Abstract

This study explores the dynamic relationship between rural tourism and traditional architecture, emphasizing their joint role in cultural heritage preservation and sustainable development. Utilizing CiteSpace (6.3.R1) and VOSviewer (1.6.19) tools, this study analyzes 1356 publications from the Web of Science database and identifies three development stages: the initial stage (1996–2008), the growth stage (2009–2016), and the peak stage (2017–2024). The main findings highlight a focus on climate-adaptive design, community collaboration, and the integration of digital technologies in heritage preservation. Emerging topics, such as green building materials and virtual reality, have also gained increasing attention. Despite these advancements, limitations persist in terms of data diversity and the regional scope of research. Future studies should address how to balance heritage conservation with modernization needs, enhance interdisciplinary collaboration, and leverage digital tools to promote urban–rural interaction and ecological design.

1. Introduction

Rural tourism is promoted across all EU countries because of its socio-cultural, economic, spatial, and environmental contributions, as well as its positive impact on the development of vernacular architecture in rural areas [1]. Rural tourism is a type of tourism that takes place in rural areas, relying on local natural resources, cultural heritage, and traditional lifestyles. It provides visitors with opportunities for nature sightseeing, cultural experiences, and interactive activities. This tourism model includes activities such as farming, cultural heritage visits, and handicraft making. Its goal is to boost the rural economy while preserving the unique cultural and natural resources of the area [2]. According to related studies, rural tourism is not just a form of tourism but also an important tool for rural revitalization. It can attract visitors by developing rural resources and generate economic benefits for local communities [3].

Faced with the demands of modernization and rural tourism, traditional villages encounter particularly severe challenges. The rise in rural tourism is influenced by economic growth and improvements in living standards [4]. It promotes local economic development and enhances the exchange of resources and culture between urban and rural areas. However, this growth has also put pressure on the architecture and environment of traditional villages. Rural architecture refers to various buildings and structures in rural areas, including farmhouses, warehouses, religious buildings, and infrastructure related to agriculture or community activities. These buildings are often constructed using local materials, reflecting the unique cultural landscape and historical heritage of rural areas [5]. Rural architecture not only serves as a foundation for social life in rural areas but also embodies the cultural traditions and regional characteristics of the countryside. Studies suggest that protecting and properly utilizing rural architecture can promote the preservation of local culture and support sustainable economic development [6].

Rural tourism and rural architecture have a close and interdependent relationship. As important carriers of culture and history in rural areas, rural architecture not only provides unique attractions for rural tourism but also serves as a core resource for its development. Meanwhile, the growth of rural tourism offers new motivation and financial support for the preservation and utilization of rural architecture. Therefore, studying and implementing preservation strategies from the perspectives of architectural conservation [7,8], heritage conservation [9], landscape resources [10], and tourism development is essential. Rural tourism is not only an opportunity to showcase natural landscapes [11], but also a chance to display cultural heritage. In this process, architecture, as a carrier of culture [12], plays a crucial role, and its preservation is vital for cultural representation.

Balancing the demands of modernization and rural tourism presents significant challenges for villages. It is necessary to maintain the traditional appearance of villages while appropriately upgrading tourism facilities and buildings to achieve a balance between heritage conservation and economic development.

Firstly, with the rapid development of rural tourism, rural areas have become an essential part of the tourism industry. This development not only promotes local economic revitalization but also provides visitors with unique natural and cultural experiences. However, the growth of rural tourism also poses threats to local heritage conservation and traditional architecture, including over-commercialization, the destruction of traditional buildings, and the loss of cultural authenticity [13]. Therefore, it is crucial to study how to balance architectural conservation and sustainable utilization within the context of tourism development.

Secondly, current academic research on rural tourism and architectural conservation is largely based on fragmented case studies. Rural tourism and architectural conservation are inherently interdisciplinary topics, encompassing architecture, heritage conservation, and tourism management [14]. Writing a review article can help compile and summarize research findings in these fields, clarify future research directions, and provide theoretical support and practical references for scholars and practitioners.

The practical value of this review lies in providing scientific evidence for rural areas, encouraging local governments and communities to develop tourism while preserving the cultural and historical value of rural architecture.

This study utilizes VOSviewer and CiteSpace software to visually present the knowledge structure, patterns, and distribution within the field. These tools allow for a comprehensive analysis of research status and trends within a specific period, discipline, or field, while also offering predictions for future development [15].

The following section explains the bibliometric methodology and the analytical data used in this study. Subsequently, we present the results of the bibliometric analysis. Finally, we discuss the study’s conclusions, contributions, and limitations.

2. Data Sources and Research Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Retrieval Strategies

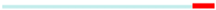

This study utilized the Web of Science (WoS) database to identify academic journals related to rural tourism and architecture. The WoS is the world’s leading citation database, covering over 12,000 high-impact journals. It includes databases such as the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI), and the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), all of which are part of the WoS Core Collection. The WoS comprehensively covers core databases in relevant fields, making it sufficient to showcase patterns and trends in the study of traditional village architecture in the context of rural tourism. To analyze studies on rural tourism and heritage conservation, we collected publication data from the WoS Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and restricted the scope to rural tourism and architecture. Our analysis spans publications from 1996 to 2024, as the first relevant publication with complete information appeared in 1996. Using the search terms “Rural tourism” and “traditional village” or “vernacular architecture” or “traditional architecture” within the title and topic fields, we retrieved 1945 publications. Disciplines unrelated to architecture and tourism, such as telecommunications and mathematics, were excluded from the analysis. Before removing these disciplines, relevant literature within these fields was reviewed to confirm their lack of connection to the study’s topic. Similarly, a manual approach was applied to exclude publications based on thematic relevance. For instance, studies focusing on the application of information service systems in traditional villages were manually identified and excluded as irrelevant to the research theme. The database was refined by including only documents categorized as “articles” or “reviews” and written in English. A unique database containing 1356 publications was created (Figure 1). This database includes textual data such as titles, authors, publication years, languages, abstracts, keywords, and references.

Figure 1.

Literature retrieval flowchart.

2.2. Data Analysis

The filtered literature was exported in RefWorks format and named “download_01.txt”, “download_02.txt”, and “download_03.txt”. Each entry included the author’s name, affiliation, publication date, title, abstract, and keywords. The “download_01.txt” file was imported into VOSviewer 1.6.19 and CiteSpace 6.3.R1 software for analysis. VOSviewer 1.6.19 software was used for the co-occurrence analysis of keywords and superimposed analysis by year. CiteSpace 6.3.R1 was used for keyword clustering, burst detection, timeline analysis, and dual-map overlay analysis.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Characteristics of Literature Publication

3.1.1. Temporal Distribution of Publications

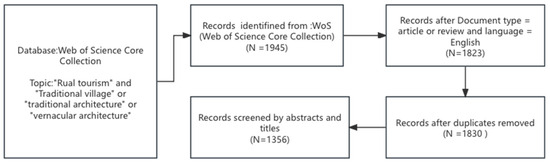

The temporal variation in the number of publications within a specific research field can reflect the development pace of its development. Using the CiteSpace software for screening and verification, 1356 documents related to rural tourism and architecture were identified (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows the annual distribution of publications from 1996 to 2024, illustrating a significant increase in relevant publications after 2009, reflecting the growing importance of research on rural tourism and architectural conservation. The temporal distribution of published papers suggests that the research on rural tourism and architecture can be divided into three phases:

Figure 2.

Time distribution of the number of articles pos.

