Abstract

This work presents an energy-efficient implementation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based systems over 5G networks with on-board accelerated processing capabilities and provides a preliminary evaluation of the integrated solution. The study is a two-fold comparative analysis focused on connectivity and edge processing for UAVs. Two discrete deployment scenarios are implemented, where standard 5G configuration with artificial neural network (ANN) processing is evaluated against 5G Reduced Capability (RedCap) connectivity, paired with Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). Both proposed energy-efficient alternative solutions are designed to offer significant energy savings; this paper examines whether they are suitable candidates for energy-constrained environments, i.e., UAVs, and quantifies their impact on the overall energy consumption of the system. The integrated solution, with 5G RedCap/SNNs, achieves energy-use reductions approaching 60%, which translates to an approximate 35% increase in flight time. The experimental evaluations were performed in a real-world deployment using a 5G-equipped UAV with edge-processing capabilities based on NVIDIA’s Jetson Orin.

1. Introduction

The emergence of decentralized technologies and network communications, along with the introduction of heterogeneous devices at the edge, i.e., unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), has created the need for new requirements for the design and deployment of telco 5G and 6G applications in terms of energy efficiency [1]. The emergence of energy-limited edge devices, especially in the case of UAVs with limited battery power, limits the use of performant artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) enablers on-board, thus not truly exploiting the edge processing proximity [2]. Primarily, 5G communications have been utilized as a connectivity pathway for UAVs; numerous applications and multiple works [3] have showcased the benefits and limitations of this convergence. In this respect, 5G Reduced Capability (RedCap) has been implemented, which promises to provide 5G bandwidth performance with significant power savings compared to standard 5G deployments [4,5].

With respect to AI/ML processing, artificial neural networks (ANNs) are general-purpose neural networks that can be used for a wide range of tasks. These tasks include classification, regression, and pattern recognition, and they have been widely applied in various applications [6], including object classification in image processing. However, the training, as well as the inference of this type of models, is computationally intensive and can significantly reduce UAV flight time when deployed at an edge scenario. A novel approach for edge processing is based on SNNs, which are a type of artificial neural network that more closely mimics biological neurons by communicating through discrete “spikes” rather than continuous values. This “third-generation” network integrates the concept of time into its operations, making it particularly well-suited for time-series analysis and applications like robotics and radar, while also being more energy-efficient due to its asynchronous, event-driven processing. Nonetheless, its main advantage lies in its energy efficiency and processing speed, since, due to their event-driven and sparse nature, computations only occur when a neuron “spikes”, rather than at every time step, compared to ANNs and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [7].

This paper introduces a hybrid approach for energy-efficient edge processing, focusing on the energy limitations of UAV devices. UAV devices have been extensively used as relays, or user equipment (UE), in 5G networks, where control communications or data are transferred from on-board sensors using the 5G channel. Additionally, various works have used on-board advanced processing units, e.g., Raspberry Pi, Jetson Nano, etc., for in-flight processing to minimize processing latency, but this consumes significantly more battery power in an already energy-capped environment [8]. In this work, a comprehensive experimental analysis and evaluation of the energy efficiency of alternative connectivity and processing enablers, i.e., 5G RedCap and SNNs, is carried out and portrays how targeted modules in the different parts of an edge ecosystem can provide substantial energy benefits and increase the flight time of UAVs.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 1 provides the incentive and scope of the work. Section 2 provides an extensive analysis on related work and what has been achieved in the relevant field. In Section 3, the proposed solution is presented and extended experimental evaluations are depicted, showcasing the benefits of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 4 concludes the outcomes of the paper and provides an outlook on the next steps of the work.

2. Related Work

This section covers the relevant work in the field of energy efficiency at the edge, leveraging either different connectivity setups, or alternative acceleration enablers. The state-of-the-art study aims to provide an analysis both from the scope of related energy-efficient methods in 5G, more specifically, 5G RedCap, and how these can benefit edge IoT devices under energy-constrained conditions. In parallel, the study also covers how SNNs and related neural network approaches can be applied in different scenarios to significantly reduce energy consumption. In the context of energy efficiency, most related work focuses on a single domain of the technology stack—either connectivity or processing acceleration. In this work, a converged approach is proposed based on both the alternative 5G connectivity methods available, as well as low-power edge acceleration, i.e., SNNs. The convergence of 5G wireless technologies, neuromorphic computing, and energy-efficient edge processing can act as an accelerator in distributed intelligence systems. This section reviews recent advances across multiple interconnected domains that helped build the foundations of the presented work on leveraging 5G RedCap and SNNs for energy efficiency in edge devices, with particular emphasis on aerial applications.

2.1. 5G Reduced Capability Technology for IoT and Edge Devices

5G Reduced Capability (RedCap), standardized in 3GPP Release 17 and finalized in mid-2022, addresses a critical gap between high-end 5G capabilities and low-power wide-area technologies [9]. The key technical specifications include a reduced bandwidth (20 MHz maximum in FR1 versus 100 MHz for conventional 5G NR), simplified antenna configurations supporting 1–2 receive branches rather than 2–4, and a maximum of 2 MIMO layers [10]. These architectural simplifications promise to yield an approximately 65% reduction in modem complexity for FR1 devices and 50–60% lower module costs compared to full 5G implementations [11].

