Offboard Fault Diagnosis for Large UAV Fleets Using Laser Doppler Vibrometer and Deep Extreme Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

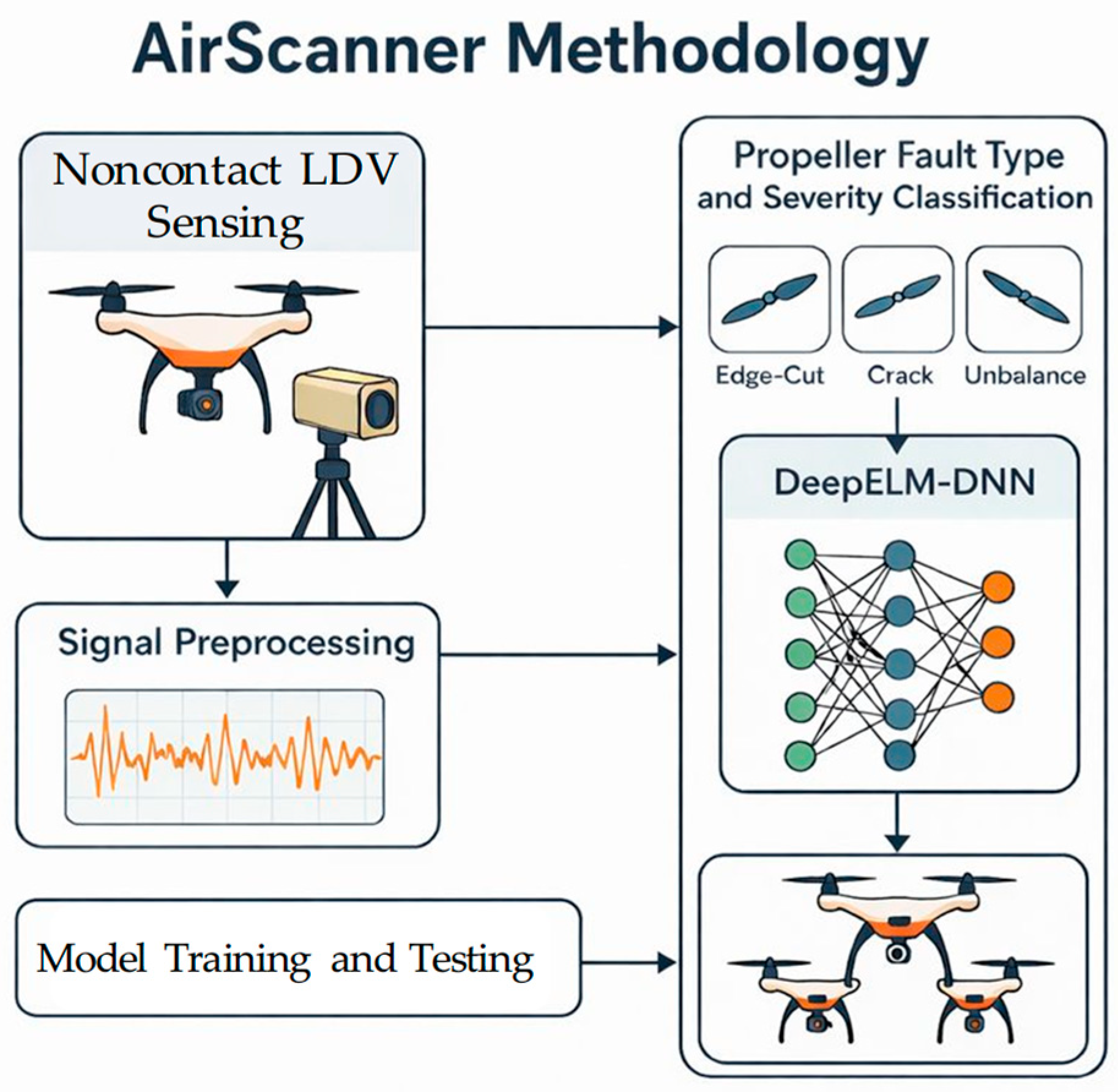

- This study is the first to introduce a portable LDV as a standalone diagnostic tool for UAV propeller health monitoring for a remote and hardware-free inspection without requiring any onboard sensors or flight-controller access.

