Abstract

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) has developed from a rudimentary adjunct into a versatile modality that now plays a crucial role in neurosurgery. Offering real-time, radiation-free and repeatable imaging at the surgical site, it provides distinct advantages over intraoperative magnetic resonance (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) in terms of accessibility, workflow integration and cost. The clinical spectrum of IOUS is broad: in cranial surgery it enhances the extent of resection of gliomas and metastases, supports dissection in meningiomas and enables localization of MRI-negative pituitary adenomas; in spinal surgery, it guides resection of intradural and intramedullary tumors, assists in myelotomy planning and confirms decompression in degenerative conditions such as cervical myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. IOUS also offers unique insights into cerebrospinal fluid disorders, including arachnoid webs, cysts, syringomyelia and Chiari malformation, where it visualizes cord compression and CSF flow restoration. In trauma and oncological emergencies, it provides immediate confirmation of decompression, directly influencing surgical decisions. Recent innovations, including contrast-enhanced ultrasound, elastography, three-dimensional navigated systems and experimental integration with artificial intelligence and robotics, are extending its functional scope. Despite heterogeneity of evidence and operator dependence, IOUS is steadily transitioning from an adjunctive tool to a cornerstone of multimodal intraoperative imaging, bridging precision, accessibility and innovation in contemporary neurosurgical practice.

1. Introduction

Intraoperative imaging has reshaped modern neurosurgery by overcoming the intrinsic limitation of microscopic vision and tactile feedback. Despite advances in neuronavigation and operative microscopes, the ability to reliably determine the extent of lesion removal, to distinguish abnormal from normal tissue and to confirm adequate decompression remains restricted. Among available modalities, intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) has emerged as one of the most versatile and accessible tools, providing real-time anatomical and functional information directly at the operative site [1,2,3].

Historically, IOUS was introduced in the 1980s for visualizing intramedullary spinal cord lesions, syringomyelia and arachnoid cysts [4,5]. Early probes were hindered by low resolution and artifacts, yet even rudimentary images provided useful intraoperative guidance. Subsequent advances in probe design, image reconstruction and integration with neuronavigation systems addressed these shortcomings and expanded its clinical applications [5,6,7,8].

In neuro-oncology, achieving maximal safe resection is a primary objective, as the extent of resection correlates with survival, recurrence and functional outcomes. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indispensable but cannot compensate for intraoperative brain shift or tissue deformation [9]. Here, IOUS has proven especially valuable: systematic reviews and metanalyses confirm that it can detect residual tumors with high specificity and clinically useful sensitivity, thereby increasing the likelihood of gross total resection [10,11]. Compared with intraoperative MRI (iMRI) and intraoperative CT (iCT), IOUS typically allows minute-scale acquisitions and lower capital/logistical requirements [6,12,13]; however, these advantages can be offset by operator dependence, artifact susceptibility, restricted acoustic window and integration/consumable costs. Quantitatively, pooled estimates report residual tumor detection with sensitivity of ~0.75 and specificity of ~0.88 (AUC ~0.89) in glioma cohorts, while comparative series suggest complementary performance versus iMRI (e.g., higher IOUS sensitivity with lower specificity). Navigated 3D-IOUS has been shown to alter intraoperative decisions (prompting additional resection in a notable minority of cases) with strong agreement with postoperative MRI on residual volumes, and a single 3D sweep typically requires ~1–2 min, enabling repeated checks without major workflow penalties, whereas iMRI commonly adds tens of minutes depending on setup [14,15].

Applications extend to spinal surgery, where IOUS facilitates durotomy planning, guides myelotomy and enables real-time confirmation of resection completeness in intramedullary and extramedullary tumors [16,17]. In degenerative conditions such as ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and cervical spondylotic myelopathy, IOUS can assess decompression adequacy intraoperatively and may have prognostic value, with intraoperative hyperechogenicity correlating with postoperative outcomes [18].

Emerging innovations, including contrast-enhanced ultrasound, elastography, three-dimensional navigated IOUS and AI-assisted interpretation, show promise in addressing these limitations [8,19,20]. Although still under validation, these advances suggest a future in which IOUS combines accessibility with unprecedented precision, consolidating its role as a core intraoperative imaging modality in neurosurgery. Despite its versatility, IOUS has well-recognized constraints in routine neurosurgical use: image quality and interpretation are operator-dependent; artifacts from air, blood and hemostatic materials can mimic or obscure residual disease; bone/air interfaces restrict the acoustic window and field of view; sensitivity may drop for small or deep-seated lesions; and post-debulking cavity geometry can complicate margin assessment. Heterogeneity in acquisition presets and workflow further limits reproducibility and there is a steep learning curve compared with static imaging. These limitations are partially mitigated by navigated 3D acquisitions and MRI-US coregistration [20,21,22,23,24].

For AI-assisted IOUS (e.g., automated tissue classification, margin detection and registration), deployment must satisfy evolving medical AI regulations. In the European Union, the AI Act classifies clinical AI embedded in devices as high-risk, imposing risk management, data governance, human oversight and post-market monitoring with staged applicability through 2026–2027 [25]. In the United States, the FDA expects Predetermined Change Control Plans to govern iterative model updates within a total product lifecycle approach [26].

Against this backdrop, the present review aims to provide a comprehensive and critical synthesis of the role of IOUS in neurosurgery. Specifically, it will (i) examine evidence supporting its use in cranial and spinal procedures; (ii) compare its strengths and limitations with alternative intraoperative imaging modalities; (iii) identify current gaps in knowledge, in particular with regard to standardization, training and long-term outcomes; and (iv) explore future perspectives, including functional US applications, multimodal integration and the transformative potential of artificial intelligence and robotic systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conceived as a narrative synthesis of the literature on IOUS in neurosurgery, with the goal of integrating technical, clinical and practical perspectives. A structured search of the literature was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 1982 and September 2025. The following search terms and combinations were used: (“intraoperative ultrasound” OR “IOUS”) AND (“neurosurgery” OR “brain tumor” OR “glioma” OR “spine” OR “meningioma” OR “Chiari” OR “myelopathy” OR “intramedullary tumor”). Original studies, reviews and technical notes describing the application, accuracy and clinical impact of IOPUS in cranial or spinal surgery were included. Case reports were included only when they provided unique technical insights. Articles not in English or unrelated to human neurosurgery were excluded.

3. Historical Context and Technological Evolution

The adoption of IOUS in neurosurgery dates back to the late 1970s and early 1980s. initial reports by Dohrmann and Rubin [4,5], and later Jokich et al. [6], demonstrated its feasibility in visualizing syringomyelia, arachnoid cysts and intramedullary spinal cord tumors [4,5,6]. At that time, images were rudimentary, with low resolution and significant artifacts, yet they provided crucial intraoperative feedback not otherwise attainable. These studies proved that real-time imaging could extend the surgeon’s perception beyond the microscope and tactile exploration, offering a dynamic and functional assessment of neural structures [4,5,6]. Technological advances subsequently reshaped the field. High-frequency transducers improved resolution, advanced beamforming algorithms reduced artifacts and volumetric imaging allowed reconstruction of complex geometries. The integration of US in neuronavigational workflows was transformative, mitigating registration errors due to intraoperative brain shift [1,7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evolution and applications of iOUS in neurosurgery. Timeline illustrating the progressive adoption of IOUS from its introduction in the 1980s for intramedullary lesions and CSF pathologies, to contemporary applications in brain and spine oncology and degenerative and traumatic conditions and the integration of advanced modalities such as 3D navigation, CEUS, elastography, AI and robotics.

