Abstract

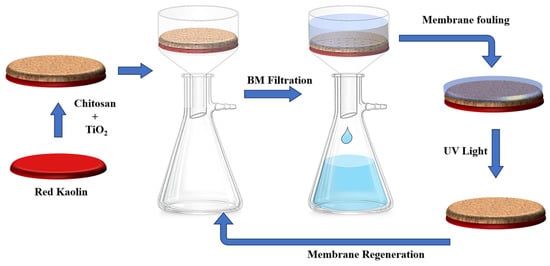

Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) are an innovative technology for water treatment, effectively combining membrane filtration and photocatalysis to enhance contaminant removal while enabling the regeneration of fouled membranes. In this study, a new porous film of chitosan that was impregnated with TiO2 was developed and coated onto a ceramic support by spin coating to form a new porous immobilized PMR. The formed membrane was tested for two reasons: the removal of methylene blue dye by a dead-end filtration process and to demonstrate its ability to self-regenerate under UV exposure. The selective layer of the membrane was characterized using FTIR spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and water permeability tests. The results confirmed the formation of an amorphous film with no chemical interaction between chitosan and TiO2. The membrane exhibited an average water permeability of 10.72 L/m2·h·bar, classifying it as either ultrafiltration (UF) or nanofiltration (NF). Dead-end filtration of methylene blue (10 mg L−1) achieved 99% dye removal based on UV–vis analysis of the permeate, while flux declined rapidly due to fouling. Subsequent UV irradiation removed the deposited dye layer and restored approximately 50% of the initial flux, indicating partial self-regeneration. Overall, spin-coated chitosan–TiO2 layers on ceramic supports provide high dye removal and photocatalytically assisted flux recovery, and further work should quantify photocatalytic degradation during regeneration.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, there has been a growing interest in the application of membrane technology for the treatment of wastewater [1,2,3]. However, the fouling issue remains a significant obstacle for membrane technology, resulting in increased operational costs and the need for frequent membrane replacements [1,4]. Various strategies have been improved to reduce the fouling problem; one of them is cleaning of the membrane unit [5].

The cleaning techniques employed for membrane regeneration can be classified into four main categories: physical, chemical, physico-chemical, and biological methods [6]. Each of these cleaning methods has its advantages and drawbacks, but physico-chemical cleaning is the most applied technique because it combines the speed of physical cleaning with the effectiveness of chemical cleaning, while also considering the cost of cleaning [7].

Photocatalysis is one of the most effective and environmentally friendly physico-chemical cleaning methods for membrane units [8,9,10]. In this cleaning process, a photocatalytic reaction begins when a photocatalyst, such as TiO2, absorbs light. As a result, an electron is excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) of the photocatalyst, creating a positively charged hole in the VB and a negatively charged electron in the CB, forming an electron–hole pair [11,12]. This electron–hole pair actively participates in redox reactions, facilitating the degradation of foulants [13].

In the literature, the type of membranes that combine membrane filtration with photocatalytic degradation is called photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) [14]; and it can be categorized into two main groups [15]: slurry PMRs, where the photocatalyst is in liquid suspension, and immobilized PMRs, where the photocatalyst is immobilized in or on the membrane. Each type has its advantages and disadvantages. However, the process in immobilized PMRs is simpler and cheaper than in slurry PMRs because there is no need to separate or recycle the photocatalyst [16].

Chitosan (CS), derived from the deacetylation of chitin, is a natural biopolymer that stands out as a promising material that is often employed in the production of porous membranes due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, affordability, good hydrophilicity, and excellent sorption properties [17,18]. Furthermore, chitosan has been used to immobilize nanoparticles of TiO2 for use in the photodegradation of textile dyes [19]. However, to our knowledge, it has not been tested in PMRs.

Methylene blue (MB) is a cationic dye that is commonly used for dyeing paper, cotton, wood, and silk [20,21]. Similar to many synthetic dyes, methylene blue can pose various health risks. Inhalation of this compound may lead to respiratory problems, such as shortness of breath and difficulty breathing. When ingested, methylene blue can result in a burning sensation, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastritis. Accidental consumption of a large dose may cause more severe effects, such as abdominal and chest pain, intense headaches, excessive sweating, mental confusion, painful urination, and methemoglobinemia [22,23,24].

