Abstract

The adoption of telework increased as a sustainable strategy after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, its impact on transportation and energy consumption are controversial, emphasizing the need for context-specific analysis. This research developed a System Dynamics (SD) simulation that integrated the generalized Bass Diffusion Model (BDM) and Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to analyze telework diffusion in organizations and its influence on transport-related CO2 emissions and energy consumption in Colombia. Internal conditions, particularly managerial attitudes and perceptions of telework performance, play a crucial role in the adoption rate. Telework adoption follows a weak S-curve pattern primarily driven by internal dynamics rather than external pressures, lagging behind the projections set by public policies and global trends. Simulations based on government data for the period 2012–2022 indicated that the number of teleworkers could reach 1.61 million by 2032, resulting in annual energy savings of approximately 1.5% and a 2% reduction in transport-related CO2 emissions. Sustained governmental tracking of sectoral adoption and including records of household energy use will support sensitivity analysis and strengthen model robustness. The integrated SD, TAM, and BDM modeling approach identified critical factors to boost telework adoption and its environmental benefits, providing insights for sustainable organizational strategies and public policies.

1. Introduction

Telework, also known as telecommuting, is recognized as a key strategy to reduce the environmental footprint of companies and support broader regional sustainability policies. It refers to work performed outside the office environment, where technology enables employees to perform job duties from home or other remote locations [1]. Telework emerged in the 1970s as a solution to reduce commuting and increase flexibility by the substation of telecommunications for physical travel [2]. Since then, it has expanded with the advancement of information and communication technologies (ICTs) [3]. Telework can be understood through four dimensions: space, as work conducted away from the central office [4]; time, which refers not only to flexible scheduling and asynchronous arrangements but also to the possibility of organizing work as supplementary hours, part-time, or full-time modalities depending on organizational needs and individual agreements [5]; ICTs, as reliance on digital infrastructures to substitute commuting [6]; and contract issues, through organizational agreements and employment arrangements that regulate remote work [7], making telework a multidimensional phenomenon that reshapes the organization of work in the digital era.

Telework was predominantly adopted by specific sectors and regions before the COVID-19 pandemic, with varying levels of acceptance influenced by cultural attitudes, organizational readiness, and the nature of the work involved [8]. However, the pandemic significantly accelerated the adoption of telework across diverse industries, revealing uneven access to telework opportunities and the potential for increased inequalities, especially among workers in lower-paid or less-skilled jobs and those in regions with less developed technological infrastructure [9,10,11]. An estimated of 23 million people in Latin America worked remotely during the second quarter of 2020, representing 20% to 30% of the salaried workforce [12]. Before the pandemic, this figure was below 3%. In Europe, only 5% of the EU’s working population regularly worked from home before the pandemic, but since its onset, 37% have started working from home [13].

In Colombia, 4192 companies had adopted telework practices in 2012, whereas by 2020 the number had increased to 17,253, representing a 500% rise in the number of teleworkers [14]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 55% of companies reported engaging in telework; however, by 2022 this figure had declined to 19% of companies and only 5.1% of the employed population [15]. More recent data indicate that the proportion of salaried employees working under telework arrangements has stabilized at around 6% in 2023–2024, while in the public sector, 34.6% of national-level public employees performed their duties remotely, with marked variations across sectors: 89.0% in Mining and Energy, compared to 8.8% in Defense and 7.2% in Sports [16,17].

In this context, telework has shifted from a necessary measure during lockdowns to a preferred arrangement for many employees, with its adoption being a multifaceted decision influenced by available resources, perceived benefits, and the transformative experience of remote work during the pandemic productivity [3,18,19]. The environmental benefits of telework have become an important criterion for its adoption, particularly in urban planning, transportation, and energy management. Telework can contribute to reduce carbon emissions as it minimizes commuting and energy consumption associated with maintaining office buildings [20]. In Beijing it was found that teleworking could reduce annual carbon emissions from transport by up to 7.05% [21]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Barcelona city experienced a substantial reduction in air pollution due to decreased vehicle traffic, which highlighted the potential of telework to contribute to a cleaner urban environment [9]. A study in Canada reported that homes and offices with occupancy-adaptive technologies consume less energy and produce fewer emissions [22]. However, teleworking could potentially increase residential energy consumption due to more extended home occupancy and the need for heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and lighting [23]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between telework adoption and environmental impacts, suggesting that different tools and models are essential to accurately assess and predict the net environmental benefits of teleworking.

The assessment of environmental benefits of telework adoption and the most influential factors can be complex and controversial. Thus, different models are used to understand individual perceptions and attitudes towards technology adoption. The TAM is a widely accepted theoretical approach for exploring behavioral drivers in innovation adoption [24], while the Bass Diffusion Model (BDM) offers insights into how innovations spread within a population by distinguishing between innovators, who adopt the technology early, and imitators, who follow based on others’ behavior [25]. These models evaluate psychological and sociodemographic factors of individuals, and technology attributes related to consumer choice, with measures like “predisposition to innovate” and “intention to use” [26,27]. Additionally, the use of System Dynamics (SD) supports the assessment of the causes behind behavior variations over time by considering multiple factors, their interconnections, causal relationships, and dynamic complexity [28], which is essential in environmental innovation. These models, in some cases, jointly, have been applied to address a range of adoption challenges in sustainability such as alternative transportation [29,30], renewable energy [31], strategies for reduction greenhouse gas (GHG) emission [32], conversion to green technologies [33,34,35] and teleworking [36].

Energy transition and CO2 emissions are significant challenges achieving the sustainable transition of Latin American cities, driven by economic growth, energy consumption, and transportation systems [37]. It has been estimated that the energy demand will increase by 80% by 2040 [38]. On the other hand, public transport systems are deficient in most cities, meanwhile the growing middle class has driven a sharp increase in vehicle ownership, with the vehicle fleet potentially tripling in the next 25 years [39]. In addition, key economies in the region, heavily dependent on oil, contribute substantially to GHG emissions, placing additional pressure on current resources [40].

Telework offers an opportunity to reduce carbon footprints by cutting down on commuting. Understanding its potential contribution is especially critical in Latin America, where high urbanization rates, transportation emissions, and economic disparities are pressing. Despite the rise in telework during the pandemic in Latin America, unequal access to technology, inconsistent internet infrastructure, and economic disparities persist [12]. Research in the region is needed to further understand critical factors and effects of the adoption of telework to enhance public policies that ensure long-term success and environmental benefits [18]. As an influential economy in Latin America and representative of broader regional trends, Colombia is characterized by high urban growth, increasing service economy, and diverse technological and infrastructural challenges [37,41].

Despite the rapid expansion of telework worldwide, academic literature has rarely integrated organizational innovation theories to explain its adoption and environmental impacts, particularly in emerging economies. Most existing studies focus on developed countries, sectoral case studies, or short-term effects during the COVID-19 pandemic [3,6]. In Latin America, unequal access to ICT infrastructure and structural deficiencies in urban transport systems make the diffusion of telework a more complex phenomenon [38,40]. Furthermore, the application of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has traditionally emphasized individual-level determinants of technology use [24,42], while the Bass Diffusion Model (BDM) has explained the aggregate diffusion of innovations [25,31]. System Dynamics (SD) complements both by representing interactions among variables, flows and feedback structure that shape the adoption process. However, their combined use to analyze telework adoption at the organizational level, and its links with environmental outcomes, remains limited [36,43,44]. Building on this gap, we hypothesize that internal factors like managerial perceptions and organizational conditions slow the diffusion and adoption rates of telework in Colombia, thus reducing its potential environmental benefits regarding transport-related emissions and energy consumption compared to global expectations. The objective of this research was to examine the relationship between telework adoption in organizations and its impact on the transport related CO2 emissions and energy demand in Colombia by using system dynamics simulation based on TAM and generalized BDM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The research was developed in the following stages based on system dynamics modeling methods [45], and its processes, variables, and boundaries were assessed using the TAM and BDM approaches [24,26,34]. (1) Model structure and conceptual framework. The problem was delimited from the processes, variables and system boundaries identified from theories and literature review on telework adoption. (2) Model formulation. The relationships between system variables were assessed through mathematical equations, and it was verified that model results were aligned with the conceptual framework. (3) Simulation of scenarios and analysis of results. Data were used to make predictions for three telework adoption scenarios, to identify the most influential variables and their impact on transport related CO2 emissions and energy consumption. Governmental datasets for Colombia provided counts of firms and teleworkers, as well as perception surveys, for six periods (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022) [14,15,46]. These data were used to parameterize the model with a 2012–2032 simulation horizon.

