1. Introduction

In recent years, there have been many changes in HEIs due to globalization which, on the one hand, has reduced public investment, and on the other hand, has stimulated the research, development, and innovation activities that are necessary for increased performance in the economy [

1,

2]. Investments in education have become a necessity for the performance and transformation of universities, with studies claiming that they lead to innovation, entrepreneurial activities, and the adaptation of technology [

3,

4]. At the same time, investments and digitalization in HEIs are observed through the positive effect on teaching staff and graduates (there are improvements in their cognitive and entrepreneurial skills, adaptability to progress and, ultimately, productivity [

5,

6,

7]. The need for transformation thus arises as a result of global societal and technological transformations, which present new demands on the graduate market, which expects a workforce that is not only highly qualified but which is also capable of “new productivity”, attainable through innovation, advanced technology, high efficiency, and superior quality [

1,

6,

8]. In order to identify common trends and possible differences in the formation of innovation-based economic systems, studies that have analyzed the global innovation index were conducted. These have shown that the innovative development of the economy contributes to ensuring competitiveness and becomes a tool for ensuring sustainable development and economic growth [

9,

10]. The proven positive impact of RDI on economic growth is also discussed by other studies, which support the need to stimulate educational and research activities in addition to the development of entrepreneurship [

11], but also the assessment of the key innovative principles of economic systems [

12].

Given the role of HEIs in the development of economies and the conceptual, empirical, and contextual developments captured, this research complements existing studies, highlighting the differences between economies (under the imprint of the transformations generated by the steps towards sustainable economies). In contrast, variables influencing the performance of HEIs among Eastern European countries (emerging countries) are addressed here, which seem to not be researched in this context in the specialized literature.

The research questions that constituted the starting point in the empirical investigation are as follows:

Q1: What are the latent dimensions (main factors) that explain most of the variation in the analyzed indicators at the level of the studied European countries?

Q2: What common patterns of performance can be identified among Eastern European countries based on the scores obtained on the main factors?

Q3: What groups (clusters) of countries are formed based on the factor profile?

Q4: What policy models/directions can be inferred for each type of factor profile identified, and what interventions could improve countries’ performance?

The contribution to the literature is made by developing a conceptual framework supported by a wealth of empirical evidence, which illustrates the close relationship between the indicators. Thus, the contribution of HEIs to the economy is captured in the context of existing transformations at both the national and international levels.

Analyzing the issues mentioned above, in order to capitalize on the effect of HEIs in the economy, the study conducts an analysis of the main factors having an explanatory character, aiming to develop theoretical constructions that underline the observed covariance between variables. The analysis reveals the conceptual dimensions that support the performances at the country level, according to the values obtained (innovation, digitalization, partnership, etc.).

Section 2 consists of a literature review, through existing studies on Higher Education Institutions, and highlights their role in societal transformation and the need and implications for collaboration and innovation.

