Abstract

This study investigates the challenges faced by small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) as they attempt to respond to decarbonization demands and expand into renewable-energy markets. Drawing on three waves of free-response surveys conducted between 2021 and 2024, and applying the KJ qualitative synthesis method, the analysis identifies multi-layered constraints across financial, technological, human resource, organizational, and institutional domains. The findings show that the central difficulty for SMEs lies in reconciling exploration—the pursuit of new technologies and business opportunities—with exploitation—the need to maintain and improve existing operations. External stakeholder pressure frequently accelerates this tension, compelling SMEs to initiate environmental actions even when internal capabilities remain insufficient. Based on the emergent patterns, the study develops an “Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix,” providing a practical framework for policymakers to design coordinated support measures. The study contributes to the integration of eco-innovation, absorptive capacity, and ambidextrous management theories and offers actionable insights for promoting sustainable SME transitions.

1. Introduction

Global pressures toward decarbonization have intensified the expectations placed on firms—particularly small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and incorporate eco-innovation into both processes and products. Government regulations, customer procurement requirements, and supply chain standards increasingly drive SMEs to adopt low-carbon strategies and participate in renewable-energy markets [1,2,3]. Although SMEs constitute a significant share of manufacturing employment and regional production capacity, their ability to absorb, adapt, and commercialize environmentally oriented innovations varies widely [3,4,5].

Recent empirical studies suggest that eco-innovation in SMEs is often triggered not by internal motivations—such as managerial commitment or strong in-house R&D capabilities—but rather by external stakeholder pressures, including customers, regulatory agencies, financial institutions, and local communities [2,3,5]. Such exogenous pressures can stimulate short-term participation in decarbonization markets [1,6], yet they often expose persistent structural weaknesses. Many SMEs lack the absorptive capacity required to interpret new technological expectations and convert them into sustainable innovation practices [7,8].

Organizational theories of absorptive capacity and ambidexterity posit that firms must balance exploitation (enhancing existing production processes) and exploration (pursuing new technologies and business models) to achieve long-term innovation [9,10,11,12]. For SMEs confronting decarbonization requirements, this balance becomes not merely an organizational choice but a strategic necessity. However, limited human, financial, and informational resources make it structurally difficult for SMEs to invest in renewable-energy technologies while maintaining stable operations.

The ambidexterity dilemma has been widely examined in large-firm contexts, but its manifestations in SMEs—particularly under decarbonization pressure—remain underexplored. This gap raises several questions:

- How do external stakeholder pressures interact with internal capability constraints when SMEs attempt eco-innovation?

- How do exploration and exploitation manifest in SMEs with limited resources?

- What types of support mechanisms enable SMEs to balance short-term operational demands with long-term environmental innovation?

- What mechanisms uniquely characterize SME responses to decarbonization relative to existing theoretical models?

This study addresses these questions using three waves of free-response surveys conducted between 2021 and 2024. Applying the KJ qualitative synthesis method [13], we systematically categorize organizational constraints, support needs, and behavioral patterns across SMEs transitioning toward renewable-energy markets and decarbonization management.

To situate this empirical analysis within the existing body of knowledge, the Section 2 develops a comprehensive theoretical framework. Drawing on eco-innovation theory, absorptive capacity, and organizational ambidexterity, the framework establishes the conceptual pathway linking stakeholder pressure, internal capabilities, and eco-innovation outcomes. This structure guides the interpretation of qualitative findings and motivates the development of an Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix for SME policy design.

