Abstract

Background: The development of CAD, FEA, and biomechanical models of the shoulder is challenging due to the joint’s complexity. The spatial relationships between bones, muscles and ligaments are difficult to parameterize, both statically and dynamically, because these structures move three-dimensionally and synergistically. Methods: An assembly of the shoulder joint was developed, including parameterisation of the positional relationships among the rotator cuff structures, with particular focus on the bone components: Humerus, Scapula, Clavicle, and Sternum. Discussion: The abundance of existing CAD models of the shoulder makes it difficult to compare numerical results. Variability in reference frames, positioning assumptions and geometric relationships often hinders reproducibility and cross-study interpretation. Conclusions: The presented methodology supports standardised assembly of a shoulder joint model, ensuring consistent assumptions about the relative positioning of the bony structures. This standardization enables more accurate numerical comparisons across studies and improves the reliability of biomechanical research on the shoulder.

1. Introduction

The shoulder system is a mechanism that gathers a constellation of bones, including the Sternum, Clavicle, Scapula, and Humerus, forming the connection between the trunk and upper extremity [1]. In the early 20th century, several researchers built a physical model of the shoulder using data collected from shoulder specimens and replaced cadaveric muscles with cords running from their origin to their insertion points. Posteriorly, in the 1980s and 1990s, the arrival of powerful computers initiated the development of more complex musculoskeletal models [1,2,3].

In 1992, Helm et al. [1] developed a dynamical finite element model of the shoulder based on a large number of cadaveric data points acquired for each of the morphological structures of the joint. Subsequently, they used to parametrize the arc form of each structure.

Nowadays, after more than thirty years passed, shoulder subject-specific models have been developed with different levels of detail, ranging from simple scaling methods to full 3D reconstruction from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computer tomography scans (CT scans) [4,5,6]. All these possibilities relay on the initial configuration of the shoulder system that is also the position in which the subject was measured and not in the anatomical position. MRI or CT-scans requires patients to be in the supine position. Nevertheless, the Scapular orientation and patient posture influence the normal range of the shoulder joints, i.e., glenohumeral, acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints [5,7,8]. Moreover, in the reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, the ideal retroversion angle associated with the humeral prosthesis component is related to the Scapula orientation [5]. Still, rotator cuff tear pathologies can also be affected by this information [9,10,11].

Finite element models of the shoulder can be used to study and validate surgical procedures, as the case of work developed by Bola et al. [12], in which a finite element model that replicated an experimental simulator of an implanted joint shoulder was developed based on the comparison of measured and calculated strains. Numerical procedures are suitable for studying and developing new material for some or all prosthesis components [13] and for predicting their short- and medium-term performance [14]. The generality of these studies and the musculoskeletal models rely on shoulder joint loads that were measured in vivo for patient-specific conditions and movements [15]. Moreover, the three-dimensional CAD assemblies of the joint are created without specifying the initial reference conditions used to ensure abduction and flexion angle positioning. A significant number of works are based on the information presented in the work of Garner and Pandy [16], which enables the three-dimensional reconstruction of muscle and bone surfaces from Computed Tomography (CT) images and Colour Cryosection images obtained from the Visible Human Project (VHP) cadavers and other databases.

This study aimed to propose a user-friendly 3D reconstruction method of the shoulder joint based on 3D geometrical models of their different components and to assess its accuracy. Clinical parameters and a coordinate system were determined, and calculations based on anatomical landmarks extracted from the 3D reconstructions. The reproducibility of these parameters and of the chosen scapular coordinate system was also assessed to further evaluate the method [6].

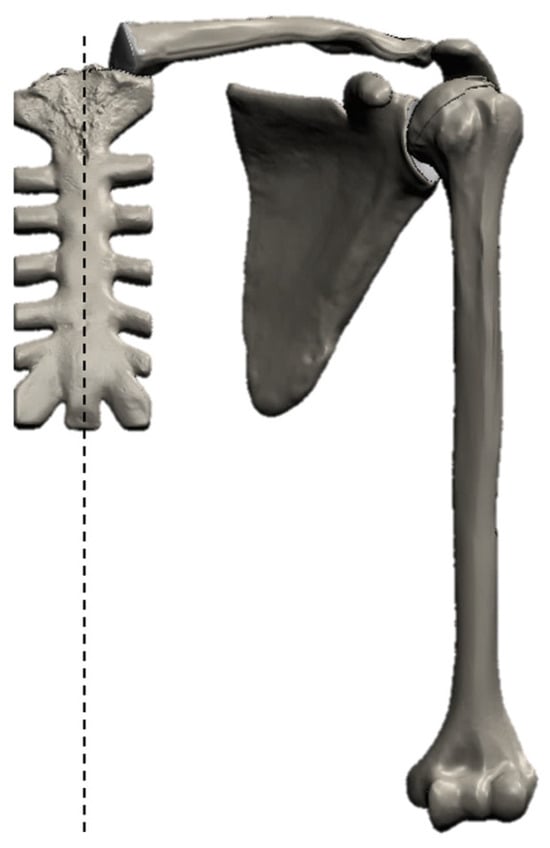

2. Components and Models

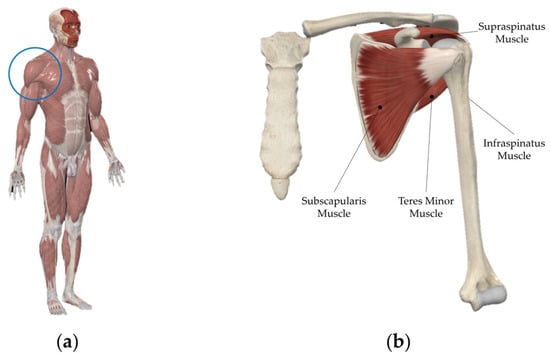

The shoulder, and particularly the glenohumeral joint, provides the greatest range of movement among all diarthrodial joints, also presenting a greater propensity for instability. Due to the multiple joints involved during shoulder movement, it is prudent to refer to it as the shoulder complex [17,18]. It is placed in the upper limb of the human body, as represented in Figure 1. The anatomical figures included in this work were adapted from the Complete Anatomy software from Elsevier, version 11.7.3.

Figure 1.

Shoulder location in the Human body identified in blue circle (a) and the Shoulder joint (b).

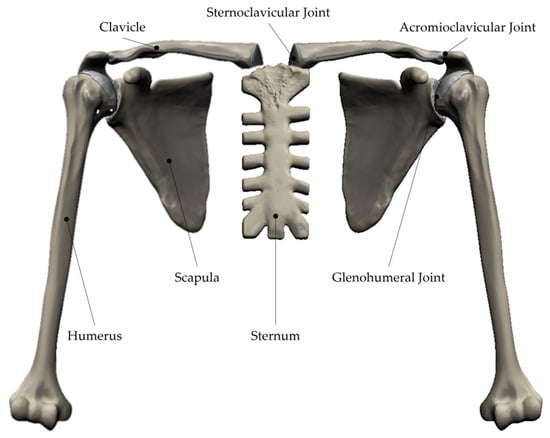

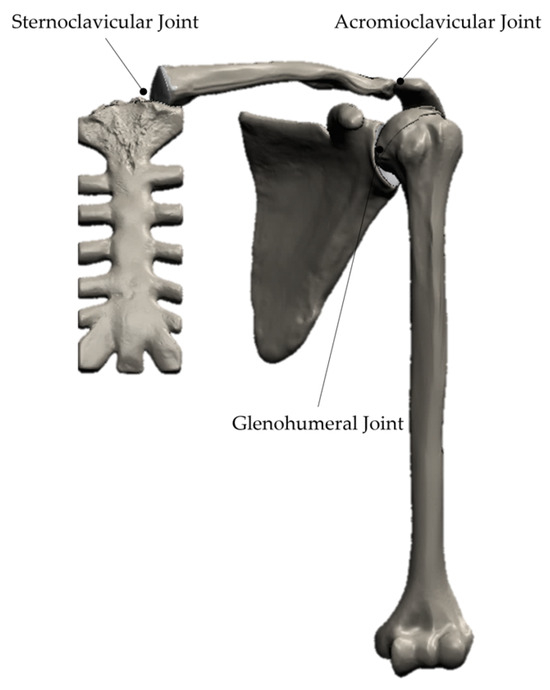

Generally, when approaching this joint, only the bone structures of the Humerus, Scapula and Clavicle are considered [16]. In more simplified approaches, only the Humerus and the Scapula are considered. However, this joint complex must consider the presence of the Sternum, since the main fulcrum of rotation of the shoulder takes place precisely in the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 2). Therefore, the Sternum was considered for this parameterization.

Figure 2.

Shoulder Complex with main bony structures and joints—Anterior View.

In the shoulder, it can be practical to consider two types of rotations: joint rotation and segment rotation [19]. The joint rotation takes into account the rotation of a segment with respect to the proximal segment, such as the Clavicle relative to the Sternum (sternoclavicular joint), the Scapula relative to the Clavicle (acromioclavicular joint), and the Humerus relative to the Scapula (glenohumeral joint). On the other hand, the segment rotation considers the rotation of the Clavicle, Scapula, or Humerus relative to the Sternum. The definition of joint displacements is only useful if it is defined with respect to the proximal segment [19].

Therefore, for this study, the four main bone structures present in Figure 2 were considered: Humerus, Scapula, Clavicle, and Sternum.

In addition to the glenohumeral joint, the shoulder joint complex is composed of two other main joints, the sternoclavicular joint and the acromioclavicular joint, which together contribute to the kinematics of the scapulothoracic functional joint (Figure 2).