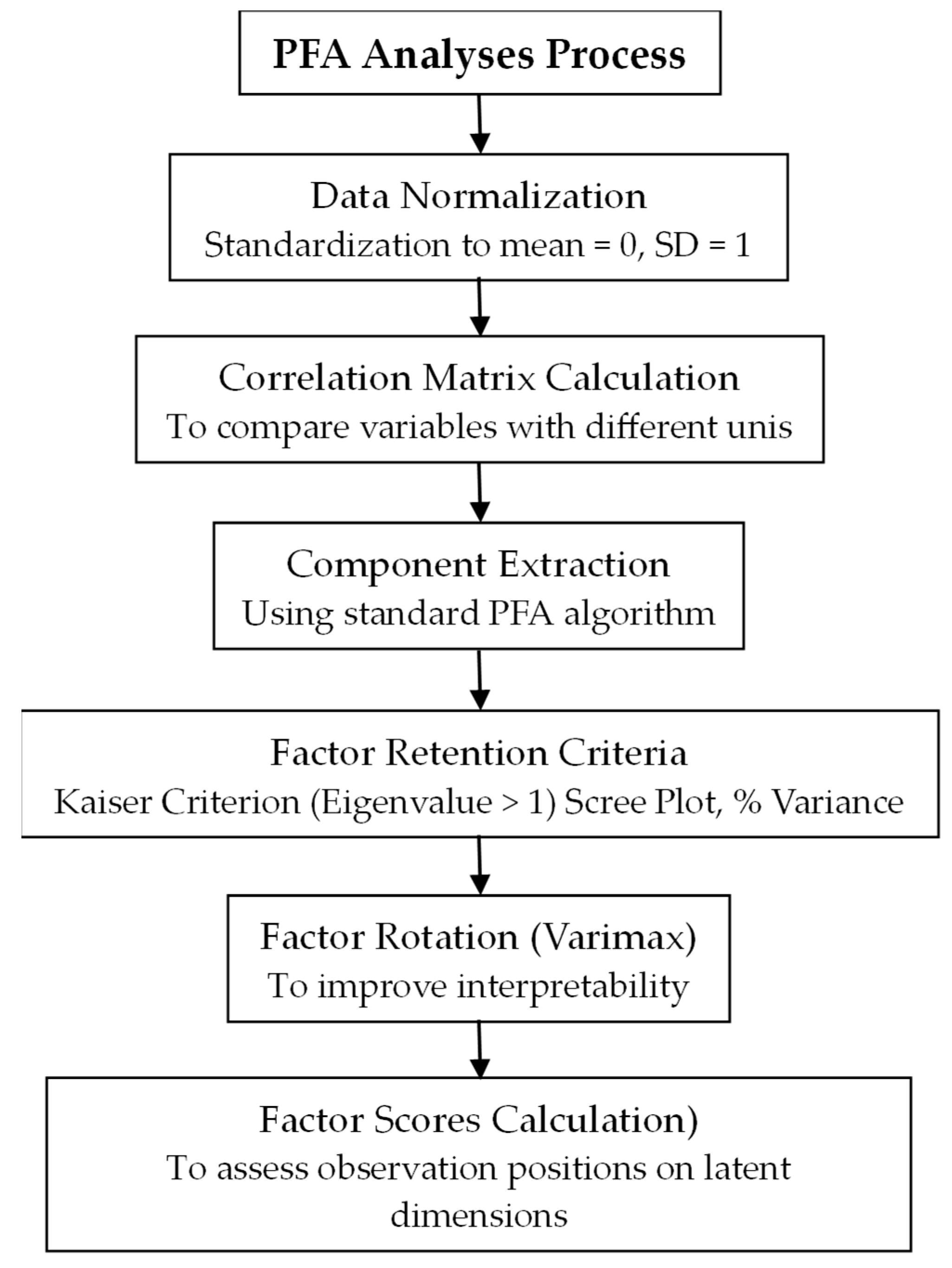

Section 3 builds the theoretical framework for the analysis of the main factors through multivariate methods that allow for dimensionality reduction and the identification of latent structures in a set of intercorrelated variables.

Section 4 includes the results obtained from the processing of the material and confirms a fit of the factor model that explains the common variant of the extracted factors.

Section 5 presents the conclusions regarding the results obtained, and

Section 6 presents the theoretical and practical implications of the research.

Section 7 describes the limitations of the research and proposes possible future research.

4. Results and Discussion

Following the factor analysis (PFA), using the data presented in

Appendix A,

Table A1, and the correlations between the original variables and the initial main factors, before any rotation (see

Appendix A,

Table A2), led to us obtaining the scores of each observation (country–year) (see

Appendix A,

Table A3).

Thus, the following were obtained: the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix (which provide numerical criteria to justify the number of factors retained—see

Table 3), the eigenvectors of the correlation matrix (to maximize the loadings on some factors and minimize them on others—see

Appendix A,

Table A4), and the contributions of the variables, based on correlations (additional validation of the interpretation of the factors, see

Appendix A,

Table A5).

Six main factors (F1–F6) were retained, which, according to the previous analysis, explain a significant proportion of the total variance in the data. These six factors were named and interpreted as follows:

F1: Collaboration in innovation and R&D (associated with patent families, ICT use, university–industry collaboration, software spending, joint venture agreements, and tertiary education enrollment).

F2: Academic research performance and investment (associated with H-index of citable papers, QS university rankings, gross R&D expenditure, global corporate R&D investors, patents of origin, science and engineering graduates, and inward tertiary mobility).