From an energy efficiency perspective, RedCap introduces several critical features. The extended Discontinuous Reception (eDRX) mechanism supports DRX cycles up to 10,485 s (nearly 3 h) in the RRC idle state, compared to the 2.56 s maximum in earlier releases [12]. This enables a 10–70× battery lifetime extension depending on the traffic patterns [13]. Additionally, Radio Resource Management (RRM) relaxation reduces the measurement overhead for stationary or low-mobility devices. Industry validation from Samsung and MediaTek deployment in the State Grid Shandong network achieved a 32% energy reduction, with RedCap terminals utilizing eDRX and measurement relaxation features [13].

2.2. Spiking Neural Networks for Energy-Efficient Edge Computing

SNNs represent a neural architectural shift toward brain-inspired, event-driven computing that offers substantial energy advantages to edge deployments. However, recent research reveals that achieving energy efficiency requires careful architectural design and delicate vector parameterization. A 2024 analysis reconsidering SNN energy efficiency demonstrates that, for the VGG16 architecture with time window T = 6, SNNs require a greater than 93% sparsity rate to achieve energy advantages over conventional ANNs on most hardware architectures [14]. This finding establishes critical design constraints: energy efficiency depends fundamentally on achieving a high activation sparsity and minimizing the temporal window size during inference.

Despite these constraints, practical implementations demonstrate substantial energy savings in favorable scenarios. The Synsense Xylo neuromorphic processor, combining analog preprocessing with digital SNN inference, achieved a 60.9× dynamic inference power reduction and a 33.4× dynamic inference energy reduction versus the Arduino baseline on acoustic scene classification tasks while maintaining a comparable 90% accuracy [15]. Intel’s Loihi 2 neuromorphic processor demonstrated 37.24× lower power consumption than a CPU on QUBO optimization tasks, with the ability to solve workloads 4× larger than a CPU at a 10−2 s timeout [16]. The fundamental advantage derives from replacing multiply–accumulate operations (3.2 pJ) with simple accumulations (0.1 pJ), yielding a 32× energy advantage per operation, which compounds with activation sparsity to achieve a 320× theoretical energy reduction versus equivalent RNNs when the sparsity exceeds 90% [17].

2.3. Neuromorphic Hardware Platforms

Intel’s Loihi series is the most widely deployed neuromorphic research platform. The original Loihi chip (2017–2018) integrated 128 neuromorphic cores supporting 130,000 neurons and 130 million synapses in 14 nm CMOS, achieving a 1000× energy efficiency improvement over conventional GPUs on specific workloads [18]. Loihi 2 (2021–present) delivers 10× faster processing and up to 12× higher performance, supporting 1 million neurons and 120 million synapses per chip with programmable neuron models via a microcode-based architecture [19]. The Hala Point system scales this to 1.15 billion neurons across 1152 Loihi 2 chips, achieving a 20-petaops throughput with greater than 15 trillion 8-bit operations per second per watt efficiency [20]. IBM’s evolution from TrueNorth (1 million neurons, 70 mW power consumption) to NorthPole (2023) demonstrates continued progress, with NorthPole achieving 22× faster processing than TrueNorth and 25× less energy than GPUs on an equivalent 12 nm process while occupying 5× less physical space [20].

2.4. Learning Algorithms and Training Methods

Surrogate gradient methods have emerged as the prime training approach for deep SNNs, addressing the non-differentiability of spike generation by replacing Heaviside step function derivatives during backpropagation [21]. Common surrogate functions include boxcar/rectangular, sigmoid derivative, exponential, and piecewise linear approximations. This approach enables competitive performance: 94.51% accuracy on speech command recognition and 94.62% on Heidelberg Digits dataset, surpassing the CNN baselines while retaining precise spike timing information [19]. Recent advances include adaptive surrogate gradients using χ-based training pipelines, temporal regularization enforcing stronger constraints on early timesteps, and ADMM-based training avoiding non-differentiability issues entirely [22]. Online Training Through Time (OTTT) achieves constant memory consumption regardless of timesteps, while Spatial Learning Through Time (SLTT) reduces memory by up to 10× by ignoring unimportant computational graph routes [23]. Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) offers biologically plausible local learning but struggles to scale to supervised deep-learning tasks, finding primary application in unsupervised feature extraction and hardware-friendly implementations [19]. ANN-to-SNN conversion provides an alternative deployment path, achieving near-lossless conversion with proper quantization-aware training, though requiring sufficient temporal resolution for rate coding convergence [24].

2.5. Edge Computing Applications

SNNs demonstrate particular strength in temporal processing and always-on sensing applications. The NeuroBench 2025 framework provides standardized benchmarks revealing state-of-the-art performance: acoustic scene classification achieves 90% accuracy at 0.16 W versus 9.75 W for conventional processing, while event camera object detection with hybrid ANN-SNN architectures achieves 0.271 mAP with one order of magnitude fewer operations than pure ANN approaches [10]. The EC-SNN framework for split deep SNNs across edge devices achieves a 60.7% average latency reduction and a 27.7% energy consumption reduction per device through channel-wise pruning while maintaining accuracy across six datasets [25].

Distributed SNN architectures for wireless edge intelligence demonstrate significant advantages. Multiple edge nodes with spiking neuron subsets collaborating over wireless channels achieve power reductions while ensuring inference accuracy, with SNNs proving much more bandwidth-efficient than RNNs due to sparse spike communication [26].