- A novel DeepELM-DNN is developed to classify both propeller fault type and severity from a single 1 s LDV measurement. The architecture combines multi-layer ELM transformations with deep nonlinear layers.

- The proposed AirScanner system provides higher sensitivity than traditional onboard sensors for early detection of small or emerging propeller defects. This capability addresses a critical gap in smart agricultural robotics for safe operations.

2. Methodology

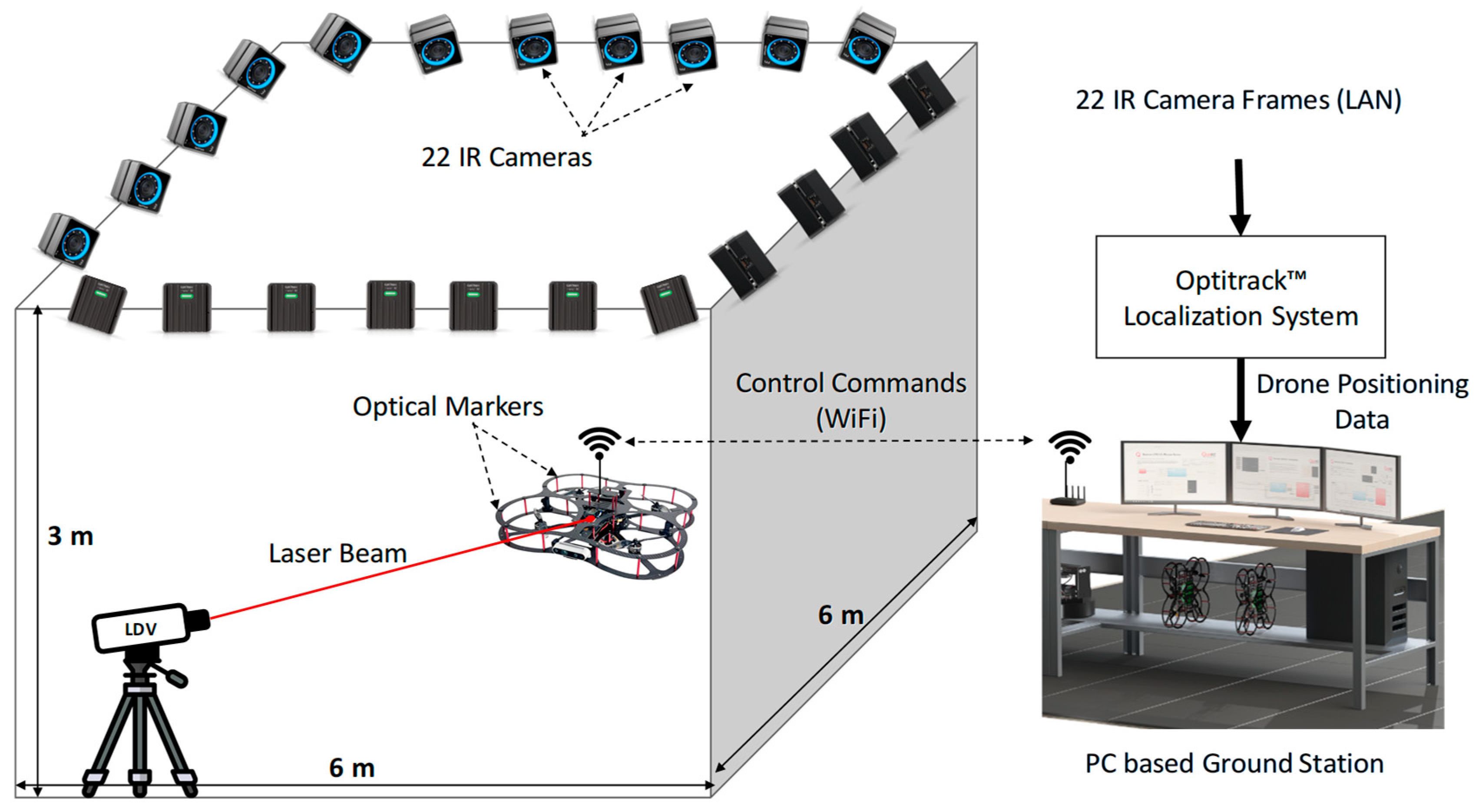

3. The Experimental Work

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Data Visualization

4.2. AI and ML Approach Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, Z.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. UniHSFormer X for Hyperspectral Crop Classification with Prototype-Routed Semantic Structuring. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpathirana, P.P.; Sakai, K.; Jayasinghe, G.Y.; Nakandakari, T.; Yuge, K.; Wijekoon, W.M.C.J.; Priyankara, A.C.P.; Samaraweera, M.D.S.; Madushanka, P.L.A. Evaluation of Sugarcane Crop Growth Monitoring Using Vegetation Indices Derived from RGB-Based UAV Images and Machine Learning Models. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, P.; Dong, X.; Tang, K.; Liang, Z.; Shi, Y. A sustainable crop protection through integrated technologies: UAV-based detection, real-time pesticide mixing, and adaptive spraying. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y. Spraying Technology in Precision Agriculture Aviation. In Precision Agricultural Aviation Application Technology; Lan, Y., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 293–392. [Google Scholar]