F3: Advanced technology production and talent flow (associated with high-tech production, patents of origin, inward tertiary mobility, tertiary education enrolment, and labor productivity growth).

F4: Time evolution/systemic progress (predominantly associated with the variable “Year”, indicating a general trend of progress or regression).

F5: Cluster development (mainly associated with cluster development stage, ICT use, and variable “Year”).

F6: Education investment (principally associated with education expenditure as % of GDP).

Table A3 (

Appendix A) contains the factor scores of each observation (country in a given year) for these six main factors, together with the scores for F7–F19, which, in the context of the decision to keep only six, will not be directly interpreted. The formal analysis of the factor scores (2022–2024) (see

Appendix A,

Table A3) provides the positioning of each observation (country per year) in the reduced space of the main factors. From the comparative analysis of the countries, the following observations can be deduced:

BG presents a mixed profile, with pronounced strengths and weaknesses, and a dynamic evolution over the period. On F5 (cluster development), it has a strong point in 2022 (score of 2.65), indicating exceptional cluster development. However, there is also a significant decrease in this score in 2023 (1.05) and 2024 (0.87), although it remains above average, suggesting either a maturation of the process, a slowdown in the growth rate, or a reorientation of priorities. On F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development) and F3 (advanced technology production), it demonstrates a positive trend of improvement, moving from negative scores in 2022 (−0.60 at F1 and −1.26 at F3) to positive scores at F1 (0.54) and less negative scores at F3 (−0.21) in 2024. This result indicates the country’s efforts to modernize and integrate into the knowledge-based economy. The result from F2 (academic research) shows that the performance for F2 is constantly deteriorating, from −0.95 in 2022 to −1.92 in 2024, demonstrating persistent or increasing challenges in the field of academic research. Similarly, F4 (temporal evolution) reflects systemic progress, which decreases from −0.41 to −1.86, signifying a significant slowdown in the overall pace of development.

CZ is distinguished by a solid performance in research and a positive dynamic in technology adoption, with some volatility in the development of clusters. F2 (academic research) maintains a good and constant score throughout the period (2022: 2.34, 2023: 2.58, and 2024: 2.57), establishing itself as a regional leader in academic performance and R&D investments. F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development) and F3 (advanced technological production) show an increase (F1 increases from 0.70 to 2.28, and F3 increases from −0.44 to 1.87), showcasing a consolidation of innovation capacity and accelerated expansion in high-tech production sectors. F4 (temporal evolution) decreased from a positive score (1.83 in 2022) to a negative one (−0.41 in 2024), suggesting a slowdown in the overall pace of progress. F5 (cluster development) shows volatility, falling sharply from 0.66 in 2022 to −1.05 in 2023, with a slight recovery to 0.13 in 2024.

EE positions itself as an agile innovator, with an exceptional increase in innovation capacity, but with challenges in maintaining systemic progress and support for education. In F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development), an upward trajectory is observed, with scores of 2.18 (2022), 3.72 (2023) and 5.17 (2024). EE is thus the undisputed leader when it comes to innovation. On F3 (advanced technology production), a constant improvement is observed, from −0.89 to 0.78, indicating a transition to a more advanced technology-based economy. F4 (temporal evolution) shows a decrease from 1.99 to −0.10; F6 (investments in education) shows a decrease from 0.82 to −0.50, which reveals that there is a slowdown in the overall pace of development and a decrease in efforts to support education. This could pose long-term risks to the sustainability of innovation. F5 (cluster development) shows a significant deterioration, namely a decrease from 0.94 to −0.44.

HU combines academic research and cluster development (with a strong emphasis) but highlights regression in systemic progress and volatility in investments in education. F2 (academic research) has a good and relatively consistent performance (2.94 in 2022 and 2.90 in 2023); despite a notable decrease in 2024 (1.43), it remains above average. In F5 (cluster development), the initial very high (1.35) in 2022 and consistent in 2023 (1.28). Scores drastically reduced in 2024 (0.02), indicating a potential slowdown in development or a change in focus. In F4 (temporal evolution), there is a constant and pronounced deterioration, from −0.31 to −1.95, signaling a regression in the overall progress of the system. F6 (investments in education) fluctuates significantly, with a strong increase in 2023 (1.56), followed by a steep decrease in 2024 (0.20).

