The Potential of Vegetation for Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Protective Measures for the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus L.) on Arable Land

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Measures for the Protection of Northern Lapwing

2.3. Methodology of Vegetation Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AECM | Agri-Environmental Climatic Measures; |

| BR | Biological Relevance; |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy; |

| CCA | Canonical Correspondence Analysis; |

| CR | Czech Republic; |

| DCA | Detrended Correspondence Analysis; |

| EU | European Union; |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

References

- Chamberlain, D.E.; Fuller, R.J.; Bunce, R.G.H.; Duckworth, J.C.; Shrubb, M. Changes in the abundance of farmland birds in relation to the timing of agricultural intensification in England and Wales. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, P.F.; Green, R.E.; Heath, M.F. Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe’s farmland bird populations. Proc. R. Soc. B 2001, 268, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, P.F.; Sanderson, F.J.; Burfield, I.J.; Bommel, F.P.J. Further evidence of continent-wide impacts of agricultural intensification on European farmland birds, 1990–2000. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 116, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, D.; Vickery, J. Declining farmland birds: Evidence from large-scale monitoring studies in the UK. Br. Birds 2002, 95, 300–310. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, S.J.; Boccaccio, L.; Gregory, R.D.; Vorisek, P.; Norris, K. Quantifying the impact of land-use change to European farmland bird populations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 137, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PECBMS. Population Trends of Common European Breeding Birds 2013; PECBMS: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013; p. 2. Available online: https://pecbms.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/leaflet-pecbms-2013-compressed.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Calvi, G.; Campedelli, T.; Florenzano, G.T.; Rossi, P. Evaluating the benefits of agri-environment schemes on farmland bird communities through a common species monitoring programme. A case study in northern Italy. Agric. Syst. 2018, 160, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, B.J.; Doyle, S.; Mougeot, F.; Arroyo, B. The decline of ground nesting birds in Europe: Do we need to manage predation in addition to habitat? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 55, e03213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajíček, T.; Marada, P.; Horák, I.; Cukor, J.; Skoták, V.; Winkler, J.; Dumbrovský, M.; Jurčík, R.; Los, J. Mitigating the Negative Impact of Certain Erosion Events: Development and Verification of Innovative Agricultural Machinery. Agriculture 2025, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, V.; Zámečník, V.; Šálek, M. Survey of breeding Northern Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) in the Czech Republic in 2008: Results and effectiveness of volunteer work. Sylvia 2012, 48, 1–23. Available online: https://oldcso.birdlife.cz/www.cso.cz/wpimages/video/sylvia48_1Kubelka.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Zámečník, V. A Methodological Guide for the Practical Protection of Birds in Agricultural Landscapes; Agentura Ochrany Přírody A Krajiny: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013; p. 19. Available online: http://www.forumochranyprirody.cz/sites/default/files/19.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025). (In Czech)

