Abstract

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, with breast and colon cancers being among the most common neoplasms in men and women, respectively. Despite significant advancements in treatment, there is a pressing need to enhance specificity and reduce systemic side effects. Importantly, a distinctive feature of cancer cells is their acidic extracellular environment, which profoundly influences cancer progression. In this study, we evaluated the anticancer activity of a pH-sensitive nanocomposite based on silver nanoparticles and pegylated carboxymethyl chitosan (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) in breast cancer (MCF-7) and colon cancer (HCT 116) cell lines. To achieve this, we synthesized and characterized the nanocomposite using UV-Vis spectroscopy, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), and Scanning Electron Microscopy (STEM-in-SEM). Furthermore, we assessed cytotoxic effects, apoptosis, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation using MTT, DAPI, and H2DCFDA assays. Additionally, we analyzed the expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT3a) and histone acetyltransferases (MYST4, GCN5) at the mRNA level using RT-qPCR, along with the acetylation and methylation of H3K9ac and H3K9me2 through Western blot analysis. The synthesized nanocomposite demonstrated an average hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 175.4 nm. In contrast, STEM-in-SEM analyses revealed well-dispersed nanoparticles with an average core size of about 14 nm. Additionally, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy verified the successful surface functionalization of the nanocomposite with polyethylene glycol (PEG), indicating effective conjugation and structural stability. The nanocomposite exhibited a pH and concentration dependent cytotoxic effect, with enhanced activity observed at an acidic pH 6.5 and at concentrations of 150 µg/ml, 75 µg/ml, and 37.5 µg/ml for both cell lines. Notably, the nanocomposite preferentially induced apoptosis accompanied by ROS generation. Moreover, expression analysis revealed a decrease in H3K9me2 and H3K9ac in both cell lines, with a more pronounced effect in MCF-7 at an acidic pH. Furthermore, the expression of DNMT3a at the mRNA level significantly decreased, particularly at acidic pH. Regarding histone acetyltransferases, GCN5 expression decreased in the HCT 116 line, while MYST4 expression increased in the MCF-7 line. These findings demonstrate that the AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite has therapeutic potential as a pH-responsive nanocomposite, capable of inducing significant cytotoxic effects and altering epigenetic markers, particularly under the acidic conditions of the tumor microenvironment. Overall, this study highlights the advantages of utilizing pH-sensitive materials in cancer therapy, paving the way for more effective and targeted treatment strategies.

1. Introduction

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, posing a significant challenge to public health despite advancements in conventional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies [1]. Nevertheless, many neoplasms continue to exhibit high rates of treatment resistance and recurrence, underscoring the urgent need for the development of more effective therapeutic strategies [2].

In particular, the prevalence of colorectal cancer has risen at an alarming rate in recent years. In 2020, approximately 1.93 million new cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed, resulting in a total of 0.94 million associated deaths, which accounts for about 10% of the global cancer incidence [3,4]. On the other hand, breast cancer remains the most common neoplasm among women globally, characterized by its heterogeneity in terms of subtypes and biological behavior [5]. The onset of breast cancer is influenced by multiple risk factors, including genetic and hereditary predisposition [6].

A key feature shared by many types of cancer cells, including those from breast and colorectal cancers, is the alteration of the pH gradient. The extracellular pH of tumor cells is more acidic compared to normal cells, creating a microenvironment that promotes tumor proliferation and resistance to conventional therapies [7]. These alterations in pH levels, both intracellular and extracellular, play a crucial role in tumor progression [8].

In this context, nanotechnology has emerged as a powerful tool for enhancing anticancer therapies, owing to its ability to provide more precise drug delivery and reduce systemic side effects. This approach has garnered increasing interest over the past decade due to its clear advantages in targeting tumor tissue [9]. Specifically, treatments based on nanoscale drug delivery allow for more efficient accumulation in malignant tissues, maximizing therapeutic effects while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues [10].

The development of pH-sensitive nanocomposites has become an important area of research due to their potential applications in targeted drug delivery. Among various polymeric systems, carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC), a water-soluble derivative of chitosan, has gained attention for its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and pH-responsive properties, making it ideal for biomedical applications [11,12]. Additionally, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have shown great potential as therapeutic agents in oncology due to their anti-tumor effects. These particles can efficiently interact with cancer cells, leveraging the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which facilitates their entry and accumulation in tumor cells [13]. The EPR effect increases the concentration of nanoparticles in malignant tissue, leading to cell death or inhibition of tumor growth [14,15]. Functionalizing these nanocomposites through pegylation adding polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to their surface offers several benefits, including improved pharmacokinetic pro-files by reducing immunogenicity, preventing degradation, and decreasing plasma clearance [16].

In this study, tumor specificity is addressed from a microenvironmental perspective by exploiting the acidic conditions characteristic of solid tumors. The AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite was therefore designed as a pH-responsive system, aiming to achieve preferential anticancer activity under acidic conditions rather than cancer-type-specific targeting.

Accordingly, our study was designed as a proof-of-concept investigation to establish the anticancer potential and initial epigenetic impact of the proposed AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite, providing a foundation for future investigations aimed at mechanistic validation in breast (MCF-7) and colorectal (HCT-116) cancer cell lines. We determined the cytotoxic effect of the nanocomposite on these cells using the MTT assay and we determined the type of cell death through fluorescence assays such as DAPI and H2DCFDA to measure reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Finally, we measured the expression of DNA methyltransferases and histone acetyltransferases at both mRNA and protein levels using RT-PCR and Western blotting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of the Pegylated Nanocomposite (AgNPs-CMC-PEG)

The synthesis of the pegylated nanocomposite (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) was carried out following a methodology previously reported by our research group and other authors at Nanomaterials Preparation, Characterization, and Identification Laboratory (LAPCINANO), with some modifications [17,18]. First, the AgNPs-CMC nanocomposite was synthesized by reducing a precursor salt, silver nitrate (AgNO3 1 mM) (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), using 0.15% carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) 400 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) as both the reducing and stabilizing agent. Subsequently, PEGylation of the AgNPs-CMC nanocomposite was performed by adding PEG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 1:1 ratio to the nanocomposite, followed by magnetic stirring at 250 rpm and 40 °C for approximately two hours [19,20].

2.2. Characterization of the Nanocomposite

2.2.1. UV–Visible Spectrophotometry

The synthesis of the nanocomposite (AgNPs–CMC), was monitored by UV–visible spectrophotometry (Evolution 220, model 840-210600, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A spectral scan was performed over the wavelength range of 300–800 nm, with a resolution of 1 nm, in order to detect the characteristic surface plasmon resonance peak of silver nanoparticles. Likewise, the spectrum of the pegylated nanocomposite (AgNPs–CMC–PEG) was analyzed to evaluate possible shifts or variations in the plasmonic band associated with the incorporation of polyethylene glycol (PEG).

2.2.2. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

The hydrodynamic diameter and particle size distribution of the nanocomposites were determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using a particle size analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments Limited, Malvern, UK). Measurements were performed at 25 °C with a scattering angle of 90°. Each measurement was conducted in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the average hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI).

2.2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites were characterized by Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) using a Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spectra were recorded in the range of 500–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1, and an average of 32 scans per sample to minimize noise and enhance the signal-to-noise ratio.

2.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (STEM-in-SEM)

Morphological and size analysis of the nanocomposite was carried out using a scanning transmission electron microscopy within a SEM (STEM-in-SEM) (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). For sample preparation, a drop of the diluted nanocomposite suspension was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to dry by evaporation at room temperature. Micrographs were acquired at different magnifications to evaluate surface morphology, particle distribution, and the average particle diameter.

2.3. Cell Culture

The human breast cancer cell line (MCF 7) and a colon cancer cell line (HCT 116) were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cultures were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Both cell lines were purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC).

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

The MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was performed. For this, 10,000 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. After this time, the medium containing the treatments (Control, SDS as positive control, 150 µg/mL, 75 µg/mL and 37.5 µg/mL Nanocomposite, CMC, 150 µg/mL, 75 µg/mL, and 37.5 µg/mL PEGylated Nanocomposite) was replaced with media at pH 6.5 and 7.4. The cells were incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h. After the first 24 h, the culture medium was removed, and 1:10 of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added and incubated for 1 h. The solution was then removed, and 100 μL of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) was applied to resuspend the solution and dissolve the formazan crystals. The plate was then transferred to a microplate reader (Biotek 800ts, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) for absorbance readings (570 nm). After 48 and 72 h, the same MTT treatment protocol was applied, and the plates were read. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Apoptosis Assay

For the in vitro analysis of cellular apoptosis, DAPI was used (Sigma-Aldrich). First, 80 × 105 cells were seeded per well in a 12-well plate and incubated for 24 h. After this time, the treatments were applied, and after 48 h, control (untreated) and treated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% triton. Then it was incubated with DAPI (10 μg/mL) for 15 min. Afterward, they were observed using fluorescence microscopy with a blue filter. Apoptotic nuclear changes were quantified as the percentage of cells exhibiting nuclear condensation and/or fragmentation relative to the total number of analyzed cells, with 100 cells counted per condition.

2.6. ROS Generation

First, 1 × 105 cells per well were cultured in a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 h, after which the treatments were applied. After 48 h, 10 μM of H2DCFDA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was added along with DMEM medium, and the cells were incubated for 1 h, followed by 3 washes. The cells were then observed under a fluorescence inverted microscope. The percentage of ROS production was calculated as the proportion of ROS-positive cells relative to the total number of analyzed cells, with 100 cells counted per condition.

2.7. RT-qPCR

To measure the expression levels of the target genes, quantitative RT-PCR was per-formed using the BioRad kit and the BioRad CFX960 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) thermocycler. First, the RNA was converted into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA reverse Transcription kit (Applied biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction mixture consisted of 2 µL of cDNA, 10 µL of master mix, 2 µL of Forward and Reverse Primers specific for each gene including Myst4 (Forward 5′ CAG CAA CAA AGG GCA GCA AGC G 3′ Reverse 5′ TCC CAG CCC ATG TGA AGC AAC AG 3′), GCN5 (Forward 5′ CTT CAG TCA GTG CAG CGG TTG 3′ Reverse 5′ TCC TCT TCT CGC CTG GCA TAG 3′) and DNMT3a (Forward 5′ CCTGCAATGACCTCTCCATT 3′ Reverse 5′ CAGGAGGCGGTAGAACTCAA 3′), and 6 µL of nuclease-free water. The cycling protocol was as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, hybridization at the appropriate temperature for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Data analysis was conducted using the Pfaffl method, with GAPDH (Forward 5′ GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC 3′ Reverse 5′ GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC 3′) serving as the reference gene.

2.8. Western Blot

For protein analysis, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein quantification was performed using the Bradford method (Sigma-Aldrich). A mixture of 20 µL of protein sample and 200 µL of Bradford reagent was prepared, and the absorbance was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). A calibration curve was generated using serial dilutions of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in a range of 1 mg/mL to 15 mg/mL.

For electrophoresis, 30 µg of sample was used in a 15% acrylamide gel. Samples were prepared with Laemmli loading buffer (1% SDS, 5% glycerol, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% bromophenol blue, and 0.125 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) in a 1:1 ratio. The sample and loading buffer mixture was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min before loading onto the gel, along with a molecular weight marker (Sigma-Aldrich). Electrophoresis was conducted at 120 V in electrophoresis buffer (0.1% SDS, 1.5% glycine, 0.125 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8).

Once electrophoresis was completed, protein transfer was performed using polyvi-nylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-PSQ, Merck Millipore) and a transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol). The transfer was carried out in a Mini Trans-Blot chamber (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 90 min at 160 V. Membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C with a 5% skim milk solution (HIMEDIA, Thane, India) in TBST. The following day, they were agitated for 1 h and washed 5 times for 7 min with 1% TBST. Subsequently, the primary antibody was incubated for 90 min with agitation. The antibodies used were Anti-Acetyl Histone H3 (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:2000 and Anti-Dimethyl Histone H3 (Merck) at 1:2000. After the first incubation, 5 washes of 7 min with 1% TBST were performed. The secondary antibody, anti-rabbit (Sigma), was incubated for 1 h, followed by 5 washes of 7 min. Finally, protein detection was performed using the ECL chemiluminescence system (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured using a photodocumentation system (Vilver Fusion Solo X, Vilber Lourmat, Collégien, France).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 10 software. All data on graphs are presented as the mean ± standard error. Multiple group comparisons of the means were performed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05 was considered significant, and **** p < 0.0001 was considered highly significant, ns = not significant.

3. Results

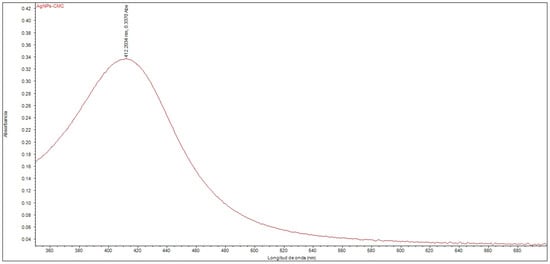

3.1. Characterization of AgNPs-CMC-PEG

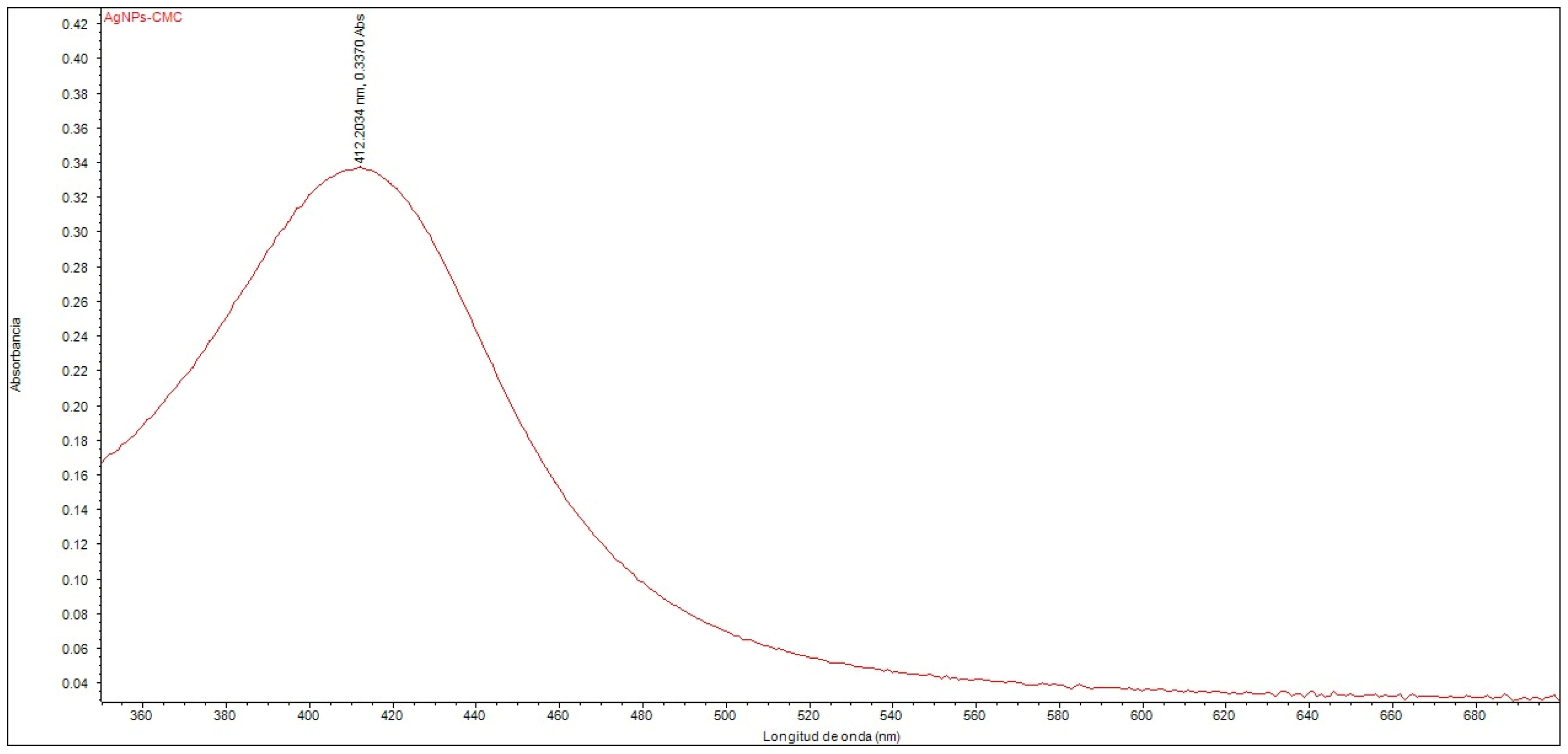

The UV–Vis spectroscopic analysis confirmed the formation of silver nanoparticles within the nanostructured system. An absorption peak was observed at 412.20 nm (Figure 1), corresponding to the surface plasmon resonance band, which is characteristic of silver nanoparticles dispersed in a colloidal phase. The position of this peak falls within the range typically reported for AgNPs with homogeneous size distribution and good colloidal stability, supporting the successful synthesis of the nanocomposite. Furthermore, the effect of polyethylene glycol (PEG) functionalization on the optical properties of the nanocomposite was evaluated, revealing no significant shifts or changes in the intensity of the absorption peak compared to the non-pegylated system.

