Abstract

This study presents an optimization-driven design of a wireless communications network to continuously transmit environmental variables—temperature, humidity, weight, and water usage—in poultry farms. The reference site is a four-shed facility in Quito, Ecuador (each shed ) with a data center located from the sheds. Starting from a calibrated log-distance path-loss model, coverage is declared when the received power exceeds the receiver sensitivity of the selected technology. Gateway placement is cast as a mixed-integer optimization that minimizes deployment cost while meeting target coverage and per-gateway capacity; a capacity-aware greedy heuristic provides a robust fallback when exact solvers stall or instances become too large for interactive use. Sensing instruments are Tekon devices using the Tinymesh protocol (IEEE 802.15.4g), selected for low-power operation and suitability for elongated farm layouts. Model parameters and technology presets inform a pre-optimization sizing step—based on range and coverage probability—that seeds candidate gateway locations. The pipeline integrates MATLAB R2024b and LpSolve 5.5.2.0 for the optimization core, Radio Mobile for network-coverage simulations, and Wireshark for on-air packet analysis and verification. On the four-shed case, the algorithm identifies the number and positions of gateways that maximize coverage probability within capacity limits, reducing infrastructure while enabling continuous monitoring. The final layout derived from simulation was implemented onsite, and end-to-end tests confirmed correct operation and data delivery to the farm’s data center. By combining technology-aware modeling, optimization, and field validation, the work provides a practical blueprint to right-size wireless infrastructure for agricultural monitoring. Quantitatively, the optimization couples coverage with capacity and scales with the number of endpoints M and candidate sites N (binaries ). On the four-shed case, the planner serves 72 environmental endpoints and 41 physical-variable endpoints while keeping the gateway count fixed and reducing the required link ports from 16 to 4 and from 16 to 6, respectively, corresponding to optimization gains of up to 82% and 70% versus dense baseline plans. Definitions and a measurement plan for packet delivery ratio (PDR), one-way latency, throughput, and energy per delivered sample are included; detailed long-term numerical results for these metrics are left for future work, since the present implementation was validated through short-term acceptance tests.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Problem Statement

Production poultry houses present dense, multipath-rich, and humidity-prone radio environments with metal meshes and wet surfaces that attenuate and scatter signals. Wireless monitoring must therefore be engineered from first principles to meet link-budget and capacity targets with predictable latency while minimizing wiring and civil works. This paper frames the design as a communications-centric planning problem for a real farm and treats coverage and capacity jointly.

1.2. Related Work and Positioning

Industrial and agricultural IoT deployments commonly adopt link-budget screening and heuristic placement rules, but many reports do not couple coverage with capacity or cost in a single optimization [1,2,3,4]. Mixed-integer programming has been used to place access points and gateways [5,6,7], yet practical papers often stop short of providing executable tools and farm-specific calibration. The present study contributes an integrated flow that (i) calibrates a log-distance path-loss model to the site, (ii) screens coverability against receiver sensitivity, and (iii) solves a capacity-constrained MILP with a cost-aware greedy fallback, with code and plots to aid replication.

1.3. Contributions

The manuscript’s contributions are engineering-oriented rather than algorithmically novel:

- A calibrated path-loss model for the studied farm, converted to a binary coverability matrix against sensitivity/margin and used as physics input to optimization.

- A capacity-aware MILP for gateway activation and user-to-gateway assignment, with an explainable greedy fallback for solver timeouts or large instances.

- A documented toolchain (MATLAB, LpSolve, Radio Mobile, Wireshark) and companion functions for running the optimization and producing diagnostic plots.

- A field deployment in the target facility with end-to-end packet capture, closing the loop from model to practice.

Automation in poultry production is often discussed in terms of animal husbandry, yet the binding constraint in practice is the communications substrate that moves telemetry and control data reliably and on time. In emerging markets, production sites typically span elongated metal structures with high moisture and variable clutter, creating non-line-of-sight (NLOS) links, pronounced multipath, and frequency-selective fading. In tropical regions, additional ventilation equipment and water lines introduce reflective/absorptive elements that further distort the radio channel. Under these conditions, the performance of a monitoring system is determined less by the sensing hardware than by the ability of the wireless network to meet link-budget and capacity targets with predictable latency. Wireless technologies are attractive because they avoid the civil and electrical works required by structured cabling across long sheds; however, ad hoc deployments frequently suffer from insufficient coverage margins, congestion, and limited scalability. Reported case studies in agribusiness often demonstrate prototypes based on Zigbee, LoRa, or cellular links, but they rarely provide medium-/long-term performance results, site dimensions, or repeatable placement rules. Without communications-centric engineering—coverage planning, interference management, and capacity dimensioning—operators face low packet delivery ratios (PDR), sporadic delays, and blind spots that degrade process visibility and, ultimately, operational outcomes. This article addresses the problem from a communications standpoint. It formulates gateway placement and technology selection as a constrained optimization problem that balances three key objectives: (i) Coverage—ensuring sufficient received power and link margin for every transmitter under realistic propagation losses; (ii) Capacity—respecting per-gateway association limits and airtime constraints to sustain aggregate traffic; and (iii) Reliability/latency—maintaining target packet delivery and delay bounds under expected interference and load. The approach integrates a calibrated path-loss model with mixed-integer optimization to compute the minimum-cost set and positions of link ports (gateways) that satisfy coverage and capacity constraints. A capacity-aware greedy heuristic provides a robust fallback when exact solvers are unavailable or time-limited. To validate the communications design, the study complements the optimization with radio-coverage simulation and packet-level analysis. Coverage maps quantify received power and predicted availability across the facility, while protocol traces characterize end-to-end performance (PDR, latency, retry rates) under realistic traffic patterns. The result is a technology-agnostic, repeatable methodology that right-sizes wireless infrastructure for telemetry workloads in elongated, cluttered industrial spaces—poultry warehouses being a representative instance—without relying on bespoke hardware or ad hoc placement rules.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Propagation and Coverage Model

