Abstract

Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) have emerged as key enablers of autonomous maritime operations, offering innovative solutions across multiple industries, including defense, oceanography, offshore energy, and logistics. This review examines the current state of operative USVs, analyzing their technological evolution, design characteristics, and applications. The study highlights trends in autonomy, propulsion, endurance, and communication technologies, providing insights based on market-ready platforms. While USVs present significant advantages in terms of efficiency and operational safety, challenges such as regulatory constraints, cybersecurity risks, and limitations in autonomous decision-making persist. This paper aims to update researchers, policymakers, and industry stakeholders on the technological advancements and emerging trends shaping the future of unmanned vehicles.

1. Introduction

Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) have emerged as a transformative technology in maritime operations, significantly impacting industries such as defense, oceanography, and commercial shipping [1]. The rapid advancements in autonomous systems, sensor technology, and communication networks have enabled USVs to perform a wide range of missions, from environmental monitoring to surveillance and logistics. The increasing adoption of these systems reflects a global shift toward automation and artificial intelligence (AI) [2] in maritime domains, aiming to enhance efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

The origins of USVs can be traced back to early remotely operated vessels used primarily for military applications. Over time, technological advancements in control systems, propulsion, and sensor integration have enabled these vehicles to become highly autonomous and versatile. This evolution has led to their adoption in various industries, such as scientific research [3] and oil and gas exploration. The growing interest in autonomous maritime technology is also driven by the need for cost-effective solutions [4] that minimize human risks and operational expenses in hazardous environments.

The technological advancements in USVs extend beyond just autonomy. Improvements in propulsion systems [5], energy storage [6], and navigation algorithms [7] have significantly enhanced their performance. Electric and hybrid propulsion systems, for example, have contributed to increased energy efficiency and reduced environmental impact. Meanwhile, advances in AI and machine learning have allowed USVs to process vast quantities of data in real time, enabling them to make intelligent decisions during missions [8]. The integration of robust communication technologies further ensures seamless coordination with remote operators and other autonomous systems.

Despite their many advantages, USVs face several challenges that hinder their widespread adoption [4]. Regulatory frameworks governing autonomous maritime operations vary significantly across different regions, creating legal and logistical barriers. Furthermore, AI-driven autonomy is still evolving, with limitations in decision-making under unpredictable environmental conditions [9]. The need for robust cybersecurity measures is also a pressing concern, as USVs rely on remote communication networks that could be vulnerable to cyberthreats [10]. Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring the safe and efficient operation of USVs in both commercial and defense applications.

Concerning related works, the work from Tanakitkorn [11] provides a review on the general development of USVs, encompassing research prototype, developmental trends, and potential applications. In the work from Patterson et al. [4], the authors present a synthesis of 15 years of USV-related literature. Their work evaluates drivers, applications, and operational applications of USVs in a qualitative and quantitative way, assessing the necessary innovations that will enable the diffusion of the USV technology. Lastly, the authors argue that the functionalities of USVs are complementary of those traditional methods for ocean monitoring, challenging the perspective that USVs are replacing crewed ships. Yang et al. [1] carried out a bibliometric analysis and overall review of the new technology and development of USVs, covering the literature from 2000 to 2023. Based on their analysis, the authors proposed six future research directions: (1) enhanced intelligence and autonomy, (2) highly integrated sensor systems and multi-modal task execution, (3) extended endurance and resilience, (4) satellite communication and inter-connectivity, (5) eco-friendly and sustainable practices, and (6) safety and defense. The review from Bai et al. [3] evaluated existing applications and models of unmanned vessels. The authors concluded that the current maritime regulations, designed for crewed ships, did not entirely meet the profile of unmanned vessels. Also, they noticed that while small USVs were used for data collection, large USVs were still in the development stage. Other very interesting review studies have focused in related aspects of USVs, such as Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC) [12], path planning [13,14], intelligent motion control [15], hull design [16], and Model-Free Adaptive Control (MFAC) [17].

Therefore, different from previous works, this paper provides a comprehensive review of operative USVs, examining their technological evolution, design characteristics, and operational applications. Considering the USVs’ capabilities, endurance, and intended use, this study highlights the key trends that have shaped the development of these systems. Through an analysis of existing platforms and market trends, this review aims to offer valuable insights into the current and future landscape of USVs.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. The next section (Section 2) presents a brief background of USV technology, covering its evolution, regulatory challenges, classification, key components, and applications. Section 3 discusses the operational trends and brings insights based on data from operative state-of-the-art USVs. Conclusions are given in Section 4.

2. Brief Background of USV Technology

This section aims to give a background of the USV technology, covering its evolution, regulatory challenges, size-based classification, its key technological components, and the various applications found in the market.

2.1. Evolution of USVs

The development of USVs has progressed significantly, evolving from early remote-controlled vessels to highly autonomous systems [12]. Initially adapted from manned vessels, USVs have advanced to purpose-built platforms with specialized capabilities [18]. Technological advancements, including artificial intelligence, advanced sensors, and improved communication systems, have enabled modern USVs to conduct complex missions with minimal human intervention [19]. These developments have expanded USV applications in environmental monitoring, marine production, territorial surveillance, and offshore operations [20]. Key demonstrations, such as the Wave Glider and Sea Hunter USV, have showcased long-endurance capabilities and naval applications. The integration of machine learning, situational awareness sensors, and telemetry tools has further enhanced USV autonomy and control [19].

As research and innovation continue, USVs are poised to play an increasingly significant role in marine operations, improving efficiency, safety, and sustainability [20]. Recent research highlights significant advancements in Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) technology, focusing on enhancing autonomy and multi-mission capabilities. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in adaptive control systems is improving USV decision-making and navigation [21]. Embodied intelligence is playing a crucial role in developing intelligent navigation, collision avoidance, and swarm behavior systems [22], where multiple USVs coordinate their activities [23]. Ongoing research aims to further improve USV autonomy by incorporating the International Regulations for Avoiding Collisions at Sea into obstacle avoidance protocols [9]. As AI-driven navigation continues to evolve, USVs are becoming more reliable, efficient, and versatile. However, challenges remain, including navigational uncertainties, energy constraints, and the need for standardized regulatory frameworks [22]. Future developments in USV technology are expected to revolutionize maritime operations and data collection efforts.

2.2. Regulatory Challenges

Concerning regulatory challenges faced by USVs, an Herculean effort has be made over the last years to develop international and national legal frameworks. However, most of the development of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASSs) has been carried out using a human-centric approach [24], assuming the presence of humans for navigation, monitoring, maintenance, and emergency handling, which poses gaps and uncertainties when, for instance, vessels without crew or remotely operated are considered. The work from Ahmed et al. [25] identified that a significant portion of these gaps related to core conventions like SOLAS (62%), COLREG (12%), STCW (6%), and ICLL (5%).

In addition to the human-centric approach issue, which poses direct challenges to crewless operations, there exist ambiguities of key terms like master and crew in the context of unmanned vessels, impacting compliance with various regulations and international legal instruments like UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). Another point regards the regulations specifically for autonomous operations, which creates uncertainty for stakeholders for design, testing, and operational standards. All these challenges and uncertainties impact negatively on the growth in investment and development in this field. Thus, to overcome these barriers, some solutions were proposed [25]: redefining roles and responsibilities, such as designating remote operators as equivalent to the “master” or “crew”; the IMO MASS code, which is a significant step towards establishing internationally accepted guidelines; and international collaboration for ensuring the safe and efficient cross-border operation and wide acceptance of MASSs.

Many authors have been studying regulatory and legal frameworks related to MASSs. The article from Komianos [26] gives an overview of the revolutionary potential regarding unmanned vessels. Through the exploration of regulatory challenges associated with international regulations and the implementation of USVs, the author discusses how existing international maritime laws and conventions need to adapt to accommodate the innovations brought by USV technologies. Van Hooydonk [27] and Chang et al. [28] analyzed the international legal status of different types of MASSs from the perspective of the law of the sea (UNCLOS), where the first work analyzed the relevance of existing laws, necessary amendments, and development of new rules, and the second one suggested responsive measures for how coastal states manage foreign USVs operating in their waters. The work from Ahmed et al. [25] focused on the regulatory and legal challenges posed by MASSs in short sea shipping. The gaps found in different international and national frameworks were classified by severity; then, the authors proposed recommendations to fill these gaps. Also, an important point is that in their analysis, the work from Ahmed et al. took into account the different levels of autonomy, creating a clear structure for policymakers.

Finally, on the subject of regulatory development through the globe, Europe seems to be at the forefront of actively addressing the regulatory challenges of autonomous vessels, particularly within its regional and national frameworks. On the other hand, while many nations recognize the need for international regulations, information regarding the advancements in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Australia are more limited, but the few existing ones suggest that these regions are actively examining the implications of maritime autonomous technology and considering their national and local regulations as basis for MASS-related regulations.

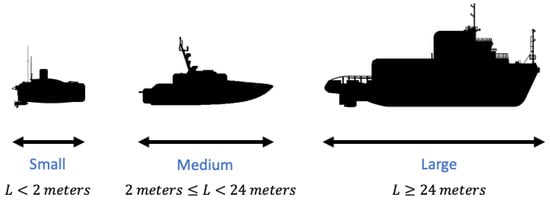

2.3. Size-Based Classification of USVs

In this work, USVs were categorized as small, medium, or large based on their size (Figure 1). Small USVs have a 2 m long upper limit, which was defined based on the observations during the preparation of this work. There is a huge number of unmanned surface vessels below this value, the majority being designed for nearshore monitoring, survey missions, and environmental assessments. They offer agility and ease of deployment, making them ideal for scientific data collection and security applications in confined waters.