Figure 1.

UV–Vis spectrum of the nanocomposite composed of silver nanoparticles with CMC (AgNPs-CMC).

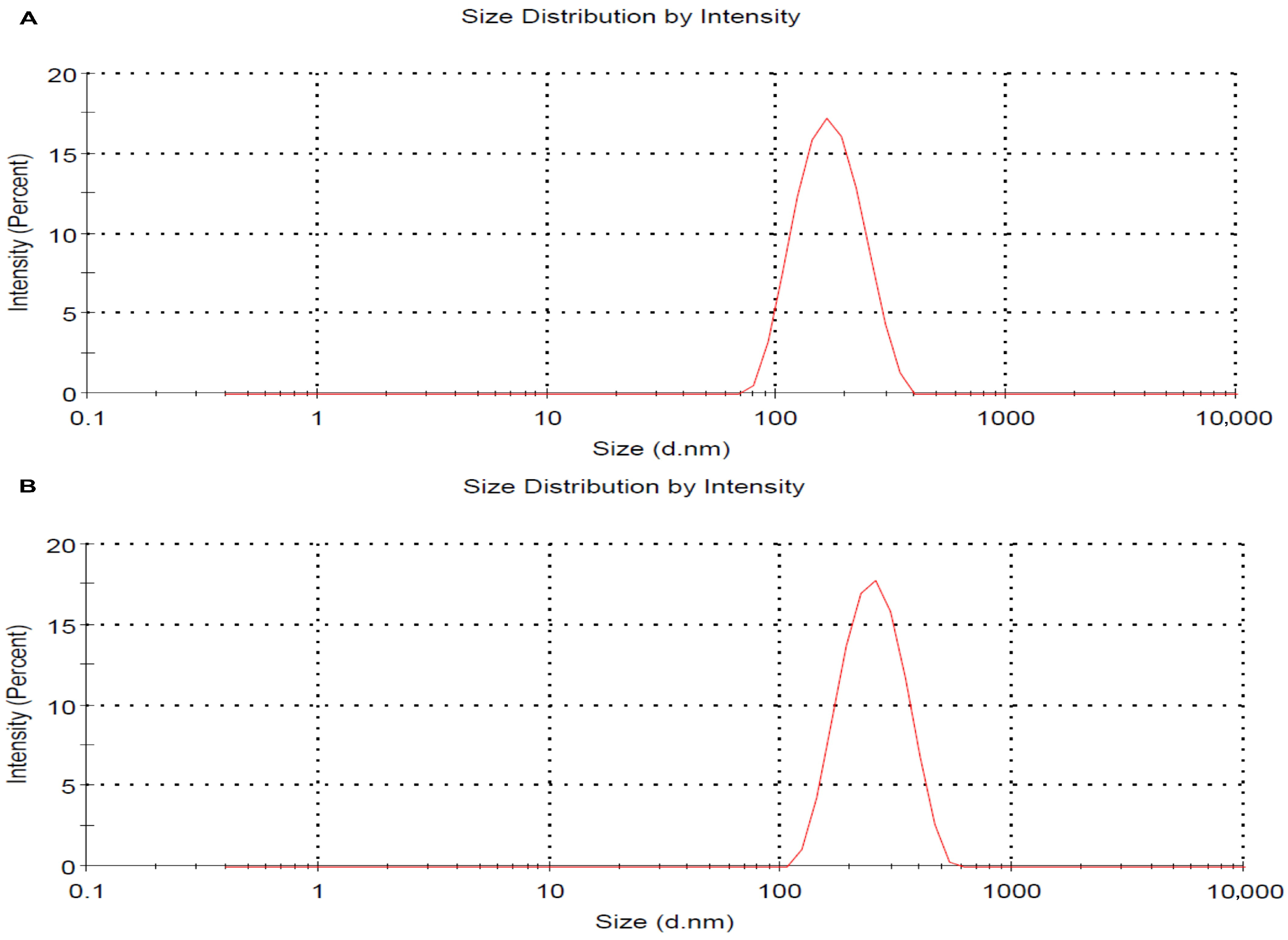

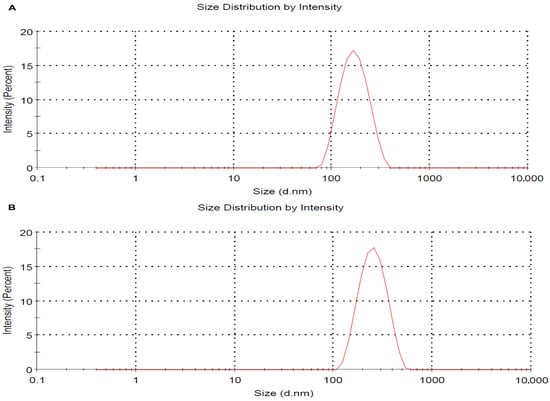

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis was used to determine the hydrodynamic size and polydispersity index (PDI) of the nanocomposites in both their non-pegylated (AgNPs-CMC) and pegylated (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) forms. The resulting spectra revealed a monodisperse peak, indicating a homogeneous distribution of the particles in suspension. The AgNPs-CMC exhibited an average hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 175.4 nm and a PDI of 0.130 (Figure 2A). The AgNPs-CMC-PEG exhibited an average hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 258.4 nm and a PDI of 0.100 (Figure 2B), confirming adequate colloidal stability and uniform nanoparticle dispersion.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of AgNPs-CMC (A) and the AgNPs-CMC-PEG (B) determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS), showing a homogeneous and stable population.

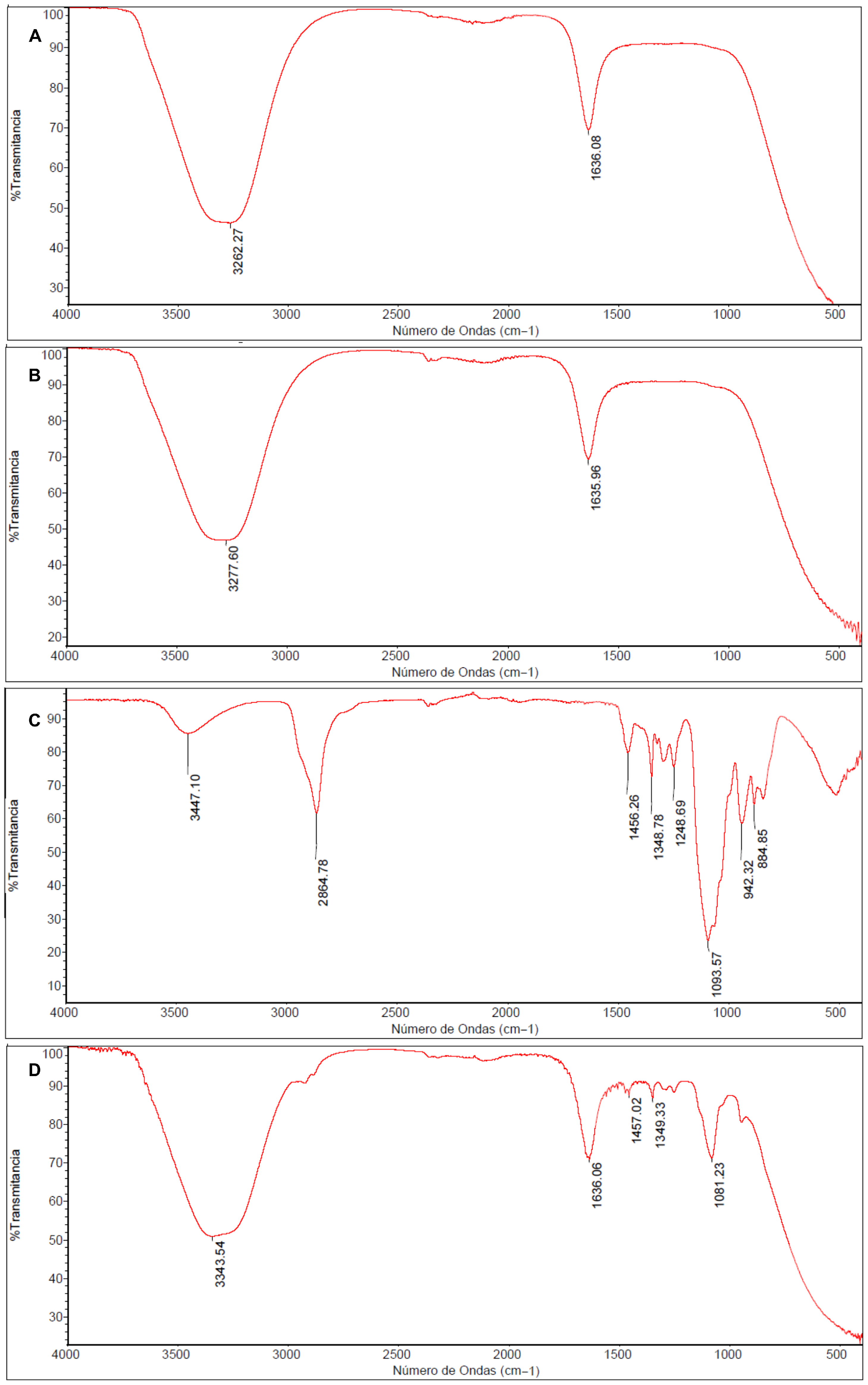

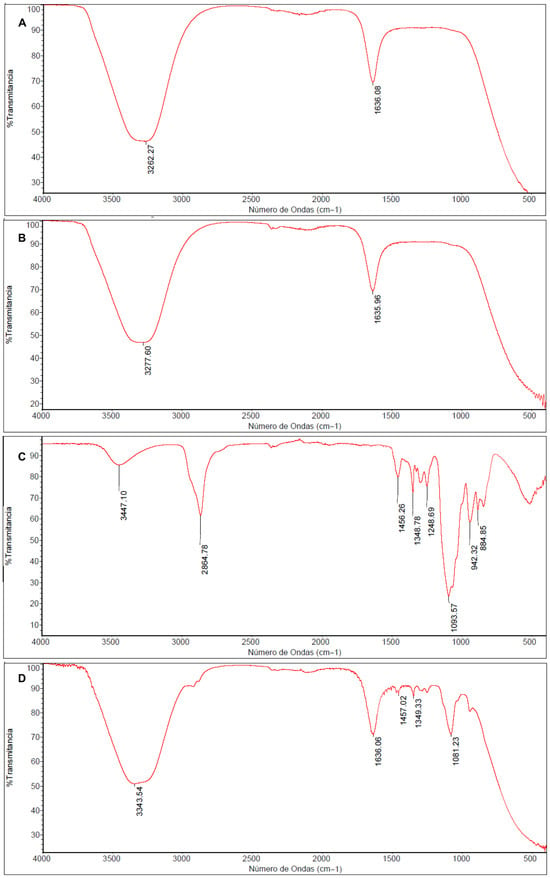

In the FT-IR spectrum of CMC (Figure 3A), a well-defined absorption band at 3262.27 cm−1 is observed, corresponding to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups (-OH), along with an intense band at 1636.08 cm−1 attributed to the asymmetric stretching of the carbonyl group (C=O).

Figure 3.

FT-IR Spectra of Carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) (A), non-pegylated nanocomposite (AgNPs-CMC) (B), Polyethylene glycol (PEG) (C), and pegylated nanocomposite (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) (D).

The AgNPs-CMC nanocomposite (Figure 3B) showed a slight shift in this band toward upper wavenumber to 3277.60, indicating coordinative interactions between silver and the functional groups of CMC, mainly hydroxyl, and amino groups. This minor shift is consistent with Ag-O and Ag-N interactions reported for chitosan-based silver nanocomposites and provide indirect evidence of AgNP stabilization within the polymeric matrix.

The spectrum corresponding to PEG (Figure 3C), the band at 942.32 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of the CH2 group, while the signal at 1093.57 cm−1 corresponds to the rocking vibration of CH2. The band at 1093.57 cm−1 is associated with the C-O-C stretching vibration, characteristic of the ethoxylated backbone of PEG. Additionally, bands at 1251.27 cm−1 and 1348.78 cm−1 are attributed to CH2 oscillations and scissoring motions, respectively, while the band at 1456.26 cm−1 corresponds to the CH2 bending mode. A broad peak at 3447.10 cm−1 is related to -OH stretching, and the signal at 2864.78 cm−1 corresponds to the aliphatic C-H stretching typical of alkanes.

Finally, the spectrum of the pegylated nanocomposite AgNPs-CMC-PEG (Figure 3D), the emergence and increased intensity of multiple bands between 1400 and 900 cm−1, compared with the spectrum of pure PEG (Figure 3C), is evident. This increase in absorption within that region confirms the pegylation event, demonstrating the effective incorporation of PEG into the nanocomposite network.