2. Theoretical Framework

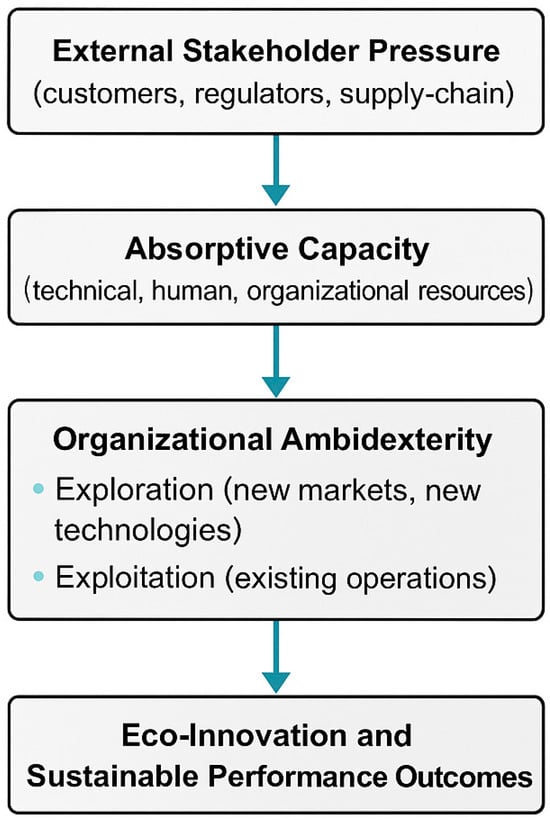

The transition toward a decarbonized industrial system places increasing pressure on small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) to incorporate environmental innovation into their business strategies. However, SMEs often operate under severe resource constraints that shape how they interpret and respond to external expectations. Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundations guiding the empirical analysis. Drawing on research in eco-innovation, absorptive capacity, and organizational ambidexterity, we propose an integrated conceptual pathway (Figure 1) that explains how external stakeholder pressure influences SME behavior through the development—or absence—of key organizational capabilities.

Figure 1.

Conceptual pathway illustrating how stakeholder pressure shapes SME absorptive capacity, which in turn conditions the emergence of ambidexterity and eco-innovation outcomes.

Figure 1 summarizes the theoretical pathway that motivates the empirical analysis. It integrates three bodies of literature—external stakeholder pressure, absorptive capacity, and organizational ambidexterity—and specifies the mediating role of absorptive capacity in shaping whether SMEs translate external decarbonization pressure into exploration or exploitation activities. This framework directly informs the coding structure of Tables in Section 4.

2.1. External Stakeholder Pressure and Eco-Innovation

A central premise in eco-innovation research is that environmental action within SMEs is often induced by external rather than internal motivations. Prior studies demonstrate that regulatory agencies, large-firm customers, industry associations, financial institutions, and local communities exert substantial pressure on SMEs to adopt low-carbon technologies and comply with environmental standards [1,6]. Such pressure can catalyze eco-innovation by creating economic incentives or compelling firms to meet procurement requirements. Yet, this process is rarely straightforward. SMEs may be pushed toward new technologies before they have developed sufficient knowledge or organizational readiness to absorb them.

In this study, external stakeholder pressure is conceptualized as an upstream driver that activates eco-innovation attempts but also exposes firms to capability gaps. As illustrated in Figure 1, this pressure serves as the initial trigger that conditions the development of absorptive capacity and, subsequently, ambidextrous behavior.

2.2. Absorptive Capacity as an Interpretive Capability

Absorptive capacity refers to an organization’s ability to acquire, assimilate, and apply external knowledge [7]. Within SMEs, this capacity is strongly influenced by the availability of technical expertise, learning routines, and organizational resources [8]. High absorptive capacity enables firms to transform external environmental requirements into actionable strategies—for example, by understanding decarbonization standards, evaluating new renewable-energy technologies, or identifying relevant certification schemes.

Conversely, limited absorptive capacity can prevent SMEs from translating external signals into coherent responses. Without adequate technical staff, learning structures, or managerial attention, SMEs may recognize the need to act but lack the internal mechanisms to move from awareness to implementation.

In our framework, absorptive capacity acts as a mediating capability: it determines whether external pressure results in meaningful exploration of eco-innovation options or whether firms become overwhelmed by unfamiliar demands.

2.3. Organizational Ambidexterity and Sustainability Transitions

Organizational ambidexterity—defined as the ability to simultaneously pursue exploration and exploitation [4]—has become a central concept in understanding how firms manage competing demands in dynamic environments. Exploration involves seeking new technologies, entering new markets, or experimenting with novel business models. Exploitation emphasizes improving existing operations, maintaining quality, and optimizing current production processes.

In large firms, ambidexterity can be achieved through structural separation or cross-functional integration. For SMEs, however, the pursuit of ambidexterity is much more constrained. Resource shortages, thin managerial capacity, and limited slack make it difficult to assign employees to new exploratory activities while sustaining normal operations [11].

In the context of decarbonization, this tension becomes particularly acute. Exploration requires investigating new energy technologies, engaging with partners in the renewable-energy sector, or developing eco-oriented products. Exploitation requires uninterrupted fulfillment of existing orders, maintenance of customer relationships, and cost-efficient production. As shown empirically later in Section 4, SMEs often find it structurally impossible to balance these objectives, leading to what this study conceptualizes as an externally induced ambidexterity dilemma: exploration is demanded by external actors, while exploitation remains essential for survival.