Consequently, various water decolorization techniques have been proposed for the removal of methylene blue from effluent and sewage, including chemical and electrocoagulation, oxidation, photocatalytic degradation, biodegradation, biocatalytic degradation, and adsorption [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Other approaches include phytoremediation, vacuum membrane distillation, liquid/liquid extraction, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and microwave treatment [32,33]. However, studies have indicated that most conventional methods come with several drawbacks, including high costs, significant electricity consumption, and the generation of large amounts of harmful waste [34]. In contrast, membrane filtration offers several advantages, such as energy efficiency, reduced chemical usage, and the ability to effectively separate pollutants from water, making it a more sustainable option for water treatment [35].

Therefore, the main focus of this research is the development of a new immobilized PMR membrane, where the photocatalyst TiO2 is immobilized on a thin, porous chitosan layer that is deposited by spin coating on a ceramic support. The membrane is used to eliminate methylene blue through conventional dead-end filtration, while its photocatalytic properties are tested to evaluate the membrane’s ability to self-regenerate under UV light.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

The materials used in this study include titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles with an average particle size of 25 nm (NanoTech Co., Ltd., Shaoxing, China), chitosan (CS, medium molecular weight, 85% deacetylation, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and polyethylene glycol (PEG, molecular weight 400 g/mol, from Fisher Scientific). Acetic acid (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a solvent for chitosan preparation, and methylene blue (98%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)) as a model dye pollutant. All chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Experimental Methods

In this study, 3 membranes were formed: CS-PEG, CS-TiO2, and CS-PEG-TiO2. Only the last membrane was used for the filtration tests; the other membranes were used for the comparison of the characterization results. The membranes were formed by centrifugal deposition of a coating solution on a porous ceramic support, followed by solidification through a phase-inversion process [36]. The ceramic support is a disk that is formed according to the process previously invented in our laboratory [37]. Its role is to ensure the mechanical resistance of the membrane.

The coating solution of the membrane CS-PEG-TIO2 was obtained by dissolving a 1:1 mass mixture of chitosan and PEG in a certain volume of acetic acid (0.1 M) in order to obtain a 2.5% w/v solution. Hence, the mixture was stirred for 12 h. Accordingly, due to acid–base neutralization between acetic acid and abundant amino groups on the structure of CS, the coated layer was transformed into a gelatinous solution according to the following equation [38]:

Next, a quantity of TiO2, equivalent to 20% of the polymer mass, was added to the solution, and the mixture was stirred for an additional 12 h. This allows the homogenization of the mixture and ensures a physical arrangement of TiO2 on the chitosan. At this stage, a white gel was obtained. The formed solution was coated on the support by spin coating at 500 rpm for 30 s.

After placing the solution on the support, a gel layer formed. To solidify it, we first evaporated the solvent at 50 °C for 7 h, and then immersed the membrane in a 2% w/v sodium hydroxide solution for 30 min. Afterward, the membrane was rinsed with water to eliminate the remaining NaOH. At this stage, the membrane formed was dense. To generate the pores, the dense membrane was submerged in water at a bath temperature of 80 °C for a duration of 8 h. This step served to dissolve the PEG component, resulting in the formation of pores [39].

The coating solution for CS-PEG was obtained by dissolving a 1:1 mass mixture of chitosan and PEG. In a certain volume of acetic acid (0.1 M) in order to obtain a 2.5% w/v solution, the solution was coated on the ceramic support. Then, the membrane was subjected to the same treatment as a CS-PEG-TIO2.

For the CS-TiO2 coating solution, a 1:0.2 mass mixture of chitosan and TiO2 was dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid to obtain a 2.5% w/v solution, following a similar process as CS-PEG-TiO2 but omitting the final step.

2.2.1. Water Permeability Measurements

Water permeability measurements were performed to evaluate the membrane’s filtration performance using a dead-end filtration setup, as schematized in Figure 1. The permeability was determined by plotting a Darcy line, which represents the variation in volumetric flow rate as a function of transmembrane pressure . The slope of the line represents the permeability [21].

Figure 1.

Equipment for measuring permeability and performing filtration.

Prior to the test, the membrane was pressurized with distilled water for 30 min for the purpose of stabilizing the flux . Then, the water flux (L m−2 h−1 bar−1, abbreviated as LMH/bar) was calculated through eq. [40]:

where is the volume of the permeate solution during the test time (h) under a differential pressure . is the effective membrane area (m2) for permeation. The test was conducted three times under different pressures , and the resulting flow variations were plotted against the pressure. The water permeability was then determined graphically.

