Abstract

Background: After unilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA), patients place more weight on the nonsurgical limb than the surgical limb. The objective of this study was to determine the possibility of providing live biofeedback during early recovery of patients undergoing unilateral TKA and to determine the necessary sample size for future trials. Methods: Twenty patients with unilateral TKA were randomized into two groups: a feedback group and a control group. Inclusion criteria included no contralateral knee pain and aid-free walking before surgery. There were 8 patients in the feedback group and 10 in the control group. Compliance with the recommended training was 91%. The feedback group trained with an insole device for 15 min a day for 4 weeks, along with normal physiotherapy. The control group received normal physiotherapy only. Gait parameters were recorded on level ground at two and six weeks. The primary outcome was the percent loading rate. The secondary outcomes included gait speed, cadence, percent peak force, and pain. Results: Patients within the feedback group showed a small, non-significant trend toward a higher precent load rate at 6 weeks compared to the control group in level walking (p = 0.92). Conclusions: Our findings indicate that live biofeedback on a gait parameter, like percent load rate, can be provided by the mentioned system and may support immediate changes in gait parameters. The compliance of 91% with training and no reported adverse events indicates that the system was easy to use. Following TKA, there may be a potential exploratory use of mobile, real-time biofeedback to help address gait abnormalities and accelerate rehabilitation. This clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03673293) on 14 September 2018. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Utah (IRB_00110935) on 10 September 2018.

1. Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) improves mobility and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and decreases knee pain [1,2]. Many efforts have been made to optimize outcomes after TKA, including improving implant design [3] and aftercare programs [4]. A relatively new approach with strong potential is the use of biofeedback on gait parameters in the early recovery phase [5]. It has been reported that biofeedback decreases pain and improves functional ability, but how to provide biofeedback remains unclear [6,7]. Yet, the evidence to date is heterogeneous and often based on lab-based systems, underscoring the gap regarding practical, home-based biofeedback solutions. Wearables are used in orthopedics to track physical activity and physical function, but not in a biofeedback mode [5]. A recent study using wearables for biofeedback has shown that these insole devices are, in fact, sensitive enough to detect gait pattern improvements in just the first 6 weeks after a TKA [8]. In this study, a six-week timeframe was chosen because it represents the routine early follow-up at our center and reflects the clinically most vulnerable period after TKA, during which gait asymmetries are most pronounced and potentially responsive to early intervention. The percent load rate was selected as the primary gait parameter since it indicates the relative weight-bearing between the surgical and non-surgical limb, a relevant clinical outcome for early gait restoration after TKA. It is important that the feedback device is easy to use and that patients can use it at home in order to increase the time and frequency of biofeedback [5]. In the future, this may decrease the time spent in physical therapy and increase training time by making the feedback system widely available. Further, we know that treadmill walking is difficult to translate into clinically relevant interventions given the artificial in-lab situation [9,10]. Gait laboratory analyses using treadmills combined with force plate data, or any other technical setup that needs assistance, are not suitable for clinical or home-based use.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the feasibility and impact of real-time biofeedback provided by a wearable insole device, Loadsol. The secondary exploratory aim was to determine the necessary sample size to adequately power a randomized control trial using this device in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

