Abstract

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are promising photovoltaic technologies, yet their performance is critically influenced by the relative permittivity (εr) of the active layer, which governs charge carrier dynamics. This study employs SCAPS-1D simulations coupled with complex impedance and modulus spectroscopy to systematically investigate the impact of varying the εr of the MAPbI3 layer from 4 to 12. We find that while the open-circuit voltage (Voc~1.05 V) and short-circuit current density (Jsc~25 mA cm−2) remain stable, the FF and efficiency η (%) decline from 78% to 70% and 20% to 17%, respectively, with increasing εr. Impedance analysis deconvoluted this trend, revealing a decrease in recombination time (τ1) and a peak in ionic transport time (τ2) at εr = 7. The optimal performance of 18.86% was achieved at a lower εr, demonstrating that minimizing recombination losses through permittivity engineering is crucial for advancing PSC efficiency.

1. Introduction

In recent years, perovskite-based materials have generated considerable interest. Perovskite refers to a group of minerals with a specific crystal structure, which can also describe synthetic materials engineered to possess the same structure. This structure is typically represented as ABX3, where ‘A’ and ‘B’ are metal cations, and ‘X’ is a non-metal anion. Perovskite materials exhibit high ionic conductivity, making them valuable for various energy-related applications, including fuel cells and solid electrolytes. Additionally, they display intriguing optical properties, such as strong light absorption and effective photoluminescence, making them promising candidates for applications in photovoltaics and optoelectronics [1,2,3].

PSCs, particularly those based on Methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3), have shown remarkable progress, with certified power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) now exceeding 27% [4,5,6,7,8,9]. While this rivals traditional silicon technologies [6], a critical barrier to their commercial viability is operational stability, which is intrinsically linked to ionic motion and recombination losses within the perovskite layer. Optimizing fundamental material properties, such as relative permittivity (εr), is essential to mitigate these losses and unlock the full potential of PSCs.

Numerical simulation tools like SCAPS-1D are vital for probing the internal physics of PSCs. While numerous studies have employed SCAPS-1D to optimize device architecture, including the selection of electron and hole transport layers [10,11,12,13,14], a critical and underexplored parameter is the relative permittivity (εr) of the perovskite absorber itself [15,16]. The permittivity governs the Coulombic interaction between charge carriers, directly influencing recombination rates and ionic transport dynamics, key factors limiting efficiency and stability. Most SCAPS-1D studies focus on typical J-V output, lacking a detailed analysis linking εr to these underlying electrochemical processes.

This work addresses this gap by employing SCAPS-1D simulations to systematically investigate the impact of the CH3NH3PbI3 layer’s relative permittivity (varying from 4 to 12) on device performance. Crucially, we move beyond standard current–voltage (J-V) analysis by integrating a novel simulation and analysis of complex impedance and electric modulus spectra. This dual approach allows us to deconvolute the distinct influences of εr on electronic recombination and ionic transport, providing deeper mechanistic insight that is rarely captured in conventional simulation studies. Our goal is to identify the optimal permittivity range that minimizes detrimental processes and to establish a more comprehensive framework for the electrochemical design of high-performance, stable PSCs. Relative permittivity, also known as dielectric constant, is a critical property that significantly influences the performance of solar cells. Although the dielectric constant of CH3NH3PbI3 has been widely reported in experimental studies, its fundamental and isolated impact on the internal charge dynamics of a solar cell remains less explored through simulation. In this work, we systematically vary the permittivity not to replicate a single experimental value, but to isolate its fundamental role in screening Coulomb interactions within the active layer. The primary novelty of this approach lies in using permittivity variation as a tool to trigger and deconvolve the hidden ionic and electronic dynamics via impedance and modulus analysis, a significant step beyond the standard J-V characterization prevalent in many simulation studies. This methodology provides unique insight into how permittivity governs the critical trade-off between recombination and ionic transport, which is essential for designing high-performance devices [17,18,19,20]. The study begins by detailing the fundamental principles behind solar cell operation and the role of relative permittivity in influencing the efficiency of these cells. By employing advanced simulation techniques, we successfully modeled the behavior of PSCs under a range of environmental and operational conditions, including variations in temperature, illumination intensity, and electrical load, allowing us to gain in-depth insights into their efficiency, degradation mechanisms, and overall stability, thereby gaining insights into the optimal relative permittivity values. Through these simulations, we can predict how changes in relative permittivity affect key performance metrics, such as Voc, JSC, and overall power conversion efficiency. These predictions are crucial for designing solar cells that are more efficient and for identifying potential improvements in cell materials and structures. Furthermore, our analysis includes a thorough examination of the electronic properties of perovskite materials, focusing on their dielectric constant and how it interacts with the cell’s architecture. This analysis not only helps in fine-tuning the solar cell performance but also in elucidating the physical processes that govern the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy. By optimizing the relative permittivity, we aim to enhance the operational stability and efficiency of PSCs, making them more viable for large-scale applications. This research contributes to the ongoing efforts in the field of renewable energy to develop more effective and sustainable solutions for energy production.