The Initial Phase (1996–2008)

The period from 1996 to 2008 represents the initial phase, during which research in the field was still in an exploratory stage, characterized by low publication volume and slow growth. Studies during this period primarily focused on the fundamental theories of rural tourism and heritage conservation, lacking systematic approaches and receiving limited attention from the academic community. Additionally, limited technological tools and data acquisition capabilities restricted advancements in the digitization of architectural conservation, while policy and societal support for this topic remained low [13,16]. This phase relied heavily on traditional methods for architectural preservation, with minimal support from modern tools, and societal awareness of architectural conservation was relatively weak [13].

Growth Phase (2009–2018)

The period from 2009 to 2018 marked a developmental phase, characterized by a steady increase in the number of related publications. The notable growth in publication volume during this time reflects the rising academic and societal attention to the field. This accelerated development was closely linked to societal demands and technological advancements. For instance, after the 2008 global financial crisis, rural tourism gained broader attention as a means of economic revitalization, while the emergence of the concept of sustainable development further promoted research on heritage conservation [14,17]. Additionally, the application of remote sensing, digital conservation technologies, and GISs (Geographic Information Systems) introduced new tools and methods for research [17]. Moreover, international emphasis on cultural heritage conservation, driven by organizations such as UNESCO, ushered the field into a period of expansion. The preservation of cultural heritage benefited from multilateral international cooperation, particularly in rural communities, where policy support and the formation of social capital became key drivers of conservation efforts [18].

Peak Phase (2019–2024)

The period from 2019 to 2024 represents a phase of rapid growth, with 1118 papers published during these six years. Publication volume reached an all-time high, with research activity peaking particularly between 2021 and 2023. This phase focused on the integration of interdisciplinary fields, the combination of rural revitalization strategies with heritage conservation, and the impact of global climate change on rural architecture [14,19]. Additionally, strong international policy support, such as the European Union’s cultural heritage conservation programs and China’s rural revitalization strategy, significantly accelerated research progress [20,21]. At the same time, research emphasized the critical role of community participation in architectural conservation. Studies on historic rural villages in Italy revealed that collaboration among multiple stakeholders not only improved the efficiency of architectural conservation but also enhanced the sustainability of rural tourism [22,23]. Although there was a slight decline in publication volume in 2024, the overall research activity remained at a high level.

In summary, these three phases reflect the development trajectory of research in rural tourism and architectural conservation, highlighting the significant influence of technological advancements, policy support, and societal demands on the growth of this field.

3.1.2. Country Distribution

In terms of publication volume (Table 1), China had the highest number of published papers (234), followed by the United States (227). Table 1 illustrates the distribution of publications, the starting years of research, and the academic centrality of tourism architecture studies across different countries. The data indicates that research in this field began in Western nations, such as the UK and the US, and later extended to emerging economies like China. While China leads in publication volume, its academic influence remains relatively modest compared to the UK and the US, which hold top positions in centrality. This pattern highlights the field’s evolution from regional origins to a more global focus. The UK was the first country to research tourism architecture beginning in 1996, the US started in 1998, and China began its research in 2004 (Table 1). Centrality is a measure of a node’s importance within a network and indicates its influence. A higher centrality score suggests greater influence, as indicated by a higher citation rate of published papers, which could signify foundational knowledge literature. The UK (0.31) far exceeds other countries in terms of centrality, followed by the US (0.26). Despite China’s higher volume of publications, its centrality was lower (0.16), indicating that its papers generally have a lower citation rate and lack high-impact articles.

Table 1.

The distribution of publication output by country.

3.1.3. Author Affiliation Analysis

From the perspective of disciplinary distribution, (Table 2) demonstrates that research initially originated in traditional disciplines such as environmental science and geography. In recent years, it has gradually expanded to interdisciplinary fields like materials science, engineering, and computer science, reflecting the transition of this field from environmental and humanities studies to a multidisciplinary integration. Research on rural tourism and architecture is primarily concentrated on Environmental Studies, which pioneered the field with the earliest publications in 1996 and has the highest centrality and largest volume of publications. Materials Science, Multidisciplinary follows, with papers first published in 2009, although it has a smaller volume of publications. Among the top ten disciplines ranked by centrality, it is evident that the study of rural tourism and architecture involves multiple disciplines, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of this field.

Table 2.

Researchers’ disciplinary distribution.

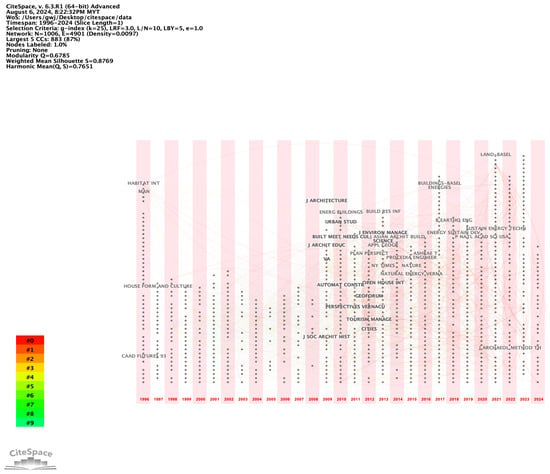

3.2. Research Development Phases

Using CiteSpace to create keyword temporal zone maps and high-citation temporal division maps enables the identification of research frontiers and the prediction of research trends [24]. This study employs CiteSpace to analyze the publication volume of research on rural tourism and architecture (Figure 2), dividing the research into three phases: the initial phase, the growth phase, and the peak phase (as explained in Section 3.1.1). By integrating co-citation analysis maps (Figure 3), Figure 3 illustrates the co-occurrence network and temporal distribution of publications in the field of tourism architecture, highlighting the evolution and research hotspots from 1996 to 2024. Early studies predominantly focused on architecture and culture-related topics, while recent research has increasingly shifted toward interdisciplinary areas such as landscape design and land-use. This reflects the diversification and integration trends in the field. This study identifies highly cited references and provides a phase-based review of major research progress and characteristics.

Figure 3.

Co-citation time zone map of research literature.

3.2.1. Initial Phase (1996–2008)

During the initial phase (prior to 2008), scholars began to focus on the critical issue of how traditional architecture adapts to various climatic conditions. This research particularly emphasized the global environmental impacts on buildings and the adaptive characteristics of architecture in terms of material selection and design methods. As the research progressed, the perspective expanded from single-discipline exploration to multidisciplinary, interactive studies, encompassing fields such as heritage conservation, sustainable development, landscape design, and digital technologies. Table 3 presents the central distribution of high-frequency research keywords in the field of tourism architecture and their evolution across different phases (1996–2024). Early keywords focused on foundational research such as “design”, “architecture”, and “cultural heritage”, which later expanded to performance and environment-related topics such as “thermal comfort”, “climate”, and “strategy.” More recently, the focus has shifted further toward practice and preservation topics like “sustainable development” and “traditional villages,” reflecting the evolution of research from theoretical exploration to applied practice and interdisciplinary integration. Notably, the high-frequency keywords during this phase (Table 3) were “vernacular architecture” and “design”, with centralities of 0.3 and 0.09, respectively. This significance highlights not only the prominent research status of vernacular architecture but also its unique value in addressing climate change and preserving cultural heritage. As a core area of interdisciplinary research, architecture, and tourism increasingly contributed to cultural preservation and economic growth, fostering global cultural exchange and the sustainable development of local economies and societies through multidisciplinary collaboration.

Table 3.

Centrality of high-frequency research keywords.

