Abstract

This study proposes an intelligent control algorithm for multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) industrial processes. This algorithm is based on the integration of a digital twin (DT), model predictive control (MPC), a genetic algorithm (GA), and a neural network (NN). The developed architecture employs a hybrid MPC scheme incorporating an additional NN correction branch. The workflow includes input data pre-processing, operating point linearization and NN training, computation of the optimal control sequence over a receding horizon, closed-loop control and adaptation based on prediction error. This innovative hybrid control law uses a linear state-space model as the base predictor and a compact NN superstructure to compensate for unmodeled nonlinearities. The GA searches for the optimal sequence of control actions while respecting process constraints and ensuring stable use of the NN correction. The methodology was tested on a phosphoric acid purification process. Compared to baseline MPC, the proposed algorithm increased purification efficiency to , reduced the integral tracking error by , and decreased the control signal amplitude by 10–15%. Selecting the appropriate reagent supply and vacuum modes ensured stable operation despite fluctuations in the raw material. These results confirm the effectiveness of DT-based hybrid control in applications requiring precision, adaptability, and strict constraint compliance. The approach is scalable and can be applied to other continuous production systems within Industry 4.0 initiatives.

1. Introduction

Modern industrial processes are highly complex, especially in the case of MIMO automation systems. Such systems are characterized by pronounced nonlinearity, delays, and interdependencies of variables, making traditional control methods (such as PID controllers or classic MPC) ineffective. Under conditions of high dynamics and uncertainty, they are unable to ensure the required control quality and energy efficiency [1,2].

In recent years, the concept of digital twins (DTs), which are virtual copies of physical objects, has been rapidly developing. A digital twin allows for the description and prediction of system behavior in real time, creating the basis for optimizing production processes, increasing reliability, and reducing operating costs [3,4]. In the context of Industry 4.0, digital twins are considered a key technology for implementing intelligent control systems [5,6]. Research shows that DT technologies can improve the efficiency of industrial monitoring and diagnostics; however, in practice, problems of data flow synchronization, consistency, and scalability remain unresolved [7,8,9]. Additional aspects of communication infrastructure, IoT sensing, and Smart Manufacturing are discussed in [10,11,12,13].

However, the use of digital twins to control MIMO systems faces a number of challenges [14]:

- (1)

- high computational complexity required for real-time simulation;

- (2)

- difficulties in scaling solutions for industrial objects;

- (3)

- limited capabilities of classical MPC methods to adapt to nonlinearities and disturbances [15,16].

To overcome these limitations, approaches combining digital twins with artificial intelligence and global optimization methods are being actively explored. This approach not only takes into account the physical model of an object but also compensates for its imperfections using neural network corrections and evolutionary search algorithms. Recent works demonstrate the effectiveness of hybrid model-based and machine learning schemes for control problems in chemical engineering processes [5], the use of deep neural networks in MPC to improve adaptivity [15,17,18], and the integration of evolutionary optimization methods and hybrid metaheuristics to find optimal control actions [19,20]. Furthermore, the growing potential of digital twins for energy conservation and sustainable development is noted [7,9].

The aim of this work is to develop and test a predictive control algorithm based on the integration of a digital twin, model predictive control, a genetic algorithm, and a neural network.

The main scientific results and contributions of the article are as follows:

- (1)

- a generalizable digital twin architecture integrated with MPC and AI modules for MIMO system control is proposed;

- (2)

- a two-branch GA + NN hybrid scheme was implemented, where GA performs global search for optimal control moves in the predictive branch, and a compact NN provides bounded nonlinear residual compensation in the corrective branch;

- (3)

- an experimental validation was conducted using the example of the process of phosphoric acid purification, confirming an improvement in the control performance.

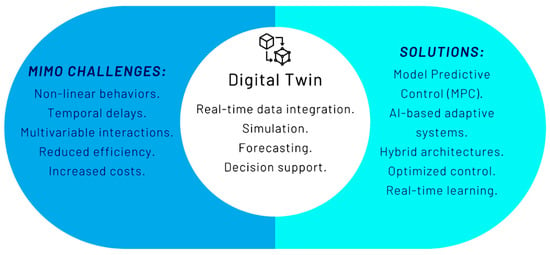

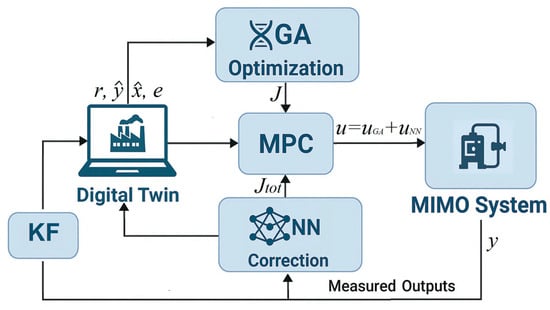

Figure 1 shows the general diagram of the proposed digital twin architecture for solving MIMO system control problems using MPC and intelligent algorithms.

Figure 1.

Digital twin–based MPC framework for MIMO control challenges.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on MIMO control, digital twins, MPC, and AI-based hybrid methods; Section 3 describes the proposed architecture and algorithm for hybrid predictive control; Section 4 contains the results of simulation and experimental verification; and the conclusion (Section 5) discusses prospects for further research.

2. Literature Review

At present, numerous research articles highlight the use of digital twins to improve process observability, implement predictive diagnostics, and enhance control efficiency. For example, Hu et al. [3] demonstrated the use of DT for electrical machine failure diagnostics, highlighting the potential of hybrid physical-virtual modeling in real time. Leng et al. [4] provided a detailed review of digital twin-based smart manufacturing architectures, focusing on their role in improving equipment utilization and implementing predictive maintenance. However, in practical implementation, difficulties remain related to data consistency, integration into real production systems and adaptation to dynamic conditions [7,8].

In parallel, MPC methods are actively developing, which have proven themselves to be an effective tool for multidimensional objects control, taking into account constraints and predicting future behavior [15]. This includes analyzing equipment reliability using time series [21]. However, classical MPC places strict requirements on the accuracy of mathematical models, which limits its application in nonlinear, variable, or disturbed systems. For nonlinear systems with delay, see tube-based MPC [22]. In this regard, approaches integrating elements of machine learning and AI into the MPC framework are becoming increasingly popular [17,18]. For example, Santander et al. [17] and Chen et al. [18] proposed predictive control architectures using deep neural networks, demonstrating improved forecasting accuracy and adaptability in real-world production environments.

Typical applications of MPC include energy management and microclimate in buildings [23,24,25], drives and electromechanical systems [26,27], and energy management of hybrid and electric vehicles [28,29]. Related multi-criteria applications of MPC in related industries are discussed in detail in [30,31].

