Abstract

This study presents an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional energy-intensive methods for soil improvement by investigating an enzyme-induced active magnesium oxide carbonation (EIMC) technique for the stabilization of gravelly soil. The solidification efficacy and strengthening mechanism of EIMC-treated soil were systematically investigated through a combination of mechanical property tests and microstructural analyses. Results indicate that key mechanical properties—including compressive strength, shear strength, and elastic modulus—were directly proportional to the magnesium oxide (MgO) content. Notably, an 8% MgO content resulted in a 113-fold increase in unconfined compressive strength (UCS) compared to the untreated soil. The strength development stabilized after a five-day curing period. While higher MgO content yielded greater absolute strength, the efficiency of strength gain per unit of MgO peaked at a 4% dosage. Consequently, considering both performance and efficiency, an MgO content of 4% and a curing period of 5 days are recommended as the optimal parameters. The EIMC treatment substantially improved the soil’s mechanical properties, inducing a transition in the failure mode from plastic to brittle, with this brittleness becoming more pronounced at higher MgO concentrations. Furthermore, the treatment enhanced the soil’s water stability. Microstructural analysis revealed that the formation of hydrated magnesium carbonates filled voids, cemented particles, and created a dense structural matrix. This densification of the internal structure underpinned the observed mechanical improvements. These findings validate EIMC as a feasible and effective eco-friendly technique for gravelly soil stabilization.

1. Introduction

Gravelly soil is a widely distributed natural soil–rock mixture characterized by significant heterogeneity, exhibiting mechanical properties of both coarse-grained and fine-grained soils. Its outstanding engineering performance—marked by low compressibility, high strength, high permeability, and cost-effectiveness—has led to extensive application in hydraulic engineering, transportation infrastructure, and building foundations. Hunan Province contains abundant limestone and silty clay deposits. Therefore, considering economic factors, some projects locally utilize soil–rock mixture composed of limestone and silty clay for embankment construction. However, limestone has relatively low strength, is prone to fragmentation and dissolution, and exhibits limited durability in aqueous environments. Hunan Province is located in a subtropical region characterized by high rainfall and developed groundwater systems. In this environment, limestone is geotechnically unstable for engineering applications, which can degrade the mechanical properties of soil, cause instability in earth–rock dams or embankments, and lead to safety incidents.

To address these issues, common improvement methods include physical modification [,] and chemical modification [,,]. Commonly used chemical stabilizers include lime, cement, and fly ash. Yang et al. [] found that fly ash enhances the strength of silty clay and improves its cohesion and internal friction angle. Additionally, some researchers have observed that traditional stabilizers can also improve the soil’s erosion resistance [,] and durability [,]. Nevertheless, these methods, while able to increase strength, are associated with environmental pollution, high cost, poor moisture stability, and high energy consumption. Therefore, the development of an environmentally friendly and sustainable solidification technology for gravelly soil is required.

Reactive magnesia (MgO) is an energy-efficient inorganic binder with low environmental impact and established engineering applicability. Compared with Portland cement, MgO can sequester atmospheric CO2 and, when used as an admixture in cement or concrete, improves mechanical performance and chemical resistance [,]. MgO is also used as an expansive agent that enhances crack self-healing in cement and concrete [,]. Reactive magnesia carbonation soil stabilization was first jointly proposed by the teams led by Songyu Liu and Liska. This technology uses MgO as a binder, thoroughly mixed with soil. Under pressure, carbon dioxide is introduced to promote the hydration and carbonation of MgO, forming hydrated magnesium carbonates. These products bond soil particles and fill pores, thereby stabilizing the soil [,]. This soil stabilization technique significantly and rapidly enhances soil strength [,]. Additionally, MgO carbonation technology has been found to improve soil durability [,]. However, field application has been limited because CO2 injection is complex and difficult to control. CO2 diffusion within soil voids, nonuniform carbonation of the soil matrix, and potential environmental impacts from leakage have been reported, which constrain engineering implementation [].

Subsequently, researchers have explored methods to introduce internal carbon sources to enable the self-carbonation of MgO. In a related development, some researchers have recently combined microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) technology with MgO carbonation technology, proposing a microbially assisted MgO carbonation and solidification technology to improve soil properties [,]. Chen et al. [] applied this technology to stabilize electrolytic manganese slag, achieving greater compressive strength and lower heavy-metal leaching. Zhang et al. [] reported its use to improve the resistance to seawater wetting of coastal sand dunes. The underlying mechanism is that microorganisms promote MgO carbonation by producing urease, which hydrolyzes urea to generate carbonate ions. The underlying mechanism is derived from conventional MICP technology []. In MICP, microorganisms produce urease, which hydrolyzes urea to generate carbonate ions that typically react with a calcium source to form calcium carbonate. In a similar manner, this enzymatic production of carbonate ions can be harnessed to supply the carbonate required for MgO carbonation. Moreover, utilizing microorganisms to provide carbonate ions avoids secondary pollution, making it a more environmentally friendly approach.

However, the microbial method requires the cultivation of microorganisms, a process that is complex and susceptible to environmental factors. These factors, together with the relatively high cost, have limited the large-scale application of this technology in field engineering projects [,]. As an alternative, low-cost plant-derived urease can be used to catalyze urea hydrolysis, which supplies the carbonate ions required for magnesium oxide carbonation and eliminates the need for microbial cultivation. This enzymatic approach is less susceptible to environmental factors, does not require oxygen, and is suitable for deep-layer engineering fill applications [,,]. Existing research indicates that Enzyme-Induced reactive Magnesia Carbonation (EIMC) solidification technology can effectively improve soil properties []. However, research on the application of EIMC for solidifying gravelly soil remains limited [].

