Abstract

Background: Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) incidence is rising, particularly among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA, 15–39 years). However, data on PTC characteristics in the AYA population, especially from the Middle East, remain limited. This study aims to describe the clinicopathological features of PTC in AYA patients treated at a large tertiary center in Qatar. Methods: A retrospective chart review was conducted for AYA patients diagnosed with PTC between May 2015 and December 2020 at Hamad General Hospital, Qatar. Data on demographics, tumor characteristics, histopathology, staging, risk stratification, and treatment were extracted and analyzed. We stratified the cohort based on sex. Results: We studied 326 AYA patients (mean age 33.0 ± 5.2 years); the majority were females (72.7%) and were mostly of Asian origin (51.5%). Most patients underwent total thyroidectomy (77.6%), while 22.4% underwent partial thyroidectomy. Histologically, classic PTC was most common (83.38%), followed by the follicular variant (16.00%). Capsule invasion occurred in 21.04%, vascular invasion in 11.76%, and lymphatic invasion in 14.38%. Most patients were at low ATA risk (68.61%), with intermediate (20.06%) and high risk (11.33%) less common. Distant metastases were rare (0.3%), and 59.1% received Radioactive iodine (RAI). Compared to females, males had larger tumors (mean 2.65 cm vs. 2.01 cm, p = 0.0009), higher rates of vascular invasion (22.4% vs. 7.7%, p < 0.001), affected lymph nodes (mean 4.2 vs. 2.4, p = 0.0223), and ATA high-risk proportions (23.5% vs. 7.0%, p < 0.001). Conclusions: This study provides the first detailed characterization of PTC in AYA patients from Qatar. While confirming female predominance, males exhibited more aggressive features (larger tumors, higher LN involvement, and ATA risk). These findings emphasize the need to consider gender-specific differences in managing PTC within the AYA population.

1. Introduction

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is the predominant histological subtype of thyroid malignancies, with follicular and medullary thyroid cancers occurring less frequently [1,2,3]. The incidence of thyroid cancer, particularly PTC, has increased over the last few decades [4]. This increase is largely attributed to the enhanced detection of often asymptomatic, small thyroid nodules through the widespread use of neck ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) techniques [5]. Despite the rising incidence rates of PTC, the associated mortality rates remain relatively low [6]. Indeed, a large USA cohort study of 91,986 patients showed that while the incidence of PTC increased from 5.0 per 100,000 in 1975 to 14.6 per 100,000 in 2009, mortality rates remained unchanged [7].

The overdiagnosis of low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) highlights the need for effective risk stratification tools. Several factors have been identified as indicators of a poorer prognosis, including age > 55 years at diagnosis, male gender, large primary tumor size (>4 cm), specific aggressive histological variants, advanced disease stage at presentation, presence of extrathyroidal extension, lymphatic invasion, absence of appropriate surgical or radiation treatment, and the occurrence of distant metastases [8,9].

While the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) AYA designation (ages 15–39) is often used to highlight biologically unique cancers in young people, for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (PTC), this age range encompasses a large proportion of typical cases, as over 30% of PTCs occur in this demographic [10]. Our study utilizes this standard classification not to suggest a unique biological entity, but to provide a detailed clinicopathological profile of PTC within this significant patient population in Qatar, a region where such high-quality data has been lacking. Within this demographic, thyroid cancer ranks as the fifth most common malignancy, predominantly driven by the high incidence of PTC [11]. Notably, thyroid cancer exhibits a marked gender disparity, being approximately three times more prevalent in women compared to men [12]. While extensive research exists on PTC in the general adult population, studies specifically focusing on the AYA cohort are comparatively scarce. The standard treatment approach for PTC typically involves surgical resection, primarily total or near-total thyroidectomy, often followed by radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation [13], particularly for patients classified as having intermediate or high risk of disease recurrence based on clinicopathological features [14,15]. Existing literature from the Middle East on papillary thyroid cancer, particularly in the AYA population, is limited. Studies from the region have primarily focused on adult populations or have been limited in scope. For instance, a study from Saudi Arabia reported on the clinicopathological features of thyroid cancer but did not specifically focus on the AYA cohort or gender-based differences [16,17,18,19]. This scarcity of regional data underscores the importance of studies like ours in providing context-specific insights into PTC characteristics.