2.2. Model Structure and Conceptual Framework

A synthesis of theoretical perspectives on telework was conducted to examine and understand the determinants of its adoption and environmental impacts. The system dynamics model was developed in VENSIM version 6.3 PLE 9.4.2. [45]. The TAM and BDM framework was created on the perspective of organizational managers, involving an optional type of innovation-decision, in which the decision to adopt telework is made independently by each individual or adopting unit, rather than collectively as a group [24,25,27,47].

Factors and dynamics governing organizational adoption of telework identified in literature review were grouped in the following determinants. First, the perceived attributes of the innovation, which encompass the characteristics of the telework innovation as perceived by potential adopters such as managers involved in the adoption of telework in their organizations and teleworkers. These attributes, including perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, fundamentally influence an organization manager’s decision to adopt an innovation [8]. Second, the social system in which innovation is introduced. It encompasses the characteristics of the organization and its environment that can facilitate or hinder the diffusion process, as well as the interorganizational communication channels that reflect the paths of information exchange about the innovation among the members of the social system. This concept is derived from both the diffusion of innovations paradigm and BDM, which emphasizes the role of interorganizational communication and/or the influence of a previous experience in the organization on an innovation [24,47]. Third, promotional efforts, which refer to concrete actions by the organization or external agencies to encourage the adoption of innovation, such as government policies that promote it, economic incentives, information sessions, dissemination of promotional messages or training programs [48,49,50]. Finally, previous experience was considered.

Building on these determinants, the literature review was expanded to incorporate additional insights from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Generalized Bass Diffusion Model (GBDM). Within TAM, the perceived attributes of an innovation, particularly perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, have been a critical effect managers’ and employees’ attitudes toward telework adoption [7,24,42]. Similarly, the GBDM provides a framework to analyze how adoption evolves within the social system, highlighting the influence of interorganizational communication, imitation effects, and the role of previous adopters in accelerating or slowing down diffusion [44,51,52]. Moreover, studies on innovation diffusion emphasize the importance of promotional efforts, such as policy interventions, incentives, and awareness campaigns, as external drivers of adoption trajectories [6,47]. Also, the role of previous experience is closely linked to both TAM and diffusion paradigms, since organizational learning and familiarity with telework reinforce positive perceptions and reduce perceived risks of adoption [43].

The original conception of the basic BDM consisted of two stocks “Potential adopters” and “Adopters”, and a single flow, “Adoption rate” [26]. This structure provided a simplified representation of the diffusion process of an innovation, recognizing individuals who are potential adopters of an innovation from those who have already adopted it. However, the theory of diffusion of innovations proposed that individuals usually become active adopters or rejecters of an innovation after an experience phase, a period of “testing” or “trial” [47,53]. This testing phase allows potential adopters to become familiar with the innovation, evaluate its attributes and make informed decisions about its adoption [54,55].

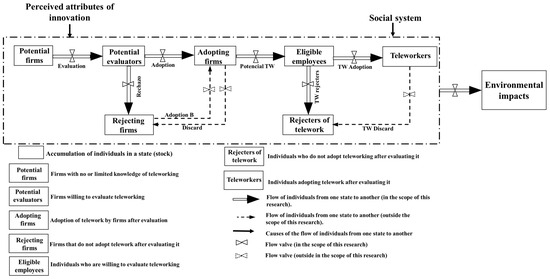

The conceptual framework emphasized the stages through which an individual or an adopting unit goes from first awareness of an innovation, through the formation of an attitude towards the innovation, through the decision to adopt or reject it and the environmental implications of that adoption, the implementation and use of the new idea, and the confirmation of this decision [47]. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework for telework adoption and its environmental impacts, structured through eight main components or stocks: “Potential Firms”, “Potential Evaluators”, “Adopting Firms”, “Rejecting Firms”, “Eligible Employees”, “Rejecters of Tele-work”, “Teleworkers”, and “Environmental Impacts”, all interconnected by transition flows. Potential Firms represent organizations with little or no knowledge of teleworking. From this group emerge the “Potential Evaluators”, referring to firms or individuals willing to test telework before committing to full-scale adoption. After this evaluation stage, some organizations become Adopting Firms, integrating telework into their operations, while others turn into Rejecting Firms, discarding the practice after concluding it is not viable in their context.

Figure 1.

System boundaries and conceptual framework for telework adoption and environmental impacts.

The framework also incorporates the individual dimension. From adopting firms, Eligible Employees arise—workers whose roles allow them to telework. These employees may transition into Teleworkers if they adopt telework, or into Rejecters of Telework if, after a trial phase, they decide not to continue. This trial or testing phase is a key feature of the framework, recognizing that adoption is not always immediate but often involves a period of experimentation prior to a definitive decision. The model is grounded in the perspective of organizational managers as decision-makers, reflecting an optional innovation decision process [27,45,47], where each adopting unit independently decides whether to implement telework, rather than collectively as a group. This highlights the influence of managerial perceptions (image, perceived usefulness, social norms, and prior experience) in shaping adoption trajectories.

Compared with the basic Bass Diffusion Model, which includes only two stocks (potential adopters and adopters) and a single flow (adoption rate) [26], the frame-work in Figure 1 offers a more nuanced and realistic representation of innovation diffusion. By introducing the additional stocks of Potential Evaluators and Rejecters, it explicitly acknowledges the trial phase [47], where potential adopters experiment with the innovation before making an informed decision. The system is bounded by influencing factors such as the perceived attributes of the innovation, the nature of the social system, communication channels, and external promotional efforts. The dynamics of the model for telework adoption is presented in Figure 2, which will be further detailed in the subsequent Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.2.3.

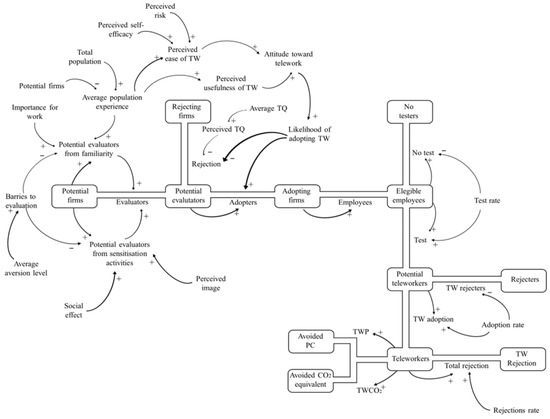

Figure 2.

Stock and flow diagram of telework adoption and environmental impacts. + and − denote positive and negative causal influence, respectively. Abbreviations: TW, Telework; TQ, Telework quality; PC, Power consumption; TWP, telework power saving; TWCO2, transport CO2 savings.

