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum (Dialictus) sp. 1 | 5 | JCF, PG | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum (Dialictus) sp. 2 | 1 | MF | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum (Dialictus) spp. | 1 | MF | Ground | Lotus corniculatus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum albipenne | 3 | MF, PG | Ground | Leucanthemum vulgare, Pilosella caespitosa, Taraxacum officinale |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum albohirtum | 2 | JCF | Ground | Leucanthemum vulgare |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum anhypops | 3 | MF, PG | Ground | Aquilegia sp., Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum diatretum | 4 | MF, PG | Ground | Geranium viscosissimum, Lupinus polyphyllus, Taraxacum officinale |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum egregium | 1 | PG | Ground | Pilosella caespitosa |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum inconditum | 16 | CF, MF, PG | Ground | Aquilegia sp., Leucanthemum vulgare, Lupinus polyphyllus, Penstemon attenuatus, Pilosella caespitosa, Taraxacum officinale |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum leucozonium | 3 | MF, JCF, PG | Ground | Hieracium sp., Pilosella caespitosa, Taraxacum officinale |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum nevadense | 9 | CF, MF, JCF, JF | Ground | Air/Ground, Hieracium sp., Leucanthemum vulgare, Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp. |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum nr. pulveris | 1 | MF | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum olympiae | 1 | PG | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum ovaliceps | 1 | MF | Ground | Castilleja sp. |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum perpunctatum | 11 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Ground | Geranium viscosissimum, Leucanthemum vulgare, Pilosella caespitosa, Taraxacum officinale |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum punctatoventre | 1 | MF | Ground | Air/Ground |

| Halictidae | Lasioglossum zonulum | 1 | MF | Ground | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Halictidae | Sphecodes spp. | 20 | CF, MF, JCF, JF | Ground | Air/Ground, Fragaria sp., Leucanthemum vulgare, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Anthidium manicatum | 7 | MF, JF | Cavity | Lavandula angustifolia |

| Megachilidae | Anthidium oblongatum | 17 | CF, MF | Cavity | Air/Ground, Lotus corniculatus, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Anthidium utahense | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Centaurea stoebe |

| Megachilidae | Coelioxys sodalis | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Air/Ground |

| Megachilidae | Heriades carinata | 6 | CF, MF | Cavity | Cirsium vulgare, Lotus corniculatus |

| Megachilidae | Hoplitis albifrons | 2 | PG | Cavity | Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Hoplitis grinnelli | 6 | CF, MF, JF | Cavity | Air/Ground, Leucanthemum vulgare, Lotus corniculatus |

| Megachilidae | Hoplitis hypocrita | 2 | MF, PG | Cavity | Lupinus polyphyllus, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Hoplitis producta | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Hoplitis sambuci | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Megachilidae | Megachile angelarum | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Chamaenerion angustifolium |

| Megachilidae | Megachile apicalis | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Centaurea stoebe |

| Megachilidae | Megachile dentitarsus | 1 | MF | Cavity | Centaurea stoebe |

| Megachilidae | Megachile frigida | 1 | CF | Cavity | Lotus corniculatus |

| Megachilidae | Megachile gemula | 1 | MF | Cavity | Lotus corniculatus |

| Megachilidae | Megachile melanophaea | 4 | MF, JCF, JF | Cavity | Air/Ground, Lotus corniculatus, Vicia villosa |

| Megachilidae | Megachile montivaga | 1 | MF | Cavity | Cirsium vulgare |

| Megachilidae | Megachile perihirta | 4 | CF, JCF, PG | Cavity | Chamaenerion angustifolium, Leucanthemum vulgare, Tanacetum vulgare |

| Megachilidae | Megachile relativa | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Centaurea stoebe |