- Rajat, K.; Shekhar, K.S.; Tanti, H.A.; Datta, A. UAV Based Farm Inspection using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Applications (MPSec ICETA), Gwalior, India, 21–23 February 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, K.M.S.; Joshi, P.; Subedi, N. Integrating UAV-based multispectral imaging with ground-truth soil nitrogen content for precision agriculture: A case study on paddy field yield estimation using machine learning and plant height monitoring. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Ariyasena, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y. A UAV-based method for root zone soil moisture modeling of different farmland scale with grain and economic crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 321, 109932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, C.; Hajek, M.; Ismail, M.A. Preliminary Safety Assessment for Electro-mechanical Actuation Architectures for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Control and Fault-Tolerant Systems (SysTol), Saint-Raphael, France, 29 September 2021–1 October 2021; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.A.A.; Wiedemann, S.; Bosch, C.; Stuckmann, C. Design and Evaluation of Fault-Tolerant Electro-Mechanical Actuators for Flight Controls of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Actuators 2021, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.J.D.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Parametric aerodynamic characterization of tail geometry variations in fixed-wing UAVs. Aerosp. Syst. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. Improved UAV blade unbalance prediction based on machine learning and ReliefF supreme feature ranking method. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Neranon, P.; Al-Haddad, S.A. Investigation of Frequency-Domain-Based Vibration Signal Analysis for UAV Unbalance Fault Classification. Eng. Technol. J. 2023, 41, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. An Intelligent Quadcopter Unbalance Classification Method Based on Stochastic Gradient Descent Logistic Regression. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd Information Technology to Enhance e-Learning and Other Application (IT-ELA), Baghdad, Iraq, 27–28 December 2022; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. Influence of Operationally Consumed Propellers on Multirotor UAVs Airworthiness: Finite Element and Experimental Approach. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 11738–11745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Mahdi, N.M.; Al-Haddad, S.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Ogaili, A.A.F. Protocol for UAV fault diagnosis using signal processing and machine learning. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaika, Z.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Giernacki, W.; Jaber, A.A.; Boumehraz, M.; Hamzah, M.N.; Flayyih, M.A. Fault Detection and Diagnosis Methodologies for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: State-of-the-Art. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2025, 111, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Hamzah, M.N.; Kraiem, H.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Flah, A. Multiaxial vibration data for blade fault diagnosis in multirotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A. Applications of Machine Learning Techniques for Fault Diagnosis of UAVs. SYSTEM 2022, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, M.; Chen, Z. Vision-based displacement estimation of short- to medium-span bridges using two-stage UAV motion correction. Measurement 2025, 256, 118145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gui, H.; Lu, J.; Tang, X.; Gao, X. Multi-scale feature fusion network with temporal dynamic graphs for small-sample FW-UAV fault diagnosis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 330, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Li, W.; Yuan, F.; Zhi, H.; Gao, Z.; Guo, M.; Xin, B. Research on Fault Diagnosis of UAV Rotor Motor Bearings Based on WPT-CEEMD-CNN-LSTM. Machines 2025, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Song, J.; Cai, G.; Zhao, K. Active Fault-Tolerant Control for Quadrotor UAV against Sensor Fault Diagnosed by the Auto Sequential Random Forest. Aerospace 2022, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Li, B.; Ahn, C.K.; Yang, Y. Prescribed-time extended state observer and prescribed performance control of quadrotor UAVs against actuator faults. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Giernacki, W.; Shandookh, A.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Puchalski, R. Vibration Signal Processing for Multirotor UAVs Fault Diagnosis: Filtering or Multiresolution Analysis? Eksploat. Niezawodn.–Maint. Reliab. 2023, 26, 176318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, S.A.; Al-Muslim, Y.M. Fault diagnosis of actuator damage in UAVs using embedded recorded data and stacked machine learning models. J. Supercomput. 2023, 80, 3005–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczak, M.; Puchalski, R.; Bondyra, A.; Sladic, S.; Giernacki, W. Toward lightweight acoustic fault detection and identification of UAV rotors. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Warsaw, Poland, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 990–997. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. An Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Approach for Multirotor UAVs Based on Deep Neural Network of Multi-Resolution Transform Features. Drones 2023, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Giernacki, W.; Basem, A.; Khan, Z.H.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, S.A. UAV propeller fault diagnosis using deep learning of non-traditional χ2-selected Taguchi method-tested Lempel–Ziv complexity and Teager–Kaiser energy features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Integration of Discrete Wavelet and Fast Fourier Transforms for Quadcopter Fault Diagnosis. Exp. Tech. 2024, 48, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Yu, J.; Tang, D.; Ke, X. Interpretable attention-based prototype network for UAV fault diagnosis under small sample conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 265, 111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chu, H.; Guo, L.; Ge, X. A Weighted-Transfer Domain-Adaptation Network Applied to Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Fault Diagnosis. Sensors 2025, 25, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jia, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Zhao, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. An Integrated Strategy for Interpretable Fault Diagnosis of UAV EHA DC Drive Circuits Under Early Fault and Imbalanced Data Conditions. Drones 2025, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, C.; Zhai, Y. Computationally efficient UAV fault diagnosis with adaptive vibration denoising: A signal processing approach for rotorcraft systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 240, 113413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembe, C.; Halkon, B.J.; Ismail, M.A. Measuring Vibrations in Large Structures with Laser-Doppler Vibrometry and Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Review and Outlook. Adv. Devices Instrum. 2025, 6, 0103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schewe, M.; Ismail, M.A.A.; Zimmermann, R.; Durak, U.; Rembe, C. Flyable Mirror: Airborne laser Doppler vibrometer for large engineering structures. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Proceedings of the 15th International AIVELA Conference on Vibration Measurements by Laser and Noncontact Techniques, Ancona, Italy, 21–23 June 2023; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 2698, p. 012007. [Google Scholar]