2.2.2. Filtration Performance

The filtration tests were conducted with the same device used for the permeability measurement (Figure 1). The concentration of the dye in the feed solution was 10 mg/L, and the concentration of the dye in the permeate solution was quantified at the corresponding maximum absorption wavelengths using UV–vis spectroscopy (Jasco V-630 UV–Vis Spectrophotometer, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

The rejection rate of the membrane toward dye was calculated by eq. [41]:

where (mg/L) and (mg/L) are dye concentrations in the permeate and feed solutions, respectively.

2.2.3. Fouling and Regeneration

The fouling propensity of the membranes was evaluated by observing the decrease in flux over time during continuous operation. The membrane was exposed to a methylene blue solution (10 mg/L), and the flux was continuously monitored at a constant pressure difference.

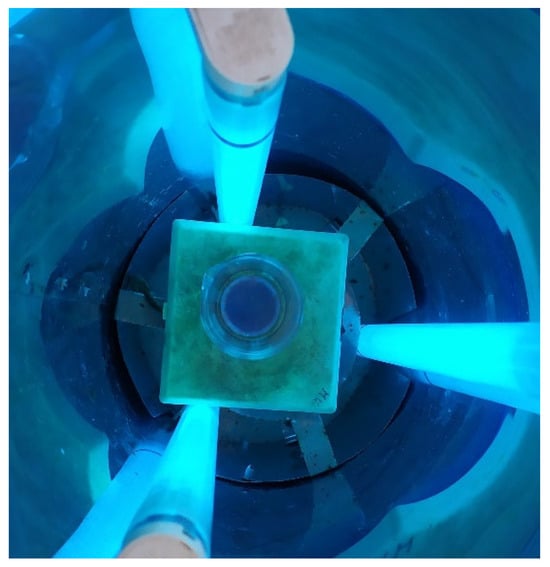

Membrane regeneration was achieved through photocatalytic degradation of the fouling layer. The membrane was immersed in water and exposed to UV light for 12 h (Figure 2). Following regeneration, the membrane was exposed to the methylene blue solution, and the flux was monitored continuously under a constant pressure difference.

Figure 2.

Regeneration of the membrane by UV treatment.

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted to examine the crystalline structure of the membranes, employing a Bruker AXS D8 Advance XRD diffractometer with a Cu-Kα anticathode (λ = 1.54056 Å) and a scanning range from 5 to 70 degrees.

2.3.2. FTIR Analyses

The synthesized membranes and raw materials were characterized using several techniques. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was utilized to analyze the chemical composition and identify any potential interactions between chitosan and TiO2 or PEG by using a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spectra were recorded in the range of 4000 to 650 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

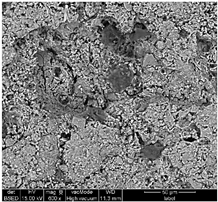

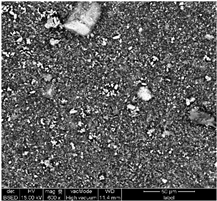

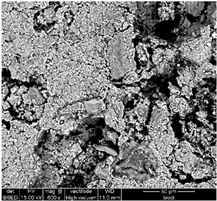

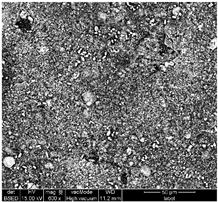

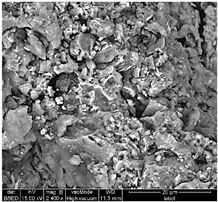

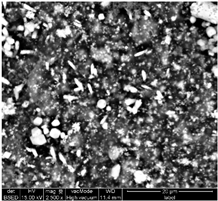

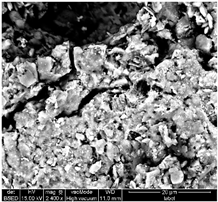

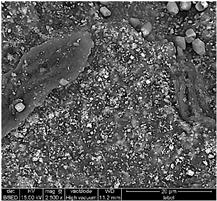

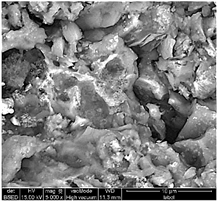

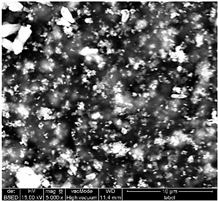

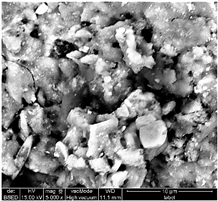

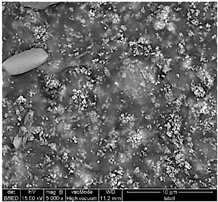

The SEM analyses were performed on four films coated onto the ceramic support, such as pure chitosan film (CS) and the CS-PEG-TiO2 membranes: before filtration (MBF), after filtration (MAF), and after regeneration (MAR). The characterization of the samples by SEM was carried out by using the HIROX SH-5500P scanning electron microscope (HIROX, Oradell, NJ, USA). The analyses were performed under high vacuum with an acceleration voltage of 15 to 20 kV and a working distance of 5 to 6.8 mm [42].

