Abstract

This study investigates rim seal flow in axial turbine configurations through a combined experimental–numerical approach, with the objective of identifying sealing-flow conditions that minimize ingestion while limiting aerodynamic losses. Experimental measurements from the University of BATH are used to validate computational methodology, ensuring consistency with established sealing-effectiveness trends. The work places particular emphasis on the influence of computational domain selection and interface treatment, which is shown to strongly affect the prediction of ingestion mechanisms. A key contribution of this study is the systematic assessment of multiple domain configurations, demonstrating that a frozen rotor MRF formulation provides the most reliable steady-state representation of pressure-driven ingress, whereas stationary and non-interface domains tend to overpredict sealing effectiveness. A simplified thin-seal model is also evaluated and found to offer an efficient alternative for global performance predictions. Furthermore, a statistical orifice-based model is introduced to estimate minimum sealing flow for different rim seal geometries, providing a practical engineering tool for purge-flow scaling. The effects of pre-swirl injection are examined and shown to substantially reduce rotor wall shear and moment coefficient, contributing to lower windage losses without significantly modifying sealing characteristics. Unsteady flow features are explored using a harmonic balance method, revealing Kelvin–Helmholtz-type instabilities that drive large-scale structures within the rim seal cavity, particularly near design-speed operation. Finally, results highlight a clear trade-off between sealing-flow rate and turbine isentropic efficiency, underlining the importance of optimized purge-flow management.

1. Introduction

The efficiency of a turbine is measured by its aerodynamic performance, which compares the actual work generated to theoretical calculation. Adiabatic efficiency is the most common definition of efficiency for turbines, determined by comparing the actual work of the turbine to the theoretical isentropic work. When high-enthalpy fluid enters the turbine, it is converted into shaft power due to expansion and accelerated flow. The stage degree of reaction measures the ratio of the static enthalpy drop in the rotor to the enthalpy drop in the entire stage. The degree of reaction splits the rotor into two types: the reaction turbine, where the degree of reaction is 1, and the impulse turbine where the degree of reaction is 0. The main difference between these two types of turbines is the pressure field across the stage. For the impulse turbine, the static pressure remains unchanged, while the reaction turbine uses the pressure drop to create a reaction force. Adiabatic efficiency and degree of reaction determine the turbine’s configuration.

The losses in a turbine can be explained by the generation of entropy during the process. This can result from an increase in entropy of the fluid or the waste of energy. Denton [1] identified two aerodynamic processes that lead to entropy generation: viscous friction in the boundary layers or free shear layers, and the mixing process of fluids, such as coolant flow. Heat transfer problems between different temperatures, such as the mainstream flow and coolant flow, also contribute to the loss. In turbines, viscous effect and non-equilibrium processes play a major role in entropy generation. Cavity flow to the mainstream passage is a specialty in this study, but leakage loss [2] and secondary or end-wall losses [3,4,5,6] are among the major losses in the turbine stage. These losses are caused by complex three-dimensional flow phenomena resulting from rapid mixing between fluids. The thickness of the inlet boundary layer [7,8] and the turning of the blade are also important factors that lead to end-wall loss. Using the numerical method, Dawes [9] stated that 90% of entropy generation occurs within the edge of the logarithmic zone (y+ ~30), where the velocity and temperature gradients are greatest. Dawes also noted that the passage vortex draws fluid from the boundary layer and mixes with the mainstream flow, making the downstream boundary layer thinner. Moreover, the secondary vortex attaches to the suction surface, creating high shear stress and high turbulent intensity across the blade. As a result, the local region above the trailing edge end-wall exhibits a very high entropy fluid. The turbine is cooled by coolant fluid that bleeds from the compressor. Denton [1] stated that the entry of the cooling fluid removes heat from the system, decreasing the entropy and enhancing the turbine stage’s efficiency. However, the mixing process between the coolant and mainstream fluids causes an irreversible entropy-increased effect in the local region. According to Shapiro [10], mixing losses depend on the stagnation pressure, temperature, mass flow rate, and the angle between two fluid streams. The worst case is when cosine is equal to 0 (90 degrees), creating the most mixing between the two fluid streams, leading to maximum missing losses. With the injection of cooling fluid, the blockage effect will enhance the end-wall losses by obstructing the flow in the mainstream [11]. As the turbine disk rotates in a stationary fluid, the centrifugal force creates a radial flow, which is offset by an axial flow [12,13,14]. With the turbine stationary and the fluid rotating, the back pressure gradient pushes the fluid toward the center [15]. The combination of a stationary and rotating disk creates a wheel space cavity with fluid movement [16,17]. The flow structure inside the wheel space of the rotor–stator system is dependent on the geometry of the gap [18,19,20] and rotational Reynolds number (Reϕ) [21]. Despite their significant contribution to losses, end-wall losses have not been fully described from a physical point of view and still depend on empirical performance.

In the context of gas turbine engineering, two major phenomena induce the penetration of hot gases into the cavities: the rotationally induced ingress (RI) is caused by the motion of the rotor disk, and externally induced ingress (EI) is caused by the non-axisymmetric flow structure in the mainstream. Studies [21,22,23,24] emphasize the roles of pressure, rim seal geometry, and the rotational Reynolds number, and provide experimental and modeling methods for evaluating and controlling the rotationally induced ingress. Experiments showed that minimum sealing flow is influenced by geometry and Reynolds number [22], with radial seals being more effective than axial seals [23]. Unlike rotational ingress, the externally induced ingress does not depend much on the rotational Reynolds number. An experiment conducted in [25] showed that ingression can be influenced by disturbance of the annulus. The importance of pressure gradients in the anulus, which can dominate the rotational Reynolds number, was highlighted. Phadke and Owen [26,27] upgraded their previous experimental rig to simulate the non-asymmetric pressure in the mainstream annulus. Both types of ingressions were observed and separated into two regimes, and the correlation between the two are expressed by the ratio of the mainstream Reynolds number and the rotational Reynolds number. They also presented an empirical model to calculate the minimum flow rate required for sealing, emphasizing the role of pressure in the EI phenomenon. The influence of mainstream flow disturbances and blade geometry on EI have been investigated in studies [28,29,30,31,32]. The study [29] measured rotationally induced ingress in turbine rim seals and related sealing effectiveness to predictions from an orifice model. Their findings emphasized that rotation-driven and combined ingress become crucial when pressure asymmetry is reduced, such as in double-seal systems. The presence of blades increased the circumference pressure distribution downstream of the vanes. The sealing effectiveness across the radial direction of the stator wall was also measured. Both CFD and experimental results agreed that the ingression zone at the rim seal gaps moves at half the speed of the rotor. Dieter Bohn et al. [32] experimentally and numerically investigated the influence of rotor blades on hot gas ingestion in an axial turbine stage with two rim seal geometries. They showed that rotor blades can either reduce or enhance sealing effectiveness depending on the rim seal design, and identified a rotating local ingestion zone at about half the rotor speed. Most recently, Sangan et al. [33,34] at the University of BATH conducted a single-stage turbine that can operate to a rotational Reynolds number of nearly 1 million. A total of 32 stator vanes were formed and an NACA aero foil was used as a rotor blade; this was combined with concentration measurement and a pressure tap to determine the sealing effectiveness and pressure distribution at the mainstream flow. The author also introduces a new non-dimension parameter that includes the geometry of the rim seal, the sealant rate, and the rotation speed. This new parameter is especially helpful for scaling the flow from the test rig to the real engine condition [35] by developing a theoretical function that will be discussed under. And most importantly, this study will be using the stator vane model drive from this experiment. In summary, the rotationally induced ingress (RI) is the resultant of the rotor–stator system. With fully sealed cavities, the rotating core was suppressed. The pressure-driven ingress (EI) prevails over the counterpart in most gas turbines engines, as a result of the unsteady flow behind the structure of the mainstream causing the pressure to be quasi-axisymmetric. Filippo Merli et al. [36] presented an experimental investigation of the aerodynamic and sealing performance of the downstream hub rim seal in a high-pressure turbine using an engine-representative two-stage ring. By varying purge flow and vane/trut clocking, and combining pressure, tracer gas, unsteady measurements, and oil-flow visualization, the authors show that the wheel space can be fully protected from hot-gas ingress with a sealing flow parameter of about Φ0,min ≈ 0.068, close to the design purge level. The study [37] shows that when purge mass flow is raised above about 1%, reversing the purge direction relative to the main flow (AS, ASDS) can greatly enhance end-wall film cooling, while only slightly affecting aerodynamic losses, and that a double-tooth seal with co-flow purge (DS) is not beneficial and can even reduce film cooling effectiveness. The study [38] employs 3D URANS simulations on a stator–rotor model to investigate four rim seal geometric structures (single-axial, single-radial, radial–axial, and double-radial) at various purge flow rates. The results show that the single-radial configuration significantly improves hot-gas sealing compared with the single-axial design, while a double-layer configuration (radial–axial and double-radial) further enhances sealing effectiveness, each providing advantages in different radial regions. The experimental measurements and URANS simulations of a three-stage turbine used to investigate the effect of different stator–rotor axial gaps on aerothermal performance and unsteady flow were also conducted in the study [39]. The results indicate that reducing the axial gap improves overall turbine efficiency by around 1% through lower entropy generation between the stator inlet and rotor inlet, while also modifying wake interaction and pressure fluctuations between rows, with downstream rotor pressure fluctuations significantly larger than those on upstream stators. Nketia et al. [40] performed wall-resolved large eddy simulations of a rotor–stator system with an axial rim seal (no vanes or blades) to isolate the rotationally induced ingress and egress of hot gas in a gas turbine. The LES, validated against experiments, reveals that Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities in the rotor-side shear layer and vortex shedding from the backward-facing step of the seal generate statistically stationary regions of high and low pressure that drive ingress, while additional vortex shedding and recirculation in the seal clearance promote ingress by entrainment.

For a wide range of experiments and CFD studies on the phenomena of the rim seal over the years, numerous studies have found the instability that occurs at a frequency unrelated to the rotor speed as another key driver of ingression. Teuber et al. [35] investigated the wheel space within a rotating frame of reference using the BATH rig model, conducting both steady and unsteady computations. They found that the multi-reference frame (MRF) method significantly influenced ingression prediction, providing more reliable sealing characteristics than unsteady RANS, while rotor blades had negligible impact on stator-side pressure. Mirza Moghadam et al. [41] studied steady RANS with a full-stage turbine, submerging the cavity in the stationary domain to eliminate rotor blade interaction via a mixing plane interface. They observed seal mixing efficiency and noted that the stator hub filet improved its sealing effectiveness, with stator wake exerting more influence on ingression than rotor wake. Liu et al. [42] compared multiple domain studies on the BATH test rig and reported discrepancies between RANS and URANS, with bladeless RANS overpredicting peak pressures and failing near rim seal gaps due to high unsteadiness. They recommended optimizing the MRF interface location to better capture mainstream swirl. RANS failed to accurately predict flow near rim seal gaps due to high unsteadiness. Sealing effectiveness predictions were poor in both wheel space domains, though the non-inertia frame wheel space yielded better agreement with experimental data. Authors suggested investigating MRF interface location for optimal mainstream swirl. Rotor blades in URANS had little influence on upstream flow compared to test rig purposes. Rabs et al. [43] examined rim seal flow instabilities based on free shear flow phenomena. They described Helmholtz instabilities arising from velocity differences in parallel flows, causing vortices that disrupt flow dynamics near rim seal gaps and potentially affect ingress and mainstream flow mixing. These instabilities form a traveling wave within the rim seal gap, influencing sealing flow rate and the interaction between vanes and blades. Beard et al. [44] conducted experiments on a wheel space-only rig operating at higher rotational speeds, observing less large-scale structure and increased sealing flow, with structure velocity remaining constant around 80%. Gao et al. [45] used large-eddy simulation (LES) for the same rig, finding significantly more large-scale structures than experimental data, moving at 43% of rotor speed. They observed a gap recirculating zone (GRZ) vortex structure, suggesting another mode of instabilities that disappeared at high sealing flow rates. Furthermore, Gao et al. [46] observed Taylor–Couette vortex instabilities in chute seals, with recirculation disappearing at high sealing flow rates. They noted high vorticity at stator or rotor walls, indicating Taylor vortex presence and its potential impact on seal configuration. Through LES investigation, Gao et al. [47] confirmed the presence of inertial waves, showing velocity fluctuations in phase with each other but out of phase with the pressure field, satisfying the momentum equation. They concluded that ingress and egression interference through rim seal gaps complicates flow prediction, marking a new understanding of rim seal flow structure. In summary, MRF provides the most reliable steady-state predictions, while URANS sensitivity depends on domain passage count. LES captures large-scale vortical mechanisms (Kelvin–Helmholtz, Taylor–Couette, inertial waves) as dominant drivers of sealing flow fluctuations within the rim seal gap.

