Abstract

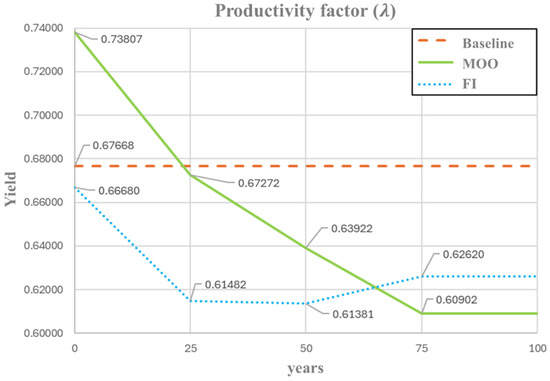

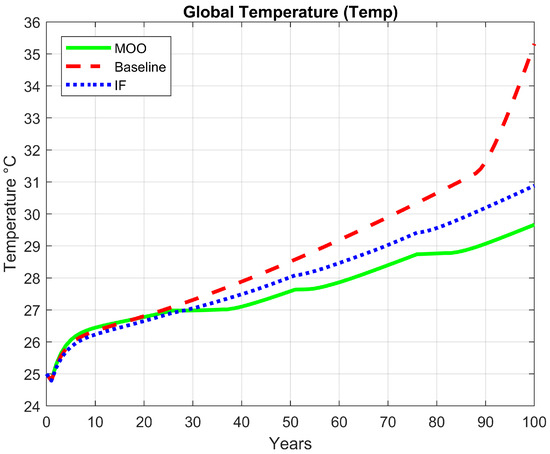

Socio-ecological systems (SESs) exhibit nonlinear feedback across environmental, social, and economic processes, requiring integrative analytical tools capable of representing such coupled dynamics. This study presents a quantitative framework that integrates a compartmental model of a global human–ecosystem with two complementary optimization approaches (Fisher Information (FI) and Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)) to evaluate policy strategies for sustainability. The model represents biophysical and socio-economic interactions across 15 compartments, incorporating feedback loops between greenhouse gas (GHG) accumulation, temperature anomalies, and trophic–economic dynamics. Six policy-relevant decision variables were selected (wild plant mortality, sectoral prices (agriculture, livestock, and industry), base wages, and resource productivity) and optimized under temporal (25-year) and magnitude (±10%) constraints to ensure policy realism. FI-based optimization enhances system stability, whereas the MOO framework balances environmental, social, and economic objectives using the Ideal Point Method. Both approaches prevent the systemic collapse observed in the baseline scenario. The FI and MOO strategies reduce terminal global temperature by 11.4% and 15.0%, respectively, relative to the baseline (35 °C → 31.0 °C under FI; 35 °C → 29.7 °C under MOO). Resource-use efficiency, measured through the resource requirement coefficient (λ), improves by 8–10% under MOO (0.6767 → 0.6090) and by 6–7% under FI (0.6668 → 0.6262). These outcomes offer actionable guidance for long-term climate policy at national and international scales. The MOO framework provided the most balanced outcomes, enhancing environmental and social performance while maintaining economic viability. Overall, the integration of optimization and information-theoretic approaches within SES models can support evidence-based public policy design, offering actionable pathways toward resilient, efficient, and equitable sustainability transitions.

1. Introduction

Socio-ecological systems (SESs) are complex systems in which natural, social, and economic dynamics interact. Integrating these dimensions remains analytically challenging because, even though they form a single system, their interactions are nonlinear and difficult to predict. Prioritizing one or two dimensions while neglecting others can lead to unintended consequences that compromise overall sustainability. These systems are often characterized by adaptability and resilience, yet they are increasingly exposed to unprecedented anthropogenic pressures driven by anthropogenic activity.

The long-term sustainability of such systems depends on the interplay among natural resources, productive activities, and social well-being [1]. Recent studies suggest that the collapse of historical civilizations was linked to a decoupling between societal demands and the ecosystem’s regenerative capacity [2]. In the 21st century, this imbalance is reflected in the global ecological footprint, which exceeds Earth’s biocapacity by a factor of 1.7 [3].

These challenges threaten not only ecological stability but also social well-being and long-term economic viability, manifesting as a multidimensional environmental crisis in three critical dimensions: (i) climate change—temperature increases of ~0.2 °C per decade and CO2 concentrations rising by ~20 ppm per decade since 2000 (ten times faster than any previous increase over the past 800,000 years) [4]; (ii) biodiversity loss—extinction rates 100–1000 times above baseline, with an estimated one million species at risk [5]; and (iii) resource depletion—degradation affecting ~90% of agricultural soils and water stress impacting ~40% of the global population [6].

These phenomena interact synergistically, creating “sacrifice zones” where vulnerable communities experience disproportionate impacts [7]. In this context, public policy faces profound challenges. Governmental planning and project selection require balancing economic, social, and ecological objectives that frequently conflict. Yet, in practice, decision-makers often prioritize immediate benefits over intergenerational sustainability [8]. As a result, the allocation of public resources is frequently shaped by political and ideological priorities, producing “project portfolios” designed to maximize the apparent impact of selected programs. Furthermore, conventional policy frameworks are hindered by at least three structural limitations: (i) fragmentation, a sectoral approach that treats interconnected problems in isolation [9]; (ii) short-termism, policy cycles that ignore the extended temporal scales of ecosystems; and (iii) institutional inertia, a persistent reluctance to incorporate scientific evidence into regulatory design [10].

In this context, sustainable public policies grounded in formal decision-making processes become imperative to balance human development with the preservation of natural systems [11]. Such policies demand integrative approaches that align socio-economic objectives with the ecological processes that sustain them [12]. Sustainability challenges operate across local and global scales, requiring governance mechanisms capable of addressing cross-scale interactions. The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda provides a universal framework for planning and evaluating policies, encouraging governments to align local strategies with international commitments through an integrated, long-term perspective [13]. Within this framework, effective sustainable public policy relies on four fundamental principles: multidimensional integration, system thinking, adaptability, and polycentric governance.

Traditional policy design has often relied on qualitative approaches or reductionist models that fail to capture the inherent complexity of SESs. By contrast, mathematical modeling provides a rigorous quantitative framework for simulating interactions among environmental, economic, and social components [14]. Over the past decades, a diverse set of modeling approaches has been developed to assess and manage the impacts of human activities on a global scale. Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), for instance, synthesize interdisciplinary knowledge to evaluate the environmental, economic, and social consequences of alternative policy pathways [15,16]. Recent studies highlight efforts to expand these models by incorporating justice, distributional impacts, and biodiversity considerations [17,18,19]. Similarly, large-scale ecosystem models—such as the Integrated Model to Assess the Global Environment (IMAGE), the Global Change Assessment Model (GCAM), and, more recently, the HARMONEY framework—offer critical insights into how human activities shape biodiversity, ecosystem services, and climate change [20,21]. Advances in general ecosystem models and end-to-end approaches [22,23], along with novel hierarchical Bayesian frameworks for multi-trophic interactions [24], underscore the ongoing evolution of quantitative tools to better capture the complexity and interconnectedness of SESs.

Despite their significant contributions, these types of ecosystem models are often highly data-intensive and computationally demanding, which can limit their accessibility and practical use in certain policy contexts. In contrast, compartmental models offer a transparent and computationally tractable alternative by simplifying complex systems into a set of interconnected compartments. Each compartment represents a conceptual category of SES elements (such as resources, productive sectors, or populations) while the flows of matter, energy, or information among them are typically described through differential equations [25]. This tractability enhances their practical relevance in policy design, as it enables rapid exploration of alternative scenarios without the prohibitive data or computational demands of large-scale IAMs. However, the simplicity that makes compartmental models policy-friendly may also constrain their ability to represent nonlinear feedback, spatial heterogeneity, and other fine-grained socio-ecological processes, making them most appropriate for stylized global analyses rather than spatially explicit local assessments. This structure captures essential system dynamics while avoiding the prohibitive data and computational demands of more complex models. Although compartmental models rely on simplifying assumptions and may introduce uncertainty in parameter estimation, they strike a balance between analytical rigor and conceptual clarity, making them particularly valuable for exploring trade-offs and informing public policy design in SESs.

Although Multi-Objective Optimization has been applied in diverse sustainability contexts, few studies have integrated such frameworks with mechanistic compartmental socio-ecological models. Existing optimization efforts typically focus on economic–environmental trade-offs or single-sector transitions, but seldom incorporate trophic–economic feedback or global biophysical constraints within a unified SES structure. Recent contributions [26,27] demonstrate the increasing methodological relevance of linking optimization with systemic models, yet they remain limited in scale and ecological integration. The present study addresses this gap by embedding an optimization framework directly into a global compartmental SES model, enabling the evaluation of policy-relevant levers under realistic biophysical and socio-economic constraints.

While compartmental models provide a tractable framework for representing the interactions within SESs, their usefulness can be significantly enhanced when combined with optimization techniques. By linking model dynamics to explicit performance criteria, it becomes possible to evaluate alternative trajectories and identify policy pathways that reconcile conflicting objectives. Building on this foundation, several studies have demonstrated that coupling compartmental models of SESs with optimization tools provides a powerful framework for generating sustainable public policy strategies. Early work by Shastri et al. [28,29] applied optimal control theory to ecological models to examine the long-term impacts of management decisions. This line of research has evolved into broader sustainability applications, such as optimizing policy mixes for energy and resource systems [30,31]. More recently, advances in computational sustainability have highlighted how these approaches can guide the design of public policies that explicitly incorporate feedback loops and systemic trade-offs [32,33]. Collectively, these works illustrate that optimization-enhanced compartmental modeling not only improves theoretical understanding of socio-ecological dynamics but also serves as a decision-support tool for crafting realistic, integrative, and sustainable public policies.

However, while valuable, such approaches frequently address isolated dimensions of sustainability. Achieving genuine sustainability requires an integrative perspective that simultaneously considers environmental objectives (e.g., reducing CO2 emissions), social objectives (e.g., improving quality of life and equity), and economic objectives (e.g., stabilizing markets and promoting growth). This balance can be approached through MOO, which evaluates multiple, often conflicting performance criteria in a systematic manner [34]. Recently, MOO has been increasingly applied to sustainability and public-policy challenges, including energy transitions [35,36], climate adaptation strategies [37,38], urban transport planning [39,40], and circular supply chains [41,42]. These applications demonstrate the ability of MOO to capture systemic trade-offs and generate feasible pathways for sustainable development. Because the formulation of objectives and constraints in MOO inherently embeds value-laden choices, the resulting solution space reflects not only biophysical and economic trade-offs but also normative priorities regarding equity, distributional fairness, and environmental protection. In this way, MOO serves as a practical tool for designing policies that reconcile environmental sustainability with growth and social justice. However, translating mathematically optimal policies into real-world decision-making is often constrained by political feasibility, institutional inertia, and administrative path dependencies, underscoring the need to interpret optimization results as strategic guidance rather than prescriptive solutions.

In this study, we build on these advances by integrating an MOO framework into the compartmental model proposed by Tovar-Ortiz et al. [43] to evaluate policy-relevant decision variables and their systemic effects on sustainability. Unlike traditional approaches that address environmental, social, or economic outcomes in isolation, our framework explicitly balances all three dimensions under realistic constraints, including gradual policy adjustments and bounded parameter changes. This integration makes it possible to generate policy profiles that are not only mathematically optimal but also politically feasible and administratively interpretable. Through this process, this study helps bridge the gap between abstract sustainability modeling and the design of actionable public policies, providing a quantitative decision-support tool to guide governments in confronting the intertwined challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion. This study pursues two complementary objectives: (i) to compare how Fisher Information and Multi-Objective Optimization influence the behavior and sustainability of a coupled human–ecosystem model, and (ii) to identify which policy-relevant variables most effectively steer the system toward long-term stability under global warming. These aims motivate the central research question: to what extent can alternative optimization paradigms guide a global socio-ecological system toward sustainable trajectories when policies are implemented under realistic temporal and magnitude constraints?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Model of a Global SES