3. Discussion

3.1. Membrane Characterization

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis and Findings

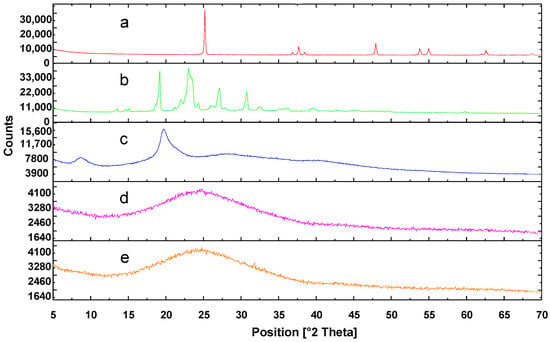

The X-ray powder diffraction patterns of both the pure substances (chitosan, PEG, and TiO2) and the composite films (CS-TiO2 and CS-PEG) are presented in Figure 3. Accordingly, the diffraction patterns of the pure substances exhibit sharp peaks that are characteristic of their crystalline structures. In contrast, the diffraction patterns of the composite films show broadened peaks, indicating an amorphous structure. This observation is attributed to the interaction between chitosan chains in acidic solution. In fact, the movement of chitosan chains is restricted due to intramolecular interactions between the -NH3+ and hydroxyl groups in chitosan [43]. As a result, after the drying process, the chitosan chains do not regain their original structure.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction patterns of (a) TiO2, (b) PEG, (c) CS, (d) CS-PEG, and (e) CS-TiO2.

3.1.2. FTIR Analyses Discussion

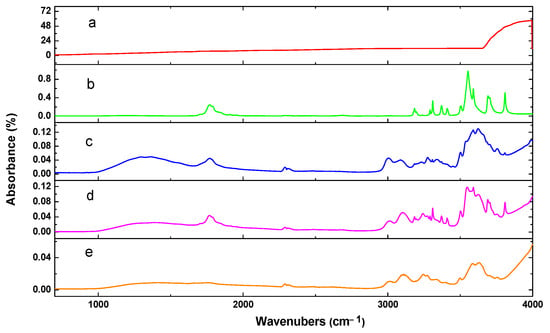

The FTIR spectra of both the pure substances (chitosan, PEG, and TiO2) and the composite films (CS-TiO2 and CS-PEG) are shown in Figure 4. A comparison of the FTIR spectra of the blends with those of the pure substances indicates that no new peaks have emerged, and no existing peaks have disappeared. This observation suggests that no chemical reaction is occurring between chitosan and either PEG or TiO2 [44,45].

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of (a) TiO2, (b) PEG, (c) CS, (d) CS-PEG, and (e) CS-TiO2.

3.1.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy: Analysis and Discussion

Table 1 shows SEM images of the four samples; for each sample, magnifications of 50 µm, 20 µm, and 10 µm were performed. The morphology of the pure chitosan film (CS) resembles that which was previously published in the literature [42,46,47]. The surface presents cavities, pores, and rough textures, indicating the ability to form a porous film from chitosan. Similarly, for the film of chitosan mixed with TiO2 before filtration (MBF), the morphology of this mixture is almost identical to that published in the literature for the application of methylene blue dye degradation [48]. The surface is rough, with the observation of TiO2 particles embedded uniformly in the chitosan polymer. After fouling of the membrane (MAF), the SEM images show a smoother surface with blocked pores, indicating fouling film formation. The smooth morphology of the film suggests that the dye deposition is due to the formation of a cake layer rather than adsorption. In the case of adsorption, the film’s surface would be irregular, displaying agglomerations at specific sites caused by the adsorption of molecules onto active sites [49]. After UV regeneration (MFR), the structure is almost the same as that of MBF before fouling, indicating the degradation of the fouling layer.

Table 1.

SEM analyse of the chitosan film and CS-PEG-TiO2 membrane before and after fouling and after regeneration.