In Figure 2, Positive causal influence means a direct relationship between two variables: when Variable A increases, so does Variable B, and vice versa (where all else is constant). On the other hand, negative causal influence indicates an inverse relationship between two variables; that is, an increase in Variable A would lead to a decrease in Variable B, or a de-crease in Variable A would lead to an increase in Variable B (all else constant) [45]. The diagram traces a sequential representation from potential adopter firms to potential evaluating organizations, illustrating the pathway that leads either to the adoption or rejection of telework practices. Additionally, it details the progression from adopter organizations to individual teleworkers and, ultimately, outlines the environmental impacts attributed to teleworkers.

2.2.1. From Potential Adopter Firms to Potential Evaluators

The structure of the model, from “Potential firms” to “Potential Evaluators”, represents the decision process of evaluating telework in their operations and is the first step toward systemic adoption of telework. Companies that would evaluate telework implementation often rely heavily on the perceptions of their managers [8,56]. These perceptions are determined by a complex interaction between the perceived importance of telework to their operations, the perceived image of adopting telework, and the influence of social or subjective norms [7].

Perceived importance to operations refers to how managers assess the relevance of telework to their companies examining how it might affect the productivity, efficiency, costs, and overall operational processes [57]. This perception is often determined by the operational needs of the business, the nature of the work performed and the potential benefits that telework can bring, such as reduced overheads, increased flexibility, and access to a wider talent pool [7]. Perceived image refers to managers’ beliefs about the reputational and status-related payoffs of adoption, how stakeholders (employees, customers, investors, the public) will view the organization if it adopts telework [8]. Telework may, for example, signal innovativeness, flexibility, or social responsibility in settings where environmental sustainability and work–life balance are valued [43]. By contrast, social/subjective norms refer to external expectations and prevailing practices that managers perceive in their reference environment, including the norms within their sector, region, and professional networks; they capture the pressure to conform to what peer organizations and society at large are doing [8,58]. These norms include the prevalence of telework policies among comparable firms, the degree of acceptance among colleagues and units, and broader societal views on telework. In the model (Figure 1), perceived image is operationalized as an internal, reputation-oriented belief held by managers about how adoption reflects on their organization (a TAM-related evaluative judgment), whereas social effect/subjective norms capture externally anchored, inter-organizational influence and conformity pressures (a diffusion-related driver).

The factors described above influence the “awareness” or receptivity of an employer forming a causal relationship in decision-making, as a manager with positive perceptions (image and social pressure) is likely to be more open to consider and potentially implement telework [59]. Furthermore, it is important to note that a manager’s previous experience also play an important role in this decision-making process [8,60], as managers who have had successful experiences with telework in the past are likely to be more familiar with, and have more positive perceptions or fewer barriers towards, the possibility of evaluate telework and be more open to consider implementing telework in their area or company, as they may have a more realistic understanding of the benefits and challenges of telework and be better equipped to make informed decisions. The decision to evaluate telework implementation is a complex process that involves understanding these dynamics, companies can better navigate the decision-making process and make choices that fit their operational needs, company image, social norms, and management experiences [61,62].

The rate at which potential companies become potential evaluators of telework is influenced by both external and internal factors acting on potential adopters. External factors may include prevailing market conditions, government regulations or social trends, while internal factors may include elements such as company experience, capacity, and expertise [63,64]. This familiarity encompasses their understanding of the concept as well as their first-hand experience and comfort in using the innovation, workflows and practices associated with telework, as greater familiarity often leads to higher adoption rates by alleviating apprehensions, reducing uncertainties, and demonstrating the tangible benefits of telework [65,66]. In addition, the sensitization effect, a process in which repeated exposure to stimuli, such as awareness campaigns or managerial communications, increases responsiveness and adoption likelihood; unlike habituation, where repetition reduces attention, sensitization amplifies salience and reinforces favorable responses [67,68]. In the context of telework, sustained reinforcement through information flows and organizational practices can lower resistance and accelerate diffusion [44,47].

The concept of feedback loops was introduced as its equilibrium stabilize the system by resisting change, while reinforcing feedback loops amplify change and drive growth or decline. In the context of telework adoption, a potential equilibrium loop could be the learning curve and initial resistance that slows the rate of adoption. Conversely, a potential reinforcing loop could be the voice-to-voice effect among employees in an adopting organization, where the positive experiences of early adopters encourage more potential adopters or other employees to become testers and ultimately adopters [45].

Negative perceptions associated with telework play a crucial role in its adoption. Intrinsic motivations and prior knowledge of the organization, especially if managers perceive telework as irrelevant to their operations or if they had unsatisfactory experiences previously. If organizations feel that telework does not contribute significantly to their operations, they are less likely to try it, even during circumstances that favor remote working, such as the global pan-demic due to COVID-19. Although organizations are increasingly exposed to telework, especially due to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it does not necessarily guarantee that they are willing to evaluate and accept it [69]. The second source of negativity arises during the evaluation phase of the innovation, when they may anticipate detrimental consequences (perceived risk or stress on the part of managers), fostering dissatisfaction that may influence their adoption intentions [70,71].

Managers of companies assessing the feasibility of telework, converges on main outcomes: adoption, where a certain number of companies whose adoption depends on their managers, a certain number of these organizations become adopters of telework, implementing it and making it part of their routine working practices, as part of their operating model, while others reject it [8,60]. The decision to implement telework within companies is influenced by auxiliary variables based on the attitudes of managers. These include perceived risks, the intention to adopt telework, satisfaction levels with telework adoption in different areas of the company, the perceived usefulness and ease of telework, as well as the self-efficacy of employees in managing telework [8,36]. Flow variables represent the directional movement of firms in the process, accounting for firms that decide to adopt telework (adopters) and those that decide not to (rejection). Constant variables such as self-efficacy, which is related to employee training and employee knowledge of ICTs, are a factor that tends to be stable within an organization, but influences its predisposition towards telework; while these variables do not directly dictate whether a company adopts or rejects telework, they shape the general receptiveness of managers to how easy it is to implement telework in their workforce, and indeed of the organization to the idea [8,42].

Figure 2 details an observed reinforcement loop linked to the intention and actual adoption of telework within an organization, a loop associated with “User perception of information system quality and system usage adjustment loop”, works through a dynamic and reciprocal relationship between user satisfaction, system usage and perception of system quality, where the underlying premise of this loop is that the user’s willingness to employ a specific information system is directly proportional to their satisfaction with that system [72]. This correlation suggests that an increase in system usage corresponds to higher user satisfaction, where this higher level of satisfaction in turn influences users’ perception of the usefulness and ease of use of the system. As users begin to perceive the system as more beneficial and easier to use, their willingness to use it is amplified, thus reinforcing the loop.

In the context of telework, the behavioral intention to use telework is governed by two main elements: its perceived ease of use and its perceived usefulness; likewise, these perceptions can be influenced by a change in views or experiences by managers, e.g., when managers reassess and recognize the importance of telework to their operations, their enhanced perception of teleworks usefulness can spread across different organizations, this can further amplify the intention to adopt telework [42]. These intentions are particularly affected by the usefulness and ease of use of telework but are also affected by perceived quality. Managerial satisfaction can be measured in several dimensions, such as operational effectiveness, productivity improvement and demonstrability of results [66,73]. This feedback loop underlines the role of positive experiences and perceptions in catalyzing the adoption of telework. It illustrates how the cycle of increased perceived quality of outcomes, improved perceptions, and increased intention to use, can lead to greater acceptance and implementation of telework [8,74]. This suggests that strategies to boost telework adoption should consider these dynamics and seek ways to foster positive experiences and perceptions of the quality of the system by managers or decision-makers.