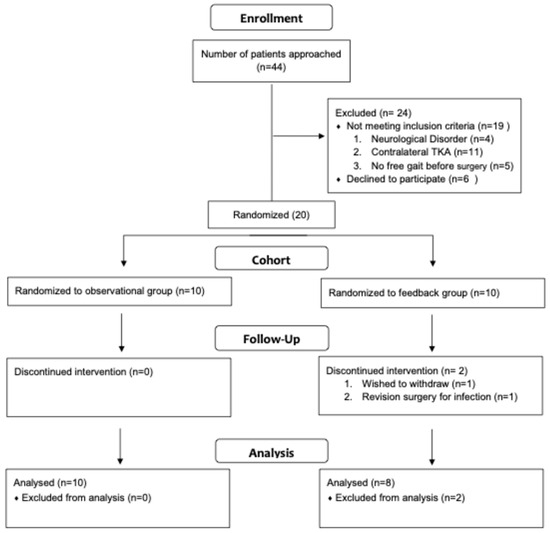

A prospective randomized controlled feasibility trial was conducted to evaluate the impact of biofeedback on the early outcome of TKA. This clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03673293) on 14 September 2018. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Utah (IRB_00110935) on 10 September 2018. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. At a single academic medical center, all patients who underwent unilateral primary TKA between August 2018 and November 2018 were considered for this study (n = 44, Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were unilateral knee arthritis with unilateral TKA planned or performed, absence of significant contralateral extremity pain, and aid-free preoperative gait. Patients with the following conditions were excluded from this study: prior contralateral TKA or any THA (n = 11), neurological disorder (n = 4), and no free gait before surgery (n = 5). The index procedure was a unilateral, primary TKA performed via a medial parapatellar approach. Immediately from the surgery onwards, full weight-bearing was allowed without any other mobility restriction. Participants were randomized by 20 previously prepared and sealed envelopes into feedback and control groups. The allocation sequence was generated using an online random number generator (https://www.random.org/, accessed on 1 May 2018). Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes containing the group assignments were prepared by study coordinators who were not involved in participant enrollment. During enrollment, the principal investigator opened the next envelope in order, after obtaining informed consent and completing baseline assessment. This procedure ensured adequate allocation concealment. Outcome assessors were blinded to group assignment during gait analysis and the collection of patient-reported outcome measures. Conventional therapy was performed at a frequency of twice per week, with one-hour in-person sessions. The focus in the first three weeks is on improvement of the range of motion and stability training. During weeks 3 to 6, the focus was on strengthening and gait training. Both groups attended the same protocol with similar intensities, except that the feedback group had 15 min of biofeedback in addition.

Figure 1.

Attrition flow.

A training and familiarization session with the feedback device was conducted prior to providing it to participants. This 30 min, one-on-one session included instructions on using the device, achieving a “good step,” distributing load evenly, and strengthening the leg. Technical support was provided both immediately during the session and remotely by phone during office hours. Participants in the feedback group were trained in the proper use of Loadsol and performed daily 15 min sessions of continuous walking. These sessions could be completed indoors or outdoors at each patient’s preferred and comfortable walking speed. The control group received conventional physiotherapy only. During gait analysis and feedback sessions, participants were allowed to use a walking aid of their choice.

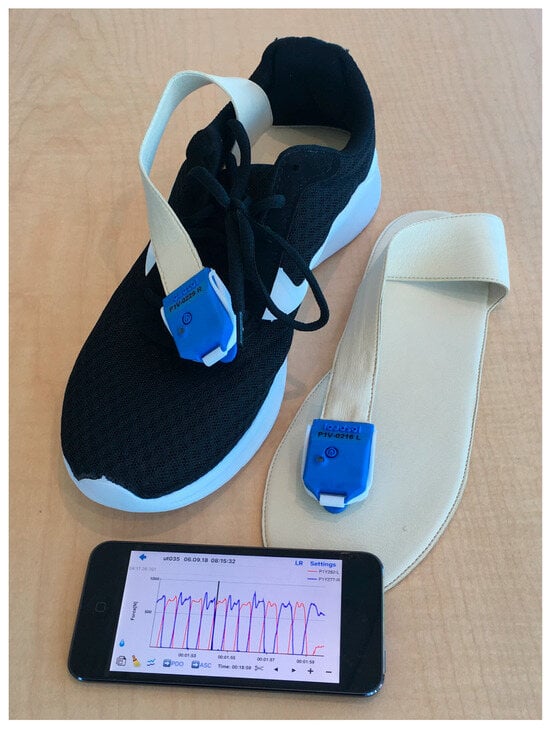

Loadsol is a wearable insole force sensor that covers the entire plantar surface of the foot and records the force during walking up to 200 Hz. (Figure 2). Several studies using Loadsol [8,11,12,13] wearables have shown that they are excellent for measuring ground reaction forces in the early recovery phase after surgery.

Figure 2.

The Loadsol® insole sensor by Novel is displayed.

The gait analysis was performed at two and six weeks post-surgery. Participants walked a fixed distance of 40 m by starting from a chair, level walking, turning, and returning to the chair. This 40 m walkway test is a standardized assessment used at our institution; participants began each trial from a seated position with the Loadsol placed in their shoes to reduce variability across assessments. Neither group received feedback during the gait analysis. The gait analysis was performed at the rehabilitation center attached to the clinic where participants were treated.

The Loadsol was placed in training shoes, prepared for each individual by fitting the shoe size, and communicated via Bluetooth with an iPod (Apple, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All patients walked approximately five minutes to acclimate to the walkway. The plantar force (average peak force in newtons) and the loading rate (newtons per second) were recorded. The loading rate was measured on both feet, steps were counted, and the gait speed and cadence were determined. The percent loading rate is calculated as a percentage of the loading rate (N/s) of the operated limb compared to the non-operated side. The same setup was used during gait analysis and biofeedback intervention, with the only difference being that during gait analysis, no biofeedback was provided to either group.

