Abstract

This paper proposes an improved seamless fabric production line and its mathematical models before and after optimization to enhance production efficiency and material utilization in textile manufacturing. By adjusting the production process of the seamless fabric production line and formulating corresponding mathematical models for equipment selection and other related issues before and after the modifications, this study aims to increase the number of products produced per unit time and reduce the material consumption per unit product. Experimental results show that the optimized seamless fabric production line achieves a 0.98% to 71.70% increase in production output per unit time and reduces raw material consumption by 9.55% to 10.63%. Future research can further explore the impact of additional variables on production line efficiency to refine and optimize the workflow further.

1. Introduction

Seamless garments employ advanced seamless knitting technology to produce garments directly through knitting, thereby eliminating the traditional processes of cutting and sewing. This technique results in garments without side seams and enables a seamless connection between different fabric structures and raw materials, thus enhancing both fit and comfort. Moreover, the one-step forming characteristic of seamless knitting omits the entire fabric weaving process and streamlines portions of the cutting and sewing operations, reducing raw material waste and labor costs during production. As a technologically advanced sector within the new apparel industry, seamless garments represent one of the strategic directions for upgrading traditional apparel manufacturing [1].

Seamless garment production, as a technology-intensive sector, is emerging as a key avenue for the modernization of the traditional apparel industry. According to the “Analysis of the Development Trends and Investment Prospects of the Chinese Seamless Garment Industry” report, the seamless garment market in China is currently in its infancy, accounting for only approximately 5% of the overall apparel industry, which suggests significant growth potential in the future [2].

Numerous scholars worldwide have proposed various solutions for the optimization of textile production lines. For instance, Woo-Kyun Jung and colleagues proposed a method that utilizes real-time monitoring systems to collect information for optimizing fabric production lines [3]. Tatiana Victorovna Morozova and her team introduced an energy system optimization approach for textile production lines based on a combined heat and power (CHP) system [4]. Ihsan Elahi and collaborators developed an evolutionary algorithm aimed at optimizing multiple water usage indicators in textile dyeing processes [5].

While these approaches effectively address the challenges encountered in optimizing production lines within the traditional textile industry, they predominantly focus on conventional apparel and fabric production lines. As a result, they are insufficiently tailored for the specific optimization needs of seamless fabric and garment production lines, thereby limiting their integration into current seamless manufacturing practices. To bridge this gap, this study integrates production scheduling optimization algorithms to propose a novel, improved production line and its corresponding mathematical model. The objective is to enhance production efficiency and reduce material consumption in seamless fabric production lines.

2. Related Technology Background

2.1. Seamless Fabric Production Line Process

In order to complete the entire production process from raw materials to finished products, textile production lines typically encompass the following segments: yarn processing, fabric production, wet processing, and garment manufacturing. Each of these segments follows its own production procedures. Generally, a textile production line includes the following operations:

- Fiber Production: This operation is responsible for producing the textile fibers required for fabric production (such as natural fibers like cotton and linen, as well as synthetic fibers like nylon, acrylic, and spandex).

- Spinning: This process converts the fibers produced in the previous step into yarn using spinning equipment (e.g., spinning machines) required for fabric production.

- Fabric Weaving/Knitting: In this stage, the yarn is transformed into fabric suitable for garment production. Depending on the direction of manufacture, the process can be categorized as warp knitting or weft knitting, with warp knitting machines generally used for the former and circular or flat knitting machines for the latter.

- Fabric Finishing: This step involves treating the woven or knitted fabric—such as removing impurities, desizing, or bleaching—to prepare it for subsequent processes.

- Printing and Dyeing: This operation applies colors and patterns to the treated fabric.

- Post-Finishing: This process provides the fabric with functional treatments (for instance, spraying chemical agents to render the fabric waterproof, antibacterial, or wrinkle-resistant).

- Garment Sewing: This stage sews the finished fabric into garments. After cutting, joining, and sewing, the various parts of the fabric (such as sleeves, body tubes, and bra straps) can be stitched together to form a complete garment.

- Transportation and Sales: This final phase involves the distribution and sale of the completed products [6].