The wireless links are modeled with a log-distance path-loss model with optional fixed and distributed losses [8,9]. The received power at distance d (in meters) is

where is the carrier frequency in MHz, n is the environment loss exponent, is a fixed attenuation term (e.g., first wall/facade, connectors), and is a distributed loss per meter (clutter). Coverage holds if for the target modulation and data rate. These definitions and recommended parameter ranges are taken from the internal wireless parameter manual used in this study. In practice, small-scale multipath fading and fast temporal variations are not modeled as an explicit stochastic process in this work; instead, their average effect is absorbed into the calibrated parameters and into a conservative link margin on the received-power threshold. This level of abstraction is common in engineering design tools and is adequate for static gateway placement and capacity dimensioning in the considered farm.

2.2. Optimization Model

Given M candidate access points (APs) and N user locations, binary variables indicate whether AP i is installed (active), indicate whether user j is covered, and assign covered users to active APs. Let denote physical coverability under (1) (i.e., iff ). With per-AP costs , required coverage index , and a per-AP capacity , the mixed-integer linear program (MILP) used in this work is

An exhaustive search over all subsets of candidate sites would scale exponentially with M and N and is therefore intractable even for moderate grids. Instead, the implementation solves (2)–(7) with intlinprog when available, providing exact solutions for small- and medium-sized instances. For larger candidate grids or in interactive use—where practitioners iteratively adjust sensor or gateway locations and re-run the optimization—the number of binary variables can make the MILP slow or cause the solver to stall on standard engineering workstations. In those cases, the tool reverts to a fast capacity-aware greedy heuristic, which returns a feasible solution within seconds and is therefore suitable as an operational fallback.

2.3. Parameterization and Technologies

Table 1 summarizes the typical (not regulatory-maximum) presets used for the candidate technologies. These presets feed Equation (1) and the constraints (5) and (6).

Table 1.

Typical presets by technology (frequency, transmit power , receiver sensitivity , and nominal per-AP user capacity ). Values follow the internal manual used in this study.

Although the case study focuses on Tekon devices using the Tinymesh (IEEE 802.15.4g) protocol, the optimization framework itself is technology-agnostic and can also be parameterized for LPWAN technologies such as LoRaWAN or NB-IoT by changing , , f, and . In the evaluated poultry farm, link distances are on the order of tens to a few hundred meters, the traffic pattern is low-duty-cycle telemetry, and the operator requires fully local control without dependence on a mobile network. Under these constraints, a 802.15.4g/Tinymesh solution offers sufficient link budget and capacity while simplifying deployment and channel planning. LoRaWAN or NB-IoT could be attractive for longer-range or multi-farm scenarios, but they introduce different regulatory constraints, subscription models, and interference or duty-cycle regimes that fall outside the scope of this particular deployment.

2.4. Theoretical Coverage Radii (Sizing Check)

For the environments considered in agricultural deployments (open fields and farming buildings), the menu tool computes a pre-optimization theoretical radius r by solving for d with the current parameters. Table 2 reports these indicative radii for four representative environments used in this study. They serve only as sizing checks; actual coverage depends on EIRP limits, device implementations, and materials.

Table 2.

Indicative coverage radii r (meters) by technology and environment (from the internal manual).

2.5. Implementation and Reproducibility

Two companion MATLAB functions are provided: optimize_wireless_map (solver/plotter) and optimize_wireless_map_menu (interactive front-end). The menu lets the analyst (i) select the technology, (ii) set environment parameters or georeference the map to meters, (iii) preview the theoretical radius, (iv) place candidate APs and users, (v) optionally override , , or within safe ranges, and (vi) run the optimization that produces two diagnostic plots (all AP circles and active AP circles). In the four-shed case studies reported here (72 and 41 transmitters with up to a few dozen candidate sites), intlinprog typically converged in under a minute on a standard laptop, whereas the greedy heuristic produced solutions in under one second even when the candidate grid was densified. This runtime gap motivates the inclusion of the heuristic in the interactive menu, where practitioners frequently adjust sensor or gateway locations and re-run the planning step.