Architecture and Cultural Heritage Conservation

During the period from 1996 to 2007, the preservation and inheritance of architectural heritage, as a vital carrier of social memory and cultural expression, emerged as a central focus in academic research. Delafons (1997) traced the historical evolution of heritage conservation through policy analysis, highlighting that collaboration between governments and communities is a critical pathway to achieving effective architectural heritage preservation [25]. In addressing the conflicts between urban modernization and heritage conservation, Bizzarro and Nijkamp (1996) proposed a multidimensional policy framework that emphasized the balance between cultural value and economic benefits, which is essential for the long-term sustainability of heritage conservation [26].

Meanwhile, Jokilehto (1999) reviewed the 20th-century practices in heritage conservation, arguing that globalized heritage preservation must account for both local specificity and universal applicability. Jokilehto further underscored the dynamic role of heritage architecture amid sociocultural changes [27]. Additionally, Bizzarro and Nijkamp (1996) reiterated the importance of balancing cultural and economic values as a critical factor for ensuring the sustainable preservation of architectural heritage over time [26].

Integration of Architecture and Tourism

Architecture, as a tangible expression of culture and history, has gradually taken a central role in tourism development. Asquith and Vellinga (2006) highlight that architecture serves not only as a medium for tourists to understand local culture but also as a crucial physical attraction. Through the expression of history and culture, it facilitates connections between local and global contexts [28]. Shepherd (2006) further emphasizes the role of international organizations such as UNESCO in promoting the interaction between architecture and tourism through cultural heritage programs. These efforts have made architecture a bridge between cultural dissemination and economic growth [29].

However, the integration of architecture and tourism also faces numerous challenges. Nasser (2003) points out that in many historic towns, tourism development often leads to the over-commercialization of cultural heritage. To address this issue, he proposes a community-oriented conservation model to balance heritage conservation and tourism demands [30]. Additionally, Hospers (2002) explores how industrial heritage tourism can serve as a strategy for regional restructuring, underscoring the potential of cultural heritage to drive regional economic transformation [31].

Sustainable Development and Architectural Design

With the global promotion of sustainable development, architectural design has increasingly focused on eco-friendliness and cultural preservation as core issues. Studies on traditional Spanish architecture demonstrate the practical value of traditional techniques in optimizing energy use and climate adaptability. For example, material selection and spatial design have been shown to effectively address regional climate challenges [32]. Additionally, bioclimatic architectural design has exhibited significant potential in reducing carbon emissions and achieving harmony between buildings and nature, particularly by extending traditional design principles to enhance adaptability [33]. Historical studies highlight that in high-rainfall and humid regions, traditional buildings improve weather resistance and maintain indoor thermal comfort through roof slopes, wall materials, and spatial configurations [32,34,35].

The application of traditional architecture in specific geographic and cultural contexts also provides valuable insights. For example, on the island of Cyprus, model housing designs that combine vernacular architecture with climate and topographical conditions demonstrate a human-centered approach to traditional settlement patterns. These designs also explore materials and design strategies to offer sustainable housing solutions [36,37]. Similarly, in Iceland, turf farm buildings exemplify the deep connection between traditional craftsmanship and climate adaptability. Research on these structures reveals the wisdom embedded in traditional architecture for maintaining comfortable living environments [38].

Across broader regional contexts, traditional architectural strategies under different climatic conditions offer diverse inspirations for modern architecture. In Egypt, traditional building methods have achieved dual benefits of energy efficiency and occupant comfort through optimized design techniques, providing new insights for contemporary architectural practices [39]. Research on traditional settlements in Greece shows that optimizing passive design principles—such as adjusting building layouts and material selection—can significantly improve the harmony between architecture and natural environments while enhancing energy efficiency and ecological adaptability [40].

Overall, the integration of traditional architectural techniques with modern design methods plays a vital role in climate adaptability and cultural preservation. These studies collectively reveal that by drawing inspiration from tradition and incorporating modern technological approaches, architectural design can achieve energy efficiency while fostering harmony between humans and nature.

Tourism Landscapes and Architectural Forms

With the acceleration of modernization, the gradual disappearance of traditional architectural features has raised concerns about heritage conservation and architectural sustainability. Studies on the application of modular design in the eastern Black Sea region emphasize the balance between preserving local characteristics and meeting modern living needs. Similarly, research in Cyprus criticizes modern urban design for neglecting the sustainability of traditional settlement patterns and advocates integrating traditional ecological wisdom and local values into new architectural designs [36]. Such studies suggest that traditional architecture is actively seeking modernization in its design approaches.

Architectural landscapes, as a unique form of cultural expression, embody local history and social memory while serving as vital components in enhancing tourism appeal. During the development of tourism, mid-century modern architecture has been imbued with new meanings. These architectural forms showcase the uniqueness of local culture, capturing visitors’ attention and deepening their understanding of the history and culture of destinations [41]. The conservation of traditional architecture not only respects history but also supports sustainable development. For instance, research on underground wine cellars in Spain highlights the importance of repurposing these structures while maintaining their roles in socio-cultural activities [42]. Similarly, studies on turf farms in Iceland demonstrate how these structures adapt to harsh climates while providing insights into their conservation and sustainable utilization [43].

The conservation and utilization of architectural landscapes often require interdisciplinary collaboration. The integration of landscape design and cultural heritage transmission provides a significant pathway for the coordinated development of heritage conservation and modern tourism. This approach not only promotes the integrity of heritage conservation but also enriches tourism with deeper cultural dimensions and enhances its sustainable potential [44]. In the context of globalization, the summarized experiences of architectural conservation offer valuable insights for the protection of cultural landscapes in developing countries. These experiences highlight the importance of balancing local characteristics and universal values when formulating policy frameworks to achieve the dual objectives of cultural preservation and economic development [27].

Overall, architectural landscapes not only enhance the appeal of cultural heritage but also enrich the cultural dimensions of modern tourism, fostering the multidimensional synergy of local economic growth and cultural dissemination.

Traditional Architecture’s Adaptation to Climate Change

After 2000, with the establishment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the emergence of the Smart Growth Theory. Studies began to integrate rural tourism and architectural topics into climate adaptability and energy efficiency, with high-frequency keywords such as “Thermal Comfort”, “Performance”, and “Strategy” emerging during this period (Table 2). Among these, “Thermal Comfort”, and “Performance” demonstrated significant prominence (0.06 and 0.05, respectively), highlighting these as key research focuses.

Traditional architecture often reflects a deep understanding of and adaptation to local climate conditions. Studies on traditional architecture in northeastern India revealed that natural ventilation and specific design elements, such as building forms, orientation, and envelope structures, effectively enhanced energy efficiency [45]. Similarly, an analysis of the thermal performance of vaulted traditional houses in Harran, Turkey, showed that these buildings maintained indoor thermal comfort even during extreme summer conditions [46]. In Nepal, traditional architectural designs were found to optimize the use of natural resources under varying climatic conditions [47].

Traditional buildings also exhibit significant advantages in energy efficiency. Research indicates that modern architectural designs often neglect passive environmental control methods, resulting in high energy consumption and environmental issues [48].

By contrast, traditional buildings use natural ventilation, shading, and the thermal mass of materials to maintain indoor comfort while significantly reducing energy demand. Case studies have explored traditional architectural lighting and continuity, proposing solutions to optimize energy usage [49].

Socioeconomic changes have led to the transformation of traditional building forms. For example, traditional architecture in Telangana, India, has been increasingly replaced by modern structures that disregard climatic and cultural considerations [50]. In Europe, preserving traditional farm buildings and converting them for new economic or social uses has been identified as a beneficial practice for enhancing agricultural productivity [51].

Understanding the sustainability of traditional architecture requires the integration of social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Studies on passive cooling systems in central Iran revealed that residents’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors, along with sociocultural and economic factors, significantly influence the systems’ usage and sustainability [52].