2.4. Integrated Conceptual Pathway: Linking Pressure, Capacity, and Ambidexterity

Figure 1 synthesizes these theoretical elements into a unified conceptual pathway. The diagram illustrates the sequential mechanisms through which external stakeholder pressure influences eco-innovation outcomes:

- External pressure initiates a need for environmental action.

- Absorptive capacity filters and interprets this pressure, shaping how SMEs understand technological and regulatory changes.

- Organizational ambidexterity becomes the behavioral outcome of this interaction, determining whether firms can engage in both exploration (new markets, new technologies) and exploitation (existing operations).

- These interactions, in turn, influence eco-innovation and sustainable performance outcomes.

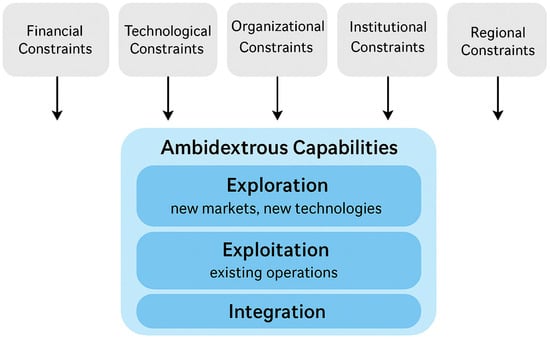

The framework thus positions absorptive capacity as a crucial antecedent capability and ambidexterity as the behavioral engine of eco-innovation. The conceptual map in Figure 2 extends this logic by showing how five empirically derived constraint domains—financial, technological, organizational, human resource, institutional, and regional—limit the emergence of exploration, exploitation, and integrative capabilities. Together, Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide the theoretical foundation for interpreting the qualitative findings and for developing the Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix advanced in the Discussion.

Figure 2.

Conceptual map illustrating how five challenge domains—financial, technological, organizational, institutional, and regional constraints—shape the exploration, exploitation, and integrative capabilities underpinning organizational ambidexterity in SMEs.

Figure 2 extends this framework by mapping the five empirically derived constraint domains to the three capability categories required for ambidexterity. This conceptual map serves as a bridge between the theoretical arguments in Section 2 and the empirical KJ Method categories, thereby linking Figure 1’s pathway with the Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix proposed in the Section 5.

2.5. Summary of Theoretical Propositions

Based on the synthesis of prior literature and the integrated conceptual model, this study advances the following propositions:

- P1. External stakeholder pressure is a primary driver of SME engagement in decarbonization and renewable-energy initiatives.

- P2. The degree to which SMEs can translate external pressure into eco-innovation depends on their absorptive capacity.

- P3. Limited resources make ambidextrous behavior structurally difficult for SMEs, particularly when exploration is externally imposed.

- P4. Eco-innovation in SMEs is most effectively supported through policy architectures that reinforce both exploration-oriented and exploitation-oriented capabilities.

These propositions inform the design of the empirical analysis and guide interpretation of the qualitative categories derived through the KJ Method.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This study draws on three waves of free-response surveys conducted between 2021 and 2024 targeting small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in Japan.

The first survey (2021) targeted 1000 SMEs in 13 prefectures and obtained 138 responses. Respondents were concentrated in metal products manufacturing, and many firms were small in scale, with limited capital and workforce size.

The second survey (2022–2023) targeted 700 firms in the same regions and obtained 90 responses. Compared to the first wave, respondents tended to have larger employee counts and greater exposure to diverse energy-related markets.

The third survey (2024–2025) expanded coverage to 17 prefectures and obtained 141 responses. Firms varied more widely in size, capital composition, and technological readiness.

These three waves provided the qualitative base for the KJ method analysis.

3.2. Questionnaire Content

Across the surveys, respondents were asked open-ended questions related to:

- Internal challenges in expanding sales and orders of renewable-energy–related equipment;

- Support measures required for renewable-energy market entry;

- Needs related to decarbonization management;

- Challenges in balancing existing and new businesses;

- Requests for public support programs.

The questions were intentionally broad to elicit unstructured, bottom-up insights into SME perceptions rather than impose predefined categories.