Perceived risk by managers has a negative effect on adoption, as it is mediated by the perceived loss of managerial control and the stress of not having their employees on the company premises during working hours [75]. In turn, the perceived self-efficacy of their work team has an inverse effect on perceived risk, the higher the perceived self-efficacy, the lower the perceived risk, as perceived self-efficacy is explained by the perception that the team members are empowered by the position; in addition, perceived self-efficacy is also mediated by the perception of managers that the employees are ICT literate, which would imply that could handle with getting work, meetings, and different tasks done [8,76,77,78]. This aligns with the theory that managerial perceptions of control and risk management play a key role in determining the adoption of new technologies or work arrangements, these perceptions can create a psychological barrier to telework adoption as managers are faced with changing traditional work paradigms and the perceived threat to established operational and management controls [57].

2.2.2. From Adopter Organizations to Teleworkers

Decisions regarding the acceptance of telework in an organization are usually associated with the top management of the organization [60]. However, when this decision is made, several departments or units in the organization become potential adopters of telework, reflecting a diverse internal ecosystem with different receptivity to telework [77,79]. These potential adopters, considered as a “level variable” as shown in Figure 2, have the option to individually assess and adopt or reject telework. This group of evaluators is then faced with the choice of adopting or rejecting telework (when it is optional), where the adoption of telework (TW) depends on the rate of adoption. Thus, the rate of adoption of telework within a social system (the company) depends on factors such as the perceived benefits of the innovation, the complexity of the innovation, the possibility of testing the innovation before full implementation, and the visibility of the results of the innovation [47]. In addition, the perceived benefits, advantages or potential improvements that the adoption of telework can bring to the individual, such as cost savings, increased flexibility, improved work–life balance, and possible productivity improvements are important factors [7]. On the other hand, the perceived complexity of the innovation associated with the use of telework can significantly influence its adoption. If telework is seen as technologically complex or difficult to integrate into existing work processes, it can hinder individual adoption [80].

2.2.3. From Teleworkers to Their Environmental Impacts

Telework has the potential to reduce emissions and energy consumption by decreasing commuting and office energy use, though it may also increase residential energy demands due to extended home occupancy, with the variability in its net environmental impact influenced by factors such as geographical location, local climate conditions, energy efficiency of buildings, and the availability of renewable energy sources [9,20,21,22,23,81]. In addition, teleworking can stimulate more energy-conscious behavior, such as more efficient heating and cooling practices at home, further contributing to these savings [82]. Environmental impacts associated with the number workers adopting telework are shown in Figure 2 as avoided power consumption (PC) and CO2 emissions, based available estimations for Colombia that suggest a net reduction trend [83,84]. These reductions derive mainly from a decrease in commuting-related emissions and less traffic [83,84].

2.3. Model Formulation

The model is composed of influential variables related to the adoption rate and its environmental impacts. System dynamics were used to illustrate potential behaviors. These variables are conceptualized and ranked by their importance and weight based on their relationships within the model. Parameters for the model are provided in subsequent tables, which group the variables and their respective formulations. It includes their definitions, units and formulae, together with the sources of assumptions and adaptations as well as variables used in the baseline simulation, together with their estimated values. Table 1 and Table 2 provide detailed information on the stock and flow and auxiliary variables in the model. The coefficients used in formulas for energy consumption and CO2 equivalent calculations already incorporate local adjustments to reflect the country’s transportation structure, fuel mix, commuting patterns, and average trip distances, based on previous studies including origin–destination survey and national statistics [83]. Therefore, rather than using international averages, the values applied in this study are context-specific parameters adjusted to Colombian mobility and energy intensity conditions, ensuring consistency in the projected savings. Table 3 presents the formulation of flows and auxiliary variables of the model and Table 4 and Table 5 present the influencing factors and constant parameters, respectively, where data or variable associations specifically relating to Colombia were lacking, it was used information from other studies.

Table 1.

Flows and auxiliary variables of the model.

Table 2.

Formulations of the stock variables of the model.

Table 3.

Formulation of flows and auxiliary variables of the model.

Table 4.

Formulation of influencing factors of the model.

Table 5.

Constant parameters used for the simulation of the base model.

2.4. Simulation of Scenarios

The impacts that specific variables have on the model and its outcomes were assessed in the simulation of three scenarios (see Table 6), considering the main factors that could be intervened in real conditions for the adoption of teleworking. Each of the scenarios focuses on few variables in the model, to establish its sensitivity and the clear connection between the change in parameters and the emerging behavior of the model. The factors considered in Scenario 1 were the “social effect”, presumably how society and government influence managers, and the “perceived image”, related to how people perceive organizations that use telework. Scenario 2 assessed the effects of variations on perceived average quality, self-efficacy, and perceived risk, which considerably influence managers’ attitudes, and finally, in scenario 3, the model was evaluated under the change in the adoption decision.

Table 6.

Description of the three different scenarios as simulation experiments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Base Model

3.1.1. Adopters, Evaluating Organizations to Adopting or Rejecting Organizations and Rejectors

A demonstration of how the simulated model behaves for enterprises is shown in Figure 3. It provides a graphical representation of the adoption of telework in Colombia over a period of 20 years, starting in 2012, the first year in which official reports of telework in Colombia were published after the implementation of the law 1221 of 2008 Government of Colombia. In this model, the adoption of telework follows a sigmoidal growth and reaches a saturation point on time. However, the population change in both organizations and individuals in Colombia over the period 2012 to 2032 was omitted for simplification purposes of model, based on the reasoning that the model is intended to provide a qualitative interpretation of the dynamics of the system [45]. Figure 3 shows the gradual spread of telework among Colombian enterprises and a rapid reduction in the stock in the variable “Potential Firms”. In the year 2021, telework is almost universally known, in contrast with the data regarding the number of enterprises that had adopted telework [46]. External influences, such as initiatives to raise awareness of the importance of telework in enterprises, the social effect brought about by initiatives, incentives and other social and external variables that exert pressure on this level variable, are the main mechanisms facilitating this initial attrition of the stock of “Potential Firms” [45]. Each year, companies become familiar with telework, increasing the number of “Potential Evaluators”, whose first experiences increase the relevance of telework by amplifying the “potential evaluators from familiarity”, and these experiences increase the likelihood of interaction with “Potential Firms”. The role of this internal influence, also known as experiential impact, intensifies as time progresses and assumes leadership as the primary adoption mechanism [42,45]. This dynamic facilitates a more rapid reduction in the number of “Potential Evaluators” from 2015 onwards. However, as the pool of “Potential Firms” decreases by 2021, both mechanisms external and internal influence reduce their effectiveness due to the scarcity of new “Potential Firms” in the system.

Figure 3.

Behavior of the baseline implementation model on the adoption of telework in Colombia by organizations (Firms) between 2012 and 2032.

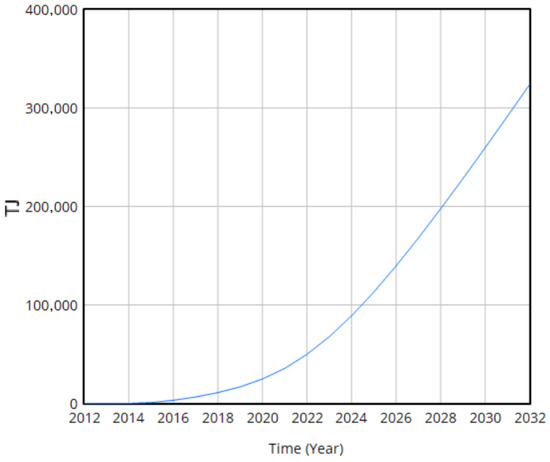

3.1.2. Teleworkers

The number of teleworkers from 2012 to 2032 is shown in Figure 4. It illustrates the baseline trajectory of telework adoption in Colombia between 2012 and 2032, showing a classic S-shaped diffusion pattern: slow initial growth up to 2018, a marked acceleration between 2019 and 2025 as organizational familiarity and external drivers strengthen, and a gradual flattening thereafter as adoption approaches saturation, with the model estimating close to 1.61 million teleworkers by 2032. The behavior is explained by the adoption rate of telework by organizations and the average number of employees (people/year) whose positions and functions would be suitable for teleworking based on the modeling assumptions in the simulation [61]. In addition, “Teleworking Eligible employees” (Figure 2) decreased over time because a portion of them decide to evaluate telework and adopt it as their individual working practice (people/year), it contributes to the flow from potential to actual teleworkers, and as consequence, the simulation in Figure 4 shows a smoothed increasing trend, which stabilizes from 2026, where it does not depend on the new adopting organizations, but on the internal diffusion of telework in them.