2.2. Biofeedback on Percent Loading Rate

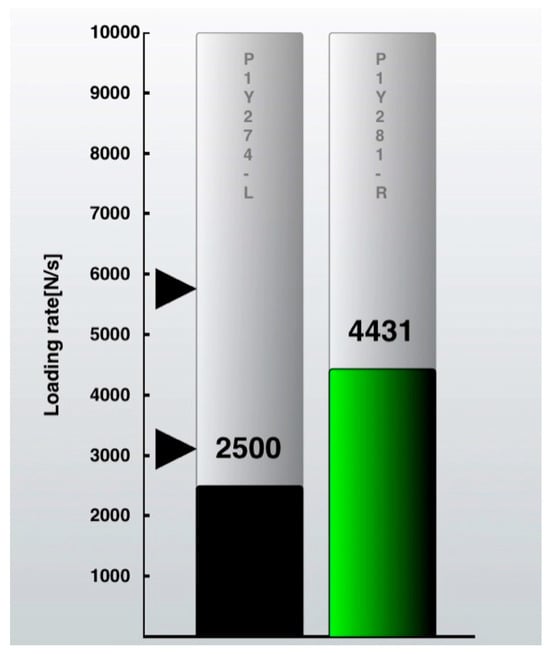

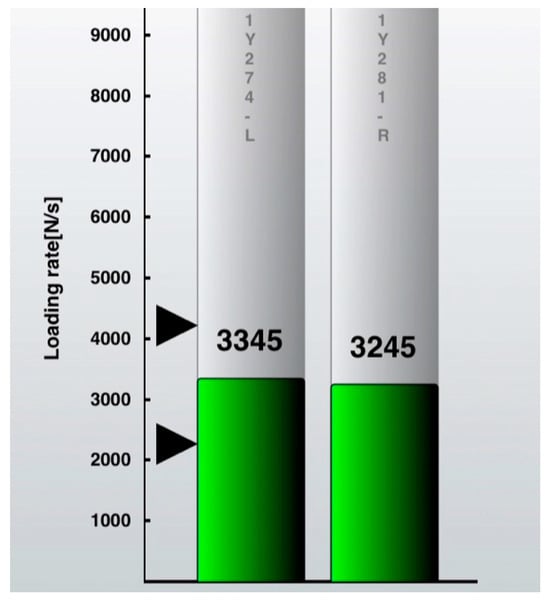

The percent loading rate was used to trigger the biofeedback. The contralateral loading rate for every single step was set at 100%. The goal was to make the following step on the operated side as close as possible to this. Each step was displayed in real time as a bar rising on the iPod screen (Figure 3). If the target zone of ±20% is reached, the black bar will turn green and indicate a “good step” (Figure 4). An acoustical sound will emphasize this. If the operated side is overloaded, the bar will turn red. The visual biofeedback was continuously displayed on the iPod screen, and the acoustical positive biofeedback only appeared if a “good step” was performed. Patients were instructed on how to use the insole and iPod software version iOS 11, and they also received a short manual. Compliance was measured directly from the insole logs by the percentage of actual training spent in minutes from the total amount.

Figure 3.

iPod screenshot with loading rate of the non-operated leg on the right as a green bar. Black arrows indicate the target zone for the operated leg (±20%). Loading rate (N/s = Newton per second) of the operated leg is shown on the left as a black bar.

Figure 4.

iPod screenshot “good step”. The operated leg (left bar) is within the target zone (indicated by black arrowheads) of ±20% of the loading rate (N/s = Newton per second) of the non-operated leg and, therefore, turns into green = positive visual feedback. An acoustical signal will indicate each “good step” at the same time.