Figure 1.

Size classification of USVs. L stands for length.

Medium-sized USVs are up to 24 m in length, which is a significant threshold mentioned in different regulations [29,30]. This value defines requirements for vessels under and above it, commonly called length of rule L. In general, these USVs offer extended endurance and enhanced payload capabilities, making them suitable for hydrographic surveys, offshore inspections, and security operations. These vessels are commonly equipped with advanced sensor suites, enabling precise data acquisition for industries such as oil and gas, fisheries, and environmental research.

Finally, above 24 m in length, we classify USVs as large-sized USVs. For the present work, the only USV we found to be operative and with available specifications was the Armada 78 (A78) from Ocean Infinity [31]. There are also other projects with limited available information, such as the Norwegian YARA Birkeland, an unmanned electric 80 m long commercial ship [32].

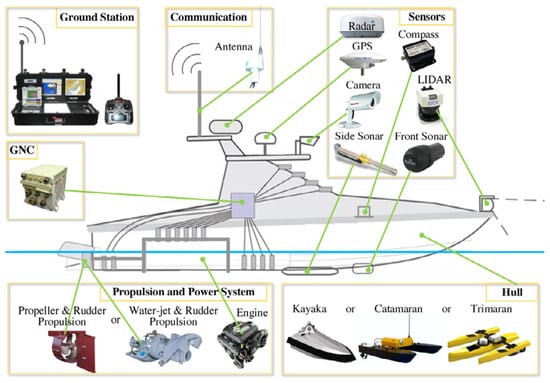

2.4. Key Technological Components

The effectiveness of USVs is largely determined by advancements in key technologies, such as hull design, propulsion systems, communication networks, and onboard sensors [12] (Figure 2):

- Hull design influences hydrodynamic efficiency, stability, and stealth capabilities [16], with materials ranging from lightweight composites [33] to reinforced aluminum [34]. Optimized hull shapes minimize drag and enhance fuel efficiency, allowing for improved endurance and speed.

- Propulsion systems vary from electric motors [35] for silent operations to hybrid and diesel engines for long-range missions [36]. Electric propulsion, powered by lithium-ion batteries or hydrogen fuel cells, is gaining popularity due to its low noise signature and reduced environmental impact.

- Communication technologies, including satellite links, 4G/5G networks, and radio frequency transmissions, enable real-time control and data transfer. These advancements ensure continuous connectivity between USVs and command centers [37].

- Sensor integration, comprising radar, LiDAR, cameras, and sonar, enhances situational awareness and autonomous navigation. Multi-sensor fusion enables USVs to create a comprehensive understanding of their surroundings, improving collision avoidance and target tracking [38,39]. The convergence of these technologies continues to push the boundaries of what USVs can achieve in various maritime sectors.

Figure 2.

Key technological components from a typical USV [12].

2.5. Applications of USVs

USVs have emerged as versatile tools with applications across various industries. In defense and security, USVs contribute to surveillance and safeguarding offshore systems [20]. Environmental monitoring benefits from USVs’ ability to collect real-time data on water quality and marine biodiversity, offering cost-effective alternatives to traditional research vessels [40]. In commercial offshore services, USVs enhance efficiency through inspections of subsea assets and are being explored for autonomous shipping [41]. USVs also play a crucial role in search and rescue missions, though this application was not explicitly mentioned in the provided abstracts. Technological advancements have improved USVs’ autonomy, sensor integration, and communication systems, expanding their capabilities and reliability [20]. The integration of USVs into existing maritime operations offers a cost-effective solution with minimal risk to personnel [11].

Thus, based on the main applications found in the market, we can broadly categorize the following USVs’ uses:

- Environmental monitoring;

- Surveillance and security;

- Scientific research;

- Asset inspection;

- Military and defense;

- Communication and navigation;

- Survey and mapping;

- Disaster response;

- Logistics and support;

- Energy and offshore.

3. Trends in Operational USVs

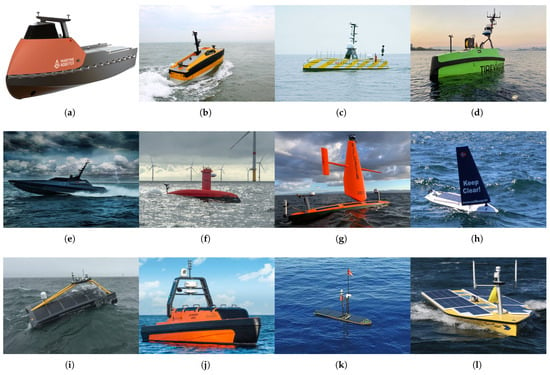

The rapid advancement of USVs has led to a diverse range of platforms tailored for various maritime applications, from scientific research to defense operations. This section aims to discuss the data of the numerous USV models that have been operating over the last decades. By analyzing these data, clear distinctions emerge between small, agile USVs designed for coastal operations and long-endurance platforms built for exploration and data collection.

The data comprise a total of 47 Unmanned Surface Vehicles models (Figure 3), which are available on the market through different ways, such as rental or sale. While some manufacturers make a lot of specifications available concerning their USVs, others make this task hard by providing little information. Concerning the control modes, all USVs are able to be remotely controlled. However, concerning the autonomy levels, they are not explicit, but most of them are able to carry out conventional waypoint navigation, station keeping, and collision avoidance. These control modes are typically used for tasks such as surveying, inspection, patrolling, and autonomous transport. Other important characteristics such as endurance and communication technologies are discussed through the rest of this section.

Figure 3.

Examples of USVs mapped in the present study in the format USVname (Manufacturer): (a) Mariner X (Maritime Robotics). (b) Armada 8 (Ocean Infinity). (c) SEAKIT X (SEAKIT). (d) Tupan (Tidewise). (e) Shadow Fox (L3Harris). (f) DriX H9 (Exail). (g) Voyager (Saildrone). (h) Sailbuoy (Offshore Sensing). (i) XO450 (XOcean). (j) Sounder (Kongsberg). (k) Wave Glider (Liquid Robotics). (l) SP48 (SeaTrac).

Due to limited publicly available information, the topics presented in this section do not strictly follow the classification presented in the Key Technological Components section (Section 2.4). Also, we tried our best to fill in the information about each USV model as completely as possible, but sometimes, the manufacturers gave only broad information; for instance, instead of giving the propulsion as “2 × Cummins QSB, 6.7 inboard engines (550 HP each) with Hamilton 292 waterjets”, it was given as “2 × Electric motors”.

A full summary detailing USVs’ manufacturers, technical specifications, propulsion systems, endurance, payload capacities, intended applications, and so on, can be found in Appendix A. The full table can be found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSXQlvk4DY7Sv4EwOBVMcVRWSU-A3E0zfxMH6oQeab5b3mDDjEmc6q2I9d67xpPIZZoUXVczw7bKtYw/pubhtml?gid=0&single=true (accessed on 18 April 2025).

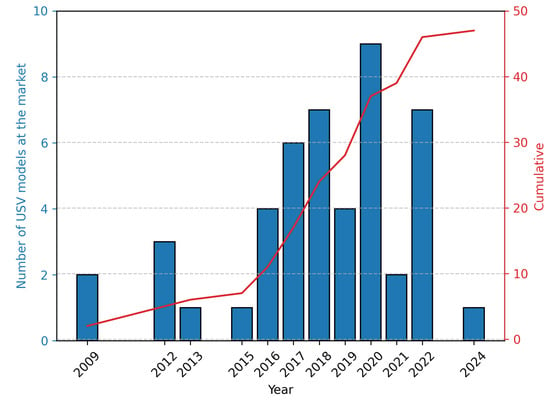

3.1. Models Introduced to the Market

The evolution of USVs over the years shows a steady increase in the number of models introduced to the market (Figure 4), with significant growth occurring from 2015 onward. Early adoption was relatively slow, with only a few models appearing before 2015. However, from 2016 to 2020, there was a surge in the number of new USV models, peaking around 2019 and 2020, likely driven by advancements in autonomous navigation, maritime security needs, and the growing interest in oceanographic and offshore applications. Despite some fluctuations in annual releases after 2020, the cumulative number of USVs has consistently increased, surpassing 40 models by 2024. This trend highlights the sustained development and adoption of USVs in various industries, reflecting the increasing reliance on unmanned maritime systems.

Figure 4.

Annual and cumulative growth of Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) models in the market.

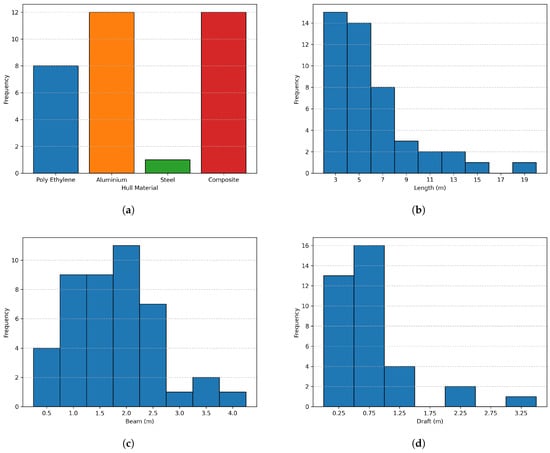

3.2. Hull Materials and Main Dimensions

Concerning the hull materials among USVs, their distribution highlights a clear preference for aluminum and composite materials, with polyethylene also being widely used (Figure 5a). Aluminum is a popular choice due to its lightweight properties, corrosion resistance, and ease of fabrication, making it ideal for both commercial and defense applications. Composite materials, such as fiberglass and carbon fiber, offer high strength-to-weight ratios, reduced maintenance requirements, and excellent durability, which explains their significant presence. Polyethylene, although not as dominant, is favored for smaller USVs due to its cost-effectiveness and impact resistance. Steel, on the other hand, is rarely used in USVs, likely because of its higher weight and maintenance demands due to its susceptibility to corrosion. This distribution reflects the industry’s focus on lightweight, durable, and low-maintenance materials that enhance operational performance.