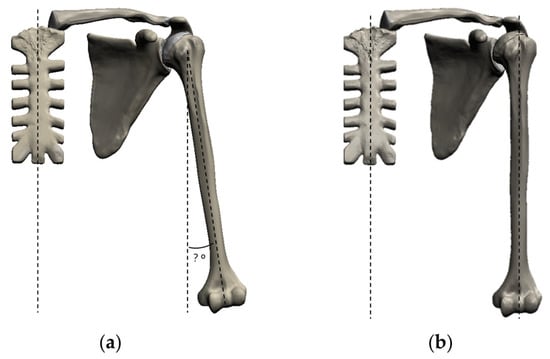

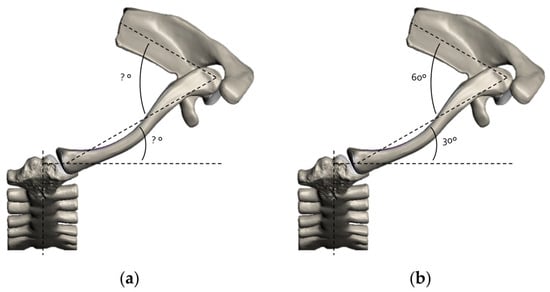

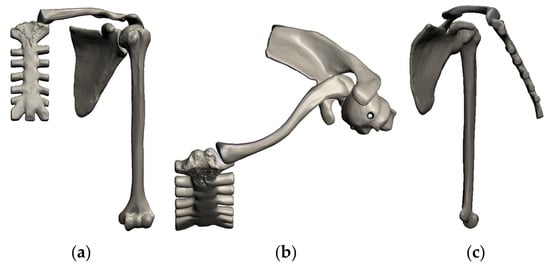

Amongst the inclusion of the Sternum as a fundamental part of the shoulder complex, and thus to be considered for studies and analysis of this human joint, including the sternoclavicular joint as the main fulcrum of all movement, implies that the initial position of the joint complex is not coincident with the anatomical position of the Humerus (Figure 3). This difference is illustrated in the images of Figure 3. In Figure 3a, the shoulder complex is represented in its anatomical position. In contrast, Figure 3b represents the aforementioned joint complex, but with the anatomical axis of the Humerus aligned vertically with the anatomical longitudinal axis.

Figure 3.

Anterior View of Shoulder Complex angle [?°] alignment (dotted lines): with unknown initial anatomical alignment (a) and mechanical initial alignment (b).

Considering another position, such as the anatomical one, in which the Humerus is not vertically aligned, can be a variable that is difficult to parameterize, as it depends on several factors, such as anatomical ones, namely its physical complexion (fat mass, muscle mass, anthropometric measurements, etc.) and the way in which the imaging data obtained by computed tomography were acquired, as different acquisition positions give rise to different anatomical representations [20]. Therefore, when considering the alignment of the aforementioned axes (anatomical axis of the Humerus and anatomical longitudinal axis), the starting point for any study is always the same.

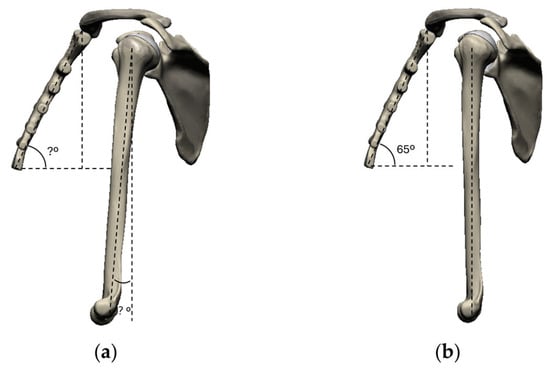

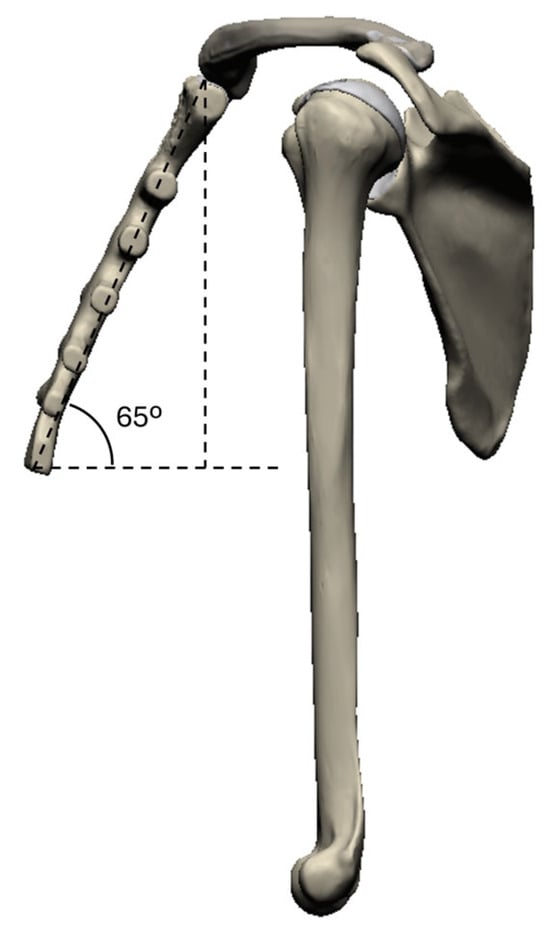

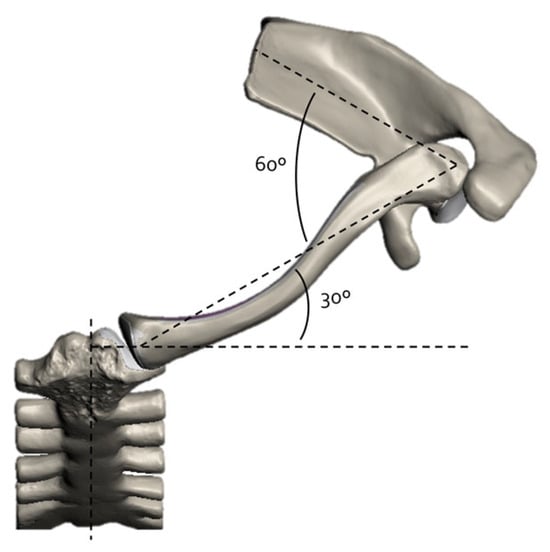

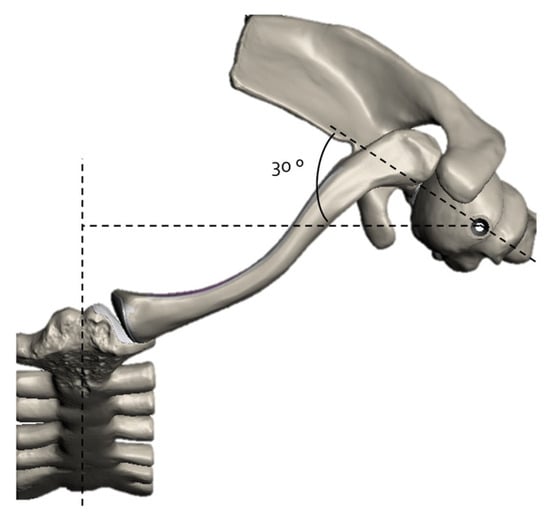

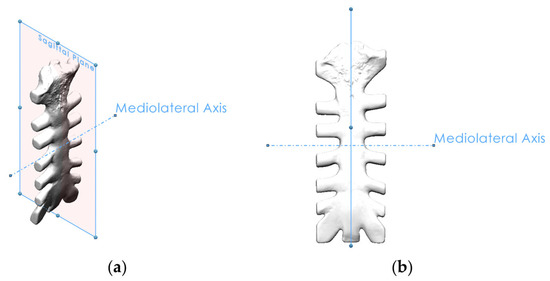

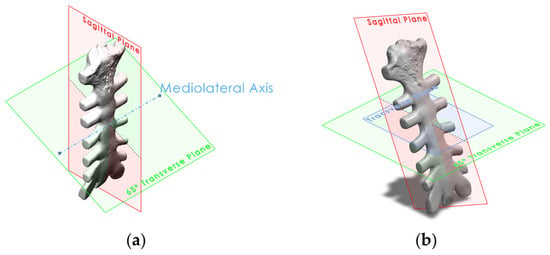

The uncertainty in the relative positioning of the bony structures that comprise the shoulder joint is not only evident in the frontal view, as described previously. Also in the lateral view, the anatomical position of the Sternum is not determined in the available shoulder models (Figure 4a). In the model shown here, the Sternum is rotated 65° around the mediolateral axis (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Lateral View of Shoulder Complex angle [?°] alignment (dotted lines): with unknown anatomical alignment (a) and parameterized initial alignment (b).

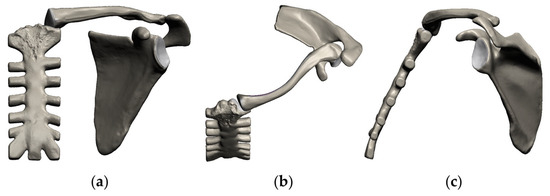

Finally, in Figure 5 it can be seen that the models commonly used do not have a predetermined relative position for the bony elements, or in other words, the relative position is not known (Figure 5a), but the methodology here proposed defines the relative position between the Clavicle and the Sternum, and the initial relative position between the Scapula and the Clavicle as illustrated in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

Superior View of Shoulder Complex angle [?°] alignment (dotted lines): with unknown anatomical alignment (a) and parameterized initial alignment (b).

Due to its anatomical and functional complexity, which often results in instability and pain, it has been the subject of study in various fields of science, including medicine, orthopaedics, physiatry, and rheumatology, as well as mechanical engineering and, in particular, biomechanics, in an attempt to understand and resolve associated pathologies.

Also, due to its intrinsic instability, it is the target of numerous pathologies with different origins, whether traumatic or degenerative, which arouses interest in these areas of knowledge.