2. Method

2.1. Simulation Parameters Using SCAPS-1D

The simulations were performed using SCAPS-1D version 3.3.10; the simulation parameters were set to closely mimic standard test conditions (STC). The incident light power is standardized at 1000 W/m2 under the AM1.5G spectrum, with the operating point voltage at 0 V and a controlled temperature of 300 K. These conditions are crucial for ensuring the reproducibility and relevance of the simulation outcomes to real-world solar cell performance.

2.2. Device Structure Modeled

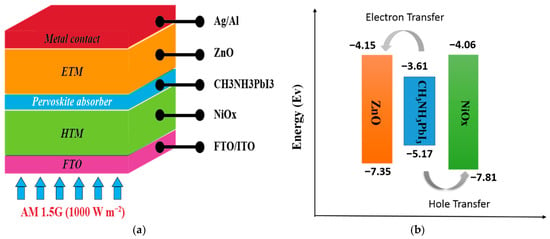

The device structure modeled in SCAPS-1D includes a complex layering of materials; each component plays a vital role in contributing to the overall functionality of the PSCs. The structure comprises an n-type hole transport layer (HTL) of NiOx and a p-type electron transport layer (ETL) of ZnO, which are used as the metal electrode, with CH3NH3PbI3 serving as the perovskite material sandwiched between them, ranging in relative permittivity from 4 to 12. (Ag/Al). FTO/ITO is used as the back contact (Figure 1). This configuration is essential for studying the interactions within the PSC, particularly the movement of electrons and holes, which are crucial for the device’s energy conversion efficiency. In addition, it is essential to provide a typical structure with an appropriate band diagram; the latter illustrates the energy levels of the materials involved. In the diagram, the Fermi level of the ETL is aligned with the conduction band of the perovskite, facilitating efficient electron transfer. The valence band of the perovskite aligns with the HTL, allowing for effective hole transfer. The conduction band of the ETL is higher in energy compared to the perovskite conduction band, while the valence band of the HTL is lower in energy than the perovskite valence band. This energy alignment is crucial for minimizing energy losses and enhancing the efficiency of the cell [21,22].

Figure 1.

Device structure model: (a) PSCs and (b) energy band diagram.

2.3. Simulation Steps

The SCAPS-1D simulation involves several steps tailored to optimize the PSC design. Initially, layer thicknesses are set as follows: FTO at 500 nm, ZnO at 80 nm, CH3NH3PbI3 at 700 nm, and NiOx at 80 nm. The material properties, such as bandgap and electron affinity, are precisely defined for each layer, ensuring accurate simulation of the photovoltaic behavior (Table 1) [23]. The simulation also incorporates advanced models for radiative and Auger recombination processes, with specific coefficients set for the perovskite absorption layer (PAL), enhancing the understanding of carrier dynamics within the cell (Table 2) [23].