- Schewe, M.; Ismail, M.A.A.; Rembe, C. Towards airborne laser Doppler vibrometry for structural health monitoring of large and curved structures. Insight–Non-Destr. Test. Cond. Monit. 2021, 63, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, J.L.; Halkon, B.J. Speaker Diarisation of Vibroacoustic Intelligence from Drone Mounted Laser Doppler Vibrometers. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Proceedings of the 14th International AIVELA Conference on Vibration Measurements by Laser and Noncontact Techniques, Ancona, Italy, 28–29 June 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.A.; Bierig, A. Identifying drone-related security risks by a laser vibrometer-based payload identification system. In Proceedings of the Laser Radar Technology and Applications XXIII, Orlando, FL, USA, 10 May 2018; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; Volume 10636, p. 1063603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Nasimi, R.; Ozdagli, A.; Zhang, S.; Mascarenas, D.D.L.; Taha, M.R.; Moreu, F. Measuring Transverse Displacements Using Unmanned Aerial Systems Laser Doppler Vibrometer (UAS-LDV): Development and Field Validation. Sensors 2020, 20, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhu, W. Development and Validation of a New Type of Displacement-Based Miniatured Laser Vibrometers. Sensors 2024, 24, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, S.A.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. Environmental engineering solutions for efficient soil classification in southern Syria: A clustering-correlation extreme learning approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 2177–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Alawee, W.H.; Basem, A. Advancing task recognition towards artificial limbs control with ReliefF-based deep neural network extreme learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 169, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.; He, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, W.; Ou, W. Deep class-weighted and class-shared dictionary learning for image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 299, 130042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noon, S.K.; Noor, A.H.; Mannan, A.; Arshad, M.; Haider, T.; Abdullah, M. Real-Time Vehicle Sticker Recognition for Smart Gate Control with YOLOv8 and Raspberry Pi 4. Automation 2025, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Desouky, N.; Torky, A.A.; Elbheiri, M.; Eid, M.S.; Ibrahim, M. Toward Autonomous Pavement Inspection: An End-to-End Vision-Based Framework for PCI Computation and Robotic Deployment. Automation 2025, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polytec GmbH. VibroGo® Truly Portable Laser Vibration Measurement—Product Brochure and Datasheet; Polytec GmbH: Waldbronn, Germany. Available online: https://www.polytec.com/fileadmin/website/vibrometry/pdf/OM_PB_VibroGo_E_52042.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- HQProp Hq Durable 7 × 4.5 Propeller Datasheet. Available online: https://www.hqprop.com/hqdurable-prop-7×45-light-grey-2cw2ccw-poly-carbonate-popo-p0205.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Elshaar, M.E.; Ismail, M.A.A.; Abdallah, A.M.; Alqutub, A.M.; Takeyeldein, M.M.; Quan, Q. UAV Propeller: Fault Detection, Characterization, and Calibration: A Comprehensive Study. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 187564–187583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaar, M.E.; Ismail, M.A.; Abdullah, A.M.; Quan, Q. Fault Diagnosis of Drone Propellers using Inner Loop Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD), Barcelona, Spain, 1–3 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.A.; Elshaar, M.E.; Abdallah, A.; Quan, Q. DronePropA: Motion trajectories dataset for defective drones. Data Brief 2025, 60, 111589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaneghaei, M.; Asadi, D.; Mowla, N.; Dişken, G. Experimental motor fault detection and identification of a quadrotor UAV using a hybrid deep learning approach. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 2025, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, N.; Asadi, D.; Sohel, F. Real-time fault detection in multirotor UAVs using lightweight deep learning and high-fidelity simulation data with single and double fault magnitudes. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liang, H.; Wang, R.; Sui, Z.; Sun, Q. Adaptive Event-Triggered Output Feedback Control for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems Using Output Information Only. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 7639–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sun, Q.; Su, H.; Wang, M. Adaptive Cooperative Fault-Tolerant Control for Output-Constrained Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems Under Stochastic FDI Attacks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 6025–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Mahdi, N.M. Efficient multidisciplinary modeling of aircraft undercarriage landing gear using data-driven Naïve Bayes and finite element analysis. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 3187–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Majdi, H.S.; Holovatyy, A.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Giernacki, W. Energy consumption and efficiency degradation predictive analysis in unmanned aerial vehicle batteries using deep neural networks. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Methodology/Application | AI Approach | Key Result/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | Small-sample fixed-wing UAV fault diagnosis using spatio-temporal modeling | Multi-Scale Feature Fusion + Temporal Dynamic Graph + LSTM | Achieved +8% accuracy improvement under limited data; complex architecture requires expensive computation |

| [21] | Rotor motor bearing fault diagnosis under noisy vibration conditions | WPT + CEEMD for denoising, CNN–LSTM hybrid network | 96.67% accuracy; strong generalization but relies on multi-stage signal preprocessing |

| [22] | Quadrotor control with robustness to sensor degradation | Auto Sequential Random Forest | Demonstrated reliable detection for rotor sensor faults; feature-dependent and sensitive to noise |

| [23] | Actuator fault diagnosis with guaranteed performance bounds | Prescribed-Time ES Observer + Prescribed Performance Control | High tracking accuracy under actuator faults; observer gains difficult to tune for varied flight conditions |