2.3. Gait Parameters

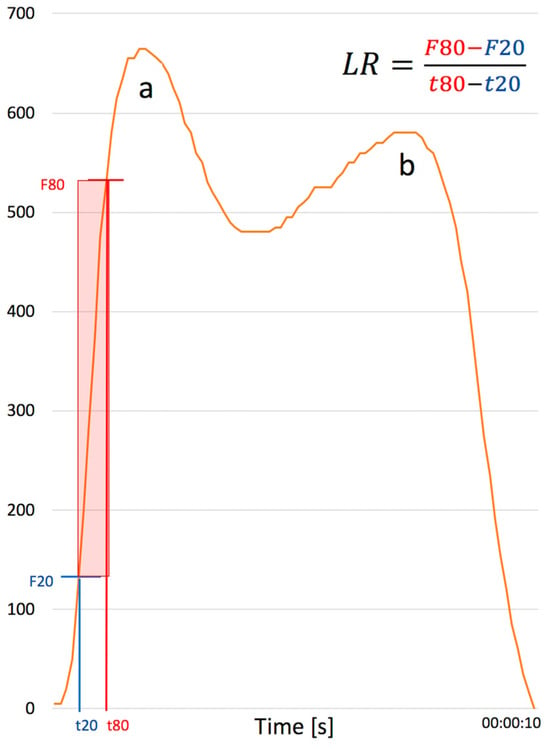

The percent loading rate was the primary outcome parameter in this gait analysis and was used to trigger the biofeedback (Figure 5). The loading rate is the slope of the force curve when the foot is landing on the ground. The heel impact peak is used to calculate the loading rate with the Loadsol® software by Novel. The formula to calculate loading rate (LR) is as follows: , where F20 represents the force in Newtons [N], and t20 represents the time in seconds [s] when the force has reached 20% of the heel impact peak. Accordingly, F80 is the force and t80 is the time at the moment when the force has reached 80% of the heel impact. During the feedback, each single loading rate is compared to the contralateral side. For the gait analysis, the average loading rate over 40 m is calculated.

Figure 5.

Demonstrates one full step from initial heel strike (a) to toe off (b). The loading rate (N/s = Newton per second) is shown as the average force line of a step of a TKA patient with time on the x axis and force in Newton on the y axis. The loading rate is calculated as . The red box indicates the area on the heel strike curve that is used to calculate the loading rate. Abbreviations: F20 = force at 20% of heel impact peak; F80 = force at 80% of heel impact peak; t20 = time at 20% of heel impact peak; t80 = time at 80% of heel impact peak.

Further, we evaluated gait speed, cadence, and percent peak force (the percentage of the peak force of the operated limb compared to the total body weight in Newtons). Gait speed was calculated using the time needed for walking 40 m. Cadence is the number of steps per minute. To minimize variability in gait measurements, all participants were provided with the same type of sneaker (Athletic Works Bungee Slip-On Sneakers, Walmart, Bentonville, AR, USA) in the appropriate size (6–11). The same model was used for all participants at both the two- and six-week assessments. Patient-reported outcomes included the Physical Function Computerized Adaptive Test (PF-CAT), PROMIS Physical Health, PROMIS Mental Health, and PROMIS Global Pain (Chicago, IL, USA) (all PROMIS instruments reported as T-scores with a population mean of 50 and SD of 10), and KOOS Jr. Pain was assessed using a numeric rating scale (0–10) and was recorded twice at each assessment: (1) pain during the standardized 40 m gait test, and (2) pain at rest. Higher scores indicate greater pain. For interpretation, higher PF-CAT, PROMIS Physical Health, PROMIS Mental Health, and KOOS Jr. scores indicate better function/health, while higher PROMIS Global Pain scores indicate more pain.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Given the feasibility nature of this study, the analyses were primarily descriptive. Effect size estimates were reported where appropriate, and p-values were interpreted with caution as exploratory rather than confirmatory. Descriptive statistics, including t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests, were used to compare demographics between patients in the feedback group and patients in the control group. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported for the gait measures and PROM scores. Pairwise differences (6-week measurement minus baseline measurement) were calculated, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the differences between the feedback group and the control group. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. All analyses should therefore be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

A power calculation for a future study for detecting a difference in the change in load rate measurements from the baseline to 6 weeks between group 1 (Loadsol) and group 2 (Routine Care) was performed. The sample size calculation was a post hoc estimate based on the observed between-group difference in this small pilot sample and should be interpreted with caution, given the typical limitations associated with post hoc power analyses. Though medians and Wilcoxon rank sum tests are used in the comparisons in this trial because of the small sample size, a larger study would use means, standard deviations, and t-tests. The sample means (17.21 and 14.75 for Loadsol and Routine Care) and standard deviations (13.46 and 16.49, respectively) from the pilot trial samples were used. PASS 16 Power Analysis and Sample Size Software (2018) NCSS, LLC. (Kaysville, UT, USA) was used for the power calculation. All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Participants who discontinued their participation in this study contributed data for all time points completed prior to withdrawal.

3. Results

Forty-four patients scheduled for TKA were approached for enrollment (Figure 1). Twenty patients were enrolled and randomized to the feedback group (n = 8) or the routine care group (n = 10). Nineteen patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, and six declined participation. Two patients withdrew after enrollment: one due to revision surgery for infection and one by personal request. Eighteen patients were included in the final analysis, and seventeen completed the 6-week follow-up. Baseline demographics were comparable between groups with respect to age, sex, ASA classification, and BMI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics.