- Delgado, J.A.; Short, N.M., Jr.; Roberts, D.P.; Vandenberg, B. Big data analysis for sustainable agriculture on a geospatial cloud framework. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Derpsch, R. Global spread of conservation agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 76, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoudi, V.; Sørensen, C.G.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Robotics and labour in agriculture. A context consideration. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 184, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šálek, M.; Hula, V.; Kipson, M.; Daňková, R.; Niedobová, J.; Gamero, A. Bringing diversity back to agriculture: Smaller fields and non-crop elements enhance biodiversity in intensively managed arable farmlands. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 90, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlio, A.; Kuussaari, M.; Heikkinen, R.K.; Arponen, A. Incorporating landscape heterogeneity into multi-objective spatial planning improves biodiversity conservation of semi-natural grasslands. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 49, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deák, B.; Rádai, Z.; Lukács, K.; Kelemen, A.; Kiss, R.; Bátori, Z.; Kiss, P.J.; Valkó, O. Fragmented dry grasslands preserve unique components of plant species and phylogenetic diversity in agricultural landscapes. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 4091–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshana, T.S.; Martin, E.A.; Sirami, C.; Woodcock, B.A.; Goodale, E.; Martínez-Núñez, C.; Lee, M.; Pagani-Núñez, E.; Raderschall, C.A.; Brotons, L.; et al. Crop and landscape heterogeneity increase biodiversity in agricultural landscapes: A global review and meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, T.G.; Vickery, J.A.; Wilson, J.D. Farmland biodiversity: Is habitat heterogeneity the key? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Simonson, S.E.; Stohlgren, T.J. Effects of spatial heterogeneity on butterfly species richness in Rocky Mountain National Park, CO, USA. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 739–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Münzenberg, U.; Bürger, C.; Thies, C.; Tscharntke, T. Scale-dependent effects of landscape structure on three pollinator guilds. Ecology 2002, 83, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Tscharntke, T. How does landscape context contribute to effects of habitat fragmentation on diversity and population density of butterflies? J. Biogeogr. 2003, 30, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, C.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Tscharntke, T. Effects of landscape context on herbivory and parasitism at different spatial scales. Oikos 2003, 101, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibull, A.C.; Östman, Ö.; Granqvist, A. Species richness in agroecosystems: The effect of landscape, habitat and farm management. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 1335–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.E.; Collins, S.J.; Crowe, S.; Girard, J.; Naujokaitis-Lewis, I.; Smith, A.C.; Lindsay, K.; Mitchell, S.; Fahrig, L. Effects of farmland heterogeneity on biodiversity are similar to—Or even larger than—The effects of farming practices. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 288, 106698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, A.L.; González-Gónzalez, C.; Van Cauwelaert, E.M.; Rosell, J.A.; Barrios, L.G.; Benítez, M. Landscape heterogeneity of peasant-managed agricultural matrices. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 292, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockermüller, E.; Kratschmer, S.; Pascher, K.; Hainz-Renetzeder, C.; Meimberg, H.; Frank, T.; Pachinger, B. Seasonal direct and indirect effects of local habitat and landscape factors on wild bees in agroecosytems. Biodivers. Conserv. 2025, 34, 3733–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y. The effect of landscape composition, complexity, and heterogeneity on bird richness: A systematic review and meta-analysis on a global scale. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, J.W.; Sparks, T.; Clarke, S.; Gobbett, K.; Glossop, S. Linear features and butterflies: The importance of green lanes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 80, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D.; Whittingham, M.J.; Bradbury, R.B. The management of crop structure: A general approach to reversing the impacts of agricultural intensification on birds? Ibis 2005, 147, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D.; Evans, A.D.; Grice, V.G. Bird Conservation and Agriculture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Lislevand, T.; Byrkjedal, I.; Heggøy, O.; Kålås, J.A. Population status, trends and conservation of meadow-breeding waders in Norway. Wader Study 2021, 128, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálsdóttir, A.E.; Þórisson, B.; Gunnarsson, T.G. Recent population changes of common waders and passerines in Iceland’s largest lowland region. Bird Study 2025, 72, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellesmark, S.; Ausden, M.; Blackburn, T.M.; Hoffmann, M.; McRae, L.; Visconti, P.; Gregory, R.D. The effect of conservation interventions on the abundance of breeding waders within nature reserves in the United Kingdom. Ibis 2023, 165, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, P.; Insley, H.; Siriwardena, G.; Buxton, N. The breeding success of a population of Lapwings in part of Strathspey 1996–1998. Scot. Birds 2000, 21, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Roodbergen, M.; van der Werf, B.; Hötker, H. Revealing the contributions of reproduction and survival to the Europe-wide decline in meadow birds: Review and metaanalysis. J. Ornithol. 