For CFD applications, the influence of computational domain plays a significant role in the measurement of ingression and sealing effectiveness. While RANS adoption shows fast and reliable computation, the rim seal phenomenon is still unable to give real insight into the already unsteady flow structure. Unsteady simulations give insight into the flow field but are usually found to be computationally expensive. The reduction in computational domain might give different large-scale structures. In the scope of this study, the harmonic balance method based on frequency domain is adopted to have a first understanding of the unsteady rim seal flow.

2. Geometry

2.1. Description of LISA Geometry

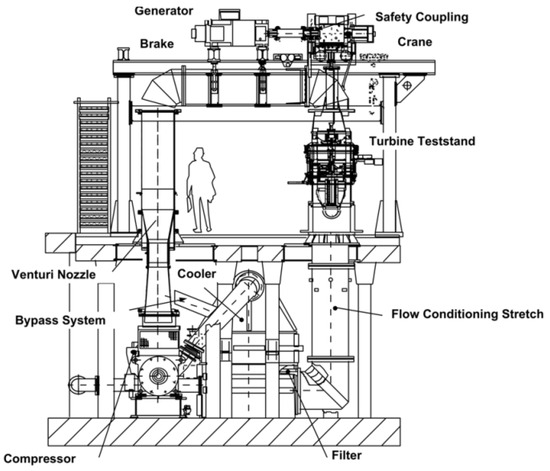

One of the turbine test facilities, “LISA”, at the Turbomachinery Laboratory of ETH Zurich, built by Behr [2] is an axial flow, low-temperature, subsonic, staggered turbine. As illustrated in Figure 1, the turbine test rig is designed to operate in a loop that opens to the ambient atmosphere. A radial compressor of 750 kW electrical power situated in the basement provides air to the system. It is constructed with two stators and one rotor with an addiction stator at the inlet and outlet to straight out the flow, making it a 1.5-stage turbine. The maximum limits of the turbine include the expansion ratio of 1.5 and a mass flow rate of 13 kg/s, creating it a high-pressure turbine. Although it is a testing rig far from a realistic gas turbine, LISA has an excellent reputation for the illustration of the turbine phenomenon. Providing a wide range of experiment data, the LISA turbine is best-suited for simulating turbine flow behavior. In this study, to investigate the influence of the rim seal cooling flow, a one-stage LISA adapted from the 1.5-stage version is used. A summary of the main parameters defining the operating range of the LISA turbine test rig is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

LISA turbine’s test section facility [2].

Table 1.

Main parameter of the LISA research turbine facility [2].

2.2. Review of BATH Cavity Experimental Rig

This study uses data from Sangan [34] at the mechanical engineering department of the University of BATH to provide public data on the experiment rig. The domain consists of 560 stationery, non-staggered, turning vanes and 32 NACA 0018 rotor blades. Concentration measurements inside the wheel space are used to calculate sealing effectiveness. The static pressure tap is located at stator wall along with pitot tubes. The rim seal geometry in this thesis is based on the rim seal geometry of the BATH test rig, with the configurations denoted Gen#1, Gen#2, and Gen#4 being considered. The BATH test rig is designed to rotate at a maximum speed of 4000 RPM, with the publication data available for 2000, 3000, and 3500 RPM. In this study, only the 3500 RPM case is used.

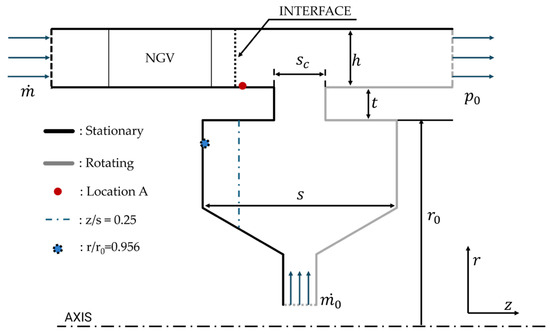

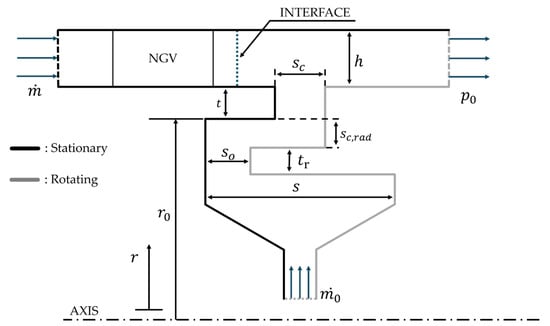

Figure 2 is a meridional view sketch of the Gen #1 computational domain used, with the annulus pressure measurement located at Point A, which is positioned 2 mm upstream from the rim seal edge. The main data for sealing effectiveness measurement are located at non-dimensional radius r/ro = 0.958. Other miscellaneous fluid property reference measurements (e.g., density, viscosity) are taken at r/ro = 0.993. The pitot tube for swirling flow measurements is located at the non-dimensional axial wheel space location of z/s = 0.25 (zero for the stator and one for the rotor).

Figure 2.

Sketch of axial seal and data measurement locations.

In the experiments, the test rig uses ambient air under laboratory conditions with a flow temperature of 250 °C, passing through a Venturi tube at the inlet to measure mass flow rate. The outlet flows to a volute and is dumped into ambient atmosphere. To demonstrate numerical simulations, inlet mass flow rate and pressure outlet with 5% turbulence intensity are applied as boundary conditions. Moreover, the sealing flow inlet in the experiment does not contain a pre-swirl nozzle for adding rotation speed to the fluid. Therefore, the simulations in this study allow the investigation of both pre-swirl and non-pre-swirl cases. The pre-swirl helps the sealing flow match the spinning boundary layer on the rotor more effectively.

3. Numerical Method

3.1. Numerical and Harmonic Balance Approach

In this study, ANSYS CFX 2024 R2 was employed to solve the governing differential equations, including the continuity, Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS), and energy equations. CFX utilizes the finite volume method, which is based on an underlying finite element mesh. The spatial domain is first discretized into a mesh, from which finite volumes are constructed. Conservation laws for mass, momentum, and energy are then applied to each finite control volume to perform the calculations. The Shear Stress Transport model, based on the Menter [48]. k−ω turbulence model, is used in the validation process as it previously proved that it gave the best result [49,50]. The convergence criteria are established such that the root mean square values for continuity, momentum, energy, turbulent kinetic energy, and specific turbulent dissipation rate are all below 1 × 10−4. Additionally, to ensure that the results of interested parameters are monitored to achieve convergence, the multi-reference frame (MRF) method is also used in this study to simulate the rotational blades. The “rotation domain” or the no-inertia domain adds the tangential velocity directly to the source term of the momentum equation. The changing interface is incorporated in both stage (mixing-plane) and frozen rotor to evaluate the influence of the interface. For reduced computational resource, the size of the domain only incorporates a single passage, connected circumferentially by the rotational periodicity with GGI interface. To accommodate the tracer gas in the simulation, a passive-scalar is used to represent the transportation of the multi-gasses’ domain. An active scalar is an actual gas that has all the molecular properties and reacts with regular air in the domain. In contrast, the passive scalar is used just for modeling the transport equation and is not heavily involved in the main fluid flow physics. This simplifies the computational resources but still gives an accurate result for a tracer gas. To portrait as close as possible to the experiment, the kinematic diffusive coefficient (m2/s) is set for CO2 in the passive scalar. The diffusive coefficient represents how the fluids expanded in the space correlated with temperature, and this coefficient can be obtained from the experiment or using Chapman–Enskog’s theory with 8% error. For this study, a small range of temperature is used so it benefits from using the experimental results. In every turbomachinery, it involves a couple of vanes and blades, exhibiting both spatial and temporal periodic in turbomachinery, and harmonic oscillations based on the fundamental frequency of the blade-passing frequency (BPF) or the rotor rotation speed. This behavior leads to the adoption of a frequency-domain approach in addressing the problem. The harmonic balance method based on the frequency domain is adopted in this study to address the unsteady flow of the rim seal. In the harmonic balance method, the governing Navier–Stokes equations are transformed using a Fourier series in time, while incorporating coefficients that vary spatially. This method solves multiple steady-state solutions at difference blade angles (time planes) to archive the Fourier series for the unsteady behavior of the flow field. The harmonic balance method will be applied to the BATH test rig case in this study.

3.2. Computational Domain and Theoretical Basis

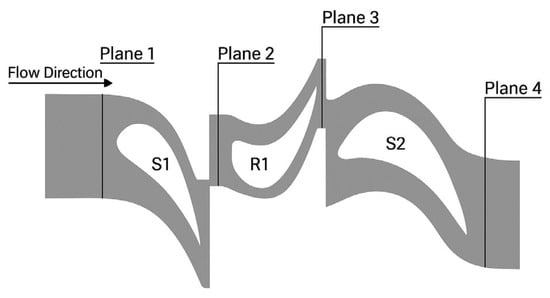

3.2.1. LISA 1.5 Stage Turbine

The computational domain is based on Behr experimental rig, with 36 stator vanes for S1 and S2 (stator 1 and stator 2) and 54 blades (R1) shows on the Table 2. As shown in Figure 3, the inner hub has a radius of 330 mm, and the outer shroud is 400 mm. Since the tip geometry is not provided, the tip clearance is set to 1% of the blade span, matching the test rig configuration. Only one passage is considered, and the side surface is set as a rotational periodicity interface type, with the mesh connection method selected as the “GGI” method. The geometry of the blades and vanes including the computational domain is constructed in CATIA and imported to the meshing application. It is important to note that although the experiment is a 1.5-stage turbine, only a one-stage turbine is used in this study, which simplifies the computational process while maintaining the quality and accuracy of the result. That is why the author of this study calculates the problem a little bit explicitly here. An accessor to Chung [50]’s previous data on the LISA 1.5 stage used nearly the same equal amount of mesh and the same domain to achieve the flow field solution. Then, the result output was used as the boundary conditions for the one-stage turbine. This approach greatly reduces computational resources but still results in great quality and quantity; the result will be discussed in the next section.

Table 2.

Measurement plane and position.

Figure 3.

Top view of measured plane for the 1.5-stage LISA.