Unlike intraoperative MRI (iMRI) or computed tomography (iCT), which require costly infrastructure and prolong operative time, IOUS emerged as a rapid, radiation-free and repeatable modality. Nevertheless, practical constraints can limit sustained adoption in resource-limited settings, such as procurement and maintenance of US machines and probes, availability and cost of sterile probe covers (and, when used, CEUS agents), reliable service/sterilization and power and constrained training and reimbursement pathways, which also affect reproducibility across teams [27]. Beyond these logistical aspects, IOUS has intrinsic imaging limitations; its lower soft tissue contrast resolution compared with MRI can make a subtle differentiation between tumor, edema and normal parenchyma more challenging; depth penetration and field of view are restricted by bone and air interfaces; and acoustic shadowing or reverberation artifacts may obscure deep margins [27,28]. Interpretation challenges further arise from IOUS’s lower soft tissue contrast relative to MRI, restricted acoustic windows near bone/air and susceptibility to artifacts from air, blood and hemostatic materials; together with platform/preset variability and non-uniform techniques (e.g., saline fill and pressure control), these factors can reduce sensitivity for small or deep-seated remnants and hinder external validation [28]. That said, case studies from low- and middle-income settings document the feasibility and workflow impact of IOUS when paired with basic training, checklists and systematic archiving/QA, supporting its role as an accessible adjunct while acknowledging the above constraints [29,30]. Its affordability and portability position it as a democratizing force in intraoperative imaging, with applications not only in high-resource academic centers but also in low- and middle-income countries where iMRI is not feasible [1,7] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative table: IOUS vs. iMRI vs. iCT vs. fluorescence/IONM.

4. Brain Tumor Surgery: Scope, Innovation and Clinical Outcomes

The application of IOUS in brain tumor surgery has evolved from a supplementary imaging modality into an integral component of contemporary neuro-oncology practice. Among its most studied indications are gliomas, in which maximizing the extent of resection (EOR) directly influences patient survival, recurrence and functional outcomes. Static preoperative MRI, although invaluable for planning, cannot compensate for intraoperative anatomical changes, including brain shift, tissue swelling and cavity deformation [1,9,10,11]. Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that iOUS reliably detects residual tumor with high specificity and clinically meaningful sensitivity, findings that align closely with postoperative MRI [31,32,33]. Larger multicenter series have further confirmed that navigated IOUS enhances resection control and has been associated with improved survival metrics in some cohorts; however, the available evidence is predominantly retrospective and heterogeneous, so causal inference is not warranted [34].

The versatility of IOUS is underscored by its adaptability to a range of tumor types. In gliomas, conventional B-mode remains the cornerstone for intraoperative margin assessment, but advanced modalities such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and elastography are progressively redefining its potential [21,31]. CEUS allows the surgeon to appreciate vascular heterogeneity within tumors, enhancing delineation of residual tissue, especially in high-grade gliomas [34,35,36]. Elastography, on the other hand, quantifies tissue stiffness, offering a biomechanical contrast between infiltrating tumors, edematous brain and necrotic tissue [37,38]. Navigated three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound further integrates volumetric data with preoperative MRI, enabling quantitative correction for brain shift and dynamic reoptimization of the surgical plan [39,40].

Beyond gliomas, IOUS has proven its worth in other cranial neoplasms. In metastatic brain tumors, intraoperative imaging with US significantly increases gross total resection (GTR) rates, a factor of particular importance in patients with large or multiple lesions [41,42]. Similarly, CEUS has been employed in meningiomas to visualize tumor vascularization, improve dissection planes and anticipate intraoperative bleeding risks [43]. Pediatric neuro-oncology represents another domain in which IOUS is particularly useful. In children, where small craniotomies, deep-seated lesions and the need to minimize resection-related morbidity pose unique challenges, navigated IOUS shows high diagnostic performance for residual detection (e.g., sensitivity 100% and specificity 84.6%) and strong agreement with iMRI for volume assessment and spatial accuracy [7]. Series focused on pediatric brain tumors also reported very high concordance with postoperative MRI in determining EOR (e.g., NPV 98% and PPV 100% for GTR/subtotal calls) [44]. Moreover, the largest pediatric series to date from a tertiary children’s center confirms high sensitivity/specificity of IOUS in predicting residual disease and highlights its value for intraoperative decision-making [45]. Multicenter experience in pediatric low-grade glioma further supports the complementary roles of IOUS and iMRI in maximizing safe resection. Vascular lesions such as cavernomas and hemangioblastomas also benefit from IOUS, as it allows intraoperative identification of lesion margins and feeding vessels. Furthermore, reports describe its utility in guiding aspiration of abscesses, offering immediate feedback on cavity decompression [46,47,48].

5. Pituitary and Sellar Pathology

Surgery in the sellar and parasellar region is inherently challenging because of the small dimensions of the pituitary gland, the frequent presence of microlesions and the close relationship with the cavernous carotids and optic chiasm. This is evident in Cushing disease, where corticotroph microadenomas are often <5 mm and remain undetectable even on dedicated MRI sequences [49]. IOUS has therefore gained attention as a complementary imaging modality capable of revealing adenomas that are radiologically occult. Various reports have shown that IOUS through the trans-sphenoidal corridor can delineate hypoechoic adenomatous tissue guiding selective adenomectomy and may be associated with higher biochemical remission rates in selected series [50,51]. In a comparative series of 138 trans-sphenoidal surgeries, the use of IOUS was associated with higher GTR (79% vs. 44%; p = 0.0008), shorter operative time (74 vs. 146 min; p < 0.0001), lower estimated blood loss (119 vs. 284 mL; p < 0.0001) and reduced length of stay (2.9 vs. 4.2 days; p = 0.001); overall complication rates were not increased (numerically lower, without statistical significance) [51]. These data support the safety of IOUS-assisted trans-sphenoidal surgery while underscoring that the evidence remains observational [52,53]. Given the observational nature and variability of criteria across studies, these findings should be interpreted cautiously and not as proof of causality [50,51]. Moreover, IOUS provides real-time confirmation of tumor removal and helps distinguish residual adenoma from normal pituitary, avoiding unnecessary exploration. Doppler-enabled US adds another layer of safety, enabling mapping of sellar and parasellar vessels, in particular being valuable in reoperations or invasive macroadenomas where surgical planes are obscured [54]. Beyond adenomas, IOUS has also been explored in cystic sellar lesions (e.g., Rathke’s cleft cysts and craniopharyngiomas), where it supports cyst aspiration and assessment of residual cavity [55].