Table 1.

Optical and electrical properties of the various layers employed in SCAPS-1D.

Table 2.

Different defect properties of different layers.

2.4. Impedance Spectroscopy Analysis of CH3NH3PbI3

Impedance spectroscopy (IS) is a powerful, non-destructive technique used to probe the electrochemical dynamics at interfaces and within the bulk of materials exhibiting mixed electronic and ionic behavior. In this study, IS were performed using SCAPS-1D to analyze the device’s frequency response. To ensure reproducibility and a valid interpretation of the impedance data, a standard methodology was applied: a small alternating current (AC) potential perturbation of weak amplitude was used across a frequency range of 0.01 Hz to 10 MHz. The impedance spectra were specifically simulated under operational conditions at a constant bias voltage equivalent to the maximum power point (MPP) of the J-V characteristic under standard AM1.5G illumination (1000 W/m2) [24,25].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. J-V Characteristics

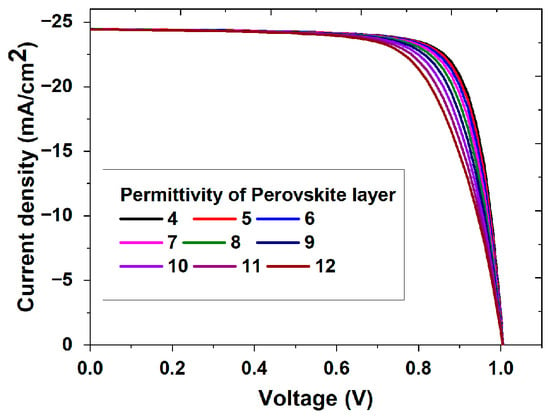

In order to investigate the influence of relative permittivity on PSCs, we have performed simulations on the structure depicted in Figure 1. The form of the heterojunction characteristics (Figure 2), measured under illumination, is closely associated with the dielectric constant of the CH3NH3PbI3 layer; i.e., the higher the relative permittivity, the more both the FF (%) and efficiency η (%) were improved.

Figure 2.

J-V curves for a stack FTO/ITO/NiOx/CH3NH3PbI3/ZnO/Ag/Al with different relative permittivity of CH3NH3PbI3 under illumination (1000 W/m2).

The parameters deduced from Figure 2, including JSC, open-circuit potential VOC, FF (%), and η (%), at different relative permittivity levels of CH3NH3PbI3 under illumination are reported in Figure 3. We observe that the efficiency and FF (%) decrease with increasing relative permittivity due to the increase in recombination electron–hole. On the other side, Voc and Jsc become constant along the range of relative permittivity.

Figure 3.

Effect of relative permittivity of CH3NH3PbI3 on PSCs (a) Voc, Jsc, and (b) FF (%) and η (%).

The analysis of Figure 3 reveals the impact of relative permittivity on CH3NH3PbI3 PSCs, specifically focusing on Voc, Jsc, FF (%), and η (%). The results indicate that both Voc and Jsc remain constant at approximately 1.05 V and 25 mA cm−2, respectively, across a permittivity range of 4 to 12, suggesting that these parameters are not significantly affected by changes in permittivity (Figure 3a). In contrast, the FF and η exhibit a noticeable decline with increasing permittivity. The FF decreases from around 78% to 70%, while efficiency drops from about 20% to 17%, implying that higher permittivity adversely impacts these aspects of the PSCs’ performance (Figure 3b). This trend aligns with literature findings: Wang et al. [26] reported that increased permittivity can enhance charge carrier recombination, thereby reducing FF and efficiency. Jarwal et al. [27] studied the impact of several device parameters, such as the density and thickness of defects in the perovskite layer, on solar cell performance. They simulated a PSC architecture (FTO/TiO2/CH3NH3PbI3/HTLs/Au) to optimize absorber layer thickness and defect density, achieving an η of 10.01% for MEH-PPV, 13.94% for PEDOT:PSS, 14.75% for P3HT, 15.42% for PQT, 15.74% for NPB, 17.08% for PTAA, and 17.11% for spiro-OMeTAD. The study shows that spiro-OMeTAD is the most promising HTL, with an η of 17.11%, a VOC of 1.10 V, a JSC of 20.772 mA cm−2, and an FF of 0.74%.

