Skeletal Muscle Myofiber Development in Non-Human Primate Offspring Deprived of Estrogen in Utero

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Maternal and Fetal Hormone Levels and Offspring Growth

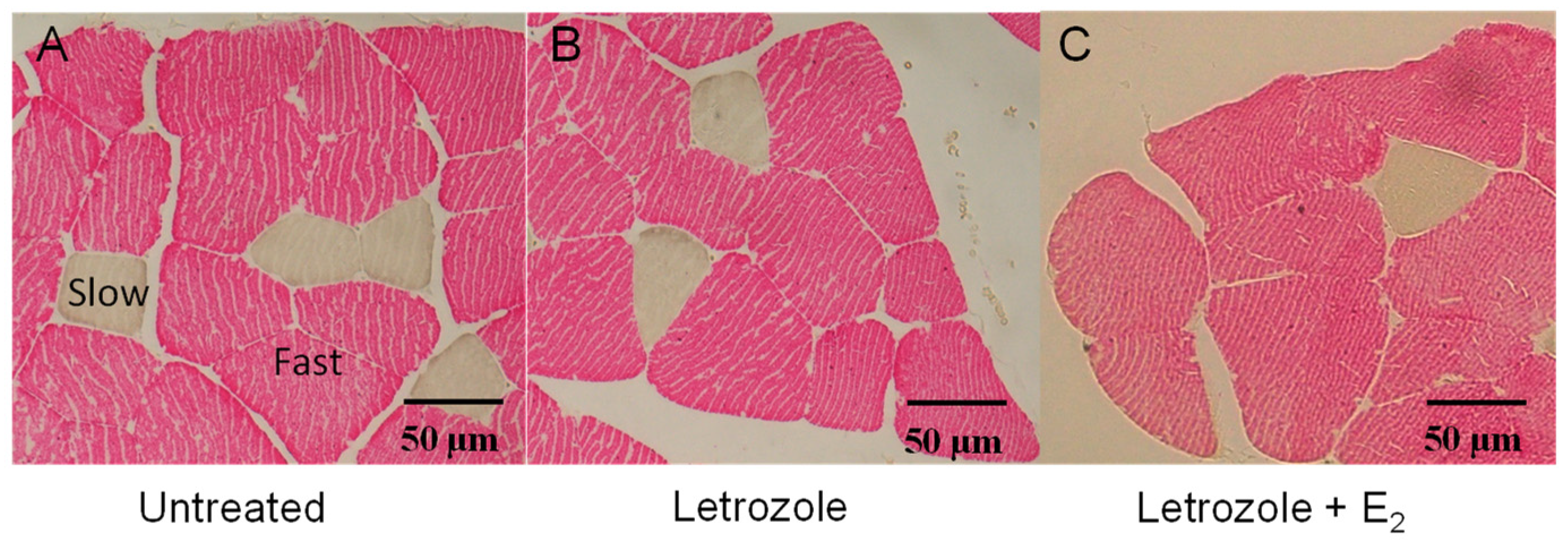

3.2. Morphology of Vastus Lateralis Slow and Fast Fibers