6. Spinal Pathology: Tumors, Degenerative Disorders and Deformity

IOUS has long been established as a reliable adjunct in spinal surgery, with applications spanning intradural tumors, intramedullary lesions, degenerative disorders and deformity correction. In intradural–extramedullary tumors, such as meningiomas and schwannomas, IOUS allows surgeons to localize the lesion before durotomy, refine the dural opening and confirm adequate decompression following resection [56,57]. Particularly illustrative are “mobile” schwannomas, which can migrate within the dural sac and present at different levels intraoperatively compared to preoperative MRI. In such cases, IOUS is indispensable for accurate localization and complete exposure, preventing unnecessary durotomy or incomplete resection [57]. In intramedullary tumors, including ependymomas, astrocytomas, gangliogliomas and hemangioblastomas, the role of IOUS is equally significant. US enables the delineation of the cord–tumor interface, facilitates the choice of a safe myelotomy corridor and assists in identifying cleavage planes between pathological and normal tissue [58]. IOUS defined tumor margins and reduced the risk of neurological deficits following resection of intramedullary ependymomas [59,60]. More recent developments, such as navigated three-dimensional (3D) IOUS, have expanded these capabilities, offering real-time volumetric guidance that reduces navigation error and increases surgical confidence [61]. This technology has also proven effective in the management of intramedullary vascular lesions, such as hemangioblastomas and dural arteriovenous fistulas, where intraoperative mapping of feeding vessels is critical for safe dissection and complete obliteration [62]. Beyond oncological indications, IOUS is gaining relevance in degenerative and deformity surgery. In degenerative cervical myelopathy, IOUS markers provide measurable prognostic information. In a prospective cohort, the mean 12-month modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association score recovery rate was 68.6 ± 20.3% overall; patients with adequate sonographic cord re-expansion after decompression achieved 76.2 ± 16.2% versus 59.2 ± 21.7% in those with inadequate re-expansion (p = 0.028). Hyperechogenicity was more frequent in the latter group, indicating that real-time IOUS expansion correlates with better neurological recovery [63]. Complementarily, intraoperative cord hyperechogenicty intensity (gray-value ratio) showed a negative correlation in 12-month recovery (ρ = −0.582, p = 0.0049) and sensory (ρ = −0.452, p = 0.035) subscores, reinforcing its prognostic value; mean recovery in that series was 65 ± 20.3% [64]. Contrast-enhanced IOUS perfusion offers complementary insight: in a prospective study (n = 26), the overall recovery rate was 50.7 ± 33.3%; peak intensity (PI) was higher in compressed vs. normal cord (24.58 ± 3.19 vs. 22.43 ± 2.39; p = 0.019); and both ΔPI and ΔAUC correlated negatively with recovery (r = 0.463, p = 0.030; r = −0.466, p = 0.029), with worse outcomes in hyperechoic cords (p = 0.016) [65]. For intramedullary spinal cord tumors, IOUS guidance enhances resection control and functional outcomes. In a contemporary single-institution series of 43 patients, IOUS confirmed lesion extent and location before dural opening in 97.7%, detected residual or hidden lesions in 7%, verified absence of hematoma in 53.5% and avoided additional durotomies in 7%; GTR was achieved in 93%, supporting both oncologic and neurological benefits [66]. For ossification of the OPLL, IOUS has been employed both in anterior and posterior decompression, confirming the adequacy of spinal canal enlargement and reducing the risk of under-decompression [18]. Similarly, in technically demanding procedures such as oblique corpectomy, IOUS offers additional safety by identifying the course of the vertebral artery and assessing the adequacy of ventral decompression, minimizing the likelihood of vascular complications [49]. In laminoplasty, the modality provides dynamic intraoperative confirmation of canal expansion and restoration of spinal cord pulsatility, which has been reported to correlate with postoperative neurological improvement in observational series [50,67]. These correlations do not establish causality. Finally, in the domain of complex spinal deformity surgery, IOUS has proven to be highly adaptable. During pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO), real-time sonographic assessment of spinal cord morphology before and after correction mitigates the risk of acute neurological deterioration, as reported by Chryssikos [68]. In scoliosis correction, IOUS has been successfully used to assess spinal canal dimensions intraoperatively and to monitor dynamic changes in cord alignment, offering an additional safeguard beyond neurophysiological monitoring. Taken together, these applications confirm that IOUS is not limited to tumor surgery but has evolved into a multipurpose modality, capable of guiding diverse spinal interventions with direct implications for both surgical precision and patient safety.

7. Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics and Arachnoid Pathologies

One of the most distinctive contributions of IOUS lies in the assessment of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics and arachnoid pathologies, a domain in which conventional MRI often underperforms due to limitations in resolution and inability to capture real-time CSF flow. Lesions such as arachnoid webs and cysts frequently evade preoperative imaging, yet IOUS offers direct, dynamic visualization of these abnormalities and their effects on spinal cord morphology. Castillo et al. [69] demonstrated that IOUS could confirm the presence of dorsal arachnoid webs and provide real-time evidence of restored CSF pulsatility after surgical fenestration, thus serving as both a diagnostic and monitoring tool during surgery [69]. Similarly, Takahata et al. [70] reported the identification of pulsating arachnoid cysts as hidden etiologies of progressive thoracic myelopathy, visualized intraoperatively by IOUS when preoperative MRI was inconclusive [70]. The role of IOUS in syringomyelia is well established and historically among the earliest spinal applications of this modality. Dohrmann and Rubin [4,5] first reported in the 1980s the ability of IOUS to delineate syrinx cavities and to monitor their collapse following decompression [4,5]. Subsequent studies have confirmed that IOUS remains a reliable intraoperative method for guiding syrinx fenestration or syringo-subarachnoid shunting, offering the surgeon dynamic feedback on cavity decompression and CSF flow restoration [5]. In Chiari I malformation, IOUS has been increasingly employed to evaluate intraoperative adequacy of decompression. By combining B-mode imaging with Doppler, surgeons can directly assess CSF flow across the foramen magnum before and after bony decompression or duraplasty [71,72]. Fan et al. [73] showed that IOUS effectively differentiates patients who require only suboccipital craniectomy form those in whom duraplasty or arachnoid lysis is warranted, thereby optimizing the surgical strategy and reducing the risks of under- or overtreatment [73]. However, some authors have cautioned that intraoperative flow measurements may be influenced by patient positioning and anesthetic conditions, highlighting the importance of correlating IOUS findings with preoperative cine-MRIO studies [74,75,76,77]. Furthermore, IOUS has proven useful in inflammatory arachnoidopathies, such as arachnoiditis following epidural anesthesia or prior to surgery. Sklar et al. [78] described how IOUS delineated adhesive arachnoid changes and confirmed cord tethering, findings that were not readily apparent on MRI [78]. In such cases, iOUS contributes both to diagnosis and to guiding targeted lysis of adhesions, with reports describing postoperative functional improvement; nonetheless, attribution of benefit directly to IOUS guidance is not demonstrable given the study designs. Taken together, these applications underscore the unique functional value of IOUS in disorders of CSF circulation and arachnoid pathology. Formal learning curve data specific to CSF and arachnoid pathology are sparse, but technical series and feasibility studies indicate that proficiency depends on the following: (1) differentiating membranes/webs from flow artifacts related to respiration, cardiac pulsatility, probe pressure and positioning; (2) routine use of cine color–Doppler loops to confirm restoration of CSF pulsatility after each surgical step; and (3) correlation with postoperative MRI/cine-MRI to calibrate interpretation [72,73]. In practice, early experience of ~10–15 supervised cases (Chiari I, arachnoid webs/cysts, syrinx) combined with systematic video review and standardized acquisition (stable insonation angle, minimal probe pressure, coordination with ventilation holds) appears to flatten the learning curve and reduce false positives from reverberation or shadowing [79]. These points are supported by the IOUS series in Chiari I (monitoring CSF flow across the foramen magnum and guiding duraplasty decisions), arachnoid web/cysts (localization and confirmation of decompression) and syringomyelia (guiding fenestration/shunt placement) [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. By providing real-time confirmation of lesion presence, cord compression and restoration of CSF flow after intervention, IOUS fills a critical gap left by static imaging modalities.

8. Trauma, Infection and Urgent Scenarios

The value of IOUS becomes particularly evident in urgent and emergent neurosurgical scenarios, where timely and accurate intraoperative decision-making is critical and advanced modalities such as iMRI are rarely feasible. In acute cervical spinal cord injury (SCI), early and adequate decompression is one of the most important predictors of neurological recovery. Real-time IOUS offers immediate verification of decompression adequacy, providing dynamic visualization of residual cord compression and subarachnoid space re-expansion. Chryssikos et al. [76] demonstrated that IOUS correlated strongly with postoperative MRI and CT myelography, and in several cases directly influenced intraoperative decision-making by prompting surgeons to extend decompression before closure [76]. This real-time feedback may improve the adequacy of decompression, but evidence from randomized studies is lacking. In metastatic spinal cord compression, where “separation surgery” aims to achieve circumferential decompression of the cord and create a safe margin for subsequent stereotactic radiosurgery, IOUS has proven particularly useful. Ramirez Ferrer et al. [77] showed that IOUS confirmed ventral clearance and cord re-expansion, ensuring that decompression goals were achieved without the morbidity of excessive bony resection [77]. The ability to visualize real-time cord dynamics intraoperatively reduces reliance on postoperative imaging and increases confidence in surgical adequacy, which may translate into more effective combined surgery–radiotherapy workflows; however, causal effects on oncological outcomes have not been established. The utility of IOUS extends to infectious pathologies of the spine. In pediatric cases of spinal epidural abscess and spondylodiscitis, IOUS has been used intraoperatively to confirm adequate evacuation of purulent material and decompression of the neural elements [79]. Given the frequent urgency of such cases, and the challenge of obtaining iMRI in acutely ill children, IOUS provides a safe, rapid and repeatable imaging option. Similarly, in adult epidural abscesses, IOUS may assist in delineating the extension of the collection and ensuring thorough decompression. In trauma-related pathologies beyond SCI, IOUS has been applied to cases involving retropulsed bone fragments, burst fractures and spinal epidural hematomas. Here, IOUS provides real-time reassurance that the canal has been adequately decompressed after laminectomy or corpectomy. Reports highlight its value in confirming ventral decompression when direct visualization is limited by residual vertebral body or posterior longitudinal ligament [80,81]. In emergency surgery, several factors can compromise IOUS image quality and interpretation. Hemodynamic instability and low perfusion pressure may reduce echogenic contrast between neural and surrounding tissues, particularly in acute spinal cord injury or infection, where edema and congestion obscure normal interfaces. Limited acoustic windows due to bone fragments, dural hematoma or constrained exposures restrict insonation angles and depth penetration [77,78]. The presence of blood, air or debris within the operative field introduces reverberation artifacts that can mimic residual compression, while continuous suction or irrigation during decompression can degrade resolution. Patient positioning and ventilatory motion further influence Doppler or dynamic assessments. To mitigate these challenges, optimized techniques include the following: (1) maintaining a stable acoustic window with warmed, de-gassed saline and minimal probe pressure; (2) using low to moderate gain and tissue harmonic imaging to enhance contrast; (3) performing repeat sweeps after hemostasis and irrigation to clear artifacts; and (4) integrating IOUS findings with clinical and neurophysiological monitoring when signal quality is suboptimal [76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Although IOUS remains feasible under urgent conditions, these constraints underscore the need for operator experience and structured training in emergency workflows. Moreover, the ability to rapidly repeat the examination after corrective maneuvers or hemostasis allows the surgeon to adapt the procedure without delay (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neurosurgical spectrum of IOUS in brain and spinal surgery.