One thing to note for the domain considerations is the traverse plane that is used to measure experiments. Illustrated in Figure 3, the measured plane for 1.5 stage LISA shows the position of the interface located at the traverse plane for easier measurement, and the numbering of the plane is convenient for the calculation formular subscript. However, for the rim seal add-in configuration, and the traverse plane used for measurement is located between the vanes’ leading edge and the blades’, just above the rim seal clearance. However, this placement makes it impossible to place the interface above. To resolve this, the domain interface is moved upstream by 2 mm, allowing the wheel space to be submerged inside the rotating domain. The inlet is moved upstream twice the axial chord length of S1 to ensure a fully developed flow, while the outlet is moved downstream twice the axial chord length of S2 to avoid error in the outlet boundary conditions (Table 2).

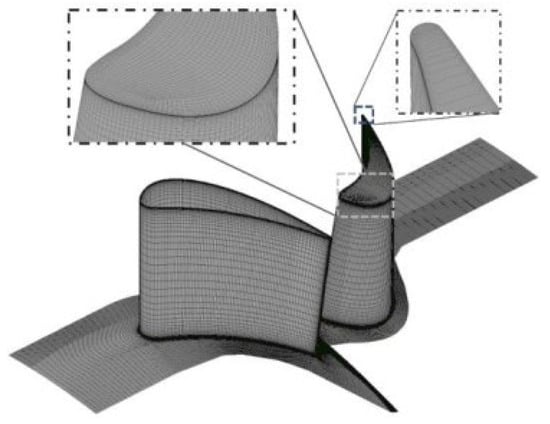

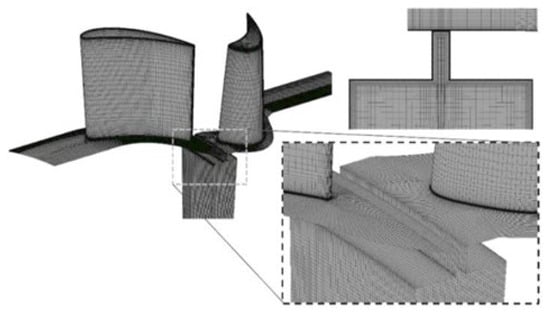

The domain is discretized (meshed) for both the 1.5-stage turbine and the 1-stage (Figure 4 and Figure 5) configuration. The mesh using here is a structured grid, hexahedral-shaped mesh, with the mesh number of the 1.5 stage already calculated and refined to about 6.0 million mesh; and for the one stage, the three meshes varying from 9.5 hundred thousand to 5.7 million will be considered for the numerical derivative. The mesh elements adjacent to the rotor and rim seal walls are specified with a height of 3 × 10−6 m to accurately resolve the boundary layers within the viscous sublayer region. This setup uses the k-ω SST turbulence model combined with the Kato–Launder limiter.

Figure 4.

1-stage LISA vane and blade mesh structure studies above.

Figure 5.

1-stage LISA with axial seal geometry, including the meridional plane mesh of the rim seal.

For validation purposes, the reliability of the numerical method and the result from CFD will be compared with the experiment test rig through non-dimensional fluid dynamics variables commonly seen in turbomachinery.

The total-to-total efficiency of the turbine with a fitted rim seal, adapted from [51]:

This new equation is considered the addition of rim seal flow total enthalpy into the expansion cycle. The added variable here is the total pressure measured at the inner cavities pt,cav. In the experiment conducted by [52]) at ETH, static pressure within the cavities was measured at the stator wall, well away from the rim seal clearance. Meanwhile, velocity through the rim seal gap was measured in the drum beneath the wheel space, close to the inner seal. Thus, in a different rim seal geometry, the place to measure the pressure might be arbitrary. However, in a later modified experimental test rig at ETH [52], the measurement probe was able to be positioned deep into the rim seal gap to show a better output. In conclusion, it is most effective to measure pressure at the inner rim seal or near the disk radius’s end, where the flow does not penetrate the outer rim seal.

The degree of reaction, where “h” is the static enthalpy, is as follows:

Pressure expansion, for a 1.5 stage is total-to-static pressure and for 1-stage is a total-to-total:

The flow coefficient is the ratio between the axial flow velocity and the peripheral (blade tip) speed of the rotor:

The loading coefficient represents the actual work performed by the blade with the blade speed:

The pressure coefficient for both total and static is defined as follows:

The total pressure loss coefficient represents the total pressure drop across the vane or blade row normalized by the dynamic head at the vane or blade exit, which is used to quantify secondary losses.

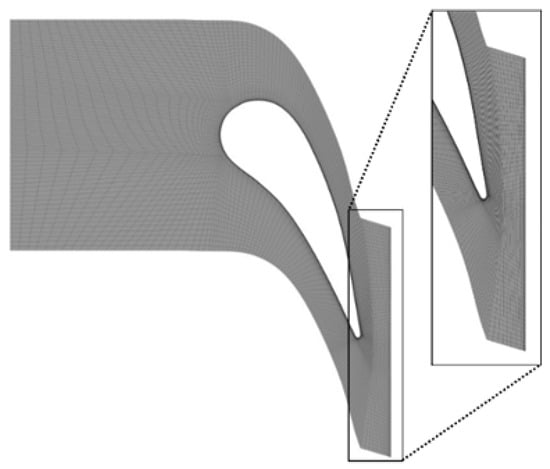

3.2.2. BATH Cavity Experimental Rig

The domain used here contains a single passage to represent 32 vanes, similar to the LISA approach. The stator vane domain was constructed with the stator inlet extended by about two times of the stator axial chords for a fully developed flow. Figure 6 shows the projection view of the stator mesh. The total mesh varies from 1 million to 5.3 million elements, and these configurations are considered for numerical derivatives.

Figure 6.

Projection view of stator vane single-passage mesh by ANSYS CFX 19.1 ICEM CFD.

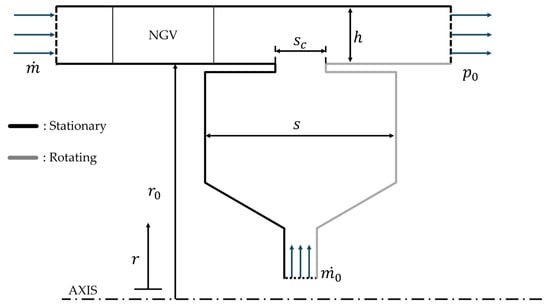

Most importantly, is the influence of the computational domain. As using the steady state RANS method corporate with Multi Reference Frame, there are four types of computational domain to consider, as illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 7 and Figure 8:

Figure 7.

Sketch of radial seal domain with wheel space submerged in the rotational part.

Figure 8.

Sketch of a “thin seal” approach with no interface involved.

- 1.

- The wheel space cavities are submerged fully in the stationary domain.

- a.

- A “thin seal” geometry approach.

- b.

- An original geometry.

- 2.

- The wheel space cavities are submerged fully in the rotational domain.

- a.

- Using the mixing plane (stage) interface.

- b.

- Using the frozen rotor interface.

With the frozen rotor method, the rotor is held stationary in both time and space and then applied to the pressure field directly across the interface. With these settings, to fully acquire the blade-passing phenomenon, the interface relative position (or the vane–blade relative position) must be rotated at a specific angle, meaning that various cases must be simulated. The interface is moved upstream to reduce the interface error in the central computational region. To account for that, a bladeless rotor approach is used. According to multiple researchers, including Scobie et al. [53] the testing of a very off-design condition shows a considerable effect of the blade-on-rim-seal-flow behavior. Furthermore, the rotor used here is a symmetrical aerofoil with the use of only exhausting the air before dumping it into the volute. The conclusion of the presence of rotors in this situation is needless.

In this section, for the convenience of the reader, the formula used for the rim seal is listed down below:

The rim-seal-sealing effectiveness:

Mainstream Reynolds and rotational Reynolds number:

Pressure coefficient:

Peak-to-trough pressure differences:

Sealing flow rate:

Sealing flow parameter:

Moment coefficient on the rotor disk:

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Numerical Deviation and Validation

4.1.1. The LISA Turbine

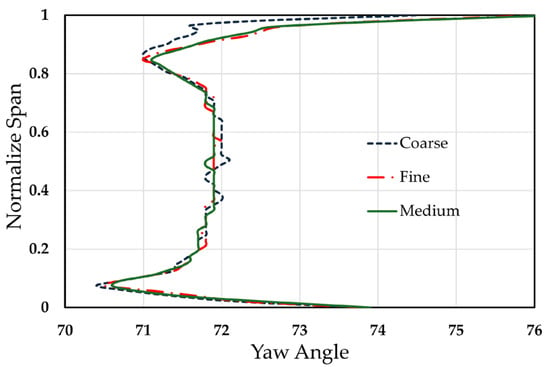

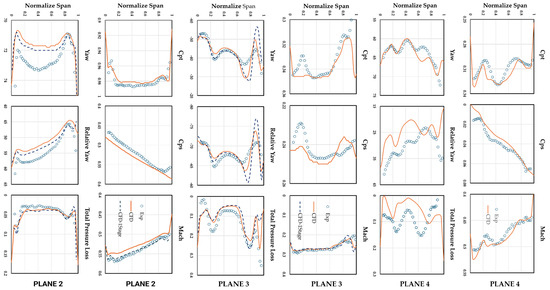

Numerical validation for the LISA turbine is performed, including both qualitative and quantitative comparison between the one-stage and 1.5-stage configurations for further implementation of the rim seal. Figure 9 shows the Yaw angle at Plane 2 for three different meshes, where the curves of yaw angle for the medium mesh and fine mesh overlap. Table 3 lists all the variables measured in experiment by [2]. For most parameters, having a relative error below 5% is more than acceptable for industrial applications. However, the total pressure losses parameter at three positions downstream of the vane/blade exhibits an error of no more than 30%. This parameter is crucial for determining the pressure losses of the fluid stream through the large-scale structure (vanes/blades) due to the loss phenomenon. In this experiment itself, the author notes that there was a significant difference in the measured data compared to the theoretical predictions. Summarized in Figure 10 is the quantitative variables across the rotor entrance and exit (illustrated in Figure 2), with the experiment’s outcome of [2]. The results from the simulation show good agreement with experimental data, with the largest discrepancies found primarily in the tip and hub of the channel, due to the influence of the secondary flow. However, the variables for the one-stage turbine are presented for demonstration purposes, as only this configuration is considered in this study.

Figure 9.

Yaw angle at Plane 2 (S1) for three different meshes.

Table 3.

Quality validation of both 1.5/one-stage LISA.

Figure 10.

Quantity validation of both 1.5/one-stage LISA.

With the removal of the second stator, and its replacement with outlet boundary condition mapping, the model now can run fully with the baseline conditions with excellent sizing in computational resources. In the mesh refinement studies for the one-stage turbine, the parameters of the course to the finest mesh show little fluctuation in every qualitative parameter. With only major differences in the quantitative parameters. Overall, choosing the mesh and boundary conditions can give a similar result to the baseline stage.

4.1.2. BATH Experiment Rig

To validate the consistency of the stator blade and the numerical method for capturing the wheel space flow, the pressure distribution at location A is used, along with the swirling flow measured at z/s = −0.75. Additionally, the non-dimensional velocity profile within the wheel space is compared to the results reported by Chen et al. [54]. This key validation metric is sealing effectiveness, which will be discussed in the next subsection, including the computational domain.