| Megachilidae | Osmia (Acanthosmioides) sp. 1 | 1 | MF | Cavity | Fragaria sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia (Acanthosmioides) sp. 2 | 1 | MF | Cavity | Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia (Acanthosmioides) sp. A | 6 | MF, JF, PG | Cavity | Geranium viscosissimum, Lotus corniculatus, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia (Acanthosmioides) sp. B | 1 | JCF | Cavity | Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia (Acanthosmioides) sp. C | 1 | JF | Cavity | Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia albolateralis | 21 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Cavity | Air/Ground, Geranium viscosissimum, Lotus corniculatus, Penstemon attenuatus, Pilosella caespitosa, Trifolium sp., Vicia villosa |

| Megachilidae | Osmia atrocyanea | 1 | PG | Cavity | Lupinus polyphyllus |

| Megachilidae | Osmia coloradensis | 3 | CF, MF | Cavity | Fragaria sp., Pilosella caespitosa |

| Megachilidae | Osmia kincaidii | 1 | PG | Cavity | Geranium viscosissimum |

| Megachilidae | Osmia lignaria | 1 | MF | Cavity | Fragaria sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia pusilla | 21 | CF, MF, JCF, JF, PG | Cavity | Air/Ground, Geranium viscosissimum, Lotus corniculatus, Penstemon attenuatus, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Osmia simillima | 5 | MF, PG | Cavity | Geranium viscosissimum, Penstemon attenuatus, Trifolium sp. |

| Megachilidae | Stelis cf. foederalis sp. 6 | 1 | MF | Cavity | Air/Ground |

| Megachilidae | Stelis mono | 3 | MF | Cavity | Air/Ground, Leucanthemum vulgare |

References

- Potts, S.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W.E. Global pollinator declines: Trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, R.; Bartomeus, I.; Cariveau, D.P. Native pollinators in anthropogenic habitats. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, T.A.H.; Goodell, K. The role of resources and risks in regulating wild bee populations. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Winfree, R.; Aizen, M.A.; Bommarco, R.; Cunningham, S.A.; Kremen, C.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Harder, L.D.; Afik, O.; et al. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 2013, 339, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkle, L.A.; Alarcón, R. The future of plant–pollinator diversity: Understanding interaction networks across time, space, and global change. Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgers-Kelly, A.C.; Richards, M.H. Effect of meadow regeneration on bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) abundance and diversity in southern Ontario, Canada. Can. Entomol. 2013, 145, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carril, O.M.; Griswold, T.; Haefner, J.; Wilson, J.S. Wild bees of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: Richness, abundance, and spatio-temporal beta-diversity. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, C.S.; Frier, S.D.; Dumesh, S. The bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea, Apiformes) of the Prairies Ecozone, with comparisons to other grasslands of Canada. Arthropods Can. Grassl. 2014, 4, 427–467. [Google Scholar]