3.3. KJ Method Procedure

All free-text responses were analyzed using the KJ Method [13], a systematic qualitative technique designed to categorize unstructured information into meaningful clusters. The procedure consisted of the following steps:

- Extraction of unit statements (“opinion cards”)

All responses were segmented into discrete meaning units.

- 2.

- Independent coding by multiple researchers

Two coders extracted cards independently, followed by reconciliation meetings to ensure analytic consistency.

- 3.

- Cluster formation using inductive grouping

Cards were grouped based on semantic similarity without predetermined categories.

- 4.

- Labeling of clusters

Each cluster was assigned a descriptive category name.

- 5.

- Construction of hierarchical maps

Final diagrams were created to visualize relations among clusters.

- 6.

- Validation

Coding disagreements were resolved through discussion; saturation was confirmed when no new categories emerged.

Coding Reliability and Validation

Two researchers independently extracted and clustered all opinion cards. Coding discrepancies were discussed in reconciliation meetings until agreement was reached. Inter-coder agreement exceeded 85%, which is considered acceptable for qualitative thematic analysis. Coding saturation was confirmed in the final round, as no new categories emerged. To increase transparency for international audiences unfamiliar with the KJ method, Appendix A Table A1 presents anonymized examples of clustered opinion cards.

All qualitative analyses (card extraction, clustering, and category synthesis) were conducted using NVivo 14 for Mac (QSR International, San Jose, CA, USA) for data management and memoing. Visual mapping in the final clustering stage was performed manually using Miro (version 0.7.43). No automated text-coding functions were used; all categorizations relied on human interpretation consistent with the KJ Method.

3.4. Table Structure and Presentation

The following Tables in Section 4 summarize the categorical results derived from the KJ method across all relevant survey rounds.

4. Results

4.1. Internal Challenges in Expanding Sales and Orders of Renewable-Energy–Related Equipment

The analysis identified six core categories of internal challenges that SMEs face when expanding sales and orders of renewable-energy–related equipment. These categories emerged inductively from the KJ method and are summarized in Table 1, which is placed immediately below.

Table 1.

Internal Challenges in Expanding Sales and Orders of Renewable-Energy–Related Equipment (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

Consistent with the patterns summarized in Table 1, SMEs struggle most with market access, technological adaptation, financial risks, and human resource shortages. These categories constitute the structural core of internal barriers for renewable-energy market expansion.

4.2. Expected Support Measures for Renewable-Energy–Related Market Entry

The KJ method identified five categories of support required by SMEs for entering renewable-energy markets. These categories are derived from multiple clusters through the KJ method and are summarized in Table 2, which is placed immediately below.

Table 2.

Expected Support Measures for Renewable-Energy–Related Business Development (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

As shown in Table 2, SMEs prioritize financial and human resource support, followed by market development, information provision, and regional collaboration. These findings reveal that entering renewable-energy markets requires multi-layered support rather than isolated measures.

4.3. Required Support for Implementing Decarbonization Management

The analysis of free-response data identified six major categories of support required for decarbonization management. These categories are derived from multiple clusters through the KJ method and are summarized in Table 3, which is placed immediately below.

Table 3.

Required Support Measures for Decarbonization Management (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

As shown in Table 3, SMEs require a combination of financial incentives, technical expertise, human resource support, information clarity, market coordination, and regional institutional backing. These findings indicate that decarbonization management is not merely a technological issue but a complex capability-building challenge requiring multi-dimensional support structures.

4.4. Challenges in Implementing Decarbonization Management

Free-response data revealed six categories of challenges that SMEs encounter when attempting to implement decarbonization management. These categories are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Challenges in Implementing Decarbonization Management (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

Table 4 highlights that SMEs do not face a single bottleneck but a layered system of constraints. Even when financial burdens are partially alleviated, issues such as institutional opacity, technical difficulty, or lack of regional infrastructure persist. This suggests that decarbonization efforts require systemic and sustained forms of support, rather than one-off subsidies.

4.5. Challenges in Balancing Existing and New Businesses

The transition toward renewable-energy business and decarbonization requires SMEs to manage both existing operations and new exploratory activities. The KJ method identified six categories of challenges in achieving this balance. These categories are summarized in Table 5, which is placed immediately below.

Table 5.