At the same time, hybrid optimization schemes are being developed that combine a physical model of the plant with data obtained from observations. El Hakim et al. [20] proposed an AI-enhanced MPC for optimizing nonlinear processes in liquefied gas production. Herrera et al. [32] developed a hybrid controller for controlling plants with large delays in chemical engineering systems. Despite the promise of such solutions, they still face problems of adaptation, tuning, and computational complexity when operating in real time.

Research efforts to use digital twins for energy conservation and sustainable development are also noteworthy. Teng et al. [7] demonstrated that digital twin infrastructures can be effectively used to optimize industrial energy consumption through deep integration of data streams. However, in practice, the implementation of such solutions is complicated by the need for precise sensor calibration, high computing load and limitations in data processing speed.

Recent studies explicitly combine DT, MPC, and AI-based models in unified control frameworks. For example, Chen et al. [18] used a time-series deep neural network within a DT-enabled MPC scheme for real-time control in additive manufacturing. Similarly, Ates et al. [33] used a neural network-based digital twin and evolutionary optimization for model-predictive temperature control. In another domain, Qiu et al. [34] combined DT with neural networks to create adaptive suspension control systems in automotive applications. Likewise, Khan et al. [35] applied deep-learning-based digital twins with MPC to optimize battery and storage systems for renewable energy prosumer districts. Finally, Xue et al. [36] introduced a preliminary digital twin framework for nuclear reactor dynamics that tightly couples machine learning models with model predictive control. Collectively, these studies confirm the importance of DT-driven MPC with AI components for MIMO systems.

Table 1 provides a brief comparison of key studies, highlighting their main achievements and limitations.

Table 1.

A review of work on DT, MPC and AI for MIMO Systems.

Table 1.

A review of work on DT, MPC and AI for MIMO Systems.

| Study | Research Focus and Objectives | Challenges, Limitations, and Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Hu et al. (2025) [3] | Digital Twin-based fault diagnosis of electric machines | Difficulties in real-time synchronization and handling multivariable interactions |

| Ren et al. (2022) [8] | Ontology-based data governance for DT lifecycle management | High data evolution complexity; need for robust semantic architectures |

| Leng et al. (2021) [4] | Review of DT-based smart manufacturing systems in Industry 4.0 | Issues of data consistency, integration, and industrial scalability |

| Santander et al. (2023) [17] | Deep Learning integrated into MPC frameworks | Scalability for large-scale systems; high computational demand |

| El Hakim et al. (2025) [20] | AI-enhanced MPC for nonlinear LPG processes | Limited generalizability; requires validation on broader chemical systems |

| Herrera et al. (2023) [32] | Hybrid controller for long-time delays in chemical processes | Complexity of tuning; sensitivity to parameter uncertainty |

| Teng et al. (2021) [7] | DT infrastructures for industrial energy efficiency | Sensor calibration issues; high demand for real-time processing |

| Chen et al. (2025) [18] | DT-enabled MPC with deep neural networks for real-time control in additive manufacturing | High computational load; sensitivity to data drift; scalability for large-scale MIMO processes |

| This work | Hybrid DT and MPC + GA + NN controller for nonlinear MIMO process automation | Hybrid control increases modeling and computational accuracy; real-time hardware implementation and long-term robustness testing represent the next steps of development |

Thus, the literature reviewed demonstrates a strong trend toward merging digital twins, predictive control, and artificial intelligence algorithms. Despite significant progress, many existing solutions still fail to meet the adaptability and scalability requirements of dynamically changing industrial processes. This work aims to address these limitations by developing a hybrid control architecture that combines a digital twin, predictive control, a genetic algorithm, and a neural network (see Figure 1), using the example of the control problem of an orthophosphoric acid purification process, a typical chemical engineering facility with pronounced nonlinearity and multiple inputs/outputs.

3. Methodology of Proposed Efficient Control Algorithm

Modern MIMO system control challenges require the integration of intelligent approaches capable of considering both the physical model of the object and nonlinear, partially observable, or uncertain dynamic characteristics. This paper proposes a predictive control algorithm that combines a linear state-space model, neural network correction, and genetic optimization of control actions. The algorithm is implemented in a digital twin environment, enabling safe testing and adaptation of control strategies in real time [11].

The development of the algorithm includes four main stages that form a complete closed-loop control system:

- Input System Data, ISD—formation and pre-processing of input data: collection of measurements, normalization, filtering and preparation for modeling;

- Modeling and Learning, ML—building a mathematical model and training a neural network on prepared data, followed by integration into a digital twin to improve the accuracy of predictions;

- Optimization Process, OP—forecasting the dynamics of the system, calculating the optimal trajectory of control actions taking into account constraints; decomposing control into the main and corrective components;

- Feedback and Performance Adjustment, FPA—applying control signals to an object, updating the state of the digital twin, shifting the forecast horizon and adjusting parameters based on the actual error.

This phased architecture enables the implementation of a control algorithm that is resilient to uncertainties and changing environmental conditions. The use of a digital twin enables safe testing of various scenarios and preliminary optimization before implementing solutions in a real production environment.

3.1. Data Entry and Pre-Processing Stage (ISD)

The first stage of hybrid predictive control involves collecting and generating input information necessary for constructing a predictive model and implementing an optimization cycle. The initial information is the current operational measurements of the MIMO system, obtained in real time from the production object. Key variables at this stage include: is a vector of measured output variables reflecting the dynamic behavior of the controlled object; is a vector of control actions applied to the system; is a vector of set output values that determine the desired control trajectory; is a set of constraints on variables and , which define the permissible operating regions of the system.

Before data is fed into the MPC, mandatory pre-processing is performed, including:

- Scaling (normalization) of all variables into a unified numerical range (for example, [0, 1]), which is necessary to ensure the correct operation of neural network components and the stability of numerical optimization procedures;

- Filtering noise and outliers in measured data, allowing for increased forecast accuracy and stability of control actions;

- Validation and verification of data completeness, including checking for omissions, outliers, and consistency between measurement channels.

A cleaned, normalized input vector goes to the MPC predictor/optimizer, improving data quality and controller reliability. ISD ties plant data to the predictive controller and provides the inputs used by the digital twin.

3.2. Mathematical Model and Forecast with Neural Network Correction (ML)

Predictive control refers to a class of modern control strategies in which an optimal control problem is solved at each time step over a finite horizon [11,16]. The basic formulation of MPC begins with a discrete state-space model of the control object, which is developed based on the physical processes of the control system and the processed data:

where is discrete time; is the system state vector; is the control vector; is a vector of output variables; and are matrices obtained as a result of identification or linearization.

However, real technological processes formalized in a digital twin often exhibit pronounced nonlinear and multidimensional dynamics due to changes in raw material composition, concentrations, temperatures, and other factors. In this case, a generalized nonlinear model is used:

where are environmental disturbances (e.g., fluctuations in raw material quality or external noise).