2012, 153, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, V.; Sládeček, M.; Zámečník, V.; Vozabulová, E.; Šálek, M. Seasonality predicts egg size better than nesting habitat in a precocial shorebird. Ardea 2019, 107, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragten, S.; Nagel, J.C.; de Snoo, G.R. The effectiveness of volunteer nest protection on the nest success of Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus on Dutch arable farms. Ibis 2008, 150, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zámečník, V.; Kubelka, V.; Šálek, M. Visible marking of wader nests to avoid damage by farmers does not increase nest predation. Bird Conserv. Int. 2018, 28, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, D.; Wallander, J.; Larsson, M. Managing predation on ground-nesting birds: The effectiveness of nest exclosures. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüebler, M.U.; Schuler, H.; Horch, P.; Spaar, R. The effectiveness of conservation measures to enhance nest survival in a meadow bird suffering from anthropogenic nest loss. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 146, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferli, L.; Spaar, R.; Koller, A. Fence and plough for Lapwings: Nest protection to improve nest and chick survival in Swiss farmland. Osnabrücker Naturwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen 2006, 32, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kentie, R.; Both, C.; Hooijmeijer, J.C.E.W.; Piersma, T. Management of modern agricultural landscapes increases nest predation rates in Black-tailed Godwits (Limosa limosa). Ibis 2015, 157, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferli, L.; Rickenbach, O.; Koller, A.; Grüebler, M. Massnahmen zur Förderung des Kiebitzes Vanellus vanellus im Wauwilermoos (Kanton Luzern): Schutz der Nester vor Landwirtschaft und Prädation. Ornithol. Beob. 2009, 106, 311–326. Available online: https://www.ala-schweiz.ch/images/stories/pdf/ob/2009_106/OrnitholBeob_2009_106_311_Schifferli.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SZIF. Information for Applicants—Cap 2016 Agri-Environmental—Climate Measures (AECM); SZIF: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016. Available online: https://szif.gov.cz/cs/CmDocument?rid=%2Fapa_anon%2Fcs%2Fzpravy%2Fprv2014%2Faktuality%2F1460097102056.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Evans, D.M.; Pocock, M.J.O.; Brooks, J.; Memmott, J. Seeds in farmland food-webs: Resource importance, distribution and the impacts of farm management. Biol. Cons. 2011, 144, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejchar, L.; Clough, Y.; Ekroos, J.; Nicholas, K.A.; Olsson, O.L.A.; Ram, D.; Tschumi, M.; Smith, H.G. Net effects of birds in agroecosystems. BioScience 2018, 68, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olimpi, E.M.; Garcia, K.; Gonthier, D.J.; De Master, K.T.; Echeverri, A.; Kremen, C.; Sciligo, A.R.; Snyder, W.E.; Wilson-Rankin, E.E.; Karp, D.S. Shifts in species interactions and farming contexts mediate net effects of birds in agroecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Martinová, L.; Kotlánová, B.; Děkanovský, I.; Vaverková, M.D. Biological Relevance and Ecosystem Functions of Sugar Beet Weeds. Listy Cukrov. A Reparske 2025, 141, 98–103. Available online: http://www.cukr-listy.cz/on_line/2025/PDF/98-103.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Eglington, S.M.; Bolton, M.; Smart, M.A.; Sutherland, W.J.; Watkinson, A.R.; Gill, J.A. Managing water levels on wet grasslands to improve foraging conditions for breeding northern lapwing Vanellus vanellus. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.; Wotton, S.R.; Dillon, I.A.; Cooke, A.I.; Diack, I.; Drewitt, A.L.; Grice, P.V.; Gregory, R.D. Synergies between site protection and agri-environment schemes for the conservation of waders on lowland wet grasslands. Ibis 2014, 156, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.U.; Eilers, A.; Schimkat, M.; Krause-Heiber, J.; Timm, A.; Siegel, S.; Nachtigall, W.; Kleber, A. Factors influencing the success of within-field AES fallow plots as key sites for the Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus in an industrialised agricultural landscape of Central Europe. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 35, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konvicka, M.; Benes, J.; Cizek, O.; Kopecek, F.; Konvicka, O.; Vitaz, L. How too much care kills species: Grassland reserves, agri-environmental schemes and extinction of Colias myrmidone (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) from its former stronghold. J. Insect Conserv. 2008, 12, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, D.; Baquero, R.A.; Clough, Y.; Díaz, M.; De Esteban, J.; Fernández, F.; Gabriel, D.; Herzog, F.; Holzschuh, A.; Jöhl, R.; et al. Mixed biodiversity benefits of agri-environment schemes in five European countries. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, M.J. Will agri-environment schemes deliver substantial biodiversity gain, and if not why not? J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeuwer, A.; Berendse, F.; Willems, F.; Foppen, R.; Teunissen, W.; Schekkerman, H.; Goedhart, P. Do meadow birds profit from agri-environment schemes in Dutch agricultural landscapes? Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2949–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Finn, J.; Díaz, M.; Birkenstock, M.; Lakner, S.; Röder, N.; Kazakova, Y.; Šumrada, T.; Bezák, P.; Concepción, E.D.; et al. How can the European Common Agricultural Policy help halt biodiversity loss? Recommendations by over 300 experts. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, R.W.; Mason, L.R.; Conway, G.J.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Grice, P.V.; Cole, A.J.; Peach, W.J. Landscape context influences efficacy of protected areas and agri-environment scheme delivery for breeding waders. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korner, P.; Hohl, S.; Horch, P. Brood protection is essential but not sufficient for population survival of lapwings Vanellus vanellus in central Switzerland. Wildl. Biol. 2024, 4, e01175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevenini, D.; Cecere, J.G.; De Pascalis, F.; Tinarelli, R.; Kubelka, V.; Serra, L.; Pilastro, A.; Assandri, G. Habitat selection of the threatened northern lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) breeding in an intensive agroecosystem. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2025, 71, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech Geological Society. Geological Map of the Czech Republic, 1: 50,000; CGS: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018; Available online: https://mapy.geology.cz/geocr50 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Czech Geological Society. Map of Soil Types of the Czech Republic, 1: 50,000; CGS: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017; Available online: https://mapy.geology.cz/pudy (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Culek, M. (Ed.) Biogeographical Division of the Czech Republic (Biogeografické Členění České Republiky), 1st ed.; Enigma: Prague, Czech Republic, 1996; p. 347. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Chytrý, M.; Danihelka, J.; Kaplan, Z.; Wild, J.; Holubová, D.; Novotný, P.; Řezníčková, M.; Rohn, M.; Dřevojan, P.; Grulich, V.; et al. Pladias Database of the Czech Flora and Vegetation. Preslia 2021, 93, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.; Herbertsson, L.; Olofsson, J.; Olsson, P.A. Ecological indicator and traits values for Swedish vascular plants. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, C.J.F.; Šmilauer, P. Canoco Reference Manual and User’s Guide: Software for Ordination (Version 5.0); Microcomputer Power: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Bartolini, F.; Vergamini, D. Understanding the spatial agglomeration of participation in agri-environmental schemes: The case of the Tuscany Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, P.; Mozzato, D.; Defrancesco, E. Analysing the role of factors affecting farmers’ decisions to continue with agri-environmental schemes from a temporal perspective. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boetzl, F.A.; Krimmer, E.; Krauss, J.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Agri-environmental schemes promote ground-dwelling predators in adjacent oilseed rape fields: Diversity, species traits and distance-decay functions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdenbosch, H.; Brady, M.V.; Bimbilovski, I.; Swärd, R.; Manevska-Tasevska, G. Farm-level acceptability of contract attributes in agri-environment-climate measures for biodiversity conservation. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 112, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaix, C.; Moonen, A.C.; Dostatny, D.F.; Izquierdo, J.; Le Corff, J.; Morrison, J.; Von Redwitz, C.; Schumacher, M.; Westerman, P.R. Quantification of regulating ecosystem services provided by weeds in annual cropping systems using a systematic map approach. Weed Res. 2018, 58, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S.; Boursault, A.; Le Guilloux, M.; Munier-Jolain, N.; Reboud, X. Weeds in agricultural landscapes: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 31, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requier, F.; Odoux, J.F.; Tamic, T.; Moreau, N.; Henry, M.; Decourtye, A.; Bretagnolle, V. Honey bee diet in intensive farmland habitats reveals an unexpectedly high flower richness and a major role of weeds. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretagnolle, V.; Gaba, S. Weeds for bees? A review. Agron. Sustain. 2015, 35, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvoz, S.; Cordeau, S.; Zuccolo, C.; Petit, S. Crop type and within-field location as sources of intraspecific variations in the phenology and the production of floral and fruit resources by weeds. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanusová, H.; Juřenová, K.; Hurajová, E.; Vaveková, M.D.; Winkler, J. Vegetation structure of bio-belts as agro-environmentally-climatic measures to support biodiversity on arable land: A case study. AIMS Agric. Food 2022, 7, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylianakis, J.M.; Didham, R.K.; Wratten, S.D. Improved fitness of aphid parasitoids receiving resource subsidies. Ecology 2004, 85, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, A.; Averill, K.M.; Hoffmann, M.P.; Fuchsberg, J.R.; Losey, J.E. Integrating insect resistance and floral resource management in weed control decision-making. Weed Sci. 2016, 64, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzlik, K.; Gerowitt, B. Verändern pfluglose Bodenbearbeitung und Frühsaaten die Unkrautvegetation im Winterraps? Gesunde Pflanz 2021, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, G.; Norton, L.R.; Reboud, X. Environmental and management factors determining weed species composition and diversity in France. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S.; Gaba, S.; Grison, A.L.; Meiss, H.; Simmoneau, B.; Munier-Jolain, N.; Bretagnolle, V. Landscape scale management affects weed richness but not weed abundance in winter wheat fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Tomaník, M.; Martínez Barroso, P.; Děkanovský, I.; Sitek, W.; Vaverková, M.D. The Importance of Municipal Waste Landfill Vegetation for Biological Relevance: A Case Study. Environments 2025, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alignier, A.; Ricci, B.; Biju-Duval, L.; Petit, S. Identifying the relevant spatial and temporal scales in plant species occurrence models: The case of arable weeds in landscape mosaic of crops. Ecol. Complex. 2013, 15, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.S.; Baines, D.; Coulson, J.C.; Longrigg, G. Age at first breeding, philopatry and breeding site-fidelity in the Lapwing Vanellus vanellus. Ibis 1994, 136, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrubb, M. The Lapwing; T & A D Poyser: London, UK, 2007; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Milsom, T.P.; Langton, S.D.; Parkin, W.K.; Peel, S.; Bishop, J.D.; Hart, J.D.; Moore, N.P. Habitat models of bird species’ distribution: An aid to the management of coastal grazing marshes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 706–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, H.M.; Park, K.J.; O’Brien, M.G.; Gimona, A.; Poggio, L.; Wilson, J.D. Soil pH and organic matter content add explanatory power to Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus distribution models and suggest soil amendment as a conservation measure on upland farmland. Ibis 2015, 157, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Hartel, T.; Báldi, A.; Szymański, P.; Tobółka, M.; Herzon, I.; Oławski, A.; Konvička, M.; Hromada, M.; Jerzak, L.; et al. Conservation of farmland birds faces different challenges in Western and Central-Eastern Europe. Acta Ornithol. 2011, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenička, P.; Šímová, P.; Hrdinová, K.; Šálek, M. Changing rural landscapes along the border of Austria and the Czech Republic between 1952 and 2009: Roles of political, socioeconomic and environmental factors. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 47, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleček, J.; Reif, J.; Weidinger, K. The abundance of a farmland specialist bird, the skylark, in three European regions with contrasting agricultural management. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 212, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanusová, H.; Jirout, M.; Winkler, J. Development of Land Use and Ecological Stability in Selected Traditional Sugar Beet-Growing Cadastral Areas in Olomouc District. Listy Cukrov. A Reparske 2018, 134, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hurajová, E.; Martínez Barroso, P.; Děkanovský, I.; Lumbantobing, Y.R.; Jiroušek, M.; Mugutdinov, A.; Havel, L.; Winkler, J. Biodiversity and Vegetation Succession in Vineyards, Moravia (Czech Republic). Agriculture 2024, 14, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marada, P.; Cukor, J.; Kuběnka, M.; Linda, R.; Vacek, Z.; Vacek, S. New agri-environmental measures have a direct effect on wildlife and economy on conventional agricultural land. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaut, L.; Cheptou, P.O.; Fried, G.; Munoz, F.; Storkey, J.; Vasseur, F.; Violle, C.; Bretagnolle, F. Weeds: Against the Rules? Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, J.; Clough, Y.; Sahlin, U.; Smith, H.G.; Stjernman, M.; Olsson, O.; Sahrbacher, A.; Brady, M.V. Impacts of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy “Greening” reform on agricultural development, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 42, 716–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, K.; Döring, T.; Garske, B.; Stubenrauch, J.; Ekardt, F. The Common Agricultural Policy beyond 2020: A critical review in light of global environmental goals. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaas, E.; Meyer-Wolfarth, F.; Banse, M.; Bengtsson, J.; Bergmann, H.; Faber, J.; Potthoff, M.; Runge, T.; Schrader, S.; Taylor, A. Towards valuation of biodiversity in agricultural soils: A case for earthworms. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Bonn, A.; Bruelheide, H.; Dieker, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feindt, P.H.; Hagedorn, G.; Hansjürgens, B.; Herzon, I.; Lomba, Â.; et al. Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges. People Nat. 2020, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, H.M.; Wilson, J.D.; O’Brien, M.G.; Beaumont, D.; Sheldon, R.; Park, K.J. Fodder crop management benefits Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) outside agri-environment schemes. Agric. Ecosyst. Env. 2018, 265, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Dicks, L.V.; Visconti, P.; Arlettaz, R.; Báldi, A.; Benton, T.G.; Collins, S.; Dieterich, M.; Gregory, R.D.; Hartig, F.; et al. EU agricultural reform fails on biodiversity. Science 2014, 344, 1090–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Municipal Cadastral Area of | Region | Area Size (ha) | GPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Čakov | Southern Bohemia | 2.25 | 48.9859236 N, 14.3099069 E |