This study aims to investigate the incidence and delineate the general characteristics of PTC within the AYA population in Qatar. Furthermore, it seeks to explore potential associations between patient age, gender, ethnicity, and various clinicopathological features. Given the limited availability of data regarding PTC profiles in Qatar, especially within the AYA age group, this research is anticipated to contribute to a better understanding of the disease characteristics within this unique and diverse population. The study’s relevance is underscored by Qatar’s demographic composition, where the younger population constitutes a substantial portion of the workforce.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This is a retrospective study that was conducted at Hamad General Hospital, a major tertiary care center and member of the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) in Doha, Qatar. The research focused on analyzing existing medical records of patients diagnosed and/or treated for Papillary Thyroid Cancer (PTC) within the specified timeframe.

2.2. Study Population

We included all patients aged 15 to 39 years (inclusive) at the time of PTC diagnosis, identified between 1 May 2015, and 31 December 2020. This age range aligns with the definition of Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Diagnosis could have been established either through fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology or histopathological examination of surgical biopsy specimens. Patients diagnosed outside of Qatar, either by FNA or surgery, were excluded from the study to ensure the cohort represented cases managed within the local healthcare system.

Cases that were reclassified as Non-Invasive Follicular Thyroid Neoplasm with Papillary-like Nuclear Features (NIFTP) upon pathological review were excluded from this analysis to ensure the cohort consisted strictly of malignant PTC.

For the purposes of this study, the “Qatari” group includes citizens of Qatar, whereas the “Arab” group consists of non-Qatari Arab nationals residing in the country.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

We used the electronic medical records (Cerner Millennium) to extract the data. We used a standardized data collection sheet. We collected data on demographics, modality of diagnosis, surgical procedure, histopathological tumor characteristics, TNM staging, and adjuvant radioactive iodine therapy. Risk stratification for disease recurrence was performed according to the American Thyroid Association (ATA) 2015 guidelines, based on histopathological features, and patients were categorized into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk groups accordingly [20]. Data on extrathyroidal extension (ETE) did not differentiate between microscopic and gross extension.

Because the proportion of missing data in our dataset was very small, we did not apply imputation or other statistical techniques to replace missing values. We analyzed only cases with complete data for the variables of interest (complete-case analysis, listwise deletion), and the denominators used for each analysis are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analysis using STATA 15. We summarized continuous variables as the means ± SD or medians (IQR) as appropriate. We summarized categorical variables as percentages. We used an unpaired t-test and Man-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables as appropriate. Chi-square and Fisher’s tests were used to compare categorical variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 326 patients diagnosed with Papillary Thyroid Cancer (PTC) between the ages of 15 and 39 years were included. As shown in Table 1, the mean age at diagnosis was 32.98 ± 5.19 years. Most of the cohort was females (n = 237, 72.70%), and were predominantly Asian (n = 168, 51.53%), followed by Arabs (n = 98, 30.06%), Qataris (n = 46, 14.11%), and others (n = 14, 4.29%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Adolescents and Young Adults with Papillary Thyroid Cancer.

As shown in Table 2, PTC diagnosis was established via Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) cytology in most cases (n = 204, 62.96%) and most patients were treated with total thyroidectomy (n = 253, 77.61%), and most tumours were unifocal (n = 183 cases, 56.13%). The most common tumor site was the right lobe (n = 162, 52.09%), followed by the left lobe (n = 133, 42.77%) and the isthmus (n = 16, 5.14%). The mean tumor size was 2.19 ± 1.58 cm. The predominant histological subtype was classic Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (PTC) (n = 271, 83.38%), followed by the Follicular variant (n = 52, 16.00%) and the tall cell variant (n = 2, 0.62%). The remaining case was another rare PTC subtype. Invasion of the tumor capsule was reported in 65 cases (21.04%); vascular invasion was present in 36 cases (11.76%); lymphatic invasion was observed in 44 cases (14.38%); perineural invasion was rare (n = 7, 2.23%); while extrathyroidal extension was reported in 13 cases (4.47%).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Papillary Thyroid Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults by Gender.

Among the 300 patients with available data on lymph node involvement, the median number of positive lymph nodes was 0 (IQR: 0–4). The median number of resected lymph nodes was 1 (IQR: 0–6). For the 69 patients with available measurements, the median size of the largest metastatic lymph node was 1.3 cm (IQR: 0.4–2.5 cm) (Table 2).