Since classical MPC requires a linear model, the system is linearized in the vicinity of the selected operating point using Jacobians:

After obtaining a linear discrete form at the selected sampling step a model is constructed for use in MPC [37].

Thus, the nonlinear model provides an adequate description of the process within the digital twin, and its linearized form is used at the MPC level for predictive control and optimization. Based on model (1), the MPC calculates the trajectories of the system’s future behavior over the forecast horizon [6]:

To improve the accuracy of predictions, a neural network (NN) is embedded into the model, which adjusts the dynamics by taking into account nonlinear dependencies and effects not described by the linear model. The NN acts as a predictive model [18]:

where are parameters of the trained network.

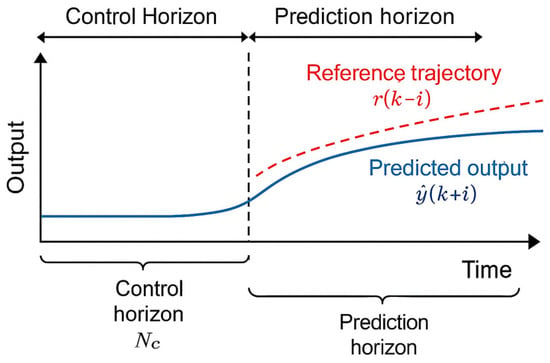

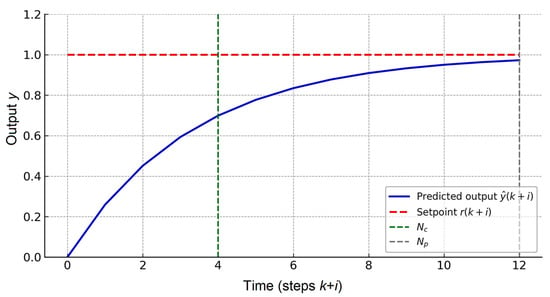

This approximation is used within the optimization procedure to obtain a more accurate forecast of the object’s dynamics. The forecast horizons and control horizons define the interval over which the forecast is calculated and the sequence is optimized (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of MPC operation.

The graph shows a comparison of the predicted output (blue line) with the reference trajectory (red dashed line). The vertical lines indicate the horizons: —control horizon (the length of the optimized sequence of control actions); p—forecast horizon (the length of the interval over which the functional is minimized).

Below is a step-by-step Algorithm 1 that summarizes the procedure for preparing data and building a model for implementing hybrid MPC within the framework of a digital twin.

| Algorithm 1 Data Preparation and Model Linearization Procedure for MPC with Digital Twin |

| Input: states , inputs , outputs , sampling period , historical dataset Output: cleaned and normalized dataset , linearized discrete-time model , digital twin dataset for training NN and predictive control Begin:

|

Next, based on the resulting model and preprocessed data, an optimization problem is formed, including the calculation of the control sequence, taking into account the constraints. A complete formalization of the problem, as well as the structure of the hybrid controller, is presented in the next section.

3.3. Optimization Process (OP)

At this stage of the control algorithm, optimization of control actions is performed. The canonical formulation of the MPC problem consists of minimizing the objective function on a prediction horizon with control horizon at each time step :

Optimization is carried out under the condition of the execution of the model in the state space (1) and restrictions on the input effects and their increments:

where is a sequence of future control actions on the control horizon; is control increment; are predicted system outputs; are given signals; are weight matrices that prioritize tracking accuracy and control smoothness.

The canonical formulation of the MPC problem is expanded in this paper by integrating hybrid modules [19]. The forecast is refined by a neural network model, and the search for the optimal sequence taking into account (7), is performed by a genetic algorithm [27].

Two different neural networks with similar architectures but different objectives are used: —a model neural network for approximating the model error and refining the output forecast (residual modeling); —executive neural network for generating additional control action (ancillary/policy control).

This separates the “modeling” and “control” functions, eliminating double accounting for the same error. Additionally, the functionality includes penalty terms for neural network correction and its increments, ensuring robustness and predictability of system behavior under uncertainty.

The resulting control law has a hybrid form:

where is the result of global optimization using a genetic algorithm that minimizes the criterion ; is a corrective addition to a neural network model that compensates for the unaccounted dynamics of an object; is the policy of the network , depending on the state estimate and the available context; are parameters of the trained neural network.

The proposed decomposition of the control signal into a GA-optimized component and a NN-based corrective component is intentional. The MPC + GA branch remains the primary optimization layer that guarantees constraint satisfaction and stable behavior in the nonlinear MIMO setting. The neural-network component is not used to generate the full control action; instead, it provides a small, bounded correction compensating for residual nonlinearities and model mismatch. This prevents coupling between prediction and control errors, avoids amplification of modeling uncertainties, and keeps the GA optimization problem low-dimensional. The NN contribution is explicitly regularized in amplitude and rate through the penalty terms, ensuring robustness and preserving the classical MPC structure.

The control action generated by the neural network is assumed to be fixed over the control horizon and is not subject to optimization. This eliminates double-counting of errors and ensures a structural decomposition of the control problem. To restrict the influence of the neural network correction, soft penalty terms are incorporated into the MPC objective function. The extended functionality in this case will be as follows [15,17]:

where is the MPC base criterion; is neural network control augmentation. The coefficients define the penalty weights. The first term limits the amplitude of the neural network component, and the second limits its rate of change. This regularization prevents “aggressive” corrections and facilitates compliance with the constraints on the control inputs.

At each control cycle, the sliding horizon principle is used: the entire sequence is optimized, but in the actual loop, only the first element is used. The system then transitions to state , and the optimization is repeated with updated measurements. For the initial step, the increment is used, where is the last actual signal applied to the object.

To minimize criterion (6) over the control horizon, a genetic algorithm (GA) is used. It generates a set of candidate sequences: , and evaluates their quality using the extended functional , where the forecasts are calculated by a state-space model and a neural network predictor [19,27].

The neural network functions as a predictor and a correction channel: it refines the forecasts of the output variables and generates an additive , that compensates for unmodeled nonlinear dynamics. Training is performed offline based on historical data, and soft retraining in small steps is allowed during operation. The contribution of the neural network channel is limited by penalty terms in the functional, which increases robustness and prevents unwanted sharp corrections [15,17].

Scientific novelty. The proposed hybrid control law is implemented in the form of a hybrid two-branch signal (9), where the first channel is generated by a predictive controller with genetic optimization, and the second represents a small neural network correction. Unlike traditional approaches [22], where penalties are imposed on the overall control signal or model parameters, this paper introduces explicit regularization specifically for the NN additive and its increments. This setup allows controlling the amplitude and rate of change in the trained channel, maintaining its effectiveness as a compensator for the model error and ensuring compliance with constraints and stability margins.