2.6. Energy Efficiency Optimization in Edge Devices

Energy efficiency in edge computing encompasses hardware, software, and communication-level optimizations. This challenge has produced different solutions addressing different aspects of the energy consumption problem.

Power management through Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) remains fundamental for heterogeneous multicore edge processors [27]. Liu et al. demonstrate a novel algorithm integrating task prioritization, core-aware mapping, and predictive DVFS on ARM Cortex-A15/A7 heterogeneous platforms, achieving a 20.9% energy reduction compared to Earliest Deadline First scheduling, 11.4% versus HEFT, and 5.9% versus Energy-Aware Scheduling, while maintaining a 2.4% deadline miss rate (lowest among compared algorithms) and achieving 19.5 work units per joule energy efficiency [28]. Deep reinforcement learning approaches to DVFS using Deep Q-learning on Jetson Nano achieve a 3–10% power reduction versus Linux built-in governors across 3–8 concurrent task workloads [29]. These techniques prove particularly relevant for battery-powered edge devices with heterogeneous processors common in ARM big.LITTLE architectures deployed in wireless edge scenarios.

2.7. Hardware Accelerators for Edge AI

Specialized accelerators demonstrate improvements in energy efficiency versus general-purpose processors [30]. Google’s Coral Edge TPU delivers targeted ASIC performance at 2 W for the USB accelerator and 0.5 W for the M.2 module configurations, enabling multi-year battery life for always-on inference applications [31]. Hailo-8 achieves up to 26 TOPS at 2.5–5 W typical power consumption with an area and power efficiency superior to competing solutions by an order of magnitude, while the newer Hailo-10 delivers 40 TOPS at less than 5 W, processing Llama2-7B LLM at 10 tokens per second and generating Stable Diffusion 2.1 images every 5 s—double the performance of Intel Core Ultra NPU at half the power [32]. Axelera AI’s Metis AIPU scales to 214 TOPS with a 1–16 GB dedicated DRAM at less than 10 W for retail analytics applications, achieving a 97% order accuracy versus 90–95% for traditional systems [33]. Microcontroller-class devices increasingly integrate neural accelerators. The Renesas RA8P1 MCU with Arm Ethos-U55 NPU delivers up to 256 GOPS while maintaining MCU-level power consumption suitable for battery-powered applications [34].

2.8. Integration of Wireless Communications with Neural Networks

The integration of advanced wireless technologies with neural network processing at the edge is an emerging topic with noteworthy energy efficiency implications. The recent work demonstrates the promising integration of SNNs with wireless communication systems [35]. SNNs consume approximately 10× less energy than ANNs for beamforming (0.002 mJ versus 0.018 mJ per optimization) while achieving comparable or superior performance through event-driven spike processing. For OFDM channel estimation, SNNs prove 3.5× more energy-efficient than conventional neural approaches and 1200× more efficient than traditional ChannelNet (0.0018 mJ versus 2.19 mJ). The framework incorporates domain knowledge into the SNN architecture using LIF neurons with surrogate gradient training and addresses catastrophic forgetting in dynamic wireless environments through hypernet gates and spiking rate consolidation.

Federated neuromorphic learning for wireless edge AI has shown significant practical advantages. Lead Federated Neuromorphic Learning achieves a greater than 4.5× energy savings compared to standard federated learning with a less than 1.5% accuracy loss, alongside the 3.5× data traffic reduction and 2.0× computational latency reduction using Meta-Dynamic Neuron architectures [36]. This privacy-preserving approach enables speech recognition, image classification, health monitoring, and multi-object detection on edge devices connected via wireless networks without sharing raw data, only model parameters [36].

2.9. Edge AI over 5G Networks

The convergence of 5G connectivity with edge neural network processing enables sophisticated distributed intelligence architectures. The Edgent framework demonstrates device-edge synergy for DNN inference through adaptive DNN partitioning (splitting networks between device and edge) and DNN right-sizing (early exiting at the appropriate intermediate layers), optimizing the computation–communication tradeoff in 5G environments [37]. Split computing frameworks for UEs, edge nodes, and core devices reduce the user equipment computational footprint by over 50% while containing inference time, proving robust in heterogeneous settings typical of 5G and emerging 6G networks [38].

Network-aware 5G edge computing implementations demonstrate practical deployment [39]. Machine-learning-based dynamic resource scheduling for 5G network slicing using reinforcement learning and CNNs outperforms heuristic and best-effort approaches for low-latency services [40]. However, the substantial energy increase of 5G RAN—consuming 4–5× more energy than 4G networks despite per-bit efficiency improvements—motivates the exploration of neuromorphic and efficient AI approaches [39]. ML-based digital predistortion for power amplifiers uses neural networks to replace Volterra-based linearization, reducing the optimization time from days to hours while enabling the dynamic correction of nonlinear PA behavior with reduced computational requirements [41].