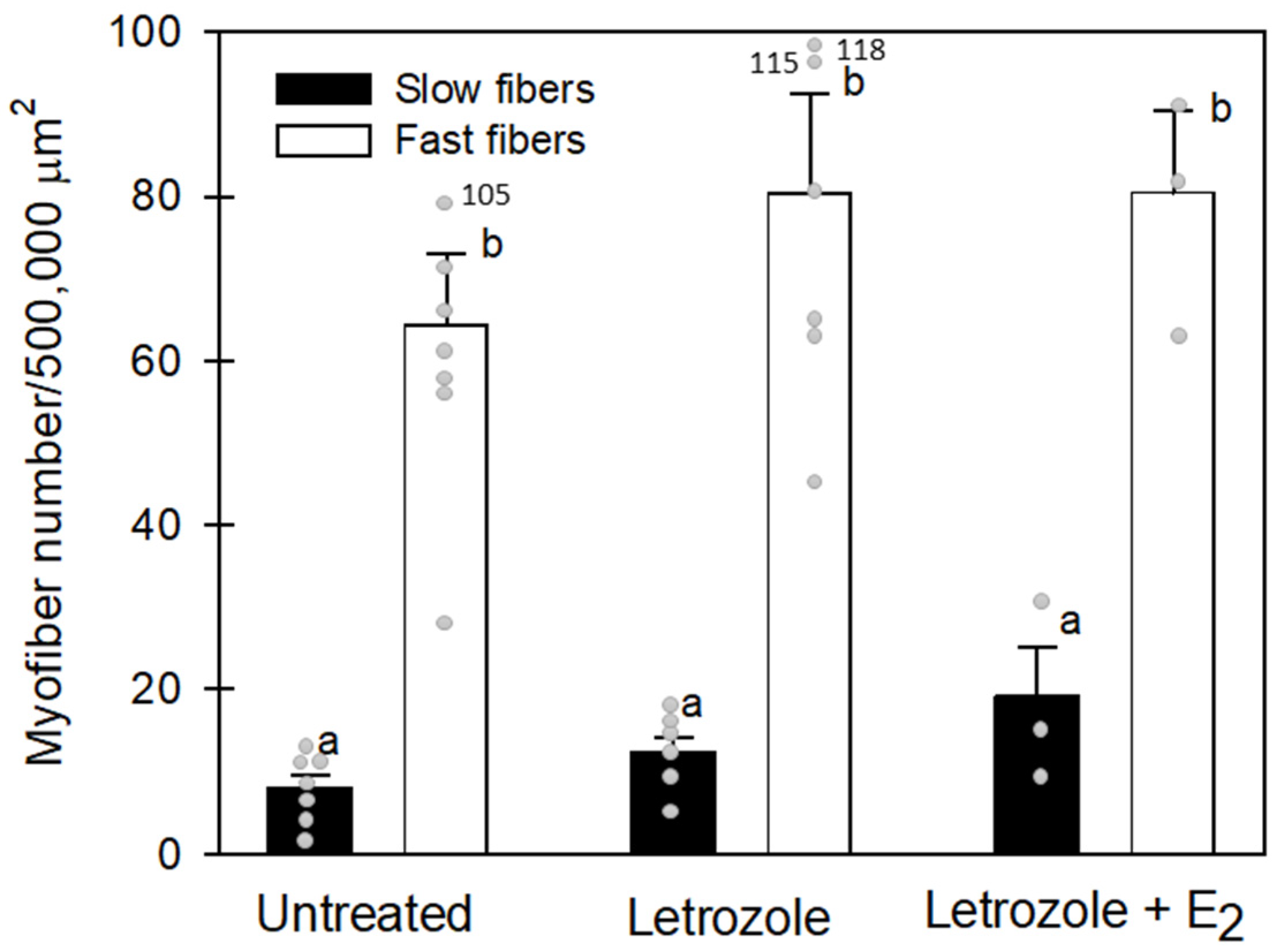

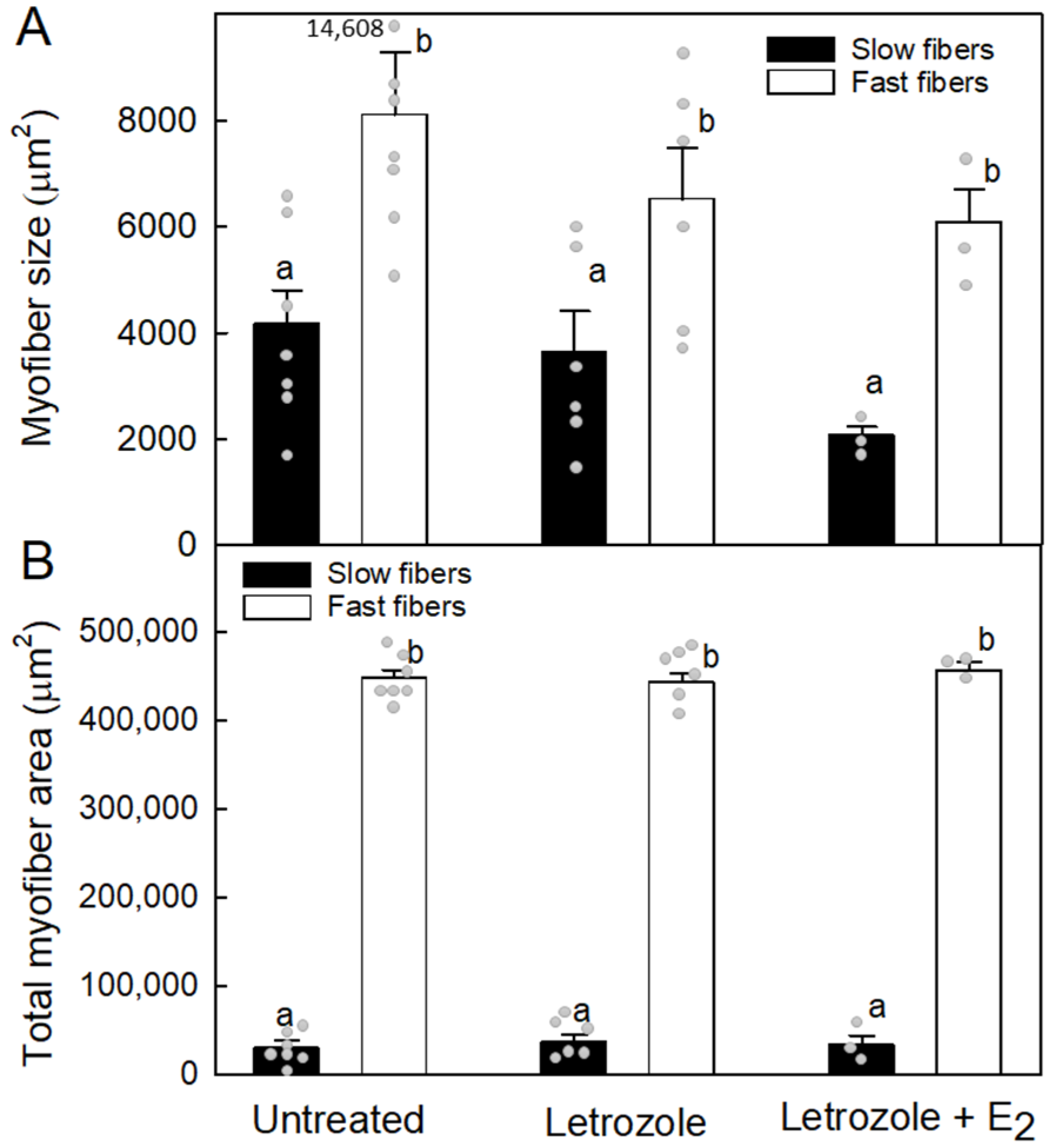

3.3. Number and Size of Vastus Lateralis Slow and Fast Fibers