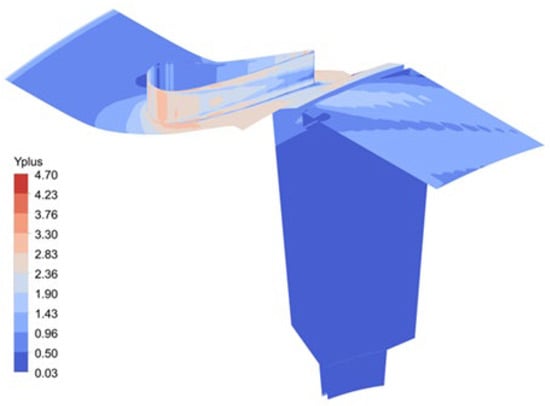

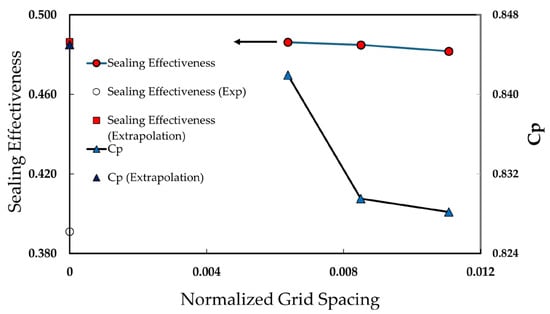

A mesh independence test was performed using the SST k-ω model at Φ0 = 0.03, with mesh sizes varying from 1 million to approximately 5.4 million elements for the axial rim seal using the MRF method, and from 0.73 million to 3.9 million elements at Φ0 = 0.043 for the axial thin seal configuration. The maximum value of y+ is less than 4.7, as shown in Figure 11. The Grid Convergence Index (GCI), based on the Richardson extrapolation method, was used in this study to assess system convergence. Introduced by [55], this technique is widely recognized in CFD simulation.

Figure 11.

Contour of y+ in axial rim seal configuration at Φ0 = 0.03.

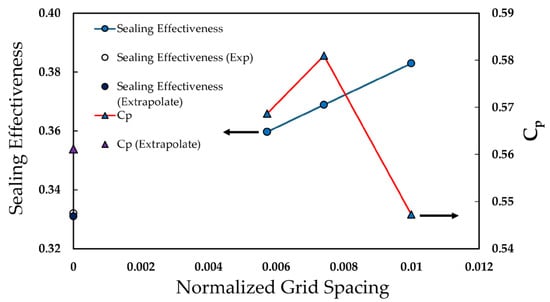

Table 4 and Figure 12 show the GCI results for the axial rim seal MRF at sealing flow parameters Φ0 = 0.03. It is evident that sealing effectiveness is highly dependent on the mesh. The extrapolation value is close to the experimental measurements though the convergence order for this parameter is relatively poor, requiring a higher number of meshes for better results. Conversely, the peak-to-trough pressure converges more quickly and provides good agreement with experimental data. This suggests that while the sealing effectiveness is mesh-dependent, the peak-to-trough pressure is more robust to variations in mesh resolution.

Table 4.

Results of GCI investigation for axial rim seal at Φ0 = 0.03.

Figure 12.

Grid Convergence Index for sealing effectiveness and peak-to-trough pressure at location.

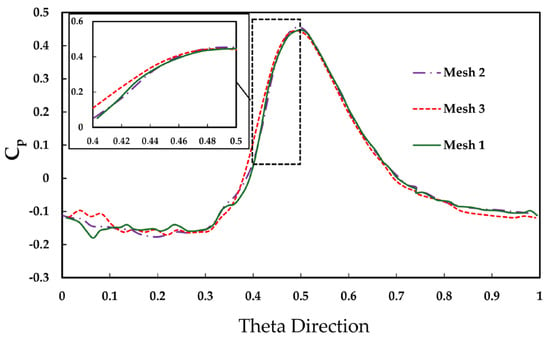

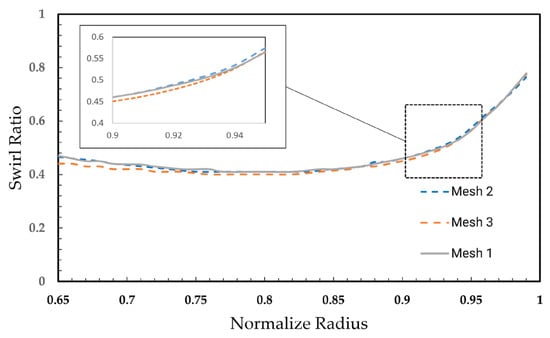

Figure 13 shows the pressure difference profile at Location A. The refined mesh shows oscillation at the position where the stator vane trailing edge passed through, and the medium-refined mesh agrees well with the most-refined at the slope of the profile. Furthermore, the swirl ratio measured at plane z/s = 0.25 (Figure 14) demonstrates good convergence from the inner radial across the seal region. Moving to the thin seal approach, the solution converges faster at any sealing flow rate, as no Coriolis force is added to the source term of the momentum equation. Figure 15 and Table 5 show the output data. For sealing effectiveness, the thin seal appears to be mesh-independent and highly converged, though extrapolated values still differ from experiments due to the computational domain (discussed later). Peak-to-trough pressure also converges quickly.

Figure 13.

Influence of mesh on pressure distribution at Φ0 = 0.03.

Figure 14.

Swirl ratio measured at plane z/s = 0.25 for three different meshes.

Figure 15.

Grid convergence index for thin seal configuration at Φ0 = 0.043.

Table 5.

Results of GCI investigation at Φ0 = 0.043.

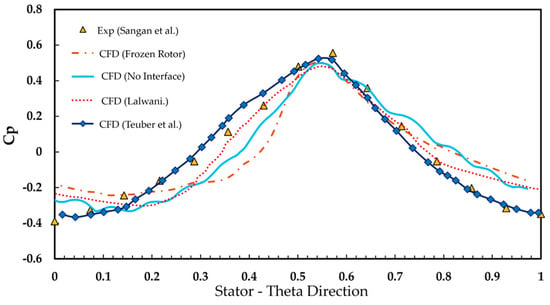

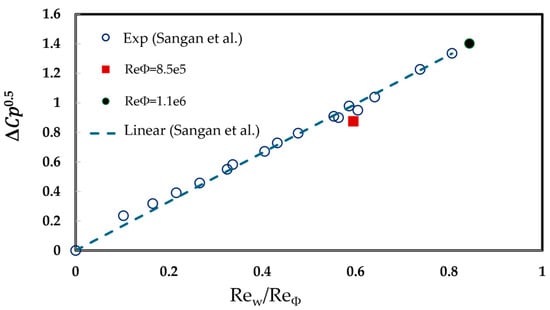

The pressure distribution coefficient is shown in Figure 16, with both no interface and measured behind interface case. The pressure distribution profile closely matches the experimental results, with peak values showing a maximum relative error of 10.34% for non-interface cases and 9.5% for interface cases. Further comparison is performed with other authors that use the BATH rig. In Lalwani cases [49], even though the author uses the steady RANS approach but with the rotor blade including and must measure five different blade angles to obtain the average value. Moreover, in the simulation, there might be a slight difference with the Reynolds number measured in the laboratory. For this, the square root of the peak-to-trough pressure distribution at location A is plotted against the ratio of mainstream Reynolds number to rotational Reynolds number in Figure 17. The off-design test at 3500 RPM shows a relative error of 11.07% compared to the regression value. However, an off-design test conducted at 4000 RPM results shows a better agreement with the regression line, with just a 0.57% error.

Figure 16.

Comparison of pressure distribution along one stator vane [34,35,49].

Figure 17.

Comparison of the square root of peak-to-trough pressure with the operating condition [34].

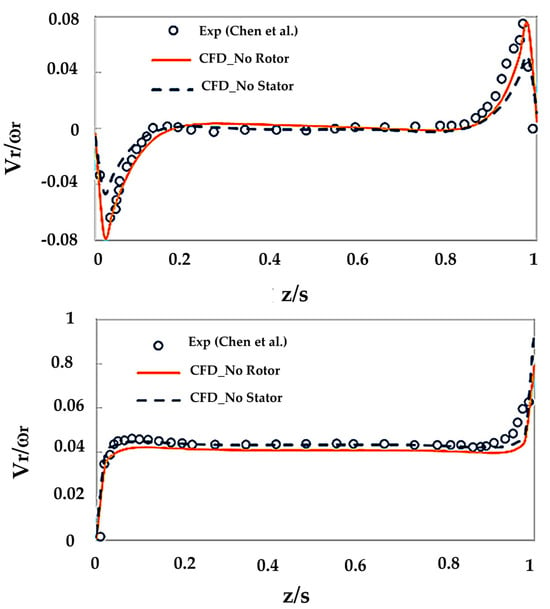

The swirling flow is highly dependent on computational domain configuration. The optimal setup occurs when the wheel space is fully included within the rotating domain. To test the validity of the computational method for the velocity field inside the cavities, besides the swirling flow measurement used in experiments, an additional non-dimensional velocity profile is measured at the radial position of r/r0 = 0.8. As illustrated in Figure 18, the experiment result by [54] is compared with the cavities at Gen#1 and there are no stator vanes at Gen#2. All are in good agreement with the entire domain of cases. With the stator left on the side, the radial outflow and inflow of the cavities slightly reduced; it has been observed that the presence of the Taylor vortex can give a blockage to the inner flow field. Overall, the simulation is in agreement with both experiment and theory for the swirling ratio of approximately 0.43.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the velocity flow field at Gen#1 and Gen#2 inside the rim seal at r/r0 = 0.8 [54].

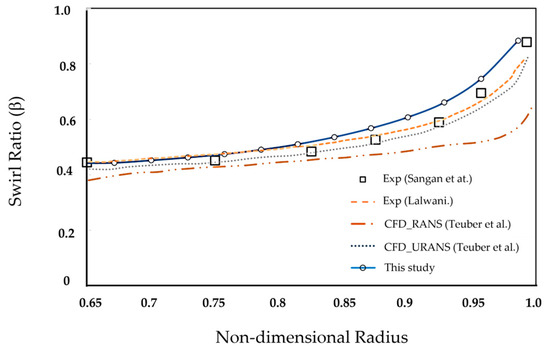

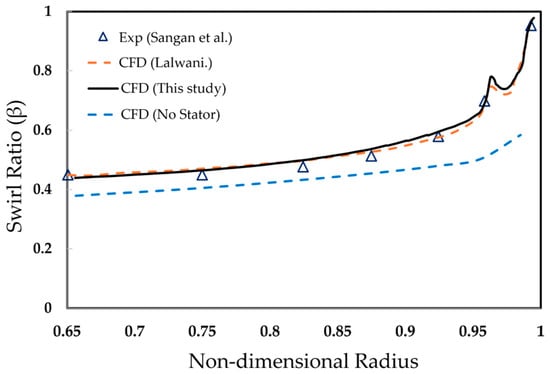

The swirl ratio measured at plane z/s = −0.75 was taken from the pitot tube in the test rig. The computational results for rim seal configuration Gen#1, Gen#2, and Gen#4 are shown in Figure 19, with Geometry #1 corresponding to the axial rim seal configuration. The simulation greatly captures the swirling flow below the non-dimensional radius of 0.8. This is logical because in many experiments conducted for stator–rotor systems, the r/r0 = 0.8 location is the superposition transition between linear or constant pressure and the velocity field transition to highly non-linear toward the rim seal gap. For values above 0.8, the simulation becomes deflected but still reasonably predicts the swirling flow toward the rim seal gap. The total integral relative error with the experiments was only about 3%.

Figure 19.

Comparison of swirling flow at plane z/s = 0.25 for rim seal configuration Gen#1 [34,35,49].