Accordingly, enzyme-induced reactive magnesia carbonation (EIMC) was applied to reinforce gravelly soil. Unconfined compressive strength (UCS), triaxial, and water-stability tests were performed to quantify the effects of MgO content and curing period on solidification performance. Comparative analyses with alternative treatments were conducted to benchmark efficacy. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the microstructure and crystalline morphology of the EIMC-treated gravelly soil and to elucidate the strengthening mechanism. A basis for the practical engineering application of EIMC in gravelly soil improvement was established.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

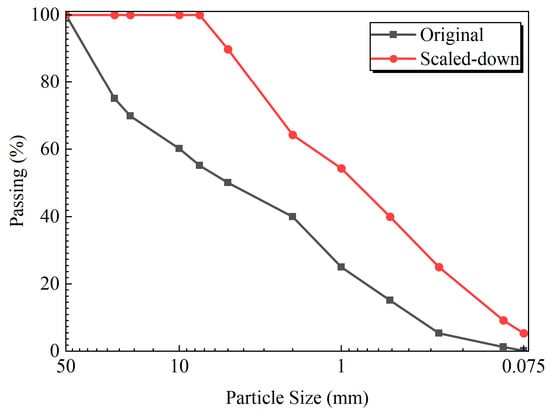

The gravelly soil utilized in this study was obtained from a site in the Hengyang region of Hunan Province, China. This soil was a natural mixture primarily composed of limestone gravel and silty clay. It was characterized by a maximum particle size of 50 mm and a gravel content of 60%. Key physical properties are detailed in Table 1 and Table 2. The particle size distribution curve is presented in Figure 1. Based on this distribution, the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) and the coefficient of curvature (Cc) were calculated as 26.7 and 0.56, respectively, indicating a poorly graded material. The chemical reagents, including light-burned MgO and urea, were procured from Hunan Bkmam Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changde, China), while calcium chloride was supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The activity of the MgO, determined using the hydration method, was 80%, classifying it as high-reactivity MgO. The soybean meal was sourced from Shandong Province.

Table 1.

Basic Physical Indicators of Powdery Clay.

Table 2.

Limestone basic physical index.

Figure 1.

Grain gradation curve of original soil sample and scale soil sample.

2.2. Soybean Urease

The urease enzyme for this study was extracted from commercially available soybean meal. The extraction procedure was performed as follows. First, the soybean meal was sieved through a 0.25 mm mesh to remove coarse particles. Subsequently, the sieved meal was mixed with deionized water in a beaker at a mass ratio of 1:10 (soybean meal to water). The mixture was then agitated using a magnetic stirrer for 30 min to create a homogeneous suspension. This suspension was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 2 h and subsequently centrifuged at 4500× g rpm for 15 min. Following centrifugation, the resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.075 mm sieve to yield the final urease solution.

Urease activity was determined via a conductivity-based method [], which measures the increase in solution conductivity resulting from the enzymatic hydrolysis of urea into ions. The procedure involved mixing 27 mL of a 1.1 mol/L urea solution with 3 mL of the urease solution. The mixture was maintained at a constant 30 °C in a water bath while its conductivity change was monitored for 15 min. The average rate of conductivity change was then calculated and converted to the rate of urea hydrolysis. At a test temperature of 30 °C, the urease activity was determined to be 5.60 mmol/(L·min).

2.3. Test Program

The experimental program, detailed in Table 3, was designed to investigate the urease-assisted MgO stabilization of gravelly soil. It comprised a control series (Groups S1–S4) and a parametric study on MgO dosage (Groups M1–M4). The control series benchmarked the EIMC method against several conditions: untreated soil (S1); soil treated with conventional Enzyme-Induced Calcite Precipitation (EICP) using a 2 mol/L solution (S2); soil with 8% MgO alone (S3); and soil with 8% MgO and 2 mol/L urea (S4). The parametric series (M1–M4) evaluated the effect of varying MgO dosages of 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% by dry soil mass. For all EIMC-treated groups (S4, M1–M4), the initial moisture content was set to 12% and the urea concentration was 2 mol/L. All specimens were cured for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days prior to testing.

Table 3.

Test program.

2.4. Sample Preparation and Testing Methods

Due to the presence of coarse particles, the maximum particle size for triaxial specimens was limited to 1/5 of the specimen diameter in accordance with the provisions of China’s Standard for geotechnical testing method (GB/T 50123-2019) []. With a specimen diameter of 39.1 mm and a height of 80 mm, the maximum particle size in this test was 7.82 mm. Therefore, the maximum particle size of the crushed stone was reduced accordingly. The particle size distributions of the original soil sample and the scaled specimen are shown in Figure 1. The soil–rock threshold was calculated using Equation (1) []:

In the equation: dS/RT is the soil–rock threshold; Lc is the engineering characteristic length of gravelly soil (in triaxial tests, Lc is the specimen diameter).

All specimens were prepared using a static compaction method to a target dry density of 2.01 g/cm3. This controlled density, along with a consistent initial moisture content of 12%, was maintained across all mix ratios to ensure uniformity and comparability. The required moisture was provided exclusively by a solution mixture containing urease and urea. The preparation procedure was as follows. First, the necessary quantities of the gravelly soil (composed of soil and aggregate at a 2:3 mass ratio) and MgO were calculated based on the target dry density and then weighed and dry-mixed until homogeneous. Separately, the urease and urea solutions were measured at a 1:1 volume ratio and combined. This combined solution was then added to the solid mixture and mixed thoroughly to ensure uniform moisture distribution. The moist mixture was subsequently compacted into cylindrical steel molds (39.1 mm in diameter and 80 mm in height). After compaction, the surfaces of the specimens were leveled, and the specimens were demolded. Finally, the prepared specimens were transferred to a constant temperature and humidity curing chamber, where they were cured at 30 °C and 95% relative humidity for their designated curing periods.

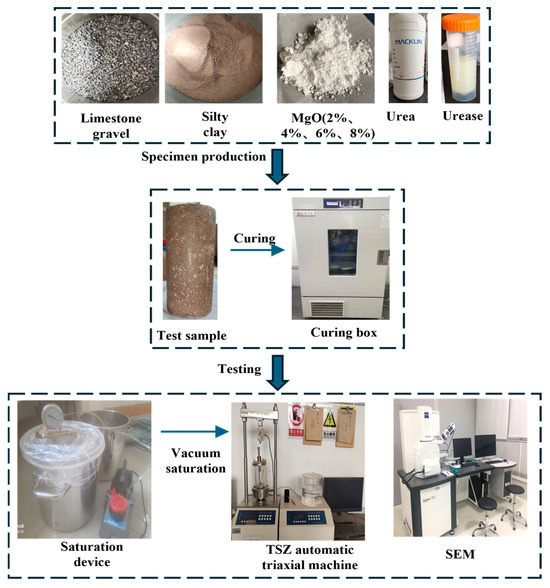

After curing, unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests, triaxial compression tests (prior to the triaxial compression test, the specimens undergo vacuum saturation.), and water stability tests were conducted. Representative specimens were selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis.