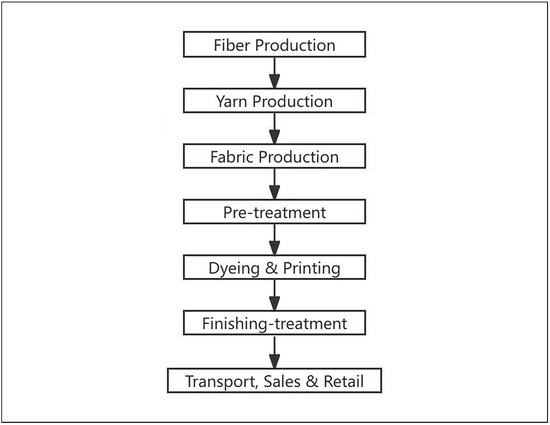

The whole production process of the traditional textile industry can be illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General workflow of traditional textile industry.

As depicted in Figure 1, the production process is divided into several sections: Pre Production (including fiber production and spinning), Production Preparation (comprising fabric weaving/knitting and fabric finishing), Wet Processing (which includes printing/dyeing and post-finishing), Production (garment sewing), and Post Production (transportation and sales).

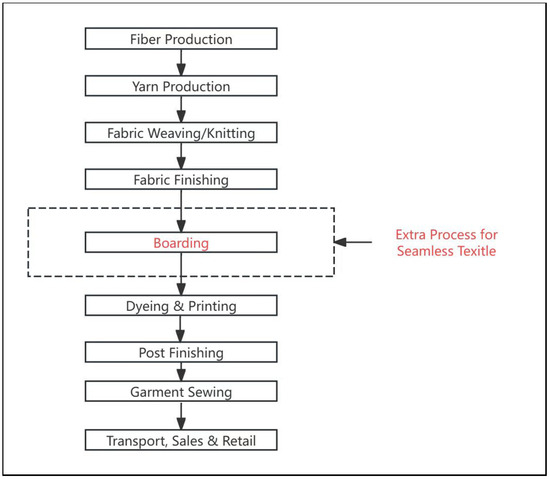

The process for seamless fabric production differs in that, after the fabric finishing stage, a boarding operation is introduced. This operation utilizes boarding equipment to set the finished fabric to the required dimensions. The boarding process constitutes a vital step in a seamless fabric production line. It serves to avert dimensional shrinkage of the original tubular fabric produced by the circular knitting machine, or alternatively to expand it to a prescribed size [7]. In addition, the high temperature applied during the boarding step alleviates residual internal stresses within the fibers, thereby enhancing the tactile quality (hand feel) of the fabric. The seamless fabric production process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Workflow of seamless fabric production, the process in red color is the extra process for seamless textile.

2.2. Production Line Mathematical Modeling Algorithms

To obtain the optimal solution for improving production efficiency and reducing material consumption in seamless fabric production lines, it is necessary to employ search algorithms.

Currently, various algorithms have been applied in the textile industry, including Tabu Search, Simulated Annealing, and Genetic Algorithms and other algorithms like Reinforcement Learning, Linear Programming, etc. Based on the current application scenarios and optimization requirements of the seamless fabric production line, the scheduling optimization algorithm in this study is selected primarily from among Tabu Search, Simulated Annealing, and Genetic Algorithms. These algorithms have demonstrated strong performance in similar manufacturing scheduling problems and are well-suited to the characteristics of the current production process.

Compared to Tabu Search and Simulated Annealing, Genetic Algorithms have a higher chance of finding a global optimization solution: Their population-based search mechanism enables broader exploration of the solution space, making them less prone to becoming trapped in local optima and more adaptable to dynamic or evolving constraints in real-world textile production scenarios. Thus, given the large amount of key data and the complexity of the optimization problem inherent in seamless fabric production lines, this study employs a Genetic Algorithm (GA) for scheduling optimization.

The Genetic Algorithm mimics the natural reproductive process by generating a population of candidate solutions, which are then evolved through crossover and mutation operations to produce new solutions. An evaluation function is used to calculate the fitness of these new solutions, ultimately yielding the optimal solution [8]. GA is characterized by its robust search capability, wide applicability, and its effectiveness in solving complex function optimization problems. In the textile industry, GA is primarily applied to scheduling optimization and the generation of printing patterns [9,10]. The general steps of the algorithm are as follows [11]:

- 1.