| [24] | Vibration analysis for multirotor UAV fault identification | Filtering vs. Multi-Resolution Analysis comparison | Showed superiority of multi-resolution methods; lacks modern deep learning integration |

| [25] | Actuator damage diagnosis using onboard telemetry | Stacked ML models (RF, SVM, KNN ensembles) | High accuracy using embedded data; limited interpretability and moderate computational load |

| [26] | Acoustic-based UAV rotor fault detection | Lightweight ML framework for acoustic signatures | Enables low-cost airborne acoustic diagnosis; sensitive to ambient environmental noise |

| [27] | UAV fault diagnosis using wavelet-based multi-resolution features | Deep Neural Network on transformed features | Improved classification accuracy; feature extraction still hand-crafted |

| [28] | UAV propeller fault diagnosis using non-traditional statistical complexity measures | Deep Learning on Taguchi-tested Lempel–Ziv + Teager–Kaiser features | High robustness to non-stationary signals; requires computationally heavy feature engineering |

| [29] | UAV diagnosis using hybrid time–frequency domain analysis | Discrete Wavelet + FFT integration | Enhanced resolution of fault signatures; lacks end-to-end learning capability |

| [30] | Small-sample UAV diagnosis with interpretability | Attention-based Prototype Network | Improves transparency under limited datasets; accuracy depends on properly chosen prototypes |

| [31] | Cross-domain UAV fault diagnosis | Weighted-Transfer Domain-Adaptation Network | Strong transferability to unseen domains; requires source–target similarity for optimal performance |

| [32] | Early fault detection in UAV EHA DC drive circuits | Integrated Boosting + Bayesian Network interpretability | Excellent performance on imbalanced and early-stage faults; requires engineered features |

| [33] | Robust diagnosis under mixed Gaussian–impulsive noise | ADTCWT + KCDCS optimization + DAW-GBE | 96.1% accuracy and strong noise robustness; preprocessing pipeline is computationally intensive |

| Study | Scope | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| C. Rembe et al. (2025) | Structure Health Monitoring | [34] |

| M. Ismail et al. (2023) | Vibration Measurement | [35,36] |

| J. Richmond and B. Halkon (2021) | Vibroacoustic Intelligence | [37] |

| P. Garg et al. (2020) | Displacement Measurement | [39] |

| M. Ismail and A. Bierig (2018) | Drone Payload Estimation | [38] |

| Study | Scope | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Concept | Based on IMU signals or flight dynamics data processed in real time onboard the UAV or analyzed after landing. | Based on external hardware and sensors, such as ground-based testing equipment or portable LDV, as proposed in this paper. |

| Advantages | It is relatively easy to implement when onboard resources are available. It also does not require additional external hardware or sensors. | The same equipment can be used across a large fleet of drones. No dedicated onboard computational resources are required for non-critical (degradation-type) fault detection. It is applicable to a wide range of commercial drones, independent of closed onboard architectures. |

| Limitations | Requires additional onboard hardware resources (memory and processing capability, e.g., AI boards). Most commercial drones have closed hardware architectures that do not support third-party fault detection algorithms. | Primarily suited for degradation faults that are not safety-critical. Safety-critical faults must still be detected and managed onboard. Fault detection is not available during all flight phases, which may limit early detection. |

| Parameter | DNN-A | DNN-B | DNN-C | DNN-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Hidden Layers | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Neurons per Hidden Layer (Layer 1–4) | 256–128–64–32 | 300–150–75–30 | 200–140–80–40 | 180–120–60–20 |

| Activation Functions | ReLU (hidden), Softmax (output) | |||

| Weight Initialization | Randomized (ELM) | |||

| Bias Initialization | Random uniform | |||

| Training Type | ELM-based closed-form output weights | |||

| Optimizer (Fine-Tuning) | Adam | |||

| Learning Rate | 0.001 | |||

| Batch Size | 32 | |||

| Epochs | 50 | |||

| Loss Function | Categorical Cross-Entropy | |||

| Input Dimension | 5000-sample LDV segment | |||

| Output Classes | 10 | |||

| Regularization | Dropout 0.2 | |||

| Validation Split | 80/20 | |||

| Validation Strategy | Stratified Hold-Out (80% Training/20% Testing) | |||

| Feature Name | Description of the Feature |

|---|---|

| Mean | Average amplitude of the vibration signal; indicates overall signal level. |