9. Minimally Invasive and Endoscopic Applications

The progressive miniaturization of surgical approaches has reshaped both spinal and cranial neurosurgery, emphasizing the need for intraoperative imaging modalities that can provide precise guidance without increasing procedural morbidity. In this context, IOUS has emerged as a particularly attractive adjunct, offering portability, repeatability and real-time feedback within narrow operative corridors [28,82]. Compared with iMRI or iCT, IOUS reduces logistical demands and eliminates radiation exposure while maintaining the ability to confirm key anatomical landmarks. Its extension into minimally invasive and endoscopic surgery reflects a natural evolution of these advantages. Applications in full-endoscopic spinal surgery demonstrate feasibility for level localization, endoscope docking and decompression confirmation, thereby significantly decreasing dependence on fluoroscopy [83]. Similarly, in extradural decompression for lumbar stenosis and disc herniation, IOUS has shown strong concordance with postoperative MRI in evaluating adequacy, providing the opportunity to detect residual compression intraoperatively [84]. In cranial neuroendoscopy, IOUS introduced through the working sheath allows for more accurate ventricular access, facilitates colloid cyst resection and supports intraventricular tumor biopsies, in particular in patients with distorted ventricular anatomy [85,86,87]. Collectively, these developments highlight the growing relevance of iOUS as a complementary modality that enhances safety and precision in minimally invasive neurosurgical paradigms.

10. Practical IOUS Techniques: Pearls, Pitfalls and Checklists

Effective IOUS hinges on appropriate probe selection, proactive artifact control and timing of acquisitions. For cranial work, a micro-convex 3–8 MHz transducer (global activity mapping, deeper planes) paired with a linear 7–12 MHz probe (cortical margins and superficial residuals) covers most needs; in narrow corridors or pediatrics, a “hockey-stick” 10–15 MHz probe offers excellent near-field resolution and maneuverability. In spinal cases, a linear 7–15 MHz probe through the dural window is preferred for defining the cord–tumor interface and polar vessels; when access is constrained or a deeper field is required, a micro-convex 5–8 MHz is useful. Initial presets should emphasize an adequate depth (then narrowed), focal zone at the structure of interest (or 5–10 mm deeper), dynamic range of ~60–80 dB and tissue harmonics when available, while respecting the ALARA (lowest output consistent with diagnostic quality) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Doppler and, where applicable, CEUS can complement vascular mapping. The saline-fill technique is central in cranial resections: use warm, de-gassed saline (~37 °C); overfill the cavity slightly and “burp” slowly to evacuate microbubbles. Keep the transducer fully submerged with minimal pressure to maintain a continuous fluid column; avoid air trapping under cavity edges or bridging veins. Hemostatic agents should be removed or temporarily displaced before the final sweep, as they can appear as hyperechoic mats with posterior shadowing and mimic residual tumors. Never use gel intracavitarily. Common artifacts have recognizable patterns and straightforward remedies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Air/reverberation/comet tail produce shimmering hyperechoic lines and dropout, and should be treated with irrigation using de-gassed saline, a slight probe tilt and refilling corners. Blood/clot/turbulence yield diffuse echogenicity or flicker, and should be treated using gentle suction and irrigation, pausing a few seconds for flow to settle and reducing overall gain. Bone edges/kerfs cause acoustic shadowing, and should be treated by changing the acoustic window or angle [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. After duraplasty or patch placement, expect interface echoes and acquire references images before closure to aid interpretation. Sweep timing should be protocolized. For gliomas, obtain (1) a baseline sweep after dural opening to establish orientation and the brain shift baseline; (2) a mid-resection sweep at ~50–70% estimated EOR to redirect the trajectory; and (3) a final sweep after hemostasis and saline refill, before definitive hemostatic placement/closure. For intramedullary tumors, (1) pre-myelotomy scanning identifies the safe corridor (median sulcus vs. dorsal root entry zone (DREZ)) and polar/feeding vessels; (2) after internal debulking, reassess the tumor–cord plane and search for satellite nodules; and (3) before dural closure, confirm cord re-expansion and pulsatility. For Chiari/CSF disorders, (1) obtain a baseline assessment of qualitative CSF flow and tonsillar impaction; (2) reassess after bony decompression to decide on duraplasty/arachnoid lysis; and (3) confirm restoration of CSF pulsatility after duraplasty/lysis. If turbulence or microbubbles persist, it is prudent to wait 2–3 min and repeat the acquisition (Table 3) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82].

Table 3.

Stepwise guide to setup, baseline sweep, intraoperative checkpoints, final verification and common artifacts/pitfalls with fixes. Parameters are starting points and should be adapted to anatomy and device, following ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable); perform the final sweep after hemostasis with warm, de-gassed saline and before definitive hemostatic placement. DREZ: dorsal root entry zone; EOR: extent of resection; ALARA: As Low As Reasonably Achievable.

Typical post-debulking pitfalls include cavity collapse with hidden recesses (mitigate with 360° probe rotation and deliberate oblique sweeps), re-introduction of air due to saline egress (maintain slight overfill and low, peripheral suction) and hemostatic agent mimicry (scan before placement or temporarily remove and re-scan). Reoptimize gain and focus whenever the effective imaging depth changes. When navigation diverges due to brain shift, perform 3D ultrasound sweep (if available) to update the dataset, or when that threat is absent, use IOUS as the real-time reference for margin assessment. To address the learning curve, a pragmatic training pathway can be anchored to the structure and outcomes of the international IOUS course [88], which has been delivered 21 times across 12 countries in a 1–2-day format combining approximatively 4 h of didactics with ~4 h of supervised hands-on (4–7 scanners; ≤5 learners per device) and smartphone-based Neurostream simulation on patient-specific 3D IOUS datasets coregistered to preoperative MRI. In four recent editions (Cape Town 12/2023; Edinburgh 01/2024; Barcelona 04/2024), matched pre/post-surveys (n = 67; 100% response) demonstrated significant improvements: median familiarity increased from 4 (IQR 2–6) to 8 (7–8); comfort rose for machine functionality from 4 (2–5.5) to 7.5 (6–8.5), probe selection from 4 (2–6) to 8 (6.5–9), image acquisition from 4 (3–6) to 7.5 (7–8.5) and interpretation from 4 (3–6) to 7.5 (7–8.5) (all p < 0.0001). Procedure-specific comfort also improved for ventricular catheter insertion from 3 (1.5–5) to 7 (6.5–8), endoscopic procedures from 2.5 (1.5–4) to 7 (5–8), tumor resection from 3.5 (2–5.5) to 7 (6–9) and Chiari I decompression from 2 (1.5–4) to 5.5 (4–7) (all p < 0.0001); the likelihood of future IOUS use rose to a median of 9/10 [88]. In stratified analyses, post-course scores favored qualified neurosurgeons for probe selection (p = 0.03), ventricular catheter insertion (p = 0.02) and endoscopic procedures (p = 0.029). Reported limitations include self-selected cohort and simulators emphasizing B-mode with limited Doppler/CEUS/elastography integration, underscoring the need to assess knowledge retention and real-world adoption after training [88].