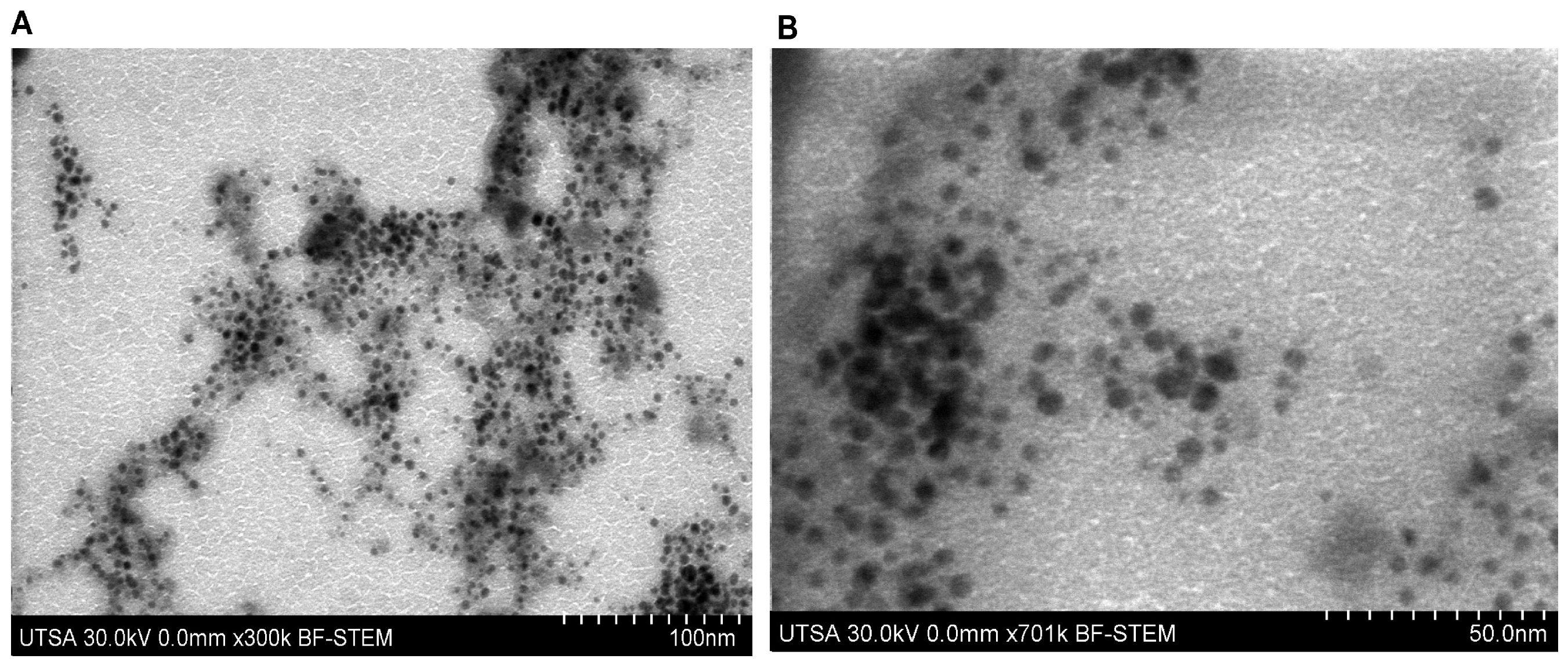

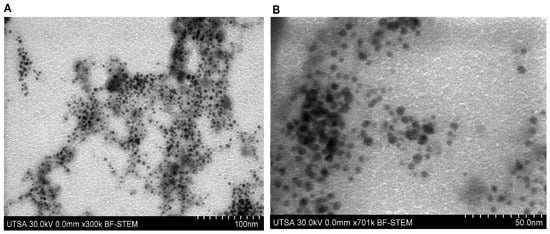

Morphological analysis performed by scanning electron microscopy in STEM mode (STEM-in-SEM) allowed the structural characterization of the nanostructured system (Figure 4A,B). The micrographs showed that the silver nanoparticles exhibit a predominantly spherical morphology with smooth surfaces, uniformly distributed within the carboxymethyl chitosan polymeric matrix. Measurements indicated a homogeneous size distribution, with an average diameter of approximately 14 nm for the silver nanoparticles.

Figure 4.

STEM-in-SEM micrograph of the nanocomposite (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) at ×300 k (A) and ×701 k (B).

3.2. Cytotoxicity Results

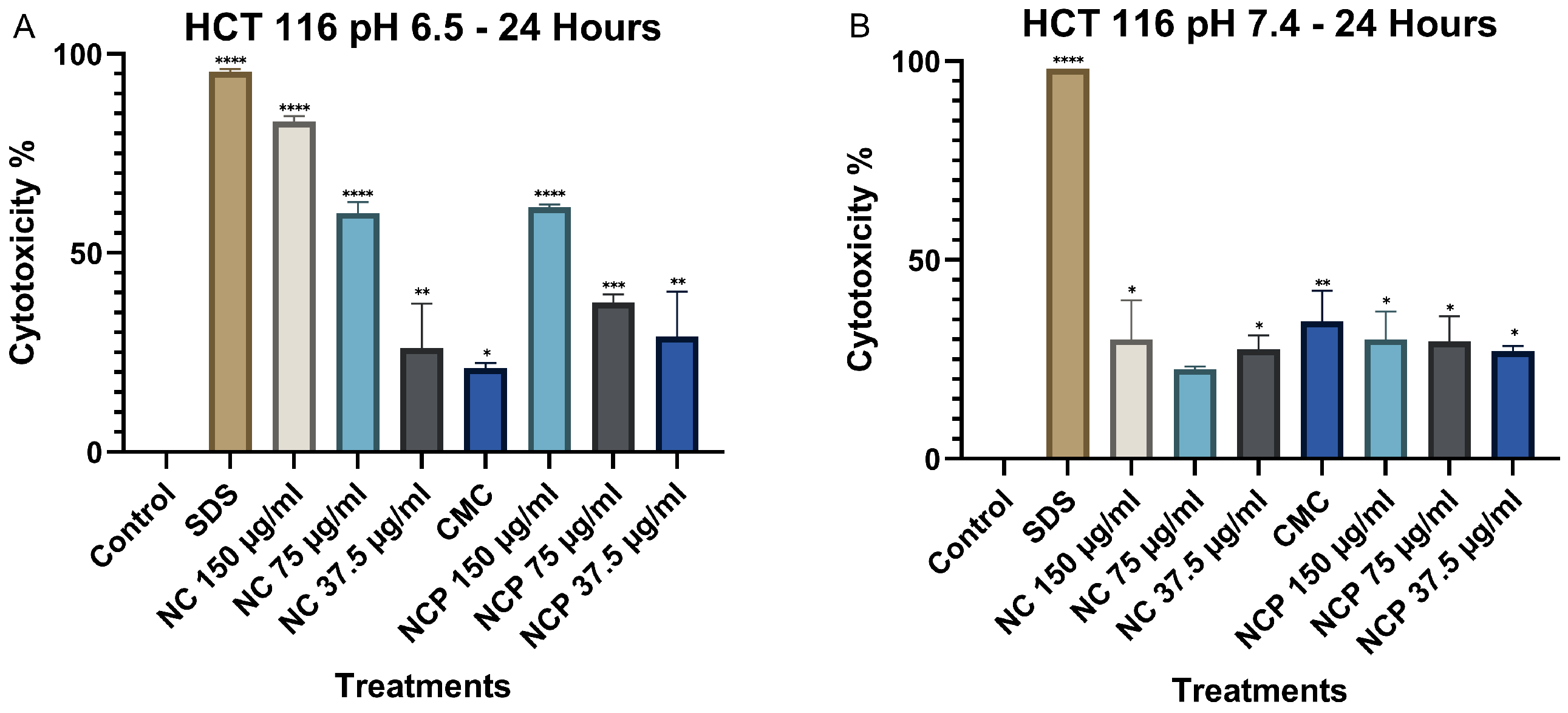

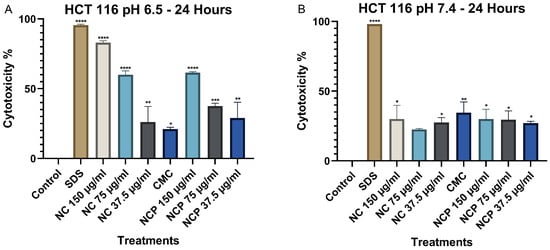

The results obtained for the HCT 116 cell line at 24 h indicate that the cytotoxicity of the nanocomposite significantly increases at pH 6.5, demonstrating a direct correlation with the treatment concentration (Figure 5A). Notably, the nanocomposite at a 150 µg/mL concentration exhibited the highest level of cytotoxicity. In contrast, at pH 7.4, the cytotoxicity was considerably lower, not exceeding 25% in any of the treatments (Figure 5B). Numerical cytotoxicity values are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic effect on the HCT 116 cell line at 24 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

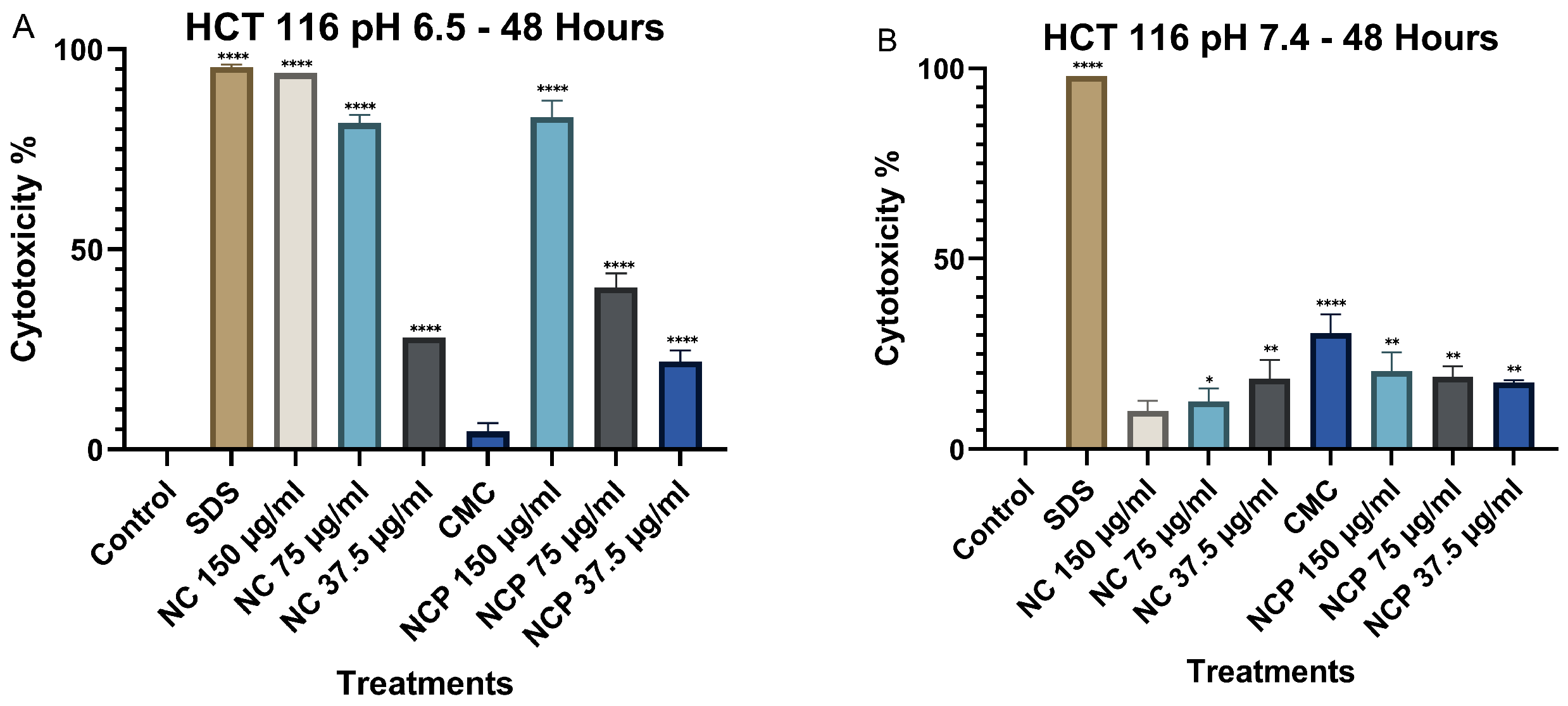

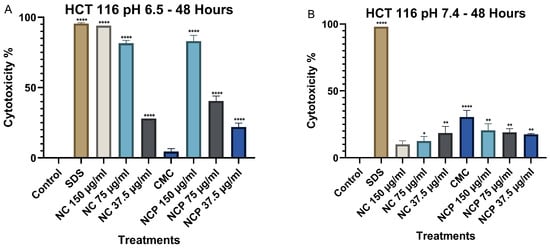

At 48 h, cytotoxicity at pH 6.5 increased significantly, particularly for both pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites at concentrations of 150 µg/mL and 75 µg/mL (Figure 6A), demonstrating a time-dependent cytotoxic effect. In contrast, at pH 7.4, cytotoxicity did not increase, showing values below 35% (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Cytotoxic effect on the HCT 116 cell line at 48 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001).

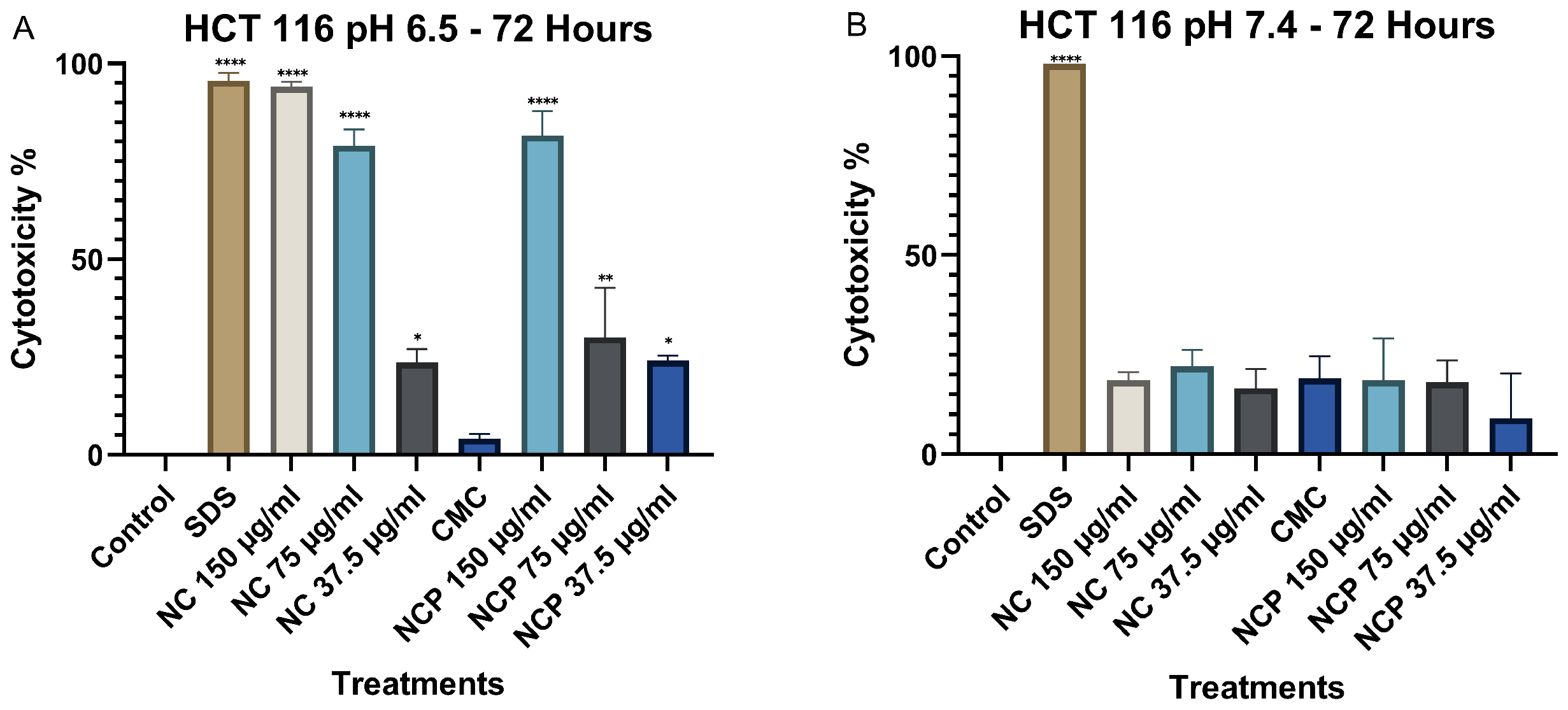

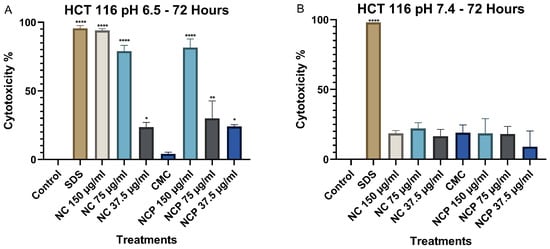

Finally, after 72 h of exposure, cytotoxicity at pH 6.5 remained high, similar to the levels observed at 48 h. The concentrations of 150 µg/mL and 75 µg/mL of both the nanocomposite and the pegylated nanocomposite exhibited the highest cytotoxicity, with values of 94% and 91%, respectively (Figure 7A). At pH 7.4, no significant increase in cytotoxicity was observed at any of the nanocomposite concentrations (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic effect on the HCT 116 cell line at 72 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001).