Challenges in Balancing Existing and New Businesses (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

As shown in Table 5, SMEs face substantial tensions in resource allocation between existing and new business areas. These challenges reflect the ambidexterity dilemma—the fundamental difficulty of simultaneously pursuing exploration and exploitation, particularly under severe resource constraints.

4.6. Requests for Public Support in Balancing Existing and New Businesses

The analysis identified six key forms of public support requested by SMEs to balance existing operations with new low-carbon initiatives. The categories are summarized in Table 6, placed immediately below.

Table 6.

Requested Public Support for Balancing Existing and New Businesses (KJ Method Classification).

Interpretation

Table 6 shows that SMEs seek multi-dimensional and mutually reinforcing support. Notably, requests for institutional reform—such as simplified procedures or clear guidelines—are as frequent as financial support, indicating that administrative complexity is a major barrier to SME innovation.

5. Discussion

Figure 1 and Figure 2 synthesize the conceptual pathway through which stakeholder pressures shape SME absorptive capacity, impose exploration demands, and ultimately generate an externally induced ambidexterity dilemma. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 provide the qualitative evidence underpinning each mechanism, offering a granular picture of how these dynamics manifest in practice. Together, the figures articulate the theoretical logic while the tables demonstrate the empirical grounding of the argument. This integrated structure enables a theoretically informed and empirically substantiated interpretation of how SMEs navigate decarbonization and renewable-energy market transitions.

This study examined how small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in Japan respond to intensifying decarbonization pressures and attempt to participate in emerging renewable-energy markets. Drawing upon three rounds of free-response surveys and a systematic KJ method analysis, the findings reveal a multi-layered configuration of financial, technological, organizational, institutional, and regional barriers. These results illuminate not only the challenges that SMEs face but also the mechanisms through which external pressures interact with internal constraints to shape eco-innovation behavior.

5.1. Eco-Innovation in SMEs: Externally Induced and Internally Constrained

Across the three survey waves, SMEs consistently framed their engagement in decarbonization and renewable-energy activities as responses to external demands. These demands include customer expectations, emerging supply chain standards, and regulatory requirements—forces that have been widely documented as triggers of eco-innovation in resource-constrained firms [1,3,6]. However, Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 demonstrate that SMEs often lack the absorptive capacity necessary to interpret these external signals, translate them into actionable routines, and embed them in ongoing operations.

For example, respondents highlighted the need for technical assistance, accurate information, human resource development, and institutional clarity simply to initiate decarbonization management (Table 3). This pattern reflects a persistent “exposure gap”: external pressures rise more rapidly than internal capabilities can adapt. Rather than emerging from internal strategic commitment, SME eco-innovation is therefore primarily reactive—an adaptation to exogenous demands. Such reactivity increases short-term compliance but makes sustained eco-innovation trajectories more fragile.

These findings reinforce the argument that SME environmental behavior is shaped by the interplay between external stimuli and limited absorptive capacity, complicating efforts to establish stable eco-innovation routines.

5.2. The Ambidexterity Dilemma Under Resource Scarcity

Organizational ambidexterity requires firms to balance exploration—developing new technologies, markets, and business models—with exploitation—refining existing operations. While ambidexterity theory is well-established in large-firm contexts [4,10], its relevance to SMEs undergoing sustainability transitions has been underexplored.

This study reveals a form of ambidexterity that is both distinctive and structurally problematic for SMEs. First, exploitation dominates because maintaining existing operations consumes most available resources. Table 5 shows pervasive shortages of personnel, organizational systems, financial slack, and technological capability. Second, exploration is not internally generated but externally imposed. Many SMEs reported being pushed by customers or regulatory pressures to explore unfamiliar technologies or products, despite lacking the necessary resources or expertise.

Because exploration is externally forced while exploitation remains essential for survival, the two activities become structurally incompatible. Table 4 and Table 5 illustrate that SMEs do not possess the financial, informational, organizational, or technological foundations needed for ambidexterity to emerge organically.

This configuration constitutes an externally induced ambidexterity dilemma—a theoretical mechanism in which exploration demands arise from outside the firm, exceed internal absorptive capacity, and conflict with the resource requirements of existing business operations. This extends existing ambidexterity theory by demonstrating how external actors may impose exploration imperatives on capacity-constrained firms.