From the point of view of automatic control theory, the proposed approach combines the forecast of a linear model in state space with a small corrective superstructure that functions as an ancillary feedback channel. From the optimal control perspective, the final problem remains a standard MPC problem on a moving horizon: the GA determines the optimal sequence of inputs using the tracking and smoothing functionality, and the neural network refines the trajectory forecast and compensates for nonlinearities to a limited extent. The introduced coefficients guarantee the smallness and limitedness of the neural network impact, which ensures the robustness and predictability of the controller’s behavior in the presence of uncertainties [19,27].

As a result, more accurate tracking of the reference trajectory is achieved while observing the constraints, the technological efficiency of the process is increased, while the structure of the controller remains compatible with the classical principles of stability analysis of closed-loop systems.

3.4. Feedback and Performance (FPA)

The final stage of the predictive control algorithm is the FPA step. It ensures the control loop is closed, the sliding horizon principle is implemented, and the system adapts to current conditions. At this stage, the optimal control action calculated in the previous step is applied to the object, after which the actual process outputs are measured, the model states are updated, and a new optimization problem is generated. Thus, the FPA acts as a feedback mechanism that allows for forecast adjustments and maintains the stability and effectiveness of the regulator in real time [7,9].

After the optimal sequence of control actions is found on the optimization horizon, only its first element is used in the actual circuit. Thus, a signal

consisting of the result of global optimization using a genetic algorithm and a small neural network correction is sent to the object. After applying the control, the actual output of the system is measured and the tracking error is calculated based on it

This error is used to update the model’s state vector, which can be performed either directly via the state Equation (1) or by using an observer if the full state vector is unavailable. In the latter case, the state estimate is refined to account for the discrepancy between the model prediction and the actual output. The optimization horizon then shifts (receding horizon principle): at the next time step, the minimization problem for the extended functional is re-formulated, taking into account updated data and imposed constraints.

Thus, the FPA stage completes the hybrid MPC methodology, providing feedback and continuous updating of control actions. As a result, the proposed algorithm retains the structure of classical predictive control but is supplemented by two modules—global optimization using a genetic algorithm and limited neural network correction—which improves tracking accuracy and system robustness in the presence of nonlinearities and uncertainties.

3.5. Steps of the Hybrid Efficient Control Algorithm

For the practical implementation of the proposed hybrid predictive controller, it is advisable to present its operation as a step-by-step algorithm. This format allows for a clear understanding of the logic of interaction between the main stages and demonstrates how the control action is generated and adjusted in real time. Algorithm 2 includes a sequence of actions from data collection to applying the optimal signal to the control object and shifting the forecast horizon.

| Algorithm 2 Hybrid MPC with Genetic Algorithm and Neural Network Correction |

| Input: Discrete-time state-space model matrices ; prediction horizon (with ); control horizon ; weights ; NN regularization weights ; constraints , GA parameters (population size, crossover and mutation rates, elitism factor); trained NN policy ; previous input ; reference trajectory available on the horizon. Output: Applied control input ; predicted trajectory ; total cost . Initialization: 1. Define the plant state-space model (1); 2. Specify the MPC cost over horizons (6); extend to (9); 3. Initialize NN (architecture, weights ); train offline on historical data; 4. Set GA parameters and hard constraints for inputs and input increments; 5. Initialize observer (KF/EKF/UKF) if the full state is not measured. Repeat at each time step :

|

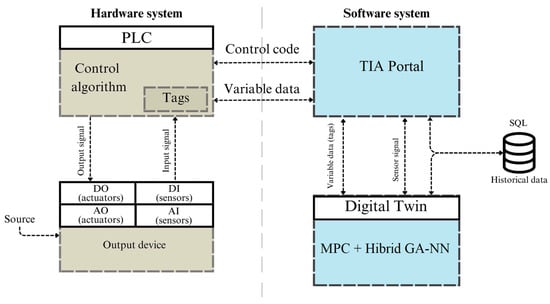

3.6. Digital Twin Implementation

The hybrid predictive control algorithm is integrated into a digital twin linked to the PLC via the Siemens TIA Portal, as shown in Figure 3 [11,16].

Figure 3.

Integration of hardware and software components to implement a control algorithm based on a digital twin.

The PLC executes control code and processes signals from sensors (AI, DI), sending control signals to actuators (AO, DO). Data exchange with the digital twin is accomplished via tags, and historical data is stored in an SQL database and used for model calibration and neural network retraining [11].

The developed hybrid predictive control methodology is fully integrated into this configuration:

- At the ISD stage, the digital twin receives real data from sensors via PLC and tags, performs normalization and validation;

- At the OP stage, the digital twin uses a predictive model, a neural network correction module, and a genetic algorithm to compute optimal control actions taking into account constraints;

- At the FPA stage, only the first element of the optimal sequence is fed to the physical plant, after which the digital twin updates the state of the model and initiates a new optimization cycle.

Thus, the digital twin serves as a link between the methodology and the real system, enabling closed-loop control with prediction and adaptation. Unlike traditional approaches, the proposed approach is not limited to offline modeling alone, but rather ensures continuous interaction between the virtual model and the physical process, significantly increasing the accuracy and reliability of control under uncertainty.

4. Results and Discussion

To test the developed methodology presented in Section 3, it was applied to a real industrial case—the purification process of grade A phosphoric acid (food grade). The phosphoric acid purification process is a typical example of a nonlinear MIMO automation system, characterized by pronounced nonlinearities, multiparameter interactions, and the presence of disturbances. The stringent quality requirements for the final product, as well as the need to ensure sustainability and energy management efficiency, make this facility a prime example of demonstrating the benefits of hybrid predictive control using a digital twin [7,9].

4.1. Process: Experimental Setup

Food-grade orthophosphoric acid is widely used in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. It is produced by precipitating thermal acid impurities as sulfides using hydrogen sulfide formed by reaction with sodium sulfide solution [38].