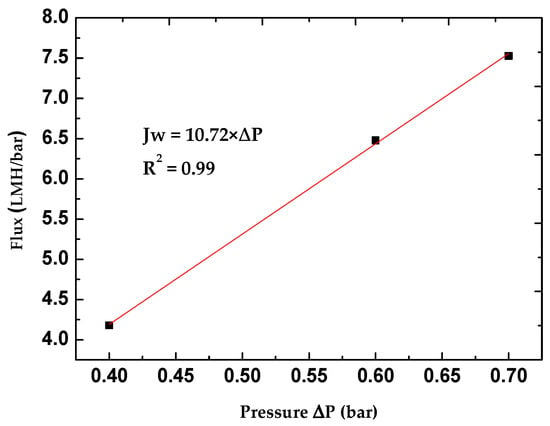

3.1.4. Water Permeability

Through the permeability measurements of several formed membranes, we observed that it is difficult to reproduce membranes with the same permeability value. This is due to several experimental factors, such as the viscosity of the coating solution, the efficiency of porogen removal, etc. These parameters are challenging to control, and optimization remains complex. To ensure the repeatability of the results, we will exclude all permeability values within the interval of 11 ± 2 L/m2·h·bar. The permeability value considered for the membrane will be the average of the measured permeabilities. Therefore, the curve in Figure 5 is generated from points representing the average flux of several membranes, not a single membrane. The pure permeability for the membrane is 10.72 L/m2·h·bar. This value suggests that the membrane falls within the range typically associated with ultrafiltration (UF) or nanofiltration (NF) membranes [50]. The membrane is, therefore, suitable for applications requiring the removal of small organic dyes such as methylene blue from water.

Figure 5.

Variation in water flux as a function of transmembrane pressure.

3.2. Filtration Test

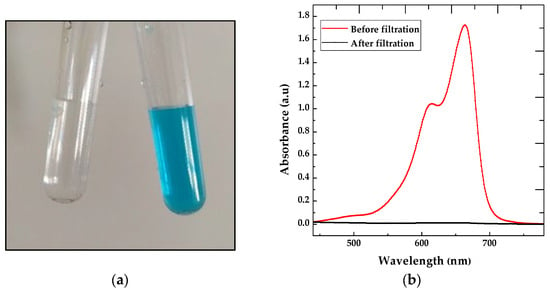

Filtration tests of methylene blue through the CS-PEG-TiO2 membrane demonstrate an excellent removal rate. The observation of the solution’s color before and after filtration shows a complete disappearance of the color (Figure 6a). This result is further confirmed by absorbance measurements, which show the effective removal of BM. In fact, 99.4% of the dye was eliminated after filtration through the CS-PEG-TiO2 membrane (Figure 6b). This high removal rate demonstrates that the membrane is very efficient in eliminating methylene blue, compared to other works such as those of Lyubimenko et al. [51], who achieved a removal rate of 83%, and Kyoung Min Kang et al. [52], who obtained a rate of 99.5%. Similarly, Ahmed H. Ragab et al. [53] reported a removal rate of 98.6%.

Figure 6.

(a) Comparison of the color of the solution before and after filtration, and (b) absorbance measurements of the solution before and after filtration.

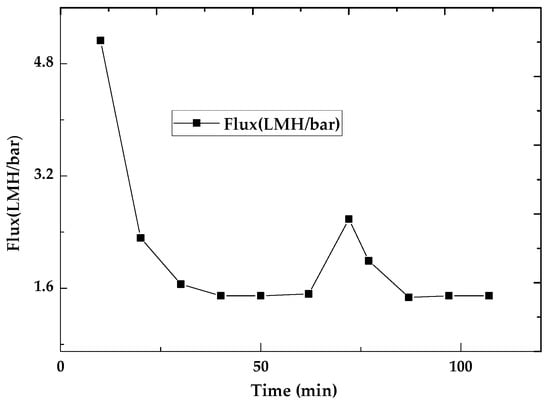

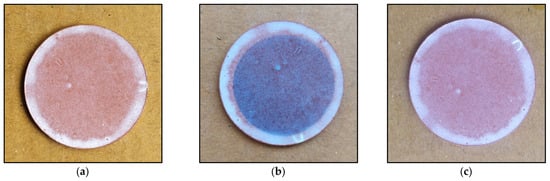

3.3. Fouling and Regeneration

The monitoring of flux variation over time reveals a significant reduction in flux, as shown in Figure 7. This observation is attributed to membrane fouling caused by molecules retained on the membrane’s surface, which obstruct the pores and consequently lead to a decrease in permeation flux. The layer of retained dye is visible to the naked eye, as depicted in Figure 8b.

Figure 7.

Variation in flux over time during the initial use of the membrane and after regeneration.

Figure 8.

Image of the membrane surface: (a) before filtration, (b) after filtration, and (c) after UV regeneration.