11. Discussion

Over the past decades, IOUS has evolved from a complementary adjunct into a versatile imaging modality that continues to broaden its indications in neurosurgery. The field is now witnessing a convergence of three parallel trajectories: the incorporation of iOUS into minimally invasive and endoscopic procedures, the development of novel ultrasound-based functional and intelligent technologies and the integration of IOUS into multimodal intraoperative ecosystems. These advances hold promise to reshape neurosurgical workflows, yet they also highlight persistent limitations and the urgent need for standardized validation. While early generations of IOUS were predominantly anatomical, recent innovations have expanded its scope into functional, biomechanical and even intelligent domains. CEUS has emerged as a valuable adjunct for brain tumor surgery, offering superior delineation of tumor margins and perfusion characteristics compared with conventional B-mode imaging. Prospective comparative studies report that CEUS facilitates differentiation between tumor and peritumoral edema and improves detection of residual tumor tissue [89]. These studies are mostly nonrandomized; thus, statements of benefit should be considered associational. Shear-wave elastography (SWE) further extends this paradigm by quantifying tissue stiffness. Given that gliomas and metastases often differ in their biomechanical properties from surrounding parenchyma, SWE has been investigated as an intraoperative tool for grading and for guiding resection margins. Meanwhile, microflow or superb microvascular imaging (MFI/SMI) provide visualization of the microvasculature beyond the resolution of Doppler techniques, potentially guiding resection in highly vascular tumors. These functional modalities illustrate a broader transition from US as a purely structural modality toward a multiparametric intraoperative imaging platform. In parallel, the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) into IOUS interpretation represents one of the most transformative directions. Deep learning algorithms have been trained to automate tissue classification, reduce operator-dependent artifacts and even detect residual tumor in near real time. Experimental systems for spine surgery demonstrate accurate recognition of neural structures during decompression [19], while multicenter initiatives such as BraTioUS have validated deep learning-based glioma segmentation on IOUS across heterogeneous datasets [90]. These developments underscore that AI has the potential not only to standardize interpretation but also to democratize access to expertise in centers where specialized neuroradiological support is not readily available. Another frontier lies in robotic probe manipulation. Standardized 3D sweeps are autonomously performed by robotic frameworks, aiming to reduce operator variability and generate reproducible volumetric datasets. Proof of concept studies demonstrate feasibility of autonomous probe positioning in neurosurgical settings [91]. By ensuring consistent image acquisition, robotic systems could enhance reproducibility and facilitate the incorporation of IOUS datasets into neuronavigation platforms. Finally, the steep learning curve of IOUS, long recognized as a barrier to widespread adoption, is now being addressed by simulation platforms such as USim. These tools allow trainees to rehearse case-specific scenarios, practice probe handling and correlate sonographic findings with known anatomical models [92]. Such training innovations are crucial for integrating IOUS into standard curricula and for reducing inter-operator variability, in particular in centers where exposure to high case volumes is limited. The trajectory of IOUS is increasingly defined not by its role as a stand-alone modality, but as a part of multimodal intraoperative ecosystems. The rationale is compelling: each imaging modality contributes unique strengths but also suffers intrinsic limitations. IOUS offers real-time flexibility and repeatability, while iMRI provides comprehensive anatomical reference at the cost of high resource demands. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-ALA or fluorescein visualizes tumor infiltration at the cortical surface but may underestimate deeper components. Neurophysiological monitoring maps functional pathways but lacks spatial anatomical correlation. When combined, these techniques create a more comprehensive framework for surgical decision-making. Multimodal protocols integrating neuronavigation, IOUS, 5-ALA fluorescence and iCT or PET have been associated with an increased extent of resection and lower complication rates in nonrandomized studies [42,93,94]. Given potential confounding and selection bias, causal improvements cannot be inferred. These benefits extend beyond oncology: recent evidence indicates that multimodal imaging, including IOUS, also correlates with favorable intraoperative decision-making and perioperative metrics in reconstructive and complex cranial base procedures [95]. Long-term outcome effects remain to be defined. Such findings suggest that IOUS may function as the “dynamic element” within a multimodal ecosystem, providing continuous intraoperative updates that anchor static modalities like neuronavigation or preoperative imaging.

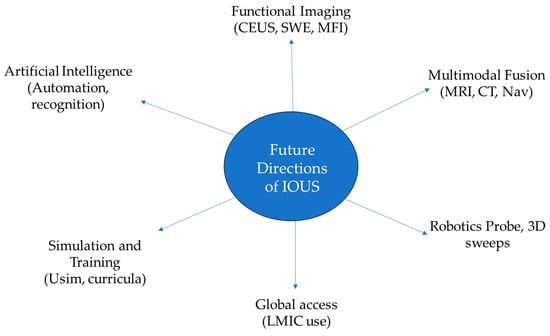

Despite significant progress, the current evidence base for IOUS remains limited and heterogenous. The majority of available studies are retrospective, single-center series with small sample sizes [28,82]. Acquisition protocols vary widely between centers, and interpretation remains strongly operator-dependent, undermining reproducibility and external validity. Although short-term outcomes such as extent of resection or decompression adequacy are frequently reported, data linking IOUS use to survival, recurrence or durable neurological function are insufficient to support causal claims at this time. Future directions must prioritize standardization and validation. Development of consensus-based acquisition protocols and structured reporting guidelines would be instrumental in facilitating reproducibility across centers. Multicenter prospective studies with predefined outcome measures are urgently required to validate the oncological and functional benefits of IOUS. These efforts could mirror the trajectory of fluorescence-guided surgery, where standardization of dosing, lighting and interpretation protocols was critical to widespread adoption. Another important frontier is the integration of emerging functional modalities and AI-driven interpretation into routine workflow. Global equity also represents an underappreciated dimension of IOUS. Reports from low- and middle-income countries demonstrate the feasibility of IOUS implementation in resource-limited settings, with meaningful improvements in safety and surgical precision [41] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Future directions of iOUS: transition of IOUS from a supportive adjunct to a core component of multimodal intraoperative imaging.

12. Conclusions

Intraoperative US is emerging as a key adjunct in neurosurgery; its trajectory is defined by an expanding spectrum of applications, from minimally invasive surgery to neuroendoscopic interventions and from functional tumor imaging to robotic-assisted acquisition. Yet its transformative potential lies in its integration with intelligent algorithms, with multimodal imaging and with global health strategies. Realizing this potential will require prospective, preferably multicenter studies that report effect sizes for survival and functional endpoints and are designed to mitigate bias, alongside standardized protocols and equitable dissemination. Only then will IOUS fully mature from a versatile adjunct into a cornerstone of neurosurgical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and N.P.; methodology, C.P. and N.P.; software, C.P. and N.P.; validation, C.P. and N.P.; formal analysis, C.P. and N.P.; investigation, C.P. and N.P.; resources, C.P. and N.P.; data curation, C.P. and N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P. and N.P.; writing—review and editing, C.P. and N.P.; visualization, C.P., N.P., V.M., A.P., C.S. and R.D.C.; supervision, C.P. and N.P.; project administration, C.P. and N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOUS | Intraoperative ultrasound |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| OPLL | Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament |

| EOR | Extent of resection |

| GTR | Gross total resection |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| SCI | Spinal cord injury |