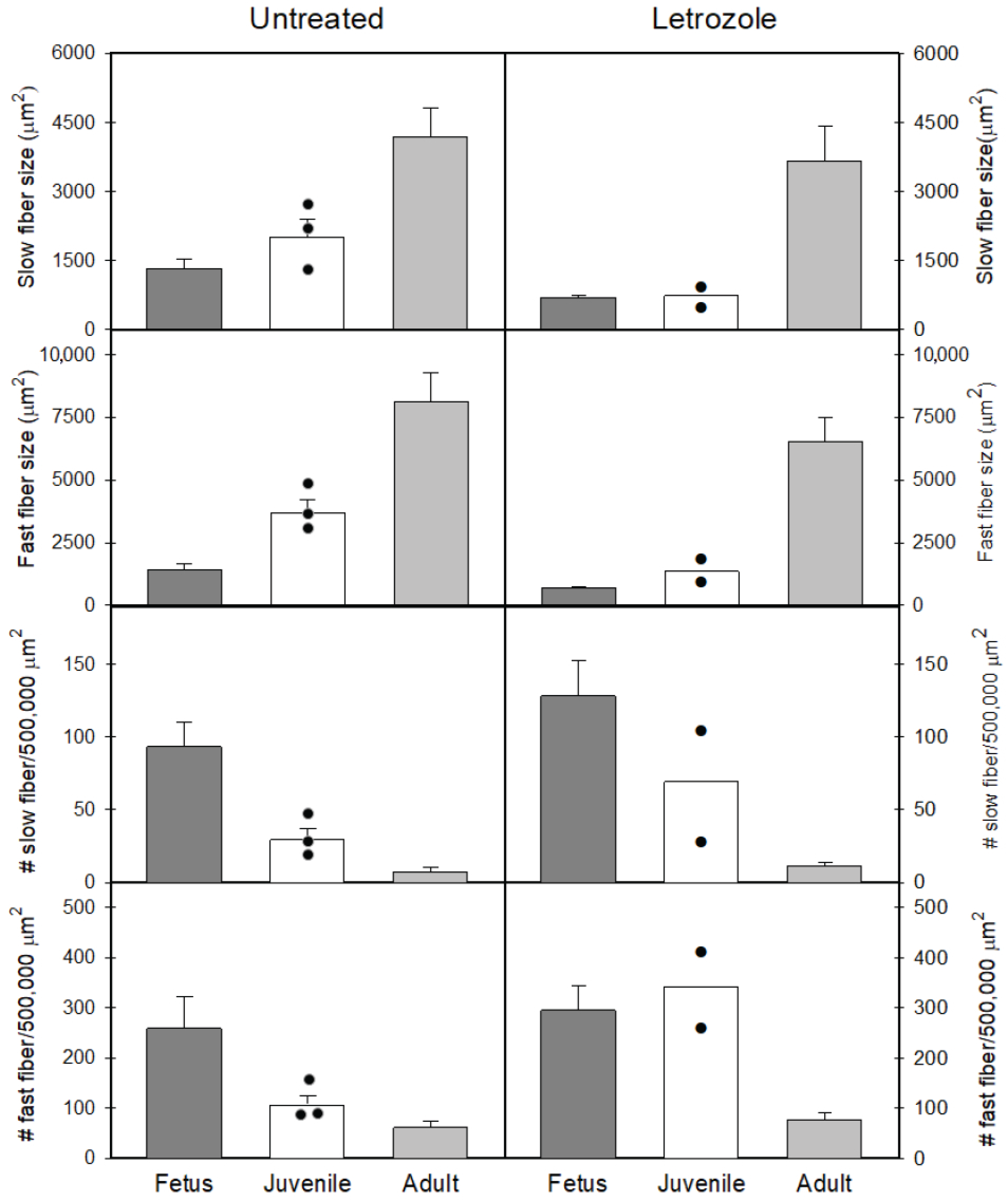

3.4. Number and Size of Vastus Lateralis Slow and Fast Fibers in Baboon Fetuses and Pre-Pubertal and Post-Pubertal Offspring