Exposing the fouled membrane to UV light leads to the degradation of the fouling layer, restoring the membrane surface to its clean state (Figure 8c). The measurement of flux after UV exposure indicates a significant resurgence (Figure 7), demonstrating the membrane’s self-cleaning capability and its potential for reuse.

The comparison of permeate flux between the membrane’s initial use and its performance after regeneration (Figure 7) shows that the flux does not fully recover to its original value. Specifically, the flux recovers to approximately 50% of its initial value, which is relatively low compared to other self-cleaning membranes. For instance, in the work of Jiaxin Guo et al. [54], a significantly higher flux recovery of 92.2% was observed, suggesting that their membrane system offers better regeneration efficiency. This difference in flux recovery can be attributed to the presence of degraded methylene blue residues, which remain in the form of uncolored compounds. These residues likely remain adsorbed on the chitosan surface or within its pores, leading to a persistent reduction in permeability. It is clear that the regeneration process does not completely eliminate the fouling layer. This suggests that improvements in the regeneration method, such as optimizing the exposure time to UV light, adding cleaning agents, or introducing physical disturbance, may be necessary to achieve a more complete recovery of membrane performance.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully developed a chitosan-TiO2-based photocatalytic membrane for water treatment and tested its ability to remove methylene blue dye through dead-end filtration. The membrane, characterized by its porous structure and high permeability, demonstrated effectiveness in removing methylene blue, achieving a 99.4% removal rate during filtration tests. However, during the filtration process, the membrane exhibited significant fouling. We then tested its ability to self-regenerate under UV exposure, highlighting its potential for reuse. Approximately 50% of the initial flux was restored after regeneration.

Characterization of the membrane using FTIR, XRD, and SEM techniques confirmed the formation of an amorphous composite structure, with TiO2 uniformly distributed within the chitosan matrix, without any chemical interaction between them. The water permeability measurements indicated that the membrane falls within the ultrafiltration or nanofiltration range, making it suitable for applications that require the removal of small organic contaminants, such as methylene blue.

This study also highlighted the challenges associated with membrane fouling and the limitations of the current regeneration process. Despite partial flux recovery, the fouling layer was not completely removed, suggesting that further improvements in the regeneration method—such as optimizing UV exposure time, adding cleaning agents, or introducing physical disturbance—are necessary for more effective recovery of membrane performance.