The models of these joints are typically created based on computerised tomography images (CT scans) of cadavers and data obtained through dynamic/inverse kinematic analysis for biomechanical studies of this structure. This approach always depends on the models/individuals that served as a basis, their number, for statistical validation, and, not least, the image acquisition position, since the positioning of the different bone structures differs in the lying and standing positions [20]. Therefore, comparisons between results based on different models may be biased. What is proposed here as a methodology for assembling the shoulder complex, using standard and certified models of independent bone elements, such as those from Sawbones® (Pacific Research Laboratories, Inc., Vero Beach, FL, USA), will allow comparability of results between different studies.

The research carried out allowed for an understanding of the spatial relationship between the different bone segments that make up this joint complex, as well as their synergistic movement.

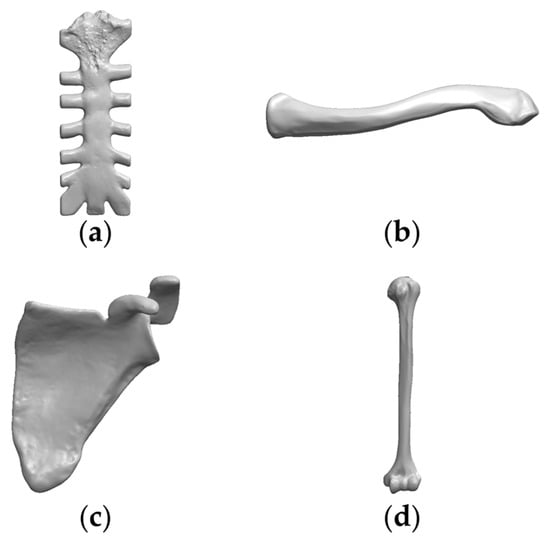

3. Digital CAD Models

To develop this methodology, the following digital CAD models from the company Sawbones® were considered (Figure 6): #3900-31—Sternum, Large, Digital file of #1025 (a); #3900-50—Clavicle, Large, Left, Full, Digital file of #3408-1 (b); #3957—Scapula, Large, Left, Digital file of #3413 (c); #3907—Humerus, Large, Left, Digital file of #3404 (d).

Figure 6.

Shoulder Bones Digital CAD Models: (a) Sternum, (b) Clavicle, (c) Scapula, (d) Humerus (Sawbones®).

All original CAD digital models did not contain any initial anatomical reference parameters, namely planes, axes, and regions, or others. So, they were identified and parameterized, thus making their correct positioning in space and assembly possible. It should be noted that the Sternum was taken as a fixed reference, as mentioned, it is the central fulcrum of rotation of this joint and will allow the Scapulohumeral Rhythm to be represented.

In this work, SolidWorks® software, version 2025, was used to develop the shoulder joint assembly and to create all figures that represent the methodology steps.

3.1. Sternum

The Sternum is a flat bone located in the axial skeleton, more precisely in front of the thoracic cavity, where the first seven pairs of ribs come to attach (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Sternum: Anterior View.

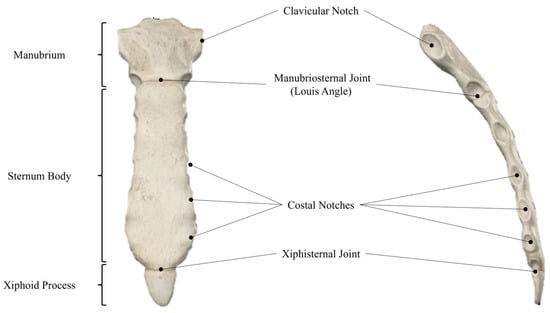

It comprises three parts: manubrium (the upper part), body (central part) and the appendix or xiphoid process (the lower part) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Sternum: Anterior View (left), Lateral View (right).

It is precisely in the manubrium that the first connection to the shoulder complex is present through the clavicular notch, which, as the name suggests, is where the Sternum and Clavicle articulate, i.e., where the sternoclavicular joint appears.

Hence, it will serve as the reference point for assembling the entire shoulder joint complex, and for simplicity, it is fixed in space.

Nevertheless, the Sternum orientation is the initial reference for the complete assembly of the shoulder joint. Its axis of symmetry, the longitudinal axis, is parallel to the sagittal plane of anatomical reference and coincides with the medial plane, which is the plane of vertical symmetry in the human body. Therefore, its positioning entirely coincides with the sagittal plane of the human body, meaning that its vertical symmetry plane will also coincide with the aforementioned plane already defined for assembly (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Sternum: Anterior View of Anatomical Position: vertical alignment in dotted line.

Regarding the lateral view of its anatomical positioning, the Sternum is rotated 65° about the mediolateral axis [21], as seen in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Sternum: Lateral View of Anatomical Angle (dotted lines).

3.2. Clavicle

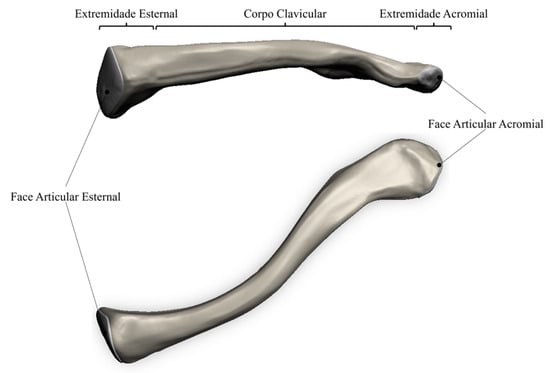

The Clavicle (Figure 11) is an elongated “S” shaped bone that rests horizontally along the upper rib cage, as represented in Figure 11. It articulates medially with the Sternum and laterally with the Acromial Process of the Scapula to form the Scapular Girdle.

Figure 11.

Clavicle: Anterior View.

It belongs to the appendicular skeleton and comprises three main segments: Sternal End, Clavicular Body, and Acromial End. Through the Sternal Facet, it connects to the Sternum and contacts the acromion through the Acromial Facet (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Clavicle: Anterior View (top), Superior View (bottom).

Concerning its anatomical positioning, the Clavicle is in a flat/horizontal position, as can be seen in the previous Figure 11.

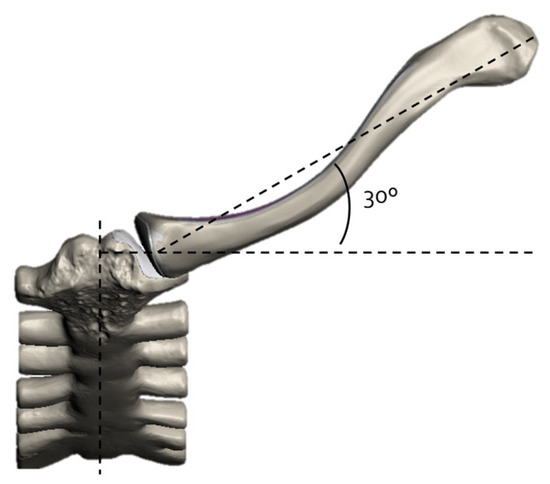

Regarding its superior view of its anatomical positioning, the Clavicle is rotated 30° about the longitudinal axis [22], as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Clavicle: Superior View of Anatomical Angle (dotted lines).

3.3. Scapula

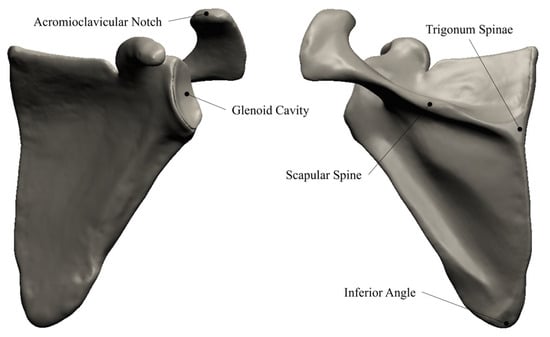

The Scapula is a flat, triangular bone that surrounds the posterior wall of the chest and extends from the first to the seventh rib. Figure 14 shows its anterior and lateral views. It is spatially positioned on the rib cage, taking the shape of an inverted triangle shape.

Figure 14.

Scapula: Anterior View.

The anterior concave surface, called the subscapular fossa, is in contact with the thoracic cage and is one of the articular surfaces of the scapulothoracic interface. The Scapula posterior surface is convex and irregular, and the spine divides its geometry into two regions: the supraspinous and infraspinous fossa. The ratio of both surfaces is 1/4 to 3/4 [23].

The Scapula has several notable areas worth highlighting, mainly because they are regions where other bony elements articulate, or the insertion of muscles that are fundamental for the movement or stability of the shoulder occurs. For instance, the Glenoid Cavity, which corresponds to one of the fundamental elements of the shoulder blade, is located in its upper lateral region. This cavity is an irregular depression/concavity, with an oval outline and surrounded by the glenoid margin, oriented outward and upward, slightly retroverted [24]. Together with other elements, mainly the Humerus, it allows the glenohumeral joint to materialize (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Scapula: Anterior View (left) and Posterior View (right).

Other important anatomical scapular landmarks are the Trigonum Spinae, the scapular Spine and the Inferior Angle, as they provide valuable information on the position of the scapula. In particular, the trigonum spinae is a point of particular interest as it is critical to specific clinical parameters (the morphological inclination of the glenoid and glenoid version), and to compute coordinate systems. Hence, it is helpful to characterize the shape and the position of the Scapula [6].

In addition to the glenohumeral joint, the acromion region of the Scapula and the Clavicle bone allow for the creation of another articulation: the acromioclavicular joint. This joint is created between the Clavicle bone and an area of the Scapula that continues after the spine region and is classified as the acromion. The acromion region of the Scapula acts with a structural and support function to the acromioclavicular joint. Still, it also acts as a protection mechanism (given that it is a protruding area of the Scapula), simultaneously providing insertion points for shoulder muscles.

Regarding the lateral view of its anatomical positioning, the Scapula is rotated 60° about its longitudinal axis [22], as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Scapula: Superior View of Anatomical Angles (dotted lines).