Figure 4.

Behavior of the baseline implementation model on the number of teleworkers in Colombia (millions of people) between 2012 and 2032.

3.1.3. Environmental Impacts

Environmental contributions of telework are highly valued in companies in accordance with sustainable development goals. The adoption of telework has a notable impact on energy consumption in the country (Figure 5). It shows the baseline projection of avoided energy consumption associated with telework adoption in Colombia between 2012 and 2032. The curve starts with negligible savings during the early years but begins to rise noticeably after 2018, reflecting the acceleration in telework adoption. From 2020 onwards, avoided energy consumption grows exponentially, surpassing 168,000 TJ by 2027. This trend highlights the cumulative effect of widespread telework adoption, where incremental savings per worker aggregate into substantial national-level energy reductions over time.

Figure 5.

Base model of avoided energy consumption (TJ) by telework adoption in organizations in Colombia between 2012 and 2032.

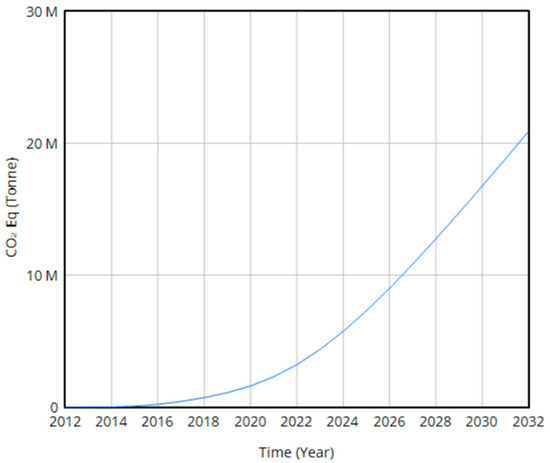

The elimination of commuting decreases energy expenditure on transport, which quantification of energy demand is explained by fuel type, type of vehicle used, distances saved and energy intensity or efficiency, and their calculations used the characterization of the vehicle fleet is based on emission inventory data and the total share in passenger transport, based on the origin/destination survey of the metropolitan area of the Aburrá valley [83], resulting in 0.02 TJ per people/year and a total impact, according to the number of teleworkers expected by 2032 and their growth, the impact on the Colombian energy system would be approximately 322,000 TJ since 2012, and by 2032 would correspond to a saving of 1.55% per year according to energy demand projections [88].

An individual who teleworks would have an impact on the reduction in the carbon footprint of approximately 1.29 t of CO2 equivalent per year [83]. Figure 6 illustrates the baseline projection of CO2 equivalent emissions avoided in Colombia as a result of telework adoption from 2012 to 2032. The curve shows minimal reductions in the early years, reflecting the limited penetration of telework before 2018, as adoption accelerates after 2020, avoided emissions increase steadily, reaching a marked inflection around 2025. From this point onward, the trajectory becomes steeper, highlighting the cumulative impact of reduced commuting-related transport emissions, where by 2032, the model estimates that avoided emissions could exceed 20.9 t of CO2 equivalent, under-scoring the potential contribution of telework policies to national mitigation strategies in the transport sector, corresponding to 2% per year, according to projections of CO2 equivalent emissions [88].

Figure 6.

Base model of equivalent CO2 avoided emissions in Colombia by telework adoption in organizations associated with transport sector between 2012 and 2032.

The environmental impact of teleworking extends beyond simple reductions in transportation emissions to broader systemic implications on urban energy systems. In Medellín, combining telework with mass transit improvements has been projected to avoid approximately 5.65 t of CO2 by 2040, representing a 9.4% reduction in emissions, alongside an energy savings of 86,576 TJ [83]. These results are conservative relative to city-specific estimates [84], reporting larger short-term drops during COVID-19 restrictions, and consistent with Latin American scenario work where telework contributes modest but non-trivial gains when combined with broader mobility and energy policies [12].

Evidence from other Latin American countries provides additional insights into the variability of these impacts. In Mexico City, telework has been identified as a promising strategy to reduce congestion, fossil fuel consumption, and associated emissions, complementing urban mobility initiatives [89], while more recent discrete choice analyses highlight the value workers place on reduced commuting time, with indirect benefits for energy use and air quality [90]. In Costa Rica, national decarbonization scenarios estimate that digitalization and telework, combined with transport electrification and modal shifts, could lower primary energy demand by up to 25% by 2050 [91]. Likewise, Ecuador’s long-term energy transition strategies emphasize flexible work as a mechanism to decrease fossil fuel dependence [92], and evidence from Brazil indicates that sustained telework adoption may operate as a demand management policy, mitigating congestion and vehicle emissions if adequately incentivized [93]. In contrast, studies in other regions like the case of Beijing, demonstrated a 7.05% reduction in annual transport-related carbon emissions through teleworking, with specific industries such as ICT and professional services showing the greatest potential for reductions [21]. In Canada, telework adoption rose from 7.4% pre-pandemic to nearly 20% during the crisis, stabilizing near 17% under “ideal” conditions [1]. Yet much of this shift substituted public transit rather than private car use, raising doubts about long-term environmental benefits and highlighting equity concerns in its persistence In this context, although Colombia’s projected 2% reduction in transport-related CO2 emissions may appear modest, it is consistent with regional experiences, where structural inequalities, energy systems, and institutional capacities determine both the scale and distribution of environmental benefits.

Reduction in green-house gas emissions is related to the avoided transport by the adoption of telework by organizations. However, challenges persist in achieving net environmental benefits due to the redistribution of energy demands. While teleworking reduces office-related energy consumption, increased residential energy use during work hours presents a tradeoff. Studies suggest that residential energy consumption can increase by up to 6.1% due to prolonged heating, cooling, and electronics usage, partially offsetting transportation-related savings [22]. Energy-efficient home systems could mitigate this effect but remain underutilized in many regions. Moreover, structural inefficiencies in energy and transport systems in Latin America exacerbate these challenges, necessitating targeted infrastructure upgrades and public incentives [94]. The cumulative impact of telework on emissions and energy use also depends on its scalability across industries and regions. A systematic review of telework identified the uneven distribution of its adoption, with rural and economically disadvantaged areas often lagging behind due to limited access to ICT infrastructure [3]. This disparity could hinder Colombia’s ability to fully realize the environmental benefits of telework. Furthermore, the increase in residential energy demands during teleworking, when coupled with low energy efficiency in homes, risks creating a rebound effect that diminishes net gains. Strategic interventions, such as those proposed in Medellín’s Master Plan, provide a blueprint for integrating telework with broader urban planning and energy policies to reduce emissions while addressing equity and infrastructural gaps [83].