Strong recombination and trap-assisted recombination pathways result from a strong Coulomb attraction force between the electron and hole pairs. Therefore, it is favored in PSCs to lessen the attractiveness between mobile carriers. Reduced FF and η have been directly tied to the carrier loss brought on by recombination. In summary, the diminution of FF and η implies that a reduction in recombination strength could be afforded by using higher εr perovskite materials.

3.2. Complex Impedance Simulations

It has been noted that the device mechanisms are still unclear for OILH materials with mixed electronic–ionic conductivity compared with conventional all-inorganic materials [28,29]. Furthermore, the ionic conductivity gating the electronic motion generally obscures the explanation of the operation mechanism of PSCs. Thus, the ionic movement or ion/defect migration and resultant influence on device mechanism in PSCs should be fully elucidated for stable and highly efficient PSCs development.

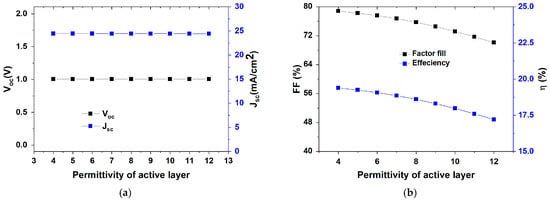

Figure 4 shows the simulation electrical impedance for various relative permittivity values ranging from 4 to 12. In the Nyquist diagram (Figure 4a), it is clear that the impedance spectra consist of a sizable semicircle, which is highly influenced by the permittivity of the active layer of CH3NH3PbI3. This shape of impedance spectra in the Nyquist diagram belongs to the responses usually encountered in solar systems, in which carrier transport is determined by diffusion–recombination. With an increase in the dielectric permittivity of the active layer, the semicircle’s diameter shrank.

Figure 4.

Impedance spectra with different relative permittivity of perovskite layer: (a) Nyquist diagram and (b) Bode diagram.

In the Bode diagram (Figure 4b), the variation in the real part showed two slope changes. This variance suggests the presence of two processes, and the modulus function will be examined as a result.

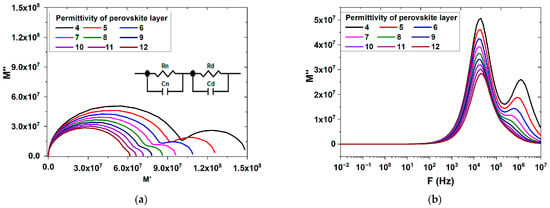

3.2.1. Complex Modulus Simulations

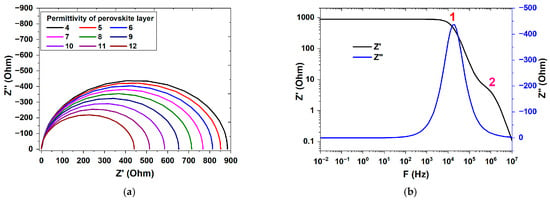

Figure 5 exhibits modulus spectra at various relative permittivity of perovskite layer, where Figure 5a shows M”–M’ to the variation in the real part and imaginary part in relative permittivity ranges of 4–12. The real axis intersection displays at the intercept the capacitance caused by recombination or ionic transport. Semicircular arcs at low and high frequencies (two relaxation processes) were detected for each sample. The small semicircular arcs at high frequencies are due to the effect of the recombination process. At low frequencies, the huge semicircular arcs correspond to the electrode processes’ effects on the ionic transport. Figure 5b depicts the imaginary part of electrical modulus, M” against the frequency in the relative permittivity order perovskite layer range from 4 to 12. It is clearly seen that similar behavior was observed. It is clearly observed from (Figure 5b) that M” versus frequency curves have two peaks at each value of relative permittivity; one of the peaks is in a low-frequency region and the other in a high-frequency region. It can be noticed that those peaks observed at low frequency move to the higher-frequency regions, and the peaks observed at higher frequencies move to the low-frequency region with increasing relative permittivity. We also noticed that at higher values of relative permittivity, both peaks overlapped.