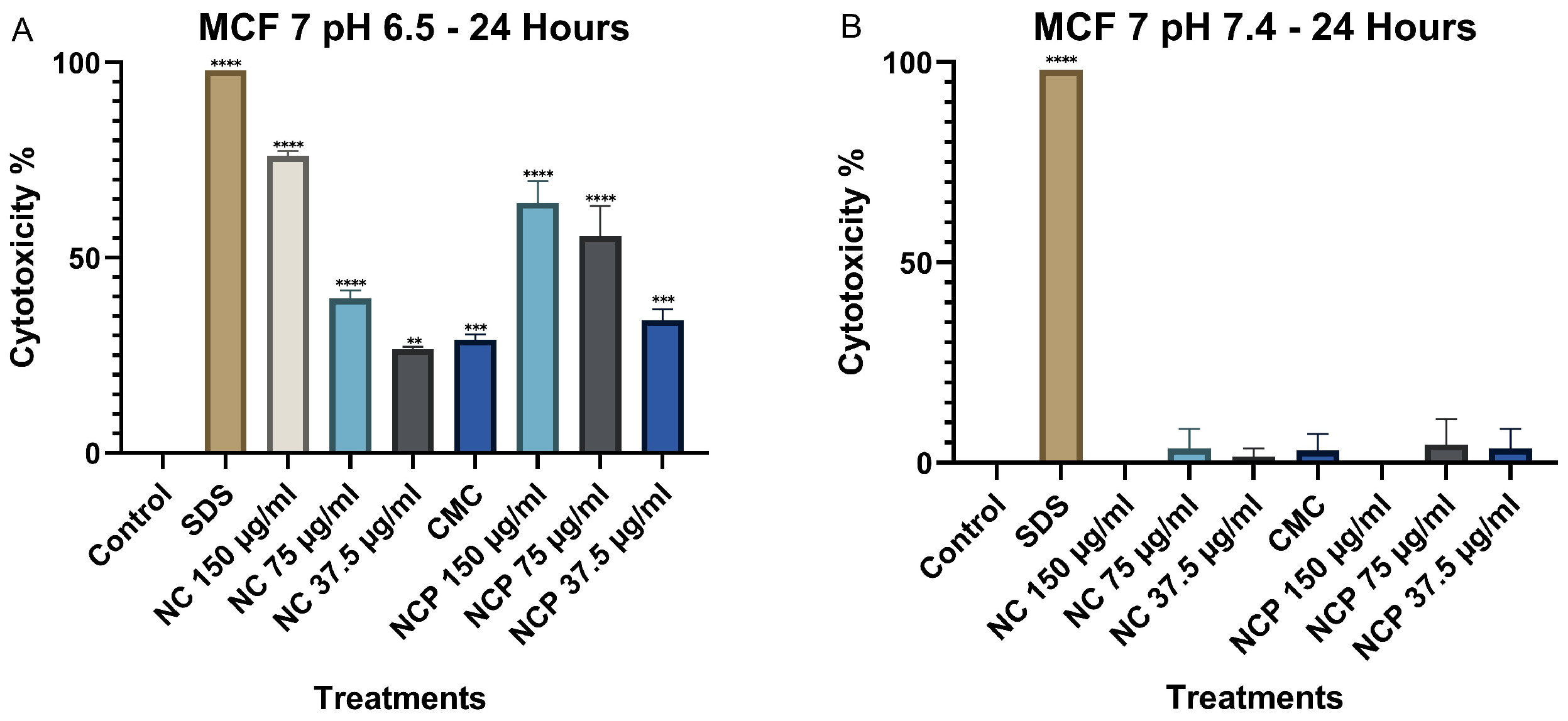

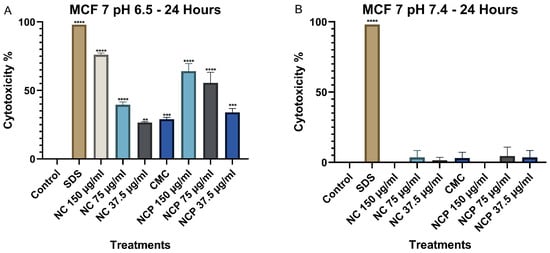

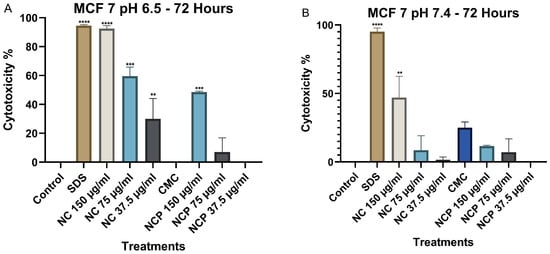

The results of the MTT assay in the MCF 7 cell line at 24 h show that the cytotoxicity of the nanocomposite increases significantly at pH 6.5, demonstrating a direct relationship with the treatment concentration (Figure 8A). The treatments with 150 µg/mL of the nanocomposite and the pegylated nanocomposite exhibited the highest cytotoxicity. In contrast, at pH 7.4, cytotoxicity remained below 10% (Figure 8B). Numerical cytotoxicity values are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 8.

Cytotoxic effect on the MCF 7 cell line at 24 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

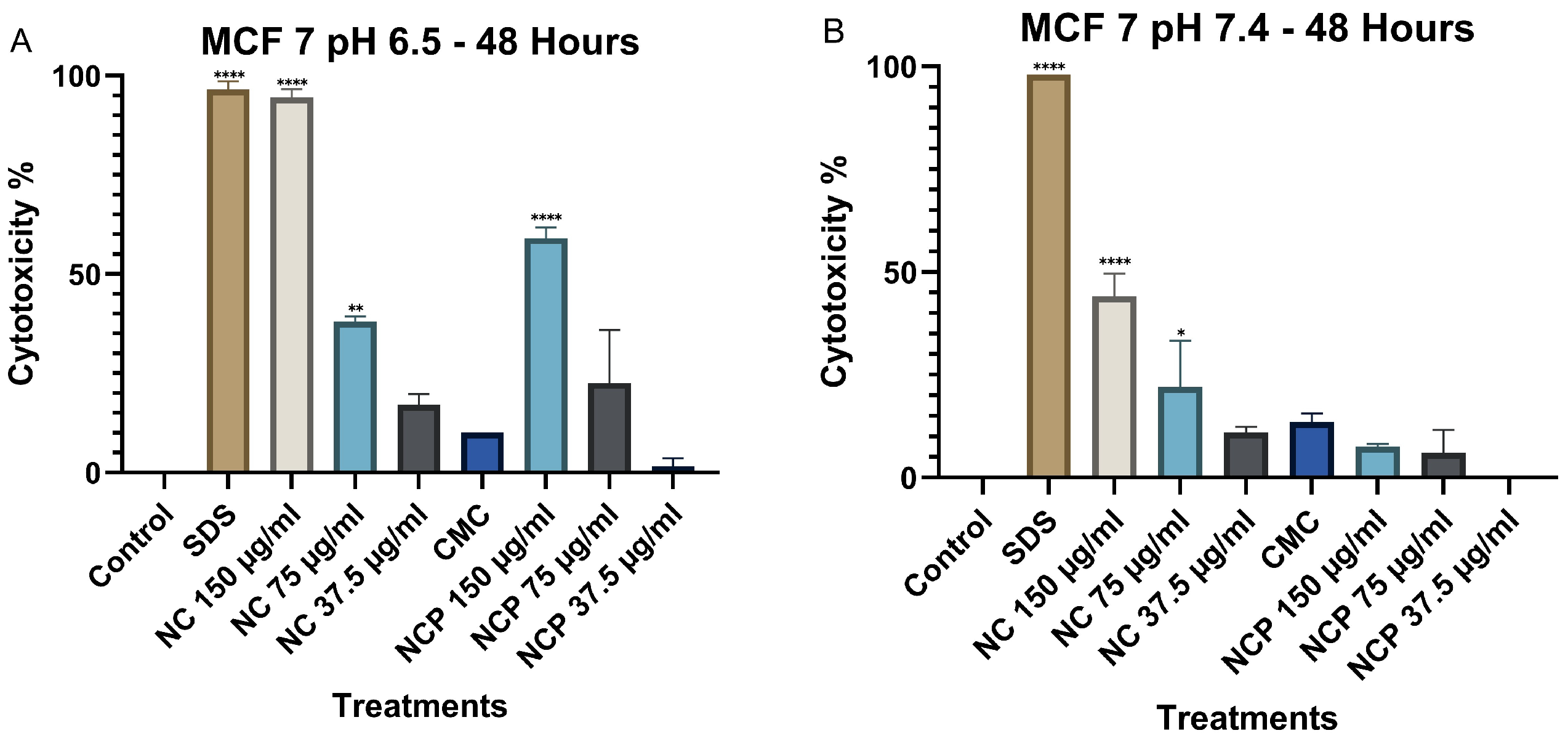

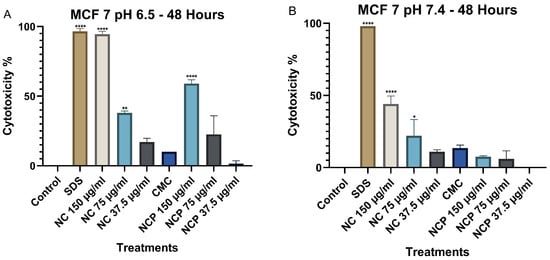

At 48 h, a significant increase in cytotoxicity was recorded at pH 6.5, especially at the 150 µg/mL concentrations of non-pegylated and pegylated nanocomposite (Figure 9A). In contrast, at pH 7.4, no significant increase in cytotoxicity was observed, where the non-pegylated nanocomposite was the only treatment that reached 44% (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic effect on the MCF 7 cell line at 48 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001).

After 72 h, the cytotoxicity at pH 6.5 remained high; the 150 µg/mL concentration of the nanocomposite showed cytotoxicity values of 92%, followed by the 75 µg/mL concentration of the nanocomposite with a cytotoxicity of 58% (Figure 10A). In contrast, at pH 7.4, the non-pegylated nanocomposite with a 150 µg/mL concentration was the only one with 47% cytotoxicity (Figure 10B).

Figure 10.

Cytotoxic effect on the MCF 7 cell line at 72 h. pH 6.5 conditions (A) and pH 7.4 conditions (B) (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

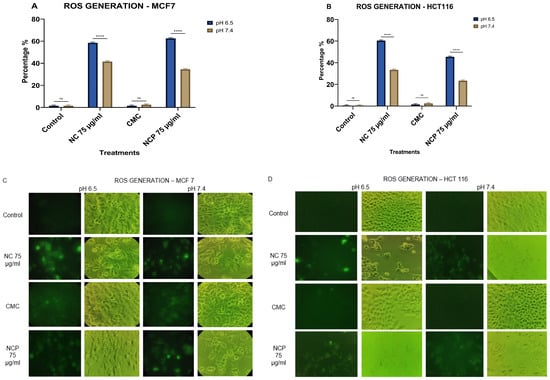

3.3. ROS Results

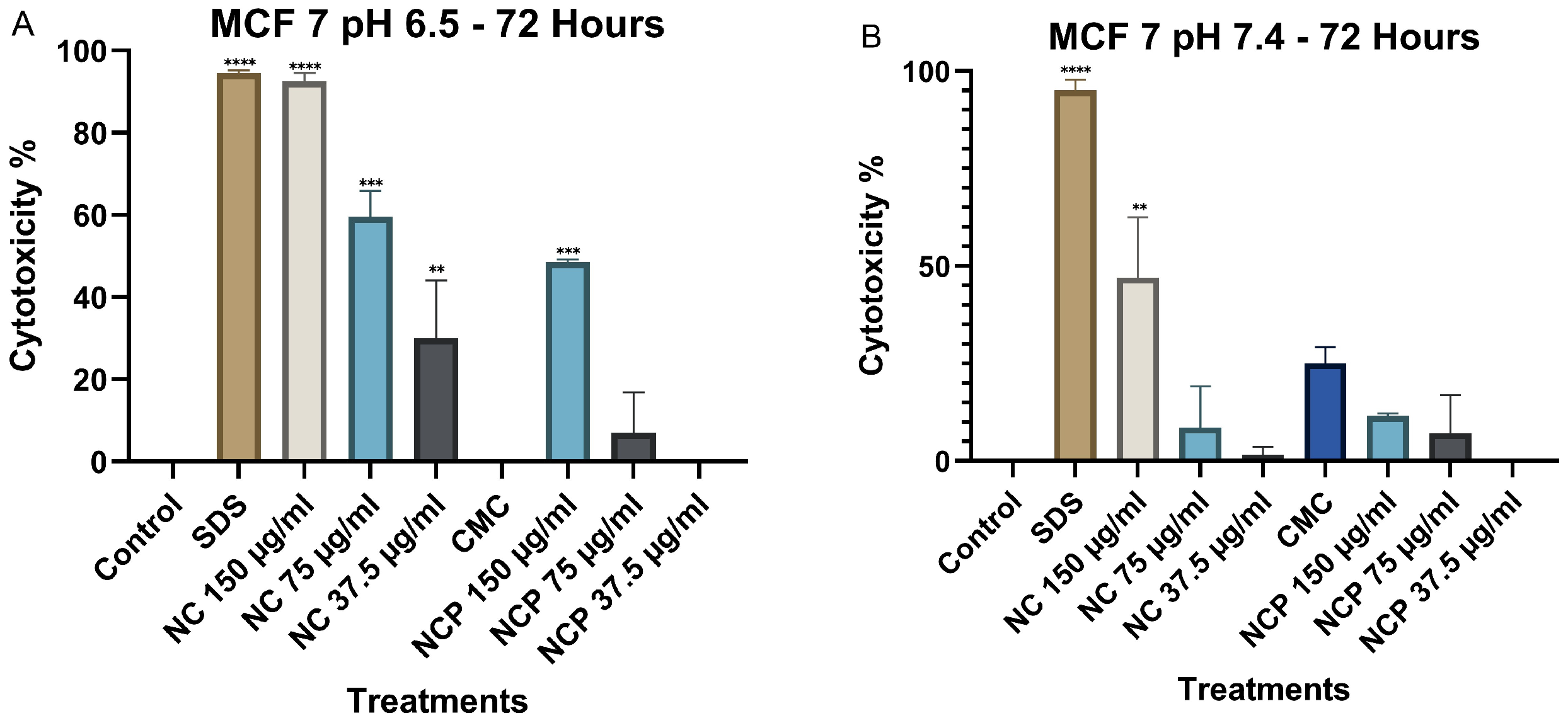

When we analyzed the generation of ROS, our results showed that, in the MCF 7 and HCT 116 cell lines, the pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites caused the generation of ROS at between 44 and 64% at an acidic pH (6.5) (Figure 11A,C), while at pH 7.4, the generation of ROS was 22–40% (Figure 11B,D).