Figure 5.

(a) Distribution of hull materials used in USVs. (b) Histogram of USV lengths. (c) Distribution of USV beams. (d) Histogram of USV draft values. The distributions of length, beam, and draft do not include the Armada 78 USV.

Just as material selection reflects operational priorities, USV length also plays a crucial role in defining mission scope and capabilities. The length distribution of USVs reveals that most models are relatively small, concentrated between 3 and 7 m, with significantly fewer models exceeding 10 m (Figure 5b). This trend suggests that the majority of USVs are designed for nearshore and coastal applications, where compact and agile platforms are preferred for tasks such as environmental monitoring, maritime surveillance, and hydrographic surveys. The reduced presence of longer USVs can be attributed to the increased complexity, cost, and logistical challenges associated with deploying and maintaining larger vessels. However, a few models extend beyond 15 m, likely designed for specialized missions such as long-range offshore inspections and military applications. The overall trend indicates that the industry prioritizes compact designs that balance operational versatility, cost-efficiency, and ease of deployment, catering to a broad range of commercial and defense applications.

Alongside length, beam dimensions further shape USVs’ hydrodynamics, stability, and transportability. The distribution of USV beams suggests that most models have a beam between 1 and 2.5 m, with a peak around 2 m (Figure 5c). This relatively narrow beam range indicates a preference for streamlined designs that enhance hydrodynamic efficiency, maneuverability, and transportability. USVs with beams around 2 m may be looking for a balance between stability and performance, which allows them to operate effectively in various conditions without excessive drag. Wider beams, though less common, are likely found in larger or specialized USVs that require additional transverse stability for carrying payloads, such as scientific instruments, communication equipment, or modular sensor systems. On the other hand, very narrow beams, below 1 meter, may be associated with lightweight, high-speed models designed for rapid deployment or reconnaissance. The observed beam distribution reflects design considerations that prioritize efficiency, ease of deployment, and adaptability across diverse maritime environments.

Finally, draft distribution provides insight into the intended operational environments of USVs, complementing the trends observed in other design features. The draft distribution of USVs indicates that most models have a shallow draft, typically below 1.25 m, with a significant concentration around 0.75 m (Figure 5d). This trend suggests that USVs are primarily designed for operations in shallow waters, nearshore environments, and inland waterways, where limited draft enhances accessibility and maneuverability. Shallow-draft USVs are well suited for applications such as environmental monitoring, port security, and bathymetry surveys, where deeper hulls could pose operational constraints. The presence of a few models with drafts exceeding 2 m likely corresponds to larger, ocean-going USVs built for endurance and stability in deeper waters. However, these remain a minority, reflecting the general industry focus on compact, shallow-draft platforms that maximize operational flexibility. The predominance of shallow drafts highlights the increasing demand for versatile autonomous systems capable of navigating diverse and constrained maritime environments.

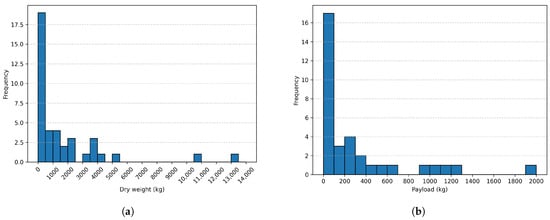

3.3. Dry Weight and Payloads

The dry weight distribution of USVs exhibits a heavily right-skewed pattern, with the majority of vehicles concentrated in the lower weight range (Figure 6a). Most USVs fall below 1500 kg, with frequency gradually decreasing as weight increases. This trend suggests that lightweight USVs dominate the field, likely due to operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and ease of deployment. However, a small number of vehicles reach significantly higher weights, extending beyond 10,000 kg, potentially representing specialized or industrial-grade USVs designed for heavy-duty applications such as offshore operations or military use. The presence of these outliers underscores the diversity in USV applications, where both compact and large-scale systems coexist to meet varying operational demands.

Figure 6.

Distribution of (a) dry weight (kg) and (b) payload capacity (kg) across the USVs. These distributions do not include the Armada 78 USV data.

Concerning the payload distribution, it follows a similar right-skewed pattern, with the majority of USVs capable of carrying relatively low payloads, often below 300 kg (Figure 6b). This pattern aligns with the dry-weight distribution, suggesting that most USVs are designed for lightweight applications such as environmental monitoring, small-scale survey missions, and autonomous navigation research. However, a minority of USVs support payloads exceeding 1000 kg, indicating a specialized subset engineered for transporting heavier equipment, cargo, or complex sensor arrays. The correlation between dry weight and payload capacity is evident, reinforcing the idea that larger USVs tend to accommodate greater payloads. These distributions collectively highlight the balance between size, weight, and functionality in USV design, emphasizing the trade-offs between agility and carrying capacity in different operational contexts.

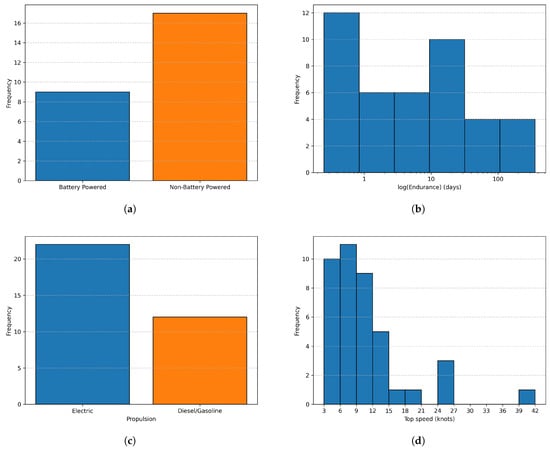

3.4. Power Sources, Endurance, Propulsion, and Top Speeds

The distribution of power sources in USVs reveals a significant reliance on non-battery-powered systems, although battery-powered models still constitute a notable portion (Figure 7a). This contrast likely reflects operational requirements, as battery-powered USVs are well suited for shorter missions and environmentally sensitive areas due to their quiet operation and low emissions. Non-battery-powered USVs, which include diesel, gasoline, and hybrid systems, are preferred for longer endurance and higher power demands. The dominance of non-battery propulsion suggests that energy storage limitations in battery technology still pose a constraint for extended or high-power applications. However, the presence of battery-powered USVs highlights the industry’s growing interest in electrification, particularly for compact, autonomous systems operating in nearshore and controlled environments. This trend aligns with propulsion choices, which is discussed in the following.

Figure 7.

Distribution of key operational characteristics of USVs. (a) Comparison of battery-powered and non-battery-powered USVs. (b) Distribution of endurance in days on a logarithmic scale. (c) Breakdown of propulsion types, distinguishing electric from diesel/gasoline. (d) Distribution of top speeds in knots.

The endurance of USVs spans a wide range; thus, we used a logarithmic scale on the endurance axis (Figure 7b). This indicates that while many USVs are designed for missions lasting only hours (first peak), a subset is optimized for extended endurance around one month (second peak). A noticeable zone regards the wind- and/or wave-propelled USVs, which can easily achieve 12 months of endurance. The lower-endurance USVs are likely employed for tasks such as coastal monitoring, port security, and hydrographic surveys, where frequent recharging or refueling is feasible. In contrast, the long-endurance models, often non-battery-powered, are used in persistent oceanographic research, military reconnaissance, and offshore energy applications. This endurance variation reflects the balance between energy capacity, propulsion efficiency, and mission-specific requirements.

The dominance of electric propulsion in USVs highlights a strong industry preference for efficient and low-maintenance systems, with diesel and gasoline propulsion making up a smaller portion of the fleet (Figure 7c). Electric propulsion aligns with the increasing adoption of battery-powered systems seen earlier, particularly in compact USVs designed for shorter missions. These systems offer reduced operational costs, lower noise signatures, and fewer mechanical complexities. However, diesel and gasoline engines remain relevant, especially for longer-endurance and high-speed applications requiring sustained power. The reduced share of internal combustion engines suggests a gradual transition toward more sustainable and technologically advanced propulsion methods. This balance between efficiency and performance influences another crucial factor in USV design—their top speed.

The speed distribution of USVs is highly skewed toward lower speeds, with most models operating between 3 and 12 knots, reflecting a design preference for efficiency and endurance (Figure 7d). A few models exceed 15 knots, indicating specialized applications such as rapid response or military operations. The clustering around lower speeds suggests that most USVs prioritize energy efficiency over higher speeds, particularly for missions requiring extended endurance. This speed distribution further reinforces the industry’s focus on balancing endurance, power efficiency, and operational reliability across various mission profiles.