Based on the available TNM staging data, most patients presented with T1 or T2 tumors (T1a: 25.85%, T1b: 21.85%, T2: 27.38%). The T3 classification (T3a and T3b, totaling 18.76%) was predominantly attributed to tumor size greater than 4 cm confined to the thyroid, rather than gross extrathyroidal extension. Nodal status was often undetermined (Nx: 46.30%), followed by N0 (24.69%). Distant metastases (M1) were extremely rare, observed in only one patient (0.31%). Consequently, almost all patients (99.69%) were classified as TNM Stage. As shown in Table 3; lymph node metastasis was significantly more common in males, with a higher median affected nodes compared to females (0.5 (IQR 0–7) vs. 0 (IQR (0–3); p = 0.0364) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lymph Node Involvement, TNM Staging, and Risk Stratification in Adolescents and Young Adults with Papillary Thyroid Cancer.

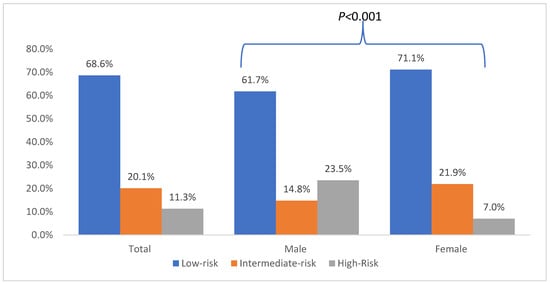

Data on RAI therapy were available for 286 patients. A total of 117 patients (40.91%) did not receive RAI. Among those treated, the majority received one session (n = 84, 29.37%). The median number of RAI sessions was 1 (IQR: 0–2). For the 168 patients with available activity information, the median cumulative RAI activity was 60 mCi (IQR: 31.6–103.95 mCi) (Table 4). According to the ATA initial risk stratification system for disease recurrence, 68.61% of patients were classified as Low risk, 20.06% as Intermediate risk, and 11.33% as High risk Figure 1.

Table 4.

Radioactive Iodine (RAI) Therapy Characteristics.

Figure 1.

American Thyroid Association (ATA) Risk Stratification of Adolescents and Young Adults with Papillary Thyroid Cancer.

As shown in Table 2, compared to females, males had larger tumors (mean size: 2.65 ± 1.80 cm vs. 2.01 ± 1.45 cm; p = 0.0009); and were more likely to have vascular invasion (22.4% vs. 7.7%, <0.001). Lastly, as shown in Figure 1, males were more likely to have high ATA risk at diagnosis compared to females (23.5% vs. 7.0%; p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study provides the first detailed description of the clinicopathological characteristics of Papillary Thyroid Cancer (PTC) among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA), defined as individuals aged 15–39 years, within a large tertiary care center in Qatar. Our findings reveal several notable features of PTC in this specific demographic within our population, contributing valuable data to a field where information, particularly from the Middle East region, remains relatively limited.

The mean age at diagnosis in our AYA cohort was approximately 33 years, with a significant majority (75.2%) being 30–39 years old. This aligns with the general understanding that while thyroid cancer can occur in younger individuals, its incidence tends to increase with age even within the AYA bracket [21]. Consistent with global trends [22], we observed a striking female predominance (72.70%), reinforcing the known gender disparity in thyroid cancer incidence. The ethnic distribution, with Asians comprising the largest group followed by Arabs and Qataris, reflects the diverse demographic makeup of Qatar. The observed significant association between gender and ethnicity warrants further investigation but might reflect underlying genetic, environmental, or healthcare access differences among ethnic groups within the country. Future studies should also consider the influence of behavioral factors, such as dietary habits, food preparation methods, and environmental exposures, which may contribute to the observed associations between gender, ethnicity, and PTC characteristics.

FNA cytology was the primary diagnostic method of PTC, consistent with standard clinical practice [23]. Total thyroidectomy was the most performed surgery in over three-quarters of the patients, reflecting the common approach for managing PTC within the time range of recently published guidelines at that time, even in younger patients, particularly when considering factors like multifocality or higher-risk features [24,25]. The lack of significant gender differences in diagnostic modality or surgical approach suggests standardized management pathways.

Perhaps one of the most significant findings relates to tumor characteristics and gender differences. While tumor focality and site distribution were largely comparable between genders and consistent with general PTC patterns, males in our AYA cohort presented with significantly larger primary tumors compared to females. This finding is concerning as larger tumor size is a known adverse prognostic factor [26,27,28]. Furthermore, males exhibited a significantly higher rate of vascular invasion and a greater number of affected lymph nodes. This combination suggests that PTC may manifest with more aggressive features in young adult males compared to their female counterparts in this population. Our observations are consistent with a growing body of evidence. For instance, Zhu et al. [29] reported that male gender was an independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis, and Remer et al. [30] found that male patients presented with higher rates of both lympho-vascular invasion and positive lymph nodes. These findings, along with other studies identifying male sex as an independent poor prognostic factor [31,32] reinforce the clinical significance of our results and underscore the need for gender-specific considerations in risk stratification [33,34].