The flow chart of the test is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the test.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Unconfined Compressive Behavior

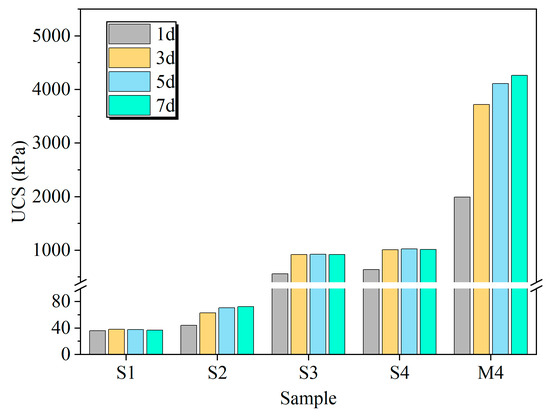

3.1.1. Compressive Strength Analysis

Unconfined compressive strength tests were performed on specimens from all treatment groups, and the results are presented in Figure 3. The untreated soil (Group S1) exhibited a negligible UCS that remained relatively constant throughout the curing period, which can be attributed to its high initial moisture content. In contrast, all treated groups showed varying degrees of strength enhancement compared to the S1 baseline. Among the control groups, the EICP-stabilized specimens (Group S2) demonstrated the most modest strength gain. The most significant improvement was observed in the EIMC-treated specimen with 8% MgO (Group M4), which achieved a UCS approximately 113 times greater than that of the untreated soil.

Figure 3.

Effects of different treatment methods and curing times on unconfined compressive strength of curing specimen.

The UCS of specimens treated with MgO alone (S3) or MgO with urea (S4) surpassed the untreated (S1) and EICP-treated (S2) controls, confirming MgO’s baseline stabilization effect. This initial strength gain stems from the rapid but weak cementation provided by the hydration of MgO into Mg(OH)2. The hydration reaction was largely complete within 3 days, yet the resulting strengths remained considerably lower than those achieved with the full EIMC treatment.

In stark contrast, Group M4 (8% MgO with urease) achieved a final UCS of 4264.3 kPa, significantly outperforming all other groups. This superior performance is attributed to the formation of robust, expansive hydrated magnesium carbonates, which effectively filled voids and cemented soil particles. Furthermore, the EIMC method demonstrated remarkable early-strength development. After only one day, Group M4 reached a UCS of 1992.4 kPa, substantially exceeding the final strengths of the other control groups. This rapid strengthening is likely a consequence of the concurrent hydration and enzyme-catalyzed carbonation of MgO. These findings show that the EIMC technique provides both higher ultimate strength and more rapid stabilization for gravelly soil compared to the other methods investigated.

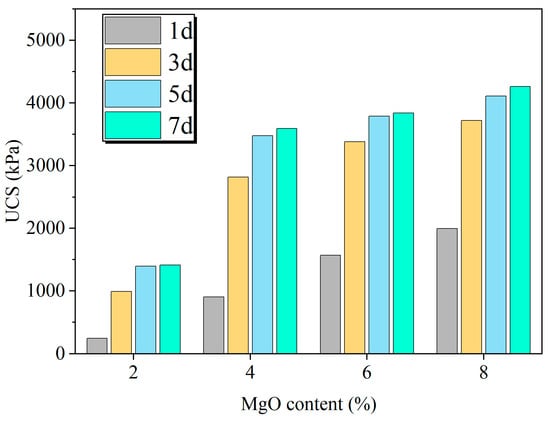

As illustrated in Figure 4, the UCS of the specimens demonstrated a clear positive correlation with the MgO content. This trend is attributed to a higher MgO content providing more reactant for the EIMC process, which leads to a greater yield of both magnesium hydroxide and the crucial hydrated magnesium carbonate binders. The resulting increase in cementitious products leads to a denser soil matrix and, consequently, improved mechanical performance.

Figure 4.

Effect of MgO content and curing times on unconfined compressive strength of curing specimen.

The strength development of EIMC-treated soil is a time-dependent process governed by MgO hydration, urease-catalyzed urea hydrolysis, and the subsequent formation of cementitious products. As shown in Figure 4, for any given MgO content, the UCS increased with curing time before plateauing.

The specimens exhibited significant early-strength gain. After just one day of curing, the UCS values for specimens with 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% MgO reached 245.8, 904.8, 1569.4, and 1992.4 kPa, respectively. It was observed that higher MgO dosages resulted in greater early strength, likely because a larger quantity of reactants facilitates a more rapid and widespread formation of binders. The rate of strength development was highest within the first three days, during which all specimens attained over 70% of their final strength. This period aligns with the peak activity of urease-catalyzed urea hydrolysis. By day 5, the hydrolysis reaction was substantially complete, leading to a significant deceleration in strength gain. Although residual hydrolysis products continued to react slowly with magnesium hydroxide, causing minor strength increases thereafter, the majority of the strength had been achieved.

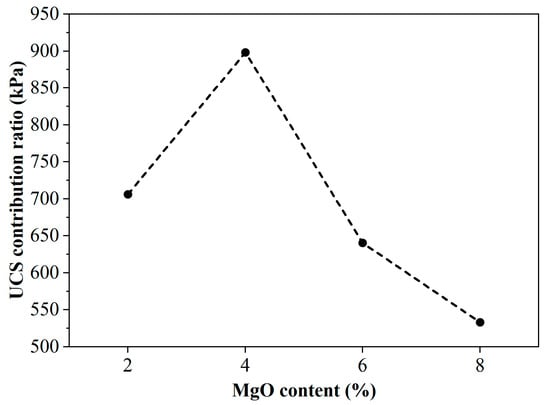

To evaluate the efficiency of the stabilization, a “UCS contribution ratio” was defined as the UCS gain per unit of active MgO content. This metric quantifies the binder’s efficiency, with a higher ratio indicating a more effective use of the material. The relationship between this ratio and the MgO dosage is presented in Figure 5. The UCS contribution ratio was observed to increase with MgO content up to 4%, after which it declined. The peak at 4% signifies that this dosage provides the maximum strength gain per unit of MgO. This finding suggests a point of diminishing returns for dosages above 4%.