Figure 11.

ROS generation in the MCF 7 cell line (A) HCT 116 (B), brightfield and immunofluorescence images of MCF 7 (C) and HCT 116 (D) with H2DCFDA (ns = not significant **** p < 0.0001).

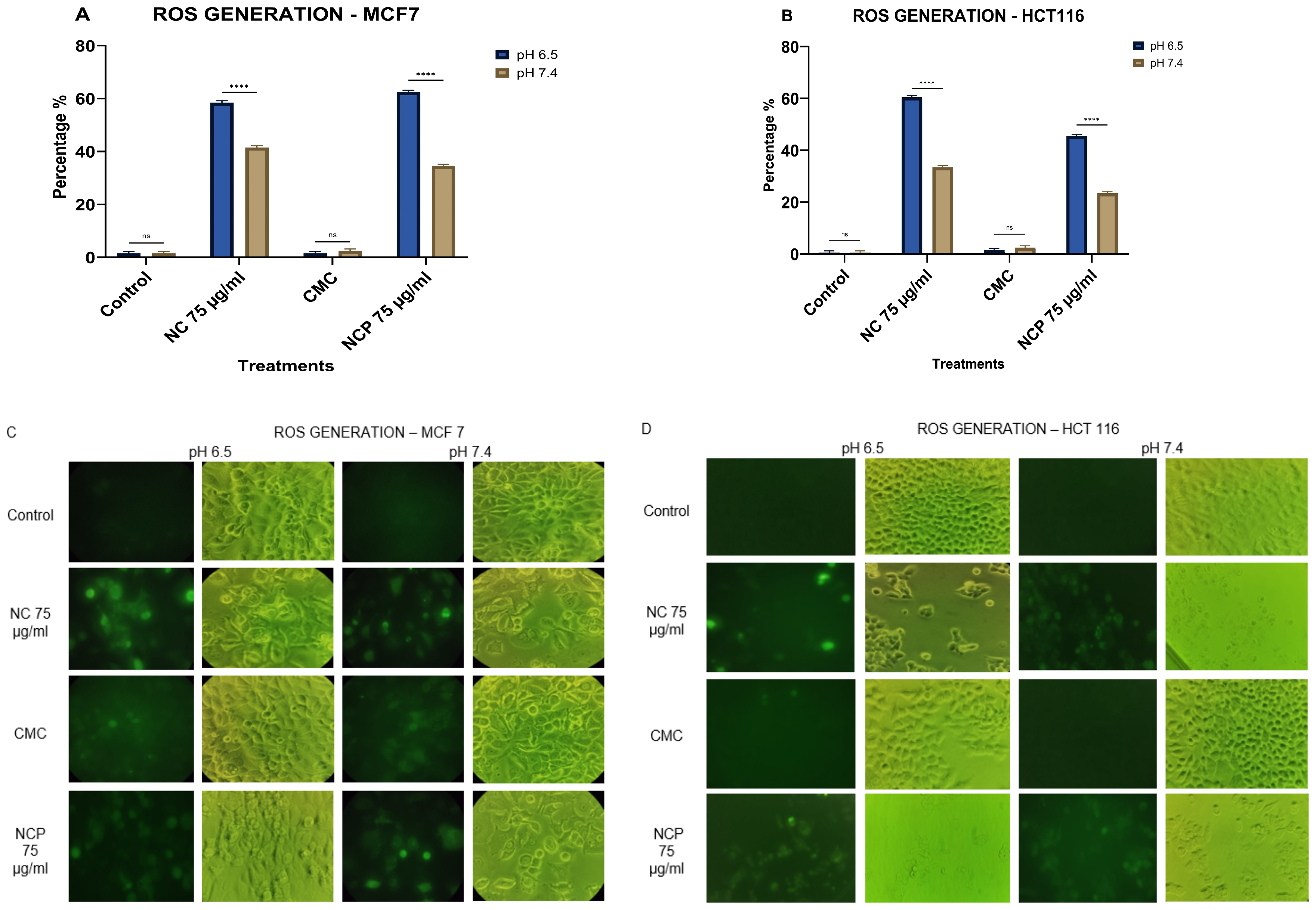

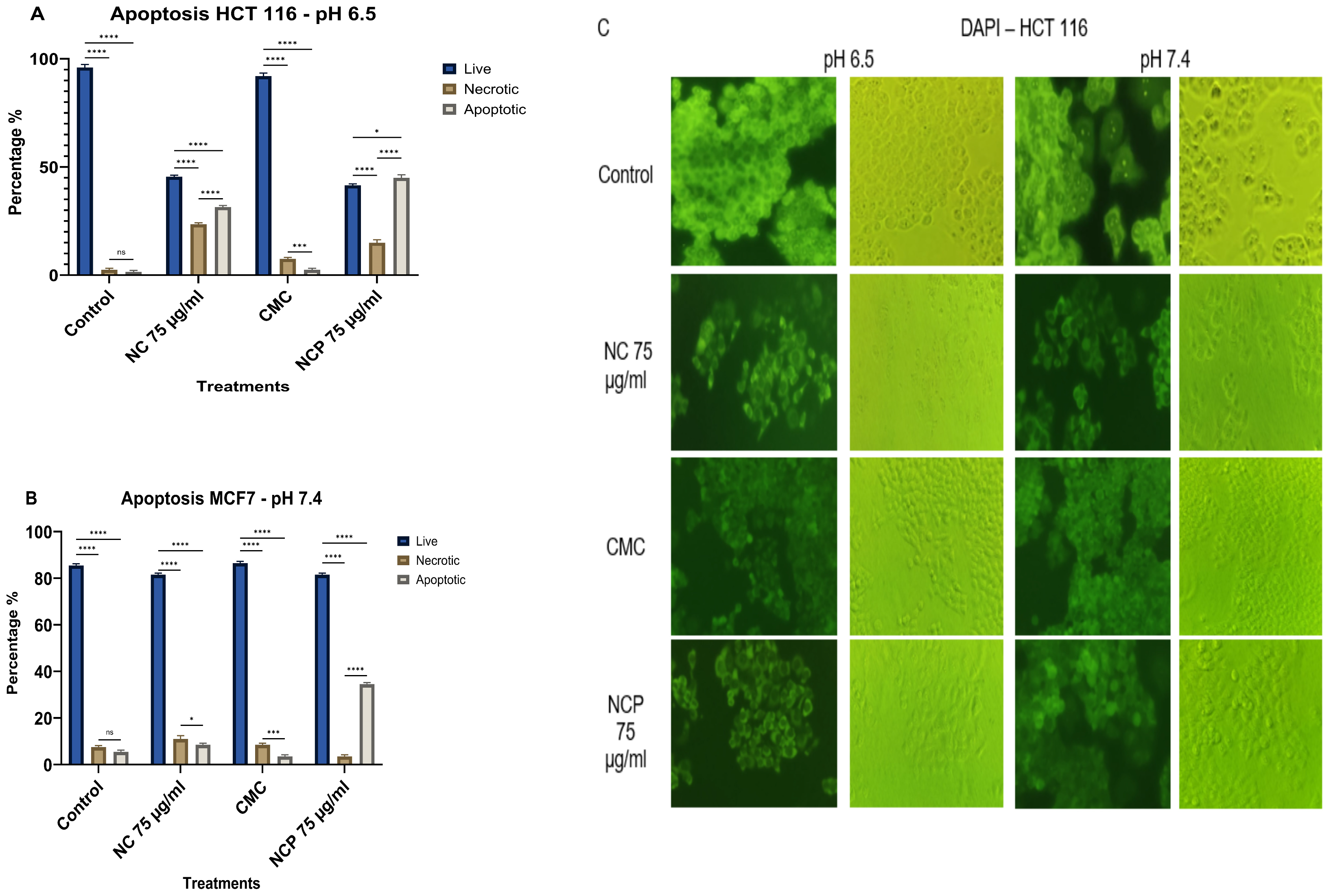

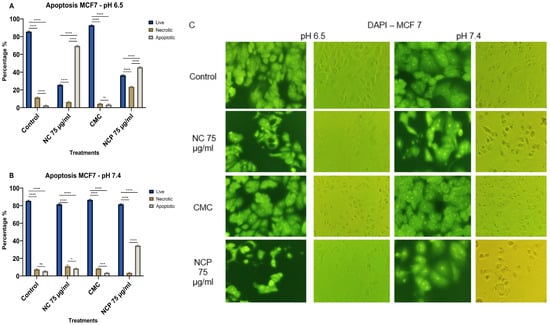

3.4. Apoptosis Results

The effect of the nanocomposite on the MCF 7 cell line caused 69% cell death through apoptosis in the treatment with non-pegylated nanocomposite at pH 6.5 (Figure 12A,C). At pH 7.4, the only treatment that caused 35% cell death by apoptosis was the pegylated nanocomposite treatment. The type of death by necrosis did not exceed 24% and was only induced at pH 6.5 (Figure 12B,C).

Figure 12.

Apoptosis of the MCF 7 cell line at pH 6.5 (A) pH 7.4 (B), brightfield and immunofluorescence images with DAPI (C) (ns = not significant, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

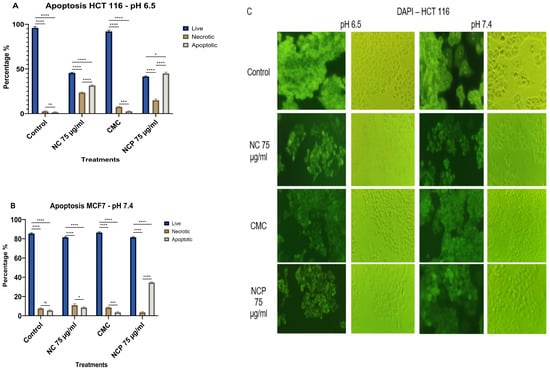

In the HCT 116 cell line, the treatment with non-pegylated nanocomposite at pH 6.5 showed 23% necrotic cells and 32% apoptotic cells, while the pegylated nanocomposite caused 14% necrotic cells and 44% apoptotic cells (Figure 13A,C). At pH 7.4, both the pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites caused less than 20% necrotic and apoptotic cells (Figure 13B,C).

Figure 13.

Apoptosis of the HCT 116 cell line at pH 6.5 (A) pH 7.4 (B), brightfield and immunofluorescence images with DAPI (C) (ns = not significant, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