Moving to the Gen#2 geometry or the radial rim seal configuration, it shows more exciting results (Figure 20). As mentioned in the experiment, only a few pitot tubes are located at the stator wall to measure the swirling flow. In the simulation where the stator is installed, the swirling flow still has good agreement at a non-dimensional radius below 0.8—on the other hand, removing the stator results in reduced swirling flow inside the wheel space. Additionally, near the rim seal gap at the outer radial, a pronounced peak is observed where the rim seal changes direction radially. This peak is compared with the result of [49], having a slight difference in value. Let us look at the outer radii of the cases where the stator is removed, which shows no peak at all; this might suggest that this peak in swirling flow is caused by the externally induced ingression outer annulus’ influence on the inner rim seal. This might be the logical explanation for the difference in the peaks of two different simulations, left beside the difference in the solver setup (as in [49]); first-order resolution is used for the advection term, the energy equation is neglected because of highly unsteady phenomena, and the solution can make a difference in the result.

Figure 20.

Comparison of swirling flow at plane z/s = −0.75 for rim seal configuration #2 [34,49].

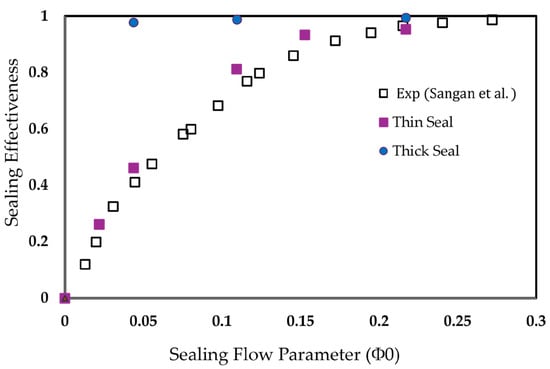

4.2. Influence of Computational Domain

The numerical method’s primary objective is to observe the amount of air that ingresses through the wheel space. By investigating the fourth type of domain listed above, the differences between CFD setups can be identified, and the best configuration for accurately simulating ingression can be determined. This subsection compares the sealing effectiveness result for different computational domain setups.

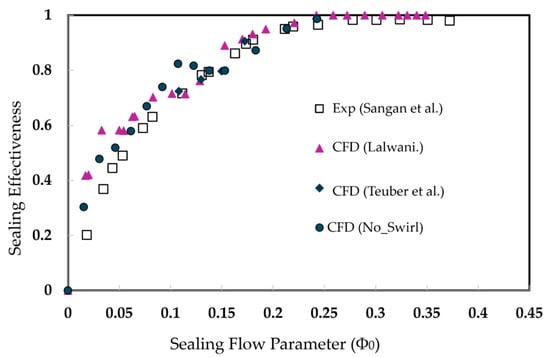

The first domain to investigate is the one that does not utilize the multi-reference frame method. The selected rim seal geometry was the axial Gen#4 seal, and modeling only the outer seal helped to reduce the computational resources. In this domain type, the ingress level is near ground zero for all sealant rates. As illustrated in Figure 21, the sealing effectiveness is remarkably high. The streamlines reveal a numerical vortex forming at the rim seal gap, which incorrectly blocks mainstream flow from entering the inner cavities, leading to inaccurate results.

Figure 21.

Sealing effectiveness for entirely stationary frame wheel space [34].

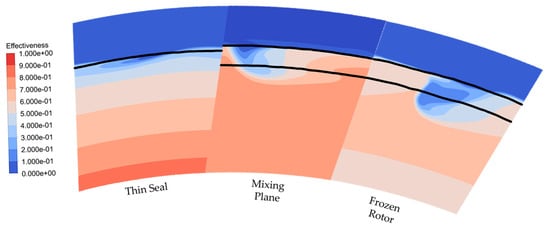

To compensate for that, an extreme domain simplification is used, with the gap geometry reduced to one mesh cell. The simulation produces a decent prediction of the ingress level. The margin of error does not exceed 5% for the given sealing flow rate. In terms of quantitative measurement, illustrated in Figure 22, the wheel space shows the rotating core in the meridional plane as predicted in the conventional rotational domain. The rim seal gap flow field shows the shear layer thinner but does not fully capture the ingression phenomenon well. However, compared to the MRF method, the shear layer at the rim seal gap is smaller and less intense. As shown in the contour plot of Figure 22, the MRF approach clearly visualizes a stronger shear layer, with ingression penetrating deeply into the wheel space through the rim seal gap, rather than narrowing the gap. In terms of visualization of the rim seal flow, the thin seal gives an adequate result compared to other domain types that will be discussed below.

Figure 22.

Contour of sealing effectiveness in radial–theta direction to the flow view for three types of domains for Gen#4 configuration at Φ0 = 0.045.

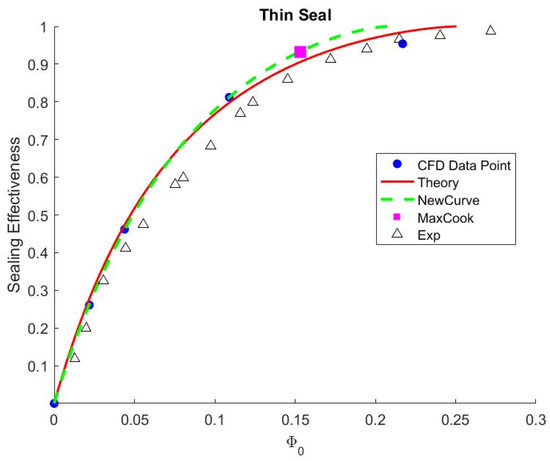

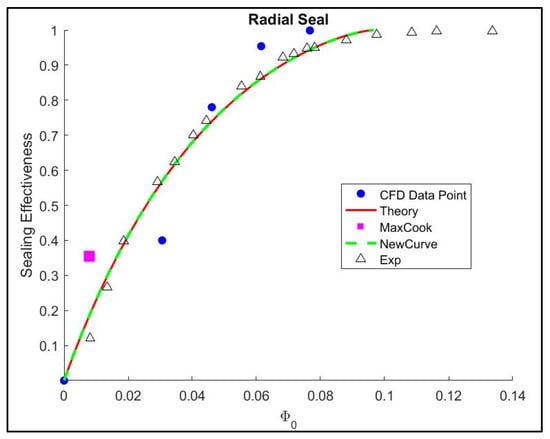

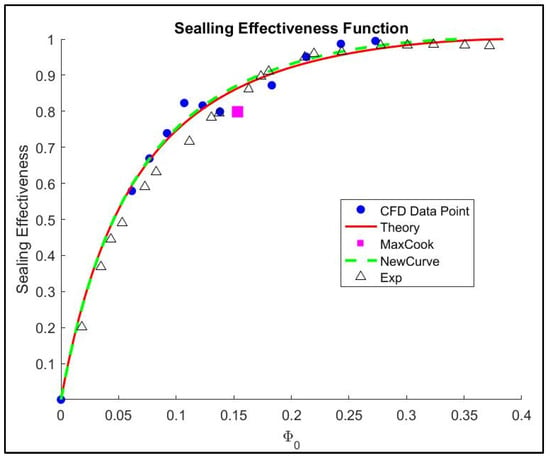

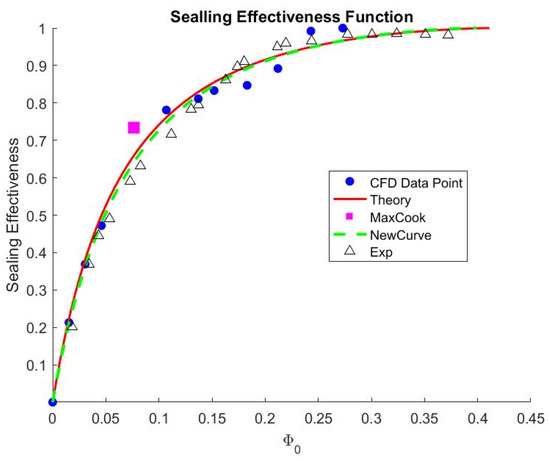

Overall, the “thin seal” method provides a preliminary approach to overcoming the stationary frame domain. The “orifice” model is used to predict the minimum sealing effectiveness, demonstrating reasonable agreement with experimental data (illustrated in Figure 23). Although the domain configuration is simplified, the sealing effectiveness remains a realizable data output in this case. A total of five simulation points does not ensure the overall convergence of the statistical data, but both theory data still predicted that 80% sealing effectiveness at half of the minimum sealing rate can be acquired. When solving the wheel space in the stationary frame of reference, the simulation achieved rapid convergence.

Figure 23.

Theoretical orifice model for thin seal approach.

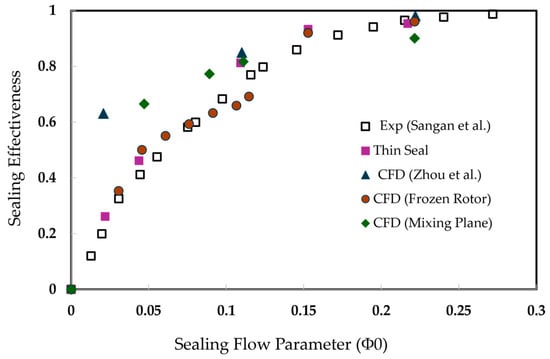

Moving on to the multi-reference frame method, this section compares the frozen rotor and mixing plane approaches. With the rotation of the domain implemented, ingression is clearly observed. This is illustrated in Figure 24 with the same Gen#4 configuration. At first glance, the sealing effectiveness closely matches the experimental data. The highest error points occur at the mid-sealing flow rate. This can be explained by the fact that at low sealing flow rates, the rim seal gap flow is primarily dominated by ingression from the outer annulus, whereas at high sealing flow rates, egression flow becomes dominant. When one of these flows is dominant, the flow field becomes quasi-steady in time, with limited mixing. However, within the middle sealing flow rate, none of these flows clearly prevail over each other. Thus, the flow field became highly unsteady and may cause errors in the steady RANS solution. This unsteady phenomenon includes the large-scale structure observed with unsteady RANS at a lower sealing flow rate. In other words, with insufficient sealing flow, the solver can also fail to filter the unsteady and can lead to over prediction of sealing effectiveness. As an example, the publication by [56] states that for a single-pitch passage model, this structure does not predict correctly.

Figure 24.

Sealing effectiveness of Gen#4 rim seal configuration with MRF method [34,56].

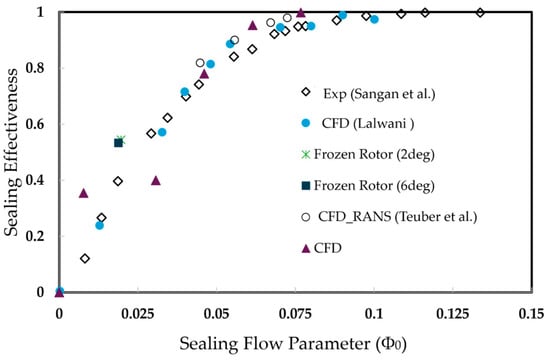

Gen#2, or the radial seal clearance configuration shown in Figure 25, shows significant error at lower sealing flow rates. As stated above, at insufficient sealing flow, even though the steady RANS solution converges, the results still exhibit large errors. The unsteady instabilities within the rim seal gap cause fluctuations in the solution, leading to variability when compared to actual measurements. This is particularly evident in the radial seal, where low sealing flow rates can allow Taylor instabilities to develop within the gap. The difference from the CFD by Lalwani [49] lies in the numerical setup: neglecting the energy equation (a major term in the transport equation) and using a first-order scheme gave better agreement with the experimental data. Figure 26 illustrates the use of the orifice model to fit the data, which theoretically shows a reasonable agreement between minimum sealing flow and the experiment curve. With only six data points, the statistical fit converges, with no significant error after removing the point with the maximum Cook’s distance.