| PSO | Pedicle subtraction osteotomy |

| CEUS | Contrast-enhanced ultrasound |

| DCM | Degenerative cervical myelopathy |

| MFI/SMI | Microflow or superb microvascular imaging |

| SWE | Shear-wave elastography |

References

- Gerard, I.J.; Kersten-Oertel, M.; Petrecca, K.; Sirhan, D.; Hall, J.A.; Collins, D.L. Brain shift in neuronavigation of brain tumors: A review. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 35, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giammalva, G.R.; Ferini, G.; Musso, S.; Salvaggio, G.; Pino, M.A.; Gerardi, R.M.; Brunasso, L.; Costanzo, R.; Paolini, F.; Di Bonaventura, R.; et al. Intraoperative Ultrasound: Emerging Technology and Novel Applications in Brain Tumor Surgery. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 818446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saß, B.; Zivkovic, D.; Pojskic, M.; Nimsky, C.; Bopp, M.H.A. Navigated Intraoperative 3D Ultrasound in Glioblastoma Surgery: Analysis of Imaging Features and Impact on Extent of Resection. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 883584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dohrmann, G.J.; Rubin, J.M. Intraoperative ultrasound imaging of the spinal cord: Syringomyelia, cysts, and tumors—A preliminary report. Surg. Neurol. 1982, 18, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.M.; Dohrmann, G.J. Use of ultrasonically guided probes and catheters in neurosurgery. Surg. Neurol. 1982, 18, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokich, P.M.; Rubin, J.M.; Dohrmann, G.J. Intraoperative ultrasonic evaluation of spinal cord motion. J. Neurosurg. 1984, 60, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein Gunnewiek, K.; van Baarsen, K.M.; Graus, E.H.M.; Brink, W.M.; Lequin, M.H.; Hoving, E.W. Navigated intraoperative ultrasound in pediatric brain tumors. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2024, 40, 2697–2705, Erratum in Childs Nerv. Syst. 2025, 41, 156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-025-06824-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trevisi, G.; Barbone, P.; Treglia, G.; Mattoli, M.V.; Mangiola, A. Reliability of intraoperative ultrasound in detecting tumor residual after brain diffuse glioma surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2020, 43, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bene, M.; DiMeco, F.; Unsgård, G. Editorial: Intraoperative Ultrasound in Brain Tumor Surgery: State-Of-The-Art and Future Perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 780517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Franzini, A.; Moosa, S.; Prada, F.; Elias, W.J. Ultrasound Ablation in Neurosurgery: Current Clinical Applications and Future Perspectives. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennari, A.G.; Doniselli, F.M.; Coley, J.; Grisoli, M.; Quaia, E.; Souchon, R.; Prada, F.; DiMeco, F. Intraoperative Comparison Between Strain Elastography and Preoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in High-Grade Gliomas Using Fusion Imaging: A Pilot Study. World Neurosurg. 2024, 192, e83–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giussani, C.; Trezza, A.; Ricciuti, V.; Di Cristofori, A.; Held, A.; Isella, V.; Massimino, M. Intraoperative MRI versus intraoperative ultrasound in pediatric brain tumor surgery: Is expensive better than cheap? A review of the literature. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2022, 38, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayachy, L.; Prada, F. Multimodality Structural and Functional Monitoring in Brain Tumor Surgery: The Role of IONM and IOUS. Adv. Tech. Stand. Neurosurg. 2024, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Si, D.; Shen, L. Diagnostic ability of intraoperative ultrasound for identifying tumor residual in glioma surgery operation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 73105–73114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coburger, J.; Scheuerle, A.; Kapapa, T.; Engelke, J.; Thal, D.R.; Wirtz, C.R.; König, R. Sensitivity and specificity of linear array intraoperative ultrasound in glioblastoma surgery: A comparative study with high field intraoperative MRI and conventional sector array ultrasound. Neurosurg. Rev. 2015, 38, 499–509; discussion 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.A.; Skaggs, D.L.; Gipsman, A.; Kiehna, E.; Andras, L.M. Intraoperative Ultrasound Provides Dynamic, Real-Time Evaluation of the Spinal Cord and Can Be Useful in Cases of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Signal Changes: A Report of 3 Cases. JBJS Case Connect. 2020, 10, e0501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toossi, A.; Everaert, D.G.; Seres, P.; Jaremko, J.L.; Robinson, K.; Kao, C.C.; Konrad, P.E.; Mushahwar, V.K. Ultrasound-guided spinal stereotactic system for intraspinal implants. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2018, 29, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.; Yu, M.; Wei, F.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. One-stage posterior surgery with intraoperative ultrasound assistance for thoracic myelopathy with simultaneous ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum at the same segment: A minimum 5-year follow-up study. Spine J. 2020, 20, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, T.; Ghoshal, G.; Cornwall, G.B.; Tobias, R.; Schwartz, D.G.; Foley, K.T. Artificial Intelligence-enabled, Real-time Intraoperative Ultrasound Imaging of Neural Structures Within the Psoas: Validation in a Porcine Spine Model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021, 46, E146–E152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Albakr, A.; Ben-Israel, D.; Yang, R.; Kruger, A.; Alhothali, W.; Al Towim, A.; Lama, S.; Ajlan, A.; Riva-Cambrin, J.; Prada, F.; et al. Ultrasound Elastography in Neurosurgery: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. World Neurosurg. 2023, 170, 195–205.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, F.; Ciocca, R.; Corradino, N.; Gionso, M.; Raspagliesi, L.; Vetrano, I.G.; Doniselli, F.; Del Bene, M.; DiMeco, F. Multiparametric Intraoperative Ultrasound in Oncological Neurosurgery: A Pictorial Essay. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 881661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Selbekk, T.; Jakola, A.S.; Solheim, O.; Johansen, T.F.; Lindseth, F.; Reinertsen, I.; Unsgård, G. Ultrasound imaging in neurosurgery: Approaches to minimize surgically induced image artefacts for improved resection control. Acta Neurochir. 2013, 155, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Unsgaard, G.; Selbekk, T.; Brostrup Müller, T.; Ommedal, S.; Torp, S.H.; Myhr, G.; Bang, J.; Nagelhus Hernes, T.A. Ability of navigated 3D ultrasound to delineate gliomas and metastases-comparison of image interpretations with histopathology. Acta Neurochir. 2005, 147, 1259–1269; discussion 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiyadi, A.V.; Shetty, P. Direct navigated 3D ultrasound for resection of brain tumors: A useful tool for intraoperative image guidance. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 40, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. AI Act Enters into Force (Timeline and Obligations). Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/news-and-media/news/ai-act-enters-force-2024-08-01_en (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- U.S. FDA. Marketing Submission Recommendations for Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs) for Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Enabled Devices; U.S. FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2025.