Modern architectural practices often fail to fully utilize traditional design strategies, resulting in reduced thermal comfort and energy efficiency. Research in Spain highlighted bioclimatic strategies for traditional cave dwellings, such as site orientation and ventilation design [53]. A study on climate-responsive design strategies in vernacular housing in Vietnam proposed a novel approach to evaluating the climatic adaptability of traditional dwellings [54].

The design and construction techniques of traditional architecture represent long-term optimization for local climatic conditions. To achieve sustainable building design, modern practices should re-evaluate and integrate climate-responsive strategies from traditional architecture. Future research should further explore the application of these strategies in modern contexts to enhance energy efficiency and reduce environmental impacts.

Preliminary Applications of Digital Technology

The advancement of digital technologies has provided new tools for heritage conservation and tourism planning. GISs and remote sensing have enhanced the efficiency and precision of conservation efforts, aiding in data collection, land-use monitoring, and site management [55]. These technologies have proven valuable in data collection, land-use monitoring, and the long-term management of heritage conservation. By integrating multi-source data, researchers can gain deeper insights into the dynamic changes in protected areas, providing a solid basis for policy-making and management decisions [56]. The support of laws and policies is regarded as an essential prerequisite for advancing digital tools in heritage conservation [57]. The establishment of this framework enables digital preservation tools to play a critical role in heritage conservation management, providing a solid foundation for future preservation and development efforts.

3.2.2. Development Phase (2009–2017)

In the context of globalization and rapid urbanization, research on rural tourism and architecture has expanded from previous phases to include various directions. These include the cultural and social significance of rural architecture, environmental adaptability and sustainability, technological innovation and heritage conservation, interactions between rural tourism and traditional architecture, and protection strategies in the face of modernization challenges. Based on co-citation analysis, key research areas during this phase focus on topics such as “Rammed Earth” (0.03), “Indoor Thermal Comfort” (0.02), “Construction” (0.02), and “Heritage” (0.02), which are identified as central themes with high centrality scores.

The main research content emphasizes community participation and sustainable development, the protection and adaptive reuse of rural architectural heritage, and innovation in architectural and landscape design.

Sustainable development in rural tourism is a significant challenge, balancing economic growth with cultural preservation, and community participation plays a central role in this process. Through active involvement in planning and implementation, communities can not only promote economic benefits but also strengthen social cohesion and self-identity [58]. Studies in the Mutianyu Great Wall scenic area in Beijing, China, indicate that while community members have limited involvement in decision-making, their overall attitude toward tourism development is positive. With appropriate community participation mechanisms, a balance between heritage conservation and economic benefits can be achieved [59]. Similarly, in Africa, communities successfully coordinated economic and ecological goals, providing a model for sustainable rural tourism and highlighting the critical role of local stakeholders in planning and implementation [60]. These studies show that community participation is essential for achieving multiple goals in rural tourism, laying a theoretical foundation for future research.

Within the framework of sustainable rural tourism, the protection and adaptive reuse of architectural heritage are increasingly regarded as dual drivers for cultural preservation and economic growth. Case studies reveal that architectural heritage not only enhances the attractiveness of local tourism but also improves regional competitiveness through the interaction of culture and economy. Japanese architectural heritage demonstrates the deeper cultural [60] and social transmission that rural architecture represents. However, modernization presents challenges for preserving traditional charm while integrating modern building technologies [61] and addressing the coexistence of traditional earthen architectural heritage with modern structures [62]. These challenges go beyond technical and design issues to include shaping and maintaining the architectural identity of regions or ethnic groups [63,64]. Additionally, studies have assessed rural landscape resources [65], developed evaluation systems for various landscape resources [66], and analyzed tourism resources across different provinces [67], in the context of digitalization, researchers have begun exploring “Internet+ rural smart tourism systems” [68]. Overall, the focus has been more on analyzing comprehensive tourism resources rather than specific aspects.

Architecture and landscape design, as integral components of rural tourism, not only enhance local attractiveness but also promote cultural heritage transmission and harmony with the natural environment. In the Hani Terraces of Yunnan, China, community recognition of the value of architectural heritage and active participation have achieved a dynamic balance between cultural heritage conservation and tourism development, providing a model for other developing countries [69]. In Greece, a community-led approach has yielded significant results in the conservation and adaptive reuse of rural architectural landscapes, preserving cultural values while revitalizing community life through local economic activities [70]. In Shaanxi’s Yuanjia Village, rural tourism has driven the revival of traditional villages, with the community playing a vital role in resource integration and tourism product development. This model has significantly boosted local economic benefits while preserving unique cultural heritage [71]. This section underscores how the dynamic protection and adaptive reuse of architectural heritage are achieved through community collaboration, closely aligning with the role of community participation in tourism development. This phase focused more on evaluating landscape and architectural resources and developing multidimensional assessment models. Quantitative methods became more prevalent, with a rapid increase in publications and co-cited references (Table 3). This reflects the expansion of research topics alongside advancements in theories and methodologies, leading to greater diversity in the field.

3.2.3. Rapid Growth Phase (2018–2024)

Recent studies on rural tourism and architecture have increasingly focused on eco-friendly building materials, traditional construction techniques, and the integration of architecture with environmental adaptability. Earthen buildings, as a low-carbon and sustainable material, demonstrate cost efficiency and environmental benefits, offering innovative ideas for blending rural architecture with tourism [72,73]. Moreover, modern technologies can enhance traditional construction methods, improving functionality while preserving cultural characteristics, thereby promoting the sustainable development of rural tourism architecture [74].

Indoor thermal comfort has become a key focus in rural architecture research, with studies exploring design optimization, ventilation, and insulation measures. By integrating bioclimatic principles [75], these designs have not only improved thermal comfort in living environments [76] and developed multidimensional models to assess the sustainability of traditional buildings [77], but also reduced energy consumption in rural housing [78]. Traditional buildings demonstrate stronger ecological sustainability [79]. Promoting these design concepts aligns buildings with rural ecological needs, while enhancing their cultural appeal and functionality, laying a foundation for rural tourism development [80].

Traditional building techniques are widely regarded as core resources for rural tourism development. Reusing traditional craftsmanship preserves local architectural features while enhancing their functionality and sustainability through modernization [81]. The use of rammed earth construction in rural tourism demonstrates strong adaptability and cultural value. By integrating resources and improving techniques, these architectural forms have been successfully incorporated into tourism projects and have become representatives of local identity [82].

Research on the conservation and reuse of cultural heritage focuses on enhancing the tourism appeal of architectural heritage and boosting community economic benefits. Studies indicate that functional adaptations of architectural heritage not only preserve cultural value but also invigorate community economic activities [83]. Traditional village buildings excel in this regard, with effective conservation and reuse strategies enabling their integration into modern rural tourism while playing a key role in cultural transmission and ecological protection [71].

Research on the environmental impact of architecture has expanded from technical adaptability to comprehensive environmental assessments. Scholars emphasize that combining traditional techniques with modern ecological concepts can effectively reduce the carbon footprint of buildings while enhancing their environmental adaptability [84]. Life cycle analysis of buildings indicates that this integration reduces energy consumption and encourages community participation in planning and implementation. This approach allows rural tourism buildings to better meet sustainable development goals [81].

Overall, this phase of research has achieved significant progress in exploring the integration of traditional building forms with modern technologies. It highlights the multidimensional value of interdisciplinary collaboration between rural architecture and tourism. These studies deepen the synergy of culture, ecology, and economy in rural architecture and provide theoretical foundations and practical insights for the sustainable development of rural tourism, supporting rural revitalization efforts.