Figure 5.

Strength contribution ratio of samples with different magnesia content after 7 days of curing.

3.1.2. Stress–Strain Curve and Fracture Behavior Analysis

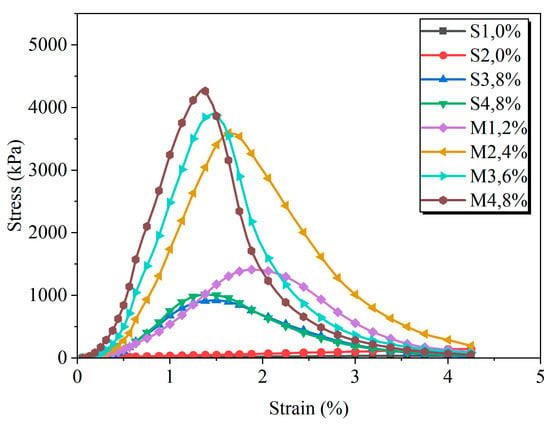

The stress–strain behavior of the gravelly soil under various treatment conditions was evaluated through unconfined compression tests, with the results depicted in Figure 6. The untreated soil (S1) displayed ductile, plastic failure without a distinct stress peak. In contrast, all stabilized groups exhibited brittle failure, characterized by a well-defined peak strength followed by a sharp post-peak stress drop. This transition is attributed to the formation of cementitious binders, which increased the soil’s cohesion.

Figure 6.

Unconfined compressive strength of each group after 7 days of curing.

Within the EIMC-treated series (Groups M1–M4), an increase in MgO content led to a more pronounced brittle response. Specifically, higher MgO dosages resulted in a higher peak strength, a lower failure strain, and reduced ductility. This is because the greater production of hydrated magnesium carbonates created a more rigid soil matrix, while the associated water consumption reduced the soil’s plasticity.

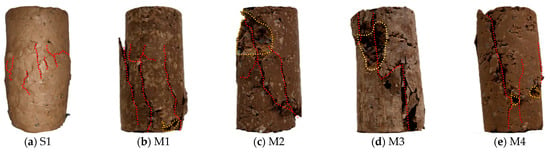

The failure modes of the specimens after UCS testing, shown in Figure 7, varied distinctly with MgO content, reflecting the transition from plastic to brittle behavior. The untreated soil (S1) failed by plastic bulging, indicative of its ductile nature. At a 2% MgO dosage, failure initiated at the lower end of the specimens with upward-propagating cracks. This localized failure suggests a non-uniform distribution of the limited cementitious products, resulting in inconsistent stabilization. When the MgO content was increased to 4%, the specimens predominantly failed through shear, but still exhibited some plastic deformation. This suggests a more uniform distribution of binders and improved particle bonding, leading to greater macroscopic integrity. At higher dosages of 6% and 8% MgO, the failure mode shifted to brittle splitting, characterized by the formation of vertical, through-going cracks. This type of failure is indicative of a well-cemented and rigid internal structure, confirming the enhanced stabilization effect at higher MgO concentrations.

Figure 7.

Failure patterns of samples with different active magnesium oxide content: (a) 0%; (b) 2%; (c) 4%; (d) 6%; (e) 8%.

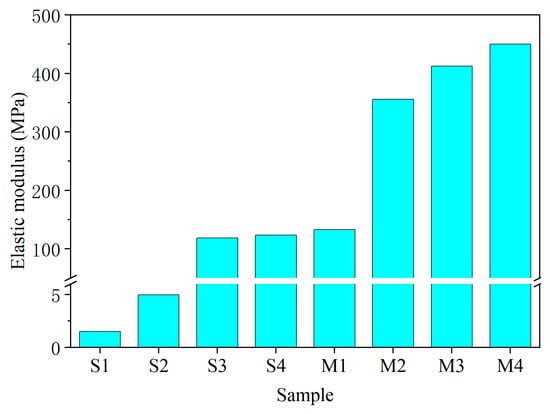

3.1.3. Elastic Modulus

The elastic modulus reflects a material’s resistance to elastic deformation. In this study, it was calculated as the tangent modulus from the initial linear portion of the stress–strain curve. The results for all groups are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Elastic modulus of each group.

A significant increase in the elastic modulus was observed for all stabilized specimens compared to the untreated soil (S1). Notably, the EIMC-treated soils consistently demonstrated the highest elastic moduli, indicating a superior stiffness and resistance to deformation. This finding further highlights the enhanced performance of the EIMC technique over the other stabilization methods investigated. Furthermore, the elastic modulus showed a direct positive correlation with the MgO content, increasing as the dosage was raised.

3.2. Triaxial Compression Test

3.2.1. Stress–Strain Curve Analysis

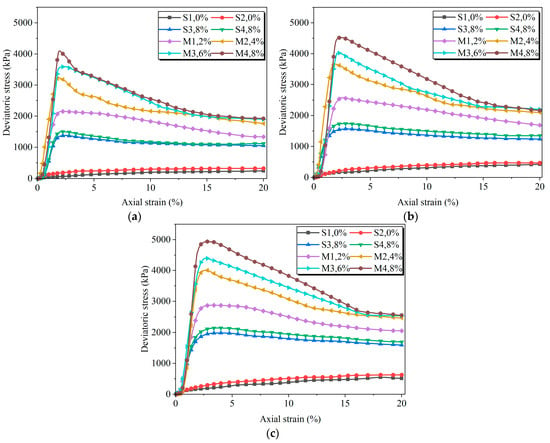

The stress–strain relationships from unconsolidated-undrained triaxial tests are presented in Figure 9, illustrating the influence of confining pressure and stabilization method on shear behavior. A clear distinction in mechanical response was observed. The untreated soil (S1) and the EICP-treated specimens (S2) both exhibited strain-hardening behavior, where the deviatoric stress continuously increased with axial strain without reaching a distinct peak. In contrast, all MgO-based stabilized groups (S3, S4, and M1–M4) displayed strain-softening behavior, characterized by a clear peak deviatoric stress followed by a post-peak decline.

Figure 9.

Stress–strain relationship curves of samples after 7 days of curing under different confining pressures: (a) σ3 = 100 kPa; (b) σ3 = 200 kPa; (c) σ3 = 200 kPa.