In addition to standard-of-care aftercare, the feedback group performed home exercises for a mean duration of 21.05 ± 7.55 min per day for a total of 327.05 ± 219.82 min over the total intervention. This is 91% compliant with the total amount of training with respect to our recommendation of 15 min a day for 24 days.

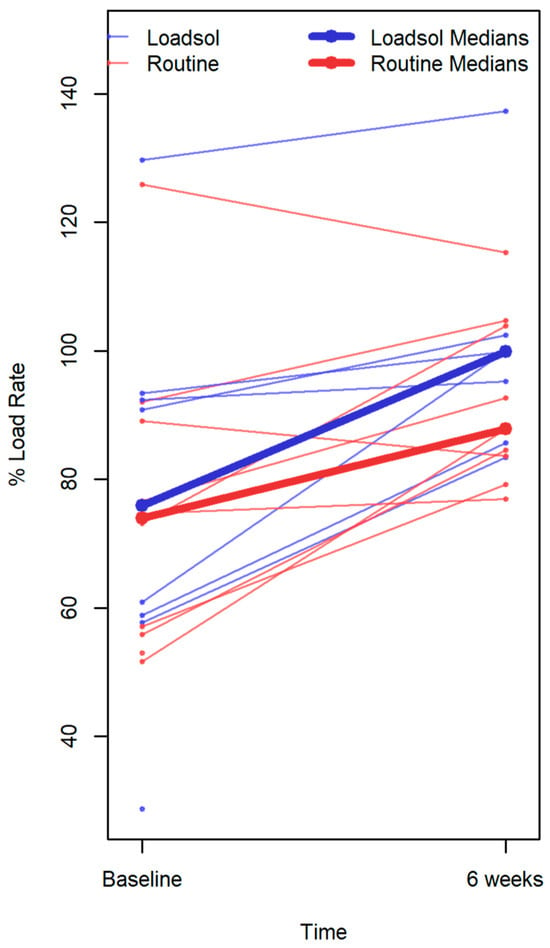

3.1. Percent Load Rate

The median percent load rate increased from 75.9 to 99.9 in the feedback group and from 73.9 to 87.8 in the routine care group (Table 2). The between-group difference in change over 6 weeks was not statistically significant (p = 0.92) (Table 3). Both groups also demonstrated increases in gait speed and cadence over time, while detailed secondary gait parameters are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of gait measures over time.

Table 3.

Comparison of gait measures over time: 6 weeks–baseline.

3.2. Patient Reported Outcomes

Both groups demonstrated improvements in pain and functional PROMs over the 6-week follow-up period (Table 4). Median improvements were observed in Physical Health, PF CAT, KOOS Jr, and Global Pain scores in both groups (Table 5). The median changes did not differ significantly between the feedback and routine care groups for any PROM outcome.

Table 4.

Summary of PROMs over time.

Table 4.

Summary of PROMs over time.

| Variable * | Type/Level | Loadsol Baseline: N = 8 | Loadsol 6 Weeks: N = 8 | Routine Care Baseline: N = 10 | Routine Care 6 Weeks: N = 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF CAT | [median (IQR)] | 35 (29, 39) | 38 (37.5, 41) | 39 (33, 41.5) | 40.5 (38.8, 44.2) |

| Physical Health | [median (IQR)] | 40 (38.5, 45) | 48 (45, 51) | 40 (40, 40) | 46.5 (41.5, 48) |

| Mental Health | [median (IQR)] | 56 (54.5, 56) | 56 (53, 56) | 48 (44, 53.5) | 52 (46.2, 53) |

| Global Pain | [median (IQR)] | 60 (45, 65) | 20 (20, 35) | 60 (45, 75) | 50 (40, 50) |

| KOOS Jr | [median (IQR)] | 50 (42.5, 61) | 59 (56, 66) | 55 (52, 57) | 57 (49.5, 76.5) |

| Numeric Pain Scale—Walking | [median (IQR)] | 2.5 (1, 3) | 2 (0.5, 2.5) | 4.5 (4, 5.8) | 3 (3, 4) |

| Numeric Pain Scale—Resting | [median (IQR)] | 2.5 (2, 3.2) | 1 (0, 2) | 4.5 (3.2, 5.8) | 3 (2, 4) |

* Missing values: PF CAT = 6; Physical Health = 6; Mental Health = 6; Global Pain = 6; KOOS Jr = 7; Numeric Pain Scale—Walking = 1; Numeric Pain Scale—Resting = 1. Abbreviations: PF CAT = Physical Function Computerized Adaptive Test; IQR = interquartile range; KOOS Jr = Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Junior.