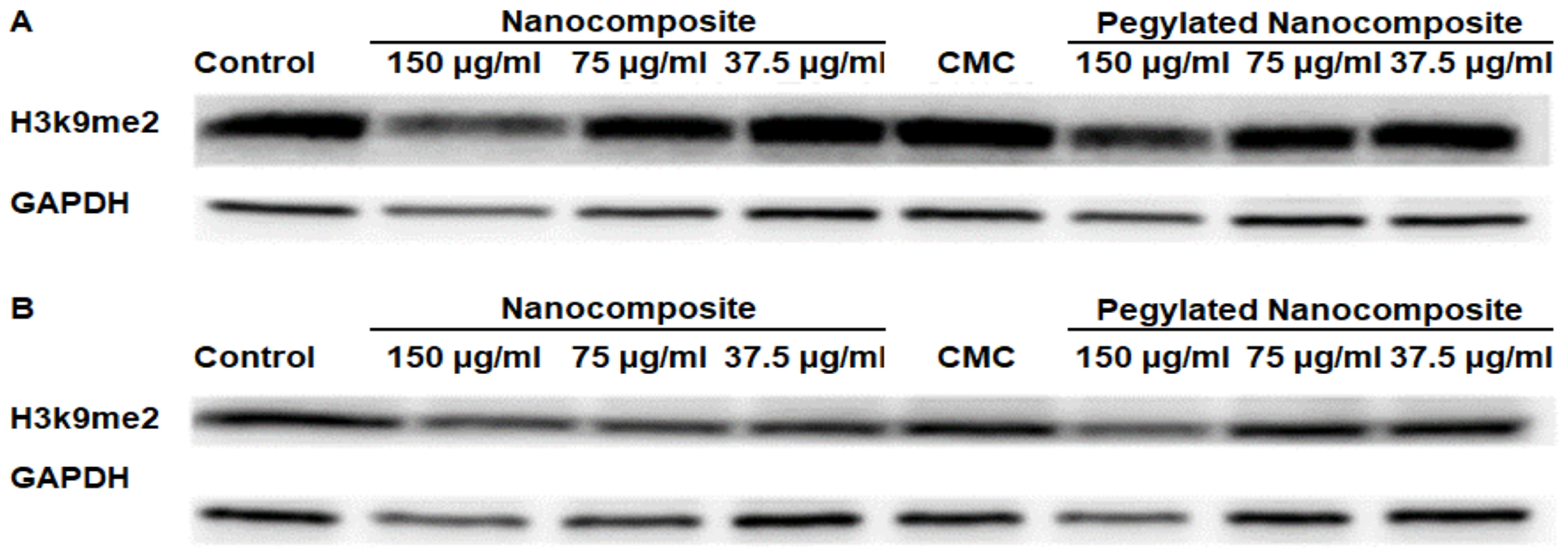

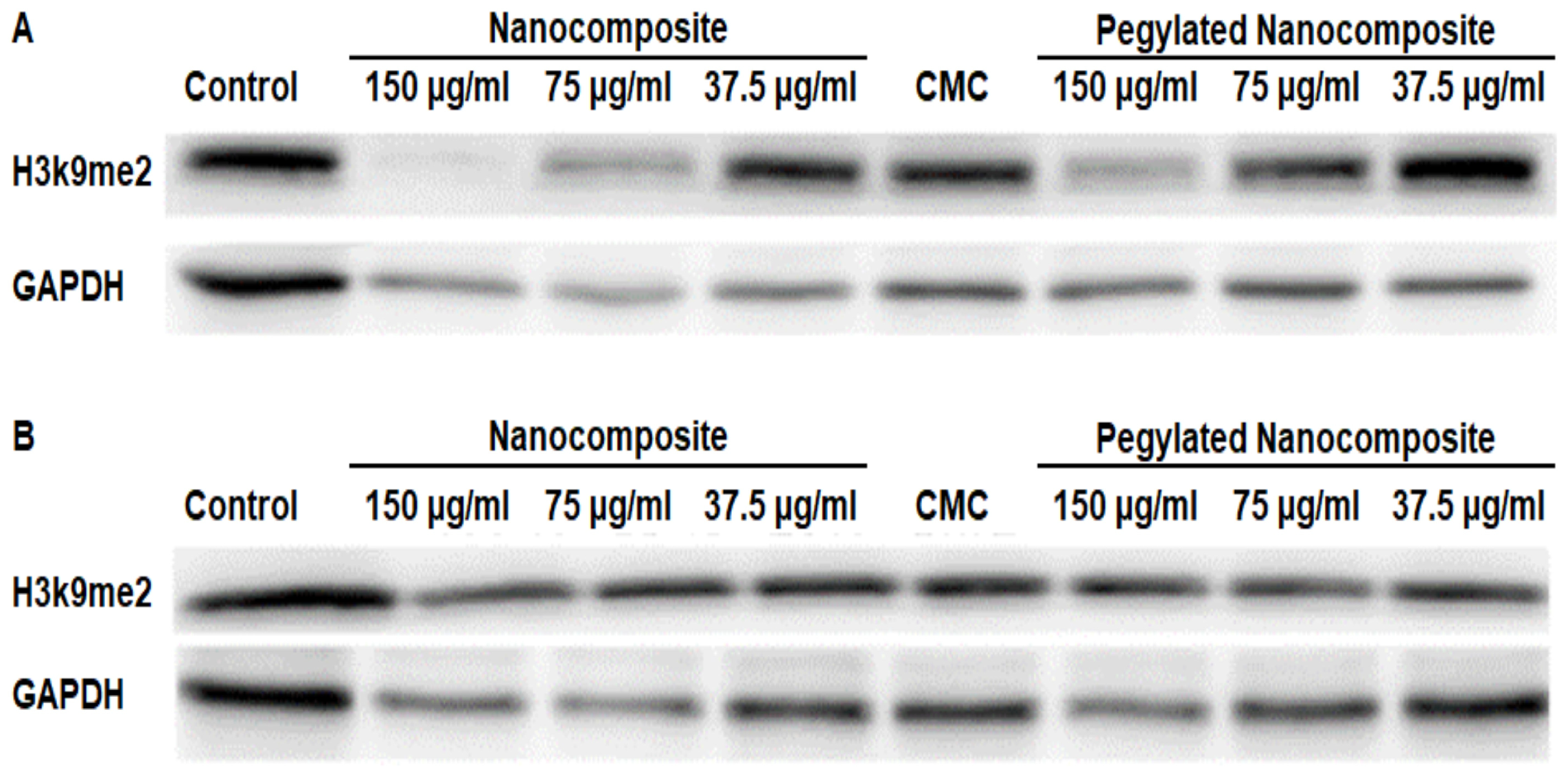

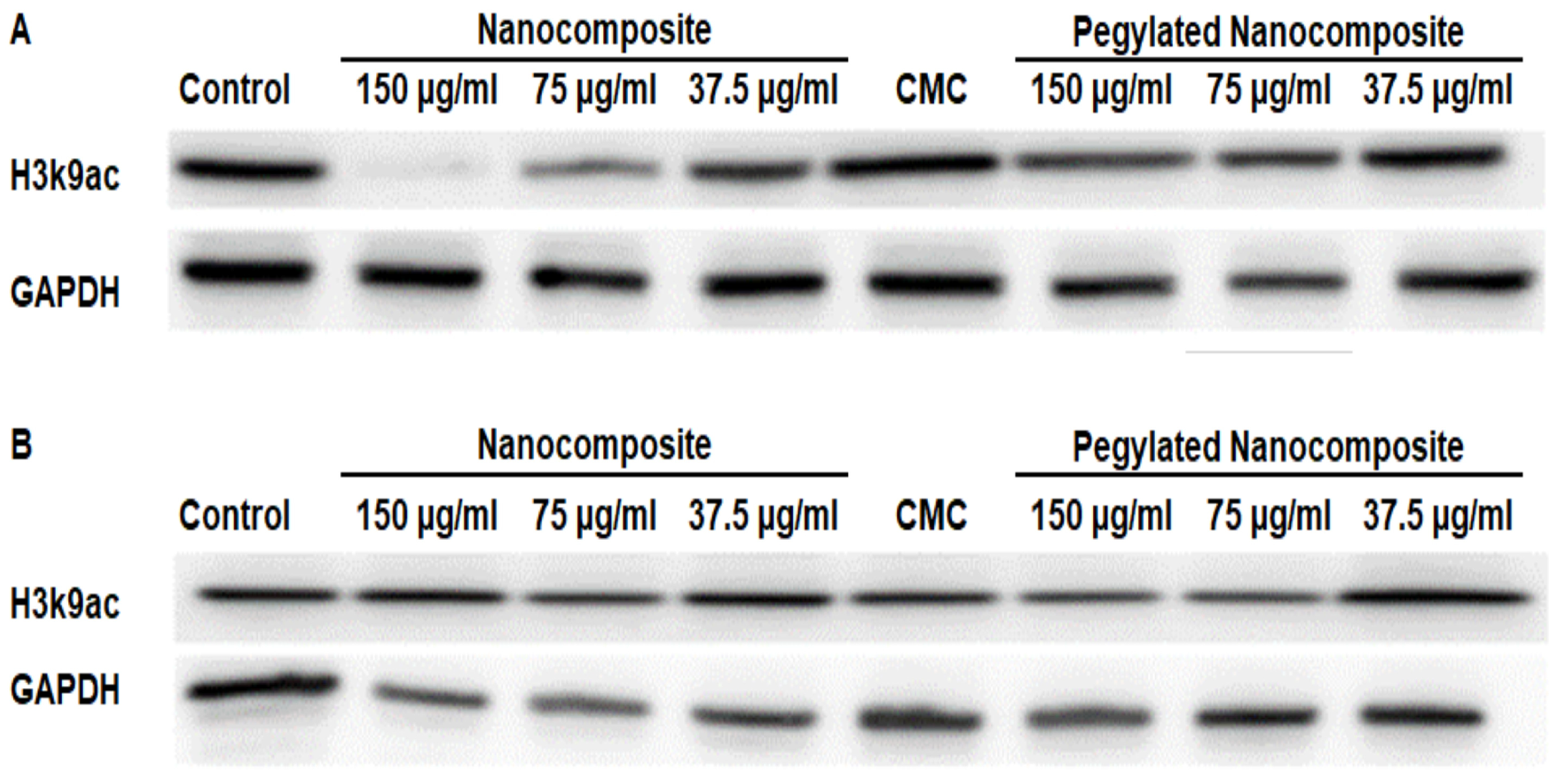

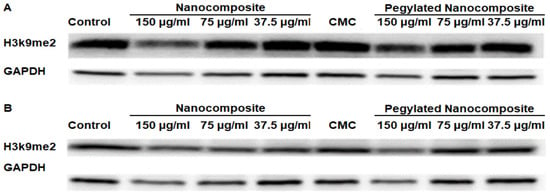

3.5. Protein Expression Analysis by Western Blot

Dimethyl Histone H3 lysine 9 serves as a key regulatory mechanism in chromatin structure and gene expression, representing one of the most important repressive histone marks in mammalian cells [21]. The analysis of protein expression in the HCT 116 cell line showed a clear difference with respect to pH. At pH 6.5, the expression of Dimethyl Histone H3 lysine 9 (H3k9me2) significantly decreased with higher concentrations of the nanocomposite, while with the pegylated nanocomposite, a slight decrease in expression was observed. (Figure 14A). Whereas at pH 7.4, the expression of H3k9me2 shows a slight decrease in the expression of this dimethylated histone for both the pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites, but not comparable to what was shown at pH 6.5. (Figure 14B).

Figure 14.

Expression of H3k9me2 in the HCT 116 cell line, (A) pH 6.5 conditions (B) pH 7.4 conditions.

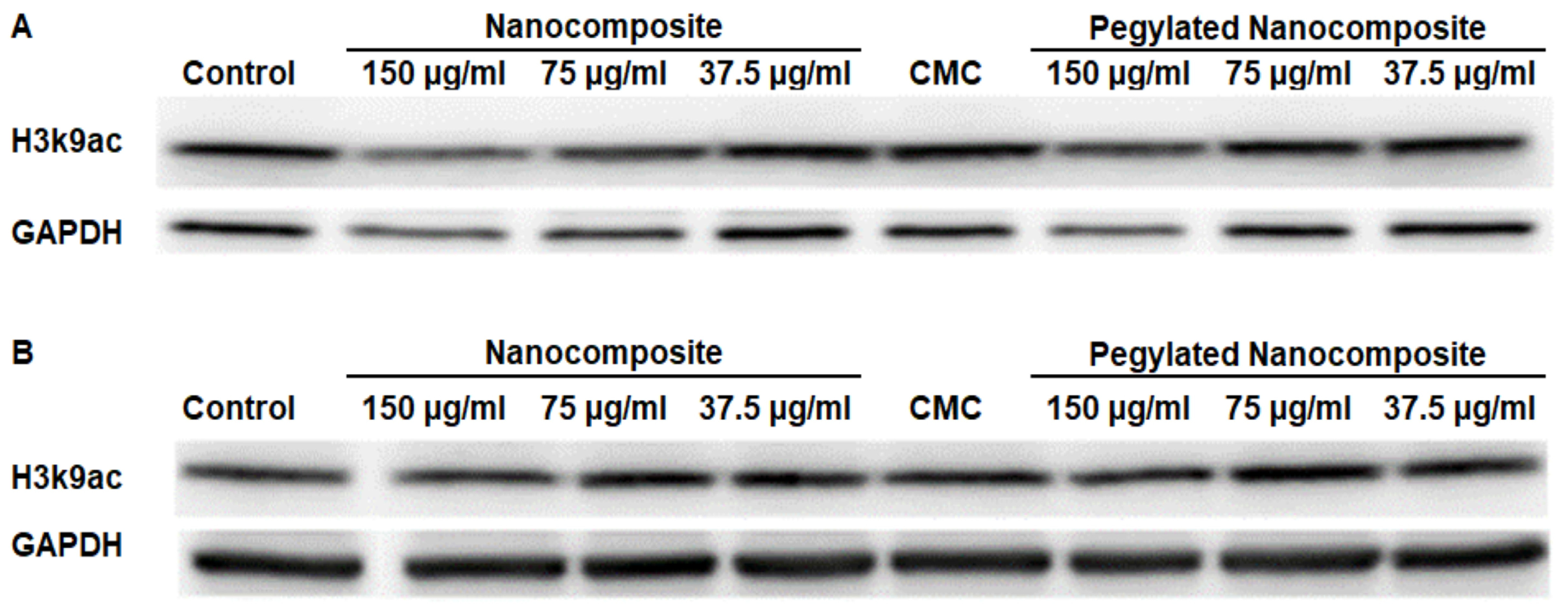

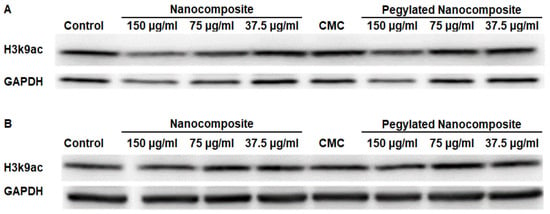

Acetyl Histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9ac) serves as a prominent activating chromatin mark associated with transcriptionally active gene promoters and enhancers [22].At pH 6.5, the results obtained indicate a decrease in expression with the nanocomposite treatment. However, when using the pegylated nanocomposite, the reduction in expression is more moderate. (Figure 15A). In contrast, at pH 7.4 none of the treatments had a significant impact on expression. (Figure 15B).

Figure 15.

Expression of H3k9ac in the HCT 116 cell line, (A) pH 6.5 conditions (B) pH 7.4 conditions.

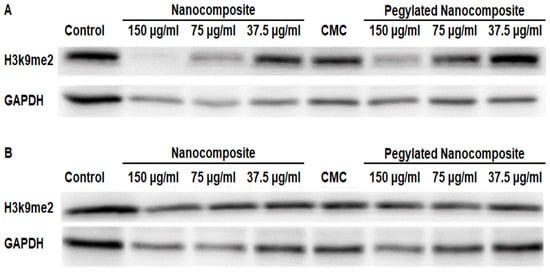

The analysis of protein expression in the MCF7 cell line showed that at pH 6.5, H3k9me2 was significantly inhibited with 150 µg/mL and 75 µg/mL concentrations of the nanocomposite, while the 150 µg/mL pegylated nanocomposite concentration produced an inhibitory effect similar to the 75 µg/mL nanocomposite. (Figure 16A). In the treatments at pH 7.4, no significant changes were observed. (Figure 16B).

Figure 16.

Expression of H3k9me2 in the MCF 7 cell line, (A) pH 6.5 conditions (B) pH 7.4 conditions.

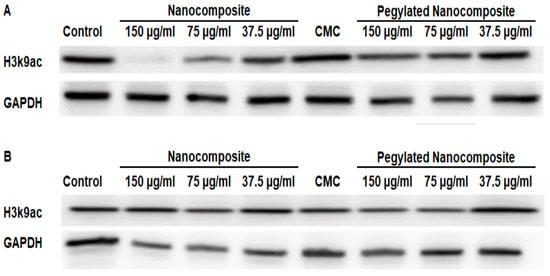

In the MCF 7 cell line, the expression of H3k9ac showed a more pronounced inhibition with the higher concentration of pegylated nanocomposite. In contrast, the same concentration of the pegylated nanocomposite did not cause a significant inhibition of the expression. (Figure 17A). The treatments at pH 7.4 did not produce changes in expression. (Figure 17B).

Figure 17.

Expression of H3k9ac in the MCF 7 cell line, (A) pH 6.5 conditions (B) pH 7.4 conditions.