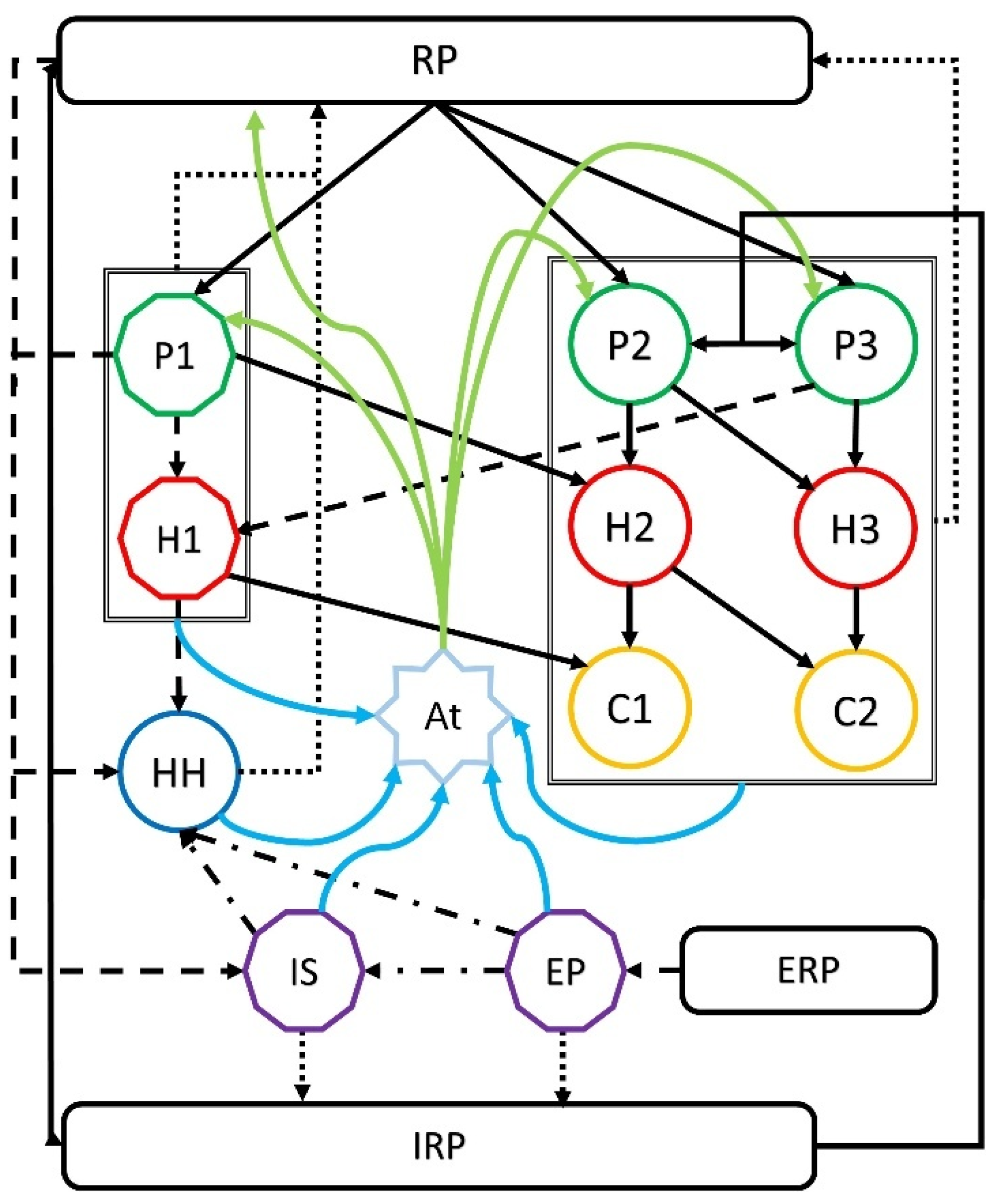

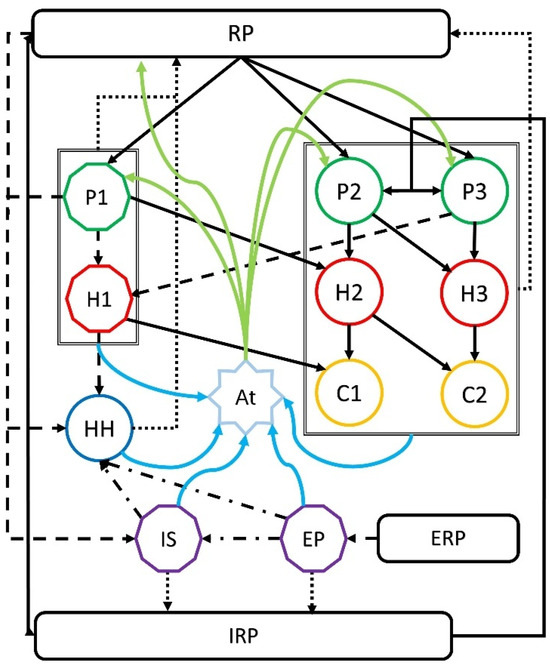

This study builds on the global warming socio-ecological system (SES) model proposed by Tovar-Ortiz et al. [43], which is conceptually represented in Figure 1. The model consists of 15 interconnected compartments representing both biophysical and socio-economic components.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the SES model.

- Resource Pools: RP (biotic/abiotic finite resources), ERP (finite energy resources), IRP (biologically inaccessible mass; waste/sinks).

- Plants: P1 (agriculture, human-managed), P2 (wild plants accessible to humans, e.g., managed forestry edge), P3 (wild plants inaccessible to humans).

- Herbivores: H1 (livestock), H2 (wild herbivores interacting with humans), H3 (wild herbivores without human interaction).

- Carnivores: C1 (wild carnivores interacting with humans), C2 (wild carnivores with no direct human interaction).

- Humans: HH, representing total human biomass, linked to the human population (NHH) through per-capita mass.

- Economy: IS (industry and services) and EP (energy production).

- Atmosphere: At, representing the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere, which directly influences the overall temperature of the system.

Flows and interactions among compartments fall into five categories: (i) Solid black arrows, natural mass or energy transfers (e.g., RP → Pi and Pi → Hj). (ii) Dotted lines, mortality and waste flows returning to RP or IRP. (iii) Dashed lines, human-mediated interactions such as grazing, predation on domestic animals, and industrial or agricultural inputs. (iv) Dash-dotted lines, economic services, production, and demand flows linking the human and industrial compartments. (v) Green and blue solid lines, GHG emissions and removals associated with biomass metabolism, energy use, and atmospheric exchange.

The dynamics of the SES model are represented by a set of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that follow the general structure of the Lotka–Volterra model for a multi-predator–prey system, as shown in Equation (1). The formulation is derived from a mass balance approach, where the rate of change in mass in compartment at any time depends on three terms: (i) Net biological growth, the difference between the natality rate and the mortality rate . (ii) Trophic interaction flows with other compartments . The interaction coefficient defines the direction and intensity of these flows, being negative when compartment is consumed by and positive when acts as the consumer. (iii) Human-drive flows, determined by algebraic socio-economic functions .

where represents the mass of compartment , being the first term of the natural increase in the compartment. The second term captures the bilinear feedback that describes trophic interactions across the system, while the last term introduces anthropogenic influence, allowing the integration of socio-economic variables into the ecological structure.

A key element of the model is the feedback loop operating, which is associated with the atmospheric compartment (). As illustrated in Figure 1, both living compartments and productive sectors act as sources of GHGs, releasing emissions into the atmosphere. Conversely, the resource pool and plant compartments function as sinks, removing part of these gases through assimilation processes. The imbalance between emitted and absorbed GHGs is translated into an increase in atmospheric GHG concentration, expressed as CO2eq.

The concentration of CO2eq is directly correlated with the temperature anomaly () according to Equation (2):

The growth factors of the primary trophic level () and the human mortality rate () are modeled as Gaussian functions of this temperature anomaly, as shown in Equations (3) and (4). As atmospheric CO2eq increases, these temperature-dependent factors modify primary productivity and human mortality, altering trophic flows and demographic dynamics throughout the system, changing the magnitudes of the compartments and, in turn, their emission and absorption rates, thus completing the feedback loop between ecosystem dynamics and atmospheric processes.

where and represent the baseline plant growth and human mortality rates, respectively; σ denotes the standard deviation, which defines the width of the Gaussian curve.

As the present model directly extends the structure developed by Tovar-Ortiz et al. [43], this section provides only an overview of its key components and governing equations. For a comprehensive description of the model structure, parameterization, and underlying assumptions, the reader is referred to the original publication.

2.2. Decision Variables (Policy Levers)

Following the methodology proposed by Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al. [44], the decision variables were selected according to two main criteria: the first was their direct interpretability in real-world systems (e.g., waste management rates or mortality of wild plants), and the second was their potential to be modified through public policy interventions. These variables were chosen to allow for gradual yet meaningful interventions, as less intrusive adjustments tend to enhance social acceptance and ensure long-term feasibility. Of the more than one hundred parameters included in the original model, only a subset met these criteria. Variables exhibiting the strongest influence on at least one sustainability dimension (environmental, social, or economic) were prioritized based on a sensitivity analysis, while also considering their practical feasibility for public implementation. First, parameters that did not satisfy the practical feasibility criteria for public implementation—primarily natural birth and death rates and wild consumption factors—were excluded. Subsequently, to identify the subset of policy-relevant variables, we conducted a local one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis, in which all biophysical and economic parameters were perturbed by ±5% around their baseline values. Normalized sensitivities were computed with respect to global temperature, human biomass, and the productive sectors. Parameters with sensitivity values above 0.15 were classified as high-influence, ensuring transparent and reproducible selection criteria. The corresponding sensitivity charts are provided in Supplementary Material S1. The selected decision variables were as follows:

- Mortality of wild plants accessible to humans (): This variable reflects the level of pressure exerted on semi-managed forest resources. At the policy level, it can be influenced through forest management policies, such as regulations on harvesting intensity, conservation programs, or reforestation incentives.

- Base wage (): Represents the income level of the human compartment, directly linked to labor legislation, such as minimum wage laws and social protection mechanisms. Adjustments to this variable allow the model to emulate the effects of income redistribution and wage reform on social well-being and consumption patterns.

- Prices of agricultural plants (): Corresponds to the market price or subsidy structure of food crops. It captures the effect of agricultural price policies or fiscal incentives aimed at stabilizing food production, ensuring profitability, and promoting sustainable farming practices.

- Prices of livestock herbivores (): analogous to the agricultural case but applied to the livestock sector, this variable represents pricing or subsidy mechanisms that can regulate the intensity of animal production and its associated environmental impact.

- Prices of industrial services and manufacturing (): Reflects the influence of taxes, subsidies, or regulatory instruments that encourage or restrict industrial activities. It serves as a proxy for fiscal and environmental policy tools targeting production efficiency and emission control.

- Resource productivity factor (): Represents the efficiency of biotic and abiotic resource use, encompassing technological innovation, circular economy measures, and policies promoting sustainable production. In practice, it can be improved through technological modernization programs and public investment in resource efficiency initiatives.

2.3. Policy Realism Constraints

Although the model structure is already defined, it must be adapted to fit within an optimization framework. In this context, additional constraints are required to ensure that the resulting solutions remain realistic and interpretable in policy terms, i.e., that the optimal profiles of the decision variables can be translated into feasible public policies. This adjustment ensures that the model adequately represents real-world decision-making processes in SESs. In practice, when implementing policies such as wage adjustments or agricultural subsidies, their effects manifest gradually over time and must remain within realistic magnitudes to guarantee political feasibility and social acceptance. Consequently, two primary aspects must be considered in model design: temporality and magnitude.

2.3.1. Time Periods

Temporal conditions were incorporated into the model to represent multiple policy periods. Specifically, four periods of 25 years each were defined, resulting in a total simulation horizon of 100 years [28]. This temporal structure allows each decision variable to be updated at the beginning of every period, thereby enabling the evaluation of dynamic policy strategies over time and their adaptability to evolving system conditions and policy environments. To implement this temporal segmentation, the system equations involving decision variables were modified to include time-dependent conditional terms. For instance, the model estimates the per-capita wage () for each period k using Equation (5), which links income levels to both the supply–demand gap of industrial services (IS) and the available labor force ():

where and represent the deficit and target inventory of industrial services (IS); and are the yields of RP and P1, respectively; the coefficients , y are constant parameters. In this equation, denotes the active policy period, modifying the system’s behavior as the simulation progresses through time (period 1 corresponds to years 1–25, period 2 to years 26–50, and so forth).

2.3.2. Range Constraints

In addition to temporal segmentation, magnitude constraints were imposed to bound the magnitude of policy changes. Specifically, each decision variable was limited to a ±10% variation relative to its previous value. This ensures that parameter adjustments remain incremental and realistic, reflecting the gradual nature of policy implementation in real socio-economic systems. The ±10% bound was selected to reflect realistic and politically feasible policy adjustments. Gradual modifications of this magnitude are commonly adopted in economic and environmental regulatory frameworks, where large abrupt changes may generate social resistance or institutional infeasibility. Similar bounded adjustment assumptions were employed in sustainability optimization studies [28,30]. These limits were implemented using inequality constraints, restricting the permissible range of each decision variable across periods. For example, for a decision variable x optimized for the period , the range constraints are expressed in Equations (6) and (7):

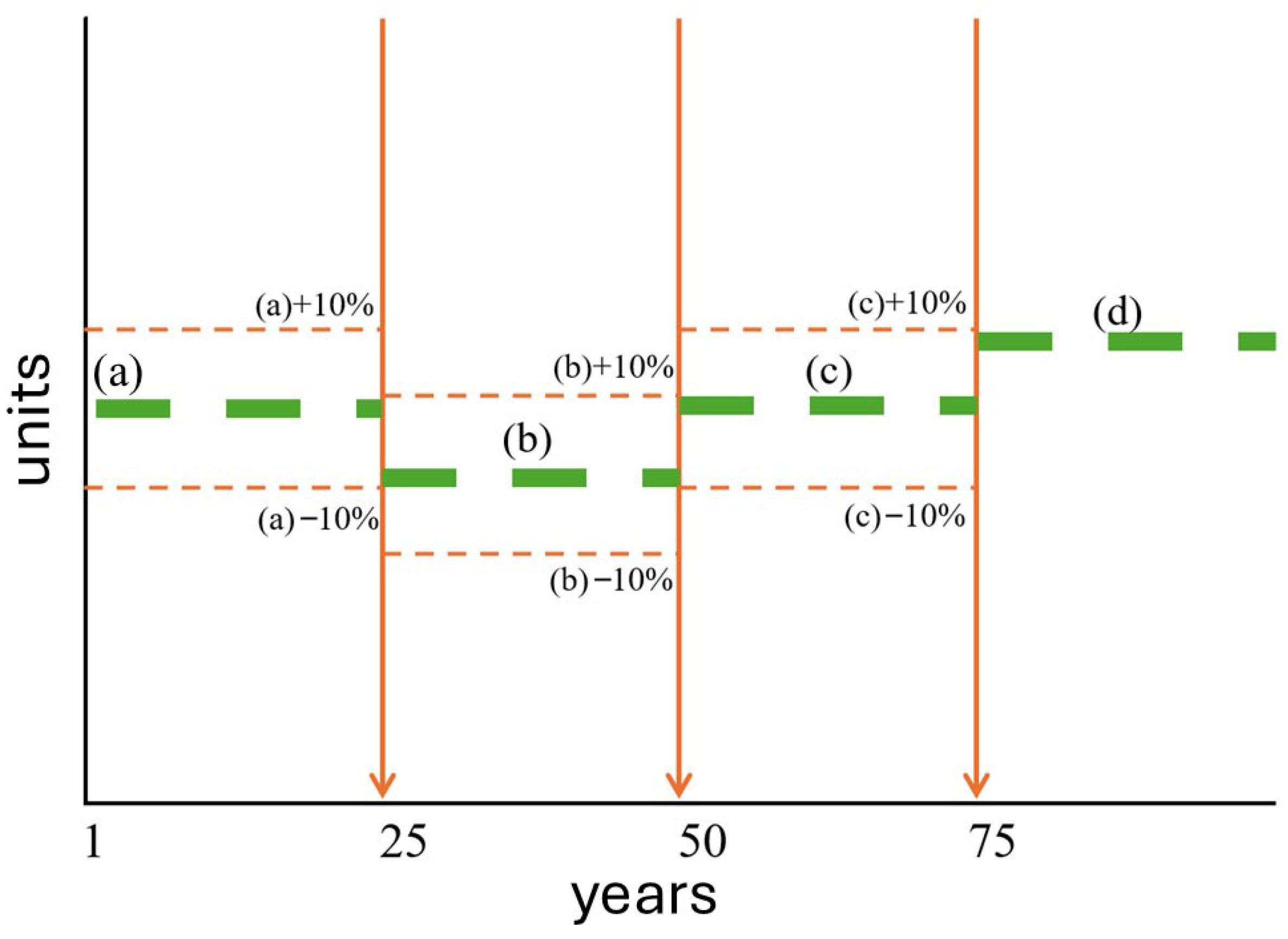

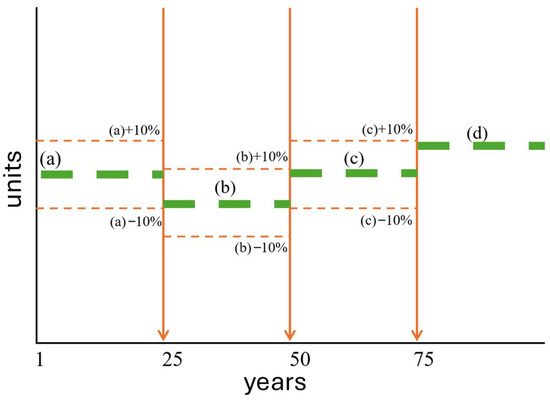

Figure 2 illustrates these mechanisms jointly: the optimal value of the decision variable remains constant (value (a)) during the first 24 years. At year 25, its new optimal value (b) is recalculated based on the updated system state and is constrained within ±10% of (a). This process is repeated at the beginning of each subsequent period, ensuring gradual and realistic adjustments throughout the 100-year simulation horizon.