3.2. Scenario Analysis

The simulation results of three policy scenarios (E1–E3) compared with the baseline are presented in Figure 7. Results illustrate how external campaigns, managerial attitudes, and familiarity influence the diffusion of telework in Colombia highlighting how different policy levers shape both adoption patterns and their environmental impacts over the 2012–2032 horizon. Figure 7a–c track the dynamics of firms, potential, adopting, and rejecting, while Figure 7d–f show the corresponding effects on teleworkers, avoided energy consumption, and avoided CO2 emissions.

Figure 7.

Different scenarios for potential companies, adopters, rejecting firms, number of teleworkers, avoided energy consumption and emissions. (a) Potential firms: total number of firms that could eventually adopt telework under each scenario; (b) Adopting firms: firms that have adopted telework over time; (c) Rejecting firms: firms that choose not to adopt telework.; (d) Teleworkers: number of workers who shift to telework as a consequence of firm adoption; (e) Avoided energy consumption: estimated amount of energy saved due to the increase in teleworking; (f) Avoided equivalent CO2: avoided greenhouse gas emissions resulting from reduced commuting and on-site energy use. Colored lines E1–3 represent scenarios 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

In Scenario 1 the model indicates that although the sensitivity of individual drivers is moderate, each factor contributes meaningfully to the adoption of telework. Governmental campaigns and external perceptions (Figure 7a–c) play a visible role by accelerating the evaluation process, leading to a faster reduction in potential firms and an earlier, but modest, increase in adopting firms. The effect of familiarity, based on managers’ prior experiences with telework, reinforces this process by lowering initial resistance and encouraging organizations to test its feasibility.

However, the overall adoption rates remain comparatively low across the period (Figure 7d–f). The limited outcomes are largely explained by weak managerial receptivity toward perceived ease of use and perceived utility, which directly reduces the likelihood of adoption and restricts large-scale diffusion; as a result, the environmental benefits are also constrained, with only incremental improvements in avoided energy consumption and CO2 emissions compared to the baseline. Thus, scenario 1 highlights that awareness and familiarization campaigns can accelerate evaluation, but without shifts in attitudes toward usefulness and ease of use, their impact on long-term adoption and environmental outcomes remains limited.

In scenario 2 the effects of perceived quality, self-efficacy, and perceived risk on the behavior of the model were analyzed, and the results indicate a high sensitivity of adoption to these three factors. Compared to the baseline, Figure 7a shows a faster reduction in potential firms, while Figure 7b,c display a more pronounced increase in adopting firms and a smaller share of rejecting firms. The model assumes that improvements in the perceived quality of telecommuting outcomes would be gradual over the period 2012–2032, reinforcing managers’ confidence and driving a faster adoption trajectory. This trend becomes even more accentuated when quality improves immediately, leading to a larger cumulative adoption of telecommuting by 2032. Managers’ perceptions of employee self-efficacy and lower perceived risk are central to this process, as organizations are expected to establish policies and safeguards to protect information, guarantee data security through contractual arrangements and specialized software, and maintain managerial oversight of operations [95]. At the same time, employees are anticipated to acquire greater ICT skills and demonstrate empowerment and self-sufficiency, which enhance their self-efficacy and, in turn, increase managers’ confidence in telecommuting. Under such favorable conditions, performance metrics such as productivity, cost control, and operational efficiency would improve, reinforcing the perceived quality of telecommuting outcomes.

Figure 7d–f further illustrate that higher levels of adoption translate into greater numbers of teleworkers and larger environmental benefits, with more substantial increases in avoided energy consumption and avoided CO2 emissions compared to Scenario 1. However, these outcomes depend heavily on sustaining positive perceptions: if managers repeatedly experience poor-quality telecommuting conditions, rejection could accumulate, with organizations becoming increasingly reluctant to re-adopt telecommuting even if conditions improve later [96].

This risk underlines the importance of carefully planned and well-managed implementations, as highlighted by the literature, premature adoption without adequate quality standards or structural readiness may lead to long-term resistance and reduced willingness to adopt telecommuting in the future [8,97]. Scenario 2 therefore stresses that improving perceptions of quality, reducing perceived risks, and enhancing employee self-efficacy are urgent priorities for organizations wishing to accelerate adoption, ensuring effective systems and managerial confidence from the outset is essential to achieve sustainable growth in telecommuting adoption and to maximize its contribution to environmental goals.

The impact of altering the variable likelihood of adopting telecommuting was examined in Scenario 3. The concept of adoption likelihood, widely discussed in the literature, is generally measured through the willingness or disposition of individuals to adopt tele-commuting, with reported quantitative values varying considerably depending on the metrics employed [8,36,42]. For the simulation, the value of this variable was increased by 0.5 relative to the baseline and the results were compared not only with the base run but also with Scenario 2, which assumed immediate improvements in perceived quality, higher self-efficacy, and lower perceived risk. Figure 7a–c show that this adjustment leads to a faster reduction in potential firms and a moderate rise in adopting firms, although the increase is not as large as in Scenario 2, where perceptions of quality and risk were also altered.

Figure 7d–f illustrate that while higher likelihood of adoption generates incremental gains in the number of teleworkers, avoided energy consumption, and avoided CO2 emissions, the effect remains limited if not combined with improvements in perceived quality, self-efficacy, and risk reduction. The findings underscore that managerial attitudes toward telework, shaped by perceived utility and ease of use, directly influence the adoption trajectory. Moreover, the scenario highlights the importance of past experiences: established beliefs tend to evolve gradually, but immediate positive reinforcements such as high-quality telecommuting outcomes, empowered employees with strong ICT skills, and reliable safeguards against operational risks can accelerate adoption and generate more substantial long-term impacts. Thus, Scenario 3 suggests that increasing willingness alone is insufficient; meaningful adoption gains require a comprehensive approach that couples favorable attitudes with structural improvements in quality and risk management.

During the COVID-19 period, Latin American countries experienced an abrupt surge in telework adoption, uncovering both latent capacity and structural constraints. A study across seven countries—including Colombia—showed that firms responded to containment measures by rapidly shifting to remote work, but in the post-pandemic stage trajectories diverged according to labor market structure and institutional readiness [12,98]. In contrast, our Colombia-based System Dynamics scenarios project a more gradual diffusion, constrained by organizational inertia, sectoral heterogeneity, and infrastructural limits. While empirical data from the pandemic represent upper-bound impulses under crisis conditions, our modeling attempts to reflect plausible trajectories in “normalization” phases. Thus, comparing the COVID shock behavior with our modeled scenarios offers insight into the inertia and resistance to sustained telework adoption beyond emergency conditions.

Studies across Latin America reinforce this interpretation by documenting both opportunities and limitations of telework adoption. In Brazil, the emergency shift to telework during 2020 substantially altered travel behavior, with lingering effects in 2022 that reflected regional and economic inequalities in adoption capacity [93]. In Chile, household-level evidence showed that confinement increased greenhouse gas emissions from domestic energy use by 8–23%, emphasizing the rebound effects that must be considered in evaluating environmental impacts of telework [99]. Mexico provides another relevant perspective: pre-pandemic surveys already identified telework as a promising mobility strategy for Mexico City [89], while more recent discrete choice experiments confirmed that workers were willing to trade salary reductions for hybrid arrangements, underscoring the role of cost–benefit dynamics in adoption [90]. These regional experiences indicate that while the pandemic temporarily accelerated adoption beyond historical trends, sustained diffusion in Colombia and the wider region is shaped by institutional readiness, infrastructural capacity, and sector-specific dynamics—factors captured in the analysis of scenarios.