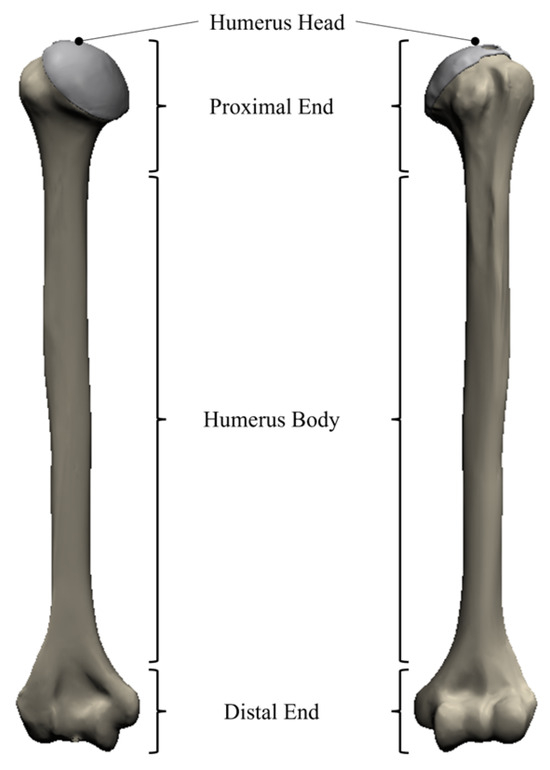

3.4. Humerus

The Humerus corresponds to the largest bone of the upper limb, falling into the category of long bones, articulating with the shoulder blade, materializing the glenohumeral joint (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Humerus: Anterior View.

The Humerus can be divided into three fundamental regions: the proximal end, the body and the distal end (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Humerus: Anterior View (left), Posterior View (right).

The Humerus head is located in the proximal region of the Humerus and, together with the glenoid, forms the glenohumeral joint. The head of the Humerus is an approximately spherical region (about one-third of a sphere [21,22]), oriented upward, inward, and slightly backward. The angle formed between the axis of the head and the diaphysis (cervical-diaphyseal angle) is approximately 135° [21,22]. Like the cavity, the head of the Humerus is covered by a layer of articular cartilage which, among other things, reduces friction in the contact between the two bone structures (typical of synovial joints), minimizing the effects of wear and enhancing the mobility of the joint in question. One of the main anatomical properties of the Humerus is the retroversion, or “declination”, of the humeral head neck axis by 30° relative to the Coronal Plane (Figure 19) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Figure 19.

Humerus: Superior View of Anatomical Angle (dotted lines).

4. Shoulder Joints

As mentioned, the shoulder complex is made up of three main joints: the sternoclavicular, the acromioclavicular joint and the glenohumeral joint, in addition to a functional scapulothoracic joint, as can be seen in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Shoulder Complex Joints—Anterior View.

Taking the Sternum as a starting point and moving towards the Humerus, since it can be the last bone segment to consider in the shoulder complex, the order of bone elements in the complex should be regarded as follows: Sternum, Clavicle, Scapula, and Humerus. Therefore, according to this order, the joints described below are the sternoclavicular joint, the acromioclavicular joint and the glenohumeral joint (Figure 20).

4.1. Sternoclavicular Joint

The connection between the shoulder girdle and the axial skeleton is made punctually by the sternoclavicular joint, which is the only synovial joint existing between the axial skeleton and the upper limb. As its name suggests, it forms the connection between the Clavicle and the manubrium of the Sternum (Figure 21), and corresponds to a saddle synovial joint, with moderate mobility [22].

Figure 21.

Sternoclavicular Joint location—Anterior View.

The bony surfaces that constitute the sternoclavicular joint correspond to the anteroinferior region of the sternal end of the Clavicle and the outer surface of the manubrium of the Sternum [22]. These are also covered by cartilage that minimizes the wear and tear caused by the relative displacement of the two surfaces during movement of the upper limb. In the case of the Clavicle, the cartilage covers only 2/3 of the lateral surface of the sternal facet, with the remaining 1/3 serving for the insertion of ligaments and other anatomical structures. Concerning the Sternum, in the clavicular notch, the cartilage also covers approximately 2/3 of the mentioned facet [23]. Although the articular surfaces of the sternoclavicular joint are saddle-shaped, the joint is a ball-socket joint with three degrees of freedom [17]: elevation and depression, protraction and retraction, and the Clavicle can rotate about its longitudinal axis.

4.2. Acromioclavicular Joint

The acromioclavicular joint, as the name suggests, materializes the connection between the Clavicle and the Scapula at the Acromion bony process (Figure 22). Since it is a flat synovial joint, it is associated with a relatively reduced degree of mobility, meaning that relative movement between the two bone structures involved in the connection is not perfectly evident. For this reason, it is a robust and relatively rigid joint, where stability is favoured over mobility. The acromioclavicular joint is a plane joint with an articular disc which permits motion in all planes between the Clavicle and acromion, including axial rotation of the Clavicle. The articular capsule is very weak, and the joint depends for its stability on the strong coracoclavicular ligament, which binds the Clavicle to the Scapula [31].

Figure 22.

Acromioclavicular Joint location—Anterior View.

Its support function is equally evident in the contribution it makes to the kinematic chain associated with the human shoulder complex. The curvature of the joint allows the Scapula to slide back and forth along the articular surface of the Clavicle, thus ensuring constant alignment between the glenoid cavity and the head of the Humerus [22]. Like what was found in the sternoclavicular joint, there is an intra-articular disc, composed of fibrocartilage, interposed between the two surfaces. This structure is approximately wedge-shaped, and its size depends on the individual under study [5,19].

4.3. Glenohumeral Joint

Often referred to as the shoulder joint, the glenohumeral joint (Figure 23), as its name suggests, provides the bony connection between the Scapula, at the level of the glenoid cavity, and the head of the Humerus [5,19]. It is a ball-and-socket synovial joint (enarthrosis), which means it has high mobility and, consequently, reduced inherent stability [2,5,19]. The Humerus head is considered to be the “ball”, and the glenoid cavity of the Scapula is the “socket” [32].

Figure 23.

Glenohumeral Joint location—Anterior View.

It is the shoulder complex joint responsible for the diversity of movements characteristic of the upper extremity of the human body, allowing the positioning of the arm in all planes of three-dimensional space [2,26]. It is, however, complemented by the inherent movements of the remaining joints in the shoulder joint complex, which allow for maximum ranges of arm elevation movements, thereby avoiding conflict between anatomical structures.

In order to enhance the static stability provided by bone morphology, there is a ring of fibrocartilage and fibrous tissue associated with the contour of the glenoid cavity, often called the glenoid labrum [5,19]. This is fixed to the contour of the glenoid cavity through its internal surface, and to the joint capsule through its external surface [2,27]. As with articular cartilage, the triangular cross-section of the ring is not constant, being thicker and wider in the anterior area compared to the posterior.

From a functional perspective, it is evident that the glenoid labrum enhances the depth of the glenoid cavity, thereby ensuring better fixation of the humeral head and greater stability of the glenohumeral joint, as it increases the contact area between the articular surfaces.

5. Parametrization, Positioning and Assembly

The methodology developed and applied in this work seeks to help the standardize of the CAD assembly of the shoulder complex. This standardized methodology can be applied to ensure that all types of studies, including numerical, multibody, biomechanical, and others, are comparable. Within this context, the comparison of these results eliminates the need for models based on images acquired and processed by computed tomography (CT scans), thereby avoiding the diversity of models that are typically used. Moreover, this procedure should yield identical assemblies, regardless of the CAD models used for the bone segments, as their spatial relationship in the initial position will always be the same.

The reference position of the assembly is defined, assuming that the upper limb hangs vertically along the body, vertically, so that the longitudinal axis of the Humerus coincides with the anatomical longitudinal axis. Again, instead of using different initial anatomical positions, which were dependent on the base model, this new approach will allow an exact and equal standard starting point for all studies to be developed.

The assembly sequence was defined, starting from the Coronal Plane, which is the centre of the human body, and ending at the lateral periphery. Therefore, the starting geometry bone is the Sternum, followed by the Clavicle, then the Scapula, and finally the Humerus. All the assembly mates are defined in relation to the previous geometry entities (planes or axes).

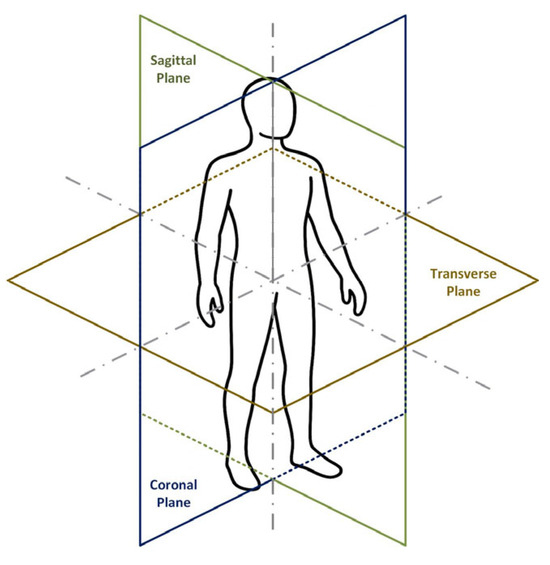

To ensure a better understanding, the three cardinal planes required in an anatomy study are presented in Figure 24.

Figure 24.

Anatomical Cardinal Planes.

Hence, the Sagittal, Coronal and Transverse planes were defined in the SolidWorks software, version 2025 SP5.0, shown in Figure 25, as well as the Longitudinal, Mediolateral and Anteroposterior axes, that result from the intersection of the previous planes intersection.

Figure 25.

SolidWorks® Anatomical Cardinal Planes (a) and Axes (b).