Figure 25.

Sealing effectiveness of Gen#2 rim seal configuration with the MRF method [34,35,49].

Figure 26.

Sealing effectiveness orifice model for radial seal.

The selected interface location greatly influences pressure distribution in the annulus, which is a key driver of ingression. The frozen rotor’s pressure profile is applied directly to the rotating-frame side of the interface. In conventional turbomachinery computation, the frozen rotor is generally regarded as a robust method. However, since it is applied directly, the interface must move over time to capture all interactions between the rotor blades’ relative positions and the upstream flow. When the rotor is removed, there is no need to rotate the frame; as illustrated in Figure 26, rotating the interface does not produce significant differences in the data for the Gen#2 rim seal.

Furthermore, at lower sealing flow rates, the convergence of the tracer gas transport equation is notably slow. This might be why many authors conducting numerical investigations choose to start from higher sealing flow rates. Many authors suggest using an alternative sealing effectiveness calculation based on temperature at a lower sealant rate. However, these results still require reliable experimental data for validation.

The last seal to be investigated is the axial rim seal, which is the simplest configuration (Gen#1). In this case, the computed sealing effectiveness varies the most at medium sealing flow as shown in Figure 27. In the radial seal configuration, pressure-driven ingress dominates the outer gaps and is blocked by the “curtain” near the inner seal, resulting in a quasi-steady flow with moderate sealing effectiveness. This starts very early as the ingression flow mixes with the inner seal cavities. The best way to accommodate this is simply observing the upper sealing effectiveness and neglecting the lower flow. However, in the investigation by [49], which includes the rotor and employs multiple frozen rotor positions, the averaged value shows better agreement with the experimental results.

Figure 27.

Sealing effectiveness of Gen#1 rim seal configuration with the MRF method [34,35,49].

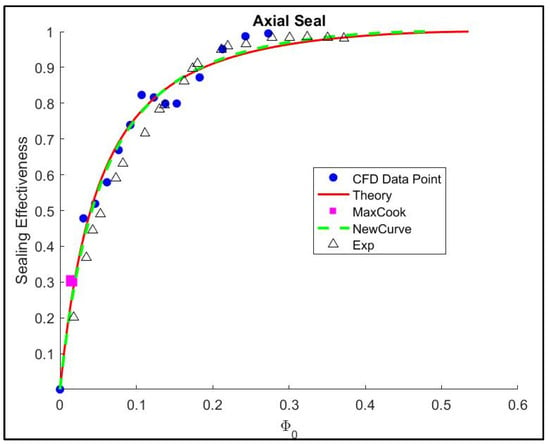

Using the orifice-fitted model, the minimum sealing effectiveness calculated overshot by little bit (Figure 28). However, the maximum Cook’s distance in this case tends to lie in the lower sealing flow rate. It is denoted that the data have the power to the function the most, coinciding with the CFD error at low-to-medium sealing flow. By removing all the lower sealing flow data, the solution to the sealing function would be in excellent agreement with the experimental measurements (Figure 29). This might be considered when constructing a new rim seal, by investigating from the top to the bottom.

Figure 28.

Sealing effectiveness orifice model for axial seal.

Figure 29.

Sealing effectiveness function for axial seal by removing lower sealing flow data.

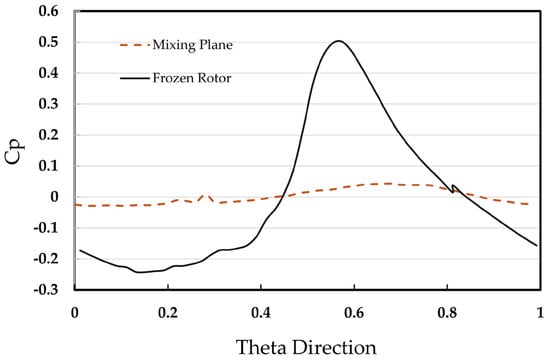

The next and final domain configuration to be investigated concerns the change in the interface model. With the mixing plane model, all flow quantities are circumferentially averaged at the interface location. This gives the model somewhat limited in providing a physically meaningful solution. However, the mixing plane method still gives an excellent, cost-effective model for many turbomachinery applications. By conducting simulations with the mixing plane interface for the non-bladed model, it is possible to confirm the drawback of the mixing plane for calculating the ingression flow. As shown in Figure 30, the mixing plane significantly reduces the pressure distribution compared to the frozen rotor method. Consequently, this model exhibits very high sealing effectiveness across all rim seal geometries. However, the swirling ratio remains similar to that of the previous model. In conclusion, a comparison study between multiple computational domains has been conducted ranging from the simplest domain to more detailed configurations to measure the accuracy of predicting the ingression to the cavities. The frozen rotor MRF approach with no rotor blades proves to be an accurate and fast CFD method to visualize sealing effectiveness, especially when combined with the implementation of the orifice model to represent the sealing function base on the CFD result. Through this section, quantitative agreement with experiments can be achieved with a high level of accuracy using the steady RANS approach. The findings contribute to understanding the dynamics of rim seal flow and emphasize the need for careful consideration of modeling approaches in turbomachinery applications. Further research and refinement of computational models will help enhance the accuracy of predicting sealing effectiveness in different configurations.

Figure 30.

Pressure distribution at Location A for two different interface models.

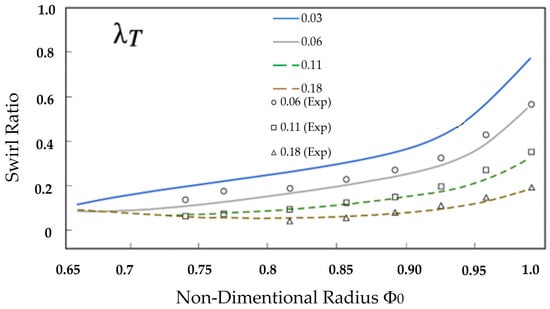

4.3. Effect of Pre-Swirling the Cooling Flow on the Wheel Space Rotating Core

Pre-swirling flow involves adding tangential velocity to the fluid as it enters the wheel space. This pre-swirl nozzle aims to lower the temperature and pressure of the cooling air entering the disk for blade-cooling, while also introducing swirl velocity to help the fluid enter the rotating passages. However, when it comes to rim seal cooling flow, adding swirl velocity impacts the overall flow field. As the fluid gains rotational speed, it can affect the rotating core that is exhibited inside the cavities. For convenience, the computational domain will not model any pre-swirling guide vane but instead add the tangential directly to the fluid as boundary conditions match the rotor’s rotational speed. First, look at the flow field when the cooling flow is not pre-swirled. As the theory predicted, by introducing the cooling flow will suppress the rotating core. By measuring at the plane z/s = 0.25, it can be seen clearly that the cooling flow heavily influences the core rotating speed to relatively small; this phenomenon also measured in experimental (shown in Figure 31). The computed value shows good agreement even with higher sealing flow. Noticing that the sealing flow entering the wheel space got induce some rotational speed and slowly reduced to the actual swirl in the wheel space.

Figure 31.

Swirl ratio of axial rim seal with increasing flow rate with no swirl.

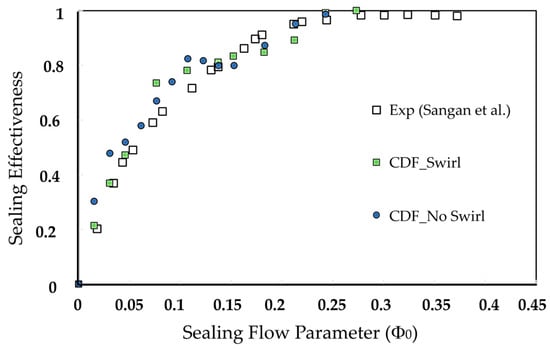

Indicated in Figure 32, the sealing effectiveness of both cases shows similar output. From the “orifice” model, the swirling ratio of the inner cavities does not influence the ingression flow but does affect the velocity of the egression flow. However, at medium sealing flow rate, the behavior remains similar and produces the largest error region. The “orifice” solution shown in Figure 33 closely matches the experimental data for non-swirling flow. Furthermore, the pressure drops at the outer annulus are very small between the two cases, with a relative 0.03% difference in mass flow average. Therefore, it can be concluded that the swirling flow does not affect the mainstream flow more than the non-swirling flow. Although the “orifice” model suggests that the egression velocity depends on the inner cavities swirling flow, within the narrow rim seal gaps, the fluid becomes heavily mixed before entering the outer annulus. The real difference may come from adding a swirling nozzle near the rim seal gap.

Figure 32.

Sealing effectiveness of axial rim seal with pre-swirl and swirl cooling flow [34].

Figure 33.

Sealing effectiveness function for axial seal with swirling flow.

Most importantly, swirling the cooling fluid helps reduce the velocity gradient between the fluid and the rotor disk. Since skin friction on the rotor depends on wall shear stress which is influenced by viscous friction and the velocity gradient in the boundary layer, adding swirl aligns the fluid velocity more closely with the rotor’s rotation speed. Without swirl, stationary fluid meets the rotating surface, creating a sharp velocity gradient and a highly skewed shear flow in the boundary layer. This skewed gradient thus increases the wall shear of the rotor; as a result, it increases the negative torque on the rotor in the form of windage losses.

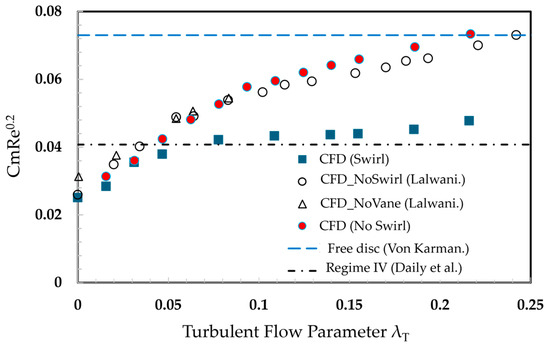

When the flow is pre-swirled, the interaction between the boundary layer fluid and the cooling fluid improves due to a reduced velocity gradient in the circumferential direction. This smooths the velocity gradient at the rotor’s boundary layer, thereby lowering wall shear. As shown in Figure 34, the moment coefficient on the rotor wall rises with increasing cooling flow in the no-swirl cases, reaching the free disk empirical value at λT = 0.24. The difference in the sealant flow rate at which the free-disk value is matched, compared with the results of Lalwani, may be caused by additional energy transfer into heat due to frictional forces. In general, however, the moment coefficient increases as the sealant flow increases.

Figure 34.

Moment coefficient on the rotor wall swirl and no swirl for axial seal [14,18,49].

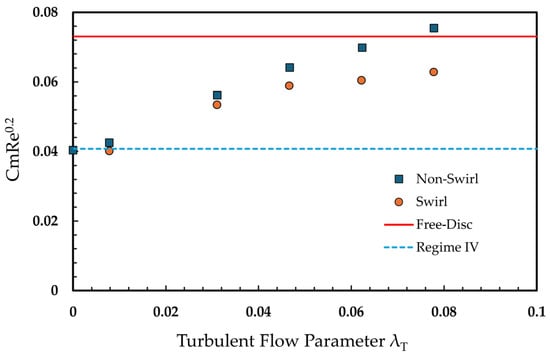

When pre-swirling the coolant fluid, it is clearly seen that the moment coefficient decreases moderately. At lower sealant flow rates, the fluid entering the cavities is relatively small in magnitude and does not contribute much to the general flow field. As the cooling flow increases, the incoming fluid displaces a larger portion of the rotor’s boundary layer fluid. Compared with the non-swirling flow, the moment coefficient is reduced by 35%, which contributes directly to an increase in turbine work output. Furthermore, the entrain flow still supplied the rotating core mass flow rate, thus suppressing the rotationally induced ingress without significantly affecting the rotating core itself. Increasing the flow raises the pressure inside the cavities, which helps block the incoming pressure-driven ingress.