LT asserts itself as a growing player in innovation, but encounters structural challenges in academic research, technological production, and particularly with a regression in systemic progress. F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development) has an impressive upward trajectory (an increase from 0.70 to 3.10), indicating rapid consolidation of innovation capacity. F4 (temporal evolution) drops dramatically from 0.58 to −1.47, suggesting that, although there are advances in innovation, the overall pace of development has slowed down considerably, or even regressed. F2 (academic research) and F3 (advanced technological production) shown below-average values throughout the period, indicating structural deficiencies. In F6 (investment in education), there is a deteriorating trend, from −0.33 to −0.78, representing a problematic aspect for the sustainability of innovation in the long term.

PL presents a contrasting profile, with a solid performance in academic research, but persistent deficiencies in advanced technological production, and an alarming deterioration in systemic progress. F2 (academic research) maintains a high score (2.88 in 2022, with a temporary decrease in 2023 to 1.43, and a recovery to 2.12 in 2024), confirming the country’s role as a significant contributor to academic research. In F3 (advanced technological production), a major vulnerability was recorded, with extremely low and negative scores (−3.61 in 2022, −2.93 in 2023, −1.85 in 2024). Although a slight improvement is observed, it remains an area that requires substantial interventions. In F4 (temporal evolution), the situation deteriorated (from −0.04 to −2.33), indicating a reversal of systemic progress, and stagnation or regression at the macroeconomic level. In F5 (cluster development), a decrease from −0.16 to −1.84 can be seen, signaling difficulties in developing or maintaining cluster ecosystems.

RO faces fundamental challenges in innovation and research, despite certain positive initial investments in education and cluster development. In F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development) and F2 (academic research), extremely low scores are recorded over the period (−3.16 in F1 and −2.56 in F2 in 2022), revealing a weak basis for innovation and academic research. Subsequently, a slight improvement trend is observed in F1, but F2 remains at a problematic level. In F3 (advanced technology production), an improvement is recorded, moving from −0.70 to 0.38, which indicates an orientation towards more technological sectors. F5 (cluster development), after an initial score above average (0.77 in 2022), sees a drastic and continuous deterioration (up to −2.02 in 2024). This warrants an in-depth analysis of the policies or factors influencing the formation of clusters. F6 (investment in education) starts with an incredibly positive score (1.39 in 2022), which drops significantly to −0.18 in 2024, signaling a decrease in investment efforts in human capital.

SK stands out for its excellence in technological production, but faces significant gaps in innovation and academic research, as well as a deterioration in systemic progress. In F3 (advanced technological production), it maintains a high and constant score (2.52 in 2022, 2.14 in 2023, and 2.14 in 2024), consolidating its leading position in this area. In F6 (investment in education), from an extremely low initial score (−3.73 in 2022), a spectacular recovery is observed in 2023 (0.30), with maintenance of the positive score in 2024 (0.53), indicating a reorientation of political priorities. In F1 (innovation and collaboration in research and development) and F2 (academic research), we observe values that remain at problematic levels throughout the period, with predominantly negative and very low scores (3.24 in F1 in 2022, −0.95 in F2 in 2024). In F4 (temporal evolution), the values decrease from a very positive level (1.68) to a negative level (−0.58), signifying a general slowdown in progress.

By analyzing the countries comparatively, it can be said that there is a divergence in innovation profiles, with clear differences between countries on the different dimensions of innovation and development. Thus, the lack of convergence (divergence) shows that countries are not evolving in the same direction or with the same intensity in the field of innovation and development (both in terms of performance and innovation structure). Some countries (e.g., EE) are leaders in innovation and collaboration in R&D, while others (e.g., CZ, HU, PL) excel in academic research, and SK dominates in production of advanced technologies. This suggests that national innovation strategies differ substantially. A common trend, albeit with different magnitudes, is the deterioration of the F4 score (temporal evolution) for most countries (e.g., CZ, HU, PL, RO, SK). This could indicate a slowdown in the overall growth rate or systemic progress in the region, possibly due to economic shocks (the war in Ukraine) or ineffective policies. The F5 dimension shows considerable volatility and, in most cases, a downward trend after 2022 (e.g., BG, CZ, HU, PL, RO), with the notable exception of LT in 2024. This may signal difficulties in sustaining cluster-based innovation ecosystems. Investment in education (F6) varies significantly, with noteworthy positive developments in SK and CZ in 2023, but negative trends in EE, LT, and RO. This highlights the lack of a uniform approach in prioritizing spending on education, which is critical for human capital and innovation. Each country seems to have one or two “pillars” of performance in which they score consistently high (e.g., F1 for EE; F2 for CZ/HU/PL; F3 for SK), which showcases that there are some comparative advantages or results of long-term strategic investments. Retaining six principal components (F1–F6) was justified by their ability to explain over 83% of the total variance in the data, providing a substantial and interpretable representation of the original information (see