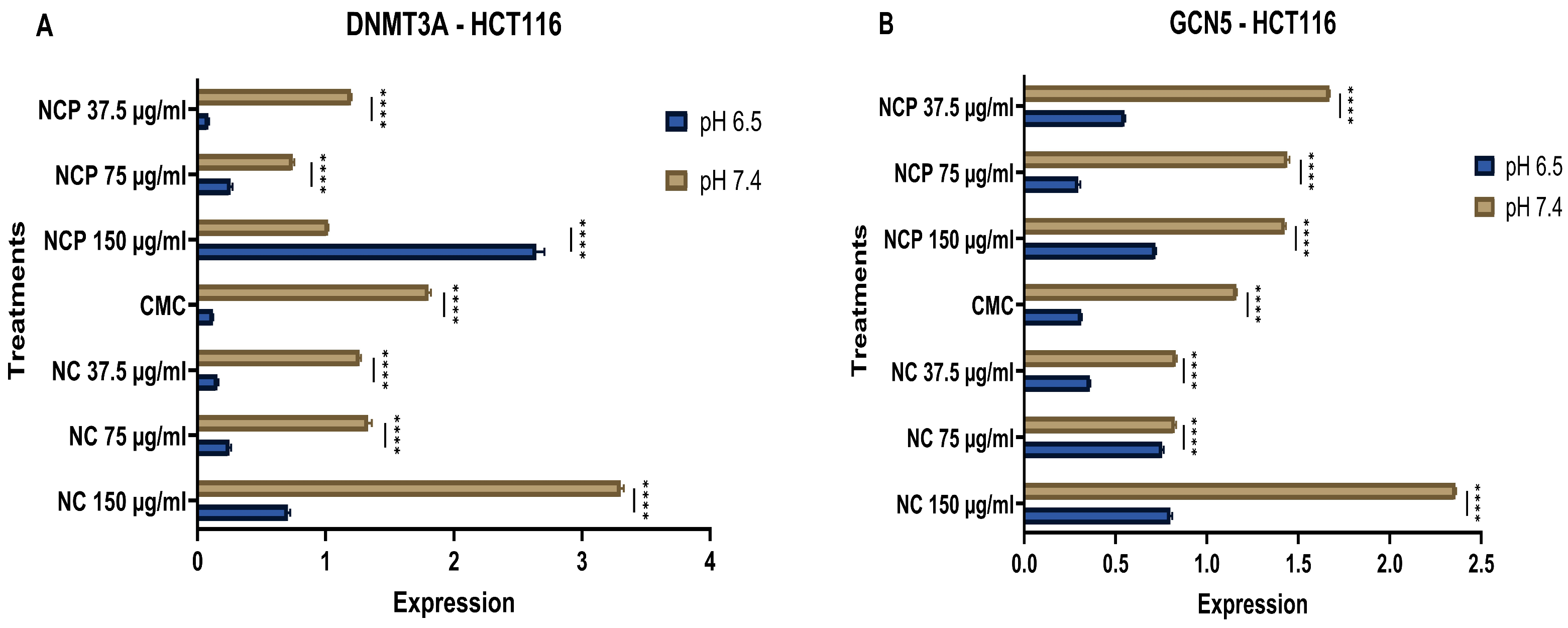

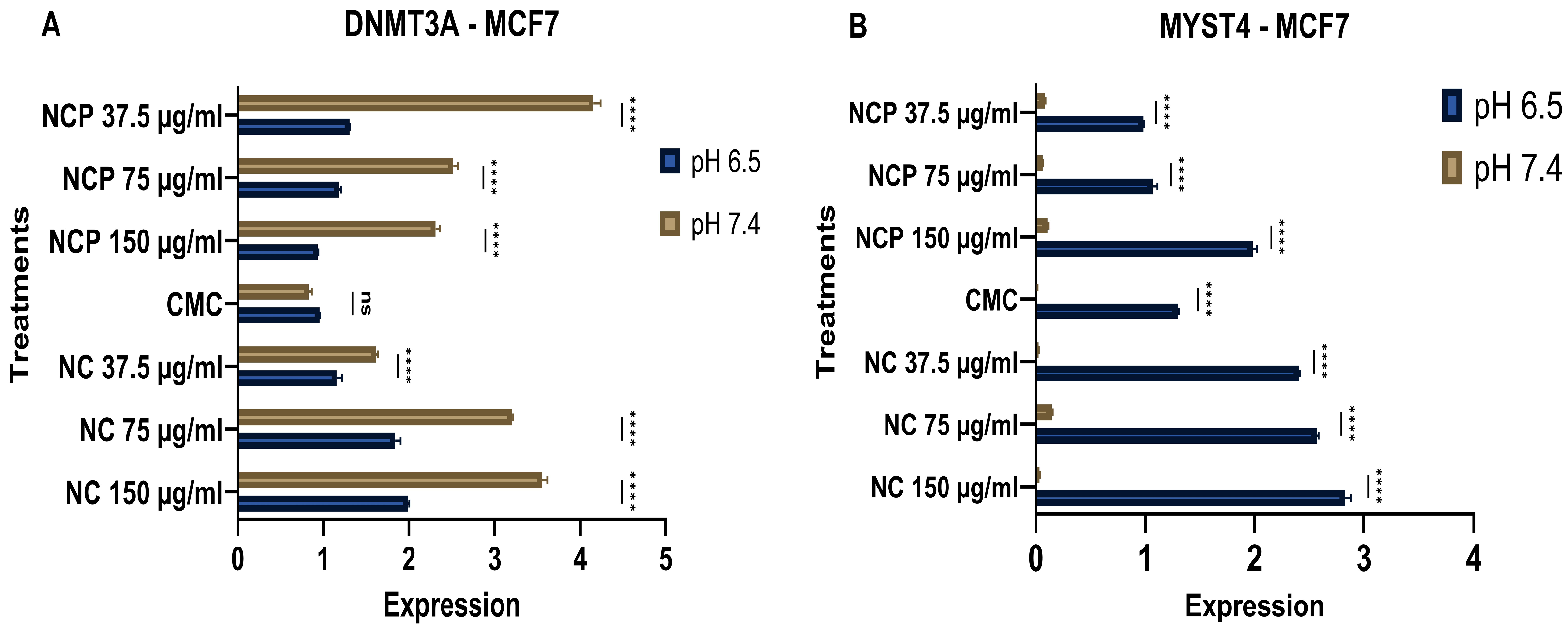

3.6. Analysis of RNA Expression by RT-qPCR

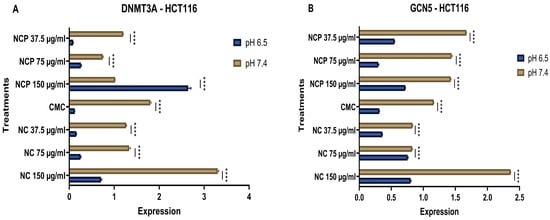

DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a) mediates the de novo methylation of DNA to regulate gene expression and maintain cellular homeostasis [23]. GCN5 is crucial for epigenetic regulation, as it acetylates lysine residues on both histones and non-histone proteins, thereby influencing chromatin structure and gene expression. Additionally, GCN5 acetylates transcription factors, affecting their activity and stability [24]. The results of RNA expression analysis revealed that the nanocomposite has an inhibitory effect. Specifically, the expression levels of DNMT3A and GCN5 in the HCT 116 cell line significantly decreased at the acidic pH of 6.5 compared to pH 7.4. Furthermore, it was noted that the expression of DNMT3A and GCN5 exhibited a directly proportional relationship with the concentrations of both the pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposites (Figure 18A,B).

Figure 18.

Expression of DNMT 3A (A) and GCN 5 (B) in the HCT 116 cell line at acidic (6.5) and physiological pH (7.4) (**** p < 0.0001).

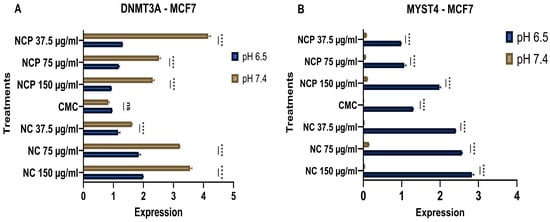

MYST4 functions as a transcriptional coactivator through its histone acetyltransferase activity. This modification relaxes chromatin structure and promotes transcriptional activation of target genes involved in cell cycle progression, DNA replication, and developmental processes [25]. In the MCF 7 cell line, treatment with the nanocomposite showed a clear inhibition of DNMT3A expression under acidic pH conditions (6.5), while the expression increased in relation to the concentration of the pegylated and non-pegylated nanocomposite. (Figure 19A). In contrast, the expression of MYST4 increased at acidic pH (6.5). (Figure 19B).

Figure 19.

Expression of DNMT 3 (A) and MYST 4 (B) in the MCF 7 cell line at acidic (6.5) and physiological pH (7.4) (ns = not significant, **** p < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the synthesis, characterization and anticancer efficacy of the nanocomposite based on pegylated carboxymethyl chitosan-functionalized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs-CMC-PEG) against the MCF7 and HCT116 tumor cell lines, highlighting that the effectiveness is dependent on pH, concentration, and incubation time.

The structural and morphological properties of the nanocomposite were confirmed through various analytical techniques. The UV-Vis spectrum exhibited a plasmonic peak at 412.2 nm, indicating the successful formation of AgNPs within the nanocomposite. The absence of significant spectral changes after PEG addition (data not shown) is consistent with previous studies reporting that polymeric coatings can stabilize metal nanoparticles without substantially affecting their optical properties [26,27].

The FT-IR characterization enabled the identification of key chemical interactions among the carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) matrix, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), and PEG. In the non-pegylated nanocomposite, the signal at 1635.96 cm−1 is associated with the carbonyl (C=O) stretching mode. Additionally, a broad band at 3277.60 cm−1 is attributed to O-H, N-H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl, and amino groups. This spectral pattern is consistent with previous reports on chitosan-based and carboxymethylated nanocomposites, in which amide and carboxylate bands play a central role in stabilizing AgNPs [28,29]. Following pegylation, the FT-IR spectrum preserved the main features of the initial nanocomposite but displayed additional bands indicative of PEG incorporation. These include the signal at 1457.02 cm−1, assigned to CH2 stretching, as well as the bands at 1081.23 and 1349.33 cm−1, corresponding to C–O– stretching vibrations. The appearance of these PEG-related bands confirms its successful integration into the AgNPs-CMC network, in agreement with previous FT-IR studies of PEG-polymer hydrogels and nanocomposites [30]. Complementary investigations on chitosan-PEG-Ag systems have similarly reported changes within the 1000–1300 cm−1 region, attributed to PEG interactions with both the polymer matrix and metal nanoparticles [31].

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses confirmed a monodisperse distribution with an average hydrodynamic size of approximately 258.4 nm, an optimal dimension to avoid rapid renal clearance and to facilitate tumor penetration [32]. The observed colloidal stability also indicates synergistic interactions among CMC, PEG, and AgNPs components, preventing aggregation and maintaining functionality in complex biological media [26].

Since the morphology of nanoparticles has a direct impact on their biological behavior, SEM morphological characterization revealed that the AgNPs have a uniform average size of 14 nm and a spherical shape, features that enhance surface activity and interactions with biomolecules. These attributes are essential in drug-delivery systems to improve encapsulation efficiency and sustained release [33]. Previous studies have demonstrated that silver nanoparticles within the 10–20 nm range display high surface reactivity and strong biomolecular interaction capacity [34].

The carboxymethyl chitosan-functionalized silver nanoparticles can induce a high rate of cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Furthermore, studies emphasize the importance of considering multiple variables, such as pH [35], and concentration [36], when evaluating the cytotoxic effects of nanoparticles. In this work, it is also observed that AgNPs-CMC-PEG induce significant cytotoxicity at pH 6.5 for both cell lines, suggesting that their rapid release in low pH environments optimizes their cytotoxic effect. These results align with previous studies that utilizing carboxymethyl chitosan based nanocomposite, where drug release occurred at an acidic pH (5.0) [37]. This behavior is primarily attributed to the high amino acid content of chitosan, which makes it readily soluble in acidic solutions but insoluble in neutral or alkaline conditions [38,39]. Similarly, a nanocomposite of essential oils with trimethyl chitosan exhibited effects at acidic pH, similar to our nanocomposite [40]. The cationic nature of carboxymethyl chitosan enhances adhesion through electrostatic interactions with negatively charged mucosal surfaces, resulting in improved drug internalization in cancer cells. Additionally, a nanocomposite of thermosensitive chitosan nanoparticles with poly (N-vinylcaprolactam) was found to remain stable at physiological pH. However, at acidic pH, the chitosan coating experienced degradation or alteration, facilitating the release of nanoparticles or metal ions, thereby increasing cellular toxicity [41]. The stability of natural polymers like chitosan is pH-dependent, directly affecting the activity of nanoparticles and their interaction with cellular components [42,43,44,45,46].

Another key aspect of this study is the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles. AgNPs can induce nuclear fragmentation in cancer cells, indicating a pro-apoptotic effect [47]. Furthermore, it has also been demonstrated that AgNPs generate ROS and trigger apoptosis through the p53 and caspase pathways [48]. ROS influence the activity of histone-modifying enzymes such as methyltransferases and acetyltransferases, leading to dynamic changes in H3K9 methylation and acetylation that regulate apoptosis-related gene expression. ROS induced enrichment of H3K9me2 can silence survival genes to promote apoptosis, whereas H3K9 acetylation may activate oncogenes in tumor cells exposed to moderate ROS levels [49,50]. Additionally, it has been shown that the functionalization of nanoparticles with polymers such as chitosan or PEG not only enhances their stability under physiological conditions but also improves their accumulation in tumor tissues due to controlled release in an acidic environment [51]. Our findings, in comparison to other studies employing silver nanoparticles alone and carboxymethyl chitosan-functionalized silver nanoparticles, reinforce the theory that functionalized nanoparticles exhibit an affinity for cancer cells, facilitating controlled drug release in acidic environments and promoting cell death through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Consequently, the AgNPs-CMC-PEG is a potential agent for applications in anticancer therapies, consistent with previous studies on silver nanoparticles [52].

In our study, we observed that the AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite led to a decrease in the expression of H3K9me2 in the MCF7 and HCT116 cell lines. Methylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 is known to be associated with transcriptional repression and gene silencing, so the reduction could be linked to the activation of tumor suppressor genes [53]. Furthermore, the decrease in H3K9me2 has been correlated with the reactivation of genes that promote apoptosis in prostate cancer [54]. On the other hand, the role of histone demethylases, such as KDM3A, is crucial in regulating H3K9me2. KDM3A has been shown to be a specific demethylase for H3K9me1/2, and its activity is necessary for gene activation in the context of colorectal cancer [55]. Inhibition of the methyltransferase G9a, responsible for H3K9 methylation, has shown promising results in reducing tumorigenicity and stemness in cancer cells, suggesting that regulation of H3K9me2 could be an effective therapeutic target [56,57]. Therefore, the decrease in H3K9me2 in our treated cell lines may indicate an epigenetic reprogramming induced by the nanocomposite, preferentially at acidic pH, which enhances the response to anticancer treatments. Additionally, the effect of the nanocomposite on the acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9ac) has important implications for the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in cancer. It has been observed that H3K9ac levels increase in breast cancer as adenomas progress to adenocarcinomas [58]. Since acetylation of this histone is associated with the activation of gene expression, hyperacetylation may favor the expression of proto-oncogenes, while hypoacetylation has been linked to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes [59]. These findings suggest that epigenetic regulation plays a fundamental role in the anticancer mechanism of the AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite. The interaction between histone methylation and anticancer treatments could open new avenues for developing more effective therapeutic strategies that integrate epigenetic modification as a complementary approach in the fight against cancer.

In accordance with our findings, we observed a decrease in the expression of the GCN5 gene in the HCT116 cell line following treatment with the nanocomposite. It is noteworthy that GCN5 overexpression is associated with cell proliferation and resistance to cell death in various types of cancer, including colorectal cancer. Additionally, the therapeutic implications of modulating GCN5 suggest that its regulation could represent an effective strategy in the treatment of this disease [60]. In this context, GCN5 may be overexpressed in colon cancer, promoting the transcription of genes that favor cell growth and division, as well as resistance to apoptosis, since GCN5 can help cancer cells evade programmed cell death by regulating anti-apoptotic genes [24].

On the other hand, abnormal expression of MYST4 is closely associated with various types of human cancers [61]. In our research, we observed that the nanocomposite used caused an increase in MYST4 expression under acidic pH in the MCF7 cell line. This histone acetyltransferase has been implicated in the progression of solid tumors, including ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and liver cancer [25]. However, recent studies suggest that MYST4 may also exhibit tumor suppressor like properties in certain contexts [62]. For instance, lower expression of MYST4 has been associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma, indicating a potential tumor suppressive role in liver cancer [63]. Therefore, the observed increase in MYST4 expression at acidic pH may have context-dependent effects on tumor progression, which warrants further investigation.

Finally, Dnmt3a is a key methyltransferase in the regulation of DNA methylation [64]. Our results reveal a significant decrease in the expression of Dnmt3a under acidic pH conditions (6.5). This finding is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the sensitivity of DNMT3A to various external factors. For example, it has been observed that the use of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in NL20 and A-431 cell lines inhibits the expression of Dnmt3a [65]. Similarly, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in the LO2 cell line also inhibit the expression of Dnmt3a [66]. Additionally, the effect of a chitosan hydrogel with curcumin on glioblastoma was evaluated, where the nanocomposite caused inhibition of DNMT3A expression [67]. This effect was corroborated by another study that evaluated a chitosan-based quercetin hydrogel (ChiNH/Q), yielding similar results [68]. Furthermore, it has been reported that the use of silver nanoparticles resulted in a decrease in the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A and their relationship with autophagy [66]. These findings highlight the importance of Dnmt3a in epigenetic regulation and its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer.