The prevalence of nodal involvement, particularly the higher mean number of affected nodes in males, further supports the notion of potentially more aggressive disease in young men within this cohort. Although nodal metastases are common in PTC, especially in younger patients, its extent can influence risk stratification and treatment decisions [35,36]. This high proportion of Nx cases is a limitation of our retrospective study, reflecting potential documentation gaps or variations in initial lymph node evaluation. While it impacts the precision of staging, the available data still provide valuable insights into the overall clinicopathological features of PTC in our cohort. We acknowledge that comprehensive and standardized reporting of nodal status is crucial for accurate staging and future research.

Despite the presence of some potentially more aggressive features, particularly in males, the overall prognostic outlook appeared favorable for the majority of the cohort, with nearly all patients classified as TNM Stage I. This aligns with the generally excellent survival rates reported for PTC, especially in younger age groups [36]. An important finding from our staging data is that the majority of T3 cases were classified based on large tumor size (>4 cm) rather than gross extrathyroidal extension. This suggests that a notable proportion of young patients in our cohort present with large but still localized tumors, which has important implications for surgical planning and risk stratification. The ATA risk stratification for disease recurrence showed a predominance of Low-risk disease (68.61%), followed by Intermediate (20.06%) and High risk (11.33%). This distribution guided subsequent management, including the use of RAI therapy. Notably, 40.91% of patients did not receive RAI, likely representing the Low-risk group for whom adjuvant therapy is often not recommended under current guidelines [35,36,37]. For those treated, one session was the most common regimen.

This study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective design. A significant limitation is the study’s descriptive nature and the absence of a non-AYA comparator group, which precludes a more powerful analysis of age-specific differences in PTC characteristics. Specifically, data on several important variables were not systematically collected, including key risk factors for thyroid cancer (such as radiation exposure or family history), prior personal history of benign thyroid disorders, and the preceding Bethesda categories for FNA cytology. Furthermore, our analysis did not extend to long-term management details, such as thyroid hormone suppressive therapy or the side effects of RAI treatment. The study was also conducted at a single center, which, although large, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Calculation of true incidence rates was not possible without access to national population denominator data. Another limitation of this retrospective study is the absence of long-term follow-up data, including recurrence, disease-free survival, or overall survival. Furthermore, this study did not include mortality data, which would be necessary to answer important questions about trends in the age of death from PTC and the potential influence of environmental factors. This represents an important area for future prospective research.

A key limitation of our study is the lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors that may influence the observed relationship between gender and certain outcomes. Future research with larger datasets is warranted to enable comprehensive sensitivity analyses and more robust control of confounding variables.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into PTC characteristics in the AYA population in Qatar. The findings highlight a significant female predominance but suggest potentially more aggressive tumor features (larger size, vascular invasion, nodal involvement) in young adult males. Most patients present with early-stage disease and fall into the Low or Intermediate ATA risk categories for disease recurrence. Future research should focus on prospective data collection, including long-term follow-up, to better understand recurrence patterns and survival outcomes in this population. Investigating the underlying reasons for the observed gender differences in tumor aggressiveness and exploring the impact of ethnicity would also be valuable avenues for future studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides the first comprehensive analysis of Papillary Thyroid Cancer characteristics among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) in Qatar. Our findings confirm a significant female predominance, consistent with global patterns. However, we identified potentially more aggressive disease features in young adult males within this cohort, characterized by larger tumor sizes, higher rates of vascular invasion, and more extensive lymph node involvement at presentation. Despite these observations, the majority of AYA patients presented with early-stage disease with mostly low risk for disease recurrence. These findings underscore the importance of considering gender-specific differences in the clinical presentation and management of PTC within the AYA population. Further prospective studies with long-term follow-up are warranted to validate these findings and elucidate the long-term outcomes for AYA patients with PTC in Qatar.