4. Research Hotspots and Trends Analysis

The field of rural tourism and architecture has developed rapidly in recent years, focusing on sustainability, heritage conservation, and the reuse of vernacular architecture. This chapter employs bibliometric tools to systematically analyze studies from 1996 to 2024, identifying research hotspots and trends such as “vernacular architecture”, “thermal comfort”, and “sustainability.” The section includes (1) identifying and classifying research hotspots in rural tourism and architecture through keyword clustering; (2) revealing temporal evolution characteristics of research hotspots using keyword burst and timeline analysis; and (3) forecasting future research directions. By examining the distribution and evolution of these hotspots, this chapter provides theoretical support and practical insights for rural development and architectural practices.

4.1. Analysis of Research Hotspots

4.1.1. Distribution of Research Hotspots Based on Keyword Clustering

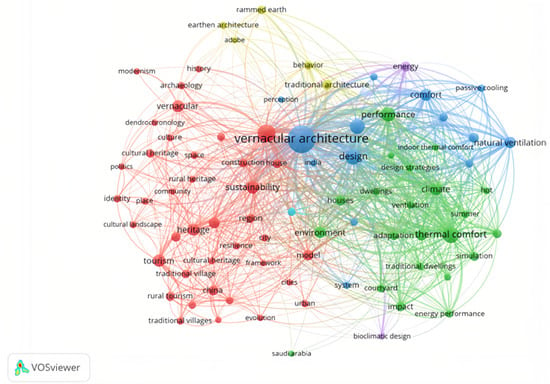

Keywords in the literature are a concise summary of the main content of the articles. Keyword frequency analysis is often used in bibliometrics to reveal the distribution of research hotspots. VOSviewer uses node size, color, line thickness, distance, and density to represent connections between key nodes and research topics, providing a clearer visual representation of relationships between important nodes, themes, and keywords [48]. With a minimum threshold of eight occurrences, 48 high-frequency keywords were selected to create the keyword co-occurrence network map (Figure 4) and the annual overlay map (Figure 5) for rural tourism and architecture studies. High-frequency keywords such as “vernacular architecture”, “architecture”, “thermal comfort”, “sustainability”, “design”, “heritage”, and “rural tourism” represent major research hotspots in this field.

Figure 4.

Research keyword co-occurrence network map.

Figure 5.

Research annual overlap map.

Figure 4 illustrates the co-occurrence network based on high-frequency research keywords, with “vernacular architecture” as the core keyword. The research themes have evolved from “design” and “sustainability” to interdisciplinary directions such as “thermal comfort” and “climate adaptation”, reflecting the gradual transition of the tourism architecture field from theoretical studies to practical applications and environmental optimization. In the keyword co-occurrence network map (Figure 4), “vernacular architecture”, “thermal comfort”, and “design” are the most frequent keywords, appearing 334, 89, and 78 times, respectively, with the highest relevance (0.3, 0.06, and 0.09, respectively). These terms form the core concepts of rural tourism and architecture research. Surrounding these core concepts, other high-frequency keywords, based on their co-occurrence relationships, form three major research clusters represented in red, green, and blue.

The Red Cluster

The red cluster includes high-frequency terms such as “vernacular architecture [60]” “heritage”, and “tourism”, focusing on the relationship between vernacular architecture, cultural heritage, cultural landscapes, and tourism. The research primarily targets the cultural and spatial characteristics of rural architecture, aiming to promote sustainability [85], and develop indicators for cultural heritage evaluation. Case studies and quantitative evaluation tools are commonly used methods. This cluster also highlights diverse research regions, covering case studies from Europe, Asia, and Africa, offering valuable insights for heritage conservation on a global scale.

The Green Cluster

The green cluster, with keywords such as “thermal comfort”, “climate”, and “houses”, highlights research on architecture and thermal comfort in the context of climate change. The studies mainly focus on “traditional dwellings” and “courtyard houses” [7,86], exploring how these traditional structures adapt to climate changes through design adjustments. Research on tropical climates emphasizes natural ventilation, shading, and material selection to optimize indoor comfort. Additionally, studies reveal the adaptive characteristics of architecture in various global regions, highlighting the unique advantages of traditional designs in thermal comfort. The effectiveness of these design strategies is validated through simulations and field studies.

The Blue Cluster

The blue cluster, represented by keywords such as “vernacular architecture”, “design”, and “natural ventilation”, highlights the relationship between vernacular architecture, design strategies, and energy efficiency. The research focuses on passive cooling technologies, optimization of natural ventilation, and material selection. This cluster emphasizes the modernization of traditional architectural forms to achieve energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Studies in tropical and arid regions analyze ventilation performance in vernacular buildings, proposing climate-based design solutions for natural ventilation. Additionally, the blue cluster explores energy efficiency through the building lifecycle, from initial material selection to maintenance optimization during use, offering a holistic lifecycle design perspective.

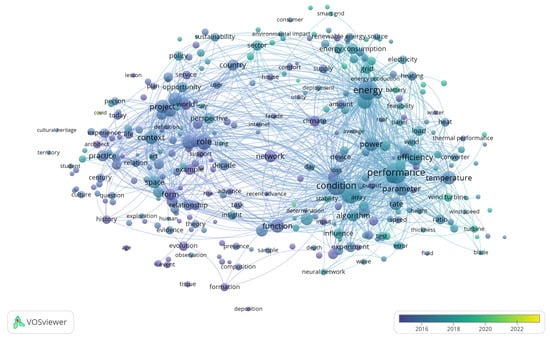

4.1.2. Based on the Annual Keyword Overlay Network Co-Occurrence

Figure 5 illustrates the high-frequency keyword co-occurrence network based on VOSviewer, with “vernacular architecture” as the core keyword. The research themes have gradually shifted from classic topics like “design” and “sustainability” to directions focusing more on environmental and technological applications, such as “thermal comfort”, “climate adaptation”, and “energy performance”. The color gradient indicates that research hotspots have progressively transitioned towards practical applications and interdisciplinary integration between 2017 and 2022, reflecting the dynamic evolution of research themes. The keyword co-occurrence network diagram (Figure 5) uses colors, node sizes, and connections to illustrate the dynamic evolution of research hotspots in the field of rural tourism and architecture.

Each node in the diagram represents a high-frequency keyword. The size of the node indicates the frequency of the keyword, with larger nodes signifying greater importance in the research [87]. The lines between nodes represent co-occurrence relationships; the thicker the lines, the stronger the association between the two keywords in the same study [87]. The color of the nodes transitions from blue (2017) to yellow (2022), reflecting the evolution of keyword popularity over time. This diagram clearly reveals the dynamic evolution of research hotspots in rural tourism and architecture over time. It highlights the shift in research themes from traditional building preservation to sustainable design and underscores the growing importance of digital technologies and traditional village conservation in recent years.

Each node in the diagram represents a high-frequency keyword. The size of the node reflects the frequency of the keyword, with larger nodes indicating greater importance in the research. The lines between nodes represent co-occurrence relationships, with thicker and more numerous lines signifying stronger associations between keywords in the same study. The node colors transition from blue (2017) to yellow (2022), showing the evolution of keyword popularity over time. This diagram clearly illustrates the dynamic evolution of research hotspots in rural tourism and architecture over time. It highlights the thematic shift from traditional building preservation to sustainable design and emphasizes the growing importance of digital technologies and traditional village conservation in recent years. The diagram vividly presents the dynamic evolution of research hotspots in the field from 2017 to 2022, with several notable features.

The core keywords and network structure highlight the concentration and interconnection of research themes. In Figure 5, “vernacular architecture” holds a central position, demonstrating its leading role in the research. Closely related keywords such as “sustainability”, “thermal comfort”, and “design” collectively form the primary framework of rural architecture research. The tight connections and high-density network among these keywords indicate their strong associations, reflecting the systematic nature and interdisciplinary characteristics of the research content.