2.6. Regulatory and Calibration Notes

The EIRP and sensitivity values in Table 1 and Table 2 are planning presets. Projects must verify local EIRP limits (e.g., ETSI and FCC rules for 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz ranges) and, when possible, calibrate from on-site RSSI measurements following the manual’s guide. In the evaluated farm, path-loss parameters were tuned against short calibration measurements to account for the combined effects of metallic structures, plastic walls, humidity, and clutter inside the sheds. The resulting model is therefore an engineering approximation that captures the dominant large-scale effects relevant for gateway placement, while fine-grain temporal variations remain to be characterized in longer-term campaigns.

In intensive poultry production, productive performance and animal welfare depend on maintaining appropriate environmental conditions, particularly temperature, relative humidity, airspeed, litter quality, and gas concentrations such as ammonia and CO2 [10,11,12,13]. Water availability and temperature also play a key role, as they directly influence consumption patterns and, consequently, growth and health [1]. These variables must be monitored continuously and with sufficient spatial resolution in the sheds to ensure that the animals remain within recommended comfort ranges at each production stage.

From a design perspective, intensive facilities generate substantial sensible and latent heat loads, as well as moisture and gas emissions. For example, a flock of 20,000 birds with an average weight of 1.8 kg can introduce on the order of 200,000 BTU/h, while the same number of birds at 3.6 kg may produce around 800,000 BTU/h, in addition to several thousand liters of water per day. CO2 concentration, originating from respiration and combustion-based heating, should typically remain below 2000 ppm to avoid health issues for both animals and workers [14]. To capture representative conditions, temperature, humidity, gas, and other environmental probes are usually installed at the animals’ head height and adjusted as their size changes, a process that can be progressively automated with suitable mechanical design and actuation [15,16]. In the optimization framework, these environmental and production requirements determine the number and spatial distribution of sensing nodes and mandatory coverage points; they enter the model as the transmitter set and coverage constraints, not as explicit optimization variables.

Within this context, IoT technologies provide a practical framework to instrument the sheds with distributed sensing and communication capabilities [10] propose a low-cost device that measures temperature, relative humidity, ammonia concentration, and luminosity, transmitting data over Wi-Fi so that it can be stored, processed, and visualized on the internet. Their results show that the proposed hardware and software correlate well (0.90 or above) with conventional commercial instruments, demonstrating that cost-effective IoT nodes can provide sufficiently accurate measurements for farm monitoring and control, and that similar architectures can be replicated in other productive sectors.

According to [11], meeting the increasing demand for animal products under resource constraints requires intelligent management systems capable of real-time data acquisition, analysis, and intervention. They outline an IoT-based infrastructure composed of (i) hardware nodes for environmental and behavior sensing, (ii) software modules for data analysis, decision support, and control, and (iii) operator interfaces for configuration and supervision. Although their work focuses on conceptual architecture and does not present detailed network topologies or hardware layouts, it provides a reference framework that guides the design of concrete sensing and communication solutions in smart farms [17] show how IoT and AI can be tightly integrated to implement autonomous, data-driven environmental monitoring. Their system is based on microcontroller nodes with wireless sensors and an NVIDIA Jetson Nano platform acting as an edge-computing unit. Multiple environmental sensors are connected via Wi-Fi, and the collected data are processed using a gated recurrent unit (GRU) algorithm to ensure data quality and predict future values. This pipeline, from distributed sensing and wireless transmission to local AI-based analytics, is directly applicable to advanced monitoring architectures in agricultural environments.

In [12], the authors design and implement an intelligent farm monitoring system that measures temperature, humidity, light intensity, and water level, and integrates an automated conveyor belt for waste collection. The system is built around Arduino-based devices, Wi-Fi connectivity, a Matlab-based graphical user interface, and a spreadsheet-based database, and includes reference tables for ideal temperature and humidity ranges by production stage. They present both the overall architecture and a working prototype, illustrating how widely available microcontrollers, standard wireless links, and simple software tools can be orchestrated into a complete monitoring solution.

The work in [13] presents a wireless sensor network for environmental monitoring and control based on temperature and humidity sensors, as well as an electronic nose (e-nose) to detect harmful gases. The sensor nodes communicate using the ZigBee protocol with a dsPIC33 microcontroller acting as a master node. The aggregated data are transmitted to a remote server via GPRS and also sent to the operator via SMS, while climate control is implemented using fuzzy logic and PID algorithms. The article documents the architecture, communication stack, and control strategies, providing a useful reference for distributed sensing and actuation in intensive livestock facilities.