Table 3).

As shown in

Table 3, the first six factors account for over 80% of the total variance, denoting a strong explanatory power. For eight factors, the cumulative variance exceeds 90%, while for the fourteenth, it reaches about 99%, suggesting a marginally decreasing contribution of the later factors.

Upon the analysis of

Table 3, there are 19 factors (corresponding to the 19 active variables). In the second column, “Eigenvalue”, the amount of variation explained by each main factor can be found. In column 3, “Total”, there is the percentage of the total variation explained by each factor. Column 4, “Cumulative”, contains the sum of the eigenvalues up to that factor (cumulative). In column 5, the “Cumulative percentage of variation” is explained up to that factor. By selecting the relevant factors (Kaiser’s criterion and cumulative thresholds), one can observe that only the first six factors have an eigenvalue > 1, and together they explain ~83.17% of the total variation. This indicates that the most relevant information is captured in just a few factors [

70]. Using both the rotated factor loadings matrix (see

Appendix A,

Table A4) and the information in the “Variable contributions, based on correlations” table (see

Appendix A,

Table A5) (specific to STATISTICA 8.0 software), it was possible to define and understand more in depth what each of these factors measures.

The correlation matrix is presented in

Table 4.

The correlation matrix gives direct, simple linear associations.

From the analysis in

Table 4, we can see strong links between education, research, and innovation. Thus, the indicators GERD (R&D expenditure) vs. PF (patent families) have a high correlation value (0.78), which reveals that investments in R&D have led to the existence of more patents.

Between the indicators GERD and QSUR (university ranking), a moderate correlation (approx. 0.25) can be seen, which shows that countries with better-ranked universities invest more in R&D.

The correlation of GERD vs. GSE (science and engineering graduates) is also high (0.68), expressing that more graduates are associated with more research.

The correlations TE (tertiary enrolments) and PF (patents) have a high value (0.51), which conveys that a developed tertiary system generates more patents.

The role of collaboration and the innovative ecosystem is observed through the UIRDC, SCD, and JVSAD indicators. One can notice that UIRDC (university–industry collaboration) is positively correlated with GERD (0.52) and TE (0.49), which indicates that technology transfer and collaboration stimulate research and education. SCD (cluster status) is positively correlated with PF (0.71) and PO (0.72), which shows that cluster development is essential to produce patents and scientific documents. JVSAD (joint ventures and alliances) is positively correlated with PF (0.77), resulting in strategic agreements producing changes, ultimately resulting in an active innovation environment.

The impact of ICT can be identified through the ICTA, ICSTU, and SS indicators. From the analysis of the correlation matrix, one can see that ICTA (access to ICT) and ICTU (use of ICT) are positively correlated with TE (0.38 and 0.43), showing that a high-performing educational environment facilitates access and use of technology. At the same time, ICTU and PF are also correlated (0.55), indicating that the use of technology favors the production of patents. SS (software spending) has negative correlations with TE (−0.49) and ICTU (−0.55), which may imply that countries stronger in ICT use and tertiary education spend proportionally less on software.

From the analysis of the correlation matrix, one can also observe significant negative correlations given by LPG with GERD and TIM, and HTM with TE. Thus, LPG (productivity growth) is negatively correlated with GERD (−0.48) and TIM (−0.59). It may indicate a time lag between investments in R&D and the increase in effective productivity. HTM (high-tech production indicator) has a strong negative correlation with TE (−0.77), showing a structural difference between an education-based economy and one based on high-tech production.