2.10. Research Gaps in RedCap-AI Integration

Despite the active 5G RedCap deployment for IoT connectivity and the demonstrated advantages of neuromorphic computing, research specifically combining RedCap with neural network inference—particularly SNNs—remains extremely sparse. While RedCap standardization focuses on reduced complexity and extended battery life targeting wearables, industrial sensors, and video surveillance [1,3,4], the optimization of neural network processing for RedCap device characteristics has received minimal attention. This represents a significant opportunity: RedCap infrastructure deployment accelerated in 2023–2024, with AT&T achieving nationwide coverage exceeding 200 million points of presence, Qualcomm releasing Snapdragon X35 modem-RF systems, and commercial modules from Fibocom, Quectel, and other manufacturers entering production [41]. However, research on AI inference optimization specifically for RedCap’s bandwidth constraints (20 MHz FR1), simplified antenna configurations (1–2 Rx branches), and power-saving features (eDRX, RRM relaxation) has not materialized in peer-reviewed literature. Similarly, the potential synergy between RedCap’s energy-saving features and SNN’s sparse, event-driven processing remains unexplored, despite both technologies targeting energy-constrained edge applications.

3. Experimental Evaluation of 5G RedCap and SNNs for Edge Deployments and Energy Efficiency Measurement

In this paper, the focus on energy efficiency and saving is two-fold both from the connectivity perspective and the edge processing one. Since the targeted environments, i.e., UAVs, have limited energy and payload capacity, processing on-board must be efficient. In this aspect, the proposed work performs a dual experimental implementation and evaluation, both on the connectivity and the edge processing parts, using 5G RedCap and the integration of SNN. This section provides an overall analysis of the integration steps required to implement such a setup and also presents the corresponding energy consumption evaluations of each setup.

3.1. 5G RedCap Configuration Analysis

Table 1 shows both 5G configuration setups side by side, and details what is actually modified in the process of enabling the RedCap configuration. Additionally, Table 1 clarifies how RedCap differs from the standard 5G configuration.

Table 1.

Comparison of standard 5G NR and 5G RedCap configuration parameters.

Table 1 explains how each configuration choice in the table affects the device complexity, radio behavior, and energy use when moving from standard 5G NR to RedCap. In the baseline sample, standard 5G NR operates with a wider bandwidth and typical duplexing, while RedCap narrows the operation to reduce the complexity and power. When the network configures a narrower carrier (or a RedCap-only bandwidth part inside a wider carrier), the user equipment processes a smaller slice of the spectrum. This directly reduces the effort in the RF front-end and baseband, helping the device save power without breaking compatibility with the rest of the cell. The antenna and MIMO choices also change: RedCap limits the receive diversity and the number of layers, which removes RF chains and signal-processing paths. This simplifies the hardware and lowers both the idle and active power, at the cost of some peak throughput that is usually not needed for telemetry and command-and-control traffic. The modulation and coding settings further reflect this trade-off. While the downlink can remain capable, the uplink often uses a more conservative table (for example, capping at 64-QAM) to ease the power amplifier requirements and processing load. The initial access and identification steps are streamlined so the device can camp and attach on the narrow RedCap bandwidth part from the start, avoiding wideband scanning and unnecessary measurements. The control signaling is tuned in the same direction: the uplink control channels are placed and sized to work efficiently within the narrow bandwidth part, and common system information includes RedCap-specific fields, so the device applies the right behavior immediately. Duplex assumptions at the scheduler can start conservatively, matching the simpler RedCap profile, and then adjust if the device indicates different capabilities. Resource allocation can reserve small regions for control and pack data grants around them to use the narrow bandwidth part efficiently. Carrier aggregation and dual connectivity are typically disabled for RedCap devices, which removes background measurements and coordination overhead. Overall, the pattern is consistent: the peak throughput and feature breadth are traded for a lower complexity, less measurement activity, and a steadier operation in a smaller channel. For an energy-limited UAV, these choices translate into a lower radio and baseband power draw while maintaining the reliability needed for control links and moderate data bursts, aligning with the endurance goals discussed later in the evaluation.

3.2. SNN Implementation Analysis

SNNs are less commonly used for object detection and are more often applied to temporal/event-based vision data [42]. Therefore, a dedicated implementation and re-training on each extracted frame was performed, which included the conversion to grayscale and resizing to 28 × 28 pixels. This step is critical for standardizing the input for the SNN model. The SNN model was designed with a layer of 784 input neurons (corresponding to the 28 × 28 pixel input), 1000 hidden neurons, and 10 output neurons, and trained using the Contrastive Hebbian Learning rule. This architecture was selected for its balance between complexity and computational efficiency. A sliding window approach is implemented to scan each frame. Windows of size 64 × 64 pixels move across the frame with a step size of 32 pixels. Each window is processed to detect rust, and bounding boxes are drawn around the detected areas.

Recent work has reinforced the suitability of SNNs for resource-constrained edge and wireless scenarios. Liu et al. design an energy-efficient distributed SNN for wireless edge intelligence in [27], demonstrating that a carefully coordinated SNN across multiple edge nodes can match the recurrent neural network (RNN) accuracy while substantially reducing the edge-device power and improving the bandwidth efficiency under limited-bandwidth constraints [27]. On the hardware side, [43] implements an SNN version of LeNet-5 on FPGA and report 33% less area and a 4× reduction in power per neuron (348 mW total) compared to the state-of-the-art digital SNN accelerators, highlighting that compact SNNs are attractive building blocks for ultra-low-power edge deployments [44]. Mapping toolchains such as EdgeMap further show that, when SNNs are deployed on neuromorphic edge hardware, the latency can be reduced by up to 19.8%, the energy consumption by 57%, and the communication cost by 58%, while improving the throughput by 4.02× relative to prior mapping schemes [44]. In parallel, Li et al. in [42] recently demonstrated that SNNs can be extended beyond classification to object detection, with the AMS_YOLO and AMSpiking_VGG models improving the SNN detection accuracy by 6.7 percentage points on COCO2017 and 11.4 percentage points on GEN1 compared to earlier SNN baselines [42]. Motivated by these trends, our work adopts a deliberately small patch-level SNN classifier (784–1000–10) as an energy-efficient gate for rust/no-rust decisions in UAV imagery, fitting the edge-AI pattern where light SNNs regulate when more expensive processing or uplink is needed, while leaving more complex SNN detectors and surrogate-gradient training as future steps focused on accuracy improvements.