- Population Initialization:

For the given optimization problem, a set of initial solutions (individuals) is randomly generated based on the function and its variables, forming the population. Each individual represents a potential solution, typically encoded as binary strings, real-number vectors, or other formats.

- 2.

- Fitness Evaluation:

The fitness of each individual is computed according to the problem’s objective function to assess the quality of the solution. Higher fitness values increase the likelihood that the corresponding individual will be retained.

- 3.

- Selection:

Based on the fitness values, superior individuals are selected from the current population to serve as parents. Common methods include roulette wheel selection (where individuals with higher fitness have a higher probability of being chosen), tournament selection (where several individuals are randomly selected and the one with the highest fitness is retained), and elitism (where the best individuals are directly carried over to the next generation).

- 4.

- Crossover:

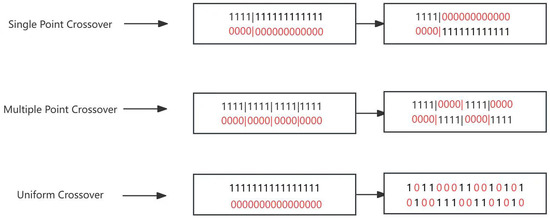

Parent individuals undergo genetic recombination (crossover) to generate new offspring. Common crossover methods include single-point, multi-point, and uniform crossover. For example, Figure 3 illustrates three typical crossover methods for solutions encoded in binary format.

Figure 3.

3 Classical methods of crossover. The red and black numbers represent the data from two parent data that undergo crossover.

- 5.

- Mutation:

Certain values in the offspring solutions are randomly altered (e.g., by flipping binary bits or adjusting real numbers) to increase population diversity and prevent premature convergence to local optima. To maintain the overall fitness of the offspring, the mutation probability is typically kept low (around 1–5%).

- 6.

- Termination Condition Check:

Steps 2 through 5 are repeated until a termination condition is met (such as reaching the maximum number of iterations, stabilization of fitness values, or attainment of a satisfactory solution).

- 7.

- Output the Result:

The best individual from all generations is output as the final solution.

3. Model Formulation

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn. Assume that in the textile workshop there are m machines and n boarding machines. Each machine is capable of processing fabrics of various sizes and materials, and the boarding machines can standardize fabrics processed by the machines within a specified size range to a uniform size. When a single machine processes different fabrics consecutively, the equipment changeover preparation time (such as preheating and mold replacement) must be taken into account. Upon receipt of a batch of orders, the challenge is to determine the optimal allocation of machines (the equipment selection problem) and the processing sequence of the orders (the job sequencing problem) to enhance production efficiency and reduce material input. Moreover, fabrics of the same material and size can be processed on multiple machines concurrently, meaning that an order may be split into several sub-orders for simultaneous processing (the production batching problem).

Based on the analysis above, the scheduling problem can be described as follows: In a textile workshop environment, each of the orders can be divided into processing batches of unequal quantities. All processing batches must be processed consecutively over stages, with each stage having identical machines operating in parallel. The scheduling scheme must consider order batching, equipment constraints, and target processing dimensions to partition the fabric from a given order into batches and select the appropriate equipment, while determining the start times of the processing operations for each of the orders such that a particular performance indicator of the system (for example, the minimum processing time to complete a batch of fabric) is optimized.

Since the objective functions and constraints in the production scheduling problem can mostly be linearized, linear programming (LP) is therefore used for solving the optimization problem in the experiments.

The following assumptions are made:

- Orders are segmented into sub-batches of equal quantities (although the number of sub-batches may vary).

- Workpieces within each sub-batch are processed consecutively without interruption.

- There is no shortage of raw materials.

- The processing time for each machine is constant, and machines do not experience breakdowns.

- The equipment buffer is assumed to be infinitely large, and order transfer times are not considered.

- The setup time for switching between different types of workpieces on a machine is considered; if not specified, it is set to zero.

Based on these model assumptions and the characteristics of the problem, the following parameters and decision variables are defined, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Description of symbols.