- Ulyshen, M.; Urban-Mead, K.R.; Dorey, J.B.; Rivers, J.W. Forests are critically important to global pollinator diversity and enhance pollination in adjacent crops. Biol. Rev. 2023, 98, 1118–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitomer, R.A.; Galbraith, S.M.; Betts, M.G.; Moldenke, A.R.; Progar, R.A.; Rivers, J.W. Bee diversity decreases rapidly with time since harvest in intensively managed conifer forests. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 33, e2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, P.R.; Davis, T.S.; Tinkham, W.T.; Hoffman, C.M. Effects of seasonality, forest structure, and understory plant richness on bee community assemblage in a southern Rocky Mountain mixed conifer forest. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2018, 111, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, J.W.; Galbraith, S.M.; Cane, J.H.; Schultz, C.B.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Kormann, U.G. A review of research needs for pollinators in managed conifer forests. J. For. 2018, 116, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, J.W.; Betts, M.G. Postharvest bee diversity is high but declines rapidly with stand age in regenerating Douglas-fir forest. For. Sci. 2021, 67, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.S.; Loffland, H.L.; Looney, C.E.; Siegel, R.B. Mechanical thinning and prescribed fire benefit bumble bees and butterflies in a northern California conifer forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 588, 122758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traylor, C.R.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Bragg, D.C.; McHugh, J.V. Forest bees benefit from compositionally diverse broadleaf canopies. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 566, 122051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ealy, N.; Pawelek, J.; Hazlehurst, J. Effects of forest management on native bee biodiversity under the tallest trees in the world. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.B.; Webster, T. Apiculture and forestry (bees and trees). Agrofor. Syst. 1995, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyshen, M.D.; Ballare, K.M.; Fettig, C.J.; Rivers, J.W.; Runyon, J.B. The value of forests to pollinating insects varies with forest structure, composition, and age. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, H.; Inoue, T.; Tanaka, H.; Makihara, H.; Sueyoshi, M.; Isono, M.; Okabe, K. Responses of community structure, diversity, and abundance of understory plants and insect assemblages to thinning in plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidebottom, J. The Pollinator Study. NC State Extension: Christmas Trees, North Carolina State University. Available online: https://christmastrees.ces.ncsu.edu/christmastrees-pollinator-study/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Bentrup, G.; Hopwood, J.; Adamson, N.L.; Powers, R.; Vaughan, M. The role of temperate agroforestry practices in supporting pollinators. In Agroforestry and Ecosystem Services; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrup, G.; Hopwood, J.; Adamson, N.L.; Vaughan, M. Temperate agroforestry systems and insect pollinators: A review. Forests 2019, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A. Plant biodiversity enhances bees and other insect pollinators in agroecosystems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, E.H.; Illán, J.G.; Brousil, M.R.; Reganold, J.P.; Northfield, T.D.; Crowder, D.W. Long-term organic farming and floral diversity promotes stability of bee communities in agroecosystems. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Grass, I.; Wanger, T.C.; Westphal, C.; Batáry, P. Beyond organic farming–harnessing biodiversity-friendly landscapes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streitberger, M.; Fartmann, T. Phytodiversity in Christmas-tree plantations under different management regimes. Weed Res. 2021, 61, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, M.; Burrows, S. Checklist of bees (Apoidea) from a private conservation property in west-central Montana. Biodivers. Data J. 2017, 5, e11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, C.S.; Murray, E.A.; Bossert, S.; Gardner, J.; Looney, C. An annotated checklist of the bees of Washington state. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2024, 97, 1007–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Idaho Conservation Status (S-Rank). Idaho Species Catalog. Available online: https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa/explore?category=5 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Hofmann, S.; Everaars, J.; Schweiger, O.; Frenzel, M.; Bannehr, L.; Cord, A.F. Modelling patterns of pollinator species richness and diversity using satellite image texture. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martínez, C.; González-Estévez, M.A.; Cursach, J.; Lázaro, A. Pollinator richness, pollination networks, and diet adjustment along local and landscape gradients of resource diversity. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Núñez, C.; Kleijn, D.; Ganuza, C.; Heupink, D.; Raemakers, I.; Vertommen, W.; Fijen, T.P. Temporal and spatial heterogeneity of semi-natural habitat, but not crop diversity, is correlated with landscape pollinator richness. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappa, N.; Staab, M.; Ruppert, L.; Frey, J.; Bauhus, J.; Klein, A. Structural elements enhanced by retention forestry promote forest and non-forest specialist bees and wasps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 529, 120709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, A.; Armitage, J.; Bostock, H.; Perry, J.; Tatchell, M.; Thompson, K. EDITOR’S CHOICE: Enhancing gardens as habitats for flower-visiting aerial insects (pollinators): Should we plant native or exotic species? J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCroy, K.A.; Savoy-Burke, G.; Carr, D.E.; Delaney, D.A.; Roulston, T.A.H. Decline of six native mason bee species following the arrival of an exotic congener. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, J.M.; Hogendoorn, K. Mounting evidence that managed and introduced bees have negative impacts on wild bees: An updated review. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 2022, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.