4. Practical Implications

The use of System Dynamics models in studying teleworking adoption remains limited, with notable exceptions addressing its impact on transportation systems [69,100,101]. This research advances these efforts by applying the Bass Diffusion Model to analyze teleworking adoption as a dynamic organizational innovation [59]. The proposed model integrates managerial perspectives, focusing on variables such as perceived utility, ease of use, and managerial attitudes, while accounting for intrinsic factors like perceived risks and management control. This approach enables a detailed examination of adoption outcomes over time, offering insights into cause-effect relationships within organizations [45].

The model’s structure emphasizes the role of individual managerial decisions in driving telework adoption. Decisions to evaluate teleworking often hinge on managerial perceptions of its benefits and challenges, highlighting the importance of fostering positive attitudes through organizational support and resources [28,85]. Positive experiences, bolstered by continuous training and access to high-quality collaboration tools, enhance perceptions of teleworking’s value. These improvements mitigate concerns about team performance and control, fostering broader acceptance among managers and employees.

Flexibility in policies further supports teleworking adoption by allowing employees to tailor their work arrangements to their needs, such as part-time telework options. Clear and consistent policies that emphasize work–life balance can increase adoption rates while demonstrating tangible benefits for employees’ quality of life. Managers’ commitment to these strategies is critical to their success [102]. Regular feedback loops can identify challenges and opportunities for improvement, ensuring policies remain adaptive to changing organizational needs [103]. This iterative process supports the continuous improvement of telework strategies, helping organizations and policymakers fine-tune policies to optimize outcomes.

The SD model’s findings indicate that teleworking adoption rates in Colombia remain low due to current practices and limited organizational support. However, the model demonstrates its potential as a tool for predicting adoption dynamics and identifying barriers to implementation. By simulating long-term effects, SD models enable managers and policymakers to develop informed strategies that optimize teleworking benefits, such as reducing commuting-related emissions and enhancing organizational sustainability applications of this model should incorporate granular organizational data to enhance accuracy and applicability [104]. As telework evolves, SD models can serve as critical tools for scenario planning and decision-making. Policymakers and managers can leverage these models to simulate the impacts of interventions, guiding the development of effective telework policies that align with broader sustainability goals. Finally, the SD model not only aids in understanding the dynamics of teleworking adoption but also serves as a framework for developing policies that address key challenges. By focusing on high-potential sectors and leveraging positive managerial perceptions, telework adoption can be effectively scaled in Colombia, particularly in cities like Bogotá and Medellín, where its benefits are most pronounced [22,83]. These efforts must be complemented by targeted incentives, infrastructure improvements, and continuous feedback to ensure sustainable and equitable outcomes.

Telework has consolidated as a form of labor organization in several Latin American countries generating significant impacts on both organizational productivity and workers’ quality of life, as well as on management policies. Regional studies show positive effects on productivity, especially when companies and employees already have digital readiness, goals, and defined metrics [105]. However, they also reveal persistent obstacles related to technological infrastructure, socioeconomic inequalities, and the absence of clear regulation. To ensure that the adoption of telework takes place in a sustainable and inclusive manner, it is necessary to formulate guidelines that guarantee labor rights, establish clear parameters for working hours, compensation for equipment and energy costs, and personal data protection, as defined in Brazilian legislation, Law No. 14.442/2022 [106]. Furthermore, it is imperative to implement digital inclusion measures that expand access to technological infrastructure and professional training, to reduce territorial and gender gaps [11]. Policies aimed at health and occupational well-being are also required, considering ergonomics, the prevention of psychosocial risks, and the guarantee of the right to disconnect, in order to preserve boundaries between personal and professional life.

Several challenges have been identified in Colombia’s telework ecosystem, such as limited organizational culture change, uneven sectoral adoption, and gaps in energy efficiency practices, which could be addressed with strategies from the present study and aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). First, municipal governments should complement telework promotion with incentives for companies to implement formal telework policies (ODS 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth) and invest in digital infrastructure that ensures equitable access across territories (ODS 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). Second, targeted subsidies or tax credits could encourage households to adopt energy-efficient appliances and ICT equipment, mitigating rebound effects from residential energy use (ODS 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, ODS 13: Climate Action). Third, companies should integrate telework into their sustainability strategies by monitoring productivity, mobility savings, and carbon footprint indicators, aligned with national decarbonization goals (ODS 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, ODS 12: Responsible Consumption and Production).

5. Limitations and Future Research

This study presents certain limitations that provide valuable opportunities for future research. First, while it models telework adoption at the organizational level using government data on telework penetration rates, it does not address the internal adoption process within organizations or the individual-level variables influencing telework uptake. Future studies could delve deeper into how individual employees adopt telework when their job roles permit remote work, focusing on psychological and contextual factors influencing their decisions. Second, the environmental impacts of telework on energy consumption were analyzed at an aggregate level, emphasizing reductions in transport-related CO2 emissions. However, future research could investigate the redistribution of energy demand, such as the decreased energy use in offices and the corresponding increase in residential energy consumption. Understanding these shifts could reveal critical pivot points for maximizing energy efficiency and minimizing carbon footprints in both organizational and residential contexts. System Dynamics models inherently aggregate individual behaviors, treating them as a collective. While this approach effectively captures dynamic complexity, it overlooks individual differences. Segregating individuals and organizations based on sociodemographic or operational characteristics could refine the model’s predictive accuracy. For instance, agent-based modeling could complement SD models to explore individual behaviors, interactions, and the voluntariness of telework adoption, which remains understudied [57]. Lastly, the frequency and intensity of telework significantly influence its sustainability benefits. Full-time teleworkers generate more pronounced environmental and organizational benefits than part-time teleworkers due to reduced commuting and office resource usage [36]. Future research should account for these variations to better inform policies promoting telework as a sustainable practice.

The joint application of TAM and BDM to analyze organizational telework adoption in emerging economies remains scarce, despite their extensive individual use in innovation studies. At the same time, this limitation provides a clear pathway for future research: individual-level analyses could build on TAM to explore psychological and contextual factors driving employee telework adoption, while diffusion-based approaches could be extended to examine heterogeneity in adoption across sectors, firm sizes, or sociodemographic groups. Moreover, future studies could combine System Dynamics and agent-based modeling to overcome aggregation biases, capturing both organizational-level dynamics and individual decision-making processes. This line of inquiry would enhance predictive accuracy and generate insights into the frequency, intensity, and sustainability impacts of telework adoption, particularly in contexts where cultural, institutional, and infrastructural factors play a decisive role.

A relevant extension of our study is to incorporate the concept of home energy rebound in order to better estimate the net energy impacts of telework. In practice, household energy use during teleworking days does not mirror office energy demand but reflects a set of behavioral adjustments. For instance, in Colombia many households rely on small electric water heaters for bathing, but survey evidence suggests that on teleworking days some individuals reduce bathing frequency, which may lower energy demand, similarly, ironing and laundry loads can decrease due to reduced social requirements for formal clothing. At the same time, other categories of household energy consumption increase. Cooking shifts from company canteens or restaurants, where food preparation benefits from economies of scale, to individual households, raising per capita energy intensity in meal preparation [101,107,108].

Additional rebound mechanisms emerge in services such as lighting, internet, and ICTs use, which are distributed among many employees in centralized offices but concentrated at the individual household level when working from home, while some high-income households may experience increases in air-conditioning or heating, most Colombian households lack such appliances, meaning that telework does not systematically raise HVAC demand. Thus, the balance of these effects can yield both reductions (e.g., less laundry or ironing) and increment (e.g., more cooking or ICTs use) in home energy demand. In future research, our system dynamics model could be extended to include such direct rebound effects, providing policymakers with more realistic estimates of the net energy and CO2 impacts of telework [109,110,111].