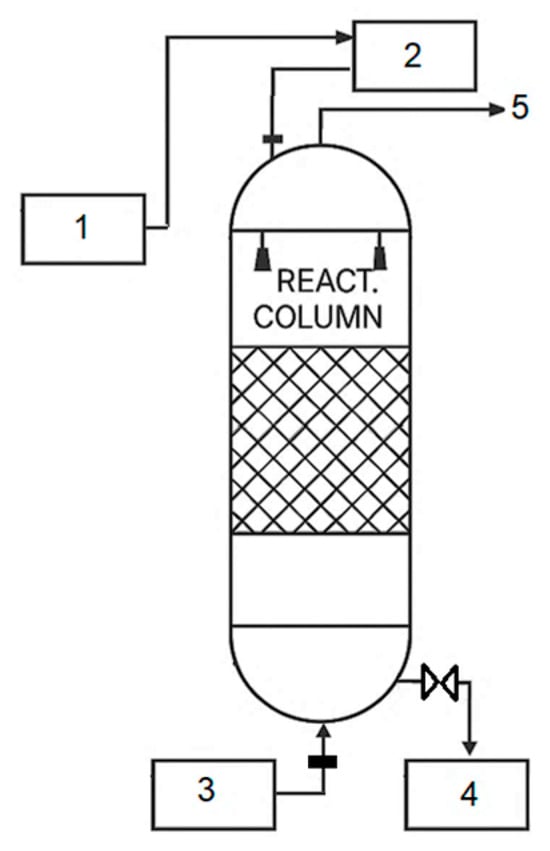

The process takes place in reaction columns (see Figure 4): phosphoric acid ( with a concentration of 74–78% enters the upper part of the column, and a 4–5% solution of sodium sulfide ( is fed to the lower part, supplied in a ratio of 1:(45–50) relative to the acid.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the reaction column: (1) Phosphoric acid tank; (2) Pressure tank; (3) Tank for solution; (4) Tank with phosphoric acid and activated carbon; (5) stream to absorber.

In the lower part of the column (see Figure 4), forms and undergoes sulfide-formation reactions with oxyacids (e.g., ) and phosphate complexes (e.g., ). The products— and —are insoluble and are removed as precipitated solids.

The main chemical reactions [38]:

The precipitation of and is the critical step that controls final product quality. To achieve a phosphoric acid purification rate of greater than to remove and impurities, it is necessary to maintain optimal feed conditions for the reagents , , suspension removal, and the vacuum at the top of the column, . Increasing acid consumption and overall productivity reduces the contact time with c , limiting the completeness of precipitation. This creates a conflict between cleaning depth and productivity, which requires the use of optimal control.

Statement of the problem: Ensure a purification depth of more than , while observing the permissible modes of supply of , , removal of suspension and vacuuming in the column [39].

In accordance with the ISD stage, for the considered task of phosphoric acid purification, the main signals and tags of the digital twin (DT tags) are defined, which include:

- States are the concentrations of the key components of the solution and the volume (or level) at the bottom of the column.

- Controls are the flow rate of the initial acid, the flow rate of the solution, flow rate, or discharge of the suspension, as well as the effect on the vacuum system or auxiliary control actions.

- The measured outputs are process quality indicators used as key performance indicators. Specifically, to monitor purification quality, the output variables characterizing the concentrations of As(III), As(V) and Pb(II), as well as are the current volume or level of the solution—are selected.

- State variables, process outputs and control actions are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Variables and parameters of the model.

Table 2. Variables and parameters of the model.

In accordance with the ML stage, a mathematical model in the form of a system of differential equations based on the laws of material balance and the kinetics of homogeneous–heterogeneous reactions is proposed to formalize the dynamics of the process of purification of orthophosphoric acid [38]:

The first three equations describe the kinetics of formation and distribution of hydrogen sulfide , which enters into precipitation reactions with As and Pb impurities. These are followed by equations for the dynamics of the concentrations of the precipitated substances:

The equation for reflects the change in the volume of the solution in the reaction column due to the difference between the acid feed and the suspension outlet:

The outputs of the model, subject to control and optimization, are:

Kinetics and mass transfer coefficients were identified based on experimental data:

The resulting model adequately describes the process and is used to construct a digital twin and develop a hybrid MPC algorithm [6]. All control experiments described in this work were carried out in a DT environment, where the nonlinear physico-chemical model (Equations (13)–(15)) served as the virtual plant. The PLC structure shown in Figure 3 illustrates the intended implementation architecture, while the results presented in Section 4 correspond to simulations performed on the DT-based mathematical model.

4.2. Results of Applying the Algorithm

This section presents the results of the implementation of an intelligent algorithm for the phosphoric acid purification process. The H3PO4 purification process is a MIMO process and is limited in terms of control actions. Interchannel cross-talk (high sensitivity of impurities to several streams at once), nonlinearities (precipitation reactions, mass transfer, multiphase hydrodynamics) make classical single-channel approaches insufficient.

Figure 5 shows a generalized structural diagram of the implemented system of the optimal control algorithm for the industrial process of phosphoric acid purification, which includes the main control modules.

Figure 5.

Structural diagram of a hybrid MPC system.

The system uses a combination of precise models and neural network corrections to improve forecast accuracy in the face of input data fluctuations and nonlinearities. The Kalman filter (KF) provides a state estimate based on measured outputs, while a digital twin aligns the model with actual process operating conditions. This is especially important in the presence of fluctuations in feedstock composition, nonlinearities, and delays typical of systems with multiphase flows and chemical reactions.

4.2.1. Initialization of the Algorithm

Linearization was performed based on a mathematical model (5)–(11) and a 72 h set of experimental data. The operating point was selected based on average process conditions:

In deviations from the operating point the continuous linear model has the form:

where is a state vector; are control actions; are system outputs (concentrations of ).

Discretization at step is performed through a matrix exponential:

resulting in a discrete model

The numerical matrices are given in Equation (A1). The eigenvalues of the matrix lie inside the unit circle, which confirms the stability of the discrete predictor. This set is then used in the MPC module [7,9].

4.2.2. MPC Cost Function Specification

For optimization, the objective function (6) was used at horizons . This choice reflects the inertial properties of the deposition process: the main changes in the concentrations of As(III), As(V), and Pb(II) occur within h; covers the key transition section of the trajectory, and the shortened increases stability and reduces the dimensionality of the problem. The ratio corresponds to the industrial practice of tuning MPC for moderately fast objects [37].

The weight matrices and regularization parameters (extended formulation (9)) are given as follows:

The Q matrix emphasizes the priority of minimizing and impurities at the output; the matrix limits sharp changes in (especially along the acid supply channels and solution ); the coefficients smooth out the contribution of neural network correction, increasing the robustness and predictability of control.

The selected parameters provide a balance between tracking accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness of the hybrid controller under uncertainties.

4.2.3. Neural Network Initialization and Training

To improve the accuracy of predictions, the MPC circuit uses a neural network module that compensates for nonlinearities and unaccounted disturbances. Specifically, the neural network is used to refine the trajectories of the output variables within the forecast horizon, and also generates a control supplement . As noted earlier in Section 3.3, the hybrid controller employs two distinct neural networks, each fulfilling a different function within the overall control architecture. Although they share the same MLP structure—reflecting the dimensionality and statistical characteristics of the available process data—they are trained independently and optimized for different targets. The network models the residual nonlinear dynamics of the outputs and enhances prediction accuracy, whereas the network generates a small, explicitly bounded corrective control action.