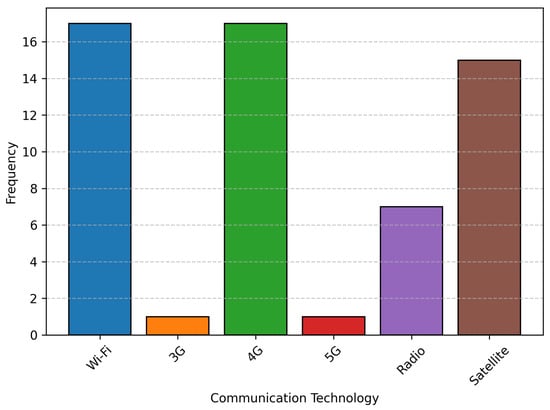

3.5. Communication Technologies

The communication technologies used in USVs shows a clear preference for certain widely available and reliable communication methods (Figure 8). Wi-Fi, 4G LTE, and satellite communication stand out as the most frequently utilized technologies, emphasizing the importance of stable and long-range connectivity for USV operations. Wi-Fi, being widely accessible, is likely used for short-range applications, whereas 4G provides broader coverage where terrestrial networks are available. Also, the prominence of satellite communication suggests that many USVs operate in remote or offshore environments where terrestrial networks are insufficient. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite technologies such as Starlink and Iridium are also used in some USVs. Traditional radio-based communication methods such as VHF and UHF also have significant usage, particularly for maritime applications where established radio networks provide reliable and regulated communication. Emerging technologies like 5G, though less frequent, hint at a gradual shift towards high-bandwidth, low-latency solutions that could enhance real-time data transmission in future USV designs.

Figure 8.

Bar charts illustrating the frequency of different communication technologies used in USVs.

To give an overview of the communications technologies implemented in operative USVs, Table 1 lists the solutions given by manufacturers. Also, a high-level category of radio, satellite, or cellular is presented together with the type of technology and approximated ranges that are achievable by each one.

Table 1.

Solutions given by USVs’ Manufacturers.

3.6. Sensors and Situation Awareness Technologies

Sensors are crucial components of USVs, and for the vehicles used in research papers, the list of sensors used is easily found [76,77,78], with model, main characteristics, and so on. However, for commercial USVs, there is limited publicly available information in this regard. Most sensors listed are related to the situation awareness capabilities of each USV model, which comprise radar, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), thermal cameras, optical cameras (RGB), and AIS (Automatic Identification System) and are discussed in the next paragraph. But, certainly, most USVs are equipped with sensors such as GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System), IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit), Radio Frequency (RF) communication, and voltage, current, and temperature sensors for battery management.

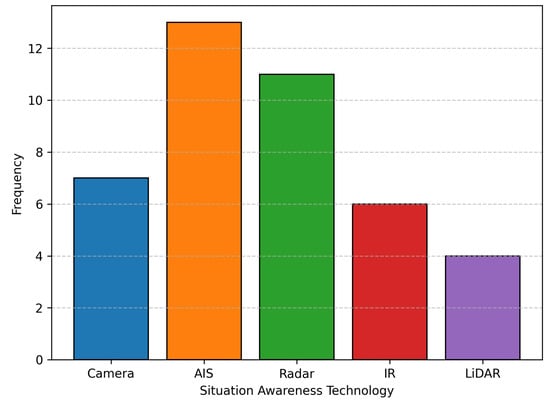

The distribution of situation awareness technologies reveals that Automatic Identification System (AIS) and radar are the most commonly used sensing systems, reinforcing the maritime industry’s reliance on these technologies for navigation and collision avoidance (Figure 9). AIS is widely adopted due to its ability to track nearby vessels and integrate with existing maritime traffic management systems. Radar, similarly, provides real-time environmental awareness, making it indispensable for autonomous operations, especially in adverse weather conditions. Camera-based systems also appear frequently, likely used for visual monitoring and object detection in combination with other sensors. Infrared (IR) and LiDAR, though less prevalent, play crucial roles in specific applications, such as night-time operations, obstacle detection, and high-precision mapping. The overall distribution of these technologies highlights a balance between traditional and advanced sensing solutions, with newer technologies like LiDAR gradually supplementing well-established methods. This trend suggests a continuous evolution in USV situational awareness capabilities, aiming for enhanced autonomy and safety in various operational environments.

Figure 9.

Bar charts illustrating the frequency of different situation awareness technologies used in USVs.

3.7. Sea States

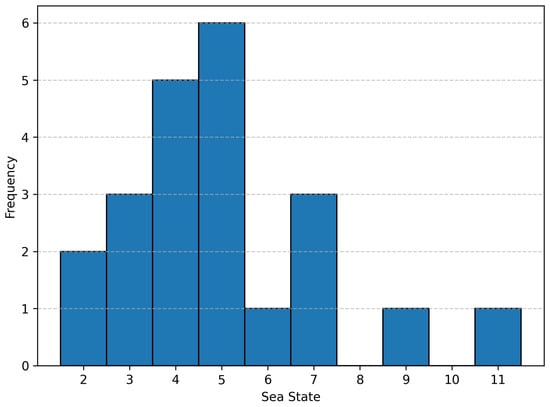

The maximum sea states tolerated by the USVs reveal that these vessels predominantly tolerate slight–moderate wave conditions, with sea states within 4 and 5 being the most frequently encountered (Figure 10). The highest occurrence is observed at sea state 5, which corresponds to moderate conditions, indicating that many USVs are designed to function reliably in environments with wave heights up to 3 m. This aligns with typical maritime operational requirements, where stability and control must be maintained even under challenging conditions. The noticeable decrease in frequency for sea states above 6 suggests that most USVs are not commonly deployed in rough or extreme sea conditions, likely due to limitations in their hull design, propulsion capabilities, and onboard stability control. However, the presence of data points at higher sea states (9 and beyond) indicates that some specialized USVs may be capable of enduring extreme conditions, possibly for military, research, or offshore applications.

Figure 10.

Histogram representing the frequency distribution of the maximum sea states tolerated by the USVs.

3.8. Key Findings

Although substantial progress has been made in control theory and artificial intelligence for USV control [2,9,79,80,81], the analysis of the 47 operative USV models suggest that the majority of market-ready USVs have only conventional control modes like waypoint navigation, station keeping, and collision avoidance, with remote control being a standard feature. Thus, differently from the significant strides in shore and aviation industries, these findings highlight the barrier that exists between the state-of-the-art research and the deployment of these new developments in the maritime sector. Despite that, USVs like the Shadow Fox are already able to operate in a swarm configuration, for instance.

In terms of endurance, there is a notable variation, with some models designed for short-duration missions of a few hours (e.g., 8 h: C-Cat3, ME120, Uni-Pact, HydroCat-550, and EchoBoat-240) while others can operate autonomously for up to 12 months (e.g., Explorer, Sailbuoy, and Wave Glider). These differences arise mainly due to the source of energy used to propel the USVs. The models with short endurance ( days) are commonly equipped with battery-powered electric motors. The mid-endurance ( days) USVs are mostly equipped with diesel or gasoline engines, as for instance, the DriX H-8 equipped with a 37.5 HP diesel engine and 10 days of endurance time, and the Mariner X equipped with a Hamilton Jet HJX29 and Yanmar 4LV230 with redundant twin electric pods and a bow thruster [82] for slow speed navigation and an endurance time of 25 days. For long endurance time ( days), only the solar-, wind-, or wave-propelled USVs are able to achieve months of activity, such as the solar-powered SP-48 equipped with a 1000 W brushless motor and months of endurance, the wind-propelled Explorer with over 12 months of endurance, and the wave-propelled Wave Glider with 12 months of endurance. All these variations emerge from the types of applications that require different levels of power. While short-endurance USVs are sufficient for surveys on lakes and rivers, defense and offshore industries tend to demand more endurance time.

Concerning the propulsion systems arrangements, the distribution indicates a growing preference for electric motors, aligning with industry trends favoring efficiency and sustainability, though diesel and hybrid alternatives remain relevant for high-power applications. As previously mentioned, the choice of arrangement strongly depends on the required endurance time. However, the last advancements in battery and electric motor technologies have enabled a shift toward more sustainable systems, which allows USVs to carry out silent and emission-free operations. The solar-, wind-, or wave-propulsion systems enabling months of endurance represent valuable technology for persistent oceanographic research and climate monitoring, as it eliminates the need for frequent refueling or battery replacement.

The integration of satellite, 4G LTE, and emerging 5G solutions by USV companies highlight the increasing reliance on high-bandwidth, low-latency connectivity for real-time data transmission. Also, the communication range plays a crucial role in USV operations since it influences the distance between vessels and their remote operators. The results suggest that within each manufacturer, these technologies are somehow standardized, varying in general only between the models from different companies. For instance, the models AutoNaut 3.5 and 5.0 from AutoNaut are both equipped with satellite communication, but their setup differs from, for example, the Mariner and Mariner X from Maritime Robotics, which use LTE (4G) communication. Furthermore, as for all other features of the USVs, the communication also depends on the purpose of the vessel. Thus, we find short-endurance vessels like the HydroCat-550 with (short-range) Wi-Fi communication and long-endurance vessels like the Voyager with (long-range) Starlink and Iridium technologies.

3.9. Future Trajectory of USVs

Based on the trends in market-ready USVs discussed in the present section (Section 3), this subsection highlights key aspects of the technology’s future trajectory. Several interesting points emerge:

- Considering the autonomy found in most (market-ready) USVs and the recent strides in artificial intelligence, a significant gap remains between the state-of-the-art research and most operative USVs, which still rely on conventional control modes.

- Another important gap lies in the hardware and software architectures of these USVs. Due to limited publicly available information, it is challenging to assess the advantages and disadvantages of different USV models.

- Despite various developments of collision avoidance algorithms that comply with the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), most manufacturers do not disclose details regarding their implementation.

- Autonomous navigation is an important feature in most USVs, yet it is generally limited to basic modes, such as waypoint navigation. However, more advanced capabilities like autonomous berthing are rarely mentioned by manufacturers, reinforcing the gap highlighted in point 1.