6. Recommendations

Given the more aggressive disease features observed in male AYA patients—such as larger tumors, increased lymph node involvement, and higher ATA risk—there is a clear need to incorporate gender-specific considerations into the risk stratification and management of PTC to optimize outcomes. In addition, long-term prospective studies are essential to better understand recurrence patterns, disease-free survival, and overall survival, thereby enabling a more comprehensive assessment of prognostic factors and treatment efficacy. Furthermore, exploring the role of ethnicity in PTC characteristics and outcomes, particularly in diverse populations like those in Qatar, may help identify population-specific risk factors and care disparities, ultimately supporting the development of more personalized and equitable approaches to treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/endocrines7010002/s1, File S1: Complete Statistical Analysis Output; File S2: Denominators and Missing Data for All Variables.

Author Contributions

E.A.A., Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. M.A., Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. M.B., Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. T.J., Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. D.A.-M., Reviewing draft, finalizing the manuscript. S.F.M., Project administration, data review, and review and editing of the manuscript. N.E., A.E.O., R.A.-S., R.B. and M.F.E., Data collection, validation, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no external financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The open access publication costs were self-funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional review board (IRB) of Hamad medical corporation (Approval code: MRC-01-22-611, Approval date: 1 March 2023). The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, and the local laws and regulations of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) in Qatar. Due to the study’s retrospective design, informed consent was waived by the Medical Research Centre (MRC) at Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar.

Informed Consent Statement

As a retrospective chart review, the IRB granted a waiver of informed consent in line with institutional policy, given the minimal risk and use of existing data.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