The primary objective of scheduling optimization in a textile workshop is to minimize production time. Enhancing production rate improves equipment utilization, thereby boosting the competitiveness of the enterprise. Therefore, when scheduling workpieces, the total number of products in an order is fixed, and the objective is to minimize the maximum completion time (i.e., maximize the production rate). The optimization model is formulated as follows:

Equation (1) represents the objective function of the model. It has the following constrains: if a sub-batch P skips the subsequent process—meaning that the setting operation is not performed and the fabric dimensions remain unchanged, the following constraint applies:

Due to size constraints in the equipment’s capability, sub-batch p cannot be processed if it falls outside the allowable size range. Therefore, Constraints (3) and (4) define the permissible size range for sub-batch p after processing on equipment k, as outlined below:

To ensure that the size of sub-batch p after all processing operations meets the target size, the following constraint is established:

When seeking the optimal solution, the completion time of an order must be greater than the completion processing time of the last sub-batch in all its processing operations; therefore, the following constraint is required:

During the optimization process, if a sub-batch in a certain operation is not processed on equipment k, both its start processing time and completion processing time should be set to zero, i.e.,

If sub-batch p is processed on equipment k, its start processing time must be not less than zero, i.e.,

If sub-batch p is processed on equipment k, its completion processing time must be not less than the sum of its start processing time and processing time; therefore, the following constraint is established:

When both sub-batches p′ and p are processed on the same equipment k, the start processing time of the latter must be greater than the sum of the completion processing time of the former and the mold changeover time. Thus, the following constraint is established:

Since the production process operates in a pipeline manner, the next operation can only start after the previous one has been completed; therefore, the start processing time of the subsequent operation on k equipment must be greater than the completion processing time of the preceding operation, i.e.,

After completing the production of the entire order, the total quantity of all sub-batches must be equal to the total production quantity of the order, i.e.,

For the current production line scheduling optimization problem, to simplify the production process, the following constraint is added: each sub-batch will be assigned to one and only one piece of equipment for processing, i.e.,

Finally, the following constraints define the allowable ranges for the decision variables:

4. Production Line Instance Optimization and Result Analysis

This study uses the seamless fabric production line of Knitting Enterprise X as an example. In this enterprise’s textile workshop, there are 30 machines and 2 boarding machines. The processing information for fabrics by the machines is provided in Table 2, and the time required for the boarding machines to shape fabrics within different size ranges is shown in Table 3. Other parameters are as follows: the mold changeover time for machines is 600 s, the fabric can be divided into at most 5 processing sub-batches, and each sub-batch contains an equal quantity.

Table 2.

Machine Processing Information.

Table 3.

Boarding Machine Boarding Time for Fabric Sizes (s).

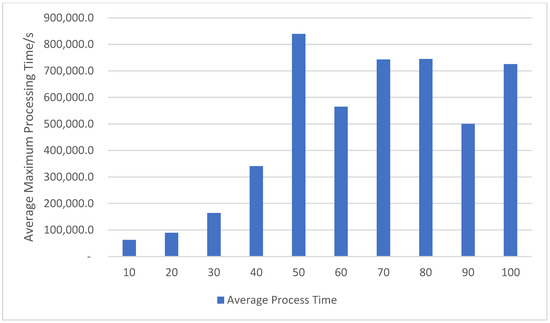

The number of orders is given as [10, 20, 30, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100], and the processing pieces for each order are [100, 500] pieces. To evaluate the impact of the boarding process, ten production tests were conducted for each of the product quantities described above under two production line configurations—with and without the boarding machine. Table 4 summarizes the total production time required for each order on the production line without the boarding process. In this configuration, fabric dimensions are constrained by the specific circular knitting machine used, resulting in a fixed total production time for each order. In contrast, when the boarding process is introduced, larger fabrics can be produced either by upscaling smaller fabrics through the boarding operation or directly by using larger circular knitting machines, leading to a non-fixed production workflow. The production scheduling of the line equipped with the boarding machine was optimized using GA, and ten tests were performed. Table 5 and Figure 4 present the total production times obtained from these optimized tests, along with the corresponding mean values, standard deviations.

Table 4.