Figure 2.

Illustration of temporal evolution of the optimal decision variable.

2.4. Sustainability Objectives

Once the decision variables were defined and the mathematical model with its constraints established, the next step was to determine an appropriate objective function. Because the goal is to stabilize the system in such a way as to achieve a sustainable SES, it is vitally important to establish a function that adequately captures and quantifies the multidimensional nature of sustainability. In this study, sustainability is assessed using two complementary approaches. First, a global sustainable indicator is used as the sole function, and then a multi-objective approach is implemented.

2.4.1. Single Global Sustainable Objective

Conceptually, Fisher Information (FI) represents the amount of information about the system’s state that can be extracted from observations of its variables. FI can be used to quantify the degree of order, stability, or dynamic regime within a system, providing insight into its organizational state and capacity for sustainability [45]. González-Mejía et al. [46] further refined this framework, summarizing the latest formulation of the sustainable regime hypothesis in four key statements.

- A system in an orderly dynamic regime does not change its overall condition with time, having a steady nonzero FI;

- A steadily decreasing FI implies a loss of dynamic order, denoting that the system is changing rapidly and losing stability;

- An increasing FI indicates that the system is slowing and, possibly, becoming more ordered;

- A significant, and sometimes abrupt, change in FI between two stable dynamic regimes denotes a regime shift.

The time-averaged FI for a system with n species is given by Equation (8) [32]:

where is the cycle time of the system; and are the velocity and acceleration terms, respectively (Equations (9) and (10)).

FI was successfully applied as a global indicator of sustainability in studies like the present work [32,44]. Its importance lies in its ability to integrate multiple dimensions of sustainability within a single-objective framework, allowing for the detailed analysis of variables that can be controlled in real-world settings and that exert significant influence on other components of the ecosystem.

In this study, a Bolza-type objective function [47] is employed to minimize the standard deviation of the FI time series relative to a baseline scenario, as expressed in Equation (11):

This formulation essentially represents a variability and terminal-state penalization index for the FI trajectory. The first term quantifies the sum of squared deviations of each FI value from its mean , which is equivalent to the total variance of the time series. Higher values indicate a more unstable or fluctuating system over time. The second term, weighted by a factor of 100 due to the analysis time horizon, emphasizes the final state of the simulation relative to the historical meaning. Consequently, if the system ends in a state where FI significantly deviates from its long-term behavior, the objective function Z increases sharply, signaling potential regime shifts or critical departures from stable dynamics at the end of the simulation.

2.4.2. Multi-Objective Approach

Although FI provides a useful global sustainability indicator, it also exhibits limitations that must be acknowledged. Its mathematical formulation can become complex, hindering its practical application and quantification in real human–ecosystem systems. Moreover, Rodríguez-González et al. [44] demonstrated that different human ecosystems respond uniquely to distinct objective functions. Therefore, each system requires a specific objective formulation adapted to its socio-environmental context and intrinsic characteristics.

The present model explicitly represents the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of the system components, which often operate in conflict with one another. Adopting an MOO framework enables an integrated sustainability approach by simultaneously improving system performance across all three dimensions. For the optimization to be meaningful, each objective function must achieve the following:

- Accurately represent its corresponding dimension;

- Exert a significant influence on the global system;

- Correspond to a real-world measurable or controllable quantity, ensuring that the results can be translated into feasible policy actions.

From the environmental perspective, the main challenge for the system is global warming, represented by the increase in atmospheric temperature. Accordingly, the environmental objective function (Equation (12)) minimizes the final atmospheric temperature value, , at the end of the simulation horizon . This formulation grants the system flexibility to improve the objective value by focusing on long-term stabilization.

From the economic perspective, the model considers that fluctuations in productive sectors negatively affect system stability. Thus, the economic objective function (Equation (13)) seeks to minimize the aggregate variability in the key productive sectors: agriculture (P1), livestock (H1), industry (IS), and energy (EP). High values of indicate instability and inconsistency across sectors, whereas lower values denote a more robust and predictable economy.

From the social perspective, the objective is to maximize human well-being, represented by the total human biomass (HH) throughout the simulation period. As the model assumes that human mass increases when other resources are adequate, maximizing this value can be interpreted as improving quality of life. Equation (14) defines the social objective function :

Each objective function, when optimized individually, enhances its corresponding dimension while potentially degrading the others. Therefore, the purpose of MOO is to identify equilibrium solutions that balance trade-offs among all objectives. To achieve this, the Ideal Point Method was employed. Using Euclidean geometry, the algorithm searches for the point in objective space with the smallest distance from the ideal reference point, defined as the vector of optimal values obtained from each single-objective optimization.

The overall objective function (Equation (15)) thus minimizes the Euclidean distance between the candidate solution and the ideal sustainability point:

where , , and represent the optimal objective function values corresponding to the environmental, economic, and social dimensions, respectively, each obtained from separate single-objective optimizations. This procedure identifies equidistant trade-off points among the three dimensions, ensuring balanced benefits and minimal losses under the assumption of equal importance across all sustainability criteria.

3. Results

3.1. Benchmarking Strategies

The SES model was optimized to identify sustainable configurations using two complementary approaches: FI as a global sustainability index, and an MOO framework based on the Ideal Point Method. In addition, three single-objective optimizations, each targeting one sustainability dimension (environmental, economic, or social), were performed for comparative purposes.

Table 1 summarizes the performance of the environmental, economic, and social dimensions under each optimization scheme. Consistent with the definition of sustainability objectives, lower values of and indicate better environmental and economic performance, respectively, while higher values of represent improved social outcomes.

Table 1.

Performance of sustainability dimensions under different optimization schemes.

Each optimization strategy exhibits distinct trade-offs among the sustainability dimensions. Single-objective optimizations yield the best performance for their respective target dimension but degrade performance in the others, reflecting expected systemic trade-offs. In contrast, the FI and MOO frameworks produce more balanced solutions. FI reduces oscillations and prevents abrupt regime shifts, thereby reinforcing structural stability—a behavior consistent with its interpretation as an indicator of dynamic order and resilience [28,46]. The MOO approach, by explicitly minimizing environmental, economic, and social deviations from their ideal levels, identifies a compromise solution that enhances environmental performance while maintaining acceptable economic and social conditions.

Although the two sustainability-oriented approaches yield distinct outcomes, both effectively prevent the systemic collapse observed in the baseline scenario and succeed in maintaining the system in a state of relative equilibrium throughout the simulation period. This stability reflects their capacity to balance the feedback among environmental, economic, and social components, mitigating extreme fluctuations and ensuring long-term system viability.

However, the numerical results shown in Table 1 alone may not fully convey the systemic implications of each optimization approach. To better understand the advantages, trade-offs, and dynamic responses associated with each strategy, Section 3.2 provide a detailed analysis of the optimal decision variable profiles, as well as the temporal evolution of key compartments and state variables within the socio-ecological system. This deeper examination offers insight into how each optimization framework, FI and MOO, translates into different sustainability pathways, revealing the mechanisms that enable the system to sustain balance across its interconnected dimensions.

3.2. Optimal Policy Profiles (Decision Variables)

The optimal policy profiles derived from both the FI and MOO approaches are presented and analyzed. For comparative purposes, baseline profiles—corresponding to the unoptimized model—are also included. In the baseline case, the decision variables remain constant throughout the simulation as no policy intervention is applied. In the subsequent figures, the red dashed line represents the baseline scenario, the blue dotted line corresponds to the FI-based optimization, and the green solid line represents the MOO results.

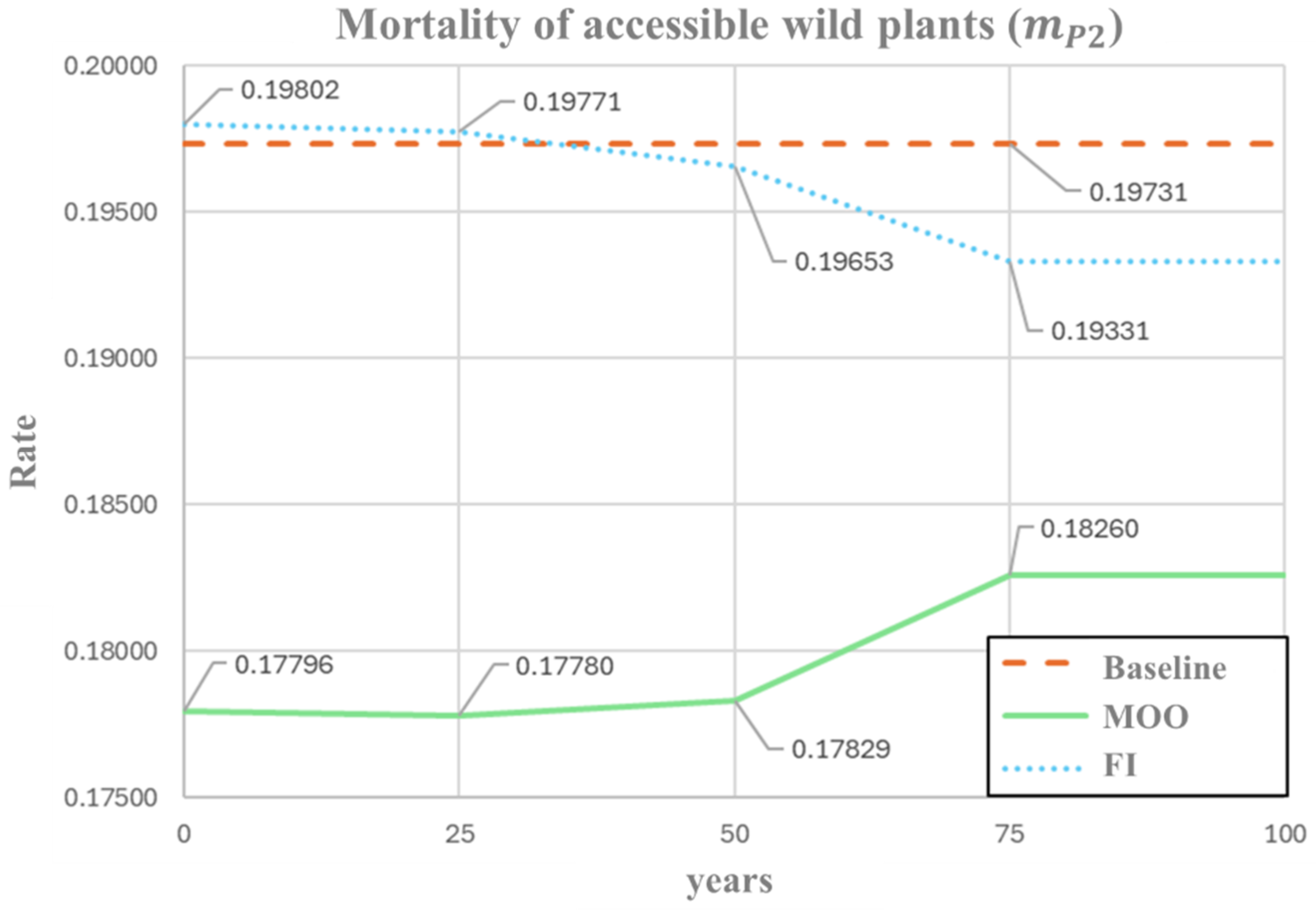

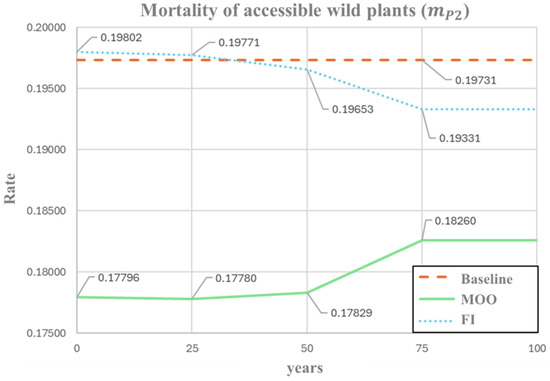

Figure 3 shows the temporal evolution of the mortality rate of wild plants accessible to humans () over a 100-year simulation horizon. The FI-based optimization exhibits a gradual decline in m_P2 from 0.1977 to 0.1933, corresponding to a 2.2% reduction relative to the baseline. This pattern suggests a progressive regulation of semi-managed vegetation, maintaining values close to current conditions while promoting long-term ecological stability. In contrast, the MOO displays an opposite trend, starting from a lower initial value (0.1779), approximately 10% below the baseline, and gradually increasing to 0.1826 toward the end of the simulation. This behavior indicates that the MOO framework emphasizes early corrective interventions followed by gradual relaxation, consistent with its objective of balancing short-term ecological improvement with long-term system stability.

Figure 3.

Optimal profile of accessible plant mortality rate () under FI and MOO approaches.