| 2 | Čejkovice | Southern Bohemia | 2.74 | 49.0105178 N, 14.4120239 E |

| 3 | Dražkov n. L. (1) | Eastern Bohemia | 3.90 | 50.0948322 N, 15.8388806 E |

| 4 | Dražkov n. L. (2) | Eastern Bohemia | 4.18 | 50.0973789 N, 15.8321642 E |

| 5 | Dubné | Southern Bohemia | 2.15 | 48.9769689 N, 14.3674617 E |

| 6 | Jaronice | Southern Bohemia | 2.01 | 48.9945128 N, 14.3611639 E |

| 7 | Křenovice u Dubného | Southern Bohemia | 9.03 | 48.9869675 N, 14.3736478 E |

| 8 | Nové Město n. C. | Eastern Bohemia | 1.69 | 50.1534492 N, 15.4858564 E |

| 9 | Kratokonohy | Eastern Bohemia | 4.81 | 50.1754392 N, 15.6114636 E |

| 10 | Mžany | Eastern Bohemia | 2.30 | 50.2803731 N, 15.6714786 E |

| 11 | Olešnice | Eastern Bohemia | 2.15 | 50.1432319 N, 15.4583497 E |

| 12 | Plástovice | Southern Bohemia | 6.19 | 49.0572258 N, 14.3007386 E |

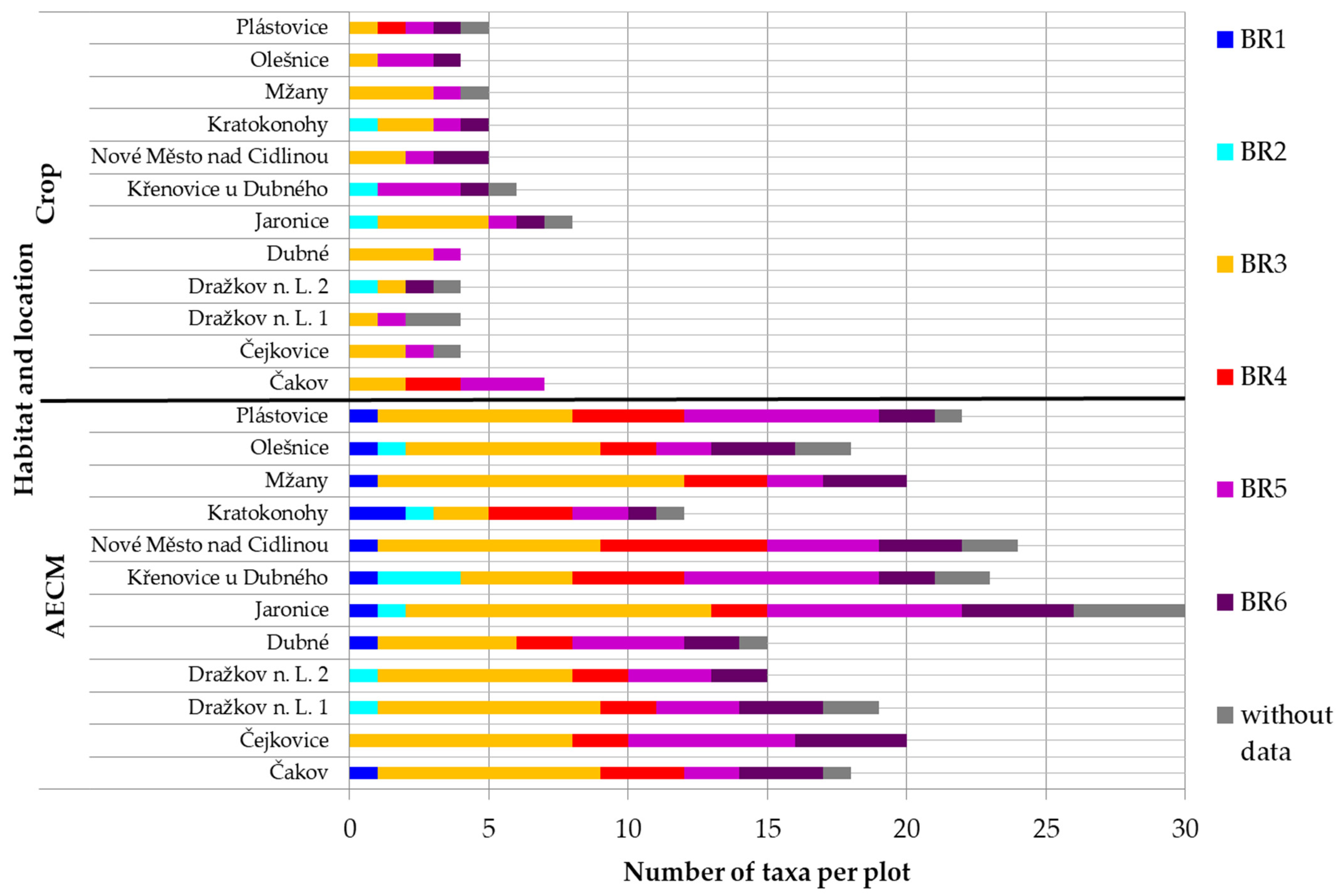

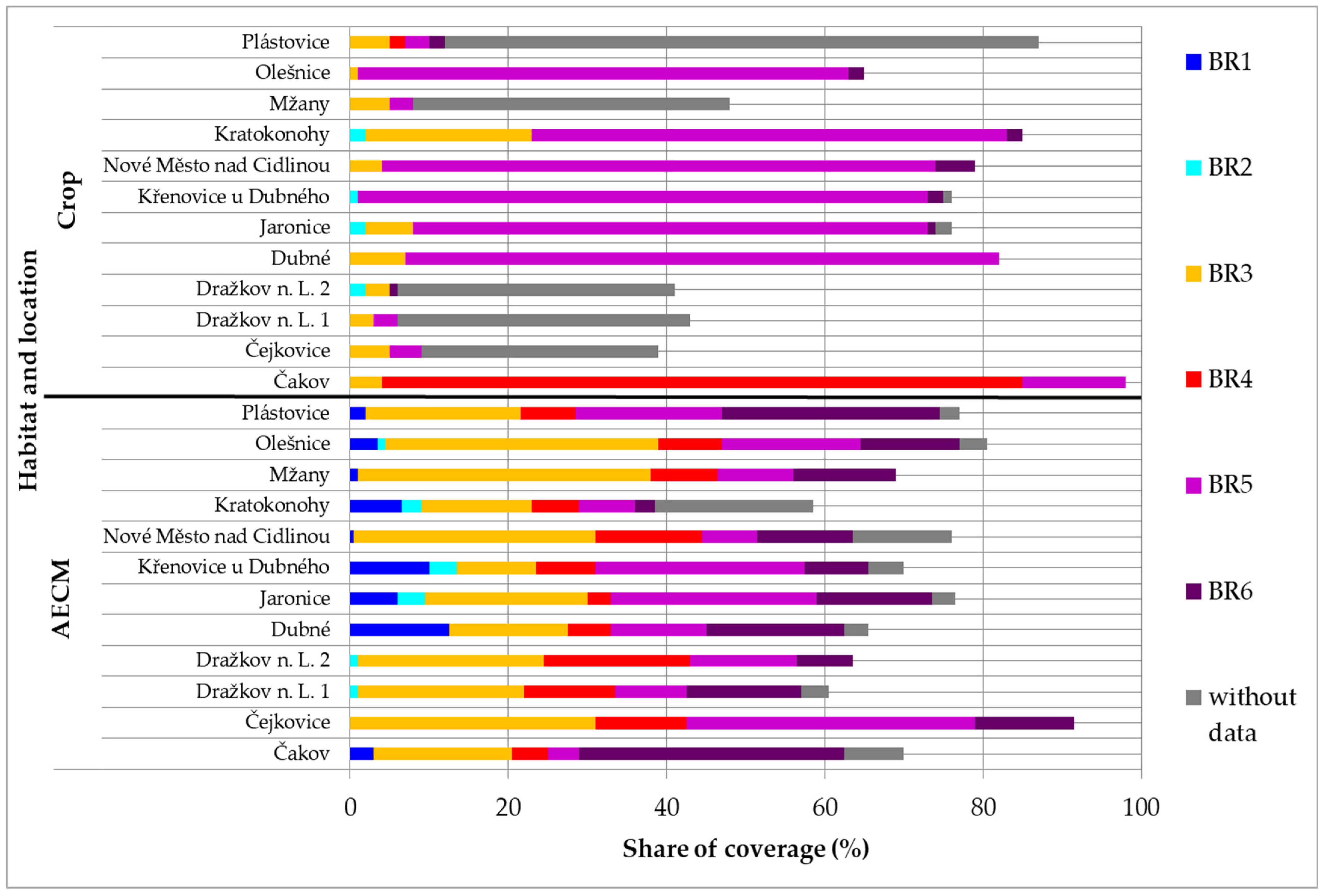

| Designation | Number of Species Depending on the Plants |

|---|---|

| BR1 | <6 |

| BR2 | 6–12 |

| BR3 | 13–24 |

| BR4 | 25–50 |

| BR5 | 51–100 |

| BR6 | 101–200 |

| Site | Species |

|---|---|

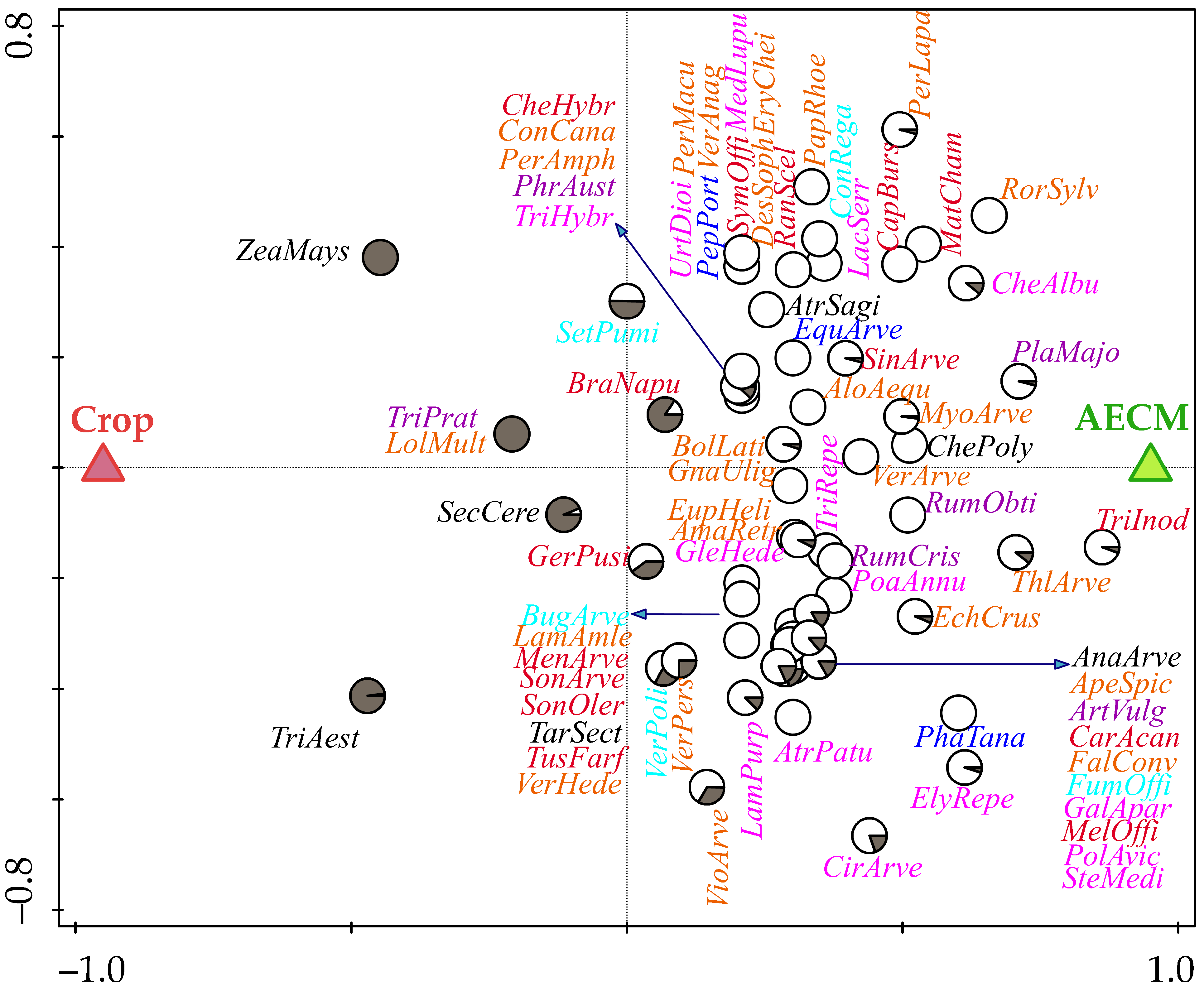

| AECM-preferring species | Dominant occurrence: Cirsium arvense (CirArve), Elymus repens (ElyRepe), Chenopodium album (CheAlbu), Matricaria chamomilla (MatCham), Phacelia tanacetifolia (PhaTana), Tripleurospermum inodorum (TriInod). |

| Subdominant occurrence: Amaranthus retroflexus (AmaRetr), Anagallis arvensis (AnaArve), Apera spica-venti (ApeSpic), Atriplex patula (AtrPatu), Atriplex sagittata (AtrSagi), Bolboschoenus laticarpus (BolLati), Capsella bursa-pastoris (CapBurs), Consolida regalis (ConRega), Echinochloa crus-galli (EchCrus), Equisetum