Consistent with accessibility-modeling guidance, the scenarios are designed to probe parameter sensitivity and the possibility of threshold behavior, recognizing that marginal increases in adoption rates can propagate through feedbacks to yield disproportionate changes in avoided energy consumption and transport-related CO2, future work could incorporate formal sensitivity analysis and threshold testing for adoption-rate and impact coefficients to assess robustness of environmental outcomes [112,113]. A key limitation of the calibration process is that only five data points were available from national telework penetration surveys conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020) [46] and a study on transport related CO2 emissions and power consumption. While these observations provided a valuable basis to anchor the adoption trajectory, the scarcity of data restricts the precision of parameter estimation and a more detailed validation of the model. As a result, the calibrated figures should be interpreted as indicative estimates within a range of uncertainty rather than exact predictions. The contribution of this study is to propose and test a modeling structure that can be progressively updated and validated as new real-world data become available. Further calibration can be achieved with a new national telework survey and firm/employee datasets that quantify both the reduction in office energy use and the potential increase in household consumption. This will require an SD adjustment, building on Figure 2, to include a household-energy stock linked to the number of teleworkers and to incorporate this term into the net energy-savings calculation. With these extensions, the model will support predictive assessment, formal sensitivity analysis, and renewed scenario projections of adoption and environmental impacts. In future work, we recommend the establishment of a telework observatory in Colombia that systematically collects firm-level and household-level information. For applications in other countries, we recommend collecting comparable household datasets and recalibrating parameters to local behavioral patterns and energy mixes before drawing policy conclusions.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that telework has significant potential to reduce transport-related CO2 emissions and energy demand in Colombia, but its full impact is constrained by the slow adoption rates driven by internal organizational factors. Using an enhanced System Dynamics model based on the Technology Acceptance Model and the Bass Diffusion Model, this research provides a dynamic understanding of telework adoption processes and their environmental effects. The findings confirm the hypothesis that transport-related emissions and energy consumption may not achieve expected reductions without addressing key organizational barriers, such as managerial perceptions and attitudes. The model highlights how these internal factors influence adoption rates and demonstrates the critical role of decision-makers in driving sustainable practices. It is important to develop targeted policies and organizational strategies that address these barriers to unlock telework’s potential as a tool for environmental and energy sustainability in the context of Latin American cities. Finally, the projections presented here should be interpreted in light of the moderate robustness and limited quantitative scope of the model, resulting from the scarce availability of empirical data. Strengthening official datasets and promoting access to enterprise-level records will be essential for refining future model applications and for providing stronger evidence to support sustainable public policy design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-C., S.B.-B. and I.A.M.-R.; methodology, A.S.-C.; formal analysis, J.L.G. and H.R.-R.; investigation, A.S.-C.; data curation, A.S.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.L.G., I.A.M.-R. and H.R.-R.; supervision, S.B.-B.; validation, S.B.-B.; project administration, S.B.-B. and I.A.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BDM | Bass Diffusion Model |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| ICTs | Information and communication technologies |

| SD | System Dynamics |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

References

- Sweet, M.; Scott, D.M. Insights into the Future of Telework in Canada: Modeling the Trajectory of Telework across a Pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J.M. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1975, 23, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. Telework: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruch, Y. The Status of Research on Teleworking and an Agenda for Future Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2001, 3, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing More with Less? Flexible Working Practices and the Intensification of Work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.C.; Gschwind, L. Three Generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R)Evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. New Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-C, A.; Montoya, R.I.A.; Valencia, A.J.A. The Attitude of Managers toward Telework, Why Is It so Difficult to Adopt It in Organizations? Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojovic, D.; Benavides, J.; Soret, A. What We Can Learn from Birdsong: Mainstreaming Teleworking in a Post-Pandemic World. Earth Syst. Gov. 2020, 5, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, C.; Gal, P.; Leidecker, T.; Losma, F.; Nicoletti, G. The Role of Telework for Productivity during and Post-COVID-19: Results from an OECD Survey among Managers and Workers. In OECD Productivity Working Papers; OECD ILibrary: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OIT. El Teletrabajo Durante la Pandemia de COVID-19 y Después de Ella; OIT: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1, ISBN 9789220330920. [Google Scholar]

- Maurizio, R. Desafíos y Oportunidades Del Teletrabajo En América Latina y El Caribe. Organ. Int. del Trab. 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/desafios-y-oportunidades-del-teletrabajo-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Ahrendt, D.; Mascherini, M. Living, Working and COVID-19: First Findings—April 2020. Eur. Found. Improv. Living Work. Cond. 2020, EF/20/058/, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Molano Vega, D.; Hoyos Turbay, M.C.; Restrepo Múnera, J.; López Gil, D.; Pardo Rueda, R.; Ríos Muñoz, J.N.; Bejarano Hernández, E.; Torres Matiz, A. Libro Blanco el ABC del Teletrabajo en Colombia. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/admon/files/empresas/ZW1wcmVzYV83Ng==/imagenes/4495/%20LIBRO%20BLANCO%20-%20TELETRABAJO.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- DANE. Encuesta Pulso Social. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/encuesta-pulso-social (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Morales, L.F. Crecimiento de La Ocupación Jalonado Por El Segmento no Asalariado y un Análisis Sobre el Teletrabajo en Colombia. Rep. Merc. Labor. Available online: https://repositorio.banrep.gov.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/06a645fd-fe48-48cb-86b4-ffc172339c9a/content (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- DANE. Encuesta Sobre Ambiente y Desempeño Institucional Nacional (EDI). Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/gobierno/encuesta-sobre-ambiente-y-desempeno-institucional-nacional-edi (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Moglia, M.; Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Telework, Hybrid Work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: Towards Policy Coherence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, K.E.; Mondal, A.; Batur, I.; Dirks, A.; Pendyala, R.M.; Bhat, C.R. An Investigation of Individual-Level Telework Arrangements in the COVID-Era. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 179, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dura, C.; Driga, I. The Dimensions of Sustainability Impact. Ann. Univ. Petrosani Econ. 2023, 23, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, N.; Long, Y. Assessing Carbon Reduction Benefits of Teleworking: A Case Study of Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepanta, F.; Sirati, M.; O’Brien, W. Sustainability of Telework: Systematic Quantification of the Impact of Teleworking on the Energy Use and Emissions of Offices and Homes. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, H.; Abdeen, A.; Papineau, M.; Simon, S.; Cruickshank, C.; O’Brien, W. New Insights on the Energy Impacts of Telework in Canada. Can. Public Policy 2021, 47, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, F.M.; Krishnan, T.V.; Jain, D.C. Why the Bass Model Fits without Decision Variables. Mark. Sci. 1994, 13, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, F.M. Comments on “A New Product Growth for Model Consumer Durables”. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, A.; Fogliano, V.; Luning, P.A. Modifying the Bass Diffusion Model to Study Adoption of Radical New Foods–The Case of Edible Insects in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavana, R.Y. Modeling the Environment: An Introduction to System Dynamics Models of Environmental Systems. Andrew Ford Island Press, Washington DC, 1999, viii + 401 pp. ISBN: 1-55963-601-7. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2003, 19, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Vilchez, J.J.; Jochem, P. Simulating Vehicle Fleet Composition: A Review of System Dynamics Models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Park, E. For Sustainable Development in the Transportation Sector: Determinants of Acceptance of Sustainable Transportation Using the Innovation Diffusion Theory and Technology Acceptance Model. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhirasasna, N.N.; Sahin, O. A System Dynamics Model for Renewable Energy Technology Adoption of the Hotel Sector. Renew. Energy 2021, 163, 1994–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.D.; Geels, F.W. Multi-System Dynamics and the Speed of Net-Zero Transitions: Identifying Causal Processes Related to Technologies, Actors, and Institutions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]