All stabilization treatments resulted in an upward shift in the stress–strain curves, signifying enhanced shear strength. However, the EIMC-treated specimens (M1–M4) demonstrated the most significant improvement, with peak deviatoric stresses substantially higher than other treatment methods group. Furthermore, within the EIMC series, an increase in MgO content led to a higher peak deviatoric stress and a more pronounced brittle response. These results confirm that the EIMC technique is highly effective in improving the shear strength of gravelly soil.

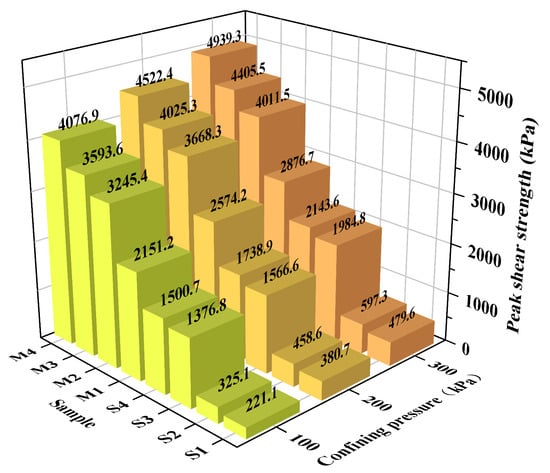

3.2.2. Peak Shear Strength

The peak shear strength of each specimen was determined from the stress–strain curves presented in Figure 10. For materials exhibiting strain-softening, the strength was defined as the peak deviatoric stress. For those displaying strain-hardening behavior, it was taken as the deviatoric stress at 15% axial strain, a common convention for soils lacking a distinct failure peak. All stabilization methods enhanced shear strength relative to the untreated soil (S1), with the EIMC technique proving most effective. For instance, the strength of Group M4 far exceeded that of the EICP (S2) or MgO-only (S3, S4) treatments. Within the EIMC series (M1–M4), shear strength demonstrated a direct positive correlation with MgO content. This is attributed to the greater production of cementitious binders at higher dosages, which results in better integrity and mechanical properties.

Figure 10.

Peak shear strength of each group.

Finally, shear strength for all specimens consistently increased with confining pressure. This is because higher confinement enhances inter-particle friction and lateral restraint, thus requiring greater stress to induce failure.

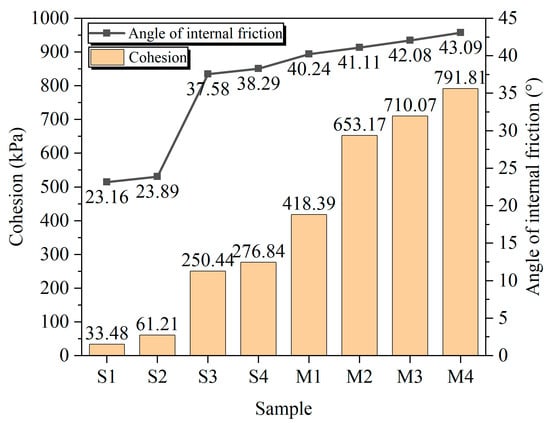

3.2.3. Shear Strength Parameters

Figure 11 The shear strength parameters, cohesion (c) and internal friction angle (φ), for each group are presented in Figure 11. All stabilization treatments enhanced both parameters relative to the untreated soil (S1), with the EIMC-treated group (M4) achieving the highest values due to the formation of a dense, high-strength soil-aggregate matrix.

Figure 11.

Cohesion and internal friction angle of each group.

Within the EIMC series (M1–M4), both c and φ increased directly with MgO content. This trend is consistent with and corroborated by other observed Macroscopic scale behaviors. A higher MgO dosage also led to an increased elastic modulus, indicating enhanced structural rigidity. Simultaneously, the failure mode transitioned from plastic to brittle, producing more convoluted fracture surfaces that reflect a simultaneous increase in both cohesion and frictional resistance. The underlying mechanism for these interconnected phenomena is that a higher MgO dosage yields a greater volume of binding agents. This creates a denser and stronger cementation network between particles, enhancing both the cohesive strength and the mechanical interlocking effect. Consequently, a more robust and compact soil structure is formed, leading to an overall improvement in mechanical properties.

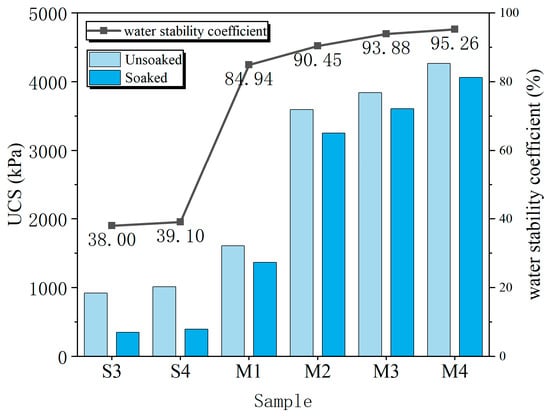

3.3. Water Stability Tests

The water stability of the stabilized soil was quantified using a water stability coefficient, defined as the ratio of the UCS of a specimen after 24-h water immersion to that of an unsoaked counterpart. The test results for all groups are presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Strength changes in samples from each group before and after immersion and water stability coefficient.

A dramatic difference in performance was observed. The untreated soil (S1) and the EICP-treated specimens (S2) completely disintegrated upon immersion, resulting in a water stability coefficient of zero. This is attributed to the inherent high porosity of the untreated soil and the inability of the fine calcium carbonate particles from EICP to fill large voids, leading to poor resistance to water ingress. In contrast, all MgO-based treatments maintained their structural integrity. The MgO-only groups (S3 and S4) exhibited modest coefficients of 38.0% and 39.1%, respectively, as the weak cementation from magnesium hydroxide offered limited resistance to water erosion.

The EIMC-treated specimens demonstrated exceptional water stability, with coefficients ranging from 84.9% (M1) to 95.3% (M4). This superior performance stems from the synergistic action of the reaction products. Both Mg(OH)2 and, crucially, various hydrated magnesium carbonates filled voids and bonded particles. The expansive nature of the hydrated magnesium carbonates was particularly effective in plugging larger pores, which densified the soil matrix, reduced porosity, and inhibited the dissolution of soluble components. Consequently, within the EIMC series, the water stability coefficient increased with MgO dosage, confirming that the EIMC technique significantly enhances the water stability of gravelly soil.