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| DBCD | Dysglycemia-based chronic disease |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| SM | Skeletal muscle |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climie, R.E.; van Sloten, T.T.; Bruno, R.M.; Taddei, S.; Empana, J.P.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Sharman, J.E.; Boutouyrie, P.; Laurent, S. Macrovasculature and microvasculature at the crossroads between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Hypertension 2019, 73, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Unnikrishnan, A.G.; Baruah, M.P.; Sahay, R.; Bantwal, G. Metabolic and energy imbalance in dysglycemia-based chronic disease. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Garber, A.J.; Grunberger, G.; Handelsman, Y.; Garvey, W.T. Dysglycemia-Based Chronic Disease: An American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Position Statement. Endocr. Pract. 2018, 24, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniu, A.; Aberdeen, G.W.; Lynch, T.J.; Nadler, J.L.; Kim, S.O.; Quon, M.J.; Pepe, G.J.; Albrecht, E.D. Estrogen deprivation in primate pregnancy leads to insulin resistance in offspring. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe, G.J.; Maniu, A.; Aberdeen, G.; Lynch, T.J.; Kim, S.O.; Nadler, J.; Albrecht, E.D. Insulin resistance elicited in postpubertal primate offspring deprived of estrogen in utero. Endocrine 2016, 54, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, E.D.; Aberdeen, G.W.; Babischkin, J.S.; Prior, S.J.; Lynch, T.; Baranyk, I.A.; Pepe, G.J. Estrogen promotes microvascularization in the fetus and thus vascular function and insulin sensitivity in offspring. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqac037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukund, K.; Subramaniam, S. Skeletal muscle: A review of molecular structure and function, in health and disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2020, 12, e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latroche, C.; Gitiaux, C.; Chrétien, F.; Desguerre, I.; Mounier, R.; Chazaud, B. Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature: A Highly Dynamic Lifeline. Physiology 2015, 30, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glancy, B.; Hsu, L.Y.; Dao, L.; Bakalar, M.; French, S.; Chess, D.J.; Taylor, J.L.; Picard, M.; Aponte, A.; Daniels, M.P.; et al. In vivo microscopy reveals extensive embedding of capillaries within the sarcolemma of skeletal muscle fibers. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 476279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Gunnarsson, R.; Bjorkman, O.; Olsson, M.; Wahren, J. Effects of insulin on peripheral and splanchnic glucose metabolism in noninsulin-dependent (type II) diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 1985, 76, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, G.J.; Albrecht, E.D. Microvascular skeletal-muscle crosstalk in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberdeen, G.W.; Babischkin, J.S.; Pepe, G.J.; Albrecht, E.D. Estrogen stimulates fetal vascular endothelial growth factor expression and microvascularization. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 262, e230364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.O.; Albrecht, E.D.; Pepe, G.J. Estrogen promotes fetal skeletal muscle myofiber development important for insulin sensitivity in offspring. Endocrine 2022, 78, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widdowson, E.M.; Crabb, D.E.; Milner, R.D. Cellular development of some human organs before birth. Arch. Dis. Child. 1972, 47, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Reggiani, C.; Akimoto, T.; Blaauw, B. Molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 8, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, D.; Fujita, R.; Kitajima, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Imai, Y.; Ono, Y. Estrogen receptor beta controls muscle growth and regeneration in young female mice. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 15, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, Y.; Ono, Y. Estrogens maintain skeletal muscle and satellite cell functions. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 229, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobori, M.; Yamamuro, T. Effects of gonadectomy and estrogen administration on rat skeletal muscle. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, 243, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, P. The role of the estrogen receptor in skeletal muscle mass homeostasis and regeneration. Acta Physiol. 2014, 212, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velders, M.; Schleipen, B.; Fritzemeier, K.H.; Zierau, O.; Diel, P. Selective estrogen receptor-beta activation stimulates skeletal muscle growth and regeneration. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiik, A.; Ekman, M.; Johansson, O.; Jansson, E.; Esbjörnsson, M. Expression of both oestrogen receptor alpha and beta in human skeletal muscle tissue. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 131, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltgalvis, K.A.; Greising, S.M.; Warren, G.L.; Lowe, D.A. Estrogen regulates estrogen receptors and antioxidant gene expression in mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lexell, J.; Sjöström, M.; Nordlund, A.S.; Taylor, C.C. Growth and development of human muscle: A quantitative morphological study of whole vastus lateralis from childhood to adult age. Muscle Nerve 1992, 15, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.B.; Bierinx, A.S.; Gnocchi, V.F.; Zammit, P.S. Dynamics of muscle fibre growth during postnatal mouse development. BMC Dev. Biol. 2010, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, R.W.; Goldspink, G. Muscle fibre growth in five different muscles in both sexes of mice. J. Anat. 1969, 104, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.D. Endocrine regulation of fetal skeletal muscle growth: Impact on future metabolic health. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, R13–R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexell, J.; Taylor, C.C.; Sjöström, M. What is the cause of the ageing atrophy? Total number, size and proportion of different fiber types studied in whole vastus lateralis muscle from 15- to 83-year-old men. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988, 84, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbrugge, S.A.J.; Schönfelder, M.; Becker, L.; Yaghoob Nezhad, F.; Hrabě de Angelis, M.; Wackerhage, H. Genes Whose Gain or Loss-Of-Function Increases Skeletal Muscle Mass in Mice: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barrett, E.J.; Eggleston, E.M.; Inyard, A.C.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Chai, W.; Liu, Z. The vascular actions of insulin control its delivery to muscle and regulate the rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle insulin action. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.J.; Wang, H.; Upchurch, C.T.; Liu, Z. Insulin regulates its own delivery to skeletal muscle by feed-forward actions on the vasculature. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E252–E263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.J.; Liu, Z. The endothelial cell: An “early responder” in the development of insulin resistance. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2013, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniyappa, R.; Montagnani, M.; Koh, K.K.; Quon, M.J. Cardiovascular actions of insulin. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.G.; Wallis, M.G.; Barrett, E.J.; Vincent, M.A.; Richards, S.M.; Clerk, L.H.; Rattigan, S. Blood flow and muscle metabolism: A focus on insulin action. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 284, E241–E258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, Z. Vascular function, insulin action, and exercise: An intricate interplay. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.A.; Clerk, L.H.; Lindner, J.R.; Klibanov, A.L.; Clark, M.G.; Rattigan, S.; Barrett, E.J. Microvascular recruitment is an early insulin effect that regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Diabetes 2004, 53, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggleston, E.M.; Jahn, L.A.; Barrett, E.J. Hyperinsulinemia rapidly increases human muscle microvascular perfusion but fails to increase muscle insulin clearance: Evidence that a saturable process mediates muscle insulin uptake. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2958–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Barrett, E.J.; Carey, R.M.; Cao, W.; Liu, Z. Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors regulate basal skeletal muscle microvascular volume and glucose use. Hypertension 2010, 55, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.D.; Richey, J.M.; Harrison, L.N.; Zuniga, E.; Kolka, C.M.; Kirkman, E.; Ellmerer, M.; Bergman, R.N. Direct administration of insulin into skeletal muscle reveals that the transport of insulin across the capillary endothelium limits the time course of insulin to activate glucose disposal. Diabetes 2008, 57, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, A.X.; Liu, Z.; Barrett, E.J. Insulin signaling stimulates insulin transport by bovine aortic endothelial cells. Diabetes 2008, 57, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, S.J.; Blumenthal, J.B.; Katzel, L.I.; Goldberg, A.P.; Ryan, A.S. Increased skeletal muscle capillarization after aerobic exercise training and weight loss improves insulin sensitivity in adults with IGT. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconsuelo, A.; Milanesi, L.; Boland, R. 17Beta-estradiol abrogates apoptosis in murine skeletal muscle cells through estrogen receptors: Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 196, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriketos, A.D.; Baur, L.A.; O’Connor, J.; Carey, D.; King, S.; Caterson, I.D.; Storlien, L.H. Muscle fibre type composition in infant and adult populations and relationships with obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997, 21, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gauronskas, P.J.; Lynch, T.J.; Albrecht, E.D.; Pepe, G.J. Skeletal Muscle Myofiber Development in Non-Human Primate Offspring Deprived of Estrogen in Utero. Endocrines 2026, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines7010001

Gauronskas PJ, Lynch TJ, Albrecht ED, Pepe GJ. Skeletal Muscle Myofiber Development in Non-Human Primate Offspring Deprived of Estrogen in Utero. Endocrines. 2026; 7(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines7010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleGauronskas, Phillip J., Terrie J. Lynch, Eugene D. Albrecht, and Gerald J. Pepe. 2026. "Skeletal Muscle Myofiber Development in Non-Human Primate Offspring Deprived of Estrogen in Utero" Endocrines 7, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines7010001

APA StyleGauronskas, P. J., Lynch, T. J., Albrecht, E. D., & Pepe, G. J. (2026). Skeletal Muscle Myofiber Development in Non-Human Primate Offspring Deprived of Estrogen in Utero. Endocrines, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines7010001