As summarized in Table 2, prior SNN edge work mainly optimizes computing or mapping in isolation, whereas our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to co-design and experimentally evaluate a 5G RedCap profile and a small SNN gate on a real UAV, relative to a standard 5G/ANN baseline.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of presented work to related works regarding SNNs and energy efficiency.

Given its low rust-detection accuracy (~26% vs. ~60% for the ANN), we primarily evaluate the SNN in terms of energy consumption. The sliding window approach allows the model to localize rust patches effectively, even in complex backgrounds. However, the model’s performance varies with the presence of significant background noise, indicating the need for further refinement. The use of SNNs for rust detection offers significantly lower power consumption than ANNs. The incorporation of image-processing techniques such as contour approximation and Hough Transform enhances the model’s robustness and accuracy. Future work could explore the integration of additional mathematical models like Fourier Transform and Wavelet Transform to further improve the detection capabilities.

3.3. Experimental Evaluation Results

The energy evaluation in this work consists of two complementary parts:

- (i)

- Device-level power measurements of the connectivity and edge-compute subsystem on the ground;

- (ii)

- System-level flight-time measurements on the UAV.

Device-level power. To quantify the impact of the proposed RedCap + SNN configuration on the on-board processing and communication stack, we measure the power consumption of the Jetson Orin and the 5G router from a controlled bench setup. Both devices are powered via a monitored smart plug DC supply, and the current and voltage are sampled continuously while the rust-detection pipeline is running, via a Python 3.4 based API. Each configuration—standard 5G NR + ANN and 5G RedCap + SNN—is executed for a sufficient warm-up period followed by a steady-state interval, during which we compute the average device-level power. These averages are used to derive the reported ≈60–65% power reduction (≈7 W) for the RedCap/SNN configuration.

System-level flight-time tests: To capture how the device-level savings translate into UAV endurance, a set of flights was performed per configuration on a 5G-equipped multirotor carrying the same payload (Teltonika 5G router + NVIDIA Jetson Orin) and the same rust-detection software stack. In each run, the UAV takes off with a fully charged battery, follows an identical low-altitude inspection path around the mast, and lands when the battery voltage reaches a predefined safety threshold in the flight controller. The total airborne time from take-off to landing is recorded as the flight duration. To minimize the impact of environmental factors, all flights considered in this study were conducted on the same day, within the same time window, in clear weather and low-wind conditions, and at low altitude. This ensures that illumination, temperature, and wind gusts are as similar as possible between the two configurations. For all experiments, the UAV (i) uses the same payload mass; (ii) follows the same mission profile (static waypoint, speed, and altitude); and (iii) operates with identical safety and landing criteria.

For each configuration, we report the mean flight time and standard deviation, alongside the bench-measured average device-level power.

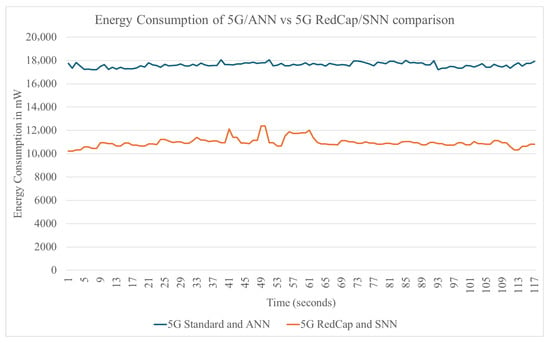

In Figure 1, the comparison between the standard 5G with an ANN setup and the 5G RedCap with an SNN one is presented in terms of the energy consumption for the same rust-detection scenario. Respectively, for each run, standard 5G and 5G RedCap were used simultaneously at full capacity, to benchmark the upper bound of each connectivity configuration. The results show a significant difference of ~7000 mW in energy saving for the 5G RedCap/SNN in comparison to the standard 5G/ANN setup. The difference percentage in energy saving was calculated to 65% overall, depicting the noteworthy efficiency for the first setup.

Figure 1.

Energy consumption graph of 5G/ANN vs. 5G RedCap/SNN comparison.

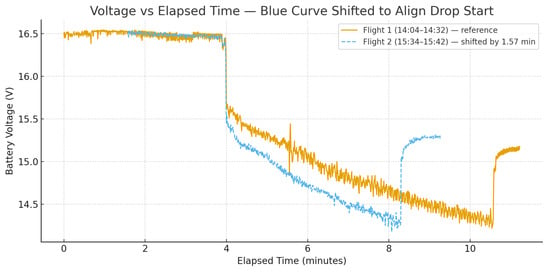

The experimental evaluation also measured the maximum bandwidth achieved with the standard 5G setup outperforming the 5G RedCap, 100 Mbps to 40 Mbps on average, showing a relative 50% difference. However, these evaluations do not directly translate into the system-level energy/endurance impact of the proposed setup in a real-time UAV-based experiment. Therefore, in Figure 2, the flight duration for both setups was measured, while each setup was installed on an actual drone for each run. For each run, the battery was fully charged at take-off, where the UAV is equipped with a Teltonika 5G Router (Teltonika Networks: Vilnius, Lithuania) and an NVIDIA Jetson Orin (NVIDIA: Santa Clara, CA, USA) to perform ANN and SNN, for each scenario, respectively. The battery charge is monitored during the entire duration of the flight, and the experiment is ended, once the battery voltage reaches a pre-defined lower point for the UAV to land safely.