Figure 5.

Modulus spectra with different relative permittivity of perovskite layer: (a) Nyquist diagram and (b) Bode diagram.

Impedance modeling of spectra with equivalent circuits is the best method to extract different electric and electronic parameters related to the performance of solar cells. Several authors [30,31,32,33] have studied the performance of solar cells using impedance spectroscopy, but they are limited to the analysis of impedance spectra, and consequently, a semicircle was observed in the impedance spectra; thus, they have used one block (R//C) to model this semicircle.

As we have shown in the modulus spectra (Figure 5), two processes exist, so for this reason, we have developed an equivalent circuit composed of two blocks (R2//C2) + (R1//C1).

The total complex impedance of the circuit described above can be expressed as follows:

where τ1 and τ2 are the relaxation times, ω is the angular frequency, R1 and R2 are the resistors, and C1 and C2 are the capacitors.

It is very usual to have the imaginary part (Z″) be at a maximum during the relaxation process; this can be explained with the equation below:

These expressions are obtainable from the derivative of the imaginary part (Z″) versus angular frequency (ω). The complex impedance (Z*) and the modulus (M*) are related by Equation (3):

Then, the real and imaginary parts of the electric modulus can be expressed as follows:

where C0, C1, and C2 are Capacitor; ω is the angular frequency; and R1 and R2 are resistors.

Similarly, the angular frequency (ω1 max) and (ω2 max) values can be calculated by differentiating the imaginary part (M″) in terms of angular frequency (ω). This allows us to obtain the very same value corresponding to real part (ω max) for every maximum found in the imaginary part M″.

Therefore, the previous equations give some explanation on why each maximum observed in the real-part evolution for both (Z″) and (M″) at low-frequency and high-frequency can be at the special frequency value (F max).

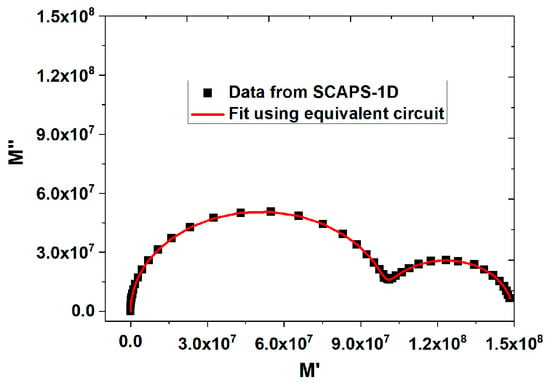

Consequently, important parameters that can be extracted after fitting with an equivalent circuit model include capacitances (C), resistances (R), and time constants (τ), corresponding to various contributions at both low and high frequencies.

To show the validity of the equivalent circuit, the fit of the modulus function in the Nyquist diagram for relative permittivity was 4 and was selected as a typical sample to show the fit. Figure 6 shows the best fit using an equivalent electrical circuit.

Figure 6.

Fit of modulus spectra at different relative permittivity of the perovskite layer.