The communication and monitoring system for the Pofasa farm will be dimensioned according to the company’s operational requirements and the physical layout of the facilities. The optimal location of wireless link ports in each shed and the position of the main monitoring center will be determined considering coverage, link budget, and installation constraints. Figure 1 shows the farm layout, consisting of four sheds, each measuring 120 m × 12 m. The production office, located 50 m from the first shed, will function as the local data aggregation point, while the administrative center, 200 m from the production office, will host higher-level management and data services. The sheds will be built with a metal structure, and the sides and internal divisions will be made of plastic, materials that influence RF propagation and must be incorporated into the propagation and coverage analysis.

Figure 1.

Location of the Pofasa Farm. Taken from Google Maps, latitude: 0.0067333, longitude: −78.4361489, elevation: 169 m.

Based on the environmental requirements and load estimates, the proposed system includes a set of distributed sensors and meters to capture the main process variables in each shed and in common services. Environmental nodes will integrate temperature, humidity, and gas sensors installed at representative heights and connected to Wi-Fi or ZigBee transceivers, depending on the network segment. Water consumption will be monitored through a flow transmitter in each shed and a general flow meter for auxiliary services, enabling daily recording of consumption and early detection of leaks or supply anomalies [1]. In addition, load cells installed in feed hoppers will track feed availability and consumption per shed. All measurements will be transmitted to the production office and then to the administrative center, where they can be stored, analyzed, and used to drive local or remote control actions. The resulting set of sensor and meter positions defines the transmitter coordinate set used in the optimization model described in Section 2.2 and Section 2.5.

Device characteristics. Instead of listing vendor-specific specifications in a table, this paper cites representative ranges for sensing nodes used in poultry houses (temperature/humidity, CO2, ammonia, and particulate matter) from prior deployments and reviews [17,18,19]. These sources report operating ranges consistent with the devices used on-site and are sufficient for reproducing the communications planning.

Wireless devices manufactured by Tekon work with the Tinymesh protocol to enable communication and intelligent metering across a range of applications, including public lighting, IoT, and industrial applications. This protocol offers a robust wireless infrastructure solution that exhibits good performance in remote monitoring applications, information collection, and control while adhering to the specifications for each country and providing high power options in compliance with IEEE 802.15.4.g standards.

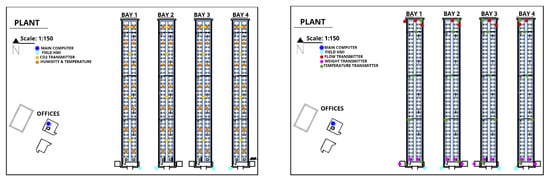

Figure 2 shows the location of the transmitters for measuring physical variables.

Figure 2.

Location of the transmitters for measuring physical variables.

In the market, manufacturers such as Tinymesh and Radiocraft provide radiocommunication solutions. The 802.15.4.g standard is designed to transmit energy and data rate data efficiently, ranging from 1 Kbit/s to several Mbits/s. According to [8], the standard supports various connection topologies such as star, mesh, or point-to-point, depending on the design and application.

2.7. Problem Formulation and Design Variables

In wireless network design, engineering decisions revolve around capacity, coverage range, and topology [20,21,22,23]. A clear objective is required—e.g., minimizing the number of link ports (gateways) or the total deployment cost—subject to meeting a target coverage level. The key design levers are the transmit power, access-point (AP) locations, operating channel, and effective coverage radius (or, equivalently, the link-budget threshold).

Let be the set of transmitters (environmental sensors), each located at known coordinates , and let be the set of candidate sites where a link port (gateway or repeater) may be installed, with coordinates . The planning parameter denotes the required coverage ratio. In the simplest range-based surrogate, a transmitter is coverable by site i if its Euclidean distance is within a planning radius R; in the link-budget version used in this paper, the same binary notion is derived from the path-loss model and a sensitivity threshold.

We define the binary coverability matrix

The decision variables are:

2.7.1. Coverage Linking

A transmitter is covered only if it can be assigned to at least one active candidate site that is physically coverable:

Equivalently, with explicit assignments: , , and .

2.7.2. Coverage Requirement

The design must cover at least a fraction of transmitters:

2.7.3. Objective

When all sites have equal cost, the objective reduces to minimizing the number of link ports:

If site costs differ due to power/backhaul constraints, replace the objective by .

2.8. Metrics and Definitions

To avoid ambiguity in the results, the paper uses the following definitions.

Number of Gateways (). The count of distinct gateway devices activated by the optimizer (variables ). A gateway has one radio and one backhaul interface.

Optimal Number of Ports (). The aggregated number of sensor-side link ports required across the activated gateways (e.g., serial or I/O interfaces on link-port concentrators). It is not a gateway count; a single gateway may expose multiple ports.