The comprehensive mechanical test results demonstrate the engineering feasibility of the EIMC technique. The unconfined compressive strength, cohesion, and internal friction angle of the EIMC-stabilized gravelly soil, particularly at higher MgO dosages, met the minimum requirements (e.g., UCS ≥ 300 kPa, c ≥ 20 kPa, φ ≥ 35°) stipulated in the Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades (JTG D30-2015) [].

While increasing MgO content generally enhanced all properties, it also induced greater brittleness and exhibited diminishing returns. The material efficiency, quantified by the strength contribution ratio, peaked at a 4% MgO dosage. At this level, the soil achieved excellent water stability while mitigating the risk of excessive brittleness. Similarly, strength development analysis showed that extending the curing period beyond 5 days yielded negligible further improvement, making it economically inefficient. For the 4% MgO specimen, the UCS increased by factors of 23, 75, 93, and 96 at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days, respectively. The negligible strength gain between day 5 and day 7 (from 93-fold to 96-fold) indicates that extending the curing period beyond 5 days is inefficient. Therefore, considering the crucial balance between achieving high performance, ensuring material efficiency, mitigating brittleness, and optimizing construction time and cost, an MgO content of 4% and a curing period of 5 days are identified as the optimal parameters for the EIMC stabilization of gravelly soil in this study.

3.4. Microscopic Analysis and Analysis of the Mechanism of Action

3.4.1. SEM

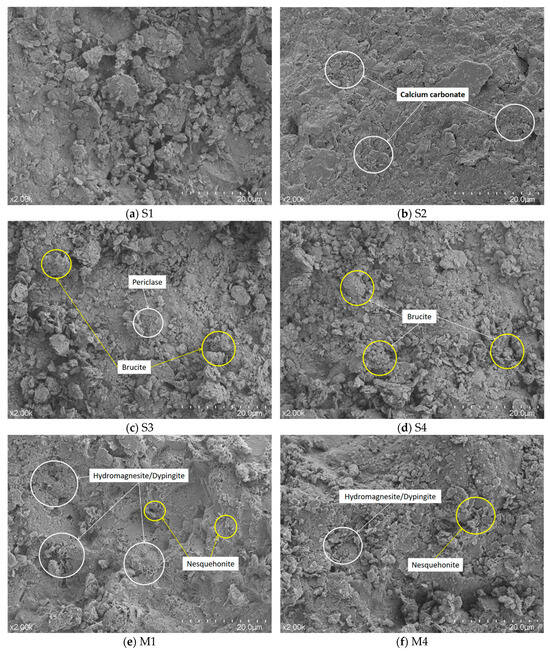

The microstructures of the stabilized soils were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with representative images presented in Figure 13. The untreated soil (Figure 13a) displayed a porous and fragmented structure with large inter-particle voids and a loose arrangement, indicating poor natural cohesion. The EICP-treated specimen (Figure 13b) showed some precipitated calcium carbonate crystals merely coating the particle surfaces, failing to effectively bridge the voids or improve the loose structure. Similarly, the MgO-only treatment (Figure 13c) resulted in clusters of magnesium hydroxide filling some pores, but the overall structure remained loose, with the products acting as a coating rather than a robust binder. The microstructure of Group S4 (Figure 13d) was largely unchanged compared to S3, confirming that significant carbonation did not occur without the urease enzyme.

Figure 13.

SEM micrographs of samples treated with various methods and containing different active magnesium oxide contents, after 7 days of curing.

In stark contrast, the EIMC-treated specimens (Figure 13e,f) exhibited a significantly denser and more integrated microstructure. Drawing on established morphological identifications [,], the SEM images revealed the presence of various hydrated magnesium carbonates: abundant flake-like or flower-like hydromagnesite and dypingite, alongside prismatic nesquehonite. These carbonate products did not just coat the particles; they actively filled pores, cemented adjacent soil and gravel particles, and formed an extensive, interconnected network structure throughout the soil matrix. This network is the fundamental reason for the observed improvements in mechanical properties and microstructural compactness.

A comparison between the EIMC specimens shows that the sample with 8% MgO (Figure 13e) possessed a denser structure with fewer microscopic pores than the sample with 2% MgO (Figure 13f). This is a direct consequence of the higher MgO dosage generating a greater volume of carbonate products, leading to more effective pore-filling and a more robust cementation network.

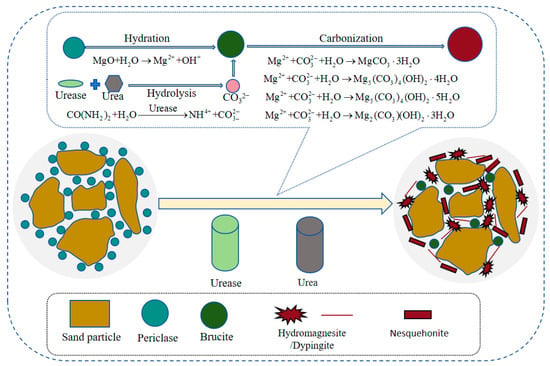

3.4.2. Mechanism of Action

Soil strength is related not only to carbonate content but also to the distribution of carbonates within the soil and to the cementation mode []. Cementation can be classified into three modes: coating, bonding, and bridging. While all three modes reduce porosity, strength enhancement primarily relies on carbonate precipitates that exert bonding and bridging effects [].

The EIMC process involves two key, concurrent reaction pathways. First, the hydration of reactive MgO produces brucite. While brucite contributes to pore-filling, it primarily forms loose agglomerates that act as a simple coating on soil particles, offering limited cementitious value and strength gain, as confirmed by both our microstructural observations and previous studies []. Second, and more crucially, the urease-catalyzed hydrolysis of urea provides a continuous supply of carbonate ions. These ions react with the newly formed brucite to precipitate various HMCs, such as prismatic nesquehonite and lamellar or fibrous hydromagnesite and dypingite. These HMCs possess two critical advantages over brucite: greater expansivity and superior cementation capacity.