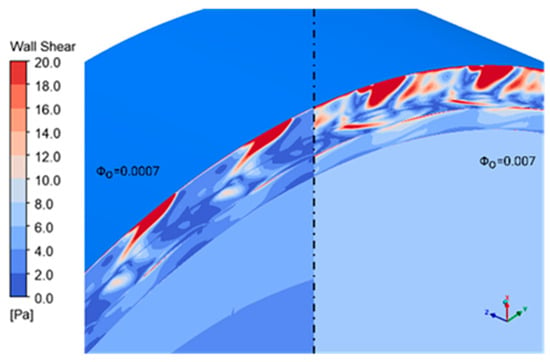

The pre-swirling flow on the radial rim seal (Gen#2) acts the same way as the axial rim seal. The moment coefficient on the rotor wall decreases as fluid with rotational velocity enters the cavities (Figure 35). However, this reduction is only about 17% at the maximum sealing flow rate, possibly due to the increased surface area at the overlap gaps. The overlap region will mostly block the ingression caused by pressure difference. As then the outer gap will occurring the mixing with highly unsteady flow phenomenon. As seen from Figure 36, the wall shear stress at the gap is much higher than the inner cavities. As the highest region is the ingression from the vanes wake hitting the rotor wall (occurring in both axial and radial). This is followed by the mixing region within the gap resulting in multiple high-shear stress regions. This region shown is not to be suppressed but split into many zones with increased wall shear amplitude. In the axial seal, the swirling fluid is suppressed all the way to the inner rim seal gaps. In the case of the radial rim seal, however, the overlap section operates independently of the swirling flow and therefore contributes little to the reduction in moment coefficient. The final compact explanation is that the “true” disk radial is much shorter than the axial seal thus the region swirling flow effect is smaller.

Figure 35.

Moment coefficient on the rotor wall swirl and no swirl for radial seal.

Figure 36.

Wall shear pressure distribution on the overlap region in radial rim seal.

In conclusion, the pre-swirl nozzle installed at the sealing flow inlet significantly influences the flow field within the cavities, particularly sustaining the rotating core in the lower wheel space. While it does not suppress this rotating structure, it also does not degrade sealing effectiveness, which remains consistent with experimental results for non-swirling flow. However, due to the long radial distance between the inner and outer regions, the pre-swirl has minimal impact on the flow behavior near the rim seal gap and its interaction with the outer mainstream.

4.4. Time-Dependent Rim Seal Flow Structure

This section investigates the unsteady phenomenon in radial rim seal and axial Gen#4 rim seal configuration using the harmonic balance method. The selected harmonic in both cases is three (seven time planes in total). The solution is considered as a convergence by measuring the pressure at points x/r0 = 0.956, which show a periodic value about three times the rotor speed. The simulation runs for about 15 solar days until a periodic pressure monitor is established. In the radial configuration, even with reduces local time step and under relaxation, the solution diverges after about 1500 iterations for both energy and scalar fields. This phenomenon is encountered by [57], who suggested that the unsteady phenomenon overshoots (also known as the Gibbs effect) in the harmonic function with a small number of harmonics (<5), destabilizing the solution. However, with a higher harmonic, the turbulence harmonic becomes unstable and destabilizes the solution. To bypass this problem, using the technique by Lalwani to neglect the energy equation and conducting simulations at lower harmonic (3) results in good convergence of pressure after 3000 iterations.

In the axial Gen#4 configuration, the sealing effectiveness calculated at Φ0 = 0.109 has a relative error with experimental result of only 7%. The fast Fourier transform is conducted at the middle point between the inner and outer gaps for the pressure and velocity component variables.

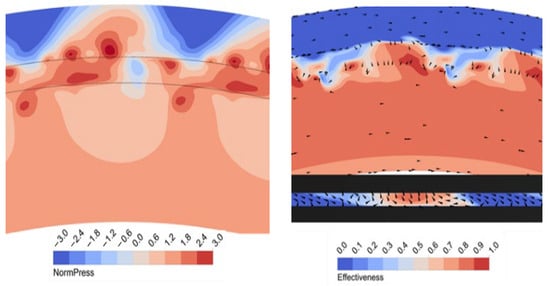

The development of Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities [58] is observed within the rim seal gap region. Shear vortices of multiple length scales are observed, with smaller vortical structures embedded within larger ones, as illustrated in Figure 37. Owing to their inherently unstable nature, these structures repeatedly form and dissipate within a single blade-passing period and are captured at approximately 71% of the blade-passing cycle. When the sealing effectiveness distribution is examined, it becomes evident that the smaller shear vortices tend to merge, forming a larger coherent vortex structure. Within a Kelvin–Helmholtz vortex, there is the formulation of a low/high pressure region in the measuring plane. Interestingly, this time-plane captured a large-scale structure standing below a high-pressure region in the annulus. The Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism creates a lower pressure region that is supposed to be the egression region (indicated as a high sealing effectiveness region), which is blocked by the higher pressure at the annulus. This leads to the formation of a “choke” region, which increases the cavity pressure and results in the development of 32 large-scale vortex structures (or “bubbles”).

Figure 37.

Contour of sealing effectiveness and normalize (gauge) pressure at middle the rim seal gap (Gen# 4), looking from axial and radial position at the 0.71 bladepassing period.

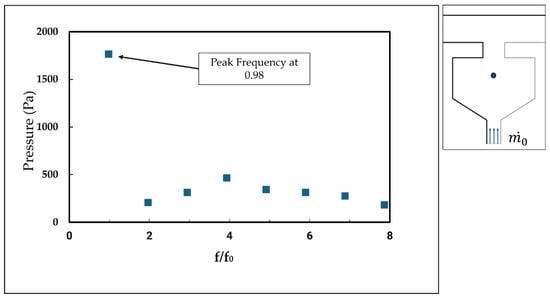

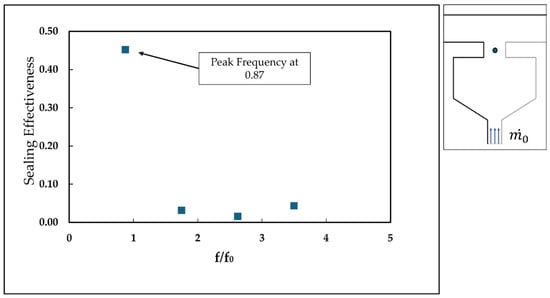

This phenomenon occurs periodically within the wheel space cavities, consistent with other turbomachinery effects. A discrete Fourier transform was applied to convert the time–domain variables into the frequency domain, as plotted in Figure 38. The frequency is non-dimensional, using the rotor rotational frequency of 2133 Hz as the reference. The pressure variable having a peak magnitude of 98 percent means it has a large-scale structure rotational speed of 98% rotor speed. A higher frequency signifies fluctuations originating from the mixing process at the rim seal gap, which propagates inward into the wheel space.

Figure 38.

Pressure at monitor point (right) against frequency domain.

The sealing effectiveness component, plotted in the frequency domain and normalized by the rotor frequency, is presented at the mid-point of the rim seal gap in Figure 39. The observed peak at approximately 0.87 times the rotor frequency indicates that the ingress region moves at 87% of the rotor speed. The small perturbation at higher frequencies corresponds to fluid fluctuations associated with the blade-passing frequency. These fluctuations are largely driven by the formation of large-scale structures resulting from the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability. The fluctuation will create more mixing losses within the rim seal gap and thus might reduce turbine efficiency significantly. Additionally, these instabilities make the rim seal flow more challenging to predict. However, numerous studies have shown that at higher sealing flow rates, these instabilities are effectively suppressed. While the presence of such unsteady phenomena can significantly affect rim seal performance and overall turbine efficiency, quantifying their impact on turbine efficiency is beyond the scope of the present study.

Figure 39.

Sealing effectiveness at monitor point (right) against frequency domain.

4.5. Effect of Wheel Space Cavities on Turbine Performance

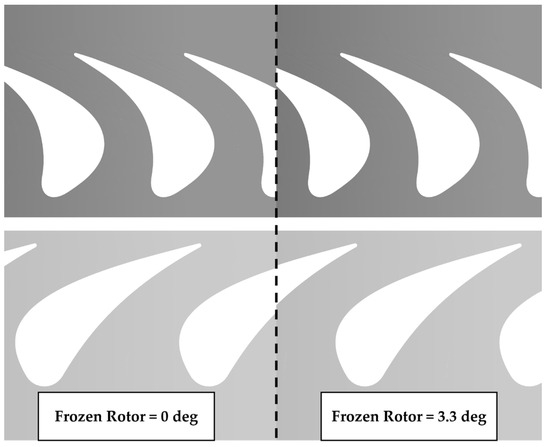

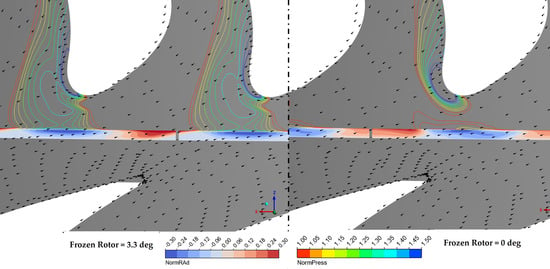

This section discusses the implementation of axial rim seal configuration into the LISA turbine. Due to time constraints and computational resources, not every frozen rotor blade angle and sealing flow rate parameter is calculated. In Figure 40, the result was only given with two frozen rotor angles for each case (0 angle and haft blade angle π/27 radian) and the sealant rate of 0.025 and 0.05 of mainstream flow. The results are average for the number of frozen rotor blade angles. Table 6 compares turbine parameters with and without wheel space cavity. The addition of wheel space cavities does not significantly change the model’s quality. This model will be considered the baseline configuration for the rim seal model.

Figure 40.

Frozen rotor blade angle.

Table 6.

Comparison of one-stage turbine parameter w/o implementation of wheel space cavities.

For quantitative analysis, two velocity streamlines are examined: the red streamline originates from the outer rim seal gap, while the lighter streamline originates from the inner rim seal gap. At the 0° model, the fluid enters the cavities in the high-pressure region zone as predicted, while the egression fluid is drawn from the mainstream in the low-pressure region. The egressing fluid travels between the blades and merges with the secondary flow further downstream. Notably, at the 0° angle, the red streamline travels and enters the rim seal gap but does not penetrate further into the cavities and curves back into the mainstream. The key factor influencing this behavior is the rotor–stator interaction, particularly the trailing end-wall vortex formed at the stator’s trailing edge. In Figure 41, the velocity vector of the surface 10% span is plotted with the normalized pressure at the rotor hub. In the half-degree angle (3.3°), the trailing vortex stream hits the incoming rotor at the leading edge, generating a high stagnation pressure region over the rotor near the end-wall that propagates upstream to the rim seal gap. This creates a driving force that pulls the “already-travelled-through” fluid to came back toward the upstream rim seal, making a large ingression region. To satisfy the continuity equation, the egression flow must increase with an expansion of the low-pressure region. Furthermore, the trailing vortex impacts the rotor leading edge, merges with the egress flow, and ultimately ends up in the adjacent rotor suction side end-wall secondary flow.