Optimization Percentage (). The fractional reduction versus a baseline design that activates every candidate site or a practitioner’s initial plan:

Unless otherwise stated, the baseline is the densest candidate-grid plan that meets coverage and capacity (upper-bounded by the number of candidate sites). This definition makes the optimization percentage independent of the absolute farm size and allows fair comparison across scenarios with different transmitter densities or candidate grids, as long as the same baseline criterion is applied.

Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR). The ratio between the number of application-layer packets received at the data center and the number transmitted by endpoints over a window. In the on-site tests it is estimated from Wireshark captures by counting end-to-end messages.

Latency. The one-way delay between packet emission at the endpoint and arrival at the collection server, measured by timestamping at both ends or by pairing request/acknowledgment frames when available.

Throughput. The average useful payload rate per endpoint and per gateway (bytes/s), estimated from capture logs.

Energy per delivered sample. Joules consumed in sensing, processing, and transmission per successfully delivered telemetry sample. When only radio is instrumented, it is estimated from the radio’s current profile, duty cycle (time-on-air), and supply voltage.

2.9. Coordinate Acquisition and Candidate Generation

The transmitter coordinates are obtained from the site plan by scaling the background image and placing points at the intended sensor locations using MATLAB. Candidate gateway sites are generated from feasible mounting positions (e.g., structural columns, utility corridors) and stored as pairs. The coverability matrix is computed either from the planning radius (for quick sizing) or from the calibrated link-budget (preferred). The mixed-integer program (8)–(10) is then solved with LpSolve; if the solver is unavailable or time-limited, a capacity-aware greedy heuristic (Improved Algorithm) is applied as a fallback to select sites with the largest gain in new coverable transmitters per added gateway.

The result is the minimum set of gateways and their coordinates, together with the assignment of each transmitter to a serving site. In our four-shed layout, this process identifies both the number and the positions of gateways required to achieve the target coverage within the planning constraints, decoupling the solution from the mere count of sheds and tying it instead to sensor density, geometry, and radio conditions. The same procedure can be applied to larger or differently shaped facilities by updating the transmitter coordinates, the candidate-site set and the calibrated propagation parameters, without modifying the underlying optimization model or software.

Improved Algorithm. Communications-centric gateway placement and sizing

Meaning of “improved”. Here, “improved” denotes a practical enhancement over a naive greedy set-cover. The score that selects the next site trades off the newly covered endpoints against per-gateway capacity and optional site cost , and it preserves feasibility by design (unique assignments, capacity, and coverability), which makes the heuristic a robust fallback when exact solvers time out or are unavailable.

Inputs:

- Transmitter (user) coordinates: .

- Candidate gateway sites: .

- Technology/propagation parameters: frequency f, path-loss exponent n, fixed loss , distributed loss , transmit power , receiver sensitivity , target coverage ratio , per-gateway capacity , gateway cost (optional).

- (Optional) link margin or a PDR target mapped to a margin.

Precomputation (physics → coverability):

- For all , compute distances .

- Path-loss: .

- Received power: .

- Coverability: (set if unused).

Decision variables maintained by the heuristic:

- : activate/install gateway at site j.

- : assign user i to gateway j.

- : user i is covered (assigned to an active gateway).

Greedy site-selection procedure:

- Initialize and for all j and i.

- While :

- (a)

- For each candidate site j with residual capacity, compute the gainwith if costs are not differentiated.

- (b)

- Select . If , stop (coverage target infeasible with given sites/parameters).

- (c)

- Activate by setting and assign up to new users to it (set and for the selected users).

- Return the set of active gateways , the assignments , and the achieved coverage .