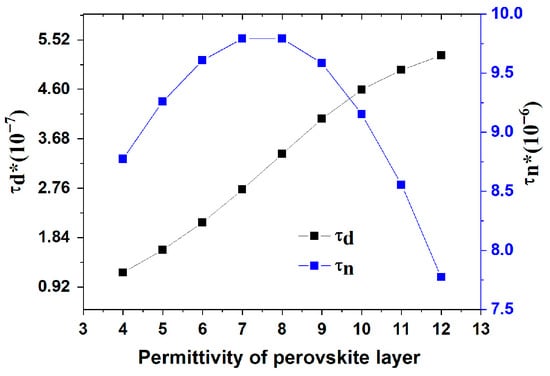

3.2.2. Analysis of Extracted Parameters from the Equivalent Electrical Circuit

In a PSC, the characterization and identification of the recombination and ionic transport mechanisms in thin-film solar cells have been an important challenge for the community [34,35,36]. The equivalent circuit model described contains two characteristic times related to the recombination τ1 (recombination time) and the ionic transport τ2 [33,37]. Figure 7 shows the dependence of both relation times deduced from the equivalent circuit on an increasing relative permittivity. We have observed that the recombination time, τ1, decreases with an increase in εr, indicating that the recombination rate increases. This enhanced recombination directly leads to the degradation of the solar cell’s performance, as observed in the reduction in FF and η. For the ionic transport time τ2, their evolution shows a peak at 7 of the relative permittivity value. Above this value, the ionic transport process is more dominant compared with the recombination process; this phenomenon generates a cell with low efficiency, as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 7.

Recombination time and ionic transport time versus relative permittivity.

The optimal relative permittivity was observed, which led to obtaining an efficiency of 18.86%, Jsc of 24.44 mA cm−2, open-circuit potential Voc 1.005 V, and an FF of 76.75%. These values have been improved compared with the values obtained in the work of Sazzadur Rahman et al. [7].

To translate the optimal relative permittivity identified in this simulation into a practical engineering strategy, the dielectric environment of the perovskite layer can be tailored through material design. A primary approach is cation engineering, where alloying the A-site (e.g., incorporating formamidinium (FA+) or cesium (Cs+) alongside methylammonium (MA+)) systematically tunes the material’s polarizability and effective permittivity. Alternatively, composite engineering, such as forming low-dimensional perovskite phases or incorporating dielectric additives into the bulk or at interfaces, can locally enhance charge screening and passivate defects. By targeting these synthesis routes, experimental efforts can rationally approach the optimal permittivity window, thereby mitigating recombination losses and advancing the development of high-performance PSCs.

4. Conclusions

This study used SCAPS-1D simulation to analyze the role of the perovskite layer’s relative permittivity (εr) in planar CH3NH3PbI3 solar cells. The results show a clear trade-off: while VOC and JSC remain stable, the FF and power conversion efficiency decrease as εr increases from 4 to 12. An optimal efficiency of 18.86% was identified for a specific permittivity value. More importantly, by integrating impedance spectroscopy analysis, we provided a novel mechanistic explanation for this trend. The deconvolution of the impedance spectra revealed that increasing εr simultaneously extends recombination time but also promotes unfavorable ionic transport dynamics beyond a critical point (εr = 7). This dual effect clarifies why simply maximizing permittivity is detrimental and establishes εr as a key parameter for balancing electronic and ionic processes in the perovskite absorber.

The primary scope of this work is to provide a theoretical and simulation-based framework linking a fundamental material property (εr) to the electrochemical performance of PSCs. To translate these findings into higher experimental device performance, future work must focus on material synthesis guided by this optimal εr target. This can be achieved through compositional engineering, such as A-site cation mixing or the incorporation of specific additives designed to precisely tune the dielectric constant of the perovskite film. Subsequent experimental validation should fabricate devices with these tailored materials and employ impedance spectroscopy to confirm the predicted suppression of ionic losses and recombination. This targeted approach, moving from simulation to controlled synthesis and characterization, offers a direct pathway to fabricating more efficient and stable PSCs.