The distribution of colors and time dimensions reveals the dynamic evolution of research hotspots. Node colors transition from blue (2017) to yellow (2022), indicating changes in research focus over time. Blue-green nodes such as “climate” and “performance” were active around 2018, while yellow nodes like “traditional villages” and “impact” gained prominence between 2021 and 2022. This trend reflects the growing academic interest in heritage conservation of traditional villages and sustainable development topics in recent years.

The temporal evolution trend highlights both long-term and emerging hotspots in the field. “Vernacular architecture” and “sustainability” have remained consistent long-term research themes. However, between 2021 and 2022, emerging keywords like “traditional villages” and “digital technologies” indicate a shift from traditional building conservation to the application of digital technologies and management optimization.

The research themes are represented by different color areas, each highlighting a distinct focus. The green area emphasizes climate adaptability and thermal comfort, exploring how traditional dwellings use passive strategies like natural ventilation and shading to address climate challenges. The blue area centers on design strategies, optimizing natural ventilation, and enhancing energy efficiency, underscoring the importance of integrating sustainability into the building lifecycle. Recently, the yellow nodes indicated a shift from static conservation to dynamic models that integrate economic development and cultural heritage. Keywords like “traditional villages” and “heritage” have become prominent focal points.

The Annual Keyword Overlay Network Co-occurrence illustrates the spatiotemporal evolution of research hotspots in the rural architecture field, highlighting the shift from traditional themes to interdisciplinary integration. This trend provides critical guidance for future studies, particularly in the application of digital technologies and climate-adaptive design.

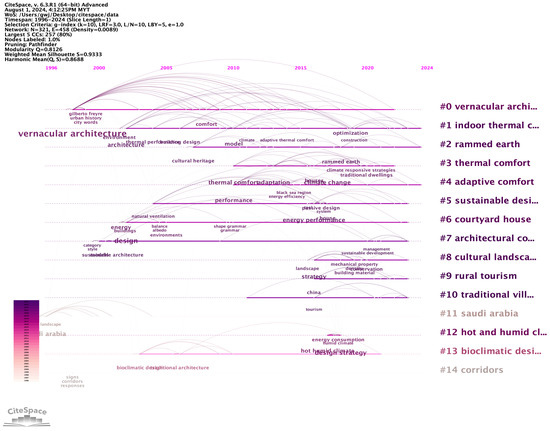

4.2. The Evolutionary Characteristics of Research Hotspots Based on Keyword Bursts

CiteSpace enables the visualization of keyword co-occurrence and literature co-citation through timeline mapping, facilitating the analysis of research hotspot evolution.

This parameter highlights the structural features of the field, suggesting core themes within different clusters. Figure 6 presents the temporal distribution of high-frequency research themes generated through CiteSpace analysis. Core themes such as “vernacular architecture” remain consistently active, while topics like “indoor thermal comfort” and “rammed earth” have gradually emerged as research hotspots in recent years. This reflects a dynamic evolution of research from traditional architectural theories to directions emphasizing environmental adaptability and sustainable design. Timeline Analysis (Figure 6) reveals the dynamic evolution of research hotspots from 1996 to 2024. “Vernacular architecture” remains the central theme throughout, underscoring its dominant role in rural architecture and tourism studies. Additionally, topics like “thermal comfort” and “sustainable design” emerged as new research focuses after 2010, reflecting increasing attention to climate change, energy-efficient design, and sustainable development.

Figure 6.

Timeline axis diagram of research across different periods.

4.2.1. Research Hotspots Based on Keyword Bursts from 1994 to 2024

The research hotspots based on keyword bursts from 1994 to 2024 reveal frequency changes in keywords over time, highlighting potential developments and research value during specific periods [87]. In Figure 5, Modularity Q measures the clarity and independence of keyword clusters, with a current value of 0.5358, indicating relatively clear clustering and independent research themes [87]. Mean Silhouette reflects cluster cohesion and differentiation, and the current value of 0.1684 suggests some overlap between themes, indicating that the boundaries between research fields are not entirely distinct [87]. Additionally, Largest Cluster Size represents the number of documents related to dominant themes, currently at 536, showing a concentration in specific areas of research with significant representation in the literature [88]. Links, representing citation density between documents, is currently at 203,417, reflecting active interaction and strong collaboration within the academic domain [87]. The top 15 research hotspots identified include #0 vernacular architecture, #1 indoor thermal comfort, #2 rammed earth, #3 thermal comfort, #4 adaptive comfort, #5 sustainable design, #6 courtyard house, #7 architecture, #8 cultural landscape, #9 rural tourism, #10 traditional village, #11 Saudi Arabia, #12 hot and humid climate, #13 bioclimatic design, and #14 corridors. These topics encompass a wide range of areas, reaffirming the multidisciplinary nature of rural tourism and architectural research. Furthermore, the focus and key issues of research vary significantly across different periods.

The analysis of keyword bursts in rural tourism and architecture research from 1996 to 2024 identified 87 burst terms, with the top 25 high-frequency keywords selected for further study (Table 4). Table 4 presents the 25 most-cited research keywords in the field of tourism architecture from 1996 to 2024 and their active time periods. Keywords such as “vernacular house”, “natural ventilation”, and “heritage” highlight the research focus at different time points. In recent years, keywords like “traditional villages”, “tourism”, and “impact” have gradually become hotspots, reflecting a shift in research from environmental performance and building materials to an integrated focus on rural culture and heritage conservation.

Table 4.

Top 25 most cited research keywords from 1996 to 2024.

The research highlights significant differences in hotspots across periods: Before 2004, studies primarily focused on specific countries, such as China and India, emphasizing strategies for protecting rural architecture and cultural heritage. Between 2017 and 2023, research expanded to include topics such as water quality management, landscape diversity, and groundwater conservation, while introducing emerging themes directly related to rural tourism architecture, such as vernacular house, passive cooling, and building materials. Since 2018, research hotspots have become more diversified, with keywords like heritage, rural heritage, and traditional villages gaining prominence, reflecting a shift in focus from urban to rural areas, particularly on the protection and development of rural heritage and traditional villages.

4.2.2. Research Clusters from 2018 to 2024

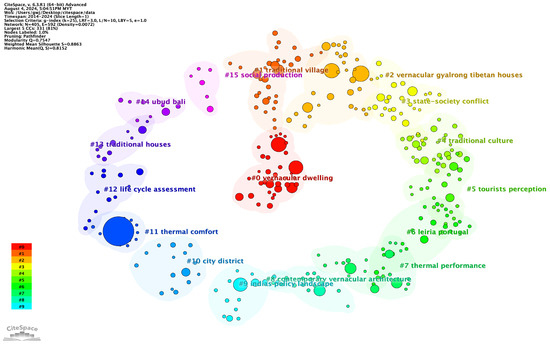

Since bibliometric analysis primarily relies on citation relationships in historical literature, recent research hotspots are not fully reflected. As shown in Table 1, the centrality of keywords from 2018 onward is close to 0, indicating a limitation in bibliometric analysis for capturing recent research dynamics. Therefore, by focusing on keywords from the past six years (2018–2024) and their cluster analysis (Figure 7), recent research trends can be identified more precisely.

Figure 7.

Keyword Clustering of 2018 to 2024.