Figure 2.

Experimental UAV setup with onboarded connectivity and processing modules, and snapshot during flights.

As shown in Figure 3, for the setup with the standard 5G/ANN, the flight duration is approximately 4 min, whereas the 5G RedCap/SNN one reached 6.5 min. This shows a flight time extension of around 35% for the 5G RedCap/SNN setup, highlighting how energy efficient RedCap with an SNN can prove to be for UAV-related operations. It is also important to note that the proposed work depicts how specific connectivity and edge processing enablers are translated in terms of energy efficiency in energy-constrained environments, also in relation with the entire operational system—in other words, how the 65% percentage of measured energy saving in the actual energy consumption of both setups translates to a 35% overall energy reduction in UAV flight time. It is an important notion to identify and quantify how different UAV connectivity and processing modules impact the battery life of a UAV.

Figure 3.

Flight duration comparison for configuration 1 (5G-ANN) and configuration 2 (5G RedCap-SNN), onboarded on drones.

From a practical perspective, the proposed RedCap + SNN stack is best viewed as an endurance-oriented operating mode for UAV inspections. When available, RedCap reduces the radio complexity and bandwidth, while the SNN gate lowers the compute and uplink duty cycle by filtering out uninformative patches. Together, these choices translate into ≈60–65% device-level power savings and a ≈35% longer flight time in our deployment, which can be valuable when the coverage is good and only coarse defect cues are needed on-board. However, the approach has several limitations. The SNN gate currently provides a modest detection accuracy and should be complemented by a higher-fidelity analysis either on the ground or in a more powerful edge/cloud node. The evaluation assumes the availability of a 5G RedCap-capable network with the tested configuration. In practice, operators will need to balance throughput, accuracy, and endurance when choosing between a standard 5G/ANN mode and a RedCap/SNN mode, depending on the mission requirements.

4. Conclusions

This work evaluated a unified approach for energy-aware UAV operations that combines 5G Reduced Capability (RedCap) for connectivity with SNNs for on-board inference. We implemented a 5G-equipped UAV prototype that integrates RedCap connectivity with an on-board Spiking Neural Network (784–1000–10 architecture) for rust/no-rust patch classification, benchmarked against a standard 5G NR + ANN baseline under the same inspection scenario. In a real deployment with a 5G-equipped UAV and edge processing on Jetson Orin, end-to-end measurements of the device-level power (router + Jetson Orin) on the bench and system-level flight time in real flights showed the integrated RedCap/SNN setup cut the device-level power draw by about 60–65% (≈7 W reduction) relative to a baseline of the standard 5G with an ANN, and translated this saving into roughly a 35% increase in flight time, demonstrating that targeted choices in both radio and compute stacks can yield system-level benefits in energy-limited environments. Beyond energy, the experiments highlight the practical trade-off between throughput and autonomy: while the standard 5G achieved a higher bandwidth (≈100 Mbps vs. ≈40 Mbps for RedCap), the RedCap/SNN configuration delivered materially longer airtime, which is often the binding constraint for battery-limited UAV missions. These findings suggest that, for edge workloads with moderate data-rate needs, prioritizing RedCap features and event-driven SNN inference can unlock better endurance without sacrificing task effectiveness.

Additionally, the study followed the motivation set in the introduction—addressing the limits of AI/ML on energy-constrained edge devices and the need for more efficient connectivity—by validating a dual optimization path across the RAN and the on-board AI stack. To enable replication and deeper understanding, we provided a side-by-side configuration analysis of standard 5G NR and RedCap parameters (bandwidth parts, duplexing, MCS limits, and signaling differences), discussing how each affects the device complexity and energy consumption. The lightweight SNN gate designed for this inspection workload demonstrates the feasibility of event-driven, sparse computation for patch-level detection within a sliding-window pipeline, with the associated accuracy–energy trade-offs explicitly evaluated against conventional ANN approaches. The results provide initial evidence that aligning RedCap’s narrow-band operation and power-saving mechanisms with the sparse, asynchronous nature of SNN processing is a viable route to energy-efficient edge intelligence in UAVs.

For future next steps, the work will cover, firstly, the evaluation on broader trials across tasks, and platforms are needed to generalize the gains. Secondly, while we quantified the end-to-end effects (device power and flight time), a deeper analysis of specific RedCap parameters and SNN design choices would clarify where the largest marginal savings occur.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.K.; methodology, M.A.K.; software, A.O., A.E., G.K. and A.V.; validation, M.C.B.; formal analysis, G.X.; investigation, P.T.; resources, M.A.K.; data curation, G.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.K.; writing—review and editing, M.A.K.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, G.X. and P.T.; project administration, M.A.K.; funding acquisition, M.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Autonomous Programmable Cloud Apps and Smart Sensors (OASEES) Project (Grant Number: 101092702).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in ZENODO at https://zenodo.org/records/17533667 (accessed on 2 November 2025) and https://zenodo.org/records/16679950 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3GPP | 3rd-Generation Partnership Project |

| 5G NR | 5th-Generation New Radio |

| 6G | Sixth-Generation (future mobile networks) |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARFCN | Absolute Radio-Frequency Channel Number |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| BWP | Bandwidth Part |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DVFS | Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling |

| eDRX | Extended Discontinuous Reception |

| eMBB | Enhanced Mobile Broadband |

| FDD | Frequency-Division Duplex |

| FR1 | Frequency Range 1 (sub-6 GHz) |

| FR2 | Frequency Range 2 (mmWave) |

| gNB | Next-generation NodeB (5G base station) |

| GOPS | Giga Operations Per Second |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HD-FDD | Half-Duplex FDD |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| MIMO | Multiple-Input Multiple-Output |

| mW | milliwatt |

| NPU | Neural Processing Unit |

| NR | New Radio (5G air interface) |

| OASEES | Open Autonomous Programmable Cloud Apps and Smart Sensors (Project) |

| OFDM | Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing |

| PRACH | Physical Random Access Channel |

| PRB | Physical Resource Block |

| PDSCH | Physical Downlink Shared Channel |

| PUCCH | Physical Uplink Control Channel |

| PUSCH | Physical Uplink Shared Channel |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| QUBO | Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization |

| RAN | Radio Access Network |

| RCM | RedCap-only (context: restricted operation on specific BWPs) |

| RedCap | Reduced Capability (5G NR device/profile) |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RRC | Radio Resource Control |

| RRM | Radio Resource Management |

| SIB1 | System Information Block Type 1 |

| SISO | Single-Input Single-Output |

| SLTT | Spatial Learning Through Time |

| SNN | Spiking Neural Network |

| SSB | Synchronization Signal Block |

| STDP | Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity |

| TDD | Time-Division Duplex |

| TOPS | Tera Operations Per Second |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit |

| UCI | Uplink Control Information |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

References

- Abrar, M.; Ajmal, U.; Almohaimeed, Z.M.; Gui, X.; Akram, R.; Masroor, R. Energy Efficient UAV-Enabled Mobile Edge Computing for IoT Devices: A Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 127779–127798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheralieva, A.; Niyato, D. Effective UAV-Aided Asynchronous Decentralized Federated Learning with Distributed, Adaptive and Energy-Aware Gradient Sparsification. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 27461–27480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP. A Glimpse into RedCap NR Devices. 3rd Generation Partnership Project. 2022. Available online: https://www.3gpp.org/technologies/nr-redcap-glimpse (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ericsson. What Is Reduced Capability (RedCap) NR? Ericsson Technology Blog. 2021. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2021/2/reduced-cap-nr (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ericsson. RedCap: Expanding the 5G Device Ecosystem for Consumers and Industries. White Paper. 2023. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/493d70/assets/local/reports-papers/white-papers/redcap-5g-iot-for-wearables-and-industries.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Kufel, J.; Bargieł-Łączek, K.; Kocot, S.; Koźlik, M.; Bartnikowska, W.; Janik, M.; Czogalik, Ł.; Dudek, P.; Magiera, M.; Lis, A.; et al. What Is Machine Learning, Artificial Neural Networks and Deep Learning?—Examples of Practical Applications in Medicine. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Yu, D.; Lv, C.; Du, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, X.; Tong, W.; Zheng, X.; Fang, W.; Zhao, P.; et al. Edge Intelligence with Spiking Neural Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baller, S.P.; Jindal, A.; Chadha, M.; Gerndt, M. DeepEdgeBench: Benchmarking Deep Neural Networks on Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–8 October 2021; pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- u-blox. 5G RedCap, Completing the 3GPP Puzzle and Beyond. u-blox IoT Insights. 2023. Available online: https://www.u-blox.com/en/blogs/insights/5g-redcap (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Richardson RFPD. 5G RedCap: An Essential Technology for IoT. Technical Article. 2024. Available online: https://shop.richardsonrfpd.com/docs/rfpd/RRFPD-5G-RedCap-An-Essential-Technology-for-IoT-2024-08.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Telenor IoT. 5G RedCap for IoT: The Perfect Balance of 5G Capabilities. Telenor IoT. 2024. Available online: https://iot.telenor.com/technologies/connectivity/5g-redcap (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ericsson. RedCap/eRedCap—Standardizing Simplified 5G IoT Devices. Ericsson Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2024/12/redcap-eredcap (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- ABI Research. 5G RedCap: Simplifying Cellular Connectivity for IoT Devices. ABI Research Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.abiresearch.com/blog/5g-redcap (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Yan, Z.; Bai, Z.; Wong, W.-F. Reconsidering the Energy Efficiency of Spiking Neural Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.08290. [Google Scholar]

- Yik, J.; Van den Berghe, K.; den Blanken, D.; Bouhadjar, Y.; Fabre, M.; Hueber, P.; Ke, W.; Khoei, M.A.; Kleyko, D.; Pacik-Nelson, N.; et al. The NeuroBench Framework for Benchmarking Neuromorphic Computing Algorithms and Systems. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intel. Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering with AI. Intel Research. 2024. Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/research/neuromorphic-computing.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Davies, M.; Srinivasa, N.; Lin, T.-H.; Chinya, G.; Cao, Y.; Choday, S.H.; Dimou, G.; Joshi, P.; Imam, N.; Jain, S.; et al. Loihi: A Neuromorphic Manycore Processor with On-Chip Learning. IEEE Micro 2018, 38, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Neuromorphic. A Look at Loihi—Intel Neuromorphic Chip. Open Neuromorphic. 2023. Available online: https://open-neuromorphic.org/neuromorphic-computing/hardware/loihi-intel (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Open Neuromorphic. A Look at Loihi 2—Intel Neuromorphic Chip. Open Neuromorphic. 2024. Available online: https://open-neuromorphic.org/neuromorphic-computing/hardware/loihi-2-intel (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Intel Corporation. Intel Builds World’s Largest Neuromorphic System to Enable More Sustainable AI. Intel Newsroom, 17 April 2024. Available online: https://newsroom.intel.com/artificial-intelligence/intel-builds-worlds-largest-neuromorphic-system-to-enable-more-sustainable-ai (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Neftci, E.O.; Mostafa, H.; Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, B.; Stradmann, Y.; Schemmel, J.; Zenke, F. A surrogate gradient spiking baseline for speech command recognition. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 865897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhan, L.T.; Duong, L.T.; Nam, P.N.; Thang, T.C. Accuracy–Robustness Trade Off via Spiking Neural Network Gradient Sparsity Trail. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23762. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2509.23762 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Hu, W.-X.; He, Y.-L.; Huang, J.Z. A Comprehensive Multimodal Benchmark of Neuromorphic Training Frameworks for Spiking Neural Networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 159, 111543. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0952197625015453 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Rajendran, B.; Sebastian, A.; Schmuker, M.; Srinivasa, N.; Eleftheriou, E. Low-Power Neuromorphic Hardware for Signal Processing Applications. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03690. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.03690 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Yu, D.; Du, X.; Jiang, L.; Tong, W.; Deng, S. EC-SNN: Splitting Deep Spiking Neural Networks for Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2024), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–9 August 2024; Available online: https://www.ijcai.org/proceedings/2024/596 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, G.Y. Energy-Efficient Distributed Spiking Neural Network for Wireless Edge Intelligence. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 10683–10697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, T.; Perera, I. Optimizing Energy Efficient Cloud Architectures for Edge Computing: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, H.; Chen, S.; Feng, X. Energy efficient task scheduling for heterogeneous multicore processors in edge computing. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Wang, H.; Lin, M. Energy-Efficient Computation with DVFS Using Deep Reinforcement Learning for Multi-Task Systems in Edge Computing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19434. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2409.19434v3 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Viso.ai. AI Hardware: Edge Machine Learning Inference Accelerators Overview. Viso Blog. 2024. Available online: https://viso.ai/edge-ai/ai-hardware-accelerators-overview (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Jaycon Systems. Top 10 Edge AI Hardware for 2025. Jaycon Blog. 2025. Available online: https://www.jaycon.com/top-10-edge-ai-hardware-for-2025 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Renesas. Enable High Performance, Low Power Inference in Your Edge AI Applications. Renesas Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.renesas.com/en/blogs/enable-high-performance-low-power-inference-your-edge-ai-applications (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Musa, A.; Kakudi, H.A.; Hassan, M.; Hamada, M.; Umar, U.; Salisu, M.L. Lightweight Deep Learning Models for Edge Devices—A Review. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. Ind. Manag. Appl. 2024, 17, 189–206. Available online: https://cspub-ijcisim.org/index.php/ijcisim/article/download/1025/635/1787 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, G.Y. SpikACom: A Neuromorphic Computing Framework for Green Communications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17168. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.17168 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Yang, H.; Lam, K.-Y.; Xiao, L.; Xiong, Z.; Hu, H.; Niyato, D.; Poor, H.V. Lead federated neuromorphic learning for wireless edge artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X. Edge AI: On-Demand Accelerating Deep Neural Network Inference via Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 19, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassi, A.; Kolawole, O.Y.; Roig, J.P.; Warren, D. Optimized Split Computing Framework for Edge and Core Devices. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.06049. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2509.06049 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Analog Devices. Driving 5G Energy Efficiency with Edge AI and Digital Predistortion. Analog Devices Signals+ Articles. 2024. Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/signals/articles/5g-energy-efficiency-with-edge-ai.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Gotthans, T.; Baudoin, G.; Mbaye, A. Digital predistortion with advance/delay neural network and comparison with Volterra derived models. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 25th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communication (PIMRC), Washington, DC, USA, 2–5 September 2014; pp. 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AT&T. AT&T Hits Another U.S. Industry-First: 5G RedCap Data Connection. AT&T Newsroom. 2023. Available online: https://about.att.com/blogs/2023/5g-redcap.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Li, W.; Zhao, J.; Su, L.; Jiang, N.; Hu, Q. Spiking Neural Networks for Object Detection Based on Integrating Neuronal Variants and Self-Attention Mechanisms. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Asunción, S.; Ituero, P. Enabling Efficient On-Edge Spiking Neural Network Acceleration with Highly Flexible FPGA Architectures. Electronics 2024, 13, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Xie, L.; Chen, F.; Wu, L.; Tian, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ying, R.; Liu, P. EdgeMap: An Optimized Mapping Toolchain for Spiking Neural Network in Edge Computing. Sensors 2023, 23, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.