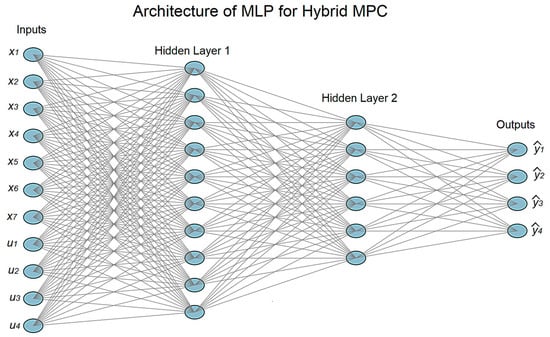

At this stage, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with the input vector is implemented. The trained neural network contains two fully connected hidden layers (10 and 6 neurons, ReLU activation) and an output layer of four neurons for predicting the target output variables (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Multilevel neural network (MLP) architecture for hybrid control.

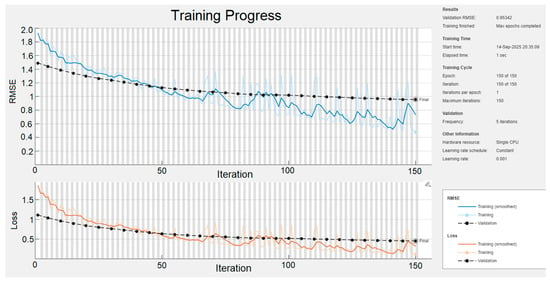

Historical and experimental data from the phosphoric acid purification process were used. All features were normalized to [0, 1]; outlier filtering and gap interpolation were performed. To evaluate performance, the dataset was divided into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets. Training used the Adam optimizer with Dropout and L2 regularization to limit overfitting. Figure 7 shows the graphs of the change in RMSE and the loss function (Loss) for the training and validation sets during the network training process.

Figure 7.

Results of training a neural network for output forecasting.

Analysis of the neural network learning curves (see Figure 7) shows a steady decrease in the root mean square error (RMSE) and the loss function (MSE) throughout all training stages. Initially, the RMSE exceeded 1.0, but by the fiftieth iteration, the error had more than halved, and by the end of training, it had reached values of approximately 0.02–0.05 in normalized coordinates. The MSE curve declines from approximately 0.5 to below 0.01, which is consistent with accurate approximation.

Performance on an independent test set further confirmed the model’s reliability, with the mean absolute error (MAE) below 0.0062 and the Coefficient of Determination exceeding 0.995 for all target variables. The overlap between training and validation curves suggests no overfitting. Overall, the network accurately captures the nonlinear relationships between inputs and impurity concentrations, and is suitable for integration into the MPC circuit as a corrective predictor [15,17].

To illustrate the predictive power of the neural network model integrated into the MPCler, a graph of the output parameter over the forecast horizon was plotted (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Forecast and control horizons in MPC with neural network correction.

In this model, the phosphoric acid purification process is described by a set of mathematical equations and a neural network correction unit. In this case, two key parameters are used: the control horizon , during which the control actions are calculated, and the forecast horizon , over which the forecast of the output product quality is carried out.

Figure 8 shows a typical system output response under the influence of a control action. The blue curve represents the predicted output of the neural network model, and the red dotted line represents the setpoint. The green and gray vertical lines correspond to control horizons of and forecast horizons of , respectively. As Figure 8 shows, the neural network model allows for a fairly accurate prediction of future output parameter behavior, ensuring a timely response from the MPCler. This is especially important in situations where the mathematical model of the process cannot fully account for all nonlinearities and stochastic disturbances. The proposed hybrid approach (physical model + neural network) improves control adaptability and resilience to process uncertainties.

4.3. Control Results and Performance

This section presents the results of applying the proposed control Algorithm 2 to the problem of purifying grade A orthophosphoric acid. The goal of the control is to minimize the concentrations of while observing the limitations on reagent consumption and vacuum.

In chemical processes, it is essential to distinguish between hard and soft constraints. In the proposed MPC + GA framework, hard constraints are imposed on the manipulated variables and their increments, as given in (7). These bounds reflect physical and technological limits of the purification column, including admissible ranges of reagent flow rates, vacuum level, gas supply, and valve positions. They are enforced directly at the chromosome level: the initial population, crossover, and mutation operators generate only feasible candidates within and , while any infeasible individuals are repaired or assigned a very low fitness value and eliminated during evolution.

Soft constraints are associated with desired ranges of impurity concentrations and with the contribution of the neural correction . They are implemented through the penalty terms in the extended objective in (9), where the output weights and the coefficients and limit the amplitude and rate of change in the NN component. Thus, hard constraints are strictly enforced, whereas violations of soft constraints are discouraged by increased cost, leading the GA to favor solutions that satisfy process limits while improving purification efficiency and smoothing control actions.

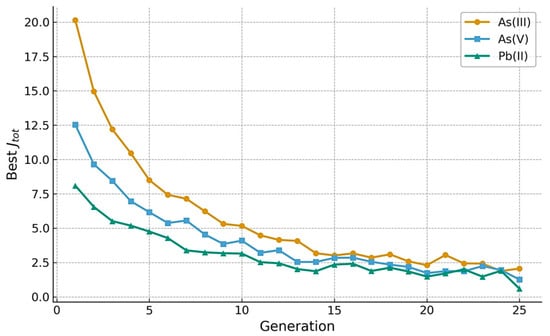

To optimize criterion (6), a standard GA was used (population size 50, crossover probability 0.8, mutation 0.05, elitism 10%, number of generations 25). Figure 9 shows the convergence of the genetic algorithm for three controlled outputs. The best cost stabilizes within 20–25 generations, confirming sufficient optimization depth.

Figure 9.

A GA convergence plot.

Control sequences were formed within the constraints , . The objective function included tracking errors, energy costs, and penalties for excessive adjustments of the neural network channel [19,27].

The additional signal was generated using a multilayer perceptron with 11 inputs , two hidden layers (10 and 6 neurons), and four outputs. The architecture is identical to the network used in the prediction model, but the output neurons are responsible for compensating control actions. Training was performed using Adam and Dropout and L2 regularizations until .

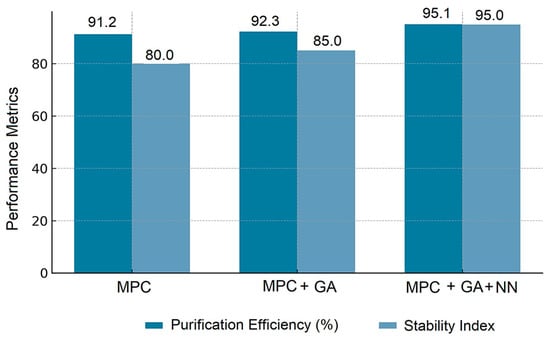

A comparative analysis showed that the baseline MPC achieved a 91.2% cleaning rate, the addition of GA increased the result to 92.3%, and the integration of NN allowed us to achieve 95.1%. This was accompanied by an 11.4% reduction in the integrated tracking error, a 10–15% reduction in control signal oscillations, and high robustness to noise and model uncertainties.