In the correlation matrix, weak or absent correlations can also be identified between EE (educational expenditure) and TIM (student mobility), GERD, or GCRDI, revealing that the amount spent does not automatically guarantee mobility or investment in R&D.

The robust correlations between research and development expenditure (GERD) and innovation performance indicators, such as patenting (PF) and scientific production (CD), confirm the central role of R&D financing in stimulating innovative activities and generating intellectual capital. The results also denote that university–industry collaboration (UIRDC) constitutes an essential vector in the process of technology transfer and economic valorization of research results. This synergy is supported by student and researcher mobility (TIM), as well as by the development of regional clusters (SCD), which facilitate innovative agglomerations and intensify knowledge flows.

Linear associations with/without multiplicative effects can be sought in groups of two factors (e.g., ŵ = ax + by + cxy).

The importance of digital infrastructure and skills is highlighted by the positive correlations between access to and use of ICT (ICTA, ICTU) and educational and research indicators. This emphasizes the need to strengthen digital capacities in educational and research systems to support competitiveness in the knowledge economy.

The analysis also highlights the complexity of the relationships between variables, as well as potential time lags between investments and effects on labor productivity growth (LPG). These observations recommend a long-term perspective in the formulation and implementation of public strategies.

To observe the distribution of countries (using a scatterplot), a factor map was created in the two-dimensional space defined by the first two main factors (F1 and F2) extracted following a factor analysis (PFA, see

Table A3,

Appendix A), for the year 2024, applied to a set of indicators related to education, research, innovation, digitalization, and the economic impact of knowledge. Using a scatterplot, a comparison can be made between at least two sets of values or pairs of data, drawing attention to the relationship between them (see

Figure 3).

Quadrant I (top right), according to

Figure 3, presents consolidated innovation and digitalization profiles, with countries located in this quadrant showing positive scores on both Factor 1 and Factor 2, indicating a high level of performance in the areas of research innovation and digitalization (CZ, PL and HU). CZ (F1: 2.28, F2: 2.57) shows a balance between investments in education and research, innovation capacity (measured by indicators such as patents and university–industry collaboration), and international openness (student mobility and international research connections). PL (F1: 0.57 and F2: 2.12) displays an average performance in innovation (F1), but a good score in collaboration and innovation system (F2), having a functional institutional network, with potential for increasing research investments. HU (F1: 0.24 and F2: 1.43) is also in this quadrant, suggesting a convergence towards a knowledge-based development model, with a growing institutional network, but a modest level of direct investment in knowledge. Countries in this quadrant demonstrate the capacity to support an innovative ecosystem that benefits from solid investments in research and development, effective collaboration between universities and industry, openness to academic mobility and internationalization, and the integration of information technologies into institutional systems. These characteristics give them a competitive advantage in the transition to a knowledge-based and technology-based economy.

Quadrant II, according to

Figure 1, does not contain the countries included in the study.

Quadrant III, according to

Figure 1, shows countries with a weak scientific and international profile (RO and SK). These countries are in a vulnerable position, with low scores on both factors, signaling major risks of academic isolation and inefficiency in research and innovation. In RO (F1: −1.59 and F2: −2.57), the lowest score of all countries can be observed, indicating an overall low performance in terms of both research infrastructure and digital and collaborative integration. The causes are chronic underfunding of research (R&D spending below 0.5% of GDP), low participation in international networks and collaborative projects, universities performing below expectations in global rankings, weak industrial partnerships and governance issues, and a lack of coherent internationalization strategies. In SK (F1 = −1.42, F2 = −0.95), there is a poorly developed and poorly connected innovation system, aggravated by modest scientific performance and low outputs (articles, patents, citations), low participation in European research programs and networks, and lack of incentives for public–private cooperation and academic mobility. These two countries urgently need structural reforms to exit the stagnation zone and rebuild their position in the European Research Area.