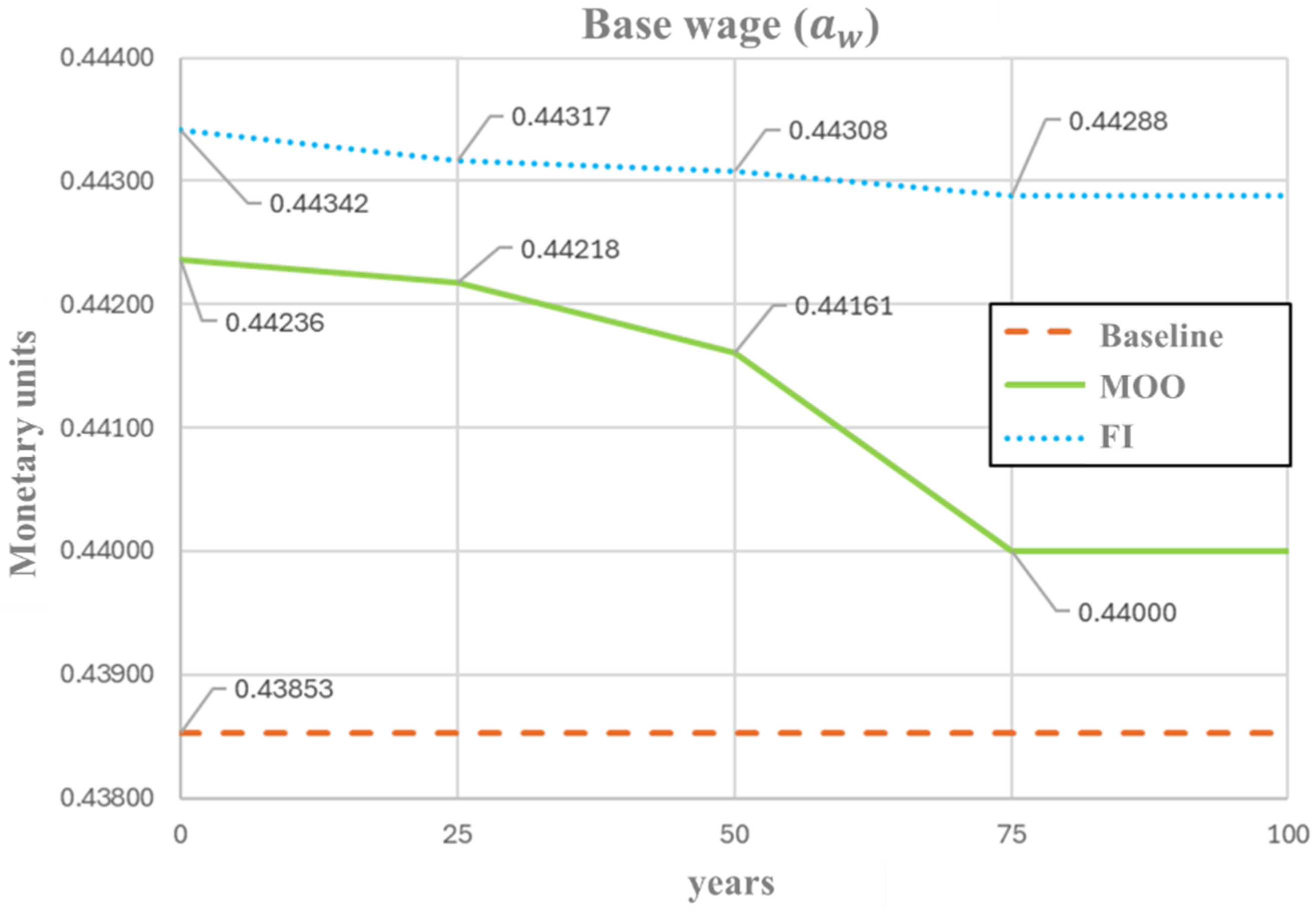

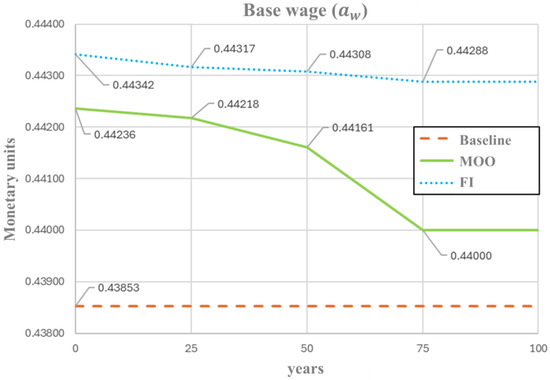

Figure 4 presents the temporal evolution of the base salary (). The MOO begins with a base salary higher than the reference level (0.4424 vs. 0.4385), followed by a gradual decrease throughout the simulation period. This pattern indicates that the MOO approach promotes an initial economic stimulus, which can be interpreted as a short-term wage policy or fiscal incentive, subsequently leading to a progressive stabilization as the system approaches a more balanced state across the sustainability dimensions. In contrast, the FI-based optimization also starts with a higher-than-reference salary (0.4434) but maintains an almost constant value over time, with minimal fluctuations. This behavior indicates that the FI framework favors steady-state economic policies, ensuring long-term income stability and preventing abrupt perturbation within the socio-economic subsystem. Both optimization schemes converge on the necessity of an initial wage increase to stabilize socio-economic dynamics under global warming. These opposite dynamics demonstrate how each optimization paradigm interprets sustainability differently—FI prioritizes systemic stability and resilience, while MOO emphasizes balanced performance and dynamic flexibility across the interacting dimensions of the socio-ecological system.

Figure 4.

Optimal profile of base wage () under FI and MOO approaches.

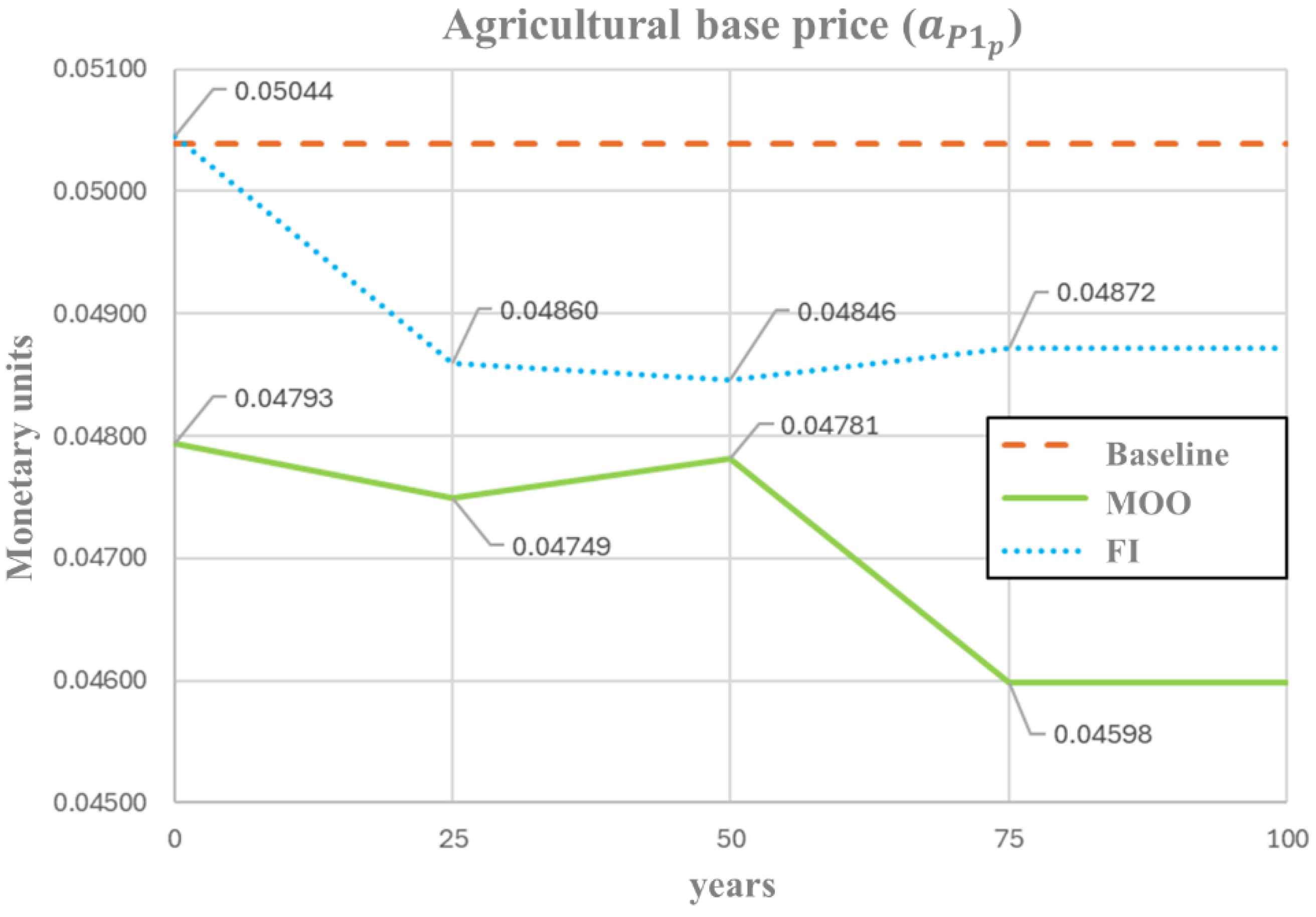

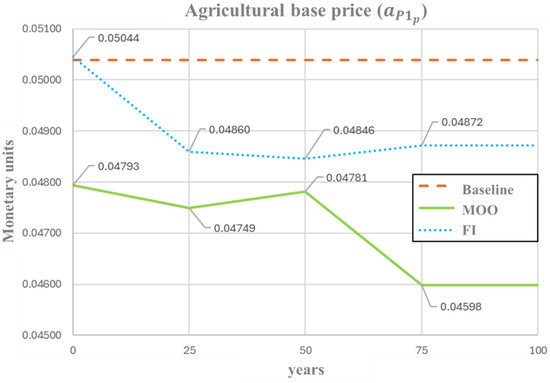

Figure 5 shows the temporal profiles of the base prices of agricultural plants () throughout the 100-year simulation period. The FI-based optimization begins at the same initial value as the baseline model (0.0504), then exhibits a decrease, stabilizing around 0.0485. This pattern indicates that the FI approach promotes a moderate reduction in and strict control of agricultural prices, consistent with stabilization of resource flows and production efficiency within the system. In contrast, the MOO starts from a lower initial price (0.0479), approximately 5% below the baseline, fluctuating every 25 years with minor oscillations, yet consistently remaining below the values obtained in the FI and baseline models. This adaptive fluctuation pattern indicates that the MOO framework offers more flexible control, allowing for periodic corrections in agricultural pricing to maintain equilibrium among the economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Figure 5.

Optimal profile of agricultural base price () under FI and MOO approaches.

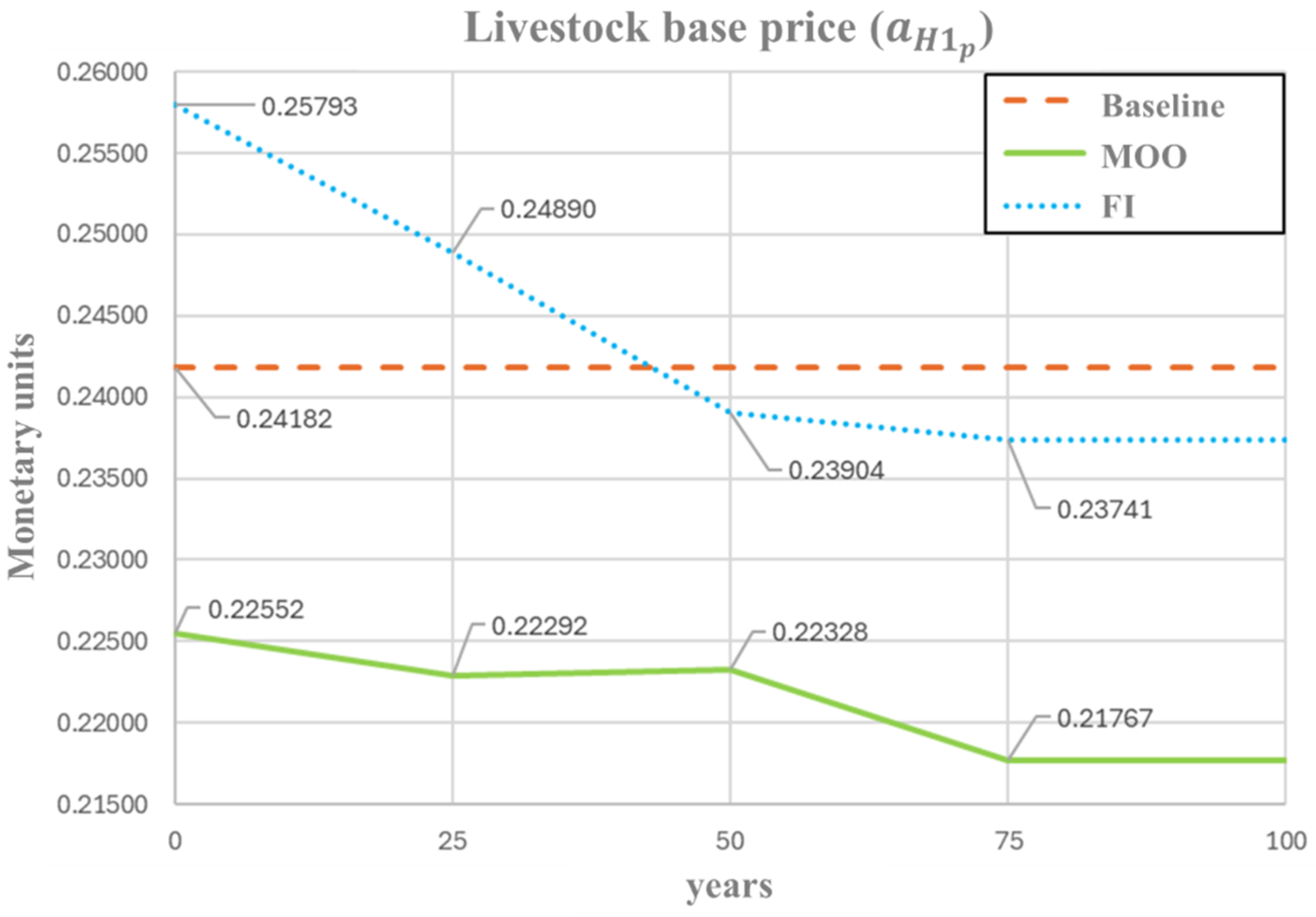

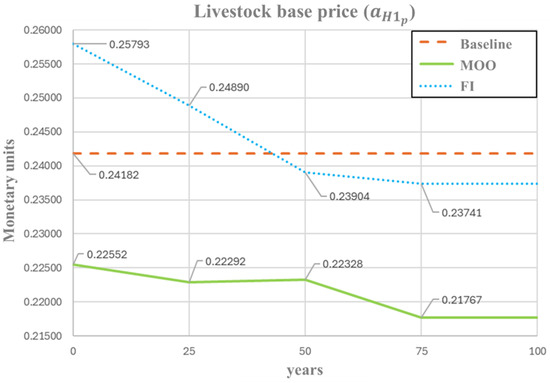

Figure 6 presents the temporal evolution of the livestock sector prices (). The MOO yields values consistently below the baseline, starting approximately 7% lower (0.2255 vs. 0.2418) and gradually decreasing throughout the simulation to reach a 10% reduction by year 75 (0.2177). This pattern of progressive price reduction in livestock reflects a policy scenario aimed at improving affordability and stabilizing demand. In contrast, the FI-based optimization begins with a value 7% higher than the baseline (0.2579), which could be considered economically unfavorable in the short term due to the sudden price increase. However, the FI trajectory shows a steady downward adjustment, ultimately converging to a value below the baseline (0.2374) by the end of the simulation. This behavior suggests a self-correcting stabilization mechanism, where initial increases are gradually offset, leading to a lower price regime.