Table 5.

Comparison of PROMs over time: 6 weeks–baseline.

Table 5.

Comparison of PROMs over time: 6 weeks–baseline.

| Variable * | Type/Level | Loadsol (N = 8) | Routine Care (N = 10) | p-Value | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF CAT | [median (IQR)] | 1.5 (−2, 7.2) | 5 (1.2, 8) | 0.92 | 6 |

| Physical Health | [median (IQR)] | 4 (3, 7.2) | 5.5 (2.2, 8) | 0.77 | 6 |

| Mental Health | [median (IQR)] | −1.5 (−3, 2.2) | 2 (−1.5, 6.2) | 0.33 | 6 |

| Global Pain | [median (IQR)] | −40 (−40, −17.5) | −30 (−30, −7.5) | 0.29 | 6 |

| KOOS Jr | [median (IQR)] | 7.5 (3, 11.2) | 0 (−7.5, 6.8) | 0.33 | 6 |

| Numeric Pain Scale—Walking | [median (IQR)] | −1 (−1.5, 1) | −1 (−2, 0) | 0.62 | 6 |

| Numeric Pain Scale—Resting | [median (IQR)] | –1 (−2, 0) | −2 (−2, −1) | 0.70 | 6 |

* Missing values: PF CAT = 6; Physical Health = 6; Mental Health = 6; Global Pain = 6; KOOS Jr = 6; Numeric Pain Scale—Walking = 2; Numeric Pain Scale—Resting = 2. 1 = t-test; 2 = Wilcox, 3 = chi-square; 4 = Fisher’s exact; 5 = Fisher’s exact test with simulation; 6 = exact Wilcoxon rank sum test. Abbreviations: PF CAT = Physical Function Computerized Adaptive Test; IQR = interquartile range; KOOS Jr = Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Junior.

3.3. Power Calculation

Based on the observed effect sizes in this feasibility study, a future randomized trial would require approximately 588 participants per group to achieve 80% power to detect between-group differences at a two-sided significance level of 0.05 (Table S1).

4. Discussion

This feasibility study evaluated the use of a home-based real-time biofeedback insole device as an adjunct to standard physiotherapy following unilateral total knee arthroplasty. High adherence to the prescribed training protocol was observed, indicating good feasibility and acceptance of the device in a home setting. While improvements in percent loading rate, gait speed, and patient-reported outcomes were observed over six weeks in both groups, no statistically significant between-group differences were detected.

Previous studies have shown that post-TKA patients load significantly less weight on the surgical limb compared to the non-surgical limb [14]; this observation is consistent with trends observed in our data. A randomized controlled trial could show that biofeedback training after TKA leads to a lower peak extension moment on the contralateral knee during walking. This could directly influence the progression of osteoarthritis on the contralateral limb [15]. Christiansen et al. reported that not all patients have asymmetrical weight-bearing patterns [16,17]. In this study population, only one patient in each group presented with this unexpected gait pattern (Figure 6, the two lines that start above 100%). The responsiveness of both patient-reported and performance-based outcome measures differs from each other, as patient perception fails to capture the acute functional declines after TKA and may overstate the long-term functional improvement with surgery [18].

Figure 6.

Each line represents the percent loading rate of an individual patient. Data points without connecting lines indicate patients with only one measurement. Bold lines represent the group median at each time point (baseline and 6 weeks), highlighting the overall change within each group. This distinction allows visualization of individual variability alongside the central tendency of the feedback and control groups.

Biofeedback in a home-based setting is potentially acceptable as an adjunct to physiotherapy intervention for outpatients following total knee replacement [19]. Additionally, Castellarin et al. demonstrated that the rise of patient accountability and deeper involvement of patients during recovery led them to a higher level of activity and improved results and compliance [20]. The findings of this feasibility study are in line with conclusions reported by Fung et al. and Christiansen et al. in similar settings, although no statistically significant between-group differences were observed. Both audio and visual biofeedback were provided in this study, so the patients can decide what they prefer and want to use. Multiple studies and reviews discussed whether audio or visual feedback is more helpful; however, there have been no definitive results [5,21,22,23,24]. The recommended use of 15 min of daily biofeedback training is similar to what previous studies have used and is a compromise between sufficient high intensity and expected compliance [19,21,22,24,25,26].