Consequently, the HMCs do not merely coat the particles. Instead, they actively bond particles at their contact points and bridge the gaps between them, forming a stable, interconnected structural network throughout the soil matrix. This transition from a simple “coating” mode (dominant in MgO-only systems) to a “bonding and bridging” mode (dominant in the EIMC system) is the fundamental reason for the significant improvements in cohesion, shear strength, and overall mechanical performance observed in this study []. Based on the above analysis, a schematic diagram of the EIMC stabilization mechanism for gravelly soil is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The schematic diagram of the stabilization mechanism for gravel soil through enzyme-induced reactive magnesium oxide carbonation.

4. Discussion

This study successfully demonstrates that the EIMC technique is a highly effective method for stabilizing gravelly soil. The superior mechanical and durability performance of EIMC-treated soil, as compared to other methods, corroborates the findings of Yang et al. [] regarding the potential of active MgO bio-carbonation. The central contribution of this work, however, lies in elucidating the microstructural mechanism responsible for this enhancement. Our SEM analysis provides direct evidence that distinguishes the EIMC process: it facilitates the formation of an extensive, interconnected network of hydrated magnesium carbonates (HMCs). This “bonding and bridging” mechanism is fundamentally different from the less effective “coating” mechanism observed in MgO-only or EICP treatments, thus explaining the dramatic improvements in soil integrity and strength. The research offers significant practical implications, establishing a theoretical basis for EIMC as a green soil stabilization alternative. It provides practical guidance for engineering applications of coarse-grained soils, particularly in the construction of rock-fill dams and road embankments where durability is critical.

While this study establishes the efficacy of EIMC under controlled laboratory conditions, certain limitations guide future research. The current investigation did not account for the complex conditions encountered in real-world engineering projects. Therefore, future studies should evaluate the performance of EIMC-treated soil under more challenging scenarios, including dynamic loading (e.g., traffic or hydrodynamic forces) and varying environmental factors (e.g., temperature fluctuations, complex water chemistry, and the presence of organic matter).

To advance from qualitative observation to quantitative prediction, future work could focus on multi-scale modeling, such as coupling the Discrete Element Method (DEM) with chemo-hydraulic models [,]. Most importantly, transitioning this promising technology from laboratory-scale to pilot- and full-scale field applications is a critical next step to validate its practical feasibility, long-term performance, and economic viability.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive investigation into the stabilization of gravelly soil using an enzyme-catalyzed active magnesium oxide carbonation (EIMC) technique. The conclusions below are based on an integrated analysis of the soil’s mechanical properties (UCS, shear strength, and elastic modulus), water stability, and microstructural evolution, with the aim of elucidating the underlying strengthening mechanism.

- The EIMC technique demonstrated unequivocally superior performance in enhancing the mechanical properties and durability of gravelly soil. The unconfined compressive strength, shear strength parameters (c and φ), elastic modulus, and water stability of EIMC-treated specimens were all significantly higher than those achieved through conventional EICP, MgO-only, or non-catalyzed urea–MgO treatments.

- While higher MgO content yielded greater absolute strength, it also induced increased brittleness and exhibited diminishing returns in material efficiency. The strength contribution ratio peaked at a 4% MgO dosage, a point at which excellent water stability was already achieved and the risk of excessive brittleness was mitigated. In parallel, strength development analysis revealed that the UCS gain became negligible after a 5-day curing period, making further curing economically inefficient. Therefore, a 4% MgO content and a 5-day curing time are recommended as the optimal conditions for this application.

- The EIMC treatment fundamentally altered the soil’s failure mechanism, inducing a transition from the ductile, plastic behavior of untreated soil to a distinct brittle failure mode. This brittleness became more pronounced at higher MgO contents, corresponding directly to the observed increases in peak strength and stiffness.