arvense (EquArve), Euphorbia helioscopia (EupHeli), Fallopia convolvulus (FalConv), Fumaria officinalis (FumOffi), Chenopodium polyspermum (ChePoly), Melilotus officinalis (MelOffi), Myosotis arvensis (MyoArve), Persicaria amphibia (PerAmph), Persicaria lapathifolia (PerLapa), Phragmites australis (PhrAust), Plantago major (PlaMajo), Poa annua (PoaAnnu), Polygonum aviculare (PolAvic), Rorippa sylvestris (RorSylv), Rumex crispus (RumCris), Rumex obtusifolius (RumObti), Sinapis arvensis (SinArve), Sonchus arvensis (SonArve), Stellaria media (SteMedi), Thlaspi arvense (ThlArve), Trifolium hybridum (TriHybr), Trifolium repens (TriRepe). | |

| Low occurrence: Alopecurus aequalis (AloAequ), Artemisia vulgaris (ArtVulg), Buglossoides arvensis (BugArve), Carduus acanthoides (CarAcan), Conyza canadensis (ConCana), Descurainia Sophia (DesSoph), Erysimum cheiranthoides (EryChei), Galium aparine (GalApar), Glechoma hederacea (GleHede), Gnaphalium uliginosum (GnaUlig), Chenopodium hybridum (CheHybr), Lactuca serriola (LacSerr), Lamium amplexicaule (LamAmle), Lamium purpureum (LamPurp), Medicago lupulina (MedLupu), Mentha arvensis (MenArve), Papaver rhoeas (PapRhoe), Peplis portula (PepPort), Persicaria maculosa (PerMacu), Ranunculus sceleratus (RanScel), Sonchus oleraceus (SonOler), Symphytum officinale (SymOffi), Taraxacum sect. Taraxacum (TarSect), Tussilago farfara (TusFarf), Urtica dioica (UrtDioi), Veronica anagallis-aquatica (VerAnag), Veronica arvensis (VerArve), Veronica hederifolia (VerHede). | |

| Species with no AECM/Crop preference | Brassica napus (BraNapu), Geranium pusillum (GerPusi), Setaria pumila (SetPumi), Veronica persica (VerPers), Veronica polita (VerPoli), Viola arvensis (VioArve). |

| Species preferring arable land with crop (Crop) | Lolium multiflorum (LolMult), Secale cereale (SecCere), Triticum aestivum (TriAest), Trifolium pratense (TriPrat), Zea mays (ZeaMays). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Winkler, J.; Zámečník, V.; Mugutdinov, A.; Martínez Barroso, P.; Vaverková, M.D. The Potential of Vegetation for Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Protective Measures for the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus L.) on Arable Land. Ecologies 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies7010005

Winkler J, Zámečník V, Mugutdinov A, Martínez Barroso P, Vaverková MD. The Potential of Vegetation for Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Protective Measures for the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus L.) on Arable Land. Ecologies. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies7010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinkler, Jan, Václav Zámečník, Amir Mugutdinov, Petra Martínez Barroso, and Magdalena Daria Vaverková. 2026. "The Potential of Vegetation for Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Protective Measures for the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus L.) on Arable Land" Ecologies 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies7010005

APA StyleWinkler, J., Zámečník, V., Mugutdinov, A., Martínez Barroso, P., & Vaverková, M. D. (2026). The Potential of Vegetation for Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Protective Measures for the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus L.) on Arable Land. Ecologies, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies7010005