The baseline MPC in this study is implemented as a standard convex QP formulation, which is appropriate for the linearized model. However, the real purification process is a nonlinear MIMO system, and the resulting optimization landscape is non-convex. In such conditions, QP-based MPC yields only a local optimum, whereas the GA layer performs a global search over the wider control space. This explains why the MPC + GA strategy can outperform the purely linear MPC baseline.

Figure 10 shows the comparative effectiveness of the three strategies in terms of cleaning depth and stability.

Figure 10.

Comparison of control strategies based on performance and sustainability indicators.

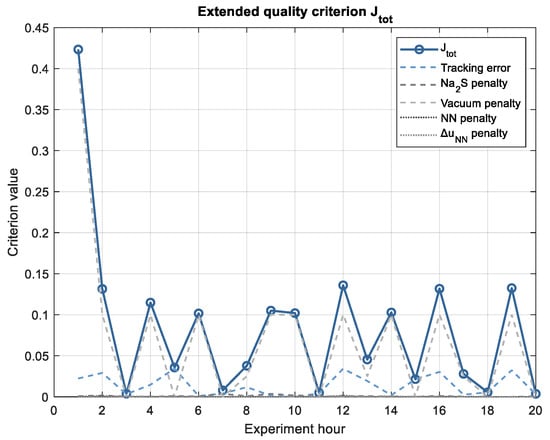

Figure 11 shows the dynamics of the functional and its components during the first 20 h of the experiment.

Figure 11.

Dynamics of the criterion and its components during the experiment.

The graph shows that at the initial stage (the first hours, ISD—ML steps), the contribution of tracking error associated with the system reaching the reference predominates. At the OP stage, adjustments and vacuum maintenance reduce penalties for control actions. When FPA is enabled, the penalties associated with the neural network channel ( and ), remain limited, confirming the correctness of the chosen regularization coefficients. After just 3–4 steps, stabilizes at a low level, demonstrating that the algorithm in rolling horizon mode provides stable cleaning quality with balanced control actions. Thus, the graph illustrates the consistency of operation of all stages of the proposed hybrid MPC [15,17].

It should be noted that the kinetic parameters , identified experimentally at the plant, may vary under real operating conditions. The hybrid structure mitigates this model uncertainty: captures effective nonlinear behavior from DT data, while provides a small bounded compensation for the remaining parameter mismatch.

The optimal parameters ensuring the required quality of control were: flow rate of the initial phosphoric acid—7200 ; flow rate of the Na2S solution—73 ; flow rate of the suspension—7150 ; vacuum—1200 Pa.

Under these conditions, the acid’s purification rate from exceeds 95%, while the quality criterion values remain stable under external disturbances and changes in the feedstock composition. This confirms that the hybrid MPC algorithm with GA + NN correction ensures both high end-product quality and process efficiency through optimal reagent utilization.

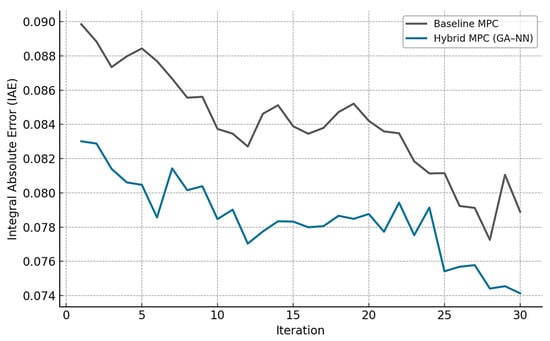

In addition to the purification efficiency, the study included standard control engineering metrics to provide a more rigorous evaluation of setpoint tracking and control effort. To assess overall MIMO tracking performance, the total Integral Absolute Error (IAE) was computed by summing the individual absolute errors for all controlled outputs. This metric consolidates system-level tracking performance and directly compares control strategies. Figure 12 shows the total IAE over time for both the baseline MPC and the proposed hybrid MPC (GA + NN).

Figure 12.

Integral Absolute Error for the controlled states.

As shown in Figure 12, the hybrid MPC with GA + NN achieved an reduction in total IAE compared to the baseline MPC, demonstrating a clear improvement in tracking accuracy.

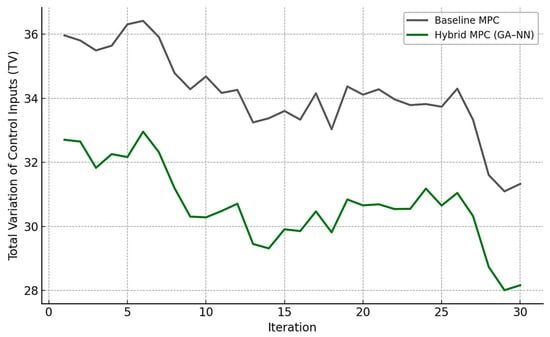

To assess control signal variability and actuator stress, Total Variation () of the control inputs was computed for both strategies, as illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Total variation in control inputs.

The hybrid controller achieved an approximately 13% reduction in the total variation (TV) of the control inputs compared to the baseline MPC, resulting in smoother control actions. In addition to the process KPI (purification efficiency), the total IAE and TV together provide a comprehensive assessment of control quality.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a predictive control algorithm for multivariate industrial processes based on the integration of a digital twin, an MPC, a GA, and NN correction. The developed architecture implements hybrid two-branch control using the ISD–ML–OP–FPA sequence: from data collection and normalization to forecasting, optimization, and online adaptation.

The digital twin not only simulates process behavior but also serves as an active element of the control loop, taking the development beyond traditional digital models. The virtual model is continuously updated based on data from the physical object (via PLC and tags), while the neural network refines predictions and compensates for nonlinear effects. Due to built-in regularization mechanisms, the influence of the learning channel is strictly limited, increasing the robustness and predictability of the controller’s behavior.

Using the example of an industrial process for phosphoric acid purification, it is shown that the hybrid controller achieves a purification degree of up to 95.1% compared to 91.2% for the basic MPC circuit, reduces the amplitude of control signal oscillations by approximately 10–15%, and maintains stability under fluctuations in the composition of the raw material and external disturbances. The approach thus combines the advantages of physical modeling, predictive control, and machine learning methods in a single digital platform and confirms its applicability to intelligent automation tasks where accuracy, compliance with process constraints, and adaptability to changing production conditions are critical.