Based on the keyword clustering map, the log-likelihood ratio algorithm was used to analyze the top seven clusters from 2018 to 2024 (Figure 7). Figure 7 illustrates a clustering map of research keywords generated through CiteSpace analysis. Keywords such as “vernacular dwelling”, “thermal comfort”, and “traditional village” highlight the primary research themes in the field of tourism architecture. Early research focused on environmental performance and building functionality (e.g., thermal comfort and life cycle assessment), while recent studies have gradually shifted toward cultural and social production topics (e.g., traditional villages and social conflict), reflecting a transition from technical investigations to comprehensive socio-cultural exploration. The results show a Modularity Q value of 0.5483, indicating high clarity in keyword clustering and significant differentiation among topics, highlighting the strong independence of research themes [87]. The Mean Silhouette value of 0.8112 further suggests good compactness and clear boundaries within clusters, ensuring a reasonable structure [87]. The Largest Cluster Size, at 536, reflects a dominant theme that occupies a significant proportion of the literature and represents the core focus of this field [87]. Additionally, the high number of Links (203,417) demonstrates frequent interactions among publications, active academic exchange, and robust knowledge sharing [87]. The clusters include keywords such as Vernacular Dwelling, Traditional Village, Indoor Thermal Comfort, Stat-Society Conflict, and Tourists Perception. These clusters reveal an expansion of research subjects and a growing richness of influencing factors. Traditional Village, as an emerging theme, reflects the academic focus on heritage conservation and rural development, while Indoor Thermal Comfort highlights progress in research on environmental adaptability and ecological design in rural architecture. These keywords indicate that rural tourism and architectural studies have shifted from traditional conservation to multidisciplinary integration and ecological technology.

4.3. Prediction of Research Trend Hotspots

Based on the results of bibliometric analysis in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, future research in rural tourism and architecture is likely to follow several major trends. These trends not only reflect the continuation of current research hotspots but also highlight potential directions for innovation.

4.3.1. Architectural Adaptation and Energy-Saving Strategies in the Context of Climate Change

As climate change increasingly affects rural environments and architectural needs, research will focus more on adaptive building design and energy-saving strategies [88]. Traditional architecture effectively addresses various climatic conditions through passive designs such as natural ventilation, shading, and thermal mass optimization [54]. However, the rapid development of modern vernacular architecture has not sufficiently addressed the need for climate adaptability [47]. Future studies will explore low-energy [89], high-adaptability practices [90,91] by integrating advanced materials, design optimization, and smart technologies. Comparative research across regions and climatic zones will also aid in developing universal design and evaluation systems, providing scientific guidance for buildings under diverse geographic conditions [92]. This research is significant not only for addressing climate change but also for informing global sustainable building design practices.

4.3.2. The Integration of Digital Technology and Rural Architecture

The rapid development of digital technology offers new opportunities for rural architecture preservation and management. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies enable researchers to digitally record cultural heritage while providing immersive visitor experiences, enhancing cultural awareness and minimizing direct interference with buildings [93]. Data and artificial intelligence applications will further promote smart rural resource management, such as optimizing building environments and visitor flow through data mining and predictive models. Additionally, the Internet of Things (IoT) can support real-time monitoring systems to assess the physical condition and environmental adaptability of rural structures [93,94]. In the future, blockchain-based heritage certification, intelligent monitoring systems, and digital rural resource archives will become key directions. These technologies can improve rural architecture management, advance tourism development, and enhance the efficiency of heritage conservation.

4.3.3. Differentiated Development of Rural Tourism and Community Collaboration

With the maturation of the rural tourism market and the diversification of visitor demands, differentiated development and community collaboration have become key research directions. Rural tourism requires deeper exploration of local characteristics, integrating traditional architecture and cultural resources to create unique tourism experiences [2]. Meanwhile, community participation and benefit-sharing mechanisms will be critical to achieving sustainable rural tourism development [95]. Research will further investigate the role of communities in tourism policy-making and cultural landscape development, ensuring a balance between local interests and cultural preservation. Additionally, the application of smart tourism technologies, such as personalized recommendation systems and visitor behavior analysis, will enable rural tourism to better meet visitor needs while injecting new vitality into the community economy [96].

4.3.4. Balancing Traditional Village Preservation and Modernization

Balancing the preservation of traditional villages with modernization needs remains a long-term challenge. Studies indicate that excessive commercialization may cause villages to lose their original characteristics, while modernizing infrastructure is essential for improving residents’ quality of life [97]. Future research will focus on integrating modern infrastructure, such as water supply, electricity, and transportation systems, while maintaining the cultural features of villages [98]. Additionally, policy support and economic compensation mechanisms will be incorporated into research frameworks to ensure the protection of villagers’ interests. By analyzing cases from different regions, researchers aim to develop more adaptive conservation and development strategies, providing comprehensive solutions for traditional villages.

4.3.5. Ecological and Sustainable Practices in Rural Architecture

The concept of ecology and sustainability will see broader application in future rural architecture research. Key directions include the development and promotion of green materials, the use of renewable energy, and the introduction of water resource management technologies [99]. For instance, the modernization of traditional rammed earth and stone masonry buildings is emerging as a research focus. By integrating advanced construction technologies, these traditional forms aim to achieve low-carbon and high-efficiency outcomes [100]. Additionally, research will emphasize the environmental impact of building lifecycles, conducting comprehensive analyses from material production to operation and demolition stages, thus providing scientific foundations for ecological optimization in rural architecture [79].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Result

The number of publications in the field of rural tourism and architecture has shown a continuous growth trend, with a significant increase after 2009. This field demonstrates the following characteristics: First, the annual increase in publications reflects the growing academic focus on rural tourism and architectural issues. Second, the research spans multiple disciplines, including architecture, heritage conservation, tourism management, and sustainable development, highlighting its interdisciplinary nature [100,101]. Additionally, the research covers a wide range of regions, with significant contributions focusing on China, India, and European countries, demonstrating a strong global perspective.

The research in rural tourism and architecture can be divided into three stages. The first stage (1996–2008) was the initiation phase, primarily focusing on the protection of traditional architecture and cultural heritage, with a narrow disciplinary scope and case study-based methods [102]. The second stage (2009–2016) was the theoretical development phase, where global sustainable development concepts influenced studies on climate adaptability of buildings, ecological building materials, and the economic benefits of rural tourism, broadening research perspectives [103]. The third stage (2017–2024) represents a comprehensive development phase, characterized by multidisciplinary integration and methodological innovation. Recent research extends from traditional building conservation to digitalization, differentiated development, and ecological practices in rural tourism and architecture [93,104].

Based on keyword clustering, burst detection, and timeline analysis, current research hotspots focus on three areas: First, in the context of climate change, studies emphasize the role of traditional and modern rural architecture in climate adaptability and design optimization, stressing energy-efficient and sustainable practices [101]. Second, research on rural tourism highlights community collaboration, aiming to balance resource development and conservation through community participation, providing new directions for rural economic development [59]. Finally, the application of digital technologies in rural architecture and heritage conservation has deepened, including virtual reality (VR), big data, and artificial intelligence, facilitating digital preservation and intelligent management of rural architecture [93,105].

5.2. Research Prospects

5.2.1. Building an Interdisciplinary Research Framework

Research in rural tourism and architecture spans architecture, environmental science, sociology, and economics. Future studies should emphasize interdisciplinary collaboration by integrating theories and methods from various fields to address the complex challenges of rural development. For instance, combining environmental science and architectural design could help develop adaptive building theories suited to climate change. Similarly, merging sociology with digital technology in heritage conservation could enhance public participation and cultural identity.

5.2.2. Strengthening Research on Rural–Urban Interaction

Current studies mainly focus on rural architecture and tourism, often neglecting the rural–urban interplay. Future research could explore how rural development supports urban areas culturally, ecologically, and economically, and how urban resources contribute to rural modernization. Strengthening rural–urban collaboration could enhance rural resilience and sustainability.