- Another critical aspect is the extrapolation of features across different USV scales. Thus, some topics arise, for instance, (1) the control used in small vessels, (2) legal requirements, and (3) cybersecurity risks. With those, some questions also arise due to differences in equipment and operational contexts: “how would these features be translated from small to large USVs? Will there be any kind of equivalence between them?”.

Drawing a parallel with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology as a reference, we can anticipate that the future of USVs will follow a similar trajectory. It is plausible that in the future, any person will be able to buy small unmanned vessels, and possibly some companies will offer unmanned vessels for specialized tasks such as fishing, small cargo transportation, and rescue operations. Larger USV projects like the mentioned Armada 78 (A78) and the YARA Birkeland are already increasing in number, and their presence in industries such as oil and gas, defense, logistics, and research appears inevitable.

Furthermore, the growth in artificial intelligence will certainly play a crucial role in the majority of the market due to its automation possibilities and efficiency. Difficult tasks, such as environment perception, operations of multiple USVs, and decision-making will be overcome and widely deployed. Also, at some point, the incorporation of international, national, and local regulations will be more straightforward, i.e., researchers and manufacturers will already be aware of what they must comply with, facilitating the spread of the technology. In addition, the recent advancements in low-orbit satellite technologies (e.g., Starlink, Kuiper) have enabled low latency, which is important to enhance real-time data transmission and control, and have been rapidly implemented in USVs. Lastly, all the growing emphasis on a sustainable future is and will continue to impact the industry to develop eco-friendly and sustainable practices in USV development. This is an enormous advantage of the USVs, which enables emissions reduction, the use of renewable energy sources, and consequently mitigates marine pollution.

4. Conclusions

The study underscores the rapid evolution of Unmanned Surface Vehicles, driven by advancements in autonomy, energy efficiency, and sensor integration. USVs have transitioned from niche applications to widespread adoption across commercial, scientific, and defense sectors. The analysis of operative models highlights a strong emphasis on endurance, with many platforms optimized for long-duration missions. Propulsion and communication technologies continue to evolve, supporting the increasing demand for reliable, real-time remote operations. However, challenges remain in ensuring seamless integration of USVs into existing maritime infrastructure, particularly in regulatory compliance and cybersecurity.

The findings also reveal that situational awareness technologies such as AIS, radar, and LiDAR are becoming standard components, enabling improved navigation and collision avoidance. The growing use of AI and machine learning in decision-making processes represents a promising step toward full autonomy. However, operational constraints, including adverse weather conditions and unpredictable maritime environments, necessitate continued innovation in hull design, energy storage, and control algorithms. The industry is gradually shifting toward greener propulsion solutions, with electric and hybrid systems reducing environmental impact while enhancing operational efficiency.

Future research should focus on overcoming the primary barriers to widespread USV adoption, particularly in standardizing regulatory frameworks and addressing cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Additionally, the continued development of robust AI-driven autonomy will be critical in enabling fully autonomous maritime operations. By addressing these challenges, USVs can achieve their full potential as reliable and cost-effective assets in modern maritime operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.d.A., J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; methodology, E.M.d.A., J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; formal analysis, E.M.d.A., J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; investigation, E.M.d.A.; data curation, E.M.d.A., J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.d.A.; writing—review and editing, E.M.d.A., J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; visualization, E.M.d.A.; supervision, J.S.S.J. and A.C.F.; project administration, J.S.S.J. and A.C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Programa de Recursos Humanos da Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis (PRH18-ANP) for their support, supported with resources from investment by oil companies qualified in the P, D&I Clause of ANP Resolution no. 50/2015. This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) through the “Jovem Cientsta do Nosso Estado”.

Data Availability Statement

The full table can be found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSXQlvk4DY7Sv4EwOBVMcVRWSU-A3E0zfxMH6oQeab5b3mDDjEmc6q2I9d67xpPIZZoUXVczw7bKtYw/pubhtml?gid=0&single=true (accessed on 18 April 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly and Writefull for the purposes of improve language and readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vessel |

| ROV | Remotely Operated Vehicle |

| UUV | Unmanned Underwater Vehicle |

| UXO | Unexploded Ordnance |

| CPT | Cone Penetration Testing |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| IUU | Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated |

| SOLAS | Safety of Life at Sea |

| USBL | Ultra-Short Baseline |

| PAM | Passive Acoustic Monitoring |

| MDA | Maritime Domain Awareness |

| ISR | Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| GRP | Glass-Reinforced Plastic |

| LLDPE | Linear Low-Density polyethylene |

| SS | Sea state |

Appendix A. Summary Tables

Table A1.

USVs’ manufacturers, release year, and applications.

Table A1.

USVs’ manufacturers, release year, and applications.

| USV | Manufacturer | Release Year | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otter [51] | Maritime Robotics | 2016 | Data acquisition; environmental monitoring; surveillance. |

| Mariner [83] | Maritime Robotics | 2009 | Ocean mapping and exploration; maritime surveillance and security; offshore support. |

| Mariner X [82] | Maritime Robotics | 2022 | Offshore monitoring and surveying; support vessel; surveillance. |

| Armada 8 (A8) [55] | Ocean Infinity | 2017 | Surveying; environmental research; seismic support; security. |

| Armada 78 (A78) [31] | Ocean Infinity | 2022 | Geophysical survey; geotechnical sampling; inspection; maintenance; repair services; support operations of ROVs, seabed drills and CPT systems. |

| SEA-KIT X [60] | SEA-KIT | 2017 | Deep-water bathymetry; offshore and subsea asset inspection; hydrographic survey. |

| Tupan [52] | Tidewise | 2020 | Marine site characterization; asset inspection; logistics; smart data; defense; surveillance. |

| Shadow Fox [65] | L3Harris | 2018 | MDA; ISR; anti-submarine warfare; area protection; force protection; surface warfare; communications relay; combat search and rescue; chokepoint monitoring; amphibious precursor and support operations; UAV forward operations; insertion operations support; maritime mine countermeasures force protection; swarm attack protection; battle damage assessment. |

| C-Cat 3 [67] | L3Harris | 2017 | Hydrographic survey; above-water mapping; UUV location and tracking; acoustic communication. |

| C-Worker 4 [84] | L3Harris | 2015 | Hydrographic survey; port and harbor surveillance; environmental monitoring. |

| C-Worker 5 [85] | L3Harris | 2016 | Hydrographic survey; port and harbor surveillance; environmental monitoring. |

| C-Worker 7 [86] | L3Harris | 2016 | Inspection and positioning applications; ROV deployment and recovery; multibeam survey; subsea positioning. |

| DriX H-8 [63] | Exail | 2017 | Advanced scientific and hydrographic surveys; geophysical and UXO surveys; subsea infrastructures’ inspection; surveys with multiple robots. |

| DriX H-9 [63] | Exail | 2022 | Advanced scientific and hydrographic surveys; geophysical and UXO surveys; subsea infrastructures’ inspection; surveys with multiple robots. |

| DriX O-16 [63] | Exail | 2024 | Advanced scientific and hydrographic surveys; geophysical and UXO surveys; subsea infrastructures’ inspection; surveys with multiple robots. |

| Inspector 125 [87] | Exail | 2019 | Coastal and harbor protection; mine countermeasures; rapid environment assessment. |

| Surveyor [58] | Saildrone | 2021 | IUU fishing; pattern-of-life monitoring; law enforcement and maritime safety; SOLAS missions; countersmuggling; border patrol; harbor security; guard vessel roles; sanction monitoring; range clearing; acoustic/SIGINT baselining; ecosystem monitoring; ocean mapping; seafloor classification; nautical chart validation; arctic and remote area exploration. |

| Voyager [58] | Saildrone | 2022 | High-resolution feature mapping; seafloor classification; nautical chart validation; arctic and remote area exploration; IUU fishing; pattern-of-life monitoring; law enforcement and maritime safety; countersmuggling; border patrol; harbor security; guard vessel roles; sanction monitoring; range clearing; acoustic/SIGINT baselining; ecosystem monitoring. |

| Explorer [58] | Saildrone | 2016 | Metocean data; ecosystem monitoring; fisheries data carbon monitoring; satellite calibration and validation. |

| Sailbuoy [47] | Offshore Sensing | 2012 | Collecting environmental data; measuring meteorological parameters; advanced data communication. |

| XO-450 [88] | XOcean | 2018 | Bathymetric survey; data harvesting; metocean data; fisheries; environmental monitoring. |

| Sounder [70] | Kongsberg | 2019 | USBL positioning; multibeam echo sounder; scientific and research; fishery. |

| Wave Glider [71] | Liquid Robotics | 2009 | Anti-submarine warfare; communications gateway; anti-surface warfare; ISR; meteorological and oceanography; tsunami and seismic monitoring; fish and marine mammal monitoring; hydrocarbon monitoring; metocean. |

| SP-48 [89] | SeaTrac | 2020 | Hydrography; communications gateway; data harvesting; environmental monitoring; mobile subsea positioning; MDA; metocean and oceanographic data collection. |

| L25 [90] | OceanAlpha | 2022 | Underwater inspection; hydrography survey; oceanography survey. |

| ME120 [91] | OceanAlpha | 2018 | Hydrographic survey; underwater inspection in lakes, rivers, harbors, construction sites, nearshore. |

| M40P [92] | OceanAlpha | 2020 | Hydrographic survey; site and route survey; construction inspection; seabed exploration. |

| M80 [93] | OceanAlpha | 2017 | Bathymetric survey; hazard location; hydrographic mapping; oceanographic measurements; pipeline survey; security patrol; underwater searches; water quality monitoring. |