Further research will focus on developing digital twin methods for more complex MIMO systems with delays and variable structure, formulating multi-criteria settings that combine product quality, energy consumption, and safety, as well as integrating with cloud and edge management and analytics platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S. and B.S.; methodology, O.S. and B.S.; software, O.S. and D.G.; validation, O.S., B.S. and D.G.; formal analysis, O.S. and D.G.; investigation, O.S., B.S. and D.G.; resources, B.S. and D.G.; data curation, O.S. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, B.S.; visualization, O.S. and D.G.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP19674691.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

References

- Feng, X.; Wang, C. Adaptive Tracking Control for a Class of Uncertain MIMO Nonlinear Systems with Input Constraints. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2025, 111, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Davari, H.; Singh, J.; Pandhare, V. Industrial Artificial Intelligence for Industry 4.0-based Manufacturing Systems. Manuf. Lett. 2018, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xiao, H.; Ye, Z.; Luo, N.; Zhou, M. Research and Prospects of Digital Twin-Based Fault Diagnosis of Electric Machines. Sensors 2025, 25, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Wang, D.; Shen, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Digital twins-based smart manufacturing system design in Industry 4.0: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, W.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, I. A hybrid framework of first-principles model and machine learning for optimizing control parameters in chemical processes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 141, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, P.; Gao, S.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Trajectory Tracking Control of Intelligent Vehicles with Adaptive Model Predictive Control and Reinforcement Learning Under Variable Curvature Roads. Technologies 2025, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.Y.; Touš, M.; Leong, W.D.; How, B.S.; Lam, H.L.; Máša, V. Recent advances on industrial data-driven energy savings: Digital twins and infrastructures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Shi, J.; Imran, M. Data Evolution Governance for Ontology-Based Digital Twin Product Lifecycle Management. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, L.; Tangour, F.; El Abbassi, I.; Absi, R. Analysis of Digital Twin Applications in Energy Efficiency: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.; Karrenbauer, M.; Fellan, A.; Schotten, H.D.; Buhr, H.; Seetaraman, S.; Niebert, N.; Bernardy, A.; Seelmann, V.; Stich, V.; et al. A 5G architecture for the factory of the future. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation, Turin, Italy, 4–7 September 2018; pp. 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, M.; Alfian, G.; Fitriyani, N.L.; Rhee, J. Performance analysis of IoT-based sensor, big data processing, and machine learning model for real-time monitoring system in automotive manufacturing. Sensors 2018, 18, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, I.K.; Adekoya, A.F.; Weyori, B.A.; Nyarko-Boateng, O. Applications of artificial intelligence in engineering and manufacturing: A systematic review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1581–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evjemo, L.D.; Gjerstad, T.; Grøtli, E.I.; Sziebig, G. Trends in Smart Manufacturing: Role of Humans and Industrial Robots in Smart Factories. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2020, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sui, F. Digital twin-driven product design, manufacturing and service with big data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 94, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, R.X.; Wu, D. Deep learning for smart manufacturing: Methods and applications. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 48, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wan, J.; Celesti, A.; Li, D.; Abbas, H.; Zhang, Q. Edge computing in IoT-based manufacturing. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, O.; Kuppuraj, V.; Harrison, C.A.; Baldea, M. Deep Learning Model Predictive Control Frameworks: Application to a Fluid Catalytic Cracker–Fractionator Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 11110–11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-P.; Karkaria, V.; Tsai, Y.-K.; Rolark, F.; Quispe, D.; Gao, R.X.; Cao, J.; Chen, W. Real-Time Decision-Making for Digital Twin in Additive Manufacturing with MPC using Time-Series Deep Neural Networks. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi Sarbijan, M.; Behnamian, J. Multi-fleet feeder vehicle routing problem using hybrid metaheuristic. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 141, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hakim, B.A.; Abdel-Goad, M.A.-H.; Awad, M.E.; Shoaib, A.M. AI enhanced model predictive control for optimizing LPG recovery through integrated computational modeling design of experiments and multivariate regression. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z. Time series data for equipment reliability analysis with deep learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 105484–105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Duan, Z. Tube-based model predictive control using multidimensional Taylor network for nonlinear time-delay systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 66, 2099–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, P.; Michailidis, I.; Minelli, F.; Coban, H.H.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Model Predictive Control for Smart Buildings: Applications and Innovations in Energy Management. Buildings 2025, 15, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, P.; Girardin, L.; Ashouri, A.; Maréchal, F. Contribution of Model Predictive Control in the Integration of Renewable Energy Sources within the Built Environment. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Zhang, Y. Research and Application of Predictive Control Method Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for HVAC Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 130845–130852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Mei, X.; Rodriguez, J.; Kennel, R. Model predictive control for electrical drive systems-an overview. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2017, 1, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, H.; Ye, C.; Zhou, H. Synergizing Metaheuristic Optimization and Model Predictive Control: A Comprehensive Review for Advanced Motor Drives. Energies 2025, 18, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Li, S.; He, X.; Xie, C.; He, S.; Xu, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X. Hybrid electric vehicles: A review of energy management strategies based on model predictive control. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Kim, K.; Sung, D.; Kim, K.; Yang, H.; Lee, H.; Cho, G.Y.; Cha, S.W. A Review of Optimal Energy Management Strategies Using Machine Learning Techniques for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2021, 22, 1437–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, A.; Yusupov, Z. Real-Time Capable MPC-Based Energy Management of Hybrid Microgrid. Processes 2025, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, M.; Ay, M.; Bergs, T.; Abel, D. Review on model predictive control: An engineering perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 1327–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Benítez, D.; Pérez-Pérez, N.; Di Teodoro, A.; Camacho, O. Hybrid Controller Based on Numerical Methods for Chemical Processes with a Long Time Delay. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 25236–25253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Al-Nussairi, A.K.J.; Sadeghi Chevinli, Z.; Singh, N.S.S.; Chyad, M.H.; Yu, J.; Maesoumi, M. Integrating digital twins with neural networks for adaptive control of automotive suspension systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Ullah, Z. Deep Learning Based Digital Twins Augmented Reality: Model Predictive Control for Battery and Storage Optimization in Renewable Energy Prosumers Districts. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 117565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, C.; Bicat, D.; Yankov, R.; Arweiler, J.; Koch, R.; Bauer, H.-J. Model Predictive Evolutionary Temperature Control via Neural-Network-Based Digital Twins. Algorithms 2023, 16, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, B.; Su, K.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H. A preliminary study of digital twin for nuclear reactor dynamics: A synergy of machine learning and model predictive control. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 153, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Badgwell, T. A survey of industrial model predictive control technology. Control Eng. Pract. 2003, 11, 733–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafarov, V.V.; Mayorga, B.; Dallos, C. Mathematical method for analysis of dynamic processes in chemical reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1999, 54, 4669–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, R.M. Experiment optimization in chemistry and chemical engineering, S. Akhnazarova and V. Kafarov, Mir Publishers, Moscow and Chicago, 1982, 312 pp. Price: $9.95. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Lett. Ed. 1984, 22, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.