3. Results

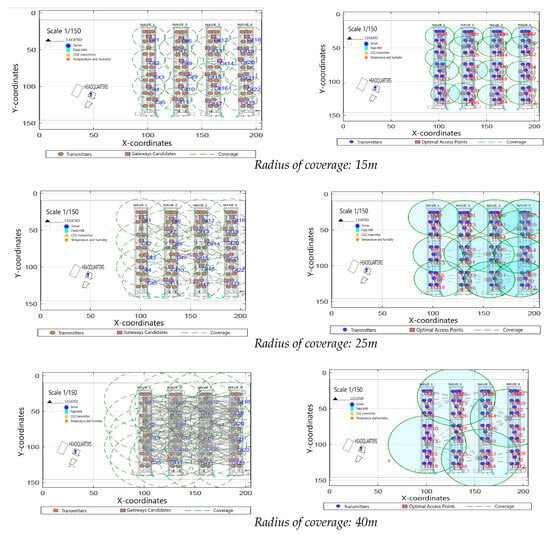

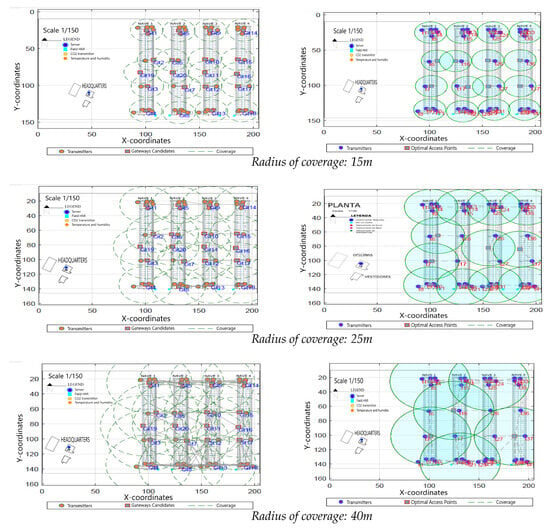

The optimization of gateways in Matlab is illustrated in Figure 3. Four gateway devices were employed to cover the entire farm, ensuring that 100% of the transmitters and the total area of the installation were covered. The results indicate that the optimization approach is effective for achieving comprehensive farm coverage using a minimal number of gateway devices and that the placement is driven by the geometry of the sheds and sensor distribution rather than by ad hoc rules.

Figure 3.

Coverage layouts for different design radii.

Table 3 presents the parameters considered and the results obtained using 72 transmitters with different coverage radius. As the planning radius increases from 15 m to 45 m, the optimizer keeps the same number of gateways but reduces the number of active ports from 16 to 4, increasing the optimization percentage from 30% to 82%. This illustrates how modest increases in effective coverage radius per gateway can translate into tangible savings in link-port hardware for the same sensor density.

Table 3.

Optimization for Environmental Variables.

The physical variable transmission endpoints are optimized in Figure 4 using Matlab. The figure shows that the gateway layout remains compact even when the design radius changes, while preserving coverage of all physical-variable endpoints.

Figure 4.

Coverage layouts for different design radii.

Table 4 provides an overview of the parameters considered and the results obtained with 41 transmitters, covering a range of 40 m, and employing six devices to cover the entire farm. Increasing the planning radius from 15 m to 45 m reduces the number of active ports from 16 to 6 and raises the optimization percentage from 20% to 70%, which again highlights the trade-off between gateway density, port utilization, and coverage radius.

Table 4.

Optimization for Physical Variables.

Table 5 provides precise coordinates of the access points, aiding in the detailed mapping and spatial analysis of these locations. Here is an overview of the data:

Table 5.

Geographical location of transmitters.

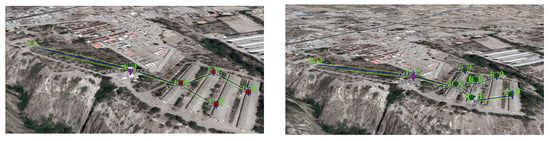

Figure 5 illustrates the geographic location of devices and the established radio links as simulated in Radio Mobile.

Figure 5.

Radio links simulated in Radio Mobile.

As in Table 6, the Fresnel zone was computed at 15 m antenna height; this parameter can be tuned for site constraints as long as clearance and margins are respected. With 0 dBm transmit power, these links are predicted to be feasible while supporting energy efficiency. The table links the parameters configured in Radio Mobile for the simulation, including the transmit power, frequency, antenna gain, and height for both the transmitter and receiver, as well as environmental factors such as terrain type and clutter loss.

Table 6.

Parameters of radio links.

Table 7 reports point-to-point links showing feasible transmission for the listed distances. Antennas were modeled at 15 m to visualize the Fresnel zone; height can be reduced if a safe link margin is preserved. With a transmit power of 0 dBm, the links are optimal in these cases, which also favors energy saving. The table summarizes the results of the radio link simulation environmental variables in Radio Mobile, presenting the calculated signal strengths, path losses, and overall link performance metrics. In all cases, the received levels exceed the −100 dBm sensitivity by at least 17.5 dB (relative reception), providing comfortable fade margins for the planned links.

Table 7.

Radio Mobile simulation results for Environmental Gateways (point-to-point).

Table 8 summarizes the results of the radio link simulation physical variables in Radio Mobile, presenting the calculated signal strengths, path losses, and overall link performance metrics. As in the environmental case, all links maintain a positive margin over the sensitivity threshold, which supports the feasibility of the planned topology for the physical-variable gateways.

Table 8.

Radio Mobile simulation results for Gateways of Physical Variables (point-to-point).

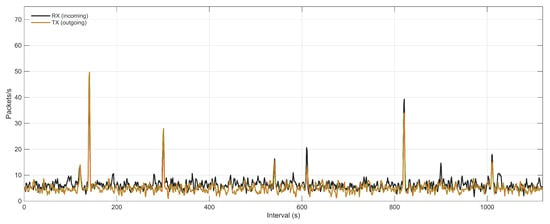

The researchers employed Wireshark software to conduct packet traffic analysis in their study. Figure 6 depicts the packets transmitted across the radio links. In the deployed system, the captures confirmed that the planned links were active and that application-layer packets traversed the designed paths without observable loss during the measurement windows, which is consistent with the margins reported in Table 7 and Table 8. These measurements correspond to short-term acceptance tests focused on validating the installation and the consistency between the planned and realized links; a longer-term statistical characterization of PDR, latency and energy consumption across multiple production cycles is left as future work.