| Root Mean Square (RMS) | Energy-related measure reflecting the effective vibration intensity. |

| Standard Deviation | Measures signal variability around the mean. |

| Variance | Represents signal dispersion and noise distribution. |

| Peak Value | Maximum absolute amplitude within the signal segment. |

| Crest Factor | Ratio of peak to RMS; identifies impulsive events and cracks. |

| Skewness | Measures asymmetry of the signal distribution. |

| Kurtosis | Reflects the “peakedness” of the distribution—sensitive to faults. |

| Shape Factor | RMS divided by mean absolute value. |

| Impulse Factor | Ratio of peak value to mean absolute amplitude; highlights sudden high-intensity impulses typical of edge-cut or crack faults. |

| Margin Factor | Detects abrupt high-amplitude deviations. |

| Energy | Total signal energy; increases under unbalance or cracks. |

| Entropy | Irregularity and complexity of the vibration waveform. |

| Metric | Description and Purpose of Use |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | Overall proportion of correctly classified samples. |

| Precision | Probability that predicted faults are correct; measures false-alarm control. |

| Recall | Ability to detect actual faults; controls missed detections. |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall; balances both error types. |

| Specificity | Ability to correctly classify healthy samples. |

| AUC–ROC | Probability that the model ranks a random fault higher than a random non-fault. |

| Specification | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Frame Size | 50 × 50 × 15 | Cm |

| MTOW | 1.504 | Kg |

| Payload | 0.3 | Kg |

| Endurance | 7 | Min |

| Propeller | HQ Durable Prop 7 × 4.5 | - |

| Battery | 4S 14.8 V LiPo/3700 mAh | - |

| Fault Type | Severity Levels and Code | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Edge = Cut | Low–F1SV1 | 1 × 2 mm arc |

| Medium–F1SV2 | 1 × 5 mm arc | |

| Large–F1SV3 | 2 × 5 mm arc | |

| Crack | Low–F2SV1 | 1 × 10 mm crack |

| Medium–F2SV2 | 2 × 10 mm crack | |

| Large–F2SV3 | 3 × 10 mm crack | |

| Surface Unbalance | Low–F3SV1 | 1 × 6 mm hole |

| Medium–F3SV2 | 2 × 4 mm hole | |

| Large–F3SV3 | 3 × 4 mm hole |

| Metric | DNN-A | DNN-B | DNN-C | DNN-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | 96.8 | 95.9 | 97.9 | 94.2 |

| Precision (%) | 96.1 | 95.4 | 98.3 | 93.5 |

| Recall (%) | 97.0 | 96.2 | 98.7 | 94.1 |

| F1-Score (%) | 96.5 | 95.8 | 98.5 | 93.8 |

| Specificity (%) | 95.4 | 94.7 | 97.6 | 92.3 |

| AUC–ROC | 0.972 | 0.963 | 0.987 | 0.948 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ismail, M.A.A.; Kurdi, S.T.; Albaraj, M.S.; Rembe, C. Offboard Fault Diagnosis for Large UAV Fleets Using Laser Doppler Vibrometer and Deep Extreme Learning. Automation 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010006

Ismail MAA, Kurdi ST, Albaraj MS, Rembe C. Offboard Fault Diagnosis for Large UAV Fleets Using Laser Doppler Vibrometer and Deep Extreme Learning. Automation. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsmail, Mohamed A. A., Saadi Turied Kurdi, Mohammad S. Albaraj, and Christian Rembe. 2026. "Offboard Fault Diagnosis for Large UAV Fleets Using Laser Doppler Vibrometer and Deep Extreme Learning" Automation 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010006

APA StyleIsmail, M. A. A., Kurdi, S. T., Albaraj, M. S., & Rembe, C. (2026). Offboard Fault Diagnosis for Large UAV Fleets Using Laser Doppler Vibrometer and Deep Extreme Learning. Automation, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010006