5.2.3. Deepening Long-Term Studies on Technology Applications

While digital technology has seen initial applications in rural architectural preservation and tourism management, its long-term effects remain underexplored. Future studies should comprehensively evaluate dimensions such as implementation efficacy, societal acceptance, and environmental impact. For example, research could assess whether technologies like VR and AR effectively achieve long-term cultural dissemination and resource protection goals and examine the potential effects of smart tourism systems on rural economies and ecosystems.

5.2.4. Addressing the Dynamics of Rural Society and Culture

Rural tourism and architectural research must increasingly consider the dynamic nature of rural society and culture, particularly the impacts of tourism development on community structures, traditions, and social psychology. Future studies could focus on how to preserve local culture during rural development while preventing excessive commercialization, enabling the dynamic inheritance and innovation of cultural traditions.

5.2.5. Promoting Global Cooperation in Rural Research

Currently, rural tourism and architectural research exhibits strong regional characteristics, but challenges such as climate change, population decline, and heritage conservation are global in scope. Future research should encourage international collaboration, facilitating comparative studies and experience-sharing among countries on rural architectural preservation, tourism development, and ecological practices.

5.3. Research Contribution

This study makes two contributions. First, it provides a clearer representation of the status and content of research on rural tourism and architecture, making it easier to trace the origins and foundations of this field. Second, it highlights the developmental trajectory of research in this area, helping scholars better understand its evolution and identify new directions.

5.4. Research Limitations

This study utilizes existing bibliometric analysis tools (CiteSpace and VOSviewer) to explore relevant literature. However, as the data sources are primarily limited to the WoS database, it may have missed relevant studies from other significant databases (e.g., Scopus, CNKI). This limitation could result in insufficient coverage, particularly for regional studies (such as rural architecture research in non-English-speaking countries) and important findings in gray literature.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, W.G.; supervision, M.S.b.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aytuğ, H.K.; Mikaeili, M. Evaluation of Hopa’s Rural Tourism Potential in the Context of European Union Tourism Policy. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Roberts, L. Rural tourism—10 years on. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, D.; Tanic, M.; Kostic, A.; Timotijevic, M.; Jevremovic, L.; Jovanovic, G.; Vasov, M.; Sokolovskii, N. Revitalization of Preschool Buildings: A Methodological Approach. Procedia Eng. 2015, 117, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Lu, S.; Chang, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L. Tourism Environmental Carrying Capacity Review, Hotspot, Issue, and Prospect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Michalko, G.; Ratz, T. Rural milieu in the focus of tourism marketing. J. Tour. Chall. Trends 2008, 1, 83–98. Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=18449743&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA228717074&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Liu, H. Thinking about the connotation of rural tourism. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 2, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcindor, M.; Coq-Huelva, D. Refurbishment, vernacular architecture and invented traditions: The case of the Empordanet (Catalonia). Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D.C.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Gallego-Moreno, F. Architectural and cultural heritage as a driver of social change in rural areas: 10 years (2009–2019) of management and recovery in Huete, a town of Cuenca, Spain. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.T. Tourism, changing architectural styles, and the production of place in Itacaré, Bahia, Brazil. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2014, 12, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, I.; Bojović, M.; Tomanović, D.; Akšamija, L.C. Sustainable Development of Vernacular Residential Architecture: A Case Study of the Karuč Settlement in the Skadar Lake Region of Montenegro. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaeddinoglu, F.; Can, A.S. Identification and classification of nature-based tourism resources: Western Lake Van basin, Turkey. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Gil, J. A theoretical and methodological framework for vernacular architecture. Ciudad.-Rev. Inst. Univ. Urban. Univ. Valladolid 2018, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Garzón, E.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J. Preservation and Conservation of Rural Buildings as a Subject of Cultural Tourism: A Review Concerning the Application of New Technologies and Methodologies. J. Tour. Hosp. 2013, 2, 1000115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: Stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.; Sun, Y.; Min, Q.; Jiao, W. A Community Livelihood Approach to Agricultural Heritage System Conservation and Tourism Development: Xuanhua Grape Garden Urban Agricultural Heritage Site, Hebei Province of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducros, H.B. Confronting sustainable development in two rural heritage valorization models. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, Tourism and Local Development in Peripheral Rural Spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, S. Understanding Perceptions of Tourism Impact on Quality of Life in Traditional Earthen–Wooden Villages: Insights from Residents and Tourists in Meishan. Buildings 2024, 14, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olğun, T.N.; Karatosun, M.B. Rural architectural heritage conservation and sustainability in Turkey: The case of Karaca village of Malatya region. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2019, 14, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, I.; Burgos-Tartera, C.; Aulet, S. Participatory governance of intangible heritage to develop sustainable rural tourism: The timber-raftsmen of La Pobla de Segur, Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 710–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, G.; Arpacıoğlu, Ü.T. Conservation problems of rural architecture: A case study in Gölpazarı, Anatolia. J. Des. Resil. Archit. Plan. 2022, 3, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.; Tumer, E.U. Authenticity- and Sustainability-Based Failure Prevention in the Post-Conservation Life of Reused Historic Houses as Tourist Accommodations: Award-Winning Projects from Isfahan City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafons, J.; Delafons, J. Politics and Preservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarro, F.; Nijkamp, P. Integrated Conservation of Cultural Built Heritage. 1996. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:154406063 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Jokilehto, J. A Century of Heritage Conservation. J. Archit. Conserv. 1999, 5, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, G.M. Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century: Theory, Education and Practice. J. Archit. Educ. 2009, 63, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R. UNESCO and the politics of cultural heritage in Tibet. J. Contemp. Asia 2006, 36, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N. Planning for Urban Heritage Places: Reconciling Conservation, Tourism, and Sustainable Development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Regional Restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, I.; Martín, S. Recovery of Spanish vernacular construction as a model of bioclimatic architecture. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 1477–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L. Architecture and the Environment: Bioclimatic Building Design. 1998. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Architecture-And-The-Environment%3A-Bioclimatic-Jones/309f56cd5e21b521c9c6a359fc34df414288c27b?utm_source=consensus (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- AboulNaga, M.M.; Elsheshtawy, Y.H. Environmental sustainability assessment of buildings in hot climates: The case of the UAE. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C.; Raydan, D.; Steemers, K. Building form and environmental performance: Archetypes, analysis and an arid climate. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, D.; Pontikis, K. In pursuit of humane and sustainable housing patterns on the island of Cyprus. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, N.; Vural, S.; Engin, N.; Reşat Sümerkan, M. Eastern Black Sea Region—A sample of modular design in the vernacular architecture. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2746–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebron Lipovec, N.; Van Balen, K. Preventive Conservation and Maintenance of Architectural Heritage as Means of Preservation of the Spirit of Place. 2008, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/98/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Attia, S.; Herde, A. Bioclimatic Architecture Design Strategies in Egypt | Semantic Scholar. 2009. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Bioclimatic-Architecture-Design-Strategies-in-Egypt-Attia-Herde/0ab8ee98774010b97e6a1132a9fa8b9273b77d3e?utm_source=consensus (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Anna-Maria, V. Evaluation of a sustainable Greek vernacular settlement and its landscape: Architectural typology and building physics. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. A Probe into Tourism Development of Modern Architecture Heritage. J. Qingdao Hotel. Manag. Coll. 2010. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Probe-into-Tourism-Development-of-Modern-Heritage-Jia-jun/270a5de1ab07a7ba0365a2fbe07eb1d8fe952c05?utm_source=consensus (accessed on 18 September 2024).