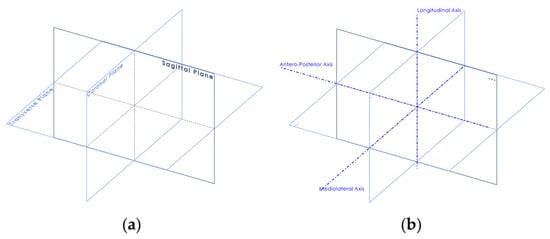

5.1. CAD Model of the Sternum

The Sternum configuration can be used as the initial/inertial or world reference for the complete assembly of the shoulder joint. It has its only and central axis of symmetry, the longitudinal axis, which is parallel to the Sagittal Plane of anatomical reference and coincides with the medial plane, which is the plane of vertical symmetry in the human body.

Therefore, its positioning is entirely coincident with the Sagittal Plane of the human body, meaning that its vertical symmetry plane will also coincide with the aforementioned plane already defined for assembly (Figure 26).

Figure 26.

Sagittal Plane and Mediolateral Axis in the Sternum: (a) Isometric View, (b) Front View.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the Sternum is not anatomically in a vertical position but rather rotated 65° relative to its Mediolateral Axis [21]. In this way, a new Transverse Plane (65° Transverse Plane) was defined, with a rotation angle of 65° in relation to the initial Transverse Plane, which serves as a reference for its correct positioning (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

Isometric View of the Initial (a) and Anatomical (b) position of the Sternum.

By defining these two references (Sagittal Plane, Mediolateral Axis and Transverse Plane rotated 65°), it is possible to correctly position the Sternum in the assembly.

The Sternum will be the reference position for the assembly, remaining fixed in this position.

5.2. CAD Model of the Clavicle

The Clavicle has as its primary reference the Sternum position, depending, on the previous parametrization. Moreover, being part of the sternoclavicular joint, along with the Sternum, it is intuitive to conclude that the sternal facet, present in the Clavicle, should be connected to the clavicular notch, present in the Sternum. However, to correctly position the Clavicle, other entities of this bone should be identified.

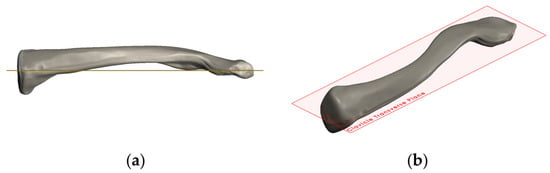

First, the Clavicle Axis must be defined. To do so, two points that will define the clavicular axis are marked in the Acromial and Sternal ends, more precisely, the Acromial and the Sternal Facets of the Clavicle, placed in anatomical position (Figure 28) [33]. This entity is fundamental for configuring the Clavicle Cardinal Planes in order to position it correctly relative to the Sternum.

Figure 28.

Clavicle Shaft or Axis (blue lines): Front View (a) and Top View (b).

As mentioned in chapter 2.2, the Clavicle is divided into three main segments: the Sternal End, the Clavicular Body, and the Acromial End. It also encompasses two main surfaces: the Superior Surface and the Inferior Surface. The Clavicle Transverse Plane divides these surfaces and serves as the primary reference plane for positioning the Clavicle horizontally (Figure 29). So, it is a horizontal plane that intersects the Clavicle Axis.

Figure 29.

Clavicle Transverse Plane (red entity): Front View (a) and Isometric View (b).

Despite some authors refer that the Clavicle anatomical position is not horizontal, i.e., it has an elevated position with an angle of approximately 4,5° with the anatomical Transverse Plane (Sung-min Ha et al. [34], McClure et al. [35]), and also considering the different anatomical position of Clavicle in male individuals (slightly elevated) and female individuals (horizontal) the anatomical position assumed for this approach, for simplification, is completely horizontal [33]. Consequently, the Clavicle Transverse Plane is parallel with the anatomical Transverse Plane. Once the assembly mates are related to the previous bone structure, in this case the Sternum, all the Clavicle assembly mates are parameterized in function of the Sternum. So, the Clavicle Transverse Plane is parallel with the Sternum Transverse Plane.

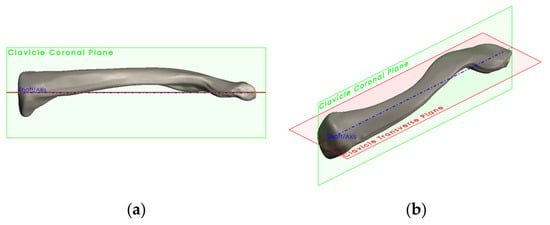

Next, the Clavicle Coronal Plane (Figure 30) is defined. It is a vertical plane that is perpendicular to the Clavicle Transverse Plane, and it should intersect the Clavicle Axis. This plane is fundamental to place the Clavicle in the assembly and to define the Clavicle retroversion relative to the anatomical Sagittal Plane and, in particular, to the Sternum Sagittal Plane.

Figure 30.

Clavicle Coronal Plane (green entity): Front View (a) and Isometric View (b).

To parameterize the last Cardinal Plane, the Clavicle Sagittal Plane, an auxiliary axis must be defined. This axis, the Clavicle Vertical Axis, is perpendicular to the Clavicle Axis and coplanar with the Clavicle Coronal Plane. Then, the Clavicle Sagittal Plane can be determined by the Clavicle Vertical Axis and the Clavicle Coronal Plane, which are, respectively, perpendicular and coincident (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Clavicle Sagittal Plane (vertical red entity): Front View (a) and Isometric View (b).

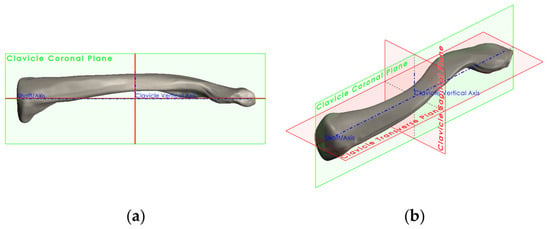

Furthermore, the Clavicle is rotated in relation to the anatomical Sagittal Plane by 30° and around the Longitudinal Axis [22]. Therefore, a Clavicle Sagittal Plane—30° is configured to assist this rotation mate (Figure 32).

Figure 32.

Clavicle Sagittal Plane—30 ° (green entity): Front View (a) and Top View (b).

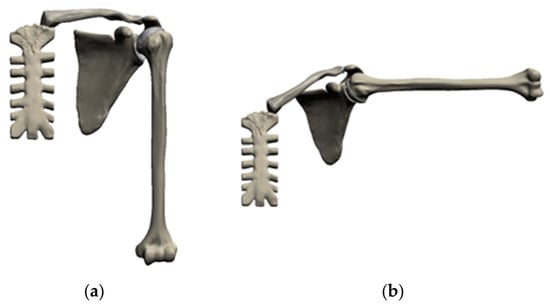

So, at this point, the assembly results are shown in Figure 33. The Sternum and the Clavicle form the sternoclavicular joint.

Figure 33.

Sternum and Clavicle in anatomical position forming the Sternoclavicular Joint: Front View (a), Top View (b) and Lateral View (c).

5.3. CAD Model of the Scapula

The Scapula plays an important role in the shoulder complex joint, not only because as it is part of three joints, being two of them principal joints, the glenohumeral joint, and the acromioclavicular joint and one functional joint, the scapulothoracic, but also because the mentioned glenohumeral joint is the main joint of the shoulder.

Once the bone structures are considered, despite the Sternum, are the Clavicle and the Humerus, only the acromioclavicular and the glenohumeral joints are taken into account for modelling.

The relation between the Scapula, the Clavicle, and the Humerus requires defining several entities for proper positioning

The Scapula has anatomical landmarks that serve as references to define important entities, such as the anatomical planes and axes.

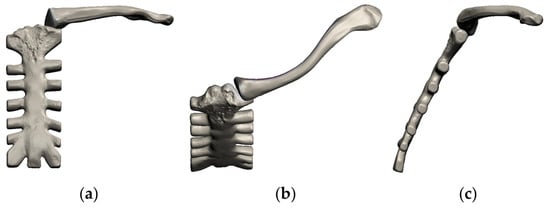

The first entity to be parameterized is the Scapula Mediolateral Axis, which is defined by two existing points. One is located at the geometric centre of the glenoid cavity area, and the other one is located at the trigonum spinae (Figure 34) [6,19,36,37].

Figure 34.

Scapula Mediolateral Axis: Front View (a), Top View (b) and Posterior View (c).

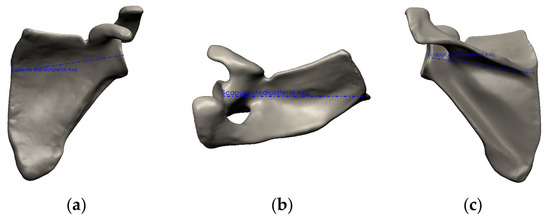

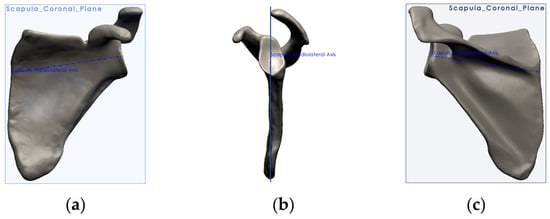

To configure the Scapula Coronal Plane, another important Scapula landmark is used: the angulus inferior. Then, based on the Scapula Mediolateral Axis, already defined, and the angulus inferior, the Scapula Coronal Plane is completely determined (Figure 35).

Figure 35.

Scapula Coronal Plane and Mediolateral Axis: Front View (a), Top View (b) and Posterior View (c).

The Scapula Coronal Plane together with the Clavicle Coronal Plane, can define the Scapula anatomical position in relation to the Clavicle which is retroverted with an angle of 60° [17,22,26,36,37].