Results (s) for Different Order Quantities without Boarding.

Table 5.

Results (s) for Different Order Quantities with Boarding.

Figure 4.

Finishing Time of Different Seamless Fabric Production Quantities with Boarding.

The results in the table show that for order quantities of 10 and 20, the optimization by GA—as a heuristic algorithm—exhibits randomness in the solutions. However, when the order quantities range from 30 to 100, the times for the 10 repeated tests under the same order size become exactly identical. After analysis, this phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the instance of the production line contains only two boarding machines: as the order volume increases, these machines cannot complete the boarding process in time for all fabrics. Consequently, the later orders end up waiting for boarding, causing the process bottleneck and resulting in the same completion time across repeated runs.

At a 95% confidence interval (i.e., significance level α = 0.05), significance tests were conducted on the datasets for order number 10 and 20, yielding:

Substituting , , , , and into the above equation yields:

With the = 10 + 10 − 2 = 18, the corresponding p-value is much less than 0.001. Therefore, at the significance level , the null hypothesis (that the two group means are equal) is rejected—there is a statistically significant difference between the two means.

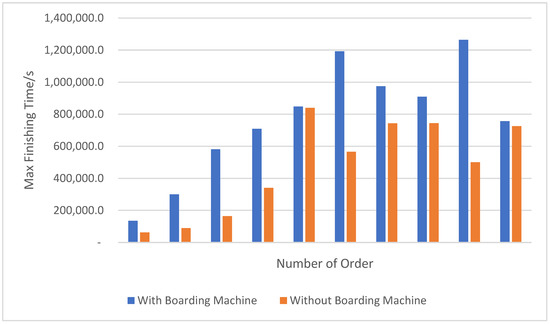

To validate the effectiveness of the boarding machine, a comparative analysis was conducted against scenarios without a boarding machine. The results, as shown in Table 6 and Figure 5, were obtained using randomly generated order information, with each scenario executed 10 times and the average values reported.

Table 6.

Comparison of Results with and without Boarding Machine Operations.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Results with Boarding Machine and without Boardings.

From Table 6 and Figure 5, it can be seen that introducing the boarding process leads to an overall production time improvement ranging from 0.98% to 71.70%. However, this improvement percentage is not linear. Upon further analysis, the underlying causes are as follows:

- As a heuristic algorithm, the Genetic Algorithm exhibits inherent randomness in its optimization results.

- The equipment configuration of the selected production line instance is uneven. For example, there is only one circular knitting machine capable of producing 12-inch fabric and one for 19-inch, while there are two boarding machines. This leads to scenarios in 12-inch production where the 12-inch knitting machine is operating at full capacity while the other remains idle; and in 19-inch production, the boarding machines must be fully utilized to shape the upstream fabric produced by smaller machines to 19-inch size, resulting in congestion at the boarding stage.

These factors cause the optimization results across different order volumes to become unpredictable, making it difficult to derive a general mathematical model that fits all optimized outcomes.

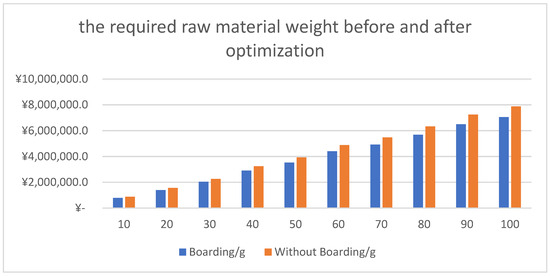

Since the amount of yarn used per unit area remains essentially constant during circular knitting, the material consumption of the original seamless fabric tube depends on its size: the larger the size, the more yarn is required. Table 7 shows the yarn weight needed to knit tubes of different sizes under the condition of a fixed tube length.

Table 7.

Yarn weight needed to knit tubes of different sizes.

During the setting process, the fabric width is expanded while its weight remains unchanged. Consequently, the set fabric achieves greater dimensional yield without additional material input, thereby improving raw material utilization efficiency. Table 8 and Figure 6 shows the required raw material weight before and after optimization according to the above scheduling results, as well as their differences and the corresponding percentage of material savings.

Table 8.