Quadrant IV, according to

Figure 3, shows an emerging scientific base, but a weak international openness (EE, LT and BG). These countries demonstrate a relevant domestic potential in education and research, but face limitations in international integration, which prevent them from capitalizing on technical progress. The very high score on F1 positions EE as a regional leader in innovation, research and digitalization, while there is a slightly negative score on F2 (F1 = 5.17, F2 = −0.65). The value obtained on F2 suggests that, although technologically advanced, EE is pulled far below F2. The potential for growth in institutional cooperation (strong digital infrastructure and STEM education) could contribute to relaunching the internationalization strategy to re-enter Quadrant I. In LT (F1 = 3.10, F2 = −1.94), one can observe progress in the quality of research and doctoral training, a low degree of connection to European projects and problems in attracting and retaining international talent (requiring strategic investments in connectivity and partnerships). In BG (F1 = 0.54, F2 = −1.92), there are modest investments in research, but progress in university education, research institutions that often operate in isolation, which require active policies to connect to international networks. These states are at a turning point: scientific performance is present, but without internationalization, it risks stagnation.

Following simplified clustering for the data for 2024, we produced

Table 5, which includes the standardized scores of the factors, grouped according to the similarity of performance in innovation, education, and digitalization.

From the analysis of F1–F6, according to

Table 5 and through simplified clustering (indicative, K = 3), three clusters are identified:

Cluster 1—“Lagging systems”. This cluster includes countries with negative or close to zero values for most factors: BG, RO, and SK. They are countries with isolated potential, but which suffer from a lack of coherence between the pillars of research, education, and applicability. These require integrated interventions: university partnerships, governance reforms, and incentives for applied innovation. BG is a mixed case: a relatively good ecosystem (F1) and good efficiency in applied innovation (F5) but lacking academic excellence (F2). RO is the country with the most unbalanced system, with very low scores on almost all factors. SK has good value on F3 (international education and applied knowledge), but has structural deficiencies in the scientific system and the innovation ecosystem. Cluster 1 is characterized by fragmented innovation ecosystems, modest scientific capacity and academic excellence, and weak collaboration between public education and state institutions (F4 is consistently negative). Although some factors (e.g., applied digitalization and productivity in SK or efficiency in science and applied innovation in BG) indicate potential, the lack of cohesion between the pillars of education, science, and digitalization hinders the transition to an integrated knowledge-based development model.

Cluster 2—“Scientific leaders”. This cluster includes countries CZ, HU, and PL with positive or moderate values for F1, F3, and F5, and variable values for F2, F6. These are emerging countries in research and higher education systems, but with challenges in transforming knowledge into economic value (especially PL). CZ is a clear leader on all pillars of research, innovation, and education. HU has a relatively balanced and progressive but modest profile. PL has a strong contrast for high scientific capacity (F2) but lacks applied innovation and digitalization (F5, F6). To perform, these countries need technology transfer policies, incentives for innovative SMEs, and the integration of digitalization into industry. Cluster 2 is distinguished by scientific capacity, academic excellence (F2), and a reasonable degree of internationalization of knowledge (F3). However, low performances in the field of applied innovation (F5) and economic digitalization (F6) indicate a disconnect between research and applicability. In addition, negative scores on F4 suggest a rigid educational governance, unable to support the modernization and connection of scientific ecosystems with the labor market.

Cluster 3—“Digital innovators”. This cluster includes countries with extremely positive or negative values, namely EE and LT. These countries have functional innovative ecosystems but are poorly supported by the scientific publication system. EE has a very advanced innovative ecosystem (F1), but without a consolidated scientific capacity (F2). It seems to perform well in the private sector, yet weakly in the academic sector. LT is similar, but with weaker values, with a slight advantage in applied innovation (F5). Increasing academic excellence could be achieved through international partnerships and integrating research into public policies. EE and LT (located in cluster 3) have robust innovation ecosystems (F1), especially in the digital domain, but an insufficiently consolidated scientific base (negative F2). There are also significant differences in institutional governance (F4)—EE has a more coherent and functional system than LT. As a result, this cluster reflects a development model based on accelerated digitalization and service-oriented innovation but risks long-term fragility in the absence of a solid scientific foundation.