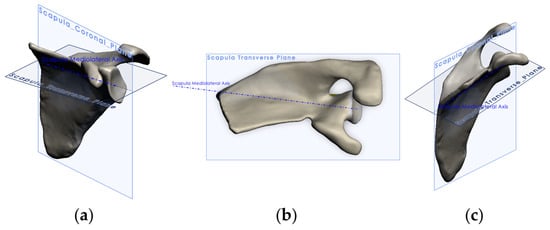

The Scapula Transverse Plane is configured with the two previously defined entities, the Scapula Coronal Plane and the Scapula Mediolateral Axis, being perpendicular to the first and coincident with the second (Figure 36).

Figure 36.

Scapula Transverse Plane: IsoLateral View (a), Top View (b) and IsoMedial View (c).

The Scapula Transverse Plane is required to level the Scapula in relation to the Clavicle and then constitute the acromioclavicular joint (Figure 37).

Figure 37.

Acromioclavicular Joint: Front View (a), Top View (b) and Lateral View (c).

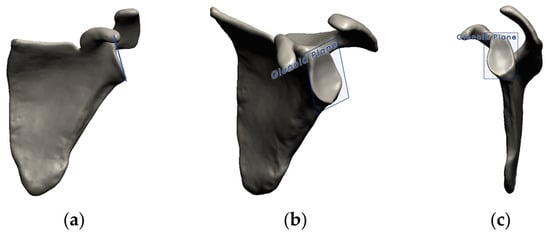

All the necessary entities to ensure the configuration of the acromioclavicular joint, which establishes the spatial relation between the Clavicle and Scapula are defined. Thus, there exists another fundamental entity in the Scapula bone, the glenoid cavity, which, together with the humeral head, present in the Humerus, constitutes the glenohumeral joint. To establish the assembly mates between the mentioned bone structures, the Scapula and Humerus, the Glenoid Plane must be defined.

The Glenoid Plane is defined as the best-fitting plane, which is based on all the plotted points of the glenoid cavity surface (Figure 38) [6,38].

Figure 38.

Glenoid Plane (blue entity): Front View (a), IsoLateral View (b) and Lateral View (c).

5.4. CAD Model of the Humerus

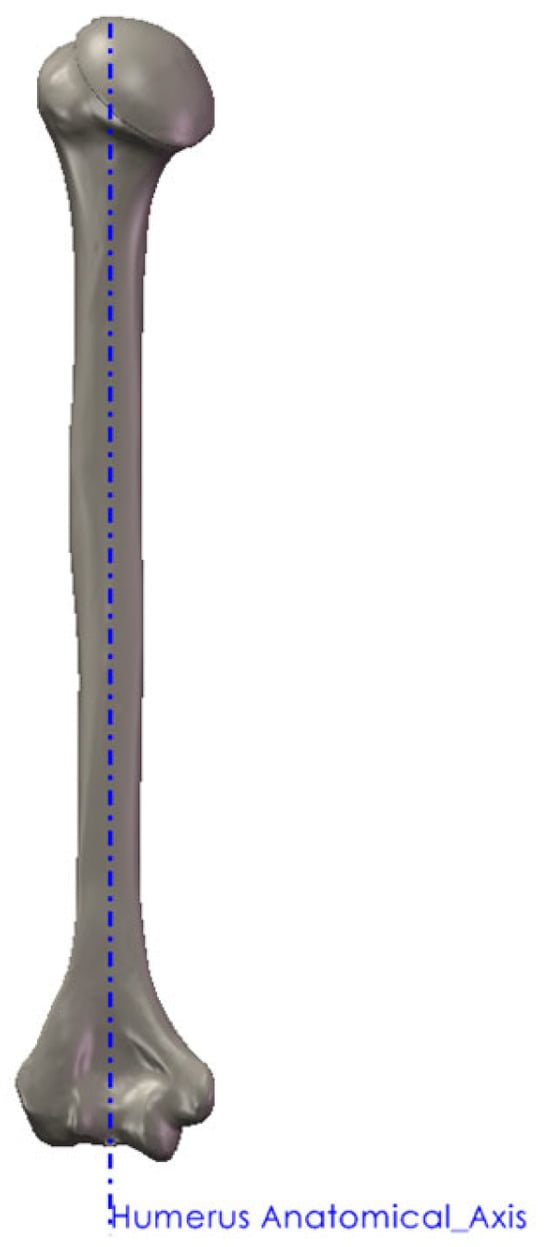

Similarly to the Scapula, the Humerus is a fundamental element in the shoulder joint because it is the other bone component of the glenohumeral joint, the most important and most studied joint of the shoulder complex. To complete the parameterization and assembly of the shoulder complex in its entirety, the Humerus is added. To correctly position it, it is necessary, once again, to identify and parameterize the fundamental entities required for this same positioning.

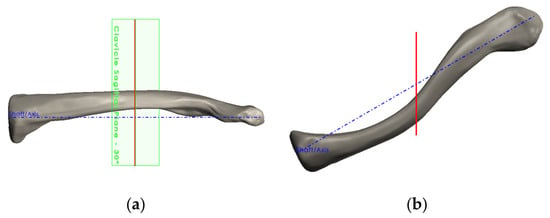

The reference entity to be initially defined is the Humerus Anatomical Axis, which defines an axis based on a cylindrical cavity that is part of the initial CAD (Figure 39).

Figure 39.

Front View of the Humerus Anatomical Axis (blue entity).

Nevertheless, the axis of the proximal Humerus can be obtained through serial midpoint determination on both projections (outer cortex) in a proximal segment defined by total bone length marks representing the line along the Humerus, passing through distal and proximal endosteal canals [24,26,27,28].

The Epicondylar Axis (ECA) is also designated as the line that connects the medial and lateral epicondyles.

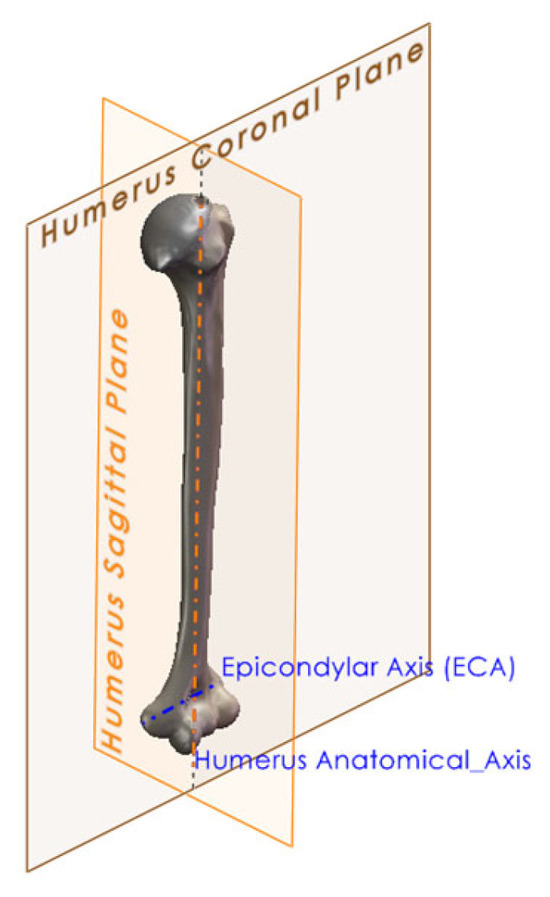

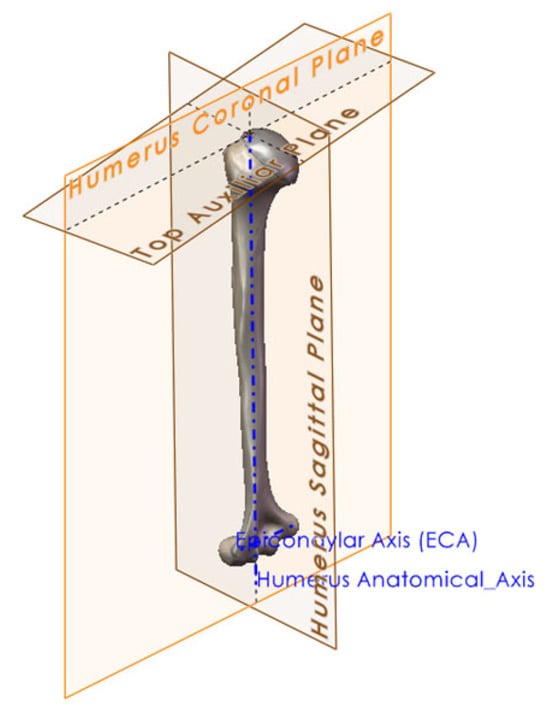

Then, to define the other anatomical planes, anatomical landmarks or references should be identified and used for this purpose. The first anatomical plane to be parametrized is the Humerus Coronal Plane which is based on the Epicondylar Axis (ECA), also designated as the line that connecting the medial and lateral epicondyles (Figure 40) [26] and the Humerus Anatomical Axis.

Figure 40.

Front View of the Humerus Coronal Plane (brown entity): Humerus Anatomical Axis and Epicondylar Axis (blue entities).

Based on the Humerus Anatomical Axis already defined, and based on the Humerus Coronal Plane, the Humerus Sagittal Plane is defined as being coincident and perpendicular to the mentioned Axis and Plane, respectively (Figure 41).

Figure 41.

Isometric View of the Humerus Sagittal and Coronal Planes (orange and brown entities) and, Humerus Anatomical Axis and Epicondylar Axis (blue entities).

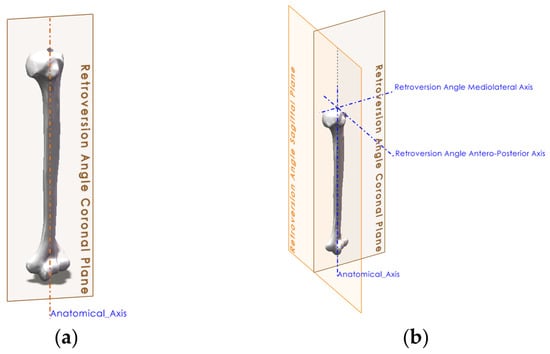

One of the main characteristics, already mentioned, is the retroversion, or declination, of the axis of the neck of the humeral head at 30° in relation to the Humerus Coronal Plane. Its definition is based on the initial reference of the Humerus Anatomical Axis and the Humerus Coronal Plane, thereby parameterizing the Retroversion Angle Coronal Plane (Figure 42a) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,39].