5.3. The Multi-Level Nature of Support Needs

SME requests for support—summarized in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 6—reveal that firms perceive eco-innovation not as a singular challenge but as a systemic capability-building process requiring intervention at multiple levels. SMEs require support in:

- financial and investment mechanisms,

- technical and expert assistance,

- human resource development,

- administrative simplification,

- market creation and business matching,

- regional collaboration and platform formation.

The consistency of these requests across survey waves suggests that decarbonization exposes deep structural limitations in SME resource bases. Notably, institutional and administrative burdens were cited as frequently as financial needs (Table 3 and Table 6), indicating that uncertainty and procedural complexity constitute major impediments to environmental transition.

These multi-level support needs highlight the necessity of moving beyond isolated subsidies or technology programs. Effective eco-innovation policy for SMEs must be conceived as an integrated support ecosystem that reinforces absorptive capacity, reduces uncertainty, and enables coordinated capability development.

5.4. Toward an Ambidextrous Eco-Innovation Support Framework

Building upon the empirical patterns across Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and the mechanisms depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2, this study proposes an Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix. This framework conceptualizes SME eco-innovation support as ambidextrous, consisting of:

- (1)

- Exploration-oriented support

- R&D subsidies and prototyping assistance

- technology scouting and expert consultation

- market development programs and business matching

- ESG finance and risk-sharing mechanisms

- (2)

- Exploitation-oriented support

- energy-efficiency upgrades

- process optimization and production support

- quality control system enhancements

- long-term financing for operational stability

- workforce retention and upskilling

- (3)

- Integrative institutional support

- administrative streamlining

- standardized decarbonization guidelines

- regional coordination platforms

- intermediary organizations facilitating knowledge transfer

This architecture directly addresses the structural challenges summarized in Table 1, Table 4, and Table 5 while enabling SMEs to pursue exploratory and exploitative activities in a balanced manner. It also bridges eco-innovation literature with absorptive capacity and ambidexterity theory, offering a coherent model tailored to the realities of resource-constrained SMEs.

5.5. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes three theoretical contributions:

- Identification of the exposure gap:

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 reveal a persistent mismatch between external environmental pressures and internal SME capability development.

- 2.

- Conceptualization of the externally induced ambidexterity dilemma:

Table 4 and Table 5 demonstrate that SMEs are structurally unable to balance exploration and exploitation when exploration is externally imposed.

- 3.

- Integration of eco-innovation, absorptive capacity, and ambidexterity in a unified framework:

The Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix (derived from Table 2, Table 3, and Table 6) offers a comprehensive theoretical model for understanding SME transitions under decarbonization pressure.

These contributions advance the literature by explaining how sustainability transitions unfold in capacity-constrained firms exposed to strong external drivers.

5.6. Practical and Policy Implications

The findings suggest that policymakers must design multi-dimensional, sequenced, and coordinated interventions rather than isolated subsidies. Key recommendations include:

- combining financial instruments with long-term technical support;

- reducing administrative complexity and clarifying institutional expectations;

- establishing regional clusters and intermediary organizations to address scale disadvantages;

- strengthening SME human resource development and cross-firm knowledge exchange;

- implementing risk-sharing schemes with financial institutions.

Operationalizing the Support Matrix requires targeted R&D programs, energy-efficiency incentives, ESG-aligned financing, multi-year advisory services, and standardized guidelines. These coordinated tools can reduce uncertainty, reinforce absorptive capacity, and enable SMEs to develop sustainable eco-innovation trajectories.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, the dataset covers manufacturing SMEs in selected prefectures, limiting generalizability across industries and regions. Second, qualitative methods do not allow for causal inference or quantification of effect sizes. Third, the study focuses on perceived needs and constraints, not on the outcomes of specific policy interventions.

Future research should develop quantitative indicators to test the mechanisms proposed in Figure 1 and Figure 2, evaluate the effectiveness of targeted support programs, and conduct comparative studies across regions and countries. Because the externally induced ambidexterity dilemma is theoretically novel, longitudinal or mixed-method designs are needed to assess whether this mechanism systematically predicts SME eco-innovation outcomes over time.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in Japan confront the challenges posed by decarbonization and the expansion of renewable-energy markets. Drawing on three waves of free-response surveys conducted between 2021 and 2024, the analysis revealed a highly consistent set of constraints across financial, technological, organizational, institutional, and regional dimensions. These patterns, synthesized through the KJ method and summarized across Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, provide a comprehensive picture of the structural difficulties SMEs face.

Three overarching conclusions emerge.