| M75 [94] | OceanAlpha | 2018 | Patrol and guard; tracking and warning; underwater object detect. |

| Uni-Pact [95] | Unique Group | 2020 | Hydrographic survey; coastal and harbor monitoring; habitat mapping; seabed mapping and classification; data harvesting; survey of reservoirs. |

| Uni-Max [96] | Unique Group | 2019 | Search and recovery; hydrographic survey; inspection survey; oceanography and monitoring. |

| HydroCat-550 [97] | Seafloor Systems | 2020 | Inspection; survey of lakes, harbors, large rivers; water quality research. |

| EchoBoat-240 [98] | Seafloor Systems | 2020 | Inspection; survey of mines, sewage treatment plants, lakes, harbors, rivers. |

| AutoNaut 3.5 [99] | AutoNaut | 2012 | Data collection; research; monitoring in challenging marine environments; survey; surveillance; anti-submarine warfare; PAM; ocean science; metocean. |

| AutoNaut 5.0 [99] | AutoNaut | 2012 | Data collection; research; monitoring in challenging marine environments; survey; surveillance; anti-submarine warfare; PAM; ocean science; metocean. |

| Lightfish [100] | Seasats | 2020 | Bathymetric surveying; water sampling; perimeter security; wildlife monitoring; MDA; ISR; UUV/UAV teaming. |

| Mero [101] | USSV | 2022 | Single- and multi-beam bathymetry; physical water collection; oil leak detection; visual inspection of assets; cargo transportation; surveillance. |

| C-400 [102] | USSV | 2017 | Collection of meteorological, oceanographic or river surveys; study of aquatic life. |

| WAM-V 8 [73] | Ocean Power Technologies | 2019 | Marine survey; oceanography; marine protected area monitoring and enforcement; port surveillance and security; UAV and UUV deployment; nodal communications; oil and gas operations |

| WAM-V 16 [73] | Ocean Power Technologies | 2013 | Benthic operations survey; oceanography; marine protected area monitoring and enforcement; port surveillance and security; UAV and UUV deployment; nodal communications; oil and gas operations. |

| WAM-V 22 [73] | Ocean Power Technologies | 2021 | Benthic operations survey; oceanography; marine protected area monitoring and enforcement; port surveillance and security; UAV and UUV deployment; nodal communications; oil and gas operations. |

| SR Utility 2.5 [44] | SeaRobotics | 2018 | Disaster response; bathymetric research; water quality studies; stream gauging; winch deployment; habitat mapping; infrastructure survey. |

| SR Utility 3.0 [44] | SeaRobotics | 2020 | Disaster response; bathymetric research; water quality studies; stream gauging; winch deployment; habitat mapping; infrastructure survey. |

| SR Utility 3.6 [44] | SeaRobotics | 2018 | Disaster response; bathymetric research; water quality studies; stream gauging; winch deployment; habitat mapping; infrastructure survey. |

| SR Endurance 7.0 [44] | SeaRobotics | 2018 | Disaster response; bathymetric research; water quality studies; stream gauging; winch deployment; habitat mapping; infrastructure survey. |

| SR Endurance 8.0 [44] | SeaRobotics | 2022 | Offshore inspection; ocean research; ongoing marine surveillance operations. |

| DataXplorer [50] | Open Ocean Robotics | 2020 | Weather conditions; ocean currents; water depth; water temperature; MDA; asset security; illegal fishing enforcement; seafloor mapping; metocean data collection; marine mammal monitoring. |

Table A2.

USVs’ hull material, size, draft, dry weight, payload, and moonpool.

Table A2.

USVs’ hull material, size, draft, dry weight, payload, and moonpool.

| USV | Hull Material * | Size | Draft * | Dry Weight * | Payload Capacity * | Moonpool * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otter | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 2.00 m × 1.08 m × 1.06 m | 0.32 m | 62 kg | 30 kg | |

| Mariner | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 5.98 m × 2.06 m × 2.70 m | 0.50 m | 2000 kg | 400 kg | 1 (optional) |

| Mariner X | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 9.00 m × 2.50 m × 3.00 m | 0.60 m | 5000 kg | 1200 kg | 2 |

| Armada 8 (A8) | Aluminum | 7.61 m × 2.14 m | 0.99 m | 3700 kg | 1100 kg | 1 (0.85 m × 0.75 m) |

| Armada 78 (A78) | Steel | 78.00 m × 15.00 m | 5.00 m | 2,500,000 kg | 1,050,000 kg | 2 (9 m × 4 m) |

| SEA-KIT X | Aluminum | 11.75 m × 2.20 m × 8.45 m | 0.72 m | 2000 kg | ||

| Tupan | Aluminum | 4.92 m × 1.78 m × 3.34 m | 0.6 m | 200 kg | 1 | |

| Shadow Fox | 12.70 m × 3.50 m × 6.00 m | 0.7 m | 940 kg | |||

| C-Cat 3 | Polyethylene | 3.00 m × 1.60 m × 2.30 m | 0.4 m | 320 kg | 70 kg | |

| C-Worker 4 | Aluminum | 4.20 m × 1.60 m × 2.70 m | 0.6 m | 940 kg | 40 kg | |

| C-Worker 5 | Aluminum | 5.50 m × 1.80 m × 3.20 m | 0.85 m | 1250 kg | 40 kg | |

| C-Worker 7 | Aluminum | 7.5 m × 2.30 m × 6.40 m | 1.0 m | 3930 kg | 500 kg | 1 (2.5 m × 1.0 m × 1.5 m) |

| DriX H-8 | Composite construction (vacuum infusion) and Kevlar reinforced | 7.71 m × 0.82 m | 1600 kg | |||

| DriX H-9 | Composite construction (vacuum infusion) and Kevlar reinforced | 9.00 m | 2100 kg | |||

| DriX O-16 | Composite construction (vacuum infusion) and Kevlar reinforced | 15.75 m | 10,500 kg | 1000 kg | ||

| Inspector 125 | Composite Glass-Reinforced Plastic (GRP) | 12.33 m × 4.20 m × 5.25 m | 0.7 m | 13,355 kg | 2500 kg | |

| Surveyor | 20.00 m × 2.00 m | 3.0 m | ||||

| Voyager | 10.00 m × 1.80 m | 2.0 m | ||||

| Explorer | 7.00 m × 0.70 m | 2.0 m | 700 kg | |||

| Sailbuoy | 2.00 m × 0.52 m × 1.13 m | 0.57 m | 45 kg | 15 kg | ||

| XO-450 | Composite | 4.50 m × 2.20 m × 2.20 m | 750 kg | 100 kg | ||

| Sounder | 7.99 m × 2.14 m × 4.59 m | 0.7 m | 4000 kg | 1 | ||

| Wave Glider | 3.05 m × 0.81 m × 8.0 m | 8.0 m | 90 kg | 18 kg | ||

| SP-48 | 4.80 m × 1.39 m | 0.42 m | 275 kg | 70 kg | 1 | |

| L25 | Aluminum | 7.50 m × 2.80 m × 3.00 m | 0.4 m | 2400 kg | 200 kg | |

| ME120 | Composite carbon fiber | 2.50 m × 1.40 m × 0.75 m | 0.45 m | 150 kg | 45 kg | |

| M40P | Aluminum | 4.50 m × 2.33 m × 1.90 m | 0.4 m | 1400 kg | 80 kg | |

| M80 | Aluminum | 5.65 m × 2.40 m × 2.90 m | 0.45 m | 1600 kg | 200 kg | |

| M75 | Composite carbon fiber | 5.30 m × 1.72 m × 2.85 m | 0.42 m | 1350 kg | 50 kg | |

| Uni-Pact | Polyethylene | 3.00 m × 1.60 m | 0.45 m | 412 kg | ||

| Uni-Max | Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) | 5.00 m × 2.20 m | 1.0 m | 1200 kg | ||

| HydroCat-550 | Aluminum | 5.50 m × 2.50 m × 2.30 m | 362 kg | 362 kg | ||

| EchoBoat-240 | UV-resistant High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 2.40 m × 0.90 m | 158 kg | 90 kg | ||

| AutoNaut 3.5 | Composite glass–epoxy resin infusion | 3.50 m × 0.70 m | 0.6 m | 180 kg | 40 kg | |

| AutoNaut 5.0 | Composite glass–epoxy resin infusion | 5.00 m × 0.80 m | 0.8 m | 280 kg | 130 kg | |

| Lightfish | Composite | 3.00 m × 1.00 m | 122 kg | 27 kg | ||

| Mero | 5.00 m × 1.70 m | 300 kg | ||||

| C-400 | Composite fiber-reinforced polymer | 3.20 m × 1.60 m | 82 kg | |||

| WAM-V 8 | 2.50 m × 1.20 m × 0.80 m | 0.1 m | 45 kg | 45 kg | ||

| WAM-V 16 | 5.00 m × 2.50 m × 1.30 m | 0.5 m | 204 kg | 113 kg | ||

| WAM-V 22 | 7.00 m × 3.66 m × 1.50 m | 0.56 m | 544 kg | 270 kg | ||

| SR Utility 2.5 | 2.48 m × 1.24 m | 0.13 m | 70 kg | 60 kg | ||

| SR Utility 3.0 | Polyethylene | 3.12 m × 1.62 m × 2.36 m | 0.44 m | 363 kg | ||

| SR Utility 3.6 | 3.60 m × 1.80 m | 0.3 m | 125 kg | 90 kg | ||

| SR Endurance 7.0 | Aluminum | 7.00 m × 2.50 m | 1.0 m | 3200 kg | ||

| SR Endurance 8.0 | Aluminum | 8.30 m × 2.60 m | 1.0 m | 3745 kg | 600 kg | 1 |

| DataXplorer | Composite fiberglass | 3.60 m × 0.90 m | 0.5 m | 140 kg | 60 kg |

* The blank cell means that the information was not available.