Author Contributions

Methodology, I.S.; Software, Y.T., B.L. and R.M.; Validation, A.M.; Formal analysis, A.M. and E.G.C.; Investigation, A.M.; Data curation, Y.T. and E.H.C.; Writing—original draft, H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arif, H.; Tahir, M.; Sagir, M.; Alrobei, H.; Alzaid, M.; Ullah, S.; Hussien, M. Effect of potassium on the structural, electronic, and optical properties of CsSrF3 fluro perovskite: First-principles computation with GGA-PBE. Optik 2022, 259, 168741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Chahar, S.; Sharma, R. An extensive investigation of structural, electronic, and optical properties of inorganic perovskite Ca3AsCl3 for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications: A first-principles approach using Quantum ATK Tool. Solid State Commun. 2024, 390, 115623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Tahir, M.B.; Ahmed, B.; Dahshan, A.; Ali, H.E.; Sagir, M. DFT screening of Ga-dopped ScInO3 perovskite for optoelectronic and solar cell applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 161, 112054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Park, K.; Tan, S.; Vaynzof, Y.; Xue, J.; Diau, E.W.G.; Bawendi, M.G.; Lee, J.W.; Jeon, I. Perovskite solar cells. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, A.; Ogale, S.B.; Game, O.S. Architectural innovations in perovskite solar cells. Small 2025, 21, e2411355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.Z.; Anwar, H.; Wang, M. A comprehensive device modelling of perovskite solar cell with inorganic copper iodide as hole transport material. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2018, 33, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarwal, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Ratan, S.; Upadhyay, R.K.; Kumar, C.; Mukherjee, B.; Jit, S. Fabrication and TCAD validation of ambient air-processed ZnO NRs/CH3NH3PbI3/spiro-OMeTAD solar cells. Superlattices Microstruct. 2020, 143, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.; Kumar, M.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, M.; Yun, J.-H. Low cost and solution processible sandwiched CH3NH3PbI3-xClx based photodetector. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 99, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortadi, A.; El Hafidi, E.; Monkade, M.; El Moznine, R. Investigating the influence of absorber layer thickness on the performance of perovskite solar cells: A combined simulation and impedance spectroscopy study. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2024, 7, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouk, R.; Aguir, C.; Tala-Ighil, R.; Al-Hada, N.M.; Al-Asbahi, B.A.; Khalfaoui, M. Numerical simulation and optimal design of perovskite solar cell based on sensitized zinc oxide electron-transport layer. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Miah, S.; Marma, M.S.W.; Sabrina, T. Simulation based investigation of inverted planar perovskite solar cell with all metal oxide inorganic transport layers. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 7–9 February 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, K.R.; Gurung, S.; Bhattarai, B.K.; Soucase, B.M. Comparative study on MAPbI3 based solar cells using different electron transporting materials. Phys. Status Solidi C 2015, 13, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, A.S.; Fahsyar, P.N.A.; Ludin, N.A.; Burhan, I.; Mohamad, S. Device simulation of perovskite solar cells with molybdenum disulfide as active buffer layer. Bull. Electr. Eng. Informatics 2019, 8, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoui, Y.; Ez-Zahraouy, H.; Tahiri, N.; El Bounagui, O.; Ahmad, S.; Kazim, S. Performance analysis of MAPbI3 based perovskite solar cells employing diverse charge selective contacts: Simulation study. Sol. Energy 2019, 193, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovetto, A.; Huss-Hansen, M.K.; Hansen, O. How the relative permittivity of solar cell materials influences solar cell performance. Sol. Energy 2017, 149, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohri, S.; Madan, J.; Pandey, R. Augmenting CIGS solar cell efficiency through multiple grading profile analysis. J. Electron. Mater. 2023, 52, 6335–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, U.; Saha, S.K.; Pal, A.J. Fully-depleted pn-junction solar cells based on layers of Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) and copper-diffused AgInS2 ternary nanocrystals. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 124, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, S.; Oklobia, O.; Jones, S.; Lamb, D.; Kartopu, G.; Lu, D.; Xiong, G. Creating metal saturated growth in MOCVD for CdTe solar cells. J. Cryst. Growth 2023, 607, 127124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovetto, A.; Cazzaniga, A.; Ettlinger, R.B.; Schou, J.; Hansen, O. Optical properties and surface characterization of pulsed laser-deposited Cu2ZnSnS4 by spectroscopic ellipsometry. Thin Solid Film. 2014, 582, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crovetto, A.; Chen, R.; Ettlinger, R.B.; Cazzaniga, A.C.; Schou, J.; Persson, C.; Hansen, O. Dielectric function and double absorption onset of monoclinic Cu2SnS3: Origin of experimental features explained by first-principles calculations. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 154, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Fu, Q.; Guo, P.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Luo, W.; Zheng, Z. Ionic transport characteristics of large-size CsPbBr3 single crystals. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 115808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, X.; Cui, F.; Yue, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Tao, X. Anisotropic X-ray detection performance of melt-grown CsPbBr 3 single crystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 9153–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Meng, L.; Song, T.-B.; Guo, T.-F.; Yang, Y.; Chang, W.-H.; Hong, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Q. Improved air stability of perovskite solar cells via solution-processed metal oxide transport layers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailegnaw, B.; Sariciftci, N.S.; Scharber, M.C. Impedance spectroscopy of perovskite solar cells: Studying the dynamics of charge Carriers before and after continuous Operation. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 217, 2000291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Pandey, K.; Bhatt, V.; Kumar, M.; Kim, J. Critical aspects of impedance spectroscopy in silicon solar cell characterization: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1562–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lin, Z.; Ouyang, X. Tailoring the permittivity of passivated dyes to achieve stable and efficient perovskite solar cells with modulated defects. Mater. Today Adv. 2024, 22, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarwal, D.K.; Dubey, C.; Baral, K.; Bera, A.; Rawat, G. Comparative analysis and performance optimization of low-cost solution-processed hybrid perovskite-based solar cells with different organic HTLs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 5012–5020. [Google Scholar]