Figure 41.

Streamline ISO and projection view in the rim seal region.

At a reference angle of 0 degrees, the stagnation points at the rotor’s leading edge are generated by the preceding counter-rotating stator. This means that the “in-line” stator trailing vortex streamline simply passes through, resulting in a smooth pattern of the ingress and egression. The normalized pressure distribution is also less intense than at the 0.5° case. The egression still occurs between two adjacent rotors and eventually merges into the suction side secondary flow. Further observation of the ingression flow streamline shows that, in both cases, the streamline that is marked in a different color follows a different trajectory. The ingression flow that curves back into the egression flow indicates the gap recirculating zone. This phenomenon in this situation can be explained by the high swirling velocity of the mainstream flow, as the ingression meets the rotor wall that is already a pressure-driven egression region (due to high tangential velocity). This explanation somehow agrees with the “orifice” model, in which the outer swirling flow reduces ingression, as reported by several authors.

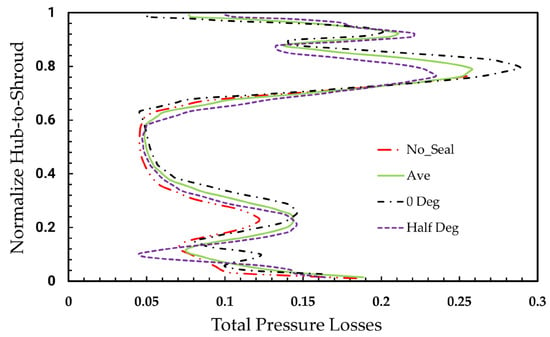

The total pressure losses, using the baseline stage as reference, are plotted in Figure 42. The major contribution to the end-wall secondary losses is clearly in the zero-degree angle cases, where the flow between the rotor interacts with the upstream vane trailing vortex and the fluid drawn from the rim seal. This egress fluid thickens the rotor inlet boundary layer, consequently increasing secondary losses. In contrast, the half-rotor angle has a high stagnation region at the rotor inlet and thus flushes out the boundary layer, making it thinner and reducing the secondary flow losses. However, the average value of the two frozen rotor angles is relatively similar to that of the baseline stage. Overall, simply adding the wheel space cavities already influences the “pseudo-time” flow field at a different blade angle, while the qualitative parameters remain the same as in the baseline stage.

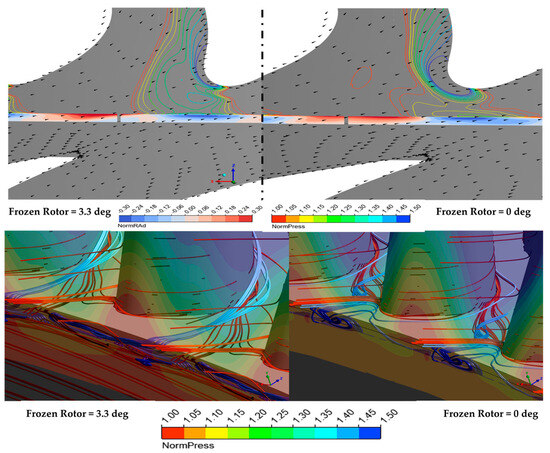

Figure 42.

Total pressure loss comparison between baseline and rim seal turbine.

With the inner cavities now introduced with the cooling flow at 3250 K with about 0.025 and 0.05 percent of the mainstream flow, the flow field now becomes harder to solve using the steady-state solver. The very high mixing progress at the rim seal gap makes the flow highly unsteady and it is even coupled with the rotor–stator interaction. The vector-contour and the streamline traveling backward from the rotor blade show interesting observations, with the 3.3-degree model having a spoiled high-pressure region that “compresses” the egression fluid region to merge into the secondary vortex right after leaving the rim seal gap. For the zero-degree angle, the up-stream vortex path traveled through the egression region does not suppress it but merges the egression fluid with the vortex and thickens the boundary layer as a resultant, just like the cases without the sealing flow. The vortex hit the rotor then split to either the adjacent or local suction side.

Consider the sealing effectiveness of the two available cases here. The average value is way off from the BATH experimental rig (difference geometry, of course). The zero-degree blade angle contributes highest to the sealing efficiency. As the stagnation point is stronger at the 3.3-degree angle, the fluid strongly drives into the seal gaps, thus reducing efficiency. As shown in the pressure contour in Figure 43, the high-pressure region penetrates deeper into the gaps compared to the zero-degree case.

Figure 43.

Vector contour and streamline near the rim seal gap at flow rate = 0.05%.

With implementation of the pre-swirled cooling flow into the wheel space, the turbine experiences a decrease in isentropic efficiency. By increasing the mixing region and increasing the sealing flow, the efficiency of the turbine does not suddenly drop as expected but by a very small gradient. However, this result is not fully clear as stated above, as the cavities are harder to fully seal at a higher sealing flow rate; this is because, by then, the reduction in efficiency will be greater.

5. Conclusions

This study combined steady RANS with an MRF formulation and passive-scalar transport to investigate rim seal ingression, sealing effectiveness, and cooling-flow effects in configurations derived from the BATH rig and the LISA turbine. The numerical predictions reproduce the main experimental trends reported in previous works, particularly the dependence of sealing effectiveness on purge flow and the pressure and swirl distributions in the wheel space, confirming that the present approach is consistent with established rim seal data.

The main contribution of this work is a systematic comparison of several computational domains and interface treatments. The results show that a frozen rotor MRF configuration with the cavities submerged in the rotating frame offers the best compromise between accuracy and cost, while simplified stationary and mixing plane domains tend to overpredict sealing effectiveness. In addition, the thin-seal-plus-orifice approach provides a practical method to estimate minimum sealing flow for different geometries, and the pre-swirled cooling flow is shown to reduce rotor moment coefficient without strongly affecting sealing performance.

Future work will focus on extending the unsteady analysis, including harmonic balance and LES, to better quantify large-scale instabilities and their impact on minimum purge-flow correlations. Further studies including conjugate heat transfer and more engine-realistic multi-stage seal designs are also needed to translate these findings into optimized gas turbine applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.N. and C.T.D.; methodology, T.L.N.; software ANSYS, ANSYS CFX 2019 R2, C.T.D. and D.A.N.; validation, P.A.T., G.-D.P. and C.T.D.; formal analysis, T.L.N.; investigation, D.A.N. and P.A.T.; resources, C.T.D.; data curation, D.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.N. and C.T.D.; writing—review and editing, T.L.N. and D.A.N.; visualization, T.L.N. and G.-D.P.; supervision, T.L.N. and C.T.D.; project administration, T.L.N.; funding acquisition, T.L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Hanoi University of Science and Technology (HUST) under project number T2023-PC-019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| EI | External-induced ingress |

| RI | Rotational-induced ingress |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamic |

| SST | Shear stress transport |

| GCI | Grid Convergence Index |

| GGI | Generalize grid interface |

| RANS | Reynolds average Navier–Stokes |

| MRF | Multi-reference frame |

| GRZ | Gap recirculation zone |

| Symbols | |

| c | Concentration of tracer (kg/m3) |

| Cp | Pressure coefficient/constant pressure heat capacity (J kmol−1K) |

| Cw | Non-dimensional flow rate |

| Cm | Moment coefficient |

| ε | Sealing effectiveness |

| h | Enthalpy (J) |

| Mass flow rate (kg/s) | |

| M | Mach number/torque (nM) |

| R° | Degree of reaction |

| RΦ | Rotational Reynolds number |

| Rw | Mainstream Reynolds number |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| r0 | Inner platform radius (mm) |

| p | Static pressure (Pa) |

| Average local static pressure (Pa) | |

| Gc | Non-dimensional rim seal parameter |

| ω | Rotor angular speed (rad s−1) |

| ρ | Air density (kg m−3) |

| μ | Air/dynamic viscosity (kg m−1s−1) |

| U | Blade speed (m s−1) |

| Vz | Axial velocity component (m s−1) |

| γ | Pressure losses coefficient |

| η | Efficiency |

References

- Denton, J.D. Loss Mechanism in Turbomachines. J. Turbomach. 1993, 115, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, T. Control of Rotor Tip Leakage and Secondary Flow by Casing Air Injection in Unshrouded Axial Turbine. Doctoral Dissertation, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, O.P.; Butler, T.L. Predictions of Endwall Losses and Secondary Flow in Turbine Cascade. J. Turbomach. 1987, 109, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, L.S. Secondary Flow in Axial Turbine—A Review. Heat Transf. Gas Turbine Syst. 2001, 934, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AinLey, D.G.; Mathieson, G.C.R. An Examination of the Flow and Pressure Losses in Blade Rows of Axial-Flow Turbines. In Aeronautical Research Council Reports and Memoranda; H.M. Stationary Office: London, UK, 1951; Available online: https://reports.aerade.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826.2/3451 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Herzig, Z.; Hansen, A.G.; Costello, G.R. A Visualization Study of Secondary Flow in Cascades; National Advisory Committee of Aeronautics: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.R. An Investigation of the End-Wall Boundary Layer of a Turbine Nozzle Cascade. Trans. ASME 1957, 79, 1801–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, W. The Secondary Flow in a Cascade Turbine Blades. In Aeronautical Research Council Report and Memoranda; H.M. Stationary Office: London, UK, 1955; Available online: https://reports.aerade.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826.2/3545 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Dawes, W.N. A Comparison of Zero and One Equation Turbulence Modelling for Turbomachinery Calculations. In Proceedings of the ASME 1990 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exposition, Brussels, Belgium, 11–14 June 1990; V001T01A093. American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A. The Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Compressible Fluid Flow; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.; Denton, J.; Pullan, G.; Curtis, E.; Longley, J. The Effect of Stator-Rotor Hub Sealing Flow on The Mainstream. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2006: Power for Land, Sea, And Air: Turbomachinery, Parts A And B, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 May 2006; Volume 6, pp. 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.M.; Rogers, R.H. Flow and Heat Transfer in Rotating-Disc Systems. Volume 1: Rotor—Stator Systems. J. Fluid Mech. 1989, 1, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorsen, T.; Regier, A. Experiments on Drag of Revolving Disks, Cylinders, And Streamline Rods at High Speeds; NASA, Langley Aeronautical Lab: Langley, VA, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Karman, V. Uber laminare und turbulente Reibung (On Laminar and Turbulent fiction). J. Appl. Math. Mech. 2010, 1, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruschwitz, V.E. Turbulente Reibungsschichten mit Sekundärströmung. Arch. Appl. Mech. 1935, 6, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, G.K. Note on a class of solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations representing steady rotationally symmetric flow. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 1951, 4, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewartson, K. On the flow between two rotating coaxial disks. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1953, 49, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, J.W.; Ernst, W.D.; Asbedian, V.V. Enclosed Rotating Disks with Superposed Throughflow: Mean Steady and Periodic Unsteady Characteristic of Induced Flow; Army Research Office: Durham, UK, 1964; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/142983 (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Poncet, S.; Chauve, M.P.; Schiestel, R. Batchelor versus Stewartson flow structures in a rotor-stator cavity with throughflow. Phys. Fluids 2005, 17, 075110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, J.W.; Nece, R.E. Chamber Dimension Effects on Induced Flow and Frictional Resistance of Enclosed Rotating Disks. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, F.J.; Owen, J.M. The Fluids Dynamics of a Shrouded Disk System with a Radial Outflow. J. Eng. Power 1970, 93, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]