Figure 6.

Optimal profile of livestock base price () under FI and MOO approaches.

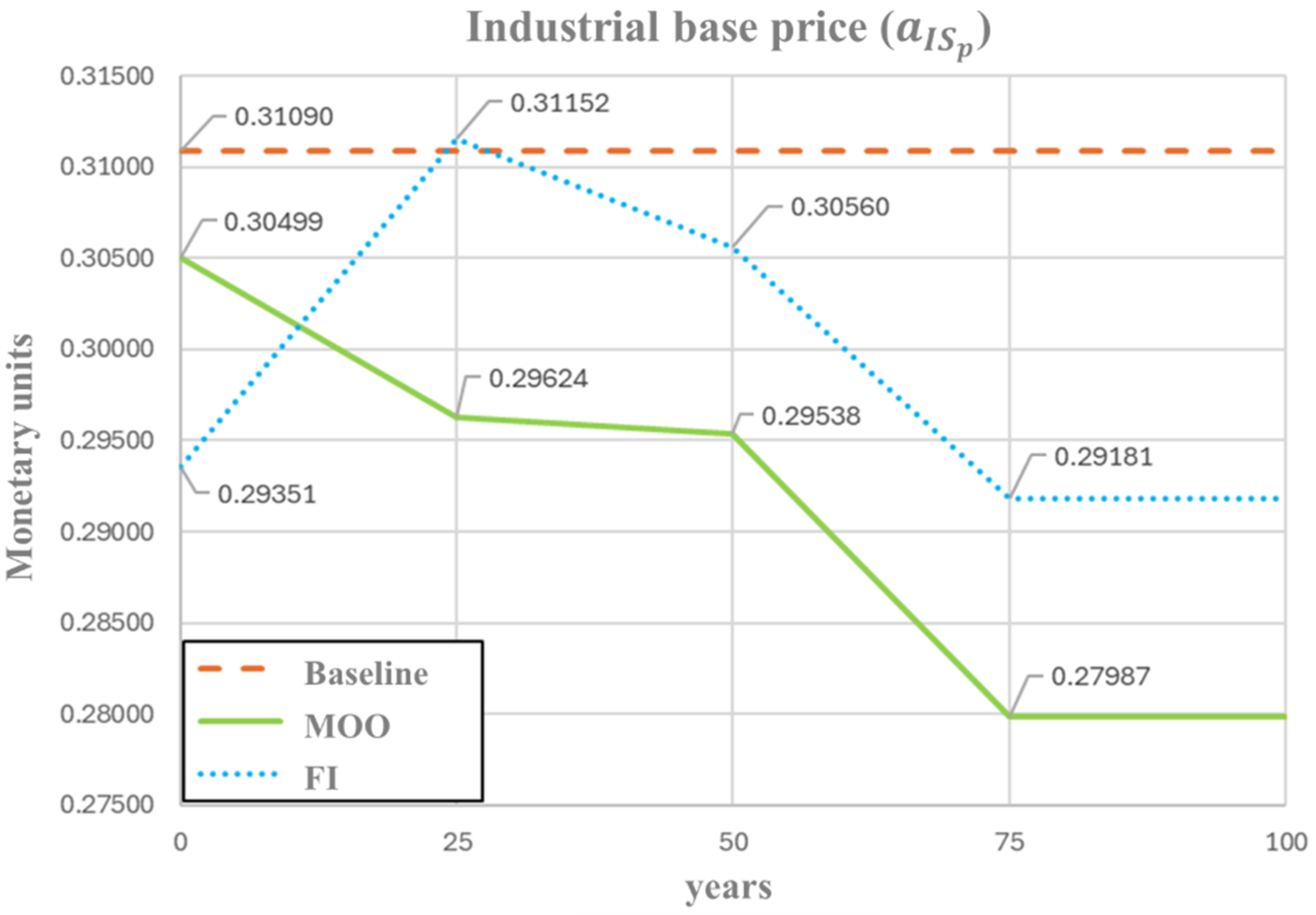

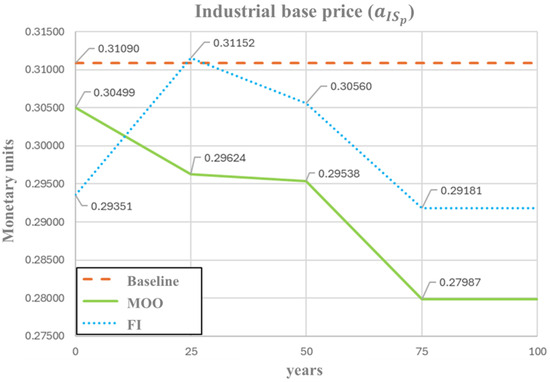

Figure 7 shows the temporal profiles of industrial and manufacturing service prices (). Both the MOO and the FI-based optimization trajectory remain consistently below the baseline value. The MOO trajectory exhibits a steady downward trend, with prices gradually decreasing from −2% (0.3049) to −10% (0.2799) relative to the baseline. This sustained decline reflects a long-term efficiency improvement in industrial production, reducing input requirements and stabilizing market conditions. On the other hand, the FI-based optimization—although starting from a slightly lower value (0.2935) and displaying an abrupt increase during the second period (0.3115)—follows a similar pattern to MOO in general. This behavior reinforces the notion of a gradual long-term cost reduction, even if short-term adjustments require sharper corrective measures.

Figure 7.

Optimal profile of industrial base price () under FI and MOO approaches.

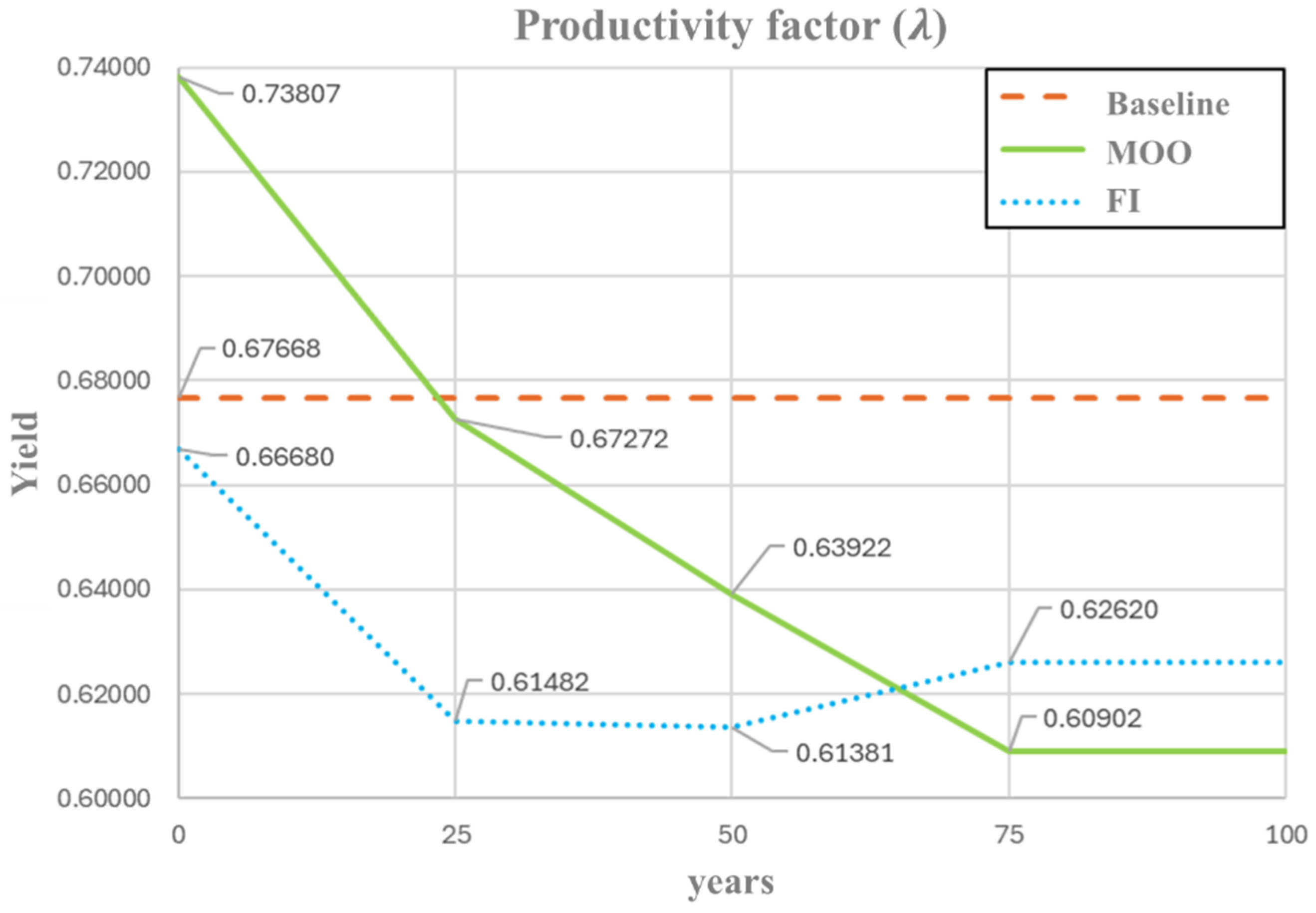

Figure 8 illustrates the temporal evolution of the resource requirement coefficient (). This parameter denotes the biophysical inputs required to generate one unit of output; therefore, it inversely reflects conversion efficiency. Lower values of λ correspond to higher resource-use efficiency, whereas higher values indicate greater input demand and reduced conversion performance. Within this interpretation, the MOO framework demonstrates a continuous enhancement of efficiency throughout the simulation period. Starting from the highest requirement level (0.7381) at the beginning of the simulation, declines steadily to 0.6090 by year 75, representing an approximate 10% improvement in conversion efficiency relative to the baseline (0.6767). This consistent downward pattern indicates that the MOO framework fosters sustained improvements in natural resource utilization, even when the system initially operates under relaxed conversion conditions. In contrast, the FI-based optimization begins slightly below the baseline (0.6668) and exhibits a more moderate decrease in during the first half of the simulation, reaching its minimum value (0.6138) around year 50, followed by a mild rebound (0.6262) toward the end. This pattern reflects a stability-oriented regulatory mechanism, through which the system prevents overexploitation by maintaining efficiency gains within a narrower and more controlled range.

Figure 8.

Optimal profile of productivity factor () under FI and MOO approaches.

The analysis of the decision variables reveals that both optimization frameworks, FI and MOO, achieve sustainability through distinct adjustment mechanisms, influencing the broader system dynamics in different ways. However, changes in these policy levers only gain full significance when their system-level implications are examined. The evolution of compartments such as resources, biomass, population, and atmospheric conditions reflects how these optimized variables propagate through the socio-ecological network, shaping the overall trajectory of the system. Therefore, Section 3.3 examines the temporal behavior of the main system states, providing a dynamic perspective on how each optimization framework drives stability, resilience, and long-term sustainability within the SES.

3.3. System Trajectories (States)

The optimal profiles represent specific system configurations that maximize or balance distinct objective functions, such as economic well-being, environmental sustainability, or social equity. In this study, the variables selected to construct these profiles were organized according to their direct association with the defined objective functions and their relevance within the sustainability dimensions. Subsequently, several structural variables are included, which, although not directly part of any individual objective function, are essential for interpreting the system’s environmental, social, and economic dynamics. The inclusion of this subset of variables, rather than the entire set available in the model, responds to relevance and analytical clarity criteria. Priority was given to variables that encapsulate the most significant information for assessing system-level sustainability performance, thereby enabling a comprehensive interpretation of the model’s behavior without compromising clarity or interpretability.

3.3.1. Environmental Trajectory (Global Temperature)

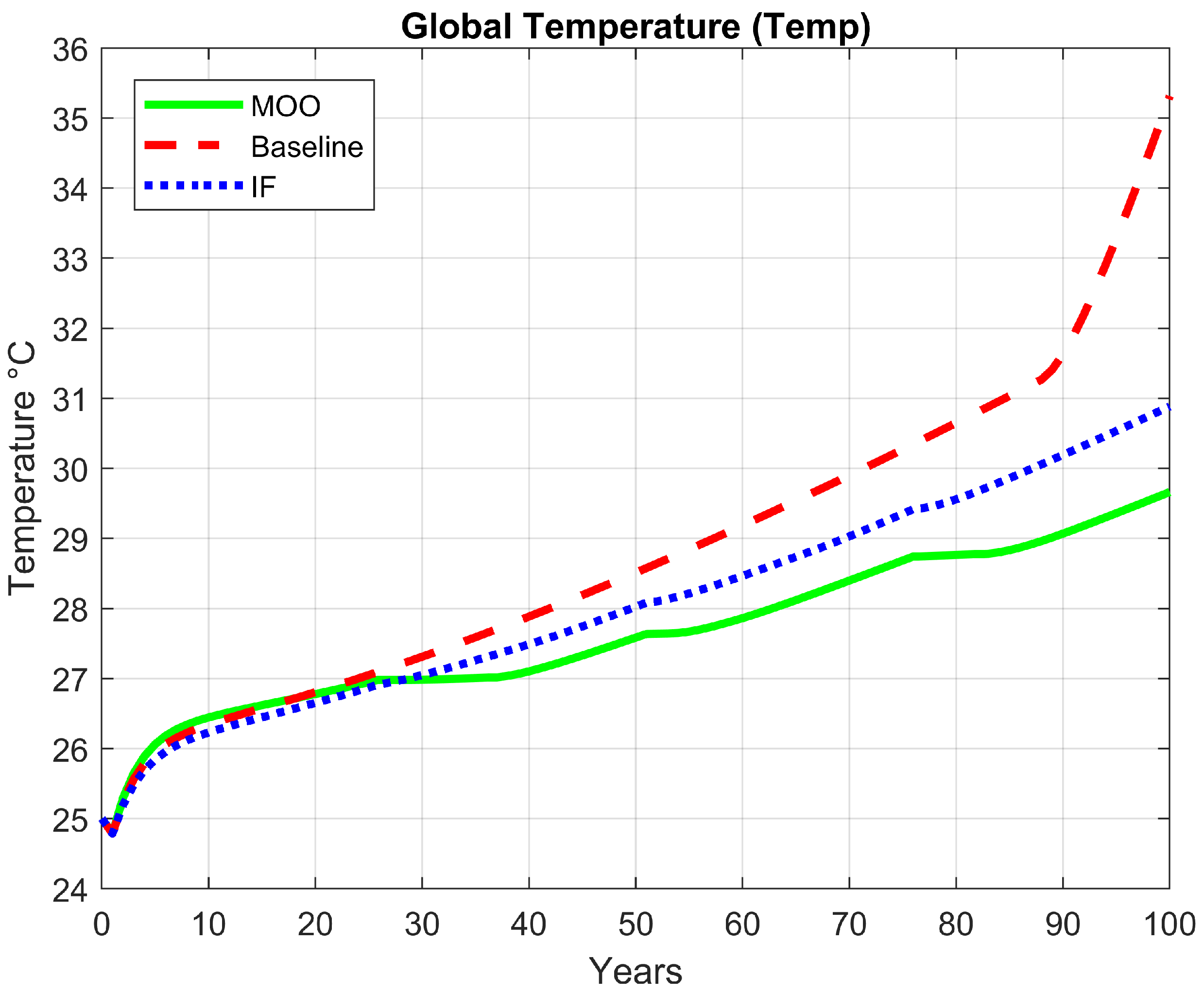

Figure 9 illustrates the temporal evolution of the global temperature (Temp) over a 100-year simulation horizon for the baseline model, the FI-based optimization, and the MOO approach. As in previous figures, the red dashed line represents the unoptimized baseline scenario, the blue dotted line corresponds to the FI-based optimization, and the green solid line shows the MOO results. Both optimization frameworks effectively reduce the global temperature trajectory compared to the baseline, demonstrating their capacity to mitigate the long-term warming trend of the system. However, the magnitude of the reduction varies between approaches. Under the FI-based optimization, the final temperature decreases by approximately 11.4%, falling from 35 °C in the baseline to around 31 °C. The MOO achieves an even greater reduction of 15%, with the final temperature reaching 29.7 °C.