Table A3.

USVs’ endurance, top speed, battery power, fuel tank capacity, and propulsion.

Table A3.

USVs’ endurance, top speed, battery power, fuel tank capacity, and propulsion.

| USV | Endurance * | Top Speed * | Battery Power * | Fuel Tank Capacity * | Propulsion * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otter | 20 h (at 2 knots) | 6 kts | Yes, 4 × lithium-ion batteries | 2 × electric motors | |

| Mariner | 50 h at 4 kts | 24 kts | 200 L | Hamilton Jet with 196 HP Yanmar diesel engine and a bow thruster for slow speed navigation | |

| Mariner X | 25 days | 12 kts | 2000 L | Hamilton Jet HJX29 and Yanmar 4LV230 with redundant twin electric pods and a bow thruster for slow speed navigation | |

| Armada 8 (A8) | 7 days at 4 kts | 7 kts | |||

| Armada 78 (A78) | 35 days | ||||

| SEA-KIT X | 14 days | 6 kts | Yes | 2000 L | 2 × 10 kW/1200 rpm electric directional thrusters; 1 × 12 kW/2000 rpm Azipod thruster |

| Tupan | 11 days | 6.5 kts | Electric, two propellers 4.5 kW each | ||

| Shadow Fox | 40 kts | 1500 L | 2 × Cummins QSB, 6.7 inboard engines (550 HP each) with Hamilton 292 waterjets | ||

| C-Cat 3 | 8 h | 10 kts | Yes | 2 × 24V DC electric motors driving 3-bladed propellers | |

| C-Worker 4 | 48 h at 3.5 kts | 6 kts | 110 L | 30 HP inboard diesel engine driving a waterjet | |

| C-Worker 5 | 4 days at 7 kts | 10 kts | 770 L | 57 HP inboard diesel engine and sail drive | |

| C-Worker 7 | 25 days at 2 kts | 6 kts | 1170 L | 2 × 20 kW Aziprops driving 4-bladed Kaplan propellers | |

| DriX H-8 | 10 days | 14 kts | 250 L | 37.5 HP diesel engine | |

| DriX H-9 | 20 days | 13 kts | 550 L | ||

| DriX O-16 | 30 days | 16 kts | 2300 L | Hybrid propulsion with one electric pod that can rotate 360° | |

| Inspector 125 | 40 h | 25 kts | Engines: Cummins QCB 8.3; engines’ power: 2 × 442 kW; waterjets: MJP X310. | ||

| Surveyor | 17 days under power, 3+ months under sail | Wind (Saildrone wing); auxiliary: 78 HP high-efficiency diesel. | |||

| Voyager | 3+ months under sail | Wind (Saildrone wing); auxiliary: 4 kW electric motor. | |||

| Explorer | 12+ months | Wind (Saildrone wing) | |||

| Sailbuoy | 12 months | 4 kts | Wind | ||

| XO-450 | 18 days | 4 kts | Twin electric thrusters + bow thrusters | ||

| Sounder | 20 days at 4 kts | 13 kts | 400 L | 125 HP Steyr diesel engine with fixed pitch propeller | |

| Wave Glider | 12 months | Yes, 0.9–6.8 kWh rechargeable | Mechanical conversion of wave energy into forward propulsion | ||

| SP-48 | Months | 5 kts | Yes, 6.75 kWh (Lithium) | 1000 W brushless Motor | |

| L25 | 65 h at 4 kts | 10 kts | 350 L | Propeller × 2 + outboard diesel engine 50 HP × 2 | |

| ME120 | 8 h at 4 kts | 10 kts | Duct-type thruster | ||

| M40P | 100 h at 4 kts | 7 kts | 100 L | Electric propulsion with differential steering | |

| M80 | 50 h at 6 kts | 10 kts | Diesel engine with waterjet thrusters (electric motor) | ||

| M75 | 6 h at 20 kts | 26 kts | 120 L | Diesel engine YANMAR 110 HP + Alamarin waterjet 260 HP | |

| Uni-Pact | 8 h | 5 kts | Yes, 1 × 13.25 V/180Ah Li-ion battery; | 1 × 24 VDC electric engines (Torqeedo Cruise 2.0RS) | |

| Uni-Max | 96 h under battery and 5 to 6 days under diesel generator | 5 kts | 2 × Torqeedo Cruise 6.0RS with diesel-powered generator (hybrid) | ||

| HydroCat-550 | 8 h | 12 kts | 2 × 25 HP equivalent Torqueedo motors with electric tilt/trim | ||

| EchoBoat-240 | 8 h at 2 kts | 4 kts | Yes | 2 × brushless DC outdrive | |

| AutoNaut 3.5 | 3 kts | Wave foil technology. Wave/electric hybrid options. | |||

| AutoNaut 5.0 | 3 kts | Wave foil technology. Wave/electric hybrid options. | |||

| Lightfish | 6 months | 4.5 kts | Electric | ||

| Mero | 60 h | 50 L | 2 × 2 kW electric motors | ||

| C-400 | 10 h under battery | 3 kts | Yes | ||

| WAM-V 8 | 10 h at 3 kts | 6 kts | 2 × 400 W electric; 4 × 400 W electric; 2 × 1100 W electric. | ||

| WAM-V 16 | 15 h at 5 kts | 11 kts | 2 × 2 kW electric | ||

| WAM-V 22 | 72 h at 8 kts | 20 kts | 151 L | 2× 20 HP gasoline; 2× 30 HP gasoline | |

| SR Utility 2.5 | 11 h at 3.0 kts; 6.5 h at 4.0 kts; 20 h at 3.0 kts; 12.5 h at 4.0 kts; | 7.5 kts | Electric | ||

| SR Utility 3.0 | 20 h at 2 kts; 10 h at 3 kts; 6 h at 4 kts; | 6 kts | 2 × Torqeedo Cruise 2.0R electric thrusters | ||

| SR Utility 3.6 | 11 kts | Electric | |||

| SR Endurance 7.0 | 3 days at 5 kts; 6 days at 4 kts; | 10 kts | Diesel; electric; diesel–electric hybrid. | ||

| SR Endurance 8.0 | 9 days at 5 kts | 10 kts | 760 L | 55 kW continuous | |

| DataXplorer | 6 kts | Yes, 17.5 kWh battery and 300 W solar panel | 3 HP equivalent motor |

* The blank cell means that the information was not available.

Table A4.

USVs’ Sea state, Communication, and Situational awareness technologies.

Table A4.

USVs’ Sea state, Communication, and Situational awareness technologies.

| USV | Sea State | Communication | Situational Awareness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otter | 2 | MIMO radio, Wi-Fi, 4G | Camera, AIS Class B |

| Mariner | 4 for survey, 6 for transit, 7 for survival <E (4G) | Camera, AIS class B, radar | |

| Mariner X | 4 for survey, 6 for transit, 7 for survival <E (4G) | Camera, AIS class B, radar | |

| Armada 8 (A8) | Iridium, RF radios, VHF | ||

| Armada 78 (A78) | VHF, point-to-point, point-to-multipoint radio, satellite communications, 4G, LTE | ||

| SEA-KIT X | 7 | VHF, DSC, Wi-Fi, radio, satellite, Iridium, Inmarsat | |

| Tupan | 5 | Wi-Fi, 5G, COFDM and satellite | |

| Shadow Fox | IP mesh radio, UHF, VHF, satellite, 4G, Wi-Fi | ||

| C-Cat 3 | 2 | 100 mW COFDM IP mesh radio; tuneable RF channel bandwidths of 1.25 MHz to 10 MHz; 4G; Wi-Fi | 360-degree camera |

| C-Worker 4 | 4 for operations, 5 for survival | 5 W COFDM IP mesh radio, tuneable RF channel bandwidths of 1.25 MHz to 10 MHz, 4G, Wi-Fi | 360-degree camera and one forward-facing thermal (IR) camera |

| C-Worker 5 | 3 | 5 W COFDM IP mesh radio, tuneable RF channel bandwidths of 1.25 MHz to 10 MHz, 4G, Wi-Fi | 360-degree camera and one forward-facing thermal (IR) camera |

| C-Worker 7 | 4 for operations, 5 for survival | 5 W COFDM IP mesh radio, tuneable RF channel bandwidths of 1.25 MHz to 10 MHz, 4G, Wi-Fi | 360-degree camera and six thermal (IR) cameras |

| DriX H-8 | 5 | Wi-Fi, 4G, satellite communication, UHF radio | Video and IR cameras, LiDAR, radar |

| DriX H-9 | 5 | Wi-Fi, 4G, satellite communication, UHF radio | Video and IR cameras, LiDAR, radar |

| DriX O-16 | Wi-Fi, 4G, satellite communication, UHF radio | Video and IR cameras, LiDAR, radar | |

| Inspector 125 | 4 unmanned; 5 manned; 4 LARS deployment; | ||

| Surveyor | Starlink, Iridium | Radar, cameras | |

| Voyager | Starlink, Iridium | Radar, cameras | |

| Explorer | Iridium | ||

| Sailbuoy | Iridium, GSM, VHF | ||

| XO-450 | Satellite communication | AIS, thermal imaging camera, visible light cameras, image detection | |

| Sounder | 4G, Starlink, MBR, Iridium | PTZ camera, main camera, radar, AIS, sensor fusion | |