6.1. External Pressure Drives SME Eco-Innovation, but Internal Capacity Gaps Persist

SMEs frequently initiate decarbonization activities not from internal strategic motivation but in response to external demands such as customer expectations, regulatory requirements, and supply chain standards. However, as indicated in the challenge categories identified in Table 1 and the extensive support needs summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, SMEs often lack the absorptive capacity required to translate external pressure into systematic innovation actions. This persistent mismatch—conceptualized here as the exposure gap—limits SMEs’ ability to sustain eco-innovation activities over time.

6.2. SMEs Face an Externally Induced Ambidexterity Dilemma

The results also highlight the structural difficulty SMEs face in balancing exploration (new business development) with exploitation (existing operations). Unlike large firms, which may allocate separate units or slack resources for innovation, SMEs are compelled to explore under externally imposed decarbonization pressures while simultaneously managing resource-intensive daily operations. Table 4 and Table 5 illustrate that SMEs lack the financial, organizational, and technical foundations required for ambidexterity to develop. This study therefore identifies an externally induced ambidexterity dilemma, extending existing ambidexterity theory by demonstrating how external actors may force exploration upon capacity-constrained firms.

6.3. A Multi-Dimensional, Ambidextrous Support Architecture Is Necessary

Finally, the results reveal that SME support needs are multi-layered and mutually reinforcing. As shown in Table 2, Table 3, and Table 6, SMEs request a combination of financial assistance, technical expertise, simplified administrative procedures, human resource development, market creation, and regional collaboration. No single measure is sufficient. The study therefore proposes an Exploration–Exploitation Support Matrix that aligns:

- exploration-oriented support,

- exploitation-oriented support, and

- integrative institutional support.

This framework provides practical guidance for policymakers, intermediary organizations, financial institutions, and local governments seeking to promote SME participation in decarbonization initiatives.

6.4. Final Remarks

SMEs will play a central role in realizing a decarbonized economy. However, the findings of this study suggest that environmental transition policies must move beyond isolated subsidies or technology programs and instead focus on building systemic, long-term capabilities. By integrating perspectives from eco-innovation, absorptive capacity, and organizational ambidexterity, this study highlights the need for coordinated, ambidextrous support ecosystems that enable SMEs not only to comply with environmental standards but to innovate sustainably.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative survey data analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with participating firms.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the results of the Research Committee on Ambidextrous Management of Small and Medium-sized Manufacturing Enterprises and the Research Committee on the Revitalization of Industrial Clusters and Regional Industrial Innovation organized by the Economic Research Institute, Japan Society for the Promotion of Machine Industry, Tokyo, Japan. I would like to thank the members of the committee for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Example of Card Clustering Using the KJ Method.

Table A1.

Example of Card Clustering Using the KJ Method.

| Opinion Card (Excerpt) | Assigned Cluster | Category |

|---|---|---|

| “We lack engineers who can handle renewable-energy technologies.” | HR-07 | Human Resource Limitations |

| “Subsidy application procedures are too complex for small firms.” | INST-04 | Administrative and Institutional Burdens |

| “We need clearer guidelines for decarbonization management.” | INFO-03 | Information Provision and Institutional Clarity |

| “Existing production already uses all available manpower.” | ORG-11 | Organizational Capacity Constraints |

| “Entering the renewable-energy market requires large upfront investments.” | FIN-02 | Financial Burdens |

References

- Horbach, J. Determinants of Environmental Innovation—New Evidence from German Panel Data Sources. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of Eco-Innovations by Type of Environmental Impact. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, P.; Romero-Jordán, D.; Peñasco, C. Analysing Firm-Specific and Type-Specific Determinants of Eco-Innovation. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2017, 23, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Zimmermann, A.; Raisch, S. How Do Firms Adapt to Discontinuous Change? Bridging the Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity Perspectives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Drivers of Different Types of Eco-Innovation in European SMEs. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatten, T.C.; Engelen, A.; Zahra, S.A.; Brettel, M. A Measure of Absorptive Capacity: Scale Development and Validation. Eur. Manag. J. 2011, 29, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The Interplay between Exploration and Exploitation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesidou, E.; Demirel, P.; Zhang, S. Eco-Innovation and Organizational Ambidexterity in SMEs. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 2301–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakita, J. The KJ Method: A Scientific Approach to Problem Solving; Kawakita Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 1975. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).