Figure 9.

Comparative trajectory of global temperature under different optimization frameworks.

These results show that while the FI-based approach successfully prevented the abrupt temperature escalation observed in the last decade of the baseline simulation—an outcome associated with potential systemic collapse—the MOO delivers superior performance. By explicitly balancing environmental, economic, and social objectives, the MOO framework achieves a more substantial and stable reduction in temperature.

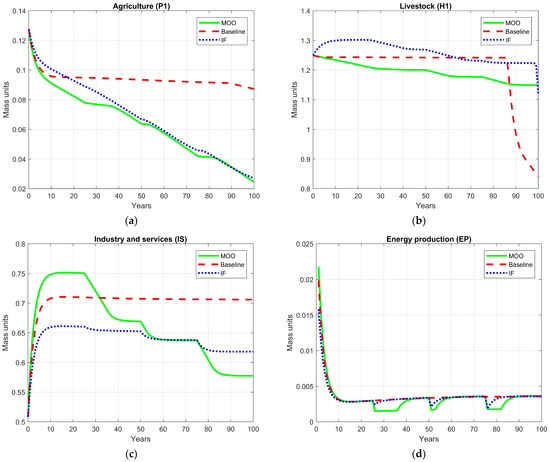

3.3.2. Economic Trajectory (Productive Sectors)

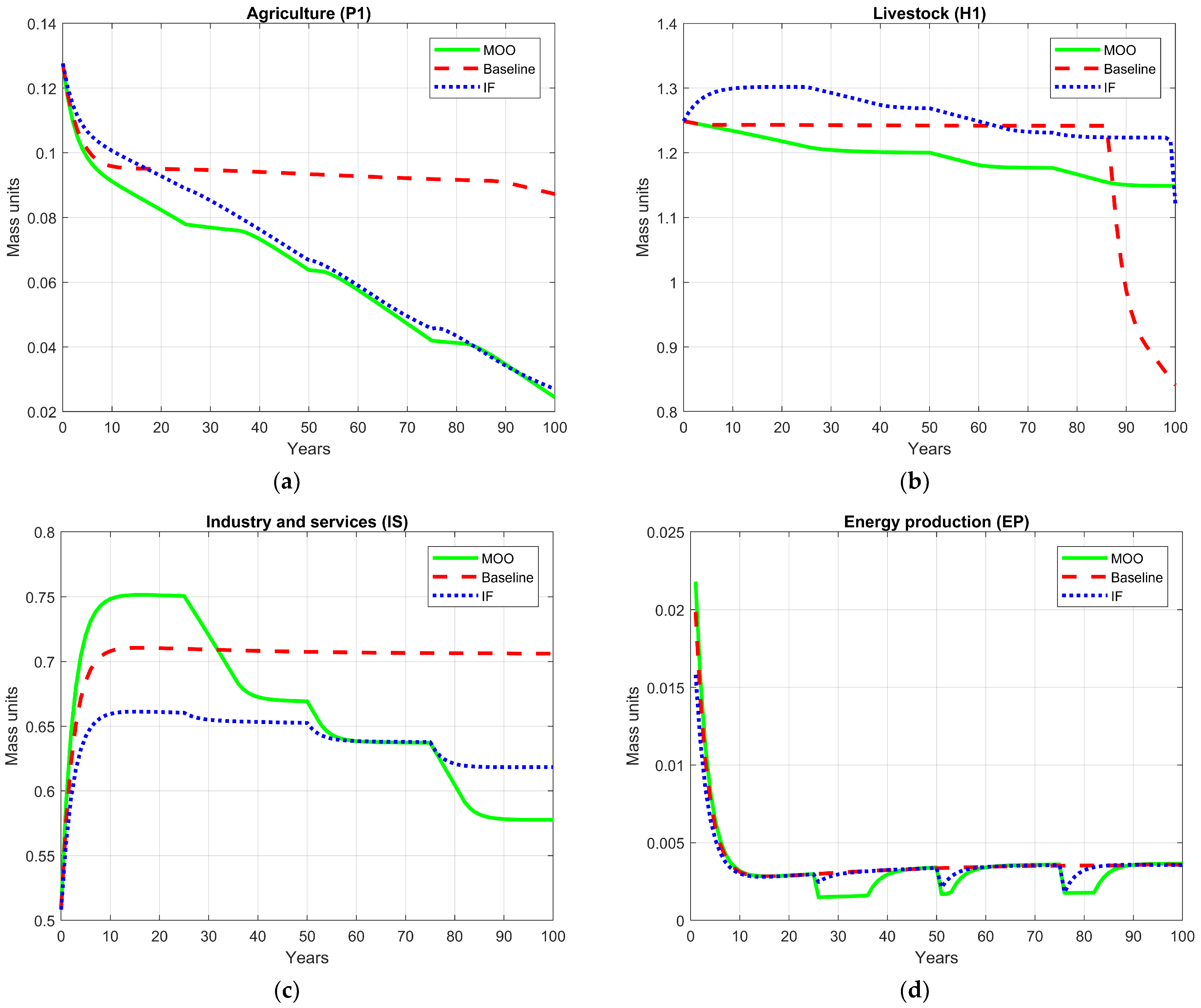

In this section, the temporal evolution of the main productive sectors of the system (agriculture P1, livestock H1, industry and services IS, and energy production EP) over a 100-year simulation horizon is presented in Figure 10. These variables collectively capture the economic dimension of the model, reflecting both productivity and structural resilience under different optimization schemes.

Figure 10.

Comparative trajectories of productive sectors under different optimization frameworks: (a) agriculture (P1); (b) livestock (H1); (c) industrial and services (IS); (d) energy production.

For the agricultural sector (P1) (Figure 10a), the MOO framework shows an initially sharp decline during the first 25 years, followed by stabilization and mild fluctuations. In contrast, the FI-based optimization maintains a smoother, more gradual reduction, while the baseline model remains nearly constant. This decline should not be interpreted as a weakening of agricultural performance but as a systemic adjustment that reduces pressure on ecological resources. Unlike the industrial sector, P1 is not directly regulated through the resource requirement coefficient; instead, its behavior is governed by the trophic and eco-physiological processes embedded in the model, particularly the temperature-dependent regeneration term gRPP1, demand-driven flows (P1HH and P1H1), and the interaction with the human subsystem. Under FI optimization, the reduction in P1 arises from the system’s intrinsic tendency to suppress fluctuations and maintain dynamic order, thereby moderating consumption and preventing ecological overshooting. In the MOO solution, early reductions in agricultural intensity operate as a deliberate trade-off to curb the emissions associated with land use and to alleviate stress on the resource pool (RP), while stability in later decades reflects improved balance between regeneration (RPP1) and demand. Therefore, the decline in P1 can be interpreted as a shift toward a more efficient, ecologically coherent mode of agricultural production rather than a contraction in system capacity, ultimately enhancing the resilience of the socio-ecological system.

The livestock sector (H1) (Figure 10b) exhibits a markedly different dynamic. In the baseline scenario, production levels remain relatively stable until an abrupt collapse occurs near the end of the simulation, reflecting the long-term sensitivity of herbivore dynamics to accumulate environmental stress and resource scarcity. The FI-based optimization mitigates this decline, maintaining a moderate and stable production level. However, the MOO scenario achieves the most robust and controlled performance, progressively reducing production intensity in the early stages to prevent overexploitation while preserving economic and ecological viability.

Figure 10c presents the performance for industry and services (IS). Although the model does not compute total factor productivity directly, the decline in IS is consistent with sustained reductions in the resource requirement coefficient (λ). Because λ represents the biophysical inputs required per unit of production, decreases of 6–10% indicate that lower production levels can still satisfy system demand while reducing environmental pressure. This pattern may be interpreted as a shift driven by improved conversion efficiency rather than economic contraction. In the FI-based optimization, this decrease reflects the model’s intrinsic tendency to dampen fluctuations and preserve structural coherence by preventing resource overuse and energy overshooting. Conversely, the MOO identifies the industrial sector as one of the main contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and, therefore, deliberately reduces its production intensity to achieve broader environmental and social benefits. In both cases, the lower industrial output corresponds to a transition toward a more efficient, less resource-intensive economy, aligning economic activity with ecological boundaries while sustaining long-term system resilience.

Finally, in the case of the Energy Resource Pool (ERP) (Figure 10d), both optimization frameworks exhibit trajectories that are closely aligned with the baseline trajectory. This behavior indicates that the optimizations do not significantly alter the dynamics of finite energy reserves, which remain largely governed by the balance between extraction and consumption. Because the ERP is not a direct decision variable, but a dependent state determined by the energy demand of production sectors, its stability reflects the fact that ERP dynamics are predominantly governed by endogenous energy-use constraints rather than direct policy intervention. The similarity across scenarios, therefore, suggests that both the FI and MOO frameworks achieve sustainable energy use without increasing depletion pressure.

Taken together, these results show that both optimization frameworks drive the economic subsystems toward a more sustainable, resource-efficient configuration, albeit through distinct adjustment mechanisms. FI-based optimization promotes long-term structural stability by smoothing production fluctuations and preserving systemic coherence. In contrast, the MOO implements an adaptive transition strategy, introducing early corrective reductions in production intensity, particularly in the agricultural and industrial sectors, to achieve rapid environmental improvements and long-term socio-economic balance. Despite their different pathways, both approaches successfully prevent systemic collapse, maintain energy balance, and promote a coordinated redistribution of productive capacity across sectors.

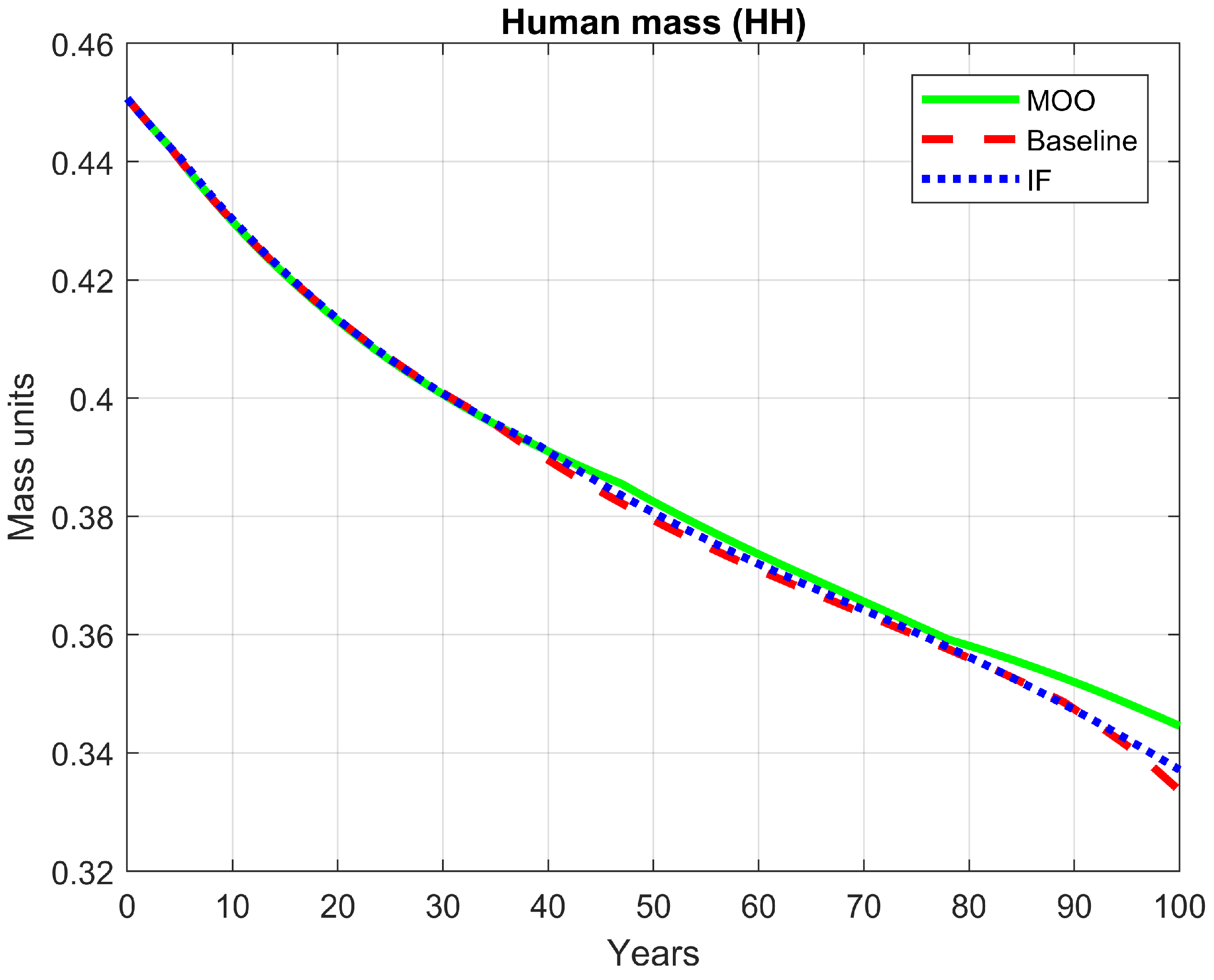

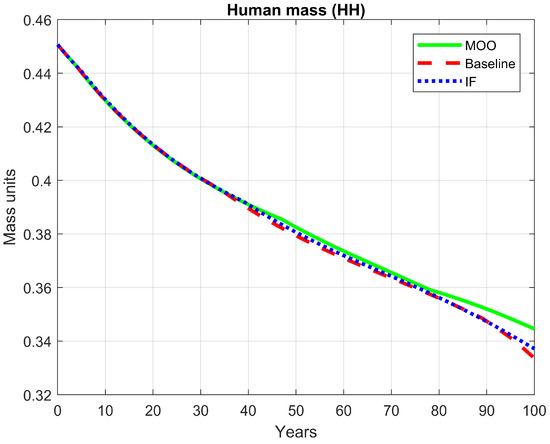

3.3.3. Social Trajectory (Human Mass)

Figure 11 shows the temporal evolution of total human mass (HH) over the 100-year simulation horizon. All three scenarios exhibit a gradual decline throughout the simulation, reflecting the cumulative impact of resource depletion and environmental stress on the human subsystem. However, notable differences emerge between optimization frameworks. The MOO maintains higher HH values during the entire simulation compared to both the baseline and the FI-based model, indicating that MOO strategies provide more favorable conditions for sustaining human biomass, driven by early adjustments in wages, prices, and resource efficiency. In contrast, the FI-based optimization closely follows the baseline trajectory, showing a slightly smoother and more stable decline but with lower mass values than MOO, indicating that FI emphasizes structural order and system stability rather than maximizing human welfare directly.