Figure 6.

Wireshark packet trace during end-to-end test (snapshot).

By applying an optimization method, we have significantly reduced the need for gateways. Despite the initial random starting point, this technique allows for precise determination of the optimal locations for link ports based on the model and previous equipment placement within the farm. This is critical due to the uncertainty of space availability caused by other equipment, such as heating or air conditioning systems. The simulated network effectively establishes link conditions, eliminating the need for expensive testing on a real network with all equipment requirements. Verification of links and network traffic can be achieved with just two or three devices, and data can be retransmitted using repeaters. Coverage ranges are adjustable, as long as manufacturer conditions are adhered to. It is even possible to establish links over long distances, albeit with certain restrictions, such as line of sight and maximum transmission power. For Tekon devices, a master device, such as a PLC or Industrial Computer, is essential for system control. HMIs can also be added with the same protocol or with converters as needed.

In terms of interference, the traffic pattern is low-duty-cycle telemetry, and the sheds operate on orthogonal channels in the deployed configuration. Under these conditions, the links are primarily noise-limited, and interference between gateways is mitigated through static channel planning rather than explicit interference optimization. The high received-power margins and the Wireshark traces provide practical validation that the planned topology sustains the required PDR in this operating regime.

4. Discussion

The communications-centric optimization substantially reduces the number of gateways while preserving coverage and capacity targets. Instead of relying on ad hoc, radius-based placement or exhaustive field trials, the model integrates site geometry, link budgets, and per-gateway capacity into a single decision problem. Even when initial candidate locations are seeded from prior equipment layouts or operational constraints (e.g., heaters, ventilation, feeders), the solver converges to gateway positions that maximize useful coverage per unit cost. This is particularly valuable in elongated, cluttered environments where line-of-sight is partial and steel structures induce multipath and shadowing.

The simulated network provides a reliable proxy for link feasibility and aggregate performance before installation. Received-power maps and assignment overlays reveal blind spots and over-coverage, while packet-level emulation bounds expected delivery ratios and delay under typical reporting intervals. This reduces on-site iteration to a small, instrumented pilot: two or three devices suffice to confirm calibration of the propagation parameters and validate traffic assumptions. When necessary, repeaters can extend coverage; however, multi-hop paths should be used judiciously because each hop consumes airtime, increases latency, and tightens duty-cycle constraints, which may reduce effective capacity at the gateway. Because the telemetry load is low and sheds operate on orthogonal channels, the links are predominantly noise-limited rather than interference-limited in the evaluated deployment, which aligns with the positive margins and successful packet captures observed in practice.

Coverage ranges are adjustable within the manufacturer’s limits on transmit power and receiver sensitivity and within applicable regulations. Long-distance links are feasible when line-of-sight is available and interference is controlled, but the resulting designs must respect maximum EIRP, channel bandwidth, and coexistence policies. In the evaluated setup, Tekon devices using Tinymesh integrate cleanly with a supervisory master (PLC or industrial computer), and HMIs can be added either via the native protocol or through protocol converters, enabling end-to-end observability without modifying the RF layer.

Sensitivity analyses indicate that the solution is robust to moderate variations in the path-loss exponent and fixed loss terms; nonetheless, site-specific calibration (e.g., short RSSI surveys) improves confidence in marginal areas near the coverage boundary. Capacity-wise, enforcing per-gateway association limits and typical reporting schedules prevents contention-driven degradation at higher node counts. Remaining limitations of the present study include the simplified treatment of interference in the planning stage (handled via channel separation rather than explicit interference coupling in the optimization), the assumption of stationary sensors and traffic patterns, the reliance on a fixed catalog of candidate sites, and the fact that energy consumption and network lifetime are not yet explicit optimization objectives. Moreover, experimental validation has been carried out in a single farm and climatic condition with short-term measurement windows. Future work will extend the model to include channel assignment and interference-aware constraints, incorporate energy-aware metrics and adaptive reporting schemes, and validate the methodology in larger farms and different environments.