To summarize, the AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite demonstrates anticancer activity against the MCF7 and HCT116 cancer cell lines, with its efficacy is influenced by acidic pH and concentration. This pH-dependent behavior is associated with the solubility and cationic properties of carboxymethyl chitosan, which facilitate drug release and improve cellular uptake in the acidic environments of tumors. The nanocomposite reduces levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9ac. It also modulates histone acetyltransferases like GCN5 and MYST4. Furthermore, it downregulates the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A. These epigenetic modifications, along with ROS-mediated apoptosis and pH-responsive drug delivery are beneficial for anticancer effects. Despite the relevance of the present findings, some limitations should be acknowledged. All experiments were performed in vitro, which may not fully reflect the complexity of the in vivo tumor microenvironment; therefore, further validation in appropriate in vivo models is required. Although the AgNPs-CMC-PEG nanocomposite exhibited clear pro-apoptotic effects, the specific apoptotic pathways were not dissected, and future studies will address intrinsic and extrinsic signaling mechanisms. Moreover, the concurrent increase in ROS production and apoptosis-related features should be interpreted as correlative, as causality was not directly investigated. Finally, comparison with standard chemotherapeutic agents was beyond the scope of this proof-of-concept study and will be explored in future work to assess translational relevance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biophysica6010009/s1, Table S1: HCT 116 Citotoxicity (%) assessed by MTT assay under different pH conditions; Table S2: MCF 7 Citotoxicity assessed by MTT assay under different pH conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.A.-C. and C.V.-G.; methodology, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., G.G.T.-G., and S.E.L.-G.; software, G.G.T.-G. and S.E.L.-G.; validation, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., J.A.-P., and H.F.Z.-A.; formal analysis, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., J.A.-P., and H.F.Z.-A.; investigation, G.G.T.-G., S.E.L.-G., C.A.A.-C., and C.V.-G.; resources, C.A.A.-C. and C.V.-G.; data curation, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., and H.F.Z.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., G.G.T.-G., and S.E.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, C.A.A.-C., C.V.-G., H.F.Z.-A., and J.A.-P.; visualization, G.G.T.-G. and S.E.L.-G.; supervision, C.A.A.-C. and C.V.-G.; project administration, C.A.A.-C. and C.V.-G.; funding acquisition, C.A.A.-C. and C.V.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, Peru. UNSA INVESTIGA. Contract N°IBAIB-11-2019-UNSA.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kiri, S.; Ryba, T. Cancer, Metastasis, and the Epigenome. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global Colorectal Cancer Burden in 2020 and Projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, E.; Tanis, P.J.; Vleugels, J.L.A.; Kasi, P.M.; Wallace, M.B. Colorectal Cancer. Lancet 2019, 394, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding Breast Cancer as a Global Health Concern. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Xu, B. Breast Cancer: An up-to-Date Review and Future Perspectives. Cancer Commun. Lond. Engl. 2022, 42, 913–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shanti, A. Effect of Exogenous pH on Cell Growth of Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swietach, P. What Is pH Regulation, and Why Do Cancer Cells Need It? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Khan, A.; Li, J.; Naeem, M.; Khalil, A.A.K.; Khan, K.; Qasim, M. Nanotechnology, A Tool for Diagnostics and Treatment of Cancer. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, C.; Yang, J.; ZhuGe, Q.; Hu, J. Recent Advances in Tissue Plasminogen Activator-Based Nanothrombolysis for Ischemic Stroke. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2019, 58, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, K.; Chen, Y. In Situ Generation of Silver Nanoparticles and Nanocomposite Films Based on Electrodeposition of Carboxylated Chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 242, 116391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Liu, P. pH-Responsive Surface Charge Reversal Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Based Drug Delivery System for pH and Reduction Dual-Responsive Triggered DOX Release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azharuddin, M.; Zhu, G.H.; Das, D.; Ozgur, E.; Uzun, L.; Turner, A.P.F.; Patra, H.K. A Repertoire of Biomedical Applications of Noble Metal Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 6964–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abass Sofi, M.; Sunitha, S.; Ashaq Sofi, M.; Khadheer Pasha, S.K.; Choi, D. An Overview of Antimicrobial and Anticancer Potential of Silver Nanoparticles. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Dias, F.; Machado, V.; Medeiros, R.; Prior, J.A.V. Cytotoxic Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Methods in Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14308–14335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekladious, I.; Colson, Y.L.; Grinstaff, M.W. Polymer–Drug Conjugate Therapeutics: Advances, Insights and Prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zea Álvarez, J.L.; Talavera Núñez, M.E.; Arenas Chávez, C.; Pacheco Salazar, D.; Osorio Anaya, A.M.; Vera Gonzales, C. Obtención y caracterización del nanocomposito: Nanopartículas de plata y carboximetilquitosano (NPsAg-CMQ). Rev. Soc. Quím. Perú 2019, 85, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M.A. Synthesis of a Novel Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Silver-Ginger Nanocomposite, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Efficacy. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 8, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.R.; Seoudi, R.S.; Sabaa, M.W. Synthesis and Characterization of Cross-linked Polyethylene Glycol/Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogels. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2015, 34, 21479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-W.; Cho, H.-J.; Lee, H.J.; Jin, H.-E.; Maeng, H.-J. Polyethylene Glycol-Decorated Doxorubicin/Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Gold Nanocomplex for Reducing Drug Efflux in Cancer Cells and Extending Circulation in Blood Stream. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padeken, J.; Methot, S.P.; Gasser, S.M. Establishment of H3K9-Methylated Heterochromatin and Its Functions in Tissue Differentiation and Maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, S.; Trovato, M.; Vitaloni, O.; Fantini, M.; Chirichella, M.; Tognini, P.; Cornuti, S.; Costa, M.; Groth, M.; Cattaneo, A. Acetylation-Specific Interference by Anti-Histone H3K9ac Intrabody Results in Precise Modulation of Gene Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Emperle, M.; Guo, Y.; Grimm, S.A.; Ren, W.; Adam, S.; Uryu, H.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Chen, D.; Yin, J.; et al. Comprehensive Structure-Function Characterization of DNMT3B and DNMT3A Reveals Distinctive de Novo DNA Methylation Mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.E.; Jakaria, M.; Akther, M.; Cho, D.-Y.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. The GCN5: Its Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potentials. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L.; Sheu, J.J.-C.; Lin, H.-P.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Chang, C.Y.-Y.; Chen, C.-M.; Cheng, J.; Mao, T.-L. The Overexpression of MYST4 in Human Solid Tumors Is Associated with Increased Aggressiveness and Decreased Overall Survival. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Tang, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, Q. Effects of Polyethylene Glycol on the Surface of Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 10748–10764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Foyez, T.; Krishna, S.B.N.; Poda, S.; Imran, A.B. Recent Advances of Silver Nanoparticle-Based Polymer Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 8480–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Qi, C. Quaternized Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Based Silver Nanoparticles Hybrid: Microwave-Assisted Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, P.K.; Mahadevan, R.; Digita, P.A.; Visnuvinayagam, S.; Kumar, L.R.G.; Mathew, S.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Anandan, R. Synthesis and Biochemical Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Grafted Chitosan (Chi-Ag-NPs): In Vitro Studies on Antioxidant and Antibacterial Applications. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.S.B.; Akhtar, N.; Minhas, M.U.; Mahmood, A.; Khan, K.U. Synthesis and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanosponges with Cyclodextrin Blends for Drug Solubility Improvement. Gels 2022, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, M.N.; Pereira, F.M.; Rocha, M.A.; Ribeiro, J.G.; Junges, A.; Monteiro, W.F.; Diz, F.M.; Ligabue, R.A.; Morrone, F.B.; Severino, P.; et al. Chitosan and Chitosan/PEG Nanoparticles Loaded with Indole-3-Carbinol: Characterization, Computational Study and Potential Effect on Human Bladder Cancer Cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 124, 112089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, J.; Jan Hendriks, A.; Nolte, T.M. Clearance of Nanoparticles from Blood: Effects of Hydrodynamic Size and Surface Coatings. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrato-Barragan, J.A.; Casillas-Figueroa, F.; Luna-Vázquez-Gómez, R.; Ruiz-Ruiz, B.; Garibo, D.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.G.; Pestryakov, A.; Bogdanchikova, N. Shedding Light on the Structure of Silver Nanoparticles with Promising Properties for Nano-Oncology. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2025, 27, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolai, J.; Mandal, K.; Jana, N.R. Nanoparticle Size Effects in Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6471–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, D.H.; El-Mazaly, M.H.; Mohamed, R.R. Synthesis of Biodegradable Antimicrobial pH-Sensitive Silver Nanocomposites Reliant on Chitosan and Carrageenan Derivatives for 5-Fluorouracil Drug Delivery toward HCT116 Cancer Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 231, 123364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gounden, S.; Daniels, A.; Singh, M. Chitosan-Modified Silver Nanoparticles Enhance Cisplatin Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 11, 10572–10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Jia, C.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, T.; Li, C.; Cheng, X. Dual-pH Responsive Chitosan Nanoparticles for Improving in Vivo Drugs Delivery and Chemoresistance in Breast Cancer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 290, 119518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current Advances in Chitosan Nanoparticles Based Drug Delivery and Targeting. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh-Khosroshahi, M.; Pourmadadi, M.; Yazdian, F.; Rashedi, H.; Navaei-Nigjeh, M.; Rasekh, B. Chitosan/Agarose/Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanocomposite as an Efficient pH-Sensitive Drug Delivery System for Anticancer Curcumin Releasing. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 74, 103443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyebuchi, C.; Kavaz, D. Chitosan And N, N, N-Trimethyl Chitosan Nanoparticle Encapsulation of Ocimum Gratissimum Essential Oil: Optimised Synthesis, In Vitro Release and Bioactivity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 7707–7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Williams, G.R.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Jiao, J.; Zhu, L.-M. A Chitosan-Based Cascade-Responsive Drug Delivery System for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeong, M.S.; Park, Y.I.; Motoyama, K.; Kim, M.W.; Kwon, S.-H.; Choi, J.H. Hyaluronic Acid-Decorated Glycol Chitosan Nanoparticles for pH-Sensitive Controlled Release of Doxorubicin and Celecoxib in Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. Bioconjug. Chem. 2020, 31, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, A.J.; Costa Lima, S.A.; Afonso, C.M.M.; Reis, S. Mucoadhesive and pH Responsive Fucoidan-Chitosan Nanoparticles for the Oral Delivery of Methotrexate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, M.K.; Safdar, S.; Buabeid, M.; Ashames, A.; Akhtar, M.; Murtaza, G. Alginate-Coated Chitosan Nanoparticles for pH-Dependent Release of Tamoxifen Citrate. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2022, 17, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, D.; Jiang, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Lun, J.; Jia, R.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W. Curcumin-Loaded pH-Sensitive Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Liver Cancer. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 628–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, K.; Vijayakumar, M.; Janani, B. Chitosan-Mediated Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Nanoparticle Characterisation and in Vitro Assessment of Anticancer Activity in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.; AL-Abdan, M.; Albasher, G.; Alarifi, S. Effects of Green Silver Nanoparticles on Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Normal and Cancerous Human Hepatic Cells in Vitro. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Wahab, R. Silver Nanoparticles: An Instantaneous Solution for Anticancer Activity against Human Liver (HepG2) and Breast (MCF-7) Cancer Cells. Metals 2022, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Rishi, B.; George, N.G.; Kushwaha, N.; Dhandha, H.; Kaur, M.; Jain, A.; Jain, A.; Chaudhry, S.; Singh, A.; et al. Recent Advances and Future Directions in Etiopathogenesis and Mechanisms of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Treatment. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2023, 29, 1611415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrishrimal, S.; Kosmacek, E.A.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E. Reactive Oxygen Species Drive Epigenetic Changes in Radiation-Induced Fibrosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4278658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ding, H. pH-Responsive Nanoparticles for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Brief Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeragoni, D.; Deshpande, S.; Rachamalla, H.K.; Ande, A.; Misra, S.; Mutheneni, S.R. In Vitro and in Vivo Anticancer and Genotoxicity Profiles of Green Synthesized and Chemically Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 2324–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Fang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Fang, X.; Miao, Q.R. Epigenetically Down-Regulated Acetyltransferase PCAF Increases the Resistance of Colorectal Cancer to 5-Fluorouracil. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.G.; Venkatesan, J.; Shim, M.S. Selective Anticancer Therapy Using Pro-Oxidant Drug-Loaded Chitosan–Fucoidan Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Long, Q.-Y.; Tang, S.-B.; Xiao, Q.; Gao, C.; Zhao, Q.-Y.; Li, Q.-L.; Ye, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.-Y.; et al. Histone Demethylase KDM3A Is Required for Enhancer Activation of Hippo Target Genes in Colorectal Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 2349–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangeni, R.P.; Yang, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Guo, C.; Yun, X.; Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Raz, D.J. G9a Regulates Tumorigenicity and Stemness through Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Reprogramming in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haebe, J.R.; Bergin, C.J.; Sandouka, T.; Benoit, Y.D. Emerging Role of G9a in Cancer Stemness and Promises as a Therapeutic Target. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.; Kolben, T.; Meister, S.; Kolben, T.M.; Schmoeckel, E.; Mayr, D.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Ditsch, N.; Beyer, S. Expression of H3K4me3 and H3K9ac in Breast Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Castro, E.; Reyes-Vallejo, T.; Máximo-Sánchez, D.; Herrera-Camacho, I.; López-López, G.; Reyes-Carmona, S.; Conde-Rodríguez, I.; Ramírez-Díaz, I.; Aguilar-Lemarroy, A.; Jave-Suárez, L.F.; et al. Histone H3K9 and H3K14 Acetylation at the Promoter of the LGALS9 Gene Is Associated with mRNA Levels in Cervical Cancer Cells. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 2305–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.-W.; Jin, H.-J.; Zhao, W.; Gao, B.; Fang, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, D.D.; Zhang, J.; Fang, D. The Histone Acetyltransferase GCN5 Expression Is Elevated and Regulated by C-Myc and E2F1 Transcription Factors in Human Colon Cancer. Gene Expr. 2015, 16, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neganova, M.E.; Klochkov, S.G.; Aleksandrova, Y.R.; Aliev, G. Histone Modifications in Epigenetic Regulation of Cancer: Perspectives and Achieved Progress. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 83, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.M.; Johnson, R.W. Targeting Histone Modifications in Bone and Lung Metastatic Cancers. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2021, 19, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, H.-J.; Mou, X.-Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Z.-M. Low Expression of KAT6B May Affect Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukatz, M.; Dittrich, M.; Stahl, E.; Adam, S.; De Mendoza, A.; Bashtrykov, P.; Jeltsch, A. DNA Methyltransferase DNMT3A Forms Interaction Networks with the CpG Site and Flanking Sequence Elements for Efficient Methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogribna, M.; Koonce, N.A.; Mathew, A.; Word, B.; Patri, A.K.; Lyn-Cook, B.; Hammons, G. Effect of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on DNA Methylation in Multiple Human Cell Lines. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, D.; Cai, Z.; Zhong, B.; Zhang, H.; Pan, Z.; Ling, X.; Han, Y.; Meng, J.; Li, H.; et al. Increased DNMT1 Involvement in the Activation of LO2 Cell Death Induced by Silver Nanoparticles via Promoting TFEB-Dependent Autophagy. Toxics 2023, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolfathi, S.; Zare, M. The Evaluation of Chitosan Hydrogel Based Curcumin Effect on DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, MEG3, HOTAIR Gene Expression in Glioblastoma Cell Line. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 5977–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaszadeh, S.; Rashidipour, M.; Khosravi, P.; Shahryarhesami, S.; Ashrafi, B.; Kaviani, M.; Moradi Sarabi, M. Biocompatibility, Cytotoxicity, Antimicrobial and Epigenetic Effects of Novel Chitosan-Based Quercetin Nanohydrogel in Human Cancer Cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 5963–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.