Figure 11.

Comparative trajectory of human mass under different optimization frameworks.

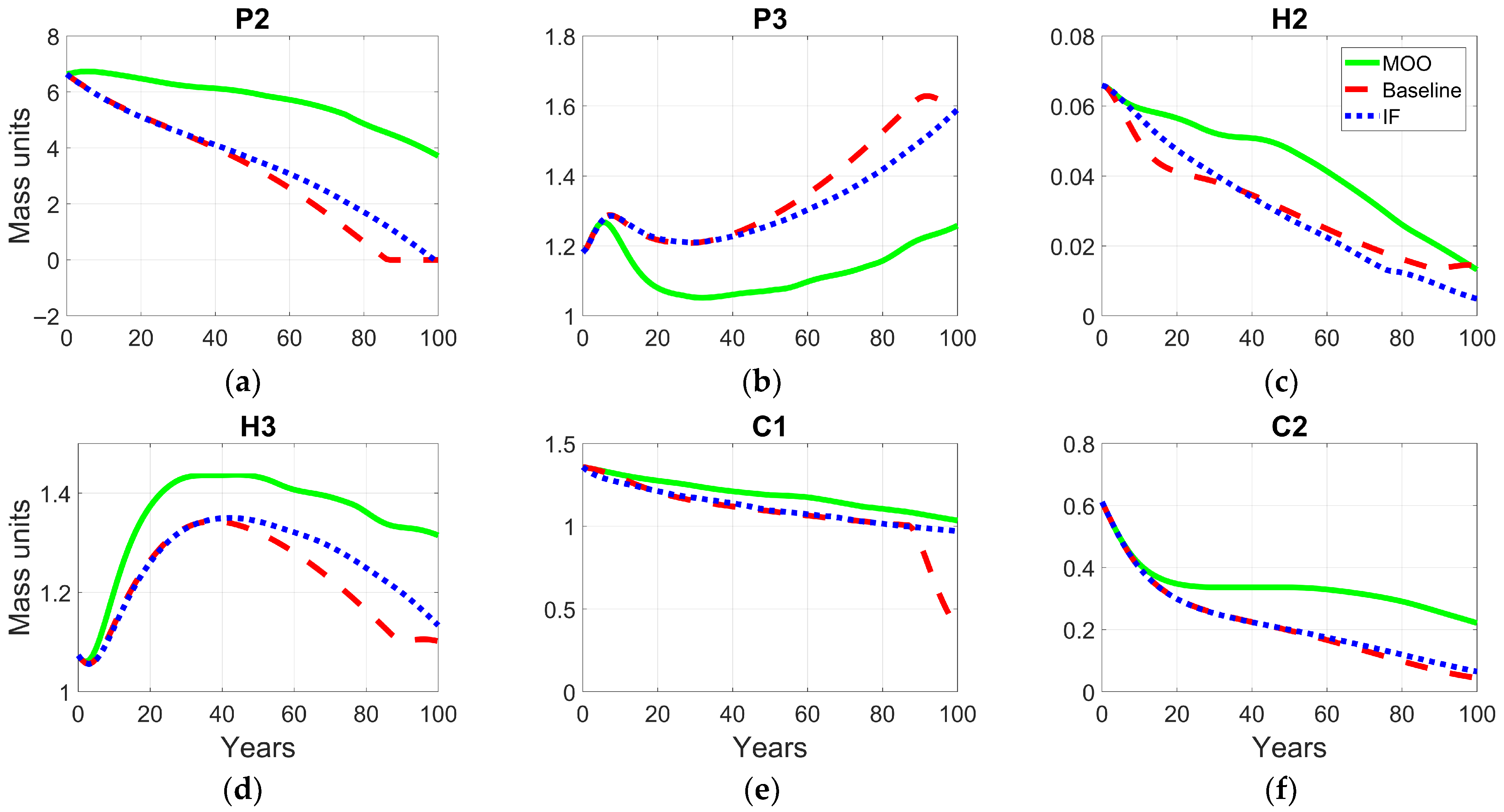

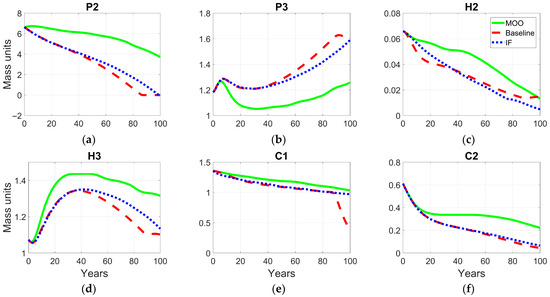

3.3.4. Ecological Trajectory (Biotic Compartments)

Figure 12 summarizes the evolution of the main biotic compartments of the ecological subsystem—plants accessible (P2) and inaccessible (P3) to humans (Figure 12a,b), herbivores (H2 and H3) (Figure 12c,d), and carnivores (C1, C2) (Figure 12e,f) over the 100-year simulation horizon. Together, these trajectories illustrate the structural responses of the trophic network to both optimization frameworks. Overall, the ecological trajectories demonstrate that both FI and MOO effectively stabilize the biophysical foundations of the system, delaying or preventing the imminent collapses observed in the baseline scenario. The FI-based optimization prioritizes structural equilibrium and resilience, damping fluctuations across trophic levels and maintaining energy balance throughout the simulation. In contrast, the MOO framework promotes adaptive reorganization, leading to higher overall biomass and sustained coexistence among ecological compartments. Both optimization frameworks mitigate the collapse observed in the baseline scenario, stabilizing trophic interactions and supporting coexistence across ecological compartments, underscoring the model’s capacity to capture the emergent stabilization of coupled ecological and socio-economic processes under policy-oriented decisions.

Figure 12.

Comparative trajectories of biotic compartments under different optimization frameworks: (a) accessible wild plants (P2); (b) inaccessible wild plants (P3); (c) accessible wild herbivores (H2); (d) inaccessible wild herbivores (H3); (e) wild carnivores interacting with humans (C1); (f) wild carnivores without human interaction (C2).

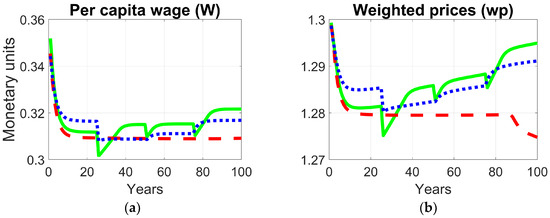

3.3.5. Socio-Economic Trajectory (Coupled Economic–Social Indicators)

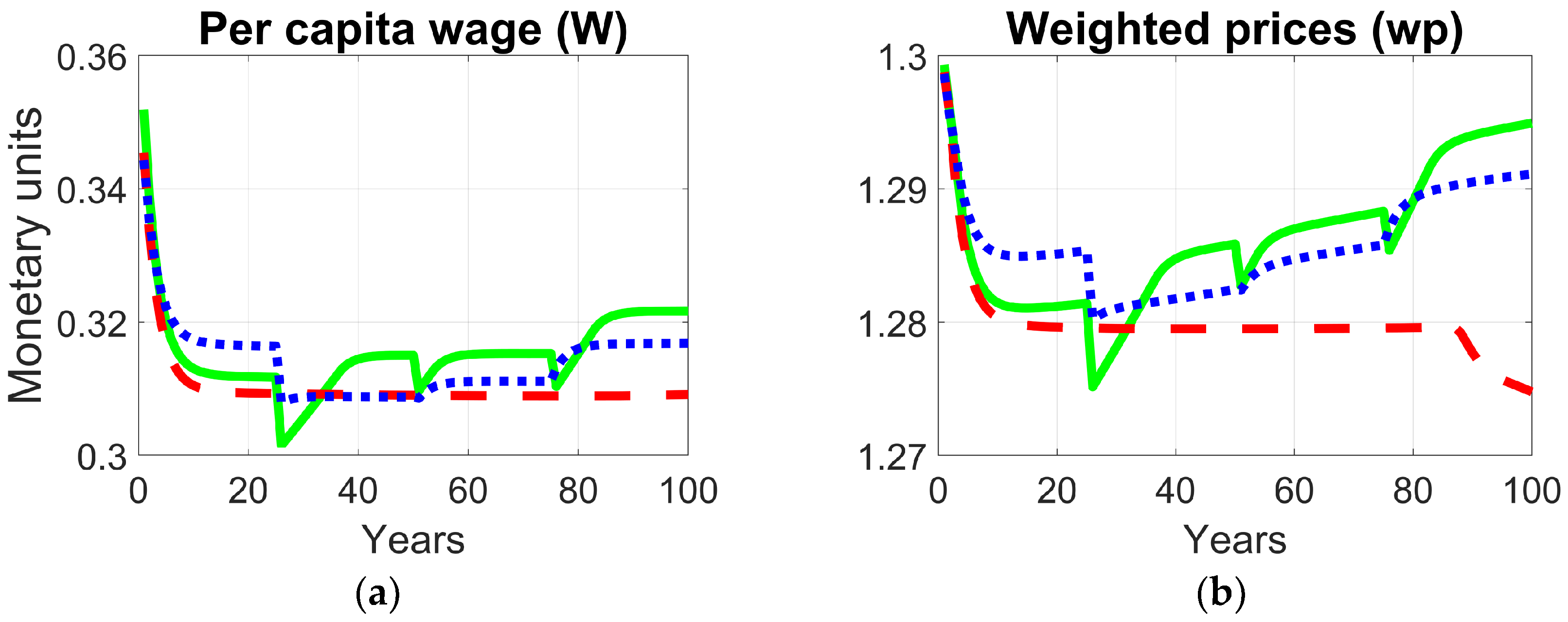

Figure 13 presents the joint evolution of per capita wages and the average price of goods across the 100-year simulation period. These variables serve as integrative indicators linking the economic and social dimensions of the system, reflecting how resource allocation and productivity adjustments under each optimization framework influence human welfare and market stability. Although both optimization frameworks display similar trends, a notable pattern emerges: per capita wages remain slightly above the baseline, showing small but consistent increases, whereas average prices exhibit a more pronounced upward trend. This divergence reflects a controlled reduction in purchasing power, which acts as a systemic stabilizing mechanism moderating excessive consumption and production growth. By allowing prices to rise marginally faster than wages, the model curbs excessive consumption and production demand, thus alleviating environmental pressure and maintaining macroeconomic balance. In this sense, the observed reduction in purchasing power represents a trade-off between short-term material welfare and long-term socio-environmental stability, aligning with the principles of sustainable economic transition.

Figure 13.

Comparative trajectories of socio-economic indicators under different optimization frameworks: (a) per capita wages (W); (b) weighted prices.

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that both the FI and MOO frameworks shift the SES model away from collapse and toward stable, sustainable trajectories. Each framework achieves sustainability through distinct mechanisms. The FI-based optimization promotes stability and structural order, minimizing variability and maintaining equilibrium across system components, while the MOO approach pursues adaptive resource redistribution that explicitly balances environmental, social, and economic objectives. These findings confirm that both paradigms are viable pathways to sustainability, one emphasizing resilience through stability, the other efficiency through adaptation [39,48].

Quantitatively, the optimizations achieved 11–15% reductions in global temperature relative to the baseline, with MOO yielding the lowest terminal value. This improvement stems from early, targeted adjustments in key decision variables, particularly agricultural and industrial prices, wages, and the resource-use coefficient (λ), which collectively enhanced energy efficiency and moderated emissions without compromising social welfare. These results align with previous studies showing that Pareto-efficient policy portfolios can simultaneously improve environmental outcomes and socio-economic stability when objectives are jointly optimized [49,50].

At the sectoral level, the apparent decline in agricultural (P1) and industrial (IS) output under both optimization frameworks does not represent economic contraction; rather, it reflects the structural rebalancing toward more-efficient and less-resource-intensive production patterns. The FI approach reduces oscillations and stabilizes production through conservative energy allocation, while MOO lowers production intensity in the short term to prevent overexploitation and to sustain long-term system viability. This mirrors empirical evidence showing that effective climate policies combine price-based instruments (e.g., carbon taxes) with regulatory or innovation-oriented measures that promote efficiency-oriented adjustments rather than output expansion [51,52].

The coupled evolution of wages and prices further reflects the systemic trade-offs inherent to sustainability transitions. In both optimization scenarios, average prices rise slightly faster than wages, implying a minor reduction in purchasing power. This dynamic functions as a stabilizing mechanism that moderates consumption and production pressures, aligning with empirical evidence that moderate price adjustments can drive emission reductions while maintaining overall welfare when paired with compensatory measures such as revenue recycling [53,54]. This behavior captures a plausible socio-environmental compromise in which modest short-term losses in purchasing power contribute to improved long-term ecological and macroeconomic stability.