- Yeole, U.; Singh, V.; Mishra, A.; Shaikh, S.; Shetty, P.; Moiyadi, A. Navigated intraoperative ultrasonography for brain tumors: A pictorial essay on the technique, its utility, and its benefits in neuro-oncology. Ultrasonography 2020, 39, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Šteňo, A.; Buvala, J.; Babková, V.; Kiss, A.; Toma, D.; Lysak, A. Current Limitations of Intraoperative Ultrasound in Brain Tumor Surgery. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 659048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Simfukwe, K.; Iakimov, I.; Sufianov, R.; Borba, L.; Mastronardi, L.; Shumadalova, A. Application of Intraoperative Ultrasound Navigation in Neurosurgery. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 900986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaale, A.J.; Rutabasibwa, N.; Mchome, L.L.; Lillehei, K.O.; Honce, J.M.; Kahamba, J.; Ormond, D.R. The use of intraoperative neurosurgical ultrasound for surgical navigation in low- and middle-income countries: The initial experience in Tanzania. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 134, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, F.; Vetrano, I.G.; Gennari, A.G.; Mauri, G.; Martegani, A.; Solbiati, L.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Quaia, E.; Kearns, K.N.; Kalani, M.Y.S.; et al. How to Perform Intra-Operative Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of the Brain-A WFUMB Position Paper. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 2006–2016, Erratum in Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 3028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2021.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiraghi, A.; Prada, F.; Delaidelli, A.; Guatta, R.; May, A.; Bartoli, A.; Saini, M.; Perin, A.; Wälchli, T.; Momjian, S.; et al. Navigated Intraoperative 2-Dimensional Ultrasound in High-Grade Glioma Surgery: Impact on Extent of Resection and Patient Outcome. Oper. Neurosurg. 2020, 18, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bene, M.; Perin, A.; Casali, C.; Legnani, F.; Saladino, A.; Mattei, L.; Vetrano, I.G.; Saini, M.; DiMeco, F.; Prada, F. Advanced Ultrasound Imaging in Glioma Surgery: Beyond Gray-Scale B-mode. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shetty, P.; Yeole, U.; Singh, V.; Moiyadi, A. Navigated ultrasound-based image guidance during resection of gliomas: Practical utility in intraoperative decision-making and outcomes. Neurosurg. Focus 2021, 50, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, G.; Xie, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, H. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound can differentiate the level of glioma infiltration and correlate it with biological behavior: A study based on local pathology. J. Ultrasound 2025, 28, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, C.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Yu, J.; Ding, H. Quantitative analysis using intraoperative contrast-enhanced ultrasound in adult-type diffuse gliomas with isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations: Association between hemodynamics and molecular features. Ultrasonography 2023, 42, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, W.; Chen, P.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F. Progress in the application of ultrasound in glioma surgery. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1388728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaed, I.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Cannizzaro, D.; Menna, G.; Cardia, A. Applicability and efficacy of ultrasound elastography in neurosurgery: A systematic review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2023, 67, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sîrbu, O.M.; Chirtes, A.V.; Mitrica, M.; Gorgan, R.M. Combined use of intraoperative ultrasound and sodium fluorescein in the surgical resection of brain metastases: A preliminary observational study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 140, 111507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro-Osorio, E.; Perez-Ruano, L.A.; Figueroa Sanchez, J.A. Concordance of Extent of Resection Between Intraoperative Ultrasound and Postoperative MRI in Brain and Spine Tumor Resection. Cureus 2024, 16, e74101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo, X.; Xing, H.; Pan, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, N.; Wang, Y.; et al. Neuronavigation Combined With Intraoperative Ultrasound and Intraoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Versus Neuronavigation Alone in Diffuse Glioma Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2024, 192, e355–e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cristofori, A.; Carone, G.; Rocca, A.; Rui, C.B.; Trezza, A.; Carrabba, G.; Giussani, C. Fluorescence and Intraoperative Ultrasound as Surgical Adjuncts for Brain Metastases Resection: What Do We Know? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers 2023, 15, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, P.R.; Choi, B.D.; Aghi, M.K.; Nahed, B.V. Surgical advances in the management of brain metastases. Neurooncol. Adv. 2021, 3 (Suppl. S5), v4–v15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singhal, A.; Ross Hengel, A.; Steinbok, P.; Doug Cochrane, D. Intraoperative ultrasound in pediatric brain tumors: Does the surgeon get it right? Childs Nerv. Syst. 2015, 31, 2353–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carai, A.; De Benedictis, A.; Calloni, T.; Onorini, N.; Paternò, G.; Randi, F.; Colafati, G.S.; Mastronuzzi, A.; Marras, C.E. Intraoperative Ultrasound-Assisted Extent of Resection Assessment in Pediatric Neurosurgical Oncology. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 660805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lekht, I.; Brauner, N.; Bakhsheshian, J.; Chang, K.E.; Gulati, M.; Shiroishi, M.S.; Grant, E.G.; Christian, E.; Zada, G. Versatile utilization of real-time intraoperative contrast-enhanced ultrasound in cranial neurosurgery: Technical note and retrospective case series. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 40, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.D.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zee, C.S. Intraoperative ultrasound assistance in the resection of small, deep-seated, or ill-defined intracerebral lesions. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 3302–3308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Certo, F.; Altieri, R.; Grasso, G.; Barbagallo, G.M.V. Role of i-CT, i-US, and Neuromonitoring in Surgical Management of Brain Cavernous Malformations and Arteriovenous Malformations: A Case Series. World Neurosurg. 2022, 159, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosallami Aghili, S.M.; Maroufi, S.F.; Sabahi, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, M.; Dabecco, R.; Adada, B.; Borghei-Razavi, H. Intraoperative Ultrasonography in Pituitary Surgery Revisited: An Institutional Experience and Systematic Review on Applications and Considerations. World Neurosurg. 2023, 176, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, H.J.; Vercauteren, T.; Ourselin, S.; Dorward, N.L. Intraoperative Ultrasound in Patients Undergoing Transsphenoidal Surgery for Pituitary Adenoma: Systematic Review [corrected]. World Neurosurg. 2017, 106, 680–685, Erratum in World Neurosurg. 2018, 109, 514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshareef, M.; Lowe, S.; Park, Y.; Frankel, B. Utility of intraoperative ultrasonography for resection of pituitary adenomas: A comparative retrospective study. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, A.C.; Winter, K.A.; Smalley, Z.P.; Godil, S.; Luzardo, G.; Washington, C.W.; Prevedello, D.M.; Stringer, S.P.; Zachariah, M. Side-Firing Intraoperative Ultrasonograhy for Resection of Giant Pituitary Adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2023, 173, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, K.E.; Robbins, A.C.; Wasson, R.G.; McCandless, M.G.; Lirette, S.T.; Kimball, R.J.; Washington, C.W.; Luzardo, G.D.; Stringer, S.P.; Zachariah, M.A. Side-firing intraoperative ultrasound applied to resection of pituitary macroadenomas and giant adenomas: A single-center retrospective case-control study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1043697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solheim, O.; Selbekk, T.; Løvstakken, L.; Tangen, G.A.; Solberg, O.V.; Johansen, T.F.; Cappelen, J.; Unsgård, G. Intrasellar ultrasound in transsphenoidal surgery: A novel technique. Neurosurgery 2010, 66, 173–185; discussion 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, C.; Abouammo, M.D.; Pasquini, L.; Mansur, G.; Alsavaf, M.B.; Wu, K.C.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. Use of intraoperative ultrasound in differentiating adamantinomatous versus papillary craniopharyngiomas and guiding resection through the endoscopic endonasal route. Acta Neurochir. 2025, 167, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barbagli, G.; Hussein, A.; Quiceno, E.; Prim, M.; Soto Rubio, D.; Baaj, A. Resection of an Intradural Intramedullary C7-T1 Tumor: Technical Nuances and Complication Management. World Neurosurg. 2024, 184, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawil, M.E.; Chryssikos, T.; Rechav Ben-Natan, A.; Ambati, V.S.; Guney, E.; Shah, V.; Abla, A.A.; Mummaneni, P.V. Resection of a Thoracic Intradural Extramedullary Cavernoma Using Real-Time Intraoperative Ultrasound: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2023, 25, e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dowlati, E.; Fayed, I.; Sandhu, F.A. Microsurgical Resection of an Intramedullary Ependymoma at the Cervicomedullary Junction: A Two-Dimensional Operative Video. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawil, M.; Sorour, O.; Morshed, R.; Huang, J.; Agarwal, N.; Shabani, S.; Theodosopoulos, P.; Mummaneni, P. Use of Intraoperative Ultrasound to Achieve Gross Total Resection of a Large Cervicomedullary Ependymoma: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2023, 24, e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mastorakos, P.; Lynes, J.; Maggio, D.; Quezado, M.M.; Nduom, E.K. Resection of Myxopapillary Ependymoma of the Filum Terminale: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2020, 18, E40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. Intraoperative sonographically guided resection of hemangioblastoma in the cerebellum. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2006, 34, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wei, F.; Shi, L.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Wu, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, S. Inadequate spinal cord expansion in intraoperative ultrasound after decompression may predict neurological recovery of degenerative cervical myelopathy. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 8478–8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wei, F.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zou, X.; Liu, S. Intensity of Intraoperative Spinal Cord Hyperechogenicity as a Novel Potential Predictive Indicator of Neurological Recovery for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 22, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; He, D.; Li, L.; Chen, G.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z. Predictive value of intraoperative contrast-enhanced ultrasound in functional recovery of non-traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 2297–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.R.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, J.H.; Rhee, J.M.; Jo, W.Y.; Oh, H.; et al. The utility of intraoperative ultrasonography for spinal cord surgery. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moses, V.; Daniel, R.T.; Chacko, A.G. The value of intraoperative ultrasound in oblique corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 24, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihara, H.; Kondo, S.; Takeguchi, H.; Kohno, M.; Hachiya, M. Spinal cord morphology and dynamics during cervical laminoplasty: Evaluation with intraoperative sonography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssikos, T.; Wessell, A.; Pratt, N.; Cannarsa, G.; Sharma, A.; Olexa, J.; Han, N.; Schwartzbauer, G.; Sansur, C.; Crandall, K. Enhanced Safety of Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy Using Intraoperative Ultrasound. World Neurosurg. 2021, 152, e523–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, J.A.; Soufi, K.; Rodriguez, F.; Ebinu, J.O. Intraoperative Ultrasound: Real-Time Surgical Adjunct for Complete Resection of Spinal Arachnoid Webs. World Neurosurg. 2023, 179, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, M.; Watanabe, T.; Endo, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Miura, S.; Iwasaki, N. Pulsating Spinal Arachnoid Cyst as a Hidden Aggravating Factor for Thoracic Spondylotic Myelopathy: A Report of 3 Cases. JBJS Case Connect. 2022, 12, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.G.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H.B.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.R.; Jia, J.W.; Chen, W. Monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid flow by intraoperative ultrasound in patients with Chiari I malformation. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2011, 113, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, R.S.; Taricco, M.A.; de Oliveira, M.F.; de Lima Oliveira, M.; Teixeira, M.J.; Bor-Seng-Shu, E. Intraoperative Ultrasonography for Definition of Less Invasive Surgical Technique in Patients with Chiari Type I Malformation. World Neurosurg. 2017, 101, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Gai, Q. Surgical management of Chiari I malformation based on different cerebrospinal fluid flow patterns at the cranial-vertebral junction. Neurosurg. Rev. 2017, 40, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Iskandar, B.J.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Oakes, W.J. A critical analysis of the Chiari 1.5 malformation. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 101 (Suppl. S2), 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklar, E.M.; Quencer, R.M.; Green, B.A.; Montalvo, B.M.; Post, M.J. Complications of epidural anesthesia: MR appearance of abnormalities. Radiology 1991, 181, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssikos, T.; Stokum, J.A.; Ahmed, A.K.; Chen, C.; Wessell, A.; Cannarsa, G.; Caffes, N.; Oliver, J.; Olexa, J.; Shea, P.; et al. Surgical Decompression of Traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study Comparing Real-Time Intraoperative Ultrasound After Laminectomy With Postoperative MRI and CT Myelography. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramirez Ferrer, E.; Kimchi, G.; Tom, M.C.; Chakravarthy, V.B.; Amini, B.; Andrade de Almeida, R.A.; Zuluaga-Garcia, J.P.; Call-Orellana, F.; North, R.Y.; Alvarez-Breckenridge, C.A.; et al. Intraoperative ultrasound imaging features in high-grade metastatic spinal cord compression treated with separation surgery. Neurosurg. Focus 2025, 58, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklar, E.; Quencer, R.M.; Green, B.A.; Montalvo, B.M.; Post, M.J. Acquired spinal subarachnoid cysts: Evaluation with MR, CT myelography, and intraoperative sonography. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1989, 10, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Sidani, K.; Housheimy, M.; Kawtharani, S.; Hassanieh, J.; Amine, A. Spinal epidural abscess in an adolescent male: An unusual etiology and the role of intraoperative ultrasound. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2025, 41, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalvo, B.M.; Quencer, R.M.; Green, B.A.; Eismont, F.J.; Brown, M.J.; Brost, P. Intraoperative sonography in spinal trauma. Radiology 1984, 153, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão, L.; Ohannesian, V.A.; Almeida, L.G.S.; Pereira, K.L.A.; Menezes, I.R.; Suruagy Motta, R.F.O.; Pereira da Silva, A.M.; Nishizima, A.; Neto, M.J.F.; Joaquim, A.F.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography for Detecting Posterior Ligamentous Complex Injuries of Thoracolumbar Trauma: An Updated Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Glob. Spine J. 2025, 26, 21925682251373054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dixon, L.; Lim, A.; Grech-Sollars, M.; Nandi, D.; Camp, S. Intraoperative ultrasound in brain tumor surgery: A review and implementation guide. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, C.H.; Chen, C.M.; Jaw, F.S.; Hu, J.Z.; Wang, G.C. Ultrasound Guidance for Full Endoscopic Spinal Surgery: A Technical Note. World Neurosurg. 2022, 162, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustagi, T.; Das, K.; Chhabra, H.S. Revisiting the Role of Intraoperative Ultrasound in Spine Surgery for Extradural Pathologies: Review and Clinical Usage. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippini, A.; Prada, F.; Del Bene, M.; DiMeco, F. Intraoperative cerebral ultrasound for third ventricle colloid cyst removal: Case report. J. Ultrasound 2014, 19, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Di Somma, A.; Narros Gimenez, J.L.; Almarcha Bethencourt, J.M.; Cavallo, L.M.; Márquez-Rivas, J. Neuroendoscopic Intraoperative Ultrasound-Guided Technique for Biopsy of Paraventricular Tumors. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppido, P.A.; Fiorindi, A.; Benvenuti, L.; Cattani, F.; Cipri, S.; Gangemi, M.; Godano, U.; Longatti, P.; Mascari, C.; Morace, E.; et al. Neuroendoscopic biopsy of ventricular tumors: A multicentric experience. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, M.H.; Bassa, M.J.; Padayachy, L.; Wetzel, E.A.; Moiyadi, A.; Perin, A.; de Quintana, C.; Prada, F.; Nahed, B.V.; DiMeco, F.; et al. An International Course on Intraoperative Ultrasound in Neurosurgery: Evaluation of a Multi-center, Hands-on Courses in Promoting Familiarity and Use of Intraoperative Ultrasound in Neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2025, 29, 124524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Fang, M.; Ma, W.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Ren, T.; Lu, M. Comparison of different new ultrasonic technologies in resection assessment of neurosurgery. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 4146–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cepeda, S.; Esteban-Sinovas, O.; Singh, V.; Shetty, P.; Moiyadi, A.; Dixon, L.; Weld, A.; Anichini, G.; Giannarou, S.; Camp, S.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Glioma Segmentation of 2D Intraoperative Ultrasound Images: A Multicenter Study Using the Brain Tumor Intraoperative Ultrasound Database (BraTioUS). Cancers 2025, 17, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McDonald-Bowyer, A.; Syer, T.; Retter, A.; Stoyanov, D.; Stilli, A. Autonomous control of an ultrasound probe for intra-operative ultrasonography using vision-based shape sensing of pneumatically attachable flexible rails. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2024, 19, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perin, A.; Prada, F.U.; Moraldo, M.; Schiappacasse, A.; Galbiati, T.F.; Gambatesa, E.; d’Orio, P.; Riker, N.I.; Basso, C.; Santoro, M.; et al. USim: A New Device and App for Case-Specific, Intraoperative Ultrasound Simulation and Rehearsal in Neurosurgery. A Preliminary Study. Oper. Neurosurg. 2018, 14, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagallo, G.M.V.; Certo, F.; Di Gregorio, S.; Maione, M.; Garozzo, M.; Peschillo, S.; Altieri, R. Recurrent high-grade glioma surgery: A multimodal intraoperative protocol to safely increase extent of tumor resection and analysis of its impact on patient outcome. Neurosurg. Focus 2021, 50, E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzucchi, E.; La Rocca, G.; Hiepe, P.; Pignotti, F.; Galieri, G.; Policicchio, D.; Boccaletti, R.; Rinaldi, P.; Gaudino, S.; Ius, T.; et al. Intraoperative Integration of Multimodal Imaging to Improve Neuronavigation: A Technical Note. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alozai, M.I.; Amgad Yehia Elassra, O.; Alkhazendar, A.H.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Sattar Gatta, A.; Raza, S.M.B.; Sahnon, A.S.A.; Hj Alkhazendar, J.; Oriko, D.O.; Mushtaq, S. The Impact of Intraoperative Imaging on Outcomes in Combined Neurosurgical and Reconstructive Procedures: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e86035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).