5. Conclusions

By integrating wireless transmitters across the facility, the system enables real-time monitoring and scales with minimal infrastructure changes. The equipment employed has undergone industrial qualification to ensure longevity, reliability, and multi-variable sensing. The proposed algorithm selects gateway locations by jointly considering path-loss range and coverage probability, producing the appropriate number and placement of devices to meet service requirements. Critically, the number of link ports is determined by device density and spatial placement rather than the number of sheds. In the environmental-variable instance with 72 endpoints, the optimization keeps the gateway count fixed while reducing the required link ports from 16 to 4 as the effective coverage radius increases, yielding up to 82% reduction relative to a dense candidate-grid baseline. In the physical-variable instance with 41 endpoints, the required ports decrease from 16 to 6 (70% reduction) for the same coverage target, illustrating how modest improvements in coverage range and placement translate into tangible savings in link-port hardware. Simulation analyses confirm robust link performance at distances up to 200 m from the data center, and short-term Wireshark captures corroborate end-to-end delivery on the deployed links; a detailed long-term statistical characterization of PDR, latency, throughput, and energy per delivered sample is left for future work. In sum, complete site coverage is attainable through efficient use of spectrum, transmit power, and device resources, while maintaining secure and reliable communications. These conclusions are valid for the operating conditions, traffic patterns, and environmental characteristics of the evaluated poultry farm; applying the same methodology to other agricultural or industrial scenarios will require re-calibrating the propagation model and re-running the optimization with the corresponding device and regulatory parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.; Validation, M.R.; Formal analysis, G.C.; Investigation, G.C.; Data curation, A.A.; Writing—review & editing, E.G. and A.A.; Visualization, E.G. and A.A.; Supervision, M.R.; Project administration, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pereira, W.F.; da Silva Fonseca, L.; Putti, F.F.; Góes, B.C.; de Paula Naves, L. Environmental monitoring in a poultry farm using an instrument developed with the internet of things concept. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.A.; Mendonça, F. A Critical Review of the Propagation Models Employed in LoRa Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelista, L. Frequency plans, range and scalability for LoRaWAN. Comput. Commun. 2023, 216, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.L.; Bucheli, J.; Sampath, A.; Bedewy, A.M.; Di Mare, M.; Shental, O.; Islam, M.N. A Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Approach to Deploying Base Stations and Repeaters. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2023, 27, 3414–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savithi, C.; Kaewta, C. Multi-Objective Optimization of Gateway Location Selection in LoRaWANs. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2024, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, L.; He, J. Design of agricultural wireless sensor network node optimization method based on farmland monitoring. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Fei, T. An Optimization Coverage Strategy for Wireless Sensor Network Nodes Based on Path Loss and False Alarm Probability. Sensors 2025, 25, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, M.O.; Viola, I.; Miretti, S.; Martignani, E.; Giordano, S.; Baratta, M. A Deep Learning Approach for Accurate Path Loss Prediction in LoRaWAN Livestock Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Patel, K.; Silva, M. Field-validated LoRa coverage for crop monitoring under dense vegetation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.H.; Shukor, S.; Saad, F.; Ehkan, P.; Mustafa, H. Wireless electronic nose using GPRS/GSM system for chicken barn climate and hazardous volatile compounds monitoring and control. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Electronic Design (ICED), Phuket, Thailand, 11–12 August 2016; pp. 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, N.S.; Abas, A.M.F.M.; Azmi, N.A.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Shafie, A.A. Chicken farm monitoring system. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26–27 July 2016; pp. 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Debauche, O.; Mahmoudi, S.; Mahmoudi, S.A.; Manneback, P.; Bindelle, J.; Lebeau, F. Edge computing and artificial intelligence for real-time poultry monitoring. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 175, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittisut, P.; Pornsuwancharoen, N. Design of information environment chicken farm for management which based upon GPRS technology. Procedia Eng. 2012, 32, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio H, R.; Tinoco, I.F.; Osorio S, J.A.; Souza, C.d.F.; Coelho, D.J.d.R.; Sousa, F.C.d. Air quality in a poultry house with natural ventilation during phase chicks. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2016, 20, 660–665. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, M.G.R. Wireless sensor network for smart home services using optimal communications. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Science (INCISCOS), Quito, Ecuador, 23–25 November 2017; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- So-In, C.; Poolsanguan, S.; Rujirakul, K. A hybrid mobile environmental and population density management system for smart poultry farms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 109, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, J.; Dara, R.A.; Fraser, E.D.; Roberts, B.; Sharif, S. Smart poultry management: Smart sensors, big data, and the internet of things. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi, A.; Zero, E.; Sacile, R.; Trinchero, D.; Fossa, M. Smart Sensors and Smart Data for Precision Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, P.; Sugeru, H.; Wibowo, E.P. Wireless Sensor Networks for Precision Agriculture: A Review of NPK Sensor Implementations. Sensors 2024, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inga, E.; Cespedes, S.; Hincapie, R.; Cardenas, C.A. Scalable Route Map for Advanced Metering Infrastructure Based on Optimal Routing of Wireless Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganán, C.; Inga, E.; Hincapié, R. Optimal deployment and routing geographic of UDAP for advanced metering infrastructure based on MST algorithm. Ingeniare. Rev. Chil. De Ingeniería 2017, 25, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, A.; Inga, E.; Hincapié, R. Optimal Scalability of FiWi Networks Based on Multistage Stochastic Programming and Policies. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2017, 9, 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Masache, P.; Dominguez, J. High Availability Network for Critical Communications on Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the IV School on Systems and Networks (SSN 2018), CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Valdivia, Chile, 29–31 October 2018; Volume 2178, pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).