A major limitation of previous studies is the artificial training situation in a gait laboratory. Therefore, it is the biggest strength and achievement of this study to show that real-time biofeedback with a wearable device in unilateral TKA patients is a safe and feasible adjunct to normal physiotherapy. The high compliance of 91% for the recommended time of 15 min daily indicates that the device is used by the patients according to the recommendations, and the fact that only one patient wished to be withdrawn shows that it is relatively easy to use. Moreover, Rynne et al. conducted a meta-analysis that demonstrated that gait retraining strategies in combination with a biofeedback tool may be effective in reducing the knee adduction moment (KAM) [27].

A major limitation of this study is the small study group. This is due to the fact that we first wanted to evaluate confounding factors and show that adequate home-based training is possible before moving forward with a larger randomized control trial. From a feasibility perspective, 20 of 44 approached patients were enrolled, with 2 withdrawals and no reported device-related adverse events. High adherence (91%) and low dropout further support the feasibility of home-based real-time biofeedback in this patient population. The data of this feasibility study allowed us to perform a power calculation to determine the necessary group sample sizes for a future study. With 588 patients in each group, this would be a large clinical study. These group sizes are due to the fact that, in this study, biofeedback was used as an add-on to normal physiotherapy. These findings suggest that future studies may consider directly comparing standard physiotherapy with home-based biofeedback alone in order to better isolate potential effects.

A ceiling effect due to high gait symmetry during routine rehabilitation may have limited the observable benefit of biofeedback in this cohort. This suggests that patients with more pronounced baseline asymmetry may represent a subgroup in which real-time biofeedback could be more effective, warranting further investigation in future studies. This feasibility study shows that it is possible to provide patients with a home-based real-time biofeedback following unilateral TKA on an app-based mobile insole device.

5. Conclusions

This feasibility study demonstrates that providing patients with a home-based, real-time biofeedback system using a mobile insole device after unilateral total knee arthroplasty is feasible and safe, with high adherence and no device-related adverse events. Trends toward improvements in gait parameters and patient-reported outcomes were observed, although these did not reach statistical significance. These findings suggest potential benefits of real-time biofeedback, but its clinical efficacy remains uncertain. Further, larger studies are needed to determine whether home-based biofeedback provides additional benefit beyond standard physiotherapy and to optimize study design for future trials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/surgeries7010002/s1. Table S1, provided as supplementary material, details the power calculation used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P. and C.E.P.; methodology, M.B.A.; software, J.B.; validation, R.H., C.L. and C.E.P.; formal analysis, J.G.; investigation, D.P.; resources, D.P.; data curation, M.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.H.; visualization, J.B.; supervision, C.E.P.; project administration, M.B.A.; funding acquisition, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from a commercial entity, including but not limited to Zimmer Biomet, Medacta, Stryker, Enovis, Total joint Orthopedics, and Smith & Nephew. This research was funded by “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/Max Kade Foundation, Postdoctoral Research Fellowship”, grant number PF 939/1-0, and the “LS Peery Research Foundation Seed Grant”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03673293) on 14 September 2018. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Utah (IRB_00110935) on 10 September 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions involving human subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