Future research will focus on the continuous application of this photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) for water treatment, aiming to enhance its efficiency by using cross-flow filtration and integrating simultaneous filtration and regeneration processes. This approach will improve the membrane’s longevity and performance, offering a promising solution for sustainable water treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E.-n.; methodology, A.A.; validation, A.A. and H.N.; formal analysis, H.E.-n., B.H., M.B. (Meryem Bensemlali) and N.L.; resources, M.B. (Mina Bakasse), N.Z., N.J.-R. and S.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.E.-n. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.A. and H.N.; project administration, N.Z., N.J.-R. and S.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, W.; Ngo, H.-H.; Li, J. A mini-review on membrane fouling. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 122, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obotey Ezugbe, E..; Rathilal, S. Membrane Technologies in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.P.; Godhaniya, M.; Kothari, C. Emerging and advanced membrane technology for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffarimiandoab, F.; Gul, B.Y.; Tasdemir, R.S.; Ilter, S.E.; Unal, S.; Tunaboylu, B.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Koyuncu, I. A review on membrane fouling: Membrane modification. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 216, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, A.; Hruza, J.; Yalcinkaya, F. Fouling and Chemical Cleaning of Microfiltration Membranes: A Mini-Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, S. Fouling and cleaning of membrane—A literature review. J. Environ. Sci. 2000, 12, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gokulakrishnan, S.; Arthanareeswaran, G.; László, Z.; Veréb, G.; Kertész, S.; Kweon, J. Recent development of photocatalytic nanomaterials in mixed matrix membrane for emerging pollutants and fouling control, membrane cleaning process. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mane, A.U.; Yang, X.; Xia, Z.; Barry, E.F.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Elam, J.W.; Darling, S.B. Visible-Light-Activated Photocatalytic Films Toward Self-Cleaning Membranes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y. A novel paradigm of photocatalytic cleaning for membrane fouling removal. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 641, 119859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, C.; He, A.; Yang, S.; Wu, G.; Darling, S.B.; Xu, Z. Photocatalytic Nanofiltration Membranes with Self-Cleaning Property for Wastewater Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenderich, K.; Mul, G. Methods, Mechanism, and Applications of Photodeposition in Photocatalysis: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14587–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koe, W.S.; Lee, J.W.; Chong, W.C.; Pang, Y.L.; Sim, L.C. An overview of photocatalytic degradation: Photocatalysts, mechanisms, and development of photocatalytic membrane. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2522–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, R.R.; Gracia, F.; Stephen, A. Basic Principles, Mechanism, and Challenges of Photocatalysis. In Nanocomposites for Visible Light-Induced Photocatalysis; Springer Series on Polymer and Composite Materials; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shen, Z.-P.; Shi, L.; Cheng, R.; Yuan, D.-H. Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors (PMRs) in Water Treatment: Configurations and Influencing Factors. Catalysts 2017, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozia, S. Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) in water and wastewater treatment. A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 73, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ding, L.; Luo, J.; Jaffrin, M.Y.; Tang, B. Membrane fouling in photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) for water and wastewater treatment: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Yang, X.; Feng, Q.; Shi, S.; Deng, B.; Zhang, L. Biodegradable Chitosan-Based Membranes for Highly Effective Separation of Emulsified Oil/Water. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2022, 39, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedula, S.S.; Yadav, G.D. Chitosan-based membranes preparation and applications: Challenges and opportunities. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Balushi, K.S.A.; Devi, G.; Al Hudaifi, A.S.; Al Garibi, A.S.R.K. Development of chitosan-TiO2 thin film and its application for methylene blue dye degradation. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 103, 6062–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardouri, S.; Sghaier, J. Adsorptive removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using different agricultural wastes as adsorbents. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafatullah, M.; Sulaiman, O.; Hashim, R.; Ahmad, A. Adsorption of methylene blue on low-cost adsorbents: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.; Ahmad, A.; Hameed, B. Adsorption of basic dye on high-surface-area activated carbon prepared from coconut husk: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Bhattacharyya, K.G. Adsorption of methylene blue on kaolinite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2002, 20, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.; Ahmad, A.; Hameed, B. Adsorption of basic dye using activated carbon prepared from oil palm shell: Batch and fixed bed studies. Desalination 2008, 225, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zourif, A.; Benbiyi, A.; Kouniba, S.; EL Guendouzi, M. Valorization of walnut husks as a natural coagulant for optimized water decolorization. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, A.; Chikhi, M.; Balaska, F.; Seraghni, W.; Boussemghoune, M.; Dizge, N. Electrocoagulation employing recycled aluminum electrodes for methylene blue remediation. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S. Methods of Dye Removal from Dye House Effluent—An Overview. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2008, 25, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, V.K.; Kumar, D.; Gupta, A.; Neelratan, P.P.; Purohit, L.P.; Singh, A.; Singh, V.; Lee, S.; Mishra, Y.K.; Kaushik, A.; et al. Nanocarbons Decorated TiO2 as Advanced Nanocomposite Fabric for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye and Ciprofloxacin. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 148, 111435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, V.; Vikrant, K.; Goswami, M.; Tiwari, H.; Sonwani, R.K.; Lee, J.; Tsang, D.C.; Kim, K.