Figure 42.

Isometric View of the Retroversion Angle (brown entity) (a) and Retroversion Planes (orange entity) (b) in the Humerus.

Next, the Mediolateral Retroversion Angle Axis is defined based on the Top Auxiliary Plane and Coronal Retroversion Angle Plane. The Retroversion Angle Sagittal Plane is parameterized based on the Retroversion Angle Coronal Plane and the Top Auxiliary Plane (Figure 42b). Finally, regarding retroversion, the Retroversion Angle Antero-Posterior Axis was created, based on the previously defined plane, namely, the Retroversion Angle Sagittal Plane and the Top Auxiliary Plane (Figure 42b).

In addition to being perpendicular to the other two planes (Coronal and Sagittal) and the Humerus Anatomical Axis, the latter (Top Auxiliary Plane), was considered as tangent to the highest point of the humeral head (Figure 43).

Figure 43.

Isometric View of the Top Auxiliar Plane (horizontal brown entity).

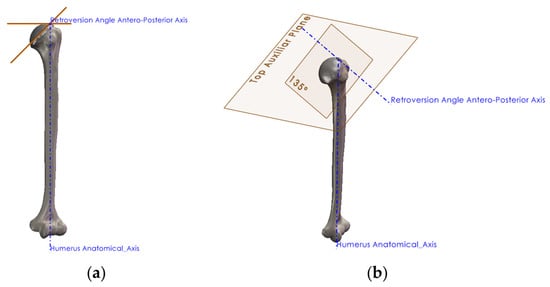

Another of the main characteristics of the Humerus is the inclination of its head, with an angle of 135°, relative to the anatomical axis, and which was parameterized considering the Retroversion Angle Sagittal Plane, with an inclination of 135° relative to this, and the Retroversion Angle Antero-Posterior Axis, thus defining the 135° plane (Figure 44) [21,22].

Figure 44.

Humerus Head Inclination Angle (brown entities): Anterior View (a) and Isometric View (b).

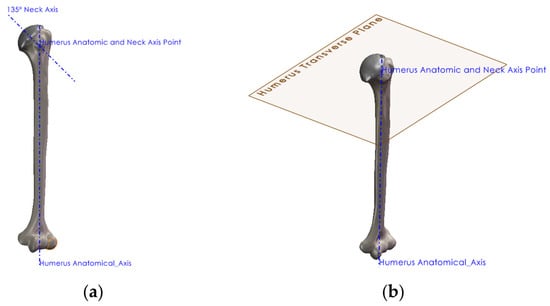

To define the Humerus Transverse Plane (Figure 45) both Coronal and Sagittal Humeral Planes were used, in addition to the Humerus Anatomic and Neck Axis Point (Figure 45a), which is a result of the intersection of the Humerus Anatomical Axis and 135° Neck Axis.

Figure 45.

Humerus Transverse Plane (brown entity): Humerus Anatomic and Neck Axis Point (a) and Isometric View (b).

The three defined planes will serve as a basis for parameterizing of the remaining geometric characteristics of the Humerus.

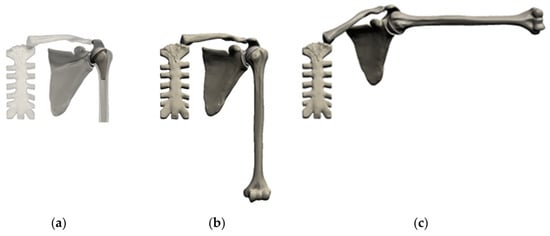

These are the main geometric characteristics that the Humerus presents, which is why their inclusion in the modelling parameters is mandatory as it is essential for its correct positioning in the final assembly (Figure 46).

Figure 46.

Shoulder Complete Assembly: Front View (a), Top View (b) and Medial View (c).

5.5. Applicability

Once the entire biomechanical shoulder model is assembled, it can be used for clinical or biomechanical applications.

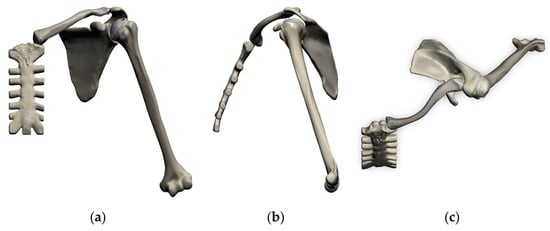

As an example, the model in Figure 47 shows the Humerus in 90° abduction with the corresponding change in position of the Clavicle and Scapula, which, due to the synergistic movement characteristic of this joint, also rise by 30° and 30°, respectively, in relation to the antero-posterior axis [17,20,34,35,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Figure 47.

Shoulder Positioning: Orthostatic (a) and 90° Abduction (b).

In addition to the abduction position, the model allows the parameterization of other important positions for joint analysis.

The model will also enable combining different positions with medical devices for the structural and biomechanical evaluation of these devices. Figure 48 illustrates this combination, with the shoulder in 90° abduction and a prosthesis applied.

Figure 48.

Shoulder with Prosthesis: Detail (a), Orthostatic (b) and 90° Abduction (c).

The proposed methodology can play an important role in the biomechanical and structural analysis of healthy joints, joints with established pathology, and medical de-vices or surgical techniques that are already in use or under development.

To emphasise the importance of using a standardised model like the one presented here, a shoulder joint model from the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) Visible Human Project (VHP) is used to demonstrate the natural anatomical differences be-tween shoulder joint models obtained from different human sources.

NLM provides a public-domain library of cross-sectional cryosection, CT, and MRI images obtained from one male cadaver and one female cadaver. From those im-ages, a 3D model of the male cadaver was obtained, enabling quantitative validation and reproducibility of our proposed model.

In the VHP model, all the principal relative positions were measured to compare with the developed model based on the literature and, finally, to demonstrate the re-producibility of the settled model, a parameterised model containing the VHP model’s principal relative positions of the bone segments was also added.

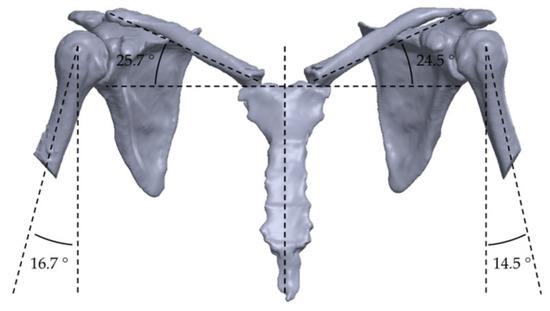

Nevertheless, this is only an example of the infinite models available for research purposes, and it is evident that all the model’s particularities are evident even when we compare the right and left sides of the model itself.

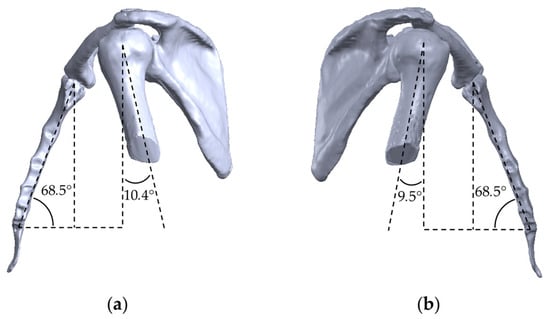

Regarding the results of the medical images model, the relative positions of the bony elements differ from the standard positions. The humerus and the clavicle position, as can be seen in Figure 49, in addition to showing differences between the left and right sides, are entirely random, as they depend on the anatomical characteristics of the base model and, simultaneously, on its position at the time the medical images were acquired.

Figure 49.

Front View of Clavicle and Humerus VHP Shoulder Angles Alignment (dotted lines).

From both side views, it is also possible to verify, as shown in Figure 50, that the sternum angle is higher than the 65° proposed in the literature [21], demonstrating that the model was probably based on an older person. From the Figure 50, it can be observed that the left- and right-side humerus positions differ, and the orthostatic position is, once again, random.

Figure 50.

Lateral View of Sternum and Humerus VHP Shoulder Angles Alignment (dotted lines): Left (a) and Right (b).

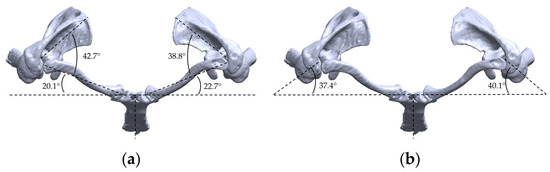

Finally, the top views (Figure 51) demonstrate that the relative positions of the clavicle, scapula, and humerus are very different from those proposed in the literature and that the symmetry, as presumed, does not exist.

Figure 51.

Top View of VHP Shoulder angles alignment (dotted lines): Clavicle and Scapula (a) and Humerus (b).

One of the principal advantages of the proposed methodology is its parameterisation, which enables it to represent any desired position. Therefore, the VHP model was reproduced to demonstrate this capability.

The previously determined angular positions of the sternum, clavicle, scapula, and humerus in the VHP model were used to parameterise the model, and the final result is shown in Figure 52.

Figure 52.

Shoulder parameterized in the VHP position: Front View (a), Lateral View (b) and Top View (c).

Another important gain of this approach is that it can eliminate the need to submit a patient to an MRI or CT scan, once its anatomical particularities can be reproduced with this model. With this advantage, the shoulder model assembly can be accelerated, as segmentation of medical images is a demanding, time-consuming task.