Daniel Pfeufer: No conflicts of interest. Mike Anderson: Financial benefit from Zimmer Biomet. Jeremy Gilliland: No conflicts of interest. Robert Hube: No conflicts of interest. Christoph Linhart: No conflicts of interest. Julius Brendler: No conflicts of interest. Christopher Pelt: No conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kagan, R.; Anderson, M.B.; Christensen, J.C.; Peters, C.L.; Gililland, J.M.; Pelt, C.E. The Recovery Curve for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Patient-Reported Physical Function and Pain Interference Computerized Adaptive Tests After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 2471–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, P.C.; Gordon, M.J.; Weiss, J.M.; Reddix, R.N.; Conditt, M.A.; Mathis, K.B. Does total knee replacement restore normal knee function? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 431, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.R.; Jennings, J.M.; Watters, T.S.; Levy, D.L.; McNabb, D.C.; Dennis, D.A. Femoral Implant Design Modification Decreases the Incidence of Patellar Crepitus in Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkilä, A.; Sevander-Kreus, N.; Häkkinen, A.; Vuorenmaa, M.; Salo, P.; Konsta, P.; Ylinen, J. Effect of total knee replacement surgery and postoperative 12 month home exercise program on gait parameters. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeufer, D.; Gililland, J.; Böcker, W.; Kammerlander, C.; Anderson, M.; Krähenbühl, N.; Pelt, C. Training with biofeedback devices improves clinical outcome compared to usual care in patients with unilateral TKA: A systematic review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 27, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.A.; Crossley, K.M.; Davis, I.S. Gait retraining to reduce the knee adduction moment through real-time visual feedback of dynamic knee alignment. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 2208–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwell, J.B.; Davis, B.L.; Frazier, D.M. Use of an instrumented treadmill for real-time gait symmetry evaluation and feedback in normal and trans-tibial amputee subjects. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 1996, 20, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeufer, D.; Monteiro, P.; Gililland, J.; Anderson, M.B.; Böcker, W.; Stagg, M.; Kammerlander, C.; Neuerburg, C.; Pelt, C. Immediate Postoperative Improvement in Gait Parameters Following Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty Can Be Measured with an Insole Sensor Device. J. Knee Surg. 2020, 35, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, H.; Hirschmüller, A.; Müller, S.; Gollhofer, A.; Mayer, F. Muscular activity in treadmill and overground running. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2007, 15, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; King, G.A. Dynamic gait stability of treadmill versus overground walking in young adults. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 31, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeufer, D.; Becker, C.A.; Faust, L.; Keppler, A.M.; Stagg, M.; Kammerlander, C.; Böcker, W.; Neuerburg, C. Load-Bearing Detection with Insole-Force Sensors Provides New Treatment Insights in Fragility Fractures of the Pelvis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeufer, D.; Grabmann, C.; Mehaffey, S.; Keppler, A.; Böcker, W.; Kammerlander, C.; Neuerburg, C. Weight bearing in patients with femoral neck fractures compared to pertrochanteric fractures: A postoperative gait analysis. Injury 2019, 50, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeufer, D.; Zeller, A.; Mehaffey, S.; Böcker, W.; Kammerlander, C.; Neuerburg, C. Weight-bearing restrictions reduce postoperative mobility in elderly hip fracture patients. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2019, 139, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Zeni, J.; Snyder-Mackler, L., Jr. Do Patients Achieve Normal Gait Patterns 3 Years After Total Knee Arthroplasty? J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bade, M.J.; Christiansen, C.L.; Zeni, J.A., Jr.; Dayton, M.R.; Forster, J.E.; Cheuy, V.A.; Christensen, J.C.; Hogan, C.; Koonce, R.; Dennis, D.; et al. Movement Pattern Biofeedback Training After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2024, 77, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, C.L.; Bade, M.J.; Davidson, B.S.; Dayton, M.R.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E. Effects of Weight-Bearing Biofeedback Training on Functional Movement Patterns Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 45, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, C.L.; Bade, M.J.; Judd, D.L.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E. Weight-Bearing Asymmetry During Sit-Stand Transitions Related to Impairment and Functional Mobility After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizner, R.L.; Petterson, S.C.; Clements, K.E.; Zeni, J.A.; Irrgang, J.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Measuring Functional Improvement After Total Knee Arthroplasty Requires both Performance-Based and Patient-Report Assessments: A Longitudinal Analysis of Outcomes. J. Arthroplast. 2011, 26, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, V.; Ho, A.; Shaffer, J.; Chung, E.; Gomez, M. Use of Nintendo Wii Fit (TM) in the rehabilitation of outpatients following total knee replacement: A preliminary randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2012, 98, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, G.; Merlini, M.; Bettinelli, G.; Riso, R.; Bori, E.; Innocenti, B. Effect of an Innovative Biofeedback Insole on Patient Rehabilitation After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, T.A.; Amir, H.; Scheidt, R.A. Computerized biofeedback knee goniometer: Acceptance and effect on exercise behavior in post-total knee arthroplasty rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Chang, C.F.; Lou, M.F.; Ao, M.K.; Liu, C.C.; Liang, S.Y.; Wu, S.-F.V.; Tung, H.-H. Biofeedback Relaxation for Pain Associated with Continuous Passive Motion in Taiwanese Patients After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Res. Nurs. Health 2015, 38, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Frańczuk, M.; Zemła, J.; Sliwiński, Z. The application of biofeedback exercises in patients following arthroplasty of the knee with the use of total endoprosthesis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2010, 16, CR423–CR426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeni, J.; Abujaber, S.; Flowers, P.; Pozzi, F.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Biofeedback to Promote Movement Symmetry After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Feasibility Study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.T.; Hwangbo, G. The effects of proprioception exercise with and without visual feedback on the pain and balance in patients after total knee arthroplasty. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanb, A.S.A.; Youssef, E.F. Effects of Adding Biofeedback Training to Active Exercises After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Musculoskelet. Res. 2014, 17, 1450001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynne, R.; Le Tong, G.; Cheung, R.T.H.; Constantinou, M. Effectiveness of gait retraining interventions in individuals with hip or knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture 2022, 95, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.