-H.; Saeed, M.; Kumar, S.; et al. Biodegradation of methylene blue dye in a batch and continuous mode using biochar as packing media. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.; Kalsoom, U.; Ahsan, Z.; Bilal, M. Non-magnetic and magnetically responsive support materials immobilized peroxidases for biocatalytic degradation of emerging dye pollutants—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, A.; Meryem, B.; Badreddine, H.; Chajri, F.Z.; Meryeme, J.; Abdellatif, A.; Najoua, L.; Bakasse, M.; Nasrellah, H. Removal of Methylene Blue by Low-Cost Adsorbent Prepared from Jujube Stones: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024, 25, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.J.; Duff, S.J. Coagulation and precipitation of a mechanical pulping effluent—I. Removal of carbon, colour and turbidity. Water Res. 1996, 30, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchley, J. Ozone for Dye Waste Color Removal: Four Years Operation at Leek STW. Ozone: Sci. Eng. 1998, 20, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchou, F.E.; Akbour, R.A.; Assabbane, A.; Hamdani, M. Removal of cationic dye from aqueous solution using Moroccan pozzolana as adsorbent: Isotherms, kinetic studies, and application on real textile wastewater treatment. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, H.R.; Sulaiman, N.M.N.; Hashim, N.A.; Hassan, C.R.C.; Ramli, M.R. Synthetic reactive dye wastewater treatment by using nano-membrane filtration. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 55, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybek, P.; Jakubski, Ł.; Dudek, G. Neat Chitosan Porous Materials: A Review of Preparation, Structure Characterization and Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatimi, B.; Mouldar, J.; Loudiki, A.; Hafdi, H.; Joudi, M.; Daoudi, E.; Nasrellah, H.; Lançar, I.-T.; El Mhammedi, M.; Bakasse, M. Low cost pyrrhotite ash/clay-based inorganic membrane for industrial wastewaters treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M.; Pavlov, G.; Desbrières, J. Influence of acetic acid concentration on the solubilization of chitosan. Polymer 1999, 40, 7029–7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Fang, Z.; Xu, C. Novel method of preparing microporous membrane by selective dissolution of chitosan/polyethylene glycol blend membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 91, 2840–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatimi, B.; Bensemlali, M.; Hafdi, H.; Mouldar, J.; Loudiki, A.; Joudi, M.; Aarfane, A.; Nasrellah, H.; El Mhammedi, M.A.; Bakasse, M. Hematite based ultrafiltration membrane prepared from pyrrhotite ash waste for textile wastewater treatment. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 98, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatimi, B.; Nasrellah, H.; Yassine, I.; Joudi, M.; El Mhammedi, M.; Lançar, I.-T.; Bakasse, M. Low cost MF ceramic support prepared from natural phosphate and titania: Application for the filtration of Disperse Blue 79 azo dye solution. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 136, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, V.; Olafadehan, O. Comparative investigation of RSM and ANN for multi-response modeling and optimization studies of derived chitosan from Archachatina marginata shell. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 3869–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Brahmakumar, M.; Abraham, T.E. Microstructural imaging and characterization of the mechanical, chemical, thermal, and swelling properties of starch–chitosan blend films. Biopolymers 2006, 82, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.-H.; Xue, R.; Yang, D.-B.; Liu, Y.; Song, R. Effects of blending chitosan with peg on surface morphology, crystallization and thermal properties. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2009, 27, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orojlou, S.H.; Rastegarzadeh, S.; Zargar, B. Experimental and modeling analyses of COD removal from industrial wastewater using the TiO2–chitosan nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, G.L.; Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Moura, J.M.; Cadaval, T.R.S.; Pinto, L.A.A. Adsorption rate of Reactive Black 5 on chitosan based materials: Geometry and swelling effects. Adsorption 2016, 22, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norranattrakul, P.; Siralertmukul, K.; Nuisin, R. Fabrication of chitosan/titanium dioxide composites film for the photocatalytic degradation of dye. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2013, 23, 2. Available online: https://jmmm.material.chula.ac.th/index.php/jmmm/article/view/59 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Ragab, A.H.; Gumaah, N.F.; El Aziz Elfiky, A.A.; Mubarak, M.F. Exploring the Sustainable Elimination of Dye Using Cellulose Nanofibrils-Vinyl Resin Based Nanofiltration Membranes. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, N.K.; Chinh, H.D.; Hong, P.T.T.; Huy, T.Q. Facile Preparation of Chitosan Films for High Performance Removal of Reactive Blue 19 Dye from Aqueous Solution. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyati, S.; Muchtar, S.; Yusuf, M.; Arahman, N.; Sofyana, S.; Rosnelly, C.M.; Fathanah, U.; Takagi, R.; Matsuyama, H.; Shamsuddin, N.; et al. Production of High Flux Poly(Ether Sulfone) Membrane Using Silica Additive Extracted from Natural Resource. Membranes 2020, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubimenko, R.; Busko, D.; Richards, B.S.; Schäfer, A.I.; Turshatov, A. Efficient Photocatalytic Removal of Methylene Blue Using a Metalloporphyrin–Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Hybrid Membrane in a Flow-Through Reactor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 31763–31776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.M.; Kim, D.W.; Ren, C.E.; Cho, K.M.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, J.H.; Nam, Y.T.; Gogotsi, Y.; Jung, H.-T. Selective Molecular Separation on Ti3C2Tx–Graphene Oxide Membranes during Pressure-Driven Filtration: Comparison with Graphene Oxide and MXenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 44687–44694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.H.; Gumaah, N.F.; Elfiky, A.A.E.A.; Mubarak, M.F. Exploring the sustainable elimination of dye using cellulose nanofibrils- vinyl resin based nanofiltration membranes. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yan, D.Y.; Lam, F.L.-Y.; Deka, B.J.; Lv, X.; Ng, Y.H.; An, A.K. Self-cleaning BiOBr/Ag photocatalytic membrane for membrane regeneration under visible light in membrane distillation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.