This study, like others, shows that countries with high levels of human capital create more fertile environments for the implementation of investments in education, and the effectiveness of investments has significant implications for the development of economies [

44]. The result generated by F1 (innovation and digitalization ecosystem) is in agreement with other studies which claim that innovation performance depends on the institutional context [

71,

72]. Kustec and Zalokar support the existence of a link between the political–geographical distribution of countries in terms of innovation performance and the development of democracies in the countries they are part of [

71]; meanwhile, other studies show the uneven progress of curricular reforms and highlight the importance of institutional capacity and external partnerships in innovation, starting from curricular innovation [

72]. In the present study, higher values are recorded for F1 in certain countries (EE, LT and CZ), which reveal greater possibilities for innovation and digitalization that produce benefits in the economy, but also lower values (RO and SK), where possibilities are limited or low. The result of this study is also in agreement with the study conducted by Blikhar et al., who claim that the geopolitical context (the war in Ukraine) influenced the level of innovative economic development in Eastern European countries after 2022, leading to a decrease [

9], a fact also signaled by the study conducted here through F1 (by reducing collaboration in innovation and R&D). The results generated by the analysis of countries through F2 (scientific capacity and academic excellence) and F3 (applied knowledge and international education) indicates that, with the creation of knowledge-based value, international connections appear among high-tech and industrial corporations, supporting the development of economies [

73,

74]. Consequently, this study observes that there are countries which have consolidated their positions (CZ, PL and HU), but also countries that still need to make efforts (RO, BG) for development. This result complements previous research and explains how networking, training, applied research, and productive interactions between the university and the local economic environment can be favorable and can contribute to the development of economies [

73,

74]. According to the results of this study, combined with those of previous studies, it can be seen that research and development collaborations (the partnership between the university and the economic environment) become viable where there is a higher technological maturity and also a well-developed capacity to generate and consolidate knowledge. This is explained by the present study by low values recorded in the F1, F2, or F3 by certain countries, which explains the stagnation or slowdown in the economic development process. According to Audretsch et al., once there is an adequate internal knowledge base, companies can integrate their know-how with external knowledge by developing collaborations with scientific and technological development organizations, they can hire and improve human resources, or they can contribute to the financing of R&D investments [

75]. From the study conducted here, this is observed through the close negative values obtained by most of the countries studied through F4 (public education and institutional collaboration between economies), which explains the lack of connectivity between organizations. Furthermore, for F5 (efficiency in science and applied innovation) and F6 (applied digitalization and productivity), the results are not close for Eastern European countries, but they are in agreement with the results of previous studies, which confirms the need to support academic entrepreneurship and strengthen network links with industry and investors [

76,

77].

The study justifies itself and makes additional contributions to the European Scoreboard, which shows that Europe’s innovative performance “remains strong, but growth has slowed” [

78]. It ranks countries by innovation performance through a series of contextual indicators at the level of all actors involved in the economy, with the indicators being grouped into distinct groups (performance and structure of the economy, business and entrepreneurship, innovation profiles, governance and policy framework, environment and demography); meanwhile, the current study ranks countries by the performance of contextual indicators only at the level of HEIs. Both studies show a slowdown at the level of European countries; thus, the European Scoreboard shows EE in the category of strong innovators (above the EU average), followed by LT and CZ as moderate innovators (below the EU average), and with HU, PL, SK, BG, and RO as emerging innovators (performing below 70% of the EU average [

78]). This study completes the previous study with the latent elements of HEIs, which can explain the slowdown and presents different values of several contributing factors, leaving their mark on the results obtained for each country. In this study, for the year 2024, the values obtained for the first factor (innovation and digitalization ecosystem) place the countries in similar positions: EE and LT can be seen in the first places, and SK, BG, and RO are in the last places. In addition, other latent factors have been included, namely F2–F5 (scientific capacity and academic excellence, applied knowledge and international education, public education and institutional collaboration, efficiency in science and applied innovation, and applied digitalization and productivity).

The three hypotheses formulated in this study were confirmed based on the empirical results of the PFA and the subsequent clustering. The analysis supported a descriptive understanding of national performance, in addition to the formulation of differentiated policies on a scientific basis, providing a valid framework for supporting functional partnerships in the region.

The PFA demonstrated that innovation and economic development are multidimensional phenomena, effectively captured by the six extracted factors. These factors provide an essential analytical framework for making cross-national comparisons and longitudinal monitoring of progress, identifying the specific strengths and vulnerabilities of each national innovation system, and informing public policy strategies; thus, more targeted interventions can be facilitated, stimulating growth on deficit dimensions and consolidating existing advantages.