The required raw material weight before and after optimization.

Figure 6.

Required Raw Material Weight before and after Optimization.

The results obtained for scenarios with and without boarding machines indicate that the differences between the two cases remain consistently positive, the production time efficiency improved by 0.98% to 71.70%, whereas raw material savings ranged from 9.55% to 10.63%. although they do not exhibit a strictly linear trend.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

This paper analyzed the seamless fabric production process and integrated scheduling optimization algorithms, employing a Genetic Algorithm to optimize the production line. The case study demonstrates that, with the introduction of boarding machines, the seamless fabric production process can effectively reduce production time and significantly enhance production efficiency and raw material saving. However, the improvement in production efficiency is not strictly linear, and the enhancement in material utilization remains uncertain, in addition, this study focuses on the case analysis of a single seamless fabric production line. Although the results demonstrate optimization in both production efficiency and material consumption, the performance of method on other production lines has not been validated. Furthermore, the proposed algorithm primarily targets production efficiency. The observed raw material savings in the optimized production line are a by-product of efficiency optimization, rather than the result of a scheme specifically designed to minimize material consumption. To simultaneously optimize both production efficiency and raw material utilization, the algorithm must be further refined and validated through additional experiments. Future research will seek additional production line cases for comparative analyses and incorporate other optimization algorithms for benchmarking; in addition, future research will focus on further refining the mathematical models and optimization algorithms to improve material utilization, as well as incorporating additional performance indicators—such as energy consumption and hazardous waste emissions—into the model, and developing optimization algorithms that target these metrics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N. and Q.S.; methodology, Q.S.; software, Q.Y. and C.R.; validation, Q.S., Q.Y. and C.R.; formal analysis, Q.Y. and C.R.; investigation, Q.Y. and C.R.; resources, Q.S.; data curation, Q.S., Q.Y. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.S.; writing—review and editing, Q.S.; visualization, Q.S.; supervision, B.N.; project administration, Q.S.; funding acquisition, Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, the APC was funded by Unversity of Duisburg-Essen.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We confirm that we use GPT4 to polish the English writing of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gokarneshan, N. A Perspective on Seamless Woven Garments. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2265568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Baogao. China Seamless Apparel Market: Growth Analysis and Investment Opportunities, 2023–2030; Guanyan Research Institute: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W.-K.; Song, Y.; Suh, E.S. Garment production line optimization using production information based on real-time power monitoring data. Syst. Eng. 2024, 24, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorovna Morozova, T.; Alayi, R.; Grimaldo Guerrero, J.W.; Sharifpur, M.; Ebazadeh, Y. Investigation and Optimization of the Performance of Energy Systems in the Textile Industry by Using CHP Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, I.; Ali, H.; Asif, M.A. An evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective optimization of freshwater consumption in textile dyeing industry. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.A.; Kumar, R.; Pathak, G.; Roy, H. Application of goal programming in the textile apparelindustry to resolve production planning problems—A meta-goal programming technique using weights. Oper. Res. Decis. 2022, 32, 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pannu, S.; Ahirwar, M.; Jamdagni, R.; Behera, B.K. Role of heat setting and finishing treatment on mechanical properties and hand behavior of stretch fabric. J. Text. Eng. Fash. Technol. 2020, 6, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanie, M. An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780585030944. [Google Scholar]

- Lorente-Leyva, L.L.; Murillo-Valle, J.R.; Montero-Santos, Y.; Herrera-Granda, I.D.; Herrera-Granda, E.P.; Rosero-Montalvo, P.D.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H.; Blanco-Valencia, X.P. Optimization of the Master Production Scheduling in a Textile Industry Using Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Hybrid Artificial Intelligent Systems—HAIS 2019, León, Spain, 4–6 September 2019; Pérez García, H., Sánchez González, L., Castejón Limas, M., Quintián Pardo, H., Corchado Rodríguez, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11734. [Google Scholar]

- Obe, O.; Egwuche, O.S. Genetic algorithm approach for fabric pattern generation in textile industries. Anale Seria Inf. 2018, 16, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pétrowski, A.; Ben-Hamida, S. Evolutionary Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; p. 30. ISBN 978-1-119-13638-5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).