- Musiienko, A.; Moravec, P.; Grill, R.; Praus, P.; Vasylchenko, I.; Pekarek, J.; Tisdale, J.; Ridzonova, K.; Belas, E.; Landová, L. Deep levels, charge transport and mixed conductivity in organometallic halide perovskites. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1413–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpiroz, J.M.; Mosconi, E.; Bisquert, J.; De Angelis, F.; Science, E. Defect migration in methylammonium lead iodide and its role in perovskite solar cell operation. Energy 2015, 8, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.S.; Kumar, L.; Sharma, V.K. Solving the equivalent circuit of a planar heterojunction perovskite solar cell using Lambert W-function. Solid State Commun. 2021, 337, 114439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Mary, D.M. A novel chaotic-driven Tuna Swarm Optimizer with Newton-Raphson method for parameter identification of three-diode equivalent circuit model of solar photovoltaic cells/modules. Optik 2022, 264, 169379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Huang, G.; Xu, C. An explicit method to extract fitting parameters in lumped-parameter equivalent circuit model of industrial solar cells. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2188–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y. The measurements and determinants of patent technological value: Lifetime, strength, breadth, and dispersion from the technology diffusion perspective. J. Informetr. 2023, 17, 101370. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, C.A.; Alvarez, A.O.; Chivrony, V.S.; Das, C.; Rai, M.; Saliba, M. Overcoming ionic migration in perovskite solar cells through alkali metals. Joule 2024, 8, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdinç, A.K.; Mutlu, A.; Gültekin, B.; Zafer, C. Impact of Li passivation on recombination and charge transfer at the TiO2/perovskite interface. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2024, 55, 665–678. [Google Scholar]

- Mortadi, A.; Nasrellah, H.; Monkade, M.; El Moznine, R. Investigation of bandgap grading on performances of perovskite solar cell using SCAPS-1D and impedance spectroscopy. Sol. Energy Adv. 2024, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xu, S. Effective lifetimes of minority carriers in time-resolved photocurrent and photoluminescence of a doped semiconductor: Modelling of a GaInP solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 193, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).