In conclusion, the use of different models with significant differences, due to anatomical particularities, MRI or CT scanning position, or even within the model itself between the left and right sides, can be avoided by adopting the proposed model.

6. Conclusions

The actual Finite Element Analysis, Biomechanical and Multibody research considers different shoulder joint models (CAD and CT scans), which most likely to have different geometric relations between bone segments, leading to different final results, even when considering the same scenario or case study.

Existing CAD shoulder models are typically based on geometries originating from CT scans, from MRI, which means that their anatomical position and even their geometry have particularities resulting from the position in which these medical images were obtained and the anatomy of each patient from whom the images are acquired, or even through databases such as the National Library of Medicine’s Visible Human Project®, or common software platforms, meaning that comparative models assume arbitrariness, which limits, for example, the comparison of results by biomechanics research teams.

Thus, their use in biomechanical studies will compromise the final results because the model used may have infinite initial positions and anatomical particularities, which may bias the final analysis.

This work aims to provide a methodology for parameterizing the model, thereby contributing to the resolution of this limitation. If the anatomical references for each bone are used, the final assembly will always have the same spatial relationship, regardless of its origin.

The methodology developed here can help to standardize or uniformize the assembly of the shoulder joint, not only for to the spatial relationship between the various bone segments that make up the shoulder joint, but also in consideration of the Sternum as the primary anatomical reference for this joint, since it is in this bone structure that all shoulder movement occurs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.; Methodology, V.M., L.R. and M.A.N.; Software, V.M.; Validation, M.A.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, V.M. and L.R.; Writing—review and editing, V.M., L.R., M.A.N. and P.C.; Supervision, M.A.N., L.R. and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is sponsored by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project 2021.06345.BD. This research is sponsored by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under projects UID/00285/2025, LA/P/0112/2020 and UIDB/00681.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van der Helm, F.C.; Veeger, H.E.; Pronk, G.M.; Van der Woude, L.H.; Rozendal, R.H. Geometry parameters for musculoskeletal modelling of the shoulder system. J. Biomech. 1992, 25, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, R.A.; Crowninshield, R.D.; Wittstock, C.E.; Pedersen, D.R.; Clark, C.R.; van Krieken, F.M. A model of lower extremity muscular anatomy. J. Biomech. Eng. 1982, 104, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracovetsky, S.; Farfan, H. The Optimum Spine. Spine 1986, 11, 543–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Lee, T.; Malito, L.; Martin, A.; Gunther, S.B.; Harmsen, S.; Norris, T.R.; Ries, M.; Van Citters, D.; Pruitt, L. Analysis of severely fractured glenoid components: Clinical consequences of biomechanics, design, and materials selection on implant performance. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2016, 25, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroder, P.; Akgün, D.; Plachel, F.; Baur, A.D.J.; Siegert, P. The influence of posture and scapulothoracic orientation on the choice of humeral component retrotorsion in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousigues, S.; Gajny, L.; Abihssira, S.; Heidsieck, C.; Ohl, X.; Hagemeister, N.; Skalli, W. 3D reconstruction of the scapula from biplanar X-rays for pose estimation and morphological analysis. Med. Eng. Phys. 2023, 120, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehqan, B.; Delkhoush, C.T.; Mirmohammadkhani, M.; Ehsani, F. Does forward head posture change subacromial space in active or passive arm elevation? J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2021, 29, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufeland, M.; Brusis, C.; Kubo, H.; Grassmann, J.; Latz, D.; Patzer, T. The acromiohumeral distance in the MRI should not be used as a decision criterion to assess subacromial space width in shoulders with an intact rotator cuff. Knee Surg. Sport Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 2085–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Takagishi, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Shitara, H.; Ichinose, T.; Takasawa, E.; Shimoyama, D.; Osawa, T. The impact of faulty posture on rotator cuff tears with and without symptoms. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2015, 24, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Fripp, J.; Chandra, S.S.; Neubert, A.; Xia, Y.; Strudwick, M.; Paproki, A.; Engstrom, C.; Crozier, S. Automatic bone segmentation and bone-cartilage interface extraction for the shoulder joint from magnetic resonance images. Phys. Med. Biol. 2015, 60, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohl, X.; Hagemeister, N.; Zhang, C.; Billuart, F.; Gagey, O.; Bureau, N.J.; Skalli, W. 3D scapular orientation on healthy and pathologic subjects using stereoradiographs during arm elevation. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2015, 24, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bola, M.; Simões, J.A.; Ramos, A. Finite element modelling and experimental validation of a total implanted shoulder joint. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 207, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffarzick, D.; Entacher, K.; Rafolt, D.; Schuller-Götzburg, P. Temporary Protective Shoulder Implants for Revision Surgery with Bone Glenoid Grafting. Materials 2022, 15, 6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bola, M.; Simões, J.; Ramos, A. Finite element analysis to predict short and medium-term performance of the anatomical Comprehensive® Total Shoulder System. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 219, 106751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, G.; Graichen, F.; Bender, A.; Rohlmann, A.; Halder, A.; Beier, A.; Westerhoff, P. In vivo glenohumeral joint loads during forward flexion and abduction. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B.A.; Pandy, M.G. Musculoskeletal Model of the Upper Limb Based on the Visible Human Male Dataset. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2001, 4, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culham, E.; Peat, M. Functional Anatomy of the Shoulder Complex. J. Orthop. Sport. Phys. Ther. 1993, 18, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Willems, P.Y. On the kinematic modelling and the parameter estimation of the human shoulder. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; van der Helm, F.C.T.; Veeger, H.E.J.; Makhsous, M.; van Roy, P.; Anglin, C.; Nagels, J.; Karduna, A.R.; McQuade, K.; Wang, X.; et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion—Part II: Shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, N.; Yamada, Y.; Oki, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Yokoyama, Y.; Yamada, M.; Nagura, T.; Jinzaki, M. Three-dimensional alignment changes of the shoulder girdle between the supine and standing positions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebzak, W.P.; Żurawski, A.Ł.; Kosztołowicz, M. Alignment of the Sternum and Sacrum as a Marker of Sitting Body Posture in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapandji, A.I. Fisiologia Articular, 5th ed; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cartucho, A.; Espergueira-Mendes, J. O Ombro, 1st ed.; Lidel—Edições Técnicas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alashkham, A.; Soames, R. The glenoid and humeral head in shoulder osteoarthritis: A comprehensive review. Clin. Anat. 2021, 34, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boileau, P.; Walch, G. The three-dimensional geometry of the proximal humerus. Implications for surgical technique and prosthetic design. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1997, 79, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadavkolan, A.S.M.; Jawhar, A. Glenohumeral joint morphometry with reference to anatomic shoulder arthroplasty. Curr. Orthop. Pr. 2018, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, R.; Knothe, U.; Ballmer, F.T. Geometry of the proximal humerus and implications for prosthetic design. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2002, 11, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, J.; Garret, J.; Boutsiadis, A.; Sautier, E.; Geais, L.; Bothorel, H.; Shoulder Friends Institute; Godenèche, A. Is global humeral head offset related to intramedullary canal width? A computer tomography morphometric study. J. Exp. Ortop. 2018, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A.J.; David, R. Biomechanics of the shoulder and elbow. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchia, H. A Retroversão da cabeça do úmero: Revisão da literatura e mensuração em 113 úmeros de cadáveres. Rev. Bras. De Ortop. 2006, 41, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, L.C.; Lucas, D.B. The function of the clavicle; its surgical significance. Ann. Surg. 1954, 140, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chang, L.R.; Anand, P.; Varacallo, M.A. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Glenohumeral Joint. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.D.; Hoyen, H.A.; Blauth, M.; Galm, A.; Schweizer, M.; Raas, C.; Jaeger, M.; Jiang, C.; Nijs, S.; Lambert, S. The variance of clavicular surface morphology is predictable: An analysis of dependent and independent metadata variables. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-M.; Kwon, O.-Y.; Weon, J.-H.; Kim, M.-H.; Kim, S.-J. Reliability and validity of goniometric and photographic measurements of clavicular tilt angle. Man. Ther. 2013, 18, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, P.W.; Michener, L.A.; Sennett, B.J.; Karduna, A.R. Direct 3-dimensional measurement of scapular kinematics during dynamic movements in vivo. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2001, 10, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, N.; Ogawa, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Oki, S.; Watanabe, A.; Ikegami, H.; Toy-ama, Y. Morphologic features of humeral head and glenoid version in the normal glenohumeral joint. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2014, 23, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamill, J.; Knutzen, K.M. Biomechanical Basis of Human Movement; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, L.F.; Verstraeten, T.; Speeckaert, W.; Karelse, A. Reliability of the glenoid plane. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2010, 19, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammishetti, V.; Dharanipragada, S.; Basu, D.; Ananthakrishnan, R.; Surendiran, D. A Prospective Study of the Clinical Profile, Outcome and Evaluation of D-dimer in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016, 10, OC07–OC10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sehrawat, J.S.; Pathak, R. Variability in anatomical features of human clavicle: Its forensic anthropological and clinical significance. Transl. Res. Anat. 2016, 3–4, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Lin, K.J.; Wei, H.W.; Tsai, C.L.; Lin, K.P.; Lee, P.Y. Morphometric Analysis of the Clavicles in Chinese Population. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, A.; Huysmans, T.; Van Glabbeek, F.; Sijbers, J.; Gielen, J.; Van Tongel, A. The anatomy of the clavicle: A three-dimensional cadaveric study. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsen, F.A.; Cordasco, F.A.; Sperling, J.W.; Lippitt, S.B. (Eds.) Rockwood and Matsen’s the Shoulder, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, P.; Cutti, A.G.; Filippi, M.V.; Cavazza, S.; Ferrari, A.; Cappello, A.; Davalli, A. Inter-operator reliability and prediction bands of a novel protocol to measure the coordinated movements of shoulder-girdle and humerus in clinical settings. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2009, 47, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).