| Wave Glider | 4 | Cell, satellite, Wi-Fi, line-of-sight radio | AIS |

| SP-48 | 7 function, 11 survive | Satellite, cellular, radio, Wi-Fi | AIS, visible running lights, 360-degree camera system |

| L25 | 3 for operations, 4 for survival | Radio, satellite | Radar, 4 × HD camera, AIS |

| ME120 | Millimeter-wave radar | ||

| M40P | 3 for operations, 4 for survival | Radar, 4 × 720P HD camera, AIS | |

| M80 | 3 | Wi-Fi, 4G LTE | Millimeter-wave radar |

| M75 | 3 for operations, 4 for survival | Navigation radar, LiDAR, AIS, camera | |

| Uni-Pact | 4G, Wi-Fi, mesh radio | ||

| Uni-Max | 4G, uni-mesh radio, remote redundancy frequency controller | Radar | |

| HydroCat-550 | 5 | Wi-fi | LiDAR, camera |

| EchoBoat-240 | UHF telemetry | ||

| AutoNaut 3.5 | Satellite | AIS | |

| AutoNaut 5.0 | Satellite | AIS | |

| Lightfish | 6 | ||

| Mero | |||

| C-400 | |||

| WAM-V 8 | Short-range radio, encrypted wireless network | 180° FOV camera | |

| WAM-V 16 | Short-range radio, encrypted wireless network | 180° FOV camera | |

| WAM-V 22 | Short-range radio, encrypted wireless network | 180° FOV camera | |

| SR Utility 2.5 | 3 | BLOS options cellular, satellite, RF | |

| SR Utility 3.0 | |||

| SR Utility 3.6 | BLOS options cellular, satellite, RF | ||

| SR Endurance 7.0 | Wi-Fi, cellular, satellite | ||

| SR Endurance 8.0 | 7 for operations, 9 for survival | Wi-Fi, RC transmitter, UHF | 360-degree field-of-view cameras |

| DataXplorer | 3G, 4G, LTE cellular, satellite, radio | 360-degree camera, AIS |

References

- Yang, P.; Xue, J.; Hu, H. A Bibliometric Analysis and Overall Review of the New Technology and Development of Unmanned Surface Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Gao, M.; Zhou, M.; Ma, Z. Artificial intelligence algorithms in unmanned surface vessel task assignment and path planning: A survey. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 86, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Xiao, Y. A Review of Current Research and Advances in Unmanned Surface Vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2022, 21, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.G.; Lawson, E.; Udyawer, V.; Brassington, G.B.; Groom, R.A.; Campbell, H.A. Uncrewed Surface Vessel Technological Diffusion Depends on Cross-Sectoral Investment in Open-Ocean Archetypes: A Systematic Review of USV Applications and Drivers. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 736984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Che, X.; Chengyang, L.; Jiageng, D.; Hui, H. Parameter optimization of unmanned surface vessel propulsion motor based on BAS-PSO. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2022, 19, 172988142110406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, D.V.; Vey, N.L.; Kylander, P.W.; Auld, S.G.; Willis, J.J.; Lussier, J.F.; Eldred, R.A.; Van Bossuyt, D.L. Electrical Energy Storage Strategy to Support Electrification of the Fleet; Naval Postgraduate School: Monterey, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/trecms/AD1202053 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Castano-Londono, L.; Marrugo Llorente, S.d.P.; Paipa-Sanabria, E.; Orozco-Lopez, M.B.; Fuentes Montaña, D.I.; Gonzalez Montoya, D. Evolution of Algorithms and Applications for Unmanned Surface Vehicles in the Context of Small Craft: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Fan, X.; Ren, J. Asynchronous Multithreading Reinforcement Control Decision Method for Unmanned Surface Vessel. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 22806–22822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Naeem, W.; Irwin, G. A review on improving the autonomy of unmanned surface vehicles through intelligent collision avoidance manoeuvres. Annu. Rev. Control 2012, 36, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlianko, H.; Kharchenko, V. Ensuring Cybersecurity of the Cyber Physical System of Combined Fleets of Unmanned Aerial, Ground and Sea Vehicles. In Integrated Computer Technologies in Mechanical Engineering—2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanakitkorn, K. A review of unmanned surface vehicle development. Marit. Technol. Res. 2019, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yuan, C. Unmanned surface vehicles: An overview of developments and challenges. Annu. Rev. Control 2016, 41, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gu, S.; Wen, Y.; Du, Z.; Xiao, C.; Huang, L.; Zhu, M. The review unmanned surface vehicle path planning: Based on multi-modality constraint. Ocean Eng. 2020, 200, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Yu, M.; Liu, Z.; Tan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, B. A Review of Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, M.J.; Ma, C.; Liu, T.; Gong, H. Intelligent motion control of unmanned surface vehicles: A critical review. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, M.H.M.; Satar, M.H.A.; Rahiman, W. Unmanned surface vehicles: From a hull design perspective. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 118977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, C.; Huang, J.; Chen, H. Model-free adaptive control for unmanned surface vessels: A literature review. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2024, 12, 2316170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Kim, J.; Kwon, Y. Analysis of Design Directions for Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs). J. Comput. Commun. 2017, 05, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, J.E. Waypoints on the Voyage to Autonomous Ships. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE, Seattle, WA, USA, 27–31 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S. Developments in Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs): A Review. Int. Conf. Appl. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2023, 1, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammineni, P. Adaptive Control Systems in Unmanned Surface Vehicles: Harnessing the Power of AI and ML. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 12, 1324–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Jia, S.; Chen, S.; Ma, L. Embodied intelligence in unmanned surface vehicles: Current applications and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms, High Performance Computing, and Artificial Intelligence (AHPCAI 2024), Zhengzhou, China, 21–23 June 2024; Loskot, P., Hu, L., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Song, Y.; Hu, H. Formation Control of a Multi-Unmanned Surface Vessel System: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzengu, W.; Faivre, J.; Pauwelyn, A.S.; Bolbot, V.; Lien Wennersberg, L.A.; Theotokatos, G. Regulatory framework analysis for the unmanned inland waterway vessel. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2021, 20, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Theotokatos, G.; Maslov, I.; Wennersberg, L.A.L.; Nesheim, D.A. Regulatory and legal frameworks recommendations for short sea shipping maritime autonomous surface ships. Mar. Policy 2024, 166, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komianos, A. The Autonomous Shipping Era. Operational, Regulatory, and Quality Challenges. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2018, 12, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooydonk, E. The law of unmanned merchant shipping—An exploration. J. Int. Marit. Law 2014, 20, 403–423. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, N. The international legal status of the unmanned maritime vehicles. Mar. Policy 2020, 113, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAO. Coast Guard: Autonomous Ships and Efforts to Regulate Them; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Fenton, A.J.; Chapsos, I. Ships without crews: IMO and UK responses to cybersecurity, technology, law and regulation of maritime autonomous surface ships (MASS). Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 1151188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Infinity. Armada 78 USV. Available online: https://oceaninfinity.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/OI-ARMADA78-Spec-Sheet-2023.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Negenborn, R.R.; Goerlandt, F.; Johansen, T.A.; Slaets, P.; Valdez Banda, O.A.; Vanelslander, T.; Ventikos, N.P. Autonomous ships are on the horizon: Here’s what we need to know. Nature 2023, 615, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.A.A.; Sathyamoorthy, D.; Nasuddin, N.M.; Nawi, N.M.; Mansor, M.N.; Sulaiman, N.E.S.; Yaacob, R.; Ramli, R.; Rashid, M.R.M.; Ramli, I.; et al. Development of a prototype unmanned surface vessel (usv) platform. Def. S&T Tech. Bull. 2013, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, R.; Daltry, R.; Dobbin, V.; Lachaud, E.; Miller, I. Design Process and Validation of an Autonomous Surface Vehicle for the Offshore Industry. In Proceedings of the Day 2 Wed, October 28, 2015, OTC, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 27–29 October 2015. 15OTCB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobref, V.; Popa, I.; Popov, P.; Scurtu, I.C. Unmanned Surface Vessel for Marine Data Acquisition. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 172, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.; Faria, H. Advancing Unmanned Surface Vessel Design: A Circular Economy Response to Global Conflict Evolution. In Proceedings of the Conference on Social Sciences, iSCSS, Liverpool, UK, 5–7 November 2024; Volume 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, T.; Geng, T. The Wireless Communications for Unmanned Surface Vehicle: An Overview. In Intelligent Robotics and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, O.K.; Brekke, E.F.; Helgesen, H.H.; Engelhardtsen, O. Sensor Combinations in Heterogeneous Multi-sensor Fusion for Maritime Target Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2019 22th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2–5 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Son, N.; Kim, S.Y. Autonomous collision detection and avoidance for ARAGON USV: Development and field tests. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steimle, E.T.; Hall, M.L. Unmanned Surface Vehicles as Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Tools. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2006, Boston, MA, USA, 18–22 September 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J. How USVs can Change the Offshore Inspection Market Through Novel Operating Models. In Proceedings of the Day 1 Mon, May 06, 2024, OTC, Houston, TX, USA, 6–9 May 2024. 24OTC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.A.; Haris, M.; Saeed, N. Beyond Line of Sight Defense Communication Systems: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.06491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, E. Autonomy as an enabler of economically-viable, beyond-line-of-sight, low-altitude UAS applications with acceptable risk. In Proceedings of the AUVSI unmanned Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–15 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SeaRobotics. SR Endurance Class USVs. Available online: https://www.searobotics.com/products/autonomous-surface-vehicles/sr-endurance-class (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Mouly, M.; Pautet, M.B. The GSM System for Mobile Communications; Telecom Publishing: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]