- Microstructural analysis revealed the fundamental reason for EIMC’s superior performance. Unlike other methods that result in a simple particle coating, EIMC facilitates the growth of various hydrated magnesium carbonates (HMCs) that actively bond particles and bridge voids. This creates an extensive, interconnected structural network throughout the soil matrix. The transition from a “coating” cementation mode to a “bonding and bridging” mode is the primary mechanism responsible for the dramatic improvements in the soil’s density, integrity, and overall mechanical properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and Y.W.; Methodology, C.P. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; data curation, B.D.; writing—original draft, C.P. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, C.P. and Y.W.; supervision, B.D. and D.W.; funding acquisition, C.P. and B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52079098), the Youth Fund Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51708273), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52308356), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2024JJ5334) and Open Fund Sponsored Project of the Key Laboratory of Earth-Rock Dam Damage Mechanism and Prevention and Control Technology, Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China (No. YK319008).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data provided in the study is included in the article’s figures and tables; for further enquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qiu, Z.L.; Wu, J.D.; Wang, P.; Liang, N.H.; Zhao, K. Experimental Study on the Influence of Soil-Rock Ratio on the Dynamic Compaction Reinforcement Effect of High Fill Gravel Soil Subgrade. Chin. J. Underground Space Eng. 2025, 21, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, S.F.; Niu, L.K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wang, C.W. Journal of Highway and Transportation Research and Development. Experimental Study on Abutment Back Gravel Soil Reinforced with Rapid Hydraulic Impact Compaction. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2024, 41, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Zhang, K.; Dong, F.; Luo, Y.F.; Liu, S. Automated gradation design of natural waste gravel soil stabilized by composite soil stabilizer based on a novel DNNSS-APDM-PFC model. Waste Manag. 2025, 194, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Li, C.; Wang, W.W.; Wang, X.C.; Wei, A.Z.; Sun, L.R.; Wang, C.H. DEM-based Study on Gradation Design Theories and Influence of Strength and Shrinkage Characteristics of Cement Stabilized Aggregate Materials. China J. Highw. Transp. 2025, 38, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Sa, R.; He, Y.Q.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, N.N.; Feng, Y.C.; Ma, S.X. Stabilization of High-Volume Circulating Fluidized Bed Fly Ash Composite Gravels via Gypsum-Enhanced Pressurized Flue Gas Heat Curing. Materials 2025, 18, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.R.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, R.; Song, Z.; Hua, S.D.; Ma, Y. Strength performance of mucky silty clay modified using early-age fly ash-based curing agent. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.R.; Chen, X.S.; Wen, T.D.; Wang, P.H.; Li, W.S. Experimental investigations of hydraulic and mechanical properties of granite residual soil improved with cement addition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 126016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.W.; Hu, Q.Z.; Liu, Y.M.; Tao, G.L. Research on the Improvement of Granite Residual Soil Caused by Fly Ash and Its Slope Stability under Rainfall Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Song, L.; Yue, F.T. Study on Mechanical Properties of Cement-Improved Frozen Soil under Uniaxial Compression Based on Discrete Element Method. Processes 2022, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Pang, W.C.; Li, Z.Q.; Wei, H.B.; Han, L.L. Experimental Study on Consolidation-Creep Behavior of Subgrade Modified Soil in Seasonally Frozen Areas. Materials 2021, 14, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, M.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Performance of magnesia cements in porous blocks in acid and magnesium environments. Adv. Cem. Res. 2012, 24, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Chen, R.F. From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2025, 64, 20250094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Dai, Y.Q.; Gao, K.K.; Wang, W.T.; Zhao, T.J. Effect of Curing Condition on Self-healing of Strain-Hardening Cement-Based Composite Crack Incorporating MgO Expansive Agent. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 47, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Q.; Yang, J.B.; Zhang, P. Hydration and hardening properties of reactive magnesia and Portland cement composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Li, C. Influence of MgO-activity on stabilization efficiency of carbonated mixing method. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, G.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Cao, Q.Q. Research on micro-mechanism of carbonated reactive MgO-stabilized silt. Chin. Civ. Eng. J. 2017, 50, 105–113+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.W.; Zhang, W.Y. Research on the Thermal Conductivity and Microstructure of Calcium Lignosulfonate-Magnesium Oxide Solidified Loess. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, D.N.; Tung, H.; En-Hua, Y.; Jian, C.; Cise, U. New frontiers in sustainable cements: Improving the performance of carbonated reactive MgO concrete via microbial carbonation process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 356, 129243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Zheng, X.; Cai, G.H.; Cai, Q.Q. Study of resistance to sulfate attack of carbonated reactive MgO-stabilized soils. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, S.Y.; Cai, G.H.; Cao, J.J. Experimental study on drying-wetting properties of carbonated reactive MgO-stabilized soils. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 38, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.L.; Lu, K.W.; Liu, S.Y.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Property changes of reactive magnesia-stabilized soil subjected to forced carbonation. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 53, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ruan, S.Q.; Wu, S.F.; Chu, J.; Unluer, C.; Liu, H.L.; Cheng, L. Biocarbonation of reactive magnesia for soil improvement. Acta Geotech. 2020, 16, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.C.; Wu, H.X.; Ding, Y.M.; Fan, J.H. Bio-carbonization of Reactive Magnesia for Sandy Soil Solidification. Geomicrobiol. J. 2023, 40, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, X.W.; Long, K.Q.; Shen, C.N.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.L. Using the Biocarbonization of Reactive Magnesia to Cure Electrolytic Manganese Residue. Geomicrobiol. J. 2021, 38, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Li, Y.H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Yang, Q.G.; Shen, Z.J. An experimental study of mitigating coastal dune erosion by using bio-carbonization of reactive magnesia cement. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2024, 42, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Gao, Y.F.; Gu, Z.X.; Chu, J.; Wang, L.Y. Characterization of crude bacterial urease for CaCO3 precipitation and cementation of silty sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, W.M.; Liu, Z.R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.G. Advances in soil cementation by biologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.L.; Tang, C.S.; Pan, X.H.; Wang, R.; Li, J.W.; Dong, Z.H.; Shi, B. Construction and demolition waste stabilization through a bio-carbonation of reactive magnesia cement for underwater engineering. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 335, 127458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Q.; Ji, J.F.; Qu, S.Y.; Huang, Y.Z.; He, J. Soybean urease intensified magnesia carbonation for soil solidification: Strength and durability under drying-wetting and soaking conditions. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 53, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Y.; Yang, R.D.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Xiang, R.; Gao, F.; Zhang, W.Q.; Ding, Y.; Shi, H.Q.; et al. Mitigation performance and mechanism of the EICP for the erosion resistance of purple soil to concentrated flow in the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Soil Till. Res. 2025, 254, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccurullo, A.; Gallipoli, D.; Bruno, A.W.; Augarde, C.; Hughes, P.; La Borderie, C. Earth stabilisation via carbonate precipitation by plant-derived urease for building applications. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2020, 30, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Y.; Ren, G.Z.; Ju, P.; Fan, H.H. Enzyme-induced reactive magnesium oxide carbonation for fluidized solidified soil. Mater. Rep. 2025, in press.

- He, J.; Qu, S.Y.; Hang, L.; Huang, A.G. Experimental study on enzyme enhanced magnesia carbonation process for soil stabilization. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2024, 46, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.F.; He, J.; Tang, X.Y.; Chu, J. Calcium carbonate precipitation catalyzed by soybean urease as an improvement method for fine-grained soil. Soils Found. 2019, 59, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Methods. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Jing, L.; Zeng, Y.W.; Cheng, T.; Li, J.J. Seepage characteristics of soil-rock mixture based on lattice Boltzmann method. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 44, 669–677. [Google Scholar]

- JTG D30-2015; Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Wu, D.; Wang, Y.Q.; Wu, H.H.; Ma, L.B.; Luo, B.J.; Zhang, Q. Research on Preparation and Morphology Evolution of Magnesium Carbonate Tri-hydrate. J. Synth. Cryst. 2014, 43, 606–613. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Fang, X.W.; Zhang, W.; Shen, C.N.; Lei, Y.L. Experimental study on solidified loess by microbes and reactive magnesium oxide. Rock Soil Mech. 2020, 41, 3300–3306+3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Suleiman, M.T.; Brown, D.G. Investigation of pore-scale CaCO3 distributions and their effects on stiffness and permeability of sands treated by microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). Soils Found. 2020, 60, 944–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Zhang, X.B.; Liu, A.L.; Ma, X.W.; Zhang, H. Progress in Soil Solidification by Enzyme-induced Carbonate Precipitation. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2025, 25, 10103–10115. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X.F.; Wu, S.W.; Qin, J.; Li, X.S.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Mao, J.X.; Nie, W. Multiscale mechanical characterizations of ultrafine tailings mixed with incineration slag. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1123529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.R.; Yan, G.X.; Hofmann, H.; Scheuermann, A. A Novel Permeability–Tortuosity–Porosity Model for Evolving Pore Space and Mineral-Induced Clogging in Porous Medium. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).