The robustness of the optimization results is supported by the consistency of qualitative trends across multiple sustainability indicators—including temperature stabilization, biomass levels, sectoral outputs, and resource-use efficiency. Moreover, these patterns remain stable under small perturbations in key model parameters, as suggested by the sensitivity analysis, indicating that the system’s response is not overly dependent on finely tuned assumptions.

Regarding equity implications, even the moderate decline in purchasing power projected under both optimization strategies may provoke resistance among stakeholders, particularly low-income households and politically influential sectors sensitive to production costs. This response aligns with empirical evidence showing that sustainability transitions often face social and political pushback when perceived as imposing short-term economic burdens. Consequently, effective policy implementation may require compensatory measures—such as targeted subsidies, revenue recycling, or phased pricing adjustments—to maintain public support and safeguard distributional equity.

The comparison between FI and MOO also highlights their complementarity. FI proves most effective for maintaining systemic coherence and preventing abrupt regime shifts, consistent with its established use as an early-warning measure of resilience loss [48]. Conversely, MOO provides decision-makers with a transparent framework to explore multi-dimensional trade-offs and identify compromise solutions, particularly through the Ideal Point Method, which minimizes the distance to single-objective optima [39].

Within the broader SES literature, these findings demonstrate that effective policy design must explicitly connect human decisions with ecological feedback. This is achieved by allowing decision variables, such as wages, prices, and productivity factors, to propagate through trophic, economic, and atmospheric linkages, shaping global system trajectories. The introduction of temporal and magnitude constraints (25-year periods and ±10% bounds) enhances policy realism, reflecting the gradual and bounded nature of actual decision processes [55,56].

Despite these promising results, translating optimization-based sustainability strategies into real-world policy faces substantial practical and institutional barriers. Resistance to change from key stakeholders, such as industrial sectors, political actors, and citizens, can slow or obstruct policy adoption. Likewise, institutional inertia, including institutional fragmentation and limited administrative coordination, often undermines the continuity and coherence of sustainability efforts [56,57]. Addressing these challenges requires an understanding that the transition toward sustainability is as much a governance and social transformation problem as it is a technical one [58].

Addressing these barriers requires complementing quantitative approaches with participatory governance strategies that enhance legitimacy, trust, and transparency. Effective implementation depends on public awareness, economic incentives that reward sustainable practices, and accountability mechanisms enabling citizens to monitor progress. These measures have proven essential in empirical studies of climate governance and energy transitions, which show that policy effectiveness increases when stakeholders are engaged early and when feedback between public perception and policy adjustment is institutionalized [51,52,53].

Sustainable transformation requires not only technical optimization but also collective action and institutional innovation. Integrating participatory governance frameworks with formal decision-support models can bridge the gap between theoretical sustainability and actionable policy. Such integration would enable societies to navigate the complex trade-offs between growth, equity, and environmental integrity, thereby supporting transitions toward resilient and equitable futures.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating FI and MOO within a compartmental model of human ecosystems provides a robust quantitative framework for analyzing and designing sustainable policy strategies. Both approaches successfully prevent the long-term collapse observed in the baseline and guide the system toward more balanced environmental, social, and economic trajectories. Rather than reiterating specific numerical outcomes, the key insight is that optimization transforms system behavior through two distinct mechanisms: FI promotes stability by damping fluctuations and preserving structural coherence, while MOO reshapes system trajectories by explicitly managing trade-offs among competing objectives.

From a comparative perspective, the MOO strategy delivers the most favorable overall performance, producing greater environmental gains and improved human–system stability while maintaining acceptable economic functioning. FI, in contrast, enhances predictability and resilience by smoothing resource flows and reducing the likelihood of overshooting. Together, these results show that sustainability can be achieved either through conservative stability or adaptive reallocation, depending on policy priorities and contextual constraints.

Building on these insights, we derive a set of phased, actionable recommendations: (i) Near-term (0–20 years)—prioritize reducing industrial emission intensity and improving resource-use efficiency to avoid early-stage overshooting. (ii) Medium-term (20–50 years)—adjust agricultural and energy-conversion dynamics to maintain ecological integrity and reduce stress on the resource pool. (iii) Long-term (50+ years)—stabilize demographic and consumption patterns to prevent renewed system instability and reinforce socio-ecological resilience. These recommendations translate the optimization trajectories into decision-relevant strategies that can guide sustainable planning over different temporal horizons.

Despite its contributions, the framework remains limited by aggregated parameters, simplified feedback, and fixed temporal resolution. Future research should incorporate empirical calibration, stochastic dynamics, and regional disaggregation to improve predictive accuracy and enhance policy relevance.

Overall, this study demonstrates that human–ecosystem systems can be steered toward resilient and sustainable configurations when optimization and information-theoretic tools are systematically integrated into quantitative policy analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting materials are available online: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/world6040168/s1, Figure S1. Normalized one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis for environmental, economic, and social indicators. Figure S2. Comparison of parameter influence across sustainability dimensions. Table S1. Complete OAT sensitivity dataset (Δ ±5%) for all model parameters. Table S2. Baseline parameter set used in the socio-ecological system (SES) model. All supplementary figures and tables (Figures S1–S2 and Tables S1–S2) are included within File S1. File S1. Sensitivity Analysis Report (PDF). Contains Figures S1–S2, Tables S1–S2, extended methodological details, full OAT results, and explanatory notes. Code S1. MATLAB Source Code. All scripts required to run the SES model (Matlab R2017b), Fisher Information optimization, and multi-objective optimization are openly available at: https://github.com/TenochRdz/Multi-Objetive-vs-FI-based-Optimization (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.R.-G.; methodology, P.T.R.-G., A.O.-C. and S.A.T.-O.; software, P.T.R.-G. and H.A.O.-G.; validation, P.T.R.-G., E.R.-B. and H.A.O.-G.; investigation, A.O.-C. and S.A.T.-O.; resources, P.T.R.-G.; data curation, P.T.R.-G., S.A.T.-O. and A.O.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.-C.; writing—review and editing, P.T.R.-G.; visualization, P.T.R.-G.; supervision, P.T.R.-G., H.A.O.-G. and E.R.-B.; project administration, P.T.R.-G.; funding acquisition, P.T.R.-G. and E.R.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Mexican Secretary of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI), project number CF-2023-I-193, and the program Investigadoras e Investigadores por México), project number 534-2018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the administrative and financial support provided by SECIHTI and TecNM/Instituto Tecnológico de Aguascalientes. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-assisted tools (ChatGPT (GPT-5), OpenAI, 2025) for the purposes of improving the English grammar and readability of the manuscript, under the supervision of the corresponding author. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. No AI tools were used for the modeling, data generation, analysis, or interpretation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, J.; Dietz, T.; Carpenter, S.R.; Alberti, M.; Folke, C.; Moran, E.; Pell, A.N.; Deadman, P.; Kratz, T.; Lubchenco, J.; et al. Complexity of Coupled Human and Natural Systems. Science 2007, 317, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, A.J. Collapse. How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Jared Diamond. New York: Viking, 2004. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 499–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Home—Global Footprint Network. Available online: https://www.footprintnetwork.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- IPCC. Framing and Context. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 49–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Land Outlook 2|UNCCD. Available online: https://www.unccd.int/resources/global-land-outlook/glo2 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Stewart, J.B. Book Review: Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Rev. Black Polit. Econ. 1991, 20, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Full Report|OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/a-systemic-recovery_62830370-en/full-report.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cairney, P.; Oliver, K. Evidence-Based Policymaking Is Not like Evidence-Based Medicine, so How Far Should You Go to Bridge the Divide between Evidence and Policy? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicanor, P.; De La Cruz, A.; César, U.; Trujillo -Perú, V. Implementación de Políticas Públicas y Desarrollo Sostenible En Perú: Una Revisión Sistemática de Prácticas y Resultados: Implementation of Public Policies and Sustainable Development in Peru: A Systematic Review of Practices and Outcomes. LATAM Rev. Latinoam. De Cienc. Soc. Y Humanidades 2024, 5, 2171–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamplona, F. Sustentabilidad y Políticas Públicas. Gac. Ecológica 2000, 56, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- La Agenda para el Desarrollo Sostenible—Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cabezas, H.; Fath, B.D. Towards a Theory of Sustainable Systems. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2002, 197, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindyck, R.S. The Use and Misuse of Models for Climate Policy. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 11, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyant, J. Some Contributions of Integrated Assessment Models of Global Climate Change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 11, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Brutschin, E.; Baum, C.M.; Sovacool, B.K. Expert Perspectives on Incorporating Justice Considerations into Integrated Assessment Modelling. npj Clim. Action 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, M.; Kedward, K.; Dunz, N. Assessing Integrated Assessment Models for Building Global Nature-Economy Scenarios. Banque de France Working Paper, No. 959. 2024. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/bfr/banfra/959.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Malik, A.; Schaeffer, R. Integrated Assessment Modelling and Input-Output Analysis. Econ. Syst. Res. 2024, 36, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehfest, E.; van Vuuren, D.; Bouwman, L.; Kram, T. Integrated Assessment of Global Environmental Change with IMAGE 3.0: Model Description and Policy Applications; Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL): Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King, C.W. An Integrated Biophysical and Economic Modeling Framework for Long-Term Sustainability Analysis: The HARMONEY Model. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töpper, J.P.; Hoeks, S.; Hartig, F.; Kolstad, A.; Tucker, M.A.; Bartlett, J.; Bærum, K.M.; Chipperfield, J.; Harfoot, M.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; et al. Advancing General Ecosystem Models (GEMs): Towards a Mechanistic Understanding of the Biosphere in the Light of the Anthropocene. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2025, 6, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinerchia, M.; Fiorentino, F.; Colloca, F.; Cucco, A.; Garofalo, G.; Perilli, A.; Quattrocchi, G.; Fulton, E.A. Atlantis End-to-End Modeling to Explore Ecosystem Dynamics in the Strait of Sicily, Central Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 183, 106237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; Jung, J.; Hwang, G.; Moon, J.; Kwon, H.H.; Cha, Y.K. Modeling Ecosystem-Wide Responses to Environmental Stressors: A Multi-Trophic Hierarchical Bayesian Network Approach. J. Environ. Manage 2025, 391, 126480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sven Erik, J.; Fath, B.D. Fundamentals of Ecological Modelling: Applications in Environmental Management and Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Jin, G. Heterogeneity of urban‒rural responses to multigoal policy from an efficiency perspective: An empirical study in China. Habitat. Int. 2025, 158, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Deng, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. How does digitalization affect carbon emissions in animal husbandry? A new evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 214, 108040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, Y.; Diwekar, U.; Cabezas, H. Optimal Control Theory for Sustainable Environmental Management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5322–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, Y.; Diwekar, U.; Cabezas, H.; Williamson, J. Is Sustainability Achievable? Exploring the Limits of Sustainability with Model Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 6710–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, R.; Diwekar, U.; Benavides, P.T.; Yenkie, K.M.; Cabezas, H. Maximizing Sustainability of Ecosystem Model through Socioeconomic Policies Derived from Multivariable Optimal Control Theory. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, P.T.; Rico-Ramirez, V.; Rico-Martinez, R.; Diwekar, U.M. Sustainability Assessment of an Integrated Economic-Ecologic-Social Model under Time-Dependent Uncertainties. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2017, 40, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisal, A.; Diwekar, U.; Hanumante, N.; Shastri, Y.; Cabezas, H.; Rico Ramirez, V.; Rodríguez-González, P.T. Evaluation of Global Techno-Socio-Economic Policies for the FEW Nexus with an Optimal Control Based Approach. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 948443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumante, N.; Shastri, Y.; Nisal, A.; Diwekar, U.; Cabezas, H. Water Stress-Based Price for Global Sustainability: A Study Using Generalized Global Sustainability Model (GGSM). Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello Coello, C.A. Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization: A Historical View of the Field. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2006, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseri, H.; Iseri, F.; El-Halwagi, M.; Iakovou, E.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. A Multi-Objective Decision-Making Framework for Renewable Energy Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 166, 150789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhou, G.; Qiao, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Towards the Energy Transition:Multi-Objective Optimization of China’s Provincial Production Capacity of Coal. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 518, 145862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Solomatine, D.; Dong, Z. Robust Multi-Objective Optimization under Multiple Uncertainties Using the CM-ROPAR Approach: Case Study of Water Resources Allocation in the Huaihe River Basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 3739–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization of Building Envelope Retrofits Considering Future Climate Scenarios: An Integrated Approach Using Machine Learning and Climate Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chouinard, L.E.; Power, G.J.; Conciatori, D.; Sasai, K.; Bah, A.S. Multi-Objective Optimization for the Sustainability of Infrastructure Projects under the Influence of Climate Change. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2023, 8, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Chen, L.; Feng, H.; Peng, Z.; Long, Q. Sustainable and Robust Route Planning Scheme for Smart City Public Transport Based on Multi-Objective Optimization: Digital Twin Model. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 65, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Escoto, J.N.; Olivares-Benitez, E.; Nucamendi-Guillén, S.; Drzymalski, J. A Multi-Objective Sustainable Closed-Loop Supply Chain Network Problem with Hybrid Facilities. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2025, 32, 3497–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, G.H.; He, Y.; Pakdel, S.H. Multi-Objective Green Closed-Loop Supply Chain Management with Bundling Strategy, Perishable Products, and Quality Deterioration. Mathematics 2024, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Ortiz, S.A.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, P.T.; Tovar-Gómez, R. Modeling the Impact of Global Warming on Ecosystem Dynamics: A Compartmental Approach to Sustainability. World 2024, 5, 1077–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, P.T.; Rico-Martinez, R.; Rico-Ramirez, V. Effect of Feedback Loops on the Sustainability and Resilience of Human-Ecosystems. Ecol. Modell. 2020, 426, 109018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, T.; Cabezas, H. Evaluating the Sustainability of a Regional System Using Fisher Information in the San Luis Basin, Colorado. J. Environ. Manage 2012, 94, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mejía, A.; Vance, L.; Eason, T.; Cabezas, H. Recent Developments in the Application of Fisher Information to Sustainable Environmental Management. Assess. Meas. Environ. Impact Sustain. 2015, 1, 25–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, A.E.; Ho, Y.-C.; Siouris, G.M. Applied Optimal Control: Optimization, Estimation, and Control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 2008, 9, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, E.; Cabezas, H.; Mayer, A.L. Detecting Dynamic System Regime Boundaries with Fisher Information: The Case of Ecosystems. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushaega, M.M.; Moshebah, O.Y.; Hamzi, A.; Alghamdi, S.Y. Multi-Objective Sustainability Optimization in Modern Supply Chain Networks: A Hybrid Approach with Federated Learning and Graph Neural Networks. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 115, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]