References

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.; Welch, H.G. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 295, 2164–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekimsoy, İ.; Ertan, Y.; Serin, G.; Karabulut, A.K.; Özbek, S.S. Comparison of ultrasound findings of papillary thyroid carcinoma subtypes based on the 2022 WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1434787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Du, X.L.; Reitzel, L.R.; Xu, L.; Sturgis, E.M. Impact of enhanced detection on the increase in thyroid cancer incidence in the United States: Review of incidence trends by socioeconomic status within the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry, 1980–2008. Thyroid 2013, 23, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, J.P.; Davies, L. Is there really an increased incidence of thyroid cancer? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2014, 21, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vecchia, C.; Malvezzi, M.; Bosetti, C.; Garavello, W.; Bertuccio, P.; Levi, F.; Negri, E. Thyroid cancer mortality and incidence: A global overview. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 2187–2195. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25284703/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.M.; Luu, M.; Sacks, W.L.; Orloff, L.; Wallner, L.P.; Clair, J.M.S.; Pitt, S.C.; Ho, A.S.; Zumsteg, Z.S. Trends in incidence, metastasis, and mortality from thyroid cancer in the USA from 1975 to 2019: A population-based study of age, period, and cohort effects. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 188–195. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39922210/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.S.; Yoon, J.H.; Park, M.H.; Shin, S.H.; Jegal, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.K. Age and prognosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Retrospective stratification into three groups. J. Korean Surg. Soc. 2012, 83, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, R.M.; Haugen, B.; Perrier, N.D. Updated American Joint Committee on Cancer/Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System for Differentiated and Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer (Eighth Edition): What Changed and Why? Thyroid 2017, 27, 751–756. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5467103/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tricoli, J.V.; Bleyer, A. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Biology. Cancer J. 2018, 24, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mosha, S.S.; Zhang, T.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liang, W.; Deng, X.; Ou, T.; Li, L.; et al. Incidence of microcarcinoma and non-microcarcinoma in ultrasound-found thyroid nodules. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021, 21, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbari, R.; Zhang, L.; Kebebew, E. Thyroid cancer gender disparity. Future Oncol. 2010, 6, 1771–1779. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21142662/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.A.; Pura, J.; Goffredo, P.; Dinan, M.A.; Reed, S.D.; Scheri, R.P.; Hyslop, T.; Roman, S.A.; Sosa, J.A. Presence and number of lymph node metastases are associated with compromised survival for patients younger than age 45 years with papillary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2370–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilubol, N.; Zhang, L.; Kebebew, E. Multivariate analysis of the relationship between male sex, disease-specific survival, and features of tumor aggressiveness in thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin. Thyroid 2013, 23, 695–702. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23194434/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Loh, K.C.; Greenspan, F.S.; Gee, L.; Miller, T.R.; Yeo, P.P.B. Pathological tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) staging for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas: A retrospective analysis of 700 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 3553–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, W.S.; Almufareh, N.A.; Domiaty, D.M.; Albasher, G.; Alduwish, M.A.; Alkhalaf, H.; Almuzzaini, B.; Al-Marshidy, S.S.; Alfraihi, R.; Elasbali, A.M.; et al. Epidemiology of cancer in Saudi Arabia thru 2010–2019: A systematic review with constrained meta-analysis. AIMS Public Health 2020, 7, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemban, A.F.; Kabrah, S.; Alahmadi, H.; Alqurashi, R.K.; Turaes, A.S.; Almaghrabi, R.; Al Harbi, S.; Khogeer, A.A. Patterns of Thyroid Cancer Mortality and Incidence in Saudi Arabia: A 30-Year Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2716. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9689402/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, A.S.; Alomar, H.; Alzahrani, N. Thyroid Cancer in Saudi Arabia: A Histopathological and Outcome Study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 8423147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hakami, H.A.; Alqahtani, R.; Alahmadi, A.; Almutairi, D.; Algarni, M.; Alandejani, T. Thyroid Nodule Size and Prediction of Cancer: A Study at Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2020, 12, e7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battistella, E.; Pomba, L.; Toniato, R.; Piotto, A.; Toniato, A. Total Thyroidectomy vs. Lobectomy in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: A Contested Gold Standard. J. Pers Med. 2025, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.H.H.; Lo, C.Y.; Chan, W.F.; Lam, K.Y.; Wan, K.Y. Prognostic factors in papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: Their implications for cancer staging. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 730–738. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17103065/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cerfolio, R.J.; Bryant, A.S.; Scott, E.; Sharma, M.; Robert, F.; Spencer, S.A.; Garver, R.I. Women with pathologic stage I, II, and III non-small cell lung cancer have better survival than men. Chest 2006, 130, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twining, C.L.; Lupo, M.A.; Tuttle, R.M. Implementing key changes in the American thyroid association 2015 thyroid nodules/differentiated thyroid cancer guidelines across practice types. Endocr. Pract. 2018, 24, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.L.; Waguespack, S.G.; Bauer, A.J.; Angelos, P.; Benvenga, S.; Cerutti, J.M.; Dinauer, C.A.; Hamilton, J.; Hay, I.D.; Luster, M.; et al. Management Guidelines for Children with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2015, 25, 716–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26462967/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rosario, P.W.; da Silva, A.L.; Nunes, M.S.; Ribeiro Borges, M.A.; Mourão, G.F.; Calsolari, M.R. Risk of malignancy in 1502 solid thyroid nodules > 1 cm using the new ultrasonographic classification of the American Thyroid Association. Endocrine 2017, 56, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.A.; Yen, T.W.F.; Ortiz, D.I.; Hunt, B.C.; Fareau, G.; Massey, B.L.; Campbell, B.H.; Doffek, K.L.; Evans, D.B.; Wang, T.S. Patients with oncocytic variant papillary thyroid carcinoma have a similar prognosis to matched classical papillary thyroid carcinoma controls. Thyroid 2018, 28, 1462–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.W.; Son, S.H.; Hong, C.M.; Jeong, J.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Ahn, B.-C.; Lee, J. Prognostic value of lymph node uptake on pretreatment F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with N1b papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr. Pract. 2019, 25, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Shi, B.Y. Prognostic Factors for Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma and Review of the Literature. Tumori J. 2012, 98, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Thyroid Association Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid; Cooper, D.S.; Doherty, G.M.; Haugen, B.R.; Kloos, R.T.; Lee, S.L.; Mandel, S.J.; Mazzaferri, E.L.; McIver, B.; Pacini, F.; et al. Revised American thyroid association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2009, 19, 1167–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yan, C.; Wei, H.; Lv, Y.; Ling, R. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of thyroid cancer in northwest China: A population-based retrospective study of 2490 patients. Thorac. Cancer 2018, 9, 1453–1460. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6209792/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in Shanghai, China, 1983–2007. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP223–NP229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the united states. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trésallet, C.; Seman, M.; Tissier, F.; Buffet, C.; Lupinacci, R.M.; Vuarnesson, H.; Leenhardt, L.; Menegaux, F. The incidence of papillary thyroid carcinoma and outcomes in operative patients according to their body mass indices. Surgery 2014, 156, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.; Lee, S.; Bae, J.S. Risk factors associated with high-risk nodal disease in patients considered for active surveillance of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma without extrathyroidal extension. Gland Surg. 2023, 12, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Ganly, I. Nodal metastases in thyroid cancer: Prognostic implications and management. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 981–994, Erratum in Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haymart, M.R.; Banerjee, M.; Yang, D.; Stewart, A.K.; Koenig, R.J.; Griggs, J.J. The role of clinicians in determining radioactive iodine use for